Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wheeduzzman, Myers

Wheeduzzman, Myers

Uploaded by

Hugo Tedjo SumengkoOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Wheeduzzman, Myers

Wheeduzzman, Myers

Uploaded by

Hugo Tedjo SumengkoCopyright:

Available Formats

Influence of Economic Reward and Punishment on Unethical Behavior: An Empirical

Study

Author(s): A. N. M. Waheeduzzaman and Elwin Myers

Source: Business & Professional Ethics Journal , 2010, Vol. 29, No. 1/4 (2010), pp. 155-

174

Published by: Philosophy Documentation Center

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41340843

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41340843?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Philosophy Documentation Center is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Business & Professional Ethics Journal

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BUSINESS & PROFESSIONAL ETHICS JOURNAL, VOL. 29, NOS. 1-4

Influence of Economic Reward and

Punishment on Unethical Behavior:

An Empirical Study

A. N. M. Waheeduzzaman and Elwin Myers

Abstract: The study seeks to determine the influence of economic re-

ward on unethical behavior with the help of a Reward Punishment Mod-

el. The model postulates that ethical or unethical behavior depends on

the relationship among three factors: economic reward or benefit that a

businessperson receives from the unethical practice, the severity of pun-

ishment the society imposes for such wrong-doing, and the probability of

receiving the punishment. A short survey, which contained a hypothetical

ethical situation, was administered to 251 respondents. The findings in-

dicate that the probability of risk-taking decreases as the level of punish-

ment and the chance of being caught increases.

Key Words: Business Ethics, Economic Reward, Effect of Punishment, Ethi-

cal Decision Making, Unethical Behavior

Introduction

Corruption or white-collar crime is quite pervasive today (Riotto 2008;

Boyle and Tkaczyk 2008). Media is filled with stories about it. Despite the

importance and the coverage of the topic, we still wonder why business

© Business & Professional Ethics Journal , 2010. Correspondence may

be sent to N. M. Waheeduzzaman, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi

College of Business, Corpus Christi, TX, 78412; or via email: waheed@

tamucc.edu; to Elwin Myers, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi Col-

lege of Business, Corpus Christi, TX, 78412; or via email: elwin.myers@

tamucc.edu.

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

156 Business and Professional Ethics Journal

managers engage in unethical behavior. What factors and forces in the

environment influence their conduct? Can social infringement or punish-

ment deter such behavior? So far, the answers to these questions are mixed

and inconclusive. This study is an attempt in addressing some of these

questions. Empirically, it tries to determine the influence of (economic)

reward and punishment on unethical behavior.

The paper is divided into five sections. After the introduction, Sec-

tion II presents a brief literature review. Section III delineates the model

and discusses the methodology, questionnaire, and limitations of the study.

Section IV presents the findings of the study. Section V relates the findings

of this study with other studies in the area and presents its relevance. Sec-

tion VI draws a conclusion with directions for future research.

Background Literature

Why individuals engage in unethical behavior has been investigated from

different perspectives in various disciplines. To keep the review focused, the

authors discuss those theories and studies that are relevant to the model pre-

sented in the study (see Figure 1 ; discussion of the model is presented in the

next section). Studies that involve ethical decision-making are emphasized.

Four theories were relevant to this study: rational choice theory, so-

cial learning theory, moral development, and deterrence theory. A brief

review of those theories and several studies that earlier used those theories

are presented.

Rational Choice Theory

One of the earliest explanations for unethical behavior came from the econ-

omists. They investigated human behavior from the "rational choice theo-

ry," which contends that utility maximization is the primary motive of an

individual; maximizing benefits and minimizing losses is the primary con-

cern. The theory argues that if the benefits of unethical behavior outweigh

its cost, then the individual is likely to engage in unethical behavior (Pili-

avin et al. 1986). The notion also relates to B. F. Skinner's (1957) Operant

Conditioning, which postulates that rewarded behaviors are repeated. This

also explains why corruption works in a vicious cycle. Those who benefit

from it allow it to continue to their favor, encouraging further corruption.

Social Learning Theory

According to Mulki, Jaramillo, and Locander (2009), "Social learning

theory suggests that observed behavior of the leader is mimicked and

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Influence of Economic Reward and Punishment on Unethical Behavior 157

translated into actual behavior with the leader acting as a role model"

(p. 125). Social learning theory, therefore, involves two components: (a)

viewing the behavior of people of authority or influence and (b) model-

ing that behavior (Bandura 1986; Grojean et al. 2004). Employees will

notice the type of behavior of their co-workers that results in favorable

and unfavorable reactions from managers. If they are smart, they will at-

tempt to perform similar actions that resulted in positive outcomes for

their colleagues and avoid actions that resulted in negative consequences

(DeConinck 2003).

This tendency to pattern behavior applies in ethical workplace ap-

plications as well. Workers will notice how co-worker's unethical behav-

ior is dealt with by management (Butterfield, Trevino, and Ball 1996). If

management takes the ethical misconduct seriously and applies a fair and

appropriate penalty, their punishment will be duly noted by other depart-

ment employees (Akaah and Riordan 1989). On the other hand, if man-

agement "looks the other way" and doesn't address unethical employee

behavior harshly, other workers are more inclined to continue participat-

ing in similar behavior (Zey-Ferrell and Ferrell 1982).

Moral Development

The psychologists and behavioral scientists have also investigated ethi-

cal decision-making. In this regard Kohlberg's (1969) moral development

process has often been cited in the literature (Chan and Leung 2006; Rest

1986). He theorized that individuals progress through three levels of cog-

nitive development (pre-conventional, conventional, and post-conven-

tional), each with two stages. Most individuals do not achieve the post-

conventional "principled conscious."

Trevino (1986) proposed a person-situation interactionist model ex-

plaining ethical decision-making. Apparently, Trevino 's model is more

pragmatic than Kohlberg's in terms of application. Rest (1986) proposed

a four-staged model where an individual (a) recognizes a moral issue, (b)

makes a moral judgment, (c) establishes moral intent, and (d) acts on mor-

al concerns. Jones (1991) and Trevino (1986) also developed decision-

making models involving four basic components (O' Fallon and Butter-

field 2005). Ferrell, Gresham, and Fraedrich (1989) integrated the existing

models, synthesizing both cognitive and social aspects in learning. Their

model incorporated cognitive development as well as other economic and

environmental issues. Jones (1991) proposed a comprehensive model on

the previous works [especially Rest's (1986) model] and emphasized the

role of moral intensity in decision-making. The role of moral intensity in

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

158 Business and Professional Ethics Journal

shaping ethical behavior has been highlighted by others (Sweeney and

Costello 2009; Hayibor and Wasieleski 2009).

