Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lewis Dances Among The Elves

Lewis Dances Among The Elves

Uploaded by

Dale SweezeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lewis Dances Among The Elves

Lewis Dances Among The Elves

Uploaded by

Dale SweezeCopyright:

Available Formats

C.S.

Lewis Dances among the Elves: A Dull and Scholarly Survey of "Spirits in Bondage"

and "The Queen of Drum"

Author(s): Joe R. Christopher

Source: Mythlore , Spring 1982, Vol. 9, No. 1 (31) (Spring 1982), pp. 11-18, 47

Published by: Mythopoeic Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/26810124

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mythopoeic Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Mythlore

This content downloaded from

35.146.198.8 on Wed, 04 Oct 2023 12:24:54 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MYTHLORE 31: Spring 1982 page 11

C.SHewis T)ances among the Clves

A Dull and Scholarly Survey of Spirits in Bondage and "The Queen of Drum"

JoeR. Christopher

Scholarly Guest of Honor at the 12th Annual Mythopoeic Conference

L An Introduction1 sphere. Of these the one is always

in danger of becoming useless by a

Strange as it may sound, when individuals daring negligence, the other by a

are invited as scholarly guests of honor, they scrupulous solicitude. The one

are expected to read dull and scholarly papers collects many ideas but confused and

to prove they were appropriately chosen. indistinct, the other is busied in

Even when the theme is something as lively, as

mercurial and hard to hold onto, as faerie, minute accuracy, but^without compass

and without dignity.

these individuals are expected to produce dull

and scholarly papers. As C. S. Lewis said I assume that bibliographers are an example of

under-an analogous circumstance, I will do my the latter. We are concerned with page numbers

best. and whether we are supposed to punctuate our

The mention of Lewis comes in appropriately listings by the University of Chicago style or

the MLA style—a matter, most of the time, of

for I want to consider his poetic references a colon vs. a comma. Only rarely do we lift

to fairies and elves. We often think of our heads from our stacks of books and Xeroxes

Tolkien as being the expert on elves. Indeed, of articles to contemplate the world outside

being Mythopoeic Society members, we probably our studies.

always think of Tolkien, whether or not it is

about his connection to elves. But C. S. Lewis But you have summoned me to this strange

was born in Ireland, back before it was world away from my desk where three large paper

politically divided into .Northern Ireland and sacks are filled with journals and copies of

Eire, and the Irish, as everyone knows, are articles I haven't gotten to yet, where a

born with second sight. (And if Lewis did not cardboard box holds large-sized books awaiting

have second sight, I'm sure he had third.) reading, where I have a stack of doctoral

What I want to consider are his few poetic dissertations in Xeroxy copies purchased by a

examples of that sight. grant and not yet read, where I slowly but

But first, a warning. Dr. Johnson—the inevitably get further and further behind on

appropriate man to issue warnings—writes in the flood of materials appearing. What am I

his forty-third Rambler essay: doing here? I should be reading and

annotating!

There seem to be some souls suited

to great and others to little Nevertheless, you have summoned me, and

employments; some formed to soar I emerge like an owl into the light, blinking,

aloft and take in wide views, and nervous, unhappy. What a strange world you

others to grovel on the ground and have. An oriental dancer at your masquerade,

confine their regard to a narrow a vampiress who reads a scholarly paper, a

This content downloaded from

35.146.198.8 on Wed, 04 Oct 2023 12:24:54 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MYTHLORE 31: Spring 1982 page'12

ooet in a Scottish kilt. And, strangest of No Dryads have I found in all our

ail, an initiation into the Grail Mysteries. trees.

You seem to take the wide views, while, in Dr. No Triton blows his horn about our

Johnson's phrase, I grovel on the ground and seas

concern myself with minutiae. Let me share And Arthur sleeps far hence in

my littleness, my scholarly point of view, Avalon.

with you. It is also obvious that these last two poems,

at the surface level, contradict each other.

II. Elves in Bondage and Elsewhere In one case, Lewis has seen an elf and in the

Before I consider the work I am primarily next, the faeries are gone. It's a

mysterious world.

concerned with, "The Queen of Drum," let me

cffer a brief survey of Lewis's other poetic Most of the rest of the poems, I would

references of faeries and elves. I start suggest, treat the faeries basically as a

with the obvious place. Spirits in Bondage, symbol of the mysterious, the Romantic, the

published in 1919 under the pseudonym of Clive dream of escape. In short, they are

Hamilton. First, a limitation.' I really am psychological symbols. This has already been

just interested in Lewis's references to elves seen in "Autumn Morning." For another

and fairies. There are fascinating things in example, in "'Our Daily Bread'" (No. 32),

this first book—Lewis's view of Ireland and Lewis writes of his experiences of Sehnsucht;

one poem about' an Irish god; two poems about he begins with the mysteries around people,

girls with red hair. There are references whether or not they hear the call of "Living

to supernatural beings, some of whom may be voices" as he has:

related to the elven kind. But these are ... some there are that in their

not to my present purpose. daily walks

Even with these limits, there are eleven Have not met archangels fresh from

poems in my category. One of these may be sight of God,

eliminated at once. "Tu We Quaesieris" (No. Or watched how in their beans and

37) uses elf in the eighteenth-century poetic cabbage-stalks

meaning of man. In this case, Lewis is Long files of faerie trod.

speaking of himself. For Lewis in these early years, angels as well

... what were endless lines to me as faeries could be only considered psychologi

If still my narrow self I be cal symbols.

And hope and fail and struggle still. Even clearer is this psychological

And break my will against God's will, projection in the poem "In Praise of Solid

To play for stakes of pleasure and People" (No. 24). In this poem, Lewis, in

pain contrast with the unimaginative, suburban

And hope and fail and hope again. people he praises, is a dreamer:

Deluded, thwarted, striving elf...

And soon another phanton tide

But this leaves ten poems. Only one of the Of shifting dreams begins to play.

others uses the term elf, but it obviously uses

it in the sense I am after. This is "The And dusky galleys past me sail.

Autumn Morning" (No. 21). In it Lewis writes Full freighted on a faerie sea;

that he is I hear the silken merchants hail

Across the ringing waves to me.

One that has honoured well

The mystic spell And then, suddenly, he awakes from the dream

and is back in his room.

