Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Transmutation of Rhetoric

Transmutation of Rhetoric

Uploaded by

Jl WinterOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Transmutation of Rhetoric

Transmutation of Rhetoric

Uploaded by

Jl WinterCopyright:

Available Formats

The Transmutation of Rhetoric in "Edward II"

Author(s): C. P. Seabrook Wilkinson

Source: Shakespeare Bulletin , SPRING 1996, Vol. 14, No. 2 (SPRING 1996), pp. 5-7

Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26352999

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to Shakespeare Bulletin

This content downloaded from

185.102.149.86 on Wed, 01 Dec 2021 08:50:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SPRING 1996 SHAKESPEARE BULLETIN - 5

The Transmutation of Rhetoric in Edward II

By C. P. Seabrook Wilkinson

Though certain scenes in Christopher

Marlowe's Edward II, notably that of the protago

nist's execution, have never wanted for eloquent

admirers, criticism long disparaged its verse, only

Gaveston's set piece speeches in act one being

considered up to the playwright's usual standard.

Recently, some have argued that he deliberately

denies himself the luxury of poetic rhetoric to aim at

effects even his mighty line could not achieve. The

abandonment of poetic diction in act five is merely

the most conspicuous of a number of innovations

and adjustments whereby, aptly in view of his plot,

the playwright practices this self-denial. In Edward

II, Marlowe compensates for the sacrifice of his

wonted verbal richness as rhetoric is transmuted

into other forms of persuasive expression, some

verbal and some independent of words.

Marlowe could not dispense with speech alto

gether—English drama would have to wait until

Beckett for that—but Edward II is conspicuously

short on speechmaking, its only virtuoso perfor

mances being those of Gaveston, which John Cutts

designates "speeches of sexpectation" (204) and

which traditionalist critics such as J. B. Steane,

constricted by narrow definitions of poetic merit,

find oases in an arid prosody.1 Frequent confusion

of language faithfully reflects the moral and intel

lectual confusion of an England whose denizens

exhibit Brownian motion in a moral vacuum where

language is contingent, not iconic. Debra Belt's

claim that the play "relentlessly embodies ... a

struggle for rhetorical control" (138) suggests that Simon Russell Beale as Edward II in Royal Shakespeare Company's 1990 Edward II,

language is used by playwright and by characters by Christopher Marlowe. Photo by Michael LePoer Trench.

chiefly as a means of manipulation. As too many

critics forget, Edward II was designed as a vehicle not for critics but for his brother: Edward's words are shorn of their poetry as the oblique

actors, for whom word is but cue to performance. reference to death becomes explicit.

Realizing that true power lies elsewhere, the characters voice a There is a marked shift towards greater explicitness in language and

growing skepticism about the efficacy of speech. Edward, commenting onprop in the final act, in which Marlowe consistently realizes the possibilities

the "devices" Lancaster and Mortimer have devised for the "statelyof his new approach to the interiorization of character. The enforced

triumph" celebrating the return of Gaveston, remarks the conflicting abdication, a public ceremony, necessarily retains a primary reliance on

signals of words and emblems: "Can you in words make showe of amitie, language; in the execution scene, a private and irregular action, language

/ And in your shields display your rancorous minds?" (2.2.32-33).2 Al is overshadowed by stage business. Chief character and creator wean

though Brecht perversely recasts Mortimer as a classical scholar in histhemselves of their poetry synchronically—it is at the level of language,

adaptation,3 there are no intellectuals in Edward II. Briefly a philosopher rather than in terms of any supposed sexual identification, that Edward and

manqué at Neath (4.7.16-25), Edward can no more sustain this role than he Marlowe most significantly share. In the abdication scene, the prop's the

has that of king or homosexual partner. The shallowest major character, thing in the long hiatus as Edward wavers about acquiescence. The

early marginalized and eliminated before act three, Gaveston alone, appro cornered King's commentary on his manipulation of props also manipu

priately, speaks in the luxuriant fashion of his early speeches. His syntax lates the response of his audience within the play: "See monsters see, ile

is as foreign to the world of the play as he, in his Italian guise, is to the noblesweare my crowne againe" (5.1.74). Edward's penchant for explaining his

he threatens to supplant. Unnaturally florid language is natural to him, and emblematic or symbolic actions survives the shock of abdication, for near

his verbal prowess proclaims the inability of the play's only accomplished the end of the scene he comments while tearing Mortimer's letter: "Well

rhetorician to attain political power or psychological purchase. An element may I rent his name, that rends my hart" (5.1.140). After the main part of

of Marlovian self-parody informing Gaveston's first speech, fitting the his performance, the teasing juggling of options expressed in the settling

prevailing homosexual stereotype, is ironic in that much of the criticism and removal of his crown, Edward slumps, when urged by Leicester to

leveled at the play's verse has been occasioned by its author's conspicuous recall the envoys, into a confession of impotence: "Call thou them back, I

failure to conform to his own stylistic stereotype. have no power to speake" (5.1.93). Having relinquished his prop, the

