Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Yamini Aiyar - Minority Rights Secularism

Yamini Aiyar - Minority Rights Secularism

Uploaded by

kareenavakilOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Yamini Aiyar - Minority Rights Secularism

Yamini Aiyar - Minority Rights Secularism

Uploaded by

kareenavakilCopyright:

Available Formats

Minority Rights, Secularism and Civil Society

Author(s): Yamini Aiyar and Meeto Malik

Source: Economic and Political Weekly , Oct. 23-29, 2004, Vol. 39, No. 43 (Oct. 23-29,

2004), pp. 4707-4711

Published by: Economic and Political Weekly

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4415706

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Economic and Political Weekly is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Economic and Political Weekly

This content downloaded from

122.187.205.42 on Tue, 20 Jun 2023 04:22:17 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IPerspetives

Minority Rights, Secularism

this category. Sewa is a trade union of over

3,00,000 women. Founded in 1972, its

main objective is to strengthen women's

and Civil Society

economic capabilities through advocacy,

credit provision and business develop-

ment services and in this process make

them self-reliant. The presence of signifi-

The Indian state has failed to recognise an actively address the cant Muslim communities in the geo-

graphic areas where Sewa works has meant

issue of the socio-economic rights of Muslims. Civil society that its interventions have contributed to

organisations mirror the tendencies of the state to prioritise strengthening their economic capabilities

cultural rights over the social and economic needs of the and in so doing empower Muslim women.

community. It is crucialfor civil society to interrogate its own This is evident from the fact that of a total

membership of 1,20,000 women, one third

position and develop a platform for concerted advocacy on

are Muslims.2 There are many such organi-

issues related to the socio-economic rights of the Muslim sations whose work has contributed

community. significantly to empowering Muslim com-

munities, examples of which include the

YAMINI AIYAR, MEETO MALIK Historically, democratic politics in IndiaBeti Foundation in Lucknow and the

has been complemented by a strong and Informal Workers Union in Tamil Nadu.

M n 'inority rights, particularly in the active civil society. A key characteristic Perhaps more relevant in the present

context of the Muslim com- of Indian civil society is its heterogeneitycontext is the second category of organi-

munity, have arguably been the and representation of multiple ideologiessations that emerged in response to the

most contested issue in contemporary and perspectives. Before undertaking an increasing communalisation of Indian

India. The rise of Hindu majoritarianism analysis of the ways in which civil societysociety, and have gained prominence over

as a powerful force in Indian democracy addresses minority rights, it is thus ne-the past decade or so. The rise of Hindutva

over the past two decades has meant the cessary to map out the range of strategiesforces since the 1980s brought with it a

virtual acceptance of an anti-Muslim dis-and interventions employed by various strong anti-Muslim rhetoric that has cap-

civil society organisations (CSOs) from

course by large segments of society. In this tured the imagination of many in India.

context, civil society has emerged the as aperspective of their impact on MuslimThis rhetoric is premised on the idea that

central player in championing the cause communities.1 To examine these organi- secularism has meant the 'appeasement'

of minority communities. This role is

sations, we propose a broad classificationof Muslims by the state, and it has given

particularly important in a politically of CSOs into three main categories. In the currency to perceptions of the Muslim

charged environment where the state is category are organisations that definecommunity as both pampered and threat-

first

often accused of abdicating its constitu-themselves as 'secular', i e, not working ening. It is in an attempt to counter such

tional responsibility to protect religious

for any particular religious community orperceptions that these organisations de-

minorities and, in some cases, even insti-

affiliated to any religious institution.veloped their approaches and strategies

Specifically, this category focuses on for intervention. The starting point for

gating violent attacks on them. This paper

is an attempt to interrogate civil society

organisations that work to promote the their work is the protection of the consti-

understandings of minority rights throughsocio-economic rights of marginalisedtutional guarantees accorded to minority

communities. These organisations too

communities and happen to be situated in

an analysis of the strategies and approaches

employed by some prominent civil society define themselves as secular and see their

areas with a sizeable Muslim population.

organisations whose work has influenced The ideological roots of these organisationsrole as critical in the struggle to preserve

the debate on minority rights. The focuscan be traced back to the 1970s when the and strengthen Indian democracy.

is on organisations working for and withcivil society space witnessed a proliferation Work in this area first gained promi-

Muslim communities, India's largest of organisations and movements fighting nence in 1985 with the formation of the

re-

ligious minority. Through this analysis,to protect the rights of marginalised com- Sampradayikta Virodhi Andolan, a forum

the paper presents a critique of the current

munities. These organisations and move- of secular NGOs with a mandate to pro-

ments emerged in response to a growing mote secular values in India. Since then,

debate, which has not adequately addressed

the problem of the social and economic sense of disillusionment with the ability the civil society landscape has seen the

deprivation suffered by large sections and

ofcommitment of the state to substan- proliferation of organisations working on

Muslims, and in so doing, confined tivelythe democratise Indian society and these issues. Important examples of these

debate to such issues as preserving the catalyse socio-economic transformation, groups are Anhad in New Delhi; Sabrang

secular and plural character of India, a role that it had been unconditionally Communications (of Communalism Com-

entrusted with at the time of independence bat fame) in Mumbai; the Ahmedabad

discussing the cultural rights of Muslims,

preventing anti-minority violence and [Tandon and Mohanty 2003]. The Mahila Community Foundation (also known as

holding the state accountable for violent

Sewa Trust, Ahmedabad, is an interesting the Citizen's Initiative); the Centre for the

attacks on Muslims. example of organisations that fall within Study of Society and Secularism (CSSS),

