Professional Documents

Culture Documents

(PERSONALIDADE) Childhood Maltreatment Increases Risk For Personality Disorders During Early Adulthood (JAMA 1999)

(PERSONALIDADE) Childhood Maltreatment Increases Risk For Personality Disorders During Early Adulthood (JAMA 1999)

Uploaded by

dilsohCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Mscaa Practice Paper 1 Dec2017 1 1Document29 pagesMscaa Practice Paper 1 Dec2017 1 1Helen VlotomasNo ratings yet

- Child Maltreatment and Mental Health Problems in Adulthood Birth Cohort StudyDocument6 pagesChild Maltreatment and Mental Health Problems in Adulthood Birth Cohort Studyfotosiphone 8No ratings yet

- 3 PDFDocument7 pages3 PDFAltin CeveliNo ratings yet

- Reported Pathological ChildhoodDocument7 pagesReported Pathological ChildhoodMartha Lucía Triviño LuengasNo ratings yet

- Pedi 2019 33 425Document8 pagesPedi 2019 33 425Adisty DokiNo ratings yet

- Very Early Predictors of Adolescent Depression and Suicide Attempts in Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity DisorderDocument12 pagesVery Early Predictors of Adolescent Depression and Suicide Attempts in Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity DisorderhimeNo ratings yet

- The Role of Childhood Traumatization in The Development of Borderline Personality Disorder in HungaryDocument14 pagesThe Role of Childhood Traumatization in The Development of Borderline Personality Disorder in HungaryrahafNo ratings yet

- Mental HealthDocument7 pagesMental Healthcooperpaige34No ratings yet

- Prevalence and Correlate - PreadolescenceDocument10 pagesPrevalence and Correlate - PreadolescenceFlóra FarkasNo ratings yet

- BulliedDocument13 pagesBulliedBarry BurijonNo ratings yet

- Childhood Trauma and Children's Emerging Psychotic Symptoms: A Genetically Sensitive Longitudinal Cohort StudyDocument8 pagesChildhood Trauma and Children's Emerging Psychotic Symptoms: A Genetically Sensitive Longitudinal Cohort StudyVikramjit KhangooraNo ratings yet

- HodginsDocument6 pagesHodginsFrixos StephanidesNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument18 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptKc RiveraNo ratings yet

- Psychotic-Like Experiences in Offspring of Parents With Bipolar Disorder and Community ControlsDocument37 pagesPsychotic-Like Experiences in Offspring of Parents With Bipolar Disorder and Community ControlsandindlNo ratings yet

- Halusi JurnalDocument16 pagesHalusi JurnalVitta ChusmeywatiNo ratings yet

- NIH Public AccessDocument13 pagesNIH Public AccessJuan Alberto GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Pedophilia JAMA 2002 Review TherapyDocument8 pagesPedophilia JAMA 2002 Review TherapyW Andrés S MedinaNo ratings yet

- AlcoooDocument8 pagesAlcooofilimon ioanaNo ratings yet

- Pediatic Acuired Immunodeficiency SyndromeDocument6 pagesPediatic Acuired Immunodeficiency Syndromeahmad iffa maududyNo ratings yet

- Body Image and Risk Behaviors in Youth With HIVDocument6 pagesBody Image and Risk Behaviors in Youth With HIVMorrison Omokiniovo Jessa SnrNo ratings yet

- Child and Adolescent Maltreatment Patterns and Risk of Eating Disorder Behaviors Developing in Young AdulthoodDocument9 pagesChild and Adolescent Maltreatment Patterns and Risk of Eating Disorder Behaviors Developing in Young AdulthoodVivian BandeiraNo ratings yet

- Early Childhood Predictors of Boys' Antisocial and Violent Behavior in Early AdulthoodDocument15 pagesEarly Childhood Predictors of Boys' Antisocial and Violent Behavior in Early AdulthoodVictoria ZorzopulosNo ratings yet

- Bourget 2007Document9 pagesBourget 2007Kiara DattaNo ratings yet

- Paranoia RolDocument1 pageParanoia RolV.pavithraNo ratings yet

- Links Between Childhood Experiences andDocument16 pagesLinks Between Childhood Experiences andgica.bucicNo ratings yet

- Development of Bipolar Disorder and Other Comorbilities en TDAHDocument7 pagesDevelopment of Bipolar Disorder and Other Comorbilities en TDAHCarla NapoliNo ratings yet

- Poorer Subjective Mental Health Among Girls: Artefact or Real? Examining Whether Interpretations of What Shapes Mental Health Vary by SexDocument14 pagesPoorer Subjective Mental Health Among Girls: Artefact or Real? Examining Whether Interpretations of What Shapes Mental Health Vary by Sexsherifgamea911No ratings yet

- (2013) - ExnerDocument10 pages(2013) - Exnerbeatriz.l.oliveira.2300No ratings yet

- Marital Status Childhood Maltreatment Family DysfunctionDocument5 pagesMarital Status Childhood Maltreatment Family DysfunctionMaria Gracia AbadNo ratings yet

- Family Rejection As A Predictor of Negative Health Outcomes in White and Latino Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Young AdultsDocument9 pagesFamily Rejection As A Predictor of Negative Health Outcomes in White and Latino Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Young AdultsMuhammad Naufal FirdausNo ratings yet

- Childhood Bulling Involvement Predicts Low Grade Systemic InflammationDocument6 pagesChildhood Bulling Involvement Predicts Low Grade Systemic InflammationCristiana ComanNo ratings yet

- Running Head: MENTAL DISORDERS 1Document12 pagesRunning Head: MENTAL DISORDERS 1api-532509198No ratings yet

- Child and Adolescent Abuse and Neglect ResearchDocument9 pagesChild and Adolescent Abuse and Neglect ResearchKübraNo ratings yet

- Fruzzetti 2005 OptionalDocument24 pagesFruzzetti 2005 OptionalMacovei Anca0% (1)

- Infant Behavioral Inhibition Predicts Personality and Social Outcomes Three Decades LaterDocument8 pagesInfant Behavioral Inhibition Predicts Personality and Social Outcomes Three Decades LaterTaakeNo ratings yet

- Kendler-Childhood Parental Loss.1992Document8 pagesKendler-Childhood Parental Loss.1992Zsófia OtolticsNo ratings yet

- Family Characteristics and Behavior Problems of Suicidal and Non-Suicidal Children and AdolescentsDocument14 pagesFamily Characteristics and Behavior Problems of Suicidal and Non-Suicidal Children and AdolescentssaNo ratings yet

- 122 Full PDFDocument8 pages122 Full PDFcassieNo ratings yet

- Wood 1976Document8 pagesWood 1976Arif Erdem KöroğluNo ratings yet

- Duffy2013 PDFDocument8 pagesDuffy2013 PDFFelipe VergaraNo ratings yet

- Childhood Abuse, Neglect, and Household Dysfunction and The Risk ofDocument11 pagesChildhood Abuse, Neglect, and Household Dysfunction and The Risk ofDianaBNo ratings yet

- The Behavior of Anxious Parents Examining Mechanisms of Transmission of Anxiety From Parent To ChildDocument12 pagesThe Behavior of Anxious Parents Examining Mechanisms of Transmission of Anxiety From Parent To Child方科惠No ratings yet

- US National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study: Psychological Adjustment of 17-Year-Old AdolescentsDocument11 pagesUS National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study: Psychological Adjustment of 17-Year-Old AdolescentsGloria StahlNo ratings yet

- The Legacy of Child Maltreatment: Long-Term Health Consequences For WomenDocument6 pagesThe Legacy of Child Maltreatment: Long-Term Health Consequences For WomenRavennaNo ratings yet

- Young Children: Preventing Physical Abuse and Corporal Punishment (2014)Document7 pagesYoung Children: Preventing Physical Abuse and Corporal Punishment (2014)Children's InstituteNo ratings yet

- Adolescent DepressionDocument14 pagesAdolescent DepressionEduardo CañedoNo ratings yet

- Rates of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in YouthDocument9 pagesRates of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in YouthWilson Javier Dominguez PerezNo ratings yet

- Bullying Behaviors Among US Youth: Prevalence and Association With Psychosocial AdjustmentDocument13 pagesBullying Behaviors Among US Youth: Prevalence and Association With Psychosocial AdjustmentAna FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Quantitativo Bullying Maip PDFDocument13 pagesQuantitativo Bullying Maip PDFAna FerreiraNo ratings yet

- (696557968) Sifra JurnalDocument9 pages(696557968) Sifra JurnalSifra Turu AlloNo ratings yet

- Pedophilia and DSM-5: The Importance of Clearly Defining The Nature of A Pedophilic DisorderDocument4 pagesPedophilia and DSM-5: The Importance of Clearly Defining The Nature of A Pedophilic DisorderEmy Noviana SandyNo ratings yet

