Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sciadv Add4165

Sciadv Add4165

Uploaded by

Flavio GuimaraesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sciadv Add4165

Sciadv Add4165

Uploaded by

Flavio GuimaraesCopyright:

Available Formats

S C I E N C E A D VA N C E S | R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E

NEUROSCIENCE Copyright © 2023 The

Authors, some

Not so smart? “Smart” drugs increase the level but rights reserved;

exclusive licensee

decrease the quality of cognitive effort American Association

for the Advancement

of Science. No claim to

Elizabeth Bowman1, David Coghill2, Carsten Murawski1, Peter Bossaerts3* original U.S. Government

Works. Distributed

The efficacy of pharmaceutical cognitive enhancers in everyday complex tasks remains to be established. Using under a Creative

the knapsack optimization problem as a stylized representation of difficulty in tasks encountered in daily life, we Commons Attribution

discover that methylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, and modafinil cause knapsack value attained in the task to License 4.0 (CC BY).

diminish significantly compared to placebo, even if the chance of finding the optimal solution (~50%) is not

reduced significantly. Effort (decision time and number of steps taken to find a solution) increases significantly,

but productivity (quality of effort) decreases significantly. At the same time, productivity differences across par-

Downloaded from https://www.science.org at Universidade Federal de Santa Maria on September 14, 2023

ticipants decrease, even reverse, to the extent that above-average performers end up below average and vice

versa. The latter can be attributed to increased randomness of solution strategies. Our findings suggest that

“smart drugs” increase motivation, but a reduction in quality of effort, crucial to solve complex problems,

annuls this effect.

INTRODUCTION knapsack optimization problem (“knapsack task”). Participants

Stimulant prescription-only drugs are increasingly used by employ- were asked to choose, from a set of N items of differing weights

ees and students as “smart drugs,” to enhance workplace or academ- and values, the subset that fits a knapsack of specified capacity

ic productivity (1–4). However, even if there is a subjective belief (weight constraint) while maximizing total knapsack value. We pre-

that these drugs are effective as cognitive enhancers in healthy in- sented instances of the knapsack task by means of a user interface

dividuals, evidence to support this assumption is, at best, ambigu- with less taxation of working memory and arithmetic compared to

ous (5). While improved cognitive capacities such as working purely numerical interfaces or interfaces that do not track values

memory have been shown, these effects appear to be more and weights of current choices (Fig. 1B). Besides placebo (PLC),

evident in clinical samples than the general population (6–9), a the three drugs administered were methylphenidate (MPH), mod-

finding that may be explained by ceiling effects. Most puzzling is afinil (MOD), and dextroamphetamine (DEX).

that, even in clinical populations, mitigation of cognitive deficits Armed with putative actions of these drugs, we hoped to shed

has only mild benefits for functioning, for example, at school or light on why our results emerged. The drugs MPH and DEX are

in the workplace (4), which could be related to the finding in clinical primarily indirect catecholaminergic agonists: They enhance dopa-

trials that impact on executive function is smaller and/or dose minergic activity in cortical and subcortical areas while also pro-

related (10, 11). Thus, a meaningful impact of such drugs on real- moting norepinephrine activity (14). MPH is an inhibitor of the

world function is yet to be convincingly established. dopamine transporter; it also weakly inhibits the norepinephrine

It is often underappreciated just how difficult the tasks that transporter. DEX shares this mechanism while also augmenting

humans encounter in modern life are. At an abstract level, many dopamine release into the synapse through interactions with a ve-

everyday tasks (Fig. 1A) belong to a mathematical class of problems sicular monoamine transporter (15). The effects of MOD on corti-

that is considered “hard,” a level of difficulty not captured by cog- cal and subcortical catecholamines have proved far more

nitive tasks used in past stimulant studies [technically, these prob- challenging to uncover: It has an inhibitory effect on dopamine

lems are in the complexity class NP (nondeterministic polynomial) transportation (16, 17) while influencing norepinephrine transpor-

hard] (12). Typically, they are combinatorial tasks that require sys- tation as well (18), but it also increases glutamate in the thalamus

tematic approaches (“algorithms”) for optimal outcomes. In the and hippocampus and reduces γ-aminobutyric acid in the cortex

worst case, the number of computations required increases with and hypothalamus (19, 20). We expected that because of increased

the size of the problem instance (number of ways to repair a dopamine, the drugs induced would increase motivation and, in

product, number of items available for purchase, number of stops conjunction with a concurrent increase in norepinephrine, cause

to be made on a delivery trip, etc.) such that it quickly outgrows an increase in effort expended on the task, which in turn would

cognitive capacities. Approximating solutions is not a panacea, as lead to higher performance.

this can be as hard as finding the solution itself (13). Forty participants, aged between 18 and 35 years, participated in

We report results from an experiment designed to determine a randomized double-blinded, PLC-controlled single-dose trial of

whether and how three popular smart drugs work using a task standard adult doses of the three drugs (30 mg of MPH, 15 mg of

that encapsulates the difficulty of real-life daily tasks: the 0-1 DEX, and 200 mg of MOD) and PLC, administered before being

asked to solve eight instances of the knapsack task. Doses are at

the high end of those administered in clinical practice, reflecting

1

Centre for Brain, Mind, and Markets, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria typical doses in nonmedical settings, where use tends to be occa-

3010, Australia. 2Departments of Paediatrics and Psychiatry, University of Mel-

bourne, Parkville, Victoria 3010, Australia. 3Faculty of Economics, University of sional rather than chronic. Ethics approval was obtained from the

Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 9DD, UK. University of Melbourne (HREC 1749142; registered as clinical trial

*Corresponding author. Email: plb32@cam.ac.uk

Bowman et al., Sci. Adv. 9, eadd4165 (2023) 14 June 2023 1 of 8

S C I E N C E A D VA N C E S | R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E

Downloaded from https://www.science.org at Universidade Federal de Santa Maria on September 14, 2023

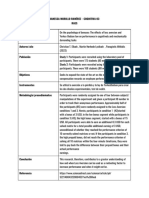

Fig. 1. Task relevance, experiment design, and overall participant performance. (A) Computationally difficult tasks are ubiquitous in everyday life. (B) Task interface

with example instance (grayscale version; original in color). Items become highlighted as they are selected. (C) Timeline of experiment and Latin square randomization

across four experimental sessions. (D) Proportion of correct solutions submitted, stratified by task difficulty (Sahni-k index, from low 0 to high 4); circle: estimate of

proportion; bars, ±2 SE.

