Professional Documents

Culture Documents

PionBerlin VictimsExecutionersArgentine 1991

PionBerlin VictimsExecutionersArgentine 1991

Uploaded by

caitlinsarah12342Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Unit 7 Aspects of Tort Aim C and Learning Aim D CWDocument10 pagesUnit 7 Aspects of Tort Aim C and Learning Aim D CWsuccesshustlerclubNo ratings yet

- Richards ComplaintDocument11 pagesRichards ComplaintHelena_RS100% (1)

- Infographic Violence Against Women en 11x17 No BleedsDocument1 pageInfographic Violence Against Women en 11x17 No BleedsEdward NoriaNo ratings yet

- Good, Bad or Absent: Discourses of Parents With Disabilities in Australian News MediaDocument11 pagesGood, Bad or Absent: Discourses of Parents With Disabilities in Australian News MediaKmiloAndrésAbelloCarrilloNo ratings yet

- Vawc Case StudiesDocument106 pagesVawc Case Studieskylexian1100% (4)

- Research Proposal TemplateDocument5 pagesResearch Proposal TemplateSmallz AkindeleNo ratings yet

- Ethnonational Terrorism:: An Empirical Theory of Indicators at The State Level, 1985-2000Document24 pagesEthnonational Terrorism:: An Empirical Theory of Indicators at The State Level, 1985-2000Ionuţ TomaNo ratings yet

- Toward Empirical Politicide Genocide PDFDocument14 pagesToward Empirical Politicide Genocide PDFEliza SmaNo ratings yet

- Affirmative - Becoming Queer - OE 2022-3-1Document140 pagesAffirmative - Becoming Queer - OE 2022-3-1noNo ratings yet

- Sluka ChomskyDocument3 pagesSluka ChomskyKaralucha ŻołądkowaNo ratings yet

- TERRORISM: A Challenge To Christian MoralityDocument22 pagesTERRORISM: A Challenge To Christian Moralitysir_vic2013No ratings yet

- Assessment On The Role of International Terrorism in International RelationsDocument16 pagesAssessment On The Role of International Terrorism in International RelationsHanmaYujiroNo ratings yet

- No Lessons Learned From The Holocaust? Assessing Risks of Genocide and Political Mass Murder Since 1955Document18 pagesNo Lessons Learned From The Holocaust? Assessing Risks of Genocide and Political Mass Murder Since 1955cybear62No ratings yet

- Atran - Genesis of Suicide TerrorismDocument7 pagesAtran - Genesis of Suicide TerrorismJuani CastilloNo ratings yet

- Benjamin Cowan Sex and SecurityDocument24 pagesBenjamin Cowan Sex and SecurityJavier Nicolás MuñozNo ratings yet

- 2016 Book StateTerrorStateViolence-2 PDFDocument175 pages2016 Book StateTerrorStateViolence-2 PDFFrancisca Benitez PereiraNo ratings yet

- KVUOA Toimetised 12-MännikDocument21 pagesKVUOA Toimetised 12-MännikTalha khalidNo ratings yet

- State-Sponsored Mass MurderDocument31 pagesState-Sponsored Mass MurderStéphanie ThomsonNo ratings yet

- Intelligence in Combating TerrorismDocument71 pagesIntelligence in Combating TerrorismscribscrubNo ratings yet

- The MIT PressDocument33 pagesThe MIT PressTomescu Maria-AlexandraNo ratings yet

- TerrorismDocument6 pagesTerrorismSteven SutantoNo ratings yet

- Human Rights & Terrorism: An Overview: The "War On Terror" Focused Human Rights IssuesDocument55 pagesHuman Rights & Terrorism: An Overview: The "War On Terror" Focused Human Rights IssueskjssdgjNo ratings yet

- Nation StateDocument23 pagesNation StateSharma RachanaNo ratings yet

- Criminology Notes Unit 4Document5 pagesCriminology Notes Unit 4bhaskarojoNo ratings yet

- Operation Condor: Clandestine Inter-American SystemDocument56 pagesOperation Condor: Clandestine Inter-American SystemMartincho090909No ratings yet

- Pol Sci RPDocument14 pagesPol Sci RPAkshat MishraNo ratings yet

- Political Violence in ArgentinaDocument21 pagesPolitical Violence in ArgentinacintubaleNo ratings yet

- Defining Terrorism: Philosophy of The Bomb, Propaganda by Deed and Change Through Fear and ViolenceDocument21 pagesDefining Terrorism: Philosophy of The Bomb, Propaganda by Deed and Change Through Fear and ViolenceNC YoroNo ratings yet

- Erroris: Reynaldo M. EsmeraldaDocument65 pagesErroris: Reynaldo M. EsmeraldaReginald SibugNo ratings yet

- SUICIDE TERRORISM: IT'S ONLY A MATTER OF WHEN AND HOW WELL PREPARED ARE AMERICA'S LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERSFrom EverandSUICIDE TERRORISM: IT'S ONLY A MATTER OF WHEN AND HOW WELL PREPARED ARE AMERICA'S LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERSNo ratings yet

- Scott Atran - Genesis of Suicide TerrorismDocument6 pagesScott Atran - Genesis of Suicide TerrorismDaryl Golding100% (1)

- Pluto Journals Policy Perspectives: This Content Downloaded From 35.154.245.7 On Sat, 04 Apr 2020 07:56:59 UTCDocument11 pagesPluto Journals Policy Perspectives: This Content Downloaded From 35.154.245.7 On Sat, 04 Apr 2020 07:56:59 UTCKHUSHAL MITTAL 1650424No ratings yet

- 2001 Franc GutierrezDocument18 pages2001 Franc GutierrezAndres GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Terrorism & War On TerrorDocument16 pagesTerrorism & War On TerrorAakash GhanaNo ratings yet

- TerrorismDocument32 pagesTerrorismsbanarjeeNo ratings yet

- Literature Review With CitationDocument37 pagesLiterature Review With CitationAbdullah KhushnudNo ratings yet

- Strahlenfolter - Crimes of World War IV - Persecution and State Terrorism - Electronic HarassmentDocument74 pagesStrahlenfolter - Crimes of World War IV - Persecution and State Terrorism - Electronic Harassmentnwo-mengele-doctorsNo ratings yet

- Final Assignment TERRORISMDocument11 pagesFinal Assignment TERRORISMCapricious Hani0% (2)

- "RACE: ARAB, SEX: TERRORIST" - THE GENDER POLITICS OF POLITICAL VIOLENCE IN THE MIDDLE EAST, Eugene Sensenig/GenderLink Diversity CentreDocument24 pages"RACE: ARAB, SEX: TERRORIST" - THE GENDER POLITICS OF POLITICAL VIOLENCE IN THE MIDDLE EAST, Eugene Sensenig/GenderLink Diversity CentreEugene Richard SensenigNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of International Human Rights Pressures: The Case of ArgentinaDocument28 pagesThe Effectiveness of International Human Rights Pressures: The Case of ArgentinaMartincho090909No ratings yet

- Posen 1993Document46 pagesPosen 1993isacardosofofaNo ratings yet

- Garrison 2004 Defining Terrorism Criminal Justice StudiesDocument22 pagesGarrison 2004 Defining Terrorism Criminal Justice StudiesGabriela RoscaNo ratings yet

- Krueger Maleckova 2002Document45 pagesKrueger Maleckova 2002Usman Abdur RehmanNo ratings yet

- REGILMESAGEHandbook Human RightspreprintDocument19 pagesREGILMESAGEHandbook Human RightspreprintAsha YadavNo ratings yet

- Legal TyrannicideDocument42 pagesLegal TyrannicideDImiskoNo ratings yet

- Copia de James Ron Savage Restraint IsraelDocument29 pagesCopia de James Ron Savage Restraint Israelfranklin_ramirez_8No ratings yet

- Kochi-The Partisan Carl Schmitt and TerrorismDocument29 pagesKochi-The Partisan Carl Schmitt and TerrorismSANGWON PARKNo ratings yet

