Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Albanian Invention of Nationalism Myth Amnesia

Albanian Invention of Nationalism Myth Amnesia

Uploaded by

Contributor Balkanchronicle0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views9 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views9 pagesAlbanian Invention of Nationalism Myth Amnesia

Albanian Invention of Nationalism Myth Amnesia

Uploaded by

Contributor BalkanchronicleCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 9

INVENTION OF A NATIONALISM.

MYTH AND AMNESIA

Piro Misha

san élite phenomenon: the very idea ofan Albanian nation germinated

first in the minds of a handful of

country, mostly in Europe, but als

economic centres of the Ottoman Empire, The initial impulse and

ration came from the European Enlightenment, as well 2s from

the influence of the writings of a mumber of Western scholars, tavellers,

poets, ethnographers and p}

forgotten part of Europe, whi

ethnographic communi

well to reconstruct pieces of th

Common with the other nat

identification became linguistic and cultural. [t was a process which

3

4 Piro Misha

in the long run brought about fundamental change by devaluing the

pt that for centuries had constituted the esence of Oiton

¢ bases of Islamic or Orthodox unity whic

seeds of Balkan nationalism, including the Albanian national mc

sprouted.

"The process of Albanian nation-building cannot be fally understood

unless we put it in the context of the nineteenth-century Balkans,

chacacterised by severe contficts and confrontations among the newly.

created Balkan nation-states king to define their national

‘were constructing their national myths, codes, symbols,

i policy of territorial expansion as

tional homogenisation. The Albanians

ng

‘Numerous parallels exist between the Albanian national move~

and the other nineteenth-century Balkan national movement

npostant differe

phy: The process of nation-building a

own distinct

also forced to make thei

the acknowledgement of the

malism: Myth and Ammesia 35

ced at the time all over the Balkans and many of

enough simply to observe their late departure along the road to

modernity, one should also explain why. What prevented the Albanians

region? This

leads to a number of other questions requiring a critical examination

of the past and questioning much of what is taken for granted by the

‘An answer should be found to the question why the Albanians

‘were among the last to liberate themselves since they initially resisted

the Ottoman invasion more vigorously and for longer than most of

their neighbours, and curing the first centuries of Ottoman role revolted

pethaps more often than any other people in the region.? This is

particularly perpl xms of the distance to

the centre of the Empire and the proximity to Western Europe) was

the change of the name the Albanians had

this period a mu

‘transformations with long-term consequences took place in Albanian

-ausing the change not only of name but also of religion. It

36 Piro Misha

Albania of the last evo centuries without taking

umber of

before the ct

backward and i

pared to thei

which most of theie neighbours had

known on their road towards the affirmation of distinctive national

identity. Albanians were cut off from contacts with the rest of the

‘world even ifjudged according to the standards of the Ottoman Empire.

Albania continued to remain a mysterious country, an image that pur-

sued it fora very long time. Even as late as 1913 the French journalist

Delaisi wrote:

pastes. Bur even withot

very difficult, which mea

cessary for the creation of the awareness of:

orto Vlora, The Albanian poet Asdreni, who lived in Bucharest, rav-

cllingit in 1903, wrote that ajourney from the port of Duarres,

where he landed, to 40

te. ‘Only 2 horse or

‘paths can travel here, The

‘a traveller com:

this happens more because the man who shoots does not

‘wasting a bullet just for a passer-by’® A report written by the Intelli-

ia 37

gence Division of the British Admiralty Staff'in 1916, during the

First World War came to the conclusion that one of the main factors

causing the extreme stagnation of Albania was the geographical en-

vironment

Another major obstacle (although strangely enough itis rarely men

cir lack of a single admit

es, often became factors of discord.

Examining the nineteenth-century history of Albania it is easy

to see how many of the major obstacles the Albanians faced in

ng to construct a national identity are to be

Octtorman policy in the lst centuries of their rule in Albania, Feeling

regional and religious div

be the best way of c

the Empire. Because ofits strategic borderland po:

considered by the Sublime Porte not only as a borderland defensive

belt, but also as an important source of cheap cannon-fodder. ‘To this

end the Ottomans did their best to keep the country isolated and

uncontaminated by contacts with Europe. Paradoxically, the geographi-

38 Pio Misha

recognise Albanians as such, considering them either:

thodox’ because of the practical implic

what that foxey

ruly meant. They

sographical notion known by the name of

bo too ‘ould be ethnically

also took care that none of these fox

homogeneous.

en most of the factors which normally

help in constructing say the leat, prob-

lematic the last remaining factor which did have the pot

Decome an element of national cohesion was the language. In this

light it becomes clear why the Ottomans undertook severe coercive

‘measures in order to prevent the teaching of the Albani

‘were not allowed to use their own language even when,

‘encouraged

policy was e

to compile a common.

very few Albanians could imagine that their nguage could or should

be written.” By the end of the nineteenth century in the whole of

Albania only two Albanian schools existed, while there were some

5,000 Turkish or Greek schools.

this docs not mean that Albanians were educated. On.