PECO: ACTRN12617001544369, U1111-1204-3404). Participants (22–24). According to this metric, an instance is “easy” (Sahni-k

attempted each instance twice. A time limit of 4 min was = 0) if it can be solved using the greedy algorithm, which is to fill

imposed, which was binding in only ~1% of valid responses. The the knapsack with items in decreasing order of the ratio of value/

four experimental sessions were at least 1 week apart from each weight until the capacity limit is reached. If n items must be in

other. Participants were randomly assigned to conditions using a the knapsack before the greedy algorithm can be used to produce

Latin square design (Fig. 1C). To gauge the comparability of our the solution, then Sahni-k = n. Difficulty thus increases with

results to those from prior experiments, participants were also Sahni-k. In our experiment, Sahni-k varied across instances, from

asked to complete four tasks from the CANTAB cognitive battery 0 to 4 (see Materials and Methods). Confirming findings of

(the simple and five-choice reaction time task, the stockings of earlier experiments (22–24), we observed a significant decrease in

Cambridge Task, the spatial working memory task, and the stop- performance (proportion of correct attempts) as Sahni-k increased

signal task) (21). (slope = −0.56, P < 0.0001; Fig. 1D and table S1).

Given the well-documented erratic nature of the effects of the We used two additional metrics of difficulty: (i) DP complexity, a

drugs on baseline cognitive functions (10, 11) and the lack of under- difficulty metric derived from the dynamic programming algorithm

standing of how baseline cognitive functions translate into success used to solve knapsack problems (25), and (ii) props, the number of

on complex combinatorial tasks such as the knapsack task, we propagations, and hence, the time it takes MiniZinc, a widely used

refrain from formulating hypotheses about the results to be expect- general-purpose solver for hard computational problems (26).

ed. Instead, we adhered strictly to stringent statistical model selec- Human performance often shows little simple correlation with

tion protocol, using Akaike and Bayesian information criteria, to these difficulty metrics (figs. S1 and S2), but they are included in

select the best-fitting models. We then performed statistical tests the analysis because they explain part of the performance variance

only on those models (see Materials and Methods). left unexplained by Sahni-k. The difficulty metrics are positively but

imperfectly correlated (see Materials and Methods).

RESULTS Drugs did not affect the chance of finding the correct

Performance decreases with instance-specific metrics of solution

difficulty We first examined the impact of the drugs on a participant’s ability

Participants solved 50.3% of instances correctly (SEM = 0.9%). In- to solve an instance. To this end, we estimated a logistic model re-

stances differed in difficulty. To characterize the latter, we used a lating performance to instance difficulty and drug condition, ac-

metric, Sahni-k, that has successfully predicted performance of counting for possible interactions and participant-specific

human participants in the knapsack task in earlier experiments random effects. We always considered several different model

Bowman et al., Sci. Adv. 9, eadd4165 (2023) 14 June 2023 2 of 8

S C I E N C E A D VA N C E S | R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E

specifications and report the one with the best goodness of fit (see both P < 0.0001; slope(MOD) = 9.1, P = 0.10; table S3]. Inspection

Materials and Methods for details). The best-fitting model was one of the distribution function of time spent reveals a sizeable and sig-

that pooled the active drug conditions and where random effects on nificant move of the distribution under drug conditions to the left

the intercept term at the individual level were accounted for, and relative to that under PLC (pointwise 95% confidence intervals fail

two difficulty metrics were included as explanatory variables for to intersect except in the tails; Fig. 2B). The increase in time spent

performance, Sahni-k and DP complexity. There was no significant under MPH is equivalent to an increase in difficulty (Sahni-k) of

effect of drug on performance (slope = −0.16, P = 0.11; see table S1). more than 4 points. That is, participants spent almost as much

time on the easiest instances under MPH as on the hardest instances

Drugs decreased value attained under PLC, without any corresponding improvement in

Next, we investigated the effect of the drugs on the value attained in performance.

an attempt. We found that drugs had a negative effect on value

(slope = −0.003, P = 0.02; table S2), that is, participants tended to Drugs increased number of moves

achieve a lower value in the instances in the drug conditions. A plot Another index of effort is the number of moves of items in and out

of the distribution of attained values in the drug conditions against of the suggested solution undertaken while attempting to solve an

Downloaded from https://www.science.org at Universidade Federal de Santa Maria on September 14, 2023

that under PLC shows that the negative effect extends to the entire instance (indicated by clicking on the item icon in the user interface;

distribution: The chance that success is below any given level is see Fig. 1B). Drugs increase the number of item moves: DEX, 7.2

greater under drugs than under PLC (pointwise 95% confidence in- moves (P < 0.0001); MPH, 6.1 moves (P < 0.0001); and MOD, 1.9

tervals mostly fail to intersect; Fig. 2A). moves (P > 0.1; table S3). The distribution of moves shifts leftward

under drugs (Fig. 2C), analogous to the shift observed in relation to

Drugs increased time spent time spent (Fig. 2B). The size of the effect on moves of DEX and

We then turned to effort expended. For this, we examined the time MPH is the same as increasing difficulty (Sahni-k) by more than

participants spent on an instance before submitting their suggested 2 points. Because both time spent and moves taken increase in

solution. Participants spent substantially more time on an instance the drug conditions, the effect on speed is unclear. Figure 2D

in the drug conditions [slope(DEX) = 18.8; slope(MPH) = 29.1; shows that the distribution of the number of seconds per move

Fig. 2. Performance, effort, and speed. (A to C) Empirical cumulative distribution function under PLC (blue) and drugs (red) and pointwise 95% confidence bounds (CB;

based on Greenwood’s formula). (A) Knapsack value reached as a fraction of maximal value. PLC first-order stochastically dominates drugs, implying that the chance that

participants reach any value is uniformly lower under drugs than under PLC. (B) Effort is equal to the time spent until submission of solution. Drugs first-order stochas-

tically dominates PLC, implying that the chance of spending any amount of time is uniformly higher under drugs than under PLC. (C) Effort is equal to the number of

moves of items in/out of knapsack until submission of solution; drugs first-order stochastically dominates PLC, implying that the chance of executing any number of

moves is uniformly higher under drugs than under PLC. (D) Probability density estimates of speed under PLC (blue) and drugs (red), where speed is equal to the number of

seconds per move. Because the density under drugs is shifted to the left of that under PLC, speed tends to be higher under drugs than under PLC.

Bowman et al., Sci. Adv. 9, eadd4165 (2023) 14 June 2023 3 of 8

S C I E N C E A D VA N C E S | R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E

shifted to the left, but regression analysis (table S5) fails to produce a significant tightening: The range of estimated deviations was

significant relations (P > 0.05). Thus, if one measures motivation in reduced by more than half. For MPH, the range dropped from

terms of time spent or number of items moved, drugs clearly en- [−0.038, 0.0046] to [−0.02, 0.0092] (see Fig. 3B). A Wilcoxon

hanced motivation. If, however, motivation is to be captured by signed rank test confirmed that individual productivity deviations

speed, the evidence is mixed. were stochastically smaller under MPH than under PLC (P <

0.0001). This result must not be interpreted as regression to the

Drugs significantly decrease quality of effort mean (27), as temporal participant assignment to MPH and PLC

We therefore proceeded to study the quality of the moves made by was random. An analogous statistically significant stochastic reduc-

participants. We defined productiveness as the average gain in value tion was measured for MOD relative to PLC (P = 0.02; fig. S4) and

per move of attempted knapsacks (as a fraction of optimal value). for DEX relative to PLC (P = 0.002; fig. S5).