- Fujii Strength of Local TiesDocument20 pagesFujii Strength of Local TiesLuisaNo ratings yet

- Xix International Crimes and CriminologyDocument26 pagesXix International Crimes and CriminologyGabriel SoaresNo ratings yet

- Terrorism - The Definitional Problem Alex SchmidDocument47 pagesTerrorism - The Definitional Problem Alex SchmidM. KhaterNo ratings yet

- McSherry Operation Condor Clandestine Interamerican SystemDocument30 pagesMcSherry Operation Condor Clandestine Interamerican SystemmadampitucaNo ratings yet

- What Is Terrorism NotesDocument3 pagesWhat Is Terrorism NotesSyed Ali HaiderNo ratings yet

- Notes On Essay of TerrosrismDocument4 pagesNotes On Essay of TerrosrismAhsan ullah SalarNo ratings yet

- 14HHRJ87 NaganDocument36 pages14HHRJ87 NaganMindahun MitikuNo ratings yet

- Social Forces 2006 Robison 2009 26Document18 pagesSocial Forces 2006 Robison 2009 26Agne CepinskyteNo ratings yet

- Reflections On ViolenceDocument38 pagesReflections On ViolenceADITYANo ratings yet

- The Invisible Clash FBI, Shin Bet, And The IRA's Struggle Against Domestic War on TerrorFrom EverandThe Invisible Clash FBI, Shin Bet, And The IRA's Struggle Against Domestic War on TerrorNo ratings yet

- Structural Violence Impact File - DDI 2013 KQDocument7 pagesStructural Violence Impact File - DDI 2013 KQMichael BrustNo ratings yet

- War On Terror Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesWar On Terror Literature Reviewea6p1e99100% (1)

- Constructing SubversionDocument41 pagesConstructing SubversionLeo AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Texto RudolphDocument38 pagesTexto RudolphMariana TurielNo ratings yet

- Humanitarian intervention-на летоDocument16 pagesHumanitarian intervention-на летоesenalinurmaralNo ratings yet

- Citizen Insecurity in Latin American Cities The Intersection of Spatiality and Identity in The Politics of ProtectionDocument18 pagesCitizen Insecurity in Latin American Cities The Intersection of Spatiality and Identity in The Politics of ProtectionMilaNo ratings yet

- On Measuring Political Violence - Northern Ireland, 1969 To 1980Document12 pagesOn Measuring Political Violence - Northern Ireland, 1969 To 1980johnmay1968No ratings yet

- Unmasking The Animal Liberation Front Using Critical Pedagogy Seeing The Alf For Who They Really Are Anthony NocellaDocument10 pagesUnmasking The Animal Liberation Front Using Critical Pedagogy Seeing The Alf For Who They Really Are Anthony NocellaSamuel León MartínezNo ratings yet

- Resolution 9.9: The General Assembly First CommitteeDocument2 pagesResolution 9.9: The General Assembly First CommitteeRohit KishoreNo ratings yet

- Inter IKEA Group CodeDocument9 pagesInter IKEA Group CodeSAIF SULTANNo ratings yet

- The Safe Spaces Act InfographicDocument1 pageThe Safe Spaces Act InfographicLanlan SaligumbaNo ratings yet

- Timeline of Sexual Abuse CasesDocument24 pagesTimeline of Sexual Abuse CasesMaxResistanceNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7Document6 pagesChapter 7Matata PhilipNo ratings yet

- Cyber StalkingDocument14 pagesCyber StalkingishitaNo ratings yet

- Ra 7610Document30 pagesRa 7610Cabagan IsabelaNo ratings yet

- Deeper Insights - APPENDIX 1Document16 pagesDeeper Insights - APPENDIX 1Mike Diaz-Albistegui100% (1)

- Brandon DorfmanDocument9 pagesBrandon Dorfmanapi-240940882No ratings yet

- Research Project of Law of TortsDocument11 pagesResearch Project of Law of TortsKumar MangalamNo ratings yet

- Nature and Scope of TortDocument5 pagesNature and Scope of TortNayak Prem KiranNo ratings yet

- Criminal LawDocument81 pagesCriminal LawStephany PolinarNo ratings yet

- NuisanceDocument10 pagesNuisanceAshutosh SharmaNo ratings yet

- RA 7610 Child Abuse LawDocument23 pagesRA 7610 Child Abuse Lawjemyy7191No ratings yet

- Legal Opinion On RapeDocument3 pagesLegal Opinion On RapeJulo R. TaleonNo ratings yet

- Special Penal LawsDocument115 pagesSpecial Penal LawsZannyRyanQuiroz100% (4)

- Oakley Doc TortDocument14 pagesOakley Doc TortYash Vardhan DeoraNo ratings yet

- Content Law of Torts July2016Document12 pagesContent Law of Torts July2016PramodKumarNo ratings yet

- Rebecca Lave - Its Time To Recognize How Mens Careers Benefit From Sexually Harassing Women in AcademiaDocument6 pagesRebecca Lave - Its Time To Recognize How Mens Careers Benefit From Sexually Harassing Women in AcademiaNubia Beray ArmondNo ratings yet

- A Quiet End To The Death Penalty in LebanonDocument3 pagesA Quiet End To The Death Penalty in LebanonJoshSaabNo ratings yet

- Module 9 Personal RelationshipsDocument9 pagesModule 9 Personal RelationshipsJulie Mher AntonioNo ratings yet

- Pornography Research PaperDocument7 pagesPornography Research Paperapi-302641090No ratings yet

- GBVDocument11 pagesGBVSsentongo NazilNo ratings yet

- Capital Punishment Research PaperDocument3 pagesCapital Punishment Research PaperAdeola KofoworadeNo ratings yet

PionBerlin VictimsExecutionersArgentine 1991

PionBerlin VictimsExecutionersArgentine 1991

Uploaded by

caitlinsarah12342Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

PionBerlin VictimsExecutionersArgentine 1991

PionBerlin VictimsExecutionersArgentine 1991

Uploaded by

caitlinsarah12342Copyright:

Available Formats

Of Victims and Executioners: Argentine State Terror, 1975-1979

Author(s): David Pion-Berlin and George A. Lopez

Source: International Studies Quarterly , Mar., 1991, Vol. 35, No. 1 (Mar., 1991), pp. 63-

86

Published by: Wiley on behalf of The International Studies Association

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2600389

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

The International Studies Association and Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to International Studies Quarterly

This content downloaded from

150.203.68.98 on Sun, 08 Oct 2023 00:56:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

International Studies Quarterly (1991) 35, 63-86

Of Victims and Executioners: Argentine State

Terror, 1975-1979

DAVID PION-BERLIN

The Ohio State University

AND

GEORGE A. LOPEZ

The University of Notre Dame

Scholars have found that state terror has been employed frequently against

subdued, if not fully compliant, populations. Scholars have argued that

regimes may attack groups whose characteristics seem incongruent with

their own ideological agendas. Having fully internalized a set of doctrines,

and being prone to exaggerate the extent and depth of the security threats

facing them, authoritarian regimes may provoke long periods of unre-

strained, disproportionate and unnecessary state terror. Drawing from the

recent scholarly attempts to stipulate the conditions associated with the

appearance of state terror, we delineate two major ideologies which have

guided the Argentine military to perpetrate state terror as standard policy.

In national security and free market ideologies, we claim, the Argentine

rulers of the Proceso period found the rationale for making the disappear-

ance of real and perceived adversaries a daily governmental routine. Com-

bined, these ideologies provided motives to sustain high levels of repression

and guidelines to select its victims. We examine social characteristics of the

victims of Argentine state terror and analyze organizational and legal forms

of coercion to reveal patterns that are consistent with ideological predisposi-

tions. We then demonstrate that individuals suffered a greater probability

of victimization if they were members of particular trade unions perceived

by the government to have obstructed its achievement of economic and

security goals. These and other trends lead us to conclude that ideology was

a motivating force behind the infamous Argentine "Dirty War."

