Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Why Do Farmers Commit Suicide

Why Do Farmers Commit Suicide

Uploaded by

meenakshimanojkOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Why Do Farmers Commit Suicide

Why Do Farmers Commit Suicide

Uploaded by

meenakshimanojkCopyright:

Available Formats

Why Do Farmers Commit Suicide?

The Case of Andhra Pradesh

Individuals and communities are under pressure to cope with the changes brought about

by a churn in socio-economic conditions. The policies associated with the process

of economic liberalisation have imposed a stress on the peasantry leading to suicides. The

tragic developments in rural Andhra Pradesh should compel us to draw

important lessons for India’s agrarian economy.

V SRIDHAR

T

he summer of 2004 was an unprecedented one for rural there had been no attempt – either by the English language press

Andhra Pradesh, even by the dubious standards estab- or the local media – to collate and analyse the information at

lished in the last two decades when the number of suicides a broader level to highlight the issues at stake.

by peasants had risen alarmingly. In a short span of less than However, the most plausible reason for the spate of suicides

two months, between May and July 2004, more than 400 peasants appears to be related to the fact that farmers were at that time

in the state committed suicide. Although peasant suicides have engaged in the task of planning their next crop. May and June

repeatedly occurred in the state in the past, the significance of are months when they prepare for sowing the kharif crop in late

this round of deaths lay in the fact that they were reported from June and July, when the monsoon arrives in most parts of the

every single district in the state, barring Hyderabad. state. Those sympathetic to the plight of the farmers argued that

Blaming “drought”, the favourite explanation of do-nothing small and marginal farmers across the state had reached the end

politicians, simply failed to explain the tragic phenomenon. The of the road. Unable to clear their existing loans or to get fresh

fact that suicides were reported literally from every corner of loans for the next season, and seeing no hope on the horizon

the state (Table 1), in particular, from even the better irrigated they took their lives, they say.

districts, exposed the argument that the scarcity of water, depicted What explains the phenomenon of a sharp increase in the

in a vague and generally deceptive sense, was responsible for incidence of suicide among the peasantry? The consensus among

farmers committing suicide. Instead, the stunning sweep of death psychiatrists and social scientists who have explored the phe-

across the state brought to the fore all that is wrong in the lives nomenon is that a substantial “dislocation” of livelihoods drives

of the peasantry. a community to despair and eventually suicide. Although the

Death hit farmers in varying agro-climatic zones. Unlike the phenomenon of suicide is a deeply personal and individual act,

rounds of suicides in 1987-88, 1997-98 and 2000, when peasants suicidal behaviour is determined by a confluence of factors. These

growing particular crops such as tobacco, cotton, chillies and are basically in two domains. One, the internal domain, relates

groundnut died, in 2004 death stalked everywhere. No crop was to factors which operate at the level of the individual. The other

exempted and no section of the small peasantry appeared insu- is external, which suggests that larger social processes determine

lated. The overwhelming proportion of the death toll was among suicidal behaviour. It places emphasis on broader society-level

small and marginal farmers and tenant cultivators, who had no changes, as being responsible for deaths by suicide. The reasoning

claim on the land they cultivated and who paid exorbitant rents is that individuals, unable to cope with the social churn in which

to landlords. they find themselves, resort to suicide. Of course, this is accen-

What explains the unprecedented number of suicides in such tuated when such a churn is also accompanied by widespread

a short duration? Several theories floated in Hyderabad. The economic distress.

theory popular among sections of bureaucrats, politicians and The evolution of the modern understanding of suicides and

the intelligentsia was that the peasants committed suicide because suicidal behaviour has been to marry the externalised and the

of the assistance package announced on the eve of elections by internalised views. Diego De Leo, psychiatrist and former presi-

the then chief minister N Chandrababu Naidu, who hitherto dent of the International Association for Suicide Prevention

steadfastly clung to the notion that a relief package for victims (IASP), explains that this understanding has come a long way

would spur more farmers to their death. On June 2, 2004 the from the early 19th century view that equated suicidal behaviour

previous chief minister remarked that the “unusual spurt” in the with insanity. Two concomitant revolutions in the late 19th

number of suicides after Rajasekhara Reddy assumed office was century – one in the field of sociology, associated with Emile

because of the package. Durkheim (1951), and the other, the psychoanalytical movement

Another explanation was that it was simply because the media, led by Sigmund Freud, have been synthesised in the modern view

particularly the Telugu language press, was reporting such deaths of suicide and suicidal behaviour.

in a much more systematic manner than before. Some Telugu The phenomenon of suicide is therefore widely regarded to

papers listed the number of suicides in their district editions. be a result of individuals’ inability to cope with sudden and

Media observers pointed out that the coverage by the Telugu cataclysmic changes in socio-economic conditions. It is not

media was much better when compared to earlier rounds of such without significance that the highest suicide rates are those

deaths. In fact, observers noted that even the English dailies prevailing in the countries of the erstwhile Soviet Union, where

published from state reported the deaths in a more systematic calamitous changes in living conditions have occurred in the last

fashion than in the past. However, media critics also noted that decade and more.

Economic and Political Weekly April 22, 2006 1559

The phenomenon of the widespread incidence of suicides Millets and other inferior cereals have given way to oilseeds,

among peasants in India is of fairly recent vintage – certainly cotton and chillies. This shift has obvious implications for the

not more than two decades. Although Andhra Pradesh is the leader peasantry. Non-food crops imply a greater extent of dependence

of sorts in this respect, the phenomenon is by no means confined on cash incomes not only for cultivation but also for self-

to that state alone. Suicides by peasants have been reported from consumption. The greater dependence on monetised inputs, such

Karnataka, Maharashtra, Kerala, Punjab, Rajasthan, Orissa, as seeds, fertilisers and pesticides also meant increased recourse

Madhya Pradesh, among several other states of the Indian union. to borrowings. Very often the source of credit was also either

Crucially, if it is accepted that the phenomenon of suicides is a supplier of inputs or a landlord who leased out his land to the

driven by dramatic changes in socio-economic conditions, then cultivator. The cash borrowings ensured further integration into

one has to examine what in the lives of the peasants has changed the cash economy because the peasant had to repay the cash loans

so dramatically in the last two decades as to have pushed them which commanded usurious rates of interest. This shift also

to take their own lives. ensured that the peasant could not get back to the earlier situation

While it is foolhardy to pin a single factor as causing peasants of growing subsistence crop, the market for which may also have

to take their own lives, it is becoming clear that the set of policies collapsed in the new situation of a cash-governed crop economy.

unleashed by economic liberalisation in the last decade have The agrarian crisis is reflected by the declining growth rate

played a significant role. The fact that Andhra Pradesh has been, of agricultural output in Andhra Pradesh. The rate of growth of

until recently, a leader in this respect among all the states of the agricultural output declined from 3.4 per cent per annum in the

