Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Unified Model For Stroke Recovery And.2

A Unified Model For Stroke Recovery And.2

Uploaded by

Papu FloresOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Unified Model For Stroke Recovery And.2

A Unified Model For Stroke Recovery And.2

Uploaded by

Papu FloresCopyright:

Available Formats

ANALYSIS & PERSPECTIVE

A Unified Model for Stroke Recovery and Rehabilitation

Why Now?

Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/ajpmr by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1A

Preeti Raghavan, MD

WnYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC4/OAVpDDa8KKGKV0Ymy+78= on 11/03/2023

Abstract: The current model of stroke care delivery in the United therapy sessions per week, intensity of the therapy sessions, and

States and in many parts of the world is fragmented, resulting in lack type of interventions delivered.4 The American Heart Associa-

of continuity of care, inability to track recovery meaningfully across tion’s guidelines recommend consultation by a rehabilitation spe-

the continuum, and lack of access to the frequency, intensity, and dura- cialist leading a multidisciplinary team as soon as possible, ideally

tion of high-quality rehabilitation necessary to optimally harness recov- within 24 hours, for a patient admitted with a diagnosis of stroke.5

ery processes. The process of recovery itself has been overshadowed by Unfortunately, the focus of this consultation is typically on transi-

a focus on length of stay and the movement of patients across levels of tion of care and selection of the discharge destination,6–8 rather

care. Here, we describe the rationale behind the recent efforts at the than on providing multidisciplinary rehabilitation interventions

Johns Hopkins Sheikh Khalifa Stroke Institute to define and coordinate focused on facilitating recovery to reduce long-term disability.

an intensive, strategic effort to develop effective stroke systems of care This is particularly problematic because mortality at 1 yr after

across the continuum through the development of a unified Sheikh stroke is strongly predicted by ambulatory status at discharge

Khalifa Stroke Institute model of recovery and rehabilitation. from the acute hospital stroke service—patients who needed as-

sistance to walk and were nonambulatory at discharge were

Key Words: Stroke, Rehabilitation, Therapy, Disability, Value, Cost more likely to die at 1 yr than those who were ambulatory at dis-

(Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2023;102:S3–S9) charge.9 Hence, enhancing mobility should be a priority in the

days immediately after stroke.

It is well known that poststroke immobility can lead to in-

creased risk of falls, fractures, pneumonia, pressure ulcers, and

here are more than 80 million stroke survivors worldwide1;

T this staggering number is only matched by the equally

pulmonary embolism and increases healthcare costs substan-

tially, whereas early, high-frequency rehabilitation can reduce

enormous stroke-related medical costs that are projected to ex- these complications and reduce healthcare costs.10–13 In addi-

ceed US $183 billion annually by 2030.2 Although the overall tion, immobility limits cardiovascular exercise and increases

burden of stroke, as quantified by age-standardized disability- the risk for recurrent stroke or cardiovascular illness, and recent

adjusted life years, has decreased in the last three decades, the guidelines emphasize the importance of facilitating physical

absolute number of disability-adjusted life years due to stroke activity poststroke, which in turn has been shown to reduce re-

has increased because of population growth and aging result- admissions, mortality, and healthcare costs.14–18 Thus, it is

ing in a higher prevalence of chronic stroke.1 The trends are now imperative to implement early recovery-focused rehabili-

similar in the Middle East and North Africa.3 In most regions tation in the real world to best serve our patients, mitigate dis-

metabolic risks (high systolic blood pressure, high body-mass ability, and reduce unnecessary long-term healthcare costs.19

index, high fasting plasma glucose, high total cholesterol, and Hence, we—the leaders, faculty, and staff at the Johns Hopkins

low glomerular filtration rate), and behavioral factors (smoking, Sheikh Khalifa Stroke Institute (SKSI)—collaborated to de-

poor diet, and low physical activity) account for the largest pro- velop the unified SKSI model of recovery and rehabilitation,

portion of stroke disability-adjusted life years. Rehabilitation is which we describe here.

necessary both for reducing the burden of disability and for

modification of risk factors to reduce the enormous societal

and economic burden of stroke. RECOVERY AFTER STROKE: WHAT IS NEEDED?

Rehabilitation services after stroke in the United States are Recovery after stroke occurs across all domains (e.g., mo-

highly heterogeneous and vary by the type of care setting (acute tor, sensory, cognition, perception, language). One of the most

hospital service, acute inpatient rehabilitation, subacute facility, studied areas of recovery is in the motor domain. Motor recov-

home care services, or outpatient rehabilitation), duration of re- ery is defined in terms of recovery of motor performance rather

habilitation (length of stay in the specific setting), frequency of than recovery of neural integrity, because any kind of recovery

of performance after neural injury will require both neural repair

and neural compensation.20 Recovery of motor performance or

From the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation and Neurology, Johns skill is defined as the reappearance of elemental motor patterns

Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland.

All correspondence should be addressed to: Preeti Raghavan, MD, 600 N Wolfe St, present before central nervous system injury.21 In contrast, mo-

Phipps Building, Suite 174, Baltimore, MD 21287. tor compensation is defined as the appearance of new motor

This work is funded by the Johns Hopkins Sheikh Khalifa Stroke Institute.