Introduction

State terror is a premeditated, patterned, and instrumental form of government

violence.' It is planned, inflicted regularly, and intended to induce fear through

I To enhance stylistic variation, the terms state terror, political repression, and human rights abuses will be used

interchangebly in this paper. We are acutely aware of the differences in meaning these terms have, however slight

they may be. Repression refers to the use or threat of use of coercion by governing authorities to control or

eliminate opposition. State terror is a subset of repression, designed to inflict fear in a target population-(in order

to control their behavior)-by physically harming a victim with which the target population readily identifies

Human rights abuse is a normative expression, conveying the fact that a wrong has been committed in repressing

or terrorizing a victim. These terms are obviously closely associated with one another.

Authors' note: We gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper provided by

Michael Stohl, Rhoda Howard, Scott Mainwaring, E. Ladd Hollist, John McCamant, Carol Stuart, Caroline

Domingo, and anonymous reviewers of ISQ.

X 1991 International Studies Association

This content downloaded from

150.203.68.98 on Sun, 08 Oct 2023 00:56:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

64 Of Victims and Executioners

"coercive and life threatening action" (Gurr, 1986:46). Though most scholars can

agree on these features, each new instance of state terror in the twentieth century has

spawned a set of nagging questions for the research community. First, why have so

many individuals become victims of the most severe form of intimidation and pun-

ishment, when less harsh forms of political coercion would have sufficed to control

them? Second, why are the worst forms of state terror often reserved for those who

engage in no form of protest or hostile action against the regime? Finally, how and

why are these non-dissenting populations singled out for victimization (Arendt,

1951; Kelman, 1973; Fein, 1979; Kuper, 1981)?

In certain cases, the espousal of invidious doctrines, coupled with the clear, public

identification and stigmatization of specific religious (Nazi Germany), ethnic (Bu-

rundi), or racial (South Africa) populations, make the selection of victims, if not the

choice of terror as a policy instrument, somewhat comprehensible. But in other

instances, both the choice of terror and the selection of victims seem unfathomable.

Such is the case of Argentine state terror under the military regime of the Proceso de

Reorganizacion Nacional (PRN or Proceso), which ruled from 1976 to 1983. During this

period of military rule known as the "Dirty War," an estimated 15,000 citizens

remain unaccounted for or are known to have been killed. This infamous time was

marked by numerous acts of state terror, the most frequent of which were disappear-

ances.2

International human rights offices were flooded weekly with reports of the abduc-

tions, murders and disappearances of a diverse mixture of citizens: teachers, scien-

tists, workers, clergy, professionals, even housewives and children. Apparently there

were no clear ethnic or religious patterns to these atrocities, and certainly no racial

ones in this overwhelmingly white population. Moreover, most of the victims had

never engaged in any political activity, let alone activity of a clandestine, violent, or

radical nature. The guerrilla forces, which had posed a security problem, were firmly

rebuked by the end of 1975 and could only commit sporadic and futile acts of urban

terror by early 1976. Rather telling is the fact that nearly seventy percent of the

disappeared were abducted in the privacy of their homes or while peacefully assem-

bled at work. Only twenty-five percent were arrested on the street, where they were

at least in a position to have publicly dissented (CONADEP, 1986:11). The state-

inflicted human rights abuses were scattered and, with a kind of Orwellian logic, the

agents of the military government seemed to strike arbitrarily, unpredictably, and

nearly everywhere against the alleged "enemies of the state."

The striking similarity of the depictions by survivors, friends, and perpetrators of

the methods of abduction and the severity of treatment gives weight to the idea that

this state terror was not only deliberate but centrally planned. In its investigation the

presidentially-appointed Argentine National Commission for the Disappeared

(CONADEP) has identified some 340 concentration camps hidden behind the walls

of military and police installations. Legal records show that the physical and psycho-

logical abuse of political prisoners committed in the camps occurred with the knowl-

edge-and in most instances under the direct supervision-of superior officers.

This lends weight to the argument that the "Dirty War" was an intended policy of

state.

If state terror was intentionally inflicted, then what motivated the Argentine gen-

erals to take such a course of action? In this study, we argue that Argentine state

terror was induced by the ideological beliefs of the junta leaders. More specifically,

the commitment to high levels of violence as a cornerstone of policy is best explained

2 A full account of the events leading up to the Proceso and of the Proceso itself will not be offered here, since the

subject has already been treated adequately elsewhere. See Schvarzer (1983), Waldmann and Garz6n (1983),

Simpson and Bennett (1985), and Buichanan (1987).

This content downloaded from

150.203.68.98 on Sun, 08 Oct 2023 00:56:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DAVID PION-BERLIN AND GEORGE A. LOPEZ 65

by the regime's adherence to two distinct yet related doctrines. The first, an Argen-

tine variant of the national security doctrine, licensed broad and continuous attacks

against perceived "enemies of state" by claiming that the nation was embroiled in a

state of permanent or total war. In succumbing to the logic of war, which produced a

simplistic and even dichotomous view of the Argentine polity, the military junta

found a warrant to conduct an extensive campaign of terror.

Although state terror was pervasive, it also had its focal points. The second ideol-

ogy, a doctrinaire version of free-market economics, guided the state's hand in its

systematic selection of victims. Through an examination of data on the social charac-

teristics of the Argentine desaparecidos or disappeared, we find that repressive activity

can in part be associated with the collective affiliations of its victims. Based on its own

economic biases, the state systematically targeted members of unions perceived to be

opposed to the achievement of governmental economic objectives. Together, then,

these security and economic ideologies provided a motivation for the use of excessive

levels of state violence by the regime and the identification of the victims of such

violence.

Theories of State Terror

Although it still lags behind the prevalence of the phenomenon itself, our knowledge

of why governments terrorize their own populations has grown considerably over

the past decade (Duff and McCamant, 1976; Goldstein, 1978, 1983; Pion-Berlin

1983, 1988; Stohl and Lopez, 1984, 1986; Howard, 1986; Mason and Krane, 1989).

This literature has steadily narrowed the frame of reference from variables operative

in the wider political environment to more detailed analyses of government strategy

and elite decisions in order to name the conditions tLinder which national leaders and

their designated agents employ techniques of terror (Stohl and Lopez, 1986). De-

spite insights into the context and cost-benefit calculus of state violence, little has

been done to posit the specific belief systems that motivate state terror.

Other analysts have identified the decisional settings, pressures, and rules that

explain reliance on terror. Stohl and Lopez (1984) suggest that the resort to terror is

a policy choice made under particular national circumstances: either (1) when the

resident ruling group engages in a drive for control greater than what most observ-

ers would claim necessary for them to maintain power or (2) when the resident

ruling group is faced with institutional (usually non-violent) or extra-institutional

(usually violent) challenges to its power that cannot be eradicated through minimal

levels of force.

In their attempt to develop a more precise calculus of decision making, Duvall and

Stohl (1988) argue that ruling elites opt for terror when they perceive it to be a

useful, efficient, and uncostly tool to achieve desired ends. Operating from the

premise of rational choice, the authors assert that prior to resorting to state violence

decision makers calculate their relative capabilities and vulnerabilities as well as the

probability of achieving desired ends with minimal costs.

However reasonable and persuasive such a proposition may be in the abstract, it

seems less appropriate to the study of unprovoked terror against compliant popula-

tions. If an opposition is unarmed and relatively defenseless, then why should a

military regime bother with calculation of risk? Both the uncertainties and the costs

involved in the use of coercion should be minimal in light of the overwhelming

resource advantages the regime enjoys. Military regimes are much less preoccupied

with public image than are democratic regimes. They are quick to confer upon

themselves legitimacy by virtue of their "historic mission" and assumption of state

power. Furthermore, ruling elites are unlikely to bother with utility calculations in

the development of policy unless they have already been sufficiently motivated to

This content downloaded from

150.203.68.98 on Sun, 08 Oct 2023 00:56:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

66 Of Victims and Executioners

consider so drastic a policy as unmitigated terror. A zealous determination to accom-

plish a mission and a faith in terror as a policy instrument may, in fact, obscure the

potential costs or risks involved from the policy maker's view. Thus, the issue of

underlying motive has eluded prior studies and demands considerable systematic

analysis.

