Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

43 viewsCharles Worth

Charles Worth

Uploaded by

Tiago SousaThis document discusses Charles Frederick Worth and John Redfern, two pioneering figures in modern fashion from the late 19th century. It summarizes Worth's rise from a fabric merchant in London to a leading couturier in Paris, gaining fame by dressing Princess Pauline Metternich and Empress Eugenie. However, recent scholarship casts doubt on details of this origin story. Meanwhile, across the English Channel, John Redfern was transforming his drapery shop on the Isle of Wight into a prominent dressmaking business that came to rival Worth's in importance, gaining royal patronage from Queen Victoria. The document examines how both Worth and Redfern helped shape 20th century fashion through the businesses that continued their legacies

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Atestat Engleza - FashionDocument18 pagesAtestat Engleza - FashionMariaNo ratings yet

- Costumes in Romeo and Juliet - 3Document16 pagesCostumes in Romeo and Juliet - 3for.peterbtopenworld.comNo ratings yet

- Charles Frederick WorthDocument1 pageCharles Frederick WorthАмина ДемешеваNo ratings yet

- Charles Frederick WorthDocument4 pagesCharles Frederick WorthPriyanka BoseNo ratings yet

- Early Career: Historic PortraitsDocument6 pagesEarly Career: Historic PortraitsTóth IldiNo ratings yet

- The Court-Balls of Marie AntoinetteDocument8 pagesThe Court-Balls of Marie Antoinettedanielson3336888No ratings yet

- History of FashionDocument306 pagesHistory of FashionyaqshanNo ratings yet

- 'I'Mimlijmmmli M MK AmuDocument234 pages'I'Mimlijmmmli M MK AmuMarian MorganNo ratings yet

- French and English furniture distinctive styles and periods described and illustratedFrom EverandFrench and English furniture distinctive styles and periods described and illustratedNo ratings yet

- Week 1Document54 pagesWeek 1YINGGCHI LONGNo ratings yet

- French and English furniture distinctive styles and periods: Illustrated EditionFrom EverandFrench and English furniture distinctive styles and periods: Illustrated EditionNo ratings yet

- Victorian and Edwardian Fashions from "La Mode Illustrée"From EverandVictorian and Edwardian Fashions from "La Mode Illustrée"Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- GC-203 Assignment RISHABHDocument24 pagesGC-203 Assignment RISHABHKaushik GuptaNo ratings yet

- Authentic French Fashions of the Twenties: 413 Costume Designs from "L'Art Et La Mode"From EverandAuthentic French Fashions of the Twenties: 413 Costume Designs from "L'Art Et La Mode"Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Rose Bertin, The Creator of Fashion at The Court of Marie-Antoinette 1913Document380 pagesRose Bertin, The Creator of Fashion at The Court of Marie-Antoinette 1913Kassandra M Journalist100% (3)

- Modern Bookbindings Their Design Decoration PDFDocument214 pagesModern Bookbindings Their Design Decoration PDFpamela4122No ratings yet

- Paris The Capital of FashionDocument181 pagesParis The Capital of Fashionjenniferkhole0033No ratings yet

- Vathekarabiantal00beck PDFDocument148 pagesVathekarabiantal00beck PDFSalomon SachsNo ratings yet

- Louis XIV's Architect: Louis Le Vau, France's Most Important BuilderFrom EverandLouis XIV's Architect: Louis Le Vau, France's Most Important BuilderNo ratings yet

- A Concise History of French Painting (Edward Lucie-Smith)Document296 pagesA Concise History of French Painting (Edward Lucie-Smith)Pushpita GhoseNo ratings yet

- Gautier Chivalry PDFDocument518 pagesGautier Chivalry PDFΔημητρης ΙατριδηςNo ratings yet

- Seeing Europe with Famous Authors, Volume 4 France and the Netherlands, Part 2From EverandSeeing Europe with Famous Authors, Volume 4 France and the Netherlands, Part 2No ratings yet

- Victorian Fashions and Costumes from Harper's Bazar, 1867-1898From EverandVictorian Fashions and Costumes from Harper's Bazar, 1867-1898Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Family of DariusDocument5 pagesThe Family of DariusaustinNo ratings yet

- 2014 - Spring - 4 - Barringer SarahDocument5 pages2014 - Spring - 4 - Barringer SarahcesiahdezNo ratings yet

- Fashion History FybaDocument31 pagesFashion History FybaHenishaNo ratings yet

- Exercise 7: Match The Pairs of Sentences From The Columns and Combine Them With TheDocument6 pagesExercise 7: Match The Pairs of Sentences From The Columns and Combine Them With TheАлександраNo ratings yet

- Queen Elizabeth II: A Lifetime Dressing for the World StageFrom EverandQueen Elizabeth II: A Lifetime Dressing for the World StageRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Rise of French Monarchical Power Dominated by Louis XivDocument39 pagesThe Rise of French Monarchical Power Dominated by Louis XivRajesh Kumar RamanNo ratings yet

- The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 14, No. 384, August 8, 1829From EverandThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 14, No. 384, August 8, 1829No ratings yet

- CRINOLINE 1840-1865 (The French Word For Horsehair) The Age of Optimism The Industrial RevolutionDocument113 pagesCRINOLINE 1840-1865 (The French Word For Horsehair) The Age of Optimism The Industrial Revolutiontairos555No ratings yet

- Van Dyck A Collection Of Fifteen Pictures And A Portrait Of The Painter With Introduction And InterpretationFrom EverandVan Dyck A Collection Of Fifteen Pictures And A Portrait Of The Painter With Introduction And InterpretationNo ratings yet

- Herbert Norris - Medieval Costume and FashionDocument564 pagesHerbert Norris - Medieval Costume and FashionOvidiu100% (3)

- The History of the Caliph VathekDocument447 pagesThe History of the Caliph VathekKanad Prajna DasNo ratings yet

- Rosalba CarrieraDocument5 pagesRosalba CarrieraGeorgiaNo ratings yet

- The Story of Versailles by Payne, Francis LoringDocument67 pagesThe Story of Versailles by Payne, Francis LoringGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- New Welsh Reader: A Casual Archaeology: New Welsh Reader 129 (New Welsh Review Summer 2022)From EverandNew Welsh Reader: A Casual Archaeology: New Welsh Reader 129 (New Welsh Review Summer 2022)No ratings yet

- 1900 Fashion HistoryDocument37 pages1900 Fashion HistoryRanjan NishanthaNo ratings yet

- Jessie Raven Crosland - Medieval French Literature-Blackwell (1956)Document276 pagesJessie Raven Crosland - Medieval French Literature-Blackwell (1956)Fulvidor Galté OñateNo ratings yet

- Rose Bertin - WikipediaDocument5 pagesRose Bertin - WikipediaBrayan Anderson Chumpen CarranzaNo ratings yet

- Architectural Record Magazine AR 1905 12 CompressedDocument86 pagesArchitectural Record Magazine AR 1905 12 CompressedMarco MilazzoNo ratings yet

- Illuminated illustrations of Froissart; Selected from the ms. in the British museumFrom EverandIlluminated illustrations of Froissart; Selected from the ms. in the British museumNo ratings yet

