Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Week 3 GreerVirick 2008

Week 3 GreerVirick 2008

Uploaded by

杨子偏Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- CAPSIM ExamDocument46 pagesCAPSIM ExamGanesh Shankar90% (10)

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion - ReportDocument23 pagesDiversity, Equity & Inclusion - ReportComunicarSe-Archivo100% (1)

- Corus Steel Case StudyDocument13 pagesCorus Steel Case Studyahsan1379100% (2)

- Supply Chain in Dell PDFDocument11 pagesSupply Chain in Dell PDFTâm Dương100% (1)

- The Hay Group Engaged Performance ModelDocument4 pagesThe Hay Group Engaged Performance ModelSurya ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Reading 5Document19 pagesReading 5lythobindigo89No ratings yet

- Patterns of Resource Allocation and Divisional Budgets: The CEO's Strategic Lens Across Various IndustriesDocument11 pagesPatterns of Resource Allocation and Divisional Budgets: The CEO's Strategic Lens Across Various IndustriesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Organizational Strategic Plan PDFDocument5 pagesOrganizational Strategic Plan PDFchala meseretNo ratings yet

- Organizational Strategic Plan PDFDocument5 pagesOrganizational Strategic Plan PDFchala meseretNo ratings yet

- Session 6 Leadership in ContextDocument32 pagesSession 6 Leadership in ContextCsec helper1No ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 203.175.72.26 On Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTCDocument20 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 203.175.72.26 On Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTCShujat AliNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance:: The Moderating Role of Managerial PowerDocument14 pagesEntrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance:: The Moderating Role of Managerial PowerfareasNo ratings yet

- Succession PlanningDocument8 pagesSuccession PlanningMuktar Hossain ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Effects of Leadership in Human-3799Document5 pagesEffects of Leadership in Human-3799dorayNo ratings yet

- Balanced Score Card..., CRAIG, 2005Document18 pagesBalanced Score Card..., CRAIG, 2005Joaquin Rodrigo Yrivarren EspinozaNo ratings yet

- Implementing A Strategic Vision-Key Factors For SuccessDocument14 pagesImplementing A Strategic Vision-Key Factors For SuccessStephanie ShekNo ratings yet

- Slack Resources and The Performance of Privately Held Firms: Gerard George University of Wisconsin-MadisonDocument17 pagesSlack Resources and The Performance of Privately Held Firms: Gerard George University of Wisconsin-MadisonWesley S. LourençoNo ratings yet

- Building A Capable Organization: The Eight Levers of Strategy ImplementationDocument13 pagesBuilding A Capable Organization: The Eight Levers of Strategy ImplementationAbhishek JurianiNo ratings yet

- Game Changing Talent StrategyDocument8 pagesGame Changing Talent StrategyLuis D. AlmarazNo ratings yet

- J Ijpe 2006 07 011Document16 pagesJ Ijpe 2006 07 011Mtra Isabel MedelNo ratings yet

- Cite Seer XDocument15 pagesCite Seer XRajat SharmaNo ratings yet

- Implementing Strategically Aligned Performance Measurement in Small FirmsDocument3 pagesImplementing Strategically Aligned Performance Measurement in Small FirmsMtra Isabel MedelNo ratings yet

- The Ambidextrous OrganizationDocument10 pagesThe Ambidextrous OrganizationKewin KusterNo ratings yet

- Paradoxical Leadership (2014)Document21 pagesParadoxical Leadership (2014)NazarethNo ratings yet

- Paradoxical Thinking PDFDocument20 pagesParadoxical Thinking PDFRoberto LoreNo ratings yet

- Nadkarni & Herrmann, 2010Document25 pagesNadkarni & Herrmann, 2010Harshad Vinay SavantNo ratings yet

- Making Disney Pixar Into A Learning OrganizationDocument20 pagesMaking Disney Pixar Into A Learning OrganizationAatif_Saif_80No ratings yet

- Assignment - Dow Corning - Tran Duc AnhDocument6 pagesAssignment - Dow Corning - Tran Duc AnhDucanh TranNo ratings yet

- The Designed Relationship of A Business Unit and The Corporate Center: A Global Supply Chain Case StudyDocument19 pagesThe Designed Relationship of A Business Unit and The Corporate Center: A Global Supply Chain Case StudyaijbmNo ratings yet

- Leading Organizational Transformation: The View From The TopDocument4 pagesLeading Organizational Transformation: The View From The TopArslan AhmadNo ratings yet

- The Essence of Strategic Leadership: Managing Human and Social CapitalDocument14 pagesThe Essence of Strategic Leadership: Managing Human and Social CapitalFathan MubinaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Introduction To The Concept of Strategic EntrepreneurshipDocument16 pagesChapter 1 Introduction To The Concept of Strategic Entrepreneurshiprbtbvczqh9No ratings yet

- 6488 94592 1 PBDocument13 pages6488 94592 1 PBsilmiNo ratings yet

- Strategic Entrepreneurship: Topic 1Document17 pagesStrategic Entrepreneurship: Topic 1Nurul Wahida Binti Safiyudin C19A0696No ratings yet

- Succession ManagementDocument12 pagesSuccession ManagementeurofighterNo ratings yet

- WRAP Global Talent Management Performance Multinational Mellahi 2019Document54 pagesWRAP Global Talent Management Performance Multinational Mellahi 2019zahrafatimah2603No ratings yet

- The Academy of Management Journal: This Content Downloaded From 149.200.255.110 On Sat, 06 Nov 2021 22:31:59 UTCDocument32 pagesThe Academy of Management Journal: This Content Downloaded From 149.200.255.110 On Sat, 06 Nov 2021 22:31:59 UTCinfoomall.psNo ratings yet

- Effect of Transformational and Transactional Leadership On Innovation Performance Among Small and Medium Enterprise in Uasin Gishu County, KenyaDocument14 pagesEffect of Transformational and Transactional Leadership On Innovation Performance Among Small and Medium Enterprise in Uasin Gishu County, KenyaMalcolm ChristopherNo ratings yet

- Applying Strategic Manag at EEOCDocument7 pagesApplying Strategic Manag at EEOCAna GsNo ratings yet

- CLASS: Five Elements of Corporate Governance To Manage Strategic RiskDocument13 pagesCLASS: Five Elements of Corporate Governance To Manage Strategic RiskPɑolɑ VillɑcisNo ratings yet

- O'Regan, N. C.S. PaperDocument35 pagesO'Regan, N. C.S. PaperAli HaddadouNo ratings yet

- Building A Capable Organization: The Eight Levers of Strategy ImplementationDocument9 pagesBuilding A Capable Organization: The Eight Levers of Strategy ImplementationMukund KabraNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 195.43.22.135 On Wed, 10 Feb 2021 04:40:13 UTCDocument5 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 195.43.22.135 On Wed, 10 Feb 2021 04:40:13 UTCSamah AyadNo ratings yet

- Mergers 101 Part 2 TrainingmanagersforculturestressandchangechallengesDocument11 pagesMergers 101 Part 2 TrainingmanagersforculturestressandchangechallengesErold BautistaNo ratings yet

- Ocasio, W. & Kim, H. (1999) - The Circulation of Corporate Control - Selection of Functional Backgrounds of New CEOs in LargeDocument32 pagesOcasio, W. & Kim, H. (1999) - The Circulation of Corporate Control - Selection of Functional Backgrounds of New CEOs in LargeVanitsa DroguettNo ratings yet

- What Factors Affect The Business Success of Philippine SMEs in The Food Sector - Borazon 2015 PDFDocument6 pagesWhat Factors Affect The Business Success of Philippine SMEs in The Food Sector - Borazon 2015 PDFLuke ThomasNo ratings yet

- Guest Editors' Note: The Role of HR Practices in Managing Culture Clash During The Postmerger Integration ProcessDocument6 pagesGuest Editors' Note: The Role of HR Practices in Managing Culture Clash During The Postmerger Integration ProcessengasmaaNo ratings yet

- Current Trends in SPMDocument4 pagesCurrent Trends in SPMMasthan AliNo ratings yet

- U 01 LP Blackman & Kennedy - Talent Management Developing or Preventing Knowledge and Capability - IRPSM - 2008Document10 pagesU 01 LP Blackman & Kennedy - Talent Management Developing or Preventing Knowledge and Capability - IRPSM - 2008Paloma Martinez HagueNo ratings yet