Discovering motive may be even more pronounced a problem in the Argentine

case because a veil of secrecy still shrouds much of the armed forces' operations. So

far as we know, the military kept no records of their work, rarely brought formal

charges against their victims, and seldom accused them of violating laws. Moreover,

since the disappeared are all presumed to be dead, there can be no first-hand corrob-

oration of theories as to why each individual was detained, tortured, and/or exe-

cuted. Ideally, we would want to have the military's accounts of their prisoners'

alleged wrongdoings and the prisoners' statements of defense. In this manner, we

could create a general view of terror through the compilation of specific details. This

kind of information is simply not available. We do know, however, a great deal about

the ideology of those leaders who directed the Proceso Government, including their

view of the threat facing Argentina and their thoughts about the economy they

managed. In these two ideologies, one concerning the general polity and the other

the economy, we have what Gurr has termed the "identifiable cultural, ideological,

and experiential origins of state terror" (1986:65).

The Case for Ideology as a Source of Terror

Scholarship

Nearly forty years ago, Hannah Arendt first proposed that unprovoked terror could

find its origins in the ideological dispositions of state leaders (Arendt, 1951:6). The

purpose of totalitarian ideology was to construct a "fiction" about the nation's ills that

elites and masses alike would readily consume (1951:341-53). As Arendt explains,

the doctrine was fully internalized by the Nazis. Devoid of factual content, their anti-

Semitic doctrine was nonetheless touted as scientific, prophetic, and infallible, turn-

ing the extermination of Jews into a matter of historical necessity (1951:339): " The

assumption of a Jewish world conspiracy was transformed by totalitarian propa-

ganda from an objective, arguable matter into the chief element of the Nazi reality;

the point was that the Nazis acted as though the world were dominated by Jews and

needed a counterconspiracy to defend itself" (1951:352). Arendt added that this

brand of terror "continues to be used by totalitarian regimes even when its psycho-

logical aims are achieved; its real horror is that it reigns over a completely subdued

population" (1951:335).

Arendt's insight has received little attention and virtually no testing over the years.

The generation of scholars to which she belonged who were critical of totalitarian

rule themselves, earned well-deserved criticisms for their simplistic, deterministic,

and polemical accounts of communist tyranny. Arendt's own study of Nazi and

Stalinist terror fell into a genre obsessed with the inherent evils of totalitarian rule. It

failed to recognize the significant variations in political coercion found within com-

munist states. And yet, despite this weakness, her more general point about ideologi-

cally-induced terror is still relevant for contemporary scholars.

More recently, others have acknowledged the importance of ideology as an impe-

tus for genocide against non-hostile populations (Fein, 1979, 1984; Kuper, 1981),

but no one has concentrated on non-genocidal forms of state violence. Second,

ideological genocide as defined by these authors refers mainly to the dehumaniza-

tion of minorities, scapegoats, or other communal groups perceived to be different

from the dominant civilization; it does not include persecution of minorities or non-

This content downloaded from

150.203.68.98 on Sun, 08 Oct 2023 00:56:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DAVID PION-BERLIN AND GEORGE A. LOPEZ 67

minorities defined by economic, political, or social position or opposition. Most re-

cently, Harff and Gurr (1988) have made an important analytical distinction between

genocide, where victims are defined by communal characteristics, and politicide,

where victims are defined "primarily in terms of their hierarchical position or politi-

cal opposition to the regime and dominant groups" (1988:360). Their ideological

variant of politicide, however, is restricted to Marxist-Leninist regimes that stigma-

tize their opposition with association with the old order or for lack of revolutionary

zeal. This does not allow us to uncover the ideological motivations and cognitive

mechanisms behind right-wing authoritarian terror as it occurred in countries like

Argentina, Uruguay, and Chile.

Aiguments

The search for ideological determinants of state terror must inevitably confront the

objection that rulers use ideological jargon simply to conceal the "real" motives

behind their political actions.3 These cunning disguises have no inherent value be-

cause they originate in underlying motives driven by pursuit of political and/or

economic advantage. Social science explanations can and should "bypass" the ideo-

logical prism by identifying the appropriate set of interests to be served by political

terror.

At issue is whether rulers accept rather than simply use the ideological precepts

they espouse (Markoff and Duncan Baretta, 1985). Are ideological pronouncements

demonstrations of conviction or simply ad-hoc rationalizations for political deci-

sions? This is an empirical question. There is no a priori reason to assume that ruling

elites are either uniformly instrumental on the one hand or purely principled on the

other. Undoubtedly investigations across regimes and time periods would reveal

instances of ideological commitment on one level and expediency on another. At the

same time examples would be found where self interest and ideological conviction

coexisted and were mutually reinforcing. Based on analysis of written discourse and

interviews with members of the Proceso government, it is our best judgment that

Argentine elites of the time did embrace their ideological precepts (to be described

below), though these were also consistent with their own political agendas. Therefore

ideology tended to be self-serving.4

In those instances where strong ideological commitment is found, it is worth not-

ing Robert M. Maclver's observation that though "man spins about him his web of

myth," that myth "mediates between man and nature. From the shelter of his myth

he perceives and experiences the world" (Rejai, 1971:5). Insofar as political agents

predicate their decisions, as well as their perceptions on their interpretations of

political reality, those interpretations should be the subject of social science's scru-

tiny. Unquestionably ideologies may mystify a subject's view of his or her political

surroundings. But as Helen Fein (1979:8) points out, regardless of how irrational

policy decisions based on exaggerated or even fictionalized accounts of political

reality (as in the case of Nazi Germany) may appear to be, they should be considered

"goal oriented acts from the point of view of their perpetrators" (emphasis ours). Mass

3 A classical (and non-Gramscian) Marxian analysis, for example, would argue that ideas are simply instruments

which elites may use to win broader support or compliance for the prevailing order (Tucker, 1972:136).

4 There are two strong reasons to believe that ideological conviction did exist in the Proceso government. First,

the ideas that were expressed were not conveniently invented just prior to the onslaught of terror. They had

permeated the ranks of the military years before and were elaborated upon in military journals, speeches, and

hemispheric security conferences. Second, the elites did not abandon their views when they were no longer

needed. Even during current episodes of relative calm under democratic rule, officers and civilians have continued

to repeat the same security themes espoused during the "Dirty War" (Viola, 1984, Martinez de Hoz 1994).

This content downloaded from

150.203.68.98 on Sun, 08 Oct 2023 00:56:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

68 Of Victims and Executioners

murder is always a calculated choice by policy makers based upon the pursuit of

specific objectives. This obtains even where such objectives are ideologically derived

(Fein, 1979).

Once ideologies are assimilated, they serve as a "map" of social and political reality

for policy makers who would rather rely on these few guiding principles than be

forced to make new and diverse judgments in an uncertain environment (Knorr,

1976). Those maps sharpen some images of the political landscape while blurring

others, facilitating the selection of information and then decisions by greatly simpli-

fying a complex and problematic political situation. Of course policy makers nor-

mally engage in some degree of simplification (Jervis, 1976). The danger lies in a

rigid adherence to ideologies that are fundamentally discordant with objective events

(Knorr, 1976:85). Ideologies that are conceptually flawed, anachronistic, or simply

incompatible with contemporary reality are sure to inaccurately map the political

terrain of elites. Exaggerated or implausible accounts of national conditions are then

fully accepted, thus turning into an imperative the excessive use of violence by the

state against complacent populations.