- Dutch and Flemish FurnitureDocument490 pagesDutch and Flemish Furniturebr657493080No ratings yet

- Verdi: Man and Musician: His Biography with Especial Reference to His English ExperiencesFrom EverandVerdi: Man and Musician: His Biography with Especial Reference to His English ExperiencesNo ratings yet

- Fashion HistoryDocument40 pagesFashion HistoryAo OkamiNo ratings yet

- No Recipe Old Recipe PSC v01 20230812 T203926Document36 pagesNo Recipe Old Recipe PSC v01 20230812 T203926ShovonNo ratings yet

- Lacoste Reebok ComparatieDocument27 pagesLacoste Reebok Comparatiedrinky381No ratings yet

- CrystalshapesDocument7 pagesCrystalshapesapi-276687098No ratings yet

- Clothes Test 4. RocDocument1 pageClothes Test 4. Rocviki palikovaNo ratings yet

- Final Listening Test I2Document1 pageFinal Listening Test I2LUIS FERNANDO VICTORIA ROJASNo ratings yet

- Tasmanian Craft Fair Program 2017Document28 pagesTasmanian Craft Fair Program 2017The ExaminerNo ratings yet

- Rapture by Pat BravoDocument40 pagesRapture by Pat BravoArt Gallery FabricsNo ratings yet

- Met GalaDocument2 pagesMet GalaNico RomaniNo ratings yet

- Swiss ArabianDocument101 pagesSwiss ArabianKiran MoreNo ratings yet

- Science Fair 5 2Document12 pagesScience Fair 5 2api-230330590No ratings yet

- Camden Fashion: Video UK - Exercises: PreparationDocument2 pagesCamden Fashion: Video UK - Exercises: PreparationVeronika SrncováNo ratings yet

- Super Character Design Amp Amp Poses Vol 2 HeroiDocument123 pagesSuper Character Design Amp Amp Poses Vol 2 HeroiCésar Narvaez100% (6)

- Golic VulcanDocument12 pagesGolic VulcanmarkjujuNo ratings yet

- 30 Day Gratitude Journal - Isabelle MoonDocument16 pages30 Day Gratitude Journal - Isabelle MoonAlberto GarciaNo ratings yet

- The Significance of Your Graduation TogaDocument2 pagesThe Significance of Your Graduation TogaDominicSavioNo ratings yet

- PerfumesDocument10 pagesPerfumesMohamed ElaskalnyNo ratings yet

- Style YourselfDocument56 pagesStyle YourselfWeldon Owen Publishing100% (8)

- Medium Manufacturer-Jewellery 2020Document25 pagesMedium Manufacturer-Jewellery 2020piv.hpNo ratings yet

- What Are You Like? What's He Like? What's She Like?Document9 pagesWhat Are You Like? What's He Like? What's She Like?Adelaida Ruiz VelandiaNo ratings yet

- Majalah Dewasa Format PDF Weekly PlayboyDocument1 pageMajalah Dewasa Format PDF Weekly PlayboyEmmanuel Louise de Guzman100% (1)

- Art NouveauDocument40 pagesArt NouveauUtsav AnuragNo ratings yet

- Chapter..2 KinesicsDocument33 pagesChapter..2 Kinesicsservice1234No ratings yet

- Bennett, Cherie - Sunset Island 001 - Sunset IslandDocument75 pagesBennett, Cherie - Sunset Island 001 - Sunset IslandIngy Al KafrawyNo ratings yet

- HFT 2223 Socio-Cultural & Psychological Aspects in Fashion Assgn.Document50 pagesHFT 2223 Socio-Cultural & Psychological Aspects in Fashion Assgn.Carolyn Morang'aNo ratings yet

- The History of Fashion (PDFDrive)Document369 pagesThe History of Fashion (PDFDrive)dani gogoNo ratings yet

- Fashion Show Types & ChoregraphyDocument4 pagesFashion Show Types & ChoregraphyD Babu Kosmic100% (3)

- Handbook of Furniture StylesDocument182 pagesHandbook of Furniture Stylesproteor_srl100% (8)

- Personal-Grooming VikDocument24 pagesPersonal-Grooming Vikvik_pk12No ratings yet

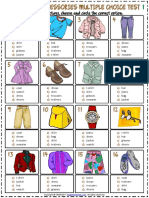

- Clothes and Accessories Vocabulary Esl Multiple Choice Tests For KidsDocument4 pagesClothes and Accessories Vocabulary Esl Multiple Choice Tests For KidsIhsan OzoraNo ratings yet

- Wedding Details For Planners ChecklistDocument7 pagesWedding Details For Planners ChecklistLizette SyNo ratings yet

Charles Worth

Charles Worth

Uploaded by

Tiago Sousa0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

43 views10 pagesThis document discusses Charles Frederick Worth and John Redfern, two pioneering figures in modern fashion from the late 19th century. It summarizes Worth's rise from a fabric merchant in London to a leading couturier in Paris, gaining fame by dressing Princess Pauline Metternich and Empress Eugenie. However, recent scholarship casts doubt on details of this origin story. Meanwhile, across the English Channel, John Redfern was transforming his drapery shop on the Isle of Wight into a prominent dressmaking business that came to rival Worth's in importance, gaining royal patronage from Queen Victoria. The document examines how both Worth and Redfern helped shape 20th century fashion through the businesses that continued their legacies

Original Description:

History of Charles Worth

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document discusses Charles Frederick Worth and John Redfern, two pioneering figures in modern fashion from the late 19th century. It summarizes Worth's rise from a fabric merchant in London to a leading couturier in Paris, gaining fame by dressing Princess Pauline Metternich and Empress Eugenie. However, recent scholarship casts doubt on details of this origin story. Meanwhile, across the English Channel, John Redfern was transforming his drapery shop on the Isle of Wight into a prominent dressmaking business that came to rival Worth's in importance, gaining royal patronage from Queen Victoria. The document examines how both Worth and Redfern helped shape 20th century fashion through the businesses that continued their legacies

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

43 views10 pagesCharles Worth

Charles Worth

Uploaded by

Tiago SousaThis document discusses Charles Frederick Worth and John Redfern, two pioneering figures in modern fashion from the late 19th century. It summarizes Worth's rise from a fabric merchant in London to a leading couturier in Paris, gaining fame by dressing Princess Pauline Metternich and Empress Eugenie. However, recent scholarship casts doubt on details of this origin story. Meanwhile, across the English Channel, John Redfern was transforming his drapery shop on the Isle of Wight into a prominent dressmaking business that came to rival Worth's in importance, gaining royal patronage from Queen Victoria. The document examines how both Worth and Redfern helped shape 20th century fashion through the businesses that continued their legacies

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 10

Heritage and Innovation: but despite his efforts to simplify women’s

daytime clothes the usual effect was heavily

Charles Frederick Worth, draped and fringed, and as stuffily claustro-

phobic as the gewgaw-cluttered interiors

John Redfern, and the associated with Victorian English taste”.

Dawn of Modern Fashion The Kyoto Costume Institutes 2002 publi-

cation of fashions from the 18th through the

Daniel James Cole 20th Centuries includes a short, partially

accurate biography Redfern but with erro-

neous life dates that would have him

opening his business around the age of 5.