- Succession PlanningDocument4 pagesSuccession PlanningRabeeaManzoorNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Star ReadingsDocument11 pagesKnowledge Star ReadingsKareena ShahNo ratings yet

- Sciencedirect: The Role of Leadership in Implementing Lean ManufacturingDocument6 pagesSciencedirect: The Role of Leadership in Implementing Lean ManufacturingEspara TNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Introduction To The Concept of Strategic EntrepreneurshipDocument16 pagesChapter 1 Introduction To The Concept of Strategic EntrepreneurshipatikahNo ratings yet

- The Leadership Quarterly: Abraham Carmeli, Roy Gelbard, David GefenDocument11 pagesThe Leadership Quarterly: Abraham Carmeli, Roy Gelbard, David GefenSarah HadNo ratings yet

- Strategicentrepreneurshipt1 141207213422 Conversion Gate01Document16 pagesStrategicentrepreneurshipt1 141207213422 Conversion Gate01Sumit KohliNo ratings yet

- Strategy Formulation Processes Differences in Perceptions of Strength and Weaknesses Indicators and Environmental Uncertainty by Managerial LevelDocument18 pagesStrategy Formulation Processes Differences in Perceptions of Strength and Weaknesses Indicators and Environmental Uncertainty by Managerial LevelamaniNo ratings yet

- Succession PlanningDocument12 pagesSuccession PlanningUAS DinkelNo ratings yet

- Upadhaya 2018Document15 pagesUpadhaya 2018olanNo ratings yet

- Deloitte Uk GMT Roleof HR in Global MobilityDocument8 pagesDeloitte Uk GMT Roleof HR in Global Mobilityamit naithaniNo ratings yet

- Succession Planning and Management: A Guide to Organizational Systems and PracticesFrom EverandSuccession Planning and Management: A Guide to Organizational Systems and PracticesNo ratings yet

- A BUM's Strategic Planning And Critical Thinking ApproachFrom EverandA BUM's Strategic Planning And Critical Thinking ApproachNo ratings yet

- Legacy Leadership: The emergence of a new leadership model after more than a decade of crisisFrom EverandLegacy Leadership: The emergence of a new leadership model after more than a decade of crisisNo ratings yet

- Quota For Women I Management Dezs - Et - Al-2016-Strategic - Management - JournalDocument18 pagesQuota For Women I Management Dezs - Et - Al-2016-Strategic - Management - Journal杨子偏No ratings yet

- ACCT5432 - Example ISDocument1 pageACCT5432 - Example IS杨子偏No ratings yet

- Chapter 6, Page 186 Q12 SolutionDocument2 pagesChapter 6, Page 186 Q12 Solution杨子偏No ratings yet

- HRMT5504 Week11 Before ClassDocument14 pagesHRMT5504 Week11 Before Class杨子偏No ratings yet

- Hancock9e Testbank ch09Document18 pagesHancock9e Testbank ch09杨子偏No ratings yet

- ACCT5432 - Example BSDocument1 pageACCT5432 - Example BS杨子偏No ratings yet

- Yang - Group Presentation - FINAL VERSIONDocument2 pagesYang - Group Presentation - FINAL VERSION杨子偏No ratings yet

- ACCT5432-17 - S2 - Seminar Week 2Document19 pagesACCT5432-17 - S2 - Seminar Week 2杨子偏No ratings yet

- ACCT5432-17 - S2 - Seminar Week 1Document20 pagesACCT5432-17 - S2 - Seminar Week 1杨子偏No ratings yet

- HRMT5504 Week9 Before ClassDocument15 pagesHRMT5504 Week9 Before Class杨子偏No ratings yet

- Problem 2.9 SolutionDocument1 pageProblem 2.9 Solution杨子偏No ratings yet

- HRMT5504 Week3 Before ClassDocument21 pagesHRMT5504 Week3 Before Class杨子偏No ratings yet

- Problem 1.1 SolutionDocument1 pageProblem 1.1 Solution杨子偏No ratings yet

- HRMT5504 Week7 Before ClassDocument16 pagesHRMT5504 Week7 Before Class杨子偏No ratings yet

- HRMT5504 Week4 Before ClassDocument17 pagesHRMT5504 Week4 Before Class杨子偏No ratings yet

- Hancock9e Testbank ch08Document24 pagesHancock9e Testbank ch08杨子偏No ratings yet

- Chronology of Major Tailings Dam FailuresDocument16 pagesChronology of Major Tailings Dam Failures杨子偏No ratings yet

- HRMT5504 - Week2 - Before ClassDocument20 pagesHRMT5504 - Week2 - Before Class杨子偏No ratings yet

- HRMT5504 - Week5 Before ClassDocument16 pagesHRMT5504 - Week5 Before Class杨子偏No ratings yet

- W1 How To Suceed in This Unit v2Document27 pagesW1 How To Suceed in This Unit v2杨子偏No ratings yet

- Wk3 Eng QuizDocument3 pagesWk3 Eng Quiz杨子偏No ratings yet

- W1 Engineering A Safer World v2 StudentDocument16 pagesW1 Engineering A Safer World v2 Student杨子偏No ratings yet

- Wk10 Probability and Statistics Quiz-1Document6 pagesWk10 Probability and Statistics Quiz-1杨子偏No ratings yet

- Wk9 Probability and Statistics QuizDocument4 pagesWk9 Probability and Statistics Quiz杨子偏No ratings yet

- Wk11 Probability and Statistics Quiz-1Document8 pagesWk11 Probability and Statistics Quiz-1杨子偏No ratings yet

- Wk4 Probability and Statistics QuizDocument4 pagesWk4 Probability and Statistics Quiz杨子偏No ratings yet

- Week 1 Baseline QuizDocument9 pagesWeek 1 Baseline Quiz杨子偏No ratings yet

- Wk6 Probability and Statistics Quiz-1Document4 pagesWk6 Probability and Statistics Quiz-1杨子偏No ratings yet

- Wk6 Probability and Statistics QuizDocument4 pagesWk6 Probability and Statistics Quiz杨子偏No ratings yet

- Wk4 Probability and Statistics Quiz-1Document4 pagesWk4 Probability and Statistics Quiz-1杨子偏No ratings yet

- Supply Chain Drivers and ObstaclesDocument28 pagesSupply Chain Drivers and ObstaclesyogaknNo ratings yet

- Yet Another Scandal The Allied Irish Bank CaseDocument49 pagesYet Another Scandal The Allied Irish Bank CaseRicha KumariNo ratings yet

- IT Strategy Course SyllabusDocument5 pagesIT Strategy Course SyllabusJoyson LewisNo ratings yet

- Text Book - Chapter 2 - Operations Strategy in A Global EnvironmentDocument4 pagesText Book - Chapter 2 - Operations Strategy in A Global Environmentasmita dagadeNo ratings yet

- Delft Design Guide 2Document108 pagesDelft Design Guide 2saori_sasaki_san7936No ratings yet

- Basic Concepts of Strategic ManagementDocument48 pagesBasic Concepts of Strategic ManagementKashyap ShivamNo ratings yet

- ADEC - West Yas Private School 2016-2017Document18 pagesADEC - West Yas Private School 2016-2017Edarabia.comNo ratings yet

- Anjali Rakheja - Resume 2023Document3 pagesAnjali Rakheja - Resume 2023Krishnendra JainNo ratings yet

- Futures Algo EvolutionDocument15 pagesFutures Algo Evolutionsvejed123No ratings yet

- Toyota DissertationDocument5 pagesToyota DissertationWhereCanIFindSomeoneToWriteMyCollegePaperCanada100% (1)

- Costco Wholesale CorporationDocument12 pagesCostco Wholesale CorporationNazish Sohail100% (4)

- Lecture 3 (CHP 3) ModelsDocument45 pagesLecture 3 (CHP 3) ModelsRita RanveerNo ratings yet

- DCL 10-11. BrandDocument16 pagesDCL 10-11. BrandNargis Akter ToniNo ratings yet

- An Enterprise Approach To Data Quality: The ACT Health ExperienceDocument13 pagesAn Enterprise Approach To Data Quality: The ACT Health ExperienceArk GroupNo ratings yet

- GAP Analysis SiemensDocument14 pagesGAP Analysis Siemenssaadhassan555100% (1)

- Mahatma Gandhi University Mba SyllabusDocument188 pagesMahatma Gandhi University Mba SyllabusTony JacobNo ratings yet