We maintain that the Argentine regiine's relentless witch hunt against a relatively

compliant citizenry was motivated by a structured and yet misinformed set of expla-

nations of Argentine reality. Ideological beliefs shaped the military's cognitive

framework: security-related problems and their origins were identified, victims were

targeted, and strategies chosen. Prompted by ideology, the military turned a limited

battle against rebel units into an unnecessary and large-scale repression of the gen-

eral population. Notwithstanding our conviction that this policy of overkill was un-

necessary, it is evident that the military's ideological maps of reality were substan-

tively meaningful for them. For that reason, there should be links between the

substance of the military's ideology and its subsequent actions.

What follows is a discussion of two ideologies that we believe to have guided

Argentine state terror (Pion-Berlin, 1983, 1988; Lopez, 1986). The first, the Na-

tional Security Doctrine (NSD), provided the authorization for unmitigated state

violence against citizens. The second, a free-market ideology, provided a focus for

the selection of certain victims. To identify the specific Argentine variant of these

doctrines, we made a qualitative assessment of governmental discourse. Our proce-

dure was to review the political, security, and economic components of as many

military documents, speeches, press conferences, and interviews of the period as

were available. For example, all of the speeches and press interviews and some secret

directives of military president Jorge Videla (1976-1980) that were available (1976-

1977, 1979) were examined. A second source of information was magazine inter-

views with and editorials by General Ram6n Camps, who acted as a frequent ideolog-

ical spokesman for the military. As a former chief of police for Buenos Aires

Province, he was the person most responsible for the detention and disappearance of

individuals in the nation's populous capital. Because Argentina's was an institutional-

ized military regime, all remarks by individual officers of the state had the official

endorsement of the junta. Thus we can be confident that views expressed by these

two important officers reflected the opinion of the regime itself.

We read institutional documents as well, including the initial proclamation issued

by the junta upon assuming power in March of 1976, and the official document

justifying the junta's involvement in the Dirty War, published in La Nacz6n on April

29, 1983. For economic themes in particular, all of the speeches and press confer-

ences of the economics minister, Dr. Jose Alfredo Martinez de Hoz, were examined

(from April 1976 to March 1981). Finally, we analyzed legal statements made during

the human rights trials of 1985 by and on behalf of former junta members Roberto

Viola and Basilio Lami Dozo. In all cases we took note of those security and economic

themes most frequently repeated and emphasized by the military government. It

This content downloaded from

150.203.68.98 on Sun, 08 Oct 2023 00:56:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DAVID PION-BERLIN AND GEORGE A. LOPEZ 69

soon became apparent that individual statements were part of larger ideological

mosaics about national security and economic progress.5

The NSD and State Terror

With roots planted in French, North American, and Latin American military litera-

ture and goyernmental policy, the NSD is a set of ideas and principles about achiev

ing national security (Comblin, 1979; Tapia Valdez, 1980; Arriagada, 1981). All

states are security conscious, but within the NSD national security assumes over-

whelming importance. It becomes the yardstick by which policy success is measured,

and the beginning and the end of political life itself. The state, as the central institu-

tion of society, is charged with guaranteeing that security, and state managers are

therefore granted special prerogatives (Arriagada, 1980). In this regard the NSD is

obviously elitist, since it emphasizes the right of state authorities alone to decide the

public good. The achievement of national security objectives is often at odds with the

protection of individual freedom (Comblin, 1976). This tension is usually resolved in

favor of national security, as individual rights are illegally, repeatedly, and flagrantly

violated at the hands of the state. In that respect the NSD is authoritarian. It is

infused with ideological norms that attack Marxist principles and defend Western-

Christian values. It is strategic in refocusing the attention of the armed forces on

combating unorthodox forms of internal aggression that threaten national security.

Finally, it presumes that development and security are dependent upon one another

(Lopez, 1986).

In some sense the NSD in the 1970s became a generic ideological framework that

various Latin American military establishments have revised, reinterpreted, and se-

lectively borrowed from to suit their own needs. The Argentine variant of the NSD

had its genesis at the intersection of two external currents of thought. The first

current was French, which found its way to Argentina in the late 1950s with the visit

of military missions to Buenos Aires. The French, deeply entrenched in counterin-

surgency operations in Algeria, spoke from experience when they urged the Argen-

tines to confront the communist threat in a similar manner. They were taken very

seriously by those officers who were trained and indoctrinated into military life at

about that time and who would later rule during the Proceso. Despite the relative

calm Argentina enjoyed at the time and the populations' strong reluctance to affiliate

with parties of the left, a flurry of articles (some authored by French officers) soon

appeared in Argentine military journals, such as the Revista de la Escuela Superior de

Guerra, warning of the country's vulnerability to international Marxism. At the time

however, these views did not circulate much beyond the walls of military libraries and

barracks, and they certainly were not endorsed as official defense policy.

The second current of thought was North American. By the early 1960s the

specter of communism had come to haunt the Latin American military establish-

ments in the form of the Cuban revolution. Castro's victory induced the Kennedy

administration to undertake a thorough revision of U.S. security doctrine in the

region. What emerged was a blueprint for the continental defense of Western demo-

cracies coupled with a rationale for military engagement in domestic security and

development operations. Generally, national defense of territorial borders gave way

to a broader concept of national security that justified Latin American military in-

volvement in the region's politics to arrest external and internal "hostilities" of all

5This assessment is consistent with findings of a previous study about the Argentine military's perceptions of

national security threats (Pion-Berlin, 1988). In that study, the content of military public documents was analyzed

and coded by taking the subiects' repeated use of certain words and their synonyms as evidence of commitment to

one view or another.

This content downloaded from

150.203.68.98 on Sun, 08 Oct 2023 00:56:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

70 Of Victims and Executioners

kinds. Argentine acceptance of the North American doctrine was revealed in 1964

by General and soon to be President Juan Carlos Ongania, who argued that while the

armed forces should normally remain subordinate to the constitutional authorities,

they must reserve the right to intervene should the government fall prey to "foreign

ideologies" and fail to conform to the new conventions of Western Hemispheric

security (1964:756-59). In concert with the U.S. security doctrine, Ongania had

given his military license to broaden its political role-which was used to overthrow

democratic governments in 1966 and 1976.

As it developed throughout the 1960s, the Argentine variant of the NSD was

notable for its excessive preoccupation with the perceived "agents of disorder"

those groups which would directly threaten national security-rather than with the

underlying structural conditions of underdevelopment that may have contributed to

that disorder. Unlike their Peruvian counterparts, the Argentines were not con-

vinced that the achievement of political stability could await the fruits of structural

change. Sensing more immediate dangers to the political order, the Proceso govern-

ment was determined to achieve security through direct confrontation with a per-

ceived enemy.

In fact, the centerpiece of Argentine security ideology was the principle that a state

of permanent or total war existed within their society (Ludendorff, 1941; Comblin,

1976; Arriagada, 1981). Subscribing to a fundamentally conspiratorial view of the

world, the NSD-minded generals were convinced that they were besieged by commu-

nist agents engaged in an international war against "Western Civilization and its

ideals." Argentina was a major theatre of operations in this ongoing global confron-

tation, often referred to as the "Third World War" (Camps, 1986).

This was an unconventional war whose subversive perpetrators were thought to

operate in disguised form. Having retreated from the conventional military battle-

field, the subversives would penetrate society to conduct multifaceted forms of strug-

gle. As Jorge Videla explains, "We define [subversion] as a global phenomenon that

has a political, economic, social, cultural and military dimension, that based on philo-

sophical or ideological assumptions, tries to penetrate within a population to subvert

its values, create chaos and through these means assume power violently" (1977:8).

Under such conditions, normal geographical and temporal demarcations between

war and peace become blurred, without borders or conclusions. General Roberto

Viola, who commanded the army during the height of the Dirty War and later

became military president, explains: "There were no clear battle lines, no large

concentration of arms and men, no final battle to signal victory" (La Raz6n, 1979:2).

The military turned this conception to its advantage tojustify continuous and broad-

scale counterattacks in its own defense. General Viola comments: "Since the entire

country is besieged by acts of violence, the army command has the inalienable right

to exercise its legitimate defense . . . juridical considerations about the definition of

a state of belligerency, within a revolutionary war, is a problem that is the exclusive

concern of the political leaders of the nation under attack" (1985:553).