- Gri Zenko 1994Document11 pagesGri Zenko 1994Alex BoncuNo ratings yet

- Sills 2007Document10 pagesSills 2007hotorunNo ratings yet

- Risk of Mental Illness in Offspring of Parents With Schizophrenia, BipolarDocument11 pagesRisk of Mental Illness in Offspring of Parents With Schizophrenia, BipolarOkta BarraNo ratings yet

- Associations Between Four Types of Childhood Neglect and Personality Disorder Symptoms During Adolescence and Early Adulthood: Findings of A Community-Based Longitudinal StudyDocument17 pagesAssociations Between Four Types of Childhood Neglect and Personality Disorder Symptoms During Adolescence and Early Adulthood: Findings of A Community-Based Longitudinal StudyUmer FarooqNo ratings yet

- AmericanDocument13 pagesAmericanDavid QatamadzeNo ratings yet

- Lister, 2015Document7 pagesLister, 2015Bianca HlepcoNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument15 pagesNIH Public Access: Author Manuscriptyeremias setyawanNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors in Early Life For Developmental Coordination Disorder: A Scoping ReviewDocument9 pagesRisk Factors in Early Life For Developmental Coordination Disorder: A Scoping ReviewLaura RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Danckaerts2000 Article ANaturalHistoryOfHyperactivityDocument13 pagesDanckaerts2000 Article ANaturalHistoryOfHyperactivitymaksim6098No ratings yet

- Behind the Mask: Revealing the Risk Factors of Psychopathy in Children and AdolescentsFrom EverandBehind the Mask: Revealing the Risk Factors of Psychopathy in Children and AdolescentsNo ratings yet

- PharmacologyDocument141 pagesPharmacologyOmowunmi KadriNo ratings yet

- Endocrine Function Report Ncm114Document91 pagesEndocrine Function Report Ncm114abcde pwnjabiNo ratings yet

- Genetic Mutation and DisorderDocument31 pagesGenetic Mutation and Disorderabrielle dytucoNo ratings yet

- Disfagia Esofágica en Niños. Estado Del Arte y Propuesta para Un Enfoque Diagnóstico Basado en Los Síntomas (2022)Document12 pagesDisfagia Esofágica en Niños. Estado Del Arte y Propuesta para Un Enfoque Diagnóstico Basado en Los Síntomas (2022)7 MNTNo ratings yet

- DebateDocument12 pagesDebate•Kai yiii•No ratings yet

- CSB043 Prostate EBRT 2016 PCDocument53 pagesCSB043 Prostate EBRT 2016 PCPeter CaldwellNo ratings yet

- 3 Interview Transcripts From The Leaky Brain SummitDocument39 pages3 Interview Transcripts From The Leaky Brain SummitJimmy SchibelloNo ratings yet

- Stages of Acute Otitis MediaDocument1 pageStages of Acute Otitis MediaNicole Marie NicolasNo ratings yet

- Cancer WebquestDocument2 pagesCancer WebquestAmaia FiolNo ratings yet

- Overview of Viral MyositisDocument3 pagesOverview of Viral MyositisemirkurtalicNo ratings yet

- Substance-Related Disorders: Professor DR Sirwan K Ali Department of PsychiatryDocument43 pagesSubstance-Related Disorders: Professor DR Sirwan K Ali Department of PsychiatryAlan AhmadNo ratings yet

- Living With AdhdDocument3 pagesLiving With Adhdapi-704337450No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0300289621001745 mmc2Document2 pages1 s2.0 S0300289621001745 mmc2aris dwiprasetyaNo ratings yet

- GREGORY - Demencia Rápidamente ProgresivaDocument47 pagesGREGORY - Demencia Rápidamente ProgresivaUgalde López ReginaNo ratings yet

- ICD 10 CM Coding - DiabetesDocument68 pagesICD 10 CM Coding - Diabeteschaitanya varmaNo ratings yet

- Asco Treatment Summary and Survivorship Care PlanDocument2 pagesAsco Treatment Summary and Survivorship Care PlanFriska Permatasari NababanNo ratings yet

- 05 - 2022 ISI Short Term Application Form - EnglishDocument2 pages05 - 2022 ISI Short Term Application Form - EnglishPapitcha chittipornsanNo ratings yet

- Initation of Insulin - Final 2023Document27 pagesInitation of Insulin - Final 2023DEWI RIZKI AGUSTINANo ratings yet

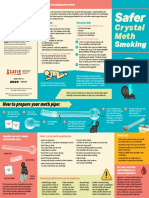

- CATIE SaferSmoking CrystalMeth E 2020 FINAL WEBDocument2 pagesCATIE SaferSmoking CrystalMeth E 2020 FINAL WEBJeff PuglisiNo ratings yet

- The Accuracy of Fibroscan in A Real World StudyDocument2 pagesThe Accuracy of Fibroscan in A Real World StudyRaeni Dwi PutriNo ratings yet

- Juni 23 1Document105 pagesJuni 23 1Isabella MebangNo ratings yet

- Whipple Procedure: Procedure at A GlanceDocument4 pagesWhipple Procedure: Procedure at A GlanceAze Andrea PutraNo ratings yet

- نماذج باثو نظري هيكليDocument2 pagesنماذج باثو نظري هيكليWael EssaNo ratings yet

- OSCE Medicine by DR BilanDocument77 pagesOSCE Medicine by DR BilanBukhaari MohamedNo ratings yet

- M1 Post Task - Caparas-Bsn2a-A2Document2 pagesM1 Post Task - Caparas-Bsn2a-A2Gretta CaparasNo ratings yet

- Tatalaksana Primary Dan Secondary SurveyDocument26 pagesTatalaksana Primary Dan Secondary Surveyakun 31No ratings yet

- BMJ 22-09Document15 pagesBMJ 22-09Kiran ShahNo ratings yet

- DOLOCAN Dolocem CBD Eczema Cream White Paper - 20190917Document1 pageDOLOCAN Dolocem CBD Eczema Cream White Paper - 20190917Petra MitićNo ratings yet

- Homeopathic Heritage February Issue 2024Document94 pagesHomeopathic Heritage February Issue 2024Sumanta KamilaNo ratings yet

(PERSONALIDADE) Childhood Maltreatment Increases Risk For Personality Disorders During Early Adulthood (JAMA 1999)

(PERSONALIDADE) Childhood Maltreatment Increases Risk For Personality Disorders During Early Adulthood (JAMA 1999)

Uploaded by

dilsohOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

(PERSONALIDADE) Childhood Maltreatment Increases Risk For Personality Disorders During Early Adulthood (JAMA 1999)

(PERSONALIDADE) Childhood Maltreatment Increases Risk For Personality Disorders During Early Adulthood (JAMA 1999)

Uploaded by

dilsohCopyright:

Available Formats

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Childhood Maltreatment Increases Risk for

Personality Disorders During Early Adulthood

Jeffrey G. Johnson, PhD; Patricia Cohen, PhD; Jocelyn Brown, MD;

Elizabeth M. Smailes, MA; David P. Bernstein, PhD

Background: Data from a community-based longitu- parental psychiatric disorders were controlled statisti-

dinal study were used to investigate whether childhood cally. Childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse, and ne-

abuse and neglect increases risk for personality disor- glect were each associated with elevated PD symptom lev-

ders (PDs) during early adulthood. els during early adulthood after other types of childhood

maltreatment were controlled statistically. Of the 12 cat-

Methods: Psychosocial and psychiatric interviews were egories of DSM-IV PD symptoms, 10 were associated with

administered to a representative community sample of 639 childhood abuse or neglect. Different types of child-

youths and their mothers from 2 counties in the state of hood maltreatment were associated with symptoms of spe-

New York in 1975, 1983, 1985 to 1986, and 1991 to 1993. cific PDs during early adulthood.