Financial disclosure statements have been obtained, and no conflicts of interest have

patterns resulting from the adaptation of remaining motor ele-

been reported by the authors or by any individuals in control of the content of ments or substitution, meaning that functions are taken over,

this article. replaced, or substituted by different body segments. Reha-

Copyright © 2023 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

ISSN: 0894-9115 bilitation providers must carefully balance the need to restore

DOI: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000002141 function by teaching compensatory strategies versus striving

American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation • Volume 102, Number 2 (Suppl), February 2023 www.ajpmr.com S3

Copyright © 2023 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Raghavan Volume 102, Number 2 (Suppl), February 2023

for improvements in movement quality by reducing motor im- and there were statistically significant gains in function.26 The

pairment. The degree of poststroke motor impairment has been Queen Square Upper Limb Neurorehabilitation program provided

shown to be a key factor in the extent of recovery that is possi- high-dose, high-intensity upper limb neurorehabilitation for

ble.22,23 However, biologic processes of neural repair interact 5 days a week over 3 wks (90 hrs total) for patients with

with behavioral activity to influence recovery (Fig. 1),24 and chronic stroke and reported significant changes in arm motor

Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/ajpmr by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1A

these processes are similar to those that occur in skill learning impairment, measured using the modified Fugl-Meyer Scale,

in individuals without neurologic injury. and arm function, measured using the Action Research Arm

A vast amount of evidence accumulated in the last three Test and the Chedoke Arm and Hand Activity Inventory 13.

decades has shown that recovery after stroke is dependent on There were clinically and statistically significant gains at the

WnYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC4/OAVpDDa8KKGKV0Ymy+78= on 11/03/2023

the timing, frequency, intensity, and content of rehabilitation end of the 3-wk intervention that persisted for 6 mos after the

interventions delivered after stroke.25 For example, high-intensity program ended.27 In a separate study, hand dexterity and finger

and long-dose therapy when given progressively, consistently, independence also increased in patients with chronic stroke that

and repetitively following motor learning principles substan- received high-intensity training, and the reduction in impair-

tially reduces motor impairment and increases function even in ment was maintained for 6 mos after training.28 The mecha-

patients with moderate-to-severe motor impairment in the chronic nisms of improvement in dexterity in patients with chronic

stage poststroke.26–29 In an upper limb study of long-dose ther- stroke have been shown to involve sensorimotor integration

apy, Daly et al. asked whether individuals with moderate/ and changes in muscle coordination, which may be noted af-

severe impairment in the chronic phase after stroke respond ter a single session of training with the appropriate type of

to high-dose therapy (300 hrs) or experience a midtreatment practice.30 Similarly, in a lower limb study, an array of interven-

plateau and whether gains in motor impairment and function tions targeted treatment-resistant impairments underlying persis-

were retained after treatment. Pretreatment to midtreatment tent mobility dysfunction, such as weakness, balance deficit, limb

and midtreatment to posttreatment gains in motor impairment, movement dyscoordination, and gait dyscoordination over 6

measured using the Fugl-Meyer scale, were statistically and mos, and showed clinically or statistically significant improve-

clinically significant, indicating no plateau at 150 hrs and a ments in an array of measures of impairment, functional mo-

continued benefit from the second half of treatment. From base- bility, and personal milestone achievements.29 These studies

line to 3-mo follow-up, the gains in motor impairment were suggest that even chronic stroke patients can benefit from

twice the clinically significant benchmark, and gains in func- high-intensity, high-dose therapy, with persistent reduction

tion, measured using the Arm Motor Ability Test, were greater in disability.

than the clinically significant benchmark. From posttreatment More recently, the value of an additional 20 hrs of therapy

to 3-mo follow-up, gains in motor impairment were maintained, given early on (within 3 mos) during a presumed critical period

FIGURE 1. Biologic principles of neural repair can inform rehabilitation therapeutics. From Carmichael24 (2016), with permission.

S4 www.ajpmr.com © 2023 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2023 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Volume 102, Number 2 (Suppl), February 2023 Unified Model for Stroke Recovery

after stroke was tested. The study showed that patients who re- characteristics in turn predict the recovery time for indepen-

ceived the additional therapy in the acute (within 1 mo) and dence in poststroke abilities and need to be optimized early

subacute (between 2 and 3 mos) period poststroke had signifi- poststroke to reduce the socioeconomic impact caused by

cantly reduced arm motor disability measured using the Action poststroke disability.32,33

Research Arm Test at 1 yr compared with those who received A critical first step in delivering on our mission was to

Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/ajpmr by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1A

the same amount of therapy in the chronic stage (after 6 mos) bridge the continuum of care for patients with stroke to create

or did not receive additional therapy.31 Taken together, these a unified transdisciplinary focus on the patient’s recovery and

studies suggest that impairment-focused therapy can improve rehabilitation. Specifically, we needed to integrate care deliv-

the extent of recovery at any stage, but the dose of therapy re- ery across the system (i.e., the acute hospital stroke service,

WnYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC4/OAVpDDa8KKGKV0Ymy+78= on 11/03/2023

quired may be far greater in the chronic stage relative to the the acute inpatient rehabilitation service, and the outpatient

acute and subacute stages. Furthermore, retraining cardiovas- stroke service), and build an outcomes database to be able to

cular capacity within 3 mos poststroke may also have a non- consistently and reliably tailor clinical care and measure the

specific effect on mobility, activities of daily living, and cog- changes in outcomes across the continuum. The outcome mea-

nition as measured by patient-reported outcomes.15,17 Thus, surements also enable the development of algorithms to match

optimizing high-dose skill training as well as cardiovascular the timing, dose, and content of therapy/rehabilitation sessions

capacity during the period of biologic recovery may be particu- to each patient more precisely, given their level of impairment

larly conducive to motor recovery after stroke (Fig. 2) and im- and cardiovascular capacity. Our next step will be to test the ef-

portant to mitigate long-term disability and the associated fectiveness of the model and disseminate our learnings both

healthcare costs. A key question is—how can we consistently within Johns Hopkins and in the United Arab Emirates, as well

deliver high-dose stroke rehabilitation in the real world? as nationally and internationally (Fig. 3).