Recent scholarship creates a different pic-

ture of both Worth and Redfern. Pivotal to

the history of clothing, Redfern’s story is

only recently being rediscovered, and only

in the past few years has a proper explo-

ration and assessment begun (primarily by

the work of Susan North). North (2008)

puts forward the thesis that in the late 19th

century, Redfern and Sons was of equal

importance to the House of Worth. It is

even possible to assert that Redfern, and his

legacy, were actually of greater importance

as shapers of 20th Century styles. An exam-

ination of Redfern and Redfern Ltd., in

Charles Frederick Worth’s story has been comparison to their contemporaries, calls

told often and is familiar to fashion schol- into question not only the preeminence of

ars. But while Worth has enjoyed a place of Worth, but also aspects of the careers of Paul

significance in fashion history, the story of Poiret and Gabrielle Chanel.

his contemporary, John Redfern has been The following explores how Worth and

ignored, or at best reduced to mere footnote Redfern, in different ways, shaped the tastes

status. Nearly all well-known fashion and fashion system of the 20th Century –

history survey texts give coverage of Worth, themselves, and through the businesses that

but scant – if any – mention of Redfern. bore their names after their deaths. Their

Contini, Payne, Laver, and Tortora and are intertwined with the major styles of the

Eubank, all ignore Redfern. Millbank second half of the Nineteenth Century, and

Rennolds, in Couture, the Great Designers their stories are interwoven with important

omits Redfern while including some fashion icons of the time, and demonstrate

markedly less important designers. Boucher the power of celebrity clientele to the suc-

includes John Redfern, but distills his career cess of a design house. Both Englishmen,

to a brief, mostly accurate, paragraph. In Worth and Redfern founded family busi-

Fashion, The Mirror of History, the nesses; both men died in 1895 and both left

Batterberrys interpret a Redfern plate as: there business in the control of sons and

“Another Englishman, working in Paris, the junior partners. But in addition to their

tailor Redfern, had devised a neat “tailor- similarities, their stories emphasize their

made” suit with a short jacket for women, differences.

Charles Frederick Worth, and Worth & France, in 1859. Worth set his sights on the

Bobergh princess’s business; Mme. Worth paid a call

to Princess Metternich, and extraordinarily,

Charles Frederick Worth is acknowledged was received. Mme Worth presented the

as the father of couture, rising from the princess a folio of designs and the Princess

ranks of a notable fabric and dress business ordered two dresses, wearing one to court at

in Paris, to leading his own house. As the the Tuileries Palace. “I wore my Worth

story goes, Worth was catapulted to success dress, and can say… that I have never seen a

by the court of the Second Empire. The more beautiful gown... it was made of white

story of Worth’s rise to fame, and his associ- tulle strewn with tiny silver discs and

ations with Princess Pauline Metternich trimmed with crimson-hearted daisies…

and Empress Eugenie, is a familiar tale but Hardly had the Empress entered the

one that has been embellished, even twisted throne-room…than she immediately

over time, beginning with the rather mythic noticed my dress, recognizing at a glance

memoirs of Metternich herself (1922), and that a master-hand had been at work.”

of Worth’s son, Jean-Philippe (1928). (Metternich, 1922)

Born in 1825, Charles Frederick Worth Eugenie’s admiration of the dress led to

began his career at a London drapery house. her own commissions from Worth and

Moving to Paris in 1846, he found employ at Bobergh, catapulting Charles Frederick

Gagelin-Opigez & Cie, a retailer of fabrics Worth to success as other ladies of the court

and accessories, and a dressmaker. While in patronized the business.

their employ, Worth probably began design- This well-known story of Worth’s meteoric

ing in the dressmaking department. Worth rise to stardom has recently provoked doubt.

married a Gagelin-Opigez employee, Marie Worth scholar Sara Hume questions this

Vernet, a model at the store. Leaving in account on the basis that it is derived from

1857, Worth began his own business in part- loving, but unreliable secondary accounts.

nership with Otto Gustave Bobergh, with “The legend that has grown up around his

“Worth et Bobergh” on the label, and Mme name was built up in large part by memoirs

Marie Worth working at the business. by his son and famous clients written well

Records indicate that Worth and Bobergh after his death. After Worth had achieved

was an emporium, much in the model of fame, his clients such as the Princess

Gagelin-Opigez, and sold fabrics, and a Metternich, nostalgically wrote of his

variety of shawls and outerwear, with ready prominence under the Second Empire”.

made garments as well as made-to-measure (2003, p.80)

couture (Hume, 2003, p.7). Hume also questions that the custom of

Eugénie de Montijo, the Spanish-born wife Eugenie and Princess Metternich came as

of Emperor Napoleon III, was the most early in the decade as 1860, or that he held

important female style setter of Europe dur- a place of significant importance in the

ing the years of the Second Empire and is French fashion system prior to mid-decade.

associated with many fashions of the time. She notes that he did not receive mention in

She encouraged glamour at the French French fashion magazines until 1863, and

court that contrasted with the reserve of press coverage for the remainder of the

Queen Victoria’s Court of Saint James. decade was not plentiful. In addition, Worth

According to some accounts, Worth began and Bobergh did not use the designation

his association with Princess Metternich, “Breveté de S. M. l’Impératrice” until 1865.

the wife of the Austrian Ambassador to Moreover, the number of existing Worth

and Bobergh pieces in museum collections John Redfern of Cowes

from this time is less than what such success

would indicate (Hume, 2003). Across the English Channel, in the resort

Worth’s status during these years has been town of Cowes on the Isle of Wight, the

inflated retrospectively, and many other young John Redfern was transforming his

dressmaking establishments were successful drapery house into dressmaking business.

at the time. In these years, several were well John Redfern began his drapery business

established. Mlle Palmyre, Mme Vignon, during the 1850s. Although his business

Mme Laferrière, and Mme Roger, all developed slower than Worth’s, he eventu-

contributed to the trousseau or wardrobe ally acquired a no less auspicious clientele,

of Empress Eugenie, as did Maison Felix, including Queen Victoria, Alexandra

and it was at this time that La Chambre syn- Princess of Wales, and Lillie Langtry.

dicale de la Couture parisienne began. Also Growing over the course of the decade, the

emerging in these years, was the great cou- business was established for dressmaking by

turier Emile Pingat, who came to rival the late 1860s, and its subsequent steady

Worth’s importance in late 19th century growth rivaled the importance of The

French couture. House of Worth for 40 years.