Figure 3A displays violin plots of productivity for PLC and the Significant negative correlation between productivity under

three drugs separately. Productivity is uniformly smaller across all MPH and under PLC emerged [slope of the Ordinary Least

drugs (relative to PLC). Regression analysis confirmed a significant Squares (OLS)] fit = −0.13, P < 0.001 based on z-statistic computed

and sizable drop in productivity with drugs (all P < 0.001; see table from Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) estimates of correla-

Downloaded from https://www.science.org at Universidade Federal de Santa Maria on September 14, 2023

S6) with an average decrease in productivity equivalent to increas- tion of estimated random effects as reported in table S6, correlation

ing task difficulty by 1.5 (Sahni-k) points. is equal to −0.43; Fig. 3B). We thus observed a disturbing perfor-

mance reversal. Participants who were above the mean under PLC

Drugs cause quality of effort reversals tended to fall below the mean under MPH. Likewise, significant re-

The mean effect of drugs on productivity masks substantial hetero- versals emerged under MOD (correlation of −0.55, P < 0.001; fig. S4

geneity across participants. Investigation of deviations in individual and table S6) and under DEX (correlation of −0.21, P = 0.01; fig. S5

productivity from the mean under PLC versus under drugs revealed and table S6).

Fig. 3. Quality of effort. (A) Violin plots of productivity, measured as average increase in value of knapsack per item move in/out of knapsack. Stars indicate significance

of differences in means based on a generalized linear model that accounts for confounding factors and participant-specific random effects for average productivity and

impact of drugs (table S6); *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001. (B and C) Estimated participant-specific (random) deviations in productivity from mean productivity. Productivity is

measured as average increase in value of knapsack per item move; random effects were estimated with a generalized linear model that accounts for confounding factors

and participant-specific random effects for average productivity and impact of drugs (table S6). (B) MOD against DEX. The red line shows OLS fit, with significant positive

slope (P < 0.001). (C) MPH against PLC. The red line shows OLS fit, with significant negative slope (P < 0.001). Arrows indicate range of productivity deviations under PLC

(horizontal) and MPH (vertical). The range is smaller under MPH than under PLC, implying reversion to the mean. (D) Reduction in quality of first full knapsack chosen

under drugs (right) relative to PLC (left). Quality is measured as overlap between number of items in chosen knapsack and optimal knapsack. Decrease in mean quality is

significant at **P < 0.01, based on a generalized linear model that accounts for effect of instance difficulty and overlap with items in the Greedy solution, as well as

participant-specific random effects for average quality (table S7); overlap tends to be lower under drugs than under PLC, implying lower quality of solution search.

Bowman et al., Sci. Adv. 9, eadd4165 (2023) 14 June 2023 4 of 8

S C I E N C E A D VA N C E S | R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E

Across drugs, strong correlation in individual participant devia- That is, heterogeneity in effort quality under drugs stochastically

tions in individual productivity from the mean effects across drug dominated that under PLC.

conditions emerged (table S6). The correlation was as high as 0.70 In addition, significant negative correlation between individual

for MOD and DEX (the slope of the OLS line, close to 45°, is highly deviations from average effort quality between each drug and PLC

significant: P < 0.001; Fig. 3C). Although DEX and MPH are emerged. This means that, if an individual exhibited above-average

thought to affect neurotransmission in analogous ways, we found increase in knapsack value per move under PLC, she tended to be

a strong negative correlation between individual effects under the below average under MPH, DEX, and MOD. Conversely, if an indi-

two drugs [see fig. S6 (OLS slope = −0.29; P < 0.0001)]. vidual performed below average under PLC, the quality of effort was

above average under MPH, DEX, and MOD.

Quality of effort decreases because moves become We found that this reversal in effort quality emerged because

more random participants became more erratic in their choices when under

Last, we examined attempts at a finer level of granularity. Prior work drugs: The first full knapsack that they considered was more

has revealed that the performance of an attempt to solve an instance random than under PLC. This disproportionally affected above-

in the knapsack task depends on the quality of the first full knapsack average participants; those that performed below average under

Downloaded from https://www.science.org at Universidade Federal de Santa Maria on September 14, 2023

that a participant composes (23). Here, we define quality as the PLC did increase their effort quality merely because they spent

number of items common to the first full knapsack and the more effort (spent more time).

optimal knapsack. The quality of the first knapsack was lower in Our task was computationally hard, and hence, optimal choices

the drug conditions compared to PLC (slope = −0.176, P = 0.003; require systematic thought. Random exploration is not effective in

table S8). The mean overlap is significantly lower under drugs than this task, in contrast with probabilistic tasks, where strategies such

under PLC (Fig. 3D). as epsilon-greedy or softmax can be optimal (28). Because quality of

The first full knapsack overlaps more with the optimal one if choice is secondary in probabilistic tasks, it is expected that for

there is more commonality between the solution from the greedy these, drugs such as MPH or MOD have been observed to

algorithm and the optimal solution, and this correlation increases improve performance, albeit mildly (29–34).

with instance difficulty (Sahni-k; table S7). This is consistent with Good effort allocation is primordial for the knapsack task. It has

earlier findings that the first full knapsack tends to be obtained been argued that dopamine and norepinephrine, two neuromodu-

using the greedy algorithm (23). Evidently, drugs tend to make lators targeted by the drugs administered in this study, regulate the

the first full knapsack more random. This, together with the trade-off between reward and effort cost (35) and that this trade-off

finding that exploration (number of moves) increases, suggests is governed by the overarching goal of maximizing the expected

that participants’ approach to solving a hard problem such as the value of control; the latter steers not only the quantity of effort

knapsack task becomes less systematic under drugs; in other but also the type of effort chosen (referred to as efficacy). Evidently,

words, while drugs increase persistence, they appear to reduce the this theory elucidates the workings of the drugs that we adminis-

quality of effort. tered: They boost subjective reward while reducing perceived

effort, but they have a detrimental effect on efficacy.

Scores on CANTAB tasks do not predict drug effects The drugs that we administered are known to reduce perfor-

We found significant correlation between scores on only two mance of healthy participants in some of the CANTAB tasks that

CANTAB tasks (working memory task: P < 0.001; simple reaction we included in our experiment (6–9). We confirmed these effects

time task: P < 0.01) and performance in the knapsack task (perfor- and extended them to the knapsack task. However, we failed to

mance was assessed on the basis of whether the submitted solution predict individual drug effects in the knapsack task from scores

was correct; see figs. S7 and S8). However, there was no significant on the CANTAB tasks or from drug effects in the CANTAB tasks.

interaction with drugs, in that scores on the CANTAB tasks did not When compared to recorded effects on baseline cognition

predict drug effects in the knapsack task (P > 0.10; examples: figs. S9 (CANTAB tasks) in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity dis-

to S12). Likewise, we were not able to predict individual drug effects order (ADHD) (8, 10, 11), there appears to be overlap: Evidence of

in the knapsack task from drug effects on individual scores in the effects is scattered, and if they emerge, then effects are characterized

CANTAB tasks (P > 0.10; examples: figs. S13 to S16). by considerable heterogeneity. Hence, the evidence from healthy

participants appears to be an extension of that of the clinical pop-

ulation, so that ADHD may not be a categorical disorder but instead

DISCUSSION better described as a dimensional disorder (36, 37).