A UNIFIED MODEL OF STROKE CARE FACTORS TO CONSIDER IN

Postacute stroke care is delivered in silos created by mul- RECOVERY-CENTERED DELIVERY OF

tiple healthcare settings and specialties, making it difficult to REHABILITATION SERVICES

translate the available scientific evidence into optimal care de- Stroke recovery is complex. The delivery of rehabilitation

livery. The mission of the SKSI is to “transform the care of pa- is impacted by impairments across multiple domains, such

tients with stroke to facilitate optimal recovery and ultimately as motor planning, weakness, spasticity, sensory perception,

prevent or reduce disability.” To deliver on this core mission, sensory-motor integration, motor cognition, and language, etc.,

we needed to define and coordinate an intensive, strategic ef- which in turn impact function and participation as per the World

fort to treat stroke, and promote recovery to the greatest ex- Health Organization’s International Classification of Function-

tent possible, and as early as possible to mitigate long-term ing, Disability, and Health model.34 There is a many-to-one re-

disability. Furthermore, the early poststroke period is the op- lationship between impairment and function, and function and

timal time to instill a positive attitude and develop life habits participation, which makes impairment-focused treatment dif-

that are necessary for both recovery and secondary preven- ficult to deliver. For example, difficulty performing a func-

tion. Physical ability, neuropsychological, and life habit tional activity such as drinking from a cup may be caused by more

FIGURE 2. Poststroke recovery occurs at the intersection of biologic repair processes, skill retraining through task-specific therapies, and rebuilding

cardiovascular capacity.

© 2023 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. www.ajpmr.com S5

Copyright © 2023 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Raghavan Volume 102, Number 2 (Suppl), February 2023

Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/ajpmr by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1A

WnYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC4/OAVpDDa8KKGKV0Ymy+78= on 11/03/2023

FIGURE 3. The unified SKSI model for recovery and rehabilitation.

than one impairment, including muscle weakness, spasticity, severe stroke may get physically deconditioned quickly,

tactile and proprioceptive sensory loss, as well as apraxia and compromising their cardiovascular capacity to participate in daily

perhaps executive dysfunction. An inability to drink from a life activities. These patients need early rehabilitation to pre-

cup is just one function that affects participation in one’s vent the adverse consequences of immobility and decondition-

self-care. Each impairment needs to be addressed to increase ing that can further compromise their recovery. However, in

function, and multiple functions must be addressed to increase our present system of care, more severely impaired patients

participation. Similarly, it is also possible that reducing only get even less rehabilitation than their less-severely impaired

one impairment might make no difference to a person’s func- counterparts as shown by the inverted pyramid (Fig. 4). This

tion. Thus, it is not surprising that patients with several and further exacerbates their disability and escalates healthcare

more severe impairments need longer and higher-dose inter- costs because of the complications of immobility and increas-

ventions and that change in function and participation may be ing dependence on others. Globally, 73% of stroke survivors

slower; nevertheless, they do occur.26–29 Second, patients with fall within 6 mos and are 4 times more likely to fracture their

FIGURE 4. The current inverted pyramid model of rehabilitation provides lower frequency and intensity of rehabilitation to the most impaired, which

can exacerbate disability and escalate healthcare costs. The desired upright pyramid model of care would deliver more frequent rehabilitation at the

highest tolerated intensity to prevent the downstream effects of immobility and deconditioning on recovery processes.

S6 www.ajpmr.com © 2023 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2023 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Volume 102, Number 2 (Suppl), February 2023 Unified Model for Stroke Recovery

Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/ajpmr by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1A

WnYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC4/OAVpDDa8KKGKV0Ymy+78= on 11/03/2023

FIGURE 5. The three dimensions of severity of impairment, acuity of stroke, and personal factors influence the rate of recovery and should be

considered in determining the frequency, intensity, duration, and content of rehabilitation interventions to optimize recovery.

hip.35 Furthermore, stroke survivors are sedentary 78% of the levels of independently mobile community-dwelling adults

time because of slow walking speed and are likely to be more greater than 3 mos after stroke, showed that physical activity

dependent.36,37 A more desired, upright pyramid model would levels in stroke survivors are influenced by social activities

deliver more frequent rehabilitation at the highest tolerated in- and support, prestroke identity, self-efficacy levels, and com-

tensity to severely impaired patients to prevent the effects of pletion of activities that are meaningful to stroke survivors.40

immobility and deconditioning on recovery processes. Perform- High-impact interventions are those that have an effect on all

ing frequent bouts of physical activity, for instance, has been three International Classification of Functioning, Disability,

shown to improve cardiovascular risk poststroke.38 and Health domains of impairment, function, and participation,

