Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Trommel - Nursing Problems TEN Patients and Stevens Johnson Syndrome in Dutch Burn Centre - 2019

Trommel - Nursing Problems TEN Patients and Stevens Johnson Syndrome in Dutch Burn Centre - 2019

Uploaded by

edwin fernando pestana tirado0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views9 pagesOriginal Title

Trommel_Nursing-problems-TEN-patients-and-Stevens-Johnson-syndrome-in-Dutch-burn-centre_-2019

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views9 pagesTrommel - Nursing Problems TEN Patients and Stevens Johnson Syndrome in Dutch Burn Centre - 2019

Trommel - Nursing Problems TEN Patients and Stevens Johnson Syndrome in Dutch Burn Centre - 2019

Uploaded by

edwin fernando pestana tiradoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 9

auans 45 (2019) 1625-1632

Available online at wru.sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

journal homepage: www.clsevier.com/locate/burns

Nursing problems in patients with toxicepidermal ®™

necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome in a

Dutch burn centre: A 30-year retrospective study

N. Trommel“"", H.W. Hofland””, R.S. van Komen®, J. Dokter“,

M.E. van Baar”

“Bum Centre, Maasstad Hospital, P.0. Box 9100, 3007 AC Rotterdam, The Netherands

® association of Dutch Burn Centres, P.O. Box 1015, 1940 EA Beverwijk, The Netherlands

ARTICLE INFO apsTRAcT

‘ie hstoy Objective: Multiple stadies have been published on tonic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and

‘Accepted 2July 2019 Stevens-Johnsen syndrome (9). Nusingcare isan important partof the treatment of TEN

patients, Unfortunately, limited information on nursing in TEN/SIS patients has been.

Published in the current literature. Nursing research is needed to improve the complex:

nursing care required for these rare patients. Therefore, the objective was to assess nursing

Keywords problems in TEN patients in a burn centre setting over a 30-year period

as Methods: The data fr thi study were gathered retrospectively from nursing records cf allpatents|

ss ‘with TENS)Sadmited to Burn Centre Rotterdam between January 1587 and December 216, Dutch

Nursing problems ‘bur centres were recently accepted as expertise centres for TEN patients. Nursing problems were

Nursing diagnosis Classified using the dassifation of nursing problems of the Dutch Nursing Society.

Results: A total of 69 patients were admitted with SIS/TEN. Fifty-nine patient Mes were

available. The most frequently reported nursing problems (>20% of the patients) were

‘wounds, threatened or disrupted vital functions, dehydration or fuid imbalance, pain,

secretion problems and fever. Furthermore, TEN-specific nursing problems were docu:

‘mented, including oral mucosal lesions and ocular problems. The highest number of

‘concomitant nursing problems occurred during the period between days three and 20 after

‘onset ofthe disease and vatied by nursing problem,

Conclusions: The most frequently reported mursing problems involved physical functions,

‘especially on days three 1020 after onset of the disease. With this knowledge, we can start

nursing interventions eatly in the teatment, address problems at the frst sign and inform

‘patients and their families orrelatives ofthese issues earlyin the disease process. Anext step

to improve nursing care for TEN patients is to acquire knowledge on the optimal

interventions for nursing problems.

(© 2019 Elsevier Ltd and ISBI. All rights reserved

Abbreviations: TEN, Toxic epidermal necrolysis; JS, Stevens-Johnsen syndrome; TBSA, Total Body Surface Area; NANDA, North

‘American Nursing Diagnosis Association; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; OPD, Outpatient department; SCORTEN, SCORe of Toxic Epidermal

Necrolysis,

* Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: TrommelN@maasstadzickenhuis.nl(N. Trommel) HoflandH@maasstadzickenhuis.nl (LW. Hofland),

KomenR@mazsstadziekenhuis.nl (RS. van Komen), DokterJ@maasstadziekenhuis.nl J. Dokter), BaarM@mzasstadzickenhuis.nl

(Qe. van Baar).

btps//doi.org/10 1016) burns 2019.07 008

(0305-4179/6 2019 Elsevier Ld and ISBI, All rights reserved,

1626

auaws 45 (2019) 1625-1633

1. Introduction

‘Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a rare disease with a

frequency of approximately one or twocases per 1,000,000 peo-

ple [1]. The disease starts oneor twodays beforeepidermolysis,

‘with overall malaise, including fever, myalgia and joint pain,

similar to that noted with flu. Then, the epidermal ayer of the

skin loosens and erosions appear. The patient feels sick and

experiences pain [2]. Three different types of the disease exist:

