Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Purposive Sampling in A Qualitative Evidence Synth

Purposive Sampling in A Qualitative Evidence Synth

Uploaded by

Redjean CanatoyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Purposive Sampling in A Qualitative Evidence Synth

Purposive Sampling in A Qualitative Evidence Synth

Uploaded by

Redjean CanatoyCopyright:

Available Formats

Ames et al.

BMC Medical Research Methodology (2019) 19:26

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0665-4

RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access

Purposive sampling in a qualitative

evidence synthesis: a worked example from

a synthesis on parental perceptions of

vaccination communication

Heather Ames1,2* , Claire Glenton3 and Simon Lewin4,5

Abstract

Background: In a qualitative evidence synthesis, too much data due to a large number of studies can undermine

our ability to perform a thorough analysis. Purposive sampling of primary studies for inclusion in the synthesis is

one way of achieving a manageable amount of data. The objective of this article is to describe the development

and application of a sampling framework for a qualitative evidence synthesis on vaccination communication.

Methods: We developed and applied a three-step framework to sample studies from among those eligible for

inclusion in our synthesis. We aimed to prioritise studies that were from a range of settings, were as relevant as

possible to the review, and had rich data. We extracted information from each study about country and study

setting, vaccine, data richness, and study objectives and applied the following sampling framework:

1. Studies conducted in low and middle income settings

2. Studies scoring four or more on a 5-point scale of data richness

3. Studies where the study objectives closely matched our synthesis objectives

Results: We assessed 79 studies as eligible for inclusion in the synthesis and sampled 38 of these. First, we sampled

all nine studies that were from low and middle-income countries. These studies contributed to the least number of

findings. We then sampled an additional 24 studies that scored high for data richness. These studies contributed to

a larger number of findings. Finally, we sampled an additional five studies that most closely matched our synthesis

objectives. These contributed to a large number of findings.

Conclusions: Our approach to purposive sampling helped ensure that we included studies representing a wide

geographic spread, rich data and a focus that closely resembled our synthesis objective. It is possible that we may have

overlooked primary studies that did not meet our sampling criteria but would have contributed to the synthesis. For

example, two studies on migration and access to health services did not meet the sampling criteria but might have

contributed to strengthening at least one finding. We need methods to cross-check for under-represented themes.

Keywords: Purposive sampling, Qualitative evidence synthesis, Systematic review

* Correspondence: heather.ames@fhi.no

1

Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group, La Trobe University,

Melbourne, Australia

2

Division for Health Services, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Postboks

222 Skøyen, Sandakerveien 24C, inngang D11, 0213 Oslo, Norway

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

© The Author(s). 2019 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to

the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Ames et al. BMC Medical Research Methodology (2019) 19:26 Page 2 of 9

Background amongst review authors and methodologists about the

Qualitative evidence syntheses, also known as systematic best approach [13]. Options include sampling from the

reviews of qualitative research, aim to explore people’s range of eligible studies (similar to purposively sampling

perceptions and experiences of the world around them participants within primary qualitative research) or nar-

by synthesizing data from studies across a range of set- rowing the scope of the research question by, for ex-

tings. When well-conducted, a qualitative evidence syn- ample, geographic area or population. Suri [14] proposes

thesis provides an in-depth understanding of complex a range of different strategies that could be applied to

phenomena while focusing on the experiences and per- purposively sample for a qualitative evidence synthesis

ceptions of research participants and taking into consid- (see Table 1 for examples). These methods are adapted

eration other contextual factors [1]. Qualitative evidence from a list by Patton for primary research purposes [12].

synthesis first appeared as a methodology in the health A recent paper by Benoot, Hannes et al. gives a worked

sciences in the mid-1990s [2]. The approach is still rela- example of sampling for a qualitative evidence synthesis

tively rare compared to systematic reviews of interven- [15]. However, there are few other well-described exam-

tion effectiveness, but is becoming more common [3], ples of the use of these approaches and it is not yet clear

and organisations such as Cochrane are now undertak- which approaches are best suited to particular kinds of

ing these types of synthesis [4–6]. The ways in which synthesis, synthesis processes and questions.

these syntheses are conducted has evolved over the last The example of sampling for a qualitative evidence syn-

20 years and now includes a variety of approaches such thesis presented in this article is drawn from a Cochrane

as meta-ethnography, thematic analysis, narrative syn- qualitative evidence synthesis on parents’ and informal

thesis and realist synthesis [2, 7]. caregivers’ views and experiences of communication about

For some qualitative evidence synthesis questions, there routine childhood vaccination [5]. We understood at an

are a large number of primary qualitative studies available, early stage that the number of studies eligible for this syn-

and there are several examples of syntheses that include thesis would be high. As there was limited guidance on

more than 50 studies [8]. However, in contrast to reviews how to sample studies for inclusion in a qualitative evi-

of effectiveness, the inclusion of a large number of pri- dence synthesis, we had to explore ways of solving this

mary studies with a high volume of data is not necessarily methodological challenge. The objective of this paper is to

viewed as an advantage as it can threaten the quality of discuss the development and application of a sampling

the synthesis. There are a number of reasons for this: framework for a qualitative evidence synthesis on vaccin-

firstly, analysis of qualitative data requires a detailed en- ation communication and the lessons learnt.

gagement with text. However, large volumes of data make

this difficult to achieve, and can make it difficult to move Methods

from descriptive or aggregative analysis to more interpret- The objective of our qualitative evidence synthesis was

ive analysis. Similar to the argument made for primary to identify, appraise and synthesise qualitative studies ex-

qualitative research [9, 10], the more data a researcher has ploring parents’ and informal caregivers’ views and expe-

to synthesize, the less depth and richness they are likely to riences regarding the communication they receive about

be able to extract from the data. Furthermore, effective- childhood vaccinations and the manner in which they

ness reviews aim to be exhaustive in order to achieve stat- receive it [5]. To be eligible for inclusion in the synthe-

istical generalizability which requires certain procedures sis, studies had to have used qualitative methods of data

whereas qualitative evidence synthesis aim to understand collection and analysis; had parents or informal care-

the phenomenon of interest and how it plays out in a con- givers as participants; and had a focus on views and ex-

text. This requires gathering data from the various con- periences of information about childhood vaccination. In

texts and respondent groups relevant to understanding August 2016, we searched MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL

the phenomenon. This is done in a purposeful way to and Anthropology Plus for eligible studies. We chose

gather data relevant to answering the review question. these databases as we anticipated that they would pro-

Exhaustive searching and inclusion can undermine this vide the highest yield of results based on preliminary, ex-

understanding, as qualitative synthesis seek to achieve ploratory searches [5].

conceptual and not statistical generalizability. Seventy-nine studies met our eligibility criteria. We de-

The sampling of studies within qualitative evidence cided that this number of included studies was too large

syntheses is still a relatively new methodological strategy, to analyse adequately and discussed whether it would be

but is generally based on the same principles as those reasonable to limit our synthesis to specific settings or cer-

used to conduct sampling within primary qualitative re- tain types of childhood vaccines. However, we concluded

search [11, 12]. There has been little written on how best that narrowing the scope of the synthesis was not an ac-

to limit the number of included studies in a qualitative ceptable option as we were interested in identifying global

evidence synthesis and there is currently no agreement patterns concerning parental preferences for information.

