Professional Documents

Culture Documents

International Finance Theory and Policy 10th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual

International Finance Theory and Policy 10th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual

Uploaded by

khucly5cstOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

International Finance Theory and Policy 10th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual

International Finance Theory and Policy 10th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual

Uploaded by

khucly5cstCopyright:

Available Formats

International Finance Theory And

Policy 10th Edition Krugman Solutions

Manual

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://testbankdeal.com/dow

nload/international-finance-theory-and-policy-10th-edition-krugman-solutions-manual/

Chapter 7

External Economies of Scale

and the International Location

of Production

◼ Chapter Organization

Economies of Scale and International Trade: An Overview

Economies of Scale and Market Structure

The Theory of External Economies

Specialized Suppliers

Labor Market Pooling

Knowledge Spillovers

External Economies and Market Equilibrium

External Economies and International Trade

External Economies, Output, and Prices

External Economies and the Pattern of Trade

Box: Holding the World Together

Trade and Welfare with External Economies

Dynamic Increasing Returns

Interregional Trade and Economic Geography

Box: Tinseltown Economics

Summary

◼ Chapter Overview

In previous chapters, trade between nations was motivated by their differences in factor productivity or

relative factor endowments. The type of trade that occurred, for example of food for manufactures, is

based on comparative advantage and is called interindustry trade. This chapter introduces trade based on

economies of scale in production. Such trade in similar productions is called intraindustry trade and

describes, for example, the trading of one type of manufactured good for another type of manufactured

good. It is shown that trade can occur when there are no technological or endowment differences but when

there are economies of scale or increasing returns in production, as opposed to the constant returns to scale

assumed in previous chapters.

Economies of scale can either take the form of (1) external economies, whereby the cost per unit depends

on the size of the industry but not necessarily on the size of the firm; or as (2) internal economies, whereby

© 2015 Pearson Education, Inc.

34 Krugman/Obstfeld/Melitz • International Economics: Theory & Policy, Tenth Edition

the production cost per unit of output depends on the size of the individual firm but not necessarily on the

size of the industry. Internal economies of scale give rise to imperfectly competitive markets, unlike the

perfectly competitive market structures that were assumed to exist in earlier chapters. Industries

characterized by purely external economies of scale will typically consist of many small firms and be

perfectly competitive. The focus of this chapter is on external economies, while the next chapter looks at

internal economies.

External economies of scale (EES) lead to a clustering of firms in one location for three main reasons:

1. Specialized suppliers: By locating next to firms in the same industry, you are able to specialize in one

aspect of the production process and outsource other stages of production to neighboring firms.

2. Labor market pooling: Firms with specific skill needs will prefer to locate near a large pool of workers

with those skills to limit labor market shortages. At the same time, skilled workers prefer to locate close

to the firms that hire them to limit unemployment.

3. Knowledge spillovers: Having similar firms located next to one another can lead to increased sharing

of ideas and partnerships.

Market equilibrium in an EES industry is determined by the intersection of market demand and supply

as in the constant returns case. The key difference here is that the market supply curve is forward falling,

reflecting the fact that average costs in the industry actually fall as industry production (i.e., size) rises. This

distinction drives trade in this model. When two countries trade, it makes sense to concentrate production

in one country because this will lead to lower average costs than splitting production across two countries.

With trade, the country with the lower average cost will export the good. This will lead to more production

in the exporting country and less production in the importing country. As the industry is characterized by

EES, this will cause costs in the exporting country to fall and costs to rise in the importing country.

Eventually, all production will locate in the exporting country at a lower market price than would have

prevailed without trade.

The pattern of trade is only partially explained by comparative advantage. Rather, it may be a historical

accident that led to the formation of an industry in a particular location. The chapter gives the example of

why global button manufacturing is concentrated in one town in China, mostly because one firm in the 1980s

began producing buttons there. That the location of production is not entirely dependent on comparative

advantage presents situations in which trade can actually make a country worse off. For example, if button

production is already established in China, then Chinese button producers have an advantage over firms in

countries without an established button industry (due to external economies of scale in the button industry).

Without trade, the button industry in a low-wage country could develop to the point where it is actually

producing at a scale such that the price of buttons is lower than the world price established by the Chinese

button industry. This suggests that a country could actually make itself better off by closing off from trade

to let external economies of scale industries develop, assuming that the country has a large enough market

to support an efficient scale of production. However, these cases may be difficult to identify, and

protectionism can lead to unintended consequences such as retaliatory tariffs.

