Professional Documents

Culture Documents

AL MEFTY Clinoidal Meningiomas

AL MEFTY Clinoidal Meningiomas

Uploaded by

Poncho CastillejoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

AL MEFTY Clinoidal Meningiomas

AL MEFTY Clinoidal Meningiomas

Uploaded by

Poncho CastillejoCopyright:

Available Formats

J Neurosurg 73:840-849,1990

Clinoidal meningiomas

OSSAMA AL-MEFTY, M.D.

Department of Neurosurgery, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, Mississippi

~" Anterior clinoidal meningiomas are frequently grouped with suprasellar or sphenoid ridge meningiomas,

masking their notorious association with a high mortality and morbidity rate, failure of total removal, and

recurrence. To avoid injury to encased cerebral vessels, most surgeons are content with subtotal removal.

Without total removal, however, recurrence is expected. Recent advances in cranial-base exposure and

cavernous sinus surgery have facilitated radical total removal.

The author reports 24 cases operated on with vigorous attempts at total removal of the tumor with involved

dura and bone. This experience has distinguished three groups (I, II, and III) which influence surgical difficulties,

the success of total removal, and outcome. These subgroups relate to the presence of interfacing arachnoid

membranes between the tumor and cerebral vessels. The presence or absence of arachnoid membranes depends

on the origin of the tumor and its relation to the naked segment of carotid artery lying outside the carotid

cistern. Total removal was impossible in the three patients in Group I, with postoperative death occurring in

one patient and hemiplegia in another. Total removal was achieved in 18 of the 19 patients in Group II, with

one death from pulmonary embolism. In the two patients in Group III, total removal without complications

was easily achieved.

KEY WORDS ~ meningioma 9 anterior clinoid 9 carotid cistern 9 cavernous sinus 9

sphenoid wing

C

USHING and EisenhardP 7 clearly distinguished to the classification system of Simpson, 47 the extent

meningiomas of the anterior clinoid as "those of tumor excision was either Grade I (complete mac-

of the deep or clinoidal third," and concur- roscopic removal of the tumor, with excision of its du-

rently, Vincent referred to them as "sphenocavernous ral attachment, and abnormal bone) or Grade II (com-

meningiomas. ''18 Despite this early recognition, these plete macroscopic removal of the t u m o r and of its

meningiomas are frequently grouped with suprasellar visible extensions, with coagulation of its dural at-

meningiomas or with meningiomas of the sphenoid tachment). Our experience with intraoperative anatom-

ridge, 6Aj'23"24~41`3jmasking their ominous course. They ical observation led us to distinguish three categories of

are second only to clival meningiomas in surgical mor- this tumor (Groups I, II, and III), each with a marked in-

tality and morbidity rates, failure of total removal, and fluence on the surgical difficulties, ability to achieve total

high rate of recurrence. Acknowledging that the best removal, and outcome. These groups relate to the pres-

chance for cure comes through radical total removal, ence of interfacing arachnoid membranes between the

most authors, both pioneer and modern, have been tumor and the cerebral vessels. The presence or absence

content with subtotal removal to avoid the devastating of this arachnoid membrane depends on the origin

sequelae of injury to the encased cerebral vessels; 6'9A7" of the tumor and its relation to the small intradural

22,31.43,51.56hence, repeated surgery and radiation therapy carotid artery segment lying outside the carotid cistern.

are frequently required. However, unless total removal

is achieved, detrimental regrowth is expected in the

majority of patients.l'~5~17'3747 Anatomical Considerations and Classification

Recent advances in cranial-base and cavernous si- As the carotid artery emerges from the cavernous

nus surgery have facilitated total removal, allowing re- sinus inferomedial to the anterior clinoid, it enters the

spectable mortality and morbidity rates for these subdural space to be vested in the carotid cistern. This

t u m o r s . 3"5"2~ This report describes 24 cases of cistern is bordered superiorly by the dura over the

clinoidal meningiomas operated on over a period of 7 anterior clinoid process and the frontal lobe, and infe-

years, from November, 1981, to October, 1988, with riorly by the dura covering the superior aspect of the

vigorous attempts at total removal (including tumor, cavernous sinus. The arachnoid does not follow the

dura, and bone) during the first operation. According internal carotid artery into the cavernous sinus space,

840 J. Neurosurg. / Volume 73/December, 1990

Clinoidal meningiomas

nor is it attached to the anterior clinoid process. A 1-

or 2-mm segment of naked internal carotid artery lies

between the investment of the carotid cistern and the

dura of the cavernous sinus, s9 This segment is not to

be confused with the extradural segment which lies

between the two rings anchoring the carotid artery as it

exits the cavernous sinus space. 2~ Medially, the carotid

cistern shares a wall with the chiasmatic cistern and is

bounded laterally by the medial temporal lobe and the

free margin of the tentorium. The inferior part of the

carotid cistern and the superior part of the interpedun-

cular cistern are in apposition, creating a single Lilie-

quist membrane.

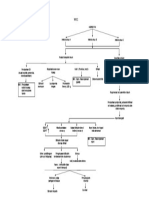

Group I

If the meningioma's origin is proximal to the end of

the carotid cistern (Group I), as is the case with a

meningioma originating from the inferior aspect of the F~G. 1, Artist's drawing of a Group I meningioma. The

anterior clinoid, the tumor will enwrap the carotid ar- tumor encases the carotid artery and its branches, with direct

attachment to the adventitia. The optic nerve maintains an

tery, directly adhering to the adventitia in the absence arachnoid plane from the chiasmatic cistern.

of an intervening arachnoid membrane (Figs. 1 and 2).

As the tumor grows, this direct attachment to the vessel

wall continues to the carotid bifurcation and along the remains intact, making microsurgical dissection feasible

middle cerebral artery, advancing the arachnoid mem- despite total encasement of the vessels (Figs. 3 and 4).

brane ahead of it. This situation makes dissecting the This observation correlates with reports in the literature

tumor from the carotid artery and the middle cerebral concerning the feasibility of tumor dissection despite

artery branches impossible and explains why some au- total vascular encasement. 4'2336

thors describe tumors invading the arterial wall. 2~ The optic chiasm and the optic nerves in both Group

I and II tumors are wrapped in the arachnoid mem-

Group H brane of the chiasmatic cistern, and dissecting them

Tumors of Group II originate from the superior and/ free from the tumor is relatively easy with a microsur-

or lateral aspect of the anterior clinoid above the seg- gical technique. In patients having undergone previous

ment of the carotid invested in the carotid cistern. Thus, surgery, the arachnoid membrane may be violated;

as the tumor grows, an arachnoid membrane of the subsequently, the dissection plane is lost and the tumor

carotid cistern and, distally, of the sylvian cistern sep- will be in direct contact with the adventitia. In this case,

arates the tumor from the arterial adventitia. Although the difficulty in Group II becomes similar to that in

the tumor engulfs the vessels, this arachnoid membrane Group I.

FIG. 2. A Group I meningioma. Left: Preoperative computerized tomography appearance. During sur-

gery, no arachnoid membrane was found and dissection of the middle cerebral and carotid arteries was

impossible. Right: Lateral carotid arteriogram demonstrating narrowing of the carotid and middle cerebral

arteries by the encasing tumor.

