Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Conway

Conway

Uploaded by

ScafOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Conway

Conway

Uploaded by

ScafCopyright:

Available Formats

Research and Development

Improving sleep quality for

patients after cardiac surgery

Aaron Conway is Registered Nurse in Cardiac Catheter Theatres, The Wesley Hospital, Auchenflower, Queensland,

Australia; Monica Nebauer is Senior Lecturer/Nursing Masters Courses Coordinator, School of Nursing and Midwifery,

Australian Catholic University, Banyo, Queensland; Paula Schulz is Senior Lecturer, School of Nursing and Midwifery,

Australian Catholic University. Email: Aaron.conway@uchealth.com.au

leep is recognized as an essential requirement for fatigued. Therefore, to promote recovery from cardiac

S health and recovery as the sleep-wake cycle

influences and regulates physiological function and

behavioural responses (Crisp and Taylor, 2001). Post-

surgery, it is important to consider interventions that will

limit fatigue through an improved sleep experience.

Complementary therapies may be one method of

cardiac surgery patients experience disturbed sleep, which improving sleep for this population of patients. However,

consequently inhibits their recovery through disruption to there is a lack of research into this topic. This study there-

their physical and psychological function (Redecker, fore aimed to identify if one such complementary therapy,

2004a; Friese 2008). Furthermore, daytime fatigue caused progressive muscle relaxation (PMR), could improve sleep

by sleep disruption is a contributing factor to post-cardiac quality. PMR was pioneered by Edmund Jacobson and

surgery patients not participating in and benefiting to the uses a method of ‘tense and release’ of the muscle groups

full extent from rehabilitation programmes while in to induce the relaxation response (Payne, 1995). Relaxation

hospital (Richards, 1998). A study by Barnason et al has been described as counteracting stress in a non-phar-

(2008) reported that patients who are fatigued after macological, non-invasive way by producing a state of

cardiac surgery experience significantly poorer ratings for physiological and psychological rest (McCabe, 2001). The

psychosocial scores such as mood, emotional wellbeing process of PMR involves tensing one specific muscle

and social function compared with those who are not group for a short period of time (less than 10 seconds),

with conscious thought focusing only on the tense feeling

of that muscle group. After the period of tension, the mus-

cle group is relaxed with the feeling of relaxation greatly

Abstract enhanced by the immediate contrast between the two

Research has consistently described that patients after cardiac states of tension and relaxation. The procedure then moves

surgery experience disturbed sleep yet there has been limited on to tension followed by relaxation of the next muscle

investigation into methods to improve this experience. Complementary group. A popular sequence moves from the lower body to

therapies may be a method of addressing this issue. the upper starting at the feet.

Aim: To determine if using progressive muscle relaxation improves Contemporary health-care practices have driven a reduc-

self-rated sleep quality for patients following cardiac surgery. tion in hospital stay for all types of surgery (Farrell, 2005),

Methods and Results: Thirty-five participants’ quantitative data on however the complicated nature of cardiac surgery still

sleep quality were obtained via questionnaire during their first post-

necessitates an extended length of stay in hospital. These

operative week after cardiac surgery. Qualitative data were obtained

practices are reflected in Australian length-of-stay data with

through written responses to open-ended questions. No significant

the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2005)

differences in sleep quality scores were found between pre and post-

intervention of progressive muscle relaxation using the Wilcoxon reporting the average length of stay for the most common

Signed Ranks Test. However, the qualitative analysis discovered the cardiac surgery, coronary artery bypass grafting, of seven

intervention aided some participants in initiating their sleep by days. Although this article reports on a study conducted in

diversion of thought, inducing relaxation or alleviating pain and Australia, it is likely that these length of hospital stay figures

anxiety. are somewhat similar to other western countries that pro-

Conclusions: Qualitative findings suggest that progressive muscle vide a cardiac surgery service, and therefore relevant to

relaxation may help patients who have undergone cardiac surgery nursing practice in the United Kingdom.

initiate their sleep.

Background

Key words Research in the use of PMR after cardiac surgery is limited

w Complementary therapies w Sleep w Cardiac surgery with only one previous study investigating the topic. This

w Recovery w Mixed methods study was a small study with 25 participants using a randomized

Submitted for peer review 5 November 2009. Accepted for publication 22 controlled trial that did not achieve significant results for

February 2010. Conflict of interest: None their measurements of pain, anxiety, calm, rest and relaxa-

tion (Hattan et al, 2002).

142 British Journal of Cardiac Nursing March 2010 Vol 5 No 3

© MA Healthcare Ltd. Downloaded from magonlinelibrary.com by 129.127.145.240 on November 2, 2017.

Use for licensed purposes only. No other uses without permission. All rights reserved.

Research and Development

However, a number of studies present evidence to sup- data from five of the participants were incomplete and as

port the conduct of this study. First, patients who have such, 35 participants’ data were used for analysis.

undergone cardiac surgery experience their most dis-

turbed sleep during the first post-operative week (Redecker Instrument

et al, 2004a). Second, disturbed sleep in cardiac surgical To test the hypothesis, an instrument to measure sleep

patients has been correlated with poor ratings for psycho- quality was required. Yi et al (2006) describe six factors

logical and emotional wellbeing (Edéll-Gustafsson et al, that comprise sleep quality in their instrument, the Sleep

1997; Edéll-Gustafsson and Hetta, 1999; Edéll-Gustafsson Quality Scale. A single scale was used in this study to

et al, 1999; Hunt et al, 2000; Edéll-Gustafsson, 2002; measure each of the factors of the sleep quality scale as this

Redecker et al, 2004b). Finally, PMR has demonstrated approach enabled the written responses to be limited to

effectiveness in improving anxiety and depression scores one page per day to reduce participant fatigue and maxim-

and quality of life in a variety of patients in the clinical ise the participants’ response rate (Polit and Beck, 2010).

setting (Collins and Rice, 1997; Cheung et al, 2001; Yoo et Scales are widely used as a measure of sleep quality and

al, 2005). daytime functioning and are easy to understand and com-

plete (Zisapel and Nir, 2003).