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Ames et al. BMC Medical Research Methodology (2019) 19:26 Page 3 of 9

Table 1 Some examples of purposeful sampling methods [14]

Type of sampling Description

Extreme or deviant case sampling • Selecting illuminative cases that exemplify ‘extreme’ or ‘deviant’ contexts or examples, for instance:

– where an innovation in a primary study was perceived notably as a success or failure

– where findings of a primary study are very different from those of most studies identified

for the synthesis

Maximum variation sampling • Constructed by:

– identifying key dimensions of variation, and then

– finding cases that vary from each other as much as possible along these dimensions

• This sampling yields:

– ‘high-quality, detailed descriptions of each case, which are useful for documenting uniqueness, and

– important shared patterns that cut across cases and derive their significance from having emerged

out of heterogeneity’ (Patton, 2002, p. 235)

Snowball or chain sampling • Trying to locate a key work in the field through talking with experts or locating a key article that is

often cited

• Then follow on with primary studies that have cited the key or landmark study

Theoretical or operational • Selecting cases that represent important theoretical or operational constructs about the phenomenon

construct sampling of interest

• Set out operational definitions of key theories or constructs related to the phenomenon of interest

• Develop boundaries for these by creating specific inclusion and exclusion criteria in relation to selecting

primary studies for the synthesis

Criterion sampling • Used by those trying to construct a comprehensive understanding

• Studies are sampled based on a predetermined criteria

• Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria are clearly stated

• Studies are then analysed as a whole

Stratified purposeful sampling • Following on from criterion sampling where each of the criteria would become a sample

• Stratified samples are samples within samples where each stratum, or group, is fairly

homogenous and are analysed within these groups

• Useful for examining variation in a key phenomena of interest

Purposeful random sampling • Randomly select from the list of included studies for inclusion in the analysis

• For example, use a random internet based selector, choose every 3rd included study or pull

study names from a hat

• Provides an unbiased way of selecting studies for inclusion but may not provide studies with rich data

Combination or mixed • Choosing a combination or mix of sampling strategies to best fit your purpose

purposeful sampling – For some syntheses, it may be useful to use a combination or mix of sampling strategies.

For instance, by applying theoretical sampling in a first stage and deviant case sampling

in a second stage. This should be guided by the review methods and purpose, and the

time available

We mapped the eligible studies by extracting key informa- When considering how to achieve these goals, we

tion from each study, including information about coun- assessed all of the 16 purposeful sampling methods pro-

try, study setting, vaccine type, participants, research posed in the Suri study [14]. However, none of these dir-

methods and study objectives. This mapping of the in- ectly fit all of our needs although some of the methods

cluded studies also showed that it would be difficult to addressed some of these needs (See Table 6). We therefore

narrow by vaccine type as the majority of the studies did reshaped the approaches described in Suri, combining dif-

not state explicitly which vaccines the study encompassed ferent sampling strategies to create our own purposive

but focused instead on parents’ and caregivers’ views on sampling framework, as has been done by others [15].

childhood vaccination communication in general. We We developed the sampling framework taking into

therefore decided to sample from the included studies. consideration the data that had been mapped from the

Our main aim when sampling studies was to protect included studies and what would best fit with our re-

the quality of our analysis by ensuring that the amount search objective. The sampling framework was piloted

of data was manageable. However, we also wanted to en- on a group of ten studies and the review authors dis-

sure that the studies we sampled were the most suitable cussed challenges that arose. Our final, three-step sam-

for answering our objectives. As this was a global review, pling framework was as follows:

we were looking for studies that covered a broad range

of settings, including high, middle and low income Step 1: Sampling for maximum variation

countries. In addition, we wanted studies that were as Our focus was to develop a global understanding of the

close as possible to the topic of our synthesis and that phenomenon of interest, including similarities and dif-

had as rich data as possible. ferences across different settings. The majority of the

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Ames et al. BMC Medical Research Methodology (2019) 19:26 Page 4 of 9

studies that met the inclusion criteria took place in parental perceptions about vaccination information and

high-income settings. Our first step was therefore to communication but had not been sampled in the first two

sample all studies from low and middle-income coun- steps. For example, an article exploring what informs par-

tries. This helped us to ensure a geographic spread and ents’ decision making about childhood vaccination [18] was

reasonable representation of findings from all income not included in step 1 as it was not from a low or middle

settings. The inclusion of these studies was also import- income country or in step 2 as it scored a 3 for data rich-

ant because of the interest globally in improving vaccin- ness. It was sampled in step 3 as its focus on information

ation uptake in these settings, and this was also part of closely matched to the synthesis objectives.

the ‘Communicate to vaccinate’ project in which the We listed studies that met our inclusion criteria but

synthesis was embedded [16]. were not sampled into the analysis in a table in the pub-

lished qualitative evidence synthesis. The table provided

Step 2: Sampling for data richness the reason why the study was not sampled. This table pro-

Second, to ensure that we would have enough data for our vides readers with an overview of the existing research lit-

synthesis, we focused on the richness of the data within erature, makes our decision making process transparent

the remaining included studies. We based this decision on and allows readers to critically appraise our decisions.

the rationale that rich data can provide in-depth insights After the qualitative evidence synthesis was completed,

into the phenomenon of interest, allowing the researcher we mapped the step during which each study was sampled

to better interpret the meaning and context of findings and the number of findings to which each study had con-

presented in the primary studies [17]. To our knowledge tributed. (See Appendix 1) We did this to see if the step at

there is no existing tool to map data richness in qualitative which the study was sampled into the review had an impact

studies. We therefore created a simple 1–5 scale for asses- on the number of findings it contributed to; allowing us to

sing data richness (see Table 2). After assessing the data see if studies sampled for richer data or closeness to the re-

richness of the remaining included studies, we sampled all view objective did actually contribute to more findings.