J. Neurosurg. / Volume 73/December, 1990 841

O. A1-Mefty

FlG. 3. A Group II meningioma. Left: Artist's drawing showing the tumor encasing the carotid artery

and its branches. An arachnoid membrane of the carotid cistern separates the tumor from the adventitia,

rendering dissection possible. The optic nerve maintains an arachnoid membrane from the chiasmatic cistern.

Right: Retouched operative photograph showing the optic nerve (II), the anterior cerebral artery (A1), the

middle cerebral artery (M~), and part of the internal carotid artery (C) dissected free from the encasing tumor

(T). Dissection continues on the proximal carotid artery and into the cavernous sinus. The dissection is

relatively easy, owing to the presence of the arachnoid membrane of the carotid cistern. R = retractor on the

frontal lobe.

Group I I I the superior temporal line on the opposite side. This

Tumors in Group III originate at the optic foramen, results in the superficial temporal artery coursing pos-

extending into the optic canal and the tip of the anterior terior to the incision while the branches of the facial

clinoid process. These tumors are usually small. The nerve are located anteriorly. Preservation of the super-

arachnoid membrane is present between the vessels and ficial temporal artery is important since the artery may

tumor but may be absent between the optic nerve and be needed for extracranial-intracranial (EC-IC) anasto-

the tumor (Figs. 5 and 6). mosis. The frontal branches of the facial nerve are

preserved by intrafascial dissection, as described previ-

ously by Ya~argil, et al. 6~

Operative Technique

Early in this series, the pterional approach was used Bone Removal

in seven patients and subfrontal approach in three. The zygomatic arch is dissected in subperiosteal fash-

Since 1985, we have exclusively used the orbitocranial ion, sectioned at the most anterior and posterior ends,

approach described elsewhere 2'3 for removal of these and displaced downward along with its attachment to

tumors. This approach provides the following advan-

tages: 1) it brings the surgeon closer to the deep-seated

lesion, allowing dissection over the shortest possible

distance; 2) it permits a surgical attack via multiple

routes: subfrontal, transsylvian, and subtemporal; 3) it

consists of a single bone flap, eliminating the need for

reconstruction and associated functional and anatom-

ical or cosmetic deficits; 4) its low basilar approach

alleviates brain retraction; and 5) it allows early inter-

ception of the tumor's blood supply through the sphe-

noid ridge, thus minimizing blood loss.

Positioning and Scalp Incision

The patient is placed supine and a spinal drainage

needle is inserted. The head is rotated 30* to 40 ~ to the

opposite side, dropped toward the floor, tilted 5~ to 10", FIG. 4. A Group II meningioma. Computerized tomogra-

phy scan (left) and arteriogram, anteroposterior view (right).

and fixed in the Mayfield headrest. The scalp incision Notice the arterial narrowing by the encasing tumor. Dissec-

is begun 1 cm anterior to the tragus, proceeding in a tion and tumor removal were facilitated by the presence of an

curvilinear fashion behind the hairline to the level of intervening arachnoid membrane.

842 J. Neurosurg. / Volume 73/December, 1990

Clinoidal meningiomas

FIG. 5. A Group III meningioma. Left: Artist's drawing showing the tumor originating in the optic

foramen. The tumor is small, separated from the carotid by the carotid cistern, but it extends into the optic

canal. Right: Retouched operative photograph showing the carotid cistern intact. The tumor (T) is small and

extends into the optic canal. II = optic nerve; C = carotid artery; R = retractor on the frontal lobe.

the masseter muscle. This maneuver allows a more of the olfactory nerve deters excessive frontal lobe re-

basal approach to the floor of the middle fossa, obvi- traction, otherwise resulting in avulsion of the olfactory

ating obstruction by the bulky temporal muscle. The nerve.

temporal muscle is retracted posteriorly and inferiorly,

exposing the junction of the zygomatic, sphenoidal, Tumor Debulking

and frontal bones. Removal of the orbitocranial flap Under the operating microscope, a plane of dissec-

then proceeds as described elsewhereY The sphenoid tion is established between the tumor and the frontal

ridge is drilled using a high-speed air drill. Drilling is and temporal lobes. Ultrasonic aspiration is used to

continued to completely remove the sphenoid ridge, debulk large tumors. Caution is used not to carry de-

unroofing the superior orbital fissure and removing the bulking close to the carotid artery or the middle cere-

anterior clinoid extradurally. This maneuver intercepts bral artery branches. Tumor removal around this area

the arterial feeders coming from branches of the middle is continued using only microsurgical dissection with

meningeal artery. It also assures removal of the involved bipolar coagulation and careful piecemeal removal by

bone at the insertion and prepares for exposure of the microdissection.

internal carotid upon entry to the cavernous sinus.

Arterial Dissection

Dural Opening and Tumor Exposure Once the tumor is debulked, the distal branches of

The dura mater is opened with a semicircular incision the middle cerebral artery are identified under high

centered on the pterion; an extension from the main magnification and, using microdissection, the tumor

incision is directed posteriorly and inferiorly to the floor capsule is removed from the arterial wall. Despite total

of the temporal fossa. Opening the dura under the

microscope provides a transitional adjustment of the

surgeon's dexterity from bone work to fine microsur-

gical dissection.

When the dura is opened, brain relaxation is achieved

by partial drainage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) through

the lumbar catheter. The arachnoid over the sylvian

fissure is opened, allowing separation of the temporal

and frontal lobes. The arachnoid opening is made and

extended on the frontal side to preserve the superficial

middle cerebral veins when possible. The relaxed frontal

lobe is held by a self-retaining retractor. Elevation of

the frontal lobe should be minimal - - a distance of 1.5

cm or less is adequate for tumor resection. The olfactory

nerve is located and preserved by dissecting it for some FIG. 6. Computerized tomography scan of a Group Ill me-

distance from the base of the frontal lobe. Preservation ningioma (arrow).

J. Neurosurg. / Volume 73/December, 1990 843

O. A 1 - M e f t y

encasement of these vessels, a tfiickened arachnoid Cavernous Sinus Involvement

membrane separated the tumor from the adventitia in When the tumor extends into the cavernous sinus,

Group II tumors. Dissection is carried to the bifurcation as it did in nine of our cases, proximal and distal control

of the carotid artery, removing the tumor from the of the carotid artery is necessary. Early in this series,

anterior cerebral artery. Careful dissection under high proximal control was achieved by exploring the inter-

magnification is continued to free the ventriculostriate nal carotid artery in the neck. More recently, this was

arteries, the perforator of the anterior cerebral artery, accomplished by exposing the intrapetrous segment of

and the internal carotid artery branches to the optic the carotid artery. The anterior clinoid is already re-

apparatus. Dissection becomes easier along the poste- moved, facilitating exposure of the superior aspect of

rior communicating artery and the anterior choroidal the cavernous sinus. The tumor is then removed

artery, since these two arteries have their own vesting through the superior or lateral wall of the cavernous

arachnoid membranes? 9 Dissection of the third nerve sinus, as reported elsewhere?

