Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Assessment of English Textbooks in Nigeria

Assessment of English Textbooks in Nigeria

Uploaded by

Muhammad AbduljalilOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Assessment of English Textbooks in Nigeria

Assessment of English Textbooks in Nigeria

Uploaded by

Muhammad AbduljalilCopyright:

Available Formats

ISSN 1798-4769

Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 1, No. 5, pp. 656-661, September 2010

© 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland.

doi:10.4304/jltr.1.5.656-661

A Critical Assessment of the Cultural Content of

Two Primary English Textbooks Used in Nigeria

Stephen Billy Olajide

Department of Arts and Social Sciences Education, Faculty of Education, University of Ilorin, Nigeria

Email: olajide.billy@yahoo.com; billyolajide@unilorin.edu.ng

Abstract—Culture (a people’s ways of life) and literacy (the permanent possession of the skills of reading,

writing and numeracy) are two sides of the same coin. The former prepares the individual through approved

social roles, while latter ensures that the former is not only promoted and preserved, but also made more

functional. Then the textbook is a powerful medium for cultural sustenance and literacy development. The

language textbook in particular is vital to making culture relevant to intellectual development. One aim of

language teaching-learning is to produce the learner who would not only be able to engage in the four

language skills rewardingly, but also be culturally literate. Unfortunately, culture is not monolithic, just as

different writers have different visions and styles for their art. Every nation also has what she wants education

to do for her, which must include cultural revival and cultural integration. In this era of globalization, culture,

especially if it lacks technological base, can be dangerously disadvantaged. This researcher sought to evaluate

the cultural content of two basal textbooks used in teaching Primary school English in a Second context with a

view to determining how the writers have reflected cultural context. Based on the findings from the study,

recommendations were made to course book writers and relevant other stakeholders.

Index Terms—cultural content, primary school English, literacy

I. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

It is not possible to give a watertight definition of culture as it has been many things to many people. Kramsch (1998)

views it as the membership of a discourse community that shares a common social space and history. They have

common world views, beliefs and ways of assessing things, situations and events. In this regard, culture involves

knowledge derived unconsciously and utilized as a social property. The knowledge dictates how the community

socialise. Culture could inform their attitude to language. Miekley (2005) reports how major countries of South East

Asia, seeing the international ascendancy being enjoyed by English, embarked on very intense programmes to entrench

the language and how majority of the citizens had either not been able to use it appreciably or had refused outright the

language. He gives a graphic insight into English language textbook situation in those countries involving massive

production of instructional materials by native and non native experts. However, Miekley has not provided information

concerning the cultural relevance of such materials. Akintunde (1993:391) suggests that the origin and design of

language a textbook could influence its relevance and how successfully it may be used in the classroom. He identifies

government polices, publishing infrastructure, intellectual and professional associations as the cultural matrices for

book development. He is at one with Emenyonu (1993:402-404) who gives specific steps that could be taken in infusing

relevant cultural experiences in a book. The steps the latter has proposed include:

1. reflecting the physical context of language learning.

2. considering the economic characteristics of the target readers.

3. examining the political aspects of the community.

4. defining the role of culture.

5. indicating the economic conditions of the people.

Any education situated in man’s culture makes him not only well-developed and integrated but also enables him to

appreciate other peoples’ cultures. According to Courtney (1974:140):

Through his culture man learns to relate himself with the society and by storing up past knowledge in symbolic from,

he can visualize future possibilities and consciously adapt himself through reason. Man emerged from primitive

animism to being only vaguely aware of his separate existence.

Man’s cultural experiences get him to a level at which he attains cosmic unity with the society and the world, by

which he is not lonely and is better protected. The role man’s cultural background plays in his fortune and misfortune

has been attested to by Obafemi (1994:86) in his explanation of the source of drama: ‘’In spite of this elasticity in form

and content of drama, certain adamants characterize the discipline’’, including:

(i) imitation of human behaviour.

(ii) characters acting in situation and style, and

(iii) dramatic structure that involves time, place and action.

© 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER

JOURNAL OF LANGUAGE TEACHING AND RESEARCH 657

Indeed, as espoused by Holly (1990), language teaching carries cultural and ideological messages. The experiences

shared in the classroom reflect a particular culture and promote specific socio - economic and political values; they also

aim at advancing some spiritual inclinations. Such experiences - cultural contents - transmit more daily and effectively

if they derive from textual materials which enjoy permanence.

The role that textbooks (especially language textbooks) play in behaviour modification has been well explained in the

literature. Their vitality has made language educators and applied linguists suggest many criteria for assessing (critically

pointing out the weaknesses and strengths of) such materials. For example, Kilickaya (2004) and Olajide (2004) are

agreed that language textbooks should satisfy the cultural context in which they are going to be implemented. Kilickaya

specifically suggests that the following criteria be applied in assessing the cultural component of the textbooks.

