Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rambus Inc.'S Answering Brief On Remand Proceedings

Rambus Inc.'S Answering Brief On Remand Proceedings

Uploaded by

sabatino123Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Disney Motion To DismissDocument27 pagesDisney Motion To DismissTHROnlineNo ratings yet

- Redacted Public Version FNN Opening Brief in Dominion Case - With Leaked Dominion EmailsDocument169 pagesRedacted Public Version FNN Opening Brief in Dominion Case - With Leaked Dominion EmailsJim HoftNo ratings yet

- Hwang V Savage - Reply To Opposition To DemurrerDocument17 pagesHwang V Savage - Reply To Opposition To DemurrerTHROnlineNo ratings yet

- O'Bannon V NCAA - Reply Brief of Antitrust Plaintiffs in Support of Motion For Class CertificationDocument56 pagesO'Bannon V NCAA - Reply Brief of Antitrust Plaintiffs in Support of Motion For Class CertificationInsideSportsLawNo ratings yet

- Petition For Writ of Prohibition in Markeith Loyd V State of FloridaDocument28 pagesPetition For Writ of Prohibition in Markeith Loyd V State of FloridaReba Kennedy100% (2)

- 12-03-30 Microsoft Motion For Partial Summary Judgment Against MotorolaDocument30 pages12-03-30 Microsoft Motion For Partial Summary Judgment Against MotorolaFlorian Mueller100% (1)

- Cambria Doc Opp To Detention 4 LaceyDocument19 pagesCambria Doc Opp To Detention 4 LaceyStephen LemonsNo ratings yet

- Imasen Phillippine Manufacturing Corporation: G.R. No. 194884 October 22, 2014Document9 pagesImasen Phillippine Manufacturing Corporation: G.R. No. 194884 October 22, 2014Nadin MorgadoNo ratings yet

- Opp Mot Dismiss Western Sugar Co-Op V Archer-Daniels-MidlandDocument120 pagesOpp Mot Dismiss Western Sugar Co-Op V Archer-Daniels-MidlandLara PearsonNo ratings yet

- Brief in Support of Rambus Inc.'S Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of LawDocument36 pagesBrief in Support of Rambus Inc.'S Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Lawsabatino123No ratings yet

- Jackson Cert Opp Brief WesternSkyFinancial v. D.jacksonDocument42 pagesJackson Cert Opp Brief WesternSkyFinancial v. D.jacksonThalia SandersNo ratings yet

- MATSON TERMINALS, INC. v. INSURANCE COMPANY OF NORTH AMERICA Petition To Compel ArbitrationDocument30 pagesMATSON TERMINALS, INC. v. INSURANCE COMPANY OF NORTH AMERICA Petition To Compel ArbitrationACELitigationWatchNo ratings yet

- Google Motion To Dismiss AndroidDocument21 pagesGoogle Motion To Dismiss Androidjeff_roberts881No ratings yet

- "Additional Insured" Status and Rights - What Are The Obligations of The Insurer To The Additional InsuredDocument27 pages"Additional Insured" Status and Rights - What Are The Obligations of The Insurer To The Additional InsuredAmir KhosravaniNo ratings yet

- FDIC v. Killinger, Rotella and Schneider - STEPHEN J. ROTELLA AND DAVID C. SCHNEIDER'S MOTION TO DISMISSDocument27 pagesFDIC v. Killinger, Rotella and Schneider - STEPHEN J. ROTELLA AND DAVID C. SCHNEIDER'S MOTION TO DISMISSmeischerNo ratings yet

- 67-1 Mem Iso Doyn MTN To DismissDocument32 pages67-1 Mem Iso Doyn MTN To DismissCole StuartNo ratings yet

- Lenhoff UtaDocument28 pagesLenhoff UtaEriq GardnerNo ratings yet

- Muscle Milk Objection Final WC 030514Document26 pagesMuscle Milk Objection Final WC 030514Will ChamberlainNo ratings yet

- Appeal Isps Torrentfreak PDFDocument40 pagesAppeal Isps Torrentfreak PDFtorrentfreakNo ratings yet

- 26 - Oppn Re PIDocument138 pages26 - Oppn Re PISarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- 00590-20031014 RIAA Opp ProtectiveDocument18 pages00590-20031014 RIAA Opp ProtectivelegalmattersNo ratings yet

- Greene V Paramount MSJDocument33 pagesGreene V Paramount MSJTHROnlineNo ratings yet

- 67 - Campaign Response Re PJ DiscoveryDocument22 pages67 - Campaign Response Re PJ DiscoveryProtect DemocracyNo ratings yet

- Additional Counsel Listed On Signature Page.Document25 pagesAdditional Counsel Listed On Signature Page.sabatino123No ratings yet

- 16-05-17 Oracle Motion For JMOL On 'Fair Use'Document30 pages16-05-17 Oracle Motion For JMOL On 'Fair Use'Florian MuellerNo ratings yet

- 2018-08-24 Memorandum of Law (DCKT 128 - 0)Document31 pages2018-08-24 Memorandum of Law (DCKT 128 - 0)eriqgardnerNo ratings yet

- Chiquita Cross Motion To Disqualify Terry CollingsworthDocument16 pagesChiquita Cross Motion To Disqualify Terry CollingsworthPaulWolfNo ratings yet

- Dell LawsuitDocument34 pagesDell LawsuitMichael KrigsmanNo ratings yet

- Upreme Court, U.S.: NO. - O, . N 1.2 2010Document46 pagesUpreme Court, U.S.: NO. - O, . N 1.2 2010Matthew Seth SarelsonNo ratings yet

- Attorneys For Defendants Attorney General Edmund G. Brown JRDocument38 pagesAttorneys For Defendants Attorney General Edmund G. Brown JREquality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- 13-12-02 Nokia's Proposal For Sanctions Against Samsung and Quinn EmanuelDocument33 pages13-12-02 Nokia's Proposal For Sanctions Against Samsung and Quinn EmanuelFlorian MuellerNo ratings yet

- Winston & Strawn LLP: D ' S B R J IDocument33 pagesWinston & Strawn LLP: D ' S B R J ItorrentfreakNo ratings yet

- Barile - NFLX Class Cert BriefDocument21 pagesBarile - NFLX Class Cert BriefPeter BarileNo ratings yet

- Scientology v. Dandar: State Supreme Court ResponseDocument16 pagesScientology v. Dandar: State Supreme Court ResponseTony OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Blurred Lines Trial - Gaye Injunction Motion - Williams + Thicke v. Gaye PDFDocument22 pagesBlurred Lines Trial - Gaye Injunction Motion - Williams + Thicke v. Gaye PDFMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Appellants CasesDocument21 pagesAppellants Casesidris2111No ratings yet

- Chiquita Motion For Summary Judgment On Negligence Per SeDocument25 pagesChiquita Motion For Summary Judgment On Negligence Per SePaulWolfNo ratings yet

- Doster Opposition MootnessDocument61 pagesDoster Opposition MootnessChrisNo ratings yet

- Rambus'S Opp. To Hynix'S Mot. For Summary Judgment, Etc. CASE NO. 00-20905-RMWDocument64 pagesRambus'S Opp. To Hynix'S Mot. For Summary Judgment, Etc. CASE NO. 00-20905-RMWsabatino123No ratings yet

- Plaintiffs' Response To Defendant's Objection To Magistrate Order "Deeming" Certain Facts Established and "Striking" Certain Affirmative DefensesDocument76 pagesPlaintiffs' Response To Defendant's Objection To Magistrate Order "Deeming" Certain Facts Established and "Striking" Certain Affirmative DefensesAnonymous XkawRUfNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court of The United States: Petitioners, VDocument32 pagesSupreme Court of The United States: Petitioners, VlegalmattersNo ratings yet

- P ' R Blag' O - S J C N - 3:10 - 0257-JSW SF - 3021132Document22 pagesP ' R Blag' O - S J C N - 3:10 - 0257-JSW SF - 3021132Equality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- 161 Oppo To Omnibus & Joinders - RedactedDocument184 pages161 Oppo To Omnibus & Joinders - RedactedCole StuartNo ratings yet

- SBN SBN SBN: United States District Court Northern District of California San Jose DivisionDocument15 pagesSBN SBN SBN: United States District Court Northern District of California San Jose Divisionsabatino123No ratings yet

- 00614-20031121 Riaa ReplyDocument19 pages00614-20031121 Riaa ReplylegalmattersNo ratings yet

- Exhibit ADocument139 pagesExhibit Asabatino123No ratings yet

- News Corp HackingDocument58 pagesNews Corp HackingApril PetersenNo ratings yet

- GOOG Referrer SettlementDocument29 pagesGOOG Referrer SettlementBrandon.BaileyNo ratings yet

- Siegel Superman/Superboy Opposition To Summary Judgment Filing March 4, 2013Document443 pagesSiegel Superman/Superboy Opposition To Summary Judgment Filing March 4, 2013Jeff TrexlerNo ratings yet

- Ratner v. Kohler (Reply in Opposition To MTD)Document26 pagesRatner v. Kohler (Reply in Opposition To MTD)THROnlineNo ratings yet

- 15-10-14 Apple Motion For Summary Judgment Against EricssonDocument20 pages15-10-14 Apple Motion For Summary Judgment Against EricssonFlorian MuellerNo ratings yet