studies that scored a 4 or higher for data richness. During the process of writing the qualitative evidence

synthesis, the review authors continued to discuss the

Step 3: Sampling for study scope / sampling for match of strengths and weaknesses of the approach used to iden-

scope tify the issues presented in this paper. We also presented

Finally, we anticipated that studies that closely matched our the approach to other teams doing qualitative evidence

objectives were likely to include data that was most valuable syntheses, and at conferences and meetings. These pre-

for the synthesis, even if those data were not very rich. sentations and ensuing discussions facilitated the identi-

After applying the first two sampling steps, we therefore ex- fication of other strengths and weaknesses of the

amined the studies that remained and sampled studies approach that we had used. (See Table 6).

where the study findings and objectives most closely

matched our synthesis objectives. Studies were eligible for Results

inclusion in the synthesis if they included at least one Seventy-nine studies were eligible for inclusion in the

theme regarding parental perceptions about vaccination synthesis. After applying our sampling framework, we

communication. However, many of these studies focused included thirty-eight studies.

on parental perceptions of vaccination or vaccination pro-

grams rather than on parental perceptions of vaccination Our experiences when applying the sampling framework

communication more specifically. In this final sampling The sampling approach we used in this review aimed to

step, we looked for studies that had primarily focused on achieve a range of settings, studies with rich data and studies

Table 2 Data richness scale used during sampling for Ames 2017 [5]

Score Measure Example

1 Very few qualitative data presented. Those For example, a mixed methods study using open ended survey questions or a more

findings that are presented are fairly descriptive detailed qualitative study where only part of the data relates to the synthesis objective

2 Some qualitative data presented For example, a limited number of qualitative findings from a mixed methods or

qualitative study

3 A reasonable amount of qualitative data For example, a typical qualitative research article in a journal with a smaller word

limit and often using simple thematic analysis

4 A good amount and depth of qualitative data For example, a qualitative research article in a journal with a larger word count that

includes more context and setting descriptions and a more in-depth presentation

of the findings

5 A large amount and depth of qualitative data For example, from a detailed ethnography or a published qualitative article

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Ames et al. BMC Medical Research Methodology (2019) 19:26 Page 5 of 9

with findings that matched our review objective. We aimed issue of relevance for LMIC contexts since the synthesis

to build a sampling framework that specifically addressed had a global perspective. However, this meant that stud-

and was in harmony with the synthesis objectives. ies with richer data from more privileged settings were

not sampled. To adjust for this the second step of sam-

Sampling means that we may miss articles with pling was directly linked to data richness. All studies

information about particular populations, settings, or scoring a 4 or higher for data richness were sampled.

interventions

One of the main challenges of using a sampling ap- Making decisions on how to assess data richness?

proach is that we are likely to have omitted data related Initially, we looked at the whole study when assessing

to particular populations, settings, communication strat- data richness. However, we realised that much of this

egies, vaccines or experiences. However, we argue that data covered topics that were outside of the scope of the

this approach allowed us to achieve a good balance be- synthesis. This included, for example, information on

tween the quality of the analysis and the range of set- parents perceptions of vaccines in general, advice they

tings and populations within the included studies. First had received from unofficial sources such as friends and

we will present a challenge related to setting and second neighbours and their thoughts about how susceptible

a challenge related to population. their children were to vaccine preventable diseases.

The first challenge we addressed was related to study We therefore adapted the data richness scale to com-

setting. Our sampling approach did not directly select bine steps 2 and 3 of our sampling framework. The end

studies conducted in high income countries, and this led result was a table where the richness of data in an in-

to some studies from these settings not being sampled. cluded study is not ranked by the total amount of data

However, we decided that geographic spread was an im- but by the amount of data that is relevant to the synthe-

portant factor for this global synthesis and sampled ac- sis objectives (see Table 3). This approach has since been

cordingly. This is a limitation of our sampling frame. used successfully in a new synthesis (Ames HMR, Glen-

However, we believe that it was a strength to have stud- ton C, Lewin S, Tamrat T, Akama E, Leon N: Patients

ies from a wider variety of settings to increase the rele- and peoples’ perceptions and experiences of targeted

vance of the findings to a larger number of contexts. digital communication accessible via mobile devices for

The second challenge relates to study population. Our reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent

sampling frame did not directly sample for variation in health: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Submitted).

study populations. One clear example of how studies

were missed that could have directly contributed to a Did the sampling step impact on how many findings a

finding related to a specific study population came with study contributed to?

the issue of migration and vaccination. It has been suggested that studies with richer data, also de-

Finding 6: Parents who had migrated to a new country scribed as conceptual clarity, may self-weight in the findings

had difficulty negotiating the new health system and of qualitative evidence syntheses (contribute more data to

accessing and understanding vaccination information. the synthesis) and be found to be more methodologically

We did not sample a few primary studies that dis- sound [19, 20]. In order to test this we mapped the step in

cussed migrant issues specifically, as they did not meet which the studies were sampled and the number of findings

the sampling criteria; specifically, they were not from each study contributed to. The rationale for this was that we

LMIC contexts, had thin data or did not closely match sampled studies that had a lower score for data richness in

the synthesis objectives. They most likely would have steps one and three. If these studies contributed to a dis-

contributed to strengthening at least the finding de- tinctly lower number of study findings this could reinforce

scribed above. the idea that studies with richer data (i.e. step two) contrib-

uted more data to more findings than studies with thinner

Our sampling framework meant that we may have data. To some extent this was the case with the studies sam-

sampled studies with thinner data pled in step one from low and middle-income contexts.

With our decision to focus on study location in step 1 of However, this did not apply as well to studies sampled in

our sampling we may have sampled studies from low step three where the study findings were more closely

and middle-income contexts that scored a 1 or 2 for aligned with the synthesis objectives. (See Table 4).

data richness (a potential weakness) and not sampled Nine studies from LMIC contexts were sampled in step

studies from high income settings with richer data. We one and these contributed to, on average, the least number

were unsure whether the amount of relevant data in the of synthesis findings. Twenty-four studies were sampled on

studies from low and middle-income settings would the basis of data richness in step two; these contributed to a

make a contribution to the synthesis and findings. In the large number of findings. The five studies sampled in step

end we decided to include these studies to address the three because their findings most closely matched the

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Ames et al. BMC Medical Research Methodology (2019) 19:26 Page 6 of 9

Table 3 Revised data richness table

Score Measure Example

1 Very little qualitative data presented that relate to the synthesis For example, a mixed methods study using open ended survey questions

objective. Those findings that are presented are fairly descriptive. or a more detailed qualitative study where only part of the data relates

to the synthesis objective

2 Some qualitative data presented that relate to the synthesis For example, a limited number of qualitative findings from a mixed

objective methods or qualitative study

3 A reasonable amount of qualitative data that relate to the For example, a typical qualitative research article in a journal with

synthesis objective a smaller word limit and often using simple thematic analysis