Personal and environmental factors, such as one’s prestroke by simultaneously reducing several impairments at once. Such

identity, level of motivation, attitude, self-efficacy, and access interventions typically harness natural repair mechanisms (that

to resources and support, also affect daily behaviors that impact are active during the critical period)24 and/or upregulate these

recovery from impairment, as well as function and participa- mechanisms, such as by combining aerobic exercise,41 or

tion.39 A recent systematic review of peer-reviewed, qualitative in enriched environments, for example, by incorporating music

studies on the perceived factors influencing physical activity therapy.42 Hence, delivering interventions during the acute period

TABLE 1. Differences between the current standard of care and the SKSI model of care

Current Standard of Care SKSI Model of Care

Acute hospital stroke service

• Rehabilitation consultation to determine discharge • Assess impairments, function, participation using a standard SKSI battery

destination • Medically cleared patients receive two 15- to 30-min sessions of PT, OT, and SLP each

• 1–3 therapy sessions for the duration of the length of stay daily; one focused on impairment reduction and the other on enhancing function

in the stroke unit • Patients are involved in social activity to encourage self-management and promote

• Stroke binder consisting of educational resources provided self-efficacy

by the American Heart Association

Acute inpatient rehabilitation service

• Function-focused regardless of impairment • Assess impairments, function, and participation using a standard SKSI battery

• 3 hrs of therapy per day • Optimize training time within length of stay beyond three hours of therapy per day

• One family meeting per admission • Focus on impairment reduction

• Engage and empower patients and caregivers to participate to enhance self-efficacy

• Implement a discharge algorithm to bridge the care to outpatient services

Outpatient stroke service

• Typical frequency 2–3 d/wk for PT, OT, ST, and • Assess impairments, function, and participation using a standard SKSI battery

neuropsychology if needed • Select from multiple PATH transdisciplinary programs depending on acuity, severity, and

• Struggle to discharge patients and to keep patients personal factors

• Lack of continuity of care • High-frequency PATH (4–5 d/wk)

• Intermediate-frequency PATH (2–3 d/wk)

• Low-frequency PATH (1 d/wk)

• Focus on impairment reduction

• Engage and empower patients and caregivers to participate to enhance self-efficacy

OT, occupational therapy; PATH, postacute therapy; PT, physical therapy; SLP, speech and language pathology.

© 2023 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. www.ajpmr.com S7

Copyright © 2023 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Raghavan Volume 102, Number 2 (Suppl), February 2023

or in conjunction with aerobic exercise,43,44 could be particularly 8. Cormier DJ, Frantz MA, Rand E, et al: Physiatrist referral preferences for postacute stroke

rehabilitation. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4356

beneficial. Figure 5 shows the three dimensions that greatly influ- 9. Magdon-Ismail Z, Ledneva T, Sun M, et al: Factors associated with 1-year mortality after

ence the rate of recovery–acuity of stroke, severity of impairment, discharge for acute stroke: what matters? Top Stroke Rehabil 2018;25:576–83

and personal factors–which should be considered in determining 10. Liu H, Zhu C, Cao J, et al: Hospitalization costs among immobile patients with hemorrhagic

the frequency, intensity, and content of rehabilitation interventions or ischemic stroke in China: a multicenter cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;

20:905

Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/ajpmr by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1A

to optimize recovery. 11. Naito Y, Kamiya M, Morishima N, et al: Association between out-of-bed mobilization and

complications of immobility in acute phase of severe stroke: a retrospective observational

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE STANDARD OF

study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2020;29:105112

12. Kortebein P: Rehabilitation for hospital-associated deconditioning. Am J Phys Med Rehabil

CARE AND THE UNIFIED MODEL OF CARE

WnYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC4/OAVpDDa8KKGKV0Ymy+78= on 11/03/2023

2009;88:66–77

The unified model of care for recovery and rehabilitation 13. Oyanagi K, Kitai T, Yoshimura Y, et al: Effect of early intensive rehabilitation on the clinical

outcomes of patients with acute stroke. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2021;21:623–8

at the SKSI seeks to optimize recovery by innovatively en- 14. Gordon NF, Gulanick M, Costa F, et al: Physical activity and exercise recommendations for

hancing the standard of care as shown in Table 1. This oc- stroke survivors: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Council on

curs through enhanced communication across the acute care, Clinical Cardiology, Subcommittee on Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention; the

Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and

inpatient rehabilitation, and outpatient rehabilitation settings, Metabolism; and the Stroke Council. Stroke 2004;35:1230–40

and the multidisciplinary team, which includes physicians 15. Cuccurullo SJ, Fleming TK, Kostis WJ, et al: Impact of a stroke recovery program integrating

in the departments of physical medicine and rehabilitation modified cardiac rehabilitation on all-cause mortality, cardiovascular performance and

and neurology, therapists in physical, occupational and speech functional performance. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2019;98:953–63

16. Cuccurullo SJ, Fleming TK, Kostis JB, et al: Impact of modified cardiac rehabilitation within

therapy, psychologists, nurses, researchers, and staff. Our goal a stroke recovery program on all-cause hospital readmissions. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2022;

is to develop a stroke recovery program that combines innova- 101:40–7

tive clinical care, technology, and research for predictive (iden- 17. Cuccurullo SJ, Fleming TK, Zinonos S, et al: Stroke recovery program with modified cardiac

tifying the right frequency, intensity, and content based on the rehabilitation improves mortality, functional & cardiovascular performance.

