Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 viewsAmgovx 01 03 Rep Gov Main Lecture 2020 V5-En

Amgovx 01 03 Rep Gov Main Lecture 2020 V5-En

Uploaded by

ClaudiaThe document discusses the history of representative government in the US Constitution from its origins to modern times. It describes how the framers created a bicameral Congress to balance state and population interests, with the House elected by voters and Senate by state legislatures. Over time, reforms increased direct democracy, such as popular election of Senators and the president. Critics argue money's influence in elections and gerrymandering weaken the notion of the House as "the people's chamber."

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- How Democratic Is The American Constitution by Robert A. DahlDocument7 pagesHow Democratic Is The American Constitution by Robert A. Dahlbrucewphillips0% (1)

- For 1943 ConstitutionDocument11 pagesFor 1943 Constitutionernesto pitogo75% (4)

- The Paris Peace Conference, 1919 - Peace Without Victory - (Studies in Military and Strategic History)Document212 pagesThe Paris Peace Conference, 1919 - Peace Without Victory - (Studies in Military and Strategic History)Cora Brumaru0% (1)

- Lesson 1 National Legislature OverviewDocument19 pagesLesson 1 National Legislature OverviewEsther EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Congress Is A Dysfunctional InstitutionDocument7 pagesCongress Is A Dysfunctional InstitutionS VanceNo ratings yet

- 17th AmendmentDocument1 page17th AmendmentBarry BenchNo ratings yet

- Congress Is A Dysfunctional InstitutionDocument7 pagesCongress Is A Dysfunctional InstitutionS VanceNo ratings yet

- Origins of The Electoral College: 45 Comments U.S. Historyphilosophy and Methodologypolitical Theory Randall G. HolcombeDocument9 pagesOrigins of The Electoral College: 45 Comments U.S. Historyphilosophy and Methodologypolitical Theory Randall G. Holcombedbush1034No ratings yet

- The Seventeenth Amendment:: The Folly of The Direct Election of SenatorsDocument22 pagesThe Seventeenth Amendment:: The Folly of The Direct Election of SenatorslarpNo ratings yet

- Greg Abbott - Restoring The Rule of LawDocument92 pagesGreg Abbott - Restoring The Rule of LawBob Price100% (3)

- Restoring The Rule of Law With States Leading The WayDocument92 pagesRestoring The Rule of Law With States Leading The Wayadan_infowars100% (1)

- Examen Eeuu:: 1. "A City Upon A Hill" and Puritan ThinkDocument27 pagesExamen Eeuu:: 1. "A City Upon A Hill" and Puritan ThinkAlexia Vázquez OrgazNo ratings yet

- What Is The Legislative Branch OverviewDocument3 pagesWhat Is The Legislative Branch Overviewapi-241101238No ratings yet

- Washington Times Advert: Obama ID FraudDocument1 pageWashington Times Advert: Obama ID FraudObamaRelease YourRecordsNo ratings yet

- American Gov Hon Research PaperDocument14 pagesAmerican Gov Hon Research Paperapi-596908445No ratings yet

- The Constitution of the United States: Updated for Better Government in the Twenty-First Century Second EditionFrom EverandThe Constitution of the United States: Updated for Better Government in the Twenty-First Century Second EditionNo ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture 1Document20 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture 1cmalone410No ratings yet

- Democracy Vs RepublicDocument4 pagesDemocracy Vs RepublicTony SanchezNo ratings yet

- Electoral College Assignment (AP)Document6 pagesElectoral College Assignment (AP)Philip ArgauerNo ratings yet

- Exposé AnglaisDocument5 pagesExposé Anglaisah.dutilleulNo ratings yet

- CongressDocument16 pagesCongressapi-164891616No ratings yet

- The Political System in The US: Historical DocumentsDocument3 pagesThe Political System in The US: Historical DocumentsRiaz khanNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Foundation Lecture Notes - Part IIIDocument9 pagesConstitutional Foundation Lecture Notes - Part IIIbtharwoodNo ratings yet

- What is a Democracy? US Government Textbook | Children's Government BooksFrom EverandWhat is a Democracy? US Government Textbook | Children's Government BooksNo ratings yet

- Opinion - The Electoral College Was Not A Pro-Slavery Ploy - The New York TimesDocument2 pagesOpinion - The Electoral College Was Not A Pro-Slavery Ploy - The New York TimesASHLEE SALTERNo ratings yet

- Thesis ConstitutionDocument5 pagesThesis Constitutiondiasponibar1981100% (2)

- Political System USADocument16 pagesPolitical System USAHanna100% (1)

- Tyrants in Black Robes: How the Federal Courts Destroyed Our RepublicFrom EverandTyrants in Black Robes: How the Federal Courts Destroyed Our RepublicNo ratings yet

- Government WebQuestDocument20 pagesGovernment WebQuestazeneth100% (1)

- Checks and Balances: A Look at the Powers of GovernmentFrom EverandChecks and Balances: A Look at the Powers of GovernmentRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- 7Document6 pages7pdotvafqeatngzhonpNo ratings yet

- Clements Paper For Senate Hearing - 7-24-2012Document17 pagesClements Paper For Senate Hearing - 7-24-2012mary engNo ratings yet

- Martin - Judges, Lawyers and Other Destroyers (Corrupt Judicial System) (1992)Document38 pagesMartin - Judges, Lawyers and Other Destroyers (Corrupt Judicial System) (1992)scooter123100% (2)

- Tea Party and SecessionDocument3 pagesTea Party and SecessionMichael TheodoreNo ratings yet

- What Is The Doctrine of Incorporation? Why Is It Important?Document7 pagesWhat Is The Doctrine of Incorporation? Why Is It Important?Eka MaisuradzeNo ratings yet