Convinced that the enemy's chameleon-like transformations would prolong its life

span indefinitely, the Argentine military thrust itself into permanent combat readi-

ness (Comblin, 1976; Arriagada, 1981). Referring to the enduring and yet partially

concealed nature of this conflict, former Air Force General Basilio Lami Dozo said:

This aggression has not ended. The return of Argentina to constitutional rule has

demanded of the international Marxian movement and its affiliated organizations

designated to operate in our country [that they adopt] new strategies and tactics"

(1985:572).

The logic of war within this permanent struggle dictated that political life be

subordinated to the demands of combat. This produced a simplistic and dichoto-

mous view of the Argentine polity. Those who refused to demonstrate loyalty to the

This content downloaded from

150.203.68.98 on Sun, 08 Oct 2023 00:56:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DAVID PION-BERLIN AND GEORGE A. LOPEZ 71

military and its government were declared in opposition to the regime and the state

itself. Those placed in opposition were treated as implacable enemies who must

consequently be eliminated rather than won over.

Typical of the response of state leaders during war, characterizations of political

foes were hostile and demeaning (Keen, 1986). Adversaries were frequently referred

to as subversives or terrorists, terms normally reserved for those thought to be

unscrupulous in their tactics and irredeemably immoral in character (Videla, 1979).

Willing to resort to any means to pursue ignominious ends, these foes could neither

be trusted to abide by negotiated settlements nor be permitted to remain even as

vanquished members of society. Only their complete extermination would ensure

the military's perceived need for total security. As Videla stated, "With the objective

[of securing social peace] we will combat, without respite, subversive delinquency in

all of its forms until its total annihilation" (1979:6). The armed forces were unwilling

to admit that relations with political foes could improve, that adversaries on one issue

could be allies on another, or that dissidents could redeem themselves. Their view

was politically blind and tended "to accelerate compulsively to the point of greatest

violence" (Arriagada, 1980:58).

In these two recurrent and interconnected themes, the condition of permanent

war and the logic of combat, we have what Herbert Kelman (1973) has referred to as

the loss of restraints against violence. In assuming that a condition of permanent

internal war existed, the Argentine national security ideology offered the military a

warrant for extensive and continuous terror in the name of protecting the nation. In

presenting combat as the operative form of engagement, the ideology justified the

routinization of terror. As mutually reinforcing tendencies, these themes made state

terror the cornerstone of governmental policy.

In sum, the regime employed a process of ideological deduction. It began with the

premise that national security is the state's paramount objective. It then defined the

security dilemma within a framework of permanent war. From there, particular

views about the polity and the opposition were formulated, as were the problems and

threats associated with the state of permanent war. Given these premises and the

perception of threat that they generated, the decision to use coercion became a

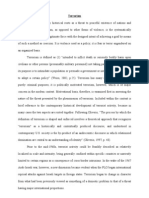

logical conclusion. This cognitive process is diagrammed in Figure 1.

What the NSD failed to do was to specify with precision who the targets of state

terror would be. Certainly those who taught and were taught "subversive" social and

political doctrines (teachers and students), those who questioned the legitimacy of

military rule (journalists), and those who were perceived to have compromised loyal-

ties to the Argentine nation (Jews) were suspect. But it is apparent from its own

pronouncements that the military was vague in its identification of the opposition.

According to President Videla himself, a subversive is "anyone who opposes the

Argentine way of life" (Simpson and Bennett, 1985:76). This discourse suggests that

state terror may have had an indiscriminate dimension which we will discuss later.

But it also masks the fact that the junta's campaign of terror had focal points as well.

To understand how some victims were singled out, we turn to the regime's economic

ideas.

The Economic Ideology of State Terror

The Argentine regime subscribed to a doctrinaire version of monetarist or free-

market economics found throughout the Southern Cone region of Latin America at

the time but by no means universally adhered to elsewhere (Vergara, 1984; Sheehan,

1987). These monetarists shunned even the most limited forms of government inter-

vention in markets which they believed to be inherently stable. Second, they were

obsessed with inflation and its causes, waging an eclectic battle against wage in-

This content downloaded from

150.203.68.98 on Sun, 08 Oct 2023 00:56:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

72 Of Victims and Executioners

Ideology National security doctrine

r f Dichotomous view of polity

Views Permanent war thesis Opponents are enemies

Logic of combat Dehumanization of enemies

fl r Threats to:

Problem Revolution iF e Nation

Idetfcto uvrineRgm

Problem Subv~ersions Regimae

Ij Development

Target VaIeSee economic ideology for

Specification Vague specification

Threat perception a

Strategy High levels of terror

FIG. 1. National security ideology and the deduction of state terror.

creases, monetary expansion and fiscal irresponsibility. Though the military could

not claim any economic expertise, many officers were quickly enticed by the mone-

tarists' assertions that they had the most scientific, rational, and effective response to

the economic dislocations allegedly caused by labor-based, populist governments.

In particular, the military was irked by the economic practices of the previous

labor-dominated Peronist government, which the junta accused of a "manifest irre-

sponsibility in the management of the economy which had destroyed the productive

apparatus" (Review of the River Plate, 1976:405). In announcing their own plans for

economic recovery-which included specific adjustments such as limitations on gov-

ernment credit and current expenditures and deficits, and a general dismantling of

the state-led economy-the Argentine military was also making a serious indictment

of previous economic practices (Martinez de Hoz, 1981:1-15).

The Argentine military's monetarist economic team was obsessed with what it

perceived to be the excessive expansion of the state's economic functions (Review of

the River Plate, 1977:441.) The state, in its view, had wrongly assumed the burdens of

subsidizing poorly run firms, retaining unprofitable state owned enterprises, and

preserving and expanding public-sector employment. All of these unproductive ac-

tivities placed enormous strains on the federal budget, whose deficits were the force

behind Argentine inflation according to the monetarists (Martinez de Hoz, 1981: 1 -

15). The military's inherited excess of public spending over income was particularly

bothersome since it was attributed to "irrational" social and political pressures and

not to "rational" economic thinking (Estrada, 1984).

The functions of the Argentine state had, according to the military's economic

team, increased in proportion to the demands placed upon it by Peronist trade

This content downloaded from

150.203.68.98 on Sun, 08 Oct 2023 00:56:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DAVID PION-BERLIN AND GEORGE A. LOPEZ 73

unions. Collective pressures had 1) forced state protection of highly unionized firms,

2) established the public sector as a refuge for workers displaced by the market, and

3) politicized price, wage, and managerial decisions. Each new state program not

only strengthened the trade union movement but stood as a reminder for future

governments that fiscal contraction could not be achieved without severe political

consequences. Unwilling or unable to bear the political costs of an austerity program,

"weak" democratic and authoritarian governments allowed the "irrational" alloca-

tion of public resources to persist unabated. Consequently, according to the eco-

nomic liberals, trade unions, weak government, and economic decline were three

sides of the same triangle.

It would have taken a regime thoroughly committed to free-market philosophy-

and prepared to use high levels of force-to weaken labor's grip on the state. At-

tempts had been made before, but none was as ambitious as those undertaken by the

Proceso government. The government's objective was to transform radically the Ar-

gentine economy and then to force the labor movement into the Procustean bed of a

free market. First, it proposed privatization, turning state entrepreneurial functions

over to the business sector. In those instances where transfer was not possible owing

to the complexity of the system or to its massive indebtedness, the firm would be

scaled back: deficits would be gradually eliminated by raising public service and

utility rates, cutting back operating costs, and eliminating surplus employees. Re-

strictions on state activities would achieve the ultimate objectives of lower deficits, less

monetary emission, and lower inflation. Second, it stripped away protective trade

and investment barriers and opened Argentina to the international economy (Cani-

trot, 1980; Ferrer, 1980; Schvarzer, 1983). The social objective of these economic

moves was to narrow the base and weaken the clout of Argentina's labor movement

by reducing opportunities for state-subsidized employment (Canitrot, 1980; Delich,

1983) and by exposing heavily unionized industries to the pressures of international

competition (Buchanan, 1987).