J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2022;31:106322

factors that influence recovery), preventive (providing early 18. Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, et al: 2021 guideline for the prevention of stroke

rehabilitation to prevent the complications of immobility), in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline from the American Heart

personalized (considering the personal factors that influence Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2021;52:e364–467

recovery), and participatory (engaging patients throughout 19. Duncan PW, Bushnell C, Sissine M, et al: Comprehensive stroke care and outcomes: time for

a paradigm shift. Stroke 2021;52:385–93

the continuum) rehabilitation. 20. Raghavan P: Upper limb motor impairment after stroke. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2015;

26:599–610

21. Levin MF, Kleim JA, Wolf SL: What do motor “recovery” and “compensation” mean in

CONCLUSIONS patients following stroke? Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2009;23:313–9

Implementation of the SKSI model requires that we learn 22. Stinear CM, Byblow WD, Ackerley SJ, et al: Predicting recovery potential for individual

from and teach one another. It has led to the development of stroke patients increases rehabilitation efficiency. Stroke 2017;48:1011–9

better standards of practice to ensure more effective stroke 23. Prabhakaran S, Zarahn E, Riley C, et al: Inter-individual variability in the capacity for motor

recovery after ischemic stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2008;22:64–71

systems of care across the continuum informed by the latest 24. Carmichael ST: Emergent properties of neural repair: elemental biology to therapeutic

scientific research and discovery. The articles in this sup- concepts. Ann Neurol 2016;79:895–906

plement represent a synthesis of our collective effort and 25. Hayward KS, Kramer SF, Dalton EJ, et al: Timing and dose of upper limb motor intervention

an attempt to share our learnings toward a recovery-focused after stroke: a systematic review. Stroke 2021;52:3706–17

26. Daly JJ, McCabe JP, Holcomb J, et al: Long-dose intensive therapy is necessary for strong,

learning network. clinically significant, upper limb functional gains and retained gains in severe/moderate

chronic stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2019;33:523–37

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 27. Ward NS, Brander F, Kelly K: Intensive upper limb neurorehabilitation in chronic stroke:

outcomes from the Queen Square programme. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2019;90:

The author thanks Dr Pablo Celnik, Dr Justin McArthur, 498–506

and faculty and staff from the departments of physical medi- 28. Mawase F, Cherry-Allen K, Xu J, et al: Pushing the rehabilitation boundaries: hand

cine and rehabilitation and neurology involved in the Sheikh motor impairment can be reduced in chronic stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2020;

Khalifa Stroke Institute. 34:733–45

29. Boissoneault C, Grimes T, Rose DK, et al: Innovative long-dose neurorehabilitation for

balance and mobility in chronic stroke: a preliminary case series. Brain Sci 2020;10:555

REFERENCES 30. O’Keeffe R, Shirazi SY, Bilaloglu S, et al: Nonlinear functional muscle network based on

information theory tracks sensorimotor integration post stroke. Sci Rep 2022;12:13029

1. GBD 2016 Stroke Collaborators: Global, regional, and national burden of stroke, 1990–2016: 31. Dromerick AW, Geed S, Barth J, et al: Critical Period After Stroke Study (CPASS): a phase II

a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2019;18: clinical trial testing an optimal time for motor recovery after stroke in humans.

439–58 Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021;118:e2026676118

2. Ovbiagele B, Goldstein LB, Higashida RT, et al: Forecasting the future of stroke in the United

32. Brosseau L, Raman S, Fourn L, et al: Recovery time of independent poststroke abilities: part I.

States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association and American Stroke

Top Stroke Rehabil 2001;8:60–71

Association. Stroke 2013;44:2361–75

33. Brosseau L, Raman S, Fourn L, et al: Recovery time of independent poststroke life habits: part

3. Jaberinezhad M, Farhoudi M, Nejadghaderi SA, et al: The burden of stroke and its attributable

II. Top Stroke Rehabil 2001;8:46–55

risk factors in the Middle East and North Africa region, 1990–2019. Sci Rep 2022;12:2700

4. Raghavan P: Research in the acute rehabilitation setting: a bridge too far? 34. World Health Organization: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and

Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2019;19:4 Health (ICF). Geneva, Switzerland, WHO, 2001

5. Winstein CJ, Stein J, Arena R, et al: Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery: a 35. Forster A, Young J: Incidence and consequences of falls due to stroke: a systematic inquiry.

guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke BMJ 1995;311:83–6

Association. Stroke 2016;47:e98–169 36. Fini NA, Holland AE, Keating J, et al: How physically active are people following stroke?

6. Stein J, Bettger JP, Sicklick A, et al: Use of a standardized assessment to predict rehabilitation Systematic review and quantitative synthesis. Phys Ther 2017;97:707–17

care after acute stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015;96:210–7 37. Fini NA, Bernhardt J, Holland AE: Low gait speed is associated with low physical activity and

7. Magdon-Ismail Z, Sicklick A, Hedeman R, et al: Selection of postacute stroke rehabilitation high sedentary time following stroke. Disabil Rehabil 2021;43:2001–8

facilities: a survey of discharge planners from the Northeast Cerebrovascular Consortium 38. Fini NA, Bernhardt J, Churilov L, et al: A 2-year longitudinal study of physical activity and

(NECC) region. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3206 cardiovascular risk in survivors of stroke. Phys Ther 2021;101:pzaa205

S8 www.ajpmr.com © 2023 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2023 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Volume 102, Number 2 (Suppl), February 2023 Unified Model for Stroke Recovery

39. Jorgensen HS, Pedersen PM, Kammersgaard L, et al: Epidemiology of stroke related 42. Palumbo A, Aluru V, Battaglia J, et al: Music upper limb therapy-integrated provides a feasible

disability, in Duncan PW (ed): Clinics in Geriatric Medicine: Stroke. Philadelphia, PA, WB enriched environment and reduces post-stroke depression: a pilot randomized controlled trial.

