Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Preventive Detention

Preventive Detention

Uploaded by

Syed Misbahul IslamOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Preventive Detention

Preventive Detention

Uploaded by

Syed Misbahul IslamCopyright:

Available Formats

Preventive Detention - UPSC Notes

Preventive detention is basically detention without trial in order to prevent a person from committing a

crime. This is an important concept in law and finds frequent mention in the daily news. In this article, you

can read all about preventive detention, its meaning, the Supreme Court's stand on preventive detention and

other details for the UPSC exam.

Preventive Detention - Meaning & Scope

The law and issue concerning and connected to Preventive Detention is an issue of personal liberty and by

default an issue pertaining to human rights.

• Preventive detention refers to taking into custody an individual who has not committed a crime yet

but the authorities believe him to be a threat to law and order.

• The Supreme Court in Alijav v. District Magistrate, Dhanbad, stated that while criminal proceedings

relate to punishing of a person for an offence committed by him, preventive detention does not relate

to an offence.

• In Ankul Chandra Pradhan v. Union of India, the Court stated that the object of preventive detention

is not to punish but prevent the detenue from doing anything that is prejudicial to the security of the

state.

• The power to make Preventive Detention laws in India comes from the Constitution itself which

empowers the Parliament to make such laws for reasons connected with Defence, Foreign Affairs or

the Security of India. Parliament has exclusive legislative powers.

• The Union and the States have concurrent legislative powers for reasons connected with the security

of a State, the maintenance of public order or the maintenance of supplies and services essential to

the community.

• Such detention involves custody without any criminal trial, moreover these laws need not follow the

procedural guarantees which are fundamental to the detention of an individual in the normal course.

• The Parliament has enacted several laws in this respect which in addition to the notorious Preventive

Detention Act include:

o The National Security Act, Section 13, 1980 (provides for administrative detention for a

period of up to one year)

o The Conservation of Foreign Exchange and Prevention of Smuggling Activities Act, 1974

(COFEPOSA) (provides for administrative detention for a period of up to six months)

o The Prevention of Black-marketing and Maintenance of Supplies of Essential Commodities

Act, Section 13, 1980 (six months)

o The Prevention of Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, Section

10, 1988.

Supreme Court on Preventive Detention

Some cases in which the SC talked about preventive detention are discussed below.

• The first case to come before the Supreme Court was AK Gopalan v. State of Madras, in which the

Court upheld the validity of the Preventive Detention Act. Moreover, the Court also held that Article

22 of the Constitution also provides exhaustive procedural safeguards with respect to preventive

detention. Therefore, the Court said that fundamental rights were not violated by the impugned act

because it met all the procedural safeguards that are provided in Article 22(5).

Also read: Articles 19 - 22, Right to Freedom

• In Ram Manohar Lohia v. State of Bihar, the Supreme Court attempted to distinguish between the

concepts "security of state," "public order," and "law and order." In an astoundingly often-quoted

passage, Justice Hidayatullah underscored that only the most severe of acts could justify preventive

detention:

o One has to imagine three concentric circles. Law and order represents the largest circle

within which is the next circle representing public order and the smallest circle represents

security of state. It is then easy to see that an act may affect law and order but not public

order just as an act might affect public order but not security of state.

o The Court concluded that acts affecting only "law and order" without one of the other two

categories cannot be a sufficient justification on which to base a detention order. Of course,

this analysis, its academic benefits aside, provides little clarification of the contested

concepts, as it suggests only that courts may examine the executive's assessments of threats to

public security.

• In Anil Dey v. State of West Bengal, the Supreme Court held that “the veil of subjective satisfaction

of the detaining authority cannot be lifted by the courts with a view to appreciate its objective

sufficiency”. Although the courts “cannot substitute their own opinion for that of the detaining

authority by applying an objective test to decide the necessity of detention for specified purpose, they

do review whether the satisfaction is “honest and real, and not fanciful and imaginary”. The

executive is, therefore, required by the courts to apply its mind to the decision to issue a detention

order.