- Good Morning To You v. Warner Chappell - Happy Birthday To You Amended Cross Motions For Summary Judgment PDFDocument61 pagesGood Morning To You v. Warner Chappell - Happy Birthday To You Amended Cross Motions For Summary Judgment PDFMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Birthday SJMDocument61 pagesBirthday SJMEriq GardnerNo ratings yet

- ABS Entertainment v. CBS Radio (Remastering Issue)Document32 pagesABS Entertainment v. CBS Radio (Remastering Issue)Digital Music NewsNo ratings yet

- Ada Ramirez Initial Brief Eleventh CircuitDocument60 pagesAda Ramirez Initial Brief Eleventh CircuitMatthew Seth SarelsonNo ratings yet

- Chiquita Reply To Renewed Motion To RemandDocument16 pagesChiquita Reply To Renewed Motion To RemandPaulWolfNo ratings yet

- Watts Water v. Sidley (Sidley Motion For Summary Judgment)Document38 pagesWatts Water v. Sidley (Sidley Motion For Summary Judgment)Mike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- Arbitration Law and Practice in KenyaFrom EverandArbitration Law and Practice in KenyaRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (4)

- Show Temp PDFDocument1 pageShow Temp PDFsabatino123No ratings yet

- United States District Court Eastern District of Texas Marshall DivisionDocument4 pagesUnited States District Court Eastern District of Texas Marshall Divisionsabatino123No ratings yet

- United States District Court Eastern District of Texas Marshall DivisionDocument4 pagesUnited States District Court Eastern District of Texas Marshall Divisionsabatino123No ratings yet

- In The United States District Court Eastern District of Texas Marshall DivisionDocument2 pagesIn The United States District Court Eastern District of Texas Marshall Divisionsabatino123No ratings yet

- Innovative Display Technologies, LLC v. ZTE Corporation, Et Al.Document2 pagesInnovative Display Technologies, LLC v. ZTE Corporation, Et Al.sabatino123No ratings yet

- AtDocument1 pageAtsabatino123No ratings yet

- Innovative Blackberry DismissalDocument2 pagesInnovative Blackberry DismissaliphawkNo ratings yet

- Innovative Acer DismissalDocument1 pageInnovative Acer DismissaliphawkNo ratings yet

- United States District Court For The Eastern District of Texas Marshall DivisionDocument2 pagesUnited States District Court For The Eastern District of Texas Marshall Divisionsabatino123No ratings yet

- Innovative Microsft SettlementDocument2 pagesInnovative Microsft SettlementiphawkNo ratings yet

- Innovative Blackberry DismissalDocument2 pagesInnovative Blackberry DismissaliphawkNo ratings yet

- In The United States District Court For The Eastern District of Texas Marshall DivisionDocument33 pagesIn The United States District Court For The Eastern District of Texas Marshall Divisionsabatino123No ratings yet

- Defendants.: LITIOC/2100839v3/101022-0107Document4 pagesDefendants.: LITIOC/2100839v3/101022-0107sabatino123No ratings yet

- Innovative Markman OrderDocument58 pagesInnovative Markman OrderiphawkNo ratings yet

- Innovative Apple DismissalDocument1 pageInnovative Apple DismissaliphawkNo ratings yet

- Joint Motion To Dismiss: Arnan Orris Ichols RSHT UnnellDocument2 pagesJoint Motion To Dismiss: Arnan Orris Ichols RSHT Unnellsabatino123No ratings yet

- Innovative Canon DismissalDocument2 pagesInnovative Canon DismissaliphawkNo ratings yet

- PlaintiffDocument3 pagesPlaintiffsabatino123No ratings yet

- IAM Magazine Issue 67 - Hands-On CounselDocument5 pagesIAM Magazine Issue 67 - Hands-On Counselsabatino123No ratings yet

- Defendants.: LITIOC/2100839v3/101022-0107Document4 pagesDefendants.: LITIOC/2100839v3/101022-0107sabatino123No ratings yet

- 6Document21 pages6sabatino123No ratings yet

- Innovative Display Technologies LLCDocument4 pagesInnovative Display Technologies LLCsabatino123No ratings yet

- Tut 4 - Reliance Financial StatementsDocument3 pagesTut 4 - Reliance Financial StatementsJulia DanielNo ratings yet

- Lecture ISO - 14915 - 2 - EN PDFDocument11 pagesLecture ISO - 14915 - 2 - EN PDFtest2012No ratings yet

- Annual Report and Accounts 2020Document382 pagesAnnual Report and Accounts 2020EvgeniyNo ratings yet

- The 4 Principles - MIAWDocument13 pagesThe 4 Principles - MIAWfariskhosa69No ratings yet

- OesDocument44 pagesOesLincoln TeamNo ratings yet

- Emorandum: Special Zoom Event 23 March 2022 (Wednesday) at 8pmDocument2 pagesEmorandum: Special Zoom Event 23 March 2022 (Wednesday) at 8pmwarna setiaNo ratings yet

- فاير تكDocument17 pagesفاير تكrody.egy.225No ratings yet

- 17th National Scout Jamboree Application FormDocument1 page17th National Scout Jamboree Application FormJiro MandigmaNo ratings yet

- ISKCON Desire Tree - Sri Krishna Kathamrita - Bindu 037Document4 pagesISKCON Desire Tree - Sri Krishna Kathamrita - Bindu 037ISKCON desire treeNo ratings yet

- Cost of Capital 2Document29 pagesCost of Capital 2BSA 1A100% (2)

- Chapter 1 - Nature and Scope of NGASDocument26 pagesChapter 1 - Nature and Scope of NGASJapsNo ratings yet

- Peke NaoDocument19 pagesPeke Naomark perezNo ratings yet

- Writs of Error Sent To Edward Robles 353 BlackhawkDocument39 pagesWrits of Error Sent To Edward Robles 353 Blackhawkbindi boya beyNo ratings yet

- Spouses CHA v. CADocument3 pagesSpouses CHA v. CAAnonChie100% (1)

- ABM Investama TBK.: Company Report: January 2019 As of 31 January 2019Document3 pagesABM Investama TBK.: Company Report: January 2019 As of 31 January 2019dhiladaikawaNo ratings yet

- Holding Out IPA 1932Document9 pagesHolding Out IPA 1932Shubham PhophaliaNo ratings yet

- Beretta M9Document1 pageBeretta M9JustinNo ratings yet

- Bulgarian Method 1Document9 pagesBulgarian Method 1TRASH SHUBHAMNo ratings yet

- VAL 185 Guidance For The Use of Risk Assessment in Validation SampleDocument3 pagesVAL 185 Guidance For The Use of Risk Assessment in Validation SampleSameh MostafaNo ratings yet

- Indian Railway Catering and Tourism Corporation (IRCTC IN) : Q3FY20 Result UpdateDocument7 pagesIndian Railway Catering and Tourism Corporation (IRCTC IN) : Q3FY20 Result UpdateanjugaduNo ratings yet

- Jawaban jurnal-UD BUANADocument54 pagesJawaban jurnal-UD BUANAnafit100% (8)

- Surfrider Foundation's Comments On The Proposed Settlement Agreement On Plant Size and Level of OperationDocument22 pagesSurfrider Foundation's Comments On The Proposed Settlement Agreement On Plant Size and Level of OperationL. A. PatersonNo ratings yet

- Constitution and Federalism Study GuideDocument5 pagesConstitution and Federalism Study Guideapi-550843042No ratings yet

- Glosar Termeni ComercialiDocument37 pagesGlosar Termeni ComercialiMaithun100% (1)

- 9) CARLITO B. LINSANGAN, PETITIONER, v. PHILIPPINE DEPOSIT INSURANCE CORPORATION, RESPONDENT. G.R. No. 228807, February 11, 2019Document6 pages9) CARLITO B. LINSANGAN, PETITIONER, v. PHILIPPINE DEPOSIT INSURANCE CORPORATION, RESPONDENT. G.R. No. 228807, February 11, 2019Nathalie YapNo ratings yet

- 1019 Fishbone Cause and Effect Diagram For PowerpointDocument3 pages1019 Fishbone Cause and Effect Diagram For Powerpointamri anaNo ratings yet

- PARMINDER AUDIT TaskDocument7 pagesPARMINDER AUDIT TaskMah Noor FastNUNo ratings yet

- Guide Investigator HandbookDocument45 pagesGuide Investigator HandbookCompaq Presario0% (1)

- Concept, Nature and Significance of IPRsDocument11 pagesConcept, Nature and Significance of IPRsVaibhav Kumar Garg100% (1)

Rambus Inc.'S Answering Brief On Remand Proceedings

Rambus Inc.'S Answering Brief On Remand Proceedings

Uploaded by

sabatino123Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rambus Inc.'S Answering Brief On Remand Proceedings

Rambus Inc.'S Answering Brief On Remand Proceedings

Uploaded by

sabatino123Copyright:

Available Formats

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page1 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

Gregory P. Stone (SBN 078329) Fred A. Rowley, Jr. (SBN 192298) MUNGER, TOLLES & OLSON LLP 355 South Grand Avenue, 35th Floor Los Angeles, CA 90071-1560 Telephone: (213) 683-9100 Facsimile: (213) 687-3702 Email: gregory.stone@mto.com Email: fred.rowley@mto.com Peter A. Detre (SBN 182619) Carolyn Hoecker Luedtke (SBN 207976) MUNGER, TOLLES & OLSON LLP 560 Mission Street, 27th Floor San Francisco, CA 94105-2907 Telephone: (415) 512-4000 Facsimile: (415) 512-4077 Email: peter.detre@mto.com Email: carolyn.luedtke@mto.com Attorneys for RAMBUS INC.