External economies may also be the result of learning curves (dynamic increasing returns). In this scenario,

the unit cost of production falls as the cumulative output of an industry rises. Industries that have been around

for a long time are further out on their learning curves and will have an advantage over new industries that

still have to undergo the process of “learning by doing.” The presence of these learning curves may justify

infant industry tariff protection, as a new industry in a country could potentially be competitive but needs

to be protected until it develops the acquired knowledge of established global competitors. On the other

hand, it may be difficult to identify such situations, and tariff protection presents several problems, which

will be discussed in later chapters (notably rent-seeking behavior by protected firms).

© 2015 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7 External Economies of Scale and the International Location of Production 35

◼ Answers to Textbook Problems

1. Cases a and d represent external economies of scale as industry production is concentrated in a just a

few locations. The benefits of geographical clustering include a greater variety of specialized services

to support industry operations, access to a larger pool of specialized labor, and thicker input markets.

Cases b and c represent internal economies of scale because a single firm/plant is producing the

output for the whole industry. As the output of a single firm increases, average costs will fall. This

can lead to imperfect competition as it supports a limited number of firms in an industry.

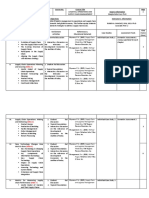

2. This view is flawed in the sense that countries produce more than one good. Trade allows a country to

free up resources from a relatively less efficient industry and expand production in industries with more

efficient production. With increasing returns, this expansion of production will drive down costs.

There may be a case made for external economies leading to losses from trade, however. Consider

the diagram above. Country A is an established producer and produces at quantity QA and price PA. If

country B were to enter into the industry, its initial startup cost would be at CB. Because this is greater

than PA, country B will import this good. However, if country B were to be closed off from trade, then

production would be at QB and price would be PB. Thus, trade actually represents a situation worse than

autarky for country B and protection may be warranted. However, actually identifying these situations

is difficult, and protection may lead to unintended consequences (such as retaliatory tariffs).

3. Dynamic increasing returns occur whenever average costs fall with cumulative output. In other words, a

learning curve exists that favors established producers over startups. This is an open-ended question,

though the examples in Question 9 provide some ideas. Two industries characterized by dynamic

increasing returns are biotechnology and aircraft design. Biotechnology is an industry in which

innovation fuels new products, but it is also one where learning how to successfully take an idea and

create a profitable product is a skill set that may require some practice. Aircraft design requires

innovations to create new planes that are safer or more cost efficient, but it is also an industry where

new planes are often subtle alterations of previous models and where detailed experience with one

model may be a huge help in creating a new one.

4. a. The relatively few locations for production suggest external economies of scale in production.

If these operations are large, there may also be large internal economies of scale in production.

b. Because economies of scale are significant in airplane production, it tends to be done by a small

number of (imperfectly competitive) firms at a limited number of locations. One such location is

Seattle, where Boeing produces airplanes.

© 2015 Pearson Education, Inc.

36 Krugman/Obstfeld/Melitz • International Economics: Theory & Policy, Tenth Edition

c. Because external economies of scale are significant in semiconductor production, semiconductor

industries tend to be concentrated in certain geographic locations. If, for some historical reason, a

semiconductor is established in a specific location, the export of semiconductors by that country is

due to economies of scale and not comparative advantage.

d. “True” scotch whiskey can only come from Scotland. The production of scotch whiskey requires

a technique known to skilled distillers who are concentrated in the region. This labor market

pooling suggests external economies of scale. Also, soil and climactic conditions are favorable

for grains used in local scotch production. This reflects comparative advantage.

e. France has a particular blend of climactic conditions and land that is difficult to reproduce

elsewhere. This generates a comparative advantage in wine production.

5. a. Both countries have identical forward-falling supply curves, so the pattern of production will

depend entirely on which country establishes its industry first. The country that moves first will

have a cost advantage over the other country because it is producing a larger quantity of the

good. That country will produce the entire output of the good and export to the second country.

b. Both countries benefit from international trade in this case as the price of the good will be lower

when one country produces the entire output as compared to both countries producing half of the

output. The only way that the importing country would not benefit from trade is if it were a much

more efficient producer than the exporting country (but due to increasing returns, cannot compete

with an established industry). However, both countries have the same supply curve, so they both

gain from trade.