Deterrence Theory

Deterrence theory holds that a person's likelihood of participating in un-

ethical behavior is related to the perceived risk of being caught and the

severity of punishment if caught (Perino 2002; Young and Zhang 2007).

If the person feels that being caught in an unethical action is likely and

the punishment for the act is severe, the person would be less inclined to

participate in the activity (Williams and Hawkins 1986).

Although deterrence theory is often cited in research studies relat-

ed to crime (Midha 2008; Vance and Trani 2008), military disputes and

conflict resolution (Gartzke and Dong-Joon 2009; Langlois and Langlois

2006), company self-regulation (Short and Toffel 2007), and other areas

(Mitsuhashi and Yamaga 2006), it has also been used in research with

managerial implications. Rose and Rose (2008) studied the effects of trust

and knowledge on 40 corporate board members who had served on audit

committees; they were interested in seeing whether these audit committee

members were able to detect managerial attempts at avoiding oversight

by the audit committee. Staubus (2005) noted that the only real possible

deterrent to unethical or illegal financial fraud is managers' fears of being

caught and punished.

The deterrence theory assumes that individuals would be worried

about being caught. However, some studies have discovered that the pos-

sibility of being caught and the punishment that would follow is a type

of "rush" or excitement rather than the expected deterrent. Al-Rafee and

Cronan (2006) noted persons involved in digital pirating experienced a

low "distress" score (2.75 out of 7) and a relatively high "happiness and

excitement" score (6.21).

Model and Methodology

This section briefly elaborates the model and discusses the methodology

to test the relationships in the model. Questionnaire design, sampling, data

collection, and data analysis are discussed as a part of the methodology.

Limitations of the study are also presented.

Study Model

The model for the study is presented in Figure 1. The model postulates

that ethical or unethical behavior depends on the relationship among three

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Influence of Economic Reward and Punishment on Unethical Behavior 1 59

factors: economic reward or benefit that a businessperson receives from

the unethical practice, the severity of punishment the society imposes for

such wrong-doing, and the probability of receiving the punishment. Se-

verity of punishment and its probability serve as a deterrent for unethical

behavior. A businessperson will risk the practice of unethical behavior as

long as the economic reward is significantly greater than the product of

punishment and its probability. Inequality of reward and punishment sets

the condition for unethical conduct. An earlier version of this model can

be found in Waheeduzzaman (2000).

Methodology

In order to test the relationships in the model a primary survey was con-

ducted. Respondents were managers working in various industries, mostly

from South Texas. The survey employed a convenience sample drawn

from the local Chamber of Commerce, Rotary Club, and students in the

MBA program. The authors and their colleagues from the university

administered the survey to the respondents. Participation in the survey

was voluntary; no inducement was offered. Respondents were assured of

anonymity prior to participation, and nowhere in the questionnaire or in

any part of the research was their identity revealed. The respondents were

asked to be true to themselves in answering the questions.

The questionnaire was pre-tested on a sample of eighteen managers

or working professionals and six business school faculty members. Their

input helped the authors modify the questionnaire. The questionnaire was

simple, easily understandable, and could be completed in about ten min-

utes. The project was duly approved by the Institutional Review Board,

Texas A&M University - Corpus Christi prior to implementation.

The respondents were given a hypothetical ethical situation to evalu-

ate. It describes a scenario where a businessperson is likely to offer a bribe

(unethical behavior) for getting a valuable contract (economic reward).

The probability of risking the contract at different levels of punishment

and their severity is evaluated by the respondents. There are two possible

chances of being caught: they could be caught with a 90% chance, or they

could not be caught with a 90% chance. Two possible levels of punish-

ments are available: jail term for two months or jail term for two years.

Technically speaking, in this model reward is held constant and punish-

ment and severity of punishment are varying.

The respondents were asked to indicate the probability of risking the

contract (i.e., engage in unethical behavior on a seven-point scale). Thus,

by design, the questionnaire captures the probability of risking the contract

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1 60 Business and Professional Ethics Journal

for four levels (two levels of chances of being caught and two levels of

punishment). These four outcomes are used to test the relationships in the

model. The relationships described in the model were tested with the help

of chi-square, mean difference test, correlation, and regression analysis.

Findings of the study are presented in the next section.

Contribution and Limitations

The primary contribution of the study is in the presentation of a simple

model that empirically tests the relationship between unethical behavior

and punishment. The authors are not aware of any other study that tried

to test the relationship in the manner it has been conducted in this study.

Additionally, the study also determines the influence of eight attitudinal

variables on unethical behavior. Demographic influence on unethical be-

havior is also determined.

The study has several limitations. First, this is a voluntary self-re-

ported study. As such, opinion expressed in the survey may not be the true

opinion of the respondents in real life. In fact, they may have provided

"socially acceptable" responses. Second, the situation provided in the sur-

vey is hypothetical; a less-than real life situation. Respondents may take

the hypothetical situations lightly and that may bias the response. Third,

it is a convenience sample. Most subjects of the study come from South

Texas. It is not a nationally representative sample. This limits the gener-

alization of the findings. Scientific sampling could produce better results.

Fourth, the size of the company and amount of the bribe indicates that it

is a medium-sized company. If we changed the size of the company or

amount of the bribe, the response could be different. Fifth, in this study

reward (i.e., amount of bribe) is held as a constant and punishment and

severity of punishment are varied. Changing the value of the reward is

also likely to change in the risk taking behavior. Sixth, the study used "at-

titudinal statements" to determine the influence of individual and social

variables on unethical behavior. They do not lend themselves to causa-

tion. Here the regression is trying to establish causality only indirectly.

Finally, the respondents were asked about "unethical" behavior. This is

not diametrically opposite to "ethical "behavior. By design, the study has

undertaken a negative behavior tone. Individuals could have responded

differently if the questions were asked about ethical behavior.

Despite the limitations, the study contributes in the empirical testing

of the relationship between unethical behavior and punishment. It also

explains the influence of some of the determinants of unethical behavior.

From that perspective it makes some incremental contribution.

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Influence of Economic Reward and Punishment on Unethical Behavior 161

Findings

The findings of the study are presented in this section. At first, respondent

characteristics are described. Then the relationship between risk taking

and punishment is explained. This is followed by an explanation of at-

titude statements and demographics and their influence on risk taking.

Respondent Characteristics

In total, 251 respondents comprise the sample (see Table 1). A majority

(61%) of the respondents are young (18-34 years). Middle aged (35-54

years) and elderly (55 and more years) managers comprise 28% and 10%

of the sample. Relatively speaking, the managers seem to be better edu-

cated. A majority (57%) of the respondents is college graduates, and 42%

have masters' degree.