Indian union, is also not without significance. 1980s to 2.3 per cent per annum in the 1990s. Moreover, agri-

cultural crop yields also grew at a slower pace. For instance, the

Background growth rates of rice yields declined from an annual rate of 3.1

per cent in the 1980s to 1.3 per cent in the 1990s; similarly, cotton

The rural economy in Andhra Pradesh is in the throes of a severe yields also slackened, the figures being were 3.4 per cent and

crisis. Although the drought-hit regions of Rayalaseema and 1.4 per cent, respectively in the two decades. Nationwide studies

Telangana have borne a greater part of the strain of the crisis, estimate that crop yields in the state declined by 1.8 per cent

it is evident that even farmers in the irrigated tracts have not been per year over the 1990s. In addition, the volatility in yields

spared. Moreover, small and marginal farmers, tenant cultivators was also greater in the 1990s, implying a greater instability in

and agricultural workers have borne most of the burden of the agricultural performance.

crisis. Suicides by peasants are only the last step of desperation, The peasantry’s travails due to the declining agricultural

apparently driven by the growing burden of debt. However, this performance could have been offset by better and stable prices.

does not reveal the fact that agricultural activity has not only become However, the prices of crops produced by farmers in Andhra

more unstable and unviable for large sections of the peasants. Pradesh have become much more volatile. This is as much due

Indeed, the failure of the state to act despite repeated media to the failure of state intervention in the product market as the

exposures of kidney sales or of starvation deaths by desperate increasing tendency to be governed by trends in the global

peasants is only indication of the manner in which the state has commodity markets. It has been suggested that since 1996, falling

ignored warning signals of desperation from the peasants. international primary commodity prices of many crops impacted

Frequent droughts, although a significant feature in Rayalaseema Indian markets in India even when the actual volume of imports

and Telangana, is only one aspect of the problem. Soil degradation

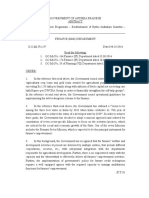

and inappropriate agricultural practices; rising cost of inputs; wild Table 1: Suicides by Peasants in Andhra Pradesh –

fluctuations in farm output prices; and rising indebtedness are May 14-July 9, 2004

other aspects of the problem. Indebtedness, in a desperate situation, District/Region Toll

is the proverbial last straw on the back of the peasantry. Indebted-

ness, often described as the proximate cause of suicide, is only Coastal Andhra 121

Nellore 21

symptomatic of the larger malaise that afflicts agriculture and its Prakasam 13

practice in the state. Case studies of suicide victims reveal these Guntur 36

multiple facets of the problem (see Appendix for one such case study). Krishna 18

The general deterioration of conditions in which the peasant West Godavari 15

practices agriculture has been accentuated by the withdrawal of East Godavari 11

Visakhapatnam 3

institutional support for activities that are essential to agriculture. Vizianagaram 2

Conversely, this has meant that the peasant has been forced to Srikakulam 2

seek private sources to provide these support services. For in- Rayalaseema 85

stance, the decline of institutional credit and adequate insurance Chittoor 18

has meant that the peasant has had to depend on moneylenders Cuddapah 14

Anantapur 30

for their credit needs. There are also indications that the market Kurnool 23

for credit, land and inputs are getting more integrated, implying Telangana 222

a greater squeeze on the peasantry. The agrarian crisis has been Mahbubnagar 27

accentuated by stagnant employment; while agricultural employ- Rangareddy 10

ment has declined, opportunities for off-farm employment have Nizamabad 28

Nalgonda 31

also been stagnant. This is reflected in not only a decline in Medak 32

consumption but also increasing migration. Adilabad 13

The shift in cropping pattern, as can be seen from Table 2, Karimnagar 37

indicates an apparent dynamism in agricultural performance in Warangal 27

Andhra Pradesh. It is evident that peasants across the state have Khammam 17

Total 428

shifted away from traditional rain-fed cereal crops to non-food

cash crops. Much of the shift has occurred in the recent past. Source: Andhra Pradesh Rythu Sangham.

1560 Economic and Political Weekly April 22, 2006

did not increase. The mere possibility of such imports, it has been Congress government in Andhra Pradesh has initiated a series

suggested, has dampened commodity prices in Indian markets of measures to stem the tide of suicides in the state (and, it appears

[Patnaik 2004: 22-26]. Moreover, prices have not only fallen, to have halted the march of death at least temporarily), the failure

they have tended to be more volatile. This is particularly true to recalibrate policy at the national level may have the effect

of crops such as cotton and groundnut. In short, prices have of neutralising these measures.

proved to be uncertain and undependable. Here we need only recount those aspects of the liberal regime

It is evident from Table 3 that agriculture is in serious danger which have a bearing on the way agriculture is practised, and

of being a loss-making proposition for most peasants in the state. its consequences for the peasantry. It has worked in two ways.

Returns from agriculture are either stagnant or in decline for many First, it has worked on the logic of “freeing” agricultural product

crops. In addition, returns are also volatile, reflecting the volatility markets, based on the argument that this would only be beneficial

in the prices of agricultural produce. Data from the Commission to farmers. This has been crucially located in the logic of aligning

on Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) show that the returns Indian agricultural product prices to those prevailing globally.

from cotton cultivation per hectare in current prices were, in fact, This rationale has been that this is required as part of its com-

negative in 1996-97 (implying a loss of Rs 1,641 per hectare mitments made to the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

for peasants growing the crop in the state); in 1997-98, the average Secondly, the regime has had the effect of releasing control

peasant growing cotton in Andhra Pradesh made a net profit of over the terms on which peasants access inputs. These inputs,

only Rs 72 per hectare. These figures are likely to be wrong ranging from power to pesticides have gone outside the ambit

because of the widely held perception that the CACP underes- of state control. It is significant that in this respect, there has

timates various elements of cost in Andhra Pradesh. Thus, the been a coincidence of interests among both the central govern-

real situation may be far worse than that revealed by the CACP ment and the states. Nowhere was this more evident than in

data. Significantly, while yields have stagnated, and when farm- Andhra Pradesh, at least as long as Chandrababu Naidu was in

ers have been unable to command better prices, prices of a range power [Sridhar 2004].

of agricultural inputs have increased sharply. However, the reorientation of government spending priorities,

It is but natural that the poor agricultural performance, com- particularly the fiscal realignment, has reached government

bined with falling incomes, has had their adverse impact on the expenditures on rural development and has affected agriculture

peasantry. The proportion of gross domestic product (GDP) adversely. The impact of financial liberalisation has also affected

originating in agriculture in Andhra Pradesh declined much faster the terms on which public financial institutions lend for agri-

than at the all-India level. Moreover, the per capita GDP in cultural operations. This is not without significance for large

agriculture, measured in constant terms, has barely increased sections of the peasantry in the state. The single most important

since the mid-1990s and, in fact, has actually fallen in recent cause for death due to suicide by peasants has been the high cost

years. While aggregate per capita income increased somewhat of debt. That, in turn, has been caused by the increasing recourse

since 1993, agricultural income per capita of rural population to borrowing from private moneylenders, often on usurious terms.

has either stagnated or actually fallen. In fact, between 1993- The liberal package of the union government in the field of

94 to 1995-96 and 2001-02 to 2003-04, per capita GDP origi- agriculture has caused expenditures on rural development to fall.

nating in agriculture actually fell sharply, by about 12 per cent. The reduction in subsidies for fertilisers has been accompanied

by the withdrawal of state support for agricultural extension

Impact of Liberalisation services. Decline in investments in public infrastructure such as

energy and irrigation has also resulted from the fiscal squeeze.