Rollin A. Ransom (SBN 196126) SIDLEY AUSTIN LLP 555 West Fifth Street, Suite 4000 Los Angeles, CA 90013-1010 Telephone: (213) 896-6000 Facsimile: (213) 896-6600 Email: rransom@sidley.com Pierre J. Hubert (Pro Hac Vice) Craig N. Tolliver (Pro Hac Vice) MCKOOL SMITH PC 300 West 6th Street, Suite 1700 Austin, TX 78701 Telephone: (512) 692-8700 Facsimile: (512) 692-8744 Email: phubert@mckoolsmith.com Email: ctolliver@mckoolsmith.com

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA, SAN JOSE DIVISION

HYNIX SEMICONDUCTOR, INC., et al., Plaintiffs, vs. RAMBUS INC., Defendant.

CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW RAMBUS INC.S ANSWERING BRIEF ON REMAND PROCEEDINGS Date: Time: Ctrm: Judge: October 21, 2011 10:30 AM 6 Honorable Ronald M. Whyte

RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page2 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 VI. V.

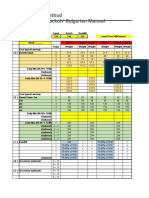

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 ARGUMENT .................................................................................................................................. 1 I. II. III. IV. This Court Need Not Resolve the Spoliation Issues Raised by Hynix ............................... 1 Even if the Court Addressed Spoliation, It Would Not Change The Result....................... 4 Hynix Has Waived Any Sanctions Short of Dismissal....................................................... 7 Hynix Has Failed to Show the Manifest Injustice, or Even Good Cause, Required to Reopen Discovery or Reopen the Record ....................................................................... 8 The Court Should Reject, Once Again, Hynixs Attempt To Invoke Collateral Estoppel As To Spoliation ................................................................................................ 11 A. B. C. This Court Has Broad Discretion To Deny Preclusion......................................... 11 The Court Should Exercise Its Discretion To Deny Preclusion............................ 12 Preclusion Should Likewise Be Denied As To The 103 Particularized Factual Issues Identified By Hynix ....................................................................... 14

Judicial Efficiency Supports this Courts Immediate Resolution of Hynixs Unclean Hands Defense, and Not Deference to the Delaware Court ............................... 15

CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................. 15

-i-

RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page3 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 FEDERAL CASES

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s)

American Intl Trading Corp. v. Petroleos Mexicanos, 835 F.2d 536 (5th Cir. 1987)..................................................................................................... 9 Anderson v. Cryovac, Inc., 862 F.2d 910 (1st Cir. 1998) ..................................................................................................... 1 Bakalar v. Vavra, ___ F. Supp. 2d ___, 2011 WL 165407 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 14, 2011) ..................................... 9, 11 Bobby v. Bies, 129 S. Ct. 2145 (2009) ............................................................................................................ 14 Broad v. Sealaska Corp., 85 F.3d 422 (9th Cir. 1996)....................................................................................................... 7 California Dental Assn v. F.T.C., 224 F.3d 942 (9th Cir. 2000)........................................................................................... 1, 9, 11 Cardiac Pacemakers, Inc. v. St. Jude Medical, Inc., 576 F.3d 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2009)................................................................................................. 3 Cleveland v. Piper Aircraft Corp., 985 F.2d 1438 (10th Cir. 1993)............................................................................................. 8, 9 Coburn v. Smithkline Beecham Corp., 174 F. Supp. 2d 1235 (D. Utah 2001) ..................................................................................... 15 Connors v. Tanoma Mining Co., 953 F.2d 682 (D.C. Cir. 1992) ................................................................................................ 14 Engel Indus., Inc. v. Lockformer Co., 166 F.3d 1379 (Fed. Cir. 1999)................................................................................................. 4 Herrington v. County of Sonoma, 12 F.3d 901 (9th Cir. 1993)....................................................................................................... 4 Hoffman v. Tonnemacher, 2006 WL 3457201 (E.D. Cal. Nov. 30, 2006) ...................................................................... 8, 9 Hynix Semiconductor Inc. v. Rambus Inc., 591 F. Supp. 2d 1038 (N.D. Cal. 2006) ........................................................................ 2, 3, 5, 6 Hynix Semiconductor Inc. v. Rambus Inc., 645 F.3d 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2011)............................................................................................. 4, 5 - ii RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page4 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued) Page(s) In re Microsoft Corp. Antitrust Litig., 355 F.3d 322 (4th Cir. 2004)............................................................................................. 12, 14 Instituform Techs. v. Cat Contr., 161 F.3d 688 (Fed. Cir. 1998)................................................................................................... 9 Johns Hopkins Univ. v. CellPro, Inc., 152 F.3d 1342 (Fed. Cir. 1998)............................................................................................... 10 Kendall v. Visa U.S.A., Inc., 518 F.3d 1042 (9th Cir. 2008)................................................................................................. 14 Martins Herend Imports, Inc. v. Diamonad & Gem Trading United States Co., 195 F.3d 765 (5th Cir. 1999)..................................................................................................... 8 Micron Tech., Inc. v. Rambus Inc., 255 F.R.D. 135 (D. Del. 2009).............................................................................................. 5, 6 Micron Tech., Inc. v. Rambus Inc., 645 F.3d 1311 (Fed. Cir. 2011)........................................................................................ passim Millenkamp v. Davisco Foods Intl, Inc., 2009 WL 3430180 (D. Idaho Oct. 22, 2009) .......................................................................... 11 Monsanto Co. v. Bayer Bioscience N.V., 514 F.3d 1229 (Fed. Cir. 2008)................................................................................................. 8 Moses Lake Homes, Inc. v. Grant County, 276 F.2d 836 (9th Cir. 1960)................................................................................................... 10 Northwest Acceptance Corp. v. Lynnwood Equip., Inc., 841 F.2d 918 (9th Cir. 1988)..................................................................................................... 7 Parklane Hosiery Co. v. Shore, 439 U.S. 322 (1979) .................................................................................................... 11, 12, 13 Powers v. Boston Cooper Corp., 926 F.2d 109 (1st Cir. 1991) ................................................................................................... 10 Rochez Bros., Inc. v. Rhoades, 527 F.2d 891 (3d Cir. 1975).................................................................................................... 10 Rodriguez-Garcia v. Miranda-Marin, 610 F.3d 756 (1st Cir. 2010) ................................................................................................... 13

- iii -

RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page5 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued) Page(s) Schmid v. Milwaukee Elec. Tool Corp., 13 F.3d 76 (3d Cir. 1994).......................................................................................................... 1 Setter v. A.H. Robbins Co., 748 F.2d 1328 (8th Cir. 1984)................................................................................................. 14 Whitehead v. K-Mart Corp., 173 F. Supp. 2d 553 (S.D. Miss. 2000)..................................................................................... 8 FEDERAL RULES Fed. R. Civ. P. 16 .......................................................................................................................... 10 Fed. R. Civ. P. 16(e).................................................................................................................... 8, 9 Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(2)................................................................................................................. 10 TREATISES 18A Wright & Miller, Federal Practice & Procedure: 4465.3 (2d ed. 2002).............................. 14

- iv -

RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page6 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 I.

INTRODUCTION Hynix presents this Court with a false dichotomy: the Court either must start from scratch in adjudicating Hynixs unclean hands defense, or it must cede to the Delaware Court, applying collateral estoppel and otherwise staying its hand. The most principled and efficient path to judgment here lies between these veering routes: the Court should resolve Hynixs unclean hands defense on the independent grounds of bad faith and prejudice; reject its request for an unwarranted second bite at the [evidentiary] apple, California Dental Assn v. F.T.C., 224 F.3d 942, 959 (9th Cir. 2000); and refuse the preclusion that would reward Hynixs forum arbitrage. ARGUMENT THIS COURT NEED NOT RESOLVE THE SPOLIATION ISSUES RAISED BY HYNIX Hynix insists that this Court must determine a specific duty date, and promises, at some point, to show that the duty date was well before the September 1998 shred day. But this Court need not resolve that issue. The onset of a duty to preserve, followed by breach of the duty, is just one of several predicates of Hynixs unclean hands defense. Bad faith and prejudice are also required. As to those issues, the Court has already applied the legal standards set forth in Micron II and, upon applying them, found no bad faith and no prejudice. Irrespective of exactly when the duty attached, those undisturbed findings independently foreclose Hynixs defense: Bad Faith: The intent required for bad faith is more specific and rigorous than that required for mere spoliation. Bad faith entails an intent to stymie the opposition, Anderson v. Cryovac, Inc., 862 F.2d 910, 925 (1st Cir. 1998), or impair the ability of the potential defendant to defend itself, Schmid v. Milwaukee Elec. Tool Corp., 13 F.3d 76, 80 (3d Cir. 1994). As Hynix itself emphasizes, spoliation may be found where the party breached a preservation duty without fraudulent intent. (Hynix Br. (Br.) 6.) The Federal Circuit also distinguished between the intent required for spoliation simpliciter and [t]he fundamental element of bad faith spoliation justifying dismissal: the latter requires advantage-seeking behavior by the party with superior access to information necessary for the proper administration of justice. Micron Tech., Inc. v. Rambus Inc., 645 F.3d 1311, 1326 (Fed. Cir. 2011) (Micron II). This Court applied the same standard in finding that Rambus did not act in bad faith, and

RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page7 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

Hynix offers no explanation as to how Hynix II or Micron II changes its analysis. Hynix points to various factors that might have informed the Delaware Courts determination of bad faith (Br. 5), but the Federal Circuit merely noted these in dicta after having vacated that bad faith determination. The Federal Circuit specifically stated, immediately after noting these findings, that [i]t is not our task to make factual findings, and that it would leave it to the district courts sound discretion on remand to analyze these, and any other, relevant facts. Micron II, 645 F.3d at 1327 (citation omitted). This Court has already considered whether Rambuss document retention policy was adopted within the auspices of a firm litigation policy, any facts tending to show the selective execution of the document retention policy, and any facts tending to show Rambuss acknowledgment of [its] impropriety (BR. 5)and it reached the opposite conclusion from the Delaware Court on these matters. This Court concluded that the Policy was undisputedly content neutral, and was not adopted in bad faith, Hynix Semiconductor Inc. v. Rambus Inc., 591 F. Supp. 2d 1038, 1052 (N.D. Cal. 2006) (Hynix I); that Rambus did not target[] or destroy[] prior art, infringement analyses[,] or reverse engineering documents, id. at 1058-59; that the Policy did not single out JEDEC-related documents, id. at 1066; and that the evidence failed to show that Rambus targeted any specific document or category of relevant documents with the intent to prevent production in a lawsuit, id. at 1069 (emphasis added). Because the Federal Circuit expressly declined to reach these issues in Hynix II, and because it vacated the Delaware Courts bad faith findings, there is simply nothing in the Federal Circuits resolution of predicative spoliation issues that would affect this Courts finding of no bad faith. Prejudice: Even if Rambus were somehow deemed to have acted in bad faith, Hynixs unclean hands defense would require a determination that Hynix was prejudiced. Hynix offers no explanation of why this Court must revisit its finding of no prejudice to carry out the mandate. There is none. Prejudice is an issue entirely separate from spoliation and bad faith. This Court indisputably applied the correct legal test (Rambus Br. 18-20), and found there was no showing of prejudice even assuming the burden shifted to Rambus, Hynix I, 591 F. Supp. 2d at 1067. Hynix suggests it was prejudiced if Rambus failed to produce all responsive evidence. (Br. 8.) But none of its cases support the notion that a party may be prejudiced where, as here, -2RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page8 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

adequate similar and material documents or classes of documents were not destroyed. Hynix I, 591 F. Supp. 2d at 1067. Indeed, in remanding Micron II, the Federal Circuit allowed that the destroyed documents might be redundant and thus immaterial to the defendants ability to present its defense. 645 F.3d at 1328. Hynix points to comments made by the Federal Circuit in suggesting the destroyed documents could have helped the defenses analyzed by the Delaware Court in finding prejudice. Id. But the point is hypothetical, as the Federal Circuit made clear, because the issue was remanded for the Delaware Court to decide in the first instance. Id. This analysis does not cast doubt on this Courts finding of no prejudice, which Hynix II did not reach. Even on its own terms, Micron IIs commentary on the Delaware Courts prejudice analysis does nothing to undercut this Courts analysis. The Delaware Courts determination that Rambus destroyed relevant, discoverable documents, Micron II, 645 F.3d at 1321-22, can hardly change this Courts prejudice analysis, because this Court also noted that Hynix has made a showing that Rambus destroyed some relevant documents, Hynix I, 591 F. Supp. 2d at 1067. This Court found no prejudice because Rambus established that adequate similar and material documents or classes of documents were not destroyed. Id. The only two categories of defenses the Delaware Court found to be potentially affected by Rambuss document destruction were (1) Microns JEDEC-related defenses; and (2) its inequitable conduct defense. Micron II, 645 F.3d at 1328. Neither concern supports a finding of prejudice in this case. As we have explained (Rambus Br. 19), this Courts determination that Hynix suffered no prejudice to its JEDEC-related defenses has only been strengthened by the Federal Circuits equitable estoppel and implied waiver affirmance. Nor can Hynix show prejudice as to inequitable conduct: again, this Court already found that Rambus did not target[] or destroy[] prior art, Hynix I, 591 F. Supp. 2d at 1058-59, and that documents such as notes of interviews with the inventors and draft responses to the patent examiner would probably be privileged and not discoverable, id. at 1068. In any event, Hynixs defense of inequitable conduct [was] abandoned and [was] therefore dismissed with prejudice (Final Judgment, Mar. 10, 2009, at 1), making it barred under the mandate rule, Cardiac Pacemakers, Inc. v. St. Jude Medical, Inc., 576 F.3d 1348, 1357 (Fed. Cir. 2009). -3RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page9 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

On both bad faith and prejudice, the Courts findings would stand even if the Court were to revisit spoliation and fix a duty date before the first shred day. Indeed, it would be enough if the Court found either no bad faith or no prejudice, and the ITC case that Hynix now touts (Br. 4) on spoliation concluded that there was no prejudice despite having found both spoliation before the first shred day and bad faith. Although Hynix suggests that the ALJ in that case improperly gave Nvidia the burden to prove prejudice, the ITCs letter to the Federal Circuitwhich Rambus furnished to the Court at the status conferencespecifically states that in the instant investigation, Rambus demonstrated that the supposedly destroyed evidence was actually produced. (ITC, Rule 28(j) Letter, May 16, 2011, at 2, attached hereto as Exhibit A.) II. EVEN IF THE COURT ADDRESSED SPOLIATION, IT WOULD NOT CHANGE THE RESULT If the Court deems it necessary to decide whether spoliation occurred, then it should resolve that issue in Rambuss favor. Although Hynix reads Hynix II to hold that Rambus engaged in spoliation during shred day two (Br. 2), it is wrong, and the ultimate issue of spoliation remains open on remand. Spoliation entails more than the destruction of documents after a duty to preserve attached: the party must show that relevant evidence was destroyed. E.g., Hynix Semiconductor Inc. v. Rambus Inc., 645 F.3d 1336, 1344-45 (Fed. Cir. 2011) (Hynix II). The Federal Circuit limited its Hynix II holding to the date Rambus incurred a duty to preserve: it held that this Court erred in applying too narrow a standard of reasonable foreseeability, and that litigation was reasonably foreseeable prior to Rambuss Second Shred Day. Id. at 1347. At the same time, the Federal Circuit remanded for reconsideration of the spoliation issue under the framework set forth in Micron II, id. at 1355, and observed that the Court could determine[] that Rambus did not spoliate documents, id. at 1347. The rule of mandate allows a lower court to decide anything not foreclosed by the mandate. Herrington v. County of Sonoma, 12 F.3d 901, 904 (9th Cir. 1993), and the issue of spoliation was explicitly reserved or remanded by the court, Engel Indus., Inc. v. Lockformer Co., 166 F.3d 1379, 1383 (Fed. Cir. 1999). Accordingly, neither the mandate rule nor its correlative law-of-the-case limitations preclude this Court from reconsidering the issue of whether Rambuss destruction of documents from its second shred day onward constituted spoliation (Br. 2). To prevail on that issue, Hynix -4RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page10 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

would need to establish that relevant evidence remained after the first shred day, or that new and relevant evidence was later created, which was then destroyed in the second shred day. (Rambus Br. 20-22.) Hynix has not satisfied this burden. Nor can Hynix escape its burden to show that relevant evidence was destroyed in the second shred day by arguing for a duty date preceding the first shred day and the July 1998 tape degaussing. (Br. 4.) Even under the Federal Circuits new standard, this Courts findings of factwhich were themselves undisturbedestablish that the duty did not attach until the summer of 1999 at the earliest, immediately before the second shred day. To show that the duty attached before the first shred day in September 1998, Hynix would need to demonstrate that litigation was reasonably foreseeable by Spring 1998, around the time Joel Karp made his first presentation to the Rambus board and after Rambus had met with outside counsel Cooley. Hynix II, 645 F.3d at 1343; Hynix I, 591 F. Supp. 2d at 1048. But neither the Federal Circuit nor the Delaware Court was willing to find the onset of a duty that early, and for good reason: the documents and the testimony establish that in early 1998, both Rambus and its outside counsel understood licensing to be a backup business strategy. (10/18/05 Reporters Transcript (RT) 393, 428; 10/27/05 RT 1321; 11/1/05 RT 1673-74, 1714; RTX 80.) The Cooley meetings addressed litigation only as a typical follow-on issue attendant to implement[ing] a licensing program. (11/1/05 RT 1673-74.) And the timeline used by Karp in his Board presentation made clear that any licensing strategy depended on multiple factors, the resolution of which was not reasonably foreseeable in March 1998, cf. Hynix II, 645 F.3d at 1346, and that Rambus would not even consider litigation before that process concluded (HTX 6). That Rambus adopted its Document Retention Policy at the same time is not itself suspicious, since the Policy was content-neutral, based on a standard template, and adopted at the urging of Rambuss outside counsel and outside security consultant. The only reasonable inference from the early documents, then, is that litigation was a contingent backup to Rambuss backup licensing plan, reflecting, at most, a generally assertive approach to business, Micron Tech., Inc. v. Rambus Inc., 255 F.R.D. 135, 150 (D. Del. 2009) (Micron I). That is not enough for reasonable foreseeability under Micron II, a point the Federal Circuit impliedly recognized in declining -5RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page11 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