Aims Participants were asked to mark a numerical value on a

The aims of this study were first, to determine if patients’ scale from 1 to 10 in response to a question about their

responses for self-rated sleep quality are improved after

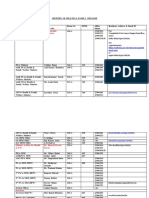

using PMR in the early post-operative period, and second, Table 1.

to obtain qualitative information regarding the partici-

Participant involvement in study

pants’ experiences of using PMR and of their sleep whilein

hospital. The following hypothesis was tested. Day Participant involvement

Hypothesis: Use of progressive muscle relaxation during Day prior to Consent to participate in the research

the first post-operative week after cardiac surgery will result surgery

in a positive change in self-rated sleep quality scores.

Day of surgery Participant in cardiothoracic ICU. Nothing

required of participant

Methods

Study design Day one after Participant in cardiothoracic ICU. Nothing

A mixed methods design was employed. Participants were surgery required of participant

administered a questionnaire which was completed daily Day two after Participant transferred to cardiology ward

from the third to the seventh post-operative day. The quan- surgery during the day. Nothing required of participant

titative component of the study gathered data from partici- Day three Participant provided with questionnaire,

pants to determine self-rated sleep quality through daily after surgery recording and CD player. Participants to fill in

completion of a number of scales. A within-group design the first page of questionnaire, rating their

was used with data collected from the same group of par- previous night’s sleep quality on scales

ticipants both before and after implementing PMR (Polit provided

and Beck, 2010). The PMR intervention was administered Day four after Participants to fill in the second page of the

by audio-recorded instructions played on a personal port- surgery questionnaire, rating their previous night’s

able CD player with earphones. Table 1 outlines the times at sleep on scales provided. Participants to

which the intervention was administered and data collected. perform progressive muscle relaxation prior to

The qualitative component explored the participants’ going to sleep

experiences of sleep and their use of PMR through written

Day five after Participants to fill in the third page of the

responses to open-ended questions at the conclusion of

surgery questionnaire, rating their previous night’s

the study on the seventh day after surgery (Denzin and sleep on scales provided. The participants to

Lincoln, 2008). All of the data were collected from May perform progressive muscle relaxation prior to

2008 to August 2008 in one 430-bed private acute care going to sleep

hospital in a city in Australia.

Day six after Participants to fill in the fourth page of the

surgery questionnaire rating their previous night’s

Participants

sleep on scales provided. The participants to

A convenience sampling method (Polit and Beck, 2010)

perform progressive muscle relaxation prior to

was employed for this study. Participants were required to

going to sleep

be over 18 years of age, and able to speak and understand

English. A total of 67 patients gave their consent to par- Day seven Participants to complete the questionnaire,

ticipate in the study over a two and a half month period. after surgery rating their previous night’s sleep using the

Forty of the participants who provided consent fulfilled scales provided and answering the ‘experience

the requirement of admittance to the cardiology ward of sleep’ questionnaire. Once completed, the

participants to return the questionnaire in an

from the intensive care unit (ICU) on the second post-

envelope to their registered nurse

operative day, and were eligible to enter the study. However,

British Journal of Cardiac Nursing March 2010 Vol 5 No 3 143

© MA Healthcare Ltd. Downloaded from magonlinelibrary.com by 129.127.145.240 on November 2, 2017.

Use for licensed purposes only. No other uses without permission. All rights reserved.

Research and Development

participants did not identify his/her gender. For the

How hard was it for you to fall asleep last night?

majority of participants it was their first experience of

cardiac surgery (88.6%, n=31).

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Descriptive statistics

Easy Hard The majority of participants perceived PMR as being easy

to complete with 60% of the total participants rating PMR

Figure 1. Scale used to measure participants’ difficulty in falling asleep as 3 or less on a scale with 1 being easy and 10 being hard.

Only 23% (n=8) of participants involved in the study had

sleep quality. At each end of the scale was an explanation previously used relaxation techniques.

of the range of experience being measured (an example for

sleep initiation is given in Figure 1). Hypothesis testing

The results from the analysis using the Wilcoxon Signed

Ethical considerations Rank Test for the six aspects of sleep quality measured are

This study was conducted with approval from the relevant presented in Table 2. Overall, the analysis of the six sleep

hospital and university human research ethics committees. quality factors using the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test did

Participation in the research was voluntary and did not not reach statistical significance (P<0.05). Therefore the

impact on the patient’s care as the research studied the hypothesis that PMR will improve self-rated sleep quality

effects of PMR in addition to current standard nursing care of patients during their first week after cardiac surgery was

practices at the study hospital. None of the researchers held not supported.

a clinical role in the department where participants were

recruited or data collected. Participants provided written Thematic analysis

informed consent for participation in the study (National There were three major themes identified from the quali-

Health and Medical Research Council, 2007). tative data: ‘effects of the relaxation process’, ‘interruptions

to the relaxation process’, and ‘suggestions for change to

Data analysis the relaxation process’.