6. The three forces driving external economies of scale are access to specialized suppliers, labor market

pooling, and knowledge spillovers. As these forces weaken, so too do the cost advantages of geographic

clustering. The location of production becomes increasingly driven by factor costs when industries

move away from external economies of scale toward traditional constant returns to scale.

7. Even with higher wages in China, the external economies of scale industries located in China may not

move to lower-wage countries. Consider Figure 7-4 in the text. China’s average cost curve lies above

Vietnam’s reflecting higher wages in China. However, the fact that Chinese industry is established gives

it a cost advantage over any Vietnamese firms who would enter into the industry and face an initial cost

higher than the established Chinese firms. Production would only shift to Vietnam if China’s average

cost curve were to shift up enough so that the new equilibrium price and cost in China lies above the

startup cost in Vietnam.

8. Consider again two different scenarios: In scenario 1, there are two firms in the same location and a

local labor supply of 200 for both firms. In scenario 2, the two firms are far apart, and each firm has

a local labor supply of 100. Now suppose that both firms are expanding, increasing their demand

for labor up to 150 each. In the first case, each firm will face a local labor shortage of 50 workers

(assuming each firm is able to hire 100 workers). In the second case, each firm will experience the

same local labor shortage of 50 workers! Thus, locating next to each other does not present any

disadvantages over locating far apart when both firms are expanding. There still is, however, an

advantage when one firm is expanding and the other is contracting.

9. a. External economies of scale are likely due to the need to have a common pool of labor with

technical skills. Dynamic increasing returns may be likely due to the need for continual

innovation and learning.

b. External economies are unlikely because it is difficult to see how the costs of a single firm would

fall if other firms are present in the asphalt industry. Dynamic increasing returns are also unlikely

as the asphalt industry is pretty well established and learning curves are likely to be low.

© 2015 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7 External Economies of Scale and the International Location of Production 37

c. External economies are highly likely because having a great number of support firms and an

available pool of skilled labor in filmmaking are critical to film production. Dynamic returns

are also likely because filmmaking is an industry in which learning is important.

d. External economies are somewhat likely in that it may be advantageous to have other researchers

nearby. Dynamic returns are highly likely because such research builds on itself through a learning-

by-doing process.

e. External economies are somewhat likely if there are a set of skills unique to the timber industry

that would lead to a clustering of timber firms and timber workers. Dynamic returns are unlikely

as the technology used in timber harvesting is relatively stable (i.e., a low learning curve).

© 2015 Pearson Education, Inc.

You might also like

- International Economics 6th Edition James Gerber Test BankDocument12 pagesInternational Economics 6th Edition James Gerber Test Bankalanfideliaabxk100% (35)

- International Management Culture Strategy and Behavior 9th Edition Luthans Test BankDocument62 pagesInternational Management Culture Strategy and Behavior 9th Edition Luthans Test Bankkhucly5cst100% (29)

- International Economics 17th Edition Carbaugh Solutions ManualDocument3 pagesInternational Economics 17th Edition Carbaugh Solutions Manualkhucly5cst100% (30)

- Illustrated Course Guide Microsoft Office 365 and Access 2016 Intermediate Spiral Bound Version 1st Edition Friedrichsen Solutions ManualDocument10 pagesIllustrated Course Guide Microsoft Office 365 and Access 2016 Intermediate Spiral Bound Version 1st Edition Friedrichsen Solutions Manualfizzexponeo04xv0100% (26)

- Discovering Computers Essentials 2018 Digital Technology Data and Devices 1st Edition Vermaat Test BankDocument22 pagesDiscovering Computers Essentials 2018 Digital Technology Data and Devices 1st Edition Vermaat Test Banklovellednayr98497% (39)

- International Financial Management 12th Edition Jeff Madura Solutions ManualDocument26 pagesInternational Financial Management 12th Edition Jeff Madura Solutions ManualMichaelSmithspqn100% (62)

- International Economics Theory and Policy 10th Edition Krugman Solutions ManualDocument7 pagesInternational Economics Theory and Policy 10th Edition Krugman Solutions Manualkhucly5cst100% (19)

- International Economics Theory and Policy 11th Edition Krugman Solutions ManualDocument9 pagesInternational Economics Theory and Policy 11th Edition Krugman Solutions Manualbewet.vesico1l16100% (21)

- International Financial Management 13th Edition Madura Test BankDocument30 pagesInternational Financial Management 13th Edition Madura Test Bankaprilhillwoijndycsf100% (33)