4 A good amount and depth of qualitative data that relate For example, a qualitative research article in a journal with a larger

to the synthesis objective word count that includes more context and setting descriptions and

a more in-depth presentation of the findings

5 A large amount and depth of qualitative data that relate For example, from a detailed ethnography or a published

in depth to the synthesis objective. qualitative article with the same objectives as the synthesis

synthesis objectives also contributed to a large number of worked well for the two syntheses we have used it in

findings. Table 4 shows the overview of how many studies and has been understandable to other authors as a lo-

were sampled in each step and how many findings the stud- gical tool for mapping how much relevant data is in each

ies contributed to (See additional file 1 for a detailed over- included study [21] (Ames HL N, Glenton C, Tamrat T,

view per study). Lewin S: Patients’ and clients’ perceptions and experi-

ences of targeted digital communication accessible via

Discussion mobile devices for reproductive, maternal, newborn,

We believe that our sampling framework allowed us to child and adolescent health: a qualitative evidence syn-

limit the number of studies included in the synthesis in thesis (protocol), unpublished) . However, objective test-

order to make analysis manageable, while still allowing ing of the scale would be needed to assess its validity

us to achieve the objectives of the synthesis. across research teams and to standardize its approach.

The decision to purposively sample primary studies for

inclusion in the qualitative evidence synthesis had its Working with the GRADE-CERQual approach to develop

strengths and weaknesses. It allowed us to achieve a suffi- sampling for qualitative evidence synthesis in the future

ciently wide geographic spread of primary studies while Qualitative evidence syntheses are increasingly using

limiting the number of studies included in the synthesis. It GRADE-CERQual (hereafter referred to as CERQual) to

enabled us to include studies with rich data and studies assess the confidence in their findings. CERQual aims to

that most closely resembled the synthesis objectives. How- transparently assess and describe how much confidence

ever, we may have overlooked primary studies that did not decision makers and other users can place in individual

meet the sampling criteria but would have contributed to synthesis findings from syntheses of qualitative evidence.

the synthesis. Furthermore, this qualitative evidence syn- Confidence in the evidence has been defined as an assess-

thesis used a thematic approach to synthesis. Different ment of the extent to which the synthesis finding is a rea-

synthesis approaches may have led us towards different sonable representation of the phenomenon of interest.

ways of sampling or have identified different findings. CERQual includes four components [22, 23] (Table 5).

The approach for assessing richness of data needs to We believe that purposive sampling would be useful to

be developed further and tested within other qualitative address concerns that arise during the CERqual process,

evidence syntheses to see if it needs adjustment. It has specifically regarding relevance and adequacy. However,

all four components could be taken into consideration

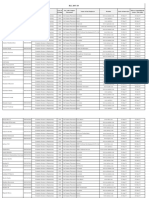

Table 4 Overview of sampling stage and contribution to findings

when developing a sampling frame.

for primary studies included in the Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

Relevance

Sampling step Number of studies Average and range of

that were sampled number of findings Relevance addresses a number of study characteristics (see

that these studies Additional file 2). It links to the approach we took in step 1

contributed to

to include a maximum variation of settings. Review authors

1- LMIC settings 9 6 (2–13) could use the relevance concept to design their sampling

2– Score of three or 24 13 (3–20) framework to address key study characteristics. A review

more for data richness

author could also return to the pool of included studies and

3– Closeness to the 5 13 (6–22) sample studies that would help to moderate downgrading

synthesis objectives

in relation to these concepts. For example, if a synthesis

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Ames et al. BMC Medical Research Methodology (2019) 19:26 Page 7 of 9

Table 5 The four components of CERQual [23, 7]

Methodological limitations The extent to which there are problems in the design or conduct of the primary studies that

contributed evidence to a synthesis finding

Coherence The extent to which the synthesis finding is well grounded in data from the contributing primary

studies and provides a convincing explanation for the patterns found in the data

Adequacy of data An overall determination of the degree of richness and quantity of data supporting a synthesis finding

Relevance The extent to which the body of evidence from the primary studies supporting a synthesis findings is

applicable to the context (perspective or population, phenomenon of interest, setting) specified in

the synthesis question

finding was downgraded for relevance as all of the studies Methodological limitations

were conducted in a specific context or geographic location A potential weakness of our approach is that we did not

the authors could go back and sample studies from other sample studies based on their methodological limita-

contexts to address relevance concerns. tions. This means that primary studies that were meth-

odologically weak may have been included in the

synthesis if they met our sampling criteria. This has im-

Adequacy plications for our CERQual assessment of confidence in

The adequacy component of CERQual links to our as- the evidence, as findings based on studies with import-

sessment of data richness. Is there enough data and rich ant methodological limitations are likely to be down-

data to support a synthesis finding? By sampling studies graded. Future syntheses could include methodological

with richer data we believe that adequacy could be limitations in a sampling framework. This could lead to

improved. higher confidence in some review findings. However, this

Related to the concepts of data richness and adequacy approach could also potentially lead us to sample even

of data is the concept of data saturation. Our aim was not fewer studies, which could have implications for other

to reach data saturation for each of the findings in the CERQual components, including our assessment of data

synthesis through sampling. It would be possible to de- adequacy or relevance. Another possible option is to

velop a sampling approach geared towards the concept of identify findings that have been downgraded due to con-

saturation however, this would be different from complet- cerns about the methodological limitations of the con-

ing sampling before the analysis stage of the synthesis. If tributing studies. Review authors could then choose to

you were to sample with the aim of saturation it would be look at the pool of well conducted studies that have not

natural to sample from your included primary studies dur- been sampled to see if any include data that could con-

ing the analysis process, in a sequential way. tribute to the finding and could therefore be sampled

Table 6 Different types of sampling methods and ways of using them

Type of sampling [14] Used or not used in this sampling Potential ways in which we could use it in future

framework

Extreme or deviant We did not use this type This approach could be very useful when setting out sampling for a review

case sampling of sampling in this review when the review question addresses why something did or did not work or

when re sampling after you have a set of findings i.e. when updating a review

Maximum variation Used to help create We used this to create the first step of our sampling frame. It could also be

sampling our sampling frame useful to apply when sampling for other variables such as intervention,

population or socioeconomic status.

Snowball or chain We did not use this type We believe that this approach could be used if there were key articles in the

sampling of sampling in this review field. However, it should still be supported by a systematic search and sampling.

Theoretical or operational We did not use this type Useful if performing a systematic review of different theoretical or operational

construct sampling of sampling in this review constructs. For example, theories of behaviour change as applied to different

smoking prevention programs.