CONCLUSION

Article 22 was in fact a measure to protect, rather than curtail, the right to life and personal liberty. Mr

Seervai discusses this in his Commentary, to conclude that perhaps it would have made better sense to have

the first two clauses in Article 22 as part of Article 21, making a separate article for the exclusions. Looking

at what happened subsequently, a differently drafted Article 21 might have led to a differently written

judgment in the Maneka Gandhi case. It might have prevented the Supreme Court from going so far as to

incorporate the substantive due process standard that the Constituent Assembly so painstakingly chose to

avoid. Where does Maneka Gandhi leave the due process that Article 22 represented for the Constituent

Assembly and Dr. Ambedkar? The Supreme Court has not considered this question fully, yet, although some

seepage of Maneka jurisprudence into Article 22 has definitely resulted.

You might also like

- Table of PenaltiesDocument5 pagesTable of PenaltiesDominic Embodo50% (2)

- Arellano vs. CFI of SorsogonDocument8 pagesArellano vs. CFI of SorsogonMaestro LazaroNo ratings yet

- Crime and Mental IllnessDocument9 pagesCrime and Mental Illnessapi-340382341No ratings yet

- Project - Socio Economic OffencesDocument10 pagesProject - Socio Economic Offencessrikant sirkaNo ratings yet

- Preventive Detention IndiaDocument41 pagesPreventive Detention IndiaSuryapratap singh jodhaNo ratings yet

- Article 22 and Preventive Detention in IndiaDocument3 pagesArticle 22 and Preventive Detention in IndiaAvijit SilawatNo ratings yet

- Unit-1 Preventive Detention of Law Under Indian Constitution PDFDocument35 pagesUnit-1 Preventive Detention of Law Under Indian Constitution PDFkuldeep Roy Singh100% (1)

- Unit-1 Preventive Detention of Law Under Indian Constitution PDFDocument35 pagesUnit-1 Preventive Detention of Law Under Indian Constitution PDFkuldeep Roy SinghNo ratings yet

- Notes by NishDocument10 pagesNotes by NisharonyuNo ratings yet

- P MDocument5 pagesP MBhavika Singh JangraNo ratings yet

- Continuous Internal Assessment - I: Socio - Economic Offences Optional-2Document9 pagesContinuous Internal Assessment - I: Socio - Economic Offences Optional-2roshanNo ratings yet

- Swadeshi Cotton MillsDocument3 pagesSwadeshi Cotton MillsVihanka NarasimhanNo ratings yet

- Approach - Answer:: ABHYAAS TEST 2 - 2032 (2021)Document23 pagesApproach - Answer:: ABHYAAS TEST 2 - 2032 (2021)Harika NelliNo ratings yet

- Article 22: Not A Complete Code Article 22: Not A Complete Code Rights of Arrested Persons Under Ordinary LawsDocument13 pagesArticle 22: Not A Complete Code Article 22: Not A Complete Code Rights of Arrested Persons Under Ordinary LawsKpscNo ratings yet

- Indian Constitution Final DrafttDocument11 pagesIndian Constitution Final DrafttSatyam MalakarNo ratings yet

- Analyzing Preventive Detention in Light of Constitutional ProvisionsDocument20 pagesAnalyzing Preventive Detention in Light of Constitutional ProvisionsRahul TambiNo ratings yet

- Rule of Law in India: An Overview: Surya DevaDocument8 pagesRule of Law in India: An Overview: Surya DevaUmair Ahmed AndrabiNo ratings yet

- Project Topic: Department of Law, School of Legal Studies Central University of Kashmir, GanderbalDocument10 pagesProject Topic: Department of Law, School of Legal Studies Central University of Kashmir, GanderbalhennaNo ratings yet

- Bharti Vidhyapeeth Deemed University: Constitutional Law-IDocument11 pagesBharti Vidhyapeeth Deemed University: Constitutional Law-IPRAGYANo ratings yet

- Conceptualising Sentencing Policy in IndiaDocument19 pagesConceptualising Sentencing Policy in IndiaShahaji Law CollegeNo ratings yet

- A 22 - C T P D: Rticle Alling Ime On Reventive EtentionDocument13 pagesA 22 - C T P D: Rticle Alling Ime On Reventive EtentionPanya MathurNo ratings yet

- Notes by NishDocument8 pagesNotes by Nisharonyu100% (2)

- Legal Doctrines Used in IndiaDocument14 pagesLegal Doctrines Used in IndiaAkanksha PandeyNo ratings yet