- International Financial Management 12th Edition Jeff Madura Test BankDocument13 pagesInternational Financial Management 12th Edition Jeff Madura Test Bankscathreddour.ovzp100% (26)

- International Financial Management 8th Edition Madura Solutions ManualDocument8 pagesInternational Financial Management 8th Edition Madura Solutions Manualkhucly5cst100% (28)

- International Finance Global 6th Edition Eun Test BankDocument71 pagesInternational Finance Global 6th Edition Eun Test Bankjethrodavide6qi100% (34)

- International Financial Management 8th Edition Madura Test BankDocument40 pagesInternational Financial Management 8th Edition Madura Test Bankvioletciara4zr6100% (37)

- International Economics 9th Edition Appleyard Test BankDocument25 pagesInternational Economics 9th Edition Appleyard Test BankMckenzieSmithymcqxwai100% (58)

- International Financial Management 11th Edition Madura Test BankDocument25 pagesInternational Financial Management 11th Edition Madura Test BankMckenzieSmithymcqxwai100% (55)

- Contemporary Nutrition 9th Edition Wardlaw Solutions ManualDocument21 pagesContemporary Nutrition 9th Edition Wardlaw Solutions Manualphenicboxironicu9100% (39)

- International Economics 7th Edition Gerber Test BankDocument26 pagesInternational Economics 7th Edition Gerber Test Bankclitusarielbeehax100% (33)

- Econ Microeconomics 4 4th Edition Mceachern Test BankDocument60 pagesEcon Microeconomics 4 4th Edition Mceachern Test Bankotisfarrerfjh2100% (34)

- Contemporary Nutrition 8th Edition Wardlaw Test BankDocument25 pagesContemporary Nutrition 8th Edition Wardlaw Test Bankalanholt09011983rta100% (37)

- International Finance Global 6th Edition Eun Test BankDocument25 pagesInternational Finance Global 6th Edition Eun Test BankMichelleBrownfxmk100% (61)

- Lifetime Physical Fitness and Wellness A Personalized Program 14th Edition Hoeger Solutions ManualDocument16 pagesLifetime Physical Fitness and Wellness A Personalized Program 14th Edition Hoeger Solutions Manualkhuongdiamond6h5100% (29)

- Economics 12th Edition Arnold Solutions ManualDocument18 pagesEconomics 12th Edition Arnold Solutions Manuallaurasheppardxntfyejmsr100% (37)

- Econ Micro Canadian 1st Edition Mceachern Solutions ManualDocument7 pagesEcon Micro Canadian 1st Edition Mceachern Solutions Manualheulwenfidelma2dg5100% (34)

- E Commerce Essentials 1st Edition Laudon Test BankDocument18 pagesE Commerce Essentials 1st Edition Laudon Test Bankraphaelbacrqu100% (31)

- Accounting Information Systems Controls Processes 3rd Edition Turner Solutions ManualDocument27 pagesAccounting Information Systems Controls Processes 3rd Edition Turner Solutions Manualmrsamandareynoldsiktzboqwad100% (32)

- Contemporary Nursing Issues Trends and Management 7th Edition Cherry Test BankDocument9 pagesContemporary Nursing Issues Trends and Management 7th Edition Cherry Test Bankdoijethrochsszo100% (27)

- Essentials of Business Statistics Communicating With Numbers 1st Edition Jaggia Solutions ManualDocument26 pagesEssentials of Business Statistics Communicating With Numbers 1st Edition Jaggia Solutions Manualfelixedanafte5n100% (36)

- Microeconomics Canadian 1st Edition Bernheim Test BankDocument29 pagesMicroeconomics Canadian 1st Edition Bernheim Test Bankmagnusngah7aaz100% (31)

- Business Law With Ucc Applications 14th Edition Sukys Solutions ManualDocument17 pagesBusiness Law With Ucc Applications 14th Edition Sukys Solutions Manualfarleykhanhh7n100% (40)

- International Financial Management Canadian Canadian 3rd Edition Brean Solutions ManualDocument15 pagesInternational Financial Management Canadian Canadian 3rd Edition Brean Solutions Manualscathreddour.ovzp100% (29)

- Derivatives Markets 3rd Edition Mcdonald Test BankDocument6 pagesDerivatives Markets 3rd Edition Mcdonald Test Bankjamesreedycemzqadtp100% (26)