segment, prior to its entry in the lateral wall of the After gross tumor removal, the dura around the

cavernous sinus space, also becomes easier. anterior clinoid is evaporated with the CO2 laser. Any

When hemorrhage ensues from a tear in a cerebral further bone hyperostosis is drilled with the diamond

vessel, as it did in five of our cases, temporary vascular bit of a high-speed drill. Frequently, this change in the

clips (30 gm/mm) are applied distal and proximal to bone is actually invasion by the tumor. 9'~9 To avoid

the bleeding point, and the arterial wall is stitched with postoperative CSF leakage through the extended eth-

fine 10-0 sutures. Since the tumor may be supplied by moidal cell, a piece of fascia is applied over this area.

arterial twigs from the cerebral artery, the surgeon first The dura is then closed in a watertight fashion, the

confirms that they are tumor feeders and not hypotha- single bone flap positioned in place, and the skin closed

lamic perforators or the optic nerve blood supply. Thus, in two layers.

each arterial branch is dissected and followed to ascer-

tain its course. Particular attention is paid to spare the Summary of Cases

artery of Heubner and the vital branches of the stria-

tum. The Liliequist membrane was intact in all of our Case Material

cases of Group II tumors; consequently, removal of the Twenty-four cases qualifying as clinoidal meningi-

tumor from the interpeduncular fossa and the posteri- omas were operated on over a 7-year period, from

orly displaced basilar artery was usually easy. November, 1981, through October, 1988. There were

four other patients with the same pathology who did

Optic Nerve Dissection not have surgery. We excluded from the study me-

The optic nerves in these tumors are displaced in ningiomas with origins (as described intraoperatively)

several different ways. The optic nerve may be pushed on the tuberculum sellae, diaphragma sellae, planum

inferiorly and medially or elevated by the bulk of the sphenoidale, and middle and lateral sphenoid ridge, as

tumor coming between the carotid artery and the optic well as hyperostosing en plaque meningiomas. Of the

nerve. In seven of our cases, the optic nerve was totally 24 patients studied, 14 have been described in previous

engulfed, but in all cases the optic nerve maintained its publications. 4'5 Seventeen were operated on at King

arachnoid barrier formed by the wall of the chiasmatic Faisal Specialist Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia,

cistern. When the optic nerve is engulfed, it is easier to between November, 1981, and December, 1985, and

begin the dissection from the chiasm and continue seven were operated on at the University of Mississippi

forward toward the optic canal. Frequently, the tumor Medical Center between January, 1986, and November,

extends a bud into the optic canal, requiring unroofing 1988. The patients ranged in age from 26 to 76 years

of the optic canal and careful dissection of the tumor. (mean 52 years); there were seven men and 17 women.

The arterial supply to the optic nerve and chiasm is The symptoms of two women presented during preg-

preserved by the same method of dissection. Particular nancy. Four patients had previously undergone surgery

attention is paid to preserve the inferior group of arter- on their tumors.

ies, which are the sole blood supply to the decussating

fibers in the central chiasm. 8 Since occasional observa- Clinical Presentation

tions of visual recovery after total blindness have been Visual disturbances were present in 84% of cases,

reported, 4'33 the optic nerve was never sacrificed in our similar to the typical findings described for tumors at

patients to obtain better exposure of the tumor, even this site (initial unilateral visual loss). Five patients

in a totally blinded eye. experienced loss of vision on one side only; nine expe-

rienced optic atrophy, and six had papilledema. Fos-

Dissection of the Pituitary Stalk ter Kennedy syndrome was documented in only one

The pituitary stalk is easily recognized by its distinc- case. Four patients had impairment of the oculomo-

tive color and vascular network. It is usually displaced tor or trigeminal nerve, while seizure was present in

backward and to the opposite side. Arachnoidal cleav- three patients. Two patients were admitted in a coma-

age is present and careful dissection under the micro- tose state with giant tumors, and underwent emergen-

scope is successful. cy surgery. Visual loss preceded diagnosis by 2 to 44

844 J. Neurosurg. / Volume 73/December, 1990

Clinoidal meningiomas

months (average 25 months); headache preceded sur- tient had permanent diabetes insipidus. One patient

gery by an average of 68 months. was readmitted for repair of a CSF leak, and one

required a CSF shunt for hydrocephalus. One other

Radiographic Findings patient had a pulmonary embolism. The one semico-

Computerized tomography (CT) scans in all cases matose and one fully comatose patient at admission

revealed the presence of tumor and its extensions. Mag- both made impressive recoveries postoperatively.

netic resonance (MR) imaging with gadolinium en- The postoperative follow-up period ranged from 1 to

hancement was used in the last three cases. All patients 7 years (average 57 months). There was only one asymp-

underwent cerebral angiography to delineate the anat- tomatic recurrence which was observed to be without

omy of the cerebral circulation, arterial displacement, change on a CT scan 3 years later in the one Group II

encasement of major vessels, and blood supply. Angi- patient with subtotal removal. Two patients in this

ography revealed an associated internal carotid artery group had a second meningioma remote from the first

aneurysm in one patient. According to the classification (in the convexity), separated from the first operation by

mentioned above, 47 there were three Group I tumors, 3 and 6 years, respectively. These were removed surgi-

19 Group II tumors, and two Group III tumors. cally.

The carotid, middle cerebral, and anterior cerebral Only partial but extensive removal was possible in

arteries, as well as the optic apparatus, were all inti- all three Group I patients. One patient developed de-

mately involved with the tumor, being displaced, ad- layed postoperative vasospasm 7 days postoperatively,

herent, or totally engulfed. The carotid artery was totally which was confirmed by angiography, with a deterio-

encased in 11 patients, the branches of the middle rating ischemic neurological condition and eventual

cerebral artery were encased in seven, the anterior ce- death 4 months later. The second patient had postop-

rebral artery was encased in three, and the optic nerve erative hemiplegia and was treated for pulmonary em-

was encased in seven. Cavernous sinus invasion oc- bolism. A gradual increase in tumor size over a 3-year

curred in nine patients. period was documented by CT scanning. Radiation

therapy was administered upon the patient's refusal of

Operative Results a second operation. The third patient showed some

Total removal (tumor, dura, and bone), as judged by recovery of extraocular movement and received radia-

intraoperative inspection and confirmed by postopera- tion therapy, showing no changes on an M R image 24

tive CT scans (Fig. 7), was achieved in 18 of the 19 months later.

patients with Group II tumors; in the one exception a The two patients in Group III had no complications

small nub of tumor was left in the cavernous sinus. and showed neither clinical changes nor recurrence 7

There was one death 9 days postoperatively, due to months and 46 months postoperatively, respectively,

pulmonary embolism, in a patient who was in excellent according to the last available follow-up report of De-

condition and was ready to be discharged. One patient cember, 1985.

lost vision in one eye in which she had been able to

count fingers preoperatively from 1 ft. Preoperative Discussion

visual impairment improved in only two patients. One

patient had permanent third cranial nerve palsy. Two Distinguishing Clinoidal Meningiomas

patients had transient diabetes insipidus, and one pa- To subclassify anterior clinoidal meningiomas into

three groups may be surprising since many authors find

it difficult to distinguish clinoidal meningiomas from

those with more lateral attachment on the sphenoid

ridge, and prefer the notion of wide or small attach-

ment. 23-2s Stern 4~ has even advocated the concept of an

anatomical continuum of all meningiomas involving

the cranio-orbital junction.