The emphasis on the impact of shortage of water, often Financial liberalisation, including the redefining priority sector

nonchalantly labelled “crop failure”, misses the point that far too lending by banks, has effectively curtailed the public institutions’

many things are wrong with agriculture. Over the past 10-15 ability to make available rural credit, which made investment

years, the state has stepped back from its role as a promoter of more expensive and difficult, especially for small and marginal

agriculture. Significantly, the state has not only vacated the space peasants. The fact that such moneylenders also double up as

that truly belongs to it as the custodian of the poor and marginal suppliers of inputs such as fertilisers, has heightened the depen-

farmers, but actively facilitated the entry of the landed gentry dence of peasants on these agents, often resulting in desperation

to occupy this vital space. This is felt in every aspect of the when they are unable to repay their dues. In fact, suicide resulting

agricultural sector in Andhra Pradesh today. from an inability to repay their dues to these agents appears to

The package of a liberal regime, unbundled in 1991 at the be the typical feature of agriculture in Andhra Pradesh.

national and state levels, had adverse impact on the peasantry Things would not have been as bad if the policies of the state

in Andhra Pradesh, just as it had for the peasantry in other parts government were different from those unleashed in the rest of

of the country. It is significant that agriculture has been impacted the country. In fact, however, Andhra Pradesh took the lead in

without the union government actually implementing a set of pushing forth the liberal agenda, under the auspices of agencies

policies specifically targeted at agriculture. Although the present such as the World Bank. During the last decade the state

Table 2: Changes in Cropping Pattern

(Per Cent of Cropped Area)

Crops North Coastal Andhra South Coastal Andhra Rayalaseema South Telangana North Telangana Total State

1958 1998 1958 1998 1958 1998 1958 1998 1958 1998 1958 1998

Foodgrains 66.90 54.40 72.10 65.40 44.40 23.60 64.40 62.50 74.20 60.60 73.10 53.20

Groundnut 7.10 9.50 3.60 1.80 20.30 48.30 10.50 9.50 8.00 5.30 10.50 15.30

Oilseeds 11.30 12.90 6.30 3.70 21.40 56.30 19.50 20.30 15.10 10.80 15.30 20.80

Cotton 0.20 0.70 0.80 7.00 7.90 5.20 0.40 8.20 4.00 17.60 3.10 8.20

Others 21.60 32.00 20.80 23.90 26.30 14.90 15.50 9.00 6.70 11.00 11.60 17.80

Source: S Subramanyam (2002).

Economic and Political Weekly April 22, 2006 1561

government in Andhra Pradesh systematically reduced the role Although the feature of a full-blown agrarian crisis was already

of public investment, intervention and regulation. Private agents evident, the department of agriculture in Andhra Pradesh issued

were expected to fill the vacuum caused by the withdrawal of a white paper in 1999 stating that the government could act only

the state. as a facilitator. It said that no public investment would be

The decline in public investment in agriculture led to a sharp forthcoming to provide for these essential services. It pointed

deceleration in the growth of fixed capital formation in agriculture out that it would not fill up the more than one-fourth of the

in the 1990s. This is especially striking when seen in the context sanctioned posts that were vacant, claiming that the government

of the high rates registered in the 1980s. It is not surprising that did not have “resources to employ any more extension workers.”

the area covered by public sources of irrigation, namely, canals, Instead, the department proposed to wind up the entire cadre of

declined in the 1990s. It is also significant that despite the hype agricultural extension officers. It envisaged that extension ser-

of the Naidu’s regime, no new major irrigation project was taken vices would be promoted through the private sector, by taking

up in its tenure extending over nine years; in fact, several projects either the unemployed or retired employees. The burden on the

pending were not even completed. AP Seed Corporation would be reduced by making the private

Resources for irrigation, already scarce because of the fiscal sector more accountable through appropriate memorandum of

squeeze, were thinly spread over a large number of watersheds understanding (MoU). The hiring of agricultural machinery would

instead of making an intensive effort to make investments more be encouraged through the corporate sector, NGOs and others.

effective and worthwhile. The reforms in the electricity sector, Soil survey, soil conservation and collection of market informa-

assiduously promoted by the World Bank, caused a sharp increase tion were to be “encouraged to be developed in private sector

in the cost of power in the state. Although farmers paid only with appropriate policy incentives.”

a flat rate (which increased from Rs 50 to Rs 300), they had to It was but natural that in keeping with this world view of the

incur heavy losses due to erratic power, low voltage and burned state government, a number of public institutions catering to the

motors. needs of the agricultural sector were either undermined or

Although more than 10,000 water users’ associations (WUAs) completely closed down. The government corporations or co-

were constituted (about 80 per cent in the minor irrigation sector), operative institutions, such as the Andhra Pradesh Irrigation

the bulk of the area covered is under canal irrigation. Moreover, Development Corporation, Agro-Industries Corporation, Seeds

irrigation charges were increased by more than three times since Development Corporation, cooperative sugar factories, and

1997 even though the surface water rates cover merely the cooperative spinning mills which were envisaged to help farmers,

maintenance charges. In contrast, those depending on lift irri- were closed down, or allowed to degenerate or handed over to

gation, particularly in the drier tracts of the state – mainly in the private sector.