Quantitative data analysis

Pre and post-intervention analyses of scores for each of the Effects of the relaxation process

six aspects of sleep quality were used to test the hypothesis There were varying responses from participants as to the

that PMR will improve sleep quality. All data were numeri- effects of PMR in the post-operative period. Improved

cally coded and entered into the SPSS computer software sleep resulting from the relaxed feeling produced by PMR

package and screened for missing values by variable and by was described by 20% (n=7) of participants.

case. This process identified that data from day seven sleep

scores were missing from 37% (n=13) of questionnaires. I felt more relaxed so I felt I went off to sleep easier and

Day seven sleep scores were excluded from analysis so that stayed asleep for most of the night (Participant 2).

sleep scores from day three and day four post surgery com-

prised the pre-intervention data (before PMR intervention) Seven participants (20%) described PMR as diverting

and sleep scores from day five and six post surgery com- their thoughts to enable initiation of sleep. Participants

prised post-intervention data. The data did not meet the expressed this experience in several ways, such as:

requirements of the assumptions underlying the use of

parametric tests and hence the non-parametric alternative, The effect of the process is to divorce the mind from

Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test, was used (Pallant, 2005). external stimulation (movement, sound, light)

(Participant 33).

Qualitative data analysis

The qualitative data analysis process used to identify Similar to the thought diversion ideas were comments

themes in the data was based on a thematic analysis from participants that the relaxation prepared their mind

framework provided by Braun and Clark (2006). The steps for sleep. A smaller number of participants (n=2, 6%)

taken to identify the themes include familiarizing with the described their experiences in this way.

data, identifying interesting features, searching for themes

and naming themes. Preparation (of) one’s mind is important for this

type of surgery and muscle relaxation can be helpful.

Results (Participant 29).

Demographic data

The participants ranged in age from 48 to 87 years with a The final explanation offered by two participants (6%)

mean age of 67.2 years (SD=9.589) and a median age of for the improved sleep experienced after using PMR was

66.5 years. The majority of participants were male com- that it helped to relieve anxiety and pain.

prising 66% (n=23) of the study sample, while female

participants were 31% (n=11) of the cohort. One of the (It) helped me to sleep when in pain (Participant 30).

144 British Journal of Cardiac Nursing March 2010 Vol 5 No 3

© MA Healthcare Ltd. Downloaded from magonlinelibrary.com by 129.127.145.240 on November 2, 2017.

Use for licensed purposes only. No other uses without permission. All rights reserved.

Research and Development

Interruptions to the relaxation process Suggestions for change to the relaxation process

More than half of the participants reported an interrup- Participants offered suggestions as to how PMR could be

tion that prohibited or distracted them from using PMR. more effective, be modified for use in different situations

The participants felt that these interruptions detracted and also what environment would best suit its use. Some

from the advantages of relaxation during the stressful time participants thought that PMR worked more effectively

after cardiac surgery. The most prevalent of these inter- with increased use, therefore they suggested that patients

ruptions was noise in the environment (n=8, 23%): undergoing similar heart surgery should use the relaxa-

tion intervention more often, with a participant also sug-

The continual noise—especially the drug door slams gesting its use before surgery.

all the time. Very annoying and hard to concentrate.

(Participant 19). The system probably needs a longer time frame. (That

is) some practice prior to surgery (Participant 33).

Another external factor that interrupted the relaxation

process was battery failure of the CD player which was Other comments suggested that PMR improved with

reported by 9% (n=3) of patients. This outcome was a dis- repetitive use.

appointing revelation as the comments demonstrated how

disadvantaged participants felt by the equipment failure. The muscle relaxation would improve the more it is

used. But it did help on three or four occasions for

(The) effect was not the same and quality of sleep was me (Participant 14).

way down on nights (compared with) when I used

the CD (Participant 1). The suggestion by two participants (6%) that PMR

would be more effective in a ‘home’ environment is not

As well as external factors interrupting the relaxation surprising due to the 23% of respondents who said that the

process, the participants reported internal factors includ- relaxation was interrupted by noise in the environment:

ing pain (n=7, 20%) and coughing (n=2, 6%) that inhibit-

ed the relaxation process. Comments from a participant Excellent tape but bouts of coughing interrupt, also

suggest that relaxation would be easier to complete and be nurses pop in and out doing necessary tests. Good to

more effective if pain was controlled. learn when (I’m) home without interruptions.

(Participant 21).

I fell asleep several times while listening to (the) CD

except when (the) pain was really acute (Participant Discussion

24). The results of this study do not support the introduction

of PMR to improve sleep quality in the early post-opera-

Table 2.

Results of Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test for aspects of sleep quality

Sleep factor Z score P value Mean Std deviation

Sleep initiation -1.88 0.06 (not significant) Pre 6.71 Pre 3.50

1=Higher sleep quality Post 5.66 Post 2.72

10=Lower sleep quality

Daytime tiredness -1.65 0.96 (not significant) Pre 7.12 Pre 2.97

1=Lower sleep quality Post 7.94 Post 2.31

10=Higher sleep quality

Sleep satisfaction -0.16 0.88 (not significant) Pre 8.23 Pre 3.87

1=Lower sleep quality Post 8.20 Post 2.86

10=Higher sleep Quality

Sleep restoration -1.17 0.25 (not significant) Pre 7.14 Pre 3.25

1=Lower sleep quality Post 8.00 Post 3.04

10=Higher sleep quality

Waking after sleep -1.26 0.21 (not significant) Pre 4.99 Pre 2.92

1=Higher sleep quality Post 4.23 Post 2.16

10=Lower sleep quality

Sleep maintenance -0.60 0.55 (not significant) Pre 6.90 Pre 3.57

1=Higher sleep quality Post 6.47 Post 3.12

10=Lower sleep quality

British Journal of Cardiac Nursing March 2010 Vol 5 No 3 145

© MA Healthcare Ltd. Downloaded from magonlinelibrary.com by 129.127.145.240 on November 2, 2017.