1. Does the book suggest how the cultural content may be handled?

2. What learner characteristics does the book address?

3. Does the book specify any role for the teacher using it?

4. Does the book reflect a variety of culture?

5. Is the content of the book realistic about the target culture?

6. What is the source of cultural information (author’s view or empirically derived)?

7. Do the subjects of the book relate directly to the target culture, and are there topics not culturally suitable for

the class?

8. What cultural and social categories of people does the content address?

9. Does the book contain cultural generalizations and specific inferences and insinuations?

10. Does it contain positive, negative or no comments about the cultural information it presents?

11. If illustrations are made in the textbook are they appropriate to the learners’ native culture?

12. Are familiar activities presented to the learners?

13. Would the teacher need specialized training to be able to use the book?

14. Does the book encourage the learners to utilize the cultural experiences beyond the classroom?

15. What is your own opinion of the book?

The foregoing criteria by Kilickaya (2004) and those by Emenyonu (1993) are considered appropriate for the present

study because of their cultural focus.

The English Language textbooks used at the primary school level (referred to as Primary English in this paper) are

important. They are a part of the process of forming the impressionistic adolescents whose experiences at that stage

would shape their lives thereafter. For example, in Nigeria, English occupies a critical place in education and is fast

assuming the status of a Nigerian language (Olajide 2004 & 2009). The primary school teacher of English in the

country in particular has a great role to play, because he/she is responsible for granting the platform where the young

learner is encountering English probably for the first time and requires careful facilitation to be able to transit from his

mother tongue base. The country expects English to take over after the first three years as the medium of instruction.

Thus, the language influences the acquisition of litero-numeracy skills as from mid-primary level (Federal Republic of

Nigeria, 2007). Incidentally, the textbook situation in Nigeria is hardly different from that of South East Asia as

reported by Miekley (2005) and many other developing countries. There are many English language textbooks that the

Nigerian primary school teacher needs to choose from, but not all of the textbooks would do teaching-learning much

good. Hence, there is need to assess the books before selecting from them.

II. STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM AND PURPOSE

Language and culture are intertwined and teaching the former in the second or foreign situation requires the teacher

to be sensitive to the latter Kramsch (1998). Second or Foreign language situation poses unique challenges in that the

learners come to the classrooms with different cultural and linguistic backgrounds. It becomes necessary for the

materials implemented in the classroom to reflect the culture of the learner. Different scholars (Holly 1990, Akintunde

1993, Emenyonu, 1993, Holly 1990, Olajide 1995 & 2004, and Kilickaya, 2004) have justified the assessment of

language textbooks. And there have been unending outcries about poor pupil performance in English at the primary

school level in Nigeria. It is not certain how much the content of the English textbooks implemented at that level

reflects the pupils’ cultural backgrounds. It is also a problem that available literature has not shown quantitatively if the

cultural contents of the books cut across international boundaries as recommend by Kilickaya (2004) Olajide (2004) and

Miekley (2005).

Thus, the general purpose of this study was to ascertain if each of two English textbooks popularly used in Nigeria

primary schools have adequate cultural contents. Specifically, the study sought to provide answers to the following

questions motivated from available literature.

1. Does each of the books reflect physical features?

2. Does each of the books include socio-economic characteristic?

3. Does each of the books relate to political activities?

4. Does each of the books portray living condition?

5. If each involves living conditions, do such living conditions reflect rural urban- dichotomy?

6. Does each book suggest how the cultural content may be used in, and beyond the classroom?

© 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER

658 JOURNAL OF LANGUAGE TEACHING AND RESEARCH

7. What learner characteristics does each of the books contain?

8. Does each book reflect a variety of cultures?

9. How realistic is each of the books about the culture it aims at portraying?

10. Is the culture aimed in each book based on author’s opinion?

11. Is the culture contained in each book derived empirically?

12. Do the topics in each book directly refer to target culture?

13. Are there cultural items in the books not relevant to the users’ culture?

14. What cultural and social categories does each of the books address?

15. Does each of the books contain cultural generalizations that ought not to be made?

16. Does the book contain positive comments about the cultural information passed?

17. Does the book contain negative comments on the cultural content presented?

18. How appropriate are the cultural illustrations made, if any, in each of the books?

19. Are familiar activities presented in each of the books?

20. Does each of the books encourage the learner to utilize the cultural experiences beyond the classroom?

III. METHODOLOGY

This study involved two textbooks – “Nigeria Primary School English Pupils’ Book 1’’ and the “Longman

