Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Process-Oriented Pedagogy: Facilitation, Empowerment, or Control?

Process-Oriented Pedagogy: Facilitation, Empowerment, or Control?

Uploaded by

islembenjemaa12Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Process-Oriented Pedagogy: Facilitation, Empowerment, or Control?

Process-Oriented Pedagogy: Facilitation, Empowerment, or Control?

Uploaded by

islembenjemaa12Copyright:

Available Formats

point and counterpoint

Process-oriented pedagogy:

facilitation, empowerment,

or control?

William Littlewood

Downloaded from http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org/ at Ryerson University on December 3, 2014

A feature of language teaching in recent decades has been the development of

process-oriented approaches. This orientation towards processes encourages us to

facilitate learner choice and individual development. However, it is challenged by

the current educational climate, which prioritizes accountability and assessment.

In this situation, a new perspective on process orientation has emerged. This

perspective focuses not on the processes which occur as part of learning but on the

processes which are the intended outcomes of this learning. Discrete features of the

communication and learning processes become pre-specified ‘learning outcomes’,

which are to be observed and assessed. Outcomes-based education is promoted as

a means of empowering learners with the knowledge and skills required for living.

However, it is also a powerful instrument for effecting compliance with centralized

conceptions of education and can minimize the voices of learners and teachers in

the process of education.

Introduction An important feature of foreign language teaching over recent decades has

been increasing attention not only to the products that we expect learning to

achieve (for example control of selected grammatical structures or

communicative functions) and the pedagogy that might lead to these

products but also to the processes through which learning takes place. As

Hedge (2000: 359) expresses it, ‘the question has become not so much on

what basis to create a list of items to be taught as how to create an optimal

environment to facilitate the processes through which language is learned’.

This has led to increased interest in how learning is influenced by, for

example, affective factors, cognitive styles, and group dynamics. It has also

led to increased attention to students’ natural learning capacities and how to

stimulate these through strategies such as personalization and awareness

raising. At the planning level, it has encouraged teachers to organize their

courses around holistic learning experiences such as projects and tasks, in

the belief that the resulting ‘negotiation of meanings’ is the most effective

facilitator of individual learning.

Processes in the The literature is less explicit than it might be on the precise distinction

classroom between terms such as ‘process’, ‘skill’, and ‘state’. It is common, for

example, to find writing or listening referred to as ‘processes’ in one context

246 E LT Journal Volume 63/3 July 2009; doi:10.1093/elt/ccn054

ª The Author 2008. Published by Oxford University Press; all rights reserved.

Advance Access publication August 18, 2008

and ‘skills’ in another. Similarly, we find that motivation is discussed both as

an affective ‘process’ and as an affective ‘state’. The position taken in this

paper is that processes may be mobilized as part of a skill (for example as in

‘controlled and automatic processing’) or may cluster together to form

a ‘state’ (for example as in a connectionist account, where mental or affective

states are produced by processes within neural networks) but are present in

both. Thus, when mention is made of what may often be termed a skill or

state, reference is also made by implication to the processes which facilitate or

produce them.

Thanks to seminal work by investigators such as Allwright (1996), Breen

(1986), and Senior (2006), we have become strongly aware of the richness

of classroom interaction and the complexity of the processes within it. Any

analytical framework must be an oversimplification of this complexity, but

here I will distinguish four interconnected levels which figure prominently

Downloaded from http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org/ at Ryerson University on December 3, 2014

in current discussions. Within each level, there are both facilitative and

inhibitive processes.

Affective processes

For example, a student’s learning is facilitated by feelings of self-confidence

and self-esteem, but inhibited by anxiety.

Cognitive processes

For example, learning is facilitated by the capacity to make inferences, but

inhibited by premature closure (in which a student does not consider

alternative answers).

Social processes

For example, learning is facilitated by group cohesion and cooperation but

inhibited by social loafing (when individual students do not contribute to

a group task).

Communication processes

For example, learning is facilitated by comprehension but inhibited when

one person is over-dominant in turn-taking.

A special category of process consists of the pedagogic processes by which the

teacher tries to influence the processes mentioned above. Thus, for

example, she/he may try to influence the affective level positively by creating

a relaxed environment; the cognitive level by asking challenging questions;

the social level by using effective grouping techniques; and the

communication level by creating opportunities for all learners to participate.

