Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Exercise Dependence and Muscle Dysmorphia in Novice

Exercise Dependence and Muscle Dysmorphia in Novice

Uploaded by

amandarhp12Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Exercise Dependence and Muscle Dysmorphia in Novice

Exercise Dependence and Muscle Dysmorphia in Novice

Uploaded by

amandarhp12Copyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Behavioral Addictions 2(4), pp.

244–248 (2013)

DOI: 10.1556/JBA.2.2013.4.8

Exercise dependence and muscle dysmorphia in novice

and experienced female bodybuilders

BRUCE D. HALE*, DANIELLE DIEHL, KRISTA WEAVER and MICHAEL BRIGGS

Berks College, Pennsylvania State University, Reading, PA, USA

(Received: July 9, 2013; revised manuscript received: September 13, 2013; accepted: October 13, 2013)

Background and aims: Extensive research has shown that male bodybuilders are at high risk for exercise depend-

ence, but few studies have measured these variables in female bodybuilders. Prior research has postulated that mus-

cular dysmorphia was more prevalent in men than women, but several qualitative studies of female bodybuilders

have indicated that female bodybuilders show the same body image concerns. Only one study has compared female

bodybuilders with control recreational female lifters on eating behaviors, body image, shape pre-occupation, body

dissatisfaction, and steroid use. The purpose of this study was to compare exercise dependence and muscle dysmor-

phia measures between groups of female weight lifters. Methods: Seventy-four female lifters were classified into

three lifting types (26 expert bodybuilders, 10 or more competitions; 29 novice bodybuilders, 3 or less competitions;

and 19 fitness lifters, at least 6 months prior lifting) who each completed a demographic questionnaire, the Exercise

Dependence Scale (EDS), the Drive for Thinness scale (DFT) of the Eating Disorder Inventory-2, the Bodybuilding

Dependence Scale (BDS), and the Muscle Dysmorphia Inventory (MDI). Results: Female bodybuilders scored

higher than fitness lifters for EDS Total, BDS Training and Social Dependence, and on Supplement Use, Dietary Be-

havior, Exercise Dependence, and Size Symmetry scales of the MDI. Discussion and conclusions: Female

bodybuilders seem to be more at risk for exercise dependence and muscle dysmorphia symptoms than female recre-

ational weight lifters.

Keywords: exercise dependence, muscle dysmorphia, female bodybuilders

INTRODUCTION size and/or strength even though they may actually be quite

large and muscular (Tod & Lavallee, 2010). Components of

Although medical practitioners agree that the majority of the MD include: body image distortion/dissatisfaction, dietary

population in western societies would benefit from more constraints, pharmacological aids, dietary supplements, ex-

regular exercise as part of a healthier lifestyle, a small per- ercise dependence, physique concealment, and low self-es-

centage of individuals may develop an obsessive approach teem (Muscle Dysmorphia Inventory, MDI; Rhea, Lantz &

that can be damaging physiologically, psychologically and Cornelius, 2004).

socially. Researchers and clinicians have recently reviewed One of these components, exercise dependence (ED),

the decades of emerging literature on excessive exercise in has been defined as “a craving for leisure time physical ac-

weight lifters, and some have concluded that the behaviors tivity that results in uncontrollable excessive exercise be-

are part of an obsessive-compulsive disorder diagnosis (e.g., havior and that manifests in physiological symptoms (e.g.,

Pope, Phillips & Olivardia, 2000), while others suggest that tolerance, withdrawal) and/or psychological symptoms

the symptoms are part of a body dysmorphia/body image (e.g., anxiety, depression)” (Hausenblas & Symons Downs,

disorder diagnosis (e.g., Lantz, Rhea & Mayhew, 2001; 2002, p. 90). It has also been measured by the Exercise De-

McCreary & Sasse, 2000), and still others have sought to pendence Scale (EDS; Symons Downs, Hausenblas & Nigg,

differentiate it from a primary eating disorder (e.g., Hausen- 2004). In the bodybuilding realm, Smith, Hale and Collins

blas & Symons Downs, 2002). More recently, Berczik et al. (1998) also created and validated the Bodybuilding Depend-

(2012) have argued forcefully that excessive exercise is a ence Scale (BDS).

type of behavioral addiction. Unfortunately, almost all of the Leone, Sedory and Gray (2005) postulated that MD was

research that has been reviewed to date on addictive anaero- more prevalent in men than women, but several qualitative

bic exercise behavior (Hale & Smith, 2012; Tod & Lavallee, studies of female bodybuilders (Bolin, 1992; Guthrie &

2010) has involved male bodybuilding and weightlifting Castelnuovo, 1992; Klein, 1986, 1992) have stated that fe-

samples. male bodybuilders show the same body image concerns,

Whereas most western women seem to score high on the motivation for muscularity, and workout behaviors as

Drive for Thinness scale (DFT; Garner’s (1991) Eating Dis- males. While extensive reviews of quantitative studies have

order Inventory-2) and yearn to be thin and toned (Thomp- shown that male bodybuilders are at high risk for ED (Hale

son, Heinberg, Altabe & Tantleff-Dunn, 1999), men in the

last three decades are showing increasing scores in the drive

for muscularity (e.g., McCreary and Sasse’s (2000) Drive * Corresponding author: Bruce Hale, PhD, Dept. of Kinesiology,

for Muscularity Scale). According to researchers, some Penn State Berks, 114a BCC, Tulpehocken Rd., Reading, PA

weight lifters develop muscle dysmorphia (MD), view 19610, USA; Phone: +1-610-396-6156; Fax: +1-610-396-6155;

themselves as too thin, and may feel pressure to gain muscle E-mail: bdh1@psu.edu