While drug treatments did not cause a significant drop in the Because the knapsack task encapsulates difficulty encountered in

average chance of finding the solution to the knapsack problem in- everyday problem-solving, our paradigm could help shed light on

stances, they did lead to a significant overall drop in value attained. how medications such as MPH improve the day-to-day functioning

Whether defined as time spent or number of moves (of items in/out of patients suffering from, e.g., ADHD. In addition, the knapsack

of the knapsack), effort increased significantly on average. Because task facilitates the much-needed comparison across clinical and

both aspects of effort increased, the effect on speed (number of subclinical populations (36). Last, for subclinical populations, our

seconds per move) became ambiguous. paradigm provides a convenient framework with which to eventu-

The most notable aspect of our findings concerns heterogeneity ally discover the genuinely smart drugs, i.e., the drugs that not only

in quality of effort, however. Effort quality was defined as the increase effort but also enhance quality of effort.

average increase in knapsack value per move. We found a significant

stochastic reduction in the magnitudes of individual deviations

from mean effort quality under each drug, compared to PLC.

Bowman et al., Sci. Adv. 9, eadd4165 (2023) 14 June 2023 5 of 8

S C I E N C E A D VA N C E S | R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E

Table 1. Difficulty of instances used in the knapsack task.

Instance (#items) 1 (10) 2 (10) 3 (12) 4 (10) 5 (12) 6 (12) 7 (12) 8 (10)

Sahni-k 1 3 2 0 1 1 4 3

DC complexity 109 100 117 105 46 143 124 80

MiniZinc #props 3577 1117 25,961 4133 6278 19,417 16,498 9155

MATERIALS AND METHODS of the items remains beneath a given weight limit. The knapsack

Experimental protocol task is in the class of NP-time hard problems.

Forty healthy male (n = 17) and female (n = 23) volunteers between Participants were presented with eight unique instances of the

the ages of 18 and 35 (mean, 24.5 years) were recruited from campus knapsack task, with each instance containing 10 or 12 different

Downloaded from https://www.science.org at Universidade Federal de Santa Maria on September 14, 2023

advertisements. All volunteers were screened by a clinician via semi- items and a different weight limit. The task was presented via

structured interview and examination before enrollment in the laptop, and participants clicked on items to select or deselect

study. Study exclusion criteria included history of psychiatric or them from their solution. The problem’s weight limit and the cu-

neurological illness including epilepsy or head injury, previous mulative weight and value of the selected items were displayed at

use of psychotropic medication, history of substantial drug use, the top of the screen. Participants were prevented from selecting

heart conditions (including high blood pressure, defined as above items that would exceed the weight limit. A 4-min limit was

140 mm/Hg systolic and/or 90 mm/Hg diastolic pressure as mea- imposed on each presentation of the problem, and participants

sured at the initial assessment session), pregnancy, or glaucoma. could submit their solution at any time during those 4 min by press-

A brief cardiac examination was performed, and any family ing the space bar. Participants were not informed whether their sol-

history of sudden death of a first-degree relative through cardiac ution was optimal or not, and each instance was presented twice.

or unknown causes before the age of 50 years old also excluded Each selection or deselection of an item before submission, as

the participant. Participants were asked to refrain from any well as the timing of each choice, is recorded for later analysis.

alcohol and caffeine from midnight the night before each The same eight instances were used as those reported in (23).

testing session. Details of the instances, including solutions, can be found there.

Participants were required to attend four testing sessions, each Table 1 lists the instances along with metrics of difficulty used

session spaced at least 7 days from the previous session. At each here. Instances are numbered as in the article.

session, participants received one of either 200 mg of MOD, 30 Difficulty metrics are positively but far from perfectly correlated.

mg of MPH, 15 mg of DEX, or microcrystalline cellulose (Avicel) Table 2 displays the correlation matrix.

PLC. All medications were dispensed as identical white capsules

in double-blinded packaging. Participants were randomly allocated CANTAB tasks

into four groups, each group receiving a different sequence of med- Simple and five-choice reaction time task

ications and PLC across sessions according to a counterbalanced The reaction time tasks assess the participants’ response speed to a

Latin square design (see Fig. 1B). Randomization sequences were visual cue in either a predictable location (the simple variant) or in

generated by the Melbourne Clinical Trials Centre (Melbourne one of five locations (the five-choice variant). The mean duration

Children’s Campus). between releasing the response button and touching the target

Participants arrived at the testing venue in the morning and had button, calculated across all correct trials, is the major outcome of

their blood pressure measured after at least 5 min of sitting quietly. interest.

The capsule for the session was given with a glass of water, and a 90- Stockings of Cambridge

min waiting period commenced. Participants were encouraged to The stockings of Cambridge task examines spatial planning and, to

bring study or quiet reading to do during this period. After 90 a lesser extent, spatial working memory. The participant is required

min, participants’ blood pressure was measured, and they then com- match a sequential pattern of balls while following rules regarding

pleted the complex optimization and cognitive tasks. Upon comple- the permitted movement of the balls in space. The task difficulty

tion of all the tasks, participants’ blood pressure was measured one varies by the minimum number of moves required to match the

final time, and participants were then free to go. The experiment given pattern and ranges from two to five moves. The major

was registered as a clinical trial (PECO: ACTRN12617001544369, outcome of interest is the number of patterns matched in the

U1111-1204-3404). Ethics approval was obtained from the Univer-

sity of Melbourne (HREC1749142).

The knapsack task Table 2. Correlations between difficulty metrics. SE = 0.20 (based on

The knapsack optimization problem (“knapsack task”) is a combi- Fisher’s transformation).

natorial optimization task, where the participant is presented with a DC complexity MiniZinc #props

number of items, each item having an associated weight and value.

Sahni-k 0.08 0.20

The goal is to find the combination of items that maximizes the

combined value of the selected items, while the combined weight DC complexity 0.52

Bowman et al., Sci. Adv. 9, eadd4165 (2023) 14 June 2023 6 of 8

S C I E N C E A D VA N C E S | R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E

minimum moves, calculated across all correct trials. The change in

number of correct trials with increasing difficulty can also be exam- View/request a protocol for this paper from Bio-protocol.

ined. Note that on one occasion, the app-based task failed to run,

resulting in no data for that task for that session.