In these various ways, the teacher aims to stimulate developmental processes

leading to development at all four levels, for example, towards more positive

attitudes, better critical thinking skills, enhanced ability to cooperate, and

higher proficiency in the ‘four skills’. However, pedagogic processes may

also create negative effects (for example excessive criticism may damage

self-esteem and motivation), so that they may be either facilitative or

inhibitive of learning.

Process-oriented pedagogy: facilitation, empowerment, or control? 247

At this point our perspective goes beyond the classroom and considers the

outcomes of this development, which the student will carry from the

classroom into the future.

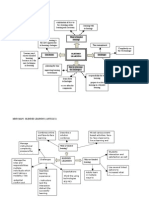

Table 1 presents a summary of the types of process mentioned above. Those

in columns 1–3 are processes which occur within the classroom and affect

learning. This is the domain addressed by process-oriented teaching as

understood in the discussion so far. Those in column 4 are the outcomes of

learning. This is the domain addressed by process-oriented teaching as seen

from the perspective of outcomes-based education, which is introduced in

the next section.

As mentioned above, the pedagogic processes (column 3) can in reality be

inhibitive as well as facilitative. Furthermore, the outcomes (column 4) can

be negative as well as positive (for example a student’s classroom

Downloaded from http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org/ at Ryerson University on December 3, 2014

experiences may engender negative attitudes to learning). However, to avoid

a confusing proliferation of columns, only the facilitative and positive

processes are included in Table 1. These are also, of course, the processes

towards which we direct our pedagogical strategies.

1 2 3 4

Facilitative Inhibitive Pedagogic Processes as

processes processes processes outcomes

Affective e.g. self- e.g. excessive

e.g. creating positive

processes confidence anxiety a relaxed attiudes, etc.

environment

Cognitive e.g. making e.g. premature e.g. challenging critical

processes inferences closure ideas thinking, etc.

Social e.g. group e.g. social e.g. effective cooperation

processes cohesion loafing grouping skills, etc.

techniques

table 1

Communication e.g. e.g. dominance e.g. creating the ‘four skills’,

Main types of process in

processes comprehension in turn-taking space to etc.

the foreign language

communicate

classroom

In the next section, I will refer to the processes in columns 1–3 as ‘processes

in progress’ and those in column 4 as ‘processes as outcomes’. The terms are

clumsy but serve to make a necessary distinction in this paper.

Two perspectives on Following from the above, when we talk about ‘process-oriented language

‘process orientation’ teaching’, this may carry two distinct meanings. On the one hand, it might

in the classroom mean that we pay special attention to the processes-in-progress that go on

inside the classroom. This is the perspective taken in the quotation from

Hedge above and by the proponents of, for example, process writing, project

work, or other forms of experiential learning. It is the classroom-

methodological perspective taken by most practising teachers. On the other

hand, it might mean that we attend to the processes that are the intended

outcomes of learning. This is the case for curriculum designers and assessors

when they express the intended outcomes of learning in terms of processes,

skills, and states.

248 William Littlewood

An example of this process-as-outcome perspective is the Singapore English

Language Syllabus 2001 (Curriculum Planning and Development Division

2001). It lists intended outcomes from all levels presented in Table 1 (but

mainly of course from the communication level). For example, by the end of

Primary 2—in the confident can-do terminology featured in many such

documents—‘pupils will’:

n enjoy the creative use of language in, for example, similes, poems, and

jokes (affective level)

n infer and draw conclusions about characters, sequence of events

(cognitive level)

n follow agreed-upon rules for group work (social level)

n speak to convey meaning using intonation (communication level).

Similarly, the English Language Curriculum Guide (Primary 1–6) for Hong

Downloaded from http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org/ at Ryerson University on December 3, 2014

Kong (Curriculum Development Council 2004) expects that by the end of

Primary 6, students should learn to ‘be confident of their own judgement,

performance, and capabilities’ (affective level), ‘question obvious bias,

propaganda, omissions, and less obvious fallacies’ (cognitive level), ‘work

and negotiate with others to develop ideas and achieve goals’ (social level),

and ‘present information, ideas and feelings clearly and coherently’

(communication level).

The two perspectives do not exclude each other but there is tension. The

process-in-progress perspective provides the underpinnings for liberal,

humanistic approaches which emphasize learner choice, individual

development, and autonomy. Its intention is to facilitate growth in

personally meaningful directions. The process-as-outcome perspective

provides the underpinnings for approaches which work with detailed prior

specifications of the directions that learners should follow. This second

perspective is an important move to empower learners by giving them the

skills they need in order to participate fully in future life. However, as we will

see later, it can also form a basis for totalitarian control over how students are

taught to act and think as a result of their education.