ISSN 2062-5871 © 2013 Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest

Exercise dependence in female bodybuilders

& Smith, 2012; Smith & Hale, 2011) and may also suffer ican Psychiatric Association, 1994). The seven subscales

from MD (Tod & Lavallee, 2010), few quantitative designs (Tolerance, r = .78; Withdrawal Effects, r = .90; Continu-

(Smith & Hale, 2004; Goldfield, 2009) have measured these ance, r = .90; Lack of Control, r = .82; Reductions in Other

variables in female bodybuilders. Activities, r = .75; Time, r = .86; Intention, r = .89) have all

Goldfield (2009) was one of the few studies to compare shown acceptable scale score reliability; internal consis-

20 female bodybuilders with recreational female lifters on tency for total EDS score for this study was r = .92. Partici-

eating behaviors, body image, shape pre-occupation, body pants are categorized by a total score as “exercise depend-

dissatisfaction, and steroid use. He reported that bodybuild- ent”, “non-dependent symptomatic”, or “non-dependent

ers scored higher on the Bulimia subscale, Drive for Bulk asymptomatic”. Hausenblas and Symons Downs (2002) and

scale (Blouin & Goldfield, 1995), and Drive for Tone scale Hausenblas and Giacobbi (2004) presented evidence of con-

(Goldfield, 2009). More recently Hale, Roth, DeLong and current validity of the EDS.

Briggs (2010) found that male bodybuilders and power lift-

ers were significantly higher than fitness lifters on EDS To- Bodybuilding Dependence Scale

tal, seven EDS-R scales, and the three BDS scales. No study

to date has compared measures of MD and ED between dif- The Bodybuilding Dependence Scale (BDS; Smith et al.,

ferent groups of female weight lifters. 1998) is a 9-item, 7-choice Likert scale (“Strongly Disagree”

Although the estimates of bodybuilders suffering from to “Strongly Agree”) with three dimensions (Social Depend-

ED and MD may be small in western populations, the study ence, Training Dependence, and Mastery Dependence) to

of ED and MD in female weight lifters is warranted. This measure the degree to which ED is exhibited in weight lifters

study hypothesized that female bodybuilders would score based on Veale’s (1987) biomedical and psychosocial diag-

significantly higher in ED, MD (Hale & Smith, 2012; Smith nostic criteria. This measure has demonstrated adequate

& Hale, 2011; Tod & Lavallee, 2010), and lower in DFT psychometric internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha of .83,

(Goldfield, 2009) than female fitness lifters. .70, and .89, respectively, in this study), construct and concur-

rent validity (Hurst et al., 2000; Smith & Hale, 2004), and ad-

equate test–retest reliability (Smith & Hale, 2005) for each

METHODS scale (r = .97, .96, and .94, respectively).

Participants Muscle Dysmorphia Inventory

Seventy-four female weight lifters volunteered and were The Muscle Dysmorphia Inventory (MDI; Rhea et al., 2004)

classified (based on Hurst, Hale & Smith, 2000; Smith & is a 27-item, 6-point Likert scale measuring six subscales of

Hale, 2004) as 26 “expert bodybuilders” (10 or more body- MD: Size Symmetry, Supplement Use, Exercise Depend-

building competitions), 29 “novice bodybuilders” (three or ence, Pharmacological Use, Dietary Behavior, and Physique

less competitions), and 19 “fitness lifters” (at least 6 months Concealment. All subscales showed acceptable internal con-

prior lifting experience). Participants ranged in age from sistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84–0.92) in the present

18–48 years of age. Participants were recruited from a Penn- study. Significant correlations between the MDI subscales

sylvania university fitness center, several Pennsylvania and the BDS’s Training Dependence scale (Smith et al.,

health clubs, and the annual “Arnold Sports Festival” held in 1998) and the DFT scale of the Eating Disorder Inventory-2

2009 in Columbus, OH. All volunteers read implied in- (Garner, 1991) have provided evidence of convergent valid-

formed consent forms before anonymously completing ity (Rhea et al., 2004).

questionnaires; prior approval was obtained by the Univer-

sity’s institutional review board. Drive for Thinness Scale

The Drive for Thinness Scale of the Eating Disorder Inven-

MEASURES tory-2 (DFT; Garner, 1991) is a 7-item 6-point Likert sub-

scale to assess weight preoccupation. Research supports its

Demographic questionnaire validity and reliability (Garner, 1991; r = .80 for internal

consistency in this study). Hausenblas and Symons Downs

All participants completed a demographic questionnaire (2002) have used the subscale to categorize participants

(adapted from Hale et al., 2010) to examine prior lifting his- scoring above “14” as having a possible eating disorder and

tory. The questions concerned lifting experience (years lift- demonstrating signs of “secondary exercise dependence”.

ing), typical frequency per week (weekly frequency), length

of typical workout duration (session time), and intensity

(light, moderate, or heavy intensity). In addition, a total lifting PROCEDURE

time per week variable was created by multiplying the weekly

frequency and session time. Participants checked a lifter type Data collection and analysis

category (expert bodybuilder, novice bodybuilder, or fitness

lifter) based on their type of lifting experience. After gaining permission from each health club facility and

competition site, an implied consent form and the question-

Exercise Dependence Scale naire packet were distributed to each lifting participant. Par-

ticipants were asked to complete the packet honestly and

The Exercise Dependence Scale (EDS; Symons Downs et anonymously; all volunteers completed their packet and

al., 2004) is a 21-item multidimensional questionnaire with placed it in a sealed envelope to assure confidentiality. Par-

6-choice Likert scale ranging from “Always” to “Never” ticipants took about 15–20 minutes to complete each ques-

based on DSM-IV criteria for substance dependence (Amer- tionnaire packet.