- Adminstrative System of UsaDocument11 pagesAdminstrative System of Usadekha dekhiNo ratings yet

- Citizens United v. FEC DBQDocument4 pagesCitizens United v. FEC DBQMargotNo ratings yet

- How Democratic Is The US Constitution?Document5 pagesHow Democratic Is The US Constitution?paulaNo ratings yet

- Citizens United vs. FEC DBQDocument5 pagesCitizens United vs. FEC DBQleahscap100% (1)

- Democracy in AmericaDocument11 pagesDemocracy in AmericaJames FirthNo ratings yet

- Lecture 4: The Political System of The United States of AmericaDocument4 pagesLecture 4: The Political System of The United States of AmericaMillie JaneNo ratings yet

- Constitutional ConventionDocument16 pagesConstitutional Conventionapi-236545094No ratings yet

- The Records of The Federal Convention of 1787Document3 pagesThe Records of The Federal Convention of 1787Himanshu TaramNo ratings yet

- OVF-CPC ElectCollege PDFDocument2 pagesOVF-CPC ElectCollege PDFJust ResistanceNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Convertion-1 3Document3 pagesConstitutional Convertion-1 3api-269178075No ratings yet

- Compare U.S. Constitution With State ConstitutionsDocument5 pagesCompare U.S. Constitution With State ConstitutionsisaacsambiltonNo ratings yet

- Testimony Before The Senate Committee On Rules & AdministrationDocument65 pagesTestimony Before The Senate Committee On Rules & AdministrationThe Brennan Center for Justice100% (1)

- Congress NotesDocument14 pagesCongress NotesPaddyRamoutarNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law - Professor Ku Course Outline - Fall 2008Document27 pagesConstitutional Law - Professor Ku Course Outline - Fall 2008lieberco100% (2)

- Difference Between Democracy and RepublicDocument5 pagesDifference Between Democracy and RepublicAlvin Corpuz JrNo ratings yet

- Citizens United DBQDocument4 pagesCitizens United DBQNoahNo ratings yet

- San Diego and Tijuana Sewage Pollution Problems and Policy's SolutionsDocument6 pagesSan Diego and Tijuana Sewage Pollution Problems and Policy's SolutionsAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- Escape From PretoriaDocument199 pagesEscape From PretoriaTim Jenkin100% (2)

- Cuddy 2009Document33 pagesCuddy 2009datofezNo ratings yet

- Caunca V SalazarDocument9 pagesCaunca V SalazarCJ VillaluzNo ratings yet

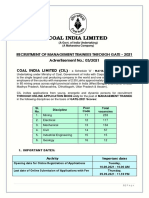

- Detailed Advertisement For Recruitment of MTs Through GATE-2021 Dt. 09.08.2021Document9 pagesDetailed Advertisement For Recruitment of MTs Through GATE-2021 Dt. 09.08.2021Priyadarshan sharmaNo ratings yet

- NLG 2014 Convention CLE Materials Vol IIIDocument1,224 pagesNLG 2014 Convention CLE Materials Vol IIILukaNo ratings yet

- Statesboro Incident ReportDocument3 pagesStatesboro Incident ReportLizHowellNo ratings yet

- Moreno vs. COMELEC (G.R. No. 168550 August 10, 2006) - Case DigestDocument1 pageMoreno vs. COMELEC (G.R. No. 168550 August 10, 2006) - Case DigestAmir Nazri Kaibing100% (1)

- Balanced Scorecard Pre Read AAIDocument16 pagesBalanced Scorecard Pre Read AAIIndresh Singh Saluja100% (1)

- Essay On Marlene From Top GirlsDocument4 pagesEssay On Marlene From Top GirlsughsamiraNo ratings yet

- 17 PDFDocument24 pages17 PDFDjelloul Ben Mohamed HdiNo ratings yet

- MYP Year 11 Assessment - Civil Rights in The USADocument7 pagesMYP Year 11 Assessment - Civil Rights in The USAStef SoNo ratings yet

- Ordinance-Ofw Help DeskDocument6 pagesOrdinance-Ofw Help DeskRandell ManjarresNo ratings yet

- COMELEC Vs Hon. Thelma CanlasDocument1 pageCOMELEC Vs Hon. Thelma CanlasClint D. LumberioNo ratings yet

- Election Commission of IndiaDocument2 pagesElection Commission of Indiaaashikapriya3037No ratings yet

- KW TaylorA History of The Vietnamese Cambridge CamDocument4 pagesKW TaylorA History of The Vietnamese Cambridge CamShaun MulhollandNo ratings yet

- NB 2023 04 11 01Document3 pagesNB 2023 04 11 01Sudarshan Sandeep SonuNo ratings yet

- New Hate and Old The Changing Face of American White Supremacy 2018Document72 pagesNew Hate and Old The Changing Face of American White Supremacy 2018epraetorianNo ratings yet

- Sigmaringen CastleDocument6 pagesSigmaringen CastleNicoleta TocituNo ratings yet

- Bonilla V BarcenaDocument1 pageBonilla V BarcenaClyde TanNo ratings yet

- Article 14 To Article 18: Right To Equality and Equal Protection of LawsDocument4 pagesArticle 14 To Article 18: Right To Equality and Equal Protection of LawsBalaNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument2 pagesUntitled DocumentManikandan VpNo ratings yet

- Sicilian Normans (Normans of The South) 1035 To 1194 - LISTDocument3 pagesSicilian Normans (Normans of The South) 1035 To 1194 - LISTrobert franz100% (1)