‘World War in the whole region of Mirédita, with

000 people, only three people could wi

ne ofthe few Europeans ited Albania atthe beginning

the twentieth century, an Italian

Invention of Nationalism: Myth and Ai 39

is created in a part ofthe Muslim world, prevailing over the teligions soli

arity In Albania this inhibitory policy extends ao to the Christan pops

Iation (che only case), asthe Turks ae afraid tha they would havea negative

influence on Albanian Muslims.”

‘The fact that education was only available in a foreign language helps

explain why Albanian culture remained principally popular and folk-

Joric and why Albanian nationalism was disadvantaged compared to

tthe general context in which the process of national

formation and, later of national integration, slowly advanced: a context

characterised by strong local and regional awareness, while the national

consciousness remained rather vague. Bernd Fischer described this

situation as fol

‘A combination of indigenous Albanian circumstances and conscious Otto-

man policy succeeded national sentiment tnt the ate

nineteenth century in a clastic eatrot and stick fashion, the Tuckish at

verted Albanian nationalism chrough outright repression 38

well 2s by means which amounted to litle more than bribery.

Forsome time the very existence o

ic the country was very diffic

real nation-building movement

‘not impossible, to maintain,

political national :

‘were events that happened far av

8) in which the Turks suffered a c

dangerous unbalancing of the pre

Balkans, °

Stefan Great Powers called the Congress of Beilin, The

goal of the Congress was a more prudent partition of the Empire among,

the newly created regional nation-states. Among many internationally

relevant decisions, the Congress of Berlin decided to partition among,

°F Guiceiandin, Impreson al

"eno Ske, The Alanon National Aung

Pres 1967, 88

Bernd Fischer, Mire Zep dhe popeka pr uber ne Shaper, Tirana: Gabe}

MCM 1995, p54,

40 Piro Misha

its direct neighbours a number of territories inhabited by Albanians.

For the Albanians the Congress of Berlin sent another quite alarming.

signal, which went far beyond its practical decisions. It di

‘The German

organisation, which marked the transformation of thi

‘mantic national movement into @ real political national movement,

n Albanian nationalist ideology. Although the League of Prizren

eventually filed, defeated militarily by the Turks, it constituted a turning,

in the history of the Albanians. Until then the main preoccupa-

ts was to identify and collect evidence proving

ideology, which

aceelemsted the process of cultural and political fermentation that would

lead not only fo the creation, a few decades later, of an Albanian

independent state, but which helped bring the Albanian Question to

the attention of the world.

nediate objective of preventing the partition

ies among its neighbours, the Albanian

national movement had more or less the same platform as any other

national movement during its affirmation phase. In short, demas

culturally and

afew decades compared

ighbours. the generally defensive

the Albanian national movement. For Albanian nineteenth

century nationalists national affirmation meant first of all a way of

Invention of a Nationalism: Myth and Amnesia 4

interrupting what they considered to be ‘the already advanced process

of erosion of sentiment and nat ge

unifying ele-

ber of danger-

e language

centrifugal forces wa

mn and that of e

the basic demand of Albani

transformed from a simple q)

‘The recreation of the past is an

which makes a people a nation. Th

But history itself was not sufficient as

to be known as the ‘nationalisation of history’ ente:

Albanian nationalists the reconstruction of the past was important,

to give evidence to the Albanians that they shared a common histot

that they had been liv

their neighbour

movement which was faced with a very

carried out by Greek and Serb

zeal not only denied the existence of an Albanian nation, but went

to extremes, such as in the case of a propaganda

French and German by a former Prime Minister of Serbia, Vladan_

Georgevitch, who tried in earnest to convince the world that Albanians

were so underdeveloped that they still had

there if not for ever, at least

‘tamil Kadare, Kom shptore page

pi.

'Vladan Georgevitch, Les Albans ts gandes pin

(German eranlation by Prince Alexis Kar-Georgevit

42 Piro Misha

‘Consequently the dividing line between myth and history was often

theory and others were replaced by

‘which was more convincing because it was supported by a number of|

scholars, The Illyrian descent theory soon became one of the principal

pillars of Albanian because of ts importance as evidence

of Albanian

torical continui , he south

fact that the Albanian national symbol

Kastrioti emblem," derived from it, was almost never mentioned because

‘Orthodoxy in 3 country where the

the writings o Albanian p

‘one finds numerous metaphors and images expr

slorious past where a true but dormant identity ofthe Albanians was

to be found. Naum Veqilarshi,'® one remarkable personality of the

firstperiod of the Albanian national movernent, compared the situation

of the Albanians with that of a larva that one day would become a

butterfly, The Arbéreshi!® sang fall of homesickness about ‘the great

time of Arb %

the Albanian nationalist project was to create the appropriate conditions

forsuch an ‘awakening’ (the national awakening, the national revival).