Rayalaseema and Telangana – bear the full capital cost of the The state, by failing to regulate the supply of inputs, has also

well or bore. seriously jeopardised the interests of farmers. Spurious seeds

The bulk of the incremental addition to irrigation capacity in have been a major problem. All that the state has done is to enter

the last 10-15 years has come from well irrigation. This means into a MoU with seed companies. In reality, the state has no

that the burden has fallen on individual farmers. It is obvious control over the quality of seeds. The large number of suicides

to those who have followed the agrarian crisis that the depletion in Warangal, for instance in 1997-98, were caused by the wide-

of groundwater resources in areas such as Telangana heaped a spread use of spurious cotton seeds provided by private seed

disproportionate burden on those who had made risky invest- companies. The problem with seeds is not confined to their

ments in irrigation. Farmers in this region have repeatedly made quality; farmers now pay much more. Paddy seed prices, for

heavy investments in bore wells and failed miserably (see instance, have doubled since 1990; prices of cotton and chilli

Appendix). The state has not only failed to provide irrigation seeds have increased fourfold during the same period. Similar

facilities, but actually imposed a squeeze on credit for such purposes complaints about adulterated pesticides and fertilisers have

when it was needed the most. As a result, peasants, in a desperate been reported from across the state. It is estimated that

search for water, have had to borrow at usurious rates of interest. fertiliser costs have increased fourfold since 1992. The rise in

The field of agricultural research and extension had also been the cost of inputs, apart from the sharp increase in electricity

under prolonged neglect. In 1992-94 the extent of government charges during the Chandrababu Naidu regime, has placed the

investment in agricultural research and education in the state, farmer in Andhra Pradesh at a disadvantage when compared to

measured in terms of expenses in relation to the GDP originating those in other states.

in agriculture was a mere 0.26 per cent, compared to the all-India The liberalised policies, which are geared more towards cre-

level of 0.49 per cent. The level in Andhra Pradesh was much ating a pan-Indian primary commodity market with a unified

lower than those prevailing in the other southern states. Expen-

diture on public extension services, mainly borne by state gov- Table 3: Net Income Per Hectare in Andhra Pradesh

ernments, declined in absolute terms in the 1990s in Andhra (at 1971-72 prices)

Pradesh. This was only 0.02 per cent of the state’s GDP during

Paddy Groundnut Sugar Cane Cotton

1992-94, compared to the all-India average of 0.15 per cent. Indeed,

there were attempts to privatise extension services in the state. Early 1970s 314 - 0

The complete collapse of the machinery for providing agri- Mid-1970s 81 -116 186

cultural extension services, combined with the closure of avenues Late 1970s -36 -65 1056 638

Early 1980s 150 -15 809 -

for drawing credit from institutional sources, exposed small and Mid-1980s 140 -88 2194 -

marginal peasants in the state to the caprices of private money- Late 1980s 215 -52 816 104

lenders and input suppliers, more often rolled into one. The Early 1990s 221 -9 1119 -

freedom that these players enjoyed, remaining outside the pur- Mid-1990s 227 -117 1563 474

view of any state control, made matters worse for the peasantry. Late 1990s 167 -123 1139 -

The frequent complaints of poor quality seeds, pesticides and Source: CACP, quoted by Directorate of Economics and Statistics, government

fertilisers have to be placed in this context. of Andhra Pradesh.

1562 Economic and Political Weekly April 22, 2006

price, in alignment with global prices, have clearly worked bear the uncertainty of crop failure without any assistance from

against farmers in the state. The cotton farmer in Warangal the state. Most farmers in Anantapur grow only one crop, which

district, for instance, was cajoled into producing cotton by the means that the fields are fallow for 8 to 9 months a year. Less than

state more than a decade ago. Sudarshan Reddy, who conducted 10 per cent of the cultivated area is irrigated. The tenfold increase

an inquiry into the suicides by farmers in the district in 1997- in the import of edible oils has meant lower prices for the peasant,

98, said that the state encouraged the farmer to grow cotton but according to leaders of peasant organisations [Sridhar 2004].

has since then left him in a lurch. The state did this despite the Even land prices have dropped dramatically in the past few

soil conditions being unsuitable for cotton cultivation. years. Land in Anantapur, which used to command a price of

Rising costs of cultivation have meant that the cost of pro- Rs 40,000 to Rs 50,000 an acre five years ago, now goes for

duction of paddy in Andhra Pradesh is higher by about 16 per Rs 10,000. Peasants in distress have sold all that they had – cattle,

cent when compared to the cost in Punjab; the cost of growing houses and even their land. Many have migrated in the hope of

cotton is higher by more than one-third when compared to that escaping extreme distress.

in Gujarat; and the costs of groundnut production is 38 per cent Even suicide does not appear to relieve the Andhra Pradesh

higher in the state when compared to that in Gujarat. Severe peasant of his debts. Travelling across Telangana and coastal

fluctuations in the prices of produce have added to the uncertainty Andhra, I met at least a dozen peasant-families of suicide victims

in the lives of farmers. Although the state has several agricultural in the summer of 2004. Not a single case was found in which

market committees, which are supposed to act as procurement the death provided deliverance from debt. Barely days after the

agencies and provide remunerative prices, it is obvious that they death, the creditors, moneylenders and dealers of fertilisers,

are defunct. In 2002, a committee, which conducted an inquiry pesticides and seeds and even “friends” and “relatives” continued

into the phenomenon of farmer suicides in the state, reported that to press the hapless families to clear the outstanding debts of

these committees were procuring an insignificant portion of the the deceased. Despite the grief, the families were cautious when

total produce in the state. referring to their creditors. Not a word was spoken in rancour.

The burden of the agrarian crisis has obviously fallen on the In fact, it appeared that they were at the mercy of the lenders

small and marginal farmers. More than 80 per cent of the land- like never before.

holdings are of sizes up to two hectares and constitute 43 per The policies have not only effected a quantum jump in the cost

cent of the cultivated area. Moreover, tenant cultivators with little of crucial inputs such as power, but allowed full play to seed,

or no land, pay exorbitant rents to landlords. High rents charged fertiliser and pesticide dealers. A crucial part of the “package”

by absentee landlords in coastal Andhra Pradesh, amounting to has been the peasant’s lack of access to credit from institutional

more than half the annual produce of the farmer, are a serious sources – nationalised banks, cooperatives and specialised rural

burden on the peasantry. The rising cost of cultivation, coupled banks. Credit from these sources has been virtually frozen in the

with the risks associated with it, has not only added to the burden last few years.

on the peasantry but made life uncertain for the poor peasant. Prices of inputs in Andhra Pradesh are among the highest in

The tenant’s plight is worse because, apart from the rack-renting the country. That is not difficult to fathom, considering the fact

by landlords, he is also totally outside the loop of the formal that the input suppliers are also the chief suppliers of credit to

credit mechanism. farmers. Credit furnished by private sources is rarely extended

The policies that have come to govern the peasant economy in cash. Inputs are supplied and these are “adjusted” against

have made the peasant unable to cope with even mild shocks borrowings already made by the peasant. This implies that the

in production, and his plight is aggravated by the state abdicating borrower has virtually no control over determining the price or

its role, particularly in extending institutional credit and framing quality of the inputs.1 It has been pointed out that the government

meaningful tenancy laws. had not even deployed geologists to help farmers in their search