Journal of Behavioral Addictions 2(4), pp. 244–248 (2013) | 245

Hale et al.

Single imputation procedure RESULTS

In one particular set of questionnaires, a question of the BDS

was inadvertently omitted. Because the other set of ques- Demographic variables

tionnaires did not have the missing question, a single impu- No significant differences occurred in total lifting time be-

tation procedure for missing data could be used. In this tech- tween expert and novice bodybuilders and fitness lifters,

nique four of the five questions that made up the Social De- F(2, 71) = 1.60, p = .21. A one-way ANOVA was significant

pendence subscale of the BDS were used to predict the fifth for years lifting, F(2, 71) = 4.09, p < .05, with expert body-

question. Using backwards selection regression methodol- builders (M = 7.95) and novice bodybuilders (M = 7.48) sig-

ogy, a model was constructed allowing for prediction of the nificantly more experienced than fitness lifters (M = 3.96).

fifth question. Though single imputation can sometimes lead For weekly frequency data, there were also significant group

to underestimated standard errors (Little, 1992), rationaliza- differences, F(2, 71) = 6.18, p < .05, with expert (M = 5.00)

tion for this approach is based on the assumption that the in- and novice (M = 5.13) bodybuilders working out signifi-

complete data was matched to the complete data with equal cantly more often than fitness lifters (M = 3.63). For session

lifting types. Since the appropriate matching of observations time, significant group differences also occurred, F(2, 71) =

was used, this single imputation technique would be equiva- 5.35, p < .05, with expert (M = 81.73) and novice (M =

lent to doing a direct replacement (i.e., finding another lifter; 76.55) bodybuilders spending significantly more time per

Donders, Van der Heijden, Stijnen & Moons, 2006). workout than fitness lifters (M = 52.21). Finally, for workout

intensity, there was another significant group main effect,

Statistical analysis F(2, 71) = 10.80, p < .05, with expert (M = 2.58) and novice

(M = 2.50) bodybuilders working out typically at a moder-

One-way ANOVAs were undertaken on the five demo- ate-high intensity, and fitness lifters (M = 1.84) typically ex-

graphic questions, total EDS score, and the DFT in order to erting at a light-moderate intensity (see Table 1).

examine potential group differences. One-way MANOVAs

were also calculated on the seven scales of the EDS, three

Exercise Dependence Scale

scales of the BDS, and the six scales of the MDI with Tukey

post hoc tests used for significant univariate findings to fur- A significant between-groups result occurred with EDS total

ther examine any possible group differences. score, F(2,71) = 4.26, p < .05, and Tukey-tests indicated that

expert bodybuilders (M = 75.19) scored significantly higher

Ethics than fitness lifters (M = 60.42) (see Table 1). The MANOVA

group main effect for the seven EDS scales was not signifi-

All volunteers read implied informed consent forms before cant, Wilks’ lambda = .72, F(14,130) = 1.49, p = .07, so no

anonymously completing questionnaires; prior approval further univariate analysis occurred.

was obtained by the University’s institutional review board. A frequency analysis of EDS total scores was undertaken

to find the percentage of participants identified by the scale

to be “at risk” for ED. A total of 13.5% (n = 10) were identi-

fied as “at risk”, 82.4% (n = 61) as “nondependent symp-

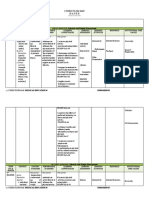

Table 1. Means and standard deviations of lifting type group differences

ExpBB (n = 26) NovBB (n = 29) FitLif (n = 19) F df p

M (SD) M (SD) M SD)

Total lift time 448.08 (218.24) 441.21 (252.42) 333.42 (224.79) 1.60 (2, 71) .21

Years lifting 7.95a (5.65) 7.48b (5.23) 3.96ab (3.16) 4.09 (2, 71) .02

Weekly freq. 5.00a (1.10) 5.13b (1.99) 3.63ab (1.26) 6.18 (2, 71) .003

Session time 81.73a (30.98) 76.55b (32.16) 52.21ab (19.88) 5.35 (2, 71) .007

Intensity 2.58a (.51) 2.50b (.51) 1.84ab (.50) 10.80 (2, 71) .001

Total EDS 75.19a (16.15) 71.41 (19.09) 60.42a (15.11) 4.26 (2, 71) .02

Bodybuilding Dependence Scale

Mastery depen. 7.88 (3.33) 8.34 (3.21) 6.17 (3.61) 2.56 (2, 71) .08

Social depen. 20.92a (5.30) 21.59b (6.61) 12.47ab (4.79) 16.68 (2, 71) .001

Training depen. 14.46a (2.77) 14.41b (3.91) 9.79ab (3.77) 12.35 (2, 71) .001

Muscle Dysmorphia Inventory

Supplement use 18.42a (4.82) 14.10b (6.21) 7.68ab (3.77) 23.43 (2, 71) .001

Pharmacol. use 4.27 (1.71) 4.34 (2.58) 3.63 (1.64) .76 (2, 71) .47

Dietary behavior 23.92a (3.78) 21.44b (5.32) 13.89ab (6.39) 21.80 (2, 71) .001

Exercise depen. 19.54a (3.64) 16.93b (3.66) 11.31ab (3.93) 27.24 (2, 71) .001

Physique conc. 13.04 (3.84) 13.97 (7.24) 10.53 (2.98) 15.31 (2, 71) .10

Size symmetry 17.62a (4.34) 16.17b (6.69) 10.26ab (4.29) 11.09 (2, 71) .001

Drive for thin 23.54 (7.87) 23.03 (6.93) 24.10 (7.44) .12 (2, 71) .89

a, b

p < .05 (Notes: a indicates significant differences between experienced bodybuilders and fitness lifters; b indicates significant differences be-

tween novice bodybuilders and fitness lifters.)