Viewed in this perspective, as with any nationalism, Albanian nationzlism

ed by

he practi

ore complicated. After centuries of terethnic

1 name ofthe medieval family of Georg Kastor, known aso

(1767-1840) wa the fr ideologue ofthe Albanian national

ley. They are descendants of Albanian popalation groups

the Ozomans.

Tues

ofa

coexistence in a multinational empi

heroic tragedy had

myth, Skanderbeg was

‘whose memory was still live in oral tradition, especially among the

Arbéreshi, The nationalist writers needed to do nothing more

subjecting him to chat laboratory that serves to transform history into

myth. As with most myths, his figure and his deeds became a mixture

‘was made a national hero although his d never really involved

all Albanians. Neither Kosovo nor most parts of the south were ever

included. An attempt he made in 1455 to take the city of Bera in fact

es, tis religious dimension needed to be

anderbeg became simply the national hero of

numerous foes over the centuri

But the transformation of Skanderbeg. into a national symbol did

myth became the

tional argument proving Albania’ cultural affinity to Europe. This

44 Piro Misha

[At this poinc it would be well to

misunderstanding of what has bee

simple when we speak of the

Europe. The Albanian collectv

Orient close by adding a further co

ous contradictions and ambigui

ake a clarification to avoid any

so far, because nothing is

in which to feel secure and protected. Yet there are contrasting images

‘of Europe the faithless’, Europe the inimical cause of many wrongs

done to Albanians including their partion, Europe the immoral,

‘old whore’ ete. Both these conceptions of Europe are part ofthe

same pattern, On the one hand, there is the notion of being part of

Europe, of is civilisation, for which the Albanians sacrificed them

from the Ottoman hordes. On

of as being threatening, slippery and

be avoided.

Part of

(created in the nineteenth century and tei

1913 when a major part of the Albanian-inhabited ten

.ed among neighbouring, Balkan

an important elemes

relations with history. The use of history by nat

image of a people as permanent victims constitutes an obstacle

cal mentality,

ed by a belated independence as well as an ideal impressio:

ration, may have created for the Albanians the

some of the features of the

as well as some of the

‘most distressing manifestations of the post-communist period

“What does being Muslim or b

Albanianism?" asked Faik Konic:

"Paik Konic, Albania, 25 Apsil 1897, p18,

45

suming an

ans, the majority

1e sworn enemy of

nians were aso the only

only as a factor of discord but also asa ve

‘This explains the particular secu

wh de it resemble West European types of nat

than Balkan types.

‘The concern for religion as the potential seed

the religious factor. Som

as a pan-Albanian rel

to arrangean

xeation of the Albanian state, Zo,

and minimising their outside connections. The refor

‘Albanian Islam and the efforts to achieve an autocephal

dhe jane Shape, Tiana: Elena Giika

in National Awakening, pp. 77.175.

46 Piro Misha

1e most radical way. After fighting at length against

sciously aspired? writes Peter Bartl In 1912/13 there were

‘who seriously doubsed the capacity of Albanians, if left alone,

their own national state. ‘No Albanian, ifwe exclude only a few hot-

hheads that have no idea of what isthe real situation inside the country,

‘would dream of an independent Albania’ Eqrem Be} Vlora wrote at

the time (despite these misgivings he became a member of the first

parliament a few years later)! After almost 500 years of

2 Muslim major

‘Albania was more influenced by Turko-Oriental cultu

he region. As Bernd Fischer writes, ‘although

vomans were severed in 1912, ast

negative Ottoman legacy remained .. A unique Wellans

inicluded a strong distrust of government and of the

city as well

‘As late as 1922, that is ten years after the proclamation of}

pendence, only 9 per cent of the land was arable at a time when

population lived either from ageiculture or

from animal husbandry. These figures help us to imagine the extreme

poverty in which Albanians lived. Inadequate inftastructure and the

lack of transport facilities and commmunications in the carly period

of statehood continued to exist as described above. Albania remained

a divided country after it had become a ngtion-

levelopi

creating che necessary normative framework which would make

possible sate control over society. It also meant minimising the many

reer Bart), Die Alain Muslme aur Zant der National Unabhingigheishoora,

(1878-1912), Wiesbaden: Otto Harrasowiez 1968, p 282.