Allowing situations and their sequencing to outweigh the local interest crown, Edward now abdicates his right to make decisions and to give

of poetic merit evinces a rethinking of dramatic priorities. Even charactercommands. Even Steane recognizes that, on occasion, the lack of poetry is

istic speech now varies according to situation, as Marlowe creates fullyattributable not to imaginative exhaustion but to coherent dramatic aims

rounded if morally lopsided characters, at least three of whom-Edward, (213). Edward's verbal incapacity in the abdication scene becomes richly

Mortimer, and Gaveston—have distinctive styles of speaking. The dramaticresonant, as it had been at the beginning of act three, when Spencer speaks

but denuded poetry often achieves an eloquence transcending rhetorical on behalf of the traumatized King in a speech that commencing in the

flourishes, as in Edward's reaction to marching orders: "Whether you will, optative~"Were I king Edward, Englands soveraigne" (3.1.10)—modu

all places are alike, / And every earth is fit for buriall" (5.2.144-45). In a lates to the imperative—"Strike off their heads, and let them preach on

work in which the skewed parallel is pervasive, the King's words are echoed poles" (3.1.20).

by his brother Kent at the end of the following scene: "I, lead me whether The authority of the verse is bound up with Edward's crumbling sense

you will, even to my death" (5.3.66). Fittingly, Kent is less affecting than of self. If he is no longer a king, he can no longer speak as a king, and he

This content downloaded from

185.102.149.86 on Wed, 01 Dec 2021 08:50:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

6 - SHAKESPEARE BULLETIN SPRING 1996

has not yet begun to learn how to speak as a mere mortal. Deprived doings ofof thethe

plot. Much of what happens in act five reworks earlier events

office that has defined him, he has no concepts by which to and steer in his

speeches, as Sarah Munson Deats recognizes in comparing the "chris

nightmarish incarceration. In commenting on the confused world tening" of theBishop of Coventry in the opening scene with Edward's

of the

play, Claude Summers floats eminently postmodern notions of the

shaving elowater in 5.3." An inverted ritual, albeit of a sexual nature,

in ditch

quence of incoherence and the allure of extratextuality: "Where is centraldissem

to the play's most celebrated moment, Edward's murder, which

bling is the norm, the most powerful preaching is the silence that emanates

is also the most intricate instance of verbal and visual repetition, utilizing

from bodyless heads set upon poles 'for trespasse of their tongues'... and

all of the elements discussed above—"characteristic" speech, parallels to

the incoherent shriek of pain that issues from the hapless king and otherraises

scenes, the

props, and props that double as symbols. That the punishment

town" (230). meted to Edward somehow fits the "crime" that cost him his kingdom has

As if to emphasize the unreliability of language, the dénouement turns become a critical commonplace, but not all have seen beyond the sexual

on an instance of syntactical ambiguity that mirrors the moral confusion, implications to find the execution a complex completion of thematic

Mortimer's unpointed letter. Intended to be ingeniously ambiguous, this development and technical innovation as well. The action is so extreme, so

missive is actually the most "speaking" prop of all. Lightborn, who does not obscene, that Edward's final soliloquy is reduced to a prolonged scream of

bel ieve in anything other than his own virtuosity (in this as in other respects inexpressible agony. The blank verse line could never capture the terrible

paralleling Gaveston), fails to realize that the significance of this text is cruelty of this occasion; here, crucially, Marlowe must move beyond

extratextual, that the bearer of this ambiguous message will be unambigu words. Again, Edward and his creator are in step. Already in act three, the

ously dispatched: "And by a secret token that he bears, / Shall he be King had developed an understanding of showing as a form of telling, but

murdered when the deed is done" (5.4.19-20). As they influence the action, there gesture, framed by commentary, was not allowed to replace words

indeed often generate it, letters become more than props. altogether: "Yet ere thou go, see how I do devorce Embrace Spencer. /

All of the most striking props are employed in the latter part of the play, Spencer from me" (3.2.176-77).

their increased prominence serving to offset the effects of verbal austerity Marlowe's innovations in Edward II are the more remarkable in view

and lack of ceremony. David Bevington and James Shapiro rightly stress of the commercial and managerial constraints under which he labored.