“The frequent sobriquet of ‘inventor of In Cowes, Redfern was able to take advan-

haute couture’ gives the misleading impres- tage of the presence of Osborne House, one

sion that…Worth introduced a completely of Victoria’s official residences; “the whole

new method of designing and selling island benefited economically and socially

clothes. In fact haute couture evolved grad- from the need to supply the Household and

ually over the almost half century of the attending high society (North, 2008,

Worth’s career and represents only a seg- p 146).” His sons John and Stanley joined

ment of the new fashion industry which the business during the 1860s. The first

developed through the century”. (Hume recorded clothing from John Redfern was

2003, p.13) However erroneous the tradi- noted at the 1869 marriage of the daughter

tional accounts are, it is important to note of W.C. Hoffmeiter, Surgeon to HM the

Worth’s designs for Eugenie and the court Queen; Redfern provided the wedding dress

promoted French industry and had a favor- and the bridesmaids dresses (North, 2008,

able impact on the textile mills of Lyon. p.146). Certainly the aristocracy noticed the

Soon the house had an impressive client list, high-profile commission, and Redfern

including Queen Louise of Norway, understood the power of celebrity to pro-

Empress Elisabeth of Austria, along with mote his business in the coming years.

stage stars and glittering demimondaines of At this time a change in dress was under-

Paris. Although men would dominate the way: more sport and leisure activities were

fashion industry in a short time, a man in developing specific clothing, and those

the dressmaking business was still novel: women who could afford a diversified, spe-

Worth earned the moniker “man milliner,” cific wardrobe sought more practical attire;

and by transforming dressmaking from clothing for some activities showed the

women’s work to men’s work, the activity affect of the Dress Reform movement.

of designing fashions was taken more seri- Ensembles emerged, described in the fash-

ously as an applied art. ion press of the day as “walking costume,”

“seaside costume, and “promenade cos-

tume.” More practical outerwear for

women was being introduced, even “water-

proofs” (Taylor, 1999). At the same time, museum collections. From all over Europe

women’s equestrian clothes were crossing and North America, customers came to his

over into town clothes in the form of a “tai- house, willing to make the trip to Paris.

lor made” costume. For years men’s tailors Worth’s sons, Gaston and Jean-Philippe,

were producing women’s riding habits, with joined the business in these years. His repu-

jacket bodices made in masculine forms. As tation was now so noteworthy that Emile

men’s tailoring standards developed, Zola created a fictional version of Worth in

women’s riding clothes developed similarly, 1872. He excelled at the ornate draperies of

and woolen cloth associated with men’s the bustle period, and he reveled in inspira-

suiting began to cross over into the general tion from 18th Century modes, especially

female wardrobe (Taylor, 1999). British tai- popular in the 1870s with polonaise style

loring establishment Creed enjoyed the drapery in the manner of Marie

custom of both Queen Victoria and Antoinette’s “shepherdess style.”

Empress Eugenie for riding habits; opening However, Worth’s true creativity in these

a Paris store in 1850, The House of Creed years (and in general) has been questioned,

contributed significantly to this trend. As and his Hume reputation viewed as

tailor made ensembles emerged, lighter inflated: “Monographs of celebrated fashion

weight versions developed for summer designers, such as Worth, typically focus on

activities outdoors. individual genius as a primary force in initi-

John Redfern continued with success into ating new fashions. As an individual

the coming years as a very fine ladies dress- designer, Worth may not have been the cre-

maker. However, both of these trends – ative genius that his reputation may

sport clothing and the tailor made – figured suggest. The traditional view that Worth

prominently in Redfern’s career as the 1870s was a great innovator may be brought into

began and his business expanded. While question by a comparison between fashion

neither activewear nor the tailor made were plates and his designs”. (Hume, p.3)

necessarily his “invention,” Redfern would In light of such opinion, it is possible to sug-

do more to promote these styles than any gest that his true gift lay not in creating but

other designer. interpreting trends – already present in such

fashion plates – to suit the tastes of his rari-

Worth After Bobergh fied clientele. It is in these years that Worth

developed his system of mix and match

Worth and Bobergh closed during the components of a gown (Coleman, 1989). A

Franco Prussian War. Bobergh retired, and series prototypes of different sleeves, differ-

Worth reopened as Maison Worth. The ent bodices, different skits were available to

Third Republic left Worth without an be put together in different combinations

empress to showcase his work, but other and different fabrics to create a toilette,

European royals continued to give him maintaining for the client the impression of

business. However the backbone of his an original creation.

financial success now came from the wives By 1878, a new silhouette was developing.

and daughters of American nouveau riche The understructure that enhanced the but-

tycoons, who sought the overt prestige of a tocks went away, and a sleek silhouette

Worth wardrobe over the work of their local emerged, and princess line construction was

dressmakers. His popularity with the essential to it. Worth was important to the

American wealthy is attested to by the large popularity of this silhouette. Though he is

amount of Worth dresses in American often credited with inventing the princess

line (and supposedly naming if for return of the bustle in 1883, suited Worth’s

Alexandra the Princess of Wales) vertical aesthetic perfectly. Extant examples of his

seamed dresses went back to the middle work in museums from this time indicate a

ages. In the late 1850s and1860s, loose synchronicity of the prevailing modes of the

dresses with such vertical seams were worn day with his taste for flamboyant theatrical-

in the as walking costumes, intended for ity – the “man milliner” cum artiste at his

some measure of physical activity. In its finest.

application to this new silhouette, this new Although Worth was now at the top of Paris

style en princesse used the princess line fashion, many elite and moneyed customers

seams in a smooth, fitted to the body sought other designers. Emile Pingat’s

method, and the term was used to describe smaller business attracted the discerning

both dresses (in one piece from the shoulder who appreciated the quiet elegance of his

to the floor) and with bodices with similar work over Worth’s less subtle output

construction. A correlation between (Coleman, p.177). Also in these years,

princess line construction and the increased Doucet, a decades old emporium of shirts

presence of women’s tailor made garments and accessories, launched a couture division

has been made (Taylor, 1999): Charles headed by third generation Jacques Doucet,

Frederick Worth, in developing and popu- and soon rivaled Worth’s importance.

larizing the en princesse style was applying

principles of tailored construction to dress- Redfern and Sons

making, cannily on top of developments in

women’s fashions. As the Third Republic left France (and the

Not only did Charles Frederick Worth fashionable world) without an empress to

develop the couture system, he may have be a fashion icon, more attention focused on

truly invented the mystique of the fashion Britain’s royals. Alexandra of Denmark

designer as idiosyncratic, exalted artist. became the Princess of Wales upon her mar-

Worth needed a personality to suit his fabu- riage to Prince Edward in 1863. Although

lous clientele – especially to appeal to the she was quickly celebrated for her style, her

nouveau riche Americans – and the “man ensuing six pregnancies kept her out of the

milliner” affected the role of great artist. He spotlight until she re-emerged in 1871 (well

created an outrageous persona, wearing timed to coincide with Eugenie’s absence.)

dressing gowns (sometimes trimmed with Alexandra’s style helped define fashion in

fur or even tulle) and a floppy black velvet the next four decades. Also of importance

beret. “Such attire satisfied the illusion of a as a fashion icon was the Prince of Wales’

creative genius at work (Coleman, p.25). mistress, Emily LeBreton Langtry. “Lillie”

“Hollander in Seeing Through Clothes draws Langtry was the most noted of the

a correlation between Worth’s affected look, “Professional Beauties,” society women cel-

and images of Richard Wagner, and ebrated in the media simply for their looks,

Rembrandt (1993): such romanticized and she was, likely, the first celebrity prod-

deshabille was a calculated move, and such uct spokes model. Lillie’s hourglass

affection may have been borne of a desire to proportions strongly contrasted the lithe

mask a lack of genuine creativity with the Alexandra, but both women were widely

image of a great artist. The 1880s saw celebrated for their beauty, and important to

remarkable output from the house; the pop- the style of each were the fashions of John

ular garish colors, the continuation of overt Redfern.

historic inspirations, and the extremes of the By the early 1870s, fabrics from Redfern

were in the wardrobes of Queen Victoria aristocratic women, and the influence from

and Princess Alexandra, and their custom equestrian wear to the tailor made contin-

was included in Redfern’s advertising. More ued. An avid horsewoman, Elizabeth of

significant was the yachting boom that Austria set styles throughout Europe with

came to Cowes with the Prince and Princess her riding habits; a favorite detail was mili-

of Wales’ enthusiasm for the sport. British tary inspired frogs and braid in the style of

Aristocrats, American nouveau riche, and the Austro-Hungarian military. This style

other international elite were drawn to and other military inspiration quickly

Cowes for the developing regatta, and par- found their way into women’s tailored cos-

ticipated in other outdoor activities. The tume, including Redfern’s.

yachting, the wealthy clientele, and the With royal patronage and coverage in the

development of sport clothing combined to press, the business grew and expanded

place Redfern at the right place at the right internationally. A London branch was the

time. Redfern became the source for yacht- next to be established in 1878, where fash-

ing and seaside toilettes, and sailors’ ionable gowns were available along with

uniforms often served as design inspiration. sport and tailored clothes. Managing the

Redfern set the benchmark in this category London store was Frederick Mims, who

of clothing. Both the Princess and Mrs. took the name Redfern. In 1881 a Paris store

Langtry enjoyed sporting activities often opened that took its place in the French

wearing Redfern; as the widely imitated in fashion scene alongside Worth, Doucet, and

anything they wore, they set the styles for Pingat. Leading the Paris store was Charles

this type of clothing. Poynter, who also took the name Redfern.

Genteel activities such as croquet and Under Poynter Redfern’s supervision, other

archery were still enjoyed, but more vigor- stores opened in France, notably a store in

ous sports were becoming more popular. the resort town Deauville. By 1884, Redfern

These included hiking, golf, and shooting, and Sons had crossed the Atlantic, and

and often ankle length skirts (without the opened a store in New York City managed

fashionable bustles of the time) were worn. by Redfen’s son Ernest. While Lucile and

Tennis also grew in popularity, with special Paquin are both given credit for being the

tennis ensembles. Redfern designed jersey first transatlantic fashion business, Redfern

bodices and dresses for tennis (and other preceded both of them by more than 20

sports) and although Redfern was not the years. The Paris and New York stores

only house that featured jersey garments, it offered the same variety as the London

became associated with him. Both Mrs. store. Stores in Newport, Rhode Island, and

Langtry and the princess wore them, and Saratoga Springs, New York catered to the

they were documented in The Queen, the resort customer. While Redfern directly

leading British fashion periodical. Redfern challenged Worth at the Paris store, they

developed a strong relationship with the also appealed to a broader segment of the

publication, realizing that paid advertising market, making the business the more sig-

would lead to more editorial coverage nificant. While Maison Worth required its

(North). clientele to come to the Rue de la Paix,

Redfern continued to popularize the tailor Redfern and Sons, with branches in

made. The style was a favorite of Princess England, France, and the United States,

Alexandra who wore Redfern’s, attracted to brought its product to more of the fashion-

the combination of style and practicality. able world.

Riding continued to be a popular sport for

Maison Worth after Worth Redfern Ltd.

By the early 1890s Charles Frederick In 1892, the company incorporated as

Worth’s role in the house had declined, and Redfern Ltd. The death of John Redfern in

as both sons were now active in the com- 1895 had little affect on the continued suc-

pany, he essentially retired. Worth left the cess of the business; Redfern Ltd. had

management of the business in the hands of transformed “from the most successful

Gaston, who had already assumed much ladies tailoring business to an international

managerial responsibility. The creative side couture enterprise equal of Worth” (North,

was left to Jean-Philippe. The exact chain of 2009). Charles Poynter Redfern at the helm

events is unclear, as is also the extent of of the Paris store, was the most important

Worth senior’s continued role in the house; designer in the company and was equal

many Worth dresses from 1889-1895 are of Jean-Philippe Worth, Jacques Doucet,

unclearly attributed as whether father of son and Jeanne Paquin. Featuring designs by

designed them. “It is not possible to deter- Poynter Redfern, the company participated

mine at what point Jean-Philippe became in the Exhibition Universal of 1900. During

the lead designer for the house; however the 1900s, the focus of Redfern Ltd. was

garments after 1889 show differences… that more on couture, moving away from its

suggest a different designer” (Hume, 2003, activewear and tailored roots, although still

p.11). offering selections in those areas.

Nellie Melba, the noted Australian opera Underscoring that shift was the closure of

star, was a long time Worth customer; the original Cowes store. Royalty still went

Melba was particularly fond of Jean- to Redfern’s stores to be dressed, and Les

Philippe saying “Jean himself was a greater Modes joined The Queen in devoting a great

designer than his father had ever been” deal of editorial coverage to the house.

(Coleman, 1989, p.29). The output of the North asserts that Redfern Ltd. was the

house in the 1890s shows a remarkable syn- dominant force in Western fashion between

ergy between fashion and L’Art Nouveau the years of 1895 and the 1908 work of

and Japonisme styles developing in the other Paul Poiret (2009). It is possible to actually

applied arts. Like Redfern, Maison Worth

establish the pre-imminence of Redfern

also showed the affect of the Dress Reform

continued even further into the next decade

movement, however, that affect showed

to 1911. Although these are few years, they

itself in the form of ravishing, languid tea-

are pivotal to fashion history.

gowns along the rubric of Pre-Raphaelite

Many dress historians treat Poiret’s 1908

and Aesthetic taste. These were “artistic”

work as a watershed moment that capti-

costume for the artistic aristocratic lady, and

vated the fashionable world. One noted

did not show the practical affect that had

fashion historian (Deslandres, Poiret,

manifested itself at Redfern.