Hynixs invitation to hold that Rambus reasonably foresaw litigation by the time it commenced destroying documents and computer tapes en masse in mid-1998. (Hynixs Reply and Response Brief on Appeal, at 19 (emphasis added), available at 2010 WL 804435.) Under Micron IIs approach and view of the evidence, it was only in July of 1999, immediately before the second shred day, that Rambus triggered a preservation duty by t[aking] several steps in furtherance of litigation. Micron II, 645 F.3d at 1323. Although the Delaware Court found that the duty attached in December 1998 based on its reading of the Nuclear Winter Memo, Micron I, 255 F.R.D. at 150, this Court has already found that the plans outlined in the memo were hesitant, tentative, and contingent in nature (Order Denying Hynixs Mot. for Summ. J., Feb. 3, 2009 (CE Order) at 10). The Memo, this Court explained, was premised on a hypothetical scenario, and hypothesized how to convince Intel to continue their dealings in the event that the relationship between Intel and Rambus was compromised by the existence of another technology. Hynix I, 591 F. Supp. 2d at 1049, 1062 (emphasis added); see also CE Order 9 (emphasizing the speculative, contingent nature of Mr. Karps planning). That is correct, for the Memo treats the motive for litigationthe failure of Direct RDRAM and the concomitant need for non-compatible licensingas remote. Licensing, let alone litigation, rested on the major assumption that Intel move[d] away from Rambus to something else that may be totally new, having been developed in secret by elves in the Black Forest. (HTX 4; see also CE Order 10 (It is a rare memo that sets forth a companys policy and anticipated court actions and also begins its first sentence with an off-the-cuff reference to Black Forest elves.).) This was a very unlikely scenario, even for something thats purely hypothetical. (HTX 4.) In this respect, it is telling that the Micron II Court also declined to affirm the December 1998 duty date, and opted instead for a binary determination that the duty attached before the second shred day. 645 F.3d at 1322. It was only in July 1999, immediately before the second shred day, that the Federal Circuit concluded Rambus took several steps in furtherance of litigation. Id. at 1323. Specifically, the Federal Circuit pointed to Joel Karps IP Q3 99 Goals summary, which listed, under the heading Licensing/Litigation readiness, [p]resent licensing strategy to exec and gain approval, [p]repare licensing positions against 3 -6RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page12 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

manufacturers, and [p]repare litigation strategy against 1 of the 3 manufacturers. (HTX 140.) III. HYNIX HAS WAIVED ANY SANCTIONS SHORT OF DISMISSAL Hynix argues, in passing, that it plans to request lesser sanctions and remedial measures in the event the Court decides not to impose a dismissal sanction. (Br. 10.) It is too late for Hynix to seek sanctions other than dismissal at this point. At every critical juncture, Hynix has limited the relief it sought for spoliation to dismissal, and has therefore repeatedly waived any lesser sanction. See, e.g., Northwest Acceptance Corp. v. Lynnwood Equip., Inc., 841 F.2d 918, 924 (9th Cir. 1988). Hynix made a strategic choice to take an all-or-nothing approach, and must now live with the consequences. Hynix first waived lesser sanctions in the final pretrial conference statement, where it contended only that [t]he patents-in-suit are unenforceable due to Rambuss Unclean Hands, and did not seek lesser sanctions. (Final Pretrial Statement for Unclean Hands Trial, Oct. 4, 2005, at 8; id. at 11.) See Northwest Acceptance Corp., 841 F.2d at 924 (defense not raised in the pretrial conference order is waived). Hynix then waived lesser sanctions a second time at trial, where it argued that dismissal is the proper remedy here (11/1/2005 RT 1795-96), asked that the Court dismiss these claims (id. at 1872), and never sought a sanction short of dismissal. If this were not enough, Hynix waived lesser sanctions a third time in its proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law, which were filed after trial. There, Hynix again stated that dismissal is the only appropriate remedy for the spoliation and other misconduct that has occurred in this case. (Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law on Spoliation, Nov. 14, 2005, at 92 (emphasis added).) Because lesser sanctions were not raised sufficiently for the trial court to rule on it, they were conclusively waived before Hynix even pressed its appeal. Broad v. Sealaska Corp., 85 F.3d 422, 430 (9th Cir. 1996). On appeal, Hynix went on to cement its waiver by framing the spoliation issue solely in terms of the complete defense of unclean hands. Hynix argued that Rambuss unclean hands preclude it from enforcing its patents against Hynix (Hynixs Opening Brief on Appeal at 20, available at 2009 WL 3186084), and [i]n light of its spolation, Rambus may not enforce its patents against Hynix (id. at 28). That failure to raise the issue of lesser sanctions under an -7RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page13 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

inherent authority theory constitutes yet another independent waiver. See Monsanto Co. v. Bayer Bioscience N.V., 514 F.3d 1229, 1240 n.16 (Fed. Cir. 2008). Because dismissal is the only remedy that remains on the table, it is irrelevant whether Hynix is seeking dismissal based solely upon its unclean hands defense or under an inherent authority theory. The Federal Circuit held in Micron IIa pure inherent authority casethat dismissal should not be imposed unless there is clear and convincing evidence of both bad-faith spoliation and prejudice to the opposing party, 645 F.3d at 1328-29 (emphasis added), requirements mirroring the elements of unclean hands. IV. HYNIX HAS FAILED TO SHOW THE MANIFEST INJUSTICE, OR EVEN GOOD CAUSE, REQUIRED TO REOPEN DISCOVERY OR REOPEN THE RECORD Hynix pushes at an open door in arguing that reopening the record and discovery are within this Courts discretion. Our authorities treat this issue as discretionary, but set out

12 standards and considerations to guide trial courts in the exercise of that discretion. E.g., 13 Cleveland v. Piper Aircraft Corp., 985 F.2d 1438, 1450 (10th Cir. 1993) (explaining that on 14 remand, the court should, within the exercise of discretion, consider whether denial of the new 15 evidence would create a manifest injustice); Hoffman v. Tonnemacher, 2006 WL 3457201, at 16 *1-*2 (E.D. Cal. Nov. 30, 2006) (recognizing that district courts have the discretion to admit or 17 exclude new evidence or witnesses on retrial, but applying Rule 16(e)s framework). Although 18 Hynix insists that it need not demonstrate that manifest injustice would result if this Court does 19 not reopen the record (Br. 21), that is the prevailing standard. See Cleveland, 985 F.2d at 1450; 20 Hoffman, 2006 WL 3457201, at *1-*2; Martins Herend Imports, Inc. v. Diamonad & Gem 21 Trading United States Co., 195 F.3d 765, 775 (5th Cir. 1999); Whitehead v. K-Mart Corp., 173 F. 22 Supp. 2d 553, 564-65 (S.D. Miss. 2000). 23 This standard makes good sense. Where, as here, an action has proceeded through trial 24 and to final judgment and an appeal, the parties have had a full opportunity to develop their cases. 25 In particular, they have already availed themselves of the pre-trial and trial procedures set out by 26 the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. To reopen discovery or the record after this process has run 27 its courseand ten years after the events at issuea party should be required to offer a 28 -8RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page14 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

compelling reason why the prior proceedings did not give it the chance to discover or develop evidence; absent such a showing, there is no unfairness. Cf. American Intl Trading Corp. v. Petroleos Mexicanos, 835 F.2d 536, 539 (5th Cir. 1987). That is why many remand courts look to the Rule 16(e) standard for the modification of final pre-trial orders, which addresses the same concerns. See Cleveland, 985 F.2d at 1450 (trial court must perceive[] in limiting evidentiary proof in a new trial, a manifest injustice). This is not to say that a final pretrial order operates as a legal straightjacket; Rule 16(e)s manifest injustice standard simply guides the exercise of discretion. Tonnemacher, 2006 WL 3457201, at *1 (citation omitted). A critical consideration under the manifest injustice standard is whether the party is seeking to discover or introduce new and material evidence which was not otherwise readily accessible or known. See Cleveland, 985 F.2d at 1450; see also Tonnemacher, 2006 WL 3457201, at *2. Indeed, even those remand courts that have applied a less rigorous good cause standard give dispositive weight to the prior availability of evidence. See, e.g., Bakalar v. Vavra, __ F. Supp. 2d , 2011 WL 165407, at *4 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 14, 2011) (considering, under a good cause standard, whether the moving party was diligent in obtaining discovery within the guidelines established by the court). And while neither the Federal Circuit nor the Ninth Circuit has chosen between these standards, they both have made clear that it is appropriate to refuse to admit additional evidence on remand that could have been introduced at the first trial. See California Dental, 224 F.3d at 959 (after reversal on legal standard, refusing to permit additional testimony because plaintiff decided not to call expert at first trial); Instituform Techs. v. Cat Contr., 161 F.3d 688, 695 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (affirming decision to refuse additional evidence absent a showing that it could not have been found and submitted at the first trial). Hynix cites no legal authority on what the considerations or factors ought to be in weighing its request to reopen discovery and, ultimately, to reopen the trial record. Instead, Hynix points to a number of considerations that it claims support reopening the record (Br. 21), which either are non-sequiturs or beg the question. The fact that Hynix is not seeking to take new depositions (id.) does not address whether it ought to be able to obtain the discovery it is seeking or whether it ought to be able to introduce any resulting evidence. If Rambus has long -9RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page15 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