- Ch08 Roth3eDocument86 pagesCh08 Roth3etaghavi1347No ratings yet

- Roles and Responsibilities of Central ManagementDocument13 pagesRoles and Responsibilities of Central ManagementManmohanNo ratings yet

- Lean Six Sigma in A Call Centre A Case Study PDFDocument14 pagesLean Six Sigma in A Call Centre A Case Study PDFthan zawNo ratings yet

- M Marketing 5th Edition Grewal Solutions ManualDocument25 pagesM Marketing 5th Edition Grewal Solutions ManualJonathanSwansonbwyi100% (53)

- ABL Annual Report 2013Document270 pagesABL Annual Report 2013Muhammad Hamza ShahidNo ratings yet

- The Concept of StrategyDocument38 pagesThe Concept of StrategySamuel Duyan100% (3)

- The Impact of Strategic Management On Mergers and Acquisitions in A Developing EconomyDocument101 pagesThe Impact of Strategic Management On Mergers and Acquisitions in A Developing EconomyleroytuscanoNo ratings yet

- Marketing Manager Chatgpt Swipe H3uJKVe8Document13 pagesMarketing Manager Chatgpt Swipe H3uJKVe8Justin HarveyNo ratings yet

- Ch11 Reward StrategyDocument11 pagesCh11 Reward StrategymehboobzamanNo ratings yet

Week 3 GreerVirick 2008

Week 3 GreerVirick 2008

Uploaded by

杨子偏Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Week 3 GreerVirick 2008

Week 3 GreerVirick 2008

Uploaded by

杨子偏Copyright:

Available Formats

10HRM47_2greer 5/7/08 11:21 AM Page 351

DIVERSE SUCCESSION PLANNING:

LESSONS FROM THE INDUSTRY

LEADERS

CHARLES R. GREER AND MEGHNA VIRICK

Although practitioners and academics alike have argued for succession plan-

ning practices that facilitate better talent identification and creation of

stronger “bench strength,” there has been little attention to the incorporation

of gender and racial diversity with succession planning. We discuss practices

and competencies for incorporating diversity with succession planning and

identify methods for developing women and minorities as successors for

key positions. Improvements in strategy, leadership, planning, development,

and program management processes are suggested. Recommendations for

process improvement are developed from the diversity and succession plan-

ning literatures and interviews of 27 human resource professionals from a

broad range of industries. © 2008 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Those being positioned as future lead- said, “I believe that companies that figure

ers tend to look and act an awful lot out the diversity challenge first will clearly

like people in those top positions . . . It have a competitive advantage” (Terhune,

simply reflects an adherence to tradi- 2005). A leading insurer, Allstate, also has

tional methods of succession plan- embraced diversity and sees it as a source of

ning. (Tom McKinnon, Novations competitive advantage, particularly in terms

Group) of expanding the number of minority poli-

cyholders (Crockett, 1999). Cosmetics maker

n emerging body of empirical evi- L’Oreal attributes its global success in devel-

A dence (e.g., Richard, 2000; Wright,

Ferris, Hiller, & Kroll, 1995) indi-

cates positive performance effects

for diversity, and there are increas-

ing indicators of the strategic importance of

diversity to the success of companies. Pep-

siCo’s previous CEO, Steve Reinemund, has

oping and marketing cosmetics to market-

ing initiatives that have drawn on interna-

tional diversity (Salz, 2005).

Aside from the impact of competitive

forces, some of the recent interest in succes-

sion planning may be attributed to the more

active role of boards of directors in response

Correspondence to: Charles R. Greer, Department of Management, Neeley School of Business, Texas Christian

University, Fort Worth, TX 76129, Phone: 817-257-7565, Fax: 817-257-6431, E-mail: c.greer@tcu.edu.

H u m a n R e s o u r c e M a n a g e m e n t , Summer 2008, Vol. 47, No. 2, Pp. 351–367

© 2008 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com).

DOI: 10.1002/hrm.20216

10HRM47_2greer 5/7/08 11:21 AM Page 352

352 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Summer 2008

to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and other meet the challenges posed by environmental

regulatory developments. We see striking ex- turbulence, shortage of talent, and globaliza-

amples of succession planning successes and tion (Karaevli & Hall, 2003).

failures in organizations. For instance, GE’s Although these examples concern high-

former CEO Jack Welch placed great empha- profile CEO succession, our broader ap-

sis on succession planning. One of his lega- proach involves succession to key manage-

cies was a process that allows the company, rial and professional positions and

which is a veritable CEO greenhouse, to de- incorporates diversity initiatives. While fail-

velop and promote talent from within the ures in diversity are reflected in enduring un-

organization (Gale, 2001). Companies such derrepresentation of women and minorities

as Bank of America, Dell, Dow in key positions, the combined effects of di-

Chemical, and Ely Lilly also have verse succession planning have received lit-

developed bench strength for tle attention. Nonetheless, companies such

While failures in their top positions by closely as Allstate are using succession planning to

diversity are linking leadership development increase diversity in key positions and

with succession planning (Con- women now occupy 40% of Allstate’s execu-

reflected in ger & Fulmer, 2003; Karaevli & tive and managerial positions, with 21%

Hall, 2003). McDonald’s provides being held by minorities (Kim, 2003). Suc-

enduring an unusual example of prepared- cession planning has also been critical to

ness in that the company was Harley-Davidson’s accomplishments in di-

underrepresentation

able to quickly designate a perma- versity, as 17% of its vice presidents are

of women and nent replacement within six women (PR Newswire, 2004).

hours of CEO Jim Cantalupo’s Although we are unaware of any empiri-

minorities in key death, compared to the typical cal evidence on the combined effects of di-

timetable of several months (Gib- verse succession planning, the importance

positions, the

son & Gray, 2004; Hymowitz & placed on both diversity and succession

combined effects of Lublin, 2004). A few months planning by several leading companies

later, when Cantalupo’s successor, makes the topic relevant for consideration.

diverse succession Charlie Bell, resigned because of Recent survey data also have called atten-

terminal illness, McDonald’s was tion to the importance of diversity practices

planning have

able to immediately appoint Jim for increased organizational competitive-

received little Skinner as CEO (Gray, 2004; ness (Esen, 2005). The significance of link-

McGuirk, 2005). ing diversity management with succession

attention. While there have been note- planning is that more robust succession

worthy successes with succession plans are produced and thus provide a

planning, companies have had strategic focus for the development of a di-

disappointments. At Coca-Cola, for example, verse workforce. With such linkage, the

Douglas Ivester replaced the late Robert planned succession of diverse talent pro-

Goizueta but lasted only two-and-a-half dif- vides more options for strategy formulation,

ficult years (Conger & Fulmer, 2003). While such as the pursuit of growth in diverse and

such failures may be attributed to flawed ex- global markets or innovation-based strate-

ternal searches, internal succession is often gies, while strategy implementation and op-

not an attractive option in the absence of erations benefit from the flexibility pro-

succession planning and development. Some vided by a deeper talent pool.

well-managed firms, such as Hewlett- Practitioners and academics alike have

Packard, Lincoln Electric, Southwest Airlines, argued for succession planning practices that

and Whole Foods Markets, place heavy em- facilitate better talent identification and cre-

phasis on promotion from within (Pfeffer, ate stronger bench strength, yet there has

1998) and treat succession planning as a crit- been little attention paid to the incorpora-

ical process. Improved practices and compe- tion of gender and racial diversity with suc-

tencies are needed for succession planning to cession planning. As companies attempt to

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

10HRM47_2greer 5/7/08 11:21 AM Page 353

Diverse Succession Planning: Lessons from the Industry Leaders 353

revitalize their succession planning, it is a Promotion-from-within policies, which

good time to address a major challenge for require some level of sophistication in suc-

these efforts—specifically, integrating diver- cession planning, also are positively associ-

sity with succession. This article addresses ated with measures of organizational per-

these concerns by identifying practices and formance (Delaney & Huselid, 1996). In fact,

competencies that can facilitate such inte- researchers have concluded that external

gration. We draw on results of interviews successors are likely to be effective in more

with human resource professionals along limited circumstances, such as when they are

with findings from the literature to identify brought in to help with poorly performing

suggestions for integrating the two processes. firms (Wei & Cannella, 2002).