Three approaches to Having distinguished these two orientations towards process-oriented

integrating process language teaching, I will make a brief historical excursion into changing

and product in the approaches to integrating process and product over the past three or four

language classroom decades. These approaches overlap, of course, and an individual teacher

may integrate more than one into his or her own pedagogy.

Product-as-outcome The first approach, which is associated with the so-called ‘product-based’

oriented language syllabus underlying the audio-lingual, audio-visual, and early functional

teaching approaches, may be characterized as follows:

n The initial focus is not so much on processes as on the intended products

of learning, conceptualized, for example, as grammatical structures,

vocabulary items, or communicative functions.

n The products which are most appropriate for particular learners may be

determined through needs analysis.

n Classroom learning processes are designed to help learners acquire these

items, for example, through intensive practice, communication activities,

exercises, or writing tasks.

Process-oriented pedagogy: facilitation, empowerment, or control? 249

n In general, there is separation of syllabus (what is to be learnt) and

methodology (how it should be learnt).

The main impetus to revise this approach has been the argument that it

neglects both the complexity of the processes involved in using language

and the range of processes that can contribute to language learning (see for

example Nunan 1988).

Process-in-progress The second approach attempts to compensate for this perceived neglect and

oriented language is what most people probably think of when they talk of a ‘process-oriented

teaching approach’. It is the approach summarized in the quotation from Hedge (op.

cit.: 359) above and is associated with humanistic language teaching,

experiential learning, task-based language teaching, and other

communicative approaches. It may be characterized as follows:

Downloaded from http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org/ at Ryerson University on December 3, 2014

n There is a shift from emphasizing what we want students to learn to the

processes by which they learn, leading to a focus on processes such as

creative construction, personal learning strategies, and developmental

processes leading to autonomous performance.

n There is a shift from teaching discrete language items towards focusing

on the processes that are involved in using language for communication

and the need to develop active skills for negotiating meanings in real

contexts.

n There is a move from a ‘transmission’ approach in which the teacher

passes on predetermined knowledge and skills to an ‘interpretative’

approach which facilitates learners’ individualized development.

n This development is recognized as involving not only cognitive aspects

but the ‘whole person’ of the learner in whom cognitive, social, and

affective aspects are inseparable.

n The need to facilitate the learners’ processes of development leads to an

emphasis on creating learning contexts which stimulate motivation and

provide opportunities for personal growth.

For many, this learner- and learning-centred approach represents an

educational ideal. It goes back to the seminal educational ideas of Dewey and

Bruner, and underpins the constructivist approach to education in which,

as Williams and Burden (1997: 51) put it, ‘education becomes concerned

with helping people to make their own meanings’ (emphasis added).

The first approach (product-as-outcome) was challenged predominantly on

the grounds of its conceptions of learning and communication. The second

is challenged mainly from outside the learning context itself. The current

educational climate puts high priority on assessment, control, and

accountability. But if the focus is on the process of learning and each

individual can work towards his or her unique personal outcomes and

meanings, how can the effectiveness of learning be assessed in terms

recognized by the various stakeholders? Or looking at it another way, how

can the stakeholders exert their control over the educational process and

make clear not just what students will study but ‘how they will be able to act

and think as a result of their education’ (Riordan 2005: 56)? This is where

the third approach, oriented towards process-as-outcome, enters the scene.

250 William Littlewood

Process-as-outcome Outcomes-based education has been an educational ‘buzz-word’ in many

oriented teaching places for well over a decade and is now promoted by educational planners

in several countries, including the USA, Australia, UK, Hong Kong, and

Singapore (see for example Stone 2005, on the policy of funding its

introduction into all tertiary institutions in Hong Kong). In the field of

language teaching, we saw above how it has influenced the English

language curricula of Singapore and Hong Kong. It is a fusion of the two

approaches already discussed:

n Like the ‘process-in-progress’ approach, it starts from an initial focus on

processes. But processes are seen now from the second perspective

discussed earlier: processes as the outcomes of learning.

n Like the ‘product-as-outcome’ approach, it is outcome oriented. But these

outcomes are now process outcomes rather than content outcomes.

n Also like the ‘product-as-outcome’ approach, there is an emphasis on the

Downloaded from http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org/ at Ryerson University on December 3, 2014

observable and measurable. Intended learning outcomes are usually

stated with ‘a verb to describe the behaviour which demonstrates the

student’s learning’ (Carroll 2001: 3).

n On the basis of these predetermined learning outcomes, we design the

curriculum backwards, ‘using the major outcomes as the focus and

linking all planning, teaching and assessment decisions directly to these

outcomes’ (Acharya 2003: 8–9).