their importance in the execution scene, in which Edward's reduction "to Possibly some of his striking shifts away from reliance on his mighty line

appalling physical indignity is... a shocking affront to proper ceremonial originate not in aesthetic restlessness but in pragmatism. Tucker Brooke

form and a reminder of the impermanence of all worldly prosperity. The long ago stressed the significance of the fact that Edward II was not

numerous hand properties and movable stage objects of this play reinforce performed by Henslowe's company and, therefore, would not have had

the point" (275). It is plausible to view the featherbed as a prop with Edward Alleyn in the cast, speculating that "the great increase in vivacity

symbolic overtones, suggestive of the sensual delights with which Gaveston of dialogue at the cost of sounding rhetoric" attests to "an almost painful

tempted Edward and initiated his fall, but it is less easy to find the table regard for the interest of a company not possessed of any star performer but

emblematic, as Charles Masington does (111). Any alert audience ought to capable of good ensemble effects" (48).

appreciate a symbolic dimension in another prop utilized earlier in this Whatever features may have been dictated by such considerations,

scene, the torch with which Lightborn, "ironically providing a visual pun Marlowe achieves a deliberate and astonishing self-restraint, the more

on his own name" (Zucker 139), goes to summon Edward from his remarkable in that, uniquely among his plays, the subject matter encom

cesspool. This torch is representative of a group of props that are also passes his own presumed sexuality. For John McElroy, the play's starkness

embodied symbols. The torch earlier extinguished by Matrevis (5.3.47) for reflects "a conscious stylistic choice, a self-imposed limitation" (208). The

a practical reason-to diminish further the chances of rescuers recognizing self-limiting aspect ironically echoes a theme of limitation traceable

the newly-barbered king-doubles as a symbolic extinction of hope. throughout Marlowe's dramatic output, in which overreaching protago

The characters' response to symbols is often revealing. As King, nists batter their egos against unacknowledged limitations. Marlowe's self

Edward is a symbol, and even if he does not fully appreciate this aspect of denying ordinance itself illustrates the theme of limitation: he is revealing

his own role, he has some understanding of the way symbols work. James at once the limitations of Edward's character and of kingship, the limita

Voss finds his "capacity to respond imaginatively and emotionally to tions of his own mature style, and the limited use of any language in

primarily symbolic formulations" (258) one of the salient differences expressing the most profound emotions.

between him and Mortimer, that robust literalist of the imagination. The What is there to build on in the new techniques with which Marlowe

soliloquy the latter delivers after Lightborn's exit (5.4.48-72) is the here experiments? Obviously, there is much from which Shakespeare

measure of the man, crowded with happenings, strikingly devoid of might and did learn, though some have been troubled by the lack of

thought. In the abdication scene, Edward has tried, and failed, to think; resemblance between Marlowe's history play and early Shakespeare,

"proud Mortimer" is too arrogant even to try—he can only gloat. particularly Richard II with its strong parallels in plot. Steane, finding in

The reintroduction or transformation of a prop can be crucial. Almost Edward II "the Shakespearean working ... in embryo" (209), speaks for

every modern critic has noticed the way in which the iron spit is a correlative a whole befuddled generation in adumbrating the dreary notion that

of the phallic delights touted in Gaveston's first speech. Bevington and Marlowe has merely been subcontracted to drive the pilings for

Shapiro suggest that "the huge jewel Mortimer describes in Gaveston's Shakespearean tragedy.

Tuscan cap' is recalled in Edward's final moments" (274), when the King In Edward II, verbal yields to visual imagery as poetic suggestiveness

proffers his last physical link with the status of which he has been is effectively superseded by symbolic props. Already in act two, when the

systematically divested, saying simply, "Onejewell have I left, receive thou fate of Gaveston hangs in the balance, the despised favorite is becoming a

this" (5.5.84). A king no more, Edward is for once acting the part of aking, prop as his captors discuss him as though he were inanimate. In this scene

it being customary for a monarch under sentence of death to reward the within a scene (2.5.50-70), the audience must attend to the reactions of the

executioner. This vestigial jewel not only recalls his royal status, and the characters, not to their unexpressive declared sentiments, which have all

conspicuous jewel in Gaveston's cap, but also suggests Edward's "eternal been heard before. The declining importance of language itself is most

jewel," the soul he is also about to surrender, in one of Marlowe's grimmest striking in act five, in which the two most eloquent moments are wordless.

ironies, to Lightborn, or Lucifer, who is first summoned by Mortimer At 5.1.85, the stage direction reads laconically: "The King rageth." This