Spatial working memory REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. E. Bowman, B. Feng, C. Murawski, P. Bossaerts, Surveying the Use of Pharmaceutical Cognitive

The spatial working memory task is a test of the participant’s ability

Enhancers in the Australian Financial Services Industry (SSRN Scholarly Paper 3661966, Social

to retain spatial information in working memory. The participant is Science Research Network, 2020).

required to collect tokens hidden in a randomly placed array of 2. P. Dietz, M. Soyka, A. G. Franke, Pharmacological neuroenhancement in the field of eco-

boxes, where a found token will never reappear inside the same nomics—Poll results from an online survey. Front. Psychol. 7, 520 (2016).

box. Task difficulty is increased by increasing the number of 3. R. M. Emanuel, S. L. Frellsen, K. J. Kashima, S. M. Sanguino, F. S. Sierles, C. J. Lazarus,

tokens and boxes, starting with 4, and progressing through 6, 8, Cognitive enhancement drug use among future physicians: Findings from a multi-insti-

tutional census of medical students. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 28, 1028–1034 (2013).

and 12 box arrays. Performance is most often calculated as a “strat-

4. A. F. Kortekaas-Rijlaarsdam, M. Luman, E. Sonuga-Barke, J. Oosterlaan, Does methylphe-

egy score,” that is, the number of times their search for the token nidate improve academic performance? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Child

started from the same box, implying that a specific spatial strategy Adolesc. Psychiatry 28, 155–164 (2019).

Downloaded from https://www.science.org at Universidade Federal de Santa Maria on September 14, 2023

is used. Between error and within error counts are also often exam- 5. I. Ilieva, J. Boland, M. J. Farah, Objective and subjective cognitive enhancing effects of

ined, being the number of times a box in which a token has previ- mixed amphetamine salts in healthy people. Neuropharmacology 64, 496–505 (2013).

ously been found is revisited, the number of times a participant 6. S. R. Chamberlain, T. W. Robbins, S. Winder-Rhodes, U. Müller, B. J. Sahakian, A. D. Blackwell,

J. H. Barnett, Translational approaches to frontostriatal dysfunction in attention-deficit/

revisits a box already shown to be empty. hyperactivity disorder using a computerized neuropsychological battery. Biol. Psychiatry

Stop signal task 69, 1192–1203 (2011).

The stop signal task is a test of response inhibition, generating an 7. D. Repantis, P. Schlattmann, O. Laisney, I. Heuser, Modafinil and methylphenidate for

estimate of stop signal reaction time using staircase functions. neuroenhancement in healthy individuals: A systematic review. Pharmacol. Res. 62,

The participant presses a left-hand button when a cue arrow indi- 187–206 (2010).

8. M. E. Smith, M. J. Farah, Are prescription stimulants “smart pills”? The epidemiology and

cates left and a right-hand button when the cue indicates right,

cognitive neuroscience of prescription stimulant use by normal healthy individuals.

except for when a tone is heard. If a tone is heard, the participant Psychol. Bull. 137, 717–741 (2011).

should refrain from pressing the button. The timing of the tone in 9. R. M. Battleday, A.-K. Brem, Modafinil for cognitive neuroenhancement in healthy non-

relation to the cue is adjusted throughout the trial, depending on sleep-deprived subjects: A systematic review. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 25,

performance, until the participant is able to stop in only approxi- 1865–1881 (2015).

mately 50% of trials. This duration between cue and tone is the 10. D. R. Coghill, S. M. Rhodes, K. Matthews, The neuropsychological effects of chronic

methylphenidate on drug-naive boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol.

major measure of interest. Psychiatry 62, 954–962 (2007).

11. R. H. Pietrzak, C. M. Mollica, P. Maruff, P. J. Snyder, Cognitive effects of immediate-release

Statistical analysis methylphenidate in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neurosci. Bio-

Formal statistical tests of drug effects, both at the population level, behav. Rev. 30, 1225–1245 (2006).

and if deemed appropriate, at the individual level, are based on 12. S. Arora, B. Barak, Computational Complexity: A Modern Approach (Cambridge Univ.

Press, 2009).

random-effects generalized linear modeling using the MATLAB

13. N. Yadav, C. Murawski, S. Sardina, P. Bossaerts. Is hardness inherent in computational

function glmfit in release 2022b (The MathWorks Inc., MA, problems? Performance of human and electronic computers on random instances of the 0-

USA). Absent specific hypotheses, model specification, including 1 knapsack problem, in ECAI 2020 (IOS Press, 2020), pp. 498–505.

whether (individual) random effects had to be included and at 14. T. E. Wilens, Mechanism of action of agents used in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disor-

what level (per drug), or for all drug treatments combined, was der. J. Clin. Psychiatry 67, 11408 (2006).

based on strict adherence to model selection using the Akaike 15. R. Kuczenski, D. S. Segal, Effects of methylphenidate on extracellular dopamine, serotonin,

and norepinephrine: Comparison with amphetamine. J. Neurochem. 68,

and Bayesian information criteria.

2032–2037 (1997).

MATLAB code that generates the statistics and figures, along 16. E. Mignot, S. Nishino, C. Guilleminault, W. Dement, Modafinil binds to the dopamine

with underlying data, can be found in the notebook “figures.mlx” uptake carrier site with low affinity. Sleep 17, 436–437 (1994).

and “SOM.mlx” of the GitHub repository bmmlab/PECO (https:// 17. D. Zolkowska, R. Jain, R. B. Rothman, J. S. Partilla, B. L. Roth, V. Setola, T. E. Prisinzano, M. H.

zenodo.org/badge/latestdoi/592775835). The MATLAB code allows Baumann, Evidence for the involvement of dopamine transporters in behavioral stimulant

the reader to understand exactly the nature of the model estimated. effects of modafinil. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 329, 738–746 (2009).

18. B. K. Madras, Z. Xie, Z. Lin, A. Jassen, H. Panas, L. Lynch, R. Johnson, E. Livni, T. J. Spencer,

The code also facilitates replication. The combination of code and

A. A. Bonab, G. M. Miller, A. J. Fischman, Modafinil occupies dopamine and norepinephrine

data allows the reader to replicate all statistical results reported in transporters in vivo and modulates the transporters and trace amine activity in vitro.

the article and its Supplementary Materials, as well as generating J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 319, 561–569 (2006).

all tables and figures. Tests of stochastic dominance of individual 19. L. Ferraro, T. Antonelli, W. T. O’Connor, S. Tanganelli, F. Rambert, K. Fuxe, The antinarco-

random effects under drugs versus under PLC were based on the leptic drug modafinil increases glutamate release in thalamic areas and hippocampus.

Neuroreport 8, 2883–2887 (1997).

Wilcoxon signed rank test of the null that the sizes (squares) of

20. L. Ferraro, S. Tanganelli, W. T. O’Connor, T. Antonelli, F. Rambert, K. Fuxe, The vigilance

the individual random effects are exchangeable under the promoting drug modafinil decreases GABA release in the medial preoptic area and in the

treatments. posterior hypothalamus of the awake rat: Possible involvement of the serotonergic 5-HT3

receptor. Neurosci. Lett. 220, 5–8 (1996).

21. CANTAB [Cognitive assessment software] (Cambridge Cognition, 2019); www.cantab.com.

Supplementary Materials 22. D. Meloso, J. Copic, P. Bossaerts, Promoting intellectual discovery: Patents versus markets.

This PDF file includes: Science 323, 1335–1339 (2009).

Figs. S1 to S16 23. C. Murawski, P. Bossaerts, How humans solve complex problems: The case of the knapsack

Tables S1 to S7 problem. Sci. Rep. 6, 34851 (2016).