Advantage Primary English Pupils’ Book 1, the former having been published by Longman and the latter by Pearson

and Longman. (The former will henceforth be referred to as PSEB1 and the latter as ADVE1.) The choice of both books

by the same publishers was informed by the international experience of the publishers and the fact that this investigator

once evaluated a series of Longman’s publications for secondary schools (Olajide 2004) and wished to see if Longman

is consistent in its attitude to learners’ culture. More important is that this investigator considered the primary school

level as being crucial to the formation of language habits and building of literacy and numeracy skills. The investigation

involved careful isolation of the cultural content available within each text. The tabulation of the content was done in

line with the 20 specific purposes already stated which derived from Emenyonu (1993) and Kilichaya (2005). The

specific purposes may be viewed as equivalents of, and alternatives to, research questions this investigator could have

posed separately. Frequency count and percentage were used to analyse the cultural data observed in the books.

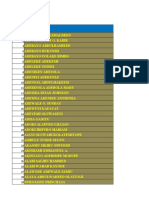

IV. DATA ANALYSIS

In this section, the relevant cultural content of each book is identified, analysed and discussed in Table 1.

V. SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

From the analysis in table 1, above, the following summary of findings can be made:

1. Both books contain familiar physical features, although to differing degrees (8% in PSEB1 and 23% in ADVE1).

2. They also contain relevant economic activities differently (12% in PSEB1 and 22.6% in ADVE1).

3. While only 1% of PSEB1 relates to political activities, ADVE1pays no clear attention to such activities.

4. However, the books address living conditions of people (12% in PSEB1 and 5.3% in ADVE1)

Also, they reflect the urban-rural dichotomy in living condition (10% in PSEB1 and 4.3% in ADVE1)

5. Both books pay attention to how their cultural content may be handled by both pupils and teachers.

6. Nevertheless, the books fairly reflect the characteristics of learners in the cultural activities they contain (15% in

PSEB1 and 13.1% in ADVE1)

7. They also reflect a variety of cultures (09% in PSEB1 and 2.7% in ADVE1)

8. They are somewhat realistic in the culture they portray (3% in PSEB1 and 2.7% in ADVE1)

9. In both books, authors express no personal opinions.

10. More of the cultural content of PSEB1 (6%) is empirically derived than that of ADVE1 (2.7%)

11. Neither of the books directly refers to a target culture.

12. Neither of the books contains cultural content irrelevant to the learners.

13. The books are weak regarding the categorization of socio-cultural elements (only 4% of PSEB1 relates to such

categorization, while only 2.7% of ADVE1 does).

14. While 2% of ADVE1 contains unexpected cultural generalizations, PSEB1 has not made any of such

generalizations.

15. Both books contain neither negative nor positive comments on their cultural contents.

16. The books make equally considerable illustrations of the cultural contents involved (24% each)

17. PSEB1 contains more (24%) of familiar activities than ADVE1 that has only 8% of such activities

18. While PSEB1 does not encourage the learners to use the cultural information provided in the classroom, 3.4% of

ADVE1 does.

© 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER

JOURNAL OF LANGUAGE TEACHING AND RESEARCH 659

TABLE 1:

PRESENTATION OF THE CULTURAL CONTENTS OF THE TWO BOOKS.

PSEB 1 ADVE 1

CULTURE RELATED

S/NO

QUESTIONS PAGES

Y N PAGES FOUND F % Y N F %

FOUND

1,2,7,9,12,17,21

,24,32,33,36,39,

Does the book reflect familiar

1 1,2,15,16,26,57,75,83. √ 41,42,45,49,60, 23 24

physical features? √ 08 8

63,66,84,92,94,

97.

9,17,21,24,28,3

Does the book contain socio- 2,36,39,42,45,4

2 economic activities relevant 28,29. √ 9,52,59,63,66,7 22 23

√ 02 28

to the environment? 1,74,77,84,85,1

00,104

Does the book relate to

3 73. √ Nil Nil Nil

political activities? √ 01 1

Does the book project living 30,32,33,55,58,61,68, 28,32,36,52,54,

4 √ 05 5.3

conditions? √ 71,74,77. 10 10 56.

Does the living condition

5 projected reflect rural-urban 16,17,30,58,61,71. √ 32,36,56,104. 04 4.3

√ 07 7

dichotomy?

Does the book suggest how

6 its cultural content may be Nil √ Nil Nil Nil

√ Nil Nil

handled?

1,2,11,12,31,57,58,59, 1,2,5,7,9,11,17,

What learner characteristics 13.

7 61, 68, 71, √ 21,28,61,67,81, 13

reflected in the book? √ 15 15

79,83,84,85. 88.