Use for licensed purposes only. No other uses without permission. All rights reserved.

Research and Development

tive period for patients after cardiac surgery. However, and Hattan et al (2002)—used similar techniques in apply-

conducting this research has offered insight into a group ing PMR using a recording to guide participants through

of cardiac surgical patients’ experiences of the effects of the relaxation, none raised the issue of difficulties or inter-

PMR, their perceived ease or difficulty in using the tech- ruptions experienced by participants. This is an important

nique as it was applied in this study with an audio record- finding as it provides guidance to address these issues for

ing guiding their sessions and their perceived inhibiting future studies using PMR in the clinical setting.

factors to the relaxation process. Finally the research also Results from the quantitative component of this research

elicited suggestions for improvements to the use of this found that 60% (n=21) of the participants found the tech-

particular complementary therapy in the clinical setting to nique easy to complete. Therefore to make it easier for

consider in further studies. patients to use PMR and benefit from the state of relaxation

Although improved self-rated sleep quality scores for it can induce, strategies to address the interruptions to the

patients after using PMR did not occur at a statistically relaxation process that were identified by this research

significant level some participants described various posi- could be implemented.

tive effects of the relaxation process, which suggest that For example, efforts should be made to introduce the

PMR warrants further study to determine its effectiveness intervention at a time when patients’ pain and other

in improving sleep for this population of patients. The symptoms are under control, possibly by using the tech-

positive effects of PMR identified by some participants in nique after pain medication is administered. As this study

this study included aiding initiation of sleep by bringing investigated PMR as a complementary nursing therapy,

about a sense of relaxation, diversion from negative when implemented into practice the nurse would have the

thoughts resulting in calm thought processes, providing a ability to plan and integrate the relaxation into the holistic

method for relaxing a specific body part thus facilitating care of the patient at a time selected by the patient, as

comfort or simply making it easier to ‘switch off ’ and pre- opposed to the participant using the technique at a pre-

pare the mind for sleep. scribed time as in the case of this research.

The theme ‘suggestions for change to the relaxation A significant interruption described by participants was

process’, provides insight into possible methods of improv- noise, which has been shown to negatively influence sleep

ing the relaxation technique. One suggestion was that in acute care settings (Missildine, 2008). This interruption

PMR would work better for participants if they were able is difficult to address as the technique is aimed at improv-

to use the relaxation technique more often. The literature ing sleep for cardiac surgical patients when it is most dis-

on PMR supports an early introduction of the relaxation turbed in the first post-operative week. Unfortunately this

technique. For example, Yoo et al (2005), who investigated means patients will be in hospital in a busy surgical ward

PMR with patients receiving chemotherapy for breast can- with noise from other patients, staff and equipment, all

cer, found that PMR had more of an effect during the fifth contributing to a disturbing environment.

and sixth sessions while Haase et al (2005), when research-

ing patients who have had colorectal resections, imple- Study limitations

mented the relaxation technique before surgery continu- Due to the limited data collection time and a large propor-

ing through to the post-surgical period. Therefore, more tion of consented participants not transferring from the

practice using the relaxation technique may be required ICU to the cardiology ward on their second day after sur-

before effective use is achieved. gery (as required in the inclusion criteria for the study)

To address this issue in the future, the technique can only a relatively small group of participants recruited was

either be introduced before surgery, so that patients can eligible to enter the study. A replication study at several

become more comfortable with PMR, or patients could be different hospital sites where earlier transfer to the cardiac

allowed to use PMR on more than one occasion through- surgical ward is more common would result in a larger

out the day. Introducing the technique before surgery may sample size due to an increased proportion of the con-

make patients more comfortable using the technique and sented participants being allowed to enter the study on

therefore they may experience fewer interruptions to the their second day after surgery.

relaxation process. Only 22.9% of participants had used A longer data collection period and thus larger sample

relaxation techniques before this research, which further size would also allow for a more rigorous methodology to

strengthens the argument for earlier introduction and use be used, such as a randomized controlled group design.

of the technique to allow patients more time and practice This type of research design would be the most effective in

to become familiar with it. determining a cause-and-effect relationship between the

Previous research into the use of PMR has not described use of PMR and sleep quality of patients who have under-

the interruptions to the relaxation process expressed by gone cardiac surgery (Polit and Beck, 2010). Using such a

participants in this study, although these interruptions design it is possible that PMR could be used by partici-

may appear to be self-evident. Examples of interruptions pants for a longer period of time than in the present study.

reported included equipment failure of the CD player, The experimental group could start using PMR on their

noise from the surrounding environment as well as pain second day after surgery with data collected until discharge

and other associated symptoms. While previous stud- or possibly for a period of time after discharge. This

ies—for example Haase et al (2005), Cheung et al (2001) approach would considerably strengthen further study of

146 British Journal of Cardiac Nursing March 2010 Vol 5 No 3

© MA Healthcare Ltd. Downloaded from magonlinelibrary.com by 129.127.145.240 on November 2, 2017.

Use for licensed purposes only. No other uses without permission. All rights reserved.

Research and Development

this topic as the literature suggests that PMR is more effec-

tive the more it is used (Haase et al, 2005; Yoo et al, 2005).