Stevens Johnson syndrome (5)5), SIS/TEN overlap and TEN,

Epidermal detachment of less than 10% of the body surface

area is noted in 5JS, 10-30% of the body surface area exhibits,

epidermal detachment in S)S/TEN, and more than 30% of the

epidermis is detached in TEN [3]. Patients with TEN mostly

develop erosive mucosa lesions with oral, ocular and genital

involvementora combination thereof. in addition, respiratory,

‘urethral and gastrointestinal epithelial mucosa necrolysis can,

occur, Due to the skin problems and similarities to the

treatment for superficial partialthicknese burns, admission

to a bum centre where specific nursing care is available is,

advised [4.5]

‘Multiple studies have described the importance of early

referral of TEN patients to a burn centre. Early transport to a

bur centre within a week of symptom onset increases the

survival rate, Burn centres differ from non-burn centres in the

tweatment and management of TEN patients [2,6]. Strict

procedures are in place for barrier precaution, constructional,

facilities are available for infection control therapy, and the

environmental temperature is regulated; a multi-disciplinary

‘bur care team is available and includes specialized burn care

purses who have been trained to care for such eritically ill

patients with extensive wounds and other problems related to

the disease [7]

‘Multiple studies have been published on TEN and JS. Awide

range of problems has been described, Problems are generally

similar between these disease types and involve epidermal

detachment, wound care, mucosa problems, and ocular and

‘aftermath problems (8). In their narrative review, Lee et al.

showed the wide range of long-term complications and

sequelae that TEN patients experienced regularly. These

long-term complications and sequelae include not only

‘widespread skin and mucous membrane problems but also

psychological problems. In addition, they described problems

related to participation, including difficulty retumning to work.

{or half of the discharged patients and the required modifica

tons tothe jobs of the patients who returned to their work [9]

‘Nursing care is an important part ofthe treatment of TEN

patients. Unfortunately, the literature on nursing in TEN

patients is Limited, and experiences have been shared only in,

some case studies [10-13]. Nursing research is needed to

improve the complex nursing care required for TEN patients,

[Nursing care follows the five phases of the nursing process:

assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evalu

ation. In this article, we focus on the first two phases:

assessment and diagnosis [14,15]

‘The three Dutch burn centres are expertise centres for TEN

disease in the Netherlands. in our opinion, as care providers at

a TEN expertise centre, we are responsible for performing

‘nursing research in TEN patients. A first step isto describe the

process of nursing care in these patients. Therefore, the main

objective ofthis study was to assess nursing problems in TEN,

patients in a burn centre setting. The second objective was to

Jdentify the onset and duration of nursing problems through-

‘out the period of illness.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Study design and participants

‘This retrospective cohort study was conducted in all patients

with a diagnosis of 5S, S)S/TEN overlap and TEN admitted to

the Burn Centre of the Maasstad Hospital, Rotterdam, the

Netherlands, over a 20-year period (between January 1987 and,

December 2016) Initially, the diagnosis was mainly based on

clinical findings. In the last of the three decades, the diagnosis,

was based on clinical findings incombination with histological,

confirmation by biopsy.

2.2. Data collection

Data on patent and treatment characteristice were collected,

including age, sex, comorbidities, length of stay in the burn

centre, SCORe of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (SCORTEN) and

the amount of affected skin (the Total Body Surface Area

(T3SA) at presentation. The SCORTEN score isa prognostic

Scoring system for SJS/TEN that uses seven clinical param-

eters, including age above 40 years, malignancy, tachycardia

above 120 per min, an inital percentage of epidermal

detachment greater than 10%, serum urea greater than

20mmol perlite, serum glucose greater than 14mmol per

live, and bicarbonate below 20mmol per lite, to predict the

probability of hospital morality. Based on these data, the

SCORTEN score was calculated [15], These data were derived

froma database of ll admitted patients in the bur centreand

from patent record (the mmberofdaysoflineeatreferralto

the bum centre andthe TSA maximum amount of denuded

skin only).