Does the book reflect a 11,12,35,58,75,76,77,

8 √ 81,104 02 2.7

variety of culture? √ 78,83. 09 9

Is the book realistic about the

9 75,76,77. √ 81,104 02 2.7

culture[s] it portrays? √ 03 3

Is the culture aimed in the

No authorial

10 book based on the author’s √ Nil Nil Nil

√ intervention. Nil Nil

opinion?

Is the culture the book

11 15,58,70,75,78,83. √ 81,104 02 2.7

contains derived empirically? √ 06 6

Do the topics in the book Nil: cultural

12 directly refer to target references are made √ Nil Nil Nil

√ Nil Nil

culture? pictorially

Are there cultural items in the

13 book not relevant to the users’ Nil Nil Nil Nil

√ Nil Nil √

culture?

Are there socio-cultural

14 1,75,76,77. 04 4 81,104 02 2.7

categories in the book? √ √

The book contains cultural

15 Nil Nil Nil 81,104 02 2.7

generalizations not expected? √ √

Does the book contains

16 positive comments on the Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil

√

cultural information passed? √

The book contains negative

Nil

17 comments on the cultural Nil Nil Nil Nil

√

information it passes?

2,4,11,17,24,32,

11,12,13,14,15,16,17,

42,45,49,59,63,

Are appropriate illustrations 18,19,20,58,61,74,75,

18 66,71,74,75,77, 24 24

made in the book? √ 76,77,78,79,80,81,82, 24 24

√ 81,84,88,91,92,

83,84,85.

95,100,104.

11,12,13,14,15,16,7,1

Are familiar activities 9,39,45,52,88,9

19 8,19,20,21,22,23,35,3 08 8.

presented in the book? √ 21 21 √ 7,100,104

6,71,73,76'

Does the book encourage the

20 learners to use the cultural Nil Nil 9,17,19 03 3.4

√

information?

KEY:

Y: Yes

N: No

F: Frequency of occurrence.

PSEB1: Primary English Book1 (see References.

ADVE1: Advantage English Book1 (see References.)

© 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER

660 JOURNAL OF LANGUAGE TEACHING AND RESEARCH

The attention paid to the physical environment in the books may be viewed as appropriate, since young learners

require familiarity with their environment in forming their worldviews as advocated by Akintunde (1993), Emenyonu

(1993), Kramsch (1998) and Kilichaya (2004). Also, the use of familiar activities by the authors of both books can

make the learning of English easy for the pupils. However, the authors’ neglect of political cultures would seem not

quite appropriate, because learners need to be sensitized to democratic values right from their formative years. The slim

attention paid to living condition in both books is also not good enough, because exposing the young learners to such

conditions could develop in them the sympathy, appreciation and empathy which human community need to be able to

live in peace and harmony and make excellent progress. By not providing information on how the cultural content of

the books may be used, the authors have not helped creativity, whereas the world can best be preserved and promoted

through creative intellect (Courtney 1974, Emenyonu 1993, Obafemi, 1994, Kilichaya 2004). Also, as suggested by

Kramsch (1998) and Olajide, 2004, increased creativity through language learning could lead to appropriate language

attitude, and vice versa. Both books should have utilized the considerable insights they offer into learner characteristics

in promoting creativity. The variety of culture the books provide is, however, adequate. It will be prepare learners for

living across geographical boundaries, which is in line with globalisation. Akintunde (1993) and Olajide (2004) are

agreed that effective language textbooks should prepare learners for international living.

By being realistic and empirical about the cultural experiences they offer the learners, the authors made the books

usable, memorable and apt. That the authors have not included their personal opinions in the books is also instructive:

they seem not willing to force ideas into the young and impressionistic learners! Also, the children cannot be engaged in

long and intellectually demanding discourse because of their limited experiences and weak language base. The

illustrations made in the two books are also useful devices; they aid and stimulate the learners by appealing to their

senses of sight, smell, touch, taste, movement and hearing. The use of familiar activities can also increase the sense of

identity among the children as advocated by Akintunde (1993) and make education a productive enterprise for them.

Education for creativity is what the world encourages greatly today. However, such productivity would seem to have

been lacking in Nigeria education, which has resulted in the un-employability of graduates!

The books seem to rate low for not providing information about how their cultural contents may be used. They

should have used appropriate evaluation modes to cause the learners to use the cultural contents. The exercises provided

by the authors have mainly targeted the development of language skills rather than situating such skills in cultural,

creative and productive contexts.