- Preventive DetentionDocument4 pagesPreventive Detentiondrako lNo ratings yet

- 1 August 2022Document14 pages1 August 2022Vijay Kumar VipparthiNo ratings yet

- If The Bench Is WellDocument4 pagesIf The Bench Is Wellgauri sharmaNo ratings yet

- 11 Chapter 5Document168 pages11 Chapter 5Sachin KumarNo ratings yet

- R O A P: Hidayatullah National Law University, RaipurDocument22 pagesR O A P: Hidayatullah National Law University, Raipurshikah sidarNo ratings yet

- Role of Courts in Upholding Rule of LawDocument19 pagesRole of Courts in Upholding Rule of LawRitikaSahniNo ratings yet

- Art 22 Law 201Document24 pagesArt 22 Law 201Anjali MakkarNo ratings yet

- Audi Alteram PartemDocument5 pagesAudi Alteram PartemRajat MishraNo ratings yet

- Audi Alteram PartemDocument5 pagesAudi Alteram PartemRajat Mishra100% (1)

- The Limitation Act, 1963: Reading Material OnDocument51 pagesThe Limitation Act, 1963: Reading Material OnJayantNo ratings yet

- Audi Alteram PartemDocument6 pagesAudi Alteram PartemArpit Jain100% (1)

- Judicial Activism and Article 21: Personal Views About Public Policy, Among Other Factors, To Guide Their Decisions." (I)Document9 pagesJudicial Activism and Article 21: Personal Views About Public Policy, Among Other Factors, To Guide Their Decisions." (I)Ankit JindalNo ratings yet

- Module Admin LawDocument18 pagesModule Admin LawSean MuthuswamyNo ratings yet

- Limitation Act Bullet Notes by Anuraag SirDocument52 pagesLimitation Act Bullet Notes by Anuraag SirGarvish DosiNo ratings yet

- Judicial ActivismDocument9 pagesJudicial Activismkhushi guptaNo ratings yet

- Article 22Document16 pagesArticle 22Navreen RasheedNo ratings yet

- Natural JusticeDocument31 pagesNatural Justicekumar Pritam0% (1)

- Rights of Arrested PersonDocument18 pagesRights of Arrested PersonAshutosh YadavNo ratings yet

- UNIT - 1 - Nature of Judicail ProcessDocument40 pagesUNIT - 1 - Nature of Judicail ProcessEmily FosterNo ratings yet

- Constitutionalism Assignment 2Document4 pagesConstitutionalism Assignment 2kamal nayanNo ratings yet

- Article 21 in Light of Police AtrocitiesDocument9 pagesArticle 21 in Light of Police AtrocitiesManas UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Expanding Scope of Right To Life and Liberty Under Article 21Document7 pagesExpanding Scope of Right To Life and Liberty Under Article 21adinadhNo ratings yet

- Justice Mr. V. G. Palshikar (Retd.) : Judicial ActivismDocument11 pagesJustice Mr. V. G. Palshikar (Retd.) : Judicial Activismpiyush_natkhat100% (1)

- Preventive Detention: An Evil of Article 22Document7 pagesPreventive Detention: An Evil of Article 22Charlie PushparajNo ratings yet

- Preventive Detention and National Security ActDocument6 pagesPreventive Detention and National Security ActAkanksha SinghNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis On A.K. Roy V. Union of IndiaDocument6 pagesCase Analysis On A.K. Roy V. Union of IndiaPriyansh KohliNo ratings yet

- Article 14pptDocument33 pagesArticle 14pptTushti DhawanNo ratings yet

- Submitted By: Constitutional Validity of Preventive Detention LawsDocument15 pagesSubmitted By: Constitutional Validity of Preventive Detention LawsPrabhnoor GulianiNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Rights PDFDocument8 pagesConstitutional Rights PDFCharlie PushparajNo ratings yet

- Limitation BookDocument50 pagesLimitation BookHarsh Vardhan Singh HvsNo ratings yet

- Judicial Review PolityDocument3 pagesJudicial Review PolityAditi TripathiNo ratings yet

- Reform in Bail LawDocument11 pagesReform in Bail Law22010125345No ratings yet

- Crime and Punishment Endsems - AnoushkaDocument20 pagesCrime and Punishment Endsems - AnoushkaHashir KhanNo ratings yet