possessed these materials (id.), it stands to wonder why Hynix did not seek to discover them long ago. And even assuming that reopening the record would enable this Court to decide the remanded questions on a more complete record (id. at 22), that is almost certainly true whenever a case is remanded. Yet, courts have repeatedly stressed that remands are not ordinarily intended to giv[e] a party an opportunity to supply a deficiency in his evidence. Moses Lake Homes, Inc. v. Grant County, 276 F.2d 836, 853 (9th Cir. 1960); accord Rochez Bros., Inc. v. Rhoades, 527 F.2d 891, 894 (3d Cir. 1975). Hynixs position reduces to the following: that the existence of parallel litigation, and thus the possibility of additional evidence, suffices to warrant reopening discovery and the record. But if that were enough, discovery would never close in this case and the litigation would never end. The filing of any Rambus litigation, or even the deposition of any Rambus witness who testified in the Unclean Hands trial, would instantly be grounds to reopen discovery in this case. That cannot be right. Finality is a critically important concept in our system of jurisprudence. At some point, battles must end. Powers v. Boston Cooper Corp., 926 F.2d 109, 112 (1st Cir. 1991). It is for this reason that a plaintiff must do more than point to the possibility of additional evidence to vacate a judgment: it must offer, within a year of the judgment, newly discovered evidence that, with reasonable diligence, could not have been discovered in time to move for a new trial . Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(2) (emphasis added). Hynix never filed such a motion, and there is no reason why it should be permitted to supplement the factual record on remand issues merely because it obtained a reversal on a narrow, and ultimately non-dispositive, legal issue. Contrary to Hynixs suggestion, Johns Hopkins Univ. v. CellPro, Inc., 152 F.3d 1342 (Fed. Cir. 1998), does not change this analysis. The Federal Circuit there rejected an argument that a pretrial order from a first trial controls the range of evidence to be considered in a second trial. Id. at 1356-57 (emphasis added). But the Court did not deem Rule 16 irrelevant, and the legal ruling requiring a second triala new claim constructionchanged the rules of the game, as evidence that was previously irrelevant became relevant under the new construction. Id. Here, in contrast, none of the standards adopted or applied in Hynix II or Micron II altered the universe of relevant facts. Because these decisions do not change[] the rules of the game, Hynix must - 10 RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page16 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

offer a compelling justification for seeking or introducing new evidence. See Millenkamp v. Davisco Foods Intl, Inc., 2009 WL 3430180, at *2-*3 (D. Idaho Oct. 22, 2009). The few items of evidence Hynix identifies confirm that it cannot demonstrate good cause, let alone manifest injustice. All the items identified were available through the exercise of due diligence at the time of the first trial. The fact that Dan Johnson, Joel Karp, Mark Horowitz, Michael Farmwald, Allen Roberts, and Lester Vincent all testified at the Micron trial (Br. 22) cannot be considered new evidence, for each of these witnesses also testified at the Unclean Hands trial. The same is true of the witnesses who testified in the price-fixing trial. (Id. at 24.) Hynix points to the deposition testimony, offered in the ITC proceedings, in which Craig Hampel discussed Joel Karps instructions. (Id. at 23.) But that deposition was taken on July 20, 2001 years before the Unclean Hands trialand was therefore available to [Hynix] before fact discovery closed. Cf. Bakalar, 2011 WL 165407, at *4 (rejecting supplemental expert testimony). Hampel was also potentially available to Hynix as a trial witness, since he was (and remains) a Rambus employee. Reopening the record in these circumstances would give [Hynix] an unwarranted second bite at the apple. California Dental, 224 F.3d at 959. V. THE COURT SHOULD REJECT, ONCE AGAIN, HYNIXS ATTEMPT TO INVOKE COLLATERAL ESTOPPEL AS TO SPOLIATION Because the Courts findings of no bad faith and no prejudice stand regardless of whether Rambus engaged in spoliation on the second shred day, Hynixs effort to invoke collateral

19 estoppel on that issue is academic. In any event, Hynixs argument is in large part a re-tread of 20 arguments this Court has already rejected. This Court should reject them again. 21 22 23 doctrine (CE Order 2), the application of which will necessarily rest on the trial courts sense of 24 justice and equity (id. (citation omitted)). The Court expressly rejected Hynixs argumentthe 25 same one it is making nowthat the Court lacks discretion because Hynix is asserting a type of 26 defensive estoppel. (Id.) It is the lack of mutuality, not the offensive or defensive label, 27 that triggers the Courts discretion. (Id. (citing Parklane Hosiery Co. v. Shore, 439 U.S. 322, 331 28 - 11 RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

A.

This Court Has Broad Discretion To Deny Preclusion

As the Court previously held, non-mutual issue preclusion is a distinctively risky

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page17 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26

n.6 (1979)).) The Court focused on [t]he unfairness of being precluded based on a trial that a party did not choose, noting that [w]hile Rambus brought an infringement claim against Micron, it did not choose the time, venue, or adversary. (Id. at 3-4.)1 B. The Court Should Exercise Its Discretion To Deny Preclusion

The Court previously exercised its discretion to deny preclusion on the grounds of (1) the inconsistent rulings in Hynix I and Micron I; (2) Hynixs coordination with Micron to subject Rambus to dual-front litigation; and (3) the lack of efficiency. (CE Order 4-9.) The vacatur of the Courts determination of no unclean hands need not, and should not, change that outcome, because the latter two factors still apply forcefully here. Hynix Should Not Be Rewarded For Multiplying Litigation: The general rule should be that in cases where a plaintiff could easily have joined in the earlier action a trial judge should not allow the use of offensive collateral estoppel. Parklane, 439 U.S. at 331; id. at 329 n.13; In re Microsoft Corp. Antitrust Litig., 355 F.3d 322, 326 (4th Cir. 2004). That is because the application of non-mutual preclusion would give declaratory judgment plaintiffs like Hynix and Micron every incentive to adopt a wait and see attitude, rather than bringing a joint action, in the hope that [the other action] will result in a favorable judgment. Parklane, 439 U.S. at 330. The Courts undisputed finding that Hynix coordinated with Micron in instituting multiforum litigation is sufficient, without more, to dispose of Hynixs preclusion bid. (CE Order 7); Parklane, 439 U.S. at 329 n.13. By coordinating separate attacks on Rambuss patents, Hynix is transparently hoping to hedge its litigation bets: Hynix continues to press its defenses here, while invoking the results of the Delaware case. Indeed, Hynixs requestdespite having brought this suitthat this Court stop its work in deference to the Delaware Court is a textbook example of the inefficiency and inequity of which Parklane disapproved. Hynix does not seriously dispute that it engaged in coordination to multiply the litigation against Rambus. (CE Order 7.) Instead, Hynix offers up strawman arguments that fail to address

1

27 28

While labeling is immaterial here, Hynixs preclusion bid is offensive because Rambus is the defendant in both Hynix and Micron, forced to defend its patents in forums its adversaries chose. See Parklane, 439 U.S. at 331 n.15 ([I]n cases of offensive estoppel the defendant against whom estoppel is asserted typically will not have chosen the forum in the first action.). - 12 RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page18 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

the concerns animating Parklane. Hynix contends that joint defense efforts are not unlawful, and that declaratory judgment actions are not suspect. (Hynix Br. 17-18.) But the issue here is the effect of Hynixs multi-forum attack on the application of preclusion, not whether joint defense efforts are lawful. That a plaintiff is generally entitled to the forum of its choice (id. at 19) is also irrelevant. Of course a plaintiff can choose its forum. But if it files in a new forum despite the opportunity to join in an earlier action, then it should not be allowed to profit from that choice through non-mutual preclusion. Parklane, 439 U.S. at 329 n.13; (CE Order 6-8).2 Lastly, Hynix claims it did not wait and see because it previously sought preclusion on the basis of other actions. (Br. 18.) Hynix has misunderstood Parklane: the wait and see strategy the Supreme Court disapproved involves a partys decision to not intervene[] in the first action, not that partys invocation of preclusion. 439 U.S. at 330. Applying Preclusion Would Serve No Efficiency Objective: Efficiency is [a] fundamental purpose of non-mutual issue preclusion, and is [offensive] collateral estoppels only true justification. (CE Order 8.) Hynixs request to preclude the issue of spoliation on the second shred day would not lead to efficiency gains, and should therefore be denied. (See id.) Regardless of how the spoliation issue is decided, the Court will still need to resolve the issues of bad faith and prejudice. If the Court re-enters its undisturbed prior findings of no bad faith and no prejudice (as it should), then Hynixs unclean hands defense necessarily fails, and nothing would be gained by precluding the spoliation issue. On the other hand, if the Court reexamines Hynixs assertions of bad faith and prejudice, then the Court will need to consider much of the same facts and evidence that bear on the spoliation issue. Courts have consistently denied estoppel in such circumstances, because no efficiency could be gained. Rodriguez-Garcia v. Miranda-Marin, 610 F.3d 756, 772 (1st Cir. 2010) (a district court may refuse to apply nonmutual collateral estoppel when, for example, its application would not result in efficiency Hynixs complaints about Rambuss actions against infringers are more meritless still. Rambuss actions afford it no undue advantages, because Rambus cannot assert preclusion against one infringer on the basis of a prior victory against a different, unrelated infringer. Moreover, as this Court pointed out, Rambus pursued its claims consistently with judicial efficiency by filing multiple actions before a single court. (CE Order 7.) Hynix seizes on the Delaware Courts denial of Rambuss motion to transfer the Delaware action (Br. 16), but that motion would have been unnecessary if Hynix and Micron had joined in the same action. - 13 RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

