Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lock Out Agreement

Lock Out Agreement

Uploaded by

Eldard KafulaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- LL Tq4za2016Document3 pagesLL Tq4za2016Law henryNo ratings yet

- Cape Law: Texts and Cases - Contract Law, Tort Law, and Real PropertyFrom EverandCape Law: Texts and Cases - Contract Law, Tort Law, and Real PropertyNo ratings yet

- STAR SHIPPING V CHINA NATIONAL FOREIGN TRADE (Seat Law)Document12 pagesSTAR SHIPPING V CHINA NATIONAL FOREIGN TRADE (Seat Law)Shubham SarkarNo ratings yet

- Oblicon Case Digests (Finals)Document21 pagesOblicon Case Digests (Finals)Ernie Gultiano100% (1)

- GQ Magazine August 2011Document2 pagesGQ Magazine August 2011RamkumarNo ratings yet

- Central London Property Trust LTD V High Trees House Ltd-HighlightedDocument4 pagesCentral London Property Trust LTD V High Trees House Ltd-Highlightedwaffles over pancakes100% (1)

- Law of Contract: FrustrationDocument12 pagesLaw of Contract: FrustrationJ. Angel AiozNo ratings yet

- FrustrationDocument8 pagesFrustrationIan Mual PeterNo ratings yet

- Contract Net NotesDocument7 pagesContract Net NotesdenisNo ratings yet

- Frustration (Notes and Cases)Document6 pagesFrustration (Notes and Cases)Brett SmithNo ratings yet

- Seminário 2 - 10JLegalHist90-1 - FrustrationDocument21 pagesSeminário 2 - 10JLegalHist90-1 - FrustrationMaria Eduarda LessaNo ratings yet

- Terms - Lecture 5Document22 pagesTerms - Lecture 5Lim Kok SeanNo ratings yet

- 9 - Terms Implied by Common LawDocument3 pages9 - Terms Implied by Common LawkennedyopNo ratings yet

- Week 6 Contract ConstructionDocument73 pagesWeek 6 Contract ConstructionLili ChenNo ratings yet

- Consideration CasesDocument22 pagesConsideration CasesMuhaye BridgetNo ratings yet

- Kowloon Development Finance LTD V Pendex Industries LTDDocument9 pagesKowloon Development Finance LTD V Pendex Industries LTDChristopher JayNo ratings yet

- CH 02 LAW 379Document10 pagesCH 02 LAW 379Nur Ariefah SaidNo ratings yet

- THE DOCTRINE OF FRUSTRATION - The Lawyers & JuristsDocument10 pagesTHE DOCTRINE OF FRUSTRATION - The Lawyers & JuristsEddie NyikaNo ratings yet

- Commercial Law Lecture 9Document10 pagesCommercial Law Lecture 9Ismail PatelNo ratings yet

- Week 1 - Agreement (Offer)Document58 pagesWeek 1 - Agreement (Offer)Aronyo DeyNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 Contract Formation ApproachesDocument2 pagesUnit 5 Contract Formation ApproacheslalitNo ratings yet

- Impossibility of Performance - Frustration: by DR Suzi Fadhilah IsmailDocument83 pagesImpossibility of Performance - Frustration: by DR Suzi Fadhilah IsmailNu'man AzhamNo ratings yet

- (2007) EWCA Civ 1329Document17 pages(2007) EWCA Civ 1329fsm20221227No ratings yet

- Ks PPT 1 A 2023 RevisedDocument64 pagesKs PPT 1 A 2023 Revisedninjaalex225No ratings yet

- 1996 - Hedley - C.I.F. Contract. Commercial Arbitration. Acceptance of Anticipatory Breach - Steve HedleyDocument4 pages1996 - Hedley - C.I.F. Contract. Commercial Arbitration. Acceptance of Anticipatory Breach - Steve HedleyJoana VitorinoNo ratings yet

- AgreementDocument57 pagesAgreementSarah DarkoNo ratings yet

- Repudiation, Anticipatory Breach and Conditions in A Contract For ServicesDocument7 pagesRepudiation, Anticipatory Breach and Conditions in A Contract For ServicesYash TiwariNo ratings yet

- 2Document17 pages2Đinesh ĢunasenaNo ratings yet

- Glade Mountain Corp. v. Reconstruction Finance Corp, 200 F.2d 815, 3rd Cir. (1952)Document4 pagesGlade Mountain Corp. v. Reconstruction Finance Corp, 200 F.2d 815, 3rd Cir. (1952)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Contract Formation - Offer and AcceptanceDocument30 pagesContract Formation - Offer and AcceptanceNoor FaraNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Frustration-2022b WeeknedDocument6 pagesDoctrine of Frustration-2022b Weeknedakwasiamoh501No ratings yet

- MistakeDocument13 pagesMistakeBrett SmithNo ratings yet

- Lecture 18 - Discharge by FrustrationDocument6 pagesLecture 18 - Discharge by FrustrationBrett SmithNo ratings yet

- Discharge by FrustrationDocument10 pagesDischarge by FrustrationSylviane Sie Siu MingNo ratings yet

- Red Zone-Cadwalader Wicker Sham Taft LawsuitDocument16 pagesRed Zone-Cadwalader Wicker Sham Taft Lawsuitchris_clair9652No ratings yet

- Contract Law - Offer Acceptance SCDocument42 pagesContract Law - Offer Acceptance SChannushaNo ratings yet

