Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Remember Me To The Motherland

Remember Me To The Motherland

Uploaded by

Joseph TripicianCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Starman: The Truth Behind the Legend of Yuri GagarinFrom EverandStarman: The Truth Behind the Legend of Yuri GagarinRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (34)

- Alfred Loedding & The Great Flying Saucer Wave of 1947 - Michael D Connors, Wendy A Hall PDFDocument138 pagesAlfred Loedding & The Great Flying Saucer Wave of 1947 - Michael D Connors, Wendy A Hall PDFTerra Mistica100% (1)

- The Early Science Fiction of Philip K. DickFrom EverandThe Early Science Fiction of Philip K. DickRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Ufos & Alien Contact - Two Centuries of MysteryDocument571 pagesUfos & Alien Contact - Two Centuries of MysteryVideos googledriveNo ratings yet

- Ufo SecretsDocument97 pagesUfo SecretsZaxkandil100% (3)

- Astronaut SpeakDocument7 pagesAstronaut SpeakNargis BanoNo ratings yet

- Plumbing Bank 1 PDFDocument22 pagesPlumbing Bank 1 PDFJoemarbert YapNo ratings yet

- DAWBEE DVB-S2 Receiver Upgrade Setup GuideDocument23 pagesDAWBEE DVB-S2 Receiver Upgrade Setup GuideronfleurNo ratings yet

- The Ufo Files Russian RoswellDocument6 pagesThe Ufo Files Russian Roswelldickeazy100% (3)

- The Cosmonaut Who Couldn’t Stop Smiling: The Life and Legend of Yuri GagarinFrom EverandThe Cosmonaut Who Couldn’t Stop Smiling: The Life and Legend of Yuri GagarinRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- "Live from Cape Canaveral": Covering the Space Race, from Sputnik to TodayFrom Everand"Live from Cape Canaveral": Covering the Space Race, from Sputnik to TodayRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (30)

- LIFE The Great Space Race: How the U.S. Beat the Russians to the MoonFrom EverandLIFE The Great Space Race: How the U.S. Beat the Russians to the MoonNo ratings yet

- MUFON Minnesota Journal Issue #143 May/June 2010Document16 pagesMUFON Minnesota Journal Issue #143 May/June 2010shangrilolNo ratings yet

- Bruce Sterling - Catscan 14 - Memories of The Space AgeDocument3 pagesBruce Sterling - Catscan 14 - Memories of The Space AgeJB1967No ratings yet

- Mad or Bad Part 2 Mad or Bad Part 2 Mad or Bad Part 2 Mad or Bad Part 2 by J.Arthur by J.Arthur by J.Arthur by J.ArthurDocument26 pagesMad or Bad Part 2 Mad or Bad Part 2 Mad or Bad Part 2 Mad or Bad Part 2 by J.Arthur by J.Arthur by J.Arthur by J.ArthurRagaa NoorNo ratings yet

- Season of the Witch: An EVENT Group Thriller, #14From EverandSeason of the Witch: An EVENT Group Thriller, #14Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Space Science Fiction Super Pack: With linked Table of ContentsFrom EverandSpace Science Fiction Super Pack: With linked Table of ContentsNo ratings yet

- (Extraterrestrial Life) Jim Whiting - UFOs-ReferencePoint Press (2012)Document80 pages(Extraterrestrial Life) Jim Whiting - UFOs-ReferencePoint Press (2012)josh100% (1)

- Space Race: The Battle to Rule the Heavens (text only edition)From EverandSpace Race: The Battle to Rule the Heavens (text only edition)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (44)

- The Close Encounters Man: How One Man Made the World Believe in UFOsFrom EverandThe Close Encounters Man: How One Man Made the World Believe in UFOsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (8)

- List of The Outer Limits (1963 TV Series) EpisodesDocument10 pagesList of The Outer Limits (1963 TV Series) EpisodesGerardo DíazNo ratings yet

- From Gagarin To Armageddon - Soviet-American Relations in The Cold War Space EpicDocument8 pagesFrom Gagarin To Armageddon - Soviet-American Relations in The Cold War Space EpicSimone OdinoNo ratings yet

- Dark Skies BibleDocument63 pagesDark Skies Bibledluker2pi1256No ratings yet

- UFO Contact From Angels in Starships (Giorgio Dibitonto [Dibitonto, Giorgio]) (z-lib.org)Document211 pagesUFO Contact From Angels in Starships (Giorgio Dibitonto [Dibitonto, Giorgio]) (z-lib.org)jaesennNo ratings yet