- Unit IV - Education and Travel Abroad: 1. Universidad Central de Madrid 2. Rizal As MasonDocument2 pagesUnit IV - Education and Travel Abroad: 1. Universidad Central de Madrid 2. Rizal As MasonAlmineNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument19 pagesIntroduction李梓誠No ratings yet

- Economic NationalismDocument2 pagesEconomic NationalismMiccah Jade CastilloNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument5 pagesResearch Proposalapi-311261133No ratings yet

- What Is To Be Done Under Real SubsumptionDocument4 pagesWhat Is To Be Done Under Real SubsumptionScroll DivingNo ratings yet

Amgovx 01 03 Rep Gov Main Lecture 2020 V5-En

Amgovx 01 03 Rep Gov Main Lecture 2020 V5-En

Uploaded by

Claudia0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views9 pagesThe document discusses the history of representative government in the US Constitution from its origins to modern times. It describes how the framers created a bicameral Congress to balance state and population interests, with the House elected by voters and Senate by state legislatures. Over time, reforms increased direct democracy, such as popular election of Senators and the president. Critics argue money's influence in elections and gerrymandering weaken the notion of the House as "the people's chamber."

Original Description:

Original Title

Amgovx 01 03 Rep Gov Main Lecture 2020 v5-En

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe document discusses the history of representative government in the US Constitution from its origins to modern times. It describes how the framers created a bicameral Congress to balance state and population interests, with the House elected by voters and Senate by state legislatures. Over time, reforms increased direct democracy, such as popular election of Senators and the president. Critics argue money's influence in elections and gerrymandering weaken the notion of the House as "the people's chamber."

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as txt, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views9 pagesAmgovx 01 03 Rep Gov Main Lecture 2020 V5-En

Amgovx 01 03 Rep Gov Main Lecture 2020 V5-En

Uploaded by

ClaudiaThe document discusses the history of representative government in the US Constitution from its origins to modern times. It describes how the framers created a bicameral Congress to balance state and population interests, with the House elected by voters and Senate by state legislatures. Over time, reforms increased direct democracy, such as popular election of Senators and the president. Critics argue money's influence in elections and gerrymandering weaken the notion of the House as "the people's chamber."

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as txt, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 9

THOMAS PATTERSON: Etched in stone in the rotunda of the capitol

are the words "Here, Sir, the People Govern."

Those words were spoken by Alexander Hamilton when

he asked what Congress represented.

To the framers of the Constitution, the Congress

was the first branch of government, the place where

the people's representatives met to decide the people's business.

Yet when the Constitution was unveiled, many leading Americans were outraged.

One of them was Richard Henry Lee of Virginia,

who had been president of the Continental Congress

during the Revolutionary War.

Richard Henry Lee said, "This constitution

has very little democracy in it."

What he was objecting to was the fact that the people were not

allowed to vote for the president or for members of the Senate.

Only the House of Representatives would be chosen by vote of the people.

When Henry Clay of Kentucky, one of the great legislators of the 19th century,

left the Senate to run for the House, he said,

"I prefer to serve in the people's chamber."

Some critics today wonder whether that label still applies to the House.

They point to House elections, which have become increasingly expensive.

It was not that long ago that these were relatively modest affairs funded

largely by donations from people living in the district.

Today, it's easily the case that a House election can cost a million dollars

or more, with much of that money coming from wealthy individuals and groups

from outside the district.

Critics also point to redistricting, the tendency of state legislatures

to pack House districts with voters from a particular party,

thereby guaranteeing the election of that party's candidate in the fall.

So who's doing the electing?

Is it the voters, or is it the state legislatures and the wealthy donors?

Those kinds of issues about self-government

have been part of the American debate since the writing of the Constitution.

[SOMBER PATRIOTIC MUSIC PLAYING]

Over the course of American history, few features of the Constitution

have been subject to more debate or more manipulation than its provisions

for representative government.

In this session, we'll look at the Constitution's provisions

for representative government, a government in which the people rule

through their representatives.

We'll start by examining the Constitution's initial provisions

for representation, and then explain how and why they were changed.

We'll then turn to voting laws and how they have affected the public's role.

Finally, we'll look at a couple of current issues:

voter ID laws and congressional redistricting.

Before I start, I have a question for you to think about.

In your view, what's the bigger threat to our democracy

in America as practiced?

Is it public officials, those who set the rules for elections,

or is it the people themselves, who can weaken democracy

by not bothering to vote, or voting even when they're not eligible to vote?

I'm not going to answer the question for you.

I want you to think about it.

When the delegates gathered in Philadelphia in 1787

to write the Constitution, they had a number

of factors that had to be taken into account.

The first was that the states had their own governments

and intended to keep them.

In addition, the states differed greatly in size and wealth.

Powerful states like Virginia and New York

were not interested in a union that failed

to recognize their prominent role.

At the same time, small states like Rhode Island and Delaware

were not interested in a union where their interests would be pushed aside.

There was also the question of the role the people would play.

Under the nation's first constitution, the Articles of Confederation,

members of Congress were chosen by the states.

Voters had no say whatsoever in this election of their representatives.

That would not work under the new Constitution.

The national government would have the power to tax the people.

They would likely rebel if denied all say

in the election of federal representatives.

These considerations were resolved by what

has become to be called the Great Compromise, the decision

to create a two-chambered Congress, the House and the Senate.

The House would have members in proportion

to each state's population, elected by the voters to two-year terms.

This arrangement satisfied the larger states:

they would have a bigger share of House seats,

and also served to satisfy those who believe

the people should have a direct vote.

In contrast, the Senate would have two members per state, chosen by the state

legislatures, for six-year terms.

This arrangement satisfied the concerns of small states:

they would have equal representation in the Senate.

