Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2 SE Noach

2 SE Noach

Uploaded by

Adrian CarpioOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2 SE Noach

2 SE Noach

Uploaded by

Adrian CarpioCopyright:

Available Formats

Sefat Emet on the Parsha

Noach

אא"ז מו"ר ז"ל הגיד בשם הרבנים כי תיבת נח הוא תיבות ואותיות התורה

כו' שיוכל כל אדם להכניס עצמו בכל תיבה מתורה ותפלה ועי"ז יוכל להנצל

ואיתא כל שהתיבה קולטתו כי בודאי צריך האדם להיות ראוי.מכל הסתר

לכנוס תוך דברי תורה אבל ע"י הביטול בכלל ישראל יוכל כל אדם להתדבק

) נח תרל’ד, (שפת אמת:בדברי תורה

My master, grandfather, and teacher of blessed memory [R. Yitzchak

Meir Alter] said in the name of other rabbis that the ark [teivah] of

Noah is [like] the words [teivot] and letters of the Torah, etc. [in that]

every person can bring themselves to every word of the Torah and

prayer. And in this way they may be saved from all hiddenness. And it

is brought [in Sanhedrin 108b] “All [animals] that the ark accepted

[were taken on board].” Surely a person must be worthy to enter into

the words of Torah, but through absorption into the collective of

Israel [klal yisrael], every person may cleave to the words of Torah.

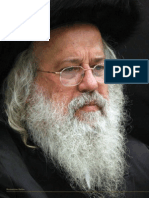

We begin this week’s study with a reference to the grandfather of the

Sefat Emet, Rabbi Yitzchak Meir Alter, also known as the Chidushei

HaRim. R. Yitzchak Meir Alter (1799-1866) was the founder of the

Gerrer dynasty of Hasidism, so named on account of his location in

Gur/Gora Kalwaria, Poland. Our rebbe, his grandson, R. Yehudah

Aryeh Leib Alter, was orphaned at the age of 8 and raised by his

grandparents. The Chidushei HaRim would be his primary teacher.

1|Sefat Emet on the Parshah

Rabbi Dr. Erin Leib Smokler

© Institute for Jewish Spirituality 2021

The Sefat Emet’s reverence for his grandfather and the deep

influence of his grandfather are evident throughout his work.

Let us begin with the verse from the Torah upon which the Rebbe

builds his commentary (though he does not mention it). Genesis 7:1

reads:

יתי צַ ִּדיק ְלפָּ נַי בַ דֹור

ִּ אֹּתָך ָּר ִּא

ְ יתָך אל הַ ֵּתבָּ ה כִּ י

ְ ֵּוַי ֹּאמר ה' ְלנֹּחַ ב ֹּא אַ ָּתה ְוכָּל ב

הַ זה

Then God said to Noah, “Go into the ark, with all your

household, for you alone have I found righteous before Me in

this generation.”

This verse stands in quiet contrast to the initial command to Noah to

build the ark, issued in the previous chapter: “ֲשׂה ְלָך ֵּתבַ ת עֲצֵּ י גֹּ פר

ֵּ ע,”

“Make yourself an ark of gopher wood” (Gen. 6:14).

Many hasidic commentators, beginning with the Baal Shem Tov,

found in the latter phrase, ““—”ב ֹּא… אל־הַ ֵּת ָּ ָ֑בהGo

ֹּֽ [lit. “come”] into...the

ark”—a unique invitation. God says to Noah, “Bo,” come to Me. After

Noah physically executes the enormous construction project of

building the ark, he is still outside of it. So God issues him an intimate

welcome. It is time to enter and begin the journey.

The hasidic tradition cited by the Sefat Emet, however, is not satisfied

with an invitation to a literal teivah (ark). It instead imagines a call

into a teivah of another, far more abstract sort, into the words (teivot)

and letters of the Torah. As the floodwaters rise around him, as the

chaos of the world threatens, Noah is summoned to enter into a

haven of divine language. Letters, as much as a physical ark, may

save him from drowning.

2|Sefat Emet on the Parshah

Rabbi Dr. Erin Leib Smokler

© Institute for Jewish Spirituality 2021

One might imagine this as an incantation, perhaps the original

“abracadabra” (arguably from the Aramaic: “I will create [abra] that

which I speak [ke’dabra]) moment. God swoops in because Noah

dutifully uttered magic words. But neither the Baal Shem Tov, nor

those who follow him, see the invitation to language in this simplistic

way. They also do not limit this exhortation to Noah alone.

