Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kumar ContestingModernityCrises 2008

Kumar ContestingModernityCrises 2008

Uploaded by

dionessa.bustamante09Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kumar ContestingModernityCrises 2008

Kumar ContestingModernityCrises 2008

Uploaded by

dionessa.bustamante09Copyright:

Available Formats

Contesting Modernity: Crises of Democratisation in South Asia

Author(s): Sanjeev Kumar

Source: India Quarterly , October-December 2008, Vol. 64, No. 4 (October-December

2008), pp. 124-155

Published by: Sage Publications, Ltd.

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45073167

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sage Publications, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

India Quarterly

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contesting Modernity: Crises of

Démocratisation in South Asia

Sanjeev Kumar H.M. *

Despite, the frenetic pace of modernization represented by

corporate globalisation, liberal democracy, considered to be

an epitome of modernity, seems to have not yet succeeded

in establishing itself as an unchallenged global phenomenon.

Forces anti-theatrical to democratic values such as ethno-

cultural chauvinism or linguistic fanaticism, have fiercely

contested democratic processes and "even the third wave of

démocratisation merely has had a greater breadth than

depth." [Diamond 1997] In semi-modern societies, liberal

democracy has manifested in heterodox forms, "outside the

wealthy industrialized countries, liberal democracy tend to

be shallow, illiberal and poorly institutionalized." [Zakaria

1997] South Asia represents one such region, where in despite

the advent of globalisation, rampant déstabilisation of the

democratic mechanism in its polities still persists.

* Lecturer, Department of P. G. Studies and Research in Political

Science, Allahabad University, Allahabad.

124

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contesting Modernity: Crises of Démocratisation in South Asia

This is because the region is characterised by the existence

of anti-modernist forces such as Islamic extremism or the

caste based Hindu social order, which have contributed

significantly in engendering a semi-modern form of society

in the region. This naturally has encumbered the smooth

démocratisation of the region and the resultant tumult has

generated intense intra-regional tensions. It is the contention

of this paper that for the maturity of democratic institutions

in South Asia, over all modernization of the societies of the

region is crucial. It means that the level of modernization

will playa decisive role, in determining the extent of success

of democratic governance. In a Sense, démocratisation

process is linked-up to the modernization process and only

an inter-locking balance between the two, will lead to a stable

polity and a liberal society. So the basic argument here is

that democratic déstabilisation in South Asia, is an offshoot

of what I have called the half-baked modernity syndrome;

meaning that the process of modernization has not reached

a fruition point. As compared to the West, South Asia is

neonate in terms of its experience with democracy.

Nevertheless, more than six decades of experiment with

democratic institutions seem to have not been enough for

the polities of the region to transform into mature and stable

democracies.

Here we are drawn into asking a fundamental epistemic

question that whether liberal democracy is only compatible

to developed capitalist polities of the West and not suitable

for the developing societies? The capricious state of

democracy in South Asia compels us to raise this question,

"that too at a moment when few political leaders even in

authoritarian regimes are willing to argue aloud against

125

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sanjeev Kumar

democracy since its virtues are now almost universally

accepted." [O-Loughlin 2007] This beholds our attention to

the passionate views of Francis Fukuyama who famously

declared that "End of history had been reached, because

liberal democracy constitutes the end point of mankind's

ideological motivation and is the final form of human

Government." [Fukuyama 1992] In a similar expression,

David Held articulates thus: "democracy had scored a

historic victory over alternative forms of governance." [Held

1993]

However, ridiculing the ideas of these Western liberals, South

Asia presents an utterly contrasting picture. The region's tryst

with democracy has been a wretched tale of unhappy

political experience and the countries of this region have

constantly grappled to either establish and sustain, or restore

democratic institutions. In spite of globalisation of their

national economies and neo-liberal reforms, a relentless

consternation of subversion has beleaguered their democratic

socio-political order. Representative of this fact,

incompetence of the democratically elected political class iti

Pakistan and Bangladesh has several times rendered

opportunities to the anti-democratic and extremist forces,

to capture political power. Or in India, Sri Lanka and Nepal,

weakness of the democratic State has led to the emergence

or intensification of anti-regime activities.

Rise of Democracy in South Asia, How Distinct

From That of the Western Democracies

When we look out for the principle elements that sire a

faultline between the thriving democratic polities of the West

and the quivering democracies of South Asia, The level of

126

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contesting Modernity: Crises of Démocratisation in South Asia

modernity of the two regions gets highlighted. "While in

the case of modern Western societies, democracy emerged

simultaneously and matured together in a temporary parallel

development of other modern processes that included, rise

of industrial capitalism, urbanization, rationalization and

secularization. The concatenation of these forces configure

together to form a modern society. "[Kaviraj 2000]

Paradoxical to this, in South Asia, the polities

anachronistically attempted to emulate the Western model

of democratic political process, by superficially imposing the

Western style of democratic institutions without graduating

through other modern processes. This seems to be one crucial

factor that has rendered the démocratisation process into

shambles. In a way, South Asia adopted the Western model

of democratic governance, with their societies still possessing

semi-feudal, semi-urban and semi-industrial characters.

Yet another significant thing to be noted is the region's socio-

cultural idiosyncrasy which also lingers as a major incompatibility

to Western model of democratic governance. "This points to the

necessity of analysing the situation of democratic Governments

from the perspective of cultural differences of various

regions." [lnglehart and Carballo 1997] "Thus in view of this, focus

on national differences has also been recognized." [Schwartzman

1998] Putting things in this perspective, it maybe argued that the

démocratisation processes of the West and of South Asia exhibits

asymmetric trends. Where as in the West, democratic State was

a product of multiple modern processes and got ensconced in a

ripe modern society. In sharp contrast to this, in South Asia

democratic State has been the antecedent of a modem

society.

127

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sanjeev Kumar

While the Democratic polities of the West have flourished

because of the existence of fully baked modern societies in

different countries of the region. Diametric to this, the State

in South Asia emerged as the harbinger of modernity and

was supposed to be the sole engine of social transformation

and catalyst of various modern processes. This pushed the

region into the theatrics of a conflict, between the modern

liberal State with its reformative agenda and the deep-rooted

and archaic socio-cultural structures with their hegemonic

tendencies.

It generated immense social tensions and political friction,

leading us to the notion that "democracy cannot be

simulated, rather it must be grown from within."(Carothers

1999] Apart from this, the socio-economic under-

development of the region helped the dominant actors in

the society to maneuver their way to the pinnacle of political

power. "Thus a democratic State proved to be more

advantageous for the powerful actors in the society, who

nurtured motives for a quixotic perpetuation of their

hegemony." [Huntington 1992] This rendered the democratic

State to become an instrument for the maintainence of social

hegemony by the powerful groups, resulting in subaltern

discontent that fountained anti-regime sentiments, leading

to frequent political destabilisations.