- Ufo Sightings by Astronauts Incredible DeclarationsDocument20 pagesUfo Sightings by Astronauts Incredible DeclarationsAuto68100% (1)

- 7 Strange Tales From The Wild WestDocument7 pages7 Strange Tales From The Wild WestDrVulcanNo ratings yet

- Eisnehower George Bush SR and The UFO'sDocument39 pagesEisnehower George Bush SR and The UFO'sAva100% (2)

- Charles BERLITZ & William L. MOORE The Roswell IncidentDocument57 pagesCharles BERLITZ & William L. MOORE The Roswell IncidentPauloMacedNo ratings yet

- Losing LaikaDocument395 pagesLosing LaikaGTA GAMERNo ratings yet

- Subspace Chatter: A A A A ADocument32 pagesSubspace Chatter: A A A A Aspake7No ratings yet

- The Journal of Borderland Research 1973-01 & 02 (No 35-36)Document36 pagesThe Journal of Borderland Research 1973-01 & 02 (No 35-36)Esa Juhani Ruoho100% (3)

- Alien Magic - William Hamilton IIIDocument179 pagesAlien Magic - William Hamilton IIICarlos Rodriguez100% (8)

- 10 Times UFO Caught On CameraDocument3 pages10 Times UFO Caught On CameraAbdul wasayNo ratings yet

- Summary: The Day After Roswell: Philip Corso (Illustrated Study Aid by Scott Campbell)From EverandSummary: The Day After Roswell: Philip Corso (Illustrated Study Aid by Scott Campbell)No ratings yet

- Flash Gordon On The Planet Mongo (1934) BLBDocument316 pagesFlash Gordon On The Planet Mongo (1934) BLBAlexandre FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Conspiracy TimelineDocument128 pagesConspiracy TimelineMichael Petersen100% (1)

- Nazi Moon BaseDocument5 pagesNazi Moon Baseomkar100% (1)

- Node Place Analysis HubtropolisDocument9 pagesNode Place Analysis Hubtropolisrahel0% (1)

- F3 - Checklist - HDPE Butt Fusion WeldingDocument1 pageF3 - Checklist - HDPE Butt Fusion WeldingQasim Saeed KhanNo ratings yet

- 1002 PDFDocument6 pages1002 PDFali.jahayaNo ratings yet

- 11 1 2019 PDFDocument2 pages11 1 2019 PDFdkNo ratings yet

- Design of Machine Element ProblemsDocument2 pagesDesign of Machine Element Problemsmaxpayne5550% (1)

- CorporateDocument26 pagesCorporatesainath93No ratings yet

- Dear Hiring ManagerDocument1 pageDear Hiring ManagerYazid AmraniNo ratings yet

- Angular MotionDocument7 pagesAngular MotionArslan AslamNo ratings yet

- Reg ModsDocument137 pagesReg ModsMANOJ KUMARNo ratings yet

- Tirupati Polyflex (Catalog)Document12 pagesTirupati Polyflex (Catalog)thingsneededforNo ratings yet

- WinUSB Tutorial 5Document12 pagesWinUSB Tutorial 5quim758No ratings yet

- Solution: Homework#1Document7 pagesSolution: Homework#1Marlon BlasaNo ratings yet

- Removal Organic Compound of Domestic Waste Waters Containing Heavy Metals Using Mendong, Fimbrystilis GlobulosaDocument2 pagesRemoval Organic Compound of Domestic Waste Waters Containing Heavy Metals Using Mendong, Fimbrystilis Globulosaapi-3736766No ratings yet

- Car PricesDocument6 pagesCar PricesSampath DayarathneNo ratings yet

- Preventive Maintenance SimDocument4 pagesPreventive Maintenance SimBBKFP Training CenterNo ratings yet

- SWOT AnalysisDocument15 pagesSWOT AnalysisobnI_100% (2)

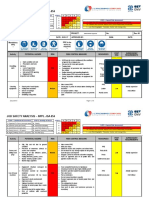

- JSA-054 Crossing WorksDocument6 pagesJSA-054 Crossing WorksMajdiSahnounNo ratings yet

- Govt Approves National Policy On ITDocument5 pagesGovt Approves National Policy On ITmax_dcostaNo ratings yet

- Nitrogen Cylinder 84L: SNS IG-100 Fire Suppression SystemDocument3 pagesNitrogen Cylinder 84L: SNS IG-100 Fire Suppression SystemNguyễn Minh ThiệuNo ratings yet