The need to keep the data collection tool as simple as

Key Points

w Some patients reported that progressive muscle relaxation (PMR)

possible in this study to avoid patient fatigue made it

facilitated initiation of their sleep through diversion of negative

impractical to use an entire extensive data collection tool,

thoughts to a calm thought process, inducing relaxation or alleviating

such as the Sleep Quality Scale devised by Yi et al (2006).

stress or pain

Nevertheless, the use of a previously tested, reliable instru-

ment such as the Sleep Quality Scale would improve the w Patients also reported that they experienced interruptions to using

validity of the data collected and enable comparison with PMR in hospital which detracted from the benefits

other studies using the same instrument. A different

w Relaxation interventions need to be implemented into the nursing

approach would facilitate the use of such a scale later in

care plan at a time when pain is under control and comfort needs

the post-operative period, after participants have had the

have been addressed

opportunity to use PMR on a number of occasions.

w Further research is required to substantiate qualitative evidence that

Conclusions progressive muscle relaxation could potentially improve sleep quality

This study aimed to determine if patients who used PMR

in their first week after cardiac surgery demonstrated an

improvement in self-rated sleep quality. The results of the and polysomnographic study. J Adv Nurs 37: 414–22

quantitative component of the study did not demonstrate Edéll-Gustafsson U, Hetta J (1999) Anxiety, depression and sleep in

an improvement in sleep quality scores after using PMR. male patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Scand J

Caring Sci 13(2): 137–43

However, the qualitative results suggested that PMR Edéll-Gustafsson U, Hetta J, Aren C, Hamrin E (1997) Measurement of

improved some participants’ abilities to initiate sleep sleep and quality of life before and after coronary artery bypass graft-

through a variety of methods including diverting thoughts ing: A pilot study. Int J Nurs Pract 3: 239–46

Edéll-Gustafsson U, Hetta J, Aren C (1999) Sleep and quality of life

to a calm process, inducing relaxation or alleviating pain assessment in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J

and stress. Adv Nurs 29: 1213–20

Strategies to improve the use of PMR with patients in Farrell M (2005) Smeltzer & Bare’s Textbook of Medical-Surgical Nursing.

Lippincott, Philadelphia, PA.

the hospital setting were identified. These strategies, which Friese R (2008) Sleep and critical illness and injury: A review of theory,

should be taken into consideration in future studies, current practice and future directions. Crit Care Med 36: 697–705

include decreasing interruptions and implementing the Haase O, Schwenk W, Hermann C, Müller J (2005) Guided imagery and

relaxation in conventional colorectal resections: A randomized, con-

relaxation into the holistic nursing care plan at a time trolled, partially blinded trial. Dis Colon Rectum 48: 1955–63

when pain and comfort needs are addressed. Hattan J, King L, Griffiths P (2002). The impact of foot massage and

This research has also identified that future study into guided relaxation following cardiac surgery: A randomized control-

led trial. J Adv Nurs 37: 199–207

this topic should use an extended data collection period to Hunt J, Hendrata M, Myles P (2000) Quality of life 12 months after cor-

increase the sample size and thus allow for a more rigor- onary artery bypass graft surgery. Heart Lung 29(6): 401–11

ous study design. McCabe P (2001) Complementary Therapies in Nursing and Midwifery:

From Vision to Practice. Ausmed Publications, Victoria, Australia.

Missildine K (2008) Sleep and the sleep environment of older adults in

Acknowledgements acute care settings. J Gerontol Nurs 34(6): 15–21

This study used funding from the Australian Catholic University Faculty National Health and Medical Research Council (2007) National

Research Student Support Scheme. A postgraduate scholarship from the Statement on Ethical Conduct in human research. Australian

Queensland Nursing Council was accepted by Aaron Conway to fund the Government, Canberra, ACT.

Bachelor of Nursing (Honours) degree associated with this study. Pallant J (2005) SPSS Survival Manual: A step by step Guide to Data

Analysis Using SPSS for Windows (Version 15). 2nd edn. Allen &

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2005) Australian hospital Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW.

statistics 2004–2005: Separations, same day separation, patient day, Payne R (1995) Relaxation Techniques: A Practical Handbook for the

average length of stay and cost statistics for all AR-DRGs version 5.1, Health Professional. Churchill Livingstone, Lansing, MI

public hospitals Australia 2004-2005. http://www.aihw.gov.au/publi- Polit D, Beck C (2010) Essentials of Nursing Research: Appraising

cations/hse/ahs04-05/ (accessed 22 February 2010) Evidence for Nursing Practice. 7th edn. Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott,

Barnason S, Zimmerman L, Nieveen J et al (2008) Relationships Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

between fatigue and early postoperative recovery outcomes over time Redeker N, Ruggiero J, Hedges C (2004a) Patterns and predictors of

in elderly patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. sleep disturbance after cardiac surgery. Res Nurs Health 27: 217–24

Heart Lung 37(4): 245–56 Redeker N, Ruggiero J, Hedges C (2004b) Sleep is related to physical

Braun V, Clark V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. function and emotional well-being. Nurs Res 53: 154–62

Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77-101 Richards K (1998) Effect of a back massage and relaxation intervention

Cheung Y, Molassiotis A, Chang A (2001) A pilot study on the effect of on sleep in critically ill patients. Am J Crit Care 7: 288–99

progressive muscle relaxation training of patients after stoma surgery. Tabachnick B, Fidell L (2001) Using Multivariate Statistics. 4th edn.

Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 10(2): 107–14 Allyn and Bacon, Boston MA.