Peasants in Andhra Pradesh, particularly the small and marginal for water, after failing to provide either institutional credit or

ones, are in the grip of a predatory commercialisation of agri- an insurance scheme to protect farmers from the enormous risk

culture. This has changed the face of rural indebtedness. In that they have to undertake in their desperate effort to locate

particular, the “withdrawal of the state” either as a facilitator or groundwater. Local residents said “water diviners” are having

as a provider of inputs, extension services or credit has been the a field day.2

key element of the pernicious policies that have wrecked the It is important to situate the ongoing agrarian crisis in the

peasant economy. Of course, the “withdrawal” has not happened context of the statistical fact that more than 80 per cent of the

accidentally. landholdings are about five acres (two hectares). Although some

have argued that the crisis in agriculture has affected sections

The Suicide Phenomenon

Table 4: Institutional Credit in Andhra Pradesh

The single most striking feature of the last round of suicides (Rs crore)

was the fact that they were not concentrated in a pocket of the

Year Crop Loans Term Loans

state as on previous occasions. Anantapur district, which is Target Actual Actual as Target Actual Actual as

possibly best designated as the “suicide capital” of India, used Percentage Percentage

to be better known until the last round of deaths. It has been of Target of Target

estimated that more than 450 peasants in the district have com-

1998-1999 4,115 3743 90.96 659 749 113.65

mitted suicide since 2000. The district has been hit by a series 1999-2000 4,500 4451 98.91 737 932 126.45

of droughts in recent years. But that is only to be expected since 2000-2001 6,019 4184 69.51 906 417 46.02

it generally records the second lowest rainfall in the country (next 2001-2002 7,500 6124 81.65 1200 689 57.41

to Jaisalmer district in Rajasthan). 2002-2003 8,600 6332 73.62 1345 593 44.08

Groundnut is grown in 90 per cent of the cultivable land in 2003-2004 9,667 7902 81.72 1515 733 48.38

2004-2005 11,205 1814

the district. The small and marginal peasant incurs a production

expenditure of about Rs 3,000 to Rs 4,000 an acre, but has to Source: Andhra Pradesh Cooperative Bank, 2004

Economic and Political Weekly April 22, 2006 1563

of all the middle and rich peasantry in parts of the state, it is State Response to Suicides

obvious that the small and marginal peasant and tenant cultivators

have borne the brunt of the crisis, particularly that of the collapse Till recently, the government’s response to the phenomenon

of institutional credit. It is evident that the advances made by of suicides by farmers was confined to adopting a posture of

formal sources of credit in the last few years have fallen far below denial. Even when it was accepted it was repeatedly argued that

the targets that they set for themselves (Table 4). The shortfall any relief measure would only cause more peasants to take their

is obvious, particularly in the release of term loans. One of the own lives. However, since the new government assumed power

main components of such advances is meant for enabling the after May 2004 elections, it has initiated a number of measures.

peasant to develop irrigation facilities. A substantial part of this, Although the long-term efficacy of the measures remains to be

according to bankers, is meant for digging wells. In 2003-04, seen, it is generally accepted that they have effectively stemmed

the government declared that 451 of the 1,127 mandals were the tide of suicides that erupted in 2004.

affected by drought. In 2002-03, 1,041 mandals were declared The Congress government in Andhra Pradesh which assumed

drought-hit and in 2001-02, 941 mandals were affected by drought. office in 2004 has recognised the magnitude of the agrarian crisis

The fact that term lending fell short by about 50 per cent of the and has already made clear its intention to redirect state policy

target in the three drought-hit years, when the peasants in the bearing in mind the need and interests of farmers. The cabinet

state suffered acute water shortage for crops, highlights the gross sub-committee report on the causes of farmers’ suicides indicates

failure of the institutional credit mechanism. It is obvious that that the government is already aware of the main forces behind

institutional credit failed the peasantry at the time when it was the crisis and the policies required. There are a number of positive

needed the most. measures which the state government has already instituted,

The condition of a tenant farmer is just as precarious as that which deserve to be noted.

of the small and marginal landowner. Having little or no land, The state government announced an ex-gratia amount of rupees

the tenant is forced to pay high rents to the absentee landlord, one lakh to the family of a deceased peasant and Rs 50,000

who often supplies seeds, pesticides, fertilisers and credit. In the towards liquidation of his/her farm debt. However, observers

Krishna and Godavari delta areas of coastal Andhra Pradesh, have pointed out that there are no budgetary allocations to ensure

where tenancy is as high as 60-80 per cent of the cultivated area, that this happens on a sustained basis. This is now dependent

rents take away more than half of the farmer’s produce. Tenancy on funds being available with the concerned district collector.

is entirely based on an oral agreement called ‘mooza vani kowlu’. It has also been pointed out that the process of identifying deaths

There are no papers or proof to show that the land is cultivated by suicide has been excessively bureaucratic in many cases,

by the tenant. The high rents, coupled with rising input costs which defeats the very purpose of the measure. Since the relief

and the high cost of informal credit, have made life extremely measure is available to “farm-related causes”, it is difficult for

precarious for poor tenants, many of whom graduated from the the members of the victim’s family to prove that a particular

ranks of agricultural workers in the last few decades. The suicide death is farm-related. However, the most important move

commercialisation of agriculture and the high rents mean that has been the moratorium on loans taken by farmers. A bill was

tenants are unable to cope with even relatively mild shocks in passed in the state assembly in 2004 providing a moratorium for

production. Since they have no documents that recognise their six months on private moneylenders. In addition, the two-year

rights as cultivators, the tenant cultivators are entirely outside moratorium on institutional credit recovery by commercial banks

the ambit of the formal credit market. In fact, several of them as declared by government of India is also being implemented.

in the heartland of the green revolution in West Godavari district There was also a drive to ensure increase disbursement of credit

told me that they were not even able to collect compensation by the banking institutions.

from the government for crops lost owing to cyclones and The deep-rooted nature of the agrarian crisis, resulting from a

inundation during the monsoon. They said that their landlords liberal package initiated in New Delhi, implies that much more needs

pocketed the money, because they held the land in their names. to be done at the state level to counter the effects of policies

Tenancy reforms, to feed the poor peasant’s acute hunger for in the sphere of agriculture. The crisis in agriculture is so deep and

land, are obviously an urgent requirement. But it is not even on widespread, that in spite of these positive measures, the conditions

the radar screens of the political class. It is not even a demand of farmers remain precarious, as evidenced by the continuing

that is being articulated by the poor peasant, who is hopelessly suicides despite various relief measures. Much more will be required

marginalised and is in utter despair. to make material improvements in the conditions of farmers.

