Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Autism and Paediatric Dentistry

Autism and Paediatric Dentistry

Uploaded by

Poli BMCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Barbaro & Dissanayake (2010) - SACS PDF FINAL PDFDocument10 pagesBarbaro & Dissanayake (2010) - SACS PDF FINAL PDFAnonymous 75M6uB3Ow100% (1)

- PDHPE HSC Revision Questions 2010-18Document83 pagesPDHPE HSC Revision Questions 2010-18Jusnoor KAURNo ratings yet

- Practice Parameter For The Assessment andDocument21 pagesPractice Parameter For The Assessment andBianca curveloNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Problems and Emotional Stress in Children With BruxismDocument7 pagesBehavioral Problems and Emotional Stress in Children With Bruxismjeremy ludwigNo ratings yet

- Influence of Head and Linear GrowthDocument10 pagesInfluence of Head and Linear GrowthAMILA YASHNI MAULUDI ABDALLNo ratings yet

- MSC Child and Adolescent Psychology Psyc 1107 Advanced Research Methods For Child Development M01Document10 pagesMSC Child and Adolescent Psychology Psyc 1107 Advanced Research Methods For Child Development M01macapashaNo ratings yet

- Sensory Features in Autism, 2022Document10 pagesSensory Features in Autism, 2022chayah8lichtigNo ratings yet

- Relacion Entre Caries Dental y El Ambito FamiliarDocument12 pagesRelacion Entre Caries Dental y El Ambito FamiliarDEYBI JOSSUE PALACIOS VARONANo ratings yet

- Guia de Buenas Practicas para La Investigacion de Los TEA (CARLOS III) 7pDocument7 pagesGuia de Buenas Practicas para La Investigacion de Los TEA (CARLOS III) 7pJulio César Valdez LizárragaNo ratings yet

- Family Burden and Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders - Perspective of Caregivers - Misquiatti, Brito, Schmidtt & Assumpção (2015)Document9 pagesFamily Burden and Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders - Perspective of Caregivers - Misquiatti, Brito, Schmidtt & Assumpção (2015)eaguirredNo ratings yet

- Orthodontics/Craniofacial Growth and Development Oral PresentationDocument14 pagesOrthodontics/Craniofacial Growth and Development Oral PresentationAnye PutriNo ratings yet

- Issn: Issn: Papeles@correo - Cop.esDocument9 pagesIssn: Issn: Papeles@correo - Cop.esSidra iftikharNo ratings yet

- Trayectorias de Desarrollo Lingüístico en Niños Con AutismoDocument9 pagesTrayectorias de Desarrollo Lingüístico en Niños Con AutismoNatalia Castro MartinezNo ratings yet

- Review Systematic Review of The Literature On Characteristics of Late-Talking ToddlersDocument29 pagesReview Systematic Review of The Literature On Characteristics of Late-Talking ToddlersTiara Maharani HarahapNo ratings yet

- Sensory Profile in Children With Autism Disorder and ChildrenDocument9 pagesSensory Profile in Children With Autism Disorder and ChildrenCarolinaNo ratings yet

- Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder HandoutDocument2 pagesFetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Handoutapi-753995548No ratings yet

- Dysphonia in Children: Journal of Voice: Official Journal of The Voice Foundation July 2012Document5 pagesDysphonia in Children: Journal of Voice: Official Journal of The Voice Foundation July 2012Nexi anessaNo ratings yet

- Racial Ethnic DisparitesDocument8 pagesRacial Ethnic Disparitesto.urbinasantanaNo ratings yet

- Emotional Distress Resilience and Adaptability A Qualitative Study of Adults Who Experienced Infant AbandonmentDocument18 pagesEmotional Distress Resilience and Adaptability A Qualitative Study of Adults Who Experienced Infant AbandonmentLoredana Pirghie AntonNo ratings yet

- Stein Cermak2012OralcareexperiencesinASDDocument6 pagesStein Cermak2012OralcareexperiencesinASDzsazsa nissaNo ratings yet

- DisfoniaDocument5 pagesDisfoniaRosario Crisóstomo PinochetNo ratings yet

- Autism Spectrum Disorders: Advances in Understanding and Intervention StrategiesDocument7 pagesAutism Spectrum Disorders: Advances in Understanding and Intervention StrategiesRoman ClaudiaNo ratings yet

- Effectsof Early NeglectonlanguageandcognitionDocument9 pagesEffectsof Early NeglectonlanguageandcognitionFARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- Prof Ed - Child and AdolescentDocument4 pagesProf Ed - Child and AdolescentLindesol SolivaNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Early DiagnoDocument11 pagesThe Importance of Early Diagnoiuliabucur92No ratings yet

- Connor 41Document7 pagesConnor 41cta.catalunya8652No ratings yet

- Education by GeneticsDocument6 pagesEducation by Geneticschagula3468100% (1)

- Oct 2016Document6 pagesOct 2016End Semester Theory Exams SathyabamaNo ratings yet

- Children and Youth Services ReviewDocument7 pagesChildren and Youth Services ReviewNerea F GNo ratings yet

- 5 - Perry, R.E. - 2018Document20 pages5 - Perry, R.E. - 2018João PedroNo ratings yet

- Dental Caries and Oral Health Related Quality of Life of 3 Year Olds Living in Lima, PeruDocument9 pagesDental Caries and Oral Health Related Quality of Life of 3 Year Olds Living in Lima, PeruFrancelia Quiñonez RuvalcabaNo ratings yet

- Communication Disorders and Emotional/Behavioral Disorders in Children and AdolescentsDocument15 pagesCommunication Disorders and Emotional/Behavioral Disorders in Children and AdolescentsIamDong BajNo ratings yet

- tmpB80D TMPDocument8 pagestmpB80D TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Autism Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesAutism Literature Reviewnaneguf0nuz3100% (1)

- Autism Thesis PaperDocument5 pagesAutism Thesis PaperWebsiteThatWritesPapersForYouCanada100% (2)

- Autism Literature Review ExampleDocument6 pagesAutism Literature Review Exampleafmzadevfeeeat100% (1)

- Literature Review Example On AutismDocument5 pagesLiterature Review Example On Autismafmzsgbmgwtfoh100% (1)

- Programa Integral para La Enseñanza de Habilidades A Niños Con AutismoDocument12 pagesPrograma Integral para La Enseñanza de Habilidades A Niños Con AutismoCeleste InleNo ratings yet

- (2007) Ar. Grigorenko - How Can Genomics InformDocument8 pages(2007) Ar. Grigorenko - How Can Genomics InformJulián A. RamírezNo ratings yet

- An Anthropological Approach Exposed Pesticides: The Evaluation of Preschool Children in MexicoDocument7 pagesAn Anthropological Approach Exposed Pesticides: The Evaluation of Preschool Children in MexicoJhonnyNogueraNo ratings yet

- DownloadDocument8 pagesDownloadzhaba vonNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Parental Quality of Life Following An Autism Diagnosis For Their ChildrenDocument7 pagesAn Analysis of Parental Quality of Life Following An Autism Diagnosis For Their ChildrenInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka Proforma For Registration For Subject For DissertationDocument20 pagesRajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka Proforma For Registration For Subject For DissertationAsha JiluNo ratings yet

- 2020 - Brancher - Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Problemsand Parent-Reported Sleep Bruxism InschoolchildrenDocument7 pages2020 - Brancher - Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Problemsand Parent-Reported Sleep Bruxism InschoolchildrenCarmo AunNo ratings yet

- Autism Journal ReflectionDocument6 pagesAutism Journal ReflectionLockon StratosNo ratings yet

- Autism, Therapy and COVID-19Document10 pagesAutism, Therapy and COVID-19Antonella CavallaroNo ratings yet

- HHS Public AccessDocument22 pagesHHS Public AccessDennis MejiaNo ratings yet

- Original Research Article: ISSN: 2230-9926Document4 pagesOriginal Research Article: ISSN: 2230-9926williamNo ratings yet

- Oral Health-Related Quality of Life of Schoolchildren: Impact of Clinical and Psychosocial VariablesDocument8 pagesOral Health-Related Quality of Life of Schoolchildren: Impact of Clinical and Psychosocial VariablesJuliana MoroNo ratings yet

- Introduction For A Research Paper On AutismDocument7 pagesIntroduction For A Research Paper On Autismh015trrr100% (1)

- Stone 1987Document16 pagesStone 1987Στέργιος ΚNo ratings yet

- Psychology Project 2016-2017: The Indian Community School, KuwaitDocument21 pagesPsychology Project 2016-2017: The Indian Community School, KuwaitnadirkadhijaNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research. AutismDocument17 pagesQualitative Research. AutismScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- 0883073817754006Document11 pages0883073817754006Paul AsturbiarisNo ratings yet

- Lozoff 2013Document7 pagesLozoff 2013sara vieiraNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Behaviour Therapy For Anxious Paediatric Dental Patients: A Systematic ReviewDocument10 pagesCognitive Behaviour Therapy For Anxious Paediatric Dental Patients: A Systematic ReviewSung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Ej 1271885Document13 pagesEj 1271885GEORGE OPIYONo ratings yet

- Autism Brief Nov 06Document13 pagesAutism Brief Nov 06Izhaan AkmalNo ratings yet

- Major Assignment-PSYC1160Document8 pagesMajor Assignment-PSYC1160Prisha SurtiNo ratings yet

- Orofacial Dysfunction Nonnutritive Sucking Hab 2022 American Journal of OrtDocument8 pagesOrofacial Dysfunction Nonnutritive Sucking Hab 2022 American Journal of OrtMario Ruiz RuizNo ratings yet

- Nitsbin I Medicine 2nd Edition Final Revised 1Document1,682 pagesNitsbin I Medicine 2nd Edition Final Revised 1Dawit g/kidanNo ratings yet

- ASCIA HP SPT Guide 2020 ReferencesDocument7 pagesASCIA HP SPT Guide 2020 ReferencesMuamar Ray AmirullahNo ratings yet

- Beauty Salon Client QuestionnaireDocument1 pageBeauty Salon Client QuestionnaireAlbert CostaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument4 pagesNursing Care Plan Rheumatoid ArthritisLighto RyusakiNo ratings yet

- DispensingDocument72 pagesDispensingxxtentacionloveNo ratings yet

- Doh Ao 2019-0031Document4 pagesDoh Ao 2019-0031Alex SanchezNo ratings yet

- Renal DiseasesDocument27 pagesRenal Diseasesمهند رياضNo ratings yet

- Collection, Transport and Storage of Specimens For Laboratory Diagnosis PDFDocument25 pagesCollection, Transport and Storage of Specimens For Laboratory Diagnosis PDFsutisnoNo ratings yet

- The Medical City ClarkDocument16 pagesThe Medical City ClarkPaopao Bacaling0% (1)

- Doctor Data For Pune Location 1Document14 pagesDoctor Data For Pune Location 1sadiq shaikhNo ratings yet

- IMG H1B ProgramsDocument4 pagesIMG H1B ProgramsDoctorJ5100% (1)

- BibliographyDocument4 pagesBibliographyapi-310438417No ratings yet

- Management of Paediatric Acute Mastoiditis: Systematic ReviewDocument9 pagesManagement of Paediatric Acute Mastoiditis: Systematic ReviewAldy GeriNo ratings yet

- Nhs Covid Pass - Vaccinated: Covid-19 Vaccine Astrazeneca Covid-19 Vaccine AstrazenecaDocument1 pageNhs Covid Pass - Vaccinated: Covid-19 Vaccine Astrazeneca Covid-19 Vaccine AstrazenecaSHWE LINo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesLovely Rose CedronNo ratings yet

- CPG Management of ThalassaemiaDocument100 pagesCPG Management of Thalassaemiamrace_amNo ratings yet

- Pressure Ulcer Prevention Report 130528Document358 pagesPressure Ulcer Prevention Report 130528Agung GinanjarNo ratings yet

- Lec 1-Fundamental Concepts of CHNDocument16 pagesLec 1-Fundamental Concepts of CHNGil Platon Soriano0% (1)

- 3.16.13-Letter To The Editor From Paul LiistroDocument1 page3.16.13-Letter To The Editor From Paul LiistroLisa BousquetNo ratings yet

- National Law Institute University, Bhopal: Economics - I Topic: Ayushman Bharat and ItsDocument18 pagesNational Law Institute University, Bhopal: Economics - I Topic: Ayushman Bharat and ItsAnay MehrotraNo ratings yet

- BSCN Collaborative Program - Year 1: Registration Tip Sheet 2021-2022Document1 pageBSCN Collaborative Program - Year 1: Registration Tip Sheet 2021-2022Ryan Christian PatriarcaNo ratings yet

- It Is All About Peri-Implant Tissue HealthDocument4 pagesIt Is All About Peri-Implant Tissue Healthkaue francoNo ratings yet

- No Reference Focus Design Result What Why How Purpose: Methods: Results: Conclusion Discussion ConclusionDocument2 pagesNo Reference Focus Design Result What Why How Purpose: Methods: Results: Conclusion Discussion ConclusionCongky 99No ratings yet

- Director ResponsibilitiesDocument4 pagesDirector ResponsibilitiesNeerja ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Tuberculous Meningitis: A Narrative ReviewDocument10 pagesTuberculous Meningitis: A Narrative ReviewVyom BuchNo ratings yet

- Professional Registration Classification Manual Vr.6Document38 pagesProfessional Registration Classification Manual Vr.6toplexil100% (1)

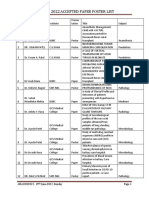

- Amacon2022-Accepted Paper Poster ListDocument35 pagesAmacon2022-Accepted Paper Poster ListViraj ShahNo ratings yet

- Resume - Afshin AghdasiDocument2 pagesResume - Afshin Aghdasimohammadrezahajian12191No ratings yet

- ADNICDocument2 pagesADNICTRTNo ratings yet

Autism and Paediatric Dentistry

Autism and Paediatric Dentistry

Uploaded by

Poli BMOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Autism and Paediatric Dentistry

Autism and Paediatric Dentistry

Uploaded by

Poli BMCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/333878974

Autism and Paediatric Dentistry: A Scoping Review

Article · January 2019

DOI: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a42665

CITATIONS READS

6 2,040

7 authors, including:

Juan Carlos Hernandez Cabanillas Josué Roberto Bermeo Escalona

Autonomous University of Baja California Universidad De La Salle Bajío

5 PUBLICATIONS 9 CITATIONS 18 PUBLICATIONS 62 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Amaury J Pozos-Guillen

Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí

211 PUBLICATIONS 2,947 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Efficacy of hypnosis in anxiety/pain reduction in children during pulpotomies. View project

Textile Functionalized Scaffold for Bone Regeneration View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Juan Carlos Hernandez Cabanillas on 10 July 2020.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Autism and Paediatric Dentistry: A Scoping Review

Mónica Herrera-Moncadaa / Phenélope Campos-Larab / Juan Carlos Hernández-Cabanillasc /

Josué Roberto Bermeo-Escalonad / Amaury Pozos-Guilléne / Fernando Pozos-Guillénf /

José Arturo Garrocho-Rangelg

Purpose: The objectives of this scoping review were: first, to pose a research question; second, to identify relevant

studies to answer the research question; third, to select and retrieve the studies; fourth, to chart the critical data;

and finally, to collate, summarise, and report the results from selected articles on the dental management of chil-

dren affected with autism.

Materials and Methods: Relevant articles (randomised controlled trials, reviews, observational studies, and clinical

case reports) published over an 11-year period were identified and retrieved from five internet databases: PubMed,

Embase/Ovid, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, and EBSCO.

Results: By title and abstract screening and after removing duplicates, 25 articles were finally included in the pres-

ent scoping review. According to the extracted data, the following four clinical issues were found to be most impor-

tant: patient behavioural control, prevalence/incidence of dental caries, adverse effects and interactions with

medications, and orthodontic management. Additionally, several useful clinical recommendations are provided.

Conclusions: Paediatric dentists should bear in mind that early diagnosis and treatment, effective communication

skills, and a long-term follow-up of children with autism continue to be the best approaches for achieving enhanced

patient psychological well-being and consequently a better quality of life.

Key words: autism, general management, paediatric dentistry, review

Oral Health Prev Dent 2019; 17: 203–210. Submitted for publication: 10.07.18; accepted for publication: 28.11.18

doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a42665

A utism spectrum disorder (ASD) is one of the most com-

mon worldwide lifelong neurobehavioural disabilities, in

which diverse behavioural/cognitive functions are severely

interactions, impaired communication abilities, and re-

stricted/repetitive behavioural attitudes and activi-

ties.10,12,21 ASD is a heterogeneous condition that im-

compromised.12,22 The spectrum comprises autism (or plies a combination of both genetic and environmental

‘classic autism’), Asperger syndrome, childhood disintegra- aetiological factors; for example, advanced maternal age

tive disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder-not has been suggested as involved in the pathophysiology

otherwise specified, which differ in the amount and severity of the disorder. The prevalence rate has been reported to

of clinical issues.10 range from 5.7 to 11.3 per 1000 (i.e. 1 in 88 children

Autism was first described in 1943 by Kanner,19 and aged 8 years), with a male:female ratio of 4.6:1 and no

is a disorder comprising characteristic impaired social ethnic predilection.6,10,19

a Resident, Paediatric Dentistry Postgraduate Program, Faculty of Dentistry, e Associate Professor, Paediatric Dentistry Postgraduate Program, Faculty of

San Luis Potosi University, San Luis Potosí, SLP, México. Identification of stud- Dentistry, San Luis Potosi University, San Luis Potosí, SLP, México. Study de-

ies, search and screening in electronic databases. sign and writing discussion.

b Associate Professor, Paediatric Dentistry Postgraduate Program, Faculty of f Associate Professor, Medicine Program, Multidisciplinary Unit, Zona Huasteca,

Dentistry, San Luis Potosi University, San Luis Potosí, SLP, México. Identifica- San Luis Potosi University, Cd. Valles, SLP, México. Identification of studies

tion of studies, search and screening in electronic databases. and writing discussion.

c Associate Professor, Faculty of Dentistry, Baja California University, Tijuana, g Associate Professor, Paediatric Dentistry Postgraduate Program, Faculty of

BC, México. Identification of studies, search and screening in electronic Dentistry, San Luis Potosi University, San Luis Potosí, SLP, México. Study de-

databases. sign, wrote and proofread the manuscript.

d Associate Professor, Faculty of Dentistry, La Salle University, León, Gto,

México. Identification of studies, search and screening in electronic Correspondence: Amaury Pozos-Guillén, Facultad de Estomatología, Universi-

databases. dad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, Av. Dr. Manuel Nava # 2, Zona Universitaria,

C.P.78290, San Luis Potosí, SLP. Mexico. Tel: +52-444-826-2300 x 5134;

e

-mail: apozos@uaslp.mx

Vol 17, No 3, 2019 203

Herrera-Moncada et al

Autism affects the limbic system and cerebellum during Identification of Relevant Studies

brain development in infancy and usually follows a steady To find potentially relevant articles, the electronic data-

course, without remission, through adulthood.18,19 As au- bases PubMed, EMBASE/Ovid, Cochrane Library, Google

tistic children have no dysmorphic characteristics or bio- Scholar, and EBSCO (Dentistry & Oral Science Source) were

logical markers, the diagnostic process is based on behav- searched. Only references published in the last 11 years

ioural criteria. 16 The disorder is confirmed through (June 2007 to June 2018), whose purpose was to identify

interviews with the parents or caregivers and psychological potential clinical needs in paediatric patients with autism,

testing.29 Clinically, it is mainly based on four specific cri- were screened. To be eligible for review, articles had to

teria and marked behaviour features: (i) early onset, prior meet the following criteria: randomised clinical trials, obser-

to 3 years of age; (ii) severe abnormal patterns of social vational studies (cohorts, case-control designs, cross-sec-

relationships; (iii) abnormal verbal and nonverbal commu- tional studies, and clinical case reports), or review articles

nication development; and (iv) evident manifestations of written in English or Spanish and focused on children and

restricted, repetitive, and stereotypical behaviour, interest, adolescents (aged 0-18 years) with autism in the field of

and imagination.10,21 paediatric dentistry. Gray literature, comments, editorials,

The disorder is frequently associated with sensory (e.g. short communications, and letters were excluded from the

auditory, visual, olfactory, tactile, or gustatory) deficits and/ review.

or mental disabilities, great dependence on the parents, A comprehensive literature search, electronic and man-

epilepsy, communication difficulties, unpredictable and un- ual, was conducted independently by three authors (MHM,

controlled body movements, and increased fear and anxi- PCL, and JCHC) to identify appropriate titles and abstracts.

ety.3,11,33 Additionally, autistic children commonly exhibit A search strategy was carefully implemented, employing

damaging oral habits, including tongue thrusting, bruxism, three major concepts: ‘autism’, ‘children and adolescents’,

lip biting, and soft tissue picking. Additionally, their prob- and ‘oral health care’. Several search/MeSH terms, key

lematic behavioural management may impede, change, or words, or synonyms were combined and appropriately

reduce access to oral health care, which places affected adapted for each database. Then, the chosen articles were

children at a higher risk for oral diseases.3,10,18 retrieved in full-text and were read and assessed by two

There is a paucity of studies in the dental literature that other experienced reviewers (JAGR and AJPG) separately for

address the fundamentals of dental management in autistic the final list of studies to be included. The reference lists of

paediatric patients, with inconsistent findings. This article selected articles were also screened to find other poten-

presents a scoping review on the oral health of children and tially eligible studies. Any discrepancy was discussed and

adolescents with autism and identifies their main oral care resolved by consensus with the aid of a third examiner

needs. (JRBE).

Data Extraction

MATERIALS AND METHODS Data from eligible studies were extracted and entered into a

predesigned and piloted standardised tracking and review

Design form to present a narrative account of the relevant literature

Scoping reviews are designed to examine the main body of and avoid overlapping. From each individual article, the fol-

available published evidence with a broad approach regard- lowing information was recorded: general characteristics (au-

ing a specific topic to identify the boundaries and the con- thors, year of publication, methodological design, study set-

text of that topic, as well as summarise the most important ting); patients’ clinical features (age, gender, medical status,

information and results of the studies included.5 The pres- level of mental/intellectual disability, oral status, etc); type

ent scoping review was carried out in accordance with that of oral management (e.g. diagnostic methods, oral-hygiene/

proposed by Arksey and O’Malley12 and Bragge et al.19 This preventive management, behavioural issues, treatment pro-

framework comprises five steps: (i) designing the research cedures); main outcome measured; key findings or conclu-

question; (ii) identifying relevant studies through a literature sions; and authors’ recommendations. A judgment concern-

search; (iii) analysing selected studies; (iv) extracting and ing whether each outcome was primarily clinician-centred

charting data; and (v) collating, summarising, and reporting was also performed. Thereafter, data were collected, de-

the results.25,28 tailed, cross-checked, summarised (in tables or charts), and

discussed accordingly. Additionally, the scoping review pro-

Research Question cess was structured as a flow diagram (Fig 1).

A research question was structured based on the PICO (Pa-

tient/Intervention/Comparison/Outcome) format to scope

the extent of research available on the clinical topic and to RESULTS

avoid the early exhaustion of literature during the search

process. The research questions was: For children and ado- We identified 139 studies of potential relevance. Follow-

lescents with autism, what are the principal oral health care ing removal of duplicates (n = 7), 132 articles were

necessities? screened in detail, and 40 of these were selected for

full-text review. Of these, 25 studies (24 in English and

204 Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry

Herrera-Moncada et al

Records identified through Additional records identified

Identification

database searching through manual search

(n = 126) (n = 13)

Records after duplicates removed

(n = 7)

Screening

Records screened Records excluded on relevance

(n = 132) (n = 92)

Full-text articles excluded, with reasons

Included

(n = 15)

Not related to children or adolescents

Full-text articles assessed for

eligibility Related to other disabilities different to

(n = 40) autism

Not directly related to oral care

Language other than English or Spanish

Eligibility

Studies included in

the scoping review

(n = 25)

Fig 1 Flow diagram of literature search.

one in Spanish) were published between 2007 and 2018 teractions; (iv) orthodontic management, and (v) additional

and included in the present scoping review. The entire clinical recommendations.

selection process is described in the flow diagram de-

picted in Fig 1. Additionally, Table 1 presents the general Behavioural Management

characteristics of the studies included in this scoping re- Communication skills, social-interaction abilities, and knowl-

view.1,3,8,9,10,11,14-18,20,21,23-27,29-36 The majority of the edge of behavioural control are essential when a paediatric

studies retrieved were conducted in the USA and were nar- dentist is concerned with modifying a child’s negative be-

rative reviews/guidelines. The remaining studies were origi- haviours.3,16,30,36 Disruptive behaviours typical of children

nal investigations: two systematic reviews, five ran- or adolescents with autism may significantly complicate

domised/nonrandomised controlled clinical trials, and five paediatric dental care and home dental care, both preven-

cross-sectional studies. After exploring the final selection of tive and rehabilitative, by endangering the patient’s safety

the studies, a large amount of relevant clinical information and placing the practitioner and her/his dental team at risk

was condensed. The main findings from this process are of injury. These patients exhibit a wide range of behavioural

listed in the discussion section. and understanding patterns: some of these patients are

verbally fluent with average cognitive activity, while others

do not speak or engage in frequent repetitive or self-injuri-

DISCUSSION ous behaviours.33 These conditions are frequently accom-

panied by hyperactivity, low frustration threshold, short at-

After reviewing the findings of the present scoping review, tention span, impulsivity, agitation, anger, exaggerated

five relevant clinical topics were considered of greatest in- reactions to light and odors, temper tantrums, and self-inju-

terest for paediatric dentistry practices during the manage- rious behaviours.8,30 Anxiety is increased because the pa-

ment of autistic children and adolescents: (i) behavioural tients are unable to express the fears or reservations that

management; (ii) caries prevalence/incidence; (iii) drug in- they experience at the thought of undergoing treatment.11

Vol 17, No 3, 2019 205

Herrera-Moncada et al

Table 1 List of studies included in the scoping review, with general characteristics and main findings

Author (year) Study design Topic Country Main findings

Namal et al27 RCT* Dental caries prevalence between Turkey Children with autistic disorder exhibited

(2007) autistic and normal children lower caries levels compared to non-affected

controls.

Morisaki et al26 Literature The TEACCH visual guide Japan/ TEACCH is a non-pharmacological behaviour

(2008) review and approach based on pictures, Canada guidance method successfully employed in

clinical case drawings, and boxes children with autism.

report

Gómez-Legorburu Literature Behaviour management of Spain The article describes the main protocols

et al14 (2009) review children with autism required to facilitate proper care during

dental visits.

Loo et al21 (2009) Cross- Factors associated with the use USA Uncooperative behaviour was associated

sectional of traditional behaviour with younger age and the presence of an

techniques, general anesthesia, additional diagnosis, and required advanced

and protective stabilisation in behavioural guidance techniques.

children with autism

Jaber18 (2011) RCT* Caries prevalence, periodontal United Arab Autistic children exhibited higher caries

problems, and other treatment Emirates prevalence, poor oral hygiene, and extensive

needs unmet oral needs.

Hernández and Literature Management techniques reported USA There are no evidence-based procedural

Ikkanda16 (2011) review in the dental/medical literature modifications that address the problematic

behaviour of autistic children in the dental

setting.

Olszewaska and Literature Orthodontic management of Poland Waiting time should not exceed 10-15

Dunin-Wilczyńska30 review children and adolescents with minutes. An attentive routine is

(2011) autism recommended, by maintaining the same

days, times, and dental staff for each dental

visit.

Rai et al31 (2012) Cross- Assessment of oral health status, India Similar dental caries status, poorer oral

sectional salivary pH, and total salivary hygiene, and lower salivary antioxidants

antioxidant concentration were detected.

Lai et al20 (2012) Cross- To identify dental needs and USA/ Main barriers detected were patient’s

sectional barriers to oral health care Singapore uncontrolled behaviour, cost, and lack of

through surveys insurance. Significant variables of unmet

needs were child’s behaviour/dental health

and caregiver’s last dental visit over

6 months ago.

Delli et al10 (2013) Literature Behavioural management of Netherlands/ Dental management of autistic children

review autistic children in the dental Switzerland requires in-depth understanding and

clinic knowledge of well-established behavioural

techniques, which should be implemented in

an individualised manner.

Stein et al33 RCT* Objective and physiological USA Physiological stress, measured by

(2014) measures of behaviour or distress nonspecific skin conductance response, is

in autistic patients highly correlated with manifest poor

behaviour in autistic children.

Udhya et al34 Literature Clinical characteristics, oral India Autistic children and adolescents do not

(2014) review health status, and dental display specific dental features. However,

management poor dental hygiene contributes to an

increased risk of caries and periodontal

problems.

Gupta15 (2014) Literature Oral conditions, epidemiology, Saudi Arabia An interdisciplinary approach including

review diagnosis, and medical psychotherapy, speech therapy, and parental

management. advice help paediatric dentists to manage

the behaviour of children with autism and

deliver optimal oral care.

Isong et al17 RCT* Efficacy of electronic-screen USA These electronic technologies are useful

(2014) media devices in the paediatric tools for reducing fear and lack of

dental office for reducing anxiety cooperation in autistic children.

and increasing compliance

206 Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry

Herrera-Moncada et al

Author (year) Study d

esign Topic Country Main findings

Nelson et al29 Literature Educational and behavioural USA Practitioners should take enough time to

(2015) review approaches understand and know affected patients,

thus applying appropriate principles of

learning and behavioural control.

Wibisono et al35 Cross- Evaluation of the use of dental Indonesia Pictures were easy to understand by the

(2016) sectional visit pictures in children and their patients. These visual tools were considered

parents through interviews successful as communication models for

children with autism.

Elmore et al11 Literature Articles assessing pictures, USA Sociocommunicative and behavioural

(2016) review recent electronic technologies techniques are the preferred approaches for

(videos and mobile applications), reducing dental anxiety in autistic children.

and socio-behavioural intervention Visual devices are potentially useful aids for

this purpose.

Marion et al24 RCT* Use of dental stories consisting USA Dental stories showed to be effective for

(2016) of photographs integrated with preparing both children and families for

text and videos to prepare the dental visits.

autistic patient for the dental

treatment

Mah and Tsang23 RCT* Efficacy of a visual schedule Canada The system has the potential to help autistic

(2016) system (pictures, communication children successfully complete each dental

symbols, or cues) during dental procedure step, with lower distress and in

appointments less time.

Bartolomé-Villar et Systematic Oral conditions of children with Spain No differences were found regarding the

al3 (2016) review autism spectrum disorder and prevalence of dental caries, oral habits,

children with sensory impairments malocclusions, and frequency of trauma;

only oral-hygiene status was considered

worse in autistic children.

da Silva et al8 Systematic To calculate the pooled Brazil/UK Seven included studies reported dental

(2017) review prevalence of dental caries and caries prevalence. Pooled prevalence was

periodontal disease in children or 60.6%. Pooled periodontal disease

young adults with autism prevalence was 69.4% (three studies).

spectrum disorder

Sadia-Fakhruddin RCT* ASD children were introduced to United Arab The use of audiovisual distraction

et al32 (2017) initial and dental non-invasive Emirates significantly decreased the mean heart rate.

treatment sessions with or There was no significant difference in oxygen

without the use cartoon movies, saturation levels between groups.

as visual distractors. Changes in

blood oxygen saturation and heart

rate were recorded

Dangulavanich et Cross- To evaluate the cooperation rates Thailand Patients aged 11-18 years who had

al9 (2017) sectional and the factors associated with attended special education programmes,

clinical behaviour during dental and who showed positive behaviour before

treatment in ASD children dental management, exhibited higher

cooperation during dental treatment.

Al-Sehaibany1 Prospective This study compared the Saudi Arabia The prevalence in ASD children was 87.3%

(2017) cohort study prevalence of oral habits between and in healthy patients 49.3%. The most

patients with ASD and healthy common habits among autistic children were

children over a 14-month period bruxism (54.7%), object biting (44.7%), and

mouth breathing (26.7%).

Zink et al36 (2018) RCT* To assess a novel electronic Brazil The developed app was more effective than

application (app) with the aim of the Picture Exchange Communication

facilitating the patient-dentist system; fewer attempts and appointments

communication among children were needed to accept the different dental

with ASD procedures delivered.

*Randomised clinical trial.

Vol 17, No 3, 2019 207

Herrera-Moncada et al

As a consequence, 60%-80% of dentists are unwilling to dictory results: some studies showed no significant differ-

manage autistic patients because of their poor behaviour ences between affected children and normal controls,

on the dental chair, the rate of which among affected chil- whereas others indicated a higher incidence among autistic

dren has been reported to be as high as 80% to 100%. An- children.3 On the other hand, three cross-sectional studies

other factor contributing the lack of cooperation of these evaluated caries prevalence in children or adolescents with

patients includes diminished sensory integration and pro- autism compared with nondisabled children as controls.

cessing as well as changes in the child’s daily routines.33 Jaber18 gathered 61 autistic participants aged 6 to

These anomalies represent an important barrier to dental 16 years (16 females and 45 males) who were compared

treatment.29,31 Many practitioners prefer to employ protec- with a non-autistic control group of 61 participants. Children

tive physical-immobilisation devices or pharmacologic ap- with autism had significantly higher numbers of decayed,

proaches, including sedation or general anaesthesia.33 missed, or filled teeth (77%) than controls (46%). Rai et

When indicated, physical restraint procedures should be al31 evaluated the oral health status of 101 affected chil-

employed with strict, appropriate precautions regarding un- dren and 50 normal healthy siblings as controls between 6

usual body movements, particularly in autistic patients with and 12 years of age; no significant difference was observed

a history of seizures, to keep the patient from harm and in the dental-caries status of the autistic group and the con-

always after obtaining parental consent.21 Diverse behav- trol group. Finally, Namal et al27 examined 61 Turkish autis-

ioural guidance techniques specific to autistic paediatric tic and 301 normal children between the ages of 6 and

patients have been recently suggested and discussed.10,11, 12 years to assess and compare their caries. These au-

13,15,17,18,21,23,24,35 These techniques include, for example, thors concluded that patients without the disorder had a

the presence of parents, the ‘tell-show-do’ method with higher caries prevalence than those with autism (odds ratio,

brief and specific commands, short dental visits, sensory OR = 3.99; 95% CI = 1.56, 10.19). However, the authors

integration, gradual desensitisation, positive/negative ver- considered that the autistic sample studied was not com-

bal reinforcement, and the use of audiovisual distractors. pletely representative of the population because the major-

These approaches, alone or in combination, should be per- ity of these patients were selected from families with ac-

sonalised and based on specific, individual needs. cess to education and special care.

Patients with autism are characterised as visual learners

because they possess neuropsychological features that pro- Drug Interactions and Adverse Effects

mote the preference for strongly processing visual informa- Many drugs prescribed chronically by psychiatrists to man-

tion or stimuli over other sensory channels, such as hear- age autism-associated symptoms have adverse effects and

ing.9,17 Recent investigations have supported the use of interactions with medication used in clinical paediatric den-

easy-to-understand visual approaches (e.g. pictures, draw- tistry.12 For example, for treating hyperactivity, autistic chil-

ings, videos, or electronic mobile applications), combined dren are managed with central nervous system (CNS) stimu-

with traditional behavioural control methods, to improve lants (Methylphenidate) or antihypertensives (Clonidine); for

the cooperation level of autistic children or adolescents repetitive behaviours, medication is based on antidepres-

and facilitate positive dental visits.11,23,26,32,36 For exam- sants (Fluoxetine or Sertraline); and, in cases of aggressive

ple, low anxiety levels have been reported when patients patterns, anticonvulsants (Carbamazepine or Valproate) or

with autism previously watched a video of other children antipsychotics (Olanzapine or Riperidone) are adminis-

undergoing a dental procedure.23 Similarly, Zink et al36 tered.12 Thus, it is imperative for practitioners to be familiar

developed an app for facilitating the communication pro- with the pharmacological properties of these psychotropic

cess between autistic paediatric patients and practition- drugs.15

ers, with fewer dental visits required for clinical examina- Similarly, in the practice of paediatric dentistry, pharma-

tions and preventive dental care. Additionally, the TEACCH cological approaches employed for pain and anxiety control

visual guide approach to controlling a child’s behaviour in autistic children and adolescents have been classified as

and promoting home daily routines is widely recommended conscious (oral, inhalatory, intramuscular, or intravenous

by Morisaki et al.26 Thus, these modeling/communication sedation) and unconscious methods (deep sedation and

tools have been demonstrated to be effective and practical general anaesthesia).7 Although these approaches are use-

in the paediatric clinical setting for engaging, teaching, and ful tools that are often necessary, they are not absolutely

motivating patients with autism, reducing fear, and increas- safe or effective and incur additional costs. Although rare,

ing compliance for routine oral examinations or dental pro- some associated health risks, adverse effects, and compli-

cedures.17 cations have been reported in the dental literature when

sedatives or general anaesthesia are administered in men-

Caries Prevalence and Incidence tally challenged children (Table 2).12,15

A systematic review, or meta-analysis, carried out by da

Silva et al8 included seven relevant studies that reported Orthodontic Management

the caries prevalence in autistic children and young adults; Malocclusions occur more frequently in mentally challenged

the pooled prevalence reported in this meta-analysis was children, which may compromise several oral functional as-

60.6% (95% confidence interval = 44.0, 75.1). A second pects and create adaptive alterations in chewing, swallow-

systematic review by Bartolomé-Villar et al3 reported contra- ing, and language. In this regard, Al-Sehaibany1 reported

208 Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry

Herrera-Moncada et al

that the prevalence of harmful oral habits (e.g. bruxism, Table 2 Potential adverse effects associated with the

object biting, thumb sucking/biting, and mouth breathing) use of sedation or general anaesthesia in autistic chil-

was almost twice as high in ASD patients as in healthy chil- dren (taken and adapted from Gupta15 and Elmore et al11

dren, thus contributing to an increased occurrence of dental

malocclusions. On the other hand, only one article could be Sedation General anaesthesia

retrieved that addresses the orthodontic management of an Xerostomia Heart attack

autistic patient.30 As in other dental fields, behavioural con- Sialorrhea Stroke

trol is the main problem encountered when orthodontically Dysphagia Allergic reaction

Stomatitis Temporary mental confusion

treating autistic children and adolescents. Thus, when de- Glossitis Lung infection

signing the treatment plan, the orthodontist should estab- Bruxism Damage to the vocal cords

lish individual and short-term objectives on a step-by-step Body pain/headache Waking during anesthesia

basis. This plan can be reassessed and modified after the Sinusitis Death

completion of each step, according to the patient’s behav-

ioural evolution. Perfection is not usually an achievable goal

in these children, but therapeutic efforts should be at-

tempted to improve their occlusion. More difficult proced-

ures in orthodontics for autistic patients are impression

taking and bracket bonding. Diverse behavioural control ap- limitations of the present study were the high heterogeneity

proaches have been recommended for performing these of the detected articles, our limited ability to consistently

and other difficult tasks, ranging from conductive guidance summarise details of the extracted data or findings, and

or educational intervention techniques alone to pharmaco- the difficulties in assigning outcomes to specific domains.

logical sedation and general anaesthesia. More research effort is necessary to assist paediatric den-

tistry practitioners in achieving more effective oral health

Additional Recommendations care for ASD children and adolescents, provide improved

Various authors10,11,14-16,18,21,29,33,34 have made different dental experiences for ASD patients and, as a consequence,

clinical and practical recommendations for better dental to contribute to a better quality of life for ASD patients. Cur-

management of autistic children and adolescents. The rent and future research should be especially focused on

most important ones are: (i) signs of physical abuse should optimising behaviour control management prior to and during

be looked for during the extraoral and intraoral examination, the dental treatment of this vulnerable population.

for example, oral traumas; (ii) mouth guards are adequate

for patients with severe bruxism or a self-injurious pattern;

(iii) powered toothbrushes may be appropriate and well-tol- CONCLUSIONS

erated but require some training; (iv) the dental light and

instruments should be kept away from the dental chair; The present scoping review collated and condensed the

(v) sensory stimuli such as sounds or odors that may dis- major clinical recommendations reported in the relevant

tract the patient should be reduced; (vi) interruptions paediatric dentistry literature published over the last

should be avoided and only the necessary assistants 11 years regarding the best approaches for proper dental

should be present in the operatory room; and (vii) the management of children and adolescents with ASD in a

child’s limited tolerance for physical contact should always non-threatening environment.

be considered. It is crucial that paediatric patients with ASD be intro-

duced to dental treatment in an adaptive and progressive

Limitations manner to desensitise their enhanced visual, auditory, and

Unlike systematic reviews, scoping reviews do not incorpo- tactile sensations. Individually designed behavioural tech-

rate a quality assessment of the studies included. This niques, for instance, an adequate verbal approach and the

scoping review was aimed at collecting useful clinical infor- use of diverse visual distractors, can help affected children

mation that is available and easily accessible to help clin- cope with dental stressors and exhibit an acceptable coop-

icians during the management of children and adolescents eration level, with less anxiety and apprehension in the clin-

with autism. Through this approach, we intended to define ical setting.

the scope of the literature relevant to this topic. However,

as with any scoping review, a likely publication bias was

present due to the selection of studies conducted only in REFERENCES

English- or Spanish-speaking countries, primarily due to lim-

ited resources for translation. Furthermore, the article 1. Al-Sehaibany FS. Occurrence of oral habits among preschool children with

autism spectrum disorder. Pak J Med Sci 2017;33:1156–1160.

search was restricted to an 11-year period; thus, our refer- 2. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological frame-

ence screening might have been underrepresented. How- work. Int J Soc Res Method 2005;8:19–32.

ever, we are confident that a significant number of studies 3. Bartolomé-Villar B, Mourelle-Martínez MR, Diéguez-Pérez M, de Nova-Gar-

cía MJ. Incidence of oral health in paediatric patients with disabilities:

included herein provided an overview and useful information Sensory disorders and autism spectrum disorder. Systematic review II. J

on the oral health care of autistic paediatric patients. Other Clin Exp Dent 2016 8:e344–e351.

Vol 17, No 3, 2019 209

Herrera-Moncada et al

4. Bragge P, Clavisi O, Turner T, Tavender E, Collie A, Gruen RL. The Global 20. Lai B, Milano M, Roberts MW, Hooper SR. Unmet dental needs and barri-

Evidence Mapping Initiative: Scoping research in broad topic areas. BMC ers to dental care among children with autism spectrum disorder. J Au-

Med Res Methodol 2011;11:92. tism Dev Disord 2012;42:1294–1303.

5. Castro-Codesal ML, Dehaan K, Featherstone R, Bedi PK, Bedi PK, Marti- 21. Loo CY, Graham RM, Hughes CV. Behavior guidance in dental treatment

nez Carrasco C, Katz SL, et al. Long-term non-invasive ventilation thera- of patients with autism spectrum disorder. Int J Paediatr Dent 2009;

pies in children: A scoping review. Sleep Med Rev 2018;37:148–158. 19:390–398.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Mental health in the 22. Lu YY, Wei IH, Huang CC. Dental health - a challenging problem for a pa-

United States: Parental report of diagnosed autism in children aged 4-17 tient with autism spectrum disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013;35:214.

years – United States, 2003-2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2006 e1–e3.

55:481–486. 23. Mah JW, Tsang P. Visual schedule system in dental care for patients with

7. Chaushu S, Becker A. Behavior management needs for the orthodontic autism: A pilot study. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2016;40:393–399.

treatment of children with disabilities. Eur J Orthod 2000;22:143–149. 24. Marion IW, Nelson TM, Sheller B, McKinney CM, Scott JM. Dental stories

8. da Silva SN, Gimenez T, Souza RC, Mello-Moura ACV, Raggio DP, Morim- for children with autism. Spec Care Dentist 2016;36:181–186.

oto S, et al. Oral health status of children and young adults with autism 25. McKenzie K, Martin L, Ouellette-Kuntz H. Frailty and intellectual and devel-

spectrum disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Paediatr opmental disabilities: a scoping review. Can Geriatr J 2016;19:103–112.

Dent 2017;27:388–398.

26. Morisaki I, Ochiai TT, Akiyama S, Murakami J, Friedman CS. Behavior

9. Dangulavanich W, Limsomwong P, Mitrakul K, Asvanund Y, Arunakul M. guidance in dentistry for patients with autism spectrum disorder using a

Factors associated with cooperative levels of autism spectrum disorder structured visual guide. J Disabil Oral Health 2008;9:136–140.

children during dental treatments. Eur J Paediatr Dent 2017;18:231–236.

27. Namal N, Vehit HE, Koksal S. Do autistic children have higher levels of

10. Delli K, Reichart PA, Bornstein MM, Livas C. Management of children with caries? A cross-sectional study in Turkish children. J Indian Soc Pedod

autism spectrum disorder in the dental setting: Concerns, behavioural Prev Dent 2007;25:97–102.

approaches and recommendations. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal

28. Naseem M, Shah AH, Khiyani MF, Khurshid Z, Zafar MS, Gulzar S, et al.

2013;18:e862–e868.

Access to oral health care services among adults with learning disabili-

11. Elmore JL, Bruhn AM, Bobzien JL. Interventions for the reduction of den- ties: A scoping review. Ann Stomatol (Roma) 2017;7:52–59.

tal anxiety and corresponding behavioral deficits in children with autism

29. Nelson TM, Sheller B, Friedman CS, Bernier S. Educational and therapeu-

spectrum disorders. J Dent Hyg 2016;90:111–120.

tic behavioral approaches to providing dental care for patients with au-

12. Friedlander AH, Yagiela JA, Paterno VI, Mahler ME. The neuropathology, tism spectrum disorder. Spec Care Dentist 2015 35:105–113.

medical management and dental implications of autism. J Am Dent

30. Olszewaska K, Dunin-Wilczyńska I. Orthodontic management of children

Assoc 2006;137:1517–1527.

with autism – Review of the literature. Dent Med Probl 2011;48:459–463.

13. Ghandi RP, Klein U. Autism spectrum disorders: An update on oral health

31. Rai K, Hedge AM, Jose N. Salivary antioxidants and oral health in chil-

management. J Evid Based Dent Prac 2014;14(Suppl):115–126.

dren with autism. Arch Oral Biol 2012;57:1116–1120.

14. Gómez-Legorburu B, Badillo-Perona V, Martínez-Pérez EM, Planells-del

32. Sadia-Fakhruddin K, Yehia-El Batawi H. Effectiveness of audiovisual dis-

Pozo P. Intervención odontológica actual en niños con autismo. Cient

traction in behavior modification during dental caries assessment and

Dent 2009;6:207–215.

sealant placement in children with autism spectrum disorder. Dent Res J

15. Gupta M. Oral health status and dental management considerations in (Isfahan) 2017;14:177–182.

autism. Int J Contemp Dent Med Rev 2014;2014:011114.

33. Stein LI, Lane CJ, Williams ME, Dawson ME, Polido JC, Cermak SA. Physio-

16. Hernández P, Ikkanda Z. Applied behavior analysis: behavior manage- logical and behavioral stress and anxiety in children with autism spectrum

ment of children with autism spectrum disorders in dental environments. disorders during routine oral care. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014: 694876.

J Am Dent Assoc 2011;142:281–287.

34. Udhya J, Varadharaja MM, Parthiban J, Srinivasan I. Autism Disorder (AD): An

17. Isong IA, Rao SR, Holifield C, Iannuzzi D, Hanson E, Ware J, et al. Ad- updated review for paediatric dentists. J Clin Diagn Res 2014;8:275–279.

dressing dental fear in children with autism espectrum disorders: A ran-

35. Wibisono WL, Suharsini M, Wiguna T, Sudiroatmodjo B, Budiardjo SB, Au-

domized controlled pilot study using electronic screen media. Clin Pediatr

erkari EI. Perception of dental visit pictures in children with autism spec-

(Phila) 2014;53:230–237.

trum disorder and their caretakers: A qualitative study. J Int Soc Prev

18. Jaber MA. Dental caries experience, oral health status and treatment Community Dent 2016;6:359–365.

needs of dental patients with autism. J Appl Oral Sci 2011;19:212–217.

36. Zink AG, Molina EC, Diniz MB, Santos MTBR, Guaré RO. Communication

19. Klein U, Nowak AJ. Autistic disorder: A review for the pediatric dentist. application for use during the first dental visit for children and adoles-

Pediatr Dent 1998 20:312–317. cents with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatr Dent 2018;40:18–22.

210 Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry

View publication stats

You might also like

- Barbaro & Dissanayake (2010) - SACS PDF FINAL PDFDocument10 pagesBarbaro & Dissanayake (2010) - SACS PDF FINAL PDFAnonymous 75M6uB3Ow100% (1)

- PDHPE HSC Revision Questions 2010-18Document83 pagesPDHPE HSC Revision Questions 2010-18Jusnoor KAURNo ratings yet

- Practice Parameter For The Assessment andDocument21 pagesPractice Parameter For The Assessment andBianca curveloNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Problems and Emotional Stress in Children With BruxismDocument7 pagesBehavioral Problems and Emotional Stress in Children With Bruxismjeremy ludwigNo ratings yet

- Influence of Head and Linear GrowthDocument10 pagesInfluence of Head and Linear GrowthAMILA YASHNI MAULUDI ABDALLNo ratings yet

- MSC Child and Adolescent Psychology Psyc 1107 Advanced Research Methods For Child Development M01Document10 pagesMSC Child and Adolescent Psychology Psyc 1107 Advanced Research Methods For Child Development M01macapashaNo ratings yet

- Sensory Features in Autism, 2022Document10 pagesSensory Features in Autism, 2022chayah8lichtigNo ratings yet

- Relacion Entre Caries Dental y El Ambito FamiliarDocument12 pagesRelacion Entre Caries Dental y El Ambito FamiliarDEYBI JOSSUE PALACIOS VARONANo ratings yet

- Guia de Buenas Practicas para La Investigacion de Los TEA (CARLOS III) 7pDocument7 pagesGuia de Buenas Practicas para La Investigacion de Los TEA (CARLOS III) 7pJulio César Valdez LizárragaNo ratings yet

- Family Burden and Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders - Perspective of Caregivers - Misquiatti, Brito, Schmidtt & Assumpção (2015)Document9 pagesFamily Burden and Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders - Perspective of Caregivers - Misquiatti, Brito, Schmidtt & Assumpção (2015)eaguirredNo ratings yet

- Orthodontics/Craniofacial Growth and Development Oral PresentationDocument14 pagesOrthodontics/Craniofacial Growth and Development Oral PresentationAnye PutriNo ratings yet

- Issn: Issn: Papeles@correo - Cop.esDocument9 pagesIssn: Issn: Papeles@correo - Cop.esSidra iftikharNo ratings yet

- Trayectorias de Desarrollo Lingüístico en Niños Con AutismoDocument9 pagesTrayectorias de Desarrollo Lingüístico en Niños Con AutismoNatalia Castro MartinezNo ratings yet

- Review Systematic Review of The Literature On Characteristics of Late-Talking ToddlersDocument29 pagesReview Systematic Review of The Literature On Characteristics of Late-Talking ToddlersTiara Maharani HarahapNo ratings yet

- Sensory Profile in Children With Autism Disorder and ChildrenDocument9 pagesSensory Profile in Children With Autism Disorder and ChildrenCarolinaNo ratings yet

- Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder HandoutDocument2 pagesFetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Handoutapi-753995548No ratings yet

- Dysphonia in Children: Journal of Voice: Official Journal of The Voice Foundation July 2012Document5 pagesDysphonia in Children: Journal of Voice: Official Journal of The Voice Foundation July 2012Nexi anessaNo ratings yet

- Racial Ethnic DisparitesDocument8 pagesRacial Ethnic Disparitesto.urbinasantanaNo ratings yet

- Emotional Distress Resilience and Adaptability A Qualitative Study of Adults Who Experienced Infant AbandonmentDocument18 pagesEmotional Distress Resilience and Adaptability A Qualitative Study of Adults Who Experienced Infant AbandonmentLoredana Pirghie AntonNo ratings yet

- Stein Cermak2012OralcareexperiencesinASDDocument6 pagesStein Cermak2012OralcareexperiencesinASDzsazsa nissaNo ratings yet

- DisfoniaDocument5 pagesDisfoniaRosario Crisóstomo PinochetNo ratings yet

- Autism Spectrum Disorders: Advances in Understanding and Intervention StrategiesDocument7 pagesAutism Spectrum Disorders: Advances in Understanding and Intervention StrategiesRoman ClaudiaNo ratings yet

- Effectsof Early NeglectonlanguageandcognitionDocument9 pagesEffectsof Early NeglectonlanguageandcognitionFARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- Prof Ed - Child and AdolescentDocument4 pagesProf Ed - Child and AdolescentLindesol SolivaNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Early DiagnoDocument11 pagesThe Importance of Early Diagnoiuliabucur92No ratings yet

- Connor 41Document7 pagesConnor 41cta.catalunya8652No ratings yet

- Education by GeneticsDocument6 pagesEducation by Geneticschagula3468100% (1)

- Oct 2016Document6 pagesOct 2016End Semester Theory Exams SathyabamaNo ratings yet

- Children and Youth Services ReviewDocument7 pagesChildren and Youth Services ReviewNerea F GNo ratings yet

- 5 - Perry, R.E. - 2018Document20 pages5 - Perry, R.E. - 2018João PedroNo ratings yet

- Dental Caries and Oral Health Related Quality of Life of 3 Year Olds Living in Lima, PeruDocument9 pagesDental Caries and Oral Health Related Quality of Life of 3 Year Olds Living in Lima, PeruFrancelia Quiñonez RuvalcabaNo ratings yet

- Communication Disorders and Emotional/Behavioral Disorders in Children and AdolescentsDocument15 pagesCommunication Disorders and Emotional/Behavioral Disorders in Children and AdolescentsIamDong BajNo ratings yet

- tmpB80D TMPDocument8 pagestmpB80D TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Autism Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesAutism Literature Reviewnaneguf0nuz3100% (1)

- Autism Thesis PaperDocument5 pagesAutism Thesis PaperWebsiteThatWritesPapersForYouCanada100% (2)

- Autism Literature Review ExampleDocument6 pagesAutism Literature Review Exampleafmzadevfeeeat100% (1)

- Literature Review Example On AutismDocument5 pagesLiterature Review Example On Autismafmzsgbmgwtfoh100% (1)

- Programa Integral para La Enseñanza de Habilidades A Niños Con AutismoDocument12 pagesPrograma Integral para La Enseñanza de Habilidades A Niños Con AutismoCeleste InleNo ratings yet

- (2007) Ar. Grigorenko - How Can Genomics InformDocument8 pages(2007) Ar. Grigorenko - How Can Genomics InformJulián A. RamírezNo ratings yet

- An Anthropological Approach Exposed Pesticides: The Evaluation of Preschool Children in MexicoDocument7 pagesAn Anthropological Approach Exposed Pesticides: The Evaluation of Preschool Children in MexicoJhonnyNogueraNo ratings yet

- DownloadDocument8 pagesDownloadzhaba vonNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Parental Quality of Life Following An Autism Diagnosis For Their ChildrenDocument7 pagesAn Analysis of Parental Quality of Life Following An Autism Diagnosis For Their ChildrenInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka Proforma For Registration For Subject For DissertationDocument20 pagesRajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka Proforma For Registration For Subject For DissertationAsha JiluNo ratings yet

- 2020 - Brancher - Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Problemsand Parent-Reported Sleep Bruxism InschoolchildrenDocument7 pages2020 - Brancher - Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Problemsand Parent-Reported Sleep Bruxism InschoolchildrenCarmo AunNo ratings yet

- Autism Journal ReflectionDocument6 pagesAutism Journal ReflectionLockon StratosNo ratings yet

- Autism, Therapy and COVID-19Document10 pagesAutism, Therapy and COVID-19Antonella CavallaroNo ratings yet

- HHS Public AccessDocument22 pagesHHS Public AccessDennis MejiaNo ratings yet

- Original Research Article: ISSN: 2230-9926Document4 pagesOriginal Research Article: ISSN: 2230-9926williamNo ratings yet

- Oral Health-Related Quality of Life of Schoolchildren: Impact of Clinical and Psychosocial VariablesDocument8 pagesOral Health-Related Quality of Life of Schoolchildren: Impact of Clinical and Psychosocial VariablesJuliana MoroNo ratings yet

- Introduction For A Research Paper On AutismDocument7 pagesIntroduction For A Research Paper On Autismh015trrr100% (1)

- Stone 1987Document16 pagesStone 1987Στέργιος ΚNo ratings yet

- Psychology Project 2016-2017: The Indian Community School, KuwaitDocument21 pagesPsychology Project 2016-2017: The Indian Community School, KuwaitnadirkadhijaNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research. AutismDocument17 pagesQualitative Research. AutismScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- 0883073817754006Document11 pages0883073817754006Paul AsturbiarisNo ratings yet

- Lozoff 2013Document7 pagesLozoff 2013sara vieiraNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Behaviour Therapy For Anxious Paediatric Dental Patients: A Systematic ReviewDocument10 pagesCognitive Behaviour Therapy For Anxious Paediatric Dental Patients: A Systematic ReviewSung Soon ChangNo ratings yet

- Ej 1271885Document13 pagesEj 1271885GEORGE OPIYONo ratings yet

- Autism Brief Nov 06Document13 pagesAutism Brief Nov 06Izhaan AkmalNo ratings yet

- Major Assignment-PSYC1160Document8 pagesMajor Assignment-PSYC1160Prisha SurtiNo ratings yet

- Orofacial Dysfunction Nonnutritive Sucking Hab 2022 American Journal of OrtDocument8 pagesOrofacial Dysfunction Nonnutritive Sucking Hab 2022 American Journal of OrtMario Ruiz RuizNo ratings yet

- Nitsbin I Medicine 2nd Edition Final Revised 1Document1,682 pagesNitsbin I Medicine 2nd Edition Final Revised 1Dawit g/kidanNo ratings yet

- ASCIA HP SPT Guide 2020 ReferencesDocument7 pagesASCIA HP SPT Guide 2020 ReferencesMuamar Ray AmirullahNo ratings yet

- Beauty Salon Client QuestionnaireDocument1 pageBeauty Salon Client QuestionnaireAlbert CostaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument4 pagesNursing Care Plan Rheumatoid ArthritisLighto RyusakiNo ratings yet

- DispensingDocument72 pagesDispensingxxtentacionloveNo ratings yet

- Doh Ao 2019-0031Document4 pagesDoh Ao 2019-0031Alex SanchezNo ratings yet

- Renal DiseasesDocument27 pagesRenal Diseasesمهند رياضNo ratings yet

- Collection, Transport and Storage of Specimens For Laboratory Diagnosis PDFDocument25 pagesCollection, Transport and Storage of Specimens For Laboratory Diagnosis PDFsutisnoNo ratings yet

- The Medical City ClarkDocument16 pagesThe Medical City ClarkPaopao Bacaling0% (1)

- Doctor Data For Pune Location 1Document14 pagesDoctor Data For Pune Location 1sadiq shaikhNo ratings yet

- IMG H1B ProgramsDocument4 pagesIMG H1B ProgramsDoctorJ5100% (1)

- BibliographyDocument4 pagesBibliographyapi-310438417No ratings yet

- Management of Paediatric Acute Mastoiditis: Systematic ReviewDocument9 pagesManagement of Paediatric Acute Mastoiditis: Systematic ReviewAldy GeriNo ratings yet

- Nhs Covid Pass - Vaccinated: Covid-19 Vaccine Astrazeneca Covid-19 Vaccine AstrazenecaDocument1 pageNhs Covid Pass - Vaccinated: Covid-19 Vaccine Astrazeneca Covid-19 Vaccine AstrazenecaSHWE LINo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesLovely Rose CedronNo ratings yet

- CPG Management of ThalassaemiaDocument100 pagesCPG Management of Thalassaemiamrace_amNo ratings yet

- Pressure Ulcer Prevention Report 130528Document358 pagesPressure Ulcer Prevention Report 130528Agung GinanjarNo ratings yet

- Lec 1-Fundamental Concepts of CHNDocument16 pagesLec 1-Fundamental Concepts of CHNGil Platon Soriano0% (1)

- 3.16.13-Letter To The Editor From Paul LiistroDocument1 page3.16.13-Letter To The Editor From Paul LiistroLisa BousquetNo ratings yet

- National Law Institute University, Bhopal: Economics - I Topic: Ayushman Bharat and ItsDocument18 pagesNational Law Institute University, Bhopal: Economics - I Topic: Ayushman Bharat and ItsAnay MehrotraNo ratings yet

- BSCN Collaborative Program - Year 1: Registration Tip Sheet 2021-2022Document1 pageBSCN Collaborative Program - Year 1: Registration Tip Sheet 2021-2022Ryan Christian PatriarcaNo ratings yet

- It Is All About Peri-Implant Tissue HealthDocument4 pagesIt Is All About Peri-Implant Tissue Healthkaue francoNo ratings yet

- No Reference Focus Design Result What Why How Purpose: Methods: Results: Conclusion Discussion ConclusionDocument2 pagesNo Reference Focus Design Result What Why How Purpose: Methods: Results: Conclusion Discussion ConclusionCongky 99No ratings yet

- Director ResponsibilitiesDocument4 pagesDirector ResponsibilitiesNeerja ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Tuberculous Meningitis: A Narrative ReviewDocument10 pagesTuberculous Meningitis: A Narrative ReviewVyom BuchNo ratings yet

- Professional Registration Classification Manual Vr.6Document38 pagesProfessional Registration Classification Manual Vr.6toplexil100% (1)

- Amacon2022-Accepted Paper Poster ListDocument35 pagesAmacon2022-Accepted Paper Poster ListViraj ShahNo ratings yet

- Resume - Afshin AghdasiDocument2 pagesResume - Afshin Aghdasimohammadrezahajian12191No ratings yet

- ADNICDocument2 pagesADNICTRTNo ratings yet