The respondents are working professionals in different organiza-

tions. Most respondents (55%) have one through ten years of work expe-

rience. Over a quarter (26%) of the respondents have over twenty years

of work experience, and 1 8% have eleven through twenty years of work

experience. Nearly half of the respondents (48%) earn below $40,000 a

year. Two out of five respondents earn between $40,000-60,000, and three

out of ten earn over $60,000 a year. Apparently, in terms of income the

sample is slightly bi-modal in distribution.

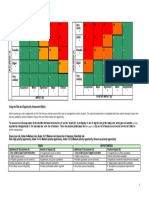

Relationship between Risk Taking and Punishment

As explained in the methodology section, the study offered four different

levels of risk taking outcomes or consequences for the proposed economic

reward situation. The means and standard deviations of these outcomes are

presented in Table 2A. Interestingly, the table indicates that the probability

of risk taking decreases as the level of punishment and the chance of be-

ing caught increases. The probability of risk taking is highest (4.30) when

the punishment is low (2 month jail term) and there is no chance of being

caught. This probability is much higher for the other three outcomes. As

the punishment increases from two months to two years with no chance

of not being caught, the probability decreases to 2.88. This is a 1.42 point

decrease (20%) on a seven-point scale. The probability of risk taking de-

creases as the chance of being caught increases. This is true for both high

(two years) and low (two months) levels of punishment. The lowest risk

taking occurs at high level of punishment and high chance of being caught

(1 .94). Overall, the table indicates that probability of risk taking decreases

as severity of punishment and chance of being caught increase.

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1 62 Business and Professional Ethics Journal

To understand the phenomenon better and determine the relation-

ship between level of punishment and chance of being caught four t-tests

were conducted with the help of PROC MEANS in SAS (see Table 2B).

The results indicate that both severity of punishment and chance of be-

ing caught significantly influence the risk taking behavior. At both levels

of chance of being caught (high and low) the mean difference test be-

tween high and low levels of punishments was significant. Again at two

levels of punishment, mean difference tests between chances of being

caught are significant. The results of the t-tests establish the relationship

hypothesized in the study model (i.e., the respondents' perception is that

the severity of punishment and the chance of receiving it reduce the risk

taking probability.

Rating of Attitude Statements and Correlations

The respondents were asked to state their agreement on eight attitudinal

statements regarding legal system, education, personal ethics, inequality,

religion, family, environment, and profession. The attitude statements and

their means are given in Table ЗА. Interestingly, "I consider myself as

an ethical person" received the highest rating, 6.33 on a 7-point scale. A

related statement "My ethical training primarily took place in my fam-

ily" also received high score (6.04). In self-reported statements like this

we are likely to give high scores to ourselves or our family in which we

grew up. These two statements reflect our deep-seated personal values,

and they indicate moderately high correlation (r = 0.23, see Table 3B).

Interestingly, both education and religion received relatively low scores in

shaping our ethical behavior. This is contrary to what most educators and

moral preachers believe. However, low scores do not mean that religion or

education have no influence in ethical conduct. It simply states that their

influence did not score as highly as other statements. To our surprise, "A

transparent legal system encourages ethical behavior" received the low-

est attitude score (5.08). Our suspicion is some of the respondents did not

fully comprehend the meaning of transparent legal system. Some even put

question marks in the actual questionnaire.

The correlation among eight attitude statements generated by PROC

CORR in SAS is given in Table 3B. The table indicates low to mod-

erate correlation. Ethical environmental (ENVIRON) and professional

ethics (PROFESS) are moderately correlated (r = 0.37). Personal ethics

(PETHIC) is significantly correlated with family (FAMILY), ethical en-

vironment (ENVIRON), and professional ethics (PROFESS). "Education

imparts ethical behavior (EDUSOC)" received low rating, and it is found

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Influence of Economic Reward and Punishment on Unethical Behavior 1 63

to be weakly correlated (r = 0.13) with personal ethics (PETHIC). Inter-

estingly, "Religion provides the foundation of ethical behavior (RELI-

GION)" is significantly correlated with family (FAMILY) and environ-

ment (ENVIRON).

Influence of Attitude Statements and Demographics

Using PROC REG in SAS, the attitude statements were regressed with four

risk taking outcomes, and their results are given in Table 4 A. The F-ratio

indicates that all four models are significant at p = 0.05 level. However,

their R-Squares are very low, ranging from 0.08 to 0. 10. This indicates that

only 8%- 10% of the variability in the outcomes can be explained by the

attitude statements. Interestingly, personal ethics (PETHIC) is significant-

ly negatively related to the risk taking behavior in three out of four models

(see beta-coefficients). This indicates that respondents who rate their per-

sonal ethics to be high are less likely to take a risk for unethical behavior.

Also, "Inequality in a society enhances unethical behavior (INEQUAL)"

is significant in three out of four models. This indicates that as inequality

in a society increase, the probability of unethical risk taking also increases.

No other attitudinal statements show notable significance in the models.

In order to test the influence of the respondent characteristics or de-

mographics on the outcomes general lineal models were run in SAS with

PROC GLM. The results are given in Table 4B. The F-ratios indicate that

all four models are significant. The R-square vary from 0.07 to 0.12. In-

come (INCOME) of the respondent is found to be negatively significant

in all four models. This conveys a meaning that we all expect. Respon-

dents with higher income are less likely to risk unethical conduct. It is

consistent with the relationship with inequality in Table 4A. Individual

education (EDUIND) plays a significant role in ethical conduct and is

found to be negatively significant with risk taking behavior in three out of

four models. It means that with higher levels of education respondents are

less likely to risk participating in unethical practices. A discussion of the

findings of the study is presented in the next section.

Discussion

It is difficult to compare the findings of the study with previous studies

in the area and make an objective comparison since the objective, meth-

odology, and context of the previous studies are different from this one.

Despite the limitations the authors try to relate the findings of this study

with other studies.

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1 64 Business and Professional Ethics Journal

The model proposed in this study draws primarily from the rational

choice theory. The theory holds that people are rational and thereby at-

tempt to weigh the "perceived probabilities and magnitudes of both re-

wards and punishments" (Buckley, Wiese, and Harvey 1998; Michaels

and Miethe 1989; Piliavin, Thornton, Gartner, and Matsueda 1986). Peo-

ple sometimes perform a type of "cost-benefit" analysis in which they

determine for themselves whether the likely benefits of participating in

an action - even unethical or illegal ones - outweigh the costs of possibly

being caught and punished (Buckley, Wiese, and Harvey 1998).

This study specifically sought to determine the perception of survey

respondent managers towards risk taking given a reward-punishment (and

its severity) scenario. The respondent managers indicated that with an in-

crease in punishment and its severity the tendency to take risks decreases.

This tendency has some important implications in both the business and

nonbusiness world. For instance, a good legal system and its proper execu-

tion are likely to reduce white-collar crime (bribery in this case). Many of the

executives who have been implicated in illegal business dealings recently

may have thought that their chances of getting caught were relatively small.