It is well accepted, even in government circles, that the credit

institutions indulge in “ever-greening” of their accounts. It Conclusion

is known that a substantial portion of loans advanced by

institutions are not really “fresh advances”. Frequently, banks or The act of suicide, or the phenomenon of suicides on a wide-

credit cooperatives ask the peasant to clear his/her old dues spread basis, is usually provoked by a churn in socio-economic

including interest, upon which they extended the same conditions. Individuals and communities are under pressure to

amount again as a “fresh” loan to the farmer. In effect, the bank cope with the changes in the conditions of their lives, when society

merely makes a book adjustment, while managing to show an is in a state of flux. This is important in the case of Andhra Pradesh

increase in its credit disbursement. All this despite several because it has the dubious distinction of accounting for three out

studies on indebtedness among small farmers showing that of four suicides by farmers in India. Once it is accepted that the

the rate of recovery of loans from small and marginal farmers growing number of suicides within a community is provoked by

is higher than that for loans made to large farmers. Banks, sudden or dramatic changes in the terms on which their lives

increasingly under the sway of the logic of a liberal financial are lived, it is necessary to explore what these changes are and

regime, are discouraged from lending to small farmers. The policy how they have impacted the lives of the community, in this case,

appears to be oriented to the logic that it is better to lend to a the peasantry.

small number of large borrowers than to a large number of small It is becoming increasingly clear that the policies associated

borrowers. with the process of economic liberalisation, particularly since

1564 Economic and Political Weekly April 22, 2006

the 1990s, have impacted the lives of the peasantry in a major Ramanathan, who normally grows cotton or chillies on his two

way. It has also imposed a stress on the peasantry, which is acres, said agriculture was laden with risk. “Water is not the only

possibly responsible for them taking their own lives. A one-to- problem”, he said. “A good harvest means poor prices, but a bad

one straightforward causal relationship is difficult to establish. harvest is bad in every way”. He sold his chilli crop at Rs 1,200

However, it is evident that the logic of liberalisation, fundamen- a quintal in March 2004, but the current price is Rs 4,000. He

tally defined as allowing a greater play for market forces, whose pointed out that although the official procurement price of chillies

corollary is inevitably a “withdrawal” of the state, has added a had increased to Rs 2,600 from Rs 2,000 last year, his failed

qualitatively new dimension to the stress on the peasantry. It is crop would not get him anything anyway.

significant that the field of agrarian studies has suffered precisely The ruling “market rate” for credit in Chilpur is between 2.5

at a time when the peasantry has been the height of its distress. and 3 per cent a month, which works out to 36 per cent interest

It is therefore necessary to explore the dimensions of distress on an annual basis. Mallesam’s loans were taken mostly from

in Andhra Pradesh on a more extensive basis, particularly with friends and relatives, but he had also borrowed from a farmer

greater field-based exploration. The lessons from such an exercise in a nearby village. Mallesam’s father Sunka Venkatiah said that

in Andhra Pradesh could have important lessons for peasants the loan taken from the farmer bothered him more than anything

across the country, particularly because of the serious threat of else as the lender demanded early repayment. Mallesam had

farmer suicides erupting across the country. sought time in the past by signing a promissory note enabling

him to rollover the debts. But this obviously could not go on

Appendix indefinitely. Four days before he committed suicide, Mallesam

signed a promissory note mortgaging his next crop and agreeing

Case study: Suicide victim from Warangal district to pay compound interest on the accumulated debt. His father

Name: Sunka Mallesam said: “He must have known that his crop would not fetch him

Age: 35 anything. He just ran out of hope.”

Village: Chilpur Asked if the lenders exerted any pressure in the days before

Mandal: Station Ghanpur his death, Mallesam’s family is reticent. His neighbours explain

District: Warangal that violence was never really needed to recover loans from

Date of death: May 27, 2004 desperate borrowers. The existence of a cooperative bank at

A crowd is assembled under a shamiana as the priest conducts Venkatadripet, 2 km away, does not seem to have been an option

the ceremony on the tenth day after the death of Sunka Mallesam, for Mallesam. Venkatiah said that most people avoided the

a marginal farmer. He tried raising cotton on the three acres that cooperative bank because of the threat of attachment if dues were

he owned. In order to provide a measure of insurance from the not repaid. Mallesam’s neighbours said that windows of the

repeated failure of the cotton crop in this part of Warangal houses would be broken and taken away and even television

district, he also leased three acres and grew maize and paddy on antennas would be seized if the loans were not cleared. Nationalised

it. His brother Raja Komariah (40) migrated to Khammam five banks located in Ghanpur also do not issue fresh loans if earlier

years ago to work as a construction worker. He preferred to leave loans are not repaid. In short, public institutions do not offer a

his three acres fallow and migrate rather than suffer repeated flexible repayment schedule when the borrower is in difficulty.

losses like his brother by cultivating the “treacherous crop”, In contrast, the private lender is willing to extend credit, but at

cotton. a very steep price. Even that eventually drives the borrower to

Finding water for cultivation was always a problem, and it a corner. The family also said that it had not received any succour

drove Mallesam to death. Komariah said that Mallesam spent from the government. It fears that the lenders will descend on

about Rs 30,000 on digging a bore well, laying pipelines and them if it got anything at all from the government. -29

installing a motor in May 2003. Although the bore ran 90 metres

deep, there was no water. A desperate Mallesam dug another bore Email: vsridhar@thehindu.co.in

well in January 2004, which also turned dry. By then the total

debts he had piled up in trying to procure water amounted to Notes

more than Rs 75,000. In what turned out to be a gamble, he

invested Rs 35,000 on the cotton crop. 1 In parts of Nalgonda district, which reported 31 suicides in the two-month

Rajamma (27), Mallesam’s wife, said that he was already period between May and July 2004, peasants have dug bore well after

burdened by debts incurred in 1998 when their daughter suffered bore well in a desperate search for water. The money advanced by private

from “brain fever”. The couple had spent Rs 40,000, borrowed moneylenders is paid directly to the rig operators, enabling them to

mainly from friends and relatives, to treat her. Komariah said that collude against the peasants [Sridhar 2004a]. An average farmer in the

district, with about three acres of land, had struck at least three or four

they managed to repay some of the earlier loans but their debts bore wells going down to 250-300 feet, each attempt costing him at least

amounted to Rs 96,000 at the time Mallesam took his own life. Rs 10,000.

Damera Ramanathan (45), whose field was adjacent to 2 One technique, apparently a popular one, involves the “diviner” walking

Mallesam’s, said that they used to discuss their debts. He said around the farm carrying a coconut in his palm. The stalk supposedly stands

he too had debts, amounting to over Rs 40,000. He too suffered upright at the spot where the bore is to be drilled. This bizarre technique

losses because of failed bore wells. Ramanathan said Mallesam even stipulates that the blood group of the “diviner” should be O positive.

had told him that he proposed to migrate to Bhadrachalam to

work as a “coolie”. “I persuaded him not to migrate, but I do References

not know whether I gave him the right advice,” Ramanathan said.