Evidence of childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse, and

neglect was obtained from New York State records and from Conclusions: Persons in the community who have ex-

offspring self-reports in 1991 to 1993 when they were perienced childhood abuse or neglect are considerably

young adults. Offspring PDs were assessed in 1991 to 1993. more likely than those who were not abused or ne-

glected to have PDs and elevated PD symptom levels dur-

Results: Persons with documented childhood abuse or ing early adulthood. Childhood abuse and neglect may

neglect were more than 4 times as likely as those who contribute to the onset of some PDs.

were not abused or neglected to be diagnosed with PDs

during early adulthood after age, parental education, and Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:600-606

R

ESEARCH1-12 HAS indicated Two longitudinal studies25,26 have sup-

that many patients with per- ported the hypothesis that childhood mal-

sonality disorders (PDs) re- treatment increases risk for PDs. Family

port histories of childhood instability and lack of parental affection

abuse or neglect. These find- and supervision during adolescence were

ings, and studies13,14 indicating that PDs are found25 to predict dependent and passive-

more prevalent among persons who expe- aggressive PDs among men. Physical and

rienced child abuse than among matched sexual abuse were not assessed, however,

comparison groups, have suggested that and not all PDs were investigated. Child-

childhood abuse and neglect may play an hoodmaltreatmenthasbeenreportedtopre-

important role in the onset of PDs.15,16 Most dict increased risk for antisocial PD during

early adulthood.26 Neither the association

See also page 607 between different types of maltreatment and

risk for antisocial PD nor the association

of this evidence, however, is based on ret- between childhood maltreatment and other

rospective reports by psychiatric pa- PDswasinvestigated.Therefore,manyques-

tients.17,18 Although research19-22 has sup- tions about the effects of childhood mal-

ported the validity of retrospective reports treatment on the risk for PDs remain un-

of childhood maltreatment, to infer from answered. We report findings from a

retrospective data17,18,23,24 alone that child- community-based longitudinal study to in-

hood maltreatment increases risk for the on- vestigate whether childhood maltreatment

set of PDs is problematic. Until prospec- increases the risk for DSM-IV27 PDs during

From Columbia University and

tive research demonstrates that persons early adulthood independent of the effects

the New York State Psychiatric

Institute, New York with documented childhood maltreat-

(Drs Johnson, Cohen, Brown, ment are at increased risk for PDs inde-

pendent of other risk factors, it cannot be This article is also available on our

and Ms Smailes), and Fordham

University, Bronx, NY established that childhood maltreatment Web site: www.ama-assn.org/psych.

(Dr Bernstein). plays a role in the onset of PDs.18

ARCH GEN PSYCHIATRY/ VOL 56, JULY 1999

600

©1999 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by Edilson Amorim on 11/25/2018

SUBJECTS AND METHODS two items were available to assess 88 (93.6%) of the 94

DSM-IV PD diagnostic criteria. For dependent, histrionic, nar-

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE cissistic, obsessive-compulsive, and paranoid PDs, items were

available for the assessment of 78% to 89% of the diagnos-

Six hundred thirty-nine families with children between the tic criteria. For the other 7 PDs, all criteria were assessed.

ages of 1 and 11 years from 2 counties in northern New The Cronbach a inter-item reliability coefficients for clus-

York State were representatively sampled and interviewed ters A, B, and C PD symptoms were .66, .72, and .68, re-

in 197528 and reinterviewed in 1991 to 1993. These face- spectively. For overall PD symptoms, the a was .87.

to-face interviews, also conducted in 1983 and 1985 to Personality disorder diagnoses were assigned to per-

1986, were administered by extensively trained and super- sons who met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, as reported by

vised lay interviewers.29 At each assessment, written the youth or mother. The use of multiple informants has

informed consent was obtained from all participants after been found33,34 to increase the reliability and validity of psy-

the study procedures were fully explained. The 639 fami- chiatric diagnoses. Evidence32 supports the reliability and

lies in the present study were a subsample of 776 families validity of the protocol items and computer algorithms used

interviewed in 1983 for whom data regarding childhood to assess PD symptoms (J.G.J.; P.C.; Andrew E. Skodol, MD;

maltreatment were available from retrospective self-reports John M. Oldham, MD; Stephanie Kasen, PhD; Judith Brook,

by the young adult participants in 1991 to 1993 and from PhD; unpublished data, 1999). Adolescent DSM-IV PD

the New York State Central Registry for Child Abuse and symptoms predicted early adulthood Axis I disorders and

Neglect (NYSCR). Childhood maltreatment data were not suicidality, and PD symptom stability when the partici-

available for 137 families who no longer lived in New pants were adolescents was similar to the stability of PD

York. These families did not differ from the rest of the symptoms among adults in the community (J.G.J.; P.C.; An-

sample with regard to socioeconomic status, urban vs rural drew E. Skodol, MD; John M. Oldham, MD; Stephanie

status, or ethnicity, but there was a higher proportion of Kasen, PhD; Judith Brook, PhD; unpublished data, 1999).

male offspring and the mothers were less well educated.

The 1983 sample was representative of the regional popu- ASSESSMENT OF CHILDHOOD MALTREATMENT

lation in a range of demographic variables, according to US

census data.29 Demographic characteristics of the sample Official data regarding childhood maltreatment was ob-

are presented in Table 1. Further information regarding tained from the NYSCR. Cases referred to state agencies, in-

the study methodology is available from previous vestigated by childhood protective services, and confirmed

reports.28,29 as verified cases of abuse or neglect are retained in the NYSCR.

The verification of physical abuse required evidence of in-

ASSESSMENT OF PERSONALITY DISORDERS jury. The verification of sexual abuse required evidence of

sexual penetration or a judgment that the youth experi-

Interview items used to assess early adulthood PDs in 1991 enced unwanted sexual contact. The verification of neglect

to 1993 were drawn from the parent and youth versions of required evidence of educational, emotional, physical, or su-

the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children,30 the Per- pervisory neglect. The NYSCR staff ascertained whether con-

sonality Diagnostic Questionnaire,31 and the Disorganizing firmed cases of childhood maltreatment were present. In-

Poverty Interview.28 Items were originally selected by con- formation about the type of abuse was abstracted by one of

sensus among 1 psychiatrist and 2 clinical psychologists based us (J.B.) under the supervision of NYSCR staff. To ensure

on correspondence with DSM-III-R diagnostic criteria.32 Fol- confidentiality, participants were identified only by num-

lowing the publication of DSM-IV,27 items from the study bers, and data were entered by persons who had no access

protocol were added or deleted to maximize correspon- to information that revealed participants’ identities.

dence with DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, most notably to as-

sess depressive PD in DSM-IV appendix B. One hundred fifty- Continued on next page

of offspring age and sex, difficult childhood temperament, and self-reported cases of childhood maltreatment. Only

parental education, and parental psychiatric disorders. 8 cases of childhood abuse or neglect were identified from

both NYSCR records and self-reports, yielding a k coeffi-

RESULTS cient of 0.11. There were 81 (12.7%) documented or self-

reported cases of childhood maltreatment, including 44

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS cases (6.9%) of physical abuse, 22 cases (3.4%) of sexual

abuse, and 39 cases (6.1%) of neglect. Fifty-nine persons

In the 639 families, there were 31 (4.9%) documented cases (9.2%) had 1 type of maltreatment, and 22 persons (3.4%)

of childhood maltreatment, including 15 cases (2.3%) of had 2 or 3 types of maltreatment. Eighty-six youths (13.5%)

physical abuse, 4 cases (0.6%) of sexual abuse, and 23 cases were diagnosed as having PDs in 1991 to 1993.

(3.6%) of neglect. Twenty patients (3.1%) had 1 type of

maltreatment, and 11 patients (1.8%) had 2 kinds of mal- EFFECTS OF CHILDHOOD PHYSICAL

treatment. Fifty-eight persons (9.1%) self-reported child- ABUSE ON PD SYMPTOM LEVELS

hood maltreatment, including 34 cases (5.3%) of physical DURING EARLY ADULTHOOD

abuse, 21 cases (3.3%) of sexual abuse, and 17 cases (2.7%)

of neglect. Forty-six persons (7.2%) had 1 type of mal- Documented physical abuse was associated with elevated

treatment, and 12 persons (1.9%) had 2 or 3 types of mal- symptom levels of antisocial, borderline, dependent, depres-

treatment. There was little overlap between documented sive,passive-aggressive,schizoid,andtotalPDsafteroffspring

ARCH GEN PSYCHIATRY/ VOL 56, JULY 1999

601

©1999 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by Edilson Amorim on 11/25/2018

Self-reports of childhood maltreatment were obtained Nine dimensions of childhood temperament29 were as-

from the offspring in 1991 to 1993. Participants were sessed during the 1975 maternal interviews: clumsiness-

asked whether, before age 18 years, they experienced the distractibility, nonpersistence-noncompliance, anger, ag-

following events: anyone they lived with had ever hurt gression to peers, problem behavior, temper tantrums,

them physically so that they were still injured or bruised hyperactivity, crying-demanding, and moodiness. If a child

the next day, could not go to school as a result, or needed experienced severe problems in 1 or more of these do-

medical attention; they had been left overnight without an mains, the child was identified as having a difficult tem-

adult caretaker before age 10 years; and any older person perament. Difficult childhood temperament has been found,

who was not a boyfriend or girlfriend had ever touched in this sample, to predict behavior problems,36 PDs,37 and

them sexually or forced them to touch the older person Axis I psychiatric disorders during adolescence38 and drug

sexually. use during early adulthood.39

ASSESSMENT OF PARENTAL EDUCATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSES

PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS AND

CHILDHOOD TEMPERAMENT Data analyses were conducted in 5 phases. First, analyses

of contingency tables, correlational analyses, and t tests

Parental education and psychiatric disorders were assessed were computed to investigate whether risk factors identi-

as dichotomous variables. Maternal and paternal education fied by previous research40,41 predicted childhood maltreat-

was assessed during the maternal interviews in 1975, ment and early adulthood PD symptom levels (ie, the

1983, and 1985 to 1986. Low parental education was iden- number of PD diagnostic criteria that were met). Second,

tified in 28.0% of the families, for whom the mean number analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were conducted to

of years of parental education was less than 12. Parental investigate whether documented childhood abuse and

psychiatric disorders were assessed using 4 instruments neglect were associated with elevated early adulthood PD

administered during the maternal interview: current symptoms after offspring age, parental education, and

maternal emotional problems were assessed in 1983 and parental psychiatric disorders were controlled. Third,

1985 to 1986 using the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-9035 logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate

anxiety, depression, and interpersonal difficulty subscales; whether documented childhood maltreatment was signifi-

parental alcohol and drug abuse between 1975 and 1985 cantly associated with the risk for early adulthood PDs

to 1986 was assessed in 1983 and 1985 to 1986; the life- after controlling for offspring age, parental education, and

time parental history of “trouble with the police” was parental psychiatric disorders. Fourth, ANCOVAs were

assessed in 1975, 1983, and 1985 to 1986; and the lifetime computed to investigate whether documented or self-

parental history of psychiatric disorders was assessed in reported childhood maltreatment was significantly associ-

1983 and 1985 to 1986, with items assessing whether or ated with elevated symptom levels of early adulthood PD

not the parents had ever been treated for a mental disor- after controlling for the covariates that were associated

der. Parental psychiatric disorders were considered present with both early adulthood PD symptom levels and other

if significant emotional problems, substance abuse, or types of childhood maltreatment. Fifth, ANCOVAs were

trouble with the police was present in either parent in computed to investigate whether specific types of PD

1975, 1983, or 1985 to 1986 or if, in 1985 to 1986, either symptoms remained significantly associated with docu-

parent had ever been treated for a mental disorder. Using mented or self-reported childhood abuse or neglect after

these procedures, the lifetime prevalence of parental psy- controlling for other types of PD symptoms that were sig-

chiatric disorders was 38.0%. If the mother could not pro- nificantly associated with childhood abuse or neglect. All

vide information regarding the father’s education or psy- statistical analyses were conducted using a comparison

chiatric disorders, only information regarding the mother group that included individuals who did not experience

was used. childhood abuse or neglect.

age, parental education, and parental psychiatric disorders parental psychiatric disorders were controlled statisti-

were controlled statistically (Table 2). Antisocial and de- cally (F1,577 = 5.77; P,.02). Evidence of sexual abuse, ob-

pressivePDsymptomsremainedsignificantlyassociatedwith tained from either NYSCR records or retrospective self-

documentedphysicalabuseaftersymptomsofotherPDswere reports, was associated with elevated symptom levels of

controlled statistically. Evidence of physical abuse, obtained borderline (F 1 , 5 7 7 = 31.09; P,.005), histrionic

from either NYSCR records or retrospective self-reports, was (F1,577 = 11.50; P,.005), depressive (F1,577 = 9.85; P,.005),

associated with elevated symptom levels of antisocial and total PDs (F1,577 = 11.02; P,.005) after controlling for

(F1,599 = 10.62; P,.005), borderline (F1,599 = 16.44; P,.005), offspring sex, parental education, parental psychiatric dis-

passive-aggressive (F1,599 = 6.06; P,.05), schizotypal orders, physical abuse, and neglect.

(F1,599 = 8.13; P,.005), and total PDs (F1,599 = 6.95; P,.01)

after controlling for offspring age, parental education, pa- EFFECTS OF CHILDHOOD NEGLECT ON PD

rental psychiatric disorders, sexual abuse, and neglect. SYMPTOM LEVELS DURING EARLY ADULTHOOD

EFFECTS OF CHILDHOOD SEXUAL ABUSE ON PD Documented childhood neglect was associated with el-

SYMPTOM LEVELS DURING EARLY ADULTHOOD evated symptom levels of antisocial, avoidant, border-

line, dependent, narcissistic, paranoid, passive-

Documented sexual abuse was associated with elevated aggressive, schizotypal, and total PD after controlling for

symptom levels of borderline PD after offspring age and offspring age, parental education, and parental psychi-

ARCH GEN PSYCHIATRY/ VOL 56, JULY 1999

602

©1999 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by Edilson Amorim on 11/25/2018

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics Table 2. Documented Childhood Physical Abuse

of the 639 Sample Offspring and Personality Disorder (PD) Symptoms*

During Young Adulthood

Characteristic Variable

PD Criteria PD Criteria

Age, mean (SD) [range], y

Among Those Among Victims

1975 6.4 (2.6) [1-10]

Not Abused of Physical

1991-1993 22.3 (2.6) [18-28]

or Neglected Abuse

Sex, No. (%) PD Symptoms (n = 608) (n = 15) F1,621†

Male 334 (52.3)

Female 305 (47.7) Paranoid 0.73 (0.89) 1.60 (1.45) 3.47

Ethnicity, No. (%) Schizoid 0.75 (0.87) 1.67 (1.23) 6.65‡

White 575 (90.0) Schizotypal 0.95 (1.05) 1.47 (1.41) 0.10

African American 58 (9.1) Any cluster A PD 2.43 (2.10) 4.73 (3.13) 4.32§\

Other 6 (0.9) Antisocial 1.18 (1.11) 2.20 (1.57) 5.66‡§

Residence, No. (%) Borderline 0.97 (1.15) 2.00 (1.51) 3.94‡

Rural communities and small towns 341 (53.4) Histrionic 1.40 (1.21) 2.00 (1.13) 1.51

Large towns 51 (8.0) Narcissistic 0.86 (1.06) 1.87 (1.60) 4.42‡

Central cities 78 (12.2) Any cluster B PD 4.41 (3.20) 8.07 (4.60) 7.62¶

Suburban communities 169 (26.4) Avoidant 0.72 (0.97) 1.33 (1.45) 1.87

Education, No. (%) Dependent 1.04 (1.22) 2.27 (1.53) 8.67\

,12 y 57 (8.9) Obsessive-compulsive 0.88 (0.88) 1.13 (1.19) 0.33

Any cluster C PD 2.63 (2.25) 4.73 (3.26) 4.87‡

Depressive 0.72 (1.04) 1.53 (1.64) 7.07§¶

Passive-aggressive 0.82 (1.00) 1.47 (1.30) 3.92‡

Any PD 9.83 (6.45) 18.33 (10.35) 10.50\

atric disorders ( Table 3 ). Supplemental analyses

indicated that symptoms of antisocial, avoidant, border- *Data are given as the mean (SD) number of DSM-IV PD criteria met at

assessment interviews conducted during early adulthood.

line, narcissistic, and passive-aggressive PD remained sig- †Results of analyses of covariance, controlling for offspring age, parental

nificantly associated with documented neglect after psychiatric disorders, and parental education.

co-occurring PD symptoms were controlled statisti- ‡P,.05.

§Association remained statistically significant after controlling for

cally. Evidence of neglect, obtained from either NYSCR co-occurring PD symptoms.

records or retrospective self-reports, was associated with \P,.005.

elevated symptom levels of antisocial (F1,594 = 7.41; P,.05), ¶P,.01.

avoidant (F1,594 = 5.71; P,.05), borderline (F1,594 = 17.90;

P,.005), dependent (F1,594 = 7.91; P,.01), narcissistic difficult childhood temperament were controlled statis-

(F1,594 = 7.30; P,.005), passive-aggressive (F1,594 = 10.92; tically.

P,.005), schizotypal (F1,594 = 11.33; P,.005), and total As the Figure indicates, persons who experienced

PDs (F1,594 = 15.27; P,.005) after offspring age, parental childhood maltreatment were at an elevated risk for DSM-IV

education, parental psychiatric disorders, physical abuse, cluster B, cluster C, and appendix B PDs during early adult-

and sexual abuse were controlled. hood. When the effects of co-occurring PDs were con-

trolled statistically, however, only cluster B (adjusted odds

EFFECTS OF ANY CHILDHOOD ABUSE OR ratio = 7.94; 95% confidence interval, 1.33-14.82) and

NEGLECT ON RISK FOR PD DURING EARLY DSM-IV appendix B (adjusted odds ratio = 4.43; 95% con-

ADULTHOOD fidence interval, 1.45-13.87) PDs were independently as-

sociated with childhood abuse or neglect.