VI. CONCLUDING REMARKS

The two books under investigation have shown considerable but differing sensitivity to cultural content. They have

paid attention to the psychological age of the learners and reflected Nigeria’s desire for education that can globalize the

learners, apart from sensitizing them to their immediate environment. However, the authors will need to build in

evaluation modes that can ensure that learners actually utilize the cultural contents provided. Such cultural contents may

also be improved upon by being further categorized, to include the traditional elements.

The present study is itself not exhaustive. It has not gone beyond two Primary One textbooks produced by the same

publishers, whereas there are hundreds of reputable publishers in Nigeria who have also produced basal materials. Even

textbooks by one publisher may vary the ways they address cultural content across the different classes of the Primary

School, up to the Junior Secondary School which is now regarded as the Upper Basic Level (Federal Republic of

Nigeria, 2007). Thus, further investigation is needed to redress these and other lapses of the study.

APPENDIX: TEXTS INVESTIGATED

Macauley, J., B. Oderinde, F. Badaki, B. Somoye, N Hawkes & D. Dallas (2007).Nigeria.

Primary English: Pupils’ Book 1 (UBE Edition). Longman Nigeria PLC.

Ekpa, A., F. Vanessa, C. Minkley, F. Moh, D. Utsalo & G. Ikpeme (2008) Advantage.

English: Pupils’ Book 1. Essex, England: Pearson Education Limited.

REFERENCES

[1] Akintunde, Stephen A. (1993).Book development and national orientation. Literacy and Reading in Nigeria, 6, 387-395.

[2] Courtney, Richard. (1974). Play, drama(s) though: The intellectual background to drama in Education (Third edition). London:

Cassell, pp. 137-141.

[3] Emenyonu, P. T. (1993). Adaptation and production materials for new literates. Literacy and Reading in Nigeria, 6, 397-408.

[4] Federal Republic of Nigeria. (2007). National policy on education. Lagos: Government Press.

[5] Holly, D. (1990). The unspoken curriculum or how language teaching carries cultural and ideological messages. In B. Harrison

(Ed.), Culture and the Language classroom (pp. 11-19). Hong Kong: Modern English Publication and the British Council.

[6] Kramsch, C. (1998). Language and Culture. Oxford University Press.

[7] Kilickaya, Ferit. (2004). Guidelines to evaluate cultural contents in textbooks. The Internet TESL Journal, (12).

http://itesl.org/techniques kilickaya-cultural content.

[8] Miekley, Joshua. (2005).ESL Textbook Evaluation Checklist. The Money Matrix, 5(2).

[9] Obafemi, Olu (Ed.) . (1994). Drama: its nature and purpose. In New Introduction to Language (pp.85 - 99). Ibadan: Y-books.

© 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER

JOURNAL OF LANGUAGE TEACHING AND RESEARCH 661

[10] Olajide S.B. (1995). The role of teacher in improving the learning of English in Nigeria primary school. Ilorin Journal of

Education (a publication of Faculty of Education, University of Ilorin, Ilorin), 16, 59-67.

[11] Olajide S.B. (2004). An evaluation of Longman’s “New Practical English”. Nigerian Journal of Educational Foundations, 6

(1), 92-100. Also available on http://www.unilorin.edu.ng/publications/edu/nijef/2003

[12] Olajide S.B. (2009). Types of reading. In Alabi, V. A. & Batunde, S. T. (Eds.), The Use of English in Higher Education (pp.43

– 52). Ilorin: General Studies Division, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria.

Stephen Billy Olajide was born in Olla, Kwara State, Nigeria in March, 1956. He earned B. A. (Honours) Degree in Linguistics

and Language Arts from the University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria in 1982. He later attended the University of Ilorin, Ilorin, also in

Nigeria where he obtained PGDE, M. Ed. and Ph. D. in English Language Education.

After the mandatory National Service in 1983, he worked at Idofian Grammar School, Idofian Nigeria as a teacher of English

Language and Literature-in-English till 1992 when he joined the Kwara State College of Education, Ilorin, Nigeria as Lecturer in

English in the Department of English. He became the Head of Department of General Studies of the college in 1994, a position he

occupied till 2002 when he was employed at the University of Ilorin as Lecturer in English Education and Applied Linguistics in the

Department of Curriculum studies and Educational Technology.

He is currently a Senior Lecturer in English Education and Applied Linguistics at the Department of Arts and Social Sciences

Education, Faculty of Education, University of Ilorin. Billy Olajide‘s research interests include the Teaching of English Studies,

Curriculum Panning and Development, Reading and Literacy; he has published extensively in local and international learned outlets

on these areas. He has published a textbook- ‘’Essentials of communicative writing in English’’ and contributed chapters in

numerous joint scholarly books. His most recent work is an article titled ‘’Folklore and culture as literacy resources for national

emancipation’’ published in International Education Studies (A Publication of the Canadian Center for Science and Education), 3(2)

of May, 2010. He was at the 5th Pan-African Reading for All Conference held at the University of Ghana, Legon, Accra, Ghana, 6th

– 10th August, 2007 where he presented a paper.