- Case A Large Bench of 7 Judge Was: SP Sampath Kumar v. UOI 1987 SCR (3) 233. L. Chandra Kumar v. UOI (1977) 3 SCC 261Document6 pagesCase A Large Bench of 7 Judge Was: SP Sampath Kumar v. UOI 1987 SCR (3) 233. L. Chandra Kumar v. UOI (1977) 3 SCC 261Kamal NaraniyaNo ratings yet

- ABS On Public Policy Making in IndiaDocument18 pagesABS On Public Policy Making in Indianimisha ksNo ratings yet

- Illegal ArrestDocument8 pagesIllegal ArrestsonamkumariNo ratings yet

- Legal Project Pictures PDFDocument11 pagesLegal Project Pictures PDFEshan GargNo ratings yet

- Liberty After Freedom: A History of Article 21, Due Process and the Constitution of IndiaFrom EverandLiberty After Freedom: A History of Article 21, Due Process and the Constitution of IndiaNo ratings yet

- Human Rights in the Indian Armed Forces: An Analysis of Article 33From EverandHuman Rights in the Indian Armed Forces: An Analysis of Article 33No ratings yet

- Contract Exam Prep 2Document27 pagesContract Exam Prep 2Syed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Answer 2023 of Indian Penal CodeDocument142 pagesAnswer 2023 of Indian Penal CodeSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Pol SC Exam prEPARATIONDocument58 pagesPol SC Exam prEPARATIONSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Ipc Mar 20, 2023Document6 pagesIpc Mar 20, 2023Syed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- University of Calcutta: TheoreticalDocument1 pageUniversity of Calcutta: TheoreticalSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Allotment lB.A LLB-1Document1 pageAllotment lB.A LLB-1Syed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Precedent As A Source of LawDocument8 pagesPrecedent As A Source of LawSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- 191030B.A.LL.B 2nd, 4th, 6th, 8th Exam RotuineDocument4 pages191030B.A.LL.B 2nd, 4th, 6th, 8th Exam RotuineSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Classification of LawDocument7 pagesClassification of LawSyed Misbahul Islam100% (1)

- 5th Sem - Question BankDocument43 pages5th Sem - Question BankSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Legal MethodDocument19 pagesLegal MethodSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- SLS, Pune - LL.M. 2022-23Document10 pagesSLS, Pune - LL.M. 2022-23Syed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Followers of Hindu ReligionDocument50 pagesFollowers of Hindu ReligionSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Somai, Osomai, Sob Somai: All The Best For Your Upcoming Semester ExaminationDocument7 pagesSomai, Osomai, Sob Somai: All The Best For Your Upcoming Semester ExaminationSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- True Test of A PartnershipDocument11 pagesTrue Test of A PartnershipSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- 3RD Eco PerfectDocument3 pages3RD Eco PerfectSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- BiriDocument3 pagesBiriSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Misbahul Sociology Sem 3Document11 pagesMisbahul Sociology Sem 3Syed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Agents of SocializationDocument13 pagesAgents of SocializationSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument2 pagesUntitledSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- _ (1)Document8 pages_ (1)Syed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Case Study of Indian Council Act 1909Document10 pagesCase Study of Indian Council Act 1909Syed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument1 pageUntitledSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Data Analysis Synthesis and InterpretationDocument3 pagesData Analysis Synthesis and InterpretationSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Brief Indian Council Act 1909Document14 pagesBrief Indian Council Act 1909Syed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

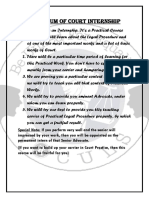

- Memorandum of COURT INTERNSHIPDocument1 pageMemorandum of COURT INTERNSHIPSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 30 May 2022Document1 pageAdobe Scan 30 May 2022Syed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Drafting Rules & SkillsDocument10 pagesDrafting Rules & SkillsSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 31 Oct 2021Document1 pageAdobe Scan 31 Oct 2021Syed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Pol SC Asignment 2 Sem 2 PDFDocument1 pagePol SC Asignment 2 Sem 2 PDFSyed Misbahul IslamNo ratings yet

- Putusan NarkobaDocument18 pagesPutusan Narkobahelen solagratiaNo ratings yet

- Defects Liability After The Contract Has Been Terminated by The ContractorDocument1 pageDefects Liability After The Contract Has Been Terminated by The ContractorMayouran WijayakumarNo ratings yet