Of earth's most solemn hours

Wherein the ancient powers Two others which belong in this class are

Of dryad, elf, or faun "Ballade Mystique" (No. 28) and "Night" (No.

Or leprechaun 29). In the former, Lewis contrasts (or, at

Oft have their faces shown

least the speaker contrasts, for it is not so

obviously Lewis this time) his contentment in

To me that walked alone an isolated house with his friends' worry about

Seashore or haunted fen him. He describes the visions he has seen,

Or mountain glen. and "L'Envoy" concludes:

This is typical of several poems in that it The friends I have without a peer

4

mixes the classical beings (the dryad, the Beyond the western ocean's glow,

faun) and the Anglo-Irish (the elf, the Whither the faerie galleys steer.

leprechaun). Lewis, of course, continued They this human friends1 do not

to mix his myths in this later life, know: how should they know?

specifically, in Narnia.

In "Night" Lewis describes a "Druid wood" in

Another poem with a catalogue may be which he would spend the titular period; there

considered with this one. In "Victory" (No. the owls

4), the poem begins three stanzas of the decay Hear the wild, strange, tuneless song

of ancient matters, only to contrast their Of faerie voices, thin and high

loss with man's spirit which goes on striving; As the bat's unearthly cry. . . .

here is the second stanza:

A verv odd comparison. The owls also hear the

The faerie people from our woods are sound of the faery dance all night long. The

gone. faeries seem to be the qroup called "The windy

This content downloaded from

35.146.198.8 on Wed, 04 Oct 2023 12:24:54 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MYTHLORE 31: Spring 1982 pogeU

people" in this poem; at any rate, Lewis sing as the Muse's impulses move them.

further identifies them with supernatural Perhaps we gain something by calling the

beings living under the sea, probably in a Muse the poet's inner psyche, perhaps not.

borrowing from Irish myth. The here in the But for this study, the important thing is

second line of this excerpt may refer to the that this foreshadows the division of

grove with which the poem began or it may, by realms found in "The Queen of Drum."

this time, refer to "some flowery lawn" where

the faeries dance: Three of these early poems remain to be

considered. Two of them present arguments,

Kings of old, I've heard them say, "Song" (No. 26) and "Itymn (for Boys' Voices)"

Here have found them faerie lovers (No. 31). The first begins:

That charmed them out of life and

kissed Faeries must be in the woods

Their lips with cold lips unafraid, Or the satyrs' laughing broods—

And such a spell around them made Tritons in the summer sea,

That they have passed beyond the Else how could the dead things be

mist Half so lovely as they are?

And found the Country-under-wave Thus, it says, only through the participation

This poem, after beginning with the psychologi of lesser spirits can nature be given its

cal wish for escape, it sounds like, turns beauty in the eye of human beholders. Probably

more descriptive than thematic: the details this should be read in a very Romantic context:

are elaborated, rather than the theme stated— the only way out of an egotistical position,

which is, after all, one of the bases of art. in which the Romantic observer projects meaning

into nature, is an affirmation of a spiritual

One more poem belongs to this dream of essence in nature. Wordsworth, in "Lines

escape I have been tracing. In "Song of the Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey,"

Pilgrims" (No. 25), the speaker is on a journey found "A motion and a spirit, that... rolls

to escape back of the North Wind, to reach that through all things". Lewis writes later in the

mysterious far land far to the North. For poem:

Lewis this Hyperborean dream may have come Atoms dead could never thus

partially from George MacDonald *s children's Stir the human heart of us

book, although we are more likely to think of

an "invented" myth in Ursula K. LeGuin's The Unless the beauty that we see

Left Hand of Darkness. At one point Lewis The veil of endless beauty be....

describes this land and presents The other poem with an argument is more like

... poets wise in robes of faerie Shelley than Wordsworth. In "Hymn (For Boys'

gold Cwho"3 Voices)", Lewis begins:

Whisper a wild, sweet song that first All the things magicians do

was told Could be done by me and you

Ere God sat down to make the Milky Freely, if we only knew.

Way. Human children every day

So far, all of these poems of escape Could play at games the faeries play

have associated faerie with the place of If they were but shown the way.

escape. But Lewis is not consistent. In one This is something like.the thesis of

poem, "World's Desire" (No. 39), Lewis Prometheus Unbound: the revolution can be

describes a castle which the speaker and his produced by a change in mental attitude.

love will flee to, a place with gardens and In his usual identification of faerie—who

"lovely folk"—but are mentioned in the foregoing passage—with

Through the wet and waving forest

the land of desire, Lewis writes later in the

poem:

with an age-old sorrow laden

Singing of the world's regret We could reaqh the Hidden land

wanders wild the faerie maiden. And grow immortal out of hand

Through the thistle and the brier, If we could but understand!

through the tangles of the thorn. The parallelism of the stanzas provides the

Till her eyes be dim with weeping identi f ication.

and her homeless feet sire torn.

Often to the castle gate up she looks Finally, there is a curious poem—"The

with vain endeavour. Satyr" (No. 3). It begins with two stanzas

For her soulless loveliness to the on the setting and action:

castle winneth never.

When the flowery hands of spring

Here, obviously, is a touch of the later Forth their woodland riches fling.

Lewis. The important term is the faerie's Through the meadows, through the

"soulless loveliness." Despite the fact valleys

that Lewis was antitheist at this time, Goes the satyr carolling.

as is clear in many of the poems which I From the mountain and the moor.

have not discussed and as is clear from his Forest green and ocean shore

summary of his life in Surprised by Joy, All the faerie kin he rallies

nevertheless the faerie is excluded from Making music evermore.

this castle of the world's desire because

she has no soul.5 Of qourse, it is given After three stanzas'describing the satyr—

to philosophers to be donsistent, if they Freudians will be interested in the emphasis

can, while poets have often been known to on his horns in the third of these—the doem

This content downloaded from

35.146.198.8 on Wed, 04 Oct 2023 12:24:54 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MYTHLORE 31: Spring 1982 page 14

ends with this stanza: Standing straighter as the strain

Faerie maidens he may meet loudened.

Fly the horns and cloven feet. Either shoulder

But, his sad brown eyes with Was swept with wings; swan's down

wonder they were,

Seeing—stay from their retreat. Elf-bright his eyes.

