Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Through The Looking Glass Explorations in Transference and Countertransference

Through The Looking Glass Explorations in Transference and Countertransference

Uploaded by

Doru PatruOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Through The Looking Glass Explorations in Transference and Countertransference

Through The Looking Glass Explorations in Transference and Countertransference

Uploaded by

Doru PatruCopyright:

Available Formats

Transactional Analysis Journal

ISSN: 0362-1537 (Print) 2329-5244 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rtaj20

Through the Looking Glass: Explorations in

Transference and Countertransference

Petrūska Clarkson

To cite this article: Petrūska Clarkson (1991) Through the Looking Glass: Explorations in

Transference and Countertransference, Transactional Analysis Journal, 21:2, 99-107, DOI:

10.1177/036215379102100205

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1177/036215379102100205

Published online: 28 Dec 2017.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 12

View related articles

Citing articles: 6 View citing articles

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rtaj20

Through the Looking Glass:

Explorations in Transference and

Countertransference

Petruska Clarkson

Abstract biguities, and connotational disputes. The

This article reviews both narrow and number of ' 'types" of transference and related

broad definitions of transference and ~~~Mal~~reasem~reased~n~g

countertransference and provides a map of on the author and the method of classification

how these definitions can be understood in used. It is this author's view that apparent

terms of transactional analysis. It briefly dif- theoretical inconsistencies are often the result

ferentiates four categories: (1) what the pa- of confusion about definitions, which are herein

tient brings to the relationship (pro-active reviewed. This article presents a practical map

transference), (2) what the psychotherapist for use by transactional analysts and other

brings (pro-active countertransference or psychotherapists. It is effective when used as

therapist transference-pathological, (3) a tool in supervision (from self or supervisor)

what the psychotherapist reacts to in the pa- and not as an analytic disturbance to the

tient (reactive countertransference-induc- development of the transference modality in the

tive), and (4) what the patient reacts to as psychotherapeutic relationship. Of course, the

a result of what the therapist brings (client- map is not the territory. However, it has been

countertransference or reactive transfer- found effective for planning or anticipating

ence). Any of these may fonn the basis for directions in treatment or helping the

facilitative or destructive psychotherapeutic psychotherapist understand the situation better

outcomes. when there are intractable difficulties or

unrelenting plateaus.

Transference, of course, is only one of

In both Greek and Latin the word trans- several therapeutic relationshipspotentiallypre-

ference means "to carry across." The sent between patient and therapist in

phenomenon of "carrying across" qualities psychotherapy. It is to be differentiated from

from what is known (based on past experience) the working alliance, the reparative/

to what is analogous in the present has probably developmentally needed relationship, the real

always been a feature of human psychology. (I-You) relationship, and the transpersonal rela-

Such processes occur between husband and tionship (Clarkson, 1990).

wife, teacher and pupil, citizen and state func-

tionary. Thus, it is important to recognize that Transference Phenomena-

transference and countertransference in this Definitions and Types

sense are ubiquitous and necessary components In Freudian psychoanalysis transference was

of any learning process. They occur whenever originally regarded as an unfortunate

emotions, perceptions, or reactions are based phenomenon which interfered with psycho-

on past experiences rather than on the analysis (Freud, 1912/1958). Later, however,

here-and-now. Freud (1920/1955) saw it as an essential part

The subject of transference involves an of the psychotherapeutic process and indeed

astonishing variety of contradictions, am- one of the cornerstones of psychoanalytic prac-

tice. Fairbairn (1952), Klein (1984), and Win-

Thisarticle is an abbreviatedsegmentofa chapter (writ-

ten in spring. 1988) from a book: Transactional Analysis:

nicott (1975) assumed that patients' responses

An Integrative Approach, by Petruska Clarkson, published in the transference relationship were valid

by Routledge, 1991. evidence on which to base their theories about

Vol. 21, No.2, April 1991 99

PETRUSKA CLARKSON

the origin of object relations in infancy. triadic or group transferences.

Transference is one of the primary

Definitions of Transference mechanisms by which human beings learn from

Rycroft (1983) defined transference as: their past relationships to anticipate how to

The process by which a patient displaces behave in future relationships. For many peo-

on to his analyst feelings, ideas, etc., ple past object relationships have been

which derive from previous figures in his traumatic or strained (Pine, 1985), and they

life; by which he relates to the analyst as carry the pattern of these learned relationships

though he were some former object in his into their present lives and future as well as into

life; by which he projects on to his the psychotherapeutic relationship. Therefore,

analyst object-representations acquired until the transference is resolved, the an-

by earlier introjections; by which he en- ticipated other remains psychologically un-

dows the analyst with the significance of changed as the script process unfolds outside

another, usually prior, object. 2. The of Adult awareness.

state of mind produced by 1 in the pa- The decisive part of the work is achieved

tient. 3. Loosely, the patient's emotional by creating in the patient's relation to the

attitude towards his analyst. (Rycroft, doctor-in the "transference"-new edi-

1983, p. 168) tions of the old conflicts; in these the pa-

According to Racker (1968/1982), Freud tient would like to behave in the same

denominated as transference all the patient's way as he did in the past, while we, by

psychological phenomena and processes which summoning up every available mental

referred to the analyst and were derived from force in the patient compel him to come

other previous object relations. Therefore, in to a fresh decision. (Freud, cited in

one usage transference refers to all feelings of Racker, 1968/1982, p. 46)

the patient toward the psychotherapist which Regardless of whether the psychotherapist in-

are transferred from past relationships. The tentionally attempts to present a blank screen

phenomenological time of transference is thus or not, workable transference phenomena oc-

the past replayed in the present as if it were the cur with sufficient duration and intensity in

present. The phenomenological shape of most therapeutic relationships for effective

transference is the fantasized externalization of psychotherapy to take place.