Saunders, 1999:785–800 Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2022;101:937–46

40. Espernberger KR, Fini NA, Peiris CL: Personal and social factors that influence physical 43. Linder SM, Rosenfeldt AB, Davidson S, et al: Forced, not voluntary, aerobic exercise enhances

activity levels in community-dwelling stroke survivors: a systematic review of qualitative motor recovery in persons with chronic stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2019;33:681–90

literature. Clin Rehabil 2021;35:1044–55 44. Ploughman M, Eskes GA, Kelly LP, et al: Synergistic benefits of combined aerobic and

41. Ashcroft SK, Ironside DD, Johnson L, et al: Effect of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor in cognitive training on fluid intelligence and the role of IGF-1 in chronic stroke.

Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/ajpmr by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1A

stroke survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2022;53:3706–16 Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2019;33:199–212

WnYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC4/OAVpDDa8KKGKV0Ymy+78= on 11/03/2023

© 2023 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. www.ajpmr.com S9

Copyright © 2023 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- CANINE-Cricopharyngeal Achalasia in DogsDocument6 pagesCANINE-Cricopharyngeal Achalasia in Dogstaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Ati Codes Cont'Document1 pageAti Codes Cont'm1k0eNo ratings yet

- A Unified Model For Stroke Recovery And.2Document7 pagesA Unified Model For Stroke Recovery And.2Fonoaudiólogos En cuidado crítico ColombiaNo ratings yet

- Addressing The Operational Challenges For.12Document7 pagesAddressing The Operational Challenges For.12Papu FloresNo ratings yet

- Bringing High Dose Neurorestorative Behavioral.7Document5 pagesBringing High Dose Neurorestorative Behavioral.7Papu FloresNo ratings yet

- Stroke Rehabilitation bmj-334-7584-cr-00086Document5 pagesStroke Rehabilitation bmj-334-7584-cr-00086antonio tongNo ratings yet

- World Journal of Emergency Surgery: Preventable Trauma Deaths: From Panel Review To Population Based-StudiesDocument7 pagesWorld Journal of Emergency Surgery: Preventable Trauma Deaths: From Panel Review To Population Based-StudiesRita RangelNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Tati Social Support .PDF 2Document3 pagesJurnal Tati Social Support .PDF 2Artati ArsyadNo ratings yet

- Rehabilitation After Stroke PDFDocument8 pagesRehabilitation After Stroke PDFBetaNo ratings yet

- 184310-Article Text-469055-1-10-20190307Document3 pages184310-Article Text-469055-1-10-20190307Sandy AkbarNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Evaluation Before Noncardiac Surgery.Document16 pagesPreoperative Evaluation Before Noncardiac Surgery.Paloma AcostaNo ratings yet

- 2015 LeeuwenbergDocument10 pages2015 LeeuwenbergPaulHerreraNo ratings yet

- Early Management of The Severely Injured Major Trauma PatientDocument8 pagesEarly Management of The Severely Injured Major Trauma PatientAngela Mitchelle NyanganNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Evaluation Before NoncardiacDocument16 pagesPreoperative Evaluation Before NoncardiacHercilioNo ratings yet

- Stroke Unit Brochure v7 Pages No CropDocument8 pagesStroke Unit Brochure v7 Pages No Cropsatyagraha84No ratings yet

- Team Approach - Modern-Day Prostheses in The Mangled HandDocument9 pagesTeam Approach - Modern-Day Prostheses in The Mangled HandTRAUMATOLOGIA HEGNo ratings yet

- ProspektifDocument3 pagesProspektifElsa Indah SuryaniNo ratings yet

- Stroke Rehabilitation - ELFINDYADocument4 pagesStroke Rehabilitation - ELFINDYAGendis Giona SudjaNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Acute Ischemic StrokeDocument25 pagesTreatment of Acute Ischemic StrokeLauraGutierrezNo ratings yet

- Critical Care For The Patient With Multiple TraumaDocument12 pagesCritical Care For The Patient With Multiple TraumaSyifa Aulia AzizNo ratings yet

- SurgeCapacityPrinciples MCC2014Document17 pagesSurgeCapacityPrinciples MCC2014Shubhra PaulNo ratings yet

- Ask The Experts: Evidence-Based Practice: Percussion and Vibration TherapyDocument3 pagesAsk The Experts: Evidence-Based Practice: Percussion and Vibration Therapysebastian arayaNo ratings yet

- Pressure Ulcers From Spinal Immobilization in Trauma Patients: A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesPressure Ulcers From Spinal Immobilization in Trauma Patients: A Systematic ReviewgesnerxavierNo ratings yet

- Sheikh Khalifa Stroke Institute at Johns Hopkins .1Document2 pagesSheikh Khalifa Stroke Institute at Johns Hopkins .1Papu FloresNo ratings yet

- Clinmed 17 2 173Document5 pagesClinmed 17 2 173ERIKA FRANCE BORJANo ratings yet