It also mollified those who wanted the states

to have a say in the selection of federal officials.

State interests also figured into the method of choosing the president.

Pennsylvania's James Wilson twice proposed that the president

be popularly elected.

Twice the delegates voted him down.

A proposal to have Congress choose the president was also rejected.

That method would have weakened the president's ability

to act as a check on the Congress.

Congress would pick presidents who promised to do its bidding.

Having pretty much run out of ideas, the framers

invented what has come to be called the Electoral College.

Each state would have as many electors as it had members

of Congress, House and Senate combined.

The state legislatures would choose the electors,

and the candidate with a majority of the electoral votes would become president.

Thomas Jefferson was 3,000 miles away when the Constitution was written,

serving as US ambassador to France.

He admired many of the Constitution's features,

particularly its separation of powers.

But Jefferson worried that the people had been given too little power.

Jefferson also thought officials should be term-limited.

If not, they might come to believe that public office was theirs by right.

Other critics noted the contrast between the Constitution's provisions

and what the states were doing.

In nearly all states, governors and legislators

were chosen by direct popular vote.

Why should the national government be any different?

In defending the Constitution's provisions,

the framers argued that the history of unrestrained democracies

was the history of tyranny where the many trampled on the rights of the few.

Said James Madison, "Pure democracies have ever

been spectacles of turbulence and contention,

and have in general been as short in their lives

as they have been violent in their deaths.

The framers even had a homegrown example, Rhode Island,

to prove their point.

In that state, debtors had gained control of the legislature

and concocted a scheme for getting rid of their debt.

They passed a law authorizing the use of paper money, which

was largely worthless, to pay debts incurred by borrowing gold.

Creditors were hunted down, tied up in public places,

and people lined up to pay off their debts with the worthless paper money.

Soon the Rhode Island economy was a wreck with inflation running at 800%.

Most of its shops had shut down and creditors had fled the state.

A Boston newspaper labeled the state "Rogue Island."

The framers were so convinced of the dangers of democracy

that they refused even to call the new government a democracy.

They called it instead a republic.

The people would have a voice in the government,

but it would be filtered through representative institutions,

only one of which, the House, would be subject to direct election.

The Constitution, said Madison, was "a republican remedy

for the ills of uncontrolled democracy."

Now whether intended or not, the Constitution's provisions

for representative government virtually guaranteed that the federal government

would initially be controlled by wealthy or otherwise prominent Americans.

Through the first six presidents, very few small farmers, craftsmen,

or merchants were elected to Congress or held high-ranking executive positions,

even though they made up the vast majority of the population.

That situation changed with the election of the seventh president, Andrew

Jackson.

Raised in poverty by a widowed mother in the backwoods of Carolina,

Jackson won national fame as commanding general at the Battle of New Orleans,

where US forces defeated the British in the War of 1812.

Upon assuming the presidency, Jackson appointed ordinary citizens

to executive office and pressured states to eliminate property ownership

as a requirement for voting.

He tried but failed to get rid of the Electoral College,

but then persuaded the states to tie their electoral votes

to the popular vote.

Jackson's system is the one we have today.

The winner of a state's popular vote receives its electoral votes,

giving the voters a decisive say in the choice of the president.

Seven decades later, the Constitution was

amended to provide for the popular election of senators.

The Senate had become a corrupt institution.

Powerful corporations had bribed and bullied

state legislatures to choose senators who would protect their interests.

The ensuing scandals helped fuel the progressive movement,

which was the leading force behind the amendment.

The progressives also challenged the party machines

that had taken over control of candidate nominations.

They succeeded in getting states to adopt primary elections where

the voters, rather than the party organizations, chose the nominees.

As you might have noted, these changes basically

undid the work of the framers.

The presidency, House, and Senate were now all subject

to vote of the people who had two chances to be heard:

once in the primary and once in the general election.

This was a remarkable change.

At the beginning of the republic, the people

had a relatively small voice in their governing.

Today, as has been true ever since the progressive era,

the United States has more elections for national office

than any other democracy.

Lots of elections doesn't mean that Americans vote regularly.

In fact, the United States has nearly the lowest voting

rate among Western democracies.

As this chart indicates, the voting rate in US presidential elections

is roughly 60%, below that of other leading democracies.

In some countries, Italy being an example, the rate exceeds 80%.

To understand why the United States lags behind,

we need to go back to the writing of the Constitution.

As originally written, the Constitution did not provide for the right to vote.

Some Americans were held in slavery and were denied even citizenship.

For their part, women were thought not to have

a rightful place in public affairs.

Not until ratification of the 19th amendment in 1920

did women get the right to vote.

The original Constitution had a single clause on voting.

It gave the states authority to determine voting eligibility

in federal elections, saying only that a state's restrictions on voting

could not be greater than those placed on voting for members of the largest

chamber of the state's legislature.

That clause seemed harmless at the time, but it has turn out

to be a source of mischief.

It has been used at times to deny some people the right to vote.

In the early history of the United States,

most states denied the vote to males without property, a policy

that Ben Franklin thought worthy of ridicule.

"Today," wrote Franklin, "a man owns a jackass with $50 and he is entitled

to vote, but before the next election the jackass dies and the man cannot

vote.

Who is the voter, the man or the jackass?"

By the 1830s, urged on by Andrew Jackson,

nearly all states had dropped the property requirement.

The ugliest chapter in America's voting history began in the South

after the Civil War and lasted nearly a century.

The 15th Amendment, which was ratified soon after the war,

prohibits states from denying the vote on the basis of race or color.

When Northern troops left the South a decade after the Civil War ended,

the South's white majority governments concocted every trick

imaginable to keep Blacks from voting.