The Sefat Emet says:

שיוכל כל אדם להכניס עצמו בכל תיבה מתורה ותפלה

[E]very person can bring themselves to every word of the Torah

and prayer.

The call to the teivah/ Word is a call to each and every one of us to

actively bring ourselves, even to forcefully insert ourselves, into the

words of our people—to locate ourselves within its frames; to see

ourselves in the stories we tell and the prayers we utter; to carry with

us our many gifts and burdens and to find space for it all on our

collective ark. Noah was charged to bring all of his baggage on

board—”יתָך אל הַ ֵּתבָּ ה

ְ ֵּ—” ב ֹּא אַ ָּתה ְוכָּל בand so are we. In the search for

safety, we ought to leave nothing behind. There is room for all of our

stuff within the ark of our people.

The reward for this audacious assertion is nothing short of revelation:

ועי"ז יוכל להנצל מכל הסתר

And in this way [we] may be saved from all hiddenness.

3|Sefat Emet on the Parshah

Rabbi Dr. Erin Leib Smokler

© Institute for Jewish Spirituality 2021

The Sefat Emet does not spell out precisely what is hidden and what

is revealed when we engage in the language game of our people with

courageous honesty and bold assertion. But he invokes a long

hasidic tradition of grappling with God’s seeming concealment

(hester). The Baal Shem Tov exhorted his followers to seek out God

specifically in places where God seems most absent: “ שם אלופו של

עולם מסתתר,” he suggested. “There”—mired in the muck of life which

seems so thoroughly devoid of divinity—“there the Master1 is hiding.”2

His great-grandson, Rebbe Nachman of Breslav (1772-1810),

extended this further:

ואפילו בהסתרה שבתוך ההסתרה בוודאי גם שם נמצא השם יתברך

Even in hiddenness within hiddenness, God can be found there.

(Likutei Moharan 1:56)

Sometimes God’s hiddenness is itself hidden, which would be true

exile. The mystical tradition urges us to resist the darkness of this

state. Rather, it is our job, through our language and through our

prayers, to experience and so know that even in what appears to be

hiddenness, God is merely hidden, and not beyond our reach.

Becoming aware of concealment can itself be its own kind of

revelation.

When we choose to climb aboard the ship, so to speak, to bring our

full selves into our spiritual awareness, at the very least, we might

become known to ourselves, it seems. At most, we might come to

1 The idiom “Cosmic Chieftain/Alufo shel olam” is used in Jewish mystical literature as an

appellation for God.

2

See Toldot Yaacov Yosef on Breishit 5 and 7.

4|Sefat Emet on the Parshah

Rabbi Dr. Erin Leib Smokler

© Institute for Jewish Spirituality 2021

know some truths of the sacred universe. And, like Noah, we might

find ourselves on solid ground even when all feels shaky beneath us.

This is no small feat, says the Sefat Emet. Surely one must be worthy

of Torah to truly find oneself in Torah, which may sound as if it

excludes some of us. Yet he closes by reminding us that an ark is not

discerning. It lifts up all that is placed upon it. So too can klal yisrael,

the collective of Israel, carry all who humble themselves to be a part.

Community can hold what individuals cannot.

As we seek refuge from flooding literal and figurative, may we be

blessed to find safety in words and in one another.

Personal Reflection

1. Where do you find yourself inside the stories or prayers of our

people? Where don’t you? When, how, why or why not?

2. Can you think of various ways to “insert” oneself into words or

letters? What are they? Have you, or can you imagine yourself,

doing so? When? What was that experience like? How might

you insert yourself into words that are not your own?

3. What gifts or burdens do you need to invite into your ark?

4. When has community helped you float?

For Practice

For the Baal Shem Tov, one way to “enter the word” is to connect

deeply and visually with the letters of the word. He would stare at the

letters until they shined (as in the passage we cited above). We can

think of it as a spiritual “staring contest”, where we hold our attention

steady in a focused manner on the letter(s) until they ‘blink” (as our

colleague Rabbi Nehemia Polen has framed it). The letter “comes

5|Sefat Emet on the Parshah

Rabbi Dr. Erin Leib Smokler

© Institute for Jewish Spirituality 2021

alive” in this manner, transformed to an “other” with whom we can

enter into relationship. It can now speak to us of its uniqueness,

inviting our uniqueness in response.