Criterion sampling Used to help create We decided on the criterion that were central to our research objective and

our sampling frame created a sampling framework around them.

Stratified purposeful We did not use this type We have since used this approach in another review where we divided the studies

sampling of sampling in this review by population and then applied the same sampling frame to each population.

Purposeful random We did not use this type We do not regard random sampling as useful or appropriate when trying

sampling of sampling in this review to explore a specific phenomenon of interest

Combination or mixed Used to help create We combined different sampling methods to create our three step sampling

purposeful sampling our sampling frame frame that worked for our specific research objective

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Ames et al. BMC Medical Research Methodology (2019) 19:26 Page 8 of 9

into the synthesis. Further work is needed to explore the research also needs to be undertaken on how best to

advantages and disadvantages of these different options. rate data richness within qualitative primary studies.

A linked issue is that, to date, the best way in which to In conclusion, this systematic three-step approach to sam-

assess the methodological strengths and limitations of pling may prove useful to other qualitative evidence synthesis

qualitative research is still contested [7, 24]. We believe authors. However, based on our experience it could be nar-

that assessing the methodological strengths and limita- rowed to a two-step approach with the combination of data

tions of included studies is feasible and is an important richness and closeness to the synthesis objectives. Further

aspect of engaging with the primary studies included in steps could be added to address synthesis specific objectives

a synthesis [24]. We would also argue that most readers such as population or intervention. As more syntheses are

make judgements about the methodological strengths completed, the issue of sampling will arise more frequently

and limitations of qualitative studies that they are look- and so approaches that are more explicit need to be devel-

ing at, and that the tools available to assess this help to oped. Transparent and tested approaches to sampling for

make these judgements more transparent and system- synthesis of qualitative evidence are important to ensure the

atic. To be useful, these judgements need to be linked to reliability and trustworthiness of synthesis findings.

the synthesis findings, as part of a CERQual assessment

of confidence in the evidence. Additional files

Additional file 1: Overview of sampling stage and contribution to

Qualitative evidence synthesis updates findings for primary studies included in the Qualitative Evidence Synthesis .

This type of purposive sampling could also be useful This table presents an overview of each of the primary studies included in

the qualitative evidence synthesis, the stage at which they were sampled

during synthesis updates. In this case, a review author and how many findings each study contributes to. (DOCX 13 kb)

could sample studies from the pool of included studies Additional file 2: Study characteristics addressed in the CERQual

that would contribute to strengthening findings with concept of relevance. This table presents the different study

very low or low confidence. Further work is needed to charachteristics that can be addresses when applying the CERQual

concept of relevance. (DOCX 16 kb)

see how sampling processes and CERQual assessments

impact on each other. In Table 6 we present different

Acknowledgements

ways in which we believe different sampling methods Not applicable.

could be used in future synthesis.

In conducting the sampling for this synthesis and talk- Funding

ing with other qualitative evidence synthesis authors it The original synthesis was funded by the Research Council of Norway. This

paper has been funded by EPOC Norway as part of the Norwegian Institute

has become clear that more research and guidance are of Public Health.

needed around this topic. Review authors need to try

out different sampling methods and approaches and Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this

document the steps they took and how the sampling ap- published article.

proach worked out. It would be useful to conduct re-

search comparing different sampling approaches for the Authors’ contributions

HA wrote the draft of this paper with comment from CG and SL. All three are

same synthesis question and looking at whether these authors of the original qualitative evidence synthesis and were involved in

result in different findings. Finally, it is important that developing the sampling framework and sampling from the included studies.

better guidance is developed for review authors on how All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

to apply different sampling approaches when conducting Ethics approval and consent to participate

a qualitative evidence synthesis. Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Conclusions Not applicable.

We used purposive sampling to select 38 primary studies

Competing interests

for the data synthesis using a three step-sampling frame. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

We employed a sampling strategy, as seventy-nine stud-

ies were eligible for inclusion in the synthesis. We feel Publisher’s Note

that large numbers of studies can threaten the quality of Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in

the analysis in a qualitative evidence synthesis. We used published maps and institutional affiliations.

the sampling strategy to decrease the number of studies Author details

to a manageable number. 1

Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group, La Trobe University,

Going forward, there is a need for research into pur- Melbourne, Australia. 2Division for Health Services, Norwegian Institute of

Public Health, Postboks 222 Skøyen, Sandakerveien 24C, inngang D11, 0213

posive sampling for qualitative evidence synthesis to test Oslo, Norway. 3Cochrane Norway and the Informed Health Choices Research

the robustness of different sampling frameworks. More Centre, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Postboks 222 Skøyen,

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Ames et al. BMC Medical Research Methodology (2019) 19:26 Page 9 of 9

Sandakerveien 24C, inngang D11, 0213 Oslo, Norway. 4Cochrane EPOC group CERQual assessment of confidence and create a summary of qualitative

and the Informed Health Choices Research Centre, Norwegian Institute of findings table. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):10.

Public Health, Postboks 222 Skøyen, Sandakerveien 24C, inngang D11, 0213 23. Lewin S, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Carlsen B, Colvin CJ, Gülmezoglu M,

Oslo, Norway. 5Health Systems Research Unit, South African Medical Research Noyes J, Booth A, Garside R, Rashidian A. Using qualitative evidence in

Council, Tygerberg, South Africa. decision making for health and social interventions: an approach to assess

confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-

Received: 26 September 2018 Accepted: 14 January 2019 CERQual). PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001895.

24. Noyes J, Booth A, Flemming K, Garside R, Harden A, Lewin S, Pantoja T,

Hannes K, Cargo M, Thomas J. Cochrane qualitative and implementation

methods group guidance series—paper 3: methods for assessing

References methodological limitations, data extraction and synthesis, and confidence in

1. Saini M, Shlonsky A. Systematic synthesis of qualitative research. USA: OUP; 2012. synthesized qualitative findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:49–58.

2. Thorne S. Metasynthetic madness: what kind of monster have we created?

Qual Health Res. 2017;27(1):3–12.

3. Noyes J, Booth A, Cargo M, Flemming K, Garside R, Hannes K, Harden A,

Harris J, Lewin S, Pantoja T. Cochrane qualitative and implementation

methods group guidance series-paper 1: introduction. J Clin Epidemiol.

2017.

4. Glenton C, Colvin CJ, Carlsen B, Swartz A, Lewin S, Noyes J, Rashidian A.

Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of lay health worker

programmes to improve access to maternal and child health: qualitative

evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10(10).

5. Ames HM, Glenton C, Lewin S. Parents' and informal caregivers’ views and

experiences of communication about routine childhood vaccination: a

synthesis of qualitative evidence. Cochrane Libr. 2017.

6. Munabi-Babigumira SGC, Lewin S, Fretheim A, Nabudere H. Factors that

influence the provision of intrapartum and postnatal care by skilled birth

attendants in low- and middle-income countries: a qualitative evidence

synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11.

7. Noyes J, Booth A, Flemming K, Garside R, Harden A, Lewin S, Pantoja T,

Hannes K, Cargo M, Thomas J. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation

Methods Group guidance series—paper 3: methods for assessing

methodological limitations, data extraction and synthesis, and confidence in

synthesized qualitative findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:49–58.

8. Toye F, Seers K, Tierney S, Barker KL. A qualitative evidence synthesis to

explore healthcare professionals’ experience of prescribing opioids to

adults with chronic non-malignant pain. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):94.

9. Morse JM. Sampling in grounded theory. The SAGE handbook of grounded

theory. 2010:229–44.

10. Sandelowski M. Sample size in qualitative research. Research in nursing &

health. 1995;18(2):179–83.

11. Silverman D. Doing qualitative research: a practical handbook: SAGE

publications limited; 2013.

12. Quinn-Patton M. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. London:

Sage Publications; 2002.

13. Tranfield D, Denyer D, Smart P. Towards a methodology for developing

evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic

review. Br J Manag. 2003;14(3):207–22.

14. Suri H. Purposeful sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qual Res J.

2011;11(2):63–75.

15. Benoot C, Hannes K, Bilsen J. The use of purposeful sampling in a

qualitative evidence synthesis: a worked example on sexual adjustment to a

cancer trajectory. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):21.

16. The communicate to vaccinate project (COMMVAC) [www.commvac.com].

17. Popay J, Rogers A, Williams G. Rationale and standards for the systematic

review of qualitative literature in health services research. Qual Health Res.

1998;8(3):341–51.

18. Austvoll-Dahlgren A, Helseth S. What informs parents’ decision-making

about childhood vaccinations? J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(11):2421–30.

19. Atkins S, Lewin S, Smith H, Engel M, Fretheim A, Volmink J. Conducting a

meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: lessons learnt. BMC Med Res

Methodol. 2008;8(1):21.

20. Toye F, Seers K, Allcock N, Briggs M, Carr E, Andrews J, Barker K. ‘Trying to

pin down jelly’-exploring intuitive processes in quality assessment for meta-

ethnography. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):46.

21. Xyrichis A, Mackintosh NJ, Terblanche M, Bench S, Philippou J, Sandall J.

Healthcare stakeholders’ perceptions and experiences of factors affecting

the implementation of critical care telemedicine (CCT): qualitative evidence

synthesis. Cochrane Libr. 2017.

22. Lewin S, Bohren M, Rashidian A, Munthe-Kaas H, Glenton C, Colvin CJ,

Garside R, Noyes J, Booth A, Tunçalp Ö. Applying GRADE-CERQual to

qualitative evidence synthesis findings—paper 2: how to make an overall

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Terms and Conditions

Springer Nature journal content, brought to you courtesy of Springer Nature Customer Service Center GmbH (“Springer Nature”).

Springer Nature supports a reasonable amount of sharing of research papers by authors, subscribers and authorised users (“Users”), for small-

scale personal, non-commercial use provided that all copyright, trade and service marks and other proprietary notices are maintained. By

accessing, sharing, receiving or otherwise using the Springer Nature journal content you agree to these terms of use (“Terms”). For these

purposes, Springer Nature considers academic use (by researchers and students) to be non-commercial.

These Terms are supplementary and will apply in addition to any applicable website terms and conditions, a relevant site licence or a personal

subscription. These Terms will prevail over any conflict or ambiguity with regards to the relevant terms, a site licence or a personal subscription

(to the extent of the conflict or ambiguity only). For Creative Commons-licensed articles, the terms of the Creative Commons license used will

apply.

We collect and use personal data to provide access to the Springer Nature journal content. We may also use these personal data internally within

ResearchGate and Springer Nature and as agreed share it, in an anonymised way, for purposes of tracking, analysis and reporting. We will not

otherwise disclose your personal data outside the ResearchGate or the Springer Nature group of companies unless we have your permission as

detailed in the Privacy Policy.

While Users may use the Springer Nature journal content for small scale, personal non-commercial use, it is important to note that Users may

not:

1. use such content for the purpose of providing other users with access on a regular or large scale basis or as a means to circumvent access

control;

2. use such content where to do so would be considered a criminal or statutory offence in any jurisdiction, or gives rise to civil liability, or is

otherwise unlawful;

3. falsely or misleadingly imply or suggest endorsement, approval , sponsorship, or association unless explicitly agreed to by Springer Nature in

writing;

4. use bots or other automated methods to access the content or redirect messages

5. override any security feature or exclusionary protocol; or

6. share the content in order to create substitute for Springer Nature products or services or a systematic database of Springer Nature journal

content.

In line with the restriction against commercial use, Springer Nature does not permit the creation of a product or service that creates revenue,

royalties, rent or income from our content or its inclusion as part of a paid for service or for other commercial gain. Springer Nature journal

content cannot be used for inter-library loans and librarians may not upload Springer Nature journal content on a large scale into their, or any

other, institutional repository.

These terms of use are reviewed regularly and may be amended at any time. Springer Nature is not obligated to publish any information or

content on this website and may remove it or features or functionality at our sole discretion, at any time with or without notice. Springer Nature

may revoke this licence to you at any time and remove access to any copies of the Springer Nature journal content which have been saved.

To the fullest extent permitted by law, Springer Nature makes no warranties, representations or guarantees to Users, either express or implied

with respect to the Springer nature journal content and all parties disclaim and waive any implied warranties or warranties imposed by law,

including merchantability or fitness for any particular purpose.

Please note that these rights do not automatically extend to content, data or other material published by Springer Nature that may be licensed

from third parties.

If you would like to use or distribute our Springer Nature journal content to a wider audience or on a regular basis or in any other manner not

expressly permitted by these Terms, please contact Springer Nature at

onlineservice@springernature.com

You might also like

- Jaccp Journal of The American College of Clinical Pharmacy - 2021 - Adeoye Olatunde - Research and Scholarly MethodsDocument10 pagesJaccp Journal of The American College of Clinical Pharmacy - 2021 - Adeoye Olatunde - Research and Scholarly MethodsHunain AmirNo ratings yet

- Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis Solution Manual PDFDocument18 pagesApplied Multivariate Statistical Analysis Solution Manual PDFALVYAN ARIFNo ratings yet

- Methods For The Thematic SynthesisDocument10 pagesMethods For The Thematic SynthesisJuan camiloNo ratings yet

- Family Practice 1996 Marshall 522 6Document4 pagesFamily Practice 1996 Marshall 522 6Anwar AliNo ratings yet

- PUBH3305 Qualitative Assessment 2024 FinalDocument5 pagesPUBH3305 Qualitative Assessment 2024 FinalwriterkarimaNo ratings yet

- Characterising and Justifying Sample Size Sufficiency in Interview-Based StudiesDocument18 pagesCharacterising and Justifying Sample Size Sufficiency in Interview-Based StudiesTheGimhan123No ratings yet

- Mixed Methods: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis While Studying Patient-Centered Medical Home ModelsDocument6 pagesMixed Methods: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis While Studying Patient-Centered Medical Home Modelsnathan assefaNo ratings yet

- Advance Nursing ResearchDocument44 pagesAdvance Nursing ResearchJester RafolsNo ratings yet

- Pico, Picos, SpiderDocument10 pagesPico, Picos, SpiderramneekNo ratings yet

- MixedMethods 032513compDocument8 pagesMixedMethods 032513compJames LindonNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Characteristics of Context and Research Utilization in A Pediatric SettingDocument10 pagesThe Relationship Between Characteristics of Context and Research Utilization in A Pediatric SettingReynaldi Esa RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Meta Analysis and Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesDifference Between Meta Analysis and Literature ReviewqdvtairifNo ratings yet

- The Case Study Approach IvanDocument20 pagesThe Case Study Approach IvanAlexis Martinez ConstantinoNo ratings yet

- Thesis Using Mixed MethodsDocument4 pagesThesis Using Mixed Methodsafkodkedr100% (1)

- EssayoncompareandcontrastDocument14 pagesEssayoncompareandcontrastmehak guptaNo ratings yet

- Akshita Country EditedDocument41 pagesAkshita Country EditedniranjanNo ratings yet

- A Methodology For Systematic Mapping in Environmental SciencesDocument13 pagesA Methodology For Systematic Mapping in Environmental SciencesTham NguyenNo ratings yet

- Why and How Epidemiologists Should Use Mixed MethodsDocument11 pagesWhy and How Epidemiologists Should Use Mixed MethodsAndre LanzerNo ratings yet

- QUALITATIVE AND MIXED METHODS RESEARCH DESIGNS-revisonDocument3 pagesQUALITATIVE AND MIXED METHODS RESEARCH DESIGNS-revisondavid murimiNo ratings yet

- Writing The Proposal For A Qualitative Research Methodology ProjectDocument41 pagesWriting The Proposal For A Qualitative Research Methodology Projectrcaba100% (1)

- Nmims RMDocument13 pagesNmims RMMichelle SawantNo ratings yet

- CreswellDocument6 pagesCreswelldrojaseNo ratings yet

- s13063 019 3444 yDocument12 pagess13063 019 3444 yAlessandra BendoNo ratings yet

- Critique Qualitative Nursing Research PaperDocument7 pagesCritique Qualitative Nursing Research Papermwjhkmrif100% (1)

- NUSS 500 - English - Part4Document5 pagesNUSS 500 - English - Part4Suraj NaikNo ratings yet

- Meta Analysis in Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesMeta Analysis in Literature Reviewdafobrrif100% (1)

- Example Proposal of Literature ReviewDocument23 pagesExample Proposal of Literature ReviewSteven A'Baqr EgiliNo ratings yet

- Sampling For Qualitative ResearchDocument4 pagesSampling For Qualitative ResearchPaulo César López Barrientos0% (1)

- Rough DataDocument7 pagesRough Dataali raza malikNo ratings yet

- Critical Appraisal of A Cross-Sectional Study On Environmental HealthDocument2 pagesCritical Appraisal of A Cross-Sectional Study On Environmental HealthFaza Nurul WardhaniNo ratings yet

- Patient Education and Counseling: Nicky BrittenDocument5 pagesPatient Education and Counseling: Nicky BrittenEva MutiarasariNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Meta AnalysisDocument8 pagesLiterature Review Meta Analysisorlfgcvkg100% (1)

- Descriptions of Sampling Practices Within Five Approaches To Qualitative Research in Education and The Health SciencesDocument24 pagesDescriptions of Sampling Practices Within Five Approaches To Qualitative Research in Education and The Health SciencesAL FredNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Interventions To Improve Laboratory Requesting Patterns Among Primary Care Physicians: A Systematic ReviewDocument13 pagesThe Effectiveness of Interventions To Improve Laboratory Requesting Patterns Among Primary Care Physicians: A Systematic ReviewGNo ratings yet

- Pros and Cons of Mixed Methods of Stuty DesignDocument11 pagesPros and Cons of Mixed Methods of Stuty DesignTin WannNo ratings yet

- MEM-RM-Lec. 05.1Document48 pagesMEM-RM-Lec. 05.1Samah RadmanNo ratings yet

- Research Methods MPC 005Document21 pagesResearch Methods MPC 005shaila colacoNo ratings yet

- Patient Engagement in Research: A Systematic Review: Researcharticle Open AccessDocument9 pagesPatient Engagement in Research: A Systematic Review: Researcharticle Open Accessv_ratNo ratings yet

- Question One: Write A 200 Word Paragraph On Continued Professional Development in NursingDocument6 pagesQuestion One: Write A 200 Word Paragraph On Continued Professional Development in NursingChelsbelleNo ratings yet

- Meta AnalysisDocument9 pagesMeta AnalysisNuryasni NuryasniNo ratings yet

- Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of The Literature Regarding The Diagnosis of Sleep ApneaDocument4 pagesSystematic Review and Meta-Analysis of The Literature Regarding The Diagnosis of Sleep Apneafuhukuheseg2No ratings yet

- Quantitative ResearchDocument4 pagesQuantitative ResearchEve JohndelNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6. Qualitative and Quantitative Research MethodsDocument5 pagesChapter 6. Qualitative and Quantitative Research MethodsMariana BarreraNo ratings yet

- Kausalitas, Randomisasi, GeneralisasiDocument22 pagesKausalitas, Randomisasi, GeneralisasiGiriNo ratings yet

- Research SeriesDocument21 pagesResearch SeriesNefta BaptisteNo ratings yet

- Designing A Research Project: Randomised Controlled Trials and Their Principles J M KendallDocument21 pagesDesigning A Research Project: Randomised Controlled Trials and Their Principles J M KendallNefta BaptisteNo ratings yet

- Limitations Systematic Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesLimitations Systematic Literature Reviewc5rqq644100% (1)