- Aba QuemadurasDocument15 pagesAba QuemadurasAndreys Argel TovarNo ratings yet

- The Principles of The Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) Framework in Spinal TraumaDocument12 pagesThe Principles of The Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) Framework in Spinal TraumaSamuel ManurungNo ratings yet

- Effects of Aggressive and Conservative Strategies For Mechanical Ventilation LiberationDocument9 pagesEffects of Aggressive and Conservative Strategies For Mechanical Ventilation LiberationGurmeet SinghNo ratings yet

- Preope Mayo Clinic 2020Document16 pagesPreope Mayo Clinic 2020claauherreraNo ratings yet

- Critical Care Considerations in Trauma - Overview, Trauma Systems, Initial Assessment PDFDocument19 pagesCritical Care Considerations in Trauma - Overview, Trauma Systems, Initial Assessment PDFPaulina Jiménez JáureguiNo ratings yet

- Damage Control Surgery and ICU (Feb-14-08)Document10 pagesDamage Control Surgery and ICU (Feb-14-08)Agung Sari WijayantiNo ratings yet

- Acute Management of Open Fractures Proposal of A New Multidisciplinary AlgorithmDocument5 pagesAcute Management of Open Fractures Proposal of A New Multidisciplinary AlgorithmLuigi Paolo Zapata DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Damage Control Resuscitation in Pediatric Trauma .4Document9 pagesDamage Control Resuscitation in Pediatric Trauma .4amanda.gomesNo ratings yet

- Management of Traumatic Spinal Cord Injuries:: Current Standard of Care RevisitedDocument4 pagesManagement of Traumatic Spinal Cord Injuries:: Current Standard of Care RevisitedMuhammad Avicenna Abdul SyukurNo ratings yet

- Evolving A Successful Acute Care Surgical/Surgical Critical Care Group at A Nontrauma HospitalDocument6 pagesEvolving A Successful Acute Care Surgical/Surgical Critical Care Group at A Nontrauma HospitalГне ДзжNo ratings yet

- Nihms 965820Document15 pagesNihms 965820Indira Ulfa DunandNo ratings yet

- Echocardiography in ShockDocument7 pagesEchocardiography in ShockRaul ForjanNo ratings yet

- Ebook Cardiovaskuler Disease StrokeDocument9 pagesEbook Cardiovaskuler Disease StrokearisNo ratings yet

- Sfad 156Document17 pagesSfad 156azizk83No ratings yet

- Guidelines For Safe Transfer of The Brain-Injured Patient: Trauma and Stroke, 2019Document13 pagesGuidelines For Safe Transfer of The Brain-Injured Patient: Trauma and Stroke, 2019VasFel GicoNo ratings yet

- A Functional Recovery Profile For Patients With Stroke Following Post-Acute Rehabilitation Care in TaiwanDocument8 pagesA Functional Recovery Profile For Patients With Stroke Following Post-Acute Rehabilitation Care in TaiwanDiilNo ratings yet

- Broderick 2015Document4 pagesBroderick 2015Jimmy SilverhandNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Arrest in The Perioperative Period A.3Document13 pagesCardiac Arrest in The Perioperative Period A.3qpzcqq8kq6No ratings yet

- Crameretal 2017 Recoveryrehab IssuesDocument8 pagesCrameretal 2017 Recoveryrehab IssuesNovia RambakNo ratings yet

- CPR EthicsDocument51 pagesCPR EthicsDoha EbedNo ratings yet

- 2 Art Ingles IJA-67-39Document9 pages2 Art Ingles IJA-67-39Vanesa Osco SilloNo ratings yet

- LS 1134 Rev A Early Mobility and Walking Program PDFDocument10 pagesLS 1134 Rev A Early Mobility and Walking Program PDFYANNo ratings yet

- Hirsch Et Al 2023 Critical Care Management of Patients After Cardiac Arrest A Scientific Statement From The AmericanDocument33 pagesHirsch Et Al 2023 Critical Care Management of Patients After Cardiac Arrest A Scientific Statement From The AmericanHelder LezamaNo ratings yet

- Care of The Critically Ill PatientDocument9 pagesCare of The Critically Ill Patientdayana perdomoNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Management of Heart Transplantation A Clinical ReviewDocument18 pagesPerioperative Management of Heart Transplantation A Clinical ReviewMichael PimentelNo ratings yet

- Practneurol 2020 002557Document13 pagesPractneurol 2020 002557Deagittha Cinth'a CmmuaNo ratings yet

- Integrated Acute Stroke Unit Care: ReviewDocument9 pagesIntegrated Acute Stroke Unit Care: Reviewsatyagraha84No ratings yet

- Early Occupational Therapy Intervention in The Hospital Discharge After StrokeDocument11 pagesEarly Occupational Therapy Intervention in The Hospital Discharge After Strokeali veliNo ratings yet

- Early Mobilization in The Critical Care Unit - A Review of Adult ADocument11 pagesEarly Mobilization in The Critical Care Unit - A Review of Adult Aanggaarfina051821No ratings yet

- Pitch-Side Management of Acute Shoulder Dislocations: A Conceptual ReviewDocument9 pagesPitch-Side Management of Acute Shoulder Dislocations: A Conceptual ReviewElan R.S.No ratings yet

- 5 4 Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine In.20Document6 pages5 4 Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine In.20Carlyna Septi AisyaNo ratings yet