In addition, even if they were caught, they expected that any punishment

would be relatively light. Simply put, they felt that the rewards significantly

outweighed any risks involved. However, some debate remains whether

an increased imprisonment rate would result in a diminished crime rate; at

least one study (Lynch 1 999) found there to be no statistically significant

difference between the two rates for the period under investigation.

Gurley, Wood, and Nijhawan (2007) also hypothesized that the prob-

ability of getting caught and the severity of punishment were related to

ethical behavior. To test their hypothesis, they administered survey instru-

ments to 115 respondents. The survey instrument contained six scenarios

containing ethical dilemmas; respondents were asked to select one of the

four provided responses to each scenario that best reflected their likely ac-

tion to the dilemma. After respondents provided their likely action to the

dilemma, they were then asked to identify how much the "likelihood of

getting caught" and the "severity of the punishment if caught" entered into

their decision. That aspect of their study methodology (likelihood of get-

ting caught and severity of punishment) was very similar to the procedure

used in this study. Likewise, their finding that the two factors are strongly

correlated with ethical behavior was confirmed in this study.

The study also incorporated various social and environmental issues

that have often been related to moral behavior. For instance, one survey

question asked respondents whether they felt that inequality in society led

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Influence of Economic Reward and Punishment on Unethical Behavior 1 65

to unethical behavior. A fairly high number of respondents agreed with the

statement (5.13 mean out of 7). Several studies confirmed the notation that

as inequality in a society increase, the probability of unethical risk taking

also increases; or, stated differently, as economic situations improved for

people individually or collectively, the crime rate tended to drop (Bonger

1969; Phillips, Maxwell, and Votey 1972; Jing and Graham 2007). Myers

(1984) noted that better wages and increased employment tended to result

in lowered crime rates.

Philosophers and moral preachers have traditionally highlighted the

role of individual's personal ethics. They emphasized the importance of

education and training in imparting what Socrates calls "ethos" in human

behavior. This study supports the popular moral preachers' contention -

personal ethics matter. Individuals with a high level of personal ethics

are less likely to offer a bribe; at least that is what the perception is. Our

findings on education are also very similar. In our study we observe that

individuals with higher education are less likely to engage in bribery. This

is contrary to what we observe on white-collar crimes committed. In real

life we find that a large number of people who commit white-collar crimes

are fairly well educated.

Despite the importance of religion, family, ethical environment, and

professional ethics in the literature this study did not find them to be sta-

tistically significant with bribery. However, the findings should not under-

mine the importance of these variables in real life. It is commonly believed

that organized religion has played a positive role in shaping our morals and

minds. In many cases it has helped the reduction of crime. The same is true

for family. By and large, our ethical training takes place in the family.

Providing an ethical environment or establishing a professional code

of conduct does help the reduction of crime. Law provides the basis for

ethical conduct. In a transparent and effective legal system, businesspeo-

ple cannot get corrupt easily. The legal system will force their conduct.

The same is true for professional code of conduct. Today, most profes-

sions require members sign a professional code of conduct. Organizations

also maintain a code of conduct for all employees. This guides the be-

havior of the employees. Studies have shown that it helps in developing

ethical organizations.

Conclusion and Future Direction

The probability of risk taking decreases as the level of punishment and the

chance of being caught increases. If people indeed respond to the likelihood

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1 66 Business and Professional Ethics Journal

of being caught and the severity of possible punishment, those in authority

should do all within their control to make sure that their organizations pos-

sess adequate but fair (Butterfield et al. 2005; Zelizer 2007) mechanisms

to serve as deterrents to employees. This can be attained through laws,

organizational codes of conduct, moral persuasion, counseling and guid-

ance, and education and training. In some aspects this study has addressed

some of these popular issues.

Unlike some other studies (Myers 1980; Martinson 1974; Brier and

Fienberg 1980) this study indicates that the punishment does have a nega-

tive influence on unethical behavior. Understandably, the theory of ratio-

nal choice holds in terms of managerial perception. Personal ethics and

education also affects behavior. Better personal income and reduction of

inequality can play a positive role in reducing corruption.

The study establishes the relationship between individual's risk tak-

ing behavior and reward/punishment. It indicates that individuals take

less risk if severity of punishment is high and its probability is certain.

Influence of various attitudinal statements and demographics on risk tak-

ing is also determined. Hopefully, the findings of the study make some

incremental contribution and lead to further investigations in the area of

business ethics.

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Influence of Economic Reward and Punishment on Unethical Behavior 1 67

Table 1 . Characteristics of Respondents

Characteristics Frequency Percentage

Age

18-34 154 61.35

35-54 71 28.29

55+ 26 10.36

Income

Below $40,000 per

year 121 48.21

$40,000-60,000 per 51 20.32

Уеаг 79 31.47

$60,000+ per year

Education

High School 2 0.8

College graduate 143 56.97

Masters 106 42.23

Work Experience

I-10 years 139 55.38

II-20 years 46 18.33

21+ years 66 26.29

Note: n= 251, Chi-square tests for equa

confirm that there is significant differe

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1 68 Business and Professional Ethics Journal

Table 2. Probability of Risk Taking and T-test Results

A. Probability of Risk Taking

Consequences/Outcomes Mean Std Dev

Has a 90% chance of not being caught and serves a two-month 9 n

jail term (NO_LO)

Has a 90% chance of not being caught and serves a two-year 2 - 88 OQ л 180 on

jail term (NO_HI) 2 - 88 OQ л 180 on

Has a 90% chance of being caught and serves a two-month _

jail term (YES_LO)

Has a 90% chance of being caught and serves a two-year . Q. .

jail term (YES_HI)

B. T-Test Results

Chance of I Mean-Hîgh I Mean-Low ! t.valu J Prob. of t

between Punishment Punishment

Not being I High and Low I ~ 8.2

caught Punishment

Being High and Low

caught Punishment

Level of T-Test Mean*High Chance Mean-Low Chance t-vajue prob

punishment between of Being Caught of Being Caught

High and Low

Low Chance of 2.43 4.30 10.68 <.0001

Being Caught

High and Low

High Chance of 1.94 2.88 6.06 <.0001

Being Caught

Note: Table 2A indicate that probability of risk

increases. Pooled variance method was used for th

when we hold chance constant and vary punishmen

chance of being caught. Both chance of being caugh

taking behavior.