They met for the last time 15 days before Mallesam died. Mallesam Durkheim, Emile (1951): ‘Suicide: ‘A Study in Sociology’ ’, translated by

George Simpson and John A Spaulding, The Free Press, New York.

said he had sold his two bullocks for about Rs 6,000. On the Patnaik, Utsa (2004): ‘It is a Crisis Rooted in Economic Reforms’, Frontline,

morning of May 27, Mallesam was found lying near his well. 21(13), pp 22-26.

Barely conscious, he told a neighbour that he had consumed Sridhar, V (2004): ‘Neoliberalism Spurned’, Frontline, 21(12), pp 23-28.

pesticide. He died soon after. – (2004a): ‘From Debt to Death’, Frontline, 21(13), pp 13-16.

Economic and Political Weekly April 22, 2006 1565

You might also like

- Conditioning Guide and Basic Tips During TrainingDocument2 pagesConditioning Guide and Basic Tips During TrainingRonald SuyongNo ratings yet

- Supply Analysis in The Philippine Corn IndustryDocument4 pagesSupply Analysis in The Philippine Corn Industryhgciso50% (2)

- Farmers SuicideDocument8 pagesFarmers SuicideparulNo ratings yet

- Farmers Suicide PresentationDocument19 pagesFarmers Suicide PresentationNeeraj Shukla0% (1)

- Farmer Suicides in IndiaDocument19 pagesFarmer Suicides in IndiaKevin JamesNo ratings yet

- KC Suri On Agrarian DistressDocument8 pagesKC Suri On Agrarian DistressKumar BhaskarNo ratings yet

- Indirectly Depends Upon Agriculture.: Causes of Farmers' SuicidesDocument6 pagesIndirectly Depends Upon Agriculture.: Causes of Farmers' SuicidesSivaNo ratings yet

- Farmers SuicideDocument16 pagesFarmers SuicideSANJIVAN CHAKRABORTYNo ratings yet

- Every 30 Minutes: Farmer Suicides and The Agrarian Crisis in IndiaDocument57 pagesEvery 30 Minutes: Farmer Suicides and The Agrarian Crisis in IndiaRakhi LalwaniNo ratings yet

- Munn fARNER KILLDocument11 pagesMunn fARNER KILLParth PandeyNo ratings yet

- Farmer Suicides in IndiaDocument26 pagesFarmer Suicides in IndiaMugdha TomarNo ratings yet

- Farmers Suicide in IndiaDocument32 pagesFarmers Suicide in IndiaSajjad Sayyed100% (1)

- Srivyshnavi Subedari PaperDocument10 pagesSrivyshnavi Subedari PaperVyshu SubeNo ratings yet

- Farmers Suicide Panel Data RegressionDocument14 pagesFarmers Suicide Panel Data RegressionAbhishek GoyalNo ratings yet

- Farmers' Suicides in India: CausesDocument3 pagesFarmers' Suicides in India: CausesŚáńtőśh MőkáśhíNo ratings yet

- Nitin Pavuluri ' Paper On Farmer SucidesDocument9 pagesNitin Pavuluri ' Paper On Farmer SucidesShweta EppakayalNo ratings yet

- Trends and Causes of Farmers Suicide inDocument14 pagesTrends and Causes of Farmers Suicide inrohini soniNo ratings yet

- Farmers Suicide in India Is On The RiseDocument2 pagesFarmers Suicide in India Is On The Riseumang24No ratings yet

- Agrarian Distress and Farmers Suicide in IndiaDocument37 pagesAgrarian Distress and Farmers Suicide in Indiakanaks1992No ratings yet

- Farmer Suicides in India Trends Causes and PolicyDocument12 pagesFarmer Suicides in India Trends Causes and PolicyMuskan MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Globalization and Effects On Indian AgriDocument7 pagesGlobalization and Effects On Indian AgriHarshVardhan AryaNo ratings yet

- In Light of Readings Provided, Reflect On Any Aspect of The Current Agrarian Crisis in IndiaDocument3 pagesIn Light of Readings Provided, Reflect On Any Aspect of The Current Agrarian Crisis in IndiaankitNo ratings yet

- India's Farm Crisis Decades Old and With Deep Roots HimanshuDocument20 pagesIndia's Farm Crisis Decades Old and With Deep Roots HimanshujonathshijanzoomNo ratings yet

- Esha ShahDocument22 pagesEsha Shahabhiruchi_b_ranjanNo ratings yet

- Farmer Suicides & Media CoverageDocument28 pagesFarmer Suicides & Media CoverageprabhakarNo ratings yet

- Rupal Gupta DissertationDocument28 pagesRupal Gupta Dissertationrupal_delNo ratings yet

- Farmers Distress and Agrarian Crisis in India - Converted - by - FreepdfconverterDocument4 pagesFarmers Distress and Agrarian Crisis in India - Converted - by - FreepdfconverterGurjotSinghNo ratings yet

- Socio Cultural Analysis of Conflict Between Farmers and Herdsmen in Ondo StateDocument7 pagesSocio Cultural Analysis of Conflict Between Farmers and Herdsmen in Ondo StateEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Farmer SucideDocument14 pagesFarmer SucideShoaib Khan ShoaibNo ratings yet

- Farmers Sucides in IndiaDocument11 pagesFarmers Sucides in IndiaRaj ShindeNo ratings yet

- Farmers' Suicides and The State in IndiaDocument30 pagesFarmers' Suicides and The State in IndiaAmitrajit BasuNo ratings yet

- The GMO-Suicide Myth: Keith KloorDocument6 pagesThe GMO-Suicide Myth: Keith KloorNicholas GravesNo ratings yet

- Farmers' Suicides in India - Reasons and ResponsesDocument6 pagesFarmers' Suicides in India - Reasons and ResponsesANISH DUTTANo ratings yet

- Vishvesh Shrivastav C-32 Farmer Suicides in IndiaDocument5 pagesVishvesh Shrivastav C-32 Farmer Suicides in IndiavishveshNo ratings yet

- Agrarian Crisis - Life at Stake in Rural IndiaDocument110 pagesAgrarian Crisis - Life at Stake in Rural IndiaTsao Mayur ChetiaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Covid-19Document7 pagesImpact of Covid-19Komlangi BajprehiNo ratings yet

- Indian Press Coverage of Farmers Suicides in Andh PDFDocument13 pagesIndian Press Coverage of Farmers Suicides in Andh PDFakhil SrinadhuNo ratings yet

- Rich Peasant, Poor PeasantDocument8 pagesRich Peasant, Poor PeasantAshish RajadhyakshaNo ratings yet

- Gail Omvedt - Reinventing Revolution - New Social Movements and The Socialist Tradition in India-Routledge (1993)Document24 pagesGail Omvedt - Reinventing Revolution - New Social Movements and The Socialist Tradition in India-Routledge (1993)Lishi DodumNo ratings yet

- Farmers' Suicides in India PDFDocument31 pagesFarmers' Suicides in India PDFNayan AnandNo ratings yet