an internal relationship between the individual

and one or more others (Manor [in press] Perspectives on Transference

relates this to intrapsychic and external trans- Although the terms complementary and con-

actional object relations). These others repre- cordant are used by Freud (1920/1955) and

sent significant relationships in the individual's Racker (1968/1982) to describe forms of

past (e.g., the mother/infant dyad, the child/ countertransference rather than transference,

parental couple triad, the child/family group, they are used here to describe several other

or the child/teacher/peer relationships). kinds of transferential phenomena. In his

Transference is thus that anticipatory pattern discussion of countertransference, Novellino

of relationship which the individual seeks to (1984) appeared to use the term "conforming

replicate with significant others, regardless of identification countertransference" (p. 63) in the

the other's individual, unique qualities ex- same way that Racker (1968/1982) used "con-

perienced at that moment. Transference is that cordant countertransference," but heretained the

relational pattern people carry with them from use of "complementary identification counter-

situation to situation. The other person is not transference" (p. 84). In addition, the terms "ab-

freely met for the first time, but more often normal" and "normal" were used by Winnicott

through a screen on which the person is pro- (1975) in relation to countertransference. This ar-

jecting his or her own particular movie. ticle suggests that the terms "facilitative" and

This article concentrates on dyadic transfer- "destructive" are better suited to these

ential relationship patterns, leaving the triadic phenomena, and it extrapolates their use to other

and group transferential phenomena for later categories of transference phenomena found in

discussion. However, the same analytic map psychotherapeutic and supervisory relationships.

presented here can be easily extrapolated to fit Also introduced in this context are Lewin's

]00 Transactional Analysis Journal

THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS: EXPLORATIONS IN TRANSFERENCE AND COUNTERTRANSFERENCE

(1963) tenus pro-active and reactive to designate of transference the patient seeks completion of

whether the subject of the discussion originates the symbiotic relationship. In a complementary

the stimulus (pro-acts) or responds to (reacts) a transference toward the projected Parent of the

stimulus from the other. Because the psychotherapist, the patient projects the actual

psychotherapeutic space belongs essentially to the or fantasized past historical parent onto the

patient, the psychotherapist's pro-activity is usual- therapist. For example, a patient expects the

ly, although not always, viewed as detracting therapist to humiliate him in the same way as

from the primary task-enhancing the patient's his historical parent did. Alternatively, the pa-

automonous pro-activity. tient may hope for an idealized fantasy parent

It is important to remember that transferen- based on childhood wishes.

tial or countertransferential stimuli may be ver- In another variation of complementary

bal or nonverbal. According to Berne's transference, the patient projects the actual or

(1961/1975) third rule of communication, the fantasized past Child ego state/s of the parent

ulterior or psychological level will generally onto the therapist. For example, the patient

determine the outcome. The mechanism by takes care of the psychotherapist's Child by

which this occurs is probably a form of hyp- protecting him or her from the patient's rage,

notic induction (Conway & Clarkson, 1987). or behaves in a way similar to the punitive

Under the circumstances described by Conway parenting which the patient introjected from his

and Clarkson, ulterior messages (communica- or her own abusive parentis.

tions) can have the force of hypnotic inductions Because of the nature of the psychotherapeu-

when an individual's Adult is decommissioned. tic relationship, projections onto the Child of

Script decisions often influence or interfere with the psychotherapist tend to be those of the

integrated Adult functioning (good contact with second-order structural symbiotic kind. For ex-

current reality). Therefore, whomever (analyst ample, because it is not the patient's function

and/or patient) is not in Adult may be influenced to take care of the therapist, but vice versa, the

outside ofawareness to feel or act in ways con- justification for such caretaking is usually based

sistent with the other's script expectations. This on a fantasy, for example, that the psychothera-

corresponds with and explains the idea of pro- pist needs to be taken care of because he or she

jective identification: "A complex clinical event is frightened. Likewise, an impaired therapeutic

of an interpersonal type: one person disowns his relationship may arise, for example, when the

feelings and manipulatively, induces [italics add- therapist inappropriately shows vulnerability or

ed] the other into experiencing them" (HiD- makes demands on the patient for such caretak-

shelwood, 1989, p. 2(0). ing. To avoid the despair of realizing and reliv-

Watkins (1954) also speculated on the ing the failure of the original parents, the pa-

similarities between trance and transference, tient may move into the complementary Child-

enumerating several ways in which psychoana- to-Parent transference.

lytic procedures induce changes of con- Concordant Transference. This form of

sciousness resembling trance induction. Unlike transference occurs when the patient projects

the intimates of patients, who have been roled his or her own past Child onto the psychothera-

into the patient's games, psychotherapists who pist in an attempt to find identification. For ex-

have been through their own personal ample, the patient imagines that the psycho-

psychotherapy are trained to remain with Adult therapist feels sad and lonely, whereas the pa-

in the executive while doing psychotherapy. tient's historic Child is grieving over an early

Thus they can notice the transferential projec- parental abandonment. In this form of trans-

tions and expectations in the ways they react ference, the patient may experience both self

to the patient, using such information to benefit and therapist as equally helpless. People with

the patient. Such objectivity necessitates con- a narcissistic personality disorder often use this

siderable self-knowledge, regular supervision, form of transference, particularly in the begin-

and interpersonal satisfactions outside of ning of psychotherapy: "I see in you, my

psychotherapeutic work. psychotherapist; the ways you are like me."

So, in a sense, this kind of patient experience

C~~ori~ofP~rentT~rennce has similarities to the mirroring or twin

Complementary Transference. In this form transferences described by Kohut (1977).