("Lightborn, / Come forth"-5.4.20-21) as the evil spirit he is. stage direction is quite unlike earlier ones in which the action is to proceed

Often props illuminate the characters with whom they are associated. ad libitum : "Alarums, excursions, a great fight, and a retreate" (3.1.184)

The "unpointed" letter suggests the similarly "unpointed" nature of Ed and, introducing 4.5, "Enter the King, Baldock, and Spencer the sonne,

ward's character and actions. First apawn and then a prop, the King is acted flying about the stage." It is an invitation to the actor to improvise

upon for most of the play. By act five, he has lost his independence of action, emotions the playwright, recognizing that at this juncture Edward would be

while retaining an individuality of speech, a chastened simplicity of diction incapable even of semicoherent speech, has not attempted to put into words.

which becomes him. In the execution scene, Edward's somewhat steadier Exhibitionist that he is, Gaveston alone speaks the mighty Marlovian

utterance betokens a new maturity grounded in partial awareness of his line with consistency. This is appropriate, as it is that he stands literally and

situation. By this time, the deposed King has become a prop as well, a symbolically aside during his friend's first altercation with the barons

movable property unceremoniously shunted from dungeon to dungeon. He (1.1.74-133), for, of all the characters, he is most detached from the somber

is literally a prop in the funeral procession his son stages in the final scene, realities of power and intimidation. Just as Edward is deprived of Gaveston,

in which Mortimer, reduced to a severed head, is even more radically the play is soon deprived of his favorite's gorgeous but peripheral rhetoric.

dehumanized. He and Edward have traded places again: Mortimer is That the seduction scene with Lightborn is virtually a mimed version of

degraded as the murdered King's violated royalty is reaffirmed in dignified Gaveston's first "sexpectation" speech shows how power has shifted from

ceremony. Restored to royal status, Edward resumes symbolic stature. rhetoric. The execution scene becomes the crux of Marlowe's innovations

Parallel scenes give an ironic structural coherence to the disordered in speech and stage business; it has no counterpart in Elizabethan drama,

This content downloaded from

185.102.149.86 on Wed, 01 Dec 2021 08:50:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SPRING 1996 SHAKESPEARE BULLETIN - 7

and indeed so shocking is its action that scholars continue to dispute of the scene, Roger Sales is becomingly cautious in

bowdlerization

whether it could ever have been staged.5 The world in which Edward

eschewingdies

certainty, concluding that "Elizabethan productions would

is one not of poetry but of obscene parody, a change faithfully reflected in staged the execution as it was recorded by Holinshed" (116).

probably have

language, gesture, and props. Words themselves, elaborate or stark, have

been marginalized. The playwright, with the courage signally lacking in his Works Cited

protagonist, does change his ways, the style by which he breathes. Like

Lightborn, one of his most compellingly rebarbative creations,Bartels,

Marlowe Emily C. Spectacles of Strangeness: Imperialism, Alienation,

has in Edward II found "a better way." and Marlowe. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania?, 1993.

Belt, Debra. "Anti-Theatricalism and Rhetoric in Marlowe's Edward II."

English Literary Renaissance 21 (1991): 134-60.

Notes Bevington, David and James Shapiro. "'What are kings, when regiment is

gone?': The Decay of Ceremony in Edward II." In A Poet and a

1 Steane remarks, "The verse is indeed normally thin and drab.

Filthy Play-maker: New Essays on Christopher Marlowe. Ed.

Gaveston's first speech is fine, but generally it is a matter of only lines and Friedenreich, Roma Gill, and Constance B. Kuriyama. New

Kenneth

York:

phrases here and there having any considerable poetic merit" (206). HeAMS, 1988. 263-78.

allows that the verse he finds disappointing as verse is true to the Bowers, Fredson, ed. The Complete Works of Christopher Marlowe.

real speech

of men: "It is thin, unsustained and virtually unpoetical. But it is often Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1973.

remarkably natural" (212). Lamenting the decay of rhetoric,Brooke, Steane C.

ob F. Tucker. The Life of Marlowe and The Tragedy of Dido

serves perceptively that Edward's "subsequent miseries are terrible enough Queen of Carthage. 1930. New York: Gordian, 1966.

to ensure the response which the verse of itself is incapable ofCharlton, arousing"H. B. and R. D. Waller, ed. Edward II. 1930. New York:

(222). Gordian, 1966.