(11. 516-518, 528-533, 536-538)

As with all sexual poems, it is tempting to

read the verse in terms of Lewis's sexual He is later called an elf by the magician in

biography—so much are we influenced by Freud. the story (1. 683) and by the narrator (1. 711),

But, despite the temptation, I think something even though in the last reference to the,elf

else is of at least equal interest here. The he is called "that winged boy" (1. 727). I

emotional appeal of the satyr here is various: trace these references—fulfilling my promise

an image of energy, of singing, at the first; to be thorough and scholarly—but I do not

a combination of the humane and bestial in think they add much to my theme. Lewis here

the description I have omitted; and a sadness is doing something very special with the elf

at the flight of the faerie maidens at the end. figure, and he is not pure elf. Indeed, to

It is no doubt tempting to draw analogies to be brief, he is half angel, as the wings show;

the humanization of the fauns in Narnia, but at the end of the poem he is playing the role

that too I find misleading. of the angel guiding the ship of saved souls

to Mount Purgatory in Dante's Divine Comedy.

What I see here is a typical Victorian As I said, I have to say much about this poem

split between-the sexes, which I assume Lewis or very little; what I need to say in this

catches out of his childhood environment. That paper is only this: the elf does not function

is, men are half intellects and noble emotions, here as the emblem of escape. This poem is

and half beasts below. But women, if we read dated, as was said, in 1930, which was in the

this poem within the context of Spirit of midst of Lewis's return to Christianity; he

Bondage, are ideals, for they are called is trying to reshape the elfin figure to his

faeries; further, they do right to flee new beliefs. I will return to this point

men, but they may be caught—with all of the later.

bestiality that implies—by their sympathy

for the man's psychological pain. This is IV. "The Queen of Drum'

very Victorian, and most of us, if not all of

us, would say it is very wrong. But it shows I finally reach "The Queen of Drum." Let

Lewis as a product of his time, and for my me give a summary of the poem for those who

purposes it has the proper emphasis on the have not read it recently.

faeries as ideal figures. The women here are

not erotic sylphs. After a brief opening section suggesting

dreams and waking (Narrative Poems, p. 131),

Itl A Brief Comment on the rest of Canto I tells of the King of Drum

being gotten up, of his meeting the Queen in

"The Nameless Isle" the halls of the castle, she being just back

from a night of roaming the countryside and of

This survey of eleven poems in Spirits in him calling her a Maenad (p. 133), which is the

Bondage has, I believe, established the land first of several classic* references. Later,

of faerie as an ideal of Romantic escape and the King's Council meets, at the end of which

the faeries, with one or two clear exceptions, the Chancellor denounces the Queen; she

as the attractive inhabitants of this golden appears, and says that they have all so

realm. This still applies in "The Queen of wandered at night in their dreams (Canto I,

Drum." But first I would like to briefly pp. 131-140). Canto II. That afternoon the

mention "The Nameless Isle" (written in 1930 King and Chancellor meet, drink wine, and

and published in Narrative Poems in 1969). discuss the Queen, who was taken from the

The reason X briefly mention itis that I meeting by the Archbishop, the King and the

must either say almost nothing or a great Chancellor saying she travelled bodily rather

amount. I have an unpublished paper at home than just in dreams. For their own political

on it, saying the latter. Here, I will have purposes, they decide to get Jesseran, a

to pass it over quickly. At the end of this fortune-teller—or his corpse—out of the

poem, which is Lewis's retelling and modifi dungeons beneath the castle (Canto II, pp.

cation of Mozart's The Magic Flute—and one 141-147).

of the most archetypal works Lewis ever wrote, Canto III. As the King and Chancellor

outside, perhaps, of Perelandra—at the end of

this poem, a dwarf who has been involved in descend into the dungeons, the Oueen and

the action of the poem turns into an elf with Archbishop talk in a tower; with her

feathery wings. I quote some passages: insistence on his information about another

realm of experience, he has to abandon his

He laid his lip to the little flute. worldliness and speak of the Christian

Long and liquid,—light was waning— understanding of Hell and Heaven. She rejects

The first note flowed. his views, but before the argument is settled,

...it sang so well. guardmen appear to conduct them to the General

First he fluted off his. flesh away (the General who first appeared in the Council

The shaggy hair; and from his meeting) who has taken over Drum (Canto III,

shoulders next pp. 148-55). Canto IV. The General has

Heaved by harmonies the hump away; locked the door of the dungeon behind the

Then he unbandied, with a burst of King and Chancellor—so they will stay down

beauty, his legs. there—and he informs the Oueen she will

This content downloaded from

35.146.198.8 on Wed, 04 Oct 2023 12:24:54 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MYTHLORE 31: Spring 1982 page 15

become his wife; she says that she cannot Not to such purpose was the plucking

submit in front of all his men—but will at my heart

discuss the matter later. He sends her Wherever beauty called me into lonely

under guard to her tower, and she knocks places,

down the one guard and escapes from the Where dark Remembrance haunts me with

palace. Meanwhile, the General asks the eternal smart.

Archbishop to run a state church, supporting Remembrance, the unmerciful, the well

his rule; the Archbishop refuses and is of love.

killed—beaten to death—by the General's Recalling the far dances, the far

men (Canto IV, pp. 156-165). Canto V. The distant faces.

Queen flees, pursued by men with dogs; she Whispering me "What does this—and

finally reaches the mountains, after having this—remind you of?"

offering herself to Artemis; there, where How can I cease from knocking or

three roads diverge in a valley, she meets forget to watch—'

an elf who urges her to take the center path— (p. 153, 11. 190-201)

in a vision she sees the Archbishop/, who She calls them "immortals" because the elves

urges her to submit herself to God; but she lived until the Day of Judgment (at least, in

refuses, and takes the middle path to the most accounts). The call of beauty here is

realm of the elves (Canto V, pp. 166-175). earlier called by the Queen an "unbounded

In this summary, brief and inadequate as appetite for larger bliss / Not born with me,

it is—if I had more time I would read but older than my mortal birth" (p. 150, 11.

passages from" the poem to give you its flavor— 75-6). Bliss may not be quite the same as

in this summary, you will have caught the Lewis's use of joy.in Surprised by Joy, but I

essential points in the pattern we have been believe he is pointing to the same phenomenon.