- Human Development and Performance Throughout The Lifespan 2nd Edition Cronin Solutions ManualDocument3 pagesHuman Development and Performance Throughout The Lifespan 2nd Edition Cronin Solutions Manualstacyperezbrstzpmgif100% (36)

- International Marketing An Asia Pacific Perspective 6th Edition Richard Solutions ManualDocument17 pagesInternational Marketing An Asia Pacific Perspective 6th Edition Richard Solutions Manualbewet.vesico1l16100% (28)

- Econ Macro 5th Edition Mceachern Solutions ManualDocument4 pagesEcon Macro 5th Edition Mceachern Solutions Manualraphaelbacrqu100% (36)

- International Financial Management Canadian Perspectives 2nd Edition Eun Test BankDocument24 pagesInternational Financial Management Canadian Perspectives 2nd Edition Eun Test Bankvioletciara4zr6100% (33)

- Business Ethics Now 5th Edition Ghillyer Test BankDocument63 pagesBusiness Ethics Now 5th Edition Ghillyer Test Bankkennethhue1tp64c100% (34)

- Full Download International Marketing 16th Edition Cateora Solutions ManualDocument28 pagesFull Download International Marketing 16th Edition Cateora Solutions Manualjamesburnsbvp100% (38)

- Global Business Today Canadian 4th Edition Hill Test BankDocument31 pagesGlobal Business Today Canadian 4th Edition Hill Test Bankcovinoustomrig23vdx100% (27)

- Give Me Liberty An American History 5th Edition Foner Test BankDocument23 pagesGive Me Liberty An American History 5th Edition Foner Test Banktammywilkinspwsoymeibn100% (30)

- Business Intelligence and Analytics Systems For Decision Support 10th Edition Sharda Test BankDocument13 pagesBusiness Intelligence and Analytics Systems For Decision Support 10th Edition Sharda Test Banknooningpeacockrkf100% (33)

- Contemporary Marketing Update 2015 16th Edition Boone Test BankDocument25 pagesContemporary Marketing Update 2015 16th Edition Boone Test BankKimberlyWilliamsonepda100% (62)

- Essentials of Modern Business Statistics With Microsoft Office Excel 7th Edition Anderson Test BankDocument45 pagesEssentials of Modern Business Statistics With Microsoft Office Excel 7th Edition Anderson Test Bankhanhgloria0hge5100% (31)

- Employment Law For Business 7th Edition Bennett Alexander Test BankDocument19 pagesEmployment Law For Business 7th Edition Bennett Alexander Test Bankkieranthang03m100% (37)

- International Economics Theory and Policy 10th Edition Krugman Test BankDocument26 pagesInternational Economics Theory and Policy 10th Edition Krugman Test BankMatthewRosarioksdf100% (57)

- International Financial Reporting Standards An Introduction 2nd Edition Needles Solutions ManualDocument26 pagesInternational Financial Reporting Standards An Introduction 2nd Edition Needles Solutions ManualMichaelHughesafdmb100% (59)

- Ethics and Issues in Contemporary Nursing Canadian 3rd Edition Burkhardt Test BankDocument5 pagesEthics and Issues in Contemporary Nursing Canadian 3rd Edition Burkhardt Test Bankhungden8pne100% (31)

- Contemporary Strategy Analysis Text and Cases 8th Edition Grant Test BankDocument9 pagesContemporary Strategy Analysis Text and Cases 8th Edition Grant Test Bankdoijethrochsszo100% (32)

- International Economics 9th Edition Krugman Test BankDocument16 pagesInternational Economics 9th Edition Krugman Test BankLoriHamiltonrxgj100% (59)

- C Programming Program Design Including Data Structures 7th Edition Malik Solutions ManualDocument8 pagesC Programming Program Design Including Data Structures 7th Edition Malik Solutions Manualdenthanhfnv100% (29)

- Microeconomics 3rd Edition Krugman Test BankDocument10 pagesMicroeconomics 3rd Edition Krugman Test Bankmagnusngah7aaz100% (41)

- International Economics 8th Edition Appleyard Solutions ManualDocument14 pagesInternational Economics 8th Edition Appleyard Solutions Manualclitusarielbeehax100% (36)

- Econ Macro Canadian 1st Edition Mceachern Solutions ManualDocument25 pagesEcon Macro Canadian 1st Edition Mceachern Solutions ManualJohnathanFitzgeraldnwoa100% (58)