In a discussion of meningiomas of the "clinoidal

third," Cushing and EisenhardP 7 stated, "it is not easy,

with certainty, to identify these cases in the literature."

This statement is still true today. Only a thorough re-

view of the literature can extract cases of anterior cli-

noidal meningiomas (Table 1). An analysis of these

cases leads to recognition of clinoidal meningiomas as

a separate entity with distinguishing clinical, radiologi-

cal, and surgical considerations. Cushing's series is a

FIG. 7. Contrast-enhanced computerized tomography typical example: of the 13 patients with anterior clinoi-

scans of a patient with a Group II clinoidal meningioma.

Left: Preoperative scan. Right: Scan obtained after total dal meningiomas, two were operated on transsphenoi-

removal of the tumor including intracavernous and optic dally in 1912 and 19 13, resulting in one operative death.

canal extensions. Notice the resection of the anterior clinoid. There was one other operative death. Only three pa-

J. Neurosurg. / Volume 73/December, 1990 845

O. A1-Mefty

TABLE 1

S u m m a r y of major surgical series of anterior clinoid meningiomas*

No. of Partial or Total Operative Recurrence + Known Symptomatic

Authors & Year

Cases Subtotal Removal Removal Death Eventual Death Recurrence

Cushing & Eisenhardt, 1938 1 l+(2)t 8 3 1+(1)# 5

Uihlein & Weyand, 1953 52 17 5

Holub, 1956 19 6 9

Olivecrona, 1967 47 15 32 11 3

Guyot, et al., 1967 13

Cook, 1971 11 3

Fischer, et al., 1973 6 2

Ugrumov, et al., 1979 16 14 2 4

Cophignon et al., 1979 6 4 2 0

Konovalov, et al., 1979 70 13

MacCarty & Taylor, 1979 47

Bonnal, et al., 1980 7 7 3

Pompili, et al., 1982 10 5

Ojemann, 1985 16 0 1

Hakuba, et aL, 1986 7 0

Jan, et al., 1986 19 6

Sekhar, et al., 1989 16 3 13 0

A1-Mefty, 1990 24 4 21 2

* Only available information is entered.

# Two patients were operated on transsphenoidally in 1912 and 1913, one of whom was an operative death.

tients had total removal. Recurrence with eventual strictly intracavernous, originating from within the cav-

death occurred in five patients. ernous s i n u s . 1~ The latter present with symptoms

Bonnal, et al., 9 described a similar series, with only and signs of cavernous sinus syndrome, and form a

subtotal removal possible in all seven patients and three separate entity; thus, we have excluded them from this

operative deaths. Pompili, e t a / . , 44 reported that only discussion.

two of their nine patients with inner sphenoid ridge

meningiomas (five of which were globus tumors) had T o t a l vs. S u b t o t a l R e m o v a l

excellent results, defined as total removal combined The surgical mortality rate associated with anteri-

with complete clinical remission and no clinical or ra- or clinoidal meningiomas has remained unacceptably

diological sign of recurrence. A striking difference in high. Uihlein and Weyand 53 reported a mortality rate

mortality and morbidity rates, failure of total removal, of 32% in 1953, comparable to a 42% mortality rate in

and recurrence is apparent whenever clinoidal menin- the series of Bonnal, et al., 9 in 1980. Repeatedly, the

giomas are compared with middle and lateral sphenoid operative cause is injury to the major cerebral ves-

tumors or with tuberculum sellae t u m o r s . 9A7'26'29'41'44'52 sels, 9'17'23'41'43'53 a risk that has forced an overwhelming

Recognizing these differences, Bonnal, et al.,9 classi- number of surgeons to accept and recommend subtotal

fied sphenoid ridge meningiomas into five groups (A to removal.6,9,~ L 17,22,23,31,45,51,52,56

E), with Group A in their classification representing the Most neurosurgeons have had the experience of care-

meningiomas discussed in this report. They described fully observing slow-growing tumors, and there have

clinoidal or sphenocavernous meningiomas en m a s s e been reports of patients who remain in satisfactory

as: "extended upward into the cranial cavity from the condition for years after partial removal of their tu-

dura of the cavernous sinus, of the anterior clinoid mors. 9'3~ On the other hand, the extent of surgical

process, and of the internal part of the sphenoidal removal is clearly the most determining factor in tumor

wings. They were in close contact with the internal recurrence and progression. 1,37.47,48In the series of Mir-

carotid artery and its branches, which were shifted, imanoff, et al., 37 sphenoid ridge meningiomas (with a

stretched, or embedded, and with the optic nerve and 28% rate of total resection in all sphenoid ridge loca-

tract. Bone was not involved, except for the anterior tions) recurred or progressed with a probability at 5 and

clinoid process, nor were the craniofacial cavities." 10 years of 34% and 54%, respectively. A second op-

They conceded that total removal of these meningi- eration carries a significantly higher mortality and fail-

omas is difficult even with the help of magnification ure r a t e . 35'37

and ultrasonic aspiration. This group is similar to the Uihlein and Weyand 53 have stated that "total re-

first category of Ojemann's sphenoid ridge menin- moval of these tumors is necessary to prevent recur-

gioma. 4~ rence." Cophignon, et al.,~5 stated the point clearly: "to

Although meningiomas of the anterior clinoid invade cure a patient from a spheno-orbital meningioma one

the cavernous sinus, there exist meningiomas that are has to remove the entire intradural tumor, all the

846 J. Neurosurg. / Volume 7 3 / D e c e m b e r , 1990

Clinoidal meningiomas

involved dura, the orbital tumor, and all the so-called S m a l l M e n i n g i o m a s o f the Anterior Clinoid

hyperostosis, opening the facial and intracranial sinuses, Cushing and Eisenhardt ~7 cited an early example of

if necessary." a small anterior clinoidal meningioma found at autopsy

Recent advances in skull-base exposure, anesthesia, and depicted in 1910 by Frotscher. Several cases of

cerebral protection, microsurgical techniques, imaging, these small meningiomas at the anterior clinoid (Group

and surgery of the cavernous sinus have assisted in III in our classification) can be found. We were able to

overcoming many of the formidable tasks in dissecting isolate 14 such c a s e s 9A6"21"4~ in addition to 22 others

and preserving the vital neural and vascular structures mentioned by Konovalov, et al. 32 These meningiomas

involved with these tumors. Embedded carotid and are characterized by severe loss of vision with optic

middle cerebral artery branches can be dissected free atrophy on one side, Prior to high-resolution CT and

under magnification by means of microsurgical tech- MR imaging, radiological studies were frequently nor-

niques. 42~ Extensions into the cavernous sinus mal and the tumor was usually found upon exploration

can be removed with preservation of the intracavernous for unexplained visual loss. This group of tumors is

carotid artery and the cranial nerves. 4'2~ Involved frequently reported to extend into the optic canal. They

bone can be extensively drilled away. T M Revasculari- are easily removed; however, visual prognosis remains

zation can be performed by EC-IC anastomosis, 38 a guarded because of the ischemic nature of the optic

saphenous vein graft, 5~ or direct reconstruction of the nerve deficit. These tumors are similar in clinical find-

carotid artery using an interposed venous graft 46 (T ings and surgical consideration to intracanalicular me-