- Soc 311 AssignmentDocument6 pagesSoc 311 AssignmentDavid Ekow NketsiahNo ratings yet

- Benchmark Evidence BasedDocument11 pagesBenchmark Evidence BasedPeterNo ratings yet

- Repository Framework N ResearcherDocument14 pagesRepository Framework N ResearcherzainabNo ratings yet

- Systematic Literature Review of Randomized Controlled TrialsDocument8 pagesSystematic Literature Review of Randomized Controlled Trialsc5ngamsdNo ratings yet

- Shinelle Research Article UpdatedDocument7 pagesShinelle Research Article UpdatedZeeshan HaiderNo ratings yet

- Evid Based Pract Final Feb 05Document41 pagesEvid Based Pract Final Feb 05Mus OubNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Simulation-Based Nursing Education Depending On Fidelity: A Meta-AnalysisDocument8 pagesEffectiveness of Simulation-Based Nursing Education Depending On Fidelity: A Meta-AnalysisSydney FeldmanNo ratings yet

- Writing The Proposal For A Qualitative Research Methodology ProjectDocument40 pagesWriting The Proposal For A Qualitative Research Methodology ProjectnurainNo ratings yet

- How To Read A Paper - Papers That Go Beyond Numbers (Qualitative Research) - The BMJDocument8 pagesHow To Read A Paper - Papers That Go Beyond Numbers (Qualitative Research) - The BMJGolshan MNNo ratings yet

- Population Based Healthcare ApproachesDocument3 pagesPopulation Based Healthcare Approachesainamajid598No ratings yet

- Running Head: Research Designs 1Document7 pagesRunning Head: Research Designs 1Zeeshan HaiderNo ratings yet

- Clinical Prediction Models: A Practical Approach to Development, Validation, and UpdatingFrom EverandClinical Prediction Models: A Practical Approach to Development, Validation, and UpdatingNo ratings yet

- Final Report With Off Campus Details - 2017-18Document11 pagesFinal Report With Off Campus Details - 2017-18Saravanan KumarNo ratings yet

- StatisticsDocument9 pagesStatisticsJennilyn Paguio CastilloNo ratings yet

- Class Viii Winter or Christmas Vacation Fun Work ScheduleDocument2 pagesClass Viii Winter or Christmas Vacation Fun Work Schedulekanishkpathak989No ratings yet

- Marketing Research: Exam Preparation MCQDocument44 pagesMarketing Research: Exam Preparation MCQshaukat74No ratings yet

- PPT07 - Discrete Data AnalysisDocument49 pagesPPT07 - Discrete Data AnalysisArkastra BhrevijanaNo ratings yet

- Soft ComputingDocument476 pagesSoft ComputingDj DasNo ratings yet

- Student Activity 6: The Hydrogen AtomDocument4 pagesStudent Activity 6: The Hydrogen AtomAnne Ketri Pasquinelli da FonsecaNo ratings yet

- Q2 WHLP Earth and Life Science Module 9Document3 pagesQ2 WHLP Earth and Life Science Module 9Sheena Shane CantelaNo ratings yet

- Students' Reasoning in Mathematics Textbook Task-SolvingDocument21 pagesStudents' Reasoning in Mathematics Textbook Task-SolvingHector VasquezNo ratings yet

- Carr, E. H. The Twenty Years' Crisis, 1919-1939Document14 pagesCarr, E. H. The Twenty Years' Crisis, 1919-1939ashpalaciosNo ratings yet

- Crisis and Critique 7 3 2020 The Year of The Virus SARS 2 COVID 19 2020Document252 pagesCrisis and Critique 7 3 2020 The Year of The Virus SARS 2 COVID 19 2020Alvaro Moreno HoffmannNo ratings yet

- Ecology Unit 1 PlannerDocument7 pagesEcology Unit 1 PlannertandonakshytaNo ratings yet

- BEd Social Studies 2013 14Document5 pagesBEd Social Studies 2013 14Amrin SayedNo ratings yet

- Landscape Ecological Modelling and The Effectiveness of Conservation Policy. Exploring The Impacts of Land Ownership PatternsDocument16 pagesLandscape Ecological Modelling and The Effectiveness of Conservation Policy. Exploring The Impacts of Land Ownership PatternsgimmiakNo ratings yet

- Pampanga State Agricultural University: Magalang, Pampanga College of EducationDocument11 pagesPampanga State Agricultural University: Magalang, Pampanga College of EducationMark MascardoNo ratings yet

- Teaching EntrepreneurshipDocument4 pagesTeaching EntrepreneurshipNaresh GuduruNo ratings yet

- Museums, Collections and Society: Yearbook 2020Document7 pagesMuseums, Collections and Society: Yearbook 2020Marcela CabralitNo ratings yet

- Khaleel, T. A. I. Z. H. (2017) - Controlling of Time-Overrun in Construction Projects in IraqDocument7 pagesKhaleel, T. A. I. Z. H. (2017) - Controlling of Time-Overrun in Construction Projects in IraqdimlouNo ratings yet

- Oreko 2021 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1107 012227Document11 pagesOreko 2021 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1107 012227yannikNo ratings yet

- PR 2 SLM-week-1-2Document14 pagesPR 2 SLM-week-1-2MaRlon Talactac Onofre100% (1)

- TST CT119-3-2-Data Mining and Predictive Modelling (VE1)Document1 pageTST CT119-3-2-Data Mining and Predictive Modelling (VE1)Spam UseNo ratings yet

- First Principal of EducationDocument240 pagesFirst Principal of EducationKhilafatMediaNo ratings yet

- TPC 1Document19 pagesTPC 1Michael P. CelisNo ratings yet

- SHERLOCK HOLMES Teachers-GuideDocument20 pagesSHERLOCK HOLMES Teachers-GuideNazya TajNo ratings yet

- Fischof& MagregorDocument18 pagesFischof& MagregorDana MunteanNo ratings yet

- KNAPP, P. (1985) The Question of Hegelian Influence Upon Durkheim's SociologyDocument15 pagesKNAPP, P. (1985) The Question of Hegelian Influence Upon Durkheim's SociologyJuca BaleiaNo ratings yet

- 4 Blavatsky's WritingsDocument120 pages4 Blavatsky's Writingschaitanya518No ratings yet

- Roberto Assagioli - Founder of PsychosynthesisDocument3 pagesRoberto Assagioli - Founder of PsychosynthesisstresulinaNo ratings yet

- Materi Ob Chapter 1 TranslateDocument31 pagesMateri Ob Chapter 1 TranslatenurjannahNo ratings yet

- CS111 Introduction To ComputingDocument11 pagesCS111 Introduction To ComputingRoderickNo ratings yet