2 All quotations from Edward II are from Fredson Bowers' edition. Cutts, John P. The Left Hand of God: A Critical Interpretation of the

3 As Ronald Hayman observes of Brecht's 1924 adaptation, undertak Plays of Christopher Marlowe. Haddonfield: Haddonfield House,

en in collaboration with Lion Feuchtwanger, "Socially and sexually Brecht 1973.

specifies more than Marlowe" (99), making Mortimer into "a scholarly Deats, Sara Munson. "Marlowe's Fearful Symmetry in Edward II." In A

nihilist who is reluctant at first to enter the political arena" (99). Poet and a Filthy Play-maker: New Essays on Christopher

' Deats says, "In both instances, a dignitary is first denuded of his head Marlowe. 241-62.

gear and robes, emblems of his regimen, later dispossessed of his actual Hayman, Ronald. Brecht: A Biography. New York: Oxford UP, 1983.

property, and finally humiliated by an inverted ritual" (248). The corre Masington, Charles G. Christopher Marlowe's Tragic Vision: A Study

spondences are too close to be fortuitous. in Damnation. Athens: Ohio UP, 1972.

5 Most recent writers on Edward II agree that the execution was McElroy, John F. "Repetition, Contrareity, and Individualization in Ed

staged, but in 1930 H. B. Charlton and R. D. Waller assumed otherwise in ward II." Studies in English Literature 24 (1984): 205-24.

a note to 5.5.30: "Lightborn appears to be preparing for murder by the Sales, Roger. Christopher Marlowe. New York: St. Martin's, 1993.

gruesome means Holinshed names. ... Naturally Marlowe proceeds no Sanders, Wilbur. The Dramatist and the Received Idea: Studies in the

farther with it" (200). Commenting on this note, Wilbur Sanders comes to Plays of Marlowe and Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge UP,

an opposite conclusion: "This is strong meat, so strong that the play's most 1980.

recent editors question whether Marlowe dared to stage it. Yet it is afact that Steane, J. B. Marlowe: A Critical Study. Cambridge: Cambridge UP,

he specifies feather-bed, table and spit... and it seems gratuitous to assume 1964.

that the spit was requisitioned yet not used. Clearly the whole gruesome Summers, Claude J. "Sex, Politics, and Self-Realization in Edward II." In

scene is enacted unexpurgated in full view of the audience" (124). For A Poet and a Filthy Play-maker: New Essays on Christopher

Emily Bartels, the question is not whether the execution is staged but how Marlowe. 221-40.

to avoid making Lightborn appear a caricature : "Commissioned by Mortimer, Voss, James. "Edward II: Marlowe's Historical Tragedy." English Stud

he is brought in from the outside as a sort of deus (demon?) ex machina ies 63 (1982): 517-30.

so outside that productions like Jarman's and the recent enactment at the Pit Zucker, David Hard. Stage and Image in the Plays of Christopher

have eroticized the role to bring him in" (158). After alluding to Brecht's Marlowe. Salzburg: Institut für Englische Sprache, 1972.

Contributors

Alan Armstrong, Southern Oregon State College, Ashland, ORHarry Keyishian, Fairleigh Dickinson University, Madison, NJ

Bradley S. Berens, University of California, Berkeley, CA William T. Liston, Ball State University, Muncie, IN

Paul Bertram, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ Mel Meeks, Austin, TX

David G. Brailow, McKendree College, Lebanon, IL Paul Nelsen, Marlboro College, Marlboro, VT

Maurice Charney, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ Frank Occhiogrosso, Drew University, Madison, NJ

Dorothy and Wayne Cook, Central Connecticut State Universi Louis Phillips, School of Visual Arts, New York, NY

ty, New Britain, CT Justin Shaltz, Tinley Park, IL

Betty L. Corwin, New York Public Library for the Performing Michael Shapiro, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign,

Arts Urbana, IL

H. R. Coursen, Shakespeare Globe Centre, Brunswick, ME Michael W. Shurgot, South Puget Sound Community College,

Samuel Crowl, Ohio University, Athens, OH Olympia, WA

Helen Deese, University of California, Riverside, Riverside, CA M. L. Stapleton, Stephen F. Austin State University,

Rodney Stenning Edgecombe, Cape Town, South Africa Nacogdoches, TX

George L. Geckle, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC Doug Stenberg, Sinking Spring, PA

William M. Hamlin, Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID C. P. Seabrook Wilkinson, The College of Charleston, Charles

Miranda Johnson-Haddad, Howard University, Washington, ton, SC

DC William Proctor Williams, Northern Illinois University,

DeKalb, IL

This content downloaded from

185.102.149.86 on Wed, 01 Dec 2021 08:50:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- ADocument16 pagesAjoonlunsNo ratings yet