Fukushima, personal communication, 1989), providing ningiomas, which have recently been reviewed by Wil-

a means to alleviate ischemia should injury beyond son, et al. 57

repair occur to major cerebral vessels. Delayed throm-

bosis of the internal carotid and middle cerebral arteries The Role o f Radiation Therapy

leading to stroke has been reported after surgery of The role of radiation therapy cannot be left unad-

these tumors, z343 We do not believe, however, that this dressed in a discussion of clinoidal meningiomas in

potential risk is frequent enough to be a deterrent to which subtotal removal or recurrence are prominent

arterial dissection. features. Waga, et al.,54 were unable to establish whether

Olivecrona4~ reported no recurrences in 26 surviving prophylactic radiation therapy was effective in prevent-

patients after complete removal of their medial ridge ing recurrence of benign meningiomas, while Yama-

meningiomas, with a postoperative follow-up period shita, et al., 58 concluded that irradiation of recurrent

of up to 25 years. Reviewing his long-term results in meningiomas is of little value, although it might occa-

patients with medial sphenoid ridge meningiomas, Oli- sionally be beneficial. Recent reports, however, have

vecrona concluded, "in the group where the tumor was advocated the effectiveness of radiotherapy in conjunc-

completely removed the functional results in the sur- tion with subtotal surgical excision. 7Az'55Hence, radia-

vivors were highly satisfactory, whereas in the incom- tion therapy is a viable adjuvant in treating nonremov-

pletely removed groups some patients lived for many able residual or recurring tumors. For smaller residual

years but the rate of recurrence was high and the results tumors, stereotactic radiotherapy is an attractive alter-

of secondary operation far from encouraging." Hence, native awaiting long-term results.

the controversy surrounding pursuit of total removal

does not question its value, but reveals the potentially

high price in risk of mortality and morbidity. Acknowledgments

The microsurgical technique has clearly improved The author is grateful to Julie Hipp for help in preparing

the incidence of operative mortality and morbidity and the manuscript and to Michael P. Schenk for the drawings.

the chance of total removal. 43233"4551 This is because

the surgeon is able to dissect adherent or encased struc-

References

tures due to the cleavage of the arachnoid membrane,

which is recognizable under the microscope. Hence, our 1. Adegbite AB, Khan MI, Paine KWE, et al: The recurrence

classification has a deep impact on surgical decision- of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J

making and outcome. When this membrane was absent Neurosurg 58:51-56, 1983

2. A1-MefiyO: Supraorbital-pterional approach to skull base

(Group I in our classification), dissection was impossi- lesions. Neurosurgery 21:474-477, 1987

ble; none of the tumors was removed totally and the 3. A1-Mefty O: Surgery of the Cranial Base. Boston: Kluwer,

outcome was a disappointment. In contrast, despite 1988

total encasement of arteries and nerves, total removal 4. A1-Mefty O, Holoubi A, Rifai A, et al: Microsurgical

was possible in Group II, with minimal morbidity. removal of suprasellar meningiomas. Neurosurgery 16:

Unlike other suprasellar meningiomas, recovery of vis- 364-372, 1985

ual deficits in clinoidal meningiomas is poor. ~4~ This 5. AI-Mefty O, Smith RR: Surgery of tumors invading the

cavernous sinus. Surg Neurol 30:370-381, 1988

implicates ischemia as the cause of visual loss in clinoi- 6. Andrews BT, Wilson CB: Suprasellar meningiomas: the

dal meningiomas rather than mere optic nerve com- effect of tumor location on postoperative visual outcome.

pression. J Neurosurg 69:523-528, 1988

J. Neurosurg. / Volume 73/December, 1990 847

O. A1-Mefty

7. Barbaro NM, Gutin PH, Wilson CB, et al: Radiation Neurochirurgie 32:129-134, 1986

therapy in the treatment of partially resected menin- 30. Jefferson A, Azzam N: The suprasellar meningiomas: a

giomas. Neurosurgery 20:525-528, 1987 review of 19 years' experience. Acta Neurochir Suppl 28:

8. Bergland R, Ray BS: The arterial supply of the human 381-384, 1979

optic chiasm. J Nearosarg 31:327-334, 1969 31. Kempe LG: Operative Neurosurgery. New York:

9. Bonnal J, Thibaut A, Brotchi J, et al: Invading menin- Springer-Verlag, 1968, Vol l, pp 109-118

giomas of the sphenoid ridge. J Neurusurg 53:587-599, 32. Konovalov AN, Fedorov SN, Failer TO, et al: Experience

1980 in the treatment of the parasellar meningiomas. Acta

10. Bradac GB, Riva A, Schrrner W, et al: Cavernous sinus Neurochir Suppl 28:371-372, 1979

meningiomas: an MRI study. Nenroradiology 29: 33. Koos WT, Kletter G, Schuster H, et al: Microsurgery of

578-581, 1987 suprasellar meningiomas. Adv Neurosurg 2:62-67, 1975

11. Brihaye J, Brihaye-van Geertruyden M: Management and 34. Lesoin F, Jomin M, Bouchez B, et al: Management of

surgical outcome of suprasellar meningiomas. Acta Neu- cavernous sinus meningiomas. Neurochirurgia 28:

rochir Suppl 42:124-129, 1988 195-198, 1985

12. Carella RJ, Ransohoff J, Newall J: Role of radiation 35. MacCarty CS, Taylor WF: Intracranial meningiomas:

therapy in the management of meningioma. Neurosur- experiences at the Mayo Clinic. Neurol Med Chit 19:

gery 10:332-339, 1982 569-574, 1979

13. Cioffi FA, Bernini FP, Punzo A, et al: Cavernous sinus 36. Malis LI: Tumors of the parasellar region. Adv Neurol

meningiomas. Neurochirurgia 30:40-47, 1987 15:281-299, 1976

14. Cook AW: Total removal of large global meningiomas at 37. Mirimanoff RO, Dosoretz DE, Linggood RM, et al: Me-

the medial aspect of the sphenoid ridge. Technical note. ningioma: analysis of recurrence and progression follow-

J Neurosurg 34:107-113, 1971 ing neurosurgical resection. J Neurosurg 62:18-24, 1985

15. Cophignon J, Lucena J, Clay C, et al: Limits to radical 38. Moritake K, Handa H, Yamashita J, et al: STA-MCA

treatment of spheno-orbital meningiomas. Acta Neuro- anastomosis in patients with skull base tumours involving

chir Snppl 28:375-380, 1979 the internal carotid artery - - haemodynamic assessment

16. Craig WM, Gogela LJ: Meningioma of the optic foramen by ultrasonic Doppler flowmeter. Acta Neurochir 72:

as a cause of slowly progressive blindness. J Nenrosurg 7: 95-110, 1984

44-48, 1950 39. Ojemann RG: Meningiomas: clinical features and surgical

17. Cushing H, Eisenhardt L: Meningiomas. Their Classifi- management, in Wilkins RH, Rengachary SS (eds): Neu-

cation, Regional Behaviour, Life History, and Surgical rosurgery. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1985, Vol l, pp