The future of many organizations is

Performance Effects of Diverse likely to depend on their mastery

of diverse succession planning

Succession Planning

given that building bench The future of many

While little research has focused on the strength among women and mi-

performance effects of succession plan- norities will be critical in the organizations is

ning, some aspects of succession systems competitive war for talent. For

are related to financial performance (Fried- example, the U.S. Department of likely to depend on

man, 1986). Success factors include CEO Labor predicts that women and

their mastery of

involvement, rewards for developing sub- minorities will account for 70%

ordinates, “earnestness” of performance re- of the new participants in the diverse succession

views, forecasting the need for talent, and labor force in 2008 (McCuiston,

individual values consistent with organiza- Wooldridge, & Pierce, 2004). Fur- planning given that

tional values (Friedman, 1986). Succession thermore, women account for an

building bench

planning also has indirect impacts on increasing proportion of the

measures of firm performance such as pro- well-educated workforce and are strength among

ductivity and gross returns on assets forecasted to receive 60% of all

(Huselid, Jackson, & Schuler, 1996). Indi- bachelor’s degrees, 60% of all mas- women and

rect evidence of effective succession plan- ter’s degrees, and 48% of all doc-

minorities will be

ning also is provided by the lower failure toral degrees by 2014 (U.S. De-

rates of insider CEOs (Charan, 2005) and partment of Education, 2005). critical in the

the infrequency in which some very suc- Moreover, organizations lacking

cessful companies search beyond the firm effective diversity management competitive war for

to fill vacant CEO positions. A landmark programs often experience exces-

study of visionary companies found that sive turnover and high replace- talent.

poor succession planning caused gaps in ment costs, loss of investments

internal supplies of leadership talent, as de- in training, brand image prob-

scribed in the following statement: lems, poor employer image, and litigation

(Hubbard, 2004). Absence of diversity pro-

We found evidence that only two grams also may result in strategic opportu-

visionary companies (11.1 percent) nity costs such as unrealized market access

ever hired a chief executive directly or lack of awareness (D. A. Thomas & Ely,

from outside the company, compared 1996). Indeed, if the performance impact of

to thirteen (72.2 percent) of the com- diversity problems is approached in terms

parison companies. Of 113 chief execu- of litigation and related costs alone, the

tives for which we have data in the vi- costs for some leading companies such as

sionary companies, only 3.5 percent Coca-Cola ($102.5 million) and State Farm

came directly from outside the com- ($250 million) have been breathtaking

pany, versus 22.1 percent of the 140 (Hubbard, 2004).

CEOs at the comparison companies. The integration of diversity with succes-

(Collins & Porras, 1994, p. 172) sion planning requires an appropriate

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

10HRM47_2greer 5/7/08 11:21 AM Page 354

354 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Summer 2008

approach. Typically, organizations have (King, 1994; Miller & Crabtree, 1992). These

adopted one of three approaches to manag- approaches provide a search for meaningful

ing diversity: an assimilation view that content segments (Miller & Crabtree, 1992),

downplays differences; an access view that and a codebook is compiled from the cate-

focuses on building diversity in order to gain gories or themes that are created from an ini-

access to ethnic consumer groups; and an in- tial examination of the data or on an a priori

tegrated view that emphasizes uniform per- basis. The codebook is then revised as

formance standards, personal development, themes emerge from continued searches of

openness, acceptance of constructive con- the data (King, 1994).

flict, empowerment, egalitarianism, and a We identified several themes such as

nonbureaucratic structure that encourages communication related to program strategy,

challenges to the status quo (D. A. Thomas & values driving the process, and leadership

Ely, 1996). We argue that an integrated involvement. Computer search routines

approach and a culture of inclu- were then used to refine the organization of

siveness are critical for diverse content according to the themes and to rec-

succession planning. Next we de- oncile the content with the narrative of our

Our investigation scribe the methods used to exam- findings. We will discuss the practices that

ine the interface between diver- facilitate the integration of diversity with

was based on a sity and succession planning. succession planning, beginning with the

review of the organization’s business strategy. Informa-

tion on interviewee demographics, job ti-

Data Sources and Analysis

succession planning tles, and industries of their organizations is

Our investigation was based on a provided in Table I. As indicated in Table I,

and diversity review of the succession plan- there was substantial diversity in our group

ning and diversity literature and of interviewees.

literature and on 27

on 27 interviews of HR profes-

interviews of HR sionals from 25 different organi-

zations in the United States and

Practices and Competencies

professionals from one in Canada. Interviews were Our discussion of practices and competen-

conducted using a semistruc- cies follows a sequence of five processes that

25 different

tured format based on a set of reflect the order of succession planning. We

organizations in the seven questions that were revised begin with a discussion of integration of

as other issues became evident. strategy and planning. Figure 1 illustrates

United States and Questions such as the following this integration with a feedback loop of

were used for the initial inquiries: diverse talent influencing strategy formula-

one in Canada.

“What are some of the things tion. Next, we discuss leadership practices

that (your organization) does in and then move on to critical planning prac-

terms of the succession planning tices. We then focus on systematic ap-

of women and minorities?”; “Are there any proaches to development and mentorship

practices that link the management of diver- competencies, with special attention to para-

sity to succession planning?”; and “Are doxes and challenges. Finally, we address

there methods for increasing nominations program management practices and issues.

of diverse professionals for admission to the

pool of potential successors?”

Business Strategy

Notes taken during the interviews were

reviewed to identify practices or themes and The integration of diversity with business

then transferred to electronic files for analy- and human resource strategies, reflected in

sis with computer search routines. Because Figure 1, lays the foundation for identifying

we were concerned with identifying a broad the range of competencies and for designing

range of practices we used qualitative “edit- the developmental experiences required for

ing” and “template” analytical approaches succession. This integration process should

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

10HRM47_2greer 5/7/08 11:21 AM Page 355

Diverse Succession Planning: Lessons from the Industry Leaders 355

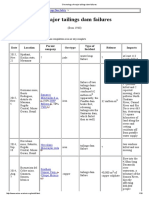

TABLE I Architecture for Intangibles

Gender Interviewees

Men 18

Women 9

Race Interviewees

Caucasian 18

African American 6

Hispanic 2

Asian 1

Job Titles Interviewees Job Titles Interviewees

President 2 Director of Diversity Council 1

Executive Vice President 1 Senior Human Resource Manager 1

Senior Vice President 3 Training Manager 1

National Managing Partner 1 Workforce Diversity Manager 1

Vice President 2 Human Resource Manager 1

Partner 1 Inspector—Career Development 1

Assistant Vice President 1 Human Resource Business Partner 1

Plant Manager 1 Human Resource Generalist 1

Senior Executive and Director 1 Senior Sourcing Specialist 1

Senior Director 1 Account Manager for College 1

Relations and Recruitment

Director 3

Industries Industries

Computer Manufacturing Gift Manufacturing

Commercial Real Estate Pharmaceuticals

Convenience Retailing Public Administration

Consulting Services Railway Transportation

Distilling Semiconductor Manufacturing

Electronics Manufacturing Specialty Retailing

Financial Services Specialty Services

Food Manufacturing Telecommunications

General Manufacturing Wholesaling

Note: Interviewees’ organizations included nine Fortune 500 publicly traded companies, with the remainder being foreign-held

companies, smaller publicly traded companies, privately held companies, small and large consulting firms, and one public-sector

organization. One of the interviewees had retired from his executive position to become a consultant and educator.

be continuous and flexible, because the versity (Liebman, Bruer, & Maki, 1996). Mo-

competencies for key personnel are likely to torola, PepsiCo, and IBM provide examples

change in the future (McCall, 1998). The ex- of other companies that integrate human re-

ample of GE (Hymowitz & Lublin, 2004; source development processes with business

Karaevli & Hall, 2003) demonstrates the crit- strategy (Childs, 2005; McCall, 1998). One

ical role of alignment with business strategy. of our interviewees stressed the importance

In GE’s continuous process of succession of communication about strategy and goals

planning, the CEO first sets objectives for of diversity initiatives. Without such

the various business units. The process of communication, individuals targeted for

setting objectives includes succession plan- development have no basis for comparing

ning as a key part of the decision framework developmental requirements with their aspi-

and involves attention to such issues as rations or for making informed decisions

staffing, backups for key slots, global issues, about program participation (Cespedes &

technical workforce development, and di- Galford, 2004).