246 | Journal of Behavioral Addictions 2(4), pp. 244–248 (2013)

Exercise dependence in female bodybuilders

tomatic”, and 4.1% (n = 3) as “nondependent asymptom- differences between different lifting types. More partici-

atic”. Of the 10 “at risk” for ED, nine were bodybuilders and pants should have been measured in each lifting group,

one was a fitness lifter. In this sample of female lifters, the prevalence of

‘at-risk’ behavior for ED behaviors (13.5%) was found to be

Bodybuilding Dependence Scale higher than other college-age samples measured by the EDS

(3.4%, Hausenblas & Symons Downs, 2002; 3.6–5%,

A significant overall MANOVA group main effect (Wilks’ Symons Downs et al., 2004). Past findings (Allegre,

lambda = .66, F(6, 138) = 5.30, p < .05) was calculated. Uni- Souville, Therme & Griffiths, 2006; Hausenblas & Symons

variate F-tests showed that Training Dependence was signif- Downs, 2002; Terry, Szabo & Griffiths, 2004) of mixed

icant (F(2, 71) = 12.35, p < .001), and Tukey-tests indicated gender samples have been conservatively in the 3–13%

that expert (M = 14.46) and novice (M = 14.41) bodybuilders range. In this study nine out of 10 of the “at risk” scores

were significantly higher than fitness lifters (M = 9.79). A came from bodybuilder groups.

significant Social Dependence scale group main effect This at-risk finding is further supported by results from

(F(2, 71) = 16.68, p < .001) indicated that expert (M = 20.92) the BDS analysis. On two of the three scales, female

and novice (M = 21.59) bodybuilders were significantly bodybuilders scored higher than fitness lifters. These find-

higher than fitness lifters (M = 12.47) (see Table 1). No sig- ings are supported by Hale et al. (2010) and Smith and Hale

nificant group main effect was found for Mastery Depend- (2004) with male bodybuilders and fitness lifters.

ence, F(2, 71) = 2.56, p = .08. The results for the MD assessment also provided partial

support for the hypothesis that female novice and expert

Muscle Dysmorphia Inventory bodybuilders would score higher. The significant finding on

the Exercise Dependence scale suggests that women body-

A significant overall MANOVA group main effect (Wilks’ builders, like male bodybuilders, are at extremely high risk

lambda = .44, F(12, 132) = 5.59, p < .05) occurred. Univa- for MD symptoms (Smith & Hale, 2004; Tod & Lavallee,

riate F-tests indicated significant differences in Supplement 2010). These findings further support the qualitative find-

Use (F(2, 71) = 23.43, p < .001), Dietary Behavior (F(2, 71) ings of Bolin (1992), Guthrie and Castelnuovo (1992), and

= 21.80, p < .001), Exercise Dependence (F(2, 71) = 27.24, Klein (1986, 1992) and quantifiable results of Goldfield

p < .001), and Size Symmetry (F(2, 71) = 11.09, p < .01). (2009) with women bodybuilders. With no differences re-

Follow up Tukey post hoc tests showed that expert and nov- ported here between novice and experienced bodybuilders,

ice bodybuilders scored significantly higher than fitness lift- it suggests that women who are attracted to serious body-

ers on these four scales (see Table 1). building programs may arrive with symptoms of MD intact

already or may develop these symptoms soon after commit-

Drive for Thinness Scale ting to regimented training.

Finally, the non-significant findings between lifting

No significant differences occurred in DFT score between groups on the Drive for Thinness scale rejected our research

the lifting groups, F(2, 71) = .12, p = .89. hypothesis. Since Hausenblas and Symons Downs’ (2002)

criteria for secondary exercise dependence is a score of 14 or

better, all three groups seem to be highly at risk for an eating

DISCUSSION disorder. The high scores also suggest that in addition to a

potentially high drive for muscularity (McCreary & Sasse,

In general, bodybuilders spent more years, time in the gym, 2000), all female weight lifters may also want to remain ex-

and worked out harder than fitness lifters. This finding is tremely lean.

similar to differences in workout frequency reported for Recently Berczik et al. (2012) have suggested that ED

male bodybuilders and fitness lifters (Hale et al., 2010), but should be more appropriately labeled as exercise addiction

as Hausenblas and Symons Downs (2002) reported, exercise with six common symptoms (salience, mood modification,

behavior and history alone are not adequate predictors of tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, personal conflict, and re-

ED. The finding that bodybuilders’ typical workout was lapse). Furthermore, they assert that exercise addiction is a

moderate-high in intensity compared to fitness lifters’ form of behavioral addiction because of its preoccupation

light-moderate intensity was similar to recent findings of with the behavior when it is prevented or delayed. It is clear

Cook, Hausenblas and Rossi (2013), who reported that par- that measurement of ED (addiction?) needs improved diag-

ticipants who wanted to gain weight (e.g., bodybuilders) had nostic processes. A recent study by Heaney, Ginty, Carroll

significantly higher amounts of strenuous exercise than and Phillips (2011) showed that ED participants produced a

women who wanted to lose weight (e.g., fitness lifters). blunted cardiovascular and cortisol reaction to stress, similar

Other antecedent variables must be examined to try to un- to those seen in alcohol and smoking dependence; this find-

derstand the etiology of the disorder. ing may offer a more accurate, future objective measure-