following. The Queen goes to the far hills The Queen's actual moment of decision, of

in a quest for some sort of night-time final decision, when it comes in Canto V, is

meaning. Finally, chased by men and dogs, established with a traditional image. She

she goes toward them in the daytime but reaches a moonlit valley:

reaches them in the night. I will quote the

significant passages in a moment from the Down into it, and straight ahead,

conclusion. A single path before her led,

First, the poem needs a context of Lewis's —A mossy way; and two ways more

life. Walter Hooper has traced the sequence There met it on the valley floor;

of the poem's composition, from its first From left and right they came, and

right

mention in Lewis's diary in 1927, which And left ran on out of the light,

traced it in various forms back to 1918, when (p. 171, 11. 163-8)

Lewis was twenty-one. Walter Hooper thinks

the poem was completed about 1933-34 (Narrative The "elfin emperor" who meets her there

Poems, Preface, p. xiii); certainly it was identifies them for her:

finished by 1938 when Lewis read parts of it 'Keep, keep,' he bade her, 'Uoln the

at a summer program in Oxford. Thus it was midmost moss-way,

written during the period of Lewis's conversion Seek past the cross-way to the land

but over a longer period than with "The you long for.

Nameless Isle." In this poem, however, Lewis

treats religion differently than he does Heed not the road upon the right—

before or after. 'twill lead you

Let me begin with the identification of To heaven's height and the yoke

the Queen's search with those I have traced in whence I have freed you;

Spirits in Bondage. In the conversation Nor seek not to the left, that so

between the Queen and the Archbishop, the you come not

connection is clear. It is the Archbishop Through the world's cleft into that

who identifies it with the elves: world I name not.'

(pp. 172, 11. 199-200,

'How can it profit us to talk 201-4)

Much of that region where you say

you walk. These three roads are the same three the Queen

We are not native there: we shall of Elfland points out to Thomas in the Scottish

not die ballad "Thomas Rymer" (Child Ballad No. 37):

Nor live in elfin country, you and "O see not ye yon narrow road.

I.' (p. 149, 11. 59-62) So thick beset wi' thorns and

briers?

The Queen, in a reply to his presentation of That is the path of righteousness,

Christian other realms, identifies her search

with the call of beauty: Tho after it but few enquires.

'Where is my home

"And see not ye yon braid braid road.

Save where the immortals in their That lies across yon lilly lcven

exultation, [glade, lawn]?

Moon-led, their holy hills forever That is the path of wickedness,

roam?

Tho some call it the road to

heaven.

What is to me your sanctity, grave

clothed in white. "And see not ye that bonny road.

Cold as an altar, pale as altar Which winds about the fernie

candle light? brae Chillsidel?

This content downloaded from

35.146.198.8 on Wed, 04 Oct 2023 12:24:54 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MYTHLORE 31: Spring 1982 page 16

That is the road to fair Elfland, image." But the Queen's rejection of

Whel'rel you and I this night Christianity is final, and she is allowed to

maum gae." have her will. That emphatic "No" at the end

Lewis combines this with another motif— of the line shows her clear decision; a

the eating of supernatural food which keeps refusal of the Christian position with a full

the mortal (or immortal, for that matter) in understanding of the implications.

the supernatural realm. The most widely known The Archbishop, in his speech to the Queen

use of this motif in the West is the myth of in Canto V, mentions a danger in her choice:

Persephone. Here the elf gives the food to 'Daughter, turn back, have pity yet

the Queen:

upon yourself .,.

'Eat, eat' he gave her of the Go not to the unwintering land where

loaves of faerie. they who dwell

•Eat the brave honey of bees no man Pay each tenth year the tenth soul

enslaveth.' of their tribe to Hell.'

(p. 172, 11. 201-2) (p. 174, 11. 256-8)

And later the reader is told, "She has tasted And this motif is repeated at the end of the

elven bread" (p. 175, 1. 290) . Just as, in poem:

"Thomas Rymer," Thomas tastes the bread which

the Elvish Queen carries: And so, the story tells, she passed

away

"But. I have a loaf here in my lap. Out of the world: but if she dreams

Likewise a bottle of claret wine. to-day

And now ere we go farther on, In fairy land, or if she wakes in

We'll rest a while, and ye may Hell,

dine." (The chance being one in ten) it

Presumably, as with Persephone, once Thomas doesn't tell.

and the Queen of Drum have eaten of the super (p. 175, 11. 291-4)

natural food, they are tied to elfland— The source is again a Scottish ballad—this

although, for Thomas, the binding only lasts time "Tam Lin" (Child Ballad No. 39); in the

seven years. ballad Tam tells his lover, Janet:

I mentioned the Archbishop in the summary "... pleasant is the fairyland,

and his ghostly reappearance at the end of the But, an eerie tale to tell,

poem, urging the Queen to choose the path to Ay at the end of seven years

Heaven instead of that to Faeryland. The We pay a tiend Ctax, titheJ

Queen, after the urging of the elf, is at the to hell;

moment of decision of which of the three paths I am sae fair and fu o flesh,

to take. She feels as if she is being pulled I'm feard it be mysel."

apart:

The reason that Tam is "full of flesh" is that

Yet to the sagging torment of that he is a human who has been taken by the elves;

dissolution presumably they prefer to pay over humans

She clung, contented with the rather than their own kind (an unquieting

vanishing thought for the Queen of Drum, but in Lewis's

If only the fear'd moment never poem she seems to have the same odds as the

would arise elvish born). Why Lewis shifted the seventh

Of being commanded to lift up her year to the tenth year is not certain;

eyes possibly to reinforce the idea of the tithe,

And to see that whose dissimilitude possibly for the rhythm and parallelism of

To all things should, in the first the line.

stare

Of its aloofness, make the world What, then, is a reader to make of Lewis's

despair. ballad-haunted narrativ.e? Obviously Lewis does

(p. 173, 11. 232-8) not see Sehnsucht as leading to God, as he

will in Pilgrim's Regress and Surprised by Joy.