References

Bowman et al., Sci. Adv. 9, eadd4165 (2023) 14 June 2023 7 of 8

S C I E N C E A D VA N C E S | R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E

24. J. P. Franco, N. Yadav, P. Bossaerts, C. Murawski, Generic properties of a computational task 35. M. E. Walton, S. Bouret, What is the relationship between dopamine and effort? Trends

predict human effort and performance. J. Math. Psychol. 104, 102592 (2021). Neurosci. 42, 79–91 (2019).

25. D. Pisinger, P. Toth, Knapsack problems, in Handbook of Combinatorial Optimization: 36. J. M. Swanson, T. L. Wigal, N. D. Volkow, Contrast of medical and nonmedical use of

Volume1–3, D.-Z. Du, P. M. Pardalos, Eds. (Springer, 1998); pp. 299–428; https://doi.org/10. stimulant drugs, basis for the distinction, and risk of addiction: Comment on Smith and

1007/978-1-4613-0303-9_5. Farah (2011). Psychol. Bull. 137, 742–748 (2011).

26. N. Nethercote, P. J. Stuckey, R. Becket, S. Brand, G. J. Duck, G. Tack, MiniZinc: Towards a 37. I. M. E. Idema, J. M. Payne, D. Coghill, Effects of methylphenidate on cognitive functions in

standard CP modelling language, in Principles and Practice of Constraint Programming—CP boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Does baseline performance matter?

2007, C. Bessière, Ed. (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Springer, 2007), pp. 529–543. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 89, 615–625 (2021).

27. P. L. Yudkin, I. M. Stratton, How to deal with regression to the mean in intervention studies. 38. C. E. Rogers, Algorithm AS 65: Interpreting structure formulae. Appl. Stat. 22,

Lancet 347, 241–243 (1996). 414–424 (1973).

28. R. S. Sutton, A. G. Barto, Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction (MIT Press, ed. 2, 2018).

29. N. Agay, E. Yechiam, Z. Carmel, Y. Levkovitz, Non-specific effects of methylphenidate Acknowledgments

(Ritalin) on cognitive ability and decision-making of ADHD and healthy adults. Psycho- Funding: This work was supported by the University of Melbourne R@MAP Chair (to P.B.).

pharmacology 210, 511–519 (2010). Author contributions: Conceptualization: E.B., D.C., C.M., and P.B. Methodology: E.B., D.C., C.M.,

30. N. Agay, E. Yechiam, Z. Carmel, Y. Levkovitz, Methylphenidate enhances cognitive per- and P.B. Data collection: E.B. Statistical analysis: P.B., C.M., and EB. Writing (original draft): P.B.

formance in adults with poor baseline capacities regardless of attention-deficit/hyperac- Writing (review and editing): P.B., E.B., C.M., and D.C. Competing interests: D.C. has been, in the

Downloaded from https://www.science.org at Universidade Federal de Santa Maria on September 14, 2023

tivity disorder diagnosis. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 34, 261–265 (2014). past 3 years, a consultant to/member of the advisory board of and/or speaker for Takeda/Shire,

31. D. Campbell-Meiklejohn, A. Simonsen, J. Scheel-Krüger, V. Wohlert, T. Gjerløff, C. D. Frith, Medice, Novartis, and Servier and has received royalties from Oxford University Press and

R. D. Rogers, A. Roepstorff, A. Møller, In for a penny, in for a pound: Methylphenidate Cambridge University Press. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

reduces the inhibitory effect of high stakes on persistent risky choice. J. Neurosci. 32, Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are

13032–13038 (2012). present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Data and programs to reproduce all

results can be found at https://zenodo.org/badge/latestdoi/592775835.

32. S. R. Schroeder, K. Mann-Koepke, C. T. Gualtieri, D. A. Eckerman, G. R. Breese, Methylphe-

nidate affects strategic choice behavior in normal adult humans. Pharmacol. Biochem.

Submitted 9 June 2022

Behav. 28, 213–217 (1987).

Accepted 8 May 2023

33. C. Bellebaum, L. Kuchinke, P. Roser, Modafinil alters decision making based on feedback

Published 14 June 2023

history—A randomized placebo-controlled double blind study in humans.

10.1126/sciadv.add4165

J. Psychopharmacol. 31, 243–249 (2017).

34. D. C. Turner, T. W. Robbins, L. Clark, A. R. Aron, J. Dowson, B. J. Sahakian, Cognitive en-

hancing effects of modafinil in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology 165,

260–269 (2003).

Bowman et al., Sci. Adv. 9, eadd4165 (2023) 14 June 2023 8 of 8

Not so smart? “Smart” drugs increase the level but decrease the quality of

cognitive effort

Elizabeth Bowman, David Coghill, Carsten Murawski, and Peter Bossaerts

Sci. Adv., 9 (24), eadd4165.

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.add4165

Downloaded from https://www.science.org at Universidade Federal de Santa Maria on September 14, 2023

View the article online

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.add4165

Permissions

https://www.science.org/help/reprints-and-permissions

Use of this article is subject to the Terms of service

Science Advances (ISSN ) is published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. 1200 New York Avenue NW,

Washington, DC 20005. The title Science Advances is a registered trademark of AAAS.

Copyright © 2023 The Authors, some rights reserved; exclusive licensee American Association for the Advancement of Science. No claim

to original U.S. Government Works. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (CC BY).

You might also like

- Examine Com Stack Guide Libido and Sexual EnhancementDocument16 pagesExamine Com Stack Guide Libido and Sexual Enhancementrichard100% (1)

- Adderall-Safer Than AspirinDocument2 pagesAdderall-Safer Than AspirinChristopher RhudyNo ratings yet

- Speed - Miriam JosephDocument97 pagesSpeed - Miriam JosephLone Hansen100% (1)

- Venvanse Faz MalDocument9 pagesVenvanse Faz MalFlavio BenignoNo ratings yet

- Mikhael Et Al 2021 Rational Inattention and Tonic DopamineDocument35 pagesMikhael Et Al 2021 Rational Inattention and Tonic Dopamineopenid_D33Ajw2MNo ratings yet

- Biology: Pharmacological Evidence For The Implication of Noradrenaline in EffortDocument26 pagesBiology: Pharmacological Evidence For The Implication of Noradrenaline in EffortJuan David Pardo Mr. PostmanNo ratings yet

- Biology: Pharmacological Evidence For The Implication of Noradrenaline in EffortDocument26 pagesBiology: Pharmacological Evidence For The Implication of Noradrenaline in EffortJuan David Pardo Mr. PostmanNo ratings yet

- Dopamine Promotes Cognitive Effort by Biasing The Benefits Versus Costs of Cognitive WorkDocument6 pagesDopamine Promotes Cognitive Effort by Biasing The Benefits Versus Costs of Cognitive WorkAlma AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Attention Restoration Theory II A Systematic Review To Clarify Attention Processes Affected by Exposure To Natural EnvironmentsDocument43 pagesAttention Restoration Theory II A Systematic Review To Clarify Attention Processes Affected by Exposure To Natural EnvironmentsbobNo ratings yet