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

10HRM47_2greer 5/7/08 11:21 AM Page 356

356 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Summer 2008

FIGURE 1. Diverse Succession Planning Practices and Competencies

Leadership Gamble, found that 100% of the CEOs in the

top group (defined as companies that have

Commitment and direct involvement by the built a sustainable pipeline of future leaders)

CEO and the senior leadership team are clear were involved with leadership development

threshold requirements for diverse succes- relative to only 65% of other companies

sion planning. A recent comparison by (Salob & Greenslade, 2005). Colgate-Palmo-

Hewitt Associates of 20 top companies, in- live, ranked among the best companies in di-

cluding such companies as 3M, GE, IBM, versity, devotes four sessions each year to de-

Medtronic, Pitney Bowes, and Procter & veloping plans for high-potential minorities

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

10HRM47_2greer 5/7/08 11:21 AM Page 357

Diverse Succession Planning: Lessons from the Industry Leaders 357

(Sherwood & Mendelsson, 2005). The rele- senior executives to personally mentor a

vance of senior leadership involvement is woman or minority. She also stressed the fre-

revealed as follows: quency of succession planning, noting that

they had a biannual succession planning

. . . bringing attention to diversity into exercise involving the CEO and the com-

succession planning processes [requires pany’s top 15 executives. In contrast, an in-

that] . . . that possible successors for key terviewee from another company with a

jobs are diversity-competent. Unfortu- fairly comprehensive succession planning

nately, only a small percentage of com- program indicated that until recently, the

panies take this seriously . . . CEOs and company had only addressed gender diver-

others who are committed to changing sity in a reactive manner by asking, during

the culture of their organizations to be the process of compiling lists of high poten-

better at welcoming and using diversity tials, whether any women candidates ought

must make sure that the people most to be considered. Slow progress

likely to replace them are strong on on diversity issues points to the

managing diversity. (Cox, 2001, p. 123) importance of having more re-

sponsive leadership. Aside from the

Leadership support for diverse succession

planning is also reflected in reporting rela- leadership provided

Planning

tionships. A recent survey of 1,700 HR exec- by CEOs and

utives found that a relatively small percent-

Forecasting Demand

age of the companies for which the diversity officers,

respondents worked (30%) had direct report- Although the demand for talent

ing relationships between their diversity offi- is driven by business strategy and management of

cers and their CEOs (Alleyne, 2005). On the the approach to diversity, the tal-

diversity should be

other hand, positions for chief diversity offi- ents and behavioral competencies

cers (CDOs) or vice presidents for diversity identified as requirements for fu- embraced by the

have been created at such companies as ture executive positions are likely

Abbott Labs, Boeing, Colgate-Palmolive, to change (Charan, 2005; McCall, entire leadership

Johnson Controls, Lockheed Martin, Price- 1998). One of the paradoxes of

team and not

waterhouseCoopers, and Starbucks. Approxi- planning is that with more turbu-

mately 20% of our interviewees noted the lent conditions, planning is more perceived as the

importance of top leadership involvement in difficult but it also becomes more

various capacities. One interviewee empha- valuable (Greer, 2001; Niehaus, exclusive domain of

sized the importance of a direct reporting 1988). Given the long develop-

the HR function.

relationship to the CEO and noted that she mental time horizons and the

had power to influence inclusion of women associated uncertainty, flexibility

and minorities in succession planning solely is best obtained with talent pool

by virtue of access to the CEO. Aside from approaches to succession planning as

the leadership provided by CEOs and diver- opposed to more position-specific targeted

sity officers, management of diversity should approaches, typically referred to as replace-

be embraced by the entire leadership team ment planning (Carnazza, 1982).

and not perceived as the exclusive domain of

the HR function (Childs, 2005).

Talent Identification and Assessment

In organizations that emphasize the use

of succession planning for development, Early identification of talent is important for

managerial accountability becomes impor- the development of broad range of experi-

tant (McCall, 1998). This may take the form ences needed to fill executive positions (Mc-

of mentoring. One interviewee, who led her Call, 1998), and our interviewees stressed the

company’s diversity efforts, noted top-level need to reach deeper into the organization.

involvement through the requirement for Fortunately, our understanding of early

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

10HRM47_2greer 5/7/08 11:21 AM Page 358

358 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Summer 2008

talent identification is improving, especially potential for diversity initiatives (Conger &

the role of learning and learning agility, Fulmer, 2003; Klimoski, 1997; Yeung, 1997).

which are critical indicators of success in Additional recommendations deal with

senior leadership positions (Lombardo & formalization, involving more decision

Eichinger, 2000). McCall and his colleagues makers, and the degree to which decisions

have identified several learning-oriented di- on participation should be centralized.

mensions that are helpful for early identifi- More specifically, it has been recommended

cation such as “seeks opportunities to learn,” that organizations should keep the list of

“is committed to making a difference,” “has high potentials subject to revision while

the courage to take risks,” “seeks and uses another recommendation is to allow for

feedback,” and “learns from mistakes” (Mc- self-nominations (Conger & Fulmer, 2003).

Call, 1998, pp. 128–129). Measures of learn- An interviewee noted the value of his com-

ing agility, defined as the ability and willing- pany’s human resource inventory system in

ness to learn from experience, or identifying employees who are ready for op-

the ability to learn as conditions portunities. Leaders in succession planning

Another interviewee change, also are available such as Eli Lilly, Hewlett-Packard, Citigroup,

(Eichinger & Lombardo, 2004; and the U.S. Army have adopted group

stressed the Lombardo & Eichinger, 2000). approaches that have the advantage of uti-

The common problem of nega- lizing more than one individual’s percep-

importance of tive bias in performance evalua- tions of potential (Karaevli & Hall, 2003).

tions for minorities makes meas- Along this line, Deloitte & Touche has

objective standards

ures of learning agility changed its succession process from one in

of potential and particularly relevant to the issue which the departing manager selected a suc-

of diverse succession planning. cessor to a more centralized approach. When

readiness for One of our interviewees noted vacancies arise in the top ranks, senior man-

her company’s reliance on a agers across the country review short lists of

promotion to offset

measure of learning agility in the candidates keeping diversity objectives in

unconscious biases use of data and on a measure of mind (Armour, 2003).

results orientation toward both A variant of this approach, noted by one

against women. deadlines and goals. interviewee, was to have decentralized identi-

One of the most heavily uti- fication of high potentials, along with some

lized approaches for identifying centralized oversight with interwoven diver-

talent for succession planning involves per- sity objectives. This approach was considered

formance evaluations. This approach has to be the key to her company’s success in suc-

problems, given evidence of negative bias in cession planning, and is consistent with or-

performance evaluations of minority man- ganizations such as Lockheed-Martin. When

agers (Kilian, Hukai, & McCarty, 2005). Com- oversight reveals that women and minorities

panies leading the way in developing minor- are not represented in developmental pro-

ity executives take a different approach by grams, managers are asked to provide expla-

emphasizing results, relying on objective in- nations. The manager of organizational effec-

dicators of competency, and focusing on tiveness has the authority to promote

measurable track records to identify talent developmental opportunities, even if it

(Thomas & Gabarro, 1999). One interviewee means changing succession plans (Bogan,

mentioned the use of an anecdotal profile of 2002). Replacement lists are also monitored

potential successors as an important compo- at companies such as IBM and Dow Corning

nent of assessment. Another interviewee (Salomon & Schork, 2003), and several inter-

stressed the importance of objective stan- viewees told us that their companies will not

dards of potential and readiness for promo- fill some jobs without conversations aimed at

tion to offset unconscious biases against having a diverse slate of candidates.

women. Assessment-center procedures are Another concern for talent identification

also used for succession planning and have is related to the residual effects of differences

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

10HRM47_2greer 5/7/08 11:21 AM Page 359

Diverse Succession Planning: Lessons from the Industry Leaders 359

in past assignments. Current successors to Boeing’s organization chart—or [those

top-level positions often have benefited from of] any of a thousand large publicly

prior advantageous developmental assign- traded companies—more often than

ments and have sometimes been selected not, they’re seeing a picture that does-

simply due to their similarity to past incum- n’t appropriately reflect their experi-

bents in terms of work experiences and ence.” He argued that that reality sim-

demographic characteristics of gender, race, ply must change in order for Boeing to

and age (Frase-Blunt, 2003). Such similarity maintain its market leadership. . . .