Collins J, Rice V (1997) Effects of relaxation in phase II cardiac rehabilita- Yi H, Shin K, Shin C (2006) Development of sleep quality scale. J Sleep

tion: Replication and extension. Issues in Cardiovascular Care, 26(1): Res 15: 309–16

31–44 Yoo H, Ahn S, Kim S, Kim W, Han O (2005) Efficacy of progressive

Crisp J, Taylor C (2001) Potter & Perry’s Fundamentals of Nursing. muscle relaxation training and guided imagery in reducing chemo-

Elsevier, NSW, Australia therapy side effects in patients with breast cancer and in improving

Denzin N, Lincoln S (2008) Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative their quality of life. Supportive Care in Cancer 13: 826–33

Materials. 3rd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA Zisapel N, Nir T (2003) Determination for the minimally clinically sig-

Edéll-Gustafsson U (2002) Insufficient sleep, cognitive anxiety and nificant difference on a patient visual analog sleep quality scale. J

health transition in men with coronary artery disease: A self-report Sleep Res 12: 291–8

British Journal of Cardiac Nursing March 2010 Vol 5 No 3 147

© MA Healthcare Ltd. Downloaded from magonlinelibrary.com by 129.127.145.240 on November 2, 2017.

Use for licensed purposes only. No other uses without permission. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Ekg FastlaneDocument10 pagesEkg FastlaneAida UzunovicNo ratings yet

- Back Massage Intervention For Improving Health and Sleep Quality Among Intensive Care Unit PatientsDocument7 pagesBack Massage Intervention For Improving Health and Sleep Quality Among Intensive Care Unit PatientsيوكيNo ratings yet

- R Atients in Critical Care: Mmediate Effects of A Five-Inute Foot Massage OnDocument6 pagesR Atients in Critical Care: Mmediate Effects of A Five-Inute Foot Massage OnEstirahayuNo ratings yet

- Relaksasi Benson Untuk Durasi Tidur Pasien Penyakit Jantung KoronerDocument6 pagesRelaksasi Benson Untuk Durasi Tidur Pasien Penyakit Jantung Koronerricca andrianiNo ratings yet

- IJSHR008Document6 pagesIJSHR008chetankumarbhumireddyNo ratings yet

- Artikel 2 - Music - Movement - Theraphy - Stroke - IskemikDocument10 pagesArtikel 2 - Music - Movement - Theraphy - Stroke - Iskemikselamat parminNo ratings yet

- Comparing The Effects of Music and Exercise With Music For Older Adults With InsomniaDocument7 pagesComparing The Effects of Music and Exercise With Music For Older Adults With InsomniaConsuelo VelandiaNo ratings yet

- 1-s2.0-S0965229921001254-main-PMR CABGDocument7 pages1-s2.0-S0965229921001254-main-PMR CABGMarina UlfaNo ratings yet

- Effects of A Relaxation Breathing Exercise On Fatigue in Haemopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation PatientsDocument5 pagesEffects of A Relaxation Breathing Exercise On Fatigue in Haemopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation PatientsRobi Khoerul AkbarNo ratings yet

- 1655 2366 1 PBDocument11 pages1655 2366 1 PBAgatha NindaNo ratings yet

- Article 1 401 en PDFDocument6 pagesArticle 1 401 en PDFsulkifliNo ratings yet

- EJHC Volume 11 Issue 4 Pages 566-581Document16 pagesEJHC Volume 11 Issue 4 Pages 566-581احمد العايديNo ratings yet

- Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews: Cindy Stroemel-Scheder, Bernd Kundermann, Stefan Lautenbacher TDocument18 pagesNeuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews: Cindy Stroemel-Scheder, Bernd Kundermann, Stefan Lautenbacher TAMBAR SOFIA SOTONo ratings yet

- Integrating A Portable Biofeedback Device Into Clinical Practice For Patients With Anxiety Disorders: Results of A Pilot StudyDocument7 pagesIntegrating A Portable Biofeedback Device Into Clinical Practice For Patients With Anxiety Disorders: Results of A Pilot StudyLuis A Gil PantojaNo ratings yet

- Frazzitta Et AlDocument8 pagesFrazzitta Et Alalex ormazabalNo ratings yet

- Exercise Training Augments Brain Function and Reduces Pain Perception in Adults With Chronic PainDocument9 pagesExercise Training Augments Brain Function and Reduces Pain Perception in Adults With Chronic PainfisioterapeutalucasfontouraNo ratings yet

- Chest Physiotherapy After Surgical Treatment of Adolescent Idiopathic ScoliosisDocument2 pagesChest Physiotherapy After Surgical Treatment of Adolescent Idiopathic ScoliosisDaniel GuevaraNo ratings yet

- PTJ 1275Document12 pagesPTJ 1275Taynah LopesNo ratings yet

- Short-And Long-Term Effects of Exercise On Neck Muscle Function in Cervical Radiculopathy: A Randomized Clinical TrialDocument9 pagesShort-And Long-Term Effects of Exercise On Neck Muscle Function in Cervical Radiculopathy: A Randomized Clinical Trialvidisanjaya21No ratings yet

- Unal 2016Document21 pagesUnal 2016Deni MalikNo ratings yet

- Case Report: Manual Therapy and Exercise To Improve Outcomes in Patients With Muscle Tension Dysphonia: A Case SeriesDocument12 pagesCase Report: Manual Therapy and Exercise To Improve Outcomes in Patients With Muscle Tension Dysphonia: A Case SeriesNicolas DiaconoNo ratings yet