Documented childhood maltreatment was associated with

increased risk for antisocial, borderline, dependent, de- COMMENT

pressive, narcissistic, paranoid, and passive-aggressive PDs

after controlling for offspring age, parental education, and The major finding of the present study is that persons

parental psychiatric disorders (Table 4). Antisocial, bor- with documented childhood abuse and neglect in a rep-

derline, narcissistic, and passive-aggressive PD symp- resentative community sample were more than 4 times

toms remained significantly associated with docu- as likely as those who had not been abused or neglected

mented childhood maltreatment after controlling for to have PDs during early adulthood. This finding is par-

symptoms of other PDs. Evidence of childhood abuse or ticularly meaningful because childhood maltreatment pre-

neglect, obtained from either NYSCR records or retro- dicted early adulthood PDs even after the effects of dif-

spective self-reports, was associated with elevated symp- ficult childhood temperament, parental education, and

tom levels of antisocial (F1,637 = 16.26; P,.005), avoidant parental psychiatric disorders were controlled statisti-

(F1,637 = 4.97; P,.05), borderline (F1,637 = 53.96; P,.005), cally. The present findings are consistent with previous

dependent (F 1 , 6 3 7 = 13.59; P,.005), depressive findings1-13,18,25,42-45 suggesting that childhood physical

(F1,637 = 9.89; P,.005), histrionic (F1,637 = 8.66; P,.005), abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect play an important role

narcissistic (F1,637 = 9.74; P,.005), passive-aggressive in the onset of some PDs.

(F1,637 = 9.19; P,.005), schizotypal (F1,637 = 26.44; P,.005), These findings are also of interest because they are

and total PDs (F1,637 = 31.65; P,.005) after offspring age, consistent with prior findings1-12 indicating that pa-

parental education, parental psychiatric disorders, and tients with PDs are more likely than persons without PD

ARCH GEN PSYCHIATRY/ VOL 56, JULY 1999

603

©1999 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by Edilson Amorim on 11/25/2018

Table 3. Documented Childhood Neglect and Personality Table 4. Documented Childhood Abuse or Neglect and Risk

Disorder (PD) Symptoms* During Young Adulthood for Personality Disorders (PDs) During Young Adulthood

PD Criteria Prevalence of PD,

Among Those PD Criteria No. (%)

Not Abused Among Victims

or Neglected of Neglect Among Among

PD Symptoms (n = 608) (n = 23) F1,629† Those Victims

Not Abused of Abuse Adjusted

Paranoid 0.73 (0.89) 1.65 (1.47) 10.69‡ or Neglected or Neglect Odds Ratio

Schizoid 0.75 (0.87) 1.30 (1.10) 3.07 PD Diagnosis (n = 608) (n = 31) (95% CI)*

Schizotypal 0.95 (1.05) 1.87 (1.36) 7.60§

Any cluster A PD 2.43 (2.10) 4.83 (2.89) 12.87\¶ Paranoid 5 (0.8) 3 (9.7) 6.59 (1.20-36.03)

Antisocial 1.18 (1.11) 2.22 (1.88) 10.19‡\ Schizoid 6 (1.0) 1 (3.2) 0.84 (0.08-8.44)

Borderline 0.97 (1.15) 2.48 (1.86) 23.10\¶ Schizotypal 4 (0.7) 1 (3.2) 2.48 (0.22-28.23)

Histrionic 1.40 (1.21) 2.04 (1.55) 3.32 Any cluster 14 (2.3) 4 (12.9) 2.22 (0.59-8.27)

A PD

Narcissistic 0.86 (1.06) 2.00 (1.81) 12.05\¶

Antisocial 13 (2.1) 4 (12.9) 4.97† (1.33-18.49)

Any cluster B PD 4.41 (3.20) 8.74 (5.90) 22.10\¶

Borderline 7 (1.2) 4 (12.9) 7.73† (1.78-33.48)

Avoidant 0.72 (0.97) 1.52 (1.38) 9.48‡\

Histrionic 9 (1.5) 1 (3.2) 2.65 (0.28-25.06)

Dependent 1.04 (1.22) 2.26 (1.51) 14.62\¶

Narcissistic 2 (0.3) 3 (9.7) 18.21† (2.19-150.93)

Obsessive-compulsive 0.88 (0.88) 1.17 (1.03) 1.82

Any cluster 29 (4.8) 11 (35.5) 8.91† (3.53-22.62)

Any cluster C PD 2.63 (2.25) 4.96 (3.02) 15.51¶

B PD

Depressive 0.72 (1.04) 1.17 (1.56) 3.29

Avoidant 11 (1.8) 3 (9.7) 4.35 (1.00-18.92)

Passive-aggressive 0.82 (1.00) 1.83 (1.64) 15.69\¶

Dependent 12 (2.0) 3 (9.7) 6.35 (1.43-28.21)

Any PD 9.83 (6.45) 19.30 (11.08) 27.33¶

Obsessive- 4 (0.7) 0 (0.0) ...

compulsive

*Data are given as the mean (SD) number of DSM-IV PD criteria met at Any cluster 25 (4.1) 6 (19.4) 4.36† (1.50-12.63)

assessment interviews conducted during early adulthood. C PD

†Results of analyses of covariance, controlling for offspring age, parental

psychiatric disorders, and parental education. Depressive 7 (1.2) 2 (6.5) 7.19 (1.17-43.95)

‡P,.005. Passive- 10 (1.6) 4 (12.9) 5.54† (1.30-23.58)

§P,.01. aggressive

\Association remained statistically significant after controlling for Any appendix 17 (2.8) 6 (19.4) 6.83 (2.19-21.26)

co-occurring PD symptoms. B PD

¶P,.001. Any PD 69 (11.3) 17 (54.8) 6.38 (2.83-14.32)

to report histories of childhood maltreatment. Because *Controlling for age, parental education, and parental psychiatric

disorders. Odds ratios are considered statistically significant if the number

concerns have been raised17,18,23,24 that patients’ reports 1.0 falls outside the 95% confidence interval (CI). Ellipses indicate not

of childhood maltreatment may be due in part to biased computed.

memory or reporting, inferring from only retrospective †Association remained statistically significant after controlling for

findings that childhood maltreatment plays a role in the co-occurring PDs.

onset of PDs has been problematic. Our findings and pre-

vious longitudinal research25,26 indicate that the ten- logic role in PDs,18,42 childhood neglect has not played a

dency of many patients with PDs to report childhood mal- prominent role in etiologic theories. Nonetheless, the pres-

treatment is not merely an artifact of biased memory or ent findings and previous research indicating that child-

reporting. Childhood maltreatment is indeed much more hood neglect is associated with an increased risk for PDs,

likely to have occurred among young adults with PDs than attachment difficulties, antisocial behavior, and other in-

among young adults without PDs. terpersonal and psychological problems39,51-55 suggest that

Childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse, and ne- future theoretical work regarding the onset of PDs should

glect may also be associated with elevations in different examine the deleterious effects of childhood neglect.

types of PD symptoms. After symptoms of other PDs were Although the association between self-reported child-

accounted for, documented physical abuse was associ- hood maltreatment and PDs has received considerable in-

ated with elevated antisocial and depressive PD symp- vestigation, few hypotheses56,57 have been developed re-

toms, sexual abuse was associated with elevated border- garding the mechanisms of this association. Childhood

line PD symptoms, and neglect was associated with maltreatment may independently increase the risk for

elevated symptoms of antisocial, avoidant, borderline, nar- PDs; maladaptive parenting, rather than childhood mal-

cissistic, and passive-aggressive PDs. These findings, and treatment, may increase the risk for PDs; childhood

previous research9,25,46 indicating that childhood physi- maltreatment may increase the risk for PDs among per-

cal abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect may be differen- sons with biological diatheses for psychiatric disorders;

tially associated with PDs, suggest that it is important that and/or childhood maltreatment may be an indicator of pre-

researchers investigate specific etiologic models for each existing PDs. Childhood abuse and neglect may increase

of the different PDs. the risk for PDs independent of childhood and parental psy-

Although childhood neglect is more frequently re- chiatric disorders. Many questions about the association

ported than childhood physical or sexual abuse,47 more between childhood maltreatment and PDs will not be an-

research48-50 has investigated physical and sexual abuse swered definitively until further research is conducted.

than neglect. Thus, although childhood physical and Because the prevalence of specific PDs and specific

sexual abuse have been hypothesized to play an etio- types of documented childhood maltreatment was low,

ARCH GEN PSYCHIATRY/ VOL 56, JULY 1999

604

©1999 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by Edilson Amorim on 11/25/2018

40 Childhood

tigated whether childhood maltreatment predicted PD

Maltreatment symptoms after controlling for parental psychiatric dis-

Absent

35 Childhood orders. Diagnostic interviews were not administered to

Maltreatment

Present

the parents, however, and parental sociopathy was as-

30 sessed using a measure of parental trouble with the po-

lice, although the present findings were not affected when

Prevalence of PD, %

25 this item was not included in the analyses. In addition,

data regarding paternal education and psychiatric disor-

20 ders were obtained from the mothers, and data were not

available regarding interrater reliability.