Rizzoli, p.96.) wrote “[as] if women had just

The decade of the 1900s saw the house of

Worth maintain continued success with been waiting for it, the Directoire line,

beautiful gowns, but other designers over- revived by Poiret, redefined elegance

shadowed its innovations and styles. Gaston overnight.” In light of the fact that Poynter

Worth’s attempt to enliven the house with a Redfern and Paquin were already doing this

young man named Paul Poiret proved short line, the extreme nature of such a pro-

lived and unsuccessful. The client base had nouncement can be easily called into

grown old, and now the aging house was question. Further, the fashion press paid

dressing aging women. virtually no attention to Poiret until a few

years later, making such an “overnight” these years, with their ersatz Near-Eastern

impact on fashion impossible. Redfern’s themes were sensationalist and hype pro-

output was well documented in the pages of voking, such as his “Minaret” dress and robe

The Queen and Les Modes. Poynter Redfern sultane; while much less elegant that his ele-

advocated soft styles, taking inspiration gant languid Directoire looks of 1908, they

from the 1780s and 1790s. He featured grabbed more publicity. The New York Times

“Romney Frocks” of white mousseline in the began including Poiret in its fashion cover-

manner of Marie Antoinette’s chemise à la age in 1910, and the rest of the fashion press

reine, and Empire waist à la Grecque styles followed, so that during the next three years

of Directoire inspiration – all beginning a he dominated the fashion media and was

few years before Poiret’s 1908 collection prominently featured in the pages of

(North, 2009). The commonly held, but Harper’s Bazaar, Femina, and The Queen.

retrospective, opinion that this was Poiret’s Poiret was one of the participating designers

“New Look” in terms of impact on wide- in the exciting new fashion journal, La

spread fashion and taste is simply not Gazette du Bon Ton. In addition to other

supportable in this light. houses, the roster also included Worth and

On 3 October 1909, The New York Times ran Redfern. The freshness of La Gazette du

a full-page article on Paris fashions, cover- Bon Ton’s style brought life to the two

ing the looks for Autumn and Winter 1910. houses, and their designs as represented in

The article celebrates Orientalist styles for Les Modes were still stylish. Redfern’s rele-

the season, that included Byzantine and vance outlasted Worth’s by a decade, but by

Egyptian inspiration, but most importantly now both houses were starting to decline

Russian styles. Although many designers and the glory days of each house had past.

are mentioned, Poynter Redfern is given the The affect on the aristocratic lifestyle caused

most significance, and the New York Times by World War I impacted both houses fur-

asserts that the Russian style was his cre- ther, yet each carried on for several more

ation: “Redfern is a master at these Russian years.

effects, which he is using very much this Also emerging in this decade was the busi-

season for street costumes. He has just ness of Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel. Starting

returned from Russia whither he goes in millinery, Chanel expanded into sports

almost every summer.” Maisons Worth, clothes and couture during the course of the

Doucet, and Paquin are all mentioned decade. A few aspects of her development

along with other houses, but Poiret is not and story are worth considering. Her early

mentioned at all. affair with the English-educated horse

breeder Etienne Balsam exposed her to an

The 1910s and Beyond equestrian set that certainly wore English

riding apparel and sport clothes, likely from

Paul Poiret became ascendant to Paris fash- Creed, Burberry and Redfern among others.

ion, finally by around 1911. His knack for This certainly contributed to her very lean

publicity lead to elaborate Arabian theme and tailored aesthetic that stood in sharp

parties, and the press was hungry for the contrast with Poiret’s opulence. But of even

exotic in the few years prior to the war. more importance was Chanel’s choice of

Perhaps with Charles Frederick Worth as Deauville as the location of her fist sports-

his role model, Poiret postured himself as wear boutique. Redfern Ltd had a Deauville

the eccentric artist, and put forth his cre- store for sometime, selling the company’s

ations as great works of art. His designs of signature sports clothes; the young Chanel

would have unquestionably been familiar sportswear and activewear of the 20th

with Redfern’s product and sport clothes Century, and the gradually growing casual

business model. An examination of Redfern aesthetic. The Redfern aesthetic could be

designs from the decade underscores the tied to such influential fashion design

similarity to the Chanel aesthetic. A tailor minds as Claire McCardell, Vera Maxwell,

made costume from Redfern illustrated in Calvin Klein, or Norma Kamali, whose

La Gazette du Bon Ton from 1914, and a work was not typified by runway spectacle

sport ensemble from in the collection of the but rather by real clothes.

Kyoto Costume Institute, dated c. 1915,

both show a marked similarity to Chanel Daniel James Cole

designs that came a short time later. Many Professor, FIT New York

of Chanel signature styles, while strongly

associated with her today, were actually pio- Special Thanks

neered long before by Redfern, including, Karen Cannell, Fashion Institute of Technology

Nancy Deihl, New York University

most notably, the use of jersey for sports-

Susan North, Victoria and Albert Museum

wear.

As for Worth, he left a legacy into the 20th

century was of lavish couture gowns and Bibliography

ensembles that have always been a major Arnold, Janet: “Dashing Amazons: The Development

of Women’s Riding Dress,” Define Dress: Dress as

feature of the French fashion industry. Object, Meaning, and Identity, ed. De la Haye, Amy and

Edward Molyneux earned the nickname Wilson, Elizabeth, University of Manchester Press,

“the New Worth,” as an Englishman who Manchester, 1999.

conquered Paris, and he showed great Barwick, Sandra: A Century of Style, George, Allen,

and Unwin, London, 1984.

prowess for frosting his sleek elegant flapper Batterberry, Michael & Batterberry, Ariane: Fashion The

dresses with glitter. Perhaps his most signif- Mirror of History, Holt, Rhinehart & Winston, Boston,

icant contribution to the fashion industry of 1979.

the 20th Century was his invention of the Boucher, François & Deslandres, Yvonne: Twenty

Thousand Years of Fashion, Abrams, New York, 1987.

persona of fashion designer as flamboyant Blum, Stella: Victorian Fashions and Costumes from

great artist; and the persona took on even Harper’s Bazaar, 1867-1898, Dover Books, New York,

more outrageous form in some of his suc- 1979.

cessors. This can be exemplified in recent Calloway, Stephen & Jones, Stephen: Royal Style: Five

Centuries of Influence and Fashion, Little Brown and

years with the personalities and manner of Company, Boston, 1991.

Karl Lagerfeld, Jean Paul Gaultier, Cole, Daniel James and Deihl, Nancy: Fashion Since

Alexander McQueen, and John Galliano, 1850, Laurence King Ltd., London, 2012.

among others. Coleman, Ann: The Opulent Era: Fashions of Worth,

Doucet, and Pingat, New York, Brooklyn Museum,

The legacy of John Redfern may actually 1989.

define clothing in the 20th Century. The Cunnington, C.Willet: English Women’s Clothing in the

intellectual lineage of Redfern is monumen- Nineteenth Century, Farber and Farber, London, 1937.

tal and exemplary of the entire history of Cunnington, Phillis Emily: English Costume for Sports

and Outdoor Recreation, Barnes and Noble, New York,

20th century clothing: John Redfern men- 1970.

tored Charles Poynter Redfern, who in turn DeLaHaye, Amy & Tobin, Shelley: Chanel, The

mentored Robert Piguet, who mentored Couturiere at Work, The Overlook Press, Woodstock,

1996.

Christian Dior, who lead the line to Yves

DeMarty, Diane: Worth, the Father of Modern Couture,

Saint Laurent. Redfern (and his companies) New York, Holmes and Meier, 1990.

focus on the emerging market of sports Deslandres, Yvonne: Poiret, Rizzoli, New York, 1987.

clothes lead the way to the categories of Fukai, Akiko, et. al.: The Collection of the Kyoto

Costume Institute: Fashion - A History from the 18th to Tortora, Phyllis & Eubank, Kenneth: Survey of Historic

20 the Century, Taschen, Köln, 2002. Costume, Fairchild, 2005.