The military were only too anxious to cripple a movement that they believed had

intentionally undermined the foundations of the economy. Whether workers actually

engaged in protest against the monetarist plan or only intended to was not the point.

The regime's economic ideology held that, as collectivized rent seekers with an inher-

ent motive to protect their own interests via the interventionist state and wreak havoc

on the free operations of the market, organized labor was culpable and must be

punished.

If the economic ideology established some general contours for the state's political

strategies, we need more specific information to formulate meaningful hypotheses.

The trade union movement must be disaggregated. Its affiliated syndicates varied

according to their economic position and importance, their size, and their political

clout. Each of these could exert independent and yet related influences upon the

military. For example, harsher treatment might have been meted out for individuals

associated with unions that were larger in size, politically stronger, and more strategi-

cally positioned within the economy. If unionism can obstruct the ebb and flow of the

market through its rent-seeking practices, then larger unions will have greater

monopoly power, making them even more threatening to the regime. Regardless of

size, certain unions exerted a stronger political influence over the labor movement

and thus were more vulnerable to state terror. Others that were neither large nor

politically powerful were still vulnerable to state terror because they controlled jobs

in sensitive areas of the private or public economy that were to be transformed by the

regime's economic plan. In addition, the combined effects of union size, sectoral

placement, and political power upon the judgments of the Proceso government must

be considered.

Thus, beginning with normative premises about freely operating markets and the

This content downloaded from

150.203.68.98 on Sun, 08 Oct 2023 00:56:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

74 Of Victims and Executioners

dangers of state intervention, the regime identified specific problems that prevented

economic growth: collective pressures imposed on government were antecedent;

public sector expansion, inefficiencies, deficits, inflation, and poor growth were de-

rivative. Next, the "agents of economic destruction" were perceived to be threaten-

ing to the economic order and were identified. Given the perceived dangers, the

regime then decided to resort to state terror. The process is shown in schematic form

in Figure 2.

Ideological Links

Though separate and distinct, the national security and economic ideologies of the

Argentine military regime were related and, at times, mutually reinforcing. Accord-

ing to the junta, economic stability could not be achieved without national security,

but neither could security be made permanent without economic stability (Junta

Militar, 1979:79-80). It is no coincidence that the military's view is reminiscent of

Ideology

Free market economics

Views

Anti-statist

Anti-collectivist

IZIE ZI Protectionism

Problem Public sector expansion

Identification Collective pressures Inefficiencies

Inflation

Poor economic growth

Target Collectivities:

Specification * Large

* Politically powerful

* Strategically placed

Threat perception

Strategy

Terror

FIG. 2. Economic ideology and the deduction of state terror.

This content downloaded from

150.203.68.98 on Sun, 08 Oct 2023 00:56:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DAVID PION-BERLIN AND GEORGE A. LOPEZ 75

former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara's own proclamation about the

Third World that "security is development and without development there can be no

security" (1968:149).

Though these links existed, the Proceso Government never emphasized develop-

ment as strongly as did the North American proponents of the NSD. It preferred

short-term economic adjustments to long-term economic planning. These adjust-

ments could be achieved by pressing the right macro-economic policy levers to mini-

mize state interference in the economy while providing the appropriate mix of

rewards and sanctions to the nation's producers. Still, such adaptations were consid-

ered necessary if the nation's security was to be achieved. To the extent that trade

unionists obstructed such measures, they placed in jeopardy the nation's security.

Trade unionists were thought of as domestic sponsors of subversion in league with

international agents of communism. Distinctions between Marxist, guerrilla, and

legitimate working-class organizations seemed to fade quickly in the military mind as

its war against subversion escalated.

The junta's own secret documents on the conduct of the Dirty War reveal that the

struggle against subversion included a special plan to penetrate industrial trade

unions (Videla, 1985) for the purpose of eliminating undesirable elements. Using

the same discourse of combat whether referring to guerrillas or to workers, Presi-

dent Videla called on the regime to carry out its "mission" through the "detection

and destruction of subversive organizations," particularly in the industrial and edu-

cational sectors of the country (Videla, 1985: 530). With the guidance of its economic

ideology, the junta identified particular agents of economic destruction. With the

support of its national security ideology, the junta unleashed a particularly ferocious

campaign of terror against them. Thus, in this instance, the two ideologies inter-

sected to serve the same ends.

Analyzing Patterns of Victimization

The Data

Three forms of data on state terror in Argentina were utilized in this study. The first,

information on the disappearance and eventual execution of political opponents,

was derived from an official list of desaparecidos made available to us by the Asamblea

Permanente Argentina de Derechos Humanos (The Argentine Permanent Assembly for

Human Rights). Founded in 1975, the Assembly's work in defense of human rights

under perilous conditions won it international praise. The Assembly contributed

valuable information on the disappeared to the presidentially-appointed Argentine

National Commission on the Disappeared (CONADEP), which produced the report

Nunca Mds, and it is these data on which we draw for this study. The Assembly's

information includes the name, age, sex, the place and date of apprehension, and, in

many instances, occupational and associational affiliations of some 5,500 individuals.

Since many families were reluctant to divulge all relevant facts about their disap-

peared relatives, we commonly encountered missing data. Moreover, we did not

have any information on the victims' ideologies or their religious or political party

affiliations. This has limited our analysis to social rather than political indicators.6

Nonetheless, an account of the social sphere is fully warranted, since Argentine

terror was disproportionately directed against organized labor. The organized work

force of Argentina comprises 38 percent of the economically active population. Yet

6 However incomplete, these data represent the most complete single source of information to date, on the

victims of state terror in Argentina before and during the period of military rule.

This content downloaded from

150.203.68.98 on Sun, 08 Oct 2023 00:56:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

76 Of Victims and Executioners

48.1 percent of all the disappeared were blue- and white-collar workers. Our proce-

dure was to record those individuals for whom occupational or union identifications

could be made, yielding a total of 2,078 desaparecidos. Since all those listed by the

Assembly were presumed disappeared, we have no variation in terror technique

employed during the repression.

Despite these limitations, there are two advantages to using the Assembly's data.

First, it represents the most reliable data available, since a single organization and its

investigative staff asked the same set of questions about each of the victims. Second,

the Assembly's compilation allowed us to analyze the worst form of abuse committed

against Argentines. Certainly, if some sense can be made of the policy of disappear-

ance, then we will have made a significant step towards understanding the syndrome

of political terror as a whole.

The second kind of data was organizational. We were able to identify those unions

placed under military jurisdiction. Rather than destroy unions, which the govern-

ment feared would invite radical anarchical elements to infiltrate at factory levels, the

armed forces replaced elected union heads with high-ranking military officers. This

intervention suspended most normal trade-union deliberations while retaining

union structures. It is likely that in some instances intervention substituted for the

execution of rank-and-file members, while in other cases intervention and disap-

pearances clearly worked in tandem.

Finally, we examined information on repressive legislation aimed specifically at

state sector unions.

At the individual level, political repression represented the monthly total of per-

sons sequestered by security forces over a 52-month period between 1975 and 1979.

Though the military officially took power in March of 1976, its Dirty War actually

commenced the year before. For that reason, we include repression data from 1975.

Using occupational and union information for most of these victims, we then orga-

nized the monthly figures according to the following queries: 1) Had the victim been

affiliated with the organized labor movement? 2) If so, of which unions were they

members? 3) In which sectors were those unions located? 4) Were the unions politi-

cally important within organized labor?7 To make comparisons, we then divided this

repression data by the relevant standardized unit. Thus, the monthly repression data

for non-unionized workers were calculated as a proportion of the nonunionized,

economically active population as a whole, while the repression of unionized workers

was figured as a proportion of the organized labor force.