The hypothesis that bodybuilders would show higher ment.

scores in exercise dependence was partially supported. Al- This study contains several design limitations. It was a

though a predicted higher score was calculated for expert correlational, cross-sectional design that could not provide

bodybuilders over fitness lifters in total EDS, the MANOVA cause-and-effect findings which might help predict the etiol-

for scale differences just failed to reach significance. Re-ex- ogy of ED and MD. In addition, the sample was voluntary

amination showed that the statistical power was .87, which and limited to a small group of bodybuilders from one major

is barely adequate for a multivariate analysis involving competition and several health clubs with a non-random fit-

seven dependent variables and 74 participants. The finding ness group used as a comparator, which reduced statistical

for higher total EDS scores is similar to other previous stud- power for internal validity and decreased the potential for

ies (Hale et al., 2010; Hurst et al., 2000) that have examined external validity. The questionnaires selected are only indic-

Journal of Behavioral Addictions 2(4), pp. 244–248 (2013) | 247

Hale et al.

ative of ‘at risk’ symptoms inherent in ED and MD; only Hale, B. D., Roth, A., DeLong, R. & Briggs, M. (2010). Exercise de-

clinical diagnostic procedures combined with question- pendence and the drive for muscularity in male bodybuilders,

naires and possible biochemical analyzes can lead to clear power lifters, and fitness lifters. Body Image, 7, 234–239.

diagnosis. Future research needs more diverse samples of fe- Hale, B. D. & Smith, D. (2012). Bodybuilding. In T. Cash (Ed.),

male weight lifters and ED and MD self-report measures Encyclopedia of body image and human performance (Chap-

given in random order that include measures that control for ter 46). Oxford, UK: Elsevier.

social desirability. Hausenblas, H. & Giacobbi, P. (2004). Relationship between exer-

In conclusion, the overall findings of this study support cise dependence symptoms and personality. Personality and

Individual Differences, 36, 1265–1273.

the hypothesis that female bodybuilders, whether new or ex-

Hausenblas, H. & Symons Downs, D. (2002). Exercise depend-

perienced competitors, show the same high risks for ED and

ence: A systematic review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise,

MD that male bodybuilders have shown (Hale & Smith,

3, 89–123.

2012; Tod & Lavallee, 2010). This study is one of the first Heaney, J., Ginty, A., Carroll, D. & Phillips, A. (2011). Preliminary

quantifiable cross-sectional designs to compare differences evidence that exercise dependence is associated with blunted

in potentially pathological exercise behaviors and eating dis- cardiac and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress. In-

orders in different female weight lifting groups. The find- ternational Journal of Psychophysiology, 79(2), 323–329.

ings suggest that either gender of bodybuilders may be at Hurst, R., Hale, B. D & Smith, D. (2000). Exercise dependence in

high risk for potentially addictive behavioral disorders (ex- bodybuilders and weight lifters. British Journal of Sports Med-

ercise dependence, muscle dysmorphia). icine, 11, 319–325.

Klein, A. M. (1986). Pumping iron: Crisis and contradiction in

bodybuilding subculture. Society of Sport Journal, 3, 112–133.

Klein, A. M. (1992). Man makes himself: Alienation and self-ob-

Funding sources: No financial support was received for this jectification in bodybuilding. Play and Culture, 5, 326–337.

study. Lantz, C. D., Rhea, D. J. & Mayhew, J. L. (2001). The drive for

size: A psycho-behavioral model of muscle dysmorphia. Inter-

Authors’ contribution: BDH (study concept and design, national Sport Journal, 5, 71–85.

analysis and interpretation of data, study supervision); DD Leone, J. E., Sedory, E. J. & Gray, K. A. (2005). Recognition and

(data collection); KW (data collection); MB (analysis and treatment of muscle dysmorphia and related body image disor-

interpretation of data; statistical analysis). ders. Journal of Athletic Training, 40, 352–359.

Little, R. J. A. (1992). Regression with missing x’s: A review. Journal

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest. of the American Statistical Association, 87(420), 1227–1237.

McCreary, D. R. & Sasse, D. K. (2000). An exploration of the drive

for muscularity in adolescent boys and girls. Journal of Ameri-

can College Health, 48, 297–304.

REFERENCES Pope, H. G., Phillips, K. A. & Olivardia, R. (2000). The Adonis

complex: The secret crisis of male body obsession. New York:

Free Press.

Allegre, B., Souville, M., Therme, P. & Griffiths, M. (2006). Defi-

Rhea, D. J., Lantz, C. D. & Cornelius, A. E. (2004). Development

nitions and measures of exercise dependence. Addiction Re-

of the Muscle Dysmorphia Inventory (MDI). The Journal of

search and Theory, 14, 631–646.

Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 44, 428–435.

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statisti-

Smith, D. & Hale, B. D. (2004). Validity and factor structure of the

cal manual of mental disorders (4th Edition). Washington, DC:

Bodybuilding Dependence Scale. British Journal of Sports

Author.

Medicine, 38, 177–181.

Berczik, K., Szabo, A., Griffiths, M. D., Kurimay, T., Kun, B., Ur-

Smith, D. & Hale, B. D. (2005). Exercise dependence in body-

ban, R. & Demetovics, Z. (2012). Exercise addiction: Symp-

building: Antecedents and reliability of measurement. Journal

toms, diagnosis, epidemiology, and etiology. Substance Use &

of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 45, 401– 408.

Misuse, 47, 403–417.

Smith, D. & Hale, B. D. (2011). Exercise dependence. In D.