Let’s play with this. Consider the letter aleph:

א

Give your full attention to the letter. Hold the image fully in your sight,

taking in its fullness. Notice its parts, and how they are joined

together. Notice the black and notice the white surrounding it.

Without giving an answer, consider: which gives shape to which?

Allow the aleph to reach out to you, to say “here I am, see me in my

fullness”.

Now, we can play with some associations with the letter aleph. A

central one is that it is the first letter of the word אנכי/anokhi, “I am”,

the opening words of the Ten Commandments. It is a way of

representing the number one, and suggests the Oneness and

Uniqueness of God. It is the “one” before the “many” of Creation

(which begins with the second letter, ב/bet, of the word

בראשית/Bereshit, “In the beginning”).

Hold these associations in mind and go back to your visual

connection with the letter. Stay with it, and allow these other

associations to merge into what you see. What emerges for you as

you enter the aleph now?

6|Sefat Emet on the Parshah

Rabbi Dr. Erin Leib Smokler

© Institute for Jewish Spirituality 2021

R, Naftali of Ropshitz teaches that the three branches of the letter

aleph can be viewed as the figures of the human face. Imagine it like

this:

Take this association in, and connect it to the experience of the aleph

as a pointer toward the One.

Return to the original figure of the aleph. Hold it once again in your

visual field. Allow all of these associations to be present as you enter

into the letter aleph. Can it shine for you? Does it wink, to let you

know it feels seen? Can it open, as an Ark, to buoy you as you make

your way through the vicissitudes of life? Can it be a vehicle of

revelation, announcing God’s presence even in the material, the

worldly—even in other people?

7|Sefat Emet on the Parshah

Rabbi Dr. Erin Leib Smokler

© Institute for Jewish Spirituality 2021

You might also like

- Yitzchak Luria - Apples From The OrchardDocument767 pagesYitzchak Luria - Apples From The OrchardArturo Montiel100% (8)

- The Tabernacle of MosesDocument26 pagesThe Tabernacle of MosesAnonymous NW5yAwcImP100% (1)

- English Meshivat Nefesh PDFDocument375 pagesEnglish Meshivat Nefesh PDFhaggen90tckhotmail.comNo ratings yet

- Torat HaKabbalah-full-1Document75 pagesTorat HaKabbalah-full-1apramanau100% (3)

- Noam Elimelech Article MishpachaDocument2 pagesNoam Elimelech Article MishpachaYanki KingsleyNo ratings yet

- Chassidut VishnitzDocument17 pagesChassidut VishnitzCarina GhitaNo ratings yet

- Munkatch Ami Mag Sukkos 5776Document12 pagesMunkatch Ami Mag Sukkos 5776Hirshel Tzig100% (2)

- The Revelation of Messiah#1Document32 pagesThe Revelation of Messiah#1Ed Nydle100% (2)

- Noach Selections From Rabbi Baruch EpsteinDocument5 pagesNoach Selections From Rabbi Baruch EpsteinRabbi Benyomin HoffmanNo ratings yet

- From the Guardian's Vineyard on Sefer B'Reshith : (The Book of Genesis)From EverandFrom the Guardian's Vineyard on Sefer B'Reshith : (The Book of Genesis)No ratings yet

- Sukkot 5774 What Was Hillel Thinking (Final Copy)Document7 pagesSukkot 5774 What Was Hillel Thinking (Final Copy)DelyLyvyuNo ratings yet

- The Wisdom of Chanting The Hebrew Scriptures in Synagogue, Temple, and Congregational ServicesDocument54 pagesThe Wisdom of Chanting The Hebrew Scriptures in Synagogue, Temple, and Congregational ServicesCraig Peters67% (3)

- D'ei Chochmah L'nafshechah: "Let Your Soul Know Wisdom"Document20 pagesD'ei Chochmah L'nafshechah: "Let Your Soul Know Wisdom"api-26093179No ratings yet

- "How Awesome Is This Place!": Artscroll Chumash) Yet, Many English Translations of Our Phrase Do Not Use ThisDocument4 pages"How Awesome Is This Place!": Artscroll Chumash) Yet, Many English Translations of Our Phrase Do Not Use Thisoutdash2No ratings yet

- Torah 101-Tzav Parsha I. Answers To Study Questions (From Vayikra)Document7 pagesTorah 101-Tzav Parsha I. Answers To Study Questions (From Vayikra)api-204785694100% (1)

- From The Wellsprings Shavuos 5783 1 0Document10 pagesFrom The Wellsprings Shavuos 5783 1 0Yehosef ShapiroNo ratings yet

- A Ruach Qadim Excerpt Paul The MysticDocument15 pagesA Ruach Qadim Excerpt Paul The MysticDaniel Constantine100% (1)

- Hebrew ThinkingDocument13 pagesHebrew ThinkingHaSophim100% (15)

- Vayishlach 5775 - "But It Was Only A Fantasy"? (Pre-Mincha)Document11 pagesVayishlach 5775 - "But It Was Only A Fantasy"? (Pre-Mincha)Josh RosenfeldNo ratings yet

- Arameic Prayer of JesusDocument3 pagesArameic Prayer of JesusrashaxNo ratings yet

- The Akshaya Patra; Manasa Bhajare: Worship in the Mind: Volume One Book OneFrom EverandThe Akshaya Patra; Manasa Bhajare: Worship in the Mind: Volume One Book OneNo ratings yet

- Redigging The WellsDocument3 pagesRedigging The WellsEdward NydleNo ratings yet

- The Nature of ElohimDocument10 pagesThe Nature of ElohimcdmapleNo ratings yet

- Non-Kosher Animals & ToysDocument10 pagesNon-Kosher Animals & ToysRabbi Benyomin HoffmanNo ratings yet

- Divrey Yaakov by Rabbi Yaakov AddesDocument576 pagesDivrey Yaakov by Rabbi Yaakov Addessage718100% (1)

- Permissive or Causative Tense MistakesDocument23 pagesPermissive or Causative Tense Mistakesbukomeko joseohNo ratings yet

- The Akshaya Patra Series Manasa Bhajare: Worship in the Mind Part OneFrom EverandThe Akshaya Patra Series Manasa Bhajare: Worship in the Mind Part OneNo ratings yet

- Genesis in The Light of The New Testament-F W GrantDocument73 pagesGenesis in The Light of The New Testament-F W Grantcarlos sumarchNo ratings yet

- The Psalms: A Small Group Bible Study GuideDocument18 pagesThe Psalms: A Small Group Bible Study GuideDusan DukaNo ratings yet

- 1 SE BereshitDocument4 pages1 SE BereshitAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledoutdash2No ratings yet

- HaShem Is One-Volume-TwoDocument505 pagesHaShem Is One-Volume-TwoLeo Hanggi100% (1)

- The Secret of The Work of CreationDocument7 pagesThe Secret of The Work of CreationCoty DreyfusNo ratings yet

- Teshuvah and The Image of Elohim PDFDocument181 pagesTeshuvah and The Image of Elohim PDFAnonymous h8VHmcxczJ100% (2)

- Words: Matos-MaseiDocument2 pagesWords: Matos-Maseioutdash2No ratings yet

- Torah 101-Mishpatim Parsha I. Answers To Study Questions (Yitro)Document8 pagesTorah 101-Mishpatim Parsha I. Answers To Study Questions (Yitro)api-204785694No ratings yet

- "Binding To Purpose" 1 1: Part TwoDocument10 pages"Binding To Purpose" 1 1: Part TwoEd NydleNo ratings yet

- EcclesiastesDocument7 pagesEcclesiastesapi-216491724No ratings yet

- Psalm 55 ExegesisDocument25 pagesPsalm 55 ExegesisJohn Brodeur0% (1)

- The Lubavitcher Rebbe's Topsy-Turvy Sukkah: Rabbi Yosef BronsteinDocument5 pagesThe Lubavitcher Rebbe's Topsy-Turvy Sukkah: Rabbi Yosef Bronsteinoutdash2No ratings yet

- Introduction To Hebrew Healing LettersDocument11 pagesIntroduction To Hebrew Healing LettersKoop Da VilleNo ratings yet

- Ein Yaakov - Sanhedrin Perek Chelek PDFDocument13 pagesEin Yaakov - Sanhedrin Perek Chelek PDFBoat DrinXNo ratings yet

- Living Torah: Number 6: Eimah and YirahDocument2 pagesLiving Torah: Number 6: Eimah and YirahLivingTorahNo ratings yet

- Keter - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument6 pagesKeter - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaMinka Penelope Zadkiela HundertwasserNo ratings yet

- NightDocument23 pagesNightyapbengchuanNo ratings yet

- Abulafia TechDocument7 pagesAbulafia Techapramanau0% (1)