- N Otes: I NtroductionDocument16 pagesN Otes: I NtroductionuopNo ratings yet

- Malvolio's FallDocument7 pagesMalvolio's Fallcecilia-mcdNo ratings yet

- The Lawless Language of Macpherson's "Ossian"Document28 pagesThe Lawless Language of Macpherson's "Ossian"V PNo ratings yet

- Nonsense LiteratureDocument32 pagesNonsense LiteratureArshdeep KaurNo ratings yet

- The Blessed DamozelDocument31 pagesThe Blessed Damozelamarkolaghat60No ratings yet

- Hamlet 44656876Document5 pagesHamlet 44656876Anindita MitraNo ratings yet

- The Influence of The Popular Ballad On Wordsworth and ColeridgDocument29 pagesThe Influence of The Popular Ballad On Wordsworth and ColeridgRaajdwip VardhanNo ratings yet

- English FlascardsDocument14 pagesEnglish Flascardsjanetolojede662No ratings yet

- Dramatic Poetry in Doctor FaustusDocument9 pagesDramatic Poetry in Doctor FaustustigerpiecesNo ratings yet

- Dread of Vagina in King LearDocument22 pagesDread of Vagina in King LearVid BegićNo ratings yet

- 1948 What War of The TheatresDocument4 pages1948 What War of The TheatresRichard BaldwinNo ratings yet

- 2868849Document13 pages2868849God is dead We killed himNo ratings yet

- TamingDocument5 pagesTamingpoetNo ratings yet

- Literatures in English-From Chaucer To The PresentDocument13 pagesLiteratures in English-From Chaucer To The PresentsuryasprasanthNo ratings yet

- Sheldon W. Liebman - Robert Frost, RomanticDocument22 pagesSheldon W. Liebman - Robert Frost, RomanticPratyusha BhaskarNo ratings yet

- Modernist Reading and The Death of Mrs. RamsayDocument15 pagesModernist Reading and The Death of Mrs. RamsayrameenNo ratings yet

- Why Is Shakespeare Relevant Today?Document7 pagesWhy Is Shakespeare Relevant Today?Mamoona ShahzadNo ratings yet

- Camus DostoevskyDocument15 pagesCamus DostoevskyHarris Lazaris100% (2)

- Folger Shakespeare Library George Washington UniversityDocument4 pagesFolger Shakespeare Library George Washington UniversityAdy RakaNo ratings yet

- Idle Thought in Wordsworth's Lucy Cycle: Article (Unspecified)Document13 pagesIdle Thought in Wordsworth's Lucy Cycle: Article (Unspecified)Anwar UllahNo ratings yet

- E. M. W. Tillyard - Shakespeares Problem PlaysDocument177 pagesE. M. W. Tillyard - Shakespeares Problem PlaysMaria HibovskiNo ratings yet

- TWL Anti NarrativeDocument14 pagesTWL Anti Narrativenicomaga2000486No ratings yet

- Schiller & TBKDocument37 pagesSchiller & TBKkatieNo ratings yet

- Duchess of Malfi Physical SymbolsDocument34 pagesDuchess of Malfi Physical SymbolsShanta PalNo ratings yet

- Desire and Responsibility in Robert Frost's Stopping by Woods On A Snowy Evening by April Rose FaleDocument4 pagesDesire and Responsibility in Robert Frost's Stopping by Woods On A Snowy Evening by April Rose FaleApril RoseNo ratings yet

- The Dramatization of Double Meaning in Shakespeare - S As You Like ItDocument27 pagesThe Dramatization of Double Meaning in Shakespeare - S As You Like ItMatheus MullerNo ratings yet

- Whittier 1989Document34 pagesWhittier 1989KNo ratings yet

- Kang Paper #1Document8 pagesKang Paper #1Peter KangNo ratings yet

- Ap Literature Essays That Scored A 9Document6 pagesAp Literature Essays That Scored A 9api-258322426No ratings yet

- Poetry Term 7Document21 pagesPoetry Term 7UmarNo ratings yet

- Yeats Creative ProcesDocument23 pagesYeats Creative ProcesisaotalvaroNo ratings yet

- 7 Language Strange - La Belle Dame Sans Merci and The Language oDocument16 pages7 Language Strange - La Belle Dame Sans Merci and The Language oGuillermoNo ratings yet

- Class and Comedy EssayDocument6 pagesClass and Comedy EssayEmma ShardlowNo ratings yet

- The Duchess of MalfiDocument187 pagesThe Duchess of MalfiSukanta MandalNo ratings yet