- ISO-TC 309-WG 2 - N68 - Limited Revision To ISO 37001-2016 - Ballot ApprovalDocument10 pagesISO-TC 309-WG 2 - N68 - Limited Revision To ISO 37001-2016 - Ballot ApprovalBNo ratings yet

- Data ONTAP 81 Cluster Peering Express Guide ForDocument29 pagesData ONTAP 81 Cluster Peering Express Guide ForKamlesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Triplex Plunger Pump Preventive Maintenance GuidelinesDocument1 pageTriplex Plunger Pump Preventive Maintenance GuidelinesthunderNo ratings yet

- Waldorf Zarenbourg ManualDocument22 pagesWaldorf Zarenbourg ManualGiacomo FerrariNo ratings yet

- TN482Document9 pagesTN482syed muffassirNo ratings yet

- Display 090920122425 Phpapp01 PDFDocument37 pagesDisplay 090920122425 Phpapp01 PDFNihar PandaNo ratings yet

- Seleção FANCOIL SALA 1 Ou 2Document7 pagesSeleção FANCOIL SALA 1 Ou 2Gustavo RomeroNo ratings yet

- Tabnabbing Attack Method Penetration Testing LabDocument6 pagesTabnabbing Attack Method Penetration Testing LabEugenia CascoNo ratings yet

- Gantry Cranes PDFDocument2 pagesGantry Cranes PDFgrupa2904No ratings yet

Remember Me To The Motherland

Remember Me To The Motherland

Uploaded by

Joseph TripicianOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Remember Me To The Motherland

Remember Me To The Motherland

Uploaded by

Joseph TripicianCopyright:

Available Formats

"REMEMBER ME TO THE MOTHERLAND"

By Joe Tripician

When Igor stepped inside the capsule, he had two thoughts: the cramped tin can would

either become his victory chariot, or his funeral casket. He hadn't counted on a third

option -- that the R-7-based launched Vostok, the glory of the Soviet space program, the

fear of the capitalist world, and the envy of the rest -- would become Igor's personal time

machine.

By 1964, the Soviets were shooting off more rockets than a Chinese teenager on

New Year's, yet the Communist-controlled press reported only a fraction of them. It was

not just for military secrecy that they were tight-lipped. A great many launches were

failures, and some of those held human cargo.

It takes a certain person to be a Cosmonaut. Once you pass through the security

clearance, training, the physical and mental exams, only then does the political selection

begin. But Igor Ashirov was no cousin to any Politburo member, or drinking buddy of

Krushev; Igor was the classic farm boy with a dream. Unlike other country bumpkins,

this one was a natural cosmonaut. And his loyalty was beyond reproach -- or reason. His

superiors had told him that the prior launch, the one that shot his friend Nicoli into space,

had never left the launch pad, had not hurled Nicoli's body into orbit. Cosmonaut Nicoli

Grachev, Igor was told in a hastily-arranged briefing, had never been scheduled to fly,

had never actually been a cosmonaut, had in fact never even existed. Igor thought that

this would come as news to his parents who had pinned so much hope on their squat,

stocky red-cheeked son, who loved rockets more than his pet dog Pchelka, whom Nicoli

Copyright 2002 Joe Tripician

had bravely sacrificed to the program, who died like him in a fiery ball in a botched

reentry.

Sergei Korolev, their leader and Chief Designer, remembered the two dogs --

Pchelka and his furry palymate Mushka -- often in his talks to the corps, more than he

remembered Nicoli Grachev, whose face was thereafter permanently erased from all

official photographs. Failures were never acknowledged within the corps, as if the shame

of them would collectively weigh down the unit, and with it the Soviet space program,

the entire military, and indeed the very Motherland herself.

Somehow, thought Igor, only the gray-haired pot-bellied Politburo would manage

to survive, living out the Republic's last days feeding on shashliki in their countryside

villas. So rather than ruin the land he loved, Igor and his comrades never spoke of Nicoli,

never traded gossip, even covertly. Did the courage that made these men born heroes

falter when it came to the KGB? Or did the common sense that failed to stop them from

sitting inside a tin sphere on top of over 15,000 kilograms of liquid oxygen and kerosene

finally surface when faced with the more immediate danger of being "disappeared"? You

and your family being erased overnight, like the photo of Nicoli and those two miserable

dogs.

These thoughts plagued Igor as he squeezed his small frame inside the Vostok

capsule. "Remember me to the Motherland," he told Feydor, as the young engineer

bolted the iron-cast door.

When the R-7 ICBM lifted, its thrust powerful enough to flatten the beloved

country village of his birth, the image of Pchelka's burnt body jolted into Igor's brain, and

he flushed in embarrassment. "How selfish," he thought. "I carry the glory of socialism

and the good will of the people with me and still my brain returns to poor Pchelka."

Copyright 2002 Joe Tripician 2

The ride up was as rough as Yuri and the others had described, but Igor was still

unprepared for the battening his body took. He traveled upward, reaching for space,

fighting against earth's gravity and the heaviness of the already sorrowful longing for his

family. Dear Leva, his wife of two years, by the stove, her moist hair sticking to her

joyful face, and sweet Mamma, secretly crying for her only boy, the strong shy

cosmonaut.

His thoughts slowed down as the capsule finally broke free of the atmosphere and

glided into orbit, the stars now his living companions, so cold; the earth, his wife, his

Mamma, all lonely, so cold, nestled below under the milky air-white blanket, so very

cold, something wrong, his head lighter than space, voices crackling, but cold and

peaceful, gauges blinking madly, and the deep dark quiet of the slow, slow cold…

* * *

Seaman Howard G. Jamison was sprawled on the deck of the USS Port Royal diligently

working on his tan. Just 48 hours 'till shore leave, and he'd be back in the arms of Anne -

- or Hannah, then maybe Vickie -- and, if he had time, Toni. Why do guys ever get

married, he wondered. It's a big, bad beautiful world of babes out there, and he was in no

rush.

"What the-- " Jamison raised his head and peered at the shooting star, or whatever

the hell it was that just dropped from out of god-damn-nowhere, like a bullet shot by God

into the drink.

It was an ugly cast-iron cannonball that the crew fished out at the urgent

insistence of their Commander Bruce Clark and the ever-present agency men. As soon as

Copyright 2002 Joe Tripician 3

it hit the deck Clark ordered all non-essential personnel down below. Ever since the stern

National Security Agency men boarded at an unannounced stopover in San Diego, the

crew couldn't even count the night stars without asking permission. Well, maybe by the

time the agency men tore it apart, Jamison muttered, they'd make shore and he'd have

enough time to spend with Chrissie, the foxy brunette who said he looked like Leonardo

DiCaprio.

* * *

Cosmonaut Igor Ashirov never saw the rapid turmoil below, out of reach of his frozen

fingers, and beyond the will of his loyal comrades. The world would never get to marvel

or tremble beneath Battlestar Krushev, his ex-leader's dream of a giant space station; and

although Brezhnev was no fan of the space program, he continued to sanction it with a

suspicious neglect that left Igor stranded when his biomedical vitals no longer transmitted

his existence to the command center.

He became non-personed, just like Nicoli Grachev, his friend and brave

cosmonaut who disappeared from history when the failure of his flight would have

shamed the motherland. No statue or plaque would memorialize Igor Ashirov, and so his

comrades kept his memory alive in their hearts, and never through their lips.

Death becomes fluid the moment we challenge it, tricking us into beliefs as wild

and varied as our religions. Humans with the courage to face death may survive a small

reprieve, but ultimately lose. For thirty-eight years Igor and death faced each other,

locked in a celestial Mexican standoff. The cold of space, which took too many of his

fellow cosmonauts, instead preserved Igor cryogenically. The freak occurrence of a

Copyright 2002 Joe Tripician 4

sudden leak in the Vostok capsule at a critical point during its entry into space essentially

flash-froze Igor inside his space suit before the danger of a rapid depressurization caused

his fluids to boil him from the inside. Miraculously, no damage was done to a single cell

of his body. In fact, when the NSA men pried him out of the capsule for the first time in

almost half a century, they remarked how very young he looked and how superbly space

had preserved him.

Back in 2002, when a CIA operative in Armenia passed purloined information

from a retired KGB officer from Moscow, it made its way to a Russian mobster in

Brighton Beach, and from there to a Columbian drug runner in Bogotá who was

intercepted by the FBI in Lima, Peru. In a rare occurrence of inter-agency cooperation,

the FBI passed the files on to the CIA who enlisted the NSA in tracking Igor's long-

forgotten orbiting capsule.

Long-since erased from the files of the Russians, and living only in the faint

memory of a few, Igor's legacy now belonged solely to the Americans, his fate to be

decided by the country of his once former enemy.