- Full Download Corporate Financial Management 5th Edition Glen Arnold Test BankDocument35 pagesFull Download Corporate Financial Management 5th Edition Glen Arnold Test Bankskudalmasaval100% (35)

- International Financial Management 13th Edition Madura Test BankDocument25 pagesInternational Financial Management 13th Edition Madura Test BankMichaelSmithspqn100% (55)

- Discovering The Scientist Within Research Methods in Psychology 1st Edition Lewandowski Test BankDocument26 pagesDiscovering The Scientist Within Research Methods in Psychology 1st Edition Lewandowski Test Bankdariusluyen586100% (28)

- Discovering Psychology 7th Edition Hockenbury Test BankDocument25 pagesDiscovering Psychology 7th Edition Hockenbury Test BankVanessaGriffinmrik100% (63)

- Essential University Physics Volume II 3rd Edition Wolfson Solutions ManualDocument27 pagesEssential University Physics Volume II 3rd Edition Wolfson Solutions Manualfelixedanafte5n100% (31)

- International Finance Theory and Policy 10th Edition Krugman Solutions ManualDocument26 pagesInternational Finance Theory and Policy 10th Edition Krugman Solutions ManualMariaHowelloatq100% (56)

- International Macroeconomics 4th Edition Feenstra Solutions ManualDocument25 pagesInternational Macroeconomics 4th Edition Feenstra Solutions ManualElizabethPhillipsfztqc100% (66)

- Earths Climate Past and Future 3rd Edition Ruddiman Solutions ManualDocument3 pagesEarths Climate Past and Future 3rd Edition Ruddiman Solutions Manualheulwenfidelma2dg5100% (32)

- Introduct Programmi C International 3rd Edition Liang Test BankDocument7 pagesIntroduct Programmi C International 3rd Edition Liang Test Bankadelaidelatifahjq8w5100% (40)

- International Finance Theory and Policy 10Th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument27 pagesInternational Finance Theory and Policy 10Th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFPamelaHillqans100% (14)

- Ebook College Accounting 12Th Edition Slater Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument60 pagesEbook College Accounting 12Th Edition Slater Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFkhucly5cst100% (15)

- Ebook College Accounting A Contemporary Approach 3Rd Edition Haddock Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument68 pagesEbook College Accounting A Contemporary Approach 3Rd Edition Haddock Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFkhucly5cst100% (12)

- Ebook College Accounting 21St Edition Heintz Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument52 pagesEbook College Accounting 21St Edition Heintz Test Bank Full Chapter PDFkhucly5cst100% (14)

- Ebook College Accounting A Career Approach 13Th Edition Scott Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument52 pagesEbook College Accounting A Career Approach 13Th Edition Scott Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFkhucly5cst100% (12)

- Ebook College Accounting A Career Approach 12Th Edition Scott Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument57 pagesEbook College Accounting A Career Approach 12Th Edition Scott Test Bank Full Chapter PDFkhucly5cst100% (14)

- International Marketing 10th Edition Czinkota Test BankDocument12 pagesInternational Marketing 10th Edition Czinkota Test Bankkhucly5cst100% (25)

- Ebook College Accounting 21St Edition Heintz Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument44 pagesEbook College Accounting 21St Edition Heintz Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFkhucly5cst100% (16)

- Ebook College Accounting 14Th Edition Price Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument50 pagesEbook College Accounting 14Th Edition Price Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFkhucly5cst100% (17)

- International Economics Theory and Policy 10th Edition Krugman Solutions ManualDocument7 pagesInternational Economics Theory and Policy 10th Edition Krugman Solutions Manualkhucly5cst100% (19)

- International Financial Management 8th Edition Madura Solutions ManualDocument8 pagesInternational Financial Management 8th Edition Madura Solutions Manualkhucly5cst100% (28)

- International Economics 7th Edition Gerber Solutions ManualDocument8 pagesInternational Economics 7th Edition Gerber Solutions ManualAmberFranklinegrn100% (50)

- International Economics 16th Edition Thomas Pugel Test BankDocument24 pagesInternational Economics 16th Edition Thomas Pugel Test Bankkhucly5cst100% (30)

- Chap 4.3 Intertemporal Price DiscriminationDocument2 pagesChap 4.3 Intertemporal Price DiscriminationHiền Trang LêNo ratings yet