In other words, she fears to see God's face. In light of his earlier poems, one would tend

The Archbishop's face she sees instead, and to identify Lewis with the Oueen; in light of

he urges her the traditional repentance, which his later Christian essays, with the Arch

she rejects: bishop. Probably it is safest to say that

'You would not see if you looked up Lewis in "The Queen of Drum" projects the

out of your torment Romanticism of his youth against his new-found

That face—only the fringes of His Christianity, not in the sense that he had

outer garment ... found them at odds ultimately, but as a

Run to it, daughter; kiss that hem.' projection of what he had felt during his years

She answered, 'No. of atheistic Romanticism. This, of course,

If you are with Him pray to Him that is reading the poem in the authorial terms

He may go. which Lewis disparages in The Personal Heresy.

Or pray that He may rend and tear But it would just as easy to read the poem in

me. terms of the history of ideas: the Queen of

But go, go hence and not be near Drum stands for the type of nineteenth-century

me.' (p. 174, 11. 263-8) Romanticism found in Shelley's "Hymn to

Intellectual Beauty" and the Archbishop for

The Archbishop's appearance here is as what the traditional, orthodox, supernatural

Charles Williams later called "a God-bearing Christianity. Or it would be possible to read

This content downloaded from

35.146.198.8 on Wed, 04 Oct 2023 12:24:54 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MYTHLORE 31: Spring 1982 page 17

the poem in terms of personality types: the elf or faerie—and it is probably no error

dreamer vs. the moralist, both projected in both of these are the woid elf. In "The Day

terms of the supernatural. Lewis later, in with a White Mark" (1949) Lewis describes an

The Great Divorce, will again picture souls extremely happy day and asks what caused it:

being urged to seek salvation and (all but "Was it an elf in the blood? or a bird in the

one) refusing it: but never again will he brain?" (1. 2; see also 1. 23).

show so clearly one who denies God for the sake

of an alternate ideal, and who does it (while This is making an elf psychological in

with some fears) with such a clarity of the extreme! But it does not seem to be taking

understanding of what she is refusing. elves very seriously qua elves. Again in an

epitaph (No. 13), Lewis describes a woman who

However one considers it, "The Oueen of on the Day of Judgment will be startled to see

Drum" is an odd work in Lewis's career. Never her virtuous speech praised; Lewis describes

again will he admit a third pathway: all roads the woman

hereafter will lead to Heaven or Hell; Lewis with her old woodland air

is a great writer for making sharp distinctions.

But somehow, in this poem, he was moved to (That startled, yet unflinching stare,

follow the model of a ballad: "And see not Half elf, half squirrel, all surprise).

ye that bonny road, / Which winds about the This may be even worse than the former, for the

fernie brae?" Only for a moment is it parallelism with the squirrel suggests Lewis

visible. Even the name of the country—Drum— in thinking of the small, diminutive elves of

is unexplained. Perhaps Drum suggests that literary tradition—and, it must be admitted,

just under the surface of the world—under the of some folk tradition. But it is more cute

drumhead—lies dark, resonating mysteries? than dangerous.

(Host people are content with surface know

ledge.) Or did Lewis pick it because of its Therefore, when we see what Lewis made

consonance with dream? Let me conclude by of faeryland early and his near suppression of

printing the passage in which the faery lord it later, outside of scholarly writings, we can

appears to the Queen: I will stress the only conclude that the suppression was deliber

internal rhymes in the lines with underlining, ate. He could encourage Tolkien who knew much

thus somewhat distorting them; but these many about that land, but surely Lewis decided that

internal rhymes, with enjambment, tend to for himself, faeryland was too dangerous for

make the ear lose the line pattern in the further visits. His Romantic blood could not

welter of echoing sounds anyway—which was be trusted within the edges of that place.

presumably Lewis's intention, since he does Instead, he would create his own realms—

not rhyme the lines, using only feminine Malacandra, Perelandra, Naraia—perhaps some

endings to them: what like to but never to be identified with

faerie; he would not take that third road again.

And lo! it was a horse and rider, His dance with the faerie was over.

Breathing, unmoving, close beside

her... Footnotes

More beautiful and larger

Than earthly beast, that charger. Tnis introduction was written for Mythcon,

Where rode the proudest rider; but it was cut at the last minute. I had

—Rich his arms, bewitching only forty-five minutes for my paper, and in

His air—a wilful, elfin revising the paper in the airplane on the way

Emperor, proud of temper, to California and in spare minutes (usually late

In mail of eldest moulding at night) at Mythcon before it was read on

And sword of elven~silver, Monday morning, Mythcon XII's last day, I had

Smiling to bequile her. . . .(11. filled up ray time.

m-9i) 2

Dull and scholarly papers always have many

Whatever we say about Lewis's intentions in footnotes. In this case, cf. the opening to

this poem, his verse shows the emotional appeal Lewis's "The Inner Ring."

of the faerie.

3The Rambler, Everyman Library, No. 994,

V. Afterwords 1953, p. 98.

I have reached and now have passed the 4

In this line—"without a peer"—a punning

high point of my paper. But a legitimate explanation of why Lewis does not address the

question remains: what does Lewis do after

wards about faerie? We now have him converted. envoy to a "lord" (one of the two meanings of

He has used faerie as a symbol of Romantic peer) as is traditional? It sounds like the

Longing for many years, even through "The

cleverness a young poet might appreciate.

Queen of Drum"; he has tried to Christianize

the !faerie people in "The Nameless Isle." 5It is true that the poems in the third

As We know, in such books as The Pilgrim's section of Spirits in Bondage tend to be more

Regress and Surprised by Joy, Lewis shifts from orthodox than those xn the first section; but,

the three-fold path of "The Queen of Drum" and unless Lewis being completely hypocritical in

says that such longing leads to God, ultimately. the last section—writing poems to project a

But surely faeries make poor symbols of God. false, more traditional image of his beliefs—

they must reflect some vagrant moods of ortho

The answer to my rhetorical auestion, so doxy in his attitudes of the time.

far as Lewis's poetry is concerned, is that

Lewis drops faerie from his poetry. In reading ®The island in the poem, left by the

through Poems (1964), I find only two uses of continued on page 47

This content downloaded from

35.146.198.8 on Wed, 04 Oct 2023 12:24:54 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

This content downloaded from

35.146.198.8 on Wed, 04 Oct 2023 12:24:54 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MYTHLORE 31: Spring 1982 page 47

Horn's, Kenneth by Joe R. Christopher)

11. Finder of the Welsh Gods (Dainis Bisenieks) (note in

Mythlore 12) Vergil

20. The Influence of Vergil's Aenid on The Lord of the

Morris, William Rings (David Paul Pace)

13. Golden Wings and Other Stories (reviewed by George

Colvin) Wain, John

18. How the Isle of Ransom Reflects an Actual Icelandic 15. Feng: A Poem (reviewed by Joe R. Christopher)

Setting (Mara Hasty) (sources of The Glittering

Plaint Watts-Dunton, Theodore

21. William Morris' The Wood \Beyond the World: The Vic 25. Cavalier Treatment (Lee Speth) (Aylwin)

torian World vs. the Mythic Eternities (Clarence

Wolfshohl) Wells, H.G.