The decision to bring it down was solely the U.S. President's, who saw in Igor's

saga a faint reminder of his own lost childhood, and a publicity bonanza of the century.

So, Igor was knocked out of orbit by a strategically tweaked spy satellite during

one of its brief passes. The hit was calculated to send the capsule back to earth, shield

first, and into the watery arms of the Pacific.

While Jamison was below reading Penthouse, the agency men were wrapping

Igor's body in aluminum, like a weathered turkey. The underground lab at National

Institutes of Health was a bunker of high-tech marvels where Igor received better care

than at any of his medical visits in the Moscow Space Center.

Copyright 2002 Joe Tripician 5

From their vast library of secrets, the technicians at NIH employed a nano-bot

self-healing system for reviving the cryogenically frozen. Their first human test failed

and the subject became, following the tradition of their Soviet counterparts, non-

personed. In spite of, or because of, this failure the agency's program was given all-out

carte blanche: a bio-medical Manhattan Project, the dark details of which have not been

disclosed. And so, on August 25, 2004, Igor Ashirov was revived.

During the long months, Igor's body responded slowly but well to his rebirth;

progressing from an infant's utter dependence, to a child's wondrous and frightened

curiosity, to a teenager's angst in stunning rapidity. No one knew whether he would

suddenly lapse into madness, become comatose, or sustain a massive heart failure

(although there was much unsanctioned office betting.) When the defrosted cosmonaut

regained use of his tongue, the long-bottled fear and pride also revived.

At first he could not accept the descriptions of his new world, but the abundance

of images from the last half-century finally convinced him. For Igor, the joint

cooperation between Russia and America in the International Space Station was more

heartening than one would think.

"Battlestar Krushev finally lives!" he shouted, leaping from the examination table

and landing on his face when his long-unused legs gave beneath him.

Henry Sterling, his debriefer, a short and stylish man whose days at the Moscow

Embassy taught him to appreciate a finely tailored Italian suit, and a finely tuned female

Russian leg, picked him off the floor.

"Russia is also taking paying tourists up to the Station," Henry told Igor, after

helping him to a chair. He carefully observed Igor's reaction. Henry had mastered

enough psychological assessment and manipulation skills to impress his colleagues at

Copyright 2002 Joe Tripician 6

Langley, and to fight against encroaching retirement as he pushed 64. Igor had been

shown the TV newscasts of the fall of the Berlin wall, the Yelstin coup, and the battling

in Afghanistan and Chechnya; but none of those events so staggered him as the sight of

an American businessman and a ragged pop star paying $20 million each for a tourist

ticket to be lifted into space.

Up to now Igor had been eager to get back atop a rocket, almost as much as he

wanted to see his dear wife Leva. But this crass commercialization was more appropriate

for capitalist Americans than the stolid citizens of the Soviet Republic. For one fleeting

moment he considered abandoning his idea of re-entering space, but not even the

worldwide collapse of Socialism could pry him from that dream. The agency men,

however, had other ideas.

For weeks thereafter Igor kept mostly silent. He's sinking into a deep depression,

thought Henry, who often feared they'd lose him. But unlike other depressed patients,

Igor displayed unrelenting and continued curiosity in this brave new world, devouring

copies of newspapers, magazines, journals, and scientific reports. His one peculiarity,

clipping out all the ads and habitually burning them in a nighttime ceremony, made

Henry think twice.

With the smile of a practiced salesman, Henry approached Igor and offered him

the thing the Russian requested more than a second trip to space.

"Your health has improved remarkably," said Henry. "How would you like to

visit the Motherland?" Henry patted the cosmonaut's shoulders in a gesture meant to

communicate solidarity, but merely fizzled into an awkward insolence.

Igor caressed the tiny photograph of his now aged wife, smiling absently, "How

often I dreamt of my reunion with dear Leva, and yet…" Each time Igor spoke of her, his

Copyright 2002 Joe Tripician 7

eyes watered; mostly out of longing, but partly out of shame for his aversion to Leva's

wrinkled and weathered skin. One night, drunk on Henry's smuggled vodka, Igor had

confessed to wanting a divorce. But from the following day, and thereafter, Igor never

again mentioned it -- and Henry never mentioned Leva's second marriage.