We saw that the process-in-progress approach has a strong interest in

classroom methodology and the conditions that stimulate learning. This is

not the case with the process-as-outcome approach, many of whose

proponents have a lot to say about the outcomes of learning but little about

the learning and teaching that lead to these outcomes. For example, the

guide to curriculum development by Posner and Rudnitsky (1997) contains

seven chapters on outside-classroom procedures involving learning

outcomes (for example how to write them and design units around them)

but only one on classroom teaching strategies, in spite of recognizing that

‘even the most elegantly organized course, designed for the most

worthwhile learning, can fail if the teaching strategies are inappropriate or

insufficient for the desired learning’ (p. 163). The 2001 Singapore English

syllabus contains well over 100 pages which cover the learning outcomes,

text-types, and grammar to be included in a course, but less than a page on

the six ‘principles of language learning and teaching’ which ‘form part of the

framework and spirit in which this syllabus is to be implemented’

(Curriculum Planning and Development Division 2001: 4). It contains no

equivalent to the suggestions for classroom activities included in the 1991

syllabuses which it superseded.

Where are we now? With respect to process-oriented teaching we stand at a crossroads.

The process-in-progress perspective, which has led teachers to explore

methodological innovations in domains such as process writing, project

work, task-based instruction, and other forms of experiential learning,

continues to attract and inspire teachers. In the minds of many planners

and curriculum designers, however, attention has shifted mainly to the

process-as-outcome perspective, which focuses on the observable results of

classroom processes. The motivation appears to be four-fold, with varying

emphases in different contexts and by different people. Here I rank the

Process-oriented pedagogy: facilitation, empowerment, or control? 251

motives according to the closeness of their relationship to actual classroom

learning:

1 The first motive is to ensure that learning has clear directions. Teachers

and course-developers decide what they would like students to learn in

terms which enable participants to clarify objectives and determine to

what extent these have been achieved.

2 Information about whether or to what extent learning has taken place can

be gathered not only at the end of a course but also during the course.

Thus, the second motive is to facilitate formative ‘assessment for

learning’.

3 As Brindley (2001) shows, the wider system can subvert the second

motive and transform information gathered to support learning into

information used for reporting and grading. This is the third motive. It

reaches outside the classroom and may involve purposes of gate keeping

Downloaded from http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org/ at Ryerson University on December 3, 2014

(for the student) and accountability (for the teacher and/or institution).

4 The fourth motive is an extension of the third. When the system itself, for

example, via government education bodies, (a) specifies expected

learning outcomes, (b) measures whether they have been achieved,

and (c) makes student progression and institutional funding contingent

upon the results, tools are in place for people at the centre to exercise top–

down control over the goals and implementation of the educational

process.

The first and second of these motivations are directly beneficial to student

learning. Indeed, they may be integrated with the process-in-progress

approach and make it more purposeful and needs-related. The third

motivation introduces the dimension of accountability and no longer

focuses on the conditions for effective learning, but rather, it focuses on how

the results of learning can be demonstrated. This is also the case with the

fourth perspective, with the added factor that the learning to be

demonstrated has been predetermined by people in authority, whose own

expertise and experience in teaching may be superficial.

With the fourth scenario, then, the wheel of curriculum planning comes full

circle. From the focus on detailed definitions of products of learning that

characterizes the product-as-outcome approach, through the focus on ways

of facilitating individual processes of learning that characterizes the process-

in-progress approach, the focus moves to detailed definitions of processes

themselves as assessable products of learning. The approach is again product

oriented but now the defined products of learning are described not in terms

of discrete language or functional items but in terms of discrete processes.

These definitions prescribe in detail, in words quoted earlier, ‘not just what

[students] will study but also how they will be able to act and think as a result of

their education’ (Riordan op.cit.: 56, emphasis added).

In the context of a totalitarian system (for example as in George Orwell’s

novel 1984 or pre-1989 communist regimes in Europe), the words just

quoted would have sinister implications. Even outside a totalitarian system,

the more detailed and far-reaching these specifications for acting and

thinking become, the stronger is their potential (when underpinned by

assessment, rewards, and sanctions) to become a powerful instrument for

exerting control and imposing the policies and values of those in authority.