Why Modernisation Process in South Asia

is Dissimilar to That of the West

Yet another factor that needs to be reckoned with is that when

we speak of modernity, it would be parochial to visualize

the phenomenon purely from the Western perspective. To

be precise, South Asia cannot modernize in the same fashion

128

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contesting Modernity: Crises of Démocratisation in South Asia

as that of the West. The simple reason being socio-cultural

idiosyncrasy and different histories of the two regions. Thus

some lines of differentiation has to be delineated. In this

connection, Sudipta Kaviraj indicates that "The more

modernity expands and spreads to different parts of the

world it becomes more differentiated and plural" [Kaviraj

2000]

A fitting illustration of this symptom is the foundations of

social hierarchy in both the societies. As regards the West,

the social stratification is primarily based upon income,

where as in South Asian countries like India and Nepal, the

dogmatic orthodoxy of religion manifested in the caste

system, determines the social hierarchy. Similarly, as far as

the histories of the two regions are concerned, it may be noted

that in the West, the notion of a modem Nation-state emerged

in the era of renaissance and has been a product of religious

reforms and secularization of politics. In the case of South

Asia, the birth of the modern Nation-State was rather

influenced by the anti-colonial movement. Hence the process

of modernization in South Asia must be disengaged from its

encasement into the Western paradigm. To put it in the words

of Dipesh Chakravarti "Europe can be provincialised only if

we recognise that although its origins were certainly

European, modernity's expansion makes it increasingly leave

behind and forget its origins." [Chakravarti 2002]

"So alternative paradigms of modernity for different regions

becomes an imperative." [Gaonkar 2001] Take for instance

the contention of S.N. Eisenstadt that "if we think closely

and seriously about American history we are forced to

recognise the first case of emendation in the direction of a

theory of multiple modernities. There were sufficiently

129

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sanjeev Kumar

strong peculiarities in American history , colonialism, the

presence of three different races and the resultant use of

endemic violence against racially subordinated communities

which made American modernity sufficiently different from

the standard European cases and to call for a serious attempt

in theoretical différenciation." [Eisenstadt 2000]

In this context, South Asia also exhibits uniqueness as a

region and it demands a recognition in accordance to its

peculiar attributes. Its multi ethnic character, a long

subjection to colonial rule, the religio-civilisational over-

lappings among the polities and the archaic nature of the

cultures of different communities of the region, all beg a

larger consideration and indicate towards the need for

developing a South Asian conception of modernity.

Crises of Démocratisation in South Asia

Inability to achieve a fully baked modern society has been

an instrumental force in retarding the process of

démocratisation in South Asia. It has made the process more

excrutiating and also prolonged the solution of numerous

other problems of the region. The crises of democratization

in South Asia manifests in the failure of democratic system

of governance in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, the

authoritative anti-democratic and extremist character of the

polity in Maldives, the heightening ethnic divide in Sri Lanka

and the "the existence of a crises of governability in

India." [Kohli 1999] Besides this, the region is plagued by

generic problems such as, the dogmatic influence of religion

on social processes and the political use of ethno-cultural

schisms, which has impeded speedy modernization of the

society and has marred the démocratisation process.

130

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contesting Modernity: Crises of Démocratisation in South Asia

"Normally, the démocratisation process goes through four

stages. Decay of authoritarian regime, transition to

democracy, consolidation of democracy and maturity of

democracy." [Shin 1994] The polities of South Asia are

undergoing through different stages of démocratisation and

the entire region is not passing through the same stage.

Hence, the pace of démocratisation of the region is rather

sluggish. A glimpse at the current political dynamics in

different polities of the region will symbolise this

phenomenon.

To begin with, Maldives has yet to cross the first stage of

démocratisation that is decay of authoritarian regime. Since

independence, the country has been governed by two

successive authoritarian regimes, the first one led by Ibrahim

Nasir who ruled from 1968 to 1978 and Maumoon Abdul

Gayoom who has been ruling till date since 1978. The most

significant obstacle to the process of démocratisation has

been the inertia towards modernization exhibited by the

conservative Islamic clerics. "This stems from their aversion

to the Western model of development and the belief that

Islam and democracy cannot be reconciled." [Bashiriyeh 1993]

Hence for démocratisation of Maldives, secularization of

politics is crucial. The imperative is to bring reforms in Islam

as to make it more progressive and compatible to a modern

liberal society.

"However, there have been positive signs, as progressive

Islamists round the world are struggling to find viable

answers to the question of compatibility between democracy,

modernity and Islamic beliefs." (Wright 1996] This trend may

open up new horizons for a country like Maldives. Further,

Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal are at cross-roads, having

131

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sanjeev Kumar

to pass through dual stages of démocratisation that is

transition to democracy and consolidation of democracy. All

these countries have been frequently oscillating between

democratic and authoritarian regimes. Hence consolidation

of democracy is the major problem that these countries are

grappling with.

Bangladesh: an Epitome of an

Illiberal Democracy

"With the military takeover of the country in Í975, liberal

democracy saw an early death in Bangladesh. Since 1991,

successive phases of the country's own home-grown version

of democracy have been unhappy political experiments. In

present day Bangladesh, the term democracy has lost almost

all of its liberal characteristics." [Hossain 2005] Despite

satisfying the elementary conditions of a minimalist

democracy: "regular free and fair elections, accountability

of the State's apparatus to the people and effective guarantees

of expression and association." [Beetham 1994] "Bangladesh

has not made significant progress, to consolidate its

democratic institutions because the democratically elected

leaders have behaved in an autocratic manner, and used State

power to reward their supporters and punish their

opponents." [Jahan 2007]

Ever since the re-establishment in 1991, democracy in

Bangladesh has been fluid in character. The leaders of the

two main political parties, Begum Khaleda Zia of the

Bangladesh National Party and Sheikh Hasina of the Avami

League, have turned the country into a scaffolding to

decapitate the democratic architecture by their involvement

in fierce political confrontation. For the last one and half

132

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contesting Modernity: Crises of Démocratisation in South Asia

decades, the country has witnessed an opera of dynastic

feuds between the Avami League and the B.N.P. In addition

to this since 2001, Begum Khaleda Zia's B.N.P. attempted to

brace its position through a massive Islamisation drive which

has torn apart the secular fabric of Bangladesh's society. This

has not only impaired the modernization process, but it has

also considerably enfeebled the democratic institutions of

the country.

Above all, Bangladesh is rapidly emerging as a hub of

terrorism. "Some scholars and geo-political analysts feel that

the epicenter of the concept and practice of Islamist jihad,

has shifted from Pakistan to Bangladesh. It has emerged as

a critical breeding ground of Islamist jihad. Mushrooming

of jihadist Tanzeems from 1980 to 2005, apparently supports

these allegations. Escalation of violence, aimed at over-

throwing the constitutional democracy and establish a pure

Islamic State ruled by Sharia and Hadit, buttress such

tentative conclusions." [Dhar 2006]

The magnifying influence of Islamic extremism on the socio-

political spheres of Bangladesh, is likely to have serious

ramifications upon the security situation of the entire South

Asian region. The growing tensions on the Indo-Bangladesh

border, due to the drastic upsurge of insurgency into the

North-eastern region of India from Bangladeshi soil,

provides credence to this argument. "Now Bangladesh has

become the epicenter of propagating and promoting ultra-

Islamic fundamentalism and terrorism into the North-

Eastern region of India." [Pramanik 2006] This has not only

complicated the North-East quagmire, but it has sired fresh

strategic challenges for India in its Eastern border. There is

133

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sanjeev Kumar

high probability that the crisis in the North-East, may become

more volatile than the problem in Jammu & Kashmir.