Blouin, A. G. & Goldfield, G. S. (1995). Body image and steroid

Lavallee & D. Tod (Eds.), The psychology of strength training

use in male bodybuilders. International Journal of Eating Dis-

and conditioning (Chapter 8). London, UK: Routledge.

orders, 18, 159–165.

Smith, D. K., Hale, B. D. & Collins, D. J. (1998). Measurement of

Bolin, A. (1992). Flex appeal, food, and fat: Competitive body-

exercise dependence in bodybuilders. Journal of Sport Medi-

building, gender, and diet. Play and Culture, 5, 378–400.

cine and Physical Fitness, 38, 66–74.

Cook, B., Hausenblas, H. & Rossi, J. (2013). The moderating effect

Symons Downs, D., Hausenblas, H. & Nigg, C. R. (2004). Facto-

of gender on ideal-weight goals and exercise dependence

rial validity and psychometric examination of the Exercise De-

symptoms. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 2(1), 51–55.

pendence Scale-Revised. Measurement in Physical Education

doi:10.1556/JBA.1.2012.010 and Exercise Science, 8, 183–201.

Donders, A. R. T., Van der Heijden, G. J. M. G., Stijnen, T. & Terry, A., Szabo, A. & Griffiths, M. (2004). The Exercise Addic-

Moons, K. G. M. (2006). Review: A gentle introduction to im- tion Inventory: A new brief screening tool. Addiction Research

putation of missing values. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, and Theory, 12, 489–499.

59, 1087–1091. Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L. J., Altabe, M. & Tantleff-Dunn, S.

Garner, D. M. (1991). Eating Disorder Inventory-2 manual. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of

Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. body image disturbance. Washington, D.C.: American Psycho-

Goldfield, G. S. (2009). Body image, disordered eating, and anabo- logical Association.

lic steroid use in female bodybuilders. Eating Disorders, 17, Tod, D. & Lavallee, D. (2010). Towards a conceptual understanding

200–210. doi: 10.1080/10640260902848485 of muscle dysmorphia development and sustainment. Interna-

Guthrie, S. R. & Castelnuovo, S. (1992). Elite women body- tional Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 3(2), 111–131.

builders: Models of resistance or compliance? Play and Cul- Veale, D. (1987). Exercise dependence. British Journal of Addic-

ture, 5, 401–408. tion, 82, 735–740.

248 | Journal of Behavioral Addictions 2(4), pp. 244–248 (2013)

You might also like

- Brooks 5K Beginner Training PlanDocument4 pagesBrooks 5K Beginner Training PlanBrooksRunning0% (2)

- MAPS Starter Blueprints 4Document5 pagesMAPS Starter Blueprints 4Ashutosh Singh100% (1)

- AJAC Bodyweight BodybuildingDocument17 pagesAJAC Bodyweight BodybuildingGermanicus Malmberg100% (2)

- Fifa11+ Poster Referee PDFDocument1 pageFifa11+ Poster Referee PDFAndre LuísNo ratings yet

- The Weight Influenced Self-Esteem Questionnaire (WISE-Q) Factor Structure and Psychometric PropertiesDocument9 pagesThe Weight Influenced Self-Esteem Questionnaire (WISE-Q) Factor Structure and Psychometric PropertiesMagda RossatoNo ratings yet

- .Document11 pages.hey hooNo ratings yet

- TCA - Compte y DuthuDocument4 pagesTCA - Compte y DuthuGaby BarrozoNo ratings yet

- Biceps and Body Image The Relationship Between MusDocument10 pagesBiceps and Body Image The Relationship Between Musmarcewwe10No ratings yet

- Characteristics of Muscle Dysmorphia in Male Football, Weight Training and Bodybuilder 2009Document7 pagesCharacteristics of Muscle Dysmorphia in Male Football, Weight Training and Bodybuilder 2009Magno FilhoNo ratings yet

- Compte & Duthu, 2015Document3 pagesCompte & Duthu, 2015Emilio J. CompteNo ratings yet

- Psychosocial Predictors of Drive For Muscularity in Male Colle - 2015 - Body ImaDocument5 pagesPsychosocial Predictors of Drive For Muscularity in Male Colle - 2015 - Body ImaCarolina CamoesasNo ratings yet

- Unconditional AcceptanceDocument10 pagesUnconditional AcceptanceIoanna NannaNo ratings yet

- Lantz 2002Document7 pagesLantz 2002Robert FluoroCarbonNo ratings yet

- The Body DissatisfactionDocument15 pagesThe Body DissatisfactionAsmah GhazaliNo ratings yet

- Critical Factors of Social Physique Anxiety: Exercising and Body Image SatisfactionDocument12 pagesCritical Factors of Social Physique Anxiety: Exercising and Body Image Satisfactionfotinimavr94No ratings yet

- BBRC Vol 14 No 04 2021-91Document5 pagesBBRC Vol 14 No 04 2021-91Dr Sharique AliNo ratings yet

- Louw 2012 - Sample Article On Correlates (Easy To Understand) 1Document11 pagesLouw 2012 - Sample Article On Correlates (Easy To Understand) 1Christopher LeNo ratings yet

- Escala de Dependencia Do Exercicio Fisico - ENDocument20 pagesEscala de Dependencia Do Exercicio Fisico - ENBruna MacedoNo ratings yet

- Healy 2018Document16 pagesHealy 2018Nahara LimaNo ratings yet

- Body ImageDocument18 pagesBody ImageDewa SatyaNo ratings yet

- LESSON 3 and 4 Module 2Document16 pagesLESSON 3 and 4 Module 2Jerry PalarionNo ratings yet