Vol. 21, No.2, April 1991 101

PETRUSKA CLARKSON

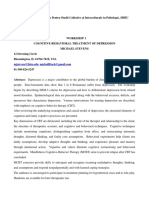

Either complementary or concordant been discussed. Figure 1 also adds brief

transference may contain potential for or (because of space limitations) explanations in

elements of destructive or facilitative forces. TA terms. Diagonal arrows are used in rela-

Destructive Transference. This form of tion to complementary transferences to indicate

transference involves the patient's acted out or the psychological inequality of the complemen-

fantasized destructive past as manifested in the tary relationships; horizontal arrows visually

psychotherapeutic relationship. Of course, this demonstrate concordance or identification;

only refers to occasions when third-degree downward arrows allude to the destructiveness

games are played to the pay-off point and not of unhealthy transference and its possible rela-

to the therapeutic use of destructive feelings and tionship to the force of Destrudo (Berne, 1969;

fantasies. It specifically refers to behavior that Weiss, 1950); upward-pointing arrows repre-

exceeds the boundaries of the psychotherapeutic sent the aspirational arrow, possibly related to

contract and that can no longer be dealt with Physis, the generalized creative urge that

in the psychotherapeutic arena. Such acting out reaches upward out of the individual's past ex-

of second- or third-degree games-e.g., periences toward the transformative potential

homicide, suicide, or transference psychosis- inherent in human nature (Berne, 1969, p. 89).

effectively destroys the psychotherapeutic con-

tract and often represents a script payoff or con- Countertransference Phenomena-

clusion. Such destructive acting-out makes Dermitions and Types

management procedures (e.g., hospital admis- Rycroft (1983) defined countertransference as

sion or daily supervision) that are extraneous 1. The analyst's TRANSFERENCE on

to the psychotherapeutic relationship necessary . his patient. In this, correct, sense,

Facilitative Transference. It is important to counter-transference is a disturbing,

differentiate normal or healthy transference distorting element in treatment. 2. By ex-

phenomena from other types of transference. tension, the analyst's emotional attitude

The patient may transfer (carry over) onto the towards his patient, including his

current psychotherapeutic relationship a response to specific items of the patient's

temperamental preference or style on the basis behaviour. According to Heimann

of what has been effective for him or her in the (1950), Little (1951), Gitelson (1952),

past. An easy-going, phlegmatic patient who and others, the analyst can use this latter

has a temperamentally slow pace (Eysenck & kind of counter-transference as clinical

Rachman, 1965) may prefer a psychotherapist evidence, i.e., he can assume that his

of a similar temperament. This is not necessari- own emotional reponse is based on a cor-

ly pathological. rect interpretation of the patient's true in-

The facilitating form of transference does not tentions or meaning. (p. 25)

fit the definition of script. In fact, it may repre- As can be seen from Rycroft's standard

sent productive learned patterns from the past definition, there are two major categories of

which are transferred into the present with a countertransference: one constituting the

successful outcome. Because these patterns are analyst's transference onto the patient, and the

not self-limiting (as scripts are), but, rather, other the analyst's responses to the patient. Win-

self-actualizing or aspirational (Clarkson, nicott (1975) defined as abnormal counter-

1989), they should not. be pathologized, but transference "those areas that arise from the

viewed as the possible basis for choosing a analyst's past unresolved conflicts that intrude on

compatible partner for the psychotherapeutic the present patient" (p. 175). In a sense these are

journey. However, they are technically the psychotherapist's transferences-he or she is

transferential in the sense that they are transfer- transferring material from his or her past onto

red from past affective relationships, not new- the client. Winnicott (1975) also differentiated

ly formed in the here-and-now. another type of countertransference which he

Figure 1 summarizes the forms of described as normal-those reactions that

transference and countertransference for the describe the idiosyncratic style of an analyst's

sake of comparison, clarity, and overview. It work and personality, whichI view as facilitative.

is most useful to look only at one segment of Winnicott (1975) also identified a category he

Figure 1 at a time after a particular topic has called "objective countertransference.... Those

102 Transactional Analysis Journal

THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS: EXPLORATIONS IN TRANSFERENCE AND COUNTERTRANSFERENCE

reactions evoked in an analyst by a patient's Categories of Reactive Psychotherapist

behaviour and personality . . . [which] can Countertransference

provide the analyst with valuable internal Complementary Reactive Countertransfer-

clues about what is going on in the patient" ence. The psychotherapist complements the pa-

(p.195). tient's real or fantasized projection (as Parent

I also differentiate between two major kinds or Child of the patient's parent) by responding

of countertransference depending on whether with the feeling probably experienced by the

the psychotherapist is reacting to a patient or original parent. For example, the therapist

pro-actively introducing his or her own responds to the patient's projection of his or

transference into the psychotherapeutic rela- her over-nurturing mother by feeling the urge

tionship. What Winnicott (1975) called "ob- to rescue.

jective countertransference" (p. 195) is re- Concordant Reactive Countertransference.

ferred to here as reactive countertransference The therapist experiences the patient's avoid-

to emphasise that the psychotherapist is reac- ed experience or resonates empathically with

ting accurately or objectively to the patient's the patient's experience. For example, after a

projections, personality, and behavior in the session the therapist feels unaccountably and

therapeutic relationship. Winnicott's (1975) uncharacteristically despairing; although the

"abnormal countertransference" (p. 195) is patient talked about her brother's death, she did

referred to here as pro-active counter- not let herself experience her corresponding

transference (psychotherapist transference) to emotions, and the therapist is left with the

emphasize the potential pitfalls that may result weight of the unexpressed feeling.

from the intrusion of the psychotherapist's Destructive Countertransference. The thera-

unresolved conflicts into the psychotherapeutic pist accepts the projected identification out of

relationship. As Novellino (1984) pointed out, awareness and acts on it in an unhealthy way.

the efficacy of this exploration depends on the For example, the patient sees the therapist as

ability of therapists to separate their issues from her neglectful mother: The therapist responds

their reactions to their patient's issues. by forgetting appointments and going on holi-