- RA-Republic Act No. 10175Document13 pagesRA-Republic Act No. 10175Ailein GraceNo ratings yet

- Wrongfully Convicted - Amicale Case - Rama Valayden - MauritiusDocument228 pagesWrongfully Convicted - Amicale Case - Rama Valayden - Mauritiusanwar.buchoo100% (8)

- Attachment 8 Signed Sodexo ContractDocument36 pagesAttachment 8 Signed Sodexo ContractVidki IndiaNo ratings yet

- Stanley Morris Correspondence July 21Document2 pagesStanley Morris Correspondence July 21ExtiNo ratings yet

- Civil Actions vs. Special Proceedings 5. Personal Actions and Real ActionsDocument4 pagesCivil Actions vs. Special Proceedings 5. Personal Actions and Real ActionsHazel LunaNo ratings yet

- WOMEN IN Global TOURISMDocument15 pagesWOMEN IN Global TOURISMJedy SoNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of DesistanceDocument3 pagesAffidavit of DesistanceKenneth BaquianoNo ratings yet

- Sue-Ann Lau I-Shan V Yee Keen Mingv Yee Keen Ming (2011Document8 pagesSue-Ann Lau I-Shan V Yee Keen Mingv Yee Keen Ming (2011azilaNo ratings yet

- 4 People vs. Taneo 58 Phil. 255Document3 pages4 People vs. Taneo 58 Phil. 255EFGNo ratings yet

- CANUEL V MAGSAYSAY MARITIME CORP. Case DigestDocument3 pagesCANUEL V MAGSAYSAY MARITIME CORP. Case DigestJazzy Alim100% (1)

- Spanish Civil Code (Codigo Civil Espanol)Document355 pagesSpanish Civil Code (Codigo Civil Espanol)D. MouseNo ratings yet

- The Poisons Act 1919: AnswerDocument3 pagesThe Poisons Act 1919: AnswerHabibur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Oblicon Case Digest: Pay V. Vda. de PalancaDocument42 pagesOblicon Case Digest: Pay V. Vda. de PalancaAleezah Gertrude RegadoNo ratings yet

- By Laws AmendmentDocument22 pagesBy Laws AmendmentJouaine Sobiono OmbayNo ratings yet

- How To Write A First Class Law DissertationDocument36 pagesHow To Write A First Class Law DissertationAngela Canares100% (1)

- Section5 - Tender and Contract FormsDocument4 pagesSection5 - Tender and Contract FormsMd Faysal Ahmed RafeNo ratings yet

- Simons Torts Outline 2013Document25 pagesSimons Torts Outline 2013jal2100No ratings yet

- SPA For SellingDocument6 pagesSPA For SellingHenryV.BrigueraNo ratings yet

- Sps. Perena vs. Sps. ZarateDocument27 pagesSps. Perena vs. Sps. ZarateChristine Gel MadrilejoNo ratings yet

- RA 6657. Prohibited Acts and OmissionsDocument1 pageRA 6657. Prohibited Acts and OmissionsMark Joseph Pedroso CendanaNo ratings yet

- Rules On Evidence (CODAL)Document17 pagesRules On Evidence (CODAL)Katherine Herza Cobing100% (1)

- Wilfredo Mosgueda, Et. Al vs. Pilipino Banana Growers and Exporters Association, Inc. and City of Davao PDFDocument59 pagesWilfredo Mosgueda, Et. Al vs. Pilipino Banana Growers and Exporters Association, Inc. and City of Davao PDFTasneem C BalindongNo ratings yet

- Law of Commercial PapersDocument43 pagesLaw of Commercial PapersYogeeshwaran PonnuchamyNo ratings yet

- At The End of The Day, Everything Comes Down To Contract Law As Everyone Has A Contract They Must FollowDocument171 pagesAt The End of The Day, Everything Comes Down To Contract Law As Everyone Has A Contract They Must FollowSue BozgozNo ratings yet

- People v. Baharan, G.R. No. 188314. January 10, 2011 PDFDocument19 pagesPeople v. Baharan, G.R. No. 188314. January 10, 2011 PDFJohzzyluck R. MaghuyopNo ratings yet