Louisiana wiped clean its registration rolls

and required its residents to re-register.

The state made it so hard for Blacks to re-register that less than one in ten

were able to do so.

Throughout the South, literacy tests and poll taxes were adopted.

In order to register to vote, citizens had to pass a literacy test

and pay a tax.

To ensure that white voters were not disenfranchised by these requirements,

a grandfather clause was placed in the law.

Anyone whose father or grandfather had been eligible to vote

was exempt from the requirements.

Obviously, no former slave or child of a slave qualified for that exemption.

The Supreme Court waited until 1915 before declaring

the scheme unconstitutional.

Whites-only primaries were also devised.

The Democratic party was in control throughout the South.

Every governor, every state legislature, and nearly every member of Congress

was a Democrat.

As a result, the key election throughout the South was the Democratic primary.

Whoever won that primary was virtually assured

of winning the general election.

Blacks were prohibited from voting in primaries.

The Supreme Court waited until 1944 to strike down that practice.

The court refused, however, to strike down literacy tests and poll taxes,

and they effectively kept Blacks away from the polls.

The literacy tests were so difficult that those administering them

had to look up the answers and were given discretion

in determining whether an applicant had passed.

Whites routinely did.

Blacks who scored as high or higher were frequently told they had failed.

In some places, it took courage even to apply for the vote.

The local newspaper would publish the names

of those who had applied so that white employers would

know which Blacks not to hire.

In the entire state of Mississippi, fewer than 5% of eligible Blacks

were registered to vote even as late as the 1950s.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 brought an end to these tricks.

The legislation empowered federal officials

to register voters in states and counties

with histories of racial discrimination.

In less than two years, Black registration in Mississippi

had jumped tenfold.

In Alabama it climbed from less than 20% to over 50%.

The Voting Rights Act produced a regional split in Congress

not seen since.

The Senate vote was 77 to 19, with all 19 no votes cast by Southern senators.

Every senator from outside the South, Republican or Democrat,

voted for the bill.

The House vote also divided sharply along North/South lines.

Once the law was in place, Southern states

challenged it in court, arguing it violated the Constitutional

clause that gives states the power to determine voter eligibility.

The Supreme Court rejected the challenge,

holding that another clause of the Constitution, the 14th Amendment's

equal protection clause took precedent.

The Voting Rights Act also temporarily banned

the use of literacy tests, which were later

banned completely by the Supreme Court.

Ratification of the 24th Amendment brought the poll tax to an end.

Since passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965,

Black voting has edged steadily upward such that today the rate is not greatly

different from that of white voters.

Now, if the politics of voting until the 1960s

were largely the politics of race, it has since

been a case of party politics, as the Republican and Democratic parties

have jockeyed for voting regulations that might help them win elections.

A major target has been voter registration,

which is handled differently in the United States than in Europe.

In European democracies, government assumes responsibility

for registering voters.

If a citizen moves to a new address, for example,

the postal service will notify election officials

to change the individual's registration.

The result is that over 90% of eligible European voters are registered.

By comparison, only about 75% of vote eligible US citizens are registered.

The difference stems from the fact that registration in the United States

is the individual's responsibility.

Eligible citizens must personally take the time to register.

Where government comes into this picture is that it

can make that process easier or harder.

If it lowers the barriers to registration,

you expand the electorate.

If it raises them, you shrink it.

So which political party do you think would benefit

from making registration easier?

The Democrats, the Republicans, both about equally.

It's the Democrats.

Voting in the United States tilts heavily toward those of higher income.

As you can see from this chart, the voting rate

among those in the top fifth of income is far higher

than those in the bottom fifth.

Income correlates with party preference.

Upper income voters tend to cast their votes for Republican candidates,

while those at the bottom of the income ladder

tend to vote Democratic as a result of the party's leadership

on policies that benefit those of lower income such as welfare

services and the minimum wage.

The arithmetic of voting has not been lost on the parties.

The Democratic party has pressed hard to make voter registration easier.

Its most notable success was the 1993 Motor Voter Act.

The Act requires states to offer voter registrations

when they apply for a driver's license or public assistance.

The Motor Voter bill first passed Congress in 1991,

but a Republican, George H.W. Bush, was in the White House.

He vetoed it.

The Democratic-controlled Congress passed it again in 1993.

This time a fellow Democrat, Bill Clinton, was in office,

and he signed the bill into law.

In the Senate, only three Republicans backed the bill,

while all 59 Democrats did so.

Voting in the House also divided sharply along party lines

with Republicans overwhelmingly opposed and Democrats overwhelmingly in favor.

Studies of the Motor Voter Act indicate it accounts for about a third

of new registrants.

To the surprise of both parties, however,

the number of new Democratic registrants resulting from the law

has only slightly outpaced the number of new Republican registrants.

Now, the Republican Party has worked the other side of the fence,

seeking to hold down voter registration.

The centerpiece of this effort in recent years has been voter ID laws.

In strictest form, an applicant must have a government-issued photo

ID such as a driver's license or passport in order to register.

In other states with voter ID laws, other forms of ID

are acceptable as long as they suggest the applicant is a citizen.

Now, the express purpose of these laws is

to prevent voter fraud, to keep people who are non-citizens from voting.

The real intent is different.

They are designed to make it difficult for those without a formal ID

to register.

About 10% of vote-eligible citizens do not

have a government-issued identification card

and they are disproportionately young, poor, and minorities.

All of these groups tend to vote Democratic.

The first voter ID laws were enacted by the Republican-controlled legislatures

of Georgia and Indiana.

Of the more than 30 states that have followed their lead, all but two,

Rhode Island and Hawaii, had a Republican-controlled legislature.

In a 6 to 3 ruling, the Supreme Court upheld Indiana's law.

All six judges in the majority were Republican appointees,

and though they acknowledged Indiana's law had a partisan purpose,

they said other purposes, including the public's faith in the integrity

of the ballot, justified the ID law.

The court said that the law should not be disregarded simply

because partisan interests may have provided

one motivation for the votes of individual legislators.

Research indicates that voter fraud is extremely rare.

It appears that almost no one is willing to risk being arrested and fined

for illegal voting.

Sometimes it's even tough to get legal voters to show up at the polls.

Research indicates that the suppressive effect of voter ID laws

has been smaller than many opponents of the laws had predicted.

The research has shown, however, that those

who are disenfranchised by the requirement

are disproportionately the poor and minorities.

In 2017, the Supreme Court invalidated North Carolina's voter ID law.

Enacted by the state's Republican legislature

after a surge in registration by the state's Black residents,

the law required registrants henceforth to have a government-issued photo ID.

The Supreme Court held that the law had a discriminatory intent,

concluding that its purpose was to suppress the Black vote.

It's too early to tell whether the Supreme Court's ruling in the North

Carolina case might lead it to restrict voter ID laws more generally.

Finally, let's briefly examine partisan gerrymandering,

a tactic used by both parties.

After the population census every 10th year, House seats

are reapportioned to states on the basis of their populations.

The more populous the state, the more House seats it gets.

California, for example, has 53 House seats, while South Dakota has only one.

Under the Constitution, state legislatures

have the authority to set the boundaries of House districts.

The majority party in these legislatures typically

divides up the state in a way that will help its party's candidates,

a process called gerrymandering.

The safe way to do this is to pack targeted districts

with enough of the party's voters to assure victory in the election.

The other party is also likely to receive safe seats.

This happens because if some districts are

stacked to the top with the opposing party's voters,

there will be fewer such voters in other districts.

More than 85% of House seats today are uncompetitive, virtually

certain to be won by the candidate of the stronger party.

There are several reasons for this, including the fact that some states are

so heavily Democratic or Republican that it's

hard to design competitive districts.

But gerrymandering is among the reasons that many House races are effectively

decided before a single vote is cast.

Now, gerrymandering worked to Democrats' advantage

until the early 1990s, at which time an increasing number of state legislatures

came under Republican control.

Republican legislatures did such a precise job of gerrymandering

after the 2010 census that in the 2012 election,

they won a comfortable majority of House seats

even though Republican candidates received fewer votes nationally

than did their Democratic opponents.

As gerrymandering has become ever more precise as a result of computers,

it has increasingly come under legal challenges.

In 2019, the Supreme Court refused to rein in the practice,

holding that courts do not have the authority to limit gerrymandering.

The case was decided by a 5 to 4 vote with all five

Republican-appointed justices voting against placing limits

on gerrymandering, and all four Democratic-appointed justices voting

to restrict it.

The five-member Republican majority said that unrestrained gerrymandering may

be incompatible with democratic principles,

but that judges lack a precise standard for determining

when partisan gerrymandering has gone too far.

In their dissenting opinion, the four Democratic-appointed justices

said, "For the first time ever, this court

refuses to remedy a constitutional violation that

deprives citizens of the most fundamental

of their constitutional rights."

Now, a few states, Iowa, California, and Montana among them,

have recently decided to place redistricting

in the hands of a nonpartisan commission.

It's unlikely that a great many states will follow their example given

the fact that most state legislatures have signaled their intent

to retain control of redistricting.

Before wrapping up, let me say a few words about the electoral college.

Democratic elections are generally based on the principle

of one person, one vote.

The winner is the side that gets the most popular votes.

But in US presidential elections, the winner

is the candidate who gets a majority of the electoral votes.

Now, in most presidential elections, the popular vote winner also

wins a majority of the electoral votes, but not always.

That's happened four times in American history, two of them recent.

In 2000, Al Gore received half a million more votes nationally

than did George W. Bush, yet lost the election.

It happened again in 2016 when Hillary Clinton,

though receiving nearly 3 million more votes nationally than Donald Trump,

was defeated.

If the US Constitution were being written today,

the idea of having the president selected through the electoral college

would not be taken seriously.

The principle of one person, one vote is now an established democratic practice,

yet the electoral college survives because of the difficulty

of amending the US Constitution.

It requires a 2/3 vote in the House, plus a 2/3 vote in the Senate,

plus ratification by 3/4 of the state legislatures.

That's an imposing barrier to change.

There have been hundreds of unsuccessful attempts in Congress

to abolish the electoral college.

The reason is that some states benefit from it.

Because each state, regardless of size, gets two electoral votes

as a result of having two US senators, the smallest states

gain leverage from the electoral college.

The dozen smallest US states have 8% of the electoral vote

even though they constitute less than 4% of the US population.

They have twice the voting power under the electoral college

than they would under a popular vote system.

These states alone have nearly enough votes in the Senate

to block an amendment.

OK, let's wrap up what we've covered in this session.

We've focused on representative government

as provided by the Constitution.

It was noted that the voters originally had a say only

in the election of House members, a reflection of the framers'

determination to prevent a passionate majority from taking

control and running roughshod over the minority.

With time, due in part to the Jacksonian and progressive movements,

popular voting came to include Senate and presidential elections.

The adoption of primary elections, an American invention,

also served to shift power to the voters.

Today, Americans vote more often for more offices than voters elsewhere.

On the other hand, the public's influence

is diminished by partisan gerrymandering and by the efforts of officials

to manipulate the size of the electorate through control

of the voter registration process.

Although these recent efforts pale alongside those used in the past

to keep Black Americans from voting, they

are a source of court challenges and intense partisan debate.

In other words, representative government in America

is still a work in progress.

You might also like

- How Democratic Is The American Constitution by Robert A. DahlDocument7 pagesHow Democratic Is The American Constitution by Robert A. Dahlbrucewphillips0% (1)

- For 1943 ConstitutionDocument11 pagesFor 1943 Constitutionernesto pitogo75% (4)

- The Paris Peace Conference, 1919 - Peace Without Victory - (Studies in Military and Strategic History)Document212 pagesThe Paris Peace Conference, 1919 - Peace Without Victory - (Studies in Military and Strategic History)Cora Brumaru0% (1)

- Lesson 1 National Legislature OverviewDocument19 pagesLesson 1 National Legislature OverviewEsther EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Congress Is A Dysfunctional InstitutionDocument7 pagesCongress Is A Dysfunctional InstitutionS VanceNo ratings yet

- 17th AmendmentDocument1 page17th AmendmentBarry BenchNo ratings yet

- Congress Is A Dysfunctional InstitutionDocument7 pagesCongress Is A Dysfunctional InstitutionS VanceNo ratings yet

- Origins of The Electoral College: 45 Comments U.S. Historyphilosophy and Methodologypolitical Theory Randall G. HolcombeDocument9 pagesOrigins of The Electoral College: 45 Comments U.S. Historyphilosophy and Methodologypolitical Theory Randall G. Holcombedbush1034No ratings yet

- The Seventeenth Amendment:: The Folly of The Direct Election of SenatorsDocument22 pagesThe Seventeenth Amendment:: The Folly of The Direct Election of SenatorslarpNo ratings yet

- Greg Abbott - Restoring The Rule of LawDocument92 pagesGreg Abbott - Restoring The Rule of LawBob Price100% (3)

- Restoring The Rule of Law With States Leading The WayDocument92 pagesRestoring The Rule of Law With States Leading The Wayadan_infowars100% (1)

- Examen Eeuu:: 1. "A City Upon A Hill" and Puritan ThinkDocument27 pagesExamen Eeuu:: 1. "A City Upon A Hill" and Puritan ThinkAlexia Vázquez OrgazNo ratings yet

- What Is The Legislative Branch OverviewDocument3 pagesWhat Is The Legislative Branch Overviewapi-241101238No ratings yet

- Washington Times Advert: Obama ID FraudDocument1 pageWashington Times Advert: Obama ID FraudObamaRelease YourRecordsNo ratings yet

- American Gov Hon Research PaperDocument14 pagesAmerican Gov Hon Research Paperapi-596908445No ratings yet

- The Constitution of the United States: Updated for Better Government in the Twenty-First Century Second EditionFrom EverandThe Constitution of the United States: Updated for Better Government in the Twenty-First Century Second EditionNo ratings yet

- Malone POL 296N Lecture 1Document20 pagesMalone POL 296N Lecture 1cmalone410No ratings yet

- Democracy Vs RepublicDocument4 pagesDemocracy Vs RepublicTony SanchezNo ratings yet

- Electoral College Assignment (AP)Document6 pagesElectoral College Assignment (AP)Philip ArgauerNo ratings yet

- Exposé AnglaisDocument5 pagesExposé Anglaisah.dutilleulNo ratings yet

- CongressDocument16 pagesCongressapi-164891616No ratings yet

- The Political System in The US: Historical DocumentsDocument3 pagesThe Political System in The US: Historical DocumentsRiaz khanNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Foundation Lecture Notes - Part IIIDocument9 pagesConstitutional Foundation Lecture Notes - Part IIIbtharwoodNo ratings yet

- What is a Democracy? US Government Textbook | Children's Government BooksFrom EverandWhat is a Democracy? US Government Textbook | Children's Government BooksNo ratings yet

- Opinion - The Electoral College Was Not A Pro-Slavery Ploy - The New York TimesDocument2 pagesOpinion - The Electoral College Was Not A Pro-Slavery Ploy - The New York TimesASHLEE SALTERNo ratings yet

- Thesis ConstitutionDocument5 pagesThesis Constitutiondiasponibar1981100% (2)

- Political System USADocument16 pagesPolitical System USAHanna100% (1)

- Tyrants in Black Robes: How the Federal Courts Destroyed Our RepublicFrom EverandTyrants in Black Robes: How the Federal Courts Destroyed Our RepublicNo ratings yet

- Government WebQuestDocument20 pagesGovernment WebQuestazeneth100% (1)

- Checks and Balances: A Look at the Powers of GovernmentFrom EverandChecks and Balances: A Look at the Powers of GovernmentRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- 7Document6 pages7pdotvafqeatngzhonpNo ratings yet

- Clements Paper For Senate Hearing - 7-24-2012Document17 pagesClements Paper For Senate Hearing - 7-24-2012mary engNo ratings yet

- Martin - Judges, Lawyers and Other Destroyers (Corrupt Judicial System) (1992)Document38 pagesMartin - Judges, Lawyers and Other Destroyers (Corrupt Judicial System) (1992)scooter123100% (2)

- Tea Party and SecessionDocument3 pagesTea Party and SecessionMichael TheodoreNo ratings yet

- What Is The Doctrine of Incorporation? Why Is It Important?Document7 pagesWhat Is The Doctrine of Incorporation? Why Is It Important?Eka MaisuradzeNo ratings yet

- Adminstrative System of UsaDocument11 pagesAdminstrative System of Usadekha dekhiNo ratings yet

- Citizens United v. FEC DBQDocument4 pagesCitizens United v. FEC DBQMargotNo ratings yet

- How Democratic Is The US Constitution?Document5 pagesHow Democratic Is The US Constitution?paulaNo ratings yet

- Citizens United vs. FEC DBQDocument5 pagesCitizens United vs. FEC DBQleahscap100% (1)

- Democracy in AmericaDocument11 pagesDemocracy in AmericaJames FirthNo ratings yet

- Lecture 4: The Political System of The United States of AmericaDocument4 pagesLecture 4: The Political System of The United States of AmericaMillie JaneNo ratings yet

- Constitutional ConventionDocument16 pagesConstitutional Conventionapi-236545094No ratings yet

- The Records of The Federal Convention of 1787Document3 pagesThe Records of The Federal Convention of 1787Himanshu TaramNo ratings yet

- OVF-CPC ElectCollege PDFDocument2 pagesOVF-CPC ElectCollege PDFJust ResistanceNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Convertion-1 3Document3 pagesConstitutional Convertion-1 3api-269178075No ratings yet

- Compare U.S. Constitution With State ConstitutionsDocument5 pagesCompare U.S. Constitution With State ConstitutionsisaacsambiltonNo ratings yet

- Testimony Before The Senate Committee On Rules & AdministrationDocument65 pagesTestimony Before The Senate Committee On Rules & AdministrationThe Brennan Center for Justice100% (1)

- Congress NotesDocument14 pagesCongress NotesPaddyRamoutarNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law - Professor Ku Course Outline - Fall 2008Document27 pagesConstitutional Law - Professor Ku Course Outline - Fall 2008lieberco100% (2)

- Difference Between Democracy and RepublicDocument5 pagesDifference Between Democracy and RepublicAlvin Corpuz JrNo ratings yet

- Citizens United DBQDocument4 pagesCitizens United DBQNoahNo ratings yet

- San Diego and Tijuana Sewage Pollution Problems and Policy's SolutionsDocument6 pagesSan Diego and Tijuana Sewage Pollution Problems and Policy's SolutionsAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- Escape From PretoriaDocument199 pagesEscape From PretoriaTim Jenkin100% (2)

- Cuddy 2009Document33 pagesCuddy 2009datofezNo ratings yet

- Caunca V SalazarDocument9 pagesCaunca V SalazarCJ VillaluzNo ratings yet

- Detailed Advertisement For Recruitment of MTs Through GATE-2021 Dt. 09.08.2021Document9 pagesDetailed Advertisement For Recruitment of MTs Through GATE-2021 Dt. 09.08.2021Priyadarshan sharmaNo ratings yet

- NLG 2014 Convention CLE Materials Vol IIIDocument1,224 pagesNLG 2014 Convention CLE Materials Vol IIILukaNo ratings yet

- Statesboro Incident ReportDocument3 pagesStatesboro Incident ReportLizHowellNo ratings yet

- Moreno vs. COMELEC (G.R. No. 168550 August 10, 2006) - Case DigestDocument1 pageMoreno vs. COMELEC (G.R. No. 168550 August 10, 2006) - Case DigestAmir Nazri Kaibing100% (1)

- Balanced Scorecard Pre Read AAIDocument16 pagesBalanced Scorecard Pre Read AAIIndresh Singh Saluja100% (1)

- Essay On Marlene From Top GirlsDocument4 pagesEssay On Marlene From Top GirlsughsamiraNo ratings yet

- 17 PDFDocument24 pages17 PDFDjelloul Ben Mohamed HdiNo ratings yet

- MYP Year 11 Assessment - Civil Rights in The USADocument7 pagesMYP Year 11 Assessment - Civil Rights in The USAStef SoNo ratings yet

- Ordinance-Ofw Help DeskDocument6 pagesOrdinance-Ofw Help DeskRandell ManjarresNo ratings yet

- COMELEC Vs Hon. Thelma CanlasDocument1 pageCOMELEC Vs Hon. Thelma CanlasClint D. LumberioNo ratings yet

- Election Commission of IndiaDocument2 pagesElection Commission of Indiaaashikapriya3037No ratings yet

- KW TaylorA History of The Vietnamese Cambridge CamDocument4 pagesKW TaylorA History of The Vietnamese Cambridge CamShaun MulhollandNo ratings yet

- NB 2023 04 11 01Document3 pagesNB 2023 04 11 01Sudarshan Sandeep SonuNo ratings yet

- New Hate and Old The Changing Face of American White Supremacy 2018Document72 pagesNew Hate and Old The Changing Face of American White Supremacy 2018epraetorianNo ratings yet

- Sigmaringen CastleDocument6 pagesSigmaringen CastleNicoleta TocituNo ratings yet

- Bonilla V BarcenaDocument1 pageBonilla V BarcenaClyde TanNo ratings yet

- Article 14 To Article 18: Right To Equality and Equal Protection of LawsDocument4 pagesArticle 14 To Article 18: Right To Equality and Equal Protection of LawsBalaNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument2 pagesUntitled DocumentManikandan VpNo ratings yet

- Sicilian Normans (Normans of The South) 1035 To 1194 - LISTDocument3 pagesSicilian Normans (Normans of The South) 1035 To 1194 - LISTrobert franz100% (1)

- Unit IV - Education and Travel Abroad: 1. Universidad Central de Madrid 2. Rizal As MasonDocument2 pagesUnit IV - Education and Travel Abroad: 1. Universidad Central de Madrid 2. Rizal As MasonAlmineNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument19 pagesIntroduction李梓誠No ratings yet

- Economic NationalismDocument2 pagesEconomic NationalismMiccah Jade CastilloNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument5 pagesResearch Proposalapi-311261133No ratings yet

- What Is To Be Done Under Real SubsumptionDocument4 pagesWhat Is To Be Done Under Real SubsumptionScroll DivingNo ratings yet