Economic and Political Weekly October 23, 2004 4707

This content downloaded from

122.187.205.42 on Tue, 20 Jun 2023 04:22:17 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mumbai and the Coalition of Voluntary As this rough sketch suggests, it is the

therefore, is on the preservation of cultural

Agencies (COVA) in Hyderabad. All these secular organisations working on commu- pluralism, and the focus of the Constitu-

groups emphasise the shared cultural tra-nal harmony on the one hand, and the tion is on the cultural rights of religious

ditions of the country, contest the anti-Muslim-run NGOs on the other, that are minorities [Hasan 2003]. This is reflected

minority rhetoric and actions of the the most vocal and influential when it in civil society's debates and interventions

Hindutva forces and attempt to make comes to articulating, prioritising and on minority rights.

interventions for improved relations representing Muslim issues. AlthoughSecular organisations working on issues

between Muslims and Hindus. In recent these organisations come from different related to the economic and social rights

years, particularly in the aftermath of the

ideological positions, they have a common

of marginalised communities more broadly,

violence in Gujarat, they have acquired a

starting do indirectly address issues of relevance

point - the constitutional guaran-

prominent position for the effective inter-

tees accorded to minority communities. toAMuslim communities. However, these

large part of their work is thus focusedorganisations

ventions they made in relief and rehabili- on do not have a specific

tation, and legal action to hold the state

holding the state accountable for the pre-

mandate to advocate the rights of Muslims

accountable to victims of violence. servation of these guarantees. At this point,

and are thus not influential in setting policy

The third category of organisations in-

it may be useful to step back and briefly agendas in the sphere of minority rights.

cludes those headed by Muslims with the examine the constitutional provisions and This is the case even among organisations

state policies directed at religious minori-

specific mandate of working to protect the such as Sewa Lucknow that work almost

rights of the Muslim community. These ties. The basic principle through which exclusively with Muslims. Founded in

organisations are generally accepted minority

as rights have been articulated 1984,

in Sewa Lucknow is an organisation

India is that of secularism. Defined as

representatives of Muslim perspectives and of chikankari workers, a hereditary craft

occupy prominent positions both in the practised by Muslim women based in

equality of all religious beliefs, secularism

media and the political sphere for theirunderlies the spirit of the Indian Consti- Lucknow. Despite the fact that Sewa

opinions on issues such as the uniform tution and mandates that the state will not Lucknow members are almost exclusively

civil code and Babri masjid. The All-India

be aligned to any one religion, all citizensMuslim women (in its initial phase it had

Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB) will have the freedom of religious belief, a 100 per cent Muslim membership, how-

and minorities will not be discriminated

and the All-India Milli Council are promi- ever, in recent years several Hindu women

nent amongst these. The AIMPLB was

against in any way. Under the Consti-

have joined the organisation), it is best

established in 1972 with a mandate to tution, religious minorities are given the

known for its advocacy and interventions

protect Muslim personal law. The Milli right to observe and preserve their language,on women's rights, education and labour

Council was established in 1992 to further culture and religious practices, and torights rather than on specific issues related

the social, political and educational ad- establish and administer their own educa- to the Muslim community.5 It is worth

vancement of Muslims.3 Arguably, their tional institutions. Moreover, the Consti-mentioning here that there are some

starting points are somewhat similar to the tution retains separate personal laws fororganisations, notably Awaz-e-Niswan in

secular organisations working for com-different communities, thus ensuring that Mumbai and the Mahila Sahbhagita

munal harmony described above, in thatreligious minorities be governed by theirSansthan in Varanasi, that are working for

they too work for the protection of the own community codes. The emphasis, the empowerment of Muslim women in

constitutional guarantees accorded to

minority communities and in so doing aim

Child on the Wing:

to preserve the democratic space for

Children Negotiating the Everyday

Muslims in India. However, the difference

in the Geography of Violence

lies in their ideological base. Crucially,

Department of Anthropology, Johns Hopkins University

these organisations identify themselves

specifically with the Muslim community, Two Rockefeller Research Fellows, 2005/2006

and to that extent can be described as Child on the Wing is a project of the Department of Anthropology at the Johns Hopkins University, funded

'communal'. Moreover, these organi-

by The Rockefeller Foundation. The program focuses on the mobile trajectories of children's lives under

conditions of ongoing political violence and economic uncertainty.

sations have been caught in politics that

Child on the Wing invites applications for residential fellows who are conducting innovative interdisciplinary

aims to preserve spaces for Muslims within

research (academic, policy or advocacy-related) on children and work, children as political actors, and

a framework of Islam that does not address children responding to situations of war and ethnic or sectarian conflict. Applications should be at least

three years beyond receipt of the PhD or have three years of experience with NGOs or policy-making.

the more substantive questions of demo-The length of the fellowship is one year at Johns Hopkins, including one four-month semester at a fieldwork

cratisation of structures within the com- site. The Department will host workshops in the final year (2006/2007) to which fellows will be invited

to present their research. A final publication will be compiled from research contributions.

munity. The AIMPLB's interpretation of

The salary is $40,000 for the year, plus health insurance, airfare and contributions towards research

Muslim personal laws in the context of the costs. Further details of the program and information for applicants are available at www.jhu.edu/child.

Shah Bano case is an important example Application deadline: 31 January 2005

of this.4 The Milli Council has done some The Johns Hopkins University DOES NOT DISCRIMINATE For information please contact:

work in the area of socio-economic ad- ON THE BASIS OF RACE, COLOR, GENDER, RELIGION, SEXUAL Veena Das or Pamela Reynolds,

ORIENTATION, NATIONAL OR ETHNICORIGIN, AGE, DISABILITY, MARITAL Department of Anthropology

vancement of the community, most nota-STATUS, OR VETERAN STATUS IN ANY STUDENT PROGRAM OR ACTIVITY Johns Hopkins University

bly on issues related to the modernisationADMINISTERED BY THE UNIVERSITY OR WITH REGARD TO ADMISSION 404 Macaulay Hall

OR EMPLOYMENT. DEFENSE DEPARTMENT DISCRIMINATION IN ROTC 3400 North Charles Street Baltimore,

of madrasas. However, their politics tooPROGRAMS ON THE BASIS OF SEXUAL ORIENTATION CONFLICTS WITH MD 21218. USA

THIS UNIVERSITY POLICY. THE UNIVERSITY IS COMMITTED TO Tel: 410.516.7272 Fax: 410.516.6080

appeals to the more retrogressive voicesENCOURAGING A CHANGE IN THE DEFENSE DEPARTMENT POLICY. Email: straderl @jhu.edu

within the community and they have notQUESTIONS REGARDING TITLE Vi, TITLE IX AND SECTION 504 * f M

SHOULD BE REFERRED TO THE OFFICE OF EQUAL OPPORTUNITY,

been able to adequately fight for the rights N-710 WYMAN PARK BLDG, HOMEWOOD CAMPUS, 410-516-8075

of those marginalised.

4708 Economic and Political Weekly October 23, 2004

This content downloaded from

122.187.205.42 on Tue, 20 Jun 2023 04:22:17 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

India. However, these organisations are Sections of civil society in India hold the

employed in the executive and supervisory

few and far between and they have not yet cadre, and as workers is dismally low state accountable for the increased

been able to develop a strong sphere of [Razzack and Gumber 2002]. communalisation of society, attacks o

influence within and outside the Muslim Despite the overwhelming evidence constitutional

of protections for the minor

community. ties and the frequent pogroms directe

the socio-economic deprivation of Muslims

As this overview suggests, civil society against Muslims. Given the so-calle

in India, debate and action on these issues

has been most vocal on Muslim issues rarely features in the civil society dis-watchdog role that civil society plays

when it comes to advocacy for the course pre- on minority rights. The relationshipa democracy, it is only natural that in t

between socio-economic deprivation and

servation of the secular fabric of the country, present political context, civil society acti

understood both as preserving the consti- religious identity is a complex one. Ana-for minority rights is focused on the pro

tutional guarantees of Muslims as well as

lytically tection of constitutional rights, strengt

they appear to be separate issues,

promoting communal harmony. In essence, however, real experience proves other- ening secularism and preventing violenc

civil society interprets minority rights wise. This is evidenced by factors such as The most pressing concern, as articu

the decline of Urdu in north India and

within the limitations set by the Constitu- lated by civil society activists, is t

Andhra

tion, where rights are defined primarily as Pradesh, its impact on the educa-

overpowering problem of violence encou

cultural. Broader issues of socio-economic tered by the Muslim community and th

tional status of Muslims and their ability

rights are not seen as unique to the Muslim

to gain employment; and the under-repre- need to preserve the secular fabric of th

community and are addressed indirectly country. Activists such as Harsh Mand

sentation of Muslims in public institutions

through work on socio-economic rights and Shabnam Hashmi argue that whi

[Mohapatra 2002; Mehta 2004]. In recent

more generally. years, attempts have been made to analyse

ensuring the social and economic rights

these relationships more systematically.

Muslim communities is of critical impo

Barbara Harriss White, for instance, tance,

has it is extremely difficult to priorit

Limitations of Civil Society

Perspective examined the implications of religious this when the entire community is und

plurality on a capitalist economy and ar-

attack. Therefore, the pressing task is

Despite civil society's preoccupationgues for the role played by religious iden-

strengthen communal harmony; improv

tity in shaping economic capabilities

with the issue of cultural rights, there is Hindu-Muslim relations and ensure that

an emerging body of literature that points[Harriss White 2002]. Another emerging more civil society organisations and social

to the poor human development status of body of work examines the relationship movements include in their agendas the

Indian Muslims, who suffer from wide- issues of increasing communalism and

between the relative deprivation experi-

spread illiteracy, low income, irregular

enced by minorities and argues that dis-

violence against minority communities.

crimination is a critical factor that contrib-

employment and a high incidence of This dilemma of prioritisation is reflected

poverty [Razzack and Gumber]. Studiesutes to the socio-economic exclusion of in the work of COVA, a network of over

suggest that Muslims on the whole have minority communities [Justino and 800 voluntary organisations whose vision

Litchfield 2003]. These studies and expe-

an average standard of living less than even is to promote communal harmony and bring

the OBCs and well below that of upper caste

riences highlight the fact that disadvantage

the Muslim community into the mainstream

Hindus [Hasan and Menon 2002]. Accord-and disempowerment are experiencedof atdevelopment processes in India. Con-

ing to the 50th and 55th rounds of thespecific intersections of religion, class,

sequently, much of COVA's direct com-

National Sample Survey Organisation, in

caste and gender. Consequently, any dis-

munity development work is concentrated

1993 and 1999-2000, Muslims were worsecussion on minority rights, if it wereintoMuslim-dominated areas such as the old

off than their counterparts in the majority city in Hyderabad. However, COVA is

truly address the experiences of minorities

community on all major socio-economic in its entirety, must necessarily address best

the known for the work it has undertaken

indicators. They spend less on consump- question of socio-economic disadvantageto develop alliances within the civil soci-

tion because they earn less. The incidence

faced by the community. ety sphere to strengthen activism for com-

of poverty is higher among Muslims than What explains the direction of the current

munal harmony. Its advocacy stops short

Hindus. Literacy rates are substantially civil society discourse on minority rights of directly addressing the question of the

lower among Muslims - in rural areasand the conspicuous absence of debate social and economic rights of Muslims

illiteracy is at 44 per cent among Hindus and action on issues related to the socio- despite the fact that they are actively

and 48 per cent among Muslims. They are economic rights of the Muslim community? working for their upliftment.

more likely to be employed as casual labour To understand this, it is necessary to

than Hindus. In rural India, they are furtherexamine the relationship between civil

State and Minority Rights

marginalised in terms of access to land -society and the state. Political theorists

51 per cent of Muslims are landless againstagree that civil society is a crucial pillar An important factor contributing to the

40 per cent of Hindus. And finally, unem- of democracy. However, its relationship nature of the current debate on minority

ployment rates are significantly higher vis-a-vis the state is open to contestation. rights is the fact that the Indian state has

among Muslims at 5.5 per cent, against 4 Some proponents of civil society see it as fallen short of recognising and actively

per cent for Hindus [Reddy 2002]. They an alternative to the state.6 More convinc- addressing the issue of the socio-economic

have a nominal presence in the adminis- ing, however, is the position that civil rights of Muslims. Zoya Hasan's analysis

trative, police and defence services, and society operates in tandem with the state, of the relationship between the state and

more or less no share in financial and where its most critical role is to counter minority communities is significant in this'

banking institutions. Significantly, eventhe

in hegemonising tendencies of the latter regard. Hasan argues that the constitu-

the private sector, there is evidence and

to ensure that citizens' rights are pro- tional provisions for religious liberty and

suggest that the number of Muslims tected [Chandoke 2003; Elliott 2003]. cultural rights of minorities have proved

Economic and Political Weekly October 23, 2004 4709

This content downloaded from

122.187.205.42 on Tue, 20 Jun 2023 04:22:17 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

inadequate in protecting them against religious community or ethnic group too vocal demand from within the community

discrimination and exclusion. Taking the has a similar impact- to actively address these issues. This needs

argument further, she suggests that the It thus appears that in engaging with the to be understood within the broader con-

state's failure to ensure the socio-economic broader political discourse on secularism text of the history of Muslim polity in

development of India's minorities is tan- and minority rights, civil society contemporary India. In the immediate post-

tamount to discrimination [Hasan 2003]. organisations mirror the tendencies of the independence era, Muslim communities

Hasan's argument is substantiated by the state to prioritise cultural rights over the largely supported the Congress Party,

fact that although widespread evidence of social and economic needs of the commu-

whose agenda for secularism was seen as

the dismally poor socio-economic status nity. There have, however, been a fewcritical to their well-being. However, the

of Muslims led the Gopal Singh committee sporadic attempts at bringing this issuelate 1960s witnessed a growing disenchant-

to declare them to be a 'backward com- into the public discourse. One such ex- ment with the Congress' opportunistic

munity' in India as early as 1983, and ample is the All-India Backward Muslimpolitics, leading to a decline of Muslim

government reports do acknowledge the Morcha (AIBMM), which was set up insupport for the party. This period also

backwardness and deprivation of Mus-Bihar under the leadership of Eijaz Ali incoincided with the rise of sectarian vio-

lims, there are very few policies aimed at1994. The organisation advocates for thelence in India that encouraged the more

redressing it. Indeed, government policiesneeds of the dalit-Muslim community. Itfundamentalist voices within the commu-

in economic upliftment of the minoritieshas a strong caste base and argues that thenity to occupy the political centre stage.

are conspicuous by their absence [ibid].upper caste Muslim leadership thrives onThese voices emphasised the need to

Arguably, this inability of the state tochampioning such 'communal' 'non- preserve cultural spaces for Muslims with

address the socio-economic deprivation issues' as the protection of the Muslimno efforts to secularise the community

faced by religious minorities can in partpersonal law and the Babri masjid. Theymore generally. Consequently, the politi-

be traced back to the Constitution, whichmake a strong case for redistributive cal discourse on minority rights as articu-

explicitly articulates the need to preserve

policies and affirmative action in jobs andlated by Muslims came to be synonymous

in education to be extended to the dalit-

the cultural rights of religious minorities with the preservation of a separate Muslim

and not their economic, social or political

Muslims. Further, this new leadership culture in India rather than securing rights

rights.7 As Rochna Bajpai points out, theargues that since the primary concern of for the disempowered within the commu-

dominant nationalist opinion in the con- backward caste Muslims is sheer physical nity [Mohapatra 2002; Mehta 2004]. In

stituent assembly, represented by thesurvival, jobs and wages, there is a need spite of the absence of a sustained political

Congress and its supporters among minor- to bring about 'a revolution of priorities' demand to address the socio-economic

ity leaders, held that the backwardness of[Sikand 2004]. Recently, members of the rights of Muslims from within the com-

a group was a legitimate ground for group AIBMM even went to the extent of sug- munity itself, there is enough evidence to

preference provisions. However, the per-gesting that the Muslim community would show that many Muslims are concerned

ceived need to preserve a distinct culturalbe willing to trade the Babri masjid issue about these issues. Moreover, activists such

identity was not [Bajpai 2000; Mohapatra in exchange for reservations for lower- as Sehba Hussain argue that even if the

2002:189]. This meant that while the caste Muslims [Tripathi 2003; Wright community fails to articulate its demand

scheduled castes and scheduled tribes came

1997]. Another example comes from the for social and economic rights, secular

within the purview of group preference work of Sanchetna, an NGO based in activists concerned with social justice have

Ahmedabad known for its work on com-

provisions, any debate on similar provi- a responsibility to ensure that these issues

sions for religious minority groups wasmunity health. More recently, Sanchetna enter into public discourse.

foreclosed.8 In the absence of constitu-

has been involved in work on communal This brings us to the important point of

tional guarantees, debates about the rela-

harmony, particularly in the post-Godhra representation, which has been offered as

tive deprivation of Muslims have not found

context. As early as 1992, Sanchetna a powerful critique of civil society. Critics

organised a nationwide consultation at-

much space in the political sphere, which of the concept of civil society argue strongly

continues to be dominated by discussionstended by over 8,000 Muslims. During this that it often falls into the trap of reproduc-

on the cultural rights of the community.consultation, the pressing concerns articu- ing within itself the very power relations

A similar case can be made for civil lated by members of the community were that it seeks to challenge. Chandoke, for

society, where organisations that viewnot those related to the demolition of the instance, highlights the exclusionary ten-

themselves as secular are reluctant to beBabri masjid or the preservation of the dencies within civil society and argues that

seen as working exclusively for any par- Muslim personal law; rather, they were of although developing countries are mostly

ticular religious community. As Imtiazeducation and employment. Voices such rural, it is the urban middle class agenda

Ahmed argues, secularism has been the as these have not gained prominence at the that is articulated through civil society. As

paradigm within which CSOs have de- national level nor have they found space a result, marginalised groups struggle for

fined themselves since independence, and in civil society debates on minority rights. recognition not only from the state but also

within this definition identification with Interestingly, despite this consultation, in the civil society sphere. Further, she

a specific religious community is equated Sanchetna does not have a specific argues that the language, narratives, vo-

with being communitarian and even com- programme on the socio-economic rights cabulary and symbols that civil society

munal. In so doing, civil society organi- of Muslims and like COVA is best known uses constitute an exclusive dominant

sations have fallen into the same trap asfor its work on communal harmony. discourse that prevents the marginalised

the state of not recognising that while Another reason offered for the con- from representing their perspectives in

caste, class and gender are significant inspicuous absence of advocacy and action struggles that are ostensibly in their name

determining the structural constraints facedon the socio-economic rights qf Muslims

[Chandoke 2003]. When viewed from the

by individuals, belonging to a particularis that there has been no concerted and perspective of minority rights, Chandoke's

4710 Economic and Political Weekly October 23, 2004

This content downloaded from

122.187.205.42 on Tue, 20 Jun 2023 04:22:17 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

critique of civil society finds resonance. importance of this is best demonstrated in thank Kamal Farooqi of the Milli Council for

Secularism embodies the idea of India that his insights on the history of both these

the body of research and action that has organisations.

evolved through the freedom struggle and emerged from the experiences gained from 4 The new attempt at dissuading Muslims from

has since dominated the political and civil examining gender discrimination. The adopting the practice of triple talaq is a welcome

one. However, it is too soon to tell whether

society discourse. Arguably, civil society's paradigm of gender discrimination has

this is a sign of a change in ideology.

preoccupation with this discourse has contributed greatly to current understand- 5 It is important to emphasise here that while

meant that attacks on Muslims are seen as ings of social inequality, and more impor- these 'secular ' organisations do not concern

tantamount to attacks on secularism and in themselves specifically with Muslim issues in

tantly, has proved critical in devising

any sustained way, they do come together to

protecting secularism, civil society sees itself effective poverty alleviation strategies. A intervene in crisis situations, particularly in

as protecting minority rights. In so doing, similar case can be made to examine the the event of communal violence.

the everyday experiences of Muslims, 6 This position is most widely held by political

impact of discrimination on minority scientists of the western liberal tradition who

particularly their material deprivation, are communities, and design policy interven- see civil society as the locus of political action

neither recognised nor addressed. More- tions that consider their specific needs. by autonomous social movements opposed to

over, organisations such as the AIBMM Civil society, despite its limitations, is an invasive and all encompassing state.

7 Articles 14 and 15 of the Constitution guarantee

that do actively raise these concerns are an important space within which the equality of minorities before the law.

struggling to find the space to be heard. marginalised communities can articulate Articles 25 and 26 guarantee the right to freedom

their needs and demands and negotiate of religion and Articles 29 and 30 guarantee

the conservation of language and education.

Conclusion with the state for their rights. In the current

8 In contemporary India, too, any debate on

context in India, where Muslims have been special provisions for minority communities

Civil society's inability to adequately

marginalised in the political sphere, the immediately becomes a point of contention;

address the problem of material depriva-

role that civil society can play in providing the Hindu right sees it as giving unnecessary

concessions and the secularists argue that

tion of Muslims highlights not only thethe

necessary space for Muslims to articu- religion is not a sufficient basis for

late their needs is particularly relevant.

hegemonic tendencies within civil society, concessionary provisions.

Hence

but also the gaps in civil society's role as it is critical that civil society re- References

an effective watchdog to the state. In

examine its current understandings of

addressing issues of cultural rights and

minority rights. Crucially, in focusing on Bajpai, Rochana (2000): 'Constituent Assembly

working to protect the constitutionalissues

guar-of substantive equality in addition Debates and Minority Rights', Economic and

Political Weekly, May 27.

antees of the communities, civil society

to those of identity, and placing minority Chandoke, Neera (2003): The Conceits of Civil

communities within a web of socio-

has played an indispensable role. However, Society, New Delhi, pp 1-35

it has been unable to effectively push the

economic Elliott,

structures, opportunities and con- Carolyn M (ed) (2003): Civil Society and

Democracy: A Reader, New Delhi, pp 1-37

straints,

state to move beyond the limits it has set on civil society will also succeed in

Harris White, Barbara (2002): 'India's Religious

minority rights. It is crucial thereforemoving

for away from the current emphasis Pluralism and Its Implications for the Economy',

on identity and cultural difference

civil society to interrogate its own position Working Paper No 82, Queen Elizabeth House

Working Paper Series, University of Oxford.

and through this develop a platform for

towards a more nuanced understanding of

Hasan, Zoya (2003): 'Social Inequalities,

concerted advocacy on issues related to minority

the rights. [ Secularism and Minorities' in Mushirul Hasan

socio-economic rights of the community. (ed): Will Secular India Survive?, New Delhi.

It is important to recognise that there

Address for correspondence: Hasan, Zoya and Ritu Menon (2002): 'Women,

Interrupted', The Indian Express, December 19.

have been some efforts in this direction,

aiyar_y @ yahoo.com Justino, Patricia and Julie Litchfield (2003):

particularly after the surprise victory of the Ecoznomic Exclusion and Discrimination: The

Notes

Congress Party and its allies in the May 2004 Experiences of Minorities and Indigenous

Peoples, Minority Rights Group, London.

general elections. This victory has been Mehta, Pratap Bhanu (2004): 'Will Reservation

[We would like to thank Imtiaz Ahmed, Sehba

viewed by many civil society activists as

Hussain, HanifLakdawala, Harsh Mander, Shabnam Benefit the Muslims in India', The Indian

a much needed breathing space that has Mazhar Hussain, Syeda Hameed and

Hashmi, Express, July 15.

created the conditions for a review of Bishnu Mohapatra for the discussions we had with Mohapatra, Bishnu (2002): 'Democratic

them and the insights they provided us with.] Citizenship and Minority Rights: A View from

strategies. Some go so far as to suggest that India' in Catarina Kinnvall and Kristina

this victory has helped dissipate fears1 ofWe recognise the ambiguities that surround Jonsson (eds), Globalisation and

the concept of civil society. For the purposes Democratisation in Asia: The Construction

physical security experience by the com-

of this paper, we define civil society as the Identity, London, p 183.

munity in the last 10-odd years, thereby sphere located between the individual, the Razzack, Azra and Anil Gumber (2002):

creating the spaces to address the issue of

market and the state consisting of formal and 'Differentials in Human Development: A Case

informal associations, movements and forms for Empowerment of Muslims ini India',

reform from within. The AIMPLB July 2004

of organisation. There have been numerous National Council of Applied Economic

declaration to promote the notion of attempts

a at mapping civil society organisations Research, New Delhi, May.

reformed nikahnama and declare the triplein India (Rajesh Tandon, 'Civil Society in Reddy, C Rammanohar (2002): 'Deprivation

India: An Exer ise in Mapping' in Innovations

talaq as a social ill is seen as an important Affects Muslims More', The Hindu, September

in Civil Society, V- 1, July 2001, pp 2-8; Niraja 12 and 13.

indication of the move from within the

Gopal , 'India' in Tadashi Yamamoto (ed), Sikand, Yogindar (2004): 'The Dalit Muslims and

community to initiate a process of social Governance and Civil Society in a Global the All India Backward Muslim Morcha',

reform. It is critical, therefore, that civil society Age, pp 116-53, 2001). Broadly speaking there www.countercurrents.org/dalit-sikander

organisations come together to debate and are two distinct types of civil societyTandon, Rajesh and Ranjita Mohanty (ed) (2003):

organisations - social movements and non- Does Civil Society Matter? Governance in

identify new strategies and approaches that government organisations. This paper will Contemporary India, New Delhi, pp 12-14.

address the issue of socio-economic rights follow this classification. Tripathi, Purnima (2003): 'The Temple Stand-

of Muslims. Perhaps it may be useful for 2 'Shanti Path: Our Road to Restoring Peace', Off', Frontline, Vol 20, Issue 14, July 18.

www.sewa.org, downloaded on 2/4/2004 Wright, Thomas (1997): 'A New Demand for

organisations to examine these issues 3 Milli Gazette, editorial July 1-15, 2002, Muslim Reservation in India', Asian Survey,

through the lens of discrimination. The www.milligazette.com. We would also like to Vol xxxvii.

Economic and Political Weekly October 23, 2004 4711

This content downloaded from

122.187.205.42 on Tue, 20 Jun 2023 04:22:17 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- First Holy Communion Mass TextDocument16 pagesFirst Holy Communion Mass TextJecintha Josephine100% (3)

- Understanding Social ActionDocument18 pagesUnderstanding Social ActionS.Rengasamy94% (35)

- This Content Downloaded From 154.59.124.112 On Tue, 06 Jul 2021 16: Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTCDocument27 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 154.59.124.112 On Tue, 06 Jul 2021 16: Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTCAltafNo ratings yet

- Engineer CommunalismCommunalViolence 1986Document13 pagesEngineer CommunalismCommunalViolence 1986Cliff CoutinhoNo ratings yet

- Evolution and Growth: Social Capital - A Shared DestinyDocument10 pagesEvolution and Growth: Social Capital - A Shared DestinyPankaj PatilNo ratings yet

- Asia Pacific Journalism On CastesDocument13 pagesAsia Pacific Journalism On CastesKishore KumarNo ratings yet

- Socio Unit 2 NotesDocument14 pagesSocio Unit 2 Notesananya singhNo ratings yet

- Empowerment of TribalsDocument13 pagesEmpowerment of TribalsramakaniNo ratings yet

- Model Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Perspektif Islam: FALAH Jurnal Ekonomi Syariah October 2016Document18 pagesModel Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Perspektif Islam: FALAH Jurnal Ekonomi Syariah October 2016Lilik Wahyu PrastyoNo ratings yet

- When Rights Go WrongDocument10 pagesWhen Rights Go WrongNiveditha MenonNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Concepts and Practice of Community Organizing: June 2012Document36 pagesTheoretical Concepts and Practice of Community Organizing: June 2012Lito PangulabnanNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Concepts and Practice of Community Organizing: June 2012Document36 pagesTheoretical Concepts and Practice of Community Organizing: June 2012imaNo ratings yet

- Development Processes and Development Industry PDFDocument20 pagesDevelopment Processes and Development Industry PDFVikram Rudra PaulNo ratings yet

- Globalisation and Social Justice - 1Document5 pagesGlobalisation and Social Justice - 1Prachi NarayanNo ratings yet

- Community Organisation Notes Unit 1Document22 pagesCommunity Organisation Notes Unit 1dhivyaNo ratings yet

- Caste As Social CapitalDocument5 pagesCaste As Social CapitalNutan SharmaNo ratings yet

- Unit IV Social Work With Communities and Social Action. 1Document57 pagesUnit IV Social Work With Communities and Social Action. 1Mary Theresa JosephNo ratings yet

- Mancilla AslmidtermDocument22 pagesMancilla AslmidtermMarianne MancillaNo ratings yet

- Socio-Economic Conditions and Social Acceptance of Transgender Community: An Empirical StudyDocument5 pagesSocio-Economic Conditions and Social Acceptance of Transgender Community: An Empirical StudyIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Concept of Community Organization MeaninDocument8 pagesConcept of Community Organization MeaninDivyaNo ratings yet

- Civil Society and Social Development in Pakistan-DRI-PCPDocument12 pagesCivil Society and Social Development in Pakistan-DRI-PCPsummra khalidNo ratings yet

- Unit 6 Institutional Support For Women MobilizationDocument20 pagesUnit 6 Institutional Support For Women MobilizationRoba AbeyuNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Community OrganizationDocument8 pagesUnit 1 Community OrganizationAbhi VkrNo ratings yet

- ShahidDocument7 pagesShahidIshteyaq AhamadNo ratings yet

- Building Sustainable Farmer Cooperatives in The Mekong Delta, Is Social Capital The KeyDocument19 pagesBuilding Sustainable Farmer Cooperatives in The Mekong Delta, Is Social Capital The KeyTNo ratings yet

- Christian Living Module 4week 4Document2 pagesChristian Living Module 4week 4jomarov funovNo ratings yet

- Community Organisation Notes Unit Ii History of Community Organisation: ContentsDocument46 pagesCommunity Organisation Notes Unit Ii History of Community Organisation: ContentsTirumalesha DadigeNo ratings yet

- NGO, Social Capital and MicrofinanceDocument12 pagesNGO, Social Capital and MicrofinanceMuhammad RonyNo ratings yet

- MAHAJANDocument9 pagesMAHAJANscholar.lkoNo ratings yet

- Modul Pemberdayaan Masyarakat E Learning Volunteer by IDVolunteering Community Link CIMB NiagaDocument55 pagesModul Pemberdayaan Masyarakat E Learning Volunteer by IDVolunteering Community Link CIMB NiagaAmmar AbiNo ratings yet

- Democracy and Social Justice in India Lessons From Lohias SocialismDocument14 pagesDemocracy and Social Justice in India Lessons From Lohias Socialismshimlahites0% (1)

- The Future of Social Action in India 2018-2047Document14 pagesThe Future of Social Action in India 2018-2047kelothNo ratings yet

- Sociology Individual AssignDocument14 pagesSociology Individual AssignrachtiNo ratings yet

- Master in Social WorkDocument109 pagesMaster in Social Workpriya_ammu0% (1)

- Social Justice and Social Development of Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes in Maharashtra - TICI JournalDocument34 pagesSocial Justice and Social Development of Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes in Maharashtra - TICI JournalAyan GuptaNo ratings yet

- Community Organisation NotesDocument95 pagesCommunity Organisation NotesArull Msw100% (2)

- The Concept of The Indian Marginalized Communities: ArticleDocument10 pagesThe Concept of The Indian Marginalized Communities: ArticleVARSHA MOHANNo ratings yet

- Rifan Nur Rohamtulloh - MAIN IDEADocument13 pagesRifan Nur Rohamtulloh - MAIN IDEAYuni SakilaNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Social CapitalDocument6 pagesFundamentals of Social Capitalpaovz13No ratings yet

- 2014-03-26 125309 Sarvodaya1Document15 pages2014-03-26 125309 Sarvodaya1Om GuptaNo ratings yet

- Community OrganizationDocument9 pagesCommunity Organizationchristopher capinpinNo ratings yet

- Arab Civil Society at The Crossroad of DDocument11 pagesArab Civil Society at The Crossroad of DLê Cẩm NhungNo ratings yet

- Role of NGOs in IndiaDocument17 pagesRole of NGOs in IndiatrvthecoolguyNo ratings yet

- Social Work With Community Organization: A Method of Community DevelopmentDocument9 pagesSocial Work With Community Organization: A Method of Community DevelopmentMOHD SHAKILNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Social Work Concepts-IIDocument13 pagesIntroduction To Social Work Concepts-IILangam MangangNo ratings yet

- Business Environment Unit-3Document19 pagesBusiness Environment Unit-3bharath donNo ratings yet

- Unit 3Document18 pagesUnit 3kandagallpraveen55No ratings yet

- Women Sel Help GroupsDocument24 pagesWomen Sel Help Groupsretheesh sugunanNo ratings yet

- Hasenfeld - Garrow.nonprofits and Rights Advocacy - BARRIERSDocument29 pagesHasenfeld - Garrow.nonprofits and Rights Advocacy - BARRIERSjany janssenNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 161.29.8.116 On Wed, 06 Sep 2023 04:52:09 +00:00Document23 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 161.29.8.116 On Wed, 06 Sep 2023 04:52:09 +00:00VincentWijeysinghaNo ratings yet

- Shri Ram Centre For Industrial Relations and Human Resources Indian Journal of Industrial RelationsDocument4 pagesShri Ram Centre For Industrial Relations and Human Resources Indian Journal of Industrial RelationsRamanahVRamanahNo ratings yet

- SHG DelhiDocument236 pagesSHG DelhikarthikNo ratings yet

- Christian Living Module 4week 4Document2 pagesChristian Living Module 4week 4jomarov funovNo ratings yet

- Block-1 Concepts of Community and Community DevelopmentDocument103 pagesBlock-1 Concepts of Community and Community DevelopmentAnanta ChaliseNo ratings yet

- Public Administration Unit-92 Role of Voluntary AgenciesDocument9 pagesPublic Administration Unit-92 Role of Voluntary AgenciesDeepika SharmaNo ratings yet

- Rural Civil SocietyDocument57 pagesRural Civil SocietymarcelocrosaNo ratings yet

- Social Interaction and The Development of SocietiesDocument15 pagesSocial Interaction and The Development of SocietiesMyvilline Cargado0% (1)

- Dokt. Murithi A. Social Foundations of Law NotesDocument41 pagesDokt. Murithi A. Social Foundations of Law NotesSarah MwendeNo ratings yet

- Unit Vii. Community Service/ImmersionDocument7 pagesUnit Vii. Community Service/ImmersionKen KanekiNo ratings yet

- Communalism, Caste and ReservationsDocument9 pagesCommunalism, Caste and ReservationsGeetanshi AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Community Mobilization Leadership and EmpowermentFrom EverandCommunity Mobilization Leadership and EmpowermentNo ratings yet

- Redalyc: Araya Araya, KarlaDocument5 pagesRedalyc: Araya Araya, KarlakareenavakilNo ratings yet

- Law 515 Jurisprudence and Legal Theory IDocument71 pagesLaw 515 Jurisprudence and Legal Theory IkareenavakilNo ratings yet

- Office of District Legal Services Authority, AurangabadDocument6 pagesOffice of District Legal Services Authority, AurangabadkareenavakilNo ratings yet

- Mamaearth Digital Marketing Strategies and Case StudyDocument20 pagesMamaearth Digital Marketing Strategies and Case StudykareenavakilNo ratings yet

- AIR Online - PDF 2 Right of Cross ExaminationDocument3 pagesAIR Online - PDF 2 Right of Cross ExaminationkareenavakilNo ratings yet

- Neera Chandhoke - of States and Civil SocietyDocument5 pagesNeera Chandhoke - of States and Civil SocietykareenavakilNo ratings yet

- Proverbs 4Document50 pagesProverbs 4Maradine TepNo ratings yet

- 1 - Be Ye Holy As I Am HolyDocument13 pages1 - Be Ye Holy As I Am HolyAnonymous CKg2M9SnNo ratings yet

- Greatest Nations 03 ElliDocument408 pagesGreatest Nations 03 ElliShouBunKunNo ratings yet

- Islam at A GlanceDocument100 pagesIslam at A GlanceMKPashaPashaNo ratings yet

- Hope Is The Thing With Feathers by Emily DickinsonDocument3 pagesHope Is The Thing With Feathers by Emily DickinsonAndreea-Daniela Chirita100% (1)

- NehemiahDocument35 pagesNehemiahRaelene Allen50% (2)

- The Cipus Episode in Ovid's MetamorphosesDocument12 pagesThe Cipus Episode in Ovid's MetamorphosesDr-AlyHassanHanounNo ratings yet

- SodapdfDocument120 pagesSodapdfNina MaxNo ratings yet

- Dios Sana Hoy (God Still Hills) (James L. Garlow, 2005)Document32 pagesDios Sana Hoy (God Still Hills) (James L. Garlow, 2005)The Ucli Press67% (3)

- Richard S Hess Israelite Religions An ArDocument2 pagesRichard S Hess Israelite Religions An ArFabiano.pregador123 OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Unity Through LoveDocument40 pagesUnity Through Lovemoojanmomen2547No ratings yet

- Kashaful Aqaid (کشاف العقاید) (English)Document150 pagesKashaful Aqaid (کشاف العقاید) (English)www.alhassanain.org.englishNo ratings yet

- History of The Municipality of LlorenteDocument2 pagesHistory of The Municipality of LlorenteArjie Gongon100% (2)

- Avalon Sol UpdateDocument4 pagesAvalon Sol UpdateprysmaoflyraNo ratings yet

- Beyond Flesh There Lies A Human Being - DigitalDocument69 pagesBeyond Flesh There Lies A Human Being - DigitalPrateek PrakharNo ratings yet

- Edward Taylor's Mystical Imagery by Tabitha ElkinsDocument15 pagesEdward Taylor's Mystical Imagery by Tabitha ElkinstabitherielNo ratings yet

- History of PublishingDocument109 pagesHistory of PublishingkatipbartlebyNo ratings yet

- Illogical "Christian" Teachings: by Robert SchmidDocument6 pagesIllogical "Christian" Teachings: by Robert SchmidLIto LamonteNo ratings yet

- The Book of 1 EsdrasDocument77 pagesThe Book of 1 EsdrasNeil LaquianNo ratings yet

- The Life Story of Hannah Callowhill PennDocument15 pagesThe Life Story of Hannah Callowhill Pennapi-399468103No ratings yet

- The Forerunner Message in Isaiah 62Document6 pagesThe Forerunner Message in Isaiah 6291651sgd54sNo ratings yet

- Fpu Lesson 01Document9 pagesFpu Lesson 01edwardoughNo ratings yet

- Revolutionary Changes in The Atlantic World, 1750-1850: 0instructional ObjectivesDocument7 pagesRevolutionary Changes in The Atlantic World, 1750-1850: 0instructional ObjectivesD.j. Fan100% (1)

- The Opposition of The Shi Ites Towards Kalóm: With Particular Reference To Tarji× Asólib Muhammad Ibn Ibrahim Ibn Al-Wazir AL-SAN ÓNÔ (D. 840/1436)Document18 pagesThe Opposition of The Shi Ites Towards Kalóm: With Particular Reference To Tarji× Asólib Muhammad Ibn Ibrahim Ibn Al-Wazir AL-SAN ÓNÔ (D. 840/1436)Sultana AmiraNo ratings yet

- Marriage As A Civil Contract or A SacramDocument3 pagesMarriage As A Civil Contract or A SacramThe Abdul Qadeer ChannelNo ratings yet

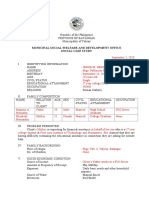

- Municipal Social Welfare and Development Office Social Case StudyDocument2 pagesMunicipal Social Welfare and Development Office Social Case StudyHannah Naki MedinaNo ratings yet

- Rasi Eng Xii All Marathon (1 To 20) Ques. Paper With Ans KeyDocument23 pagesRasi Eng Xii All Marathon (1 To 20) Ques. Paper With Ans KeyJeyarajanNo ratings yet

- Buena Presbyterian Records From PHSDocument5 pagesBuena Presbyterian Records From PHSadgorn4036No ratings yet

- Panja Ceremony in CeylonDocument5 pagesPanja Ceremony in CeylonmalaystudiesNo ratings yet