30. Worlds Beyond the World by Richard Mathews (reviewed 24. Lewis' Time Machine and His Trip to the Moon (Rabert E.

by Nancy-Lou Patterson) Boeing) (The Time Machine and The First Men in the Moon^

Peake, Mervyn White, T.H.

20. Cavalier Treatment (Lee Speth) (Titus Groan) 16. Images of the Numinous in T.H. White and C.S. Lewis

30. "Felicitous Space" in the Fantasies of George Mac (Ed Chapman) (The Once and Future King)

Donald and Mervyn Peake (Anita Moss) 24. T.H. white by John K. Crane (reviewed by Joe R. Chris

Pearl topher)

18. Levels of Symbolic Meaning in Pearl (Laurence J. Krieg) 28. Bird Language in T.H. White's The Sword in the Stone

(Marie Nelson)

Pennington, Bruce

19. Eschatus (reviewed by Robert S. Ellwood) Worlds of Fantasy (magazine)

1. Introduction to Worlds of Fantasy (Bernie Zuber)

Rico, U1 de

24. The Rainbow Goblins (reviewed by Nancy-Lou Patterson) ALL BACK ISSUES OF MYTHLORE

Sayers, Dorothy L. ARE AVAILABLE

12. The Emperor Constantine: A Chronicle (reviewed by If you wish to order back issues, you can use the form

George Colvin)

included in the mailing of this issue, or you can request

13. Dorothy L. Sayers and the Inklings (Joe R. Christopher) an order form which is free upon request.

14. Adventure, Mystery, and Romance by John G. Cawelti

(reviewed by Joe R. Christopher)

14. Encyclopedia of Mystery and Detection edited by Chris

Steinbrunner and Otto Penzler (reviewed by Joe R.

Christopher)

17. Trying to Capture "White Magic" (Joe R. Christopher)

(on poem, "white Magic" Meditation I

19. Wilkie Collins: A Critical and Biographical Study (re

viewed by Joe R. Christopher) For my Lady of Grace

21. Head vs. Heart in Dorothy L. Sayers' Gaudy Night (Marg

aret P. Hannay)

21. The whimsical Christian (reviewed by Nancy-Lou Patterson) I closed my eyes. 0 let me no more fight

21. Maker and Craftsman: The Story of Dorothy L. Sayers by But seek within a dwelling-place of Light.

Alzina Stone Dale (reviewed by Nancy-Lou Patterson)

bright

And lo! my Lady came in form so bricrht

22. As Her Whimsey Took Her: Critical Essays on the Work of

Mv inward eve was dazzled. 0 that I might

Dorothy L. Sayers edited by Margaret P. Hannay (re Sing

Sina forth

forth my

my joy

joy in

in words

words of

of wonder

wonder quite

quite

viewed by Nancy-Lou Patterson) As fair as ever ooet sane in height

22. Dorothy Sayers: A Literary Biography by Ralph E. Hone Of soaring praise, and kneel her humble knieht

knight

(reviewed by Nancy-Lou Patterson) Content to rest, made eentle

gentle in

in her

her sight.

sight.

22. The Repose of Very Delicate Balance (William R. my flawless Oueen

Epperson (marriage in Sayers' detective fiction)

But I stood dumb before mv

Like one who waits the .Iudcment

judgment ofof his

his lord

lord

27. Dorothy L. Sayers, A Pilgrim Soul by Nancy M. She sDOke

spoke no

no word,

word, but

but smiling

smiling took

took my

my hand

hand

Tischler (reviewed by Nancy-Lou Patterson) And led me out into a timeless land...

28. Dorothy L. Sayers: Nine Literary Studies by Trevor 'Tis words I lack, not love for my Adored

H. Hall (reviewed by Nancy-Lou Patterson) Wherewith to tell what these closed eyes have seen.

29. Dorothy L. Sayers by Mary Brian Durkin (reviewed by

Nancy-Lou Patterson)

30. Dorothy L. Sayers by James Brabazon (reviewed by —Mark Allaby

—Hark Allaby

Nancy-Lou Patterson)

Shakespeare, William

21. Cavalier Treatment (Lee Speth) (Macbeth) continued from page 17

24. Cavalier .Treatment (Lee Speth) (Macbeth)

narrator, the heroine, and the elf-with-wings, is called

Spenser, Edmund "Elf-fair" (1. 726)

3. Tolkien § Spenser (Nan Braude) (The Fairie Queene)

7Walter Hooper,

^Walter Hooper, in

in his

his preface

preface to

to Narrative

Narrative Poems,

Poems, says

says

Spielberg, Steven

the poem was written in the 1929-1931 period (p. xi).

29. Raiders of the Lost Ark (reviewed by Benjamin Urrutia)

®At Mythcon the movie based on "Tarn Lin" was shown

Swann, Thomas Burnett

and of course one of Dr. Elizabeth Pope's novels — The

11. The Not-World (reviewed by Ed Chapman) Perilous Gard— was based on the ballad.

Torrens, R.G. ^Edmund Spenser in The Kaeric Queene

9Edmund Spenser in Theturned elves

Kaerif Quoene turned into

elves into

13. The Secret Rituals of the Golden Dawn and The Golden moral beings,

moral beings,

but theybutended

thoyup ended

beingupmuch

beinglikemuchhuman.

like human.

Dawn: The Inner Teachings (reviewed by Joe R. Christ- (Who(Whowouldwould

thinkthink

of Sir

of Guyon

Sir Guyon

as anaself

an ?)elf?)