Plans were made to carry Leva covertly to Virginia. The entire operation was

girded with security tighter than when Igor's capsule was fished out of the ocean. The

NSA insisted, because the President insisted. The President changed his tune about

publicizing "The Stalinstein Story", as it was unofficially known, for fear that the

Russians would never admit to abandoning their own cosmonaut and hence be forced to

retaliate by disclosing that unfortunate incident of the kidnapping of the Russian ballerina

by an overzealous CIA agent who thought she was a money-laundering mobster. I

worked too long on that deal to have it blowback, the President thought, must cramp the

lid down on it tighter.

* * *

At the bottom of the woman's hand-woven purse was the secret locket containing one of

the last remaining photographs of Igor Ashirov, the future cosmonaut as a child of three

proudly wearing his father's red star medal. Leva had not expected her daughter's

American cousin to contact her, nor did she ever expect she would be traveling to that

country, or even leaving her basement room in the outskirts of Moscow. She was only

thankful that this distant and unknown relative took pity on a twice-widowed peasant

whose first husband's pension never materialized.

Copyright 2002 Joe Tripician 8

The old woman was escorted into the empty, florescent-lit room. She sat at the

table, drank from a glass of water, and gazed at her silver-haired image on the wall-size

mirror. In the next room, darkened to prevent any one on the other side from seeing

inside, Igor and Henry peered back at Leva through the two-way mirror.

Although endlessly conditioned for this moment by Henry and his team of

psychologists, Igor was still unprepared for the sight of his dear Leva. Though just over

60, she looked like his grandmother. All that was missing was her knitting. No, here it

comes from that purse. Igor turned away from the mirror and lunged at Henry, grabbing

him in a headlock and pressing a steak knife against his neck.

"You did this to me! You devil-scum!"

The agents in the room drew their firearms

"Don't! Don't!" yelled Henry, commanding as much leadership in his high-

pitched voice as he could. When the agents stood their ground, Henry addressed his

captor. "Igor, listen carefully, you're feeling bad and acting violent."

"You're not my leaders, I will not obey you! You've taken me out of time, and I

will not obey!"

"Igor, please listen, for your sake, for your wife's sake. We've given you

everything you asked for. We did not do this to you. Your leaders in Moscow did this to

you. They left you up there to die, but we brought you down. We saved your life. We

brought your wife back, because you repeatedly asked us to. Just tell us what you want.

What do you want, Igor?"

* * *

Copyright 2002 Joe Tripician 9

The rocket lifted off the launch pad carrying NASA's latest passenger: a non-paying, non-

military, non-person named Igor, whose love of space overcame the heartbreak over his

home and his homeland. After closing his deal with the cooperative agency men, Igor

nestled comfortably inside the roomy capsule, and for the second time in his life felt the

sudden and rapid acceleration that signified celestial freedom. From this great height he

looked down on the planet, trying to remember another world where he shared with his

country the challenge of space without the moral pollution of commercialization. Before

the second orbit the capsule exploded suddenly in a glorious nova.

Alone again in the heavens, and unknown to the world, neither the Russians nor

the Americans would ever know the saga of this lost cosmonaut, though back on earth

you could briefly see, even without telescopes, the fiery outline of a flaming red star.

Copyright 2002 Joe Tripician 10

You might also like

- Starman: The Truth Behind the Legend of Yuri GagarinFrom EverandStarman: The Truth Behind the Legend of Yuri GagarinRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (34)

- Alfred Loedding & The Great Flying Saucer Wave of 1947 - Michael D Connors, Wendy A Hall PDFDocument138 pagesAlfred Loedding & The Great Flying Saucer Wave of 1947 - Michael D Connors, Wendy A Hall PDFTerra Mistica100% (1)

- The Early Science Fiction of Philip K. DickFrom EverandThe Early Science Fiction of Philip K. DickRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Ufos & Alien Contact - Two Centuries of MysteryDocument571 pagesUfos & Alien Contact - Two Centuries of MysteryVideos googledriveNo ratings yet

- Ufo SecretsDocument97 pagesUfo SecretsZaxkandil100% (3)

- Astronaut SpeakDocument7 pagesAstronaut SpeakNargis BanoNo ratings yet

- Plumbing Bank 1 PDFDocument22 pagesPlumbing Bank 1 PDFJoemarbert YapNo ratings yet

- DAWBEE DVB-S2 Receiver Upgrade Setup GuideDocument23 pagesDAWBEE DVB-S2 Receiver Upgrade Setup GuideronfleurNo ratings yet

- The Ufo Files Russian RoswellDocument6 pagesThe Ufo Files Russian Roswelldickeazy100% (3)

- The Cosmonaut Who Couldn’t Stop Smiling: The Life and Legend of Yuri GagarinFrom EverandThe Cosmonaut Who Couldn’t Stop Smiling: The Life and Legend of Yuri GagarinRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- "Live from Cape Canaveral": Covering the Space Race, from Sputnik to TodayFrom Everand"Live from Cape Canaveral": Covering the Space Race, from Sputnik to TodayRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (30)

- LIFE The Great Space Race: How the U.S. Beat the Russians to the MoonFrom EverandLIFE The Great Space Race: How the U.S. Beat the Russians to the MoonNo ratings yet

- MUFON Minnesota Journal Issue #143 May/June 2010Document16 pagesMUFON Minnesota Journal Issue #143 May/June 2010shangrilolNo ratings yet

- Bruce Sterling - Catscan 14 - Memories of The Space AgeDocument3 pagesBruce Sterling - Catscan 14 - Memories of The Space AgeJB1967No ratings yet

- Mad or Bad Part 2 Mad or Bad Part 2 Mad or Bad Part 2 Mad or Bad Part 2 by J.Arthur by J.Arthur by J.Arthur by J.ArthurDocument26 pagesMad or Bad Part 2 Mad or Bad Part 2 Mad or Bad Part 2 Mad or Bad Part 2 by J.Arthur by J.Arthur by J.Arthur by J.ArthurRagaa NoorNo ratings yet

- Season of the Witch: An EVENT Group Thriller, #14From EverandSeason of the Witch: An EVENT Group Thriller, #14Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Space Science Fiction Super Pack: With linked Table of ContentsFrom EverandSpace Science Fiction Super Pack: With linked Table of ContentsNo ratings yet

- (Extraterrestrial Life) Jim Whiting - UFOs-ReferencePoint Press (2012)Document80 pages(Extraterrestrial Life) Jim Whiting - UFOs-ReferencePoint Press (2012)josh100% (1)

- Space Race: The Battle to Rule the Heavens (text only edition)From EverandSpace Race: The Battle to Rule the Heavens (text only edition)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (44)

- The Close Encounters Man: How One Man Made the World Believe in UFOsFrom EverandThe Close Encounters Man: How One Man Made the World Believe in UFOsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (8)

- List of The Outer Limits (1963 TV Series) EpisodesDocument10 pagesList of The Outer Limits (1963 TV Series) EpisodesGerardo DíazNo ratings yet

- From Gagarin To Armageddon - Soviet-American Relations in The Cold War Space EpicDocument8 pagesFrom Gagarin To Armageddon - Soviet-American Relations in The Cold War Space EpicSimone OdinoNo ratings yet

- Dark Skies BibleDocument63 pagesDark Skies Bibledluker2pi1256No ratings yet

- UFO Contact From Angels in Starships (Giorgio Dibitonto [Dibitonto, Giorgio]) (z-lib.org)Document211 pagesUFO Contact From Angels in Starships (Giorgio Dibitonto [Dibitonto, Giorgio]) (z-lib.org)jaesennNo ratings yet

- Ufo Sightings by Astronauts Incredible DeclarationsDocument20 pagesUfo Sightings by Astronauts Incredible DeclarationsAuto68100% (1)

- 7 Strange Tales From The Wild WestDocument7 pages7 Strange Tales From The Wild WestDrVulcanNo ratings yet

- Eisnehower George Bush SR and The UFO'sDocument39 pagesEisnehower George Bush SR and The UFO'sAva100% (2)

- Charles BERLITZ & William L. MOORE The Roswell IncidentDocument57 pagesCharles BERLITZ & William L. MOORE The Roswell IncidentPauloMacedNo ratings yet

- Losing LaikaDocument395 pagesLosing LaikaGTA GAMERNo ratings yet

- Subspace Chatter: A A A A ADocument32 pagesSubspace Chatter: A A A A Aspake7No ratings yet

- The Journal of Borderland Research 1973-01 & 02 (No 35-36)Document36 pagesThe Journal of Borderland Research 1973-01 & 02 (No 35-36)Esa Juhani Ruoho100% (3)

- Alien Magic - William Hamilton IIIDocument179 pagesAlien Magic - William Hamilton IIICarlos Rodriguez100% (8)

- 10 Times UFO Caught On CameraDocument3 pages10 Times UFO Caught On CameraAbdul wasayNo ratings yet

- Summary: The Day After Roswell: Philip Corso (Illustrated Study Aid by Scott Campbell)From EverandSummary: The Day After Roswell: Philip Corso (Illustrated Study Aid by Scott Campbell)No ratings yet

- Flash Gordon On The Planet Mongo (1934) BLBDocument316 pagesFlash Gordon On The Planet Mongo (1934) BLBAlexandre FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Conspiracy TimelineDocument128 pagesConspiracy TimelineMichael Petersen100% (1)

- Nazi Moon BaseDocument5 pagesNazi Moon Baseomkar100% (1)

- Node Place Analysis HubtropolisDocument9 pagesNode Place Analysis Hubtropolisrahel0% (1)

- F3 - Checklist - HDPE Butt Fusion WeldingDocument1 pageF3 - Checklist - HDPE Butt Fusion WeldingQasim Saeed KhanNo ratings yet

- 1002 PDFDocument6 pages1002 PDFali.jahayaNo ratings yet

- 11 1 2019 PDFDocument2 pages11 1 2019 PDFdkNo ratings yet

- Design of Machine Element ProblemsDocument2 pagesDesign of Machine Element Problemsmaxpayne5550% (1)

- CorporateDocument26 pagesCorporatesainath93No ratings yet

- Dear Hiring ManagerDocument1 pageDear Hiring ManagerYazid AmraniNo ratings yet

- Angular MotionDocument7 pagesAngular MotionArslan AslamNo ratings yet

- Reg ModsDocument137 pagesReg ModsMANOJ KUMARNo ratings yet

- Tirupati Polyflex (Catalog)Document12 pagesTirupati Polyflex (Catalog)thingsneededforNo ratings yet

- WinUSB Tutorial 5Document12 pagesWinUSB Tutorial 5quim758No ratings yet

- Solution: Homework#1Document7 pagesSolution: Homework#1Marlon BlasaNo ratings yet

- Removal Organic Compound of Domestic Waste Waters Containing Heavy Metals Using Mendong, Fimbrystilis GlobulosaDocument2 pagesRemoval Organic Compound of Domestic Waste Waters Containing Heavy Metals Using Mendong, Fimbrystilis Globulosaapi-3736766No ratings yet

- Car PricesDocument6 pagesCar PricesSampath DayarathneNo ratings yet

- Preventive Maintenance SimDocument4 pagesPreventive Maintenance SimBBKFP Training CenterNo ratings yet

- SWOT AnalysisDocument15 pagesSWOT AnalysisobnI_100% (2)

- JSA-054 Crossing WorksDocument6 pagesJSA-054 Crossing WorksMajdiSahnounNo ratings yet

- Govt Approves National Policy On ITDocument5 pagesGovt Approves National Policy On ITmax_dcostaNo ratings yet

- Nitrogen Cylinder 84L: SNS IG-100 Fire Suppression SystemDocument3 pagesNitrogen Cylinder 84L: SNS IG-100 Fire Suppression SystemNguyễn Minh ThiệuNo ratings yet

- ISO-TC 309-WG 2 - N68 - Limited Revision To ISO 37001-2016 - Ballot ApprovalDocument10 pagesISO-TC 309-WG 2 - N68 - Limited Revision To ISO 37001-2016 - Ballot ApprovalBNo ratings yet

- Data ONTAP 81 Cluster Peering Express Guide ForDocument29 pagesData ONTAP 81 Cluster Peering Express Guide ForKamlesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Triplex Plunger Pump Preventive Maintenance GuidelinesDocument1 pageTriplex Plunger Pump Preventive Maintenance GuidelinesthunderNo ratings yet

- Waldorf Zarenbourg ManualDocument22 pagesWaldorf Zarenbourg ManualGiacomo FerrariNo ratings yet

- TN482Document9 pagesTN482syed muffassirNo ratings yet

- Display 090920122425 Phpapp01 PDFDocument37 pagesDisplay 090920122425 Phpapp01 PDFNihar PandaNo ratings yet

- Seleção FANCOIL SALA 1 Ou 2Document7 pagesSeleção FANCOIL SALA 1 Ou 2Gustavo RomeroNo ratings yet

- Tabnabbing Attack Method Penetration Testing LabDocument6 pagesTabnabbing Attack Method Penetration Testing LabEugenia CascoNo ratings yet

- Gantry Cranes PDFDocument2 pagesGantry Cranes PDFgrupa2904No ratings yet

![UFO Contact From Angels in Starships (Giorgio Dibitonto [Dibitonto, Giorgio]) (z-lib.org)](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/749961050/149x198/b8d175129f/1720793463?v=1)