15 Despite these limitations, our study has numerous

methodological strengths, including a representative

10 sample, a longitudinal design, the use of official records

of childhood abuse and neglect and retrospective self-

5 report data, the assessment of all DSM-IV PDs using data

from both offspring and their mothers, and the use of sta-

0 tistical procedures to control for offspring age and sex,

Cluster A Cluster B Cluster C Appendix B

Any PD difficult childhood temperament, parental education, and

40 parental psychiatric disorders. Thus, the present find-

ings contribute to an increased understanding of the as-

35 sociation between childhood maltreatment and early

adulthood PD symptoms.

30

Accepted for publication January 14, 1999.

Prevalence of PD, %

25

This study was supported by grant MH-36971 from

the National Institute of Mental Health, Rockville, Md

20

(Dr Cohen).

Corresponding author: Jeffrey G. Johnson, PhD, Box

15

60, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Dr,

New York, NY 10032.

10

5 REFERENCES

0

Cluster A Cluster B Cluster C Appendix B 1. Brodsky BS, Cloitre M, Dulit RA. Relationship of dissociation to self-mutilation

PD Clusters and childhood abuse in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;

152:1788-1792.

Overall (top) and unique (bottom) associations between documented 2. Goldman SJ, D’Angelo EJ, DeMaso DR, Mezzacappa E. Physical and sexual abuse

childhood maltreatment and risk for early adulthood personality disorders histories among children with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry.

(PDs). 1992;149:1723-1726.

3. Herman JL, Perry JC, van der Kolk BA. Childhood trauma in borderline person-

ality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:490-495.

it was necessary to investigate associations between docu- 4. Ogata SN, Silk KR, Goodrich S, Lohr NE, Westen D, Hill EM. Childhood sexual

mented childhood maltreatment and PD symptoms, rather and physical abuse in adult patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J

than PD diagnoses. There was sufficient power, how- Psychiatry. 1990;147:1008-1013.

ever, to permit investigation of the association between 5. Weaver TL, Clum GA. Early family environments and traumatic experiences as-

any documented childhood maltreatment and the risk for sociated with borderline personality disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:

1068-1075.

PDs during early adulthood. Furthermore, supplement- 6. Brown GR, Anderson B. Psychiatric morbidity in adult inpatients with childhood

ing documented evidence of childhood maltreatment with histories of sexual and physical abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:55-61.

self-reports of childhood abuse and neglect permitted in- 7. Paris J, Zweig-Frank H, Guzder J. Psychological risk factors for borderline per-

vestigation regarding unique associations between dif- sonality disorder in female patients. Compr Psychiatry. 1994;35:301-305.

8. Paris J, Zweig-Frank H, Guzder J. Risk factors for borderline personality disor-

ferent types of childhood maltreatment and different types der in male outpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1994;182:375-380.

of PD symptoms. 9. Norden KA, Klein DN, Donaldson SK, Pepper CM, Klein LM. Reports of the early

Because we conducted numerous statistical analy- home environment in DSM-III-R personality disorders. J Personal Disord. 1995;

ses, some significant associations may have been due to 9:213-223.

chance. Although numerous findings support the reli- 10. Shearer SL, Peters CP, Quaytman MS, Ogden RL. Frequency and correlates of

childhood sexual and physical abuse histories in adult female borderline inpa-

ability and validity of the items and algorithms used to tients. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:214-216.

assess PDs, it is possible that different findings would have 11. Raczek SW. Childhood abuse and personality disorders. J Personal Disord. 1992;

been obtained if a structured clinical interview such as 6:109-116.

the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV58 had been 12. Windle M, Windle RC, Scheidt DM, Miller GB. Physical and sexual abuse and

administered. Because a few PD diagnostic criteria were associated mental disorders among alcoholic inpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;

152:1322-1328.

not assessed, more statistically significant associations 13. Pribor EF, Dinwiddie SH. Psychiatric correlates of incest in childhood. Am J Psy-

might have been obtained if all PD criteria had been as- chiatry. 1992;149:52-56.

sessed. A strength of the present study is that we inves- 14. Silverman AB, Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM. The long-term sequelae of child and

ARCH GEN PSYCHIATRY/ VOL 56, JULY 1999

605

©1999 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by Edilson Amorim on 11/25/2018

adolescent abuse: a longitudinal community study. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;20: 37. Kasen S, Cohen P, Brook JS, Hartmark C. A multiple-risk interaction model: ef-

709-723. fects of temperament and divorce on psychiatric disorders in children. J Ab-

15. Kroll J. PTSD/Borderlines in Therapy. New York, NY: WW Norton & Co Inc; 1993. norm Child Psychol. 1996;24:121-150.

16. Herman J. Trauma and Recovery. New York, NY: Basic Books Inc Publishers; 38. Bernstein DP, Cohen P, Skodal A, Bezirganian S, Brook JS. Childhood anteced-

1992. ents of adolescent personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:907-913.

17. Maughan B, Rutter M. Retrospective reporting of childhood adversity: issues in 39. Brook JS, Whiteman M, Finch SJ, Cohen P. Young adult drug use and delin-

assessing long-term recall. J Personal Disord. 1997;11:19-33. quency: childhood antecedents and adolescent mediators. J Am Acad Child Ado-

18. Paris J. Childhood trauma as an etiological factor in the personality disorders. lesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:1584-1592.

J Personal Disord. 1997;11:34-49. 40. Brown J, Cohen P, Johnson JG, Salzinger S. A longitudinal analysis of risk fac-

19. Bifulco A, Brown GW, Lillie A, Jarvis J. Memories of childhood neglect and abuse: tors for child maltreatment: findings of a 17-year prospective study of officially

corroboration in a series of sisters. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38: recorded and self-reported child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22:

365-374. 1065-1078.

20. Brewin CR, Andrews B, Gotlib IH. Psychopathology and early experience: a re- 41. Johnson JG, Cohen P, Dohrenwend BP, Link BG, Brook JS. A longitudinal in-

appraisal of retrospective reports. Psychol Bull. 1993;113:82-98. vestigation of social causation and social selection processes involved in the as-

21. Herman JL, Schatzow E. Recovery and verification of memories of childhood sexual sociation between socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorders. J Abnorm

trauma. Psychoanal Psychol. 1987;4:11-14. Psychol. In press.

22. Robins LN, Schoenberg SP, Holmes SJ, Ratcliff KS, Benham A, Works J. Early 42. Laporte L, Guttman H. Traumatic childhood experiences as risk factors for bor-

home environment and retrospective recall: a test for concordance between sib- derline and other personality disorders. J Personal Disord. 1996;10:247-259.

lings with and without psychiatric disorders. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1985;55: 43. Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Gallagher PE, Kroll ME. Relationship of borderline symp-

27-41. toms to histories of abuse and neglect: a pilot study. Psychiatr Q. 1996;67:287-

23. Widom CS. Does violence beget violence? a critical examination of the litera- 295.

ture. Psychol Bull. 1989;106:3-28. 44. Steiger H, Jabalpurwala S, Champagne J. Axis II comorbidity and developmen-

24. Loftus EF. The reality of repressed memories. Am Psychol. 1993;48:518-537. tal adversity in bulimia nervosa. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1996;184:555-560.

25. Drake RE, Adler DA, Vaillant GE. Antecedents of personality disorders in a com- 45. Weine SM, Becker DF, Levy KN, Edell WS, McGlashan TH. Childhood trauma his-

munity sample of men. J Personal Disord. 1988;2:60-68. tories in adolescent inpatients. J Trauma Stress. 1997;10:291-298.

26. Luntz BK, Widom CS. Antisocial personality disorder in abused and neglected 46. Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Handelsman L. Predicting personality pathology among

children grown up. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:670-674. adult patients with substance use disorders: effects of childhood maltreatment.

27. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Addict Behav. 1998;23:855-868.

Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 47. National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect. Child Maltreatment, 1993. Wash-

1994. ington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1995.