- Yeshivat Eretz Hatzvi: Insights Into Rosh Hashanah & Yom Kippur by The Faculty ofDocument48 pagesYeshivat Eretz Hatzvi: Insights Into Rosh Hashanah & Yom Kippur by The Faculty ofTodd BermanNo ratings yet

- Daf Ditty Eruvin 54: Healing The Broken Soul: Make Yourself A Desert WildernessDocument22 pagesDaf Ditty Eruvin 54: Healing The Broken Soul: Make Yourself A Desert WildernessJulian Ungar-SargonNo ratings yet

- Shemot תומש: GenesisDocument64 pagesShemot תומש: GenesisNapoleon FernandezNo ratings yet

- The Beginning of Wisdom 5782Document160 pagesThe Beginning of Wisdom 5782Ralph Arald Soldan100% (2)

- The Sepher Yetzirah of Rabbi Ben Clifford: The Magical Antiquarian Curiosity Shoppe, A Weiser Books CollectionFrom EverandThe Sepher Yetzirah of Rabbi Ben Clifford: The Magical Antiquarian Curiosity Shoppe, A Weiser Books CollectionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Commentary To Psalms 1 Thru 41 - Rev. John SchultzDocument211 pagesCommentary To Psalms 1 Thru 41 - Rev. John Schultz300rNo ratings yet

- What Is Midrash?: by Tzvi Freeman and Yehuda ShurpinDocument38 pagesWhat Is Midrash?: by Tzvi Freeman and Yehuda ShurpinVeronica AragónNo ratings yet

- Formas Literarias en Is 40-55Document14 pagesFormas Literarias en Is 40-55francisco giuffridaNo ratings yet

- 01 Tehillim 1-72Document220 pages01 Tehillim 1-72zvxngntnrkNo ratings yet

- PRONOUNCEDASITISWRITTENDocument12 pagesPRONOUNCEDASITISWRITTENCadena CadenaNo ratings yet

- Silence and Words in Zen Buddhism (1995)Document21 pagesSilence and Words in Zen Buddhism (1995)CartaphilusNo ratings yet

- PRONOUNCEDASITISWRITTENDocument11 pagesPRONOUNCEDASITISWRITTENSamuelNo ratings yet

- 53 Arizal Parsha VeZot Haberachah PDFDocument13 pages53 Arizal Parsha VeZot Haberachah PDFCesar Dos Anjos100% (1)

- 2 - Hassidut God Is Everywhere 2 Tanya 1Document3 pages2 - Hassidut God Is Everywhere 2 Tanya 1Todd BermanNo ratings yet

- A Beacon in The NightDocument4 pagesA Beacon in The Nightoutdash2No ratings yet

- Eli BrodyDocument3 pagesEli BrodyAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- Kabbalat Shabbat Prayer Book 10.18.15 Final For EchaiDocument51 pagesKabbalat Shabbat Prayer Book 10.18.15 Final For EchaiAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- Art of Jewish Prayer SampleDocument36 pagesArt of Jewish Prayer SampleAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- Gnome Level 2 BardDocument4 pagesGnome Level 2 BardAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- Sample Do Now Sheet EdutopiaDocument1 pageSample Do Now Sheet EdutopiaAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- Kangee Crow SeasonedDocument2 pagesKangee Crow SeasonedAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- Welcome Letter To WH2 Parents 1920Document1 pageWelcome Letter To WH2 Parents 1920Adrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- 02 Luis CantilloDocument2 pages02 Luis CantilloAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- Cheat SheetDocument16 pagesCheat SheetAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- Conan Character CONAN 4Document3 pagesConan Character CONAN 4Adrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- TOR House RulesDocument4 pagesTOR House RulesAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- Notes From - Letters To A Fellow Seeker - A Short Introduction To The Quaker WayDocument2 pagesNotes From - Letters To A Fellow Seeker - A Short Introduction To The Quaker WayAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- Notes From - Mormonism, What Everyone Needs To Know ®GDocument40 pagesNotes From - Mormonism, What Everyone Needs To Know ®GAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- Jewish LiteratureDocument1 pageJewish LiteratureAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- 27 SE TazriaDocument4 pages27 SE TazriaAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- Jaffe L3 R3 NiggunDocument1 pageJaffe L3 R3 NiggunAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- Halfling 1Document1 pageHalfling 1Adrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- 33 SE BechukotaiDocument5 pages33 SE BechukotaiAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- 14 SE Va'eraDocument7 pages14 SE Va'eraAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- Hazir's BackstoryDocument2 pagesHazir's BackstoryAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- 8 SE VaYishlachDocument8 pages8 SE VaYishlachAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- Moduel 4 Day 1 HitbodedutDocument3 pagesModuel 4 Day 1 HitbodedutAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- 1 SE BereshitDocument4 pages1 SE BereshitAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- 11th Grade U.S. History NGSSS-SS Pacing Guide 1st 9 WeeksDocument21 pages11th Grade U.S. History NGSSS-SS Pacing Guide 1st 9 WeeksAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- ZND Spirit Sheet (Double) (From Fillable)Document1 pageZND Spirit Sheet (Double) (From Fillable)Adrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- Stages of HolocaustDocument38 pagesStages of HolocaustAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- 39 SE ChukatDocument6 pages39 SE ChukatAdrian CarpioNo ratings yet