End Results. Springfield, II1:Charles C Thomas, 1938, pp 635-654

298-319 40. Ojemann RG: Meningiomas of the basal parapituitary

18. David M, Mahoudeau D: Les mrningiomes de la petite region: technical considerations. Ciin Neurosurg 27:

aile du sphrnoide (considerations anatomo-cliniques et 233-262, 1980

thrrapeutiques). Gaz Med France:l I 1-130, 1935 41. Olivecrona H: The surgical treatment of intracranial tu-

19. Derome PJ, Guiot G: Bone problems in meningiomas mors, in Olivecrona H, T6nnis W (eds): Handbuch der

invading the base of the skull. Clin Neurosnrg 25: Neurochirurgie. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1967, pp 1-301

435-451, 1978 42. Pellerin P, Lesoin F, Dhellemmes P, et ah Usefulness of

20. Dolenc VV: Anatomy and Surgery of the Cavernous the orbitofrontomalar approach associated with bone re-

Sinus. Wien: Springer-Veflag, 1989 construction for frontotemporosphenoid meningiomas.

21. Elsberg CA, Dyke CG: Meningiomas attached to the Neurosurgery 15:715-718, 1984

medial part of the sphenoid ridge with syndrome of 43. Pertuiset B, Farah S, Clayes L, et al: Operability of

unilateral optic atrophy, defect in visual field of the same intracranial meningiomas. Personal series of 353 cases.

eye and changes in sella turcica and in shape of interpe- Acta Neurochir 76:2-11, 1985

duncular cistern after encephalography. Arch Ophthalmol 44. Pompili A, Derome PJ, Visot A, et al: Hyperostosing

12:644-675, 1934 meningiomas of the sphenoid ridge p clinical features,

22. Fischer G, Fischer C, Mansuy L: Pronostic chirurgical des surgical therapy, and long-term observations: review of

mrningiomes de l'ar&e sphrnoidale. Neurochirurgie 19: 49 cases. Surg Neurol 17:411-416, 1982

323-346, 1973 45. Probst C: Possibilities and limitations of microsurgery in

23. Fohanno D, Bitar A: Sphenoidal ridge meningioma. Adv patients with meningiomas of the sellar region. Acta

Tech Stand Neurosurg 14:137-174, 1986 Neurochir 84:99-102, 1987

24. Grant FC: Intracranial meningiomas. Surgical results. 46. Sekhar LN, Sen CH, Jho HD, et al: Surgical treatment of

Surg Gynecol Ohstet 85:419-431, 1947 intracavernous neoplasms: a four-year experience. Neu-

25. Guthrie BL, Ebersold M J, Scheithauer BW: Neoplasms rosurgery 24:18-30, 1989

of the intracranial meninges, in Youmans JR (ed): Neu- 47. Simpson D: The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas

rological Surgery, ed 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1990, after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry

Vol 5, pp 3250-3281 20:22-39, 1957

26. Guyot JF, Vouyouklakis D, Pertuiset B: M6ningiomes de 48. Skullerud K, L6ken AC: The prognosis in meningiomas.

l'ar~te sph6noidale. Apropos de 50 cas. Neurochirurgie Acta Neuropathol 29:337-344, 1974

13:571-584, 1967 49. Stern WE: Meningiomas in the cranio-orbital junction. J

27. Hakuba A, Liu SS, Nishimura S: The orbitozygomatic Neurosurg 38:428-437, 1973

infratemporal approach: a new surgical technique. Surg 50. Sundt TM Jr, Piepgras DG, Marsh WR, et al: Saphenous

Neurol 26:271-276, 1986 vein bypass grafts for giant aneurysms and intracranial

28. Holub K: Intrakranielle meningeome. Acta Neurochir 4: occlusive disease. J Neurosurg 65:439-450, 1986

355-401, 1956 51. Symon L, Rosenstein J: Surgical management of supra-

29. Jan M, Baz6z6 V, Saudeau D, et al: Devenir des m6nin- sellar meningioma. Part 1: The influence of tumor size,

giomes intracrfiniens chez l'adulte. Etude r6trospective duration of symptoms, and microsurgery on surgical out-

d'une s6rie m6dico-chirurgicale de 161 m6ningiomes. come in 101 consecutive cases. J Neurosurg 61:

848 J. Neurosurg. / Volume 73/December, 1990

Clinoidal meningiomas

633-641, 1984 58. Yamashita J, Handa H, Iwaki K, et al: Recurrence of

52. Ugrumov VM, Ignatyeva GE, Olushin VE, et al: Parasel- intracranial meningiomas, with special reference to ra-

lar meningiomas: diagnosis and possibility of surgical diotherapy. Surg Neurol 14:33-40, 1980

treatment according to the place of original growth. Actn 59. Ya~argil MG: Microneurosurgery. Stuttgart: Georg

Neurochir Suppl 28:373-374, 1979 Thieme Verlag, 1984, Vol 1, pp 26-32

53. Uihlein A, Weyand RD: Meningiomas of anterior clinoid 60. Ya~argil MG, Reichman MV, Kubik S: Preservation of

process as a cause of unilateral loss of vision. Surgical the ffontotemporal branch of the facial nerve using the

considerations. Arch Ophthalmol 49:261-270, 1953 interfascial temporalis flap for pterional craniotomy.

54. Waga S, Yamashita J, Handa H: [Recurrence of menin- Technical article. J Neurosurg 67:463-466, 1987

giomas.] Neurol Med Chir 17:203-208, 1977 (Jpn)

55. Wara WM, Sheline GE, Newman H, et al: Radiation

therapy of meningiomas. AJR 123:453-458, 1975

56. Watts C: Sphenoid wing meningioma, in Long DM (ed): Manuscript received January 16, 1990.

Current Therapy in Neurological Surgery, 1985-1986. Accepted in final form March 30, 1990.

Toronto: CV Mosby, 1985, pp 14-16 Address reprint requests to: Ossama A1-Mefty, M.D., De-

57. Wilson WB, Gordon M, Lehman RAW: Meningiomas partment of Neurosurgery, University of Mississippi Medical

confined to the optic canal and foramina. Surg Neurol Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, Mississippi 39216-

12:21-28, 1979 4505.