- By Past FatigueDocument6 pagesBy Past FatigueefielyarizaNo ratings yet

- 2017 PNF and Manual Therapy Treatment Results of Cervical OADocument7 pages2017 PNF and Manual Therapy Treatment Results of Cervical OApainfree888100% (1)

- The Effects of Eye Masks and Earplugs On The Sleep Quality and Anxiety of Hospitalized Patientsa Randomised Controlled TDocument9 pagesThe Effects of Eye Masks and Earplugs On The Sleep Quality and Anxiety of Hospitalized Patientsa Randomised Controlled TjayaNo ratings yet

- Sleep Restriction Therapy PDFDocument37 pagesSleep Restriction Therapy PDFFenyNo ratings yet

- Exercise and OpioidsDocument10 pagesExercise and OpioidsCatalina Vallejos PaillaoNo ratings yet

- Meditación e InsomnioDocument12 pagesMeditación e InsomniodanielmarkusaNo ratings yet

- Iles, R Et Al. Telephone Coaching Can Increase Activity Levels For People With Non-Chronic Low Back PainDocument8 pagesIles, R Et Al. Telephone Coaching Can Increase Activity Levels For People With Non-Chronic Low Back PainDulce María AlanisNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0965229923000833 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S0965229923000833 MaintheophileflorentinNo ratings yet

- 2408 2413Document6 pages2408 2413Anandhu GNo ratings yet

- 43 Beebe2013Document7 pages43 Beebe2013Sergio Machado NeurocientistaNo ratings yet

- IndexDocument9 pagesIndexmateh ur rehmanNo ratings yet

- Controlled Study of Neuroprosthetic Functional Electrical Stimulation in Sub-Acute Post-Stroke RehabilitationDocument5 pagesControlled Study of Neuroprosthetic Functional Electrical Stimulation in Sub-Acute Post-Stroke RehabilitationAiry MercadoNo ratings yet

- Brain Sciences: Exercise Strengthens Central Nervous System Modulation of Pain in FibromyalgiaDocument13 pagesBrain Sciences: Exercise Strengthens Central Nervous System Modulation of Pain in FibromyalgiaJavier Alejandro Rodriguez MelgozaNo ratings yet

- Aceptacion Compromiso FibromialgiaDocument14 pagesAceptacion Compromiso FibromialgiapsicologorubiNo ratings yet

- Depauw 2014Document9 pagesDepauw 2014CarolinaNo ratings yet

- 35 Aml ELmetwaly For PublishingDocument13 pages35 Aml ELmetwaly For PublishingDinda Resty L DNo ratings yet

- 2015 - Linder - Improving Quality of Life and Depression After StrokeDocument10 pages2015 - Linder - Improving Quality of Life and Depression After StrokeWarsi MaryatiNo ratings yet

- Moore 2013Document9 pagesMoore 2013Andrés MardonesNo ratings yet

- PNF Ombro 04Document10 pagesPNF Ombro 04Isaias AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal CCFTDocument8 pagesJurnal CCFTfi.afifah NurNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Cranio-Cervical Flexion Training Versus Cervical Proprioception Training in Pt's With Chronic Neck PainDocument8 pagesComparison of Cranio-Cervical Flexion Training Versus Cervical Proprioception Training in Pt's With Chronic Neck Painbcvaughn019No ratings yet

- Nascis 2Document8 pagesNascis 2Amaiiranii GarciiaNo ratings yet

- Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation PNF ItsDocument10 pagesProprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation PNF ItsKhaled RekabNo ratings yet

- Deambulacion Vs Reposo en CPPDocument10 pagesDeambulacion Vs Reposo en CPPNoé Alejandro SánchezNo ratings yet

- Evidence Based TKR RehabDocument24 pagesEvidence Based TKR RehabVardhman Jain IINo ratings yet

- Demi Rel 2019Document7 pagesDemi Rel 2019Luis Miguel Cardona VelezNo ratings yet

- Chronotherapeutics Light and Wake Therapy in Affective DisordersDocument6 pagesChronotherapeutics Light and Wake Therapy in Affective DisordersAnonymous zxTFUoqzklNo ratings yet

- PNFpresentationDocument32 pagesPNFpresentationNarkeesh ArumugamNo ratings yet

- Tzenalis Study ProtocolDocument9 pagesTzenalis Study ProtocolCristoper PanjaitanNo ratings yet

- 1385 FullDocument10 pages1385 FullSetiaty PandiaNo ratings yet

- PnfpresentationDocument32 pagesPnfpresentationCherry RipeNo ratings yet

- Manual Therapy: Clare Louise Clarke, Cormac Gerard Ryan, Denis J. MartinDocument6 pagesManual Therapy: Clare Louise Clarke, Cormac Gerard Ryan, Denis J. MartinRensoBerlangaNo ratings yet

- To Compare The Effect of Core Stability Exercises and Muscle Energy Techniques On Low Back Pain PatientsDocument7 pagesTo Compare The Effect of Core Stability Exercises and Muscle Energy Techniques On Low Back Pain PatientsDr Ahmed NabilNo ratings yet

- Does The Addition of Visceral Manipulation Alter Outcomes For Patients With Low Back Pain? A Randomized Placebo Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesDoes The Addition of Visceral Manipulation Alter Outcomes For Patients With Low Back Pain? A Randomized Placebo Controlled TrialQuiroprácticaParaTodosNo ratings yet

- Does Meditation Reduce Pain Through A Unique Neural Mechanism?Document3 pagesDoes Meditation Reduce Pain Through A Unique Neural Mechanism?Orlando Vargas CastroNo ratings yet