2

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page19 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6

gains because litigation of the live issue may require introduction of some of the same evidence pertinent to the estopped issues); Setter v. A.H. Robbins Co., 748 F.2d 1328, 1331 (8th Cir. 1984) (similar); cf. 18A Wright & Miller, Federal Practice & Procedure: 4465.3 (2d ed. 2002). C. Preclusion Should Likewise Be Denied As To the 103 Particularized Factual Issues Identified by Hynix

Even apart from the discretionary factors that suffice to defeat preclusion, Hynixs laundry list of 103 statements from the Micron II opinion (Br. Appx. A) can carry no preclusive force, 7 because Hynix cannot make a threshold showing that these statements are necessary or 8 essential to the Micron II judgment. Bobby v. Bies, 129 S. Ct. 2145, 2152 (2009) (a finding is 9 necessary only when the final outcome hinges on it); accord Connors v. Tanoma Mining Co., 10 953 F.2d 682, 685 (D.C. Cir. 1992) (no preclusion if the precise legal basis upon which the 11 judgment rests is unclear). Despite bearing the burden, see Kendall v. Visa U.S.A., Inc., 518 12 F.3d 1042, 1050-51 (9th Cir. 2008), Hynix has not even tried to show that any of the 103 13 particularized statements was a determination actually litigated, decided, and essential to Micron 14 II. Indeed, Hynix miscasts these statements as the Federal Circuits findings on certain factual 15 issues (Br. 19), even though the Federal Circuit clearly said [i]t is not our task to make factual 16 findings, Micron II, 645 F.3d at 1327. 17 What Hynix is attempting is exactly the ploy rejected in In re Microsoft, where the 18 plaintiff sought preclusion as to 356 specific factual issues on the basis of a prior judgment that 19 had been affirmed in part and reversed in part on appeal. 355 F.3d at 325. The Fourth Circuit 20 reversed the application of preclusion, explaining that only determinations that were necessary 21 and essential to the appellate courts holding could satisfy the necessity requirement. Id. at 22 327. The 103 statements listed by Hynix are just too particularized, and their precise role in the 23 ultimate holding too unclear, to be deemed critical, necessary, and essential to the Micron 24 II judgment. Cf. id. at 327-29; see also id. at 328 ([I]f a judgment in the prior case is supported 25 by either of two findings, neither finding can be found essential to the judgment). For example, 26 any statement regarding Rambuss conduct in 1998 is mere dicta, because Micron II did not 27 determine that litigation was foreseeable in that timeframe. The only factual ruling that could be 28 - 14 RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page20 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6

considered necessary and essential to the Micron II judgment is the Federal Circuits binary determination that it was not clear error to find that the duty to preserve arose before the second shred day. See Micron II, 645 F.3d at 1322.3 VI. JUDICIAL EFFICIENCY SUPPORTS THIS COURTS IMMEDIATE RESOLUTION OF HYNIXS UNCLEAN HANDS DEFENSE, AND NOT DEFERENCE TO THE DELAWARE COURT This Court has expressed concern with a race between getting a final determination in the Micron case and getting a final determination in the Hynix case. (6/3/11 RT 14.) Hynixs

7 proposed solution is for this Court to stay its hand out of deference to the Delaware Court. (Br. 8 26.) That approach, of course, would reward Hynix for the forum arbitrage that it and Micron 9 engaged in when they coordinated their filing of the declaratory judgment lawsuits. (CE Order 10 7.) And, of course, Hynixs coordination proposal ignores the fact that this Court tried and 11 resolved Hynixs unclean hands defense three years before the Delaware Court issued its ruling. 12 But even taken on the merits, Hynixs suggestion that deferring to the Delaware Court would be 13 the most judicially efficient way to proceed (Br. 26) is flatly wrong. While the Federal Circuit 14 affirmed the Delaware Courts spoliation determination, it vacated that Courts findings of bad 15 faith and prejudice. Because this Courts resolution of those issues is unaffected by the Federal 16 Circuits decisions, there are, in fact, fewer issues to be resolved on remand in this case. (Cf. 17 id.) This is especially so when spoliation is viewed, as it should be, in the context of the 18 litigations as a whole. This Court has already resolved the other claims and defenses on the 19 merits, and its rulings have been affirmed. In Delaware, all of the patent claims and some 20 defenses remained to be adjudicated. There can be no question, then, that resolving the discrete 21 issues necessary to carry out the mandate is plainly the most efficient way to a final judgment. 22 23 24 the existing factual record; (2) exercise its discretion against reopening the record or allowing any 25 discovery; and (3) re-enter judgment in Rambuss favor. 26 27 28 Another reason to deny preclusion on narrow factual issues is that it would unnecessarily complicate and distort the Courts decision-making on the remaining issues and its ultimate resolution of unclean hands. See Coburn v. Smithkline Beecham Corp., 174 F. Supp. 2d 1235, 1241 (D. Utah 2001). - 15 RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

3

CONCLUSION This Court should: (1) re-confirm its findings of no bad faith and no prejudice based upon

Case5:00-cv-20905-RMW Document4074

Filed10/14/11 Page21 of 21

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 - 16 RAMBUSS ANSWERING REMAND BRIEF CASE NO. CV-00-20905-RMW

DATED: October 14, 2011

MUNGER, TOLLES & OLSON LLP SIDLEY AUSTIN LLP McKOOL SMITH PC

By:

/s/ Gregory P. Stone Gregory P. Stone

Attorneys for RAMBUS INC.

You might also like

- Disney Motion To DismissDocument27 pagesDisney Motion To DismissTHROnlineNo ratings yet

- Redacted Public Version FNN Opening Brief in Dominion Case - With Leaked Dominion EmailsDocument169 pagesRedacted Public Version FNN Opening Brief in Dominion Case - With Leaked Dominion EmailsJim HoftNo ratings yet

- Hwang V Savage - Reply To Opposition To DemurrerDocument17 pagesHwang V Savage - Reply To Opposition To DemurrerTHROnlineNo ratings yet

- O'Bannon V NCAA - Reply Brief of Antitrust Plaintiffs in Support of Motion For Class CertificationDocument56 pagesO'Bannon V NCAA - Reply Brief of Antitrust Plaintiffs in Support of Motion For Class CertificationInsideSportsLawNo ratings yet

- Petition For Writ of Prohibition in Markeith Loyd V State of FloridaDocument28 pagesPetition For Writ of Prohibition in Markeith Loyd V State of FloridaReba Kennedy100% (2)

- 12-03-30 Microsoft Motion For Partial Summary Judgment Against MotorolaDocument30 pages12-03-30 Microsoft Motion For Partial Summary Judgment Against MotorolaFlorian Mueller100% (1)

- Cambria Doc Opp To Detention 4 LaceyDocument19 pagesCambria Doc Opp To Detention 4 LaceyStephen LemonsNo ratings yet

- Imasen Phillippine Manufacturing Corporation: G.R. No. 194884 October 22, 2014Document9 pagesImasen Phillippine Manufacturing Corporation: G.R. No. 194884 October 22, 2014Nadin MorgadoNo ratings yet

- Opp Mot Dismiss Western Sugar Co-Op V Archer-Daniels-MidlandDocument120 pagesOpp Mot Dismiss Western Sugar Co-Op V Archer-Daniels-MidlandLara PearsonNo ratings yet

- Brief in Support of Rambus Inc.'S Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of LawDocument36 pagesBrief in Support of Rambus Inc.'S Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Lawsabatino123No ratings yet

- Jackson Cert Opp Brief WesternSkyFinancial v. D.jacksonDocument42 pagesJackson Cert Opp Brief WesternSkyFinancial v. D.jacksonThalia SandersNo ratings yet

- MATSON TERMINALS, INC. v. INSURANCE COMPANY OF NORTH AMERICA Petition To Compel ArbitrationDocument30 pagesMATSON TERMINALS, INC. v. INSURANCE COMPANY OF NORTH AMERICA Petition To Compel ArbitrationACELitigationWatchNo ratings yet

- Google Motion To Dismiss AndroidDocument21 pagesGoogle Motion To Dismiss Androidjeff_roberts881No ratings yet

- "Additional Insured" Status and Rights - What Are The Obligations of The Insurer To The Additional InsuredDocument27 pages"Additional Insured" Status and Rights - What Are The Obligations of The Insurer To The Additional InsuredAmir KhosravaniNo ratings yet

- FDIC v. Killinger, Rotella and Schneider - STEPHEN J. ROTELLA AND DAVID C. SCHNEIDER'S MOTION TO DISMISSDocument27 pagesFDIC v. Killinger, Rotella and Schneider - STEPHEN J. ROTELLA AND DAVID C. SCHNEIDER'S MOTION TO DISMISSmeischerNo ratings yet

- 67-1 Mem Iso Doyn MTN To DismissDocument32 pages67-1 Mem Iso Doyn MTN To DismissCole StuartNo ratings yet