28. Kogan LS, Smith J, Jenkins S. Ecological validity of indicator data as predictors 48. Ruegg R, Frances A. New research in personality disorders. J Personal Disord.

of survey findings. J Soc Serv Res. 1977;1:117-132. 1995;9:1-48.

29. Cohen P, Cohen J. Adolescent Life Values and Mental Health. Mahwah, NJ: 49. Wolock T, Horowitz B. Child maltreatment as a social problem: the neglect of

Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc Inc Publishers; 1996. neglect. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1984;15:223-238.

30. Costello EJ, Edelbrock CS, Duncan MK, Kalas R. Testing of the NIMH Diagnostic 50. Straus MA, Kinard EM, Williams LM. The neglect scale. Paper presented at: 4th

Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) in a Clinical Population: Final Report to International Conference on Family Violence Research; July 23, 1995; Durham,

the Center for Epidemiological Studies, National Institute of Mental Health. Pitts- NC.

burgh, Pa: University of Pittsburgh; 1984. 51. Dubo ED, Zanarini MC, Lewis RE, Williams AA. Childhood antecedents of self-

31. Hyler SE, Reider R, Williams JBW, Spitzer RL, Hendler J, Lyons M. The Person- destructiveness in borderline personality disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 1997;42:

ality Diagnostic Questionnaire: development and preliminary results. J Personal 63-69.

Disord. 1988;2:229-237. 52. Widom CS. The cycle of violence. Science. 1989;244:160-166.

32. Bernstein DP, Cohen P, Velez CN, Schwab-Stone M, Siever LJ, Shinsato L. Preva- 53. Gauthier L, Stollak G, Messé L, Aronoff J. Recall of childhood neglect and physi-

lence and stability of the DSM-III-R personality disorders in a community-based cal abuse as differential predictors of current psychological functioning. Child

survey of adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1237-1243. Abuse Negl. 1996;20:549-559.

33. Bird HR, Gould MS, Staghezza B. Aggregating data from multiple informants in 54. Robins LN. Deviant Children Grow Up: A Sociological and Psychiatric Study of

child psychiatry epidemiological research. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. Sociopathic Personality. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1966.

1992;31:78-85. 55. Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Basic Books Inc Pub-

34. Piacentini J, Cohen P, Cohen J. Combining discrepant diagnostic information lishers; 1982.

from multiple sources: are complex algorithms better than simple ones? J Ab- 56. van der Kolk BA, Fisler RE. Childhood abuse and neglect and loss of self-

norm Psychol. 1992;20:51-63. regulation. Bull Menninger Clin. 1994;58:145-168.

35. Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symp- 57. Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science.

tom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19: 1990;250:1678-1683.

1-15. 58. First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Benjamin L. Users Guide for the

36. Cohen P, Brook JS. Family factors related to the persistence of psychopathol- Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II).

ogy in childhood and adolescence. Psychiatry. 1987;50:332-345. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996.

ARCH GEN PSYCHIATRY/ VOL 56, JULY 1999

606

©1999 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by Edilson Amorim on 11/25/2018

You might also like

- Mscaa Practice Paper 1 Dec2017 1 1Document29 pagesMscaa Practice Paper 1 Dec2017 1 1Helen VlotomasNo ratings yet

- Child Maltreatment and Mental Health Problems in Adulthood Birth Cohort StudyDocument6 pagesChild Maltreatment and Mental Health Problems in Adulthood Birth Cohort Studyfotosiphone 8No ratings yet

- 3 PDFDocument7 pages3 PDFAltin CeveliNo ratings yet

- Reported Pathological ChildhoodDocument7 pagesReported Pathological ChildhoodMartha Lucía Triviño LuengasNo ratings yet

- Pedi 2019 33 425Document8 pagesPedi 2019 33 425Adisty DokiNo ratings yet

- Very Early Predictors of Adolescent Depression and Suicide Attempts in Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity DisorderDocument12 pagesVery Early Predictors of Adolescent Depression and Suicide Attempts in Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity DisorderhimeNo ratings yet

- The Role of Childhood Traumatization in The Development of Borderline Personality Disorder in HungaryDocument14 pagesThe Role of Childhood Traumatization in The Development of Borderline Personality Disorder in HungaryrahafNo ratings yet

- Mental HealthDocument7 pagesMental Healthcooperpaige34No ratings yet

- Prevalence and Correlate - PreadolescenceDocument10 pagesPrevalence and Correlate - PreadolescenceFlóra FarkasNo ratings yet

- BulliedDocument13 pagesBulliedBarry BurijonNo ratings yet

- Childhood Trauma and Children's Emerging Psychotic Symptoms: A Genetically Sensitive Longitudinal Cohort StudyDocument8 pagesChildhood Trauma and Children's Emerging Psychotic Symptoms: A Genetically Sensitive Longitudinal Cohort StudyVikramjit KhangooraNo ratings yet

- HodginsDocument6 pagesHodginsFrixos StephanidesNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument18 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptKc RiveraNo ratings yet

- Psychotic-Like Experiences in Offspring of Parents With Bipolar Disorder and Community ControlsDocument37 pagesPsychotic-Like Experiences in Offspring of Parents With Bipolar Disorder and Community ControlsandindlNo ratings yet

- Halusi JurnalDocument16 pagesHalusi JurnalVitta ChusmeywatiNo ratings yet

- NIH Public AccessDocument13 pagesNIH Public AccessJuan Alberto GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Pedophilia JAMA 2002 Review TherapyDocument8 pagesPedophilia JAMA 2002 Review TherapyW Andrés S MedinaNo ratings yet

- AlcoooDocument8 pagesAlcooofilimon ioanaNo ratings yet

- Pediatic Acuired Immunodeficiency SyndromeDocument6 pagesPediatic Acuired Immunodeficiency Syndromeahmad iffa maududyNo ratings yet

- Body Image and Risk Behaviors in Youth With HIVDocument6 pagesBody Image and Risk Behaviors in Youth With HIVMorrison Omokiniovo Jessa SnrNo ratings yet

- Child and Adolescent Maltreatment Patterns and Risk of Eating Disorder Behaviors Developing in Young AdulthoodDocument9 pagesChild and Adolescent Maltreatment Patterns and Risk of Eating Disorder Behaviors Developing in Young AdulthoodVivian BandeiraNo ratings yet

- Early Childhood Predictors of Boys' Antisocial and Violent Behavior in Early AdulthoodDocument15 pagesEarly Childhood Predictors of Boys' Antisocial and Violent Behavior in Early AdulthoodVictoria ZorzopulosNo ratings yet

- Bourget 2007Document9 pagesBourget 2007Kiara DattaNo ratings yet

- Paranoia RolDocument1 pageParanoia RolV.pavithraNo ratings yet

- Links Between Childhood Experiences andDocument16 pagesLinks Between Childhood Experiences andgica.bucicNo ratings yet

- Development of Bipolar Disorder and Other Comorbilities en TDAHDocument7 pagesDevelopment of Bipolar Disorder and Other Comorbilities en TDAHCarla NapoliNo ratings yet

- Poorer Subjective Mental Health Among Girls: Artefact or Real? Examining Whether Interpretations of What Shapes Mental Health Vary by SexDocument14 pagesPoorer Subjective Mental Health Among Girls: Artefact or Real? Examining Whether Interpretations of What Shapes Mental Health Vary by Sexsherifgamea911No ratings yet

- (2013) - ExnerDocument10 pages(2013) - Exnerbeatriz.l.oliveira.2300No ratings yet

- Marital Status Childhood Maltreatment Family DysfunctionDocument5 pagesMarital Status Childhood Maltreatment Family DysfunctionMaria Gracia AbadNo ratings yet

- Family Rejection As A Predictor of Negative Health Outcomes in White and Latino Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Young AdultsDocument9 pagesFamily Rejection As A Predictor of Negative Health Outcomes in White and Latino Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Young AdultsMuhammad Naufal FirdausNo ratings yet

- Childhood Bulling Involvement Predicts Low Grade Systemic InflammationDocument6 pagesChildhood Bulling Involvement Predicts Low Grade Systemic InflammationCristiana ComanNo ratings yet

- Running Head: MENTAL DISORDERS 1Document12 pagesRunning Head: MENTAL DISORDERS 1api-532509198No ratings yet

- Child and Adolescent Abuse and Neglect ResearchDocument9 pagesChild and Adolescent Abuse and Neglect ResearchKübraNo ratings yet

- Fruzzetti 2005 OptionalDocument24 pagesFruzzetti 2005 OptionalMacovei Anca0% (1)

- Infant Behavioral Inhibition Predicts Personality and Social Outcomes Three Decades LaterDocument8 pagesInfant Behavioral Inhibition Predicts Personality and Social Outcomes Three Decades LaterTaakeNo ratings yet