biases are more likely to occur in the absence (Orenstein, 2005, p. 234)

of formal succession planning (Rothwell,

2001). This heightens the need for defining Some interviewees noted the importance

competencies for senior-level positions in of developing a culture of inclusiveness as

terms of specific behaviors with the purpose employees look upward in the hierarchy to

of making the process more transparent and see if there are people who look

acceptable (McKinnon, 2003). like them. Minority employees

Certain technical planning practices are are likely to ask, “Is the environ-

also relevant to diverse succession. At Procter ment accepting of me?” Quick-fix Minority employees

& Gamble, top-level managers designate approaches that bypass develop-

three successors: an “emergency” replace- mental time, or methods based are likely to ask, “Is

ment, who is typically a peer who could fill on expediency, can produce ill- the environment

the position very quickly; a “planned” suc- prepared successors and cause

cessor, who will be prepared to fill the posi- problems in morale and turnover accepting of me?”

tion after some period of time if provided (Rothwell, 2001). As such, they

with the correct developmental experiences; should be viewed with caution.

and a potential “diversity” successor (Himel- As Charan (2005, p. 81) noted, “A quick

stein & Forest, 1997). In a similar vein, infusion of talent may be a company’s only

Motorola attempts to identify three succes- course, but it is no way to run a railroad.”

sors: an immediate replacement, someone Nonetheless, we found that some organiza-

who could fill the position with three to five tions obtain quick infusions of talent by

years of development, and the best qualified bringing in senior-level women and minori-

woman candidate beyond any already iden- ties from the outside or by relying on early

tified for the first two categories. Four years promotions. One of our interviewees noted

after the program’s implementation, the the symbolic importance of success stories

company increased the number of minority and reported successful use of judicious

women vice presidents from one to eleven pump priming with the early promotion of a

(Caudron, 1999; Himelstein & Forest, 1997). high-potential woman who improved the

environment for women engineers in his

company.

Dealing with Shortages

One approach for dealing with shortages of di- Development

verse talent when there is no time for longer-

term development is referred to as “priming

Systematic Approaches

the pump.” This approach encourages early

promotions or brings in diverse talent from Evidence indicates that companies with

the outside. The following account of a pres- good reputations for developing people,

entation to Boeing employees by James Bell, such as Colgate-Palmolive, Emerson Electric,

Boeing’s CFO and president, provides perspec- General Electric, Johnson & Johnson, Procter

tive on the need for rapid progress: & Gamble, and Sherwin-Williams (Charan,

2005), have been both systematic and per-

When high-potential young people sistent over a long period of time before hav-

from diverse backgrounds look at ing obtained results (Carnazza, 1982; Cha-

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

10HRM47_2greer 5/7/08 11:21 AM Page 360

360 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Summer 2008

ran, 2005; Conger & Fulmer, 2003). Succes- caused it” (R. Thomas, 1990). Other ob-

sion planning at the American Red Cross in- servers (Liff, 1997) and some of our

cludes talented women and minorities in interviewees also cautioned against special

special developmental programs and empha- succession planning programs for women

sizes communication and individual career and minorities. One interviewee, in refer-

development plans (Frase-Blunt, 2003). The ence to women and minorities in leadership

key to development lies in providing chal- ranks, stated that “the way they got there is

lenging assignments to high potentials with more important than the fact that they got

accountability for profit and loss and close there.” Interviewees also noted that pro-

evaluation of performance in these roles grams championed by only a few senior lead-

(Cappelli & Hamori, 2005; Cespedes & Gal- ers are unlikely to be successful in the long

ford, 2004; Charan, 2005). Women’s inexpe- term because of the lack of organizational

rience with profit-and-loss responsibility is support and the absence of a systematic ap-

one of the reasons for their slow proach. After the champions are gone, the

progress in obtaining senior-level programs often fail.

jobs (Catalyst, 2003). Many lead- Nonetheless, it has been argued that in

One of our ing companies have recognized the absence of special programs that are tar-

and are addressing this issue. Lat- geted specifically toward women and mi-

interviewees eral moves are especially impor- norities, very little is likely to change. Special

emphasized the tant in large complex companies programs have had an impact in some or-

dominated by engineering or ganizations, such as GE and Shell (Reinhold,

critical importance other technical work (Flynn, 2005), Deloitte & Touche (Anderson, 2005),

1998), since many key profes- and IBM (D. Thomas, 2004). However, such

of positioning sional positions are not on the programs reflect the reality of constrained re-

vertical career track. sources that prevent unlimited access for all

succession

Contact and visibility with employees. Special programs also address the

planning programs senior leaders is also important. problem of small numbers. As one interview-

The Hewitt study cited earlier ee pointed out, if women and minorities are

so that they focus found that 95% of the companies simply given the same assignments as every-

in the top group create such op- one else, some will get interesting assign-

on developing high

portunities for high potentials ments while others will not. Because of

potentials rather (Salob & Greenslade, 2005). One smaller numbers, when women and minori-

of our interviewees emphasized ties leave as a result of uninteresting or un-

than on diversity the critical importance of posi- challenging assignments, there are serious

tioning succession planning pro- problems for diversity objectives. We some-

per se.

grams so that they focus on de- times encountered contradictions in that in-

veloping high potentials rather terviewees initially noted the inadvisability

than on diversity per se. His ap- of special programs but later mentioned that

proach was to ensure diversity in the suc- their companies provided such programs for

cession pool, with the overall emphasis women and minorities.

being the creation of a “leadership pipeline Special challenges often occur in profes-

full of good people.” Special programs for sional settings when there are small propor-

women and minorities may be hindered by tions of women or minorities. In these cir-

the stigma of special treatment (Murrell & cumstances, they are visible because of their

James, 2001), and may not conform to the uniqueness and isolated because they have

special consideration test proposed by Roo- few diverse peers (Estlund, 2003). Interest-

sevelt Thomas because they are not open to ingly, when women comprise a small pro-

everyone (R. Thomas, 1990). As Thomas has portion in a professional setting, those in

stated, “Does this program or policy give early-career stages may not perceive senior

special consideration to one group? If so, it women as role models because they view

won’t solve your problem—and may have such women as lacking in power or behaving

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

10HRM47_2greer 5/7/08 11:21 AM Page 361

Diverse Succession Planning: Lessons from the Industry Leaders 361

more like men than women (Ely, 1994; Mur- Steve Reinemund encouraged mentoring

rell & James, 2001). across race and gender lines. More specifi-

Women employed in industries that rely cally, Reinemund required his direct reports

heavily on operations face such challenges. to serve as sponsors for diversity across race

One interviewee told us that women some- and gender lines. An African American serves

times faced so much difficulty in gaining ac- as the sponsor for white men, a white man

ceptance in operations that they simply con- sponsors African Americans, and a white

cluded it was not worth their effort to pursue woman sponsors Latinos (Terhune, 2005).

a career in the area. Another interviewee told PepsiCo’s current CEO, Indra Nooyi, has said

us that the old guard would conclude that a that the company wants its managers to be

woman might not be suited for a position “‘comfortable being uncomfortable’ so

because it was a “tough job” involving 24/7 they’re willing to broach difficult issues in

operations or unions. Other interviewees re- the workplace” (Terhune, 2005, p. B1).

ported difficulties in obtaining representa- Nonetheless, cross-race rela-

tion of women in technology areas, such as tionships require that mentors

chip design and manufacturing. These expe- have diversity skills. With cross-

rience gaps are critical, because operations gender mentoring relationships, When asked “Who

voids in the skill portfolios of women reduce there also can be problems unless

their opportunities to move into senior exec- mentors and protégés maintain was there for you in

utive ranks. appropriate levels of admiration, your darkest hour?”

informality, respect, and trust, and

act in a manner that does not cre- the group identified

Mentorship

ate public image problems (Claw-

Scholars have found differences in mentor- son & Kram, 1984). Not all men- a very small number

ing experiences when different races and tors perform well in such roles, but

of mentors, and the

genders are involved (Noe, Greenberger, & some are truly exceptional. One

Wang, 2002; Wanberg, Welsh, & Hezlett, interviewee told us that his com- same person was

2003). For example, when women are men- pany made this discovery when it

tored by women, they are likely to learn asked approximately 100 of its mi- identified by as

more about overcoming barriers to promo- nority and women employees

many as 20 to 25

tion and methods for achieving career and about their experiences with men-

family balance (Noe et al., 2002; Ragins & tors. When asked “Who was there individuals.