252 William Littlewood

The prescriptions can easily form the basis for what Alexander (2004: 29),

in his biting critique of the target-and-performance based National

Curriculum in the UK, describes as a ‘highly centralized and interventive

education system’ in which ‘those who have the greatest power to prescribe

pedagogy’ may be precisely those who have ‘the poorest understanding of it’.

Such a system encourages a ‘culture of compliance’ in which teachers are

merely ‘technicians who implement the educational ideas and procedures

of others’ (p. 11) and attention to outcomes deflects attention from the

classroom pedagogy that should produce them.

Conclusion The question contained in the title of this paper is central to how we conceive

the development of language teaching. The origin of process-oriented

language teaching lies firmly in the desire to facilitate. To the extent that the

processes which we want to facilitate are individual, we cannot—indeed

Downloaded from http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org/ at Ryerson University on December 3, 2014

would not want to—predict their direction and outcomes. There is

a significant shift in emphasis and intention when we say that some

outcomes are more desirable than others, so that we should guide learning

towards them with the desire of empowering students for their future life.

There is an equally significant shift when these desirable outcomes are

determined not by those directly involved in the pedagogical processes that

should lead to them but from outside, often by government appointees. It is

at this point that process-oriented teaching becomes an instrument of

control.

At the current stage we are at, then, a key task is to use what means we have

to ensure that the voices of teachers and learners are not drowned in the

name of accountability; that control stays in the hands of those who also

have expertise; and that we draw benefits from process-oriented teaching

while avoiding its dangers.

Final version received June 2008

Note Breen, M. P. 1986. ‘The social context for language

This paper is a revised and reworked version of a learning—a neglected situation?’ Studies in Second

plenary paper presented at the CLaSIC 2006 Language Acquisition 7/2: 135–58.

Conference held in Singapore in December, Brindley, G. 2001. ‘Outcome-based assessment in

2006. practice: some examples and emerging insights’.

Language Testing 18/4: 393–407.

Carroll, J. 2001. ‘Writing learning outcomes: some

References suggestions’. Learning and Teaching. Oxford Centre

Acharya, C. 2003. ‘Outcome-based education (OBE): for Staff and Learning Development, Oxford

a new paradigm for learning’. C DT Link (National Brookes University. Available at: http://

University of Singapore), 7–9 July. Available at: www.brookes.ac.uk/services/ocsd/2_learntch/

http://www.cdtl.nus.edu.sg/link/nov2003/obe.htm writing_learning_outcomes.html (last accessed

(last accessed 7 June 2008). 7 June 2008).

Alexander, R. 2004. ‘Still no pedagogy? Principle, Curriculum Development Council. 2004. English

pragmatism and compliance in primary education’. Language Curriculum Guide (Primary 1–6). Hong

Cambridge Journal of Education 34/1: 7–33. Kong: Education Bureau. Available at: http://

Allwright, D. 1996. ‘Social and pedagogic pressures www.edb.gov.hk/index.aspx?langno¼1&;nodeID¼

in the language classroom: the role of socialization’ 2770 (last accessed 7 June 2008).

in H. Coleman (ed.). Society and the Language Curriculum Planning and Development Division.

Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge 2001. English Language Syllabus 2001 for Primary and

University Press.

Process-oriented pedagogy: facilitation, empowerment, or control? 253

Secondary Schools. Singapore: Ministry of Education. Polytechnic University, December, 2005. Available

Available at: http://www.moe.gov.sg/cpdd/ at: http://www.ugc.edu.hk/eng/ugc/publication/

syllabuses.htm (last accessed 7 June 2008). speech/2005/sp171205.htm (last accessed

Hedge, T. 2000. Teaching and Learning in the 7 June 2008).

Language Classroom. Oxford: Oxford University Williams, M. and R. L. Burden. 1997. Psychology for

Press. Language Teachers: A Social Constructivist Approach.

Nunan, D. 1988. Syllabus Design. Oxford: Oxford Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

University Press.

Posner, G. J. and A. N. Rudnitsky. 1997. Course Design: The author

A Guide to Curriculum Development for Teachers (Fifth William Littlewood was involved in language

edition). New York: Longman. teaching and teacher education in the UK for many

Riordan, T. 2005. ‘Education for the 21st century: years before moving to Hong Kong in 1991 to join

teaching, learning and assessment’. Change a project in E LT curriculum development. He is

37/1: 52–6. currently a Professor in the Department of English,

Senior, R. 2006. The Experience of Language Teaching. Hong Kong Institute of Education, Tai Po, Hong

Downloaded from http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org/ at Ryerson University on December 3, 2014

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kong. He has published widely in the areas of

Stone, M. V. 2005. Opening remarks at the language teaching methodology and language

‘Symposium on Outcome-based Approach to learning.