2 pid, p. 217

2Facher, MBreti Zag p56.

sia 47

ral cleavages inherited ftom the past through

‘socialising’ and integrating the Albanians into one homogeneous

ideology of ral and h weritage. At the same time,

the demarcation of borders had left almost half of all Albanians outside

, while their neighbours never really dropped

ed, pr

jty of Albanians in their territo

ae was given such special importance isthe

ipulsory military

fe use of history continued, but this was no

the purpose ofsocial cohesion, History served

timise Albanian leaders and their policies, For example, both Zog

jr best to present themselves asthe heirs of

‘communist period this logic reached Orwellian

dimensions in the faking of historical photographs and

48 Piro Misha

ofthe Second World War, led by Enver Hoxha, became the glorious

epilogue to a long tradition of fighting (“The Albanians have passed

through history sword in hand’), Gradually, Albanian Commu

carried the manipulation of history to the level of paranoia, a

schizophrenia, and made Albania one of the world’s mo

countries dominated by a climate of terror and suspicion.

|

|

|

i

j

THE ROLE OF EDUCATION IN THE

FORMATION OF ALBANIAN IDENTITY

AND ITS MYTHS!

Isa Blumi

‘Since the second half ofthe nineteenth century, the Ottoman vileyets

‘of Kosova (Kosovo), Yanya (Ioannina), Manastr (Monastir), and Ishkodra

(Shkodra)” populated by a large Albanian-speaking majority, bore the

brunt of the Balk sive shifts in political economy, demography

and power. In this context, these Albanian-speakers were at once Vital

rurtents external to

dispersed and fragment « proved to be es

to this period of transition,

‘The factors that shaped the numerous in and around the

question of local education take on imperial dimensions during the

latter half of the nineteenth century. These factors have often been

identified in terms of sectarian allegiances—Orthodox, Catholic,

Muslim—whieh in turn inform notions of ethnicity based on geo

le states. Within the simplistic constructs of the

7The Oxcoman spellings will be

sdmioisrative unite sch at layets and kat,

See Isa Bhai, “The Comsmiodiication of Otherness and the Ethnic Unit in

49

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Weldhaim Report Pt2Document6 pagesWeldhaim Report Pt2Contributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Serbias Sandzak Under MilosevicDocument22 pagesSerbias Sandzak Under MilosevicContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Recommendatioin Chinise TurkishDocument1 pageRecommendatioin Chinise TurkishContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Weldhaim Report Pt1Document13 pagesWeldhaim Report Pt1Contributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Amor Masovic Testimony To US CongressDocument5 pagesAmor Masovic Testimony To US CongressContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Albanian Pursuit Ofeducation in Native Language in KosovoDocument9 pagesAlbanian Pursuit Ofeducation in Native Language in KosovoContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- North American Albanian ImmgrationDocument7 pagesNorth American Albanian ImmgrationContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Who Is Playing Russian Roulette in SlovakiaDocument150 pagesWho Is Playing Russian Roulette in SlovakiaContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Soldier of Fortune (1993'02) 7PDocument7 pagesSoldier of Fortune (1993'02) 7PContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Reconstructing The Meaning of Being Montenegrin - by Jelena DzankicDocument25 pagesReconstructing The Meaning of Being Montenegrin - by Jelena DzankicContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Black Muslims in AmericaDocument296 pagesBlack Muslims in AmericaContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- President Soccer Hooligans Undrworld NYTDocument16 pagesPresident Soccer Hooligans Undrworld NYTContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Chetniks Encyclopedia of HolocaustDocument9 pagesChetniks Encyclopedia of HolocaustContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- BC Interview ENDERUN-The Bridge On The River DrinaDocument8 pagesBC Interview ENDERUN-The Bridge On The River DrinaContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Community Education: To Reclaim and Transform What Has Been Made InvisibleDocument18 pagesCommunity Education: To Reclaim and Transform What Has Been Made InvisibleContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

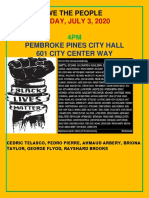

- Pembroke Pines City Hall 601 City Center Way: FRIDAY, JULY 3, 2020Document2 pagesPembroke Pines City Hall 601 City Center Way: FRIDAY, JULY 3, 2020Contributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Tracking 2020census ResponseRate 04142020Document1 pageTracking 2020census ResponseRate 04142020Contributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Latinos and The Transformation of American ReligionDocument12 pagesLatinos and The Transformation of American ReligionContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Risk of Being Killed by Police Use of Force in The United States by Age, Race-Ethnicity, and SexDocument9 pagesRisk of Being Killed by Police Use of Force in The United States by Age, Race-Ethnicity, and SexContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Glasnik Islamske Zajednice 2010Document6 pagesGlasnik Islamske Zajednice 2010Contributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Arab Muslim Attitudes Toward The West - Furia - LucasDocument22 pagesArab Muslim Attitudes Toward The West - Furia - LucasContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Mladi Muslimani Interview Alija Izetbegovic TrhuljDocument8 pagesMladi Muslimani Interview Alija Izetbegovic TrhuljContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet

- Balkan Dreams of EmpiresDocument1 pageBalkan Dreams of EmpiresContributor BalkanchronicleNo ratings yet