As already discussed, patients project their day without giving the patient due notice. The

script expectationsonto their therapists, and this patient's expectation acts as a subliminal, hyp-

often forms the matrix from which script notic induction to the therapist, who responds

redecisions can evolve. Whether therapists use outside of his or her awareness. It is the

the emotional, symbolic, or associative impact therapist's responsibility to be aware of such

on themselves of their patients' transferences indicators and to use them therapeutically, not

to benefit the patients (reactive counter- destructively.

transference) or as a vehicle for enacting their Facilitative Countertransference. It is again

own historically determined relationship pat- important, as Winnicott (1975) indicated, to

terns (pro-active countertransference) is largely differentiate countertransference that is normal,

determined, not by psychological perfection, healthy, and even possibly facilitative for the

but by integrated Adult awareness of self and patient. It is natural to feel affection for a

the impact of the other. lovable patient, appreciation for a creative one,

Understanding and feeling the impact and and respect for a humble one. Such feelings

nature of the transferences or projective may be based on one's past experiences of pa-

identifications that patients attempt to elicit tients. Withholding emotional responses to the

from the psychotherapist provides useful infor- healthy self-expressions of one's patients can

mation if the therapist's Adult is unimpaired. make the process of psychotherapy quite bar-

With a fully functioning Adult, therapists can ren and may lead us to neglect important op-

avoid being pulled into their patients' script portunities for enhancing creative capacities

dramas and can remain available to experience and reinforcing healthy behavior patterns.

these dramas (not being a mirrorlike projective

screen) while at the same time acting as an "in- Categories of Pro-active Psychotherapist

tegrated personality" (Federn, 1949/1977, p. Countertransference

218) who maintains conscious awareness and Complementary Pro-active Countertrans-

control. ference. This describes the process whereby the

Vol. 21, No.2, April 1991 103

PETRUSKA CLARKSON

therapist brings into the therapeutic relationship with him in the same way as the therapist's

his or her script transferences, projections, and father did; he may then reject the patient at the

expectations based on past experiences. This first sign of negativity. Alternatively, the

is usually considered to be unhelpful and is therapist may transfer his or her own suicidal

frequently destructive to the therapeutic tendencies on to the patient; if the patient is

process. Of course therapists are not perfect, obliging and, for example, needs a parent for

and are on their own personal journeys of self- whom sacrifice is necessary, the patient may

discovery and self-development. That personal commit suicide, in a sense, for the psycho-

script issues, suppressed feelings, or avoided therapist/parent. English (1%9) referred to the

sensitivities may be present in psychotherapists hot potato (or episcript) passed from parents

at work cannot be denied. Whether or not these to children. In addition, I believe that it can be

are in awareness, acknowledged, owned, passed from psychotherapist to patient.

worked through, supervised, humbly accepted, Facilitative Pro-active Countertransference.

or truly transformed is what makes the dif- This form of countertransference is based on

ference between unconscious exploitation and the unavoidable and probably necessary ex-

helpful empathy for the human struggle. istence of the psychotherapist's individual style

Complementary pro-active countertransfer- and personal preferences. For example, a

ence occurs when the psychotherapist com- therapist may enjoy working with people with

plements (or completes the gestalt of) the pa- creativity problems rather than control issues.

tient's real or fantasized projection as Parent What makes this transferential and not based

or Child based on the therapist's own past, or on a newly-ereated Adult discovery in the here-

projects the actual or fantasized past Parent or and-now, is the fact that the therapist assumes

Child. For example, the therapist may behave this on the basis of his or her past experiences.

in a withholding, passive, and coldly analytical Thus he or she may disallow himself or herself

way in response to the patient's neediness, not the potential delights of working with patients

because this is therapeutically appropriate, but who are controlling.

because this is the way the therapist was treated

by his or her parents. Categories of Reactive Patient

Concordant Countertransference. The psy- Countertransference

chotherapist experiences the patient's ex- Every psychotherapist occasionally in-

perience based on the therapist's own past. For troduces pro-active countertransference

example, the therapist assumes that the patient elements-that is, the therapist's self-generated

feels guilty about injuring a schoolfriend in the issues-into the therapeutic relationship. For

same way that he or she did when younger. The example, a therapist may come to a session late

patient mayor may not have a similar ex- as result of a car accident and the resulting traf-

perience, and such identificationneeds from the fic snarl-up. Naturally, patients respond to such

therapist may be unhelpful or actively hinder- events and to the therapist's demeanor, possibly

ing to the therapy process. in archaically determined ways via transference

Destructive Pro-active Countertransference. or in ways that are more reactive to the

The psychotherapist enacts (or acts out) his or therapist's past than to their own.

her own past in the psychotherapy in ways that I also identify another form of counter-

are destructive or limiting to the patient's transference: the patient's reactive counter-

welfare. This, of course, is identical to what transference to the therapist's introduction of

would be understood by Rycroft (1983) as the his or her own material. Technically this is not

psychotherapist's transference in the broad the patient's transference because it is not based

sense (i.e., of transferring relationship patterns on his or her past material, but is elicited by

from the past into current relationships) or in the therapist's abnormal or pro-active counter-

the narrow sense (i.e., the feelings engendered transferences. Just as patients can induce

toward the analyst based on transferring rela- therapists to respond/react in ways that are

tionship patterns or expectations from the pa- script-reinforcing by means of the hypnotic in-

tient's [or in this case the psychotherapist's] duction of ulterior communications, so too, can

past). For example, a young psychotherapist therapists project onto their patients or even af-

may expect that an older patient will find fault fect them by means of projective identification.

104 Transactional Analysis JOUr1UJ1

THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS: EXPLORATIONS IN TRANSFERENCE AND COUNTERTRANSFERENCE

CLIENT TRANSFERENCE PRO-ACTIVE TYPE

Complementllry - - - -....~ Client projects llCtUlll or fllntllsised pest Parent of parent

(seeks comp Ieti on)

.. Client projects ectuei or r entestsed PllSt Child of pllrent

concorcent --I.~

. Client projects client's pest Child

(seeks i denti fl cet i on)

Destruct i ve CIIent 's ectad out or fllntllsi sed destructi ve pest

+

Fllcilitlltive

t Client's temperament. liking, style besed on pest experience

PSYCHOTHERAPIST COUNTERTRANSFERENCE RE-ACTIVE TYPE

Complementllry .. Psychotherllpist complements client's reei or rentestssd projection es

(seeks completion) Pllrent or Child of client's Pllrent

Concord lint

(seeks tdenttr teettcn)

.. Psychotherepi st experiences client's llvoided experience or resonates

empllthiclllly with client's experience

Destructive Psychotherllpist eccspts projected tdsnttr tcetton in destructive WilY

+

FllCilltlltive

t Psychotherllpist's responses to client's style or preferences

PSYCHOTHERAPIST (COUNTER)TRANSFERENCE PRO-ACTIVE TYPE

Complamenteru Psychotherllpist complements client's relll or fllntllsised projection es

(seeks comp Ieti on)---

.....

~

Pllrent or Child bllsed on his/her own cest or projects ectuet or

fllntllsised past Parent or Child

concorcent

(seeks tdanttr tcet ton)

.. Psychotherllpist experiences client's experience based on his/her own

pest

Destructi ve Psychotherllpist's pest enacted in psychotherapy (therepists

trenstersnce) In destructive WllyS

+

Fllcilitlltive

t Psychotherllpist's style end personel preferences

CLIENT COUNTERTRANSFERENCE RE-ACTIVE TYPE

compternenterq .. Client completes psychotherllpist's reet or fllntllsised projection es

(seeks completion-"j----~_~ Parent or as Child based on the psychotherapist's past

concorcent

(seeks Ident i fi cet ion) .. Client experiences psqchctherectsts denied Child or resonet es

empathiclllly with thsreptst's experience

Destructive Client answers psychotherllpist's induced Pllthology

r ectutettve Client's responses to Psychotherllpist's preferences end style

Figure 1

Summary Diagram

Vol, 21, No, 2, April 1991 105

PETRUSKA CLARKSON

Langs (1985) and Casement (1985) have psychotherapist begin to talk about issues that

repeatedly addressed the many ways in which they could not share with the first. According

the patient provides the psychotherapist with to Miller (1985), such avoidance may also be

feedback, supervision, and active attempts to based on the patient protecting the

"heal" the therapist. However, when neither parent/therapist from dealing with his or her

is aware of this collusion, therapeutic progress own feelings of abandonment or abuse.

may be undermined or destroyed. Searles Destructive Patient Countertransference.

(1975) also suggested the idea that the patient This refers to particularly damaging acted-out

needs to heal his or her psychotherapist. Alter- patterns between psychotherapist and patient that

natively, the patient may try hard to be a good are primarily based on the therapist's pathology.

patient because the therapist needs children who In such cases the therapist's transference may in-

work hard but never achieve success. duce pathological responses of an extreme nature,

ComplementaryPatient Countertransference. such as "going mad for the psychotherapist,"

The patient may react complementarily by com- which allows the therapist to avoid dealing with

pleting the psychotherapist's real or fantasized his or her own madness while dealing with the

projection as Parent or as Child based on the patient's madness.

therapist's history or recent past. For example, Facilitative Patient Countertransference.

a patient who does not have issues about tak- This form of patient countertransference in-

ing care of his or her parents may find that he volves the patient's natural responses to the

or she is invited or induced to take care of the therapist's style and way of being. After a long

psychotherapist when the therapist is experi- and intimate therapeutic relationship which leads

enced as tired, burned out, or fragile. The im- to productive changes in a patient's life, he or

portant factor differentiating this from psycho- she may feel fondness and affection for certain

therapist-induced reaction lies in not attributing qualities of the therapist. An example would be

projection to the patient. He or she is correctly a particularly apt use of metaphor or a clarity of

perceiving the therapist's emotional states as thinking and expression which is not counter-

they impinge upon the therapy. therapeutic but which is based on an apprecia-

Good therapeutic management of this form tion of the particular attributes of the helper.

of patient countertransference involves identi-

fying what both the psychotherapist and the pa- Conclusion

tient bring into the therapy room, without blam- The meanings of transference and counter-

ing or attributing causality to the pathology or transference have been explored and refined in

projection of the patient. The therapist is this article by means of comparison, contrast,

responsible for separating out such elements and clarification. The understanding and ap-

from the psychotherapeutic relationship and plication of these various forms of transference

taking preventive or corrective action through, and countertransference in psychotherapeutic and

for example, further analysis and/or additional supervisory settings using transactional analysis

supervision. will be developed in an article to be presented

Concordant Patient Countertransference. in the an upcoming issue of this journal.

Concordant patient countertransference occurs

when, for example, the patient identifies with Petrisska Clarkson, M.A., Ph.D. (Chartered

the therapist's denied Child or resonates em- Clinical Psychologist), A.F.B.Ps.S., Certified

pathically with the therapist's experience, Transactional Analyst Instructor and Super-

whether or not those feelings or experiences are visor, is the Director of Clinical Training at

valid for the patient. A patient may sense the metanoia Psychotherapy Training Institute in

therapist's fear of violence based on the London. She has been on the ITAA Board of

therapist's unresolved issues about a violent Trustees and is currently Chairperson of the

childhood home; in resonating with these feel- Gestalt Psychotherapy Training Institute of

ings, the patient avoids sharing his or her feel- Great Britain and National Coordinator ofthe

ings of violence or murderous rage toward the British Society for Integrative Psychotherapy.

therapist, fearing that the therapist could not Please send reprint requests to Dr. Clarkson

cope with it. This process is frequently at work at metanoia, 13 North Common Road, London

with patients who with a second or third W5 2QB, England.

106 Transactional Analysis Journal

THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS: EXPLORATIONS IN TRANSFERENCE AND COUNTERTRANSFERENCE

REFERENCES Hinshelwood, R. D. (Ed.) (1989). A dictionary of Klei-

Berne, E. (1969). A layman's guide to psychiatry and nian thought. London: Free Association Books.

psychoanalysis. London: Andre Deutsch. Klein, M. (1984). Envy, gratitude and other works. Lon-

Berne, E. (1975). Transactional analysis in psychotherapy. don: The Hogarth Press and Institute for Psychoanalysis.

London: Souvenir Press. (Original work published 1961) Kohut, H. (1977). The restoration ofthe self. New York:

Casement, P. (1985). On learning from the patient. Lon- International Universities Press.

don: Tavistock. Langs, R. (1985). Workbooks for psychotherapists (Vols.

Clarkson, P. (1989). Metanoia: A process of transforma- 1-3). Emerson, NJ: Newconcept.

tion. Institute of Transactional Analysis News, 23, 5-14. Lewin, K. (1963). Field theory in social science: Selected

Clarkson, P. (1990). A multiplicity of psychotherapeutic theoretical papers. London: Tavistock.

relationships. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 7, Little, M. (1951). Countertransference and the patient's

148-163. response to it. International Journal ofPsychoanalysis,

Conway, A., & Clarkson, P. (1987). Everyday hypnotic 32,32-40.

inductions. Transactional Analysis Journal, 17, 17-23. Manor, O. (in press). Transactional object relations: Ob-

English, F. (1969). Episcript and the "hot potato" game. ject relations, indirect gain and systems approach.

Transactional Analysis Bulletin, 8(32), 77-82. Miller, A. (1985). Thou shalt not be aware: Society's

Eysenck, H. J., & Rachman, S. (1965). The causes and betrayal ofthe child (H. & H. Hannum, Trans.). Lon-

cures of neurosis. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. don: Pluto Books. (Original work published 1981)

Fairbairn, W. R. D. (1952). Psychoanalytic studies ofthe Novellino, M. (1984). Self-analysis of countertransference

personality. London: Tavistock. in integrative transactional analysis. Transactional

Fedem, P. (1977). Ego psychological aspect of Analysis Journal, 14, 63-67.

schizophrenia. In P. Fedem, Ego psychology and the Pine, F. (1985). Developmental theory and clinical pro-

psychoses (pp. 210-226). London: Maresfield Reprints. cess. New Haven: Yale University Press.

(Original work published 1949) Racker, H. (1982). Transference and countertransference.

Freud, S. (1955). Beyond the pleasure principle. In J. London: Maresfield Reprints. (Original work published

Strachey (Ed. and Trans.), The standard edition of the 1968)

complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. Rycroft, C. (1983). A critical dictionary afpsychoanalysis.

18, pp. 1-64). London: Hogarth Press. (Original work Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin.

published 1920) Searles, H. F. (1975). The patient as therapist to his analyst.

Freud, S. (1958). The dynamics of the transference. In J. In P. L. Giovacchini (Ed.), Tactics and techniques in

Strachey (Ed. and Trans.), The standard edition of the psychoanalytic therapy, Vol II (pp. 94-151). New York:

complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. Aronson.

12, pp. 97-108). London: Hogarth Press. (Original work Watkins, J. G. (1954). Trance and transference. Journal

published 1912) of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 2,284-290.

Gitelson, M. (1952). The emotional position of the analyst Weiss, E. (1950). Principles of psychodynamics. New

in the psychoanalytic situation. International Journal of York: Grone & Stratton.

Psychoanalysis, 33, 1-10. Winnicott, D. W. (1975). Hate in the countertransference.

Heimann, P. (1950). On countertransference. International In Through paediatrics to psychoanalysis (pp. 194-203).

Journal of Psychoanalysis, 31, 81-84. London: Hogarth Press.

Vol. 21, No.2, April 1991 107

You might also like

- Evidence Based Practice of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Second Edition Deborah Dobson Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFDocument59 pagesEvidence Based Practice of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Second Edition Deborah Dobson Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFchristopher.gomez833100% (11)

- The Mind in Conflict (Charles Brenner) (Z-Library)Document284 pagesThe Mind in Conflict (Charles Brenner) (Z-Library)zjcashin2857100% (1)

- Further Through The Looking Glass Transference Countertransference and Parallel Process in Transactional Analysis Psychotherapy and SupervisionDocument11 pagesFurther Through The Looking Glass Transference Countertransference and Parallel Process in Transactional Analysis Psychotherapy and SupervisionDoru PatruNo ratings yet

- Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy - Eric BerneDocument138 pagesTransactional Analysis in Psychotherapy - Eric BernePsicologia Rodoviária100% (20)

- 112200921441852&&on Violence (Glasser)Document20 pages112200921441852&&on Violence (Glasser)Paula GonzálezNo ratings yet

- The Para-Existential Personality DisorderDocument10 pagesThe Para-Existential Personality DisorderKostas RigasNo ratings yet

- Case FormulationDocument17 pagesCase Formulationksenijap100% (3)

- Healing Power of Greek TragedyDocument8 pagesHealing Power of Greek TragedyMike WenzkeNo ratings yet

- Concept of The Stimulus in Psychology - GibsonDocument10 pagesConcept of The Stimulus in Psychology - GibsonwalterhornNo ratings yet

- Robert WallersteinDocument26 pagesRobert WallersteinRocio Trinidad100% (1)

- HOWARD Pierce The Big Five Quickstart PDFDocument27 pagesHOWARD Pierce The Big Five Quickstart PDFCarlos VenturoNo ratings yet

- Patterns Lesson Plan 5 - Marshmallow ActivityDocument2 pagesPatterns Lesson Plan 5 - Marshmallow Activityapi-332189234No ratings yet

- The Script: Time For A New VisionDocument8 pagesThe Script: Time For A New VisionMircea RaduNo ratings yet

- Theory of Democratic Teaching by Rudolf Dreikurs: TSL 3109 Managing The Primary ESL ClassroomDocument7 pagesTheory of Democratic Teaching by Rudolf Dreikurs: TSL 3109 Managing The Primary ESL ClassroomSiti SyariefNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Consumer BehaviourDocument2 pagesFactors Influencing Consumer BehaviourGundeep SinghNo ratings yet

- J. Bleger ArtDocument10 pagesJ. Bleger Artivancristina42No ratings yet

- Dualism AssignmentDocument2 pagesDualism Assignmentyer tagalajNo ratings yet

- Utrecht1 PDFDocument1 pageUtrecht1 PDFgfNo ratings yet

- Goodman, A. (1993) - The Addictive Process.Document10 pagesGoodman, A. (1993) - The Addictive Process.Sergio Ignacio VaccaroNo ratings yet

- Child AbandonmentDocument8 pagesChild AbandonmentAna Iancu100% (1)

- Common FactorsDocument81 pagesCommon FactorsmarysujathaNo ratings yet

- Edith Gould - Erotized Transference in A Male PatientDocument15 pagesEdith Gould - Erotized Transference in A Male PatientGogutaNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Perfectionism, Stress and Burnout in Clinical PsychologistsDocument13 pagesThe Relationship Between Perfectionism, Stress and Burnout in Clinical PsychologistsVinícius SoaresNo ratings yet

- Cicchetti 2002Document15 pagesCicchetti 2002Kiara JohanaNo ratings yet

- Payment PDFDocument35 pagesPayment PDFLauraMariaAndresanNo ratings yet

- Mourning and Symbolization A ComparativeDocument116 pagesMourning and Symbolization A ComparativeHermina ENo ratings yet

- Budism Ans SCDocument3 pagesBudism Ans SCedumorgabNo ratings yet

- Enactments, Transference, and Symptomatic CureDocument1 pageEnactments, Transference, and Symptomatic CureIzabelle LiaNo ratings yet

- Workshopuri SibiuDocument21 pagesWorkshopuri SibiuDyana AnghelNo ratings yet

- AtheismDocument3 pagesAtheismKarel Michael DiamanteNo ratings yet

- The Historical Evolution of PTSD Diagnostic Criteria: From Freud To DSM-IVDocument18 pagesThe Historical Evolution of PTSD Diagnostic Criteria: From Freud To DSM-IVZach FoutchNo ratings yet

- LazarusDocument22 pagesLazarusGaby GavrilasNo ratings yet

- 01 - Lapworth - CH - 01 PsychologyDocument16 pages01 - Lapworth - CH - 01 PsychologykadekpramithaNo ratings yet

- KernbergDocument29 pagesKernbergLoren DentNo ratings yet

- Object Relations Group PsychotherapyDocument6 pagesObject Relations Group PsychotherapyJonathon BenderNo ratings yet

- Dialectics Juan Pascual-Leone PDFDocument140 pagesDialectics Juan Pascual-Leone PDFFatima LamarNo ratings yet

- ANALYSIS OF TRANSFERENCE Vol. II 163,7 MBDocument254 pagesANALYSIS OF TRANSFERENCE Vol. II 163,7 MBMariana Pantece100% (1)

- The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (ECR) - Short Form: Reliability, Validity, and Factor StructureDocument18 pagesThe Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (ECR) - Short Form: Reliability, Validity, and Factor Structurelobont nataliaNo ratings yet

- Virga Et Al 2009 PRU - UWESDocument17 pagesVirga Et Al 2009 PRU - UWESCarmen GrapaNo ratings yet

- Cazul Cyril Burt 3Document3 pagesCazul Cyril Burt 3Cosmina MihaelaNo ratings yet

- Social Intelligence - A Review and Critical Discussion of Measurement ConceptsDocument31 pagesSocial Intelligence - A Review and Critical Discussion of Measurement ConceptsMakrand KulkarniNo ratings yet

- Culture and PsychopathologyDocument7 pagesCulture and PsychopathologyKrishan TewatiaNo ratings yet

- Timeline of Modern PsychologyDocument3 pagesTimeline of Modern PsychologyrdhughbankNo ratings yet

- Para-Romantic Love and Para-Friendships Development and Assessment of A Multiple-Parasocial Relationships ScaleDocument25 pagesPara-Romantic Love and Para-Friendships Development and Assessment of A Multiple-Parasocial Relationships Scalepuskesmas pakutandangNo ratings yet

- Boredom StudyDocument56 pagesBoredom StudyTeoNo ratings yet

- Tet GordonDocument39 pagesTet Gordonapi-350463121No ratings yet

- Deconstructing PsychosisDocument8 pagesDeconstructing PsychosisEvets DesouzaNo ratings yet

- A Revision of Freud S Theory of The Biological Origin of The Oedipus ComplexDocument28 pagesA Revision of Freud S Theory of The Biological Origin of The Oedipus ComplexSilvia R. AcostaNo ratings yet

- Marc Widdowson - TA Treatment of Depresssion (Peter)Document11 pagesMarc Widdowson - TA Treatment of Depresssion (Peter)Ana AndonovNo ratings yet

- Dependent Personality DisorderDocument3 pagesDependent Personality DisorderRanaAdnanShafiqueNo ratings yet

- Researchcentral: Despre Researchcentral Echipa Lista Testelor Recomandari de Utilizare Participa ContactDocument2 pagesResearchcentral: Despre Researchcentral Echipa Lista Testelor Recomandari de Utilizare Participa ContactDorin TriffNo ratings yet

- PsihanalizaDocument19 pagesPsihanalizaElena AtudosieiNo ratings yet

- Boundaries and Boundary Management in Counselling: The Never-Ending StoryDocument22 pagesBoundaries and Boundary Management in Counselling: The Never-Ending StorydaveNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout, andDocument30 pagesFactors Associated With Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout, andpratiwi100% (1)

- Abraham, New York: Basic Books, 1927: Bandura, A.Document13 pagesAbraham, New York: Basic Books, 1927: Bandura, A.Dana GoţiaNo ratings yet

- Final UploadDocument24 pagesFinal Uploadapi-428157976No ratings yet

- Adler Theory of PersonalityDocument2 pagesAdler Theory of PersonalityAbrar Ahmad100% (1)

- 300235-Medieval PPT TemplateDocument1 page300235-Medieval PPT TemplateJohn DoeNo ratings yet

- The Princeps Case, Breuer's Anna O. Revisited - Filip GeerardynDocument7 pagesThe Princeps Case, Breuer's Anna O. Revisited - Filip Geerardynpsy_blogNo ratings yet

- v12 Gloria, Sylvia 4 & 5, Kathy & DioneDocument109 pagesv12 Gloria, Sylvia 4 & 5, Kathy & DioneAldy MahendraNo ratings yet

- Atozpersonalitytheories 140312001737 Phpapp01Document65 pagesAtozpersonalitytheories 140312001737 Phpapp01ANSIFNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument13 pagesResearch PaperChris FreemanNo ratings yet

- Confusion and Introjection A Model For Understanding The Defensive Structures of The Parent and Child Ego States PDFDocument14 pagesConfusion and Introjection A Model For Understanding The Defensive Structures of The Parent and Child Ego States PDFUrosNo ratings yet

- Stucke 2003Document14 pagesStucke 2003Алексей100% (1)

- Emotional Competence: The Fountain of personal, professional and private SuccessFrom EverandEmotional Competence: The Fountain of personal, professional and private SuccessNo ratings yet

- The Many Dimensions of Transference : Kenneth E. BrusciaDocument10 pagesThe Many Dimensions of Transference : Kenneth E. BrusciaOana ToaderNo ratings yet

- Transference and The Therapeutic Relationship Working For or Against ItDocument14 pagesTransference and The Therapeutic Relationship Working For or Against ItBunyippy67% (3)

- Freud's Structural and Topographical Models of PersonalityDocument8 pagesFreud's Structural and Topographical Models of PersonalityRabeeyat HassanNo ratings yet

- Robinson W FamilyDocument15 pagesRobinson W FamilyVictoria DereckNo ratings yet

- Timothy Gordon - Jessica Borushok - The ACT Deck - 55 Acceptance & Commitment Therapy Practices To Build Connection, Find Focus and Reduce Stress-PESI Publishing (2019)Document19 pagesTimothy Gordon - Jessica Borushok - The ACT Deck - 55 Acceptance & Commitment Therapy Practices To Build Connection, Find Focus and Reduce Stress-PESI Publishing (2019)brunna.abracoabaNo ratings yet

- Summary of The Wolfman Study 1Document1 pageSummary of The Wolfman Study 1luciferNo ratings yet

- Medical Psychology (Tutorial) 2016Document72 pagesMedical Psychology (Tutorial) 2016Vidhu YadavNo ratings yet

- DIASS Study Material Sept 25 30Document2 pagesDIASS Study Material Sept 25 30CijesNo ratings yet

- Kaynakca Mentalisieren in Der Psychodynamischen Und Psychoanalytischen PsychotherapieDocument4 pagesKaynakca Mentalisieren in Der Psychodynamischen Und Psychoanalytischen Psychotherapieazime.aylin.doganNo ratings yet

- Assessment 1 - Dissociative Identity DisorderDocument3 pagesAssessment 1 - Dissociative Identity DisorderFarouk RomancapNo ratings yet

- When Sexual and Religious Orientation CollideDocument25 pagesWhen Sexual and Religious Orientation Collideabdurrakhman saparNo ratings yet

- NLP: The Essential Guide To Neuro-Linguistic Programming - NLP ComprehensiveDocument5 pagesNLP: The Essential Guide To Neuro-Linguistic Programming - NLP Comprehensivezynakomi100% (2)

- Counseling Skills & TechnqiuesDocument66 pagesCounseling Skills & TechnqiuesDolorfey Sumile100% (6)

- Thesis On Binary OppositionDocument5 pagesThesis On Binary Oppositionbsq39zpf100% (1)

- 02 - Handout - 2 StsDocument1 page02 - Handout - 2 StsCastillo EmmieNo ratings yet

- JohannesTownsendFerris 13 1Document24 pagesJohannesTownsendFerris 13 1Hemant100% (1)

- Goodrich Sandsand Catena 2015Document21 pagesGoodrich Sandsand Catena 2015rizkynovitasaripradanaNo ratings yet

- Why Is Coping Mechanism ImportantDocument3 pagesWhy Is Coping Mechanism ImportantEra CristineNo ratings yet

- The Derivation of A Psychological Theory - Gestalt TherapyDocument0 pagesThe Derivation of A Psychological Theory - Gestalt TherapyAdriana Bogdanovska ToskicNo ratings yet

- Chapters 1 4 Without Curriculum VitaeDocument40 pagesChapters 1 4 Without Curriculum Vitaebea kullinNo ratings yet

- Paul Dubois - Psychic Treatment of Nervous Disorders (1909)Document492 pagesPaul Dubois - Psychic Treatment of Nervous Disorders (1909)tefsom100% (2)

- Natalie Pearce ResumeDocument2 pagesNatalie Pearce Resumeapi-401812271No ratings yet

- For The Treatment of Opioid Use DisorderDocument95 pagesFor The Treatment of Opioid Use DisorderDragutin Petrić100% (1)

- Unit 4 Revision NotesDocument45 pagesUnit 4 Revision NotesManal_99xoNo ratings yet

- Adapting CBT For Children With An Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)Document3 pagesAdapting CBT For Children With An Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)Ina HasimNo ratings yet