- Dismorfia Muscular, Imagen Corporal y Conductas Alimentarioas en Dos Poblaciones MasculinasDocument9 pagesDismorfia Muscular, Imagen Corporal y Conductas Alimentarioas en Dos Poblaciones Masculinasamandarhp12No ratings yet

- Body Concerns Ex Behaviour PaperDocument16 pagesBody Concerns Ex Behaviour PaperMohit KharbandaNo ratings yet

- Body Image Binge EatingDocument7 pagesBody Image Binge EatingangelaNo ratings yet

- Exercise Performance: LessonDocument5 pagesExercise Performance: LessonBOSSMEYJNo ratings yet

- Rosen Et Al, 1995Document8 pagesRosen Et Al, 1995DiegoNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Body Image Flexibility - BIAAQDocument11 pagesAssessment of Body Image Flexibility - BIAAQomsohamomNo ratings yet

- Applied Statistics Project Group No. 5 Section ADocument7 pagesApplied Statistics Project Group No. 5 Section AmadihaNo ratings yet

- Desouza2007 PDFDocument9 pagesDesouza2007 PDFAndra SpatarNo ratings yet

- 14 613 1 PBDocument7 pages14 613 1 PBVanessa Cruz RuizNo ratings yet

- Body Image Dissatisfaction: Gender Differences in Eating Attitudes, Self-Esteem, and Reasons For ExerciseDocument18 pagesBody Image Dissatisfaction: Gender Differences in Eating Attitudes, Self-Esteem, and Reasons For ExerciseNimic NimicNo ratings yet

- The Efficacy of A 9-Month Treadmill Walking Program On The Exercise Capacity and Weight Reduction For Adolescents With Severe AutismDocument10 pagesThe Efficacy of A 9-Month Treadmill Walking Program On The Exercise Capacity and Weight Reduction For Adolescents With Severe AutismmarikosvaNo ratings yet

- Muscle Dysmorphia: Could It Be Classified As An Addiction To Body Image?Document6 pagesMuscle Dysmorphia: Could It Be Classified As An Addiction To Body Image?Clau CobosNo ratings yet

- Drive For Muscularity Behaviors in Male BodybuildeDocument12 pagesDrive For Muscularity Behaviors in Male BodybuildeIndrashis MandalNo ratings yet

- Final Paper ProposalDocument13 pagesFinal Paper Proposalseanchiu0812No ratings yet

- Rosen 1996Document12 pagesRosen 1996pilaralonsorobledoNo ratings yet

- Nemer Off 1994Document10 pagesNemer Off 1994saadsffggeettrgbfbfbftggrg ergrtertererefrerrNo ratings yet

- Does Self Esteem Moderate The Relation Between Gender and WeightDocument11 pagesDoes Self Esteem Moderate The Relation Between Gender and Weightmurilo rodriguesNo ratings yet

- Body Image Dissatisfaction: Gender Differences Eating Attitudes, Self-Esteem, and Reasons For ExerciseDocument16 pagesBody Image Dissatisfaction: Gender Differences Eating Attitudes, Self-Esteem, and Reasons For Exerciseiusti iNo ratings yet

- Study of Physical Fitness Index Using Modified Harvard Step Test in Relation With Body Mass Index in Physiotherapy StudentsDocument4 pagesStudy of Physical Fitness Index Using Modified Harvard Step Test in Relation With Body Mass Index in Physiotherapy StudentsUswatun HasanahNo ratings yet

- Improving Health Related Fitness in Adolescents The CrossFit Teens Randomised Controlled TrialDocument16 pagesImproving Health Related Fitness in Adolescents The CrossFit Teens Randomised Controlled TrialChi Chung CHANNo ratings yet

- La Actividad Fisica y Los HuesosDocument10 pagesLa Actividad Fisica y Los HuesosyatibaduizaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Different Response Formats On Ratings of Exerciser StereotypesDocument12 pagesThe Effect of Different Response Formats On Ratings of Exerciser StereotypesCarmarie Figueroa BenítezNo ratings yet

- Ivan 2Document5 pagesIvan 2Kamal Singh BhandariNo ratings yet

- Goal, Self EfficacyDocument17 pagesGoal, Self EfficacyAlexandra HNo ratings yet

- Amy FordDocument18 pagesAmy FordJaneNo ratings yet

- The Role of Stigmatizing Experiences MILKEWICZ ANNIS CASH HRABOSKYDocument13 pagesThe Role of Stigmatizing Experiences MILKEWICZ ANNIS CASH HRABOSKYGonzalo PaezNo ratings yet

- Building Strength: Strength Training Atti-Tudes and Behaviors of All-Women's and Coed Gym ExercisersDocument15 pagesBuilding Strength: Strength Training Atti-Tudes and Behaviors of All-Women's and Coed Gym ExercisersLaura Perez HoyosNo ratings yet

- Behavioral and Psychological Implications of Body Dissatisfaction: Do Men and Women Differ?Document14 pagesBehavioral and Psychological Implications of Body Dissatisfaction: Do Men and Women Differ?Jeral PerezNo ratings yet

- Effects of Physical Exercise in Older Adults With Reduced Physical Capacity Meta-Analysis of Resistance Exercise and MultimodalDocument12 pagesEffects of Physical Exercise in Older Adults With Reduced Physical Capacity Meta-Analysis of Resistance Exercise and MultimodalabcsouzaNo ratings yet