McFarlin, 1990). With same-race mentorship for you in your darkest hour?” the

relationships, there also tends to be more group identified a very small num-

psychological or social support (Noe et al., ber of mentors, and the same per-

2002; D. Thomas, 1990). However, because son was identified by as many as 20 to 25

of the scarcity of women and minorities in individuals. Thus, efforts to identify excep-

senior positions, cross-gender and cross-race tional mentors and leverage their skills

mentoring relationships are prevalent (Noe should be a priority. Another interviewee

et al., 2002; Ragins & Cotton, 1991; Wanberg emphasized the importance of training men-

et al., 2003). Nonetheless, cross-gender men- tors and the value of basic guidelines such as

toring relationships can add value because advising mentors to avoid discussions of sen-

they enable men and women to gain insights sitive issues like race until the parties have

and perspectives about how the other gender established a strong relationship. Good

handles workplace issues (Clawson & Kram, match-ups are always important, but are crit-

1984; Noe et al., 2002). ical when high-level executives are involved.

PepsiCo, which has been cited as a leader One interviewee told us that she personally

in diversity (Sherwood & Mendelsson, 2005; makes the high-level match-ups and lags the

Terhune, 2005), views cross-race mentorship notification to mentors by several days so

as more than a substitute for same-race or that mentees have an opportunity to anony-

same-gender mentoring. Its former CEO, mously decline a mentor.

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

10HRM47_2greer 5/7/08 11:21 AM Page 362

362 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Summer 2008

The retention of women and minorities, nition as a reward for mentors who per-

which is critical for program success, is being formed well, but that over time the company

addressed with a number of different prac- began to include such contributions in the

tices. A number of companies have been performance-appraisal process and linked

using affinity groups to provide informal financial rewards to these efforts. On the

guidance and networking assistance. For other hand, intrinsic rewards may be very

example, Nike now has such groups for powerful, particularly for minority mentors

African Americans, lesbians, gays, and other who mentor other minorities (Noe et al.,

minorities (Jung, 2005). One interviewee 2002; Ragins, 1997a, 1997b).

told us that a great deal of coaching is

needed in order to retain minorities and that

Confidentiality and Transparency Trade-offs

the senior executive in charge of diversity

needs to be heavily involved in these efforts, As with some other issues in diverse succes-

while another observed that suc- sion planning, there are differing views on

cession planning is closely related transparency. The Hewitt study noted earlier

to retention, but only when the found that 68% of the top companies in

Another interviewee company follows through with leadership development informed employ-

development. Another intervie- ees of their status as high potentials while

noted dramatically wee noted dramatically that or- only approximately 53% in the comparison

that organizations ganizations need to “throw their group of companies provided such informa-

arms around women and minori- tion (Salob & Greenslade, 2005). With trans-

need to “throw their ties” in order to retain them and parency, the career objectives of the candi-

that coaching and mentoring are date may be considered in developmental

arms around women key for their retention. He also planning. On the other hand, complete

reported that his organization is transparency may interfere with teamwork

and minorities” in

reaching down to minority pro- and demotivate those not included on the

order to retain them fessionals, even at entry level, to list (Conger & Fulmer, 2003; Yeung, 1997).

help them discover the hidden Informing employees of their readiness for

and that coaching messages that are critical to devel- promotion is a related issue. We saw varying

opment in the organization’s cul- levels of transparency. Whereas some of our

and mentoring are

ture. interviewees stressed the importance of

key for their transparency and informing employees of

Program Management their readiness in succession, other intervie-

retention. wees advocated the use of partial trans-

parency, where individuals are told that they

Reward Systems

are making a contribution but are not

Some companies are using reward systems to explicitly told that they are high potentials

motivate diverse succession. Senior execu- to avoid raising expectations.

tives at Denny’s have a strong incentive to be

responsive to diversity because the represen-

Measurement and Evaluation

tation of minorities and women in their di-

visions accounts for 25% of executives’ Ideally, evaluations should draw on both

bonuses (Brathwaite, 2002). At Hyatt, where qualitative and quantitative measures. Qual-

52% of the company’s managers are women, itative measures may include factors such as

diversity goals account for 15% of bonuses satisfaction with the process at multiple lev-

(Prince, 2005). When retention levels for els of the managerial hierarchy and across

high potentials drop below 90% at Colgate- gender and racial groups, as well as percep-

Palmolive, top-level managers lose money. tions of fairness and usefulness. Such meas-

Some companies have also implemented ures could include perceived smoothness of

rewards for mentors. One interviewee told us succession and the perceived quality of the

that his company initially used only recog- talent pool. Quantitative metrics may in-

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

10HRM47_2greer 5/7/08 11:21 AM Page 363

Diverse Succession Planning: Lessons from the Industry Leaders 363

clude measures such as the percentage of di- in diverse succession planning requires a

verse successors obtained internally, waiting clear understanding of the business strategy

time or ratios of “ready now” potentials to and communication of how the process will

incumbents, and reservoirs of cross-func- provide a source of competitive advantage.

tional or international experience, as well as Nonetheless, despite the rapid successes of a

attrition rates for diverse high potentials few leading organizations, senior leaders

(Conger & Fulmer, 2003). One of our inter- who seek to persuade their colleagues on the

viewees emphasized the importance of set- importance of diverse succession

ting diversity targets in anticipation of the planning should understand and

future racial composition of the United communicate to others that suc- One of our

States. His pragmatic justification of his or- cess in this area involves a long-

ganization’s adoption of special programs term commitment. interviewees

was that “you are not going to be successful Several practices appear to be

by osmosis.” Another interviewee, who important for success in this area, emphasized the

stressed the importance of measuring the im- and a summary of these practices importance of setting

pact of such programs with more than one and competencies is provided in

indicator, noted that her company uses 14 Table II. diversity targets in

different measures of program effectiveness, In summary, we need to un-

including retention, advancement, hiring, derstand how organizations can anticipation of the

and development. A different interviewee’s implement the guidance we re-

future racial

company conducts periodic “pulse surveys” ceived from one of our intervie-

of employees to determine satisfaction with wees, that organizations should composition of the

their career succession. Whatever the metric “throw their arms around

or diversity scorecard used, it is important to women and minorities.” We United States. His

allow sufficient time, perhaps four to five were deeply impressed by the

pragmatic

years, for the effects to be evident before a passion and commitment of our

program is evaluated and potentially dis- interviewees, many of whom justification of his

banded (Carnazza, 1982). shared deep feelings with us. We

point to the passion and persua- organization’s

siveness of champions of diver-

Implications for Practitioners adoption of special

sity and talented mentors as a

Industry leaders such as PepsiCo and Allstate means of selling the importance programs was that

provide examples of companies that have of the process to others in the

made diversity a part of their competitive organization. Nonetheless, we “you are not going to

strategies while others, such as GE, Eli Lilly, acknowledge that diverse succes-

and Dell Computer provide examples of sion planning is a sensitive area be successful by

companies that are very skilled at developing in many organizations since fu- osmosis.”

talent through succession planning. We have ture opportunities and limited

identified a number of competencies and numbers of developmental as-

practices being used by industry leaders to signments are at stake, particu-

increase diversity through the succession larly where greater progress in diversity is

planning process. Those who wish to excel needed. Although it is sometimes difficult

in this area will benefit from the knowledge to obtain candid answers about diverse suc-

of industry leaders that we have attempted cession planning practices, there is much

to convey in this article. As we have noted, to learn in most organizations about this

some leading companies recognize the per- issue and much to be gained in terms of

formance effects to be gained from excel- competitive advantage. Further investiga-

lence in managing diversity and the value tion of questions, such as one posed by one

that may be created through such initiatives. of our interviewees, would seem to add

The persuasion of others to support the de- value. The surprising answer to his ques-

velopment of organizational competencies tion, “Who did you turn to in your darkest

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

10HRM47_2greer 5/7/08 11:21 AM Page 364

364 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Summer 2008

TABLE II Suggestions for Diverse Succession Planning

Strategic Integration

• Obtain alignment between business strategy and diverse succession planning.

• Frame programs with emphasis on developing “high potentials.”

• Communicate the strategy and goals of the program.

Leadership

• Establish a values basis for diverse succession.

• Obtain commitment of top executives to personally mentor diverse successors.

• Include diversity goals in performance evaluations of executives and managers.

• Establish close contact between the CEO and the chief diversity officer.

• Establish authority and accountability for diverse succession goals.

• Involve the chief diversity officer in all succession decisions.

Planning Processes

• Identify behavioral competencies for the future while recognizing that these may change.