Teaching, Learning and Assessment in Higher Email: blittle@ied.edu.hk

Education: International Perspectives’. Hong Kong

254 William Littlewood

You might also like

- The Star Maiden CircleDocument3 pagesThe Star Maiden CircleLeo Rutherford100% (6)

- 1995 Prodromou BackwashDocument13 pages1995 Prodromou Backwashapi-286919746No ratings yet

- Pedagogies for Student-Centered Learning: Online and On-GoundFrom EverandPedagogies for Student-Centered Learning: Online and On-GoundRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Backwash EffectDocument13 pagesBackwash EffectSujatha Menon83% (12)

- Student Representative Roles and ResponsibilitiesDocument2 pagesStudent Representative Roles and ResponsibilitiesCristina Gabriela DumitruNo ratings yet

- ELT Journal Volume 41 Issue 3 1987 (Doi 10.1093 - Elt - 41.3.193) Maclennan, S. - Integrating Lesson Planning and Class ManagementDocument5 pagesELT Journal Volume 41 Issue 3 1987 (Doi 10.1093 - Elt - 41.3.193) Maclennan, S. - Integrating Lesson Planning and Class ManagementenglishvideoNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Theories of Learning: Ro RoachesDocument35 pagesUnit 1 Theories of Learning: Ro RoachesSaurabh SatsangiNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Framework Peer ObservationDocument13 pagesTheoretical Framework Peer ObservationAntonieta HernandezNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning ProcessDocument5 pagesTeaching and Learning ProcessQurban NazariNo ratings yet

- Tarea 5 Didáctica Del InglésDocument6 pagesTarea 5 Didáctica Del Inglésjos oviedoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5Document5 pagesChapter 5Ayse Kaman ErtürkNo ratings yet

- Assignment No.1 Course: Curriculum Development and Instruction (838) Semester: Spring, 2021Document10 pagesAssignment No.1 Course: Curriculum Development and Instruction (838) Semester: Spring, 2021Adnan NazeerNo ratings yet

- Natureofteaching 201010083816Document28 pagesNatureofteaching 201010083816Guenevere EsguerraNo ratings yet

- Nunan (1994) Enhancing The Role of The Learner Within The Learning ProcessDocument8 pagesNunan (1994) Enhancing The Role of The Learner Within The Learning ProcessChompNo ratings yet

- psychologyoflearningandteachingSSRN Id1429346Document22 pagespsychologyoflearningandteachingSSRN Id1429346DulakshiNo ratings yet

- Constructivism: Instructional Principles (Problem-Based Learning)Document10 pagesConstructivism: Instructional Principles (Problem-Based Learning)MinaTorloNo ratings yet

- Motivational ProcessesDocument9 pagesMotivational ProcessesvalemaciasNo ratings yet

- The Teacher and The School Curriculum Module 3Document7 pagesThe Teacher and The School Curriculum Module 3deveravanessa01No ratings yet

- Considerations in Designing A Curriculum Part 2Document3 pagesConsiderations in Designing A Curriculum Part 2liliyayanonoNo ratings yet

- Statistics Final Papers (..)Document55 pagesStatistics Final Papers (..)pitogoangel4443No ratings yet

- Meta CognitionDocument8 pagesMeta CognitionabidkhusnaNo ratings yet

- Narrative Report 3rd YearDocument27 pagesNarrative Report 3rd YearKissMarje EsnobeRaNo ratings yet

- Knowlede and CurriculumDocument19 pagesKnowlede and CurriculumRitik KumarNo ratings yet

- BC Elt 2010 179Document40 pagesBC Elt 2010 179Cecilia Toledo VallejosNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Concepts of Teaching and Learning: September 2012Document8 pagesIntroduction To Concepts of Teaching and Learning: September 2012Bryan NozaledaNo ratings yet

- Crabbe 1993Document10 pagesCrabbe 1993Anh ThyNo ratings yet

- Barboza Bryan m5 Activity 1 2ced 3Document20 pagesBarboza Bryan m5 Activity 1 2ced 3Trisha Anne BataraNo ratings yet

- Modern Trends in The Psychology of Learning and TeachingDocument21 pagesModern Trends in The Psychology of Learning and TeachingCarlo Magno94% (18)