- Economics Quiz 3Document3 pagesEconomics Quiz 3Pao EspiNo ratings yet

- TOEIC EXERCISE (Part4) AnswerkeyDocument4 pagesTOEIC EXERCISE (Part4) AnswerkeyMayar saidaniNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Profitabilitas, Likuiditas, Ukuran Perusahaan Dan Pertumbuhan Perusahaan Terhadap Opini Audit Going ConcernDocument10 pagesPengaruh Profitabilitas, Likuiditas, Ukuran Perusahaan Dan Pertumbuhan Perusahaan Terhadap Opini Audit Going ConcernPraharsini MadasNo ratings yet

- Appendix 4A: Net Present Value: First Principles of FinanceDocument14 pagesAppendix 4A: Net Present Value: First Principles of FinanceSAURABH SINGHNo ratings yet

- Apollo Medicine InvoiceMay 19 2022 15 11Document1 pageApollo Medicine InvoiceMay 19 2022 15 11CA Sumit GargNo ratings yet

- Session 3 CBA in Secondary MarketDocument10 pagesSession 3 CBA in Secondary MarketShabahul ArafiNo ratings yet

- Quiz Two: University of Hong Kong CCCH9007 China in The Global EconomyDocument3 pagesQuiz Two: University of Hong Kong CCCH9007 China in The Global EconomyChunming TangNo ratings yet

- Conveyor Chains: DIN 8167 / M SeriesDocument3 pagesConveyor Chains: DIN 8167 / M SeriesMaiquel Eduardo ErnNo ratings yet

- Barrage BOQDocument19 pagesBarrage BOQPowerhouse ShaftNo ratings yet

- Magbook Indian Economy-ArihantDocument241 pagesMagbook Indian Economy-Arihantmanish100% (3)

- 669 1354 1 SMDocument18 pages669 1354 1 SMFurqaan SyahNo ratings yet

- Ruralstar Site Tower Construction SOP V3.0Document48 pagesRuralstar Site Tower Construction SOP V3.0goytomhayle8126No ratings yet

- Dokumen - Tips Oliver Velez Swing Core Guerrilla Options Trading Tactics (1) (001 078)Document78 pagesDokumen - Tips Oliver Velez Swing Core Guerrilla Options Trading Tactics (1) (001 078)Sergio MoralesNo ratings yet

- College of Physicians & Surgeons Pakistan: Online Application Form (FCPS-I) ExaminationDocument2 pagesCollege of Physicians & Surgeons Pakistan: Online Application Form (FCPS-I) ExaminationUsama BilalNo ratings yet

- Prospectus MPL 33rd - National U17 2023Document8 pagesProspectus MPL 33rd - National U17 2023sanchita yadav100% (1)

- Risk Management in ConstructionDocument10 pagesRisk Management in ConstructionNiharika SharmaNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Logistics ManagementDocument4 pagesSyllabus Logistics ManagementRegine NanitNo ratings yet

- Get PDFDocument10 pagesGet PDFSantoshNo ratings yet

- Approved Drawing of Boundary WallDocument1 pageApproved Drawing of Boundary WallAnup Singh RajputNo ratings yet

- Anna University: Centre For Distance EducationDocument1 pageAnna University: Centre For Distance EducationMeghal SivanNo ratings yet

- Design and Development of Mini Tractor Operated Installer and Retriever of Drip LineDocument12 pagesDesign and Development of Mini Tractor Operated Installer and Retriever of Drip Line01fe18bme033No ratings yet

- Organization Structure 2016: Head Office Pt. Saptaindra SejatiDocument2 pagesOrganization Structure 2016: Head Office Pt. Saptaindra SejatiAhMad FajRi DefaNo ratings yet

- Report 4Document32 pagesReport 4BILENGE MALILONo ratings yet

- LRFDDocument14 pagesLRFDKrischanSayloGelasanNo ratings yet

- BS 6004-12Document34 pagesBS 6004-12jamilNo ratings yet

- RFP2Document122 pagesRFP2RAMKRIPAL SINGH CONSTRUCTION PVT. LTD.No ratings yet

- The Impact of Earnings Management On The Value Relevance of EarningsDocument25 pagesThe Impact of Earnings Management On The Value Relevance of Earningsanubha srivastavaNo ratings yet

- Chapter PDFDocument55 pagesChapter PDFWonde BiruNo ratings yet

- Cost Accounting 3Document3 pagesCost Accounting 3sharu SKNo ratings yet