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Influence of Economic Reward and Punishment on Unethical Behavior 1 69

Table 3. Attitude Statements and Their Correlations

A. Mean of Attitude Statements

Abbreviation Attitude Statements Mean

PETHIC I consider myself as an ethical person 6.33

FAMILY My ethical training primarily took place in my family 6.04

PROFESS People in our profession follow an established ethical code 5.24

ENVIRON The environment in which I live is ethical 5.19

INEQUAL Inequality in a society enhances unethical behavior 5.13

EDUSOC Education imparts ethical behavior 5.10

RELIGION Religion provides the foundation of ethical behavior 5.10

LEGAL A transparent legal system encourages ethical behavior 5.08

B. Correlation Matrix of Attitude Statements

LEÖAL EDUSOC PETHIC INEQUAL RELIGION FAMILY ENVIRON PROFESS

LEGAL 1.00

EDUSOC 0.15** 1.00

PETHIC 0.17** 0.13** 1.00

INEQUAL 0.17** 0.17** -0.03 1.00

RELIGION 0.04 0.09 0.02 0.006 1.00

FAMILY 0.08 0.09 0.23** -0.09 0.26** 1.00

ENVIRON 0.01 0.08 0.22** -0.12* 0.19** 0.21** 1.00

PROFESS 0.05 0.12* 0.24** 0.04 0.02 0.16** 0.37** 1.00

Note: Significance of p at 0.05 and 0.10 level is given by ** an

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1 70 Business and Professional Ethics Journal

Table 4. Regression Results

A. Influence of Attitude Statements

NOJLO NÖJHI YES_LO YiS^HI

F-Ratio 2.90** 3.52** 2.64** 2.70**

R-Square 0.09 0.10 0.08 0.08

INTERCEPT 6.11** 2.42** 3.59** 2.42**

LEGAL -0.05 0.08 -0.08 0.14*

EDUSOC 0.02 0.03 0.09 0.15**

PETHIC -0.20 -0.29** -0.32** -0.38**

INEQUAL 0.29** 0.24** 0.18** 0.05

RELIGION 0.008 0.07 0.10 0.07

FAMILY -0.14 0.11 0.04 0.05

ENVIRON -0.08 -0.20** -0.13 -0.09

PROFESS -0.11 0.10 -0.04 -0.001

B. Influence of Demographics

NO_LO NO_HI YES_LO YESJ4I

F-Ratio 8.53** 7.84** 7.74** 4.48**

R-Square 0.12 0.11 0.11 0.07

INTERCEPT 8.15** 5.50** 5.14** 3.00**

AGE -0.10 -0.16 0.48 0.60**

INCOME -0.67** -0.70** -0.73** -0.52**

EDUIND -0.62** -0.43* -0.56** -0.14

WORKEXP -0.20 0.22 -0.09 -0.30

Note: Significance of p at 0.05 and 0.10

Figure 1. The model states that et

lationship among three factors: ec

receives from the unethical practic

of receiving it. A businessperson w

as the economic reward is significa

its probability.

(Un)ethical _ Economic

behavior Reward Punishment Punishment

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Influence of Economic Reward and Punishment on Unethical Behavior 171

Bibliography

Akaah, Ishmael P., and Edward A. Riordan. 1989. "Judgments of Mar-

keting Professionals About Ethical Issues in Marketing Research."

Journal of Marketing Research 26 (February): 112-120.

Al-Rafee, Sulaiman, and Timothy Paul Cronan. 2006. "Digital Piracy:

Factors That Influence Attitude Toward Behavior." Journal of Busi-

ness Ethics 63: 237-259.

Bandura, Albert. 1986. Social Foundation of Thought and Action: A So-

cial Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Block, M. K., and John M. Heineke. 1975. "A Labor Theoretic Analysis of

the Criminal Choice." American Economic Review 65: 314-325.

Bonger, Willem. 1969. Criminality and Economic Conditions . Blooming-

ton: Indiana University Press.

Boyle, Matthew, and Chris Tkaczyk. 2008. "Corporate Convicts: Where

are They Now?" Fortune 157 (June 9): 96-97.

Brier, Stephen S., and Stephen E. Fienberg. 1980. "Recent Econometric

Modeling of Crime and Punishment: Support for the Deterrence Hy-

pothesis?" Evaluation Review 4: 147-191.

Buckley, M Ronald, Danielle S. Wiese, and Michael G. Harvey. 1998.

"Identifying Factors Which May Influence Unethical Behavior."

Teaching Business Ethics 2: 71-84.

Butterfield, Kenneth D., Linda Klebe Trevino, and Gail A. Ball. 1996.

"Punishment From the Managers' Perspective: A Grounded Investi-

gation and Inductive Model." Academy of Management Journal 39

(December): 1479-1512.

Butterfield, Kenneth D., Linda Klebe Trevino, Kim J. Wade, and Gail A.

Ball. 2005. "Organizational Punishment From the Manager's Per-

spective: An Exploratory Study." Journal of Managerial Issues 17:

363-382.

Chan, Samuel Y. S., and Philomena Leung. 2006. "The Effects of Ac-

counting Students' Ethical Reasoning and Personal Factors on Their

Ethical Sensitivity." Managerial Auditing Journal 21 (4): 436-457.

DeConinck, James B. 2003. "The Effects of Punishmen on Sales Manag-

ers' Outcome Expectancies and Responses to Unethical Sales Force

Behavior." American Business Review 21 (2): 135-140.

Ferrell, O. C., Larry G. Gresham, and John Fraedrich. 1989. "A Synthesis

of Ethical Decision Models for Marketing." Journal of Macromar-

keting 9 (2): 55-65.

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1 72 Business and Professional Ethics Journal

Gartzke, Erik, and Jo Dong-Joon. 2009. "Bargaining, Nuclear Prolifera-

tion, and Interstate Disputes." The Journal of Conflict Resolution ,

53 (2): 209.

Grojean, Michael W., Christian J. Resick, Marcus W. Dickson, and Brent

D. Smith. 2004. "Leadings, Values, and Organizational Climate: Ex-

amining Leadership Strategies for Establishing an Organizational

Climate Regarding Ethics." Journal of Business Ethics 55 (Decem-

ber): 223-241.

Gurley, Kathleen, Paula Wood, and Inder Nijhawan. 2007. "The Effect of

Punishment on Ethical Behavior When Personal Gain is Involved."

Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues 10 (1): 91-104.

Hayibor, Sefa, and David M. Wasieleski. 2009. "Effects of the Use of

the Availability Heuristic on Ethical Decision-Making in Organiza-

tions." Journal of Business Ethics 84 (January): 151-165. Accessed

March 16, 2009. doi:10.1007/s 1055 1-008-9690-7.

Jing, Runtian, and John L. Graham. 2008. "Values Versus Regulations:

How Culture Plays its Role." Journal of Business Ethics 80 (4):

791-806.

Jones, Thomas M. 1991. "Ethical Decision Making by Individuals in Or-

ganizations: An Issue-Contingent Model." The Academy of Manage-

ment Review 16 (2): 366-395.

Kohlberg, Lawrence. 1969. "Stage and Sequence: The Cognitive Devel-

opmental Approach to Socialization." Handbook of Socialization

Theory and Research , ed. D. A. Goslin. Rand McNally: Chicago,

347^80.

Langlois, Catherine C., and Langlois, Jean-Pierre. 2006. "When Ful

formed States Make Good the Threat of War: Rational Escalation

and the Failure of Bargaining." British Journal of Political Science

36 (4): 645.

Lynch, Michael J. 1999. "Beating a Dead Horse: Is There any Basic Em-

pirical Evidence for the Deterrent Effect of Imprisonment?" Crime,

Law and Social Change 31 (4): 347-362.

Martinson, Robert. 1974. "What Works? Questions and Answers About

Prison Reform." Public Interest 35: 22-54.

Michaels, James W., and Terance D. Miethe. 1989. "Applying Theories

of Deviance to Academic Cheating." Social Science Quarterly 70:

870-885.

Midha, Vishal. 2008. "The Glitch in On-line Advertising: A Study of

Click Fraud in Pay-per-Click Advertising Programs." International

Journal of Electronic Commerce 13 (2): 91.

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Influence of Economic Reward and Punishment on Unethical Behavior 1 73

Mitsuhashi, Hitoshi, and Hisaki Yamaga. 2006. "Market and Learning

Structures for Gaining Competitive Advantage: An Empirical Study

of Two Perspectives on Multiunit-Multimarket Organizations."

Asian Business and Management 5 (2): 225.

Mulki, Jay P., Jorge Fermando Jaramillo, and William B. Locander. 2009.

"Critical Role of Leadership on Ethical Climate and Salesperson Be-

haviors." Journal of Business Ethics 86 (2): 125-141.

Myers, Samuel L. 1980. "The Rehabilitation Effect of Punishment." Eco-

nomic Inquiry 18: 353-366.

Economics and Sociology 43 (2): 191-195

O'Fallon, Michael J., and Kenneth D. Butterf

Empirical Ethical Decision-Making Litera

nal of Business Ethics 59 (4): 375^113.

Perino, Michael A. 2002 "Enron's Legislative A

tions on the Deterrence Aspects of the Sarb

St. John s Law Review 76 (4): 671-698.

Phillips, Liad, D. Maxwell, and Harold L Vote

and the Labor Market." Journal of Politica

Piliavin, Irving, Craig Thornton, Rosemary G

sueda. 1986. "Crime, Deterrence, and Rat

Sociological Review 51: 101-119.

Rest, Jonathan. 1986. "Moral Development

Theory." New York: Praeger.

Riotto, Joseph J. 2008. "Understanding the S

ued Added Approach for Public Interest."

Accounting 19 (7): 952-962. Accessed March

j.cpa.2005. 10.005.

Rose, Anna M., and Jacob M. Rose. 2008. "

Avoid Accounting Disclosure Oversight: Th

Knowledge on Corporate Directors' Govern

of Business Ethics 83 (2): 193-206.

Short, Jodi L., and Michael W. Toffel. 2008.

Policing in the Shadow of the Regulator."

ics and Organization 24 (1): 45-71.

Skinner, B. F. 1954. "The Science of Learning

Harvard Educational Review 24 (2): 86-97

Staubus, George. 2005. "Ethics Failures in Cor

ing." Journal of Business Ethics 57: 5-15.

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1 74 Business and Professional Ethics Journal

Sweeney, Breda, and Costello, Fiona. 2009. "Moral Intensity and Ethical

Decision-Making: An Empirical Examination of Undergraduate Ac-

counting and Business Students " Accounting Education 1 8 ( 1 ) : 7 5-97 .

Accessed March 16, 2009. doi:l 0.1 080/09639280802009454.

Treviño, Linda Klebe. 1986. "Ethical Decision Making in Organizations:

A Person-Situation Interactionist Model." Academy of Management

Review 11 (3): 601-617.

Vance, Neil, and Trani, Brett. 2008. "Situational Prevention and the Re-

duction of White Collar Crime." Journal of Leadership , Account-

ability and Ethics : 9-18.

Waheeduzzaman, A. N. M. 2000. "(Un)Ethical Behavior in Business: A

Reward Punishment Probability Framework." Competition, Trust

and Cooperation: A Comparative Study , ed. Y. Shinoya and K. Yagi.

Heidelberg: Springer Verlag, 210-226.

Williams, Kirk R., and Hawkins, Richard. 1986. "Perceptual Research on

General Deterrence: A Critical Review." Law and Society Review 20

(4): 545-572.

Young, Randall, and Lixuan Zhang. 2007. "Illegal Computer Hacking:

An Assessment of Factors That Encourage and Deter the Behavior."

Journal of Information Privacy and Security 3 (4): 33-52.

Zelizer, Viviana A. 2007. "Ethics in the Economy." Journal for Business,

Economics and Ethics: 8-23.

Zey-Ferrell, Mary and O. C. Ferrell. 1982. Role-set Configuration and Op-

portunities as Predictors of Unethical Behavior in Organizations."

Human Relations 32 (7): 587-604.

This content downloaded from

182.255.0.242 on Sun, 26 Nov 2023 10:56:09 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- HIRAC Risk AssessmentDocument39 pagesHIRAC Risk AssessmentDaveRaphaelDumanat100% (11)

- The Guide To Construction Arbitrator 3rd EditionDocument479 pagesThe Guide To Construction Arbitrator 3rd EditionHaroon Rasheed100% (10)

- Disease Detectives NotesDocument5 pagesDisease Detectives NotesErica Weng0% (1)

- As 2316.1-2009 Artificial Climbing Structures and Challenge Courses Fixed and Mobile Artificial Climbing andDocument10 pagesAs 2316.1-2009 Artificial Climbing Structures and Challenge Courses Fixed and Mobile Artificial Climbing andSAI Global - APAC100% (1)

- Procurement Management Plan TemplateDocument7 pagesProcurement Management Plan Templatekareem3456No ratings yet

- SAP GRC Access Control 10 Frequently Asked Questions: Raghu BodduDocument23 pagesSAP GRC Access Control 10 Frequently Asked Questions: Raghu BodduPabitraKumar100% (3)

- Analysis of Unethical Behaviors in Social Networks An Application in The Medical Sector 2014 Procedia Social and Behavioral SciencesDocument10 pagesAnalysis of Unethical Behaviors in Social Networks An Application in The Medical Sector 2014 Procedia Social and Behavioral ScienceswawanNo ratings yet

- Palgrave Macmillan Journals Operational Research SocietyDocument9 pagesPalgrave Macmillan Journals Operational Research Societyrei377No ratings yet

- Hoffmann NormsDocument39 pagesHoffmann NormsJill BacasmasNo ratings yet

- Employee Theft 3 (Ethical Theory)Document15 pagesEmployee Theft 3 (Ethical Theory)athirah jamaludinNo ratings yet

- Egoism, Justice, Rights, and Utilitarianism: Student Views of Classic Ethical Positions in BusinessDocument11 pagesEgoism, Justice, Rights, and Utilitarianism: Student Views of Classic Ethical Positions in BusinessBảo PhạmNo ratings yet

- (Un) Ethical Behavior and Performance AppraisalDocument14 pages(Un) Ethical Behavior and Performance AppraisalDaniele BerndNo ratings yet

- An Investigation Into The Dimensions of Unethical BehaviorDocument8 pagesAn Investigation Into The Dimensions of Unethical BehaviorLaura GomezNo ratings yet

- Text Modul 6 Tanggung Jawab Employer Hak PekerjaDocument11 pagesText Modul 6 Tanggung Jawab Employer Hak PekerjaSabaruddin HarahapNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics 3 ND Edition 2017Document18 pagesBusiness Ethics 3 ND Edition 2017tknowledgeNo ratings yet

- Do Gender, Educational Level, Religiosity, and Work Experience Affect The Ethical Decision-Making of U.S. Accountants?Document16 pagesDo Gender, Educational Level, Religiosity, and Work Experience Affect The Ethical Decision-Making of U.S. Accountants?Alfi syahrinNo ratings yet

- Article 2Document9 pagesArticle 2archit.chatterjee05No ratings yet

- Ethical ReasoningDocument21 pagesEthical ReasoningRaditya PramanaNo ratings yet

- Right' Versus Wrong' and Right' Versus Right': Understanding Ethical Dilemmas Faced by Educational LeadersDocument17 pagesRight' Versus Wrong' and Right' Versus Right': Understanding Ethical Dilemmas Faced by Educational LeadersSenorGrubNo ratings yet

- Academy of Management The Academy of Management ReviewDocument42 pagesAcademy of Management The Academy of Management ReviewIoanaNo ratings yet

- Hauser ETHICALISSUESUSE 2018Document18 pagesHauser ETHICALISSUESUSE 2018Shaima ShariffNo ratings yet

- Reasons For Being Selective When Choosing Personnel Selection ProceduresDocument12 pagesReasons For Being Selective When Choosing Personnel Selection ProceduresVictor M. Suarez AvelloNo ratings yet

- Darby RESOLVINGETHICSDILEMMAS 2018Document19 pagesDarby RESOLVINGETHICSDILEMMAS 2018Shaima ShariffNo ratings yet

- 8019-Article Text-31972-1-10-20130828 PDFDocument14 pages8019-Article Text-31972-1-10-20130828 PDFAkila Shree14No ratings yet

- Theory of ConformityDocument38 pagesTheory of ConformityannisaulkhoirohNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To EthicsDocument27 pagesAn Introduction To EthicsMIKI RULOMANo ratings yet

- An Introduction To EthicsDocument27 pagesAn Introduction To EthicsTrisha SabaNo ratings yet

- Por Que Os Funcionários Fazem Coisas Ruins Desengajamento Moral e Comportamento Organizacional AntiéticoDocument48 pagesPor Que Os Funcionários Fazem Coisas Ruins Desengajamento Moral e Comportamento Organizacional AntiéticoBreno Peixoto CortezNo ratings yet

- Influences On Ethics: Report TitleDocument15 pagesInfluences On Ethics: Report TitleSonnyNo ratings yet

- Research Policy: Jeremy Hall, Ben R. MartinDocument14 pagesResearch Policy: Jeremy Hall, Ben R. MartinKaterina GubaNo ratings yet

- Organizations Gone Wild:: The Causes, Processes, and Consequences of Organizational MisconductDocument55 pagesOrganizations Gone Wild:: The Causes, Processes, and Consequences of Organizational MisconductKaterina GubaNo ratings yet

- Ethics Essay Deontology and UtilitarianismDocument5 pagesEthics Essay Deontology and UtilitarianismHarrish Das100% (1)

- Ethical Behaviour in Organizations: A Literature Review: Marmat Geeta, Jain Pooja, Mishra PNDocument6 pagesEthical Behaviour in Organizations: A Literature Review: Marmat Geeta, Jain Pooja, Mishra PNsaraNo ratings yet

- A Typology of Deviant Workplace Behaviors: A Multidimensional Scaling StudyDocument21 pagesA Typology of Deviant Workplace Behaviors: A Multidimensional Scaling Studyesteban2525No ratings yet

- Teori Etika KeperawatanDocument19 pagesTeori Etika Keperawatandwidui93No ratings yet

- An Introduction To EthicsDocument27 pagesAn Introduction To EthicsSreednesh A/l MurthyNo ratings yet

- RR2Document12 pagesRR2jonathanlmyrNo ratings yet

- Angyris's Single and Double Loop LearningDocument14 pagesAngyris's Single and Double Loop LearningtashapaNo ratings yet

- UNIT - 4 Ethical Decision - Marking in BusinessDocument11 pagesUNIT - 4 Ethical Decision - Marking in BusinessAbhishek ThakkarNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics: October 2016Document18 pagesBusiness Ethics: October 2016Monika ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Managerial Perceptions On Employee Misconduct and Ethics Management Strategies in Thai OrganizationsDocument14 pagesManagerial Perceptions On Employee Misconduct and Ethics Management Strategies in Thai OrganizationsMwamba Kenzo ChilangaNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics: October 2016Document18 pagesBusiness Ethics: October 2016Satwanti BaburamNo ratings yet

- Gilliland, 1993Document42 pagesGilliland, 1993Κατερίνα Γ.Ξηράκη100% (1)

- Development of Cheating Dilemma As A Thought Experiment in Assessing The Student's Ethical Decision MakingDocument17 pagesDevelopment of Cheating Dilemma As A Thought Experiment in Assessing The Student's Ethical Decision MakingJohn Vincent SantosNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 PropsalDocument27 pagesChapter 2 Propsalyulia yasmeenNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics ResearchDocument9 pagesBusiness Ethics ResearchBruno QuagliozziNo ratings yet

- West EthicsDocument16 pagesWest Ethics123rajrajNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its ScopeDocument38 pagesThe Problem and Its ScopeSusan DenoreNo ratings yet

- Ethical Theory - Utilitarianism and Rights, Justice andDocument7 pagesEthical Theory - Utilitarianism and Rights, Justice andAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- RamasubramanianandLandmark Ethics IEMP InpressDocument7 pagesRamasubramanianandLandmark Ethics IEMP Inpressstilla lonerNo ratings yet

- Ethical PrakarDocument31 pagesEthical PrakarAJAYSURYAA K S 2128204No ratings yet

- Side Effects Associated With Organizational Interventions A PerspectiveDocument20 pagesSide Effects Associated With Organizational Interventions A PerspectiveSafi A.MNo ratings yet