- Influencing Learning Environments Through Critical Classroom Discourse AnalysisDocument5 pagesInfluencing Learning Environments Through Critical Classroom Discourse AnalysisDilla DillaNo ratings yet

- Nonformal Learning and Tacit Knowledge in Professional Work - AfraDocument24 pagesNonformal Learning and Tacit Knowledge in Professional Work - Afrairfan ardiNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Apprenticeship: Making Thinking VisibleDocument18 pagesCognitive Apprenticeship: Making Thinking VisibleAna Maria MarhanNo ratings yet

- Proof PedagoDocument5 pagesProof Pedagoapi-727798340No ratings yet

- Innovative and Improved Instructional Practices-EditedDocument12 pagesInnovative and Improved Instructional Practices-EditedMariaNo ratings yet

- Goh Lay Huah ThesisDocument29 pagesGoh Lay Huah ThesisMuhammad IzWan AfiqNo ratings yet

- The Conceptual Basis of Second Language Teaching and LearningDocument3 pagesThe Conceptual Basis of Second Language Teaching and LearningLiezel Evangelista Baquiran100% (1)

- Carless (2006) Differing Perceptions in The Feedback ProcessDocument16 pagesCarless (2006) Differing Perceptions in The Feedback ProcessEdward FungNo ratings yet

- Quality in Classroom TransactionDocument3 pagesQuality in Classroom TransactionrajmohapatraNo ratings yet

- Edu633 Eschlegel Unit 8 May 1 30Document5 pagesEdu633 Eschlegel Unit 8 May 1 30api-317109664No ratings yet

- hd341 Syllabus sp1 2015Document13 pageshd341 Syllabus sp1 2015api-282907054No ratings yet

- Learning Through Reflection - A Guide For The Reflective PractitionerDocument9 pagesLearning Through Reflection - A Guide For The Reflective PractitionergopiforchatNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3Document5 pagesLesson 3Rhea Mae GastadorNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Teaching-L E A Process: A Revisit: StructureDocument21 pagesUnit 1 Teaching-L E A Process: A Revisit: StructureZainuddin RCNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1.1 - Basic Concepts of The CurriculumDocument8 pagesLesson 1.1 - Basic Concepts of The CurriculumEdsel Buletin100% (1)

- What Is Role of The Learner?Document6 pagesWhat Is Role of The Learner?Dušica Kandić NajićNo ratings yet

- Applying Behavior Analytic Procedures To Effectively Teach Literacy Skills in The ClassroomDocument17 pagesApplying Behavior Analytic Procedures To Effectively Teach Literacy Skills in The ClassroomCaptaciones CDU CanteraNo ratings yet

- Yeld NDocument14 pagesYeld NArt CalusinNo ratings yet

- Group Project Work and Student-Centred Active Learning: Two Different ExperiencesDocument21 pagesGroup Project Work and Student-Centred Active Learning: Two Different ExperiencesbipinNo ratings yet

- Statement of The ProblemDocument10 pagesStatement of The ProblemJoanneNBondoc100% (1)

- Collaborative LearningDocument7 pagesCollaborative LearningZine EdebNo ratings yet

- In The Lecture RoomDocument11 pagesIn The Lecture Roomjcb1962No ratings yet

- Module Copies For Prof Ed 7Document23 pagesModule Copies For Prof Ed 7Auvepher Salvador Nicolas0% (1)

- Proposition 1: To Truly Make Research A Central Part of Teaching, We Must Redefine ResearchDocument10 pagesProposition 1: To Truly Make Research A Central Part of Teaching, We Must Redefine ResearchՉինարեն Լեզվի ԴասընթացներNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Theory and PracticeDocument4 pagesCurriculum Theory and PracticeMaria Eloisa Blanza100% (1)

- CurriculumDocument2 pagesCurriculumkhanbhaiNo ratings yet

- Critical and Reflective ThinkingDocument5 pagesCritical and Reflective ThinkingDirma Yu LitaNo ratings yet

- 2003 11 Nunan EngDocument12 pages2003 11 Nunan EngHa H. MuhammedNo ratings yet

- Instructional Supervision As Dialogue: Utilizing The Conversation of Art To Promote The Art of CommunicationDocument25 pagesInstructional Supervision As Dialogue: Utilizing The Conversation of Art To Promote The Art of Communication张丽红No ratings yet

- Collaborative Learning in English 10Document52 pagesCollaborative Learning in English 10Marc Christian CachuelaNo ratings yet