Hence all these developments spawned a tumultuous

situation in Bangladesh, which has saturated into a political

impasse of the highest order in 2006 and drove the country

nearly into a massive civil war. In this predicament, the

military was compelled to take the centre stage, again

demonstrating the political bankruptcy of the country's

democratically elected leaders. Thus to invoke Rustow's

phrąse: "the structural national conditions that keep a

democracy functioning might not be the same factors that

brought democracy to the country in the first place." (Rusto w

1970] "A varied mix of economic and cultural dispositions

with contingent developments and individual choices

condition the nature of the democratic polity." [Anderson

1999]

This fittingly illustrates the reasons for the failure of

democracy in Bangladesh. The values that impelled the

national movement in 1971 and the people's movement

against the military regime in 1991 have been thrown into

thin air by a fractious political class and its unholy alliance

with the conservative religious extremists, leaving adequate

space for the military to meddle in civic affairs. Presently

Bangladesh is going through a scabrous phase, with its future

appearing obscure. The significant cause for the current state

of Bangladesh's politics seems to be the severe economic

inequalities that have bedeviled the country ever since its

independence. Poverty has been a bane on its society that

has bridled modernization process. More than three decades

of bad governance, did not help the cause of liquidating

poverty, in turn it has had a metastatic influence upon the

134

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contesting Modernity: Crises of Démocratisation in South Asia

entire polity. Even transition to democracy proved worthless

because "democracy is likely to endure when income

inequality is lower." [Przeworski 1991]

In addition to this, the whimsical character of its democratic

Governments has ridiculed the popular movement that

effected the transition to democracy. This has further baffled

the public and they are now confronting a civic dilemma

weather to oppose the military intervention in favour of a

moral claim for democracy, or support the military backed

establishment in its cathartic reform agenda, in order to deal

with the putrid state of the country's democracy. The

military's reform agenda also appears to be dubious, because

"the army is now speaking of building Bangladesh's own

brand of democracy." [The Daily Star 2007] All this does not

augur well for the prospects of constructing a liberal

democracy in Bangladesh. As [Linz 1997] argues: "the lack

of a constitutional spirit and of an understanding of the

centrality of the constitutional stability has been one of the

weaknesses of many illiberal third world democracies." This

statement aptly sums up the condition of democracy in

contemporary Bangladesh.

Democracy in Pakistan: Captive to the Military

or Held for Ransom by Islamic Extremists

Pakistan has been yet another accursed country of South Asia

where democracy has been battling to survive. In just over

six decades of its history, Pakistan has witnessed the

demolition of the democratic architecture on four occasions

and each time to be substituted by an autocratic military

regime. "More than any other new State, Pakistan has

experienced to an intense degree, all the crises of political

135

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sanjeev Kumar

development; the crises of identity, legitimacy, integration,

penetration, participation and distribution."[Ahmed 1982]

"The army has exploited this unsettled situation and wielded

considerable influence over the country's domestic politics

and foreign affairs." [Cohen 1983] "It has become more

deeply entangled in Pakistan's politics and economy under

Musharraf, making it even harder to circumvent or

sideline/'Markey 2007]

The key problem for Pakistan however has not been

establishing democracy, but it has been the problem of its

consolidation. " A consolidated democracy is one where none

of the major political actors, parties or organised interests,

forces, institution consider that there is any alternative to

the democratic process to gain power and that no political

institutions or groups have claim to veto the democratically

elected decision-makers."[Linz 1997] But in Pakistan, the

military has always fancied its chance of acquiring control

over civilian institutions, whenever the democratic

institutions have become flimsy due to the incompetence of

the political class.

The primary reason for this is that one of the most critical

problems that have bedeviled Pakistani civil society is the

dogmatic influence of Islamic extremism. It has not only been

a major hindrance to the modernization process, but its

omnibus presence has resulted in the unfolding of a

persistent threat of a Taliban like Islamic takeover of Pakistan.

This precarious situation has led the Pakistani citizenry into

a conundrum, where they may have to make a choice

between a weak democratic government which is always

vulnerable to the extremist pressures, or support a military

136

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contesting Modernity: Crises of Démocratisation in South Asia

regime which may be authoritarian but considered to be a

potential hedge against the extremists. "Hence in such a

predicament, the civil society comes to the in electable

conclusion that it would be better to support a military rule

which would at least prevent the worst case proposition of

State collapse and an Islamic takeover, rather than

commiserate a fragile democratic establishment under which

their existence itself may be in jeopardy." [Zaidi 2007]

The popular support that general Mushrraf was able to

commend, especially from the urban elite, in October 1999

after he dislodged the incompetent democratic establishment

of Navaz Sharif and assumed to himself all executive powers,

provides credence to the above argument. "The military has

never faced opposition while assuming power. In fact, it has

been invited by political parties and sections of public at

large. History is witness to the fact that military regimes in

Pakistan have not been thrown out of power by a mass

movement, but they themselves tend to retire from politics

when they rim out of steam. "[Ibid]

Anyhow, the problems of Pakistan do not end here itself.

"The most serious issue that has badgered Pakistani society

is the Mullah-military condominium. The military has often

shown a willingness to partner with the Islamists in order to

dominate domestic politics." [Markey 2007] This is the

greatest threat that contemporary Pakistan is facing. It not

only has retarded the modernization process, much due to

the wrecking tactics of the Islamists, but it has enhanced the

public dilemma in an exponential manner largely due to their

unflinching faith over the army as a savior against the

tempest of Islamic extremism and their growing

disenchantment towards the democratic institutions.

137

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sanjeev Kumar

This has led the people of Pakistan into a quagmire where in

they have been left with few choices. Mushraff's drive of

enlightened moderation appears to be a parody, considering

the magnifying influence of the Islamists on society and

politics. The assassination of Benazir Bhutto and the failed

assassination bid on Musharraf himself for two times by the

extremists exemplified the gravity of the situation. "The

growing Islamic sympathizers in the army, intelligence

services and the Government, presence of the Taliban in Fata

and Baluchistan regions, a steady rise in extremist mosques

and Madarasas, all symbolise the macabre." [Ibid] Pakistan

is now experiencing a crisis of nationhood. Indicative of this,

"Musharraf has made a shocking admission in his book In

The Line Of Fire that the degree of disintegration of Pakistan

is reaching such a severe level that, uniting the entire country

even in the time of a threat to national security seems to be

difficult." [Musharraf2006]

Hence purgation of the scourge of Islamic extremism is an

exigency for strengthening the process of démocratisation

in Pakistan. The impact of Islamic fundamentalism upon the

dynamics of domestic and foreign affairs of Pakistan has been

incredible. It has crept into the geo-strategic and political

equations of the country in such a profound manner that it

has led to the complication of one of the most critical security

problems of South Asia that is the conflict over Jammu &

Kashmir. For Pakistan, the conflict is not merely a defence

or foreign policy issue, but it has disconcertingly acquired

significance in its domestic space and it has been the most

popular agenda for the political parties for enhancing their

electoral gains.

Thus the political use of the Kashmir issue, Islamisation of

138

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contesting Modernity: Crises of Démocratisation in South Asia

the Kashmir conflict and military's disposition to strike an

unholy alliance with the Islamic extremists in the name of

accomplishing Pakistan's goals pertaining to Jammu &

Kashmir, have been the crucial factors that have engendered

the present domestic tumult in the country . It has not only

pushed Pakistan on the verge of a civil war, but also

prognosticates a horrendous international conflict that has

potential danger of a nuclear war. In a worst case proposition,

the perils may reach ghastly proportions if terrorists attain

access to nuclear weapons. Thus modernization of Pakistan

by ending the influence of Islamic fundamentalism, limiting

the role of the army to security affairs and restoration of

democracy and strengthening of the civilian institutions,

holds the key for not only the peace and development of

Pakistan, but of the entire South Asian region.

A review of the state of democracy in Maldives, Bangladesh

and Pakistan, reflects upon the fact that Islamic extremism

has been a common denominator in all the three countries,

when we attempt to identify the key factor that has retarded

the process of démocratisation. Islamic extremism has acted

as a countervailing force to modernisation and it has

contributed significantly to the half-baked modernity

syndrome existing in these three countries. "Modernity in

its cultural, political and economic dimension, is assumed

by the contemporary Islamic fundamentalists to have caused

the gradual decline of Islam, or its virtual disappearance as

an active force in international and State affairs. The

institutions and concepts of secularism and liberalism,

nationalism, Marxism and democracy, are blamed for

eroding the religion of Islam, leading them to forsake its way

of life to other ideologies and other Western

139

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sanjeev Kumar

models." [Choueri 2003] Thus, Islamic fundamentalism

advocates anti-thetical versions to contemporary paradigm

of modernity and this tendency has jeopardized the

démocratisation process in Maldives, Bangladesh and

Pakistan, to a considerable extent. This is primarily due to

the omnibus influence that Islamic extremism exercises, in

the socio-economic and political spheres of these countries.