Stephen Billy Olajide is the Sub-Dean of the Faculty (of Education) and immediate past Co-ordinator of the ‘’Use of English’’, a

Programme for all fresh undergraduate students at the University of IIorin, Nigeria.

© 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER

You might also like

- Sociolinguistics and Language TeachingFrom EverandSociolinguistics and Language TeachingRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Cultural Mirrors: Materials and Methods in English As A Foreign LanguageDocument7 pagesCultural Mirrors: Materials and Methods in English As A Foreign LanguageInternational Journal of Basic and Applied ScienceNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Including Culture in e 0238eeccDocument13 pagesThe Importance of Including Culture in e 0238eeccFabian KoLNo ratings yet

- Group 3 - Assignment 7 - Academic Writing RevDocument4 pagesGroup 3 - Assignment 7 - Academic Writing RevLilis nurhikmahNo ratings yet

- English Language Textbooks in EFL EducatDocument17 pagesEnglish Language Textbooks in EFL Educatnisan özNo ratings yet

- Research Methodolgy: Semiotic Analysis Research PaperDocument11 pagesResearch Methodolgy: Semiotic Analysis Research PaperJoiya KhanNo ratings yet

- ELT and CultureDocument5 pagesELT and CultureLeymi PichardoNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Including Culture in EFL Teaching: VOLUME 1, NUMBER 1, FEBRUARI 2011: 44-56Document13 pagesThe Importance of Including Culture in EFL Teaching: VOLUME 1, NUMBER 1, FEBRUARI 2011: 44-56asad modawiNo ratings yet

- The Role of Culture Identity in Teaching and Learning of English As A Foreign LanguageDocument16 pagesThe Role of Culture Identity in Teaching and Learning of English As A Foreign LanguageFatemeh NajiyanNo ratings yet

- 5791-Article Text-15866-1-10-20220109Document10 pages5791-Article Text-15866-1-10-20220109BayuRedgiantchildNo ratings yet

- Exploring Cultural Content of Three PromDocument13 pagesExploring Cultural Content of Three Promトラ グエンNo ratings yet

- Fostering The Learning Through Intercultural AwarenessDocument7 pagesFostering The Learning Through Intercultural Awareness77sophia777No ratings yet

- Using Short Stories in English Language Teaching at Upper-Intermediate LevelDocument11 pagesUsing Short Stories in English Language Teaching at Upper-Intermediate Levelİsmail Zeki Dikici0% (2)

- 1023 3984 1 PBHHDocument12 pages1023 3984 1 PBHHنجمةالنهارNo ratings yet

- Critical AnalysisDocument4 pagesCritical AnalysisnhajmcknightNo ratings yet

- Culture: What To Teach and How To Teach It in An EFL ClassDocument6 pagesCulture: What To Teach and How To Teach It in An EFL ClassstrikeailieNo ratings yet

- 1230 3577 1 SMDocument16 pages1230 3577 1 SMMarzalia RaisaNo ratings yet

- Cultural Elements in Malaysian English Language Textbooks - My - CaseltDocument22 pagesCultural Elements in Malaysian English Language Textbooks - My - CaseltNataliaJohnNo ratings yet

- 1707-Article Text-3671-1-2-20211130Document14 pages1707-Article Text-3671-1-2-20211130Teteng SyaidNo ratings yet

- The Role of Culture in Teaching and Learning of English As A Foreign LanguageDocument14 pagesThe Role of Culture in Teaching and Learning of English As A Foreign LanguageKhoa NguyenNo ratings yet

- RoughDocument21 pagesRoughMuhammad Babar QureshiNo ratings yet

- 1 SMDocument12 pages1 SMLisdaNo ratings yet

- Temario de Oposiciones De: InglésDocument25 pagesTemario de Oposiciones De: Inglésvanesa_duque_3100% (1)

- Textbooks Analysis: Analyzing English As A Foreign Language (Efl) Textbooks From The Perspective of Indonesian Culture Devy Angga GunantarDocument10 pagesTextbooks Analysis: Analyzing English As A Foreign Language (Efl) Textbooks From The Perspective of Indonesian Culture Devy Angga GunantarDefita AnggrainiNo ratings yet

- FleetDocument30 pagesFleetTatjana BozinovskaNo ratings yet

- Presented By:: Integrating Culture Into The Efl InstructionDocument12 pagesPresented By:: Integrating Culture Into The Efl InstructionAlffa RizNo ratings yet