- Studyprotocol Open Access: Lopes Et Al. Trials (2022) 23:87Document14 pagesStudyprotocol Open Access: Lopes Et Al. Trials (2022) 23:87Rogério MelaréNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Control in Media Multitaskers: Two Replication Studies and A Meta-AnalysisDocument22 pagesCognitive Control in Media Multitaskers: Two Replication Studies and A Meta-Analysismargaretha kedjoNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Benefits of Interacting With NatureDocument6 pagesCognitive Benefits of Interacting With NatureJames KivinduNo ratings yet

- Nutrition - Ginseng and BacopaDocument10 pagesNutrition - Ginseng and BacopaSynapgen ArticlesNo ratings yet

- HowDoesVisualPraxisBasedOccupationalTherapyProgrameffectMotorSkillsinchildrenwithHyperactivityandAttentionDisorder Singleblindrandomisedstudydesign1106348-2386005 PDFDocument7 pagesHowDoesVisualPraxisBasedOccupationalTherapyProgrameffectMotorSkillsinchildrenwithHyperactivityandAttentionDisorder Singleblindrandomisedstudydesign1106348-2386005 PDFAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- ML in DBS Systematic Review PreprintDocument20 pagesML in DBS Systematic Review PreprintBen AllenNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3Document12 pagesLesson 3presizoNo ratings yet

- ACR o noACRDocument10 pagesACR o noACRNancy OlguínNo ratings yet

- Aphasia Recovery: When, How and Who To Treat?Document7 pagesAphasia Recovery: When, How and Who To Treat?Mohammed Dr.adjedNo ratings yet

- Complementaria 1. Aphasia Recovery When, How and Who To TreatDocument7 pagesComplementaria 1. Aphasia Recovery When, How and Who To TreatCarlonchaCáceresNo ratings yet

- Hacking The Brain - Dimensions of Cognitive Enhancement - ACS Chemical NeuroscienceDocument43 pagesHacking The Brain - Dimensions of Cognitive Enhancement - ACS Chemical Neurosciencepanther uploadsNo ratings yet

- Deep Action An Approach On The Basis of Deep Learning For The Prediction of Novel Drug-Target InteractionsDocument6 pagesDeep Action An Approach On The Basis of Deep Learning For The Prediction of Novel Drug-Target InteractionsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- NeuroOncolPract 2016 Carlson Green Nop npw015Document11 pagesNeuroOncolPract 2016 Carlson Green Nop npw015Elías Coreas SotoNo ratings yet

- Interventions To Improve Gross Motor Performance in Children With Neurodevelopmental Disorders A Meta AnalysisDocument16 pagesInterventions To Improve Gross Motor Performance in Children With Neurodevelopmental Disorders A Meta AnalysissilNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Uc BerkeleyDocument8 pagesDissertation Uc BerkeleySecondarySchoolReportWritingSiouxFalls100% (1)

- Forough I 2016Document5 pagesForough I 2016Katherine HunterNo ratings yet

- Sample Size - How Many PartcipantsDocument7 pagesSample Size - How Many PartcipantsAKNTAI002No ratings yet

- A Guide To Deep Learning in Healthcare: Nature Medicine January 2019Document7 pagesA Guide To Deep Learning in Healthcare: Nature Medicine January 2019Buster FoxxNo ratings yet

- CL ThesisDocument4 pagesCL Thesistiffanycarpenterbillings100% (2)

- Thesis On Buccal Drug Delivery SystemDocument5 pagesThesis On Buccal Drug Delivery SystemWhereToBuyWritingPaperUK100% (2)

- 1 s2.0 S2666379121003694 MainDocument21 pages1 s2.0 S2666379121003694 MainAldera76No ratings yet

- JTC AutismDocument10 pagesJTC AutismSharvari ShahNo ratings yet

- The Association Between Adolescent Well-Being and Digital Technology UseDocument12 pagesThe Association Between Adolescent Well-Being and Digital Technology UseHelyana DíazNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence Makes Computers Lazy: Simon Kent, Nayna PatelDocument25 pagesArtificial Intelligence Makes Computers Lazy: Simon Kent, Nayna Patelt200586tNo ratings yet

- Research Papers On Neural Networks FreeDocument8 pagesResearch Papers On Neural Networks Freewzsatbcnd100% (1)

- Pesquisa Sobre Mente HumanaDocument31 pagesPesquisa Sobre Mente HumanaanjosemfaceNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Mechanisms in Numerical Processing: Evidence From Acquired DyscalculiaDocument51 pagesCognitive Mechanisms in Numerical Processing: Evidence From Acquired DyscalculiaDiane MxNo ratings yet

- Hi Rez ThesisDocument8 pagesHi Rez Thesisfd0kyjpa100% (2)

- Articulo en Ingles Mejor Informacion SIMPLE y ESPECIFICADocument23 pagesArticulo en Ingles Mejor Informacion SIMPLE y ESPECIFICAIván PachecoNo ratings yet

- Seddon2012 Article DrugDesignForEverFromHypeToHopDocument14 pagesSeddon2012 Article DrugDesignForEverFromHypeToHopChabahi SidlbachirNo ratings yet

- Thesis IteeDocument5 pagesThesis Iteejessicahillknoxville100% (2)

- Neuro-Oncology Practice Neuro-Oncology PracticeDocument10 pagesNeuro-Oncology Practice Neuro-Oncology PracticeCarolina Robledo CastroNo ratings yet

- Scheggiaetal Biol Psy 2013Document12 pagesScheggiaetal Biol Psy 2013Psikiatri 76 UndipNo ratings yet

- Capturing Human Categorization of Natural Images by Combining Deep Networks and Cognitive ModelsDocument14 pagesCapturing Human Categorization of Natural Images by Combining Deep Networks and Cognitive ModelsGokushimakNo ratings yet

- 1745 6215 14 306Document7 pages1745 6215 14 306sandra garcia molinaNo ratings yet

- SBDD An OverviewDocument16 pagesSBDD An OverviewAnkita SinghNo ratings yet

- Evaluation Measures For Children With Cerebral Palsy: Katja Groleger SršenDocument10 pagesEvaluation Measures For Children With Cerebral Palsy: Katja Groleger SršenYahia MoftahNo ratings yet

- Vanessa Murillo Ramírez - Cognitiva 03Document7 pagesVanessa Murillo Ramírez - Cognitiva 03Vanessa Murillo RamírezNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Behaviour ModificationDocument8 pagesLiterature Review On Behaviour Modificationc5sx83ws100% (1)

- Computer Simulation: Concept and Application in Formulation and DevelopmentDocument37 pagesComputer Simulation: Concept and Application in Formulation and DevelopmentSharanya ParamshettiNo ratings yet

- CDER Regulatory Newsletter - Issue III - 12142023 - 1-1Document8 pagesCDER Regulatory Newsletter - Issue III - 12142023 - 1-1Kristin MNo ratings yet