- 4 Certainty and Agreement MistakesDocument9 pages4 Certainty and Agreement Mistakesyonyo90No ratings yet

- The Doctrine of Frustration-1Document24 pagesThe Doctrine of Frustration-1gaurangiNo ratings yet

- Property Exam 2023Document2 pagesProperty Exam 2023marija.kutalovskaja24No ratings yet

- Mistake 1Document10 pagesMistake 1niyiNo ratings yet

- FrustrationDocument12 pagesFrustrationcwangheichanNo ratings yet

- ALL ER 1942 Volume 1Document457 pagesALL ER 1942 Volume 1dpmugambiadvocatesNo ratings yet

- Nova (Jersey) Knit LTD V Kammgarn Spinnerei GMBH, (1977) 2 All Er 463Document7 pagesNova (Jersey) Knit LTD V Kammgarn Spinnerei GMBH, (1977) 2 All Er 463mehalNo ratings yet

- (1952) 2 Q.B. 297Document11 pages(1952) 2 Q.B. 297Joshua ChanNo ratings yet

- Agreement-Contract, Offer-AcceptanceDocument69 pagesAgreement-Contract, Offer-AcceptanceAbhinav PandeyNo ratings yet

- Principle of Business LawDocument14 pagesPrinciple of Business LawMaya DomaNo ratings yet

- Steadman V. Steadman1: NotesDocument5 pagesSteadman V. Steadman1: Notesnkumbunamonje30No ratings yet

- Certainty: BY Mrs SimbotweDocument16 pagesCertainty: BY Mrs SimbotweTremor BandaNo ratings yet

- BusinesslawDocument14 pagesBusinesslawDebangan DasNo ratings yet

- A. Express TermsDocument27 pagesA. Express TermscwangheichanNo ratings yet

- Abdallah 223796 Asg 2 MistakeDocument5 pagesAbdallah 223796 Asg 2 Mistakeabdallahnashaat3No ratings yet

- Cases On Discharge of ContractDocument5 pagesCases On Discharge of ContractVIVEKNo ratings yet

- Howard MarineDocument3 pagesHoward MarineMichael CruzNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - Implied - Express TermsDocument12 pagesChapter 4 - Implied - Express TermssupremeshaktivelNo ratings yet

- Problem Solving CompressDocument21 pagesProblem Solving CompressJaycee HowNo ratings yet

- 06Document21 pages06Huong GiangNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Law240 Law of ContractDocument40 pagesChapter 2 Law240 Law of Contractatyizzaty04No ratings yet

- CIF ContractsDocument18 pagesCIF Contractsceleguk75% (4)

- Koppel Inc. v. Makati Rotary Club FoundationDocument20 pagesKoppel Inc. v. Makati Rotary Club FoundationJoshuaMaulaNo ratings yet

- Performances: Cases On Discharge of ContractDocument5 pagesPerformances: Cases On Discharge of ContractVIVEKNo ratings yet

- Frustration Revision NotesDocument9 pagesFrustration Revision NotesRohin BansalNo ratings yet

- Abdallah Irunde v. Msunga Ntunda & Abeid Msunga, Misc. Civil Appeal No.38 of 2019Document7 pagesAbdallah Irunde v. Msunga Ntunda & Abeid Msunga, Misc. Civil Appeal No.38 of 2019Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Stanbic Bank T Ltd vs Grace Mushi (Revision No 386 of 2015) 2018 TZHCLD 404 (10 May 2018)Document26 pagesStanbic Bank T Ltd vs Grace Mushi (Revision No 386 of 2015) 2018 TZHCLD 404 (10 May 2018)Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- LST Students Dress CodeDocument3 pagesLST Students Dress CodeEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts CaseDocument20 pagesLaw of Torts CaseEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Arsenal Footbal CaseDocument17 pagesArsenal Footbal CaseEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- NHRI Kenya National Commission on HRDocument10 pagesNHRI Kenya National Commission on HREldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Mayamba Mjarifu CaseDocument16 pagesMayamba Mjarifu CaseEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Benard Cosmas Vs Republic (Criminal Appeal 49 of 2021) 2022 TZHC 10780 (26 July 2022)Document11 pagesBenard Cosmas Vs Republic (Criminal Appeal 49 of 2021) 2022 TZHC 10780 (26 July 2022)Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Intellectual PropertyDocument22 pagesIntellectual PropertyEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Bakhresa CaseDocument12 pagesBakhresa CaseEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Nurdin Mohamed Ahmed at Sheikh Kishiki V MIC Tanzania Limited, Civil Appeal No.85 of 2019Document22 pagesNurdin Mohamed Ahmed at Sheikh Kishiki V MIC Tanzania Limited, Civil Appeal No.85 of 2019Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Comfort Technological Investment (T) LTD Vs Tanzania Shipping Agencies Corporation (Civil Case No 23 of 2019) 2021 TZHC 6496 (24 September 2021)Document18 pagesComfort Technological Investment (T) LTD Vs Tanzania Shipping Agencies Corporation (Civil Case No 23 of 2019) 2021 TZHC 6496 (24 September 2021)Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts IIDocument7 pagesLaw of Torts IIEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Halima Swalehe CaseDocument12 pagesHalima Swalehe CaseEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Ngwala Kija v. RepublicDocument14 pagesNgwala Kija v. RepublicEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Charles Ndessi CaseDocument14 pagesCharles Ndessi CaseEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Ruling: 2nd & 7th December, 2022Document8 pagesRuling: 2nd & 7th December, 2022Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Mohamed Rashid v. R.Document30 pagesMohamed Rashid v. R.Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Right of Occupancy Cannot Be Extinguished Without Compensation, Whoever Have Title Is The OwnerDocument16 pagesRight of Occupancy Cannot Be Extinguished Without Compensation, Whoever Have Title Is The OwnerEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Nyeura Patrick v. RepublicDocument14 pagesNyeura Patrick v. RepublicEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Revocation of The Right of Occupancy, Illegal Revocation, Burden of Proof Under Civil CaseDocument20 pagesRevocation of The Right of Occupancy, Illegal Revocation, Burden of Proof Under Civil CaseEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Skeleton Lecture Presentation On Confessions in Tanzania-MairoDocument3 pagesSkeleton Lecture Presentation On Confessions in Tanzania-MairoEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Revocation of Right of Occupancy Can Not Dealt Without Prior NoticeDocument20 pagesRevocation of Right of Occupancy Can Not Dealt Without Prior NoticeEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Maige Nkuba v. Republic, 2016Document15 pagesMaige Nkuba v. Republic, 2016Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- R.E 2022 Prevention and Combating of Corruption Act (Cap. 329 R.E 2022) - MD, MendezDocument41 pagesR.E 2022 Prevention and Combating of Corruption Act (Cap. 329 R.E 2022) - MD, MendezEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

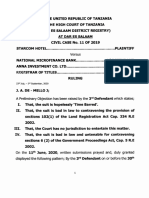

- Starcom Hotel CaseDocument4 pagesStarcom Hotel CaseEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Hammurabi V LMA AssignmentDocument9 pagesHammurabi V LMA AssignmentEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Assignment Land Law One Dr. MussaDocument6 pagesAssignment Land Law One Dr. MussaEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Ndumbaro - Law of Banking by Shafii (Notes)Document121 pagesNdumbaro - Law of Banking by Shafii (Notes)Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Judgment of The Court: 19th September & 5th December, 2022Document16 pagesJudgment of The Court: 19th September & 5th December, 2022Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Judy WakabayashiDocument18 pagesJudy WakabayashizlidjukaNo ratings yet

- Ketan Parekh Scam CaseDocument10 pagesKetan Parekh Scam CaseGavin Lobo100% (1)

- Hcs 608 Assignment 2 - Purvasha SharanDocument13 pagesHcs 608 Assignment 2 - Purvasha Sharanpurvashasharan16No ratings yet

- Motion To Vacate Order of DisbarmentDocument28 pagesMotion To Vacate Order of DisbarmentMark A. Adams JD/MBA100% (3)

- Travelogue ExampleDocument1 pageTravelogue ExampleMary Gold Mosquera EsparteroNo ratings yet

- Cost Sheet TheoryDocument3 pagesCost Sheet TheorySurojit SahaNo ratings yet

- Poem Analysis PresenationDocument8 pagesPoem Analysis PresenationMunachiNo ratings yet

- 5.2 Graphic Spatial Programming: Table No. 12 Space Programming - Administrative BuildingDocument10 pages5.2 Graphic Spatial Programming: Table No. 12 Space Programming - Administrative BuildingSaileneGuemoDellosaNo ratings yet

- Australian Motorcycle News 24.09.2020Document116 pagesAustralian Motorcycle News 24.09.2020autotech master100% (1)

- Classification of MenusDocument12 pagesClassification of Menusliewin langiNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship Competition SPPUDocument2 pagesEntrepreneurship Competition SPPUsjNo ratings yet

- Frias V San Diego SisonDocument5 pagesFrias V San Diego Sisonbrida athenaNo ratings yet

- Hungarian SelftaughtDocument136 pagesHungarian Selftaughtbearinghu100% (11)

- Data Engineer - Insightin Technology BangladeshDocument6 pagesData Engineer - Insightin Technology BangladeshJahidul IslamNo ratings yet

- Civil Litigation 2018Document19 pagesCivil Litigation 2018Markus BisteNo ratings yet

- Shyam Goyal Vs ARG Developers PVT LTD 05012022 RERR20221801221616512COM690517Document3 pagesShyam Goyal Vs ARG Developers PVT LTD 05012022 RERR20221801221616512COM690517sreeram sushanthNo ratings yet

- The Iasb at A CrossroadDocument8 pagesThe Iasb at A Crossroadyahya zafarNo ratings yet

- CollegiumDocument62 pagesCollegiumsymphonybugNo ratings yet

- Reflective EssayDocument5 pagesReflective EssaySergant PororoNo ratings yet

- Justin Jaron Lewis: Divine Gender Transformations in Rebbe Nahman of Bratslav.Document20 pagesJustin Jaron Lewis: Divine Gender Transformations in Rebbe Nahman of Bratslav.jewishstudiesNo ratings yet

- Tubektomi VasektomiDocument60 pagesTubektomi Vasektomibayu indrayana irsyadNo ratings yet

- Qualified Contestable Customers - March 2021 DataDocument61 pagesQualified Contestable Customers - March 2021 DataCarissa May Maloloy-onNo ratings yet

- Project: Building Dormitory For Foreign Students in Vietnam National University, Ha NoiDocument39 pagesProject: Building Dormitory For Foreign Students in Vietnam National University, Ha NoiNguyễn Hoàng TrườngNo ratings yet

- Eviction - answER. To Complaint.2Document9 pagesEviction - answER. To Complaint.2Donald T. GrahnNo ratings yet

- UST Golden Notes 2011 - Persons and Family RelationsDocument88 pagesUST Golden Notes 2011 - Persons and Family RelationsDaley Catugda88% (8)

- ISMS Policy Tcm44-229263Document4 pagesISMS Policy Tcm44-229263klefo100% (1)

- How Do You "Design" A Business Ecosystem?: by Ulrich Pidun, Martin Reeves, and Maximilian SchüsslerDocument18 pagesHow Do You "Design" A Business Ecosystem?: by Ulrich Pidun, Martin Reeves, and Maximilian Schüsslerwang raymondNo ratings yet

- Science, Technology and Society: Maridel Enage Beato Laarni Cemat Maraño LadiaoDocument11 pagesScience, Technology and Society: Maridel Enage Beato Laarni Cemat Maraño LadiaoAdieNo ratings yet

Lock Out Agreement

Lock Out Agreement

Uploaded by

Eldard KafulaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lock Out Agreement

Lock Out Agreement

Uploaded by

Eldard KafulaCopyright:

Available Formats

"Locking out" and "Locking in": The Enforceability of Agreements to Negotiate

Author(s): Edwin Peel

Source: The Cambridge Law Journal , Jul., 1992, Vol. 51, No. 2 (Jul., 1992), pp. 211-213

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of Editorial Committee of the

Cambridge Law Journal

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4507668

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

and Cambridge University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to The Cambridge Law Journal

This content downloaded from

197.250.224.151 on Thu, 04 May 2023 14:35:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

C.L.J. Case and Comment 211

"locking out" and "locking in":

the enforceability of agreements to negotiate

In Walford v. Miles [1992] 2 W.L.R. 174 the

decided upon the enforceability of (1) an agre

good faith with a particular party (a "lock-in")

not to negotiate with any third party (a "lo

confirms that a "lock-in" agreement is unenfo

the necessary certainty" and that a "lock-out"

enforceable in limited circumstances.

In Walford the defendants entered into negotiations with the

plaintiffs for the sale of the defendants' photographic processing

business. Those negotiations were "subject to contract". Anxious not

to lose what they saw as a "bargain", the plaintiffs obtained from

the defendants an oral undertaking that, during negotiations with the

plaintiffs, the defendants would not negotiate with any third party

or consider any alternative offer. In return, the plaintiffs promised

to continue negotiations and to provide a "comfort letter" from their

bankers confirming that they had the finances available to complete

the deal. Ten days later the defendants agreed to sell their business

to a third party and so informed the plaintiffs. The plaintiffs

commenced proceedings for what they claimed was breach of a

collateral agreement not to negotiate with a third party thereby

depriving the plaintiffs of the opportunity to purchase the business.

The plaintiffs were successful at first instance ([1990] 1 E.G.L.R.

212) but the Court of Appeal (Bingham L.J. dissenting) ([1991]

27 E.G. 114 & [1991] 28 E.G. 81) allowed the defendants' appeal.

The House of Lords accepted that the agreement not to negotiate

with a third party was collateral to the principal negotiations and

not, therefore, "subject to contract" and that the promise to provide

a "comfort letter" was valid consideration. On the facts alone the

agreement amounted to a simple "lock-out" since the defendants

only agreed not to negotiate with a third party. However, during

course of the proceedings, the plaintiffs amended their claim

contend that there was also an implied obligation upon the defend

to negotiate with the plaintiffs in good faith. As such, it becam

"lock-in" agreement.

Approving the decision of the Court of Appeal in Courtney a

Fairbairn Ltd. v. Tolaini Brothers (Hotels) Ltd. [1975] 1 W.L.R. 2

Lord Ackner, with whom all of their Lordships agreed, fou

that such an agreement was unenforceable. The courts could

realistically be expected to say when negotiations had broken do

for a "proper reason" as opposed to a failure by one of the part

to negotiate in good faith. He also found that "the concept of a d

to carry on negotiations in good faith is inherently repugnant to

This content downloaded from

197.250.224.151 on Thu, 04 May 2023 14:35:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

212 The Cambridge Law Journal [1992]

adversarial position of the parties when involved in

During the course of his speech Lord Ackner dis

following dictum of Lord Wright in Hillas & Co. Ltd

[1932] 147 L.T. 503, 515:

There is then no bargain except to negotiate, and

may be fruitless and end without any contract ens

then, in strict theory, there is a contract (if

consideration) to negotiate, though in the event of

by one party the damages may be nominal, unless

that the opportunity to negotiate was of some app

to the injured party.

This disapproval by their Lordships is of considerabl

since, in the earlier case of Mallozzi v. Carapelli SpA [

Rep 407, 412, 414 it had been noted by the Court

Lord Wright's observation had been often followed

practitioners and judges of first instance.

Counsel for the plaintiffs had claimed that there w

obligation to negotiate in good faith in order to pre-emp

that, without it, the agreement between the parties w

futile. However, in the Court of Appeal, Bingham L

with the majority's "orthodox view" that a "lock-in"

unenforceable, found that a simple "lock-out" agreem

futile in that it provided the plaintiffs with an "exclusiv

to try and reach an agreement with the defendants. Furt

that such an agreement was enforceable and that the d

in breach.

In the House of Lords, Lord Ackner agreed that there may be

"good commercial reasons" for entering into a "lock-out" agreement

and that such an agreement could be enforced but only if it was for

a fixed period. As no period of time had been stipulated by the

parties Bingham L.J. had held that the defendants' obligation would

"remain binding for such time as is reasonable in the circumstances".

This time would come to an end "once the parties, acting in good

faith, had found themselves unable to come to mutually acceptable

terms" (emphasis added) and not where the defendants had procured

a "bogus impasse" (the defendants claimed that they sold to a third

party because neither they nor their staff were likely to get on with

the plaintiffs as new owners). However, as Bingham L.J. recognised,

this approach was open to the objection that, indirectly, it subjected

the defendants to the very duty to negotiate in good faith which was

rejected as the basis of a "lock-in" agreement. For this reason Lord

Ackner found that a "lock-out" agreement which failed to specify a

particular period during which it was to operate was not enforceable.

In dealing in this way with an agreement which the Court of

This content downloaded from

197.250.224.151 on Thu, 04 May 2023 14:35:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

C.L.J. Case and Comment 213

Appeal

Appealrecognised

recognised

was of

was

a "not

of auncommon

"not uncommon

type" the importance

type" the importance

of

of the

theHouse

Houseof Lords'

of Lords'

decision

decision

should not

should

be underestimated

not be underestimated

(cf. (cf.

Coal

CoalCliff

CliffCollieries

Collieries

Pty. Ltd.

Pty.v.Ltd.

Sijehama

v. Sijehama

Pty. Ltd. [1991]

Pty. Ltd.

24 [1991] 24

N.S.W.L.R.

N.S.W.L.R. 1). 1).

Further,

Further,

if no if

party

no can

party

be obliged

can be to obliged

negotiate to

then

negotiate then

the

thedecision

decisionin Blackpool

in Blackpool

and Fylde

andAero

Fylde

Club

Aero

Ltd. v.

Club

Blackpool

Ltd. v. Blackpoo

Borough

Borough Council

Council[1990]

[1990]

1 W.L.R.

1 W.L.R.

1195 that,

1195

in certain

that, in

circumstances

certain circumstances

(local

(localauthority

authorityinviting

inviting

a limited

a limited

number number

of sealed tenders),

of sealeda party

tenders), a party

may

maybebe obliged

obliged

to "consider"

to "consider"

an offerancould

offer

be called

couldinto

be doubt.

called into doubt.

However,

However, in in

thatthat

case case

there there

was no was

roomnoforroom

negotiation

for negotiation

and the and the

courts

courtsappear

appear

ableable

to determine,

to determine,

with certainty,

with certainty,

whether an whether

offer has an offer has

been

been"considered"

"considered"

if not

ifwhether

not whether

there hasthere

been "negotiation".

has been "negotiation".

EDWIN PEEL.

CONTRACT-IMPLIED TERMS IN STOCK EXCHANGE TRANSACTION

THE reserved judgment of Cole J. of the Supreme Cour

South Wales in FAI Traders Insurance Company Ltd

McCaughan Securities Ltd. (1991) 9 A.C.L.C. 84; (1990

279 again illustrates the important role of the courts in the

of commercial disputes by the implication in a contract

give effect to the presumed intention of the parties.

The case resulted from the failure of settlement of a stock

exchange transaction involving the sale and purchase of shares

plaintiff seller, FAI Traders Insurance Company Ltd., a

company listed on the Australian Stock Exchange, had agr

July 1989 with Fulham Holdings Ltd., another listed public com

("the purchaser") to sell its 12 per cent. holding in Hooker Cor

tion for some $A12m by a "special crossing" on market. (Und

special crossing, the one broker acts for both purchaser and

on terms already agreed between purchaser and seller.) Settle

was to be deferred until December 1989. Before settlement Hooker

went into voluntary liquidation, and as its shares became worthles

the purchaser and the defendant broker purported to cancel the

transaction.

The plaintiff unsuccessfully sued the defendant broker for pay-

ment, alleging the existence of a usage of the stock exchange that a

seller's broker is obliged to pay the seller, whether or not the seller's

broker is paid by the purchaser or the purchaser's broker.

The case also provided answers to the question whether terms

could be implied into the contract between the plaintiff and the

defendant by the incorporation of terms from the contract note (and

through it, the business rules and the listing rules of the stock

exchange).

This content downloaded from

197.250.224.151 on Thu, 04 May 2023 14:35:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- LL Tq4za2016Document3 pagesLL Tq4za2016Law henryNo ratings yet

- Cape Law: Texts and Cases - Contract Law, Tort Law, and Real PropertyFrom EverandCape Law: Texts and Cases - Contract Law, Tort Law, and Real PropertyNo ratings yet

- STAR SHIPPING V CHINA NATIONAL FOREIGN TRADE (Seat Law)Document12 pagesSTAR SHIPPING V CHINA NATIONAL FOREIGN TRADE (Seat Law)Shubham SarkarNo ratings yet

- Oblicon Case Digests (Finals)Document21 pagesOblicon Case Digests (Finals)Ernie Gultiano100% (1)

- GQ Magazine August 2011Document2 pagesGQ Magazine August 2011RamkumarNo ratings yet

- Central London Property Trust LTD V High Trees House Ltd-HighlightedDocument4 pagesCentral London Property Trust LTD V High Trees House Ltd-Highlightedwaffles over pancakes100% (1)

- Law of Contract: FrustrationDocument12 pagesLaw of Contract: FrustrationJ. Angel AiozNo ratings yet

- FrustrationDocument8 pagesFrustrationIan Mual PeterNo ratings yet

- Contract Net NotesDocument7 pagesContract Net NotesdenisNo ratings yet

- Frustration (Notes and Cases)Document6 pagesFrustration (Notes and Cases)Brett SmithNo ratings yet

- Seminário 2 - 10JLegalHist90-1 - FrustrationDocument21 pagesSeminário 2 - 10JLegalHist90-1 - FrustrationMaria Eduarda LessaNo ratings yet

- Terms - Lecture 5Document22 pagesTerms - Lecture 5Lim Kok SeanNo ratings yet

- 9 - Terms Implied by Common LawDocument3 pages9 - Terms Implied by Common LawkennedyopNo ratings yet

- Week 6 Contract ConstructionDocument73 pagesWeek 6 Contract ConstructionLili ChenNo ratings yet

- Consideration CasesDocument22 pagesConsideration CasesMuhaye BridgetNo ratings yet

- Kowloon Development Finance LTD V Pendex Industries LTDDocument9 pagesKowloon Development Finance LTD V Pendex Industries LTDChristopher JayNo ratings yet

- CH 02 LAW 379Document10 pagesCH 02 LAW 379Nur Ariefah SaidNo ratings yet

- THE DOCTRINE OF FRUSTRATION - The Lawyers & JuristsDocument10 pagesTHE DOCTRINE OF FRUSTRATION - The Lawyers & JuristsEddie NyikaNo ratings yet

- Commercial Law Lecture 9Document10 pagesCommercial Law Lecture 9Ismail PatelNo ratings yet

- Week 1 - Agreement (Offer)Document58 pagesWeek 1 - Agreement (Offer)Aronyo DeyNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 Contract Formation ApproachesDocument2 pagesUnit 5 Contract Formation ApproacheslalitNo ratings yet

- Impossibility of Performance - Frustration: by DR Suzi Fadhilah IsmailDocument83 pagesImpossibility of Performance - Frustration: by DR Suzi Fadhilah IsmailNu'man AzhamNo ratings yet

- (2007) EWCA Civ 1329Document17 pages(2007) EWCA Civ 1329fsm20221227No ratings yet

- Ks PPT 1 A 2023 RevisedDocument64 pagesKs PPT 1 A 2023 Revisedninjaalex225No ratings yet

- 1996 - Hedley - C.I.F. Contract. Commercial Arbitration. Acceptance of Anticipatory Breach - Steve HedleyDocument4 pages1996 - Hedley - C.I.F. Contract. Commercial Arbitration. Acceptance of Anticipatory Breach - Steve HedleyJoana VitorinoNo ratings yet

- AgreementDocument57 pagesAgreementSarah DarkoNo ratings yet

- Repudiation, Anticipatory Breach and Conditions in A Contract For ServicesDocument7 pagesRepudiation, Anticipatory Breach and Conditions in A Contract For ServicesYash TiwariNo ratings yet

- 2Document17 pages2Đinesh ĢunasenaNo ratings yet

- Glade Mountain Corp. v. Reconstruction Finance Corp, 200 F.2d 815, 3rd Cir. (1952)Document4 pagesGlade Mountain Corp. v. Reconstruction Finance Corp, 200 F.2d 815, 3rd Cir. (1952)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Contract Formation - Offer and AcceptanceDocument30 pagesContract Formation - Offer and AcceptanceNoor FaraNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Frustration-2022b WeeknedDocument6 pagesDoctrine of Frustration-2022b Weeknedakwasiamoh501No ratings yet

- MistakeDocument13 pagesMistakeBrett SmithNo ratings yet

- Lecture 18 - Discharge by FrustrationDocument6 pagesLecture 18 - Discharge by FrustrationBrett SmithNo ratings yet

- Discharge by FrustrationDocument10 pagesDischarge by FrustrationSylviane Sie Siu MingNo ratings yet

- Red Zone-Cadwalader Wicker Sham Taft LawsuitDocument16 pagesRed Zone-Cadwalader Wicker Sham Taft Lawsuitchris_clair9652No ratings yet

- Contract Law - Offer Acceptance SCDocument42 pagesContract Law - Offer Acceptance SChannushaNo ratings yet

- 4 Certainty and Agreement MistakesDocument9 pages4 Certainty and Agreement Mistakesyonyo90No ratings yet

- The Doctrine of Frustration-1Document24 pagesThe Doctrine of Frustration-1gaurangiNo ratings yet

- Property Exam 2023Document2 pagesProperty Exam 2023marija.kutalovskaja24No ratings yet

- Mistake 1Document10 pagesMistake 1niyiNo ratings yet

- FrustrationDocument12 pagesFrustrationcwangheichanNo ratings yet

- ALL ER 1942 Volume 1Document457 pagesALL ER 1942 Volume 1dpmugambiadvocatesNo ratings yet

- Nova (Jersey) Knit LTD V Kammgarn Spinnerei GMBH, (1977) 2 All Er 463Document7 pagesNova (Jersey) Knit LTD V Kammgarn Spinnerei GMBH, (1977) 2 All Er 463mehalNo ratings yet

- (1952) 2 Q.B. 297Document11 pages(1952) 2 Q.B. 297Joshua ChanNo ratings yet

- Agreement-Contract, Offer-AcceptanceDocument69 pagesAgreement-Contract, Offer-AcceptanceAbhinav PandeyNo ratings yet

- Principle of Business LawDocument14 pagesPrinciple of Business LawMaya DomaNo ratings yet

- Steadman V. Steadman1: NotesDocument5 pagesSteadman V. Steadman1: Notesnkumbunamonje30No ratings yet

- Certainty: BY Mrs SimbotweDocument16 pagesCertainty: BY Mrs SimbotweTremor BandaNo ratings yet

- BusinesslawDocument14 pagesBusinesslawDebangan DasNo ratings yet

- A. Express TermsDocument27 pagesA. Express TermscwangheichanNo ratings yet

- Abdallah 223796 Asg 2 MistakeDocument5 pagesAbdallah 223796 Asg 2 Mistakeabdallahnashaat3No ratings yet

- Cases On Discharge of ContractDocument5 pagesCases On Discharge of ContractVIVEKNo ratings yet

- Howard MarineDocument3 pagesHoward MarineMichael CruzNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - Implied - Express TermsDocument12 pagesChapter 4 - Implied - Express TermssupremeshaktivelNo ratings yet

- Problem Solving CompressDocument21 pagesProblem Solving CompressJaycee HowNo ratings yet

- 06Document21 pages06Huong GiangNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Law240 Law of ContractDocument40 pagesChapter 2 Law240 Law of Contractatyizzaty04No ratings yet

- CIF ContractsDocument18 pagesCIF Contractsceleguk75% (4)

- Koppel Inc. v. Makati Rotary Club FoundationDocument20 pagesKoppel Inc. v. Makati Rotary Club FoundationJoshuaMaulaNo ratings yet

- Performances: Cases On Discharge of ContractDocument5 pagesPerformances: Cases On Discharge of ContractVIVEKNo ratings yet

- Frustration Revision NotesDocument9 pagesFrustration Revision NotesRohin BansalNo ratings yet

- Abdallah Irunde v. Msunga Ntunda & Abeid Msunga, Misc. Civil Appeal No.38 of 2019Document7 pagesAbdallah Irunde v. Msunga Ntunda & Abeid Msunga, Misc. Civil Appeal No.38 of 2019Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Stanbic Bank T Ltd vs Grace Mushi (Revision No 386 of 2015) 2018 TZHCLD 404 (10 May 2018)Document26 pagesStanbic Bank T Ltd vs Grace Mushi (Revision No 386 of 2015) 2018 TZHCLD 404 (10 May 2018)Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- LST Students Dress CodeDocument3 pagesLST Students Dress CodeEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts CaseDocument20 pagesLaw of Torts CaseEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Arsenal Footbal CaseDocument17 pagesArsenal Footbal CaseEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- NHRI Kenya National Commission on HRDocument10 pagesNHRI Kenya National Commission on HREldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Mayamba Mjarifu CaseDocument16 pagesMayamba Mjarifu CaseEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Benard Cosmas Vs Republic (Criminal Appeal 49 of 2021) 2022 TZHC 10780 (26 July 2022)Document11 pagesBenard Cosmas Vs Republic (Criminal Appeal 49 of 2021) 2022 TZHC 10780 (26 July 2022)Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Intellectual PropertyDocument22 pagesIntellectual PropertyEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Bakhresa CaseDocument12 pagesBakhresa CaseEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Nurdin Mohamed Ahmed at Sheikh Kishiki V MIC Tanzania Limited, Civil Appeal No.85 of 2019Document22 pagesNurdin Mohamed Ahmed at Sheikh Kishiki V MIC Tanzania Limited, Civil Appeal No.85 of 2019Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Comfort Technological Investment (T) LTD Vs Tanzania Shipping Agencies Corporation (Civil Case No 23 of 2019) 2021 TZHC 6496 (24 September 2021)Document18 pagesComfort Technological Investment (T) LTD Vs Tanzania Shipping Agencies Corporation (Civil Case No 23 of 2019) 2021 TZHC 6496 (24 September 2021)Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts IIDocument7 pagesLaw of Torts IIEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Halima Swalehe CaseDocument12 pagesHalima Swalehe CaseEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Ngwala Kija v. RepublicDocument14 pagesNgwala Kija v. RepublicEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Charles Ndessi CaseDocument14 pagesCharles Ndessi CaseEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Ruling: 2nd & 7th December, 2022Document8 pagesRuling: 2nd & 7th December, 2022Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Mohamed Rashid v. R.Document30 pagesMohamed Rashid v. R.Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Right of Occupancy Cannot Be Extinguished Without Compensation, Whoever Have Title Is The OwnerDocument16 pagesRight of Occupancy Cannot Be Extinguished Without Compensation, Whoever Have Title Is The OwnerEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Nyeura Patrick v. RepublicDocument14 pagesNyeura Patrick v. RepublicEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Revocation of The Right of Occupancy, Illegal Revocation, Burden of Proof Under Civil CaseDocument20 pagesRevocation of The Right of Occupancy, Illegal Revocation, Burden of Proof Under Civil CaseEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Skeleton Lecture Presentation On Confessions in Tanzania-MairoDocument3 pagesSkeleton Lecture Presentation On Confessions in Tanzania-MairoEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Revocation of Right of Occupancy Can Not Dealt Without Prior NoticeDocument20 pagesRevocation of Right of Occupancy Can Not Dealt Without Prior NoticeEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Maige Nkuba v. Republic, 2016Document15 pagesMaige Nkuba v. Republic, 2016Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- R.E 2022 Prevention and Combating of Corruption Act (Cap. 329 R.E 2022) - MD, MendezDocument41 pagesR.E 2022 Prevention and Combating of Corruption Act (Cap. 329 R.E 2022) - MD, MendezEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Starcom Hotel CaseDocument4 pagesStarcom Hotel CaseEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Hammurabi V LMA AssignmentDocument9 pagesHammurabi V LMA AssignmentEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Assignment Land Law One Dr. MussaDocument6 pagesAssignment Land Law One Dr. MussaEldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Ndumbaro - Law of Banking by Shafii (Notes)Document121 pagesNdumbaro - Law of Banking by Shafii (Notes)Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Judgment of The Court: 19th September & 5th December, 2022Document16 pagesJudgment of The Court: 19th September & 5th December, 2022Eldard KafulaNo ratings yet

- Judy WakabayashiDocument18 pagesJudy WakabayashizlidjukaNo ratings yet

- Ketan Parekh Scam CaseDocument10 pagesKetan Parekh Scam CaseGavin Lobo100% (1)

- Hcs 608 Assignment 2 - Purvasha SharanDocument13 pagesHcs 608 Assignment 2 - Purvasha Sharanpurvashasharan16No ratings yet

- Motion To Vacate Order of DisbarmentDocument28 pagesMotion To Vacate Order of DisbarmentMark A. Adams JD/MBA100% (3)

- Travelogue ExampleDocument1 pageTravelogue ExampleMary Gold Mosquera EsparteroNo ratings yet

- Cost Sheet TheoryDocument3 pagesCost Sheet TheorySurojit SahaNo ratings yet

- Poem Analysis PresenationDocument8 pagesPoem Analysis PresenationMunachiNo ratings yet

- 5.2 Graphic Spatial Programming: Table No. 12 Space Programming - Administrative BuildingDocument10 pages5.2 Graphic Spatial Programming: Table No. 12 Space Programming - Administrative BuildingSaileneGuemoDellosaNo ratings yet

- Australian Motorcycle News 24.09.2020Document116 pagesAustralian Motorcycle News 24.09.2020autotech master100% (1)

- Classification of MenusDocument12 pagesClassification of Menusliewin langiNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship Competition SPPUDocument2 pagesEntrepreneurship Competition SPPUsjNo ratings yet

- Frias V San Diego SisonDocument5 pagesFrias V San Diego Sisonbrida athenaNo ratings yet

- Hungarian SelftaughtDocument136 pagesHungarian Selftaughtbearinghu100% (11)

- Data Engineer - Insightin Technology BangladeshDocument6 pagesData Engineer - Insightin Technology BangladeshJahidul IslamNo ratings yet

- Civil Litigation 2018Document19 pagesCivil Litigation 2018Markus BisteNo ratings yet

- Shyam Goyal Vs ARG Developers PVT LTD 05012022 RERR20221801221616512COM690517Document3 pagesShyam Goyal Vs ARG Developers PVT LTD 05012022 RERR20221801221616512COM690517sreeram sushanthNo ratings yet

- The Iasb at A CrossroadDocument8 pagesThe Iasb at A Crossroadyahya zafarNo ratings yet

- CollegiumDocument62 pagesCollegiumsymphonybugNo ratings yet

- Reflective EssayDocument5 pagesReflective EssaySergant PororoNo ratings yet

- Justin Jaron Lewis: Divine Gender Transformations in Rebbe Nahman of Bratslav.Document20 pagesJustin Jaron Lewis: Divine Gender Transformations in Rebbe Nahman of Bratslav.jewishstudiesNo ratings yet

- Tubektomi VasektomiDocument60 pagesTubektomi Vasektomibayu indrayana irsyadNo ratings yet

- Qualified Contestable Customers - March 2021 DataDocument61 pagesQualified Contestable Customers - March 2021 DataCarissa May Maloloy-onNo ratings yet

- Project: Building Dormitory For Foreign Students in Vietnam National University, Ha NoiDocument39 pagesProject: Building Dormitory For Foreign Students in Vietnam National University, Ha NoiNguyễn Hoàng TrườngNo ratings yet

- Eviction - answER. To Complaint.2Document9 pagesEviction - answER. To Complaint.2Donald T. GrahnNo ratings yet

- UST Golden Notes 2011 - Persons and Family RelationsDocument88 pagesUST Golden Notes 2011 - Persons and Family RelationsDaley Catugda88% (8)

- ISMS Policy Tcm44-229263Document4 pagesISMS Policy Tcm44-229263klefo100% (1)

- How Do You "Design" A Business Ecosystem?: by Ulrich Pidun, Martin Reeves, and Maximilian SchüsslerDocument18 pagesHow Do You "Design" A Business Ecosystem?: by Ulrich Pidun, Martin Reeves, and Maximilian Schüsslerwang raymondNo ratings yet

- Science, Technology and Society: Maridel Enage Beato Laarni Cemat Maraño LadiaoDocument11 pagesScience, Technology and Society: Maridel Enage Beato Laarni Cemat Maraño LadiaoAdieNo ratings yet