Ginsburg, Madeleine; Hart, Avril; Mendes, Valerie & Troy, Nancy: Couture Culture: A Study in Modern Art

Rothstein, Natalie: Four Hundred Years of Fashion, and Fashion, Cambridge, MIT Press, 2004.

Victoria & Albert Museum, London, 1993. Worth, Gaston: La Couture et la Confection des vête-

Goldthorpe, Caroline: From Queen to Empress: ments de femme, Paris, Chaix, 1895.

Victorian Dress 1837-1870, Metropolitan Museum of Worth, Jean-Philippe: A Century of Fashion, translated

Art/Abrams, New York, 1989. by Ruth Scott Miller, Boston, Little Brown and Co,

Hollander, Anne: Seeing Through Clothes, Berkeley, 1928.

University of California Press, 1993.

Hollander, Anne: “When Mr. Worth was King,” Periodicals:

Connoisseur, December 1982, 114-120. L’Art de la Mode (aka L’Art et la Mode)

Hume, Sara Elisabeth: Charles Frederick Worth: A Harper’s Bazaar

Study in the Relationship the Parisian Fashion Industry Les Modes

and the Lyonnais Silk Industry 1858-1889 (MA Thesis), La Mode Illustrée

SUNY Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, The Queen

2003.

Kjellberg, Anne & North, Susan: Style & Splendor: The

Wardrobe of Queen Maude of Norway, Victoria & Albert

Museum, London, 2005.

Lambert, Miles: Fashion in Photographs 1860-1880, B.T.

Batsford, London, 1991.

Laver, James: A Concise History of Costume and Fashion,

Thames and Hudson, New York 1988.

Lees, Frederick: “The Evolution of Paris Fashions: An

Enquiry,” Pall Mall Magazine, 1903, 113-122.

Millbank, Caroline Rennolds: Couture: The Great

Designers, Stewart, Tabori, and Chang, New York,

1985.

Metternich-Winnenberg, Pauline Von: My Years in

Paris, London, Nash, 1922.

North, Susan: “John Redfern and Sons, 1847 to 1892,”

Costume, vol. 42, 2008.

North, Susan: “Redfern Ltd. & Sons, 1892 to 1940,”

Costume, vol. 43, 2009.

Payne, Blanche: History of Costume from the Ancient

Egyptians to the Twentieth Century, Harper and Row,

New York, 1965.

Perrot, Philippe: Fashion the Bourgeois: A History of

Clothing in the 19th Century, Princeton University

Press, Princeton, 1996.

Poiret, Paul: King of Fashion, translated by Stephen

Haiden Guest, J. B. Lippincott, Philadelphia/London,

1931.

Reeder, Jan Glier: The Touch of Paquin: 1891-1920 (MA

Thesis), SUNY Fashion Institute of Technology, New

York, 1990.

Ribeiro, Aileen: “Fashion in the Work of Winterhalter,”

Franz Xaver Winterhalter and the Courts of Europe, ed.

Ormond, Richard and Blackett-Ord, Carol. National

Portrait Gallery, London/Harry Abrams, New York,

1992.

Steele, Valerie: Paris Fashion: A Cultural History,

Oxford University Press, New York/Oxford, 1988.

Taylor, Lou: “Wool Cloth, Gender, and Women’s

Dress,” Define Dress: Dress as Object, Meaning, and

Identity, ed. De la Haye, Amy and Wilson, Elizabeth,

University of Manchester Press, Manchester, 1999.

You might also like

- Atestat Engleza - FashionDocument18 pagesAtestat Engleza - FashionMariaNo ratings yet

- Costumes in Romeo and Juliet - 3Document16 pagesCostumes in Romeo and Juliet - 3for.peterbtopenworld.comNo ratings yet

- Charles Frederick WorthDocument1 pageCharles Frederick WorthАмина ДемешеваNo ratings yet

- Charles Frederick WorthDocument4 pagesCharles Frederick WorthPriyanka BoseNo ratings yet

- Early Career: Historic PortraitsDocument6 pagesEarly Career: Historic PortraitsTóth IldiNo ratings yet

- The Court-Balls of Marie AntoinetteDocument8 pagesThe Court-Balls of Marie Antoinettedanielson3336888No ratings yet

- History of FashionDocument306 pagesHistory of FashionyaqshanNo ratings yet

- 'I'Mimlijmmmli M MK AmuDocument234 pages'I'Mimlijmmmli M MK AmuMarian MorganNo ratings yet

- French and English furniture distinctive styles and periods described and illustratedFrom EverandFrench and English furniture distinctive styles and periods described and illustratedNo ratings yet

- Week 1Document54 pagesWeek 1YINGGCHI LONGNo ratings yet

- French and English furniture distinctive styles and periods: Illustrated EditionFrom EverandFrench and English furniture distinctive styles and periods: Illustrated EditionNo ratings yet

- Victorian and Edwardian Fashions from "La Mode Illustrée"From EverandVictorian and Edwardian Fashions from "La Mode Illustrée"Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- GC-203 Assignment RISHABHDocument24 pagesGC-203 Assignment RISHABHKaushik GuptaNo ratings yet

- Authentic French Fashions of the Twenties: 413 Costume Designs from "L'Art Et La Mode"From EverandAuthentic French Fashions of the Twenties: 413 Costume Designs from "L'Art Et La Mode"Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Rose Bertin, The Creator of Fashion at The Court of Marie-Antoinette 1913Document380 pagesRose Bertin, The Creator of Fashion at The Court of Marie-Antoinette 1913Kassandra M Journalist100% (3)

- Modern Bookbindings Their Design Decoration PDFDocument214 pagesModern Bookbindings Their Design Decoration PDFpamela4122No ratings yet

- Paris The Capital of FashionDocument181 pagesParis The Capital of Fashionjenniferkhole0033No ratings yet

- Vathekarabiantal00beck PDFDocument148 pagesVathekarabiantal00beck PDFSalomon SachsNo ratings yet

- Louis XIV's Architect: Louis Le Vau, France's Most Important BuilderFrom EverandLouis XIV's Architect: Louis Le Vau, France's Most Important BuilderNo ratings yet

- A Concise History of French Painting (Edward Lucie-Smith)Document296 pagesA Concise History of French Painting (Edward Lucie-Smith)Pushpita GhoseNo ratings yet

- Gautier Chivalry PDFDocument518 pagesGautier Chivalry PDFΔημητρης ΙατριδηςNo ratings yet

- Seeing Europe with Famous Authors, Volume 4 France and the Netherlands, Part 2From EverandSeeing Europe with Famous Authors, Volume 4 France and the Netherlands, Part 2No ratings yet

- Victorian Fashions and Costumes from Harper's Bazar, 1867-1898From EverandVictorian Fashions and Costumes from Harper's Bazar, 1867-1898Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Family of DariusDocument5 pagesThe Family of DariusaustinNo ratings yet

- 2014 - Spring - 4 - Barringer SarahDocument5 pages2014 - Spring - 4 - Barringer SarahcesiahdezNo ratings yet

- Fashion History FybaDocument31 pagesFashion History FybaHenishaNo ratings yet

- Exercise 7: Match The Pairs of Sentences From The Columns and Combine Them With TheDocument6 pagesExercise 7: Match The Pairs of Sentences From The Columns and Combine Them With TheАлександраNo ratings yet