Data Analysis

Individual Union Traits. Table 1 examines differences in the repression of union-

ized as opposed to non-unionized individuals for the 1975-1979 period. The sample

of victims includes a wide array of blue- and white-collar workers, professionals,

technicians, scientists, artists, and journalists. As shown, the aggregate repression

rate for unionized individuals was nearly three times that of nonunionized individ-

uals. A difference of means test was then computed on the same repression data,

disaggregated on a monthly basis, for union and non-union affiliates. The average

monthly rate of repression for unionized workers was significantly greater (at a level

of .01) than that of independent workers, ruling out the possibility that such differ-

7The political impor-tance of a union r-efers to its influlence withini the labor imiovemenit anid Peronist pairty. Uniion

reputations have been established either throuIgh a histor-y of comilbativeniess againist authoritariani gover-iniments or

thiough conitr-ol over key positions within the labor conifederation. We conisider-ed both, relyinig oni ail exper-t in

Argentinie labor affair-s who rated LIuliOnls as either- politically impoitant or unimportant. See FerniAndez (1985).

This content downloaded from

150.203.68.98 on Sun, 08 Oct 2023 00:56:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DAVID PION-BERLIN AND GEORGE A. LOPEZ 77

TABLE 1. Repression of union and non-union affiliates, 1975-1979.

Rate of

Level of Population Repression

Group Repressiona Population Size (per JOO,OOO)b

Non-Union 407 Economically Active

Population (Non-Union) 6,175,500 7

Union 771 Organized Labor Force 3,939,000 20

a The difference between these combined figures and the total of 2,078 desapareczdos used in this

study reflects the existence of missing values in the data, where the occupational statuLs of a victim was

known but his or her union membership status was not known.

b Derived by dividing repression levels into population size and then multiplying by 100,000.

Note: Economically active population data is taken from International Labor Organization, Yearbook

of Labor Statistics, 1978-1981; organized labor force data was compiled by totalling membership of all

unions registered with the Argentine Ministry of Labor.

ences were a product of chance. The results suggest that the military government

had indeed distinguished between these two groups of individuals, reserving harsher

treatment for unionists.

Next, as shown in Table 2, we examined the relationship between the size of a

union and the level of repression. We report figures reflecting average union mem-

TABLE 2. Union size and repression of members, 1975-1979 (N = 21).

Union Size as Repression Level

% of Organized Repression as % of Union

Union Labor (A) Level (B)a Size (C)

Metalworkers 6.78 109 16.1

Municipal Workers 6.35 22 3.5

Teachers 4.79 190 39.7

Construction Workers 4.74 75 15.8

Bank Employees 3.96 41 10.4

Railroad Workers 3.64 25 6.9

State Employees Association 2.18 65 29.8

Restaurant Workers 2.17 9 4.1

Textile Workers Association 1.87 34 18.2

Light and Power Workers 1.78 11 6.2

Automobile Transport Workers 1.43 27 18.9

Automechanics 1.37 77 56.2

Telephone Workers and Employees 1.01 14 13.9

Freightworkers 0.99 1 1.0

Traveling Salesmen 0.97 19 19.6

Meatworkers 0.96 15 15.6

Sugar Workers (Tucuman) 0.90 2 2.2

Carpenters 0.84 14 16.7

Wine Industry Workers 0.77 5 6.5

Postal Employees 0.72 2 2.8

State Oil Workers 0.65 14 21.5

Correlations: A with B: Pearsons r = 0

a Repression Level is the number of trad

the military between 1975 and 1979.

This content downloaded from

150.203.68.98 on Sun, 08 Oct 2023 00:56:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

78 Of Victims and Executioners

berships during the Proceso period as a percentage of the total organized work force.

We then list corresponding repression levels (representing the total number of desa-

parecidos for each union for the 1975-1979 period) and percentages. As shown, the

correlation between the size of a union and the level of repression directed at its

members is highly significant. However, the association appears to be spurious-a

function of the fact that there are simply more individuals to terrorize in larger

unions-since the correlation between union size and repression as a percentage of

union size is insignificant. An important relationship nonetheless exists between

union size, monopolistic practices, and rates of repression, discussion of which must

await the analysis of paired union dimensions to be described below.

Aggregate levels and repression rates within sectors are shown in Table 3. If, in its

deliberations about whom to terrorize, the junta considered the sectoral location of

unions to be important, then separate patterns of terror should emerge between

those sectors on the one hand and a miscellaneous grouping of unions on the other.

Considering its biases, we surmise that the junta would have been more preoccupied

with unions and workers situated in strategic social and economic spheres. The

figures indicate that the rate of terror against educators exceeded that in the miscel-

laneous sector by a factor of 3.4, while terror in the manufacturing sector exceeded

miscellaneous terror by a factor of nearly 2. Meanwhile, the miscellaneous terror rate

was slightly larger than that found in the state and transportation/communication

sectors. Again, using the monthly breakdown of this aggregate data, difference of

means tests were performed comparing repression rates in the miscellaneous sector

to rates in each of the others. This was done to determine whether the average

repression score in any one sector was significantly greater than that in the miscella-

neous grouping of unions. If so, we could reject the null hypothesis that such differ-

ences were due to chance and infer that the junta had both distinguished between

these groups and meted out separate degrees of punishment for them.

Not surprisingly, repression rates in the manufacturing and educational spheres

turned out to be significantly higher (at a level of .01) than in others. However,

differences between the miscellaneous sector on the one hand and state and trans-

portation/communication sectors on the other were not statistically significant. The

higher rate of repression in manufacturing is consistent with the theory that the

military was determined to weaken unions in those establishments that were to be

radically transformed by its free-market project, chiefly the heavily unionized and

TABLE 3. Repressioni by union sectors, 1975-1979.

Rate of

Secto- Size Sector Size Repression

bv Numtiber of a's % of Lezel of bv Sector

Secto- Wor-kers Oigazed Labor- Rep-ession l) (1)er 100,000),

Manufacturing 457,877 15.41 248 54

State 614,580 15.61 151 25

EdUcation 188,854 4.79 190 100

TransportatioIn/Conm1i1unication 306,720 6.78 69 22

Miscellan1eoUs 564,970 14.35 165 29

a The suimii of wor-ker-s in thils COIluImn will e

sectolr.

bThe suimil of these r-epr-ession scores will be gr-eater- th<ln suimils for Taibles 2 or- 5 becalLuse three uLn1on0s ari-C sitUated

in nmore than onie sector.

cRatios ar-e derivedl by dlividing repr-essioni levels inito sectoral size and imutiltiplying by 100,000.

This content downloaded from

150.203.68.98 on Sun, 08 Oct 2023 00:56:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DAVID PION-BERLIN AND GEORGE A. LOPEZ 79

protected manufacturing enclaves. Moreover, particular industrial unions were sin-

gled out for especially harsh treatment. As shown in Table 2, the Metalworkers

Union (Uni6n de Obreros Metalirgicos), which was the largest union in manufacturing

and second largest in the nation (comprising nearly 7 percent of the entire organized

work force), bore the brunt of the repression. So too did the very powerful autome-

chanics unions. Together, these syndicates controlled over 320,000 jobs in manufac-

turing enclaves built up during periods of state-subsidized industrialization which

were now to be dismembered by the regime's plan of economic openness.

We find an explanation for the high rates of repression against teachers and

professors in the military's national security ideology. As President Videla explained:

"A terrorist is not just someone with a gun or a bomb, but also someone who spreads

ideas that are contrary to Western and Christian civilization" (Amnesty Interna-

tional, 1978). This reflects the national security doctrine's redefinition of the

counter-subversive war to include a struggle against Argentine educators, who

would be most responsible for producing and reproducing ideas in conflict with the

military's vision of the national security state.

Evidence of the military's alarm about the educational sector was detailed in 1980

in a polemical narrative entitled "Evolution of Terrorist Delinquency in Argentina"

(Poder Ejecutivo Nacional, 1980). The report, which amounted to a specification of

the national security ideology, insisted that terrorism had found its official center in