- ELT Volume 12 Issue 26 Pages 145-173Document29 pagesELT Volume 12 Issue 26 Pages 145-173Abolfazl MNo ratings yet

- 4 Research Proposal FinalDocument25 pages4 Research Proposal Finalapi-370360557No ratings yet

- Role of (Local) Culture in English Language TeachingDocument7 pagesRole of (Local) Culture in English Language TeachingKumar Narayan ShresthaNo ratings yet

- Chintya Ari Amanda PutriDocument8 pagesChintya Ari Amanda PutriCahyani PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Theroleofcultureinelt RahimuddinDocument20 pagesTheroleofcultureinelt RahimuddinhalisgozpinarNo ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of Cultural Content in EFL Materials-A ReimannDocument17 pagesA Critical Analysis of Cultural Content in EFL Materials-A ReimannJasmina PantićNo ratings yet

- Language As A Social Mirror of EthnicityDocument99 pagesLanguage As A Social Mirror of Ethnicityiklima1502No ratings yet

- Jackie F. K. Lee and Xinghong LiDocument20 pagesJackie F. K. Lee and Xinghong Liarifinnur21No ratings yet

- Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Lviv National Ivan Franko UniversityDocument54 pagesMinistry of Education and Science of Ukraine Lviv National Ivan Franko UniversityNathalie KhanenkoNo ratings yet

- MaterialDocument58 pagesMaterialhernanariza89No ratings yet

- Power Point SlidesDocument24 pagesPower Point SlidesAleynaNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning CultureDocument6 pagesTeaching and Learning CultureAngelds100% (1)

- Western Culture and The Teaching of English As An International LanguageDocument8 pagesWestern Culture and The Teaching of English As An International LanguageLưu Cẩm Hà100% (2)

- Book Review Lin & Martin Decolonization 2Document2 pagesBook Review Lin & Martin Decolonization 2Dikesh MaharjanNo ratings yet

- InterculturalDocument5 pagesInterculturalcristian arizaNo ratings yet

- Cross Cultural Context PDFDocument9 pagesCross Cultural Context PDFRhobie La KyiassNo ratings yet

- 4315 9326 1 SMDocument7 pages4315 9326 1 SMViolet BeaudelaireNo ratings yet

- (Inter) Cultural Communication in Japanese Language TextbooksDocument12 pages(Inter) Cultural Communication in Japanese Language TextbooksMagda CNo ratings yet

- Budi Hermawan Final 49-61 PDFDocument13 pagesBudi Hermawan Final 49-61 PDFHajar Aishah AzkahNo ratings yet

- Teaching Culture Through Reading Literature in English Language TeachingDocument19 pagesTeaching Culture Through Reading Literature in English Language Teachinghgol0005No ratings yet

- The Importance of Teaching Culture in EFL ClassroomsDocument7 pagesThe Importance of Teaching Culture in EFL ClassroomsAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- E-Learning and The Development of Intercultural Competence: Meei-Ling Liaw National Taichung UniversityDocument16 pagesE-Learning and The Development of Intercultural Competence: Meei-Ling Liaw National Taichung Universityapi-27788847No ratings yet

- LLLLDocument2 pagesLLLLRafael Brix AmutanNo ratings yet

- ED522274Document25 pagesED522274Trang NguyenNo ratings yet

- InterculturalDocument5 pagesInterculturalcristian arizaNo ratings yet

- Tesol ReportingDocument6 pagesTesol ReportingYsbzjeubzjwjNo ratings yet

- 606 Paper-1Document24 pages606 Paper-1api-609553028No ratings yet

- Fichamento - Corbett - An Intercultural Approach To English Language TeachingDocument8 pagesFichamento - Corbett - An Intercultural Approach To English Language TeachingtatianypertelNo ratings yet

- Reflections On Selected Readings, After CorrectionDocument7 pagesReflections On Selected Readings, After CorrectionLee CrystalNo ratings yet

- Therepresentationofmulticulturalvaluesinthe Indonesian Ministryof Educationand Culture Endorsed EFLtextbookacriticaldiscourseanalysisDocument16 pagesTherepresentationofmulticulturalvaluesinthe Indonesian Ministryof Educationand Culture Endorsed EFLtextbookacriticaldiscourseanalysisRadja SilalahiNo ratings yet

- Analyzing Moran's Dimensions of Culture in An English Conversational Course at UCRDocument30 pagesAnalyzing Moran's Dimensions of Culture in An English Conversational Course at UCRUn KnownNo ratings yet