- Queen Elizabeth II: A Lifetime Dressing for the World StageFrom EverandQueen Elizabeth II: A Lifetime Dressing for the World StageRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Rise of French Monarchical Power Dominated by Louis XivDocument39 pagesThe Rise of French Monarchical Power Dominated by Louis XivRajesh Kumar RamanNo ratings yet

- The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 14, No. 384, August 8, 1829From EverandThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 14, No. 384, August 8, 1829No ratings yet

- CRINOLINE 1840-1865 (The French Word For Horsehair) The Age of Optimism The Industrial RevolutionDocument113 pagesCRINOLINE 1840-1865 (The French Word For Horsehair) The Age of Optimism The Industrial Revolutiontairos555No ratings yet

- Van Dyck A Collection Of Fifteen Pictures And A Portrait Of The Painter With Introduction And InterpretationFrom EverandVan Dyck A Collection Of Fifteen Pictures And A Portrait Of The Painter With Introduction And InterpretationNo ratings yet

- Herbert Norris - Medieval Costume and FashionDocument564 pagesHerbert Norris - Medieval Costume and FashionOvidiu100% (3)

- The History of the Caliph VathekDocument447 pagesThe History of the Caliph VathekKanad Prajna DasNo ratings yet

- Rosalba CarrieraDocument5 pagesRosalba CarrieraGeorgiaNo ratings yet

- The Story of Versailles by Payne, Francis LoringDocument67 pagesThe Story of Versailles by Payne, Francis LoringGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- New Welsh Reader: A Casual Archaeology: New Welsh Reader 129 (New Welsh Review Summer 2022)From EverandNew Welsh Reader: A Casual Archaeology: New Welsh Reader 129 (New Welsh Review Summer 2022)No ratings yet

- 1900 Fashion HistoryDocument37 pages1900 Fashion HistoryRanjan NishanthaNo ratings yet

- Jessie Raven Crosland - Medieval French Literature-Blackwell (1956)Document276 pagesJessie Raven Crosland - Medieval French Literature-Blackwell (1956)Fulvidor Galté OñateNo ratings yet

- Rose Bertin - WikipediaDocument5 pagesRose Bertin - WikipediaBrayan Anderson Chumpen CarranzaNo ratings yet

- Architectural Record Magazine AR 1905 12 CompressedDocument86 pagesArchitectural Record Magazine AR 1905 12 CompressedMarco MilazzoNo ratings yet

- Illuminated illustrations of Froissart; Selected from the ms. in the British museumFrom EverandIlluminated illustrations of Froissart; Selected from the ms. in the British museumNo ratings yet

- Dutch and Flemish FurnitureDocument490 pagesDutch and Flemish Furniturebr657493080No ratings yet

- Verdi: Man and Musician: His Biography with Especial Reference to His English ExperiencesFrom EverandVerdi: Man and Musician: His Biography with Especial Reference to His English ExperiencesNo ratings yet

- Fashion HistoryDocument40 pagesFashion HistoryAo OkamiNo ratings yet

- No Recipe Old Recipe PSC v01 20230812 T203926Document36 pagesNo Recipe Old Recipe PSC v01 20230812 T203926ShovonNo ratings yet

- Lacoste Reebok ComparatieDocument27 pagesLacoste Reebok Comparatiedrinky381No ratings yet

- CrystalshapesDocument7 pagesCrystalshapesapi-276687098No ratings yet

- Clothes Test 4. RocDocument1 pageClothes Test 4. Rocviki palikovaNo ratings yet

- Final Listening Test I2Document1 pageFinal Listening Test I2LUIS FERNANDO VICTORIA ROJASNo ratings yet

- Tasmanian Craft Fair Program 2017Document28 pagesTasmanian Craft Fair Program 2017The ExaminerNo ratings yet

- Rapture by Pat BravoDocument40 pagesRapture by Pat BravoArt Gallery FabricsNo ratings yet

- Met GalaDocument2 pagesMet GalaNico RomaniNo ratings yet

- Swiss ArabianDocument101 pagesSwiss ArabianKiran MoreNo ratings yet

- Science Fair 5 2Document12 pagesScience Fair 5 2api-230330590No ratings yet

- Camden Fashion: Video UK - Exercises: PreparationDocument2 pagesCamden Fashion: Video UK - Exercises: PreparationVeronika SrncováNo ratings yet

- Super Character Design Amp Amp Poses Vol 2 HeroiDocument123 pagesSuper Character Design Amp Amp Poses Vol 2 HeroiCésar Narvaez100% (6)

- Golic VulcanDocument12 pagesGolic VulcanmarkjujuNo ratings yet

- 30 Day Gratitude Journal - Isabelle MoonDocument16 pages30 Day Gratitude Journal - Isabelle MoonAlberto GarciaNo ratings yet

- The Significance of Your Graduation TogaDocument2 pagesThe Significance of Your Graduation TogaDominicSavioNo ratings yet

- PerfumesDocument10 pagesPerfumesMohamed ElaskalnyNo ratings yet

- Style YourselfDocument56 pagesStyle YourselfWeldon Owen Publishing100% (8)

- Medium Manufacturer-Jewellery 2020Document25 pagesMedium Manufacturer-Jewellery 2020piv.hpNo ratings yet

- What Are You Like? What's He Like? What's She Like?Document9 pagesWhat Are You Like? What's He Like? What's She Like?Adelaida Ruiz VelandiaNo ratings yet

- Majalah Dewasa Format PDF Weekly PlayboyDocument1 pageMajalah Dewasa Format PDF Weekly PlayboyEmmanuel Louise de Guzman100% (1)

- Art NouveauDocument40 pagesArt NouveauUtsav AnuragNo ratings yet

- Chapter..2 KinesicsDocument33 pagesChapter..2 Kinesicsservice1234No ratings yet

- Bennett, Cherie - Sunset Island 001 - Sunset IslandDocument75 pagesBennett, Cherie - Sunset Island 001 - Sunset IslandIngy Al KafrawyNo ratings yet

- HFT 2223 Socio-Cultural & Psychological Aspects in Fashion Assgn.Document50 pagesHFT 2223 Socio-Cultural & Psychological Aspects in Fashion Assgn.Carolyn Morang'aNo ratings yet

- The History of Fashion (PDFDrive)Document369 pagesThe History of Fashion (PDFDrive)dani gogoNo ratings yet

- Fashion Show Types & ChoregraphyDocument4 pagesFashion Show Types & ChoregraphyD Babu Kosmic100% (3)

- Handbook of Furniture StylesDocument182 pagesHandbook of Furniture Stylesproteor_srl100% (8)

- Personal-Grooming VikDocument24 pagesPersonal-Grooming Vikvik_pk12No ratings yet

- Clothes and Accessories Vocabulary Esl Multiple Choice Tests For KidsDocument4 pagesClothes and Accessories Vocabulary Esl Multiple Choice Tests For KidsIhsan OzoraNo ratings yet

- Wedding Details For Planners ChecklistDocument7 pagesWedding Details For Planners ChecklistLizette SyNo ratings yet