- Kol Isha SourcesDocument4 pagesKol Isha Sourcesdoggydog613No ratings yet

- Lesson 02 - Noahide HistoryDocument15 pagesLesson 02 - Noahide HistoryMilan KokowiczNo ratings yet

- Zealots: SicariiDocument4 pagesZealots: SicariiSolayman IslamNo ratings yet

- History of Jewish Law and Ritual - Syllabus UC Berkeley Spring 2023Document13 pagesHistory of Jewish Law and Ritual - Syllabus UC Berkeley Spring 2023spagnoloachtNo ratings yet

- Relax: Avraham FriedDocument4 pagesRelax: Avraham Friedישראל ישראליNo ratings yet

- Haredi JudaismDocument34 pagesHaredi JudaismBogdan SoptereanNo ratings yet

- High Holidays 2023 BDocument6 pagesHigh Holidays 2023 BshasdafNo ratings yet

- Nitzavim VayelechDocument4 pagesNitzavim VayelechelietouboulNo ratings yet

- Famous RabiesDocument137 pagesFamous RabiesDavid Saportas LièvanoNo ratings yet

- Chagigah 3Document86 pagesChagigah 3Julian Ungar-SargonNo ratings yet

- Eruv ArticleDocument23 pagesEruv ArticleJames Wolfe100% (1)

- Mishpacha Satmar Matzoh BakeryDocument10 pagesMishpacha Satmar Matzoh Bakeryדער בלאטNo ratings yet

- Zrd1 - Chabad Lubavitch Hospitality Center Eshel Hachnosas Orchim Inc-Mendel Hendel-274 Kingston AveDocument6 pagesZrd1 - Chabad Lubavitch Hospitality Center Eshel Hachnosas Orchim Inc-Mendel Hendel-274 Kingston AvechleaksNo ratings yet

- Machzor Rosh Hashanah Sefard - en - Sefaria Community TranslationDocument7 pagesMachzor Rosh Hashanah Sefard - en - Sefaria Community TranslationMario ReyNo ratings yet

- Calendar of Jewish Festivals and Fasts 2019 2024Document2 pagesCalendar of Jewish Festivals and Fasts 2019 2024limirim :No ratings yet

- Sea of Wisdom Shelach Behaloschah 5783Document4 pagesSea of Wisdom Shelach Behaloschah 5783Yehosef ShapiroNo ratings yet

- IWRBSDocument9 pagesIWRBSBernadetteNo ratings yet

- Assignment On JudaismDocument10 pagesAssignment On JudaismfarhanNo ratings yet

- Current Relevant: Presenting The Rebbe's Call To Adopt A Mashiach MindsetDocument20 pagesCurrent Relevant: Presenting The Rebbe's Call To Adopt A Mashiach MindsetBlessworkNo ratings yet

- JudaismDocument20 pagesJudaismPrincess kc DocotNo ratings yet

- Living Jewish Shelach 793Document4 pagesLiving Jewish Shelach 793Danijel DavarNo ratings yet

- Judaism The Covenant PracticesDocument4 pagesJudaism The Covenant PracticesRaymond Jamito,No ratings yet

- Chagigah 17Document74 pagesChagigah 17Julian Ungar-SargonNo ratings yet

- Yom Kippur GuideDocument10 pagesYom Kippur GuideTwo Chassids In a PodNo ratings yet

- Cocoa Distillate Natural KosherDocument1 pageCocoa Distillate Natural KosherSandieNo ratings yet

- TaysirDocument13 pagesTaysirMamadou aliou DialloNo ratings yet

- Chabad Kept Refusing RubashkinDocument6 pagesChabad Kept Refusing RubashkinyylbNo ratings yet