Nepal and Sri Lanka:

Dangling in a Zone of Uncertainty

Now, let us consider yet another country that has struggled

to consolidate democracy. Nepal, the tiny Himalayan country

has been witnessing political instability for decades which

has smothered the process of démocratisation. The most

crucial hurdle in this regard has been the ideological friction

between liberalism of the democrats and authoritarianism

of monarchy and other conservative forces. This strife usually

ended in the regime being transformed into a royal autocracy,

by the declaration of emergency and royal take over of all

executive powers. At the time of emergency, the royal

Nepalese army was endowed with enormous powers,

resulting in all the descenting voices being pummeled

severely.

The chronic put schist tendency reflected by the power

paranoid monarchy and the fragile and self -seeking

democratic forces led to large scale public discontent which

basically seems to have fanned the reactionary left wing

Maoist rebellion that transpired in the 1990s. The severe

poverty and the hegemonic character of the caste based social

hierarchy, might have also played a vital role in intensifying

140

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contesting Modernity: Crises of Démocratisation in South Asia

the Maoist movement. After the royal massacre of 2001 and

the subsequent palace engineered deportations of the

democratic institutions, the civil war intensified. The problem

was compounded by the imponderable triangular struggle

between lhe authoritarian king Gyanendra, the self seeking

democrats and the reactionary Maoists, for the control of

the State.

The most nefarious thing here has been the contradiction of

perceptions that existed among the three claimants of power,

the monarchy, the Maoists and the democrats, regarding the

character of a democratic State. "Hence the existence of

competing and radically incommensurable ideals of

democracy that is the clash of visions, contributed

significantly to the gory civil war."[Gellener-2007] However

the morass has been ended by the people's movement of 2006

and now the country is passing through a phase of tectonic

transformation. But this period of transition still appears

dubious, as there prevails a high degree of uncertainty

regarding the form of Governmental arrangement that the

Seven Party Alliance would ultimately agree upon.

Further, if we look at Sri Lanka, it may be stated that the

most crucial impediment in the way of démocratisation, is

the ethnic conflict that has dominated all facets of Sri Lankan

politics. It remains as one predominant force that has shaped

the contemporary domestic and foreign affairs of the country.

The rampant civil war has not only undermined the authority

of the State, but also has created a productive ground for

outside powers to meddle in its internal affairs. Worst, the

Sri Lankan disenchantment with India after the 1987 fiasco,

allowed the powers outside of South Asia such as Britain,

Norway and even the United States in recent times, to

141

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sanjeev Kumar

maneuver the affairs of South Asia for their own

advantage.

Hence, the ethnic unrest in Sri Lanka and India's inability to

affect a solution, seems to be an ideal platform for the major

powers like the United States to look for new avenues for

attaining a strategic advantage in the region. The ten year

Acquisition and Cross Servicing Agreement arrived at by

the U.S. with Sri Lanka on March 5 2007, provides one

example of the growing strategic interactions between the

two countries. These developments will not only have a

major impact ori South Asian dynamics, but will have

profound ramifications upon the politics of the Indian Ocean.

In this context, it is critical to highlight these developments

because Sri Lankan leadership by engaging major powers

in the country's domestic space, has illustrated its incapacity

to solve the current impasse by itself. This has resulted in

not only the undermining of State power, but also led to the

growing strength of a hegemonic fringe of Sinhalese

nationalists.

They have acted as a major pressure group in Sri Lanka and

worked towards determining the contours of national politics

for their own advantage; that is to perpetuate the hegemony

of the Sinhalese in the socio-economic and political spheres

of the country. The two major political parties the United

National Party and the Sri Lankan Freedom Party, have also

done enough to complicate the morass. The quest for finding

an amicable solution to the ethnic conflict has turned out to

be an illusion because both political parties have attempted

to make maximum political capital out of the crisis, rather

than to make a sincere endeavour for bringing a speedy

solution through consensus. This has been apparent in their

142

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contesting Modernity: Crises of Démocratisation in South Asia

penchant towards bolstering the Sinhalese nationalists'

endeavours to perpetuate the hegemony of the Sinhalese.

Both parties have played the ethnic card dexterously for

acquiring political mileage.

"Neil DeVotta has called the broad framework of this process

as 'politics of ethnic outbidding'. It is this politics of ethnic

outbidding, electoral competition between UNP. and SLFP

to persuade Sinhalese voters, that they are the best equipped

to ensure Sinhalese dominance, that marginalized the Tamils

from the State, reinforced the ideology of Sinhalese ethnic

and political supremacy and eventually created conditions

for Tamil separatist insurgency. The "politics of ethnic

outbidding thus, generated a pan-Sinhalese consensus for

Sinhalese ethnic hegemony in the polity." [Uyangoda 2007]

Hence the civil war in Sri Lanka, has not only 'ripped the

country into two hostile segments, but also' has throttled the

modernization process. This has acted as a major impediment

in the process of consolidating and stabilizing democracy in

the country.

"Ethnic outbidding for power and ruling class vacillation

has been a deadly combination for a political solution. That

sadly is how democracy has been working in Sri Lanka. It

maybe called a democracy that has facilitated the hegemony

of the fringe." [ibid]

Such hegemonic tendencies of an extremist minority, has

been a bane on the prospects of modernization and

démocratisation in South Asia. "The disproportionate power,

that the nationalist or the religionist fringe appears to exercise

over the mainstream political parties or institutions,

constitutes an enduring paradox in at least three South Asian

143

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sanjeev Kumar

countries- Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. The paradox

is that the ethno-religious extremist parties often claiming

to represent the interests of the numerically majority

community, might not even get a few percent of votes in

democratic elections. Nevertheless, they have acquired the

ability to shape the national political debate. That is why

despite their weak electoral strength, the mainstream political

parties, the bureaucracy, the media and even the judiciary

often capitulate before them." [ibid]

Thus restoration and maintenance of peace and security in

the region, and the stability of democratic institutions in

various countries of South Asia, largely rests upon the

amicable solution to the ethno-religious conflicts in various

countries of the region. Ethnicity and religion have played a

critical role, in engendering internal cleavages in the polities

of South Asia, and also have steered-up fierce international

tensions, at the regional level. The repercussions of the ethno-

religious conflicts have been catastrophic; be it the violence

unleashed at the time of India's partition, or the India-

Pakistan conflict over Jammu & Kashmir; all indicate towards

the hideous impact that relegio-civilisational divergences

have produced.

Indian Democracy: A Search for Maturity

India has been the only country of South Asia that has been

able to consolidate and stabilize democratic institutions.

Anyhow, India has not been able to produce a vibrant and a

matured democracy, which can be claimed to be anything

parallel to that of the polities of the developed West. "The

working of Indian democracy is replete with conundrums,

which do not admit to easy judgment. There are both

144

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contesting Modernity: Crises of Démocratisation in South Asia

spectacular gains and dismal failures, significant

achievements in advancing political equality, and equally

significant drawbacks, in establishing political accountability.

Indian democracy has a mixed record, not because it is flawed

but because it is in process." [Desouza 200 7] This implies that

India is still in the process of a search for maturity of its

democracy. It has not yet succeeded in reaching a stage,

wherein it may be perspicuously termed as a flawless and a

full fledged democracy.

One of the most crucial difference between the democracies

of the West and that of India, is pot the problem of

establishing or consolidating democratic institutions, the

problem that India's South Asian neighbours are facing ever

since their inception as sovereign States. But the focal point

of difference could be traced in the country's history.

According to Sudipta Kaviraj "one of the most crucial factors

that facilitated the British to colonise India, was the lack of

discipline and civic sense, or what Foucault has called

'Governmentality', among Indians. The British

providentially possessed these qualities and hence were able

to colonise such a large country. "[Kaviraj 20051 "The

situation was compounded, because of the existence of a

feudal society in colonial India." [Guha 1998] It must be noted

here that the birth of a modern democratic State in

India, was not coincided by the ending of feudalism. This

meant that the onus of bringing capitalist economic

transformation was left to the nascent democratic State.

"Indeed, in the Indian context, as distinct from the European,

the democratic State became the primary source of

modernity." [Kaviraj 2005]

145

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sanjeev Kumar

This according to me, is contrary to what has happened in

the West. The democratic State in the West has been the

product of modernity, dissimilar to the Indian case, where

the democratic State was expected to invigorate the process

of modernization. "In the West, real democracy came to a

capitalist society, which was already economically converted

into a capitalist form of production and already fairly

wealthy. The industrial working force was much larger, than

that of the agricultural sector."[Kaviraj 2000] Comparatively,

Indian democracy at the outset, encountered an agrarian

society with a much smaller industrial sector and an adjunct

poverty. "So, democratic politics primarily became a tool for

advancing the cause of promoting the grant of subsidies for

agriculture, rather than contemplating upon building a

thriving industrial-capitalist economy." [Warshney 1999]

Yet another aspect to be reckoned is that "the democratic

institutions in India did not have a historical preparation,

through a political discourse which was debated in the

vernaculars and in terms which reached the ordinary Indian

citizens." [Kaviraj in Hassan 2000] This historical lacuna and

the continuation of feudal structures of domination bolstered

by the existence of a predominantly agrarian society, largely

contributed to the persistence of lack of 'Governmentality'

among Indians, even in the post-colonial State. This also

facilitated the newly crafted politico-bureaucratic

architecture, to gain excessive control over the realm of public

affairs. "The introduction of a planned economy and the

Government's policies that sanctioned the creation of a large

public sector of core industries, further led to the enormous

expansion of bureaucratic influence on the developmental

affairs of the country." [Potter 1986]

146

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contesting Modernity: Crises of Démocratisation in South Asia

"This extension of public bureaucracy, was however fraught

with dangers and difficulties. The bureaucracy, though now

manned by Indians, was still the unreconstructed

bureaucracy of colonial State-unresponsive, irresponsible,

insufficiently used even to the rhetoric of serving the people,

being habituated for so many decades to being their lords

and masters. It was also eminently unsuited in its original

form to perform modern welfare functions." [Kaviraj in

Hassan 2000] Despite, subsequent reforms, the bureaucracy

in India has not entirely shelved its colonial legacy and given

over its innate feudal psyche. This considerably led to the

relatively sluggish pace of industrialization and growth in

post-independent India. This trend continued till the 1990s,

when the policies of market liberalization were initiated.

"The neo-liberal reforms initiated off late, is directed not only

towards re-working the relationship between State, market

and civil society, but is also aimed at restructuring the State

in order to incorporate the market rationality in the

organisation and functioning of the State."(Joseph 2007] But

even then, it is felt here that there seems to be a scant

reduction in the colonial behaviour of the bureaucracy and

still it does not seem to have been liberated from the feudal

psyche. Consider the recent bureaucratic resistance towards

certain sections of the newly charted right to information

act, which perspicuously established the hitherto existence

of a sense of class consciousness among the bureaucrats.

Hence anthropologists researching on the Indian State have

noted that the State behaviour in India does not correspond

with that of the State behaviour in the developed West. In

this regard, it has been argued that "in India, one of the

modern State's principle institutions, the bureaucracy,

147

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sanjeev Kumar

behaved in ways very different from its European

counterpart, and differently from the theoretical picture of

behaviour constructed so powerfully by the Weberian model

of rational-legal authority. Under the pressures of modernity,

the Indian State however has gone through serious stages of

successive elaboration, but it is hard to be confident that it is

coming to resemble the model of Weberian bureaucratic

State." [White 2002]

Thus in the early years of India's independence, State

controlled capitalism with an excessive influence of

bureaucracy upon developmental affairs, led to the

procrastination of the process of building a robust industrial

economy. This phenomenon considerably led to the enduring

of the half -baked modernity syndrome and resulted in the

stalling of India's progress towards engineering a mature

democracy. The recent policies of market liberalization and

neoliberal reforms have merely been a sought of damage

control exercise and still a large hiatus exists between India

and the vibrant democracies of the developed West. In view

of this, it has been argued: "tangible institutions of the State

may be helpless against the intangible force of historically

sedimented cultural understandings of ordinary people.

Long-term memories and time-tested ways of dealing with

power of the political authority took its revenge on the

modern State, bending the straight lines of rationalist liberal

politics through a cultural refraction of administrative

meaning. The logic of new legislations was twisted to

produce strange travesties." [Kaviraj in Hasan 2000]

Apart from this, another societal attribute that has choked

the pace of modernization, is the dogmatic orthodoxy of a

caste based social hierarchy. This seems to be a predominant

148

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contesting Modernity: Crises of Démocratisation in South Asia

peculiarity that has fundamentally contributed to the

perseverance of a half-baked modernity syndrome which has

afflicted speedy transition of the Indian polity into a ripe

democracy. This rather has been a significant difference that

endures, between the vibrant democratic polities of the

developed West and the immature Indian democracy.

"Indian society, primarily dominated by the Hindu social

order based on caste, has been characterised by interior

organisation and this form of social order is purely interior,

anterior to the external authority of the State."

[Mukhopadhyay 1981] "In the Indian caste system, the social

meanings are integrated and hierarchical." [Walzer 1983]

Caste system exists as an anti-modernist force, retro-grading

the process of building a modern liberal society. As the caste

hierarchy is an antiquity, it preceded the birth of a modern

State like India. "Everyone recognizes that the traditional

social system in India was organised around caste structures

and caste identities."[Kothari 2001] and the modern State

with its social emancipatory potential, was expected to act

as a modernizing force and an agent of social change.

Establishing an egalitarian society thus became one of the

foremost challenges of post-colonial State in India.

"However in dealing with the relationship between caste and

politics, it should be recognized that a modernizing society

is neither modern nor traditional. It simply moves from one

threshold of integration and performance to another, in the

process, transforming both the indigenous structures and

attitudes and the newly introduced institutions and ideas.

"(Ibid] In view of this, it could be argued that the emergence

of the modern State in India did not mean that the traditional

social structures entirely disappeared. In turn, archaic social

149

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sanjeev Kumar

structure, determined by caste system began to impose itself

upon politics and social dynamics. "Political and

developmental institutions do not anywhere function in a

vacuum. They tend to find bases in society either through

existing organizational forms, or by invoking new structures

that cut across these forms." [ibid]

Thus caste system in India has its own impact on modern

politics or vice versa, modern politics in India has tended to

condition itself in accordance with a caste oriented society.

Henceforth, caste and politics seem to be inextricably linked

up with each other. Castism in politics and politicization of

caste, are two distinct propositions that feed upon each other

in a vicious cycle. Its impact has been mordacious, resulting

in the polarization of the Indian society. This trend is still a

part of modern India, despite neo-liberal reforms, directed

towards achieving the prodigious goal of becoming a mega

industrial-capitalist economy. Ending of caste based social

inequalities was one of the foremost challenges for post-

independent India. Lamentably, despite constitutional

fantasy of constructing an egalitarian society through

affirmative action, existence of caste based social disparities

is still a hard reality and subaltern emancipation has

remained as a fictitious dream. As a contrast caste has become

a crucial political weapon, in the post-independent Indian

politics and has been instrumental in determining political

equations in the process of shaping and sharing power. Upon

societal affairs, its influence is even more gargantuan. It has

emerged as a dominant discourse and a source of hegemony

and any expression against this dominant discourse, is

largely considered as heresy.

However in the ultimate analysis, the report card of Indian

150

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contesting Modernity: Crises of Démocratisation in South Asia

democracy is relatively better than its South Asian

neighbours. It has been successful in holding on to its

democratic institutions and has checked any chance of

degeneration to any kind of civilian or military autocracy.

There are several other anti-modernist forces such as cultural

chauvinism and linguistic fanaticism, which have not been

mentioned above. Their influence upon the process of

démocratisation also has been one of regression, but the

detrimental impact of the factors discussed at length above,

seems to be irretrievable. They appear to have suffocated

Indian democracy, right at the stage when it was about to

attain complete maturity and development.

Conclusion

In a final analysis, it may be viewed that modernization by

ending traditional structures of social hegemony, is the

pressing requirement for, peace, security and stability of

South Asia. Until this happens, prospects for démocratisation

of the region appear nebulous. Significantly, because of the

traditional forces of dominance that have fiercely contested

the doctrines of modernity with an adherence to archaic

socio-cultural framework and politico-economic principles.

This has rendered the polities of South Asia to be mired in

history and squint their national visions. Prioritisation of

parochial loyalties such as caste, religion or language over

that of the nation-State, has produced catastrophic

consequences. This tendency ultimately has strongly

deterred the process of démocratisation, by affecting socio-

cultural transformation which is an urgent imperative for

modernization. Above all, the existence of asymmetry in the

levels of techno-economic development and diverse kinds

of socio-cultural dichotomies among the polities of South

151

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sanjeev Kumar

Asia has rendered the overall démocratisation of the entire

region, into a sort of cognitive complexity.

References

■ Ahmed, Manzooruddin, ed., Contemporary Pakistan politics ,

economy and society , Oxford University press, Karachi, 1982.

■ Anderson, L.,ed., Transition to democracy , Cambridge

University press, New York, 1999.

■ Bangladesh to have own brand of democracy, The Daily Star,

3 April, 2007.

■ Bashiriyeh, H., Aql dar Siyasat , {Reason in politics) Negah-e

Moaser publication, Teheran, 1993.

■ Beetham, David, Defining and measuring democracy, Sage,

London, 1994.

■ Carothers, T., Aiding democracy abroad : the learning curve, The

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington

DC, 1999.

■ Chakravarti, Dipesh, Provincialising Europe, Princeton

University press, Princeton, 2002.

■ Choueiri, Youssef, Islam and Fundamentalism, in 'Roger

Eatwell and Anthony Wright ed, Contemporary political

ideologies, Rawat publishers, New Delhi, 2003.

■ Cohen, Stephen P., Pakistan: army society and security, Asian

affairs, 10(2), Summer, 1983.

■ Desouza, Peter Ronald, The Indian common sense of

democracy, Seminar, 576, August 2007.

■ Dhar, M.K., Bangladesh: a need to rediscover the secular

forces, World Focus, 314, February 2006.

■ Diamond, L., Introduction : a search for consolidation, in L.

Diamond M. E. Plattner, Y, H. Chu, H. M. Tien, ed,

Consolidating the third wave democracies: regional challenges,

Johns Hopkins University press> Baltimore, 1997.

152

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contesting Modernity : Crises of Démocratisation in South Asia

■ Eisenstadt, S.N., Multiple modernities, Daedlus, Winter 2000.

■ Fukuyama, Francis, End of history and the last man, Free Press,

New York, 1992.

■ Gaonkar. Dileep, ed., Alternative modernities, Duke University

press, 2001.

■ Gellner, N.N. Democracy in Nepal: four models, Seminar, 5)6,

August 2007.

■ Guha, Ranajit, Elementary aspects of peasant insurgency in

colonial India, Oxford University press, New Delhi, 1998.

■ Harriss- White, Barbara, India working, Cambridge University

press, Cambridge, 2002.

■ Held, David, ed., Prospects for democracy, Stanford University

press, California, 1993, p.13.

■ Hossain, Moazzem, Home-grown democracy, Economic and

Political Weekly, 41 (9) March 4-10 2006.

■ Huntington, Samuel P., The third wave: démocratisation in the

late Twentieth century ; Oklahoma University press, Norman,

1992.

■ Inglehart R. and Carbello, M., Does Latin America exist and

is their a confusion culture? A global analysis of cross-cultural

differences, Political science and politics, 30(1) 1997.

■ Jahan, Rounaq, Bangladesh at a crossroads, Seminar 576,

August, 2007.

■ Joseph, Sarah, Neoliberal reforms and democracy in India,

Economic and Political Weekly, 42(31) August 4-10 2007.

■ Kaviraj, Sudipta, Modernity and polities in India, Daedalus,

Winter, 2000.

at a seminar on ' The State', at Colum

2005.

153

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sanjeev Kumar

and the State in India, Sage, New Delhi,

2000.

■ Kohli, Atui, Crisis of governability, in Sudipta Kaviraj ed.,

Politics in India, Oxford University press, New Delhi, 1999.

■ Kothari, Rajni, ed., Caste in Indian politics, Orient Longman,

Hyderabad, 2001.

■ Linz, Jaun J., Democracy today, Scandinavian political studies,

20(2), 1997.

■ Markey, Daniel, A false choice in Pakistan, foreign affairs, 86(4)

July- August 2007.

■ Mukhopadhyay, Bhudev, Samajik Prabandha, (social essays),

Paschim Bangai Pustak Parshad, colcotta, 1981.

■ Mushrraf, Pervez, In the line of fire, Simon and Schuster,

London, 2006.

■ O-Loughlin, Jhon, Global démocratisation: measuring and

explaining the diffusion of democracy, in Clive Bamett and

Murray Lowed, Spaces of democracy : geographical perspectives

on citizenship, participation and representation, Sage, London,

2004.

■ Potter, David, India's political administrators, Clarendon press,

Oxford, 1986.

■ Pramanik, Bhimal, Demographic shifts in Bangladesh and its

impact in the East and North-East India, World Focus, 314,

February 2006.

■ Przeworski, Adam, Democracy and the market : political and

economic reforms in Latin America and Eastern Europe,

Cambridge University Press, New York, 1991.

■ Rustow, D.A, Transitions to democracy: towards a dynamic

model, Comparative Politics, 2(3) 1970.

■ Schwartzman, K.C., Globalisation and democracy, Annual

review of sociology, 24, 1998.

■ Shin, Doh Chull, The third wave of démocratisation: a

154

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contesting Modernity: Crises of Démocratisation in South Asia

synthesis and evaluation of recent theory and research, World

politics, 47, October 1994.

■ Uyangoda, Jayadeva, Sri Lanka: democracy and the

hegemony of the fringe, Seminar, 576, August 2007.

■ Varshney, Ashutosh, Democracy in the country side ; Cambridge

University press, Cambridge, 1999.

■ Walzer, Michael, Spheres of justice: a defence of pluralism and

equality, Basic books, New York, 1983€

■ Wright, Robin, Islam and liberal democracy: two visions of

reformation, Journal of Democracy, 7(2) 1996.

■ Zaidi, S. Akbar, Is Pakistan a democracy? Seminar, 576, August

2007.

■ Zakria, Fareed, The rise of illiberal democracy, Foreign Affairs,

76(6), 1997.

■■

155

This content downloaded from

54.252.69.139 on Thu, 29 Jun 2023 07:34:24 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- He Puapua: Report of The Working Group On A Plan To Realise The UN Declaration On The Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Aotearoa New ZealandDocument34 pagesHe Puapua: Report of The Working Group On A Plan To Realise The UN Declaration On The Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Aotearoa New ZealandJuana AtkinsNo ratings yet

- Democracy in Southeast Asia: Between Discontent and HopeDocument13 pagesDemocracy in Southeast Asia: Between Discontent and HopeThe Wilson CenterNo ratings yet

- Mass Mobilisation Joya HasanDocument10 pagesMass Mobilisation Joya HasankhoobpadhoNo ratings yet

- A Geograpic Study of KashmirDocument17 pagesA Geograpic Study of KashmirAbdullah Zubair MirNo ratings yet

- German Yearbook: Feminist Studies in German Literature & Culture4, No. 1 (1988) : 83-95Document2 pagesGerman Yearbook: Feminist Studies in German Literature & Culture4, No. 1 (1988) : 83-95Nika SedaghatiNo ratings yet

- Rizvi DemocracyGovernanceCivil 1994Document33 pagesRizvi DemocracyGovernanceCivil 1994dionessa.bustamante09No ratings yet

- Tudor ExplainingDemocracysOrigins 2013Document21 pagesTudor ExplainingDemocracysOrigins 2013aayshaahmad743No ratings yet

- Christie IlliberalDemocracyModernisation 1998Document18 pagesChristie IlliberalDemocracyModernisation 1998alicorpanaoNo ratings yet

- The George Washington University Institute For Ethnographic Research Anthropological QuarterlyDocument12 pagesThe George Washington University Institute For Ethnographic Research Anthropological QuarterlyghisaramNo ratings yet

- Modernity & Politics in IndiaDocument27 pagesModernity & Politics in IndiaKeshor YambemNo ratings yet

- sudipta kavirajDocument27 pagessudipta kavirajgaurikasoni8No ratings yet

- Determinants of Democracy in The Muslim WorldDocument27 pagesDeterminants of Democracy in The Muslim Worldmariasophiaysabelle2No ratings yet

- Comparative Politics, Ph.D. Programs in Political Science, City University of New York Comparative PoliticsDocument21 pagesComparative Politics, Ph.D. Programs in Political Science, City University of New York Comparative PoliticsElena RomeoNo ratings yet

- Democracy in Central Asia: Competing Perspectives and Alternative StrategiesFrom EverandDemocracy in Central Asia: Competing Perspectives and Alternative StrategiesNo ratings yet

- Chat Week 5Document51 pagesChat Week 5Raghaw KhattriNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 14.139.213.147 On Tue, 17 May 2022 05:03:36 UTCDocument8 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 14.139.213.147 On Tue, 17 May 2022 05:03:36 UTCChirantan KashyapNo ratings yet

- Levitsky Way 2006Document23 pagesLevitsky Way 2006Guadalupe MascareñasNo ratings yet

- Elite FactorDocument20 pagesElite FactorvazirekeeyaNo ratings yet

- Modernity and Politics in IndiaDocument27 pagesModernity and Politics in Indiaarun_shivananda2754No ratings yet

- India International Centre India International Centre QuarterlyDocument14 pagesIndia International Centre India International Centre Quarterlyzakir aliNo ratings yet

- Hewson & Rodan, The Decline of The Left (Socialist Register, 1994)Document28 pagesHewson & Rodan, The Decline of The Left (Socialist Register, 1994)Hassan as-SabbaghNo ratings yet

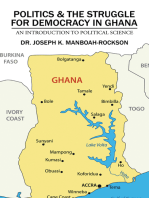

- Politics & the Struggle for Democracy in Ghana: An Introduction to Political ScienceFrom EverandPolitics & the Struggle for Democracy in Ghana: An Introduction to Political ScienceNo ratings yet

- Routledge Handbook of Civil and Uncivil Society in Southeast - Eva Hansson, Meredith L. WeissDocument18 pagesRoutledge Handbook of Civil and Uncivil Society in Southeast - Eva Hansson, Meredith L. Weissaldi khoirul mustofaNo ratings yet

- Mohan and StokkeDocument23 pagesMohan and StokkeRakiah AndersonNo ratings yet

- Economic and Political CrisisDocument5 pagesEconomic and Political Crisisnbaig786No ratings yet

- Democracy and Violence in BrazilDocument40 pagesDemocracy and Violence in BrazilYing LiuNo ratings yet

- Lucian Pye On Social Capital and Civil SocietyDocument21 pagesLucian Pye On Social Capital and Civil SocietyDayyanealosNo ratings yet

- Unit V - C - Can Democracies Accomodate Ethnic Nationalities - Unit 8Document40 pagesUnit V - C - Can Democracies Accomodate Ethnic Nationalities - Unit 8Arrowhead GamingNo ratings yet

- The Limits of Civil Society in Democratising The State: The Malaysian CaseDocument19 pagesThe Limits of Civil Society in Democratising The State: The Malaysian CasephilirlNo ratings yet

- Dissecting The Theories of DevelopmentDocument6 pagesDissecting The Theories of DevelopmentkumbiraithierrynNo ratings yet

- Taylor & Francis, LTD., Oxfam GB Development in PracticeDocument10 pagesTaylor & Francis, LTD., Oxfam GB Development in PracticeAditya MohantyNo ratings yet

- Rise of The Dalits and The Renewed Debate On CasteDocument7 pagesRise of The Dalits and The Renewed Debate On CasteRaees MohammedNo ratings yet

- Globalisation Good Governance and Democracy - The InterfaceDocument10 pagesGlobalisation Good Governance and Democracy - The InterfaceBijit BasumataryNo ratings yet

- Towards Good Governance A South Asian PerspectiveDocument18 pagesTowards Good Governance A South Asian PerspectiveMuhammad AdeelNo ratings yet

- Democracy in East & Southeast AsiaDocument8 pagesDemocracy in East & Southeast AsiaalixcurtinNo ratings yet

- Rich Democracies Political Economy, Public Policy, and PerformanceDocument6 pagesRich Democracies Political Economy, Public Policy, and PerformancenekhosteamNo ratings yet

- Kothari RiseDalitsRenewed 1994Document7 pagesKothari RiseDalitsRenewed 1994Dhritiraj KalitaNo ratings yet

- Sec.1.1the Third Wave in East Asia: Comparative and Dynamic PerspectivesDocument41 pagesSec.1.1the Third Wave in East Asia: Comparative and Dynamic PerspectivesPhilem Ibosana SinghNo ratings yet

- American Society of International LawDocument17 pagesAmerican Society of International LawCarlos Hernan Gomez RiañoNo ratings yet

- Africa: Does Democracy Guarantee Development?: September 2014Document4 pagesAfrica: Does Democracy Guarantee Development?: September 2014kaleem ullahNo ratings yet

- African Association of Political ScienceDocument30 pagesAfrican Association of Political ScienceJorge Acosta JrNo ratings yet

- The Global Commonwealth of Citizens: Toward Cosmopolitan DemocracyFrom EverandThe Global Commonwealth of Citizens: Toward Cosmopolitan DemocracyNo ratings yet

- Kamuzu's Legacy: The Democratization of Malawi: or Searching For The Rules of The Game in African PoliticsDocument32 pagesKamuzu's Legacy: The Democratization of Malawi: or Searching For The Rules of The Game in African PoliticsOswald MtokaleNo ratings yet

- Devadasis Dharma and The StateDocument11 pagesDevadasis Dharma and The StatePriyanka MokkapatiNo ratings yet

- Democracy and The Paradox of Zimbabwe: Lessons From Traditional Systems of GovernanceDocument13 pagesDemocracy and The Paradox of Zimbabwe: Lessons From Traditional Systems of GovernancePhil Da Mcee JacobsNo ratings yet

- American Political Science AssociationDocument19 pagesAmerican Political Science AssociationEsteban GómezNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Social Change: The Politics of Social DevelopmentDocument13 pagesApproaches To Social Change: The Politics of Social DevelopmentDiego ArcadioNo ratings yet

- Kim STATECIVILSOCIETY 2001Document21 pagesKim STATECIVILSOCIETY 2001Kiều Chinh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Challenges To Democracy and Governence-1 PDFDocument7 pagesPakistan Challenges To Democracy and Governence-1 PDFsyeduop3510No ratings yet

- Caldeira, T. y Holston J. Democracy and Violence in BrazilDocument40 pagesCaldeira, T. y Holston J. Democracy and Violence in BrazilCésarAugustoBernalGonzalezNo ratings yet

- INRS Literature Review 6Document35 pagesINRS Literature Review 6Akhona Bella NgubaneNo ratings yet

- South Africas Transition To Democracy and Democratic Consolidation - A Reflection On Socio Economic ChallengesDocument6 pagesSouth Africas Transition To Democracy and Democratic Consolidation - A Reflection On Socio Economic Challengeschhavi.katyalNo ratings yet

- POLITICAL MODERNISATION _ THE CONCEPT, CONTOURS AND DYNAMICSDocument14 pagesPOLITICAL MODERNISATION _ THE CONCEPT, CONTOURS AND DYNAMICSKeichi Yamane (KeichitheJackal)No ratings yet

- Democracy in Pakistan P2Document5 pagesDemocracy in Pakistan P2fayyaz anjumNo ratings yet

- Aristotelian Notion of Democracy and Its Reference To South SudanDocument14 pagesAristotelian Notion of Democracy and Its Reference To South SudanAnastasio NyagaNo ratings yet

- Authoritarian Innovations: DemocratizationDocument16 pagesAuthoritarian Innovations: DemocratizationTeguh V AndrewNo ratings yet

- The Role of Civil Society in Contributing To Democracy in BangladeshDocument14 pagesThe Role of Civil Society in Contributing To Democracy in BangladeshMostafa Amir Sabbih100% (1)

- Democracy Is Not For EveryoneDocument7 pagesDemocracy Is Not For EveryoneClarisse Demigod SegubanNo ratings yet

- The State-in-Society Approach To Democratization With Examples From JapanDocument30 pagesThe State-in-Society Approach To Democratization With Examples From JapanJoyrel SisanteNo ratings yet

- Modernization From Above - Social Mobilization Political InstitutDocument114 pagesModernization From Above - Social Mobilization Political InstitutAbhigya PandeyNo ratings yet

- RLS - Call For Applications - Authoritarianism and Counter-StrategiesDocument8 pagesRLS - Call For Applications - Authoritarianism and Counter-StrategiesPablo PabloNo ratings yet

- Angelica Democracy AssignmentDocument8 pagesAngelica Democracy AssignmentRudo MahambaNo ratings yet

- Edu Sci - IJESR-The Success of Indian Democracy With Multicultural Society An Inspiration For Developing CountriesDocument10 pagesEdu Sci - IJESR-The Success of Indian Democracy With Multicultural Society An Inspiration For Developing CountriesTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Meningkatkan Kemampuan Mendengar Melalui Audio-Visual Untuk Menambah Vocabulary (Kosa Kata) Bahasa Inggris Bagi Siswa Kelas Vii SMPN 21 PekanbaruDocument6 pagesMeningkatkan Kemampuan Mendengar Melalui Audio-Visual Untuk Menambah Vocabulary (Kosa Kata) Bahasa Inggris Bagi Siswa Kelas Vii SMPN 21 PekanbaruAsnidar DuhaNo ratings yet

- Why Bother With Elections? - Adam Przeworski: Chapter 1 - IntroductionDocument20 pagesWhy Bother With Elections? - Adam Przeworski: Chapter 1 - IntroductionEugenia WahlmannNo ratings yet

- Paika Rebellion, The - A Documentary Study (Odisha State Archives, 2017) FWDocument741 pagesPaika Rebellion, The - A Documentary Study (Odisha State Archives, 2017) FWsusant18No ratings yet

- Latihan RSPC CopyreadingDocument8 pagesLatihan RSPC CopyreadingScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- 04 AM2022 KoreanPeninsulaDocument42 pages04 AM2022 KoreanPeninsulaThaisa VianaNo ratings yet

- B.ed Reading and Writing (Second Terminal Exam)Document3 pagesB.ed Reading and Writing (Second Terminal Exam)Tech YoutuberNo ratings yet

- RPHDocument21 pagesRPHAnjo M. MapagdalitaNo ratings yet

- Ikenberry - From Hegemony To The Balance of PowerDocument12 pagesIkenberry - From Hegemony To The Balance of PowerAnand Krishna G Unni hs18h007No ratings yet

- How To Offer and Buy Something in EnglishDocument13 pagesHow To Offer and Buy Something in EnglishGodingo GrysweraNo ratings yet

- Liberalism (International Relations) - WikipediaDocument20 pagesLiberalism (International Relations) - WikipediaHareem fatimaNo ratings yet

- GE6101 - Readings in Philippine History (Answers)Document13 pagesGE6101 - Readings in Philippine History (Answers)Anna Joy YlaganNo ratings yet

- Click Here For Judge Search: Updated: November 13, 2018Document28 pagesClick Here For Judge Search: Updated: November 13, 2018Mikhael Yah-Shah Dean: VeilourNo ratings yet

- Textbook The Kremlin Letters Stalin S Wartime Correspondence With Churchill and Roosevelt David Reynolds Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook The Kremlin Letters Stalin S Wartime Correspondence With Churchill and Roosevelt David Reynolds Ebook All Chapter PDFdonna.riebel227100% (3)

- ProfileDocument4 pagesProfileapi-533828979No ratings yet

- 1940 To 1947Document21 pages1940 To 1947Mohammad TalhaNo ratings yet

- Exposure To Opposing Views On Social Media Can Increase Political PolarizationDocument6 pagesExposure To Opposing Views On Social Media Can Increase Political PolarizationJuliana Montenegro BrasileiroNo ratings yet

- Officer Citation Summary Report: Created Date: 10/26/2023Document6 pagesOfficer Citation Summary Report: Created Date: 10/26/2023ol_49erNo ratings yet

- Toril Moi - I Am Not A Feminist, But SummaryDocument2 pagesToril Moi - I Am Not A Feminist, But SummaryAucklandUniWIPNo ratings yet

- Premchand and NationalismDocument6 pagesPremchand and NationalismAida ArosoaieNo ratings yet

- Cutlist of M.A (Semester-III) of All Subjects (Private and Distance Education) Exam Held in December 202212-12-2022,03!50!43pmDocument186 pagesCutlist of M.A (Semester-III) of All Subjects (Private and Distance Education) Exam Held in December 202212-12-2022,03!50!43pmlovepreet singhNo ratings yet

- ACC AppintmentDocument3 pagesACC AppintmentNewsinc 24No ratings yet