Data on nursing problems were gathered from nursing

records. Nursingproblems were classified into the four domains

of human functioning, including the physical, mental heath,

functional and emetional domains, We wsed the classification

of mursing problems ofthe Dutch Nursing Society based on the

North American Nursing Diagnosis Associaton (NANDA) [17]

(oe Fig, 1. This sa widely used system in our country and is

tsed as the classification in the formal description ofthe Dutch

Nursing Society. Both nursing problems and the date of

recording were collected. Nursing problems were identified

by at eas wo researchers (NT and HH

‘Nursing problems were registered from the day of aémis-

sion in Burn Centre Rotterdam onwards Ifpaients ded during

hospitalization, then the data until the date of death were

used, The study was approved by the local board of directors of

the hospital nt. 2016-033)

23. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics was used to summarize the results of the

study. The mean was used to describe continuous variables with,

auans 45 (2019) 1625-1622 1627

Physical Mental

Endangered or dsturbed vital functions Consciousness disorders

(respiration, cieulaton, brain functions) Mood disorders

Fever Memory disorders

Itching Disturbances in thinking and perceiving suspicion,

Wounds delusions, hallucinations)

Pain Personality disorders

Fatigue Disordersin behaviour (agitation, aggression, claim,

Loss of appetite obsession, auto mutilation)

[Nauseous, vomiting Anse, panic

stress

Weiaht gain Addiction

Dehydration, fd imbalance oss

Secretion problems (micturtion,dlarthoea, Mourning

Constipation, excessive perspiration, incontinence) Uncertainty

Faling

‘Sleep-est pattern problems

Core sot

Nursing problems

Functional Social

Lack of sofmanagement Sexuality avorders

Lack of self-retiance ADL Participation problems

Sensory limitations Sodalincompetence

Disturbed mobitty Loneliness

Shortage of knowledge

Inetectve coping

Problems to given meaning

Lack of social networking

Lackof mantle care

Overloaded carer

Fig. 1 ~ Core set patient problems according to the Dutch Nursing Society [17].

“Bold: problems documented in S)S/TEN patients.

‘8 normal distribution, and the median was used for non

normally distributed data. Categorical data were presented as,

frequencies. Subgroup analysis was performed to examine

differences in patient and treatment characteristics between,

patients with and without complete data In addition differences

in aftercare between diagnoses and treatment periods were

tested, For continuous variables, differences were tested with,

Student’ t-test for normally distributed variables) or the Mann

‘Whitney test (for non-normal distributed variables), Categor-

calvariables were tested using Fisher's exact test 2 categories)

the Chi-square test (+2 categories, ie, treatment period)

(Tables 1 and 2). The data were analysed using SPSS 22.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Burn Centre Rotterdam admitted 69 patients with SJS/TEN in

the 30-year study period. For ten patients, no nursing records

were available, and these cases were excluded (ig. 2). To

assess differences between patients with and without nursing

records, we extracted the characteristics of the different

groups, Patients without nursing records were similar to the

included patients in 15 of 16 characteristics (Tables 1 and 2)

However, they were more frequently admitted in the first

decade of the study period, In another 11 cases, the Intensive

Care Unit(ICU) data were lost, butthe available ward data were

used. All incomplete files were from patients admitted in the

first decade of the study (Tables 1 and 2). The highest number

of concomitant nursing problems occurred in the period

between days three and 0 after onset ofthe disease and varied

by nursing problem (Fig. 3).

3.2. Patient and treatment characteristics

Most ofthe patients were diagnosed with TEN, and only a few

patients had SJS. The patients in our study had a mean age of

525 years (range 7-89 years), and 54.2% were female. A large

part of the patients (69.5%) had coexisting morbidities at,

‘admission, such as epilepsy, cancer or HIV. Almost all patients

(69.8%) were intially admitted tothe ICU. A mean of 4.4 days of

illness was noted between disease onset and admission tothe

burn centre, On admission, a mean of 32.6% of the TRSA was

detached. The expansion maximum was 45.2% of the TBSA in,

the most active phase of the disease. In 69.5% ofthe patients,

‘the mucosa was affected. The mean length of stay was

M42 days, The mean SCORTEN score was 30, Half of the

Participants ICU and Ward data Excluded

n=59 ward data cnly patients

5 n=l n=10

‘Age, mean (SD) 2388) 587 G34) 78 452(308)

Gender, n ()

Male 27158) 24 (500) 3073) 2,200)

Female 32 (542) 24 500) 027 8 (00)

Diagnosis, n ()

38 953) 81167) 103) 00)

Overlap 18,05) 14292) 4064) 200)

T!N 32642) 26 542) 6 (45) 8 (00)

co-morbidity, n (2) 41 (685) 33 (68) 3027) ein

Mucosa affected, n (8) 410685) 33 683) 3027) 2200)

Days of lines

‘At admission, mean (SP) 4469) 5508) 2509 4505)

TSA detached

[Atadmission, mean (SD) 326023) 326 (223) 327 @11) 962 012)

Max. TESA detached, mean (SD) 452002) 59613) 225 051) 536 (095)

SCORTEN, mean (SO) 300) soa) 230.3) 30(0)

"THSA™Total Body Surface Area

Missing values: Mucoss (n=12, (Cand ward n=8, Ward only n=2, excluded n=2},TASA at admission (n=6,1C and ward n=1, excluded n=5),

SCORTEN (n=23, {Cand ward n 8, excluded

‘ward only

(CU & ward data versus ward data only)

Participants ICU and) Ward data Excluded

2 ward data only patients

n=48 a n=10

‘Admission yearn 09)

9881999, nan 242) 112009) 101000)

2000-2008 20337) 23479) 00) )

20.2016 23337) 23473) 00) 00)

sepsis, n (3) 31825) 26 542) 5(55) 409)

Patients deceased during hospitalisation, n () 273) 19096) 2073) 5 (600)

Hospital LOS, mean (SD) 132016 143026) 135 60) 237 (066)

cu stay, n (8) 53 (38) 22675) 11100) 10,100)

‘urn ward, n (4) 40580) 266542) 8027) 6 (60)

Aftercare, outpatient department, n Ce)

Yes a 2 4 o

No, deceased 2 9 3 5

No 2 2 ° °

Unknown 9 ° 4 5

Tcl = intensive Care Unit, LOS length of stay

patients (52.2%) developed septicaemia. In total, 73% diedin 3.4. ICU

‘hospital (Fables 1 and 2)

3.3. General nursing problems

‘Analyses of the59 records showed thatonly 16ofthe41 general

patient problems were described in more than 20% of the

patients (Fable 3). Ten well-known nursing problems were not

described at all. The most frequently documented problems,

‘were wounds, problems with vital functions, dehydration and

‘uid imbalance, pain, secretion problems and fever. Purther

more, nursing problems were intermittently reported by

purses, and problems that persisted for a few days were

reported. For example, mucosa loss was only occasionally

described on subsequent days in the nursing report.

IntheICU, themostcommon documented problems wereinthe

physical domain. in addition to wounds (100%), problems in,

vital functions (84.3%) were frequently reported, followed by

dehydration and fuid imbalance (74.5%), pain (70.6%) and fever,

(70.6%). Secretion problems (60.8%) and fatigue (43.1%) were

also documented. In the mental health domain, consciousness

disorders (51.0%) and anxiety or panic (27.5%) were described

The remaining 12 patient problems in this domain were

reported on a limited scale. In the functional domain, sleep:

rest pattem problems (33.3%) were recorded. A lack of self

reliance (27.5%) and disturbed mobility (25.5%) were also noted

{nthe social part, none of the seven general problems, such as,

participation problems or loneliness, were described (Table 3),

auans 45 (2019) 1625-1622

1629

Patients admitted during

study period n=69

+ sisn=8

+ TENn=40

cohort

cU and ward data

nedB

+ Overlap SiS/TEN n=20

Includedin retrospective

patients

Exelusion:n=10

No nursing records

Ward data Only

ned

Fig. 2 Flowchart describing patient inclusion.

Fig. 2 Nursing problems by onset and duration.

35. Burn ward

n the ward, problems in three domains were also described

In the physical domain, the same problems were reported as

those in the ICU. Moreover, additional problems were

documented, including loss of appetite (694%), itching

(46.9%) and nausea or vomiting (43.8%). In the mental health,

domain, anxiety or panic (28.1%) was documented. The other

“M4 problems, such as mood disorders, stress, lose, uncertainty

ora shortage of knowledge, were not reported regularly. In the

functional domain, problems similar to those in the ICU were

doseribed.as wellas a lack self-management (34.4%). Similar

to the ICU period, no problems in the social part of human,

functioning were noted. Specific problems included oral

‘mucosa and eye problems as wells flaky skin (25.0%) (Table 3)

3.6. Outpatient department (OPD) and psychosocial

aftercare

{A substantial portion of surviving patients (21/33 patients,

63.6%) received aftercare post discharge. Half of the patients,

with S)S or SJS/TEN overlap received aftercare. Most TEN

patients received aftercare (80%), However, the differences

werenotsignificant. The frequency of aftercare seemed tovary,

over time, but no significant differences were observed. In the

first decade, a substantial number of patients did not have a

1630

auaws 45 (2019) 1625-1633

ee

icun=53 Ward n=32 Outpatient department n=15

Physica

‘wounds (100%) ‘wounds (906%) Wounds (46,7)

Vital Functions (8.2%) Pain 75%) Itching 20%)

Dehydration, fid imbalance (745%) Secretion problems (71.9%)

Pain 70,6) Loss of appetite 69.4%)

Fever (05%) Fatigue (9.4)

Secretion problems (60.8%) Heehing (46.9%)

Fatigue (3,1) Nauseous, Vomiting (438%)

Dehydration, id imbalance (344%)

Fever (311%)

Vital Functions (28.1%)

Mental:

Consciousness disorders (51.0%)

Anxiety, panic (275)

Funeional

Sleep-rest patter problems (23.3%)

Lack of self-reliance (27.5%)

Disturbed mobility (255%)

Lack ofsetfeliance (68%)

Sleep-rest patter problems (68.5%)

Disturbed mobility (625%)

Lack of se management (4:4)

SISITEN specif:

(ral mucosa release (549%)

ye problems (7,1)

Flaky skin (25%)

(Oral mucosa release (625%)

Bye problems (406%)

Pigmentation difference (667%)

ye problems (10%)

Flaky skin (267)

* Selection of problems documented in 220% of patients

record. However, patients with a nursing record received

aftercare (n=5)-In the second decade, only 3/8 (33.3%) received

aftercare, and 13/19 patients received aftercare in the last,

decade (68.4%) (ig. 4). In this period after discharge, only some

problems were documented, and these problems were mainly

related to the physical domain. The most frequently docu-

‘mented problems were small wounds (46.7%), itching (20.0%),

pigmentation differences (46.7%) ocular problems (40.0%) and,

sis

70

60

50

aK

3

2

u

SIS-TEN

m Aftercare

flaky skin (26.7%). No reports on mental health, functional or

social problems were described (Table 3).

3.7. Disease-specifc patient problems

On assessment ofthe disease-specific problems, eye problems,

were prominent in every phase of the disease. During

hospitalization, oral mucosa release was also a problem,

TEN Total

No aftercare

4~ Aftercare based on SIS/TEN type.

auans 45 (2019)

1631

which was observed in approximately two-thirds of the

patients (69.5%) (Table 3) Eye problems (52.5%) were reported

in more than half of patients, Oedema (169%) and food

retention (16.9%) were often reported in the period before

stabilization. Our study showed that hypothermia was also a

problem (119%). after re-epithelilization, flaky skin or

xerosis (18.6%), skin rash (5.1%) and hypo- or hyperpigmenta-

tion (11.9%) were often documented. Nail loosening (5%),

genital problems (5.1%) such as constrictions, and swallowing

problems (6.8%) were described (Table 4).

4. Discussion

‘The main aim ofthis study was to assess nursing problems in,

‘TEN patients in Burn Centre Rotterdam over a 30-year period.

The vast majority of the nursing problems involved the

physical domain of human functioning. A few problems were

escribed in the mental health domain, and some problems in,

the functional domain were documented. Minimal social

domain problems were noted. The secondary objective was to

identify the onset and duration of nursing problems. Most,

nursing problems were reported from days three to 20 after

onset of the disease. Only a selection of general nursing

problems as described by Schuurmans et al, in the general,

nursing literature was documented in TEN and SJS patients

[17]. TEN disease-specific problems were similar to those

described in the medical literature [7]

Information on nursing problems in TEN-SJS patients is

limited, impeding comparison with relevant nursing iterature.

However, the medical literature described comparable general,

problems and complications, particularly in patients with

extensive epidermal loss. These problems include severe pain,

hypothermia, probleme with swallowing (dysphagia), drooling,

‘malnutrition, diarthoea, oliguria, haematuria, dehydration,

invasive infections, sepsis and multiorgan failure, as well as,

problems with vital functions and TEN-specific complications,

such as oral, ocular, genital and intemal mucosa problems,

1,78}. Thisis the frst study to providean overview of recorded

nnursingproblems in S)S/TEN patients, With this knowledge, we

can develop optimal interventions to address nursing prob:

lems. Our paper represents a valuable contribution to the

Jmowledge on nursing care for TEN patients,

ic patient proble

Disease specific patient problems’

‘Oral mucosa release

ye problems

Flaky skin

edema

Food retention

Hypothermia 9

Pigmentation diferences ng

Onycholyss (nail loosening) as

Swallowing problems 6a

(Genital problems sa

Skin ash sa

‘Seen in at last ten patient

‘Weesystematically examined the provision of aftercare and

the documented problems. Although the frequency of after-

care varied over time, two of three patients were seen in our

outpatient department after discharge in the last decade. A.

potential reason why not all patients were followed up is that,

some patients return to the referral hospital after overcoming

their skin problems to receive treatment for their initial

disease. However, evaluating the post-treatment experiences,

of patients is essential to provide relevant information and,

patient education,

Lecet al. recently developed an assessment too for chronic

sequelae after TEN for evaluation in the follow-up period after

TEN episode [9]. This 30-item tool assesses eight domains,

including general, psychiatric, skin, eye, mouth, respiratory,

‘urogenital and gastrointestinal problems [9}. In our opinion,

systematic outpatient monitoring using such an instrument

would support our patients and would add to ourexpertiseas.a

specialized centre for TEN patients. Lee et al. suggested

conducting a large prospective study to broaden our insights,

into the extensiveness of complications and sequelae after

surviving TEN [9]. Such information can help us optimize our

care both in the acute phase and post discharge.

Recently, the Dutch burn centres started @ project to

‘measure outcomes in bum centre patients, including TEN

patients; these outcome data will be used to develop aftercare

strategies to support patient-centred care and shared deci

sion-making

After assessment and diagnosis of TEN patients, the next

step is to address nursing interventions. Traditionally, burn

centres play a central ole in the care for these patients. Even,

for our centre, which is appointed as an expertise centre, TEN,

is a rare disease. Recently, Lerma and colleagues conducted a

survey on nursing care in TEN patients in specialized units and,

‘burn unite in Spain and abroad. They showed variety

nursing care for TEN patients in the 19 participating burn units,

or specialized units. Based on their comparison, they suggest

improvements in ocular and genital eare, They concluded that

‘a consensus on nursing care guidelines is needed to help

reduce mortality and morbidity in TEN [18}, Therefore, gaining

and sharing knowledge to determine the optimal intervention,

strategy are even more important.

(Our study identified some clinical implications. Expertise

centres aim to improve the quality of care, However, more

nursing research and education are needed to optimize

knowledge among all nurses in burn centres or specialized,

centres, First, based on our analysis, a checklist including the

most common nursing problems can be developed. This

checklist can be used to improve the care and the quality of

documentation in the acute phase. The list generated by Lee

et al. is available for documentation during aftercare [9].

Second, education regarding the specific needs of these

patients should be provided on a regular basis. An example

of such education is to add a paragraph describing the

expected problems after SJS/TEN in the discharge letter to

the referring physician, as Creamer et al. suggested in their

guidelines [4], Third, each burn centre should ideally have a

disease management nurse for SJS/TEN to guarantee contin

ous attention. Fourth, every patient with S)S/TEN should have

at least one follow-up visit with an aftercare nurse/burn,

specialist to receive structural aftercare as needed.

1632

auaws 45 (2019) 1625-1633

5. Limitations

ur study has a few limitations. Our patients represent a

selection of more extensively injured patients because they

hhad been transferred to a burn centre for specialized care. In,

addition, data were incomplete for some patients, especially in,

the frst years ofthe study before the introduction of electronic

patient files. However, the nature and timingof their problems

are similar to the problems that we documented in more

recent years. Thus, this factor doesnot influence the validity of

our study as indicated by the comparable length of stay and

percentage of denuded skin in patients with and without

documentation. Next, we assessed the SCORTEN score on the

first day of admission, which is usually approximately four

days after disease onset [8]. Recommendations for the best day

to determine the SCORTEN vary between days 1 and 5 of

‘admission. Measuring the SCORTEN scoreon days 3and Sand,

using the highest risk score have been suggested [19-21]. We

used the classification of nursing problems of the Dutch,

‘Nursing Society based on the NANDA. This classification

provided a good framework for the classification of problems,

in the domains of the system, Some issues provoked

discussion, such as the classification of problems related to

‘anxiety and panic versus uncertainty; however, these issues,

‘were all resolved.

‘Our data collection on nursing problems was based on

patient files. Frequently, nursing problems are intermittently

reported. In addition, only 16 ofthe 41 main nursing problems,

‘were described in more than 20% ofthe patients, and 11 items,

ineluding weight loss, mood disorders and memory disorders,

were not reported at all. Although we must realize that

realistically, not all patients will experience all nursing

problems, we must also realize that a focus on pain and

aftercare was not an issue when the first patients were

reviewed 30 years ago. Awareness of these problems has only

increased in recent years [3] In seriously ll patients, one would

expect that more nursing problems would be apparent, such as,

‘mental health problems, including mood disorders, stress,

loss, uncertainty, shortage of knowledge, and ineffective

coping. One remarkable finding is that social problems, such

‘8 participation problems or loneliness, are only occasionally,

documented, especially given the response of patients to their

newly disfigured appearance. Whether patients do not

experience these problems, whether nurses do not notice

these problems, or whether these problems are not sufficiently

important for nurses to record remains unclear, We could not

answer these questions in this study. A future prospective

study with systematicscreeningof potential problems for each,

patient may clarify this issue,

‘Conclusion

‘This is the firet study to provide an overview of recorded

‘nursing problemsin TEN and SJS patients, Themost frequently

reported nursing problems were in the physical domain,

ceepecially on days three to 20 fter onset ofthe disease. With

this knowledge, we can initiate nursing interventions early in,

treatment, address problems at the first signs, and inform,

patients and their families or representatives early in the

process. A next step toimprove nursingcare for TEN patients,

toacquire knowledge on the optimalinterventions for nursing

problems,

(0) Harr, French LE, Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens

Johnson syndrome. Orphanet ) Rare Dis 2010;1:38.

[2] Palmieri TL, Greenhalgh D, Saffle J, Spence R, Peck M, Jeng,

etal A multicenter review of toxic epidermal necrolysis,

treatedin USbum centers at theendof thetwentieth century.)

Burm Care Res 2002:2:87-96

[2] Bastuji-Garin, Rzany B, Stern RS, Shear NH, NaldiL, Roujeau).

Clinical classification of cares of toxic epidermal necralysis,

Stevens Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme, Arch

Dermatol 1995;192-6,

Creamer D, Walsh 5, DriewulskiP, Exton L, Lee H, Dart, eta

UK guidelines for the management of StevensJahnson

syndromeltaxie epidermal necrolysis in adults 2016. Br}

Dermatol 2016;6)1194-227

Baccara LM, Sakharpe A, Miller A, Amani H. The first reported

case of ureteral perforation in a patient with severe toxic

epidermal necrolysis syndrome, Burn Care Res 2014;4:e265-8

{61 Oplatek A, Brown K, Sen 8, Haler2 M, Supple K, Gamelli RI.

Long-term follow-up of patients treated for toxic epidermal

necrolysis.) Burn Care Res 2006;1:26-33

{71 Cartotto R. Burn center care of patients with Stevens Johnson,

syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Clin Plast Surg

20173358395

{8] Ocni, ViiesC, Rocleveld ¥, Dokter J, Hop MI, Baar M.

Epidemiology and costs of patients with toxic epidermal

necrolysis: 27-year retrospective study.) Eur Acad Dermatol

Venereol 2015;12:24450.

[9] Lee H, Walsh 5, Creamer D. Long term complications of,

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/Toxic epidermal necrolysis: the

spectrum of chronie problems in patients who survive an

episode of SJS/TEN necessitates multi-dsciplinary follow up.

Br Dermatol 2017.

[ao] Secaynska B, Nowak I, Sega A, Kozka M, Wodkowski M,

Krolikowski W, etal. Supportive therapy fora patient with

toxic epidermal necrolysis undergoing plasmapheresis. Crit

Care Nurse 2013;4:26:38.

[11] Cooper KL. Drug reaction, skin cae, skin loss. Crit Care Nurse

20124525,

[12] xu1, Zhu, Yu), DengM, ZhuX.Nursingcareofaboy seriously,

infected with Steven Johnson syndrome after treatment with

azithromycin: a case report and literature review. Medicine

201851209112,

[03] Mccarthy KD, Donovan RM. Management ofa patient with

toxic epidermal necrolysis using silicone transfer foam.

dressings and a secondary absorbent dressing, ) Wound

Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016365041,

[14] Ackloy 8}, tadwvig GB. Nursing diagnosis handbook-e-book: an

evidence based guide to planning care, Elsevier Health

Sciences; 2010

[15] Doenges ME, Moorhouse MP, Murr AC. Nurse's pocket guide:

diagnoses, prioritized interventions, and rationales FA Davis.

2016.

[16] Fouchard N, Bertocchi M, Roujeau J, RevuzJ, Wolkenstein P,

Bastuji-Garin S, SCORTEN: severity-of illness score for toxic

epidermal necrolysis.) Invest Dermatol 2000;2-149-52.

[27] Schuurmans m, Lambregts J Projectgroep V, Grotendorst A,

Deel 3: Beroepsprofel verpleegkundige. Leen van de

toekomst. Verpleegkundigen & verzorgenden; 2012. p. 107-56

2020,

tl

|

auans 45 (2019) 1625-1623

[15] Lerma V, Macias M, Toro R, Moscoso A, Alonso V, Hernandez,

etal. Care in patients with epidermal necrolysis in burn units

‘A nursing perspective. Burns 2018

{19} Guegan 5, Bastji-Garin Ss, Posrepezynske-Guigné , Roujent),

Revie]. Performance ofthe SCORTEN during the fist five days

of hospitalization to predict the prognosis of epidermal

necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol 2006;2:272-6,

{20} Sekula, Liss V, Davidoviei 8, Dunant A, Roujent), KardaunS,

etal Evaluation of SCORTEN on a cohort of patients with

1633

‘Stevens Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

Included in the RegiSCAR study. )Burn Care Res 2011;2:237-45,

[at] Bansal, Garg VK, Sardana K, Sarkar RA clinicotherapeutic

‘analysis of Stevens Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal

necrolysis with an emphasis on the predictive value and

accuracy of SCORe of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. nt}

Dermatol 2015;1:618-26.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Lamps Led Catalogs EsDocument57 pagesLamps Led Catalogs Esedwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

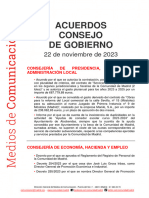

- Acuerdos Consejo de GobiernoDocument11 pagesAcuerdos Consejo de Gobiernoedwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- Uso Del AparatoDocument2 pagesUso Del Aparatoedwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- Cuidado EnfermeriaDocument5 pagesCuidado Enfermeriaedwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- Síndrome de Stevens-Johnson. Informe de 7 Casos: RtículooriginalDocument8 pagesSíndrome de Stevens-Johnson. Informe de 7 Casos: Rtículooriginaledwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- SJS-TEN-summary-of-treatment-2-pages TRADUCCION CUADOR QUE HACERDocument2 pagesSJS-TEN-summary-of-treatment-2-pages TRADUCCION CUADOR QUE HACERedwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- Insuficiencia Cardiaca 1Document72 pagesInsuficiencia Cardiaca 1edwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- Estrategias Metodológicas en La Formación Profesional para El Empleo Según Modalidad de ImparticiónDocument101 pagesEstrategias Metodológicas en La Formación Profesional para El Empleo Según Modalidad de Imparticiónedwin fernando pestana tirado100% (1)

- Resumen FGPenalvoDocument3 pagesResumen FGPenalvoedwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- En PortuguezDocument15 pagesEn Portuguezedwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- 10 Vol09 Num01 2023Document6 pages10 Vol09 Num01 2023edwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- 0410 1870Document18 pages0410 1870edwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- Trabajo Fin de Grado: Mejorar La Calidad de Vida de Adolescentes Con Síndrome de Stevens - JohnsonDocument50 pagesTrabajo Fin de Grado: Mejorar La Calidad de Vida de Adolescentes Con Síndrome de Stevens - Johnsonedwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- Document TraduccionDocument9 pagesDocument Traduccionedwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- Precisiones Sobre El Jubileo de La Iglesia de Los Capuchinos, de CabraDocument4 pagesPrecisiones Sobre El Jubileo de La Iglesia de Los Capuchinos, de Cabraedwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- 3339 - Síndrome de Stevens-Johnson - Uma Revisão BibliográficaDocument15 pages3339 - Síndrome de Stevens-Johnson - Uma Revisão Bibliográficaedwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- ES El Perdón de AsísDocument3 pagesES El Perdón de Asísedwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- Porciuncula HistoriaDocument9 pagesPorciuncula Historiaedwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- El Perdón de Asís y La PorciúnculaDocument1 pageEl Perdón de Asís y La Porciúnculaedwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet