Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Play Intrinsic Rewards Csik JHumanistic Psy 1976

Play Intrinsic Rewards Csik JHumanistic Psy 1976

Uploaded by

Divya PriyaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Play Intrinsic Rewards Csik JHumanistic Psy 1976

Play Intrinsic Rewards Csik JHumanistic Psy 1976

Uploaded by

Divya PriyaCopyright:

Available Formats

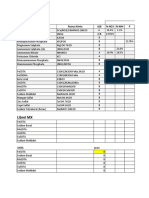

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/232482800

Play and Intrinsic Rewards: a Reply To

Csikszentmihalyi

Article in Journal of Humanistic Psychology · July 1976

DOI: 