- Social Appearance Anxiety of Fitness ParticipantsDocument6 pagesSocial Appearance Anxiety of Fitness ParticipantsMumtaz MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Physical Self-Concept and Its Relationship To Exercise Dependence Symptoms in Young Regular Physical ExercisersDocument6 pagesPhysical Self-Concept and Its Relationship To Exercise Dependence Symptoms in Young Regular Physical ExercisersBarney MooreNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Gendered Nature of Weight Bias FIKKAN ROTHBLUMDocument18 pagesExploring The Gendered Nature of Weight Bias FIKKAN ROTHBLUMGonzalo PaezNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument19 pagesUntitledAli NassarNo ratings yet

- Body Image: Emilio J. Compte, Ana R. Sepúlveda, Yolanda de Pellegrin, Miriam BlancoDocument7 pagesBody Image: Emilio J. Compte, Ana R. Sepúlveda, Yolanda de Pellegrin, Miriam BlancoameliaNo ratings yet

- Body Composition and Bone Mineral Density Of.1 PDFDocument6 pagesBody Composition and Bone Mineral Density Of.1 PDFJoao Evandro NetoNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Muscle Dysmorphia Among Individuals Within Gym CommunitiesDocument9 pagesFactors Influencing Muscle Dysmorphia Among Individuals Within Gym Communitiesangelpode93No ratings yet

- Wys Sen 2016Document7 pagesWys Sen 2016José RodríguezNo ratings yet

- College Men's Perceptions of Ideal Body Composition and ShapeDocument12 pagesCollege Men's Perceptions of Ideal Body Composition and ShapeJoyna HeinzNo ratings yet

- Associations Among Mens Sexist Attitudes Objectification of Women and Their Own Drive For MuscularityDocument11 pagesAssociations Among Mens Sexist Attitudes Objectification of Women and Their Own Drive For MuscularityFelipe Corrêa MessiasNo ratings yet

- The Body Image Psychological Inflexibility Scale DevelopmentDocument8 pagesThe Body Image Psychological Inflexibility Scale DevelopmentAna Gómez EstebanNo ratings yet

- Avila - 2010Document9 pagesAvila - 2010Matheus SilvaNo ratings yet

- Do You Even Lift BroDocument12 pagesDo You Even Lift BroCody MeyerNo ratings yet

- Weight Watchers She Loses, He Loses: The Truth about Men, Women, and Weight LossFrom EverandWeight Watchers She Loses, He Loses: The Truth about Men, Women, and Weight LossRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- SR NFPA1583 v3Document8 pagesSR NFPA1583 v3nehemiasNo ratings yet

- Movement LibraryDocument72 pagesMovement LibraryKat ElvidgeNo ratings yet

- Bài tập bổ trợ anh 5 Smart Start Theme 1Document14 pagesBài tập bổ trợ anh 5 Smart Start Theme 1Phương ThảoNo ratings yet

- Screenshot 2024-01-13 at 14.51.57Document1 pageScreenshot 2024-01-13 at 14.51.57angelasaguirre573No ratings yet

- Estoy CansadoDocument100 pagesEstoy Cansadofujyreef100% (1)

- PE Narrative ReportDocument2 pagesPE Narrative ReportArjay L. PeñaNo ratings yet

- Cube PredatorDocument9 pagesCube PredatorDen KongNo ratings yet

- Muscular System NotesDocument6 pagesMuscular System NotesZussette Corbita VingcoNo ratings yet

- Adapted From The American Heart Association: Heart Rate Lab Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesAdapted From The American Heart Association: Heart Rate Lab Lesson PlansylNo ratings yet

- DLL Q3 Week3 March28 Apr1Document5 pagesDLL Q3 Week3 March28 Apr1Rica TanoNo ratings yet

- Cu 10 Cardiovascular SystemDocument88 pagesCu 10 Cardiovascular SystemRose MendozaNo ratings yet

- Bio 20 Unit D Lesson 1 PresentationDocument16 pagesBio 20 Unit D Lesson 1 PresentationcoffinNo ratings yet

- W9-Module-Exercises To Boost Leg PowerDocument7 pagesW9-Module-Exercises To Boost Leg PowerBSBA MM-FMNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Map Mapeh: Lifestyle and Weight ManagementDocument7 pagesCurriculum Map Mapeh: Lifestyle and Weight ManagementJulie Ann Talento100% (1)

- Clauses of Purpose and ContrastDocument14 pagesClauses of Purpose and ContrastKlaudyna Strzępka-BrożekNo ratings yet

- Safe Lifting ManualDocument46 pagesSafe Lifting ManualvsfchanNo ratings yet

- Exercise Prescriptions For Health & FitnessDocument26 pagesExercise Prescriptions For Health & FitnessMuhammad wahabNo ratings yet

- Muscular SystemDocument22 pagesMuscular SystemFiraol DiribaNo ratings yet

- Artigo 01:09Document6 pagesArtigo 01:09Rodrigo AlvesNo ratings yet

- Tahun 6 Bahasa InggerisDocument14 pagesTahun 6 Bahasa InggerisRuss XanderNo ratings yet

- Assignment 9 RobertsDocument25 pagesAssignment 9 Robertsapi-550046687No ratings yet

- Team SportsDocument8 pagesTeam SportsNicoco LocoNo ratings yet

- Complete Sports Training - Speed, Strength & Conditioning For Today's Athlete PDFDocument221 pagesComplete Sports Training - Speed, Strength & Conditioning For Today's Athlete PDFognjenNo ratings yet

- Pe 103 Module First Semester 2020-2021Document49 pagesPe 103 Module First Semester 2020-2021John Gerard EstorbaNo ratings yet

- AB Flyer LRDocument2 pagesAB Flyer LRRidwan WanNo ratings yet

- Consider Four Basic Food GroupsDocument3 pagesConsider Four Basic Food GroupsPrecious ViterboNo ratings yet