Spenser

Sponsormaymayjustjust

opher) have indentified the Welsh and the elves. Hut it should have

have indentified the Welsh and the elves. Hut it should have

been possible in the lianaissance,

Kanaissance, which could use Jupiter

Underhill, Evelyn as a symbol of Jehovah, to use Oberon the same way. Per

as a symbol of .lehovah, to use Obcron the same way. Per

13. Evelyn Underhill (1S75-1941): An Introduction to Her Life haps,

haps,

for for

the the

English,

English,

the the

faeries

faeries

werewere

closercloser

to live

to li'/e

pa enpaean

n

and Writings by Christopher J.R. Armstrong (revioKC.1 beliefbelief than

than thethe lioman

Roman deities

deities were.

were.

This content downloaded from

35.146.198.8 on Wed, 04 Oct 2023 12:24:54 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- The Goblin UniverseDocument89 pagesThe Goblin UniverseAnonymous T2wwuxkEfC94% (18)

- Thesis Statement About EarthquakesDocument5 pagesThesis Statement About Earthquakesmiamaloneatlanta100% (2)

- Lewis Nkosi Mating Birds PDFDocument71 pagesLewis Nkosi Mating Birds PDFIsis Cordoba100% (1)

- Lit. Guide - The Lion, The Witch & The Wardrobe PDFDocument16 pagesLit. Guide - The Lion, The Witch & The Wardrobe PDFGaurav100% (3)

- Mc12-Christopher-Ld Converted-PiDocument16 pagesMc12-Christopher-Ld Converted-Piapi-330408224No ratings yet

- The Call of Cthulhu!Document22 pagesThe Call of Cthulhu!ManuelaNo ratings yet

- CoC - Adv - LozdraDocument12 pagesCoC - Adv - LozdraClaudio GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Lovecraft Library, Vol. 2: The Call of Cthulhu and Other Mythos Tales PreviewDocument10 pagesLovecraft Library, Vol. 2: The Call of Cthulhu and Other Mythos Tales PreviewGraphic Policy60% (5)

- Horror Classics. Illustrated: H.P. Lovecraft - The Call of Chtulhu, Edgar Allan Poe - The Fall of the House of UsherFrom EverandHorror Classics. Illustrated: H.P. Lovecraft - The Call of Chtulhu, Edgar Allan Poe - The Fall of the House of UsherNo ratings yet

- Rosalind's Siblings: Fiction and Poetry Celebrating Scientists of Marginalized GendersFrom EverandRosalind's Siblings: Fiction and Poetry Celebrating Scientists of Marginalized GendersNo ratings yet

- The Call of CthulhuDocument22 pagesThe Call of Cthulhudarketernal8No ratings yet

- Tales from the Annexe: Seven Stories from the Herbert West Series and Seven Other TalesFrom EverandTales from the Annexe: Seven Stories from the Herbert West Series and Seven Other TalesNo ratings yet

- Board of Regents of The University of Oklahoma World Literature TodayDocument3 pagesBoard of Regents of The University of Oklahoma World Literature Todayadmane memNo ratings yet

- Board of Regents of The University of Oklahoma World Literature TodayDocument3 pagesBoard of Regents of The University of Oklahoma World Literature Todayadmane memNo ratings yet

- The Call of CthulhuDocument44 pagesThe Call of CthulhuBeata GawliczekNo ratings yet

- The Call of CthulhuDocument14 pagesThe Call of CthulhuLOKADNo ratings yet

- Lovecraft - The Call of CthulhuDocument42 pagesLovecraft - The Call of CthulhuCelephaïs Press / Unspeakable Press (Leng)100% (10)

- Howard Phillips Lovecraft - The Call of CthulhuDocument34 pagesHoward Phillips Lovecraft - The Call of CthulhuRafael TiconNo ratings yet

- Howard Phillips Lovecraft - The Call of CthulhuDocument34 pagesHoward Phillips Lovecraft - The Call of CthulhucaptaingreythewolfNo ratings yet

- Call of CthuluDocument19 pagesCall of CthuluKarlibirisssNo ratings yet

- The Call of CthulhuDocument21 pagesThe Call of CthulhuEnienaNo ratings yet

- The Call of CthulhuDocument30 pagesThe Call of CthulhuHéctor RojoNo ratings yet

- The Call of Cthulhu: by H. P. LovecraftDocument27 pagesThe Call of Cthulhu: by H. P. LovecraftPabloHeroBrianLopezCardenasNo ratings yet

- The Call of CthulhuDocument24 pagesThe Call of CthulhuAnn Cook100% (3)

- The Call of CthulhuDocument22 pagesThe Call of Cthulhustefan heNo ratings yet

- Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow - and Other Essays - Aldous Huxley - 2019 - Anna's ArchiveDocument326 pagesTomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow - and Other Essays - Aldous Huxley - 2019 - Anna's ArchiveCinler PerilerNo ratings yet

- Call of CthuluDocument42 pagesCall of Cthulusuhel pal100% (1)

- The Call of Cthulhu: by H. P. LovecraftDocument27 pagesThe Call of Cthulhu: by H. P. LovecraftEran SegalNo ratings yet

- The Call of Cthulhu: by H. P. LovecraftDocument27 pagesThe Call of Cthulhu: by H. P. LovecraftEran SegalNo ratings yet

- The Call of CthulhuDocument15 pagesThe Call of CthulhuCerrüter LaudeNo ratings yet

- Folklore Volume 105 Issue 1994 (Doi 10.2307/1260657) Review by - Jacqueline Simpson - (Untitled)Document3 pagesFolklore Volume 105 Issue 1994 (Doi 10.2307/1260657) Review by - Jacqueline Simpson - (Untitled)Mario Richard SandlerNo ratings yet

- The Call of Cthulhu HP LovecraftDocument32 pagesThe Call of Cthulhu HP LovecraftraulNo ratings yet

- The Call of Cthulhu: With a Dedication by George Henry WeissFrom EverandThe Call of Cthulhu: With a Dedication by George Henry WeissRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (58)

- Patterns of Creativity: S. Chandrasekhar Look For These Expressions and Guess The Meaning From The ContextDocument8 pagesPatterns of Creativity: S. Chandrasekhar Look For These Expressions and Guess The Meaning From The ContextGod is every whereNo ratings yet