- Hospital Impact Long Terms IssuesDocument20 pagesHospital Impact Long Terms IssuesydtrgnNo ratings yet

- Hospital Impact Internal DisastersDocument20 pagesHospital Impact Internal DisastersydtrgnNo ratings yet

- Dispositivo Assistência VentricularDocument7 pagesDispositivo Assistência Ventricularjuliane gavazziNo ratings yet

- Damage Control Resuscitation: Identification and Treatment of Life-Threatening HemorrhageFrom EverandDamage Control Resuscitation: Identification and Treatment of Life-Threatening HemorrhagePhilip C. SpinellaNo ratings yet

- Target Volume Delineation for Pediatric CancersFrom EverandTarget Volume Delineation for Pediatric CancersStephanie A. TerezakisNo ratings yet

- 12 Strokes: A Case-based Guide to Acute Ischemic Stroke ManagementFrom Everand12 Strokes: A Case-based Guide to Acute Ischemic Stroke ManagementFerdinand K. HuiNo ratings yet

- Astm Curs Stud 22-23Document44 pagesAstm Curs Stud 22-23Irina ASNo ratings yet

- Centers For TherapyDocument2 pagesCenters For TherapyCeline JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Dissolution Specifications For Oral Drug Products (IR, DR, ER) in The USA - A Regulatory PerspectiveDocument6 pagesDissolution Specifications For Oral Drug Products (IR, DR, ER) in The USA - A Regulatory PerspectiveFaisal AbbasNo ratings yet

- Drug Study - Ambroxol, AmpicillinDocument3 pagesDrug Study - Ambroxol, AmpicillinPaul John RutaquioNo ratings yet

- Approach To Abdominal PainDocument44 pagesApproach To Abdominal PainEleanorNo ratings yet

- Healing Touch Untuk KecemasanDocument6 pagesHealing Touch Untuk KecemasanElvaNo ratings yet

- Insulin: Insulin Injections (Insulin by Category) Course Agent Onset Peak DurationDocument2 pagesInsulin: Insulin Injections (Insulin by Category) Course Agent Onset Peak DurationDonna R MercerNo ratings yet

- PACES Revision Obstetrics and Gynaecology: 27/04/2012 Amrita Banerjee & Ola MarkiewiczDocument62 pagesPACES Revision Obstetrics and Gynaecology: 27/04/2012 Amrita Banerjee & Ola MarkiewiczThistell ThistleNo ratings yet

- PTC Slides 2016Document290 pagesPTC Slides 2016graceduma100% (1)

- Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Atan Baas Sinuhaji, Spa (K)Document35 pagesSupervisor: Prof. Dr. Atan Baas Sinuhaji, Spa (K)Ranap HadiyantoNo ratings yet

- Anti Adrenergic Drugs ArpanDocument8 pagesAnti Adrenergic Drugs ArpanA2Z GyanNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Vascular SurgeryDocument13 pagesIntroduction To Vascular Surgeryapi-3858544100% (1)

- Classification Criteria For Psoriatic Arthritis and ASDocument16 pagesClassification Criteria For Psoriatic Arthritis and ASSri Vijay Anand K SNo ratings yet

- Lower Extremity AmputationsDocument42 pagesLower Extremity Amputationsalinutza_childNo ratings yet

- 4 Health Information SystemDocument25 pages4 Health Information Systemflordeliza magallanesNo ratings yet

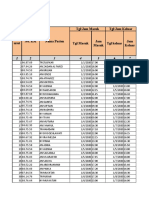

- Register Rawat Inap 2020Document327 pagesRegister Rawat Inap 2020carolinaNo ratings yet

- Management of Diabetes Ketoacidosis in PregnancyDocument19 pagesManagement of Diabetes Ketoacidosis in PregnancySudhir PaulNo ratings yet

- Ferret OrthopedicsDocument27 pagesFerret OrthopedicsTayná P DobnerNo ratings yet

- 10 Health Benefits of Physical Fitness: Reduces The Risk of DiseasesDocument4 pages10 Health Benefits of Physical Fitness: Reduces The Risk of DiseasesEDGAR PALOMANo ratings yet

- Health and Wellness Notes 1 EditeDocument13 pagesHealth and Wellness Notes 1 EditeSOCIAL PLACENo ratings yet

- Quick Reference DMARDsDocument12 pagesQuick Reference DMARDsEman MohamedNo ratings yet

- Choanal AtresiaDocument7 pagesChoanal AtresiaAmmar EidNo ratings yet

- Electrolyte ReplacementDocument20 pagesElectrolyte Replacementamal.fathullahNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Kualitas Tidur Dan Konsumsi Tablet Fe Dengan Kejadian Anemia Ibu HamilDocument7 pagesHubungan Kualitas Tidur Dan Konsumsi Tablet Fe Dengan Kejadian Anemia Ibu Hamilsanty ireneNo ratings yet

- Teknik SutureDocument60 pagesTeknik SutureAnizha AdriyaniNo ratings yet

- TB Contact InvestigationDocument16 pagesTB Contact Investigationdjprh tbdotsNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Nerve Stimulation PH Neuralgia Li 2015Document3 pagesPeripheral Nerve Stimulation PH Neuralgia Li 2015fajarrudy qimindraNo ratings yet

- Blood Culture CollectionDocument18 pagesBlood Culture CollectionLiz Escueta100% (1)