- Factors Militating Against Proper Teaching and Learning of Literature in English in Senior Secondary SchoolsDocument7 pagesFactors Militating Against Proper Teaching and Learning of Literature in English in Senior Secondary SchoolsDaniel ObasiNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1 Cultural AwarenessDocument9 pagesCHAPTER 1 Cultural AwarenessLutfan LaNo ratings yet

- Pius Oyeniran Abioje Curriculum VitaeDocument10 pagesPius Oyeniran Abioje Curriculum VitaePius Abioje100% (1)

- Phillips Hmo Hospital List (National) - Apr 2021Document290 pagesPhillips Hmo Hospital List (National) - Apr 2021Onyekachi Jack0% (1)

- The Location of Petrol Service Stations and The Physical Planning Implication in IlorinDocument66 pagesThe Location of Petrol Service Stations and The Physical Planning Implication in IlorinTolani100% (1)

- Oga Shero ProjectDocument48 pagesOga Shero ProjectQozeem OlamilekanNo ratings yet

- Nonsuch Hospital List Providers Updated Hospital ListDocument12 pagesNonsuch Hospital List Providers Updated Hospital ListagbaipissNo ratings yet

- Al Hikmah HomeworkDocument8 pagesAl Hikmah Homeworkiuoqhmwlf100% (1)

- Use of Social Media Among The Market Women in Ilorin Metropolis, Kwara State, NigeriaDocument6 pagesUse of Social Media Among The Market Women in Ilorin Metropolis, Kwara State, NigeriaIfabiyi John OluwaseunNo ratings yet

- EC ProvidersDocument12 pagesEC Providersademola rufaiNo ratings yet

- Ade CV1Document4 pagesAde CV1Albert Adewale AdebayoNo ratings yet

- JEDA 22-1-2014 Contributors & Table of Contents XDocument9 pagesJEDA 22-1-2014 Contributors & Table of Contents XemyyyxNo ratings yet

- List of Approved Schools With Admission QuotaDocument21 pagesList of Approved Schools With Admission QuotaAdegboye Adedayo100% (1)

- Sunday Samson Opeyemi CVDocument2 pagesSunday Samson Opeyemi CVToluwaseNo ratings yet

- HAUWA'S CV DegreeDocument2 pagesHAUWA'S CV DegreeGaruba Muh'd Jamiu KayodeNo ratings yet

- Vetting GuidelinesDocument17 pagesVetting GuidelinesAyomikun OgunkanmiNo ratings yet

- Accredited Institutions PDFDocument7 pagesAccredited Institutions PDF1048558No ratings yet

- 2017 Budget FINALDocument159 pages2017 Budget FINALAminu IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Inter-Agency Cooperation and Airport Security: A Study of Murtala Mohammed International AirportDocument9 pagesInter-Agency Cooperation and Airport Security: A Study of Murtala Mohammed International AirportAdediran DolapoNo ratings yet

- Ilorin Emirate - WikipediaDocument7 pagesIlorin Emirate - Wikipediajaaniyi1996No ratings yet

- Dami CVDocument2 pagesDami CVobisesanolumide2020No ratings yet

- Ahmed Isiaka 1Document3 pagesAhmed Isiaka 1kennyNo ratings yet

- 7 Sanusi StreetDocument2 pages7 Sanusi StreetkaysafNo ratings yet

- Shs 2005 GraduateDocument28 pagesShs 2005 GraduateAlabi SalihuNo ratings yet

- Historical Development of Muslim Education in Yoruba Land, Southwest Nigeria.Document9 pagesHistorical Development of Muslim Education in Yoruba Land, Southwest Nigeria.Tunde OgunbadoNo ratings yet

- Summary Works NEW 2 RevitionDocument41 pagesSummary Works NEW 2 RevitionnaconnetNo ratings yet

- Persianas Group Profile Sep2011Document21 pagesPersianas Group Profile Sep2011paulyaacoubNo ratings yet

- Mentorship and Inspiration 08 Dec 2018-3-29 PMDocument30 pagesMentorship and Inspiration 08 Dec 2018-3-29 PMlax mediaNo ratings yet

- Muslims of Kwara State: A Survey: NRN B P N - 3Document11 pagesMuslims of Kwara State: A Survey: NRN B P N - 3muhammad raji muhyideenNo ratings yet

- Siwes Letter 2023Document2 pagesSiwes Letter 2023RUQOYYAH SULYMANNo ratings yet

- Erinmope at A GlanceDocument8 pagesErinmope at A Glancejoshua4lifeNo ratings yet

- Commercial Classic Report: Federal Mortgage Bank of Nigeria W-0001549417/2018 20-Feb-2018Document5 pagesCommercial Classic Report: Federal Mortgage Bank of Nigeria W-0001549417/2018 20-Feb-2018Boyi EnebinelsonNo ratings yet