- Kendler-Childhood Parental Loss.1992Document8 pagesKendler-Childhood Parental Loss.1992Zsófia OtolticsNo ratings yet

- Family Characteristics and Behavior Problems of Suicidal and Non-Suicidal Children and AdolescentsDocument14 pagesFamily Characteristics and Behavior Problems of Suicidal and Non-Suicidal Children and AdolescentssaNo ratings yet

- 122 Full PDFDocument8 pages122 Full PDFcassieNo ratings yet

- Wood 1976Document8 pagesWood 1976Arif Erdem KöroğluNo ratings yet

- Duffy2013 PDFDocument8 pagesDuffy2013 PDFFelipe VergaraNo ratings yet

- Childhood Abuse, Neglect, and Household Dysfunction and The Risk ofDocument11 pagesChildhood Abuse, Neglect, and Household Dysfunction and The Risk ofDianaBNo ratings yet

- The Behavior of Anxious Parents Examining Mechanisms of Transmission of Anxiety From Parent To ChildDocument12 pagesThe Behavior of Anxious Parents Examining Mechanisms of Transmission of Anxiety From Parent To Child方科惠No ratings yet

- US National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study: Psychological Adjustment of 17-Year-Old AdolescentsDocument11 pagesUS National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study: Psychological Adjustment of 17-Year-Old AdolescentsGloria StahlNo ratings yet

- The Legacy of Child Maltreatment: Long-Term Health Consequences For WomenDocument6 pagesThe Legacy of Child Maltreatment: Long-Term Health Consequences For WomenRavennaNo ratings yet

- Young Children: Preventing Physical Abuse and Corporal Punishment (2014)Document7 pagesYoung Children: Preventing Physical Abuse and Corporal Punishment (2014)Children's InstituteNo ratings yet

- Adolescent DepressionDocument14 pagesAdolescent DepressionEduardo CañedoNo ratings yet

- Rates of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in YouthDocument9 pagesRates of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in YouthWilson Javier Dominguez PerezNo ratings yet

- Bullying Behaviors Among US Youth: Prevalence and Association With Psychosocial AdjustmentDocument13 pagesBullying Behaviors Among US Youth: Prevalence and Association With Psychosocial AdjustmentAna FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Quantitativo Bullying Maip PDFDocument13 pagesQuantitativo Bullying Maip PDFAna FerreiraNo ratings yet

- (696557968) Sifra JurnalDocument9 pages(696557968) Sifra JurnalSifra Turu AlloNo ratings yet

- Pedophilia and DSM-5: The Importance of Clearly Defining The Nature of A Pedophilic DisorderDocument4 pagesPedophilia and DSM-5: The Importance of Clearly Defining The Nature of A Pedophilic DisorderEmy Noviana SandyNo ratings yet

- Gri Zenko 1994Document11 pagesGri Zenko 1994Alex BoncuNo ratings yet

- Sills 2007Document10 pagesSills 2007hotorunNo ratings yet

- Risk of Mental Illness in Offspring of Parents With Schizophrenia, BipolarDocument11 pagesRisk of Mental Illness in Offspring of Parents With Schizophrenia, BipolarOkta BarraNo ratings yet

- Associations Between Four Types of Childhood Neglect and Personality Disorder Symptoms During Adolescence and Early Adulthood: Findings of A Community-Based Longitudinal StudyDocument17 pagesAssociations Between Four Types of Childhood Neglect and Personality Disorder Symptoms During Adolescence and Early Adulthood: Findings of A Community-Based Longitudinal StudyUmer FarooqNo ratings yet

- AmericanDocument13 pagesAmericanDavid QatamadzeNo ratings yet

- Lister, 2015Document7 pagesLister, 2015Bianca HlepcoNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument15 pagesNIH Public Access: Author Manuscriptyeremias setyawanNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors in Early Life For Developmental Coordination Disorder: A Scoping ReviewDocument9 pagesRisk Factors in Early Life For Developmental Coordination Disorder: A Scoping ReviewLaura RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Danckaerts2000 Article ANaturalHistoryOfHyperactivityDocument13 pagesDanckaerts2000 Article ANaturalHistoryOfHyperactivitymaksim6098No ratings yet

- Behind the Mask: Revealing the Risk Factors of Psychopathy in Children and AdolescentsFrom EverandBehind the Mask: Revealing the Risk Factors of Psychopathy in Children and AdolescentsNo ratings yet

- PharmacologyDocument141 pagesPharmacologyOmowunmi KadriNo ratings yet

- Endocrine Function Report Ncm114Document91 pagesEndocrine Function Report Ncm114abcde pwnjabiNo ratings yet

- Genetic Mutation and DisorderDocument31 pagesGenetic Mutation and Disorderabrielle dytucoNo ratings yet

- Disfagia Esofágica en Niños. Estado Del Arte y Propuesta para Un Enfoque Diagnóstico Basado en Los Síntomas (2022)Document12 pagesDisfagia Esofágica en Niños. Estado Del Arte y Propuesta para Un Enfoque Diagnóstico Basado en Los Síntomas (2022)7 MNTNo ratings yet

- DebateDocument12 pagesDebate•Kai yiii•No ratings yet

- CSB043 Prostate EBRT 2016 PCDocument53 pagesCSB043 Prostate EBRT 2016 PCPeter CaldwellNo ratings yet

- 3 Interview Transcripts From The Leaky Brain SummitDocument39 pages3 Interview Transcripts From The Leaky Brain SummitJimmy SchibelloNo ratings yet

- Stages of Acute Otitis MediaDocument1 pageStages of Acute Otitis MediaNicole Marie NicolasNo ratings yet

- Cancer WebquestDocument2 pagesCancer WebquestAmaia FiolNo ratings yet

- Overview of Viral MyositisDocument3 pagesOverview of Viral MyositisemirkurtalicNo ratings yet

- Substance-Related Disorders: Professor DR Sirwan K Ali Department of PsychiatryDocument43 pagesSubstance-Related Disorders: Professor DR Sirwan K Ali Department of PsychiatryAlan AhmadNo ratings yet

- Living With AdhdDocument3 pagesLiving With Adhdapi-704337450No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0300289621001745 mmc2Document2 pages1 s2.0 S0300289621001745 mmc2aris dwiprasetyaNo ratings yet

- GREGORY - Demencia Rápidamente ProgresivaDocument47 pagesGREGORY - Demencia Rápidamente ProgresivaUgalde López ReginaNo ratings yet

- ICD 10 CM Coding - DiabetesDocument68 pagesICD 10 CM Coding - Diabeteschaitanya varmaNo ratings yet

- Asco Treatment Summary and Survivorship Care PlanDocument2 pagesAsco Treatment Summary and Survivorship Care PlanFriska Permatasari NababanNo ratings yet

- 05 - 2022 ISI Short Term Application Form - EnglishDocument2 pages05 - 2022 ISI Short Term Application Form - EnglishPapitcha chittipornsanNo ratings yet

- Initation of Insulin - Final 2023Document27 pagesInitation of Insulin - Final 2023DEWI RIZKI AGUSTINANo ratings yet

- CATIE SaferSmoking CrystalMeth E 2020 FINAL WEBDocument2 pagesCATIE SaferSmoking CrystalMeth E 2020 FINAL WEBJeff PuglisiNo ratings yet

- The Accuracy of Fibroscan in A Real World StudyDocument2 pagesThe Accuracy of Fibroscan in A Real World StudyRaeni Dwi PutriNo ratings yet

- Juni 23 1Document105 pagesJuni 23 1Isabella MebangNo ratings yet

- Whipple Procedure: Procedure at A GlanceDocument4 pagesWhipple Procedure: Procedure at A GlanceAze Andrea PutraNo ratings yet

- نماذج باثو نظري هيكليDocument2 pagesنماذج باثو نظري هيكليWael EssaNo ratings yet

- OSCE Medicine by DR BilanDocument77 pagesOSCE Medicine by DR BilanBukhaari MohamedNo ratings yet

- M1 Post Task - Caparas-Bsn2a-A2Document2 pagesM1 Post Task - Caparas-Bsn2a-A2Gretta CaparasNo ratings yet

- Tatalaksana Primary Dan Secondary SurveyDocument26 pagesTatalaksana Primary Dan Secondary Surveyakun 31No ratings yet

- BMJ 22-09Document15 pagesBMJ 22-09Kiran ShahNo ratings yet

- DOLOCAN Dolocem CBD Eczema Cream White Paper - 20190917Document1 pageDOLOCAN Dolocem CBD Eczema Cream White Paper - 20190917Petra MitićNo ratings yet

- Homeopathic Heritage February Issue 2024Document94 pagesHomeopathic Heritage February Issue 2024Sumanta KamilaNo ratings yet