- Quantifiable Effects of Osteopathic Manipulative Techniques PDFDocument5 pagesQuantifiable Effects of Osteopathic Manipulative Techniques PDFRodrigo MedinaNo ratings yet

- 1472 6882 2 9 PDFDocument8 pages1472 6882 2 9 PDFThiago NunesNo ratings yet

- Delaney 2015Document10 pagesDelaney 2015irnyirnyNo ratings yet

- PDF - Published Version BostDocument7 pagesPDF - Published Version Bostmuratigdi96No ratings yet

- Transsexual Transgendered Guide To Obtaining and Using Transsexual Hormones, Hormone Replacement Therapy HRTDocument52 pagesTranssexual Transgendered Guide To Obtaining and Using Transsexual Hormones, Hormone Replacement Therapy HRTTrinity Rose Transsexual77% (13)

- Eskaton Preferred Vendor Directory Rec042612Document42 pagesEskaton Preferred Vendor Directory Rec042612Karuna Labs IncNo ratings yet

- Supraventricular Tachycardia - Life in The Fast Lane ECG LibraryDocument29 pagesSupraventricular Tachycardia - Life in The Fast Lane ECG LibraryYehuda Agus SantosoNo ratings yet

- Human Factors ChadezDocument242 pagesHuman Factors ChadezChristopher MutyambiziNo ratings yet

- Assisted Suicide Research EssayDocument8 pagesAssisted Suicide Research Essayapi-496713107No ratings yet

- MoHFW Directory - 7Document22 pagesMoHFW Directory - 7nagarjunaNo ratings yet

- J of Cosmetic Dermatology - 2022 - Woolery Lloyd - Review of The Microbiome in Skin Aging and The Effect of A TopicalDocument7 pagesJ of Cosmetic Dermatology - 2022 - Woolery Lloyd - Review of The Microbiome in Skin Aging and The Effect of A TopicalThomas UtomoNo ratings yet

- Model Question Paper SampleDocument8 pagesModel Question Paper SampleMilanSinghBaisNo ratings yet

- OutSource APVVPDocument8 pagesOutSource APVVPNSS S.K.UniversityNo ratings yet

- Performance Appraisal & Hetero Drugs Ltd.Document78 pagesPerformance Appraisal & Hetero Drugs Ltd.Nirmala Rao100% (2)

- SP 1 New GenerationDocument162 pagesSP 1 New Generationzavala74No ratings yet

- A Sociological Study On Retired Government Employs in Karnataka. (Special Reference To Shimoga District)Document6 pagesA Sociological Study On Retired Government Employs in Karnataka. (Special Reference To Shimoga District)inventionjournalsNo ratings yet

- Module 2 Study Guide-2Document3 pagesModule 2 Study Guide-2api-322059527No ratings yet

- Ch05 Presentation CPRDocument28 pagesCh05 Presentation CPRDawn KleinNo ratings yet

- Chordee TypesDocument2 pagesChordee TypesKousik AmancharlaNo ratings yet

- Heart Disease, Ascorbate, Lysine and Linus Pauling by Jeffrey Dach MDDocument33 pagesHeart Disease, Ascorbate, Lysine and Linus Pauling by Jeffrey Dach MDEbook PDF100% (1)

- Peadodontics Mcqs Collection, by RashaDocument43 pagesPeadodontics Mcqs Collection, by RashaShakil Murshed100% (1)

- Form Pengkajian KosonganDocument34 pagesForm Pengkajian KosonganYurike OliviaNo ratings yet

- Agriculture Paper 2 Form 4: NAME ADM CLASS .Document10 pagesAgriculture Paper 2 Form 4: NAME ADM CLASS .Lindsay HalimaniNo ratings yet

- PDF Cognitive Communication Disorders of Dementia Definition Diagnosis and Treatment 3 Ed Edition Kathryn Bayles Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF Cognitive Communication Disorders of Dementia Definition Diagnosis and Treatment 3 Ed Edition Kathryn Bayles Ebook Full Chapteryolanda.schwartz402100% (2)

- Sci Chapter 2 8thDocument18 pagesSci Chapter 2 8thAakash ChatakeNo ratings yet

- Primary and Secondary Survey in TraumaDocument53 pagesPrimary and Secondary Survey in Traumaizwan taufikNo ratings yet

- Collective Trauma Summit 2021 - Laurie - Leitch - The Social Resilience ModelDocument2 pagesCollective Trauma Summit 2021 - Laurie - Leitch - The Social Resilience ModelEmilia LarraondoNo ratings yet

- Quality Control of Metronidazole Tablet Available in Bangladesh.Document11 pagesQuality Control of Metronidazole Tablet Available in Bangladesh.Muhammad Tariqul Islam100% (1)

- Scuffmaster FDS STDocument4 pagesScuffmaster FDS STflooring123No ratings yet

- Time ManagementDocument12 pagesTime ManagementRidhiranjan MarthaNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Introduction To Audiology Today 1st Edition Hall 9780205569236Document36 pagesTest Bank For Introduction To Audiology Today 1st Edition Hall 9780205569236CharlesLarsonsxag100% (24)

- Nurse RoleDocument1 pageNurse RolechoobiNo ratings yet

- Development and In-Vitro Evaluation of Catechin Loaded Ethosomal Gel For Topical DeliveryDocument6 pagesDevelopment and In-Vitro Evaluation of Catechin Loaded Ethosomal Gel For Topical DeliveryRAPPORTS DE PHARMACIENo ratings yet