- Ashkanasy - Falkus - Callan - 2000 (4) - DikonversiDocument15 pagesAshkanasy - Falkus - Callan - 2000 (4) - DikonversiOdiNo ratings yet

- Social Impact Assessment (SIA) From A Multidimensional Paradigmatic Perspective: Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument12 pagesSocial Impact Assessment (SIA) From A Multidimensional Paradigmatic Perspective: Challenges and OpportunitiesvvvpppNo ratings yet

- Mohammed Moinuddin Ethics in Organizational Reasech PaperDocument17 pagesMohammed Moinuddin Ethics in Organizational Reasech PaperShoaib Khan -Vlog'sNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 131.251.33.4 On Tue, 25 Apr 2023 15:0 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTCDocument42 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 131.251.33.4 On Tue, 25 Apr 2023 15:0 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTCAssel SadvakassovaNo ratings yet

- An Assessment of Power Abuse Under Ethics PhilosophiesDocument6 pagesAn Assessment of Power Abuse Under Ethics PhilosophiesHansy ShamNo ratings yet

- Factors - Influencing - Whistleblowing - Intention - AmongDocument10 pagesFactors - Influencing - Whistleblowing - Intention - AmongAmberly QueenNo ratings yet

- Academy of ManagementDocument42 pagesAcademy of Managementsimranarora2007No ratings yet

- Moral Philosophy, Business Ethics, and The Employment RelationshipDocument31 pagesMoral Philosophy, Business Ethics, and The Employment RelationshipJNo ratings yet

- Theories of Career ChoiceDocument16 pagesTheories of Career ChoiceAdrianeEstebanNo ratings yet

- Paper 5Document30 pagesPaper 5aliahilal96No ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Fundamentals of EthicsDocument22 pagesChapter 1: Fundamentals of EthicsAliah CyrilNo ratings yet

- Aac Research Ethics Sensitive Topics enDocument10 pagesAac Research Ethics Sensitive Topics enBilal AhmadNo ratings yet

- Organizational Behaviour: A Case Study of Hindustan Unilever Limited: Organizational BehaviourFrom EverandOrganizational Behaviour: A Case Study of Hindustan Unilever Limited: Organizational BehaviourNo ratings yet

- 16219-Article Text-46936-1-10-20221220Document22 pages16219-Article Text-46936-1-10-20221220Hugo Tedjo SumengkoNo ratings yet

- MolmDocument21 pagesMolmHugo Tedjo SumengkoNo ratings yet

- The Probabilistic Pool Punishment Proportional To The Difference of Payoff Outperforms Previous Pool and Peer PunishmentDocument8 pagesThe Probabilistic Pool Punishment Proportional To The Difference of Payoff Outperforms Previous Pool and Peer PunishmentHugo Tedjo SumengkoNo ratings yet

- SingellDocument6 pagesSingellHugo Tedjo SumengkoNo ratings yet

- Yanis Varoufakis Game TheoryDocument35 pagesYanis Varoufakis Game TheoryHugo Tedjo SumengkoNo ratings yet

- Yanis Varoufakis Against EqualityDocument26 pagesYanis Varoufakis Against EqualityHugo Tedjo SumengkoNo ratings yet

- An Exploration of Students' Experiences With Resilience in Chess Programs in Two Inner-City Middle SchoolsDocument24 pagesAn Exploration of Students' Experiences With Resilience in Chess Programs in Two Inner-City Middle SchoolsFrancesco RossetiNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment and Opportunity Assessment Matrix TableDocument1 pageRisk Assessment and Opportunity Assessment Matrix TableWin AsharNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 Risk and Refinements On CB: © 2012 Pearson Prentice Hall. All Rights ReservedDocument26 pagesChapter 12 Risk and Refinements On CB: © 2012 Pearson Prentice Hall. All Rights ReservedMyra NicdaoNo ratings yet

- Project Work Practical Awareness About Business StudiesDocument10 pagesProject Work Practical Awareness About Business StudiesAbhishek Anand0% (1)

- Law of Insurance AssignmentDocument10 pagesLaw of Insurance AssignmentAmbrose YollahNo ratings yet

- p4sgp 2008 Dec A PDFDocument11 pagesp4sgp 2008 Dec A PDFsabrina006No ratings yet

- ROSTEK - Facade and Roof Access PDFDocument61 pagesROSTEK - Facade and Roof Access PDFptorice100% (2)

- Chapter 1 SolutionsDocument30 pagesChapter 1 SolutionsTaylor CorbettNo ratings yet

- 10 Theses About AI: A Companies' Eye View of The Future of AIDocument16 pages10 Theses About AI: A Companies' Eye View of The Future of AItiti78No ratings yet

- Risk Management Presentation April 15 2013Document106 pagesRisk Management Presentation April 15 2013George LekatisNo ratings yet

- GDPR ISO 27001 Mapping Table 2Document13 pagesGDPR ISO 27001 Mapping Table 2TomasVileikis100% (1)

- McArthur 1996 PDFDocument25 pagesMcArthur 1996 PDFyasta hadiNo ratings yet

- The Mixed Effects Of: InconsistencyDocument4 pagesThe Mixed Effects Of: InconsistencyNibaldo BernardoNo ratings yet

- Rita Gunther Mcgrath: Strategy Moving As Fast As Your Business (Harvard Business Review Press)Document16 pagesRita Gunther Mcgrath: Strategy Moving As Fast As Your Business (Harvard Business Review Press)Theo ConstantinNo ratings yet

- 15 RRL'SDocument11 pages15 RRL'SNathalie Jazzi LomahanNo ratings yet

- PM Process Execution ChecklistDocument22 pagesPM Process Execution ChecklistKeyur PatelNo ratings yet

- Amplified Leicester: Impact On Social Capital and CohesionDocument42 pagesAmplified Leicester: Impact On Social Capital and CohesionNestaNo ratings yet

- 7 Steps To Developing A Cloud Security Plan: WhitepaperDocument15 pages7 Steps To Developing A Cloud Security Plan: WhitepapernicolepetrescuNo ratings yet

- Session 3 - DecisionDocument41 pagesSession 3 - Decision周楚茗No ratings yet

- Occupational Standards Book Transport and LogisticsDocument65 pagesOccupational Standards Book Transport and LogisticsJoze Herrera Severino100% (2)

- Qed DP 275Document25 pagesQed DP 275Sergio ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Adventa Berhad Annual Report 2019Document7 pagesAdventa Berhad Annual Report 2019Shobee Anne Angeles BalogoNo ratings yet

- Coshh Assessment FormDocument6 pagesCoshh Assessment FormAfaan gani InamdarNo ratings yet

- Chief Mate Phase 1 Emergency and ManagementDocument44 pagesChief Mate Phase 1 Emergency and ManagementSudipta Kumar De100% (2)