- Reading A Midsummer...Document34 pagesReading A Midsummer...ssuprodNo ratings yet

- Mac FlecknoeDocument5 pagesMac FlecknoeAmy AhmedNo ratings yet

- Letteratura IngleseDocument31 pagesLetteratura IngleseLoris AmorosoNo ratings yet

- Source and Motive in Macbeth and OthelloDocument9 pagesSource and Motive in Macbeth and OthelloSaeed jafariNo ratings yet

- Musical Forms and Textures: A Reference Guide by Norman Demuth Review By: Donald Mitchell Tempo, New Series, No. 32 (Summer, 1954), P. 37 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 10/06/2014 20:39Document2 pagesMusical Forms and Textures: A Reference Guide by Norman Demuth Review By: Donald Mitchell Tempo, New Series, No. 32 (Summer, 1954), P. 37 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 10/06/2014 20:39Rodrigo CardosoNo ratings yet

- A Reading of Adonais - Peter SackDocument23 pagesA Reading of Adonais - Peter SackExoplasmic ReticulumNo ratings yet

- 12 LoudenDocument17 pages12 LoudenIan.reardonNo ratings yet

- The Fortuneteller in Eliot's Waste LandDocument4 pagesThe Fortuneteller in Eliot's Waste Landchrisd10No ratings yet

- Hamner - The Odyssey. Dereck Walcott - S Dramatization of Homer - S OdysseyDocument8 pagesHamner - The Odyssey. Dereck Walcott - S Dramatization of Homer - S OdysseyJoseTomasFuenzalidaNo ratings yet

- Literary Terms PoetryDocument21 pagesLiterary Terms PoetryNIVEDITA GHOSHNo ratings yet

- Forker - Sexuality and Eroticism On The Renaissance StageDocument23 pagesForker - Sexuality and Eroticism On The Renaissance Stagenikole_than2No ratings yet

- كتاب شعر أولى أداب أنجليزى تقليدىDocument136 pagesكتاب شعر أولى أداب أنجليزى تقليدىIsra SayedNo ratings yet

- William Shakespeare Research PaperDocument4 pagesWilliam Shakespeare Research Papergw1w9reg100% (1)

- 2 Lecture 2 Christopher MarloweDocument5 pages2 Lecture 2 Christopher MarloweTatjana PetrovicNo ratings yet

- 10.0 PP 115 129 Romantic SonnetsDocument15 pages10.0 PP 115 129 Romantic SonnetsCatherine Kuang 匡孙咏雪No ratings yet

- Wilfred Owen and MacbethDocument4 pagesWilfred Owen and MacbethMarcusFelsmanNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare and The Theory of ComedyDocument5 pagesShakespeare and The Theory of ComedyAVRIL SOFIA GARCIA BERROCALNo ratings yet

- Edmund in King LearDocument31 pagesEdmund in King LearRitika Singh100% (2)

- The Absurd in Endgame and The MetamorphosisDocument7 pagesThe Absurd in Endgame and The MetamorphosisMubashra RehmaniNo ratings yet

- American Association of Teachers of French The French ReviewDocument9 pagesAmerican Association of Teachers of French The French ReviewahorrorizadaNo ratings yet

- Franz Kafka's Conception of HumorDocument10 pagesFranz Kafka's Conception of Humorraccoonie81No ratings yet

- La Belle DameDocument16 pagesLa Belle DameElenaMonicaNo ratings yet

- Mam SalmaDocument14 pagesMam Salmaunique technology100% (2)

- Reflections On ExileDocument2 pagesReflections On ExileJl WinterNo ratings yet

- PERLOFF ReadingFrankOHaras 2015Document10 pagesPERLOFF ReadingFrankOHaras 2015Jl WinterNo ratings yet

- Tarski S Hidden Theory of Meaning SentenDocument26 pagesTarski S Hidden Theory of Meaning SentenJl WinterNo ratings yet

- Pre-Reading: 1. Storm Soundscape: Teaching NotesDocument5 pagesPre-Reading: 1. Storm Soundscape: Teaching NotesJl WinterNo ratings yet

- Introduction The Analytic Philosophy of PoliticsDocument3 pagesIntroduction The Analytic Philosophy of PoliticsJl WinterNo ratings yet

- A Game of ChessDocument19 pagesA Game of ChessJl WinterNo ratings yet

- The Paradox of Mimesis in SidneyDocument14 pagesThe Paradox of Mimesis in SidneyJl WinterNo ratings yet

- Narcissus and Echo, The House of CadmusDocument3 pagesNarcissus and Echo, The House of CadmusJl WinterNo ratings yet