- Lenhoff UtaDocument28 pagesLenhoff UtaEriq GardnerNo ratings yet

- Muscle Milk Objection Final WC 030514Document26 pagesMuscle Milk Objection Final WC 030514Will ChamberlainNo ratings yet

- Appeal Isps Torrentfreak PDFDocument40 pagesAppeal Isps Torrentfreak PDFtorrentfreakNo ratings yet

- 26 - Oppn Re PIDocument138 pages26 - Oppn Re PISarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- 00590-20031014 RIAA Opp ProtectiveDocument18 pages00590-20031014 RIAA Opp ProtectivelegalmattersNo ratings yet

- Greene V Paramount MSJDocument33 pagesGreene V Paramount MSJTHROnlineNo ratings yet

- 67 - Campaign Response Re PJ DiscoveryDocument22 pages67 - Campaign Response Re PJ DiscoveryProtect DemocracyNo ratings yet

- Additional Counsel Listed On Signature Page.Document25 pagesAdditional Counsel Listed On Signature Page.sabatino123No ratings yet

- 16-05-17 Oracle Motion For JMOL On 'Fair Use'Document30 pages16-05-17 Oracle Motion For JMOL On 'Fair Use'Florian MuellerNo ratings yet

- 2018-08-24 Memorandum of Law (DCKT 128 - 0)Document31 pages2018-08-24 Memorandum of Law (DCKT 128 - 0)eriqgardnerNo ratings yet

- Chiquita Cross Motion To Disqualify Terry CollingsworthDocument16 pagesChiquita Cross Motion To Disqualify Terry CollingsworthPaulWolfNo ratings yet

- Dell LawsuitDocument34 pagesDell LawsuitMichael KrigsmanNo ratings yet

- Upreme Court, U.S.: NO. - O, . N 1.2 2010Document46 pagesUpreme Court, U.S.: NO. - O, . N 1.2 2010Matthew Seth SarelsonNo ratings yet

- Attorneys For Defendants Attorney General Edmund G. Brown JRDocument38 pagesAttorneys For Defendants Attorney General Edmund G. Brown JREquality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- 13-12-02 Nokia's Proposal For Sanctions Against Samsung and Quinn EmanuelDocument33 pages13-12-02 Nokia's Proposal For Sanctions Against Samsung and Quinn EmanuelFlorian MuellerNo ratings yet

- Winston & Strawn LLP: D ' S B R J IDocument33 pagesWinston & Strawn LLP: D ' S B R J ItorrentfreakNo ratings yet

- Barile - NFLX Class Cert BriefDocument21 pagesBarile - NFLX Class Cert BriefPeter BarileNo ratings yet

- Scientology v. Dandar: State Supreme Court ResponseDocument16 pagesScientology v. Dandar: State Supreme Court ResponseTony OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Blurred Lines Trial - Gaye Injunction Motion - Williams + Thicke v. Gaye PDFDocument22 pagesBlurred Lines Trial - Gaye Injunction Motion - Williams + Thicke v. Gaye PDFMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Appellants CasesDocument21 pagesAppellants Casesidris2111No ratings yet

- Chiquita Motion For Summary Judgment On Negligence Per SeDocument25 pagesChiquita Motion For Summary Judgment On Negligence Per SePaulWolfNo ratings yet

- Doster Opposition MootnessDocument61 pagesDoster Opposition MootnessChrisNo ratings yet

- Rambus'S Opp. To Hynix'S Mot. For Summary Judgment, Etc. CASE NO. 00-20905-RMWDocument64 pagesRambus'S Opp. To Hynix'S Mot. For Summary Judgment, Etc. CASE NO. 00-20905-RMWsabatino123No ratings yet

- Plaintiffs' Response To Defendant's Objection To Magistrate Order "Deeming" Certain Facts Established and "Striking" Certain Affirmative DefensesDocument76 pagesPlaintiffs' Response To Defendant's Objection To Magistrate Order "Deeming" Certain Facts Established and "Striking" Certain Affirmative DefensesAnonymous XkawRUfNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court of The United States: Petitioners, VDocument32 pagesSupreme Court of The United States: Petitioners, VlegalmattersNo ratings yet

- P ' R Blag' O - S J C N - 3:10 - 0257-JSW SF - 3021132Document22 pagesP ' R Blag' O - S J C N - 3:10 - 0257-JSW SF - 3021132Equality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- 161 Oppo To Omnibus & Joinders - RedactedDocument184 pages161 Oppo To Omnibus & Joinders - RedactedCole StuartNo ratings yet

- SBN SBN SBN: United States District Court Northern District of California San Jose DivisionDocument15 pagesSBN SBN SBN: United States District Court Northern District of California San Jose Divisionsabatino123No ratings yet

- 00614-20031121 Riaa ReplyDocument19 pages00614-20031121 Riaa ReplylegalmattersNo ratings yet

- Exhibit ADocument139 pagesExhibit Asabatino123No ratings yet

- News Corp HackingDocument58 pagesNews Corp HackingApril PetersenNo ratings yet

- GOOG Referrer SettlementDocument29 pagesGOOG Referrer SettlementBrandon.BaileyNo ratings yet

- Siegel Superman/Superboy Opposition To Summary Judgment Filing March 4, 2013Document443 pagesSiegel Superman/Superboy Opposition To Summary Judgment Filing March 4, 2013Jeff TrexlerNo ratings yet

- Ratner v. Kohler (Reply in Opposition To MTD)Document26 pagesRatner v. Kohler (Reply in Opposition To MTD)THROnlineNo ratings yet

- 15-10-14 Apple Motion For Summary Judgment Against EricssonDocument20 pages15-10-14 Apple Motion For Summary Judgment Against EricssonFlorian MuellerNo ratings yet

- Good Morning To You v. Warner Chappell - Happy Birthday To You Amended Cross Motions For Summary Judgment PDFDocument61 pagesGood Morning To You v. Warner Chappell - Happy Birthday To You Amended Cross Motions For Summary Judgment PDFMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Birthday SJMDocument61 pagesBirthday SJMEriq GardnerNo ratings yet

- ABS Entertainment v. CBS Radio (Remastering Issue)Document32 pagesABS Entertainment v. CBS Radio (Remastering Issue)Digital Music NewsNo ratings yet

- Ada Ramirez Initial Brief Eleventh CircuitDocument60 pagesAda Ramirez Initial Brief Eleventh CircuitMatthew Seth SarelsonNo ratings yet

- Chiquita Reply To Renewed Motion To RemandDocument16 pagesChiquita Reply To Renewed Motion To RemandPaulWolfNo ratings yet

- Watts Water v. Sidley (Sidley Motion For Summary Judgment)Document38 pagesWatts Water v. Sidley (Sidley Motion For Summary Judgment)Mike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- Arbitration Law and Practice in KenyaFrom EverandArbitration Law and Practice in KenyaRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (4)

- Show Temp PDFDocument1 pageShow Temp PDFsabatino123No ratings yet

- United States District Court Eastern District of Texas Marshall DivisionDocument4 pagesUnited States District Court Eastern District of Texas Marshall Divisionsabatino123No ratings yet

- United States District Court Eastern District of Texas Marshall DivisionDocument4 pagesUnited States District Court Eastern District of Texas Marshall Divisionsabatino123No ratings yet

- In The United States District Court Eastern District of Texas Marshall DivisionDocument2 pagesIn The United States District Court Eastern District of Texas Marshall Divisionsabatino123No ratings yet

- Innovative Display Technologies, LLC v. ZTE Corporation, Et Al.Document2 pagesInnovative Display Technologies, LLC v. ZTE Corporation, Et Al.sabatino123No ratings yet

- AtDocument1 pageAtsabatino123No ratings yet

- Innovative Blackberry DismissalDocument2 pagesInnovative Blackberry DismissaliphawkNo ratings yet

- Innovative Acer DismissalDocument1 pageInnovative Acer DismissaliphawkNo ratings yet

- United States District Court For The Eastern District of Texas Marshall DivisionDocument2 pagesUnited States District Court For The Eastern District of Texas Marshall Divisionsabatino123No ratings yet

- Innovative Microsft SettlementDocument2 pagesInnovative Microsft SettlementiphawkNo ratings yet

- Innovative Blackberry DismissalDocument2 pagesInnovative Blackberry DismissaliphawkNo ratings yet

- In The United States District Court For The Eastern District of Texas Marshall DivisionDocument33 pagesIn The United States District Court For The Eastern District of Texas Marshall Divisionsabatino123No ratings yet

- Defendants.: LITIOC/2100839v3/101022-0107Document4 pagesDefendants.: LITIOC/2100839v3/101022-0107sabatino123No ratings yet

- Innovative Markman OrderDocument58 pagesInnovative Markman OrderiphawkNo ratings yet

- Innovative Apple DismissalDocument1 pageInnovative Apple DismissaliphawkNo ratings yet

- Joint Motion To Dismiss: Arnan Orris Ichols RSHT UnnellDocument2 pagesJoint Motion To Dismiss: Arnan Orris Ichols RSHT Unnellsabatino123No ratings yet

- Innovative Canon DismissalDocument2 pagesInnovative Canon DismissaliphawkNo ratings yet

- PlaintiffDocument3 pagesPlaintiffsabatino123No ratings yet

- IAM Magazine Issue 67 - Hands-On CounselDocument5 pagesIAM Magazine Issue 67 - Hands-On Counselsabatino123No ratings yet