- The Eternal Return: Oedipus, The Tempest, Forbidden Planet: Tales of the Mythic World, #2From EverandThe Eternal Return: Oedipus, The Tempest, Forbidden Planet: Tales of the Mythic World, #2No ratings yet

- DeconstructionDocument27 pagesDeconstructionLn VedanayagamNo ratings yet

- Howard Phillips Lovecraft - The Call of CthulhuDocument34 pagesHoward Phillips Lovecraft - The Call of CthulhuCarlos GuerreroNo ratings yet

- Braid Yorkshire - The Language of MythDocument7 pagesBraid Yorkshire - The Language of MythVlad Adrian GhitaNo ratings yet

- DNB FuturismDocument11 pagesDNB FuturismbenarbiashaheenNo ratings yet

- The Call of CthulhuDocument25 pagesThe Call of CthulhuMyrdred The DeceiverNo ratings yet

- Howard Phillips Lovecraft - The Call of CthulhuDocument35 pagesHoward Phillips Lovecraft - The Call of CthulhuellasaroNo ratings yet

- Arcadia: A Play On ComplexityDocument7 pagesArcadia: A Play On ComplexityPaul SchumannNo ratings yet

- H P Lovecraft - Essential Guide To CthulhuDocument325 pagesH P Lovecraft - Essential Guide To Cthulhuy'Oni Xeperel67% (3)

- The Call of Cthulhu and At the Mountains of Madness: Two Tales of the MythosFrom EverandThe Call of Cthulhu and At the Mountains of Madness: Two Tales of the MythosRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Call of CthulhuDocument26 pagesThe Call of CthulhuLeigh SmithNo ratings yet

- Washing Machine: Service ManualDocument59 pagesWashing Machine: Service ManualHama AieaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Characteristics of ResearchDocument1 pageChapter 1 Characteristics of ResearchPrincess Nicole ManagbanagNo ratings yet

- Forensic AccountingDocument29 pagesForensic AccountingBharath ChootyNo ratings yet

- By Sin I Rise Part Two Sins - Cora ReillyDocument237 pagesBy Sin I Rise Part Two Sins - Cora ReillyNour Al-khatib50% (2)

- Trail Smelter ArbitrationDocument33 pagesTrail Smelter ArbitrationpraharshithaNo ratings yet

- Elena Rodriguez Reflective EssayDocument1 pageElena Rodriguez Reflective EssayElena Rodriguez ZuletaNo ratings yet

- Mitsubishi Industrial Robot F SeriesDocument22 pagesMitsubishi Industrial Robot F SeriesNaimersoft SolucionesNo ratings yet

- Travel Motivations and State of DevelopmentDocument6 pagesTravel Motivations and State of Developmentphuong anh phamNo ratings yet

- Risk Managemennt Chapter 4 - PC - 2022Document39 pagesRisk Managemennt Chapter 4 - PC - 2022sufimahamad270No ratings yet

- The Geology of The Panama-Chocó Arc: Stewart D. RedwoodDocument32 pagesThe Geology of The Panama-Chocó Arc: Stewart D. RedwoodFelipe ArrublaNo ratings yet

- Design and Fabrication of A Blanking Tool: Gopi Krishnan. C (30408114309) (30408114092)Document44 pagesDesign and Fabrication of A Blanking Tool: Gopi Krishnan. C (30408114309) (30408114092)Daniel Saldaña ANo ratings yet

- Social Science All in One (Preli)Document363 pagesSocial Science All in One (Preli)Safa AbcNo ratings yet

- A Sound of Thunder - Reading Response ADocument3 pagesA Sound of Thunder - Reading Response AAhsan HomarNo ratings yet

- ELEKTROLISISDocument3 pagesELEKTROLISISrazhafiraahNo ratings yet

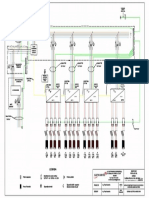

- SCHEMA MONOFILARA PIPEPLAST - CompletDocument1 pageSCHEMA MONOFILARA PIPEPLAST - Completmihai oproescu100% (1)

- Conference Board of The Mathematical SciencesDocument43 pagesConference Board of The Mathematical Sciencesjhicks_mathNo ratings yet

- Necromancer Bone Spear Build With Masquerade (Patch 2.6.10 Season 22) - Diablo 3 - Icy Veins 3Document1 pageNecromancer Bone Spear Build With Masquerade (Patch 2.6.10 Season 22) - Diablo 3 - Icy Veins 3filipNo ratings yet

- Enhancing Efficiency and Reliability: Automation of Oil Desalination and Dehydration ProcessDocument14 pagesEnhancing Efficiency and Reliability: Automation of Oil Desalination and Dehydration ProcessYunusov ZiyodulloNo ratings yet

- MG-RTX3 ManualDocument2 pagesMG-RTX3 ManualAJ EmandienNo ratings yet

- ARA 111 (PREPARATORY ARABIC) - First Sem 2021Document15 pagesARA 111 (PREPARATORY ARABIC) - First Sem 2021Mohaimen GuroNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Decision Making Using Cost Concepts and CVP AnalysisDocument208 pagesChapter 2 Decision Making Using Cost Concepts and CVP AnalysisJyotika KhareNo ratings yet

- Security Guard Training & OSHA Training NY Guardian Group ServicesDocument1 pageSecurity Guard Training & OSHA Training NY Guardian Group ServicesLochard BaptisteNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Project Management The Key To Achieving ResultsDocument40 pagesChapter 1 Project Management The Key To Achieving Resultslyster badenasNo ratings yet

- Scott Meech Etec 500 Journal AssignmentDocument7 pagesScott Meech Etec 500 Journal Assignmentapi-373684092No ratings yet

- Galcon Manual UsuarioDocument65 pagesGalcon Manual Usuariopedro1981No ratings yet

- Analysis of Portal FrameDocument16 pagesAnalysis of Portal FrameKanchana RandallNo ratings yet

- General Bearing Requirements and Design CriteriaDocument6 pagesGeneral Bearing Requirements and Design Criteriaapi-3701567100% (2)

- All India Test Series: Concept Recapitulation Test - IDocument12 pagesAll India Test Series: Concept Recapitulation Test - IShreya DesaiNo ratings yet