- Herders/Farmers Conflict and Economic Development of Numan Local Government AREA, ADAMAWA STATE (2015 - 2022)Document14 pagesHerders/Farmers Conflict and Economic Development of Numan Local Government AREA, ADAMAWA STATE (2015 - 2022)Owen Lamidi AndenyangNo ratings yet

- Farmers Suicide in IndiaDocument1 pageFarmers Suicide in IndiadylanloaruizNo ratings yet

- Agricultural Crisis and Farmers Suicides in India: K. Reddy Sai Sravanth, N. SundaramDocument5 pagesAgricultural Crisis and Farmers Suicides in India: K. Reddy Sai Sravanth, N. SundaramRahul BhusariNo ratings yet

- Peasant MovementsDocument2 pagesPeasant MovementsD M KNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Farmers' Suicide in IndiaDocument5 pagesFactors Affecting Farmers' Suicide in IndiaSocial Science Journal for Advanced ResearchNo ratings yet

- Agriculture UrbanDocument42 pagesAgriculture UrbanVaibhav JNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Farmer Suicide in IndiaDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Farmer Suicide in Indiaistdijaod100% (1)

- Ijmra 15590 PDFDocument14 pagesIjmra 15590 PDFMuhammad SyafiqNo ratings yet

- Farmer Suicides: The Burden of Local NarrativesDocument3 pagesFarmer Suicides: The Burden of Local NarrativesabhinavNo ratings yet

- A Bitter HarvestDocument37 pagesA Bitter HarvestJaskaran SinghNo ratings yet

- The Distress in Rural India: Anil Kumar VaddirajuDocument12 pagesThe Distress in Rural India: Anil Kumar VaddirajuAnandNo ratings yet

- Farmers Suicide and Response of The Government in India - An AnalysisDocument6 pagesFarmers Suicide and Response of The Government in India - An Analysismahesh gottipatiNo ratings yet

- Farmers Suicide and Response of The Government in India - An AnalysisDocument6 pagesFarmers Suicide and Response of The Government in India - An Analysismahesh gottipatiNo ratings yet

- History Major 1Document5 pagesHistory Major 1Udit BajpaiNo ratings yet

- Current Affairs Agriculture: NotesDocument10 pagesCurrent Affairs Agriculture: NotesArvind BoudhaNo ratings yet

- Update 12Document75 pagesUpdate 12suvromallickNo ratings yet

- Logical Analysis On Farmers Protest: Submitted by Harshit ShekharDocument5 pagesLogical Analysis On Farmers Protest: Submitted by Harshit ShekharHarshit ShekharNo ratings yet

- IiedDocument4 pagesIiedmonNo ratings yet

- Abraham Ma ThewDocument46 pagesAbraham Ma ThewAnns IssacNo ratings yet

- CassavaDocument113 pagesCassavaGaurav kumarNo ratings yet

- Model Bankable Project-Floriculture SamDocument16 pagesModel Bankable Project-Floriculture Samsamuvel samNo ratings yet

- Hotspots Magazine - 2012-02-01Document132 pagesHotspots Magazine - 2012-02-01Holstein PlazaNo ratings yet

- Barik ProposalDocument11 pagesBarik Proposal'Rex Lee Saleng DullitNo ratings yet

- Love in The Cornhusks by Aida LDocument4 pagesLove in The Cornhusks by Aida LRyanMontancesPacayra0% (1)

- DLL COT Fro ObservationDocument12 pagesDLL COT Fro ObservationShirline Salva FabeNo ratings yet

- FAO Forage Profile - TunisiaDocument22 pagesFAO Forage Profile - TunisiaAlbyziaNo ratings yet

- Applications of Gis and Remote Sensing in The Field of "Irrigation and Agriculture"Document19 pagesApplications of Gis and Remote Sensing in The Field of "Irrigation and Agriculture"Dileesha WeliwaththaNo ratings yet

- በቆቆሎሎDocument49 pagesበቆቆሎሎJemalNo ratings yet

- Crop Diversification Is A Concept Which Is Opposite To Crop SpecializaDocument2 pagesCrop Diversification Is A Concept Which Is Opposite To Crop SpecializaMuhammad ChaudhryNo ratings yet

- Rythu Sadhikara SamsthaDocument5 pagesRythu Sadhikara SamsthaChinnaBabuNo ratings yet

- Chapter 16 Harvesting and TransportDocument16 pagesChapter 16 Harvesting and TransportBhupender Singh RathoreNo ratings yet

- AzerothDocument13 pagesAzerothJoe ConawayNo ratings yet

- Project Report On GaushalaDocument5 pagesProject Report On GaushalaArjun Sharma0% (1)

- Organic Farming: Concept and Components: January 2014Document11 pagesOrganic Farming: Concept and Components: January 2014Ka RaNo ratings yet

- Biology Practical Reports For Form 4 Experiment 8.3 (Practical Textbook Page 108)Document2 pagesBiology Practical Reports For Form 4 Experiment 8.3 (Practical Textbook Page 108)ke2100% (1)

- Zuidberg Pricelist Update September 2013Document157 pagesZuidberg Pricelist Update September 2013emmanolan100% (1)

- 59 - Buklod NG Magbubukid Sa Lupaing Ramos v. E.M. Ramos & SonsDocument6 pages59 - Buklod NG Magbubukid Sa Lupaing Ramos v. E.M. Ramos & SonsApay Grajo100% (2)

- Kalumbete NotesDocument42 pagesKalumbete NotesAlbert MoshiNo ratings yet

- System of PlantingDocument36 pagesSystem of PlantingBhing BacalsoNo ratings yet

- Gene For Genehypothesisitsvalidtyinthepresentscenario 141129111805 Conversion Gate02Document48 pagesGene For Genehypothesisitsvalidtyinthepresentscenario 141129111805 Conversion Gate02BasavarajNo ratings yet

- Dairy Farmer-Entrepreneur AssessmentDocument5 pagesDairy Farmer-Entrepreneur AssessmentMohdKashanNo ratings yet

- Seminar Paper11111Document22 pagesSeminar Paper11111Mulugeta88% (8)

- Domaine Gérard Boulay Sancerre Les Monts DamnésDocument2 pagesDomaine Gérard Boulay Sancerre Les Monts DamnésYing CaiNo ratings yet

- Project Report-POWER FENCINGDocument8 pagesProject Report-POWER FENCINGMeenaNanjundanNo ratings yet

- TC 2016 WebDocument140 pagesTC 2016 WebFrancis SalviejoNo ratings yet

- Institute of Rural Management Anand: End Term Examination (Open Book)Document5 pagesInstitute of Rural Management Anand: End Term Examination (Open Book)VishalNo ratings yet

- Pineapple BookletDocument17 pagesPineapple BookletKaren Lambojon BuladacoNo ratings yet