- The e Ect of Active Video Games On Cognitive Functioning in Clinical and Non-Clinical Populations A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled TrialsDocument10 pagesThe e Ect of Active Video Games On Cognitive Functioning in Clinical and Non-Clinical Populations A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled TrialsFaiz KunNo ratings yet

- Connectionist Formulation of LearningDocument6 pagesConnectionist Formulation of LearningRobert HillNo ratings yet

- Computer Aided Drug Design (Cadd) : Naresh.T M.Pharmacy 1 YR/1 SEMDocument40 pagesComputer Aided Drug Design (Cadd) : Naresh.T M.Pharmacy 1 YR/1 SEMJainendra JainNo ratings yet

- Rational Inattention in MiceDocument34 pagesRational Inattention in MicelunaNo ratings yet

- Dexamethasone ThesisDocument4 pagesDexamethasone Thesismaryburgsiouxfalls100% (1)

- Understanding Performance Deficits in Developmental Coordination Disorder ADocument12 pagesUnderstanding Performance Deficits in Developmental Coordination Disorder AAlba GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Mechanistic Understanding From Molecular DynamicsDocument102 pagesMechanistic Understanding From Molecular DynamicsCharaf EddineNo ratings yet

- CTN 04 00021Document21 pagesCTN 04 00021Lokeswara VijanapalliNo ratings yet

- Gaining-Sharing Knowledge Based Algorithm With Adaptive Parameters For Engineering OptimizationDocument13 pagesGaining-Sharing Knowledge Based Algorithm With Adaptive Parameters For Engineering OptimizationAli WagdyNo ratings yet

- 01 CNS Spectrum Pre Edit ProofDocument10 pages01 CNS Spectrum Pre Edit ProofMohamedYahyaNo ratings yet

- Ou Dissertation FormatDocument5 pagesOu Dissertation FormatOrderCustomPapersSiouxFalls100% (1)

- Science 2015 Farah 379 80Document3 pagesScience 2015 Farah 379 80Daniel Jesús Carrión DurandNo ratings yet

- Psychophysiological assessment of human cognition and its enhancement by a non-invasive methodFrom EverandPsychophysiological assessment of human cognition and its enhancement by a non-invasive methodNo ratings yet

- Jamainternal Bretthauer 2023 Oi 230055 1692040542.98105Document8 pagesJamainternal Bretthauer 2023 Oi 230055 1692040542.98105Flavio GuimaraesNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Quality Assurance in Radiation O 2023 Seminars in RadiatioDocument12 pagesThe Importance of Quality Assurance in Radiation O 2023 Seminars in RadiatioFlavio GuimaraesNo ratings yet

- Patient Reported Outcomes in Clinical Trials From An 2023 Seminars in RadiDocument9 pagesPatient Reported Outcomes in Clinical Trials From An 2023 Seminars in RadiFlavio GuimaraesNo ratings yet

- Real World Data Applications and Relevance To CA 2023 Seminars in RadiationDocument12 pagesReal World Data Applications and Relevance To CA 2023 Seminars in RadiationFlavio GuimaraesNo ratings yet

- Advances and Challenges in Conducting Clinical Tria 2023 Seminars in RadiatiDocument9 pagesAdvances and Challenges in Conducting Clinical Tria 2023 Seminars in RadiatiFlavio GuimaraesNo ratings yet

- Irradiação Eletiva MI, JAMA, 2021Document10 pagesIrradiação Eletiva MI, JAMA, 2021Flavio GuimaraesNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Health 9Document6 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in Health 9marvierose0% (1)

- Everything You Wanted To Know About ADHD But Forgot You Wanted To AskDocument76 pagesEverything You Wanted To Know About ADHD But Forgot You Wanted To AskPola PremNo ratings yet

- Second Periodical Examination in Mapeh 7: Immaculate Heart Academy of Dumalinao, IncDocument9 pagesSecond Periodical Examination in Mapeh 7: Immaculate Heart Academy of Dumalinao, IncRode Jane SumambanNo ratings yet

- Drug Education NotesDocument75 pagesDrug Education NotesJoshua D None-None100% (1)

- Legal HighsDocument8 pagesLegal HighsDanny Envision100% (1)

- Dangerous DrugsDocument9 pagesDangerous DrugsEarvin Recel GuidangenNo ratings yet

- Lecture Drug Education Vice Control 1 - 052122Document28 pagesLecture Drug Education Vice Control 1 - 052122Calvin Clark RamosNo ratings yet

- Matrix - Roadmap To RecoveryDocument3 pagesMatrix - Roadmap To RecoveryCCNo ratings yet

- Jiggar DrugsDocument3 pagesJiggar DrugsRockeven DesirNo ratings yet

- Drug Education and Vice ControlDocument302 pagesDrug Education and Vice ControlBautista John Mhar M.No ratings yet

- Unit 1 Alcohol Tobacco Drugs NotesDocument8 pagesUnit 1 Alcohol Tobacco Drugs NotesubNo ratings yet

- Anf MCQSDocument10 pagesAnf MCQSDanyal NadeemNo ratings yet

- Piracetam y PsicoestimulantesDocument3 pagesPiracetam y PsicoestimulantesArturo PerezNo ratings yet

- Module 3 NSTPDocument80 pagesModule 3 NSTPJamie Federizo100% (1)

- Drug Education and Vice ControlDocument8 pagesDrug Education and Vice ControlMagus Flavius91% (11)

- 3,4 Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV)Document37 pages3,4 Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV)Mike RohrichNo ratings yet

- DRUGSDocument2 pagesDRUGSchelcieariendeleonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Drug AddictionDocument14 pagesChapter 2 Drug AddictionJoash Normie DuldulaoNo ratings yet

- Principles in Using Psychotropic Medication in Children and AdolescentsDocument19 pagesPrinciples in Using Psychotropic Medication in Children and AdolescentsdragutinpetricNo ratings yet

- Truth About Crystalmeth Booklet en - enDocument24 pagesTruth About Crystalmeth Booklet en - enJen PaezNo ratings yet

- Drug Education and Vice ControlDocument115 pagesDrug Education and Vice ControlVincentNo ratings yet

- FC 106 (Lecture 4)Document17 pagesFC 106 (Lecture 4)Johnpatrick DejesusNo ratings yet

- Consequences of Psychoactive Substance AbuseDocument33 pagesConsequences of Psychoactive Substance AbuseAhmadu MohammedNo ratings yet

- Illicit Substances AAGBI 2013Document8 pagesIllicit Substances AAGBI 2013yuyoide6857No ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan in HealthDocument7 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in HealthAdonesNo ratings yet

- Assi, Sulaf Et Al. Exploring Consumer and Patient Knowledge, Behavior, and Attitude Toward Medicinal and Lifestyle Products Purchased From The Internet:A Web-Based SurveyDocument16 pagesAssi, Sulaf Et Al. Exploring Consumer and Patient Knowledge, Behavior, and Attitude Toward Medicinal and Lifestyle Products Purchased From The Internet:A Web-Based SurveyNova ErmawatiNo ratings yet

- Drugs of AbuseDocument21 pagesDrugs of AbuseEmily T. NonatoNo ratings yet