- English for Students of Educational Sciences: Educational SciencesFrom EverandEnglish for Students of Educational Sciences: Educational SciencesNo ratings yet

- Accuracy of Student Self-Assessment (With a Rubric)Document33 pagesAccuracy of Student Self-Assessment (With a Rubric)islembenjemaa12No ratings yet

- Al Hattami 2015Document12 pagesAl Hattami 2015islembenjemaa12No ratings yet

- Andrade & Du 2005Document12 pagesAndrade & Du 2005islembenjemaa12No ratings yet

- MLJ Reviews: University of IowaDocument24 pagesMLJ Reviews: University of Iowaislembenjemaa12No ratings yet

- Module 7: Republic Act 9163: Don Honorio Ventura State University National Service Training Program Iteracy Rining RogramDocument1 pageModule 7: Republic Act 9163: Don Honorio Ventura State University National Service Training Program Iteracy Rining RogramElizabeth SantosNo ratings yet

- Rui Miguel Lima Mateus: Personal ProfileDocument2 pagesRui Miguel Lima Mateus: Personal Profileapi-351400418No ratings yet

- Lorax Short Story ModuleDocument13 pagesLorax Short Story Moduleauds321No ratings yet

- Foreign Degrees in Malaysia - 28 November 2017Document4 pagesForeign Degrees in Malaysia - 28 November 2017Times MediaNo ratings yet

- Achievement TestDocument17 pagesAchievement TestNeamtiu Roxana100% (1)

- Ab ResumeDocument2 pagesAb Resumeapi-212344072No ratings yet

- MattersDocument443 pagesMattersurfinas100% (2)

- 1-Intro To Course of I.RDocument15 pages1-Intro To Course of I.Rsyed HassanNo ratings yet

- My First Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesMy First Lesson Planapi-283570836100% (5)

- Arellano University: Mas 106: Building and Enhancing New Literacies Across The CurriculumDocument2 pagesArellano University: Mas 106: Building and Enhancing New Literacies Across The CurriculumCarl LewisNo ratings yet

- Gifted and Learning Exceptionalities - HandoutDocument2 pagesGifted and Learning Exceptionalities - Handoutapi-265656322No ratings yet

- Letter D Lesson Plan3Document6 pagesLetter D Lesson Plan3Anonymous ZAqf8ONo ratings yet

- Community HelpersDocument5 pagesCommunity Helpersapi-270878578No ratings yet

- Education g5Document41 pagesEducation g5Anonymous fjkL8HNo ratings yet

- Interview With Steven McDonoughDocument8 pagesInterview With Steven McDonoughJames FarnhamNo ratings yet

- Ketchup & Pickle FoldersDocument1 pageKetchup & Pickle FoldersDallas Anne ThompsonNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan DLP F1 3 - 2 Writing - 2Document1 pageDaily Lesson Plan DLP F1 3 - 2 Writing - 2chezdinNo ratings yet

- Mind Map of Blended LearningDocument2 pagesMind Map of Blended Learningrahmatina2811100% (1)

- Tins WebsheetsDocument46 pagesTins WebsheetsForest Wong33% (3)

- MHM Training GuideDocument79 pagesMHM Training GuideBismarck BravoNo ratings yet

- Louisiana Wing - Sep 2005Document9 pagesLouisiana Wing - Sep 2005CAP History LibraryNo ratings yet

- Teacher Prep Review - Strengthening Elementary Reading InstructionDocument105 pagesTeacher Prep Review - Strengthening Elementary Reading InstructionRuss LatinoNo ratings yet

- Richard Jack Auslen ResumeDocument1 pageRichard Jack Auslen Resumeapi-380164296No ratings yet

- Math 6 Q1 Week1 Day1Document3 pagesMath 6 Q1 Week1 Day1Elijah JumawanNo ratings yet

- Mambuaya National High School Enior IGH Chool Evel: DLL in Oral Communication in ContextDocument2 pagesMambuaya National High School Enior IGH Chool Evel: DLL in Oral Communication in ContextCydryl A MonsantoNo ratings yet

- Exploratory Essay Arts Funding - Dominic KociskiDocument3 pagesExploratory Essay Arts Funding - Dominic Kociskiapi-236343147No ratings yet

- Weekly Accomplishment ReportDocument21 pagesWeekly Accomplishment ReportMa Lucita Baydo100% (2)

- Purpose StatementDocument2 pagesPurpose Statementapi-355443685No ratings yet