J. Neurosurg. / Volume 73/December, 1990 849

You might also like

- Social Media PostsDocument72 pagesSocial Media PostsIrizh VillegasNo ratings yet

- Drugs in American Society (Erich Goode)Document542 pagesDrugs in American Society (Erich Goode)Arthur Rimbaud100% (1)

- Neck DissectionsDocument9 pagesNeck DissectionsMax FaxNo ratings yet

- Russia Import Law Guide LineDocument15 pagesRussia Import Law Guide LineerabbiNo ratings yet

- Parasagittal MeningiomaDocument51 pagesParasagittal MeningiomaAji Setia UtamaNo ratings yet

- Tumor BrainDocument5 pagesTumor BrainYuga Wisnutama WijayaNo ratings yet

- Anatomic Exposures For Vascular InjuriesDocument32 pagesAnatomic Exposures For Vascular Injurieseztouch12No ratings yet

- A Combined Epi-And Subdural Direct Approach To Carotid-Ophthalmic Artery AneurysmsDocument6 pagesA Combined Epi-And Subdural Direct Approach To Carotid-Ophthalmic Artery AneurysmsСергей НайманNo ratings yet

- Embolización Angiografica ArtDocument5 pagesEmbolización Angiografica ArtIsamar AlvarezNo ratings yet

- V Otava 2020Document10 pagesV Otava 2020Rainbow DashieNo ratings yet

- Meningioma TentorialDocument9 pagesMeningioma TentorialFiorella Alexandra HRNo ratings yet

- Multimodal Tretment of Intracranial Aneurysm: A. Chiriac, I. Poeata, J. Baldauf, H.W. SchroederDocument10 pagesMultimodal Tretment of Intracranial Aneurysm: A. Chiriac, I. Poeata, J. Baldauf, H.W. SchroederApryana Damayanti ARNo ratings yet

- Penetrating Neck Trauma - CameronDocument4 pagesPenetrating Neck Trauma - CameronVerónica VidalNo ratings yet

- Surgical Removal of Spinal Tumors: Article by James Willey, Cst/Cfa, and Mark V. Iarkins, M DDocument8 pagesSurgical Removal of Spinal Tumors: Article by James Willey, Cst/Cfa, and Mark V. Iarkins, M DLuwiNo ratings yet

- C2 RetropharyngealDocument11 pagesC2 RetropharyngealPeter Paul PascualNo ratings yet

- Foramen Magnum Meningiomas: Concepts, Classifications, and NuancesDocument9 pagesForamen Magnum Meningiomas: Concepts, Classifications, and NuancesBlessing NdlovuNo ratings yet

- Neurosurgical ManagementDocument9 pagesNeurosurgical ManagementMiky MikaelaNo ratings yet

- Technique: Median Sternotomy - Gold Standard Incision For Cardiac SurgeonsDocument8 pagesTechnique: Median Sternotomy - Gold Standard Incision For Cardiac SurgeonsRobert ChristevenNo ratings yet

- Carcinoma Maxillary Sinus : of TheDocument6 pagesCarcinoma Maxillary Sinus : of TheInesNo ratings yet

- (10920684 - Neurosurgical Focus) Falcotentorial Meningiomas - Clinical, Neuroimaging, and Surgical Features in Six PatientsDocument7 pages(10920684 - Neurosurgical Focus) Falcotentorial Meningiomas - Clinical, Neuroimaging, and Surgical Features in Six PatientsPutri PrameswariNo ratings yet

- Trauma de CuelloDocument8 pagesTrauma de Cuellolilym.alvarez.lNo ratings yet

- Suboccipital Craniectomy: Retromastoid Approach For Acoustic SchwannomaDocument12 pagesSuboccipital Craniectomy: Retromastoid Approach For Acoustic SchwannomaAtul JainNo ratings yet

- Gardner 2016Document10 pagesGardner 2016kwpang1No ratings yet

- Embolizacao 1Document10 pagesEmbolizacao 1Allan SiqueiraNo ratings yet

- Retrosigmoid Approach To Vestibular SchwannomasDocument5 pagesRetrosigmoid Approach To Vestibular SchwannomaskuntawiajiNo ratings yet

- Kumar 2013Document4 pagesKumar 2013Cirugía General Hospital de San JoséNo ratings yet

- KalangosDocument3 pagesKalangosCorazon MabelNo ratings yet

- (Journal of Neurosurgery) Neuroendoscopic Approach To Intraventricular LesionsDocument10 pages(Journal of Neurosurgery) Neuroendoscopic Approach To Intraventricular LesionsAniaNo ratings yet

- Nunez PPMDocument3 pagesNunez PPMmnandapurkarNo ratings yet

- Median Sternotomy ProcedureDocument5 pagesMedian Sternotomy ProcedureNelly NehNo ratings yet

- 5-Level Spondylectomy For en Bloc Resection of Thoracic Chordoma: Case ReportDocument9 pages5-Level Spondylectomy For en Bloc Resection of Thoracic Chordoma: Case Reportholt linNo ratings yet

- 2008 7 jns08124 PDFDocument10 pages2008 7 jns08124 PDFZeptalanNo ratings yet

- A Technique For Safe Internal Jugular Vein Catheterization: G. Sarr, MarylandDocument2 pagesA Technique For Safe Internal Jugular Vein Catheterization: G. Sarr, MarylandAriyoko PatodingNo ratings yet

- 2016 3 Spine151538 PDFDocument6 pages2016 3 Spine151538 PDFRhonaz Putra AgungNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Third Ventricular Tumors - The Neurosurgical AtlasDocument14 pagesIntroduction To Third Ventricular Tumors - The Neurosurgical AtlasAlves de MeloNo ratings yet

- 5) Total Mesorectal Excision - 40 Years of Standard of Rectal Cancer SurgeryDocument6 pages5) Total Mesorectal Excision - 40 Years of Standard of Rectal Cancer SurgeryAnnaKnakNo ratings yet

- Modified Unilateral Approach For Mid-Third Giant Bifalcine Meningiomas: Resection Using An Oblique Surgical Trajectory and Falx WindowDocument6 pagesModified Unilateral Approach For Mid-Third Giant Bifalcine Meningiomas: Resection Using An Oblique Surgical Trajectory and Falx WindowYusuf BrilliantNo ratings yet

- Exemplu 4Document4 pagesExemplu 4Pavel SebastianNo ratings yet

- Abordaje Infratentorial Supracerebeloso Lateral Extremo - Cómo Lo HagoDocument4 pagesAbordaje Infratentorial Supracerebeloso Lateral Extremo - Cómo Lo HagoGonzalo Leonidas Rojas DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Ann Burns and Fire Disasters 29 209Document6 pagesAnn Burns and Fire Disasters 29 209fabian hernandez medinaNo ratings yet

- Supraglottic LaryngectomyDocument5 pagesSupraglottic LaryngectomyCarlesNo ratings yet

- Brown 1990Document8 pagesBrown 1990PingKikiNo ratings yet

- Carotid Artery LigationDocument62 pagesCarotid Artery LigationPriya Arul97No ratings yet

- Meningioma With Cystic Change Mimicking Hemangioblastoma: SciencedirectDocument5 pagesMeningioma With Cystic Change Mimicking Hemangioblastoma: SciencedirectKhương Hà NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Surgical Management of Giant Intracranial Meningiomas: Original ArticleDocument6 pagesSurgical Management of Giant Intracranial Meningiomas: Original ArticleAdel SalehNo ratings yet

- Hemagioma SCDocument5 pagesHemagioma SCCelebre MualabaNo ratings yet

- Rinotomi LateralDocument5 pagesRinotomi Lateralyunia chairunnisaNo ratings yet

- GeyikDocument8 pagesGeyikPGY 6No ratings yet

- J Minim Invasive Surg Sci 2012 1 2 77 79Document3 pagesJ Minim Invasive Surg Sci 2012 1 2 77 79MeliNo ratings yet

- 701 2022 Article 5445Document9 pages701 2022 Article 5445PeyepeyeNo ratings yet

- Huge Cervical Swelling Hiding A Tonsillated Cyst About 01caseDocument3 pagesHuge Cervical Swelling Hiding A Tonsillated Cyst About 01caseInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Baker 1950Document15 pagesBaker 1950Cotaga IgorNo ratings yet

- Advances in Open Microsurgery For Cerebral Aneurysms: TopicDocument10 pagesAdvances in Open Microsurgery For Cerebral Aneurysms: TopicHristo TsonevNo ratings yet

- Pseudoaneurysm of Internal Carotid Artery: N.V. Beena, M.S. Kishore, Ajit Mahale and Vinaya PoornimaDocument3 pagesPseudoaneurysm of Internal Carotid Artery: N.V. Beena, M.S. Kishore, Ajit Mahale and Vinaya PoornimaGordana PuzovicNo ratings yet

- Aortaresektion Marulli 2015Document6 pagesAortaresektion Marulli 2015t.krbekNo ratings yet

- Modified & Radical Neck Dissection: Johan FaganDocument18 pagesModified & Radical Neck Dissection: Johan FaganGeorgetaGeorgyNo ratings yet

- Blunt Traumatic Diaphragmatic Hernia: Pictorial Review of CT SignsDocument7 pagesBlunt Traumatic Diaphragmatic Hernia: Pictorial Review of CT SignssorafaiiNo ratings yet

- Orbitozygomatic Approach To Skull Base Lesions: Kafatabani Lezyonlarina Orbitozigomatik YaklasimDocument5 pagesOrbitozygomatic Approach To Skull Base Lesions: Kafatabani Lezyonlarina Orbitozigomatik YaklasimGaurav MedikeriNo ratings yet

- Seio CavernosoDocument19 pagesSeio CavernosoIngrid GomesNo ratings yet

- Van Love Ren 1991Document8 pagesVan Love Ren 1991SebastianNo ratings yet

- Umana2019 PDFDocument4 pagesUmana2019 PDFIgor PiresNo ratings yet

- Abordaje Cigomato TransmandibularDocument14 pagesAbordaje Cigomato TransmandibularRafael LópezNo ratings yet

- Surgery of the Cranio-Vertebral JunctionFrom EverandSurgery of the Cranio-Vertebral JunctionEnrico TessitoreNo ratings yet

- Ivo Fabijanić, Frane Malenica - Abbreviations in English Medical Terminology and Their Adaptation To CroatianDocument35 pagesIvo Fabijanić, Frane Malenica - Abbreviations in English Medical Terminology and Their Adaptation To CroatianFrane MNo ratings yet

- Form B - Other Jobs - High - V High Risk TBDocument8 pagesForm B - Other Jobs - High - V High Risk TBMorshed HumayunNo ratings yet

- Eac HemaDocument150 pagesEac HemaRemelou Garchitorena AlfelorNo ratings yet

- Các Topic Thi Nói Anh Văn Lớp 6: Vndoc - Tải Tài Liệu, Văn Bản Pháp Luật, Biểu Mẫu Miễn PhíDocument2 pagesCác Topic Thi Nói Anh Văn Lớp 6: Vndoc - Tải Tài Liệu, Văn Bản Pháp Luật, Biểu Mẫu Miễn PhíVõ ToạiNo ratings yet

- BLOOD PRESSURE Vs HEART RATE From American Heart AssociationDocument2 pagesBLOOD PRESSURE Vs HEART RATE From American Heart AssociationSyima MnnNo ratings yet

- Work-Experience-Sheet CSC Form 212Document5 pagesWork-Experience-Sheet CSC Form 212Marc AbadNo ratings yet

- What Is Operant Conditioning - Definition and ExamplesDocument10 pagesWhat Is Operant Conditioning - Definition and ExamplesAlekhya DhageNo ratings yet

- The Use of Cerebrolysin and Citicoline in AutismDocument10 pagesThe Use of Cerebrolysin and Citicoline in AutismAamir Jalal Al-MosawiNo ratings yet

- TSC Operating Standards V5 Final - HighlightedDocument44 pagesTSC Operating Standards V5 Final - HighlightedGerman Ramirez IbarraNo ratings yet

- Process Validation of PharmaceuticalsDocument24 pagesProcess Validation of PharmaceuticalsMankaran Singh100% (1)

- WOC HepatitisDocument1 pageWOC Hepatitisdestri wulandariNo ratings yet

- Bronze Alloys MsdsDocument11 pagesBronze Alloys MsdssalcabesNo ratings yet

- Green Mo RevolutionDocument47 pagesGreen Mo RevolutionBettyNo ratings yet

- Lawson Products, Inc - Heavy Duty Chain LubricantDocument7 pagesLawson Products, Inc - Heavy Duty Chain Lubricantjaredf@jfelectric.comNo ratings yet

- Effects of Exercise Therapy For Pregnancy Related.2Document7 pagesEffects of Exercise Therapy For Pregnancy Related.2Dewi PutriNo ratings yet

- 2 - Teste DiagnósticoDocument4 pages2 - Teste DiagnósticomartarcpNo ratings yet

- Catholic Community Services Southwest Job Announcement: Page 1 of 4Document4 pagesCatholic Community Services Southwest Job Announcement: Page 1 of 4UWTSSNo ratings yet

- 1 PDFDocument94 pages1 PDFJohn Louie SolitarioNo ratings yet

- Factors Related With School ReadinessDocument2 pagesFactors Related With School ReadinessRizaru RinarudeNo ratings yet

- Predictors of Positive Blood Culture and Deaths Among Neonates With Suspected Neonatal Sepsis in A Tertiary Hospital, Mwanza-TanzaniaDocument9 pagesPredictors of Positive Blood Culture and Deaths Among Neonates With Suspected Neonatal Sepsis in A Tertiary Hospital, Mwanza-Tanzaniafasya azzahraNo ratings yet

- Persuasive SpeechDocument4 pagesPersuasive SpeechRyan RanaNo ratings yet

- Concealed Carry Form LouisianaDocument9 pagesConcealed Carry Form LouisianaNicholas LeonardNo ratings yet

- EPG Health Report The Future of HCP Engagement Impact 2023Document73 pagesEPG Health Report The Future of HCP Engagement Impact 2023paulilongereNo ratings yet

- Monitoring and Evaluation ME PlanDocument12 pagesMonitoring and Evaluation ME PlanMirAfghan GhulamiPoorNo ratings yet

- Biostatistics 203. Survival Analysis: YhchanDocument8 pagesBiostatistics 203. Survival Analysis: YhchanselinblueNo ratings yet

- SEAFDEC/AQD Institutional Repository (SAIR) : This Document Is Downloaded At: 2013-07-02 07:11:51 CSTDocument53 pagesSEAFDEC/AQD Institutional Repository (SAIR) : This Document Is Downloaded At: 2013-07-02 07:11:51 CSTKarl KiwisNo ratings yet

- Terrell Owens Bands Arm ExerciseDocument6 pagesTerrell Owens Bands Arm Exerciseflash30No ratings yet