- Milton and TransumptionDocument17 pagesMilton and TransumptionJl WinterNo ratings yet

- Books We Have EnjoyedDocument1 pageBooks We Have EnjoyedJl WinterNo ratings yet

- Grade 3 Revision TestDocument5 pagesGrade 3 Revision TestNokutenda KachereNo ratings yet

- Sailing Wika TulaDocument2 pagesSailing Wika TulaAndrea WaganNo ratings yet

- Question PaperDocument2 pagesQuestion Paperskyt66No ratings yet

- Novelty LeadDocument3 pagesNovelty LeadVirgitth QuevedoNo ratings yet

- Directions: Your Essay Will Be Graded Based On This Rubric. Consequently, Use This Rubric As A Guide WhenDocument1 pageDirections: Your Essay Will Be Graded Based On This Rubric. Consequently, Use This Rubric As A Guide WhenMay Claire M. GalangcoNo ratings yet

- Gradable and Strong AdjectivesDocument7 pagesGradable and Strong Adjectivesfreddygenshin01No ratings yet

- GJ - Angleze Luisa ResidiDocument10 pagesGJ - Angleze Luisa Residilr30861No ratings yet

- Half GirlfriendDocument40 pagesHalf GirlfriendGaming Hunter NihalNo ratings yet

- Kumpulan Soal Soal Olimpiade Bahasa InggrisDocument6 pagesKumpulan Soal Soal Olimpiade Bahasa InggrisMaria Chataroos L Bancin100% (1)

- CONSONANTAL SOUNDS Lez 7Document7 pagesCONSONANTAL SOUNDS Lez 7silviasNo ratings yet

- Definition Linguistic and English Language TeachingDocument59 pagesDefinition Linguistic and English Language TeachingCres Jules ArdoNo ratings yet

- DLL - English 4 - Q1 - W5Document4 pagesDLL - English 4 - Q1 - W5Janette Tibayan CruzeiroNo ratings yet

- English Translation Thesis PDFDocument8 pagesEnglish Translation Thesis PDFcarolynostwaltbillings100% (2)

- Workbook AnswerkeyDocument16 pagesWorkbook AnswerkeyAcadèmia Siblings Acadèmia Siblings100% (1)

- Mother Tongue AssessmentDocument58 pagesMother Tongue AssessmentMar SebastianNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2.2 Communicative CompetenceDocument38 pagesChapter 2.2 Communicative CompetenceAlma Yumul BaltazarNo ratings yet

- Interchange of DegreeDocument8 pagesInterchange of DegreeShubhamNo ratings yet

- بِسَاطُ الرِّيحِDocument92 pagesبِسَاطُ الرِّيحِZxc ShNo ratings yet

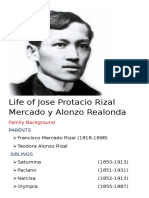

- Life of Jose Protacio Rizal Mercado y Alonzo RealondaDocument6 pagesLife of Jose Protacio Rizal Mercado y Alonzo RealondaA Khim JhoyNo ratings yet

- Techniques For Textual Analysis and Close ReadingDocument33 pagesTechniques For Textual Analysis and Close ReadingJen75% (4)

- DepEd Order No. 16 S 2012-1Document3 pagesDepEd Order No. 16 S 2012-1Xia FordsNo ratings yet

- Linguistic ApproachDocument12 pagesLinguistic ApproachMariaJesusLaraNo ratings yet

- CSI3104 S2011 Midterm1 SolnDocument7 pagesCSI3104 S2011 Midterm1 SolnQuinn JacksonNo ratings yet

- Quiz 2 Application/AssessmentDocument3 pagesQuiz 2 Application/AssessmentJenny Babe LingutanNo ratings yet

- Comparison of AdjectivesDocument15 pagesComparison of AdjectivesAizel Nova Fermilan ArañezNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary QuestionsDocument13 pagesVocabulary QuestionsNguyễnThị ViệtAnhNo ratings yet

- Template PSKC CW2 2Document14 pagesTemplate PSKC CW2 2Mohammad Sabbir ShehzadNo ratings yet

- The Business of Words Wordsmiths, Linguists, and Other Language Workers by Crispin ThurlowDocument223 pagesThe Business of Words Wordsmiths, Linguists, and Other Language Workers by Crispin ThurlowVu DangxuanNo ratings yet

- SeliwusuDocument4 pagesSeliwusuAYOUNG KimNo ratings yet

- 119th KSW Transcript EN Draft v1Document53 pages119th KSW Transcript EN Draft v1Miguel VegaNo ratings yet