• Disseminate descriptions of specific behavioral competencies required for top positions.

• Conduct deep internal searches for diverse high potentials.

• Rely on assessments from credible mentors.

• Evaluate recruiting programs for their impact on diversity.

• Use valid objective testing where feasible to offset unconscious bias in assessment.

• Use valid objective indicators of performance, competence, and potential where possible.

• Use valid learning-oriented early identifiers of executive ability.

• Use valid measures of results orientation to identify high potentials.

Development Practices

• Develop behavioral competencies for training, development planning, and evaluations.

• Focus on the advantages of same-race/gender or cross-race/gender mentorship.

• Provide anonymous procedures for mentees to decline pairing with potential mentors.

• Provide opportunities for diverse high potentials to gain exposure with senior executives.

• Create critical masses of diverse talent to prevent tokenism and related effects.

• Use ”pump priming” where appropriate to signal commitment and opportunity.

Program Management Practices

• Monitor flows of diverse successors into core areas as opposed to periphery functions.

• Identify effective mentors and leverage their skills.

• Include diverse succession in executive performance evaluation and reward systems.

• Inform high potentials of their inclusion in succession plans and obtain their inputs.

• Monitor succession and high-potential programs for representation of diversity.

• Evaluate diverse succession planning with multiple metrics such as retention, development,

advancement, and size of the “ready now” talent pool.

hour?” indicates that there is much to learn Acknowledgments

in most organizations.

Those organizations that excel at manag- The authors would like to acknowledge questions

ing diversity will need to be creative in de- posed by Shannon Ryan, executive vice president,

veloping programs that reduce the negative Stagen Leadership, Inc., which provided focus for

side effects of special programs for women our inquiry. In addition, they would also like to ex-

and minorities. Such programs pose a para- press their appreciation for insights provided by

dox, because while the conventional wisdom John Baum, Jim Combs, John Delaney, Mark

is that they should not be adopted, they ap- Huselid, Shirley Rasberry, Lynn Wooten, and two

pear to be necessary for progress. anonymous reviewers.

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

10HRM47_2greer 5/7/08 11:21 AM Page 365

Diverse Succession Planning: Lessons from the Industry Leaders 365

CHARLES R. (BOB) GREER is a professor of management at Texas Christian University.

He has published in such journals as the Academy of Management Journal, the Acad-

emy of Management Review, Organization Science, California Management Review,

Organizational Dynamics, and Industrial Relations. He is the author of Strategy and

Human Resources: A General Managerial Approach and was coeditor of the Blackwell

Encyclopedic Dictionary of Human Resource Management. He is an active labor arbitra-

tor and is on the labor panels of the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service and the

American Arbitration Association.

MEGHNA VIRICK is an assistant professor at San Jose State University. She received her

doctorate in business administration at the University of Texas at Arlington. She holds a

diploma in industrial relations from XLRI, India, and an MBA from Texas Christian Uni-

versity. Her current research focuses on diversity, work and family conflict, underem-

ployment, and the effects of job loss.

REFERENCES Clawson, J. G., & Kram, K. E. (1984). Managing cross-

gender mentoring. Business Horizons, 27(3), 22–32.

Alleyne, S. (2005). But can you walk the walk. Black Collins, J. C., & Porras, J. I. (1994). Built to last: Suc-

Enterprise, 35(2), 100–106. cessful habits of visionary companies. New York:

HarperCollins.

Anderson, R. (2005). Welcome to the diversity and in-

clusion initiative. Deloitte & Touche USA LLP. Re- Conger, J. A., & Fulmer, R. M. (2003). Developing your

trieved February 29, 2008, from http:// leadership pipeline. Harvard Business Review,

www.deloitte.com/dtt/article/ 81(12), 76–84.

Armour, S. (2003, November 24). Playing the succes- Cox, T., Jr. (2001). Creating the multicultural organiza-

sion game. USA Today, p. 3B. tion: A strategy for capturing the power of diver-

sity. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bogan, C. (2002). Best practices in career path defini-

tion and succession planning. Chapel Hill, NC: Best Crockett, J. (1999, May). Winning competitive advan-

Practices, L.L.C. (revised 2005). tage through a diverse workforce. HR Focus, pp.

9–10.

Brathwaite, S. T. (2002). Denny’s: A diversity success

story. Franchising World, 34(5), 28–29. Delaney, J. T., & Huselid, M. A. (1996). The impact of

human resource management practices on percep-

Cappelli, P., & Hamori, M. (2005). The new road to the

tions of organizational performance. Academy of

top. Harvard Business Review, 83(1), 25–23.

Management Journal, 39, 949–969.

Carnazza, J. (1982). Succession/replacement planning

Eichinger, R. W., & Lombardo, M. M. (2004). Learning

programs and practices. New York: Center for

agility as a prime indicator of potential. Human Re-

Research in Career Development, Columbia Busi-

source Planning. 27, 12–15.

ness School, Columbia University.

Ely, R. J. (1994). The effects of organizational demo-

Catalyst. (2003). Women in U.S. corporate leadership:

graphics and social identity on relationships

2003. New York: Author.

among professional women. Administrative Sci-

Caudron, S. (1999). The looming leadership crisis. ence Quarterly, 39, 203–238.

Workforce, 78(9), 72–79.

Esen, E. (2005). 2005 workplace diversity practices:

Cespedes, F. V., & Galford, R. M. (2004). Succession Survey report. Alexandria, VA: Society for Human

and failure. Harvard Business Review, 82(6), 31–42. Resource Management.

Charan, R. (2005). Ending the CEO succession crisis. Estlund, C. (2003). Working together: How workplace

Harvard Business Review, 83(2), 72–81. bonds strengthen a diverse democracy. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Childs, J. T., Jr. (2005). Managing workforce diversity

at IBM: A global HR topic that has arrived. Human Flynn, G. (1998). Texas Instruments engineers a holis-

Resource Management, 44, 73–77. tic HR. Workforce, 77(2), 26–30.

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

10HRM47_2greer 5/7/08 11:21 AM Page 366

366 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Summer 2008

Frase-Blunt, M. (2003). Moving past ‘mini-me’: Build- well encyclopedic dictionary of human resource

ing a diverse succession plan means looking be- management (pp. 10–12). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

yond issues of race and gender. HR Magazine,

Liebman, M., Bruer, R. A., & Maki, B. R. (1996). Suc-

48(11), 95–98.

cession management: The next generation of suc-

Friedman, S. D. (1986). Succession systems in large cession planning. Human Resource Planning, 19,

corporations: Characteristics and correlates of per- 16–29.

formance. Human Resource Management, 25,

Liff, S. (1997). Two routes to managing diversity: Indi-

191–213.

vidual differences or social group characteristics.

Gale, S. F. (2001). Bringing good leaders to light. Train- Employee Relations, 19, 11–26.

ing, 38, 38–42.

Lombardo, M. M., & Eichinger, R. W. (2000). High po-

Gibson, R., & Gray, S. (2004, April 20). Death of chief tentials as high learners. Human Resource Man-

leaves McDonald’s facing challenges. Wall Street agement, 39, 321–329.

Journal, pp. A1, A16.

McCall, M. W. (1998). High flyers: Developing the next

Gray, S. (2004, November 24). Naming Skinner CEO, generation of leaders. Boston: Harvard Business

McDonald’s shows its executive depth. Wall Street School Press.

Journal, p. B2.

McCuiston, V. E., Wooldridge, B. R., & Pierce, C. K.

Greer, C. R. (2001). Strategic human resource man- (2004). Leading the diverse workforce: Profit,

agement: A general managerial approach (2nd prospects and progress. Leadership and Organiza-

ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. tional Development Journal, 25, 73–91.

Himelstein, L., & Forest, S. A. (1997, February 17). McGuirk, R. (2005, January 17). Cancer claims ex-Mc-

Breaking through. Business Week, p. 64. Donald’s CEO Bell at 44. Associated Press

Hubbard, H. E. (2004). The diversity scorecard: Evalu- Newswires.

ating the impact of diversity on organizational per- McKinnon, T. (2003). Building a diversity succession

formance. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Butterworth–Heine- plan you can really use. Presentation at the Ameri-

mann. can Society for Training and Development, ASTD

Huselid, M. A., Jackson, S. E., & Schuler, R. S. (1996). 2003 International Conference and Exposition. San

Technical and strategic human resource manage- Diego, CA.