Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Periop Risk Scoring

Periop Risk Scoring

Uploaded by

Mabelis EstherCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- GREAT WRITING 1: Great Sentences For Great Paragraphs: Unit 1 Sentence BasicsDocument19 pagesGREAT WRITING 1: Great Sentences For Great Paragraphs: Unit 1 Sentence Basicssara90% (30)

- Preoperative Evaluation in The 21st CenturyDocument13 pagesPreoperative Evaluation in The 21st CenturyPaulHerrera0% (1)

- Chak de India Management Perspective ProjectDocument21 pagesChak de India Management Perspective ProjectMr. Umang PanchalNo ratings yet

- 4 Roadtec 600 Cummins QSXDocument24 pages4 Roadtec 600 Cummins QSXdavidNo ratings yet

- Hell Bent: Reading Group GuideDocument5 pagesHell Bent: Reading Group GuideKiran KumarNo ratings yet

- Giraffe Blood CirculationDocument9 pagesGiraffe Blood Circulationthalita asriandinaNo ratings yet

- Credit Policy Sample: Accounts Receivable AnalysisDocument3 pagesCredit Policy Sample: Accounts Receivable AnalysisAlinaNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Risk Stratification and ModificationDocument23 pagesPerioperative Risk Stratification and ModificationDianita P Ñáñez VaronaNo ratings yet

- CC 11904Document8 pagesCC 11904ikjaya3110No ratings yet

- Pre-Operative Risk Assessment PostDocument2 pagesPre-Operative Risk Assessment Postapi-405667642No ratings yet

- Preoperative Assessment of The Risk For Multiple Complications After SurgeryDocument10 pagesPreoperative Assessment of The Risk For Multiple Complications After SurgerylaisNo ratings yet

- Critical Care After Major Surgery A Systematic Review of Risk Factors Unplanned Admission - Onwochei UK 2020Document13 pagesCritical Care After Major Surgery A Systematic Review of Risk Factors Unplanned Admission - Onwochei UK 2020Fransisca Dewi KumalaNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0741521416001579Document8 pagesPi Is 0741521416001579Dr-Rabia AlmamalookNo ratings yet

- Development and Validation of A Preoperative Scoring System To Predict 30 Day Mortality in Patients Undergoing Hip Fracture SurgeryDocument7 pagesDevelopment and Validation of A Preoperative Scoring System To Predict 30 Day Mortality in Patients Undergoing Hip Fracture Surgeryuhs888No ratings yet

- Pillai2016 PDFDocument35 pagesPillai2016 PDFmehak malhotraNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Identification of Neurosurgery Patients With A High Risk of In-Hospital Complications: A Prospective Cohort of 418 Consecutive Elective Craniotomy PatientsDocument11 pagesPreoperative Identification of Neurosurgery Patients With A High Risk of In-Hospital Complications: A Prospective Cohort of 418 Consecutive Elective Craniotomy PatientsAzizi AlfyanNo ratings yet

- Apgar LansiaDocument7 pagesApgar Lansiawispa handayaniNo ratings yet

- 1 S PSCDocument8 pages1 S PSCKen WonNo ratings yet

- Pub 2Document6 pagesPub 2Shreyas KateNo ratings yet

- Evaluacion Pulmonar PreoperatoriaDocument15 pagesEvaluacion Pulmonar Preoperatorialuis castillejosNo ratings yet

- What's New in Perioperative Cardiac TestingDocument17 pagesWhat's New in Perioperative Cardiac TestingCamilo HernándezNo ratings yet

- Clinical Neurology and NeurosurgeryDocument5 pagesClinical Neurology and NeurosurgeryRina NovitrianiNo ratings yet

- J NeuroIntervent Surg 2013 González Neurintsurg 2013 010715Document7 pagesJ NeuroIntervent Surg 2013 González Neurintsurg 2013 010715Rogério HitsugayaNo ratings yet

- News LeeDocument5 pagesNews LeeNurdinNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0748798321006429Document10 pagesPi Is 0748798321006429diego fernando olivera briñezNo ratings yet

- 2 Art Ingles IJA-67-39Document9 pages2 Art Ingles IJA-67-39Vanesa Osco SilloNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment POD2023Document10 pagesRisk Assessment POD2023Cláudia Regina FernandesNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0002961017313697 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0002961017313697 MainWialda Dwi rodyahNo ratings yet

- Surgical Risk Preoperative Assessment System (SURPAS)Document7 pagesSurgical Risk Preoperative Assessment System (SURPAS)Guilherme AnacletoNo ratings yet

- World Neurosurg 2021 Apr 2 Camino-Willhuber GDocument6 pagesWorld Neurosurg 2021 Apr 2 Camino-Willhuber GFernando SousaNo ratings yet

- CC 11396Document12 pagesCC 11396Dhavala Shree B JainNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia For Major Urological SurgeryDocument23 pagesAnaesthesia For Major Urological SurgeryDianita P Ñáñez VaronaNo ratings yet

- Critical Care Considerations in Trauma - Overview, Trauma Systems, Initial Assessment PDFDocument19 pagesCritical Care Considerations in Trauma - Overview, Trauma Systems, Initial Assessment PDFPaulina Jiménez JáureguiNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Cardiac Risk AssessmentDocument16 pagesPreoperative Cardiac Risk Assessmentkrysmelis MateoNo ratings yet

- Aen 314Document3 pagesAen 314ReddyNo ratings yet

- RMMJ 9 1 E0004Document8 pagesRMMJ 9 1 E0004Marisa Archila G.No ratings yet

- 2016 - Preoperative Assessment of Geriatric PatientsDocument13 pages2016 - Preoperative Assessment of Geriatric PatientsruthchristinawibowoNo ratings yet

- Prospective External Validation of A Predictive Score For Postoperative Pulmonary ComplicationDocument13 pagesProspective External Validation of A Predictive Score For Postoperative Pulmonary ComplicationAthziri GallardoNo ratings yet

- Cervical Angiograms in Cervical Spine Trauma Patients 5 Years After The Data: Has Practice Changed?Document4 pagesCervical Angiograms in Cervical Spine Trauma Patients 5 Years After The Data: Has Practice Changed?edi_wsNo ratings yet

- Machine Learning Based Models To Support Decision Maki - 2021 - International JoDocument7 pagesMachine Learning Based Models To Support Decision Maki - 2021 - International JobasubuetNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment For Major Adverse CardiovascularDocument11 pagesRisk Assessment For Major Adverse CardiovascularjdjhdNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0300957218309092 Main PDFDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0300957218309092 Main PDFBirhanu MuletaNo ratings yet

- World Journal of Emergency Surgery: Preventable Trauma Deaths: From Panel Review To Population Based-StudiesDocument7 pagesWorld Journal of Emergency Surgery: Preventable Trauma Deaths: From Panel Review To Population Based-StudiesRita RangelNo ratings yet

- Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health: Loai Abu SharourDocument5 pagesClinical Epidemiology and Global Health: Loai Abu SharourDevia YuliaNo ratings yet

- Predicting 30-DayMortality For PatientsWith AcuteHeart Failure in The EmergencyDepartmentDocument14 pagesPredicting 30-DayMortality For PatientsWith AcuteHeart Failure in The EmergencyDepartmentRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Postanaesthetic Care Unit: Review Open AccessDocument7 pagesIntroduction To The Postanaesthetic Care Unit: Review Open AccessSamsul BahriNo ratings yet

- Diagnostics: A Machine-Learning-Based Prediction Method For Hypertension Outcomes Based On Medical DataDocument21 pagesDiagnostics: A Machine-Learning-Based Prediction Method For Hypertension Outcomes Based On Medical DatafarzanaNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors and Associated Complications With Unplanned Intubation in Patients With Craniotomy For Brain Tumor.Document5 pagesRisk Factors and Associated Complications With Unplanned Intubation in Patients With Craniotomy For Brain Tumor.49hr84j7spNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s11605 019 04424 5Document8 pages10.1007@s11605 019 04424 5Rika Sartyca IlhamNo ratings yet

- An Evidence Based Blunt Trauma ProtocolDocument7 pagesAn Evidence Based Blunt Trauma ProtocolPepe pepe pepeNo ratings yet

- Clinical Diagnosis of Uncomplicated, Acute Appendicitis Remains An Imperfect ScienceDocument3 pagesClinical Diagnosis of Uncomplicated, Acute Appendicitis Remains An Imperfect ScienceHector ReinozoNo ratings yet

- PIIS0007091219309298Document10 pagesPIIS0007091219309298Anca OuatuNo ratings yet

- GUIDELINE For IMPROVING OUTCOME After Anaesthesia and Critical Care - 2017 - College of AnaesthesiologistsDocument83 pagesGUIDELINE For IMPROVING OUTCOME After Anaesthesia and Critical Care - 2017 - College of AnaesthesiologistsSanj.etcNo ratings yet

- Hypertension Arterielle 2016Document5 pagesHypertension Arterielle 2016Nabil YahioucheNo ratings yet

- Causes and Predictors of 30-Day Readmission After Shoulder and Knee Arthroscopy: An Analysis of 15,167 CasesDocument7 pagesCauses and Predictors of 30-Day Readmission After Shoulder and Knee Arthroscopy: An Analysis of 15,167 CasesSuzzy57No ratings yet

- Why Thromboprophylaxis Fails Final VDM - 47-51Document5 pagesWhy Thromboprophylaxis Fails Final VDM - 47-51Ngô Khánh HuyềnNo ratings yet

- 2017 Article 168Document15 pages2017 Article 168Rui Pedro PereiraNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Pulmonary Outcomes With OsaDocument9 pagesPerioperative Pulmonary Outcomes With OsawandapandabebeNo ratings yet

- Predictors Post Op VentilationDocument48 pagesPredictors Post Op VentilationMuhammad Azam Mohd NizaNo ratings yet

- CRD42017060841Document5 pagesCRD42017060841Florin AchimNo ratings yet

- Prevencion Del Tev en NeurocirugiaDocument15 pagesPrevencion Del Tev en NeurocirugiaRicardo GarciaNo ratings yet

- NON CARDIAC SURGERY. ESC POCKET GLS.2022. Larger FontDocument63 pagesNON CARDIAC SURGERY. ESC POCKET GLS.2022. Larger FontGeoNo ratings yet

- European Guidelines On Perioperative Venous.11Document5 pagesEuropean Guidelines On Perioperative Venous.11ionut.andruscaNo ratings yet

- A Randomized Controlled Trial of Endovascular Aneurysm Repair Versus Open Surgery For Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms in Low - To Moderate-Risk PatientsDocument8 pagesA Randomized Controlled Trial of Endovascular Aneurysm Repair Versus Open Surgery For Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms in Low - To Moderate-Risk Patientsvfd08051996No ratings yet

- PIIS0022480422004036Document6 pagesPIIS0022480422004036Lucas SCaNo ratings yet

- Community Capstone Health Policy PaperDocument17 pagesCommunity Capstone Health Policy Paperapi-417446716No ratings yet

- Eugenio Ochoa GonzalezDocument3 pagesEugenio Ochoa GonzalezEugenio Ochoa GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Industrial Crops & ProductsDocument10 pagesIndustrial Crops & ProductsShield YggdrasilNo ratings yet

- JOSE R. CATACUTAN, Petitioner, vs. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Respondent FactsDocument2 pagesJOSE R. CATACUTAN, Petitioner, vs. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Respondent FactsAngela Marie AlmalbisNo ratings yet

- MR - Tushar Thombare Resume PDFDocument3 pagesMR - Tushar Thombare Resume PDFprasadNo ratings yet

- Hypertensive Patients Knowledge, Self-Care ManagementDocument10 pagesHypertensive Patients Knowledge, Self-Care ManagementLilian ArthoNo ratings yet

- TRANSITIONS 5 WebDocument40 pagesTRANSITIONS 5 WebCARDONA CHANG Micaela AlessandraNo ratings yet

- 1) What Is Budgetary Control?Document6 pages1) What Is Budgetary Control?abhiayushNo ratings yet

- Week 5 Spain & The ReconquistaDocument6 pagesWeek 5 Spain & The ReconquistaABigRedMonsterNo ratings yet

- Lu PDFDocument34 pagesLu PDFAlexanderNo ratings yet

- Fesco Online BillDocument2 pagesFesco Online BillFaisal NaveedNo ratings yet

- Soft Cheese-Like Product Development Enriched With Soy ProteinDocument9 pagesSoft Cheese-Like Product Development Enriched With Soy ProteinJorge RamirezNo ratings yet

- World Psychiatry - 2024 - Schramm - Algorithm Based Modular Psychotherapy Vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For PatientsDocument10 pagesWorld Psychiatry - 2024 - Schramm - Algorithm Based Modular Psychotherapy Vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For PatientsRodrigo HerNo ratings yet

- Road Slope Protection and Flood Control Pow Template Rev. 9Document183 pagesRoad Slope Protection and Flood Control Pow Template Rev. 9Christian Jahweh Sarvida SabadoNo ratings yet

- IVF STUDY For Case StudyDocument3 pagesIVF STUDY For Case StudygremlinnakuNo ratings yet

- Order Form Dedicated Internet Local: Customer InformationDocument5 pagesOrder Form Dedicated Internet Local: Customer InformationtejoajaaNo ratings yet

- CarouselDocument4 pagesCarouselI am JezzNo ratings yet

- Kunci Gitar Bruno Mars - Talking To The Moon Chord Dasar ©Document5 pagesKunci Gitar Bruno Mars - Talking To The Moon Chord Dasar ©eppypurnamaNo ratings yet

- !why Is My Spaghetti Sauce Always Bland and Boring - CookingDocument1 page!why Is My Spaghetti Sauce Always Bland and Boring - CookingathanasiusNo ratings yet

- 2021-07-02 RCF Presentation On NG RS For KSR Ver-0-RGDocument31 pages2021-07-02 RCF Presentation On NG RS For KSR Ver-0-RGDesign RCFNo ratings yet

- 2volt Powerstack BatteriesDocument4 pages2volt Powerstack BatteriesYasirNo ratings yet

- Sooceal ProjectDocument40 pagesSooceal ProjectSushil ShresthaNo ratings yet

- Professional English 1: WEB 20202 Ms Noorhayati SaharuddinDocument20 pagesProfessional English 1: WEB 20202 Ms Noorhayati SaharuddinAdellNo ratings yet

- Mathematics Grade 10Document270 pagesMathematics Grade 10TammanurRaviNo ratings yet

Periop Risk Scoring

Periop Risk Scoring

Uploaded by

Mabelis EstherOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Periop Risk Scoring

Periop Risk Scoring

Uploaded by

Mabelis EstherCopyright:

Available Formats

INTENSIVE CARE Tutorial 343

Perioperative risk prediction scores

Dr. Maria Chereshneva and Dr. Ximena Watson

Anaesthetic Registrars, Croydon University Hospital, UK

Dr. Mark Hamilton

Anaesthetic Consultant, St Georges Hospital, UK

Edited by

Dr. Harjot Singh

Correspondence to atotw@wfsahq.org 13th Dec 2016

QUESTIONS

Before continuing, try to answer the following questions. The answers can be found at the end of the article, together

with an explanation. Please answer True or False:

1. Regarding risk prediction tools:

a. They are routinely used

b. Clinical judgement alone is enough to predict patients’ outcomes after surgery

c. Can be used across all patient populations

d. Should be well validated

e. Accurately predict post discharge outcomes

2. Regarding specific risk prediction tools:

a. APACHE score uses three patient related categories (pre-existing disease, patient reserve and severity of

acute illness) to predict outcomes

b. V-POSSUM is commonly used to predict complications in high-risk patients undergoing vascular surgery

c. The Child-Turcotte-Pugh is more accurate than the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease in predicting

perioperative mortality in patients undergoing liver transplant surgery

d. Objective functional assessment method is currently used routinely to assess high-risk patients undergoing

major surgery

e. There is no specific risk prediction tool for heart valve surgery

3. Regarding patient specific risk assessment:

a. The American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) physical status (PS) classification is the most widely

used system to provide risk assessment for anaesthesia and surgery

b. When predicting the likelihood of perioperative kidney injury, seven independent risk factors have been

identified

c. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing is applicable to all types of surgery

d. Revised cardiac risk index can be used to predict different perioperative complications

e. When predicting respiratory complications: most of the factors identified as predictors for developing

pneumonia are also significant in predicting development of respiratory failure

Key Points INTRODUCTION

• Risk prediction systems use multiple patient

specific variables and mathematical models In the UK, the first report by the National Emergency Laparotomy

calibrated against large data sets to provide Audit (NELA), published in June 2015, highlighted the fact that

quantitative assessment of risk patients, who were not risk assessed prior to surgery, did not receive

1

the required standard of care . The report also emphasised that risk

• Accurate risk prediction allows identification

documentation helps patients and their families to appreciate the

of high risk patients and improves decision

making including allocation of critical care

implications of surgery and helps multi-disciplinary decision-making.

resources It has been shown that whilst clinical judgement is important, alone it

2

is not enough to predict adverse outcomes postoperatively .

• Risk stratification should be routinely Therefore, a variety of risk prediction tools have been developed to

documented for high risk patients identify high risk patients. These tools include exercise testing,

• No risk stratification tool fulfils all the biomarkers assays and risk stratification calculators. However, as

characteristics of an ideal scoring system exercise testing is not routinely available and biomarkers assays are

and should be used bearing in mind their still in their infancy, risk stratification tools allow rapid assessment of

limitations these patients.

Subscribe to ATOTW tutorials by visiting www.wfsahq.org/resources/anaesthesia-tutorial-of-the-week

th

ATOTW 343 – Perioperative risk prediction scores (13 Dec 2016) Page 1 of 7

As well as assessing patients, scoring systems have been used to stratify or compare baseline characteristics in clinical

trials. They have also been used to compare observed and expected outcomes for surgeons, different centres, regions

and have been used to track performances.

There are different scoring systems available, which can be broadly categorised into surgery specific and patient specific

risk scoring tools. The ideal scoring system should fulfil the following criteria:

• Uses routinely available patient characteristics/variables

• Easily accessible

• Extensively validated in different populations

• Applicable to different patient populations and across demographics

• Able to accurately predict post-operative outcomes including after discharge, having both a high sensitivity and

specificity

No risk prediction system currently satisfies all the above criteria.

RISK ASSESSMENT

The goal of risk assessment is to quantify risk for patients undergoing surgery to enable clinical decision-making,

including postoperative care and discussion of risk with the patient and surgeon. Preoperative risk assessment starts by

identifying the type of surgery that is going to be performed and the characteristic of a patient that will have it. These two

factors will determine the risk of complications – a patient with several co-morbidities is at a relatively low risk (<1%) of

developing major adverse cardiac events from cataract surgery; on the other hand, a patient without co-morbidities is at

a relatively high risk (>5%) if undergoing major surgery such as aortic repair. Figure 1 demonstrates the surgery specific

risk according to which type of surgery the patient is having.

Low risk surgery Intermediate risk surgery High risk surgery

Cardiac risk <1% Cardiac risk <5% Cardiac risk >5%

Ophthalmological surgery Major intra-abdominal (non Aortic repair (aneurysmal,

vascular) dissection)

Minor head and neck Intra-thoracic (non-endoscopic) Non-carotid major vascular

Biopsies and superficial procedures Major orthopaedic Peripheral vascular surgery

Minor prostate operations (e.g. Major head and neck Major emergency procedures

cystoscopy)

Radical prostatectomy Prolonged procedures with large

fluid shifts/blood loss

Figure 1. Surgery specific risk

SURGERY SPECIFIC RISK STRTIFICATION SCORES

Below is the description of different risk prediction scores currently used for different types of surgery.

General surgery

Since the NELA report publication, risk prediction tools such as the Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the

enUmeration of Mortality and Morbidity (POSSUM), specifically Portsmouth (P)- POSSUM have been adopted to risk

3

stratify high risk patients in many centres . P-POSSUM is designed to calculate the risk preoperatively. Other similar

4

scores such as the Surgical Outcome Risk Tool (SORT) , the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality

5

Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) and the widely used ICU scoring system Acute Physiology and Chronic Health

6

Evaluation (APACHE II) score have also been adopted . APACHE score is calculated post-operatively. Figure 2

summarises the pros and cons of these risk prediction tools.

Cardiac surgery

The most commonly used risk prediction score in cardiac surgery in the UK is the European System for Cardiac

7

Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) . This was developed in the late 1990s and it provides a robust assessment,

which can be readily calculated at the bedside for patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). The

score is based on 17 clinical characteristics from three categories (patient factors/cardiac-related factors/operative

related factors), each weighted accordingly. The EuroSCORE has been validated in the UK, Europe and North America

and has been shown to be accurate in predicting major complications. There are two models of calculations- the simple

8

additive EuroSCORE and the full logistic EuroSCORE . The latter has been shown to provide a more accurate prediction

for high risk patients. However, since 2011, both the additive and logistic scores have been replaced by the more

9

accurate EuroSCORE II . The EuroSCORE II is based on 18 clinical characteristics.

10

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons mortality risk score (STS) is the other risk stratification system that is currently used

in cardiac surgery and was developed using the data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons database of patients

undergoing cardiac surgery in USA. The STS score uses of over 40 clinical parameters to calculate the mortality figure.

Subscribe to ATOTW tutorials by visiting www.wfsahq.org/resources/anaesthesia-tutorial-of-the-week

th

ATOTW 343 – Perioperative risk prediction scores (13 Dec 2016) Page 2 of 7

From the literature, both EuroScore and STS score appear to be on par in predicting post-operative mortality, however,

EuroScore is more commonly used in UK.

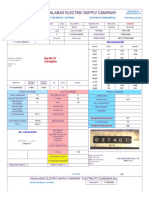

Risk prediction tool Description Advantages Disadvantages

APACHE II 12 variables measured over Well known Designed for critical care, not

first 24 hours for perioperative use

• Physiological indices

Individual risk of Requires multiple variables

• Co-morbidities

morbidity and mortality and data entries entered over

• Type of admission first 24hrs of admission

POSSUM 12 physiological and 6 Best known Problems with over and

operative variables Well validated underestimation of mortality

SORT Six preoperative variables Easy and quick to use New tool therefore no

• Type of surgery external validation

• Urgency of surgery

Not patient specific, only

• ASA of the patient provides general risk of

UK developed system procedure

ACS NSQIP Surgical 21 pre-operative risk factors Patient specific risks Does not account for urgency

Risk Calculator of procedure

Not widely publicised

Not validated for emergency

surgery

Figure 2. Comparison of risk prediction systems for patients undergoing general surgery

Heart valve surgery

Heart valve surgery is the second most common type of cardiac surgery. Although, both the EuroScore and STS score

can be used to calculate the mortality for heart valve surgery as well, a specific risk stratification model for aortic and/or

11

mitral valve with or without concomitant CABG has been developed. The so-called Ambler score has been developed

specifically to calculate in-hospital mortality for patients undergoing heart valve surgery. This model was developed in the

UK using the national database and included over 32000 patients to develop and validate this risk stratification system.

Vascular Surgery

Vascular-POSSUM has been developed in order to facilitate risk prediction of hospital mortality in patients undergoing

major vascular surgery. It has been developed by the Vascular Surgical Society of Great Britain and Ireland, where the

original POSSUM mortality regression equation was modified to produce a regression equation (V-POSSUM) that can be

specifically used in major vascular surgery. During the development and validation of this tool it was found that V-

POSSUM score did overestimate the predicted mortality. Although, it is uncommonly used it is still a specific risk tool

available for this type of surgery.

PATIETN SPECIFIC RISK STRATIFICATION SCORES

The second part of the risk equation is influenced by the patient’s health. The American Society of Anaesthesiologists

(ASA) physical status (PS) classification gives a global impression of the clinical state of the patient that correlates with

post-operative outcomes. It was originally developed in 1941 in the attempt to provide a basis for comparing anaesthesia

12

statistical data . However, it is now the most widely used system to provide risk assessment of anaesthesia and

13

surgery. The different ASA classes have been shown to be good predictors of mortality and it has also been shown that

14

post-operative morbidity also varies with different ASA class . In addition to having a global assessment, specific traits

have been identified that may predispose patients to poor post-operative outcomes and the most common of these are

discussed below.

Cardiac risk assessment

Cardiac risk is the most studied complication of surgery. The well-known and widely used risk prediction tool is the

15

Revised Cardiac Risk Index . Six independent risk factors were identified but rather than weighting each of these

factors, the authors designated risk classes by the number of risk factors (Figure 3). Patents without any risk factors are

assigned the lowest risk class (I), while those with three or more are assigned to the highest risk class (IV). The revised

cardiac risk index is a simple and well-validated system; however, it can only be used to predict major cardiac

complication risk after non-cardiac surgery.

Respiratory risk assessment

Pulmonary function is greatly affected in patients undergoing surgery. Pulmonary complications are common after

surgery and result in significant morbidity post-operatively. Unlike cardiac risk prediction, there are currently no validated

models of pulmonary risk stratification. However, the American College of Physicians have adopted several scales for

Subscribe to ATOTW tutorials by visiting www.wfsahq.org/resources/anaesthesia-tutorial-of-the-week

th

ATOTW 343 – Perioperative risk prediction scores (13 Dec 2016) Page 3 of 7

16

assessing the risk of developing specific respiratory complications such as acute respiratory failure (Figure 4) and

16

pneumonia (Figure 5) .

17,18

These scales were composed from two cohort studies by Arozullah and colleagues . These cohort studies were

conducted at separate time using the patient data from the department of Veterans Affairs NSQUIP. Authors analysed

the data of patients who underwent a variety of surgical non-cardiac procedures, including lung resections. Transplant

surgeries were not included. The data was analysed using logistic regression model and variables that were

independently related to outcomes were used to develop the two systems. To produce the scores, each variable was

assigned a value depending on the regression coefficients with higher values being more significant in determining

outcomes. The type of surgery was the most significant predictor in both developing both postoperative respiratory failure

and pneumonia. Most of the factors identified as predictors for developing pneumonia were also significant in predicting

development of respiratory failure.

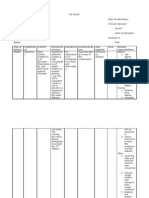

Independent predictors of postoperative complications

High risk surgery Risk Number of risk Risk of major

History of ischemic heart disease class factors complications

History of congestive cardiac failure I 0 0.4%

Insulin therapy for diabetes II 1 0.9%

History of cerebrovascular disease III 2 7.0%

Pre-operative serum creatinine >2.0mg/dl (176.8µmol/L) IV 3 or more 11%

Figure 3. Revised cardiac index

Risk factor Score

Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair 27

Thoracic 14

Upper abdominal, peripheral vascular or neurosurgery 21

Neck 11

Emergency surgery 11

−1

Albumin <3.0 mg dL 9 Class Score %Risk

−1

Plasma urea >30 mg dL 8 1 ≤10 0.5

Totally or partly dependent functional status 7 2 11–19 1.8

COPD 6 3 20–27 4.2

Age ≥70 years 6 4 28–40 10.1

Age 60–69 years 4 5 ≥40 26.6

Figure 4. Risk factors for acute respiratory failure in postoperative period of general non-cardiac surgery.

Risk factor Score

Type of surgery

Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair 15

High thoracic 14

High abdominal 10

Neck or neurosurgery 08

Vascular 03

Age (years)

≥80 17

70–79 13

60–69 09

50–59 04

Functional status

Totally dependent 10

Partially dependent 6

Weight loss over 10% in the last 6 months 7

COPD 5 Class Score %Risk

General anaesthesia 4

Altered sensorium 4 1 0–15 0.24

Prior stroke 4 2 16–25 1.2

Urea (mg dL−1) 3 26–40 4.0

<8 4 4 41–55 9.4

22–30 2

5 >55 15.8

≥30 3

Blood transfusion greater than 4 units 3

Emergency surgery 3

Chronic use of corticosteroids 3

Smoking in the last year 3 Figure 5. Risk factors for postoperative pneumonia in

Alcohol intake >2 doses in the previous 2 weeks 2 general non-cardiac surgery

Subscribe to ATOTW tutorials by visiting www.wfsahq.org/resources/anaesthesia-tutorial-of-the-week

th

ATOTW 343 – Perioperative risk prediction scores (13 Dec 2016) Page 4 of 7

Perioperative kidney injury risk assessment

Acute kidney injury is associated with increased length of stay, cost, morbidity and mortality. The seven independent risk

factors were identified by a single centre prospective study that included over 15000 patients with normal renal function,

19

who underwent non-cardiac surgery . These were: age >59, emergency surgery, chronic liver disease, BMI >32, high

risk surgery, peripheral vascular disease and COPD needing bronchodilator therapy. The study also identified three

intra-operative factors: total vasopressor dose administered, use of a vasopressor infusion, and diuretic administration.

Following this publication, the American College of Surgeons-National Surgical Quality Improvement Program identified

20

other risk factors (Tables 6) and created the General Surgery Acute Kidney Injury Risk Index Classification System

(Figure 6). However, intra-operative risk factors were not investigated and this system has not been validated in other

populations or countries.

Risk factors Risk class Number of risk Risk of major

factors complications

Age >56 yr

Male sex I 0-2 0.2%

II 3 0.8%

Active congestive heart failure

III 4 2.0%

Ascites

IV 5 3.6%

Hypertension

Emergency surgery V 6+ 9.5%

Intraperitoneal surgery

Renal insufficiency – mild or moderate

Diabetes mellitus – oral or insulin therapy

Figure 6. General surgery acute kidney injury risk index classification system

Risk assessment in patients with liver disease

Since the 1970s the main tool for assessing the perioperative morbidity and mortality in patient with liver cirrhosis has

been the Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score which is based on patient’s levels of bilirubin, albumin, the international

normalised ratio (INR) and the severity of encephalopathy and ascites. Most of the studies have consistently reported the

same perioperative outcomes e.g. mortality rates for patients undergoing surgery were 10% for those with Child class A,

21

30% for those with Child class B, and 76–82% for those with Child class C cirrhosis .

Recently, a different model has been used to predict perioperative mortality. MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease)

is now used to risk stratify patients awaiting liver transplantation and more recently used to predict perioperative

mortality. The MELD score is a linear regression model based on serum bilirubin and creatinine, and INR. The MELD

score has several advantages over the CTP score: it weights the variables; it does not rely on arbitrary cut off values and

appears to be more objective. Each point increase in the MELD score makes an incremental contribution to the risk and

22

thus appears to be more precise in predicting perioperative mortality . The use of the MELD score and Child class are

not mutually exclusive and can complement each other.

PATIENT FUNCTIONAL ASSESSMENT

One area of assessment that is quite popular at present is the functional assessment of the patient. Although, functional

assessment has played a big part in preoperative assessment prior to organ removal (e.g. pulmonary testing before lung

resection), recently it has been used to assess patients with long-standing co-morbidities to predict their post-operative

morbidity and mortality. Cardiopulmonary exercise (CPEX) testing assesses patients’ functional status through the use of

incremental physical exercise. The end point is to calculate how well the patient’s cardiopulmonary system can

oxygenate the body and therefore cope with stress of surgery. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing has been shown to

have good morbidity predictive value in pulmonary resection surgery and it is being increasingly validated in vascular,

23, 24

liver and other high-risk surgery, including preparation for transplants . However, it is not routinely available in many

centres and its applicability to all types of surgery is questionable.

SUMMARY

New evidence is emerging that risk assessment makes a significant difference to patient outcomes. It helps to improve

multi-disciplinary decision-making, allocation of critical care resources and communication with patients. Risk

documentation is important and should be made a routine practice, especially in high risk patient groups. With the

improvements in validation and accessibility of different risk stratification tools, it is now the time to consider their use as

part of the standard pre-operative assessment.

Subscribe to ATOTW tutorials by visiting www.wfsahq.org/resources/anaesthesia-tutorial-of-the-week

th

ATOTW 343 – Perioperative risk prediction scores (13 Dec 2016) Page 5 of 7

ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS

1. Regarding risk prediction tools:

a. False: According to NCEPOD ‘Knowing the risk’, only 37/496 (7.5%) patients who were viewed as high-risk

by their anaesthetist had an estimate of the risk of death after surgery documented in their hospital notes.

b. False: Clinical judgement is important but it is not enough to predict adverse outcomes postoperatively.

c. True

d. True

e. False: No such prediction exists at this time.

2. Regarding specific risk prediction tools:

a. True: APACHE score uses three patient related categories (pre-existing disease, patient reserve and

severity of acute illness) to predict outcomes.

b. False: It is uncommonly used as it overestimates mortality.

c. False: MELD score has several advantages over the CTP score: it weights the variables; it does not rely on

arbitrary cut off values and appears to be more objective.

d. False: Functional assessments such as CPEX are not routinely available in all centres.

e. False: Ambler score has been developed specifically to calculate in-hospital mortality for patients undergoing

heart valve surgery.

3. Regarding patient specific risk assessment:

a. True

b. True: The seven independent risk factors are age >59, emergency surgery, chronic liver disease, BMI >32,

high risk surgery, peripheral vascular disease and COPD needing bronchodilator therapy.

c. False: Its applicability to all types of surgery is questionable.

d. False: It only predicts cardiac complications.

e. True

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Steve Copplestone for reviewing this article.

Subscribe to ATOTW tutorials by visiting www.wfsahq.org/resources/anaesthesia-tutorial-of-the-week

th

ATOTW 343 – Perioperative risk prediction scores (13 Dec 2016) Page 6 of 7

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

1. NELA project team. First patient report of the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit. RCoA London, 2015

2. Wong DT, Knaus WA. Predicting outcome in critical care: the current status of the APACHE prognostic scoring

system. Can J Anaesth 1991 38: 374– 83

3. Prytherch DR, Whiteley MS, Higgins B et al. POSSUM and Portsmouth POSSUM for predicting mortality.

Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enUmeration of mortality and morbidity. Br J Surg 1998,

85:1217-1220

4. Protopapa KL, Simpson JC, Smith NCE, et al. Development and validation of the Surgical Outcome Risk Tool

(SORT). Br J Surg 2014 101:1774-1783

5. Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL et al Development and evaluation of the ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: A

decision aid and Informed consent tool for Patients and Surgeons. J Amer Coll Surg 2013 217 (5)833-842

6. Goffi L, Saba V, Ghiselli R et al. Preoperative APACHE II and ASA scores in patients having major general surgical

operations: prognostic value and potential clinical applications. Eur J Surg 1999 165:730-735.

7. Nashef SA, Roques F, Michel P, Gauducheau E, Lemeshow S, Salamon R. European system for cardiac operative

risk evaluation (EuroSCORE). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999 16(1):9-13.

8. Roques F, Michel P, Goldstone AR, Nashef SA. The logistic EuroSCORE. Eur Heart J. 2003 May;24(9):882-3

9. Nashef SA, Roques F, Sharples LD, et al. EuroSCORE II. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012 41:734–745.

10. Anderson RP. First publications from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database. Ann Thorac Surg 1994

57: 6-7

11. Ambler G, Omar RZ, Royston P, Kinsman R, Keogh BE, Taylor KM. Generic, simple risk stratification model for

heart valve surgery. Circulation 2005 112: 224-31.

12. Saklad M. Grading of patients for surgical procedures. Anesthesiology 1941 2:281-284

13. Wolters U, Wolf T, Stutzer H, Shroder T. ASA classification and per-operative variables as predictors of

postoperative outcomes. Br J Anaesth 1996 77:217-222

14. Wolters U, Wolf T, Stutzer H, Shroder T, Pichlmaier H. Risk factors, complications and outcome in surgery: a

multivariate analysis. Eur J Surg 1997 163:563-568

15. Lee TH, Marcantonio, ER, Mangione CM et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for

prediction of cardiac risk of major non-cardiac surgery. 1999 Circulation 100 (10): 1043–1049.

16. Smetana G.W., Lawrence V.A., Cornell J.E.. Preoperative pulmonary risk stratification for non-cardiothoracic

surgery: systematic review for the American College of Physicians

Ann Intern Med 2006, 144:581–595

17. Khuri SF. Multifactorial risk index for predicting postoperative respiratory failure in men after major non-cardiac

surgery. The National Veterans Administration Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Ann Surg, 2000 232:242–

253

18. Arozullah AM, Daley J, Henderson WG, Daley J. Development and validation of a multifactorial risk index for

predicting postoperative pneumonia after major non-cardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med, 2001 135:847–857

19. Kheterpal S, Tremper KK, Englesbe MJ et al. Predictors of postoperative acute renal failure after noncardiac

surgery in patients with previously normal renal function. Anesthesiology. 2007. 107(6):892-902

20. Kheterpal S, Tremper KK, Heung M et al. Development and validation of an acute kidney injury risk index for

patients undergoing general surgery: results from a national data set. Anesthesiology. 2009. 110(3):505-15

21. Friedman LS. Surgery in the patient with liver disease. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2010 121:192-205

22. O'Leary JG, Friedman LS. Predicting surgical risk in patients with cirrhosis: from art to science.

Gastroenterology. 2007 132:1609–11.

23. Carlisle J, Swart M. Mid-term survival after abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery predicted by cardiopulmonary

exercise testing. Br J Surg. 2007 94:966–969.

24. Epstein SK, Freeman RB, Khayat A, Unterborn JN, Pratt DS, Kaplan MM. Aerobic capacity is associated with 100-

day outcome after hepatic transplantation. Liver Transpl 2004 10:418–424

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of

this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/

Subscribe to ATOTW tutorials by visiting www.wfsahq.org/resources/anaesthesia-tutorial-of-the-week

th

ATOTW 343 – Perioperative risk prediction scores (13 Dec 2016) Page 7 of 7

You might also like

- GREAT WRITING 1: Great Sentences For Great Paragraphs: Unit 1 Sentence BasicsDocument19 pagesGREAT WRITING 1: Great Sentences For Great Paragraphs: Unit 1 Sentence Basicssara90% (30)

- Preoperative Evaluation in The 21st CenturyDocument13 pagesPreoperative Evaluation in The 21st CenturyPaulHerrera0% (1)

- Chak de India Management Perspective ProjectDocument21 pagesChak de India Management Perspective ProjectMr. Umang PanchalNo ratings yet

- 4 Roadtec 600 Cummins QSXDocument24 pages4 Roadtec 600 Cummins QSXdavidNo ratings yet

- Hell Bent: Reading Group GuideDocument5 pagesHell Bent: Reading Group GuideKiran KumarNo ratings yet

- Giraffe Blood CirculationDocument9 pagesGiraffe Blood Circulationthalita asriandinaNo ratings yet

- Credit Policy Sample: Accounts Receivable AnalysisDocument3 pagesCredit Policy Sample: Accounts Receivable AnalysisAlinaNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Risk Stratification and ModificationDocument23 pagesPerioperative Risk Stratification and ModificationDianita P Ñáñez VaronaNo ratings yet

- CC 11904Document8 pagesCC 11904ikjaya3110No ratings yet

- Pre-Operative Risk Assessment PostDocument2 pagesPre-Operative Risk Assessment Postapi-405667642No ratings yet

- Preoperative Assessment of The Risk For Multiple Complications After SurgeryDocument10 pagesPreoperative Assessment of The Risk For Multiple Complications After SurgerylaisNo ratings yet

- Critical Care After Major Surgery A Systematic Review of Risk Factors Unplanned Admission - Onwochei UK 2020Document13 pagesCritical Care After Major Surgery A Systematic Review of Risk Factors Unplanned Admission - Onwochei UK 2020Fransisca Dewi KumalaNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0741521416001579Document8 pagesPi Is 0741521416001579Dr-Rabia AlmamalookNo ratings yet

- Development and Validation of A Preoperative Scoring System To Predict 30 Day Mortality in Patients Undergoing Hip Fracture SurgeryDocument7 pagesDevelopment and Validation of A Preoperative Scoring System To Predict 30 Day Mortality in Patients Undergoing Hip Fracture Surgeryuhs888No ratings yet

- Pillai2016 PDFDocument35 pagesPillai2016 PDFmehak malhotraNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Identification of Neurosurgery Patients With A High Risk of In-Hospital Complications: A Prospective Cohort of 418 Consecutive Elective Craniotomy PatientsDocument11 pagesPreoperative Identification of Neurosurgery Patients With A High Risk of In-Hospital Complications: A Prospective Cohort of 418 Consecutive Elective Craniotomy PatientsAzizi AlfyanNo ratings yet

- Apgar LansiaDocument7 pagesApgar Lansiawispa handayaniNo ratings yet

- 1 S PSCDocument8 pages1 S PSCKen WonNo ratings yet

- Pub 2Document6 pagesPub 2Shreyas KateNo ratings yet

- Evaluacion Pulmonar PreoperatoriaDocument15 pagesEvaluacion Pulmonar Preoperatorialuis castillejosNo ratings yet

- What's New in Perioperative Cardiac TestingDocument17 pagesWhat's New in Perioperative Cardiac TestingCamilo HernándezNo ratings yet

- Clinical Neurology and NeurosurgeryDocument5 pagesClinical Neurology and NeurosurgeryRina NovitrianiNo ratings yet

- J NeuroIntervent Surg 2013 González Neurintsurg 2013 010715Document7 pagesJ NeuroIntervent Surg 2013 González Neurintsurg 2013 010715Rogério HitsugayaNo ratings yet

- News LeeDocument5 pagesNews LeeNurdinNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0748798321006429Document10 pagesPi Is 0748798321006429diego fernando olivera briñezNo ratings yet

- 2 Art Ingles IJA-67-39Document9 pages2 Art Ingles IJA-67-39Vanesa Osco SilloNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment POD2023Document10 pagesRisk Assessment POD2023Cláudia Regina FernandesNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0002961017313697 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0002961017313697 MainWialda Dwi rodyahNo ratings yet

- Surgical Risk Preoperative Assessment System (SURPAS)Document7 pagesSurgical Risk Preoperative Assessment System (SURPAS)Guilherme AnacletoNo ratings yet

- World Neurosurg 2021 Apr 2 Camino-Willhuber GDocument6 pagesWorld Neurosurg 2021 Apr 2 Camino-Willhuber GFernando SousaNo ratings yet

- CC 11396Document12 pagesCC 11396Dhavala Shree B JainNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia For Major Urological SurgeryDocument23 pagesAnaesthesia For Major Urological SurgeryDianita P Ñáñez VaronaNo ratings yet

- Critical Care Considerations in Trauma - Overview, Trauma Systems, Initial Assessment PDFDocument19 pagesCritical Care Considerations in Trauma - Overview, Trauma Systems, Initial Assessment PDFPaulina Jiménez JáureguiNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Cardiac Risk AssessmentDocument16 pagesPreoperative Cardiac Risk Assessmentkrysmelis MateoNo ratings yet

- Aen 314Document3 pagesAen 314ReddyNo ratings yet

- RMMJ 9 1 E0004Document8 pagesRMMJ 9 1 E0004Marisa Archila G.No ratings yet

- 2016 - Preoperative Assessment of Geriatric PatientsDocument13 pages2016 - Preoperative Assessment of Geriatric PatientsruthchristinawibowoNo ratings yet

- Prospective External Validation of A Predictive Score For Postoperative Pulmonary ComplicationDocument13 pagesProspective External Validation of A Predictive Score For Postoperative Pulmonary ComplicationAthziri GallardoNo ratings yet

- Cervical Angiograms in Cervical Spine Trauma Patients 5 Years After The Data: Has Practice Changed?Document4 pagesCervical Angiograms in Cervical Spine Trauma Patients 5 Years After The Data: Has Practice Changed?edi_wsNo ratings yet

- Machine Learning Based Models To Support Decision Maki - 2021 - International JoDocument7 pagesMachine Learning Based Models To Support Decision Maki - 2021 - International JobasubuetNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment For Major Adverse CardiovascularDocument11 pagesRisk Assessment For Major Adverse CardiovascularjdjhdNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0300957218309092 Main PDFDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0300957218309092 Main PDFBirhanu MuletaNo ratings yet

- World Journal of Emergency Surgery: Preventable Trauma Deaths: From Panel Review To Population Based-StudiesDocument7 pagesWorld Journal of Emergency Surgery: Preventable Trauma Deaths: From Panel Review To Population Based-StudiesRita RangelNo ratings yet

- Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health: Loai Abu SharourDocument5 pagesClinical Epidemiology and Global Health: Loai Abu SharourDevia YuliaNo ratings yet

- Predicting 30-DayMortality For PatientsWith AcuteHeart Failure in The EmergencyDepartmentDocument14 pagesPredicting 30-DayMortality For PatientsWith AcuteHeart Failure in The EmergencyDepartmentRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Postanaesthetic Care Unit: Review Open AccessDocument7 pagesIntroduction To The Postanaesthetic Care Unit: Review Open AccessSamsul BahriNo ratings yet

- Diagnostics: A Machine-Learning-Based Prediction Method For Hypertension Outcomes Based On Medical DataDocument21 pagesDiagnostics: A Machine-Learning-Based Prediction Method For Hypertension Outcomes Based On Medical DatafarzanaNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors and Associated Complications With Unplanned Intubation in Patients With Craniotomy For Brain Tumor.Document5 pagesRisk Factors and Associated Complications With Unplanned Intubation in Patients With Craniotomy For Brain Tumor.49hr84j7spNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s11605 019 04424 5Document8 pages10.1007@s11605 019 04424 5Rika Sartyca IlhamNo ratings yet

- An Evidence Based Blunt Trauma ProtocolDocument7 pagesAn Evidence Based Blunt Trauma ProtocolPepe pepe pepeNo ratings yet

- Clinical Diagnosis of Uncomplicated, Acute Appendicitis Remains An Imperfect ScienceDocument3 pagesClinical Diagnosis of Uncomplicated, Acute Appendicitis Remains An Imperfect ScienceHector ReinozoNo ratings yet

- PIIS0007091219309298Document10 pagesPIIS0007091219309298Anca OuatuNo ratings yet

- GUIDELINE For IMPROVING OUTCOME After Anaesthesia and Critical Care - 2017 - College of AnaesthesiologistsDocument83 pagesGUIDELINE For IMPROVING OUTCOME After Anaesthesia and Critical Care - 2017 - College of AnaesthesiologistsSanj.etcNo ratings yet

- Hypertension Arterielle 2016Document5 pagesHypertension Arterielle 2016Nabil YahioucheNo ratings yet

- Causes and Predictors of 30-Day Readmission After Shoulder and Knee Arthroscopy: An Analysis of 15,167 CasesDocument7 pagesCauses and Predictors of 30-Day Readmission After Shoulder and Knee Arthroscopy: An Analysis of 15,167 CasesSuzzy57No ratings yet

- Why Thromboprophylaxis Fails Final VDM - 47-51Document5 pagesWhy Thromboprophylaxis Fails Final VDM - 47-51Ngô Khánh HuyềnNo ratings yet

- 2017 Article 168Document15 pages2017 Article 168Rui Pedro PereiraNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Pulmonary Outcomes With OsaDocument9 pagesPerioperative Pulmonary Outcomes With OsawandapandabebeNo ratings yet

- Predictors Post Op VentilationDocument48 pagesPredictors Post Op VentilationMuhammad Azam Mohd NizaNo ratings yet

- CRD42017060841Document5 pagesCRD42017060841Florin AchimNo ratings yet

- Prevencion Del Tev en NeurocirugiaDocument15 pagesPrevencion Del Tev en NeurocirugiaRicardo GarciaNo ratings yet

- NON CARDIAC SURGERY. ESC POCKET GLS.2022. Larger FontDocument63 pagesNON CARDIAC SURGERY. ESC POCKET GLS.2022. Larger FontGeoNo ratings yet

- European Guidelines On Perioperative Venous.11Document5 pagesEuropean Guidelines On Perioperative Venous.11ionut.andruscaNo ratings yet

- A Randomized Controlled Trial of Endovascular Aneurysm Repair Versus Open Surgery For Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms in Low - To Moderate-Risk PatientsDocument8 pagesA Randomized Controlled Trial of Endovascular Aneurysm Repair Versus Open Surgery For Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms in Low - To Moderate-Risk Patientsvfd08051996No ratings yet

- PIIS0022480422004036Document6 pagesPIIS0022480422004036Lucas SCaNo ratings yet

- Community Capstone Health Policy PaperDocument17 pagesCommunity Capstone Health Policy Paperapi-417446716No ratings yet

- Eugenio Ochoa GonzalezDocument3 pagesEugenio Ochoa GonzalezEugenio Ochoa GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Industrial Crops & ProductsDocument10 pagesIndustrial Crops & ProductsShield YggdrasilNo ratings yet

- JOSE R. CATACUTAN, Petitioner, vs. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Respondent FactsDocument2 pagesJOSE R. CATACUTAN, Petitioner, vs. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Respondent FactsAngela Marie AlmalbisNo ratings yet

- MR - Tushar Thombare Resume PDFDocument3 pagesMR - Tushar Thombare Resume PDFprasadNo ratings yet

- Hypertensive Patients Knowledge, Self-Care ManagementDocument10 pagesHypertensive Patients Knowledge, Self-Care ManagementLilian ArthoNo ratings yet

- TRANSITIONS 5 WebDocument40 pagesTRANSITIONS 5 WebCARDONA CHANG Micaela AlessandraNo ratings yet

- 1) What Is Budgetary Control?Document6 pages1) What Is Budgetary Control?abhiayushNo ratings yet

- Week 5 Spain & The ReconquistaDocument6 pagesWeek 5 Spain & The ReconquistaABigRedMonsterNo ratings yet

- Lu PDFDocument34 pagesLu PDFAlexanderNo ratings yet

- Fesco Online BillDocument2 pagesFesco Online BillFaisal NaveedNo ratings yet

- Soft Cheese-Like Product Development Enriched With Soy ProteinDocument9 pagesSoft Cheese-Like Product Development Enriched With Soy ProteinJorge RamirezNo ratings yet

- World Psychiatry - 2024 - Schramm - Algorithm Based Modular Psychotherapy Vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For PatientsDocument10 pagesWorld Psychiatry - 2024 - Schramm - Algorithm Based Modular Psychotherapy Vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For PatientsRodrigo HerNo ratings yet

- Road Slope Protection and Flood Control Pow Template Rev. 9Document183 pagesRoad Slope Protection and Flood Control Pow Template Rev. 9Christian Jahweh Sarvida SabadoNo ratings yet

- IVF STUDY For Case StudyDocument3 pagesIVF STUDY For Case StudygremlinnakuNo ratings yet

- Order Form Dedicated Internet Local: Customer InformationDocument5 pagesOrder Form Dedicated Internet Local: Customer InformationtejoajaaNo ratings yet

- CarouselDocument4 pagesCarouselI am JezzNo ratings yet

- Kunci Gitar Bruno Mars - Talking To The Moon Chord Dasar ©Document5 pagesKunci Gitar Bruno Mars - Talking To The Moon Chord Dasar ©eppypurnamaNo ratings yet

- !why Is My Spaghetti Sauce Always Bland and Boring - CookingDocument1 page!why Is My Spaghetti Sauce Always Bland and Boring - CookingathanasiusNo ratings yet

- 2021-07-02 RCF Presentation On NG RS For KSR Ver-0-RGDocument31 pages2021-07-02 RCF Presentation On NG RS For KSR Ver-0-RGDesign RCFNo ratings yet

- 2volt Powerstack BatteriesDocument4 pages2volt Powerstack BatteriesYasirNo ratings yet

- Sooceal ProjectDocument40 pagesSooceal ProjectSushil ShresthaNo ratings yet

- Professional English 1: WEB 20202 Ms Noorhayati SaharuddinDocument20 pagesProfessional English 1: WEB 20202 Ms Noorhayati SaharuddinAdellNo ratings yet

- Mathematics Grade 10Document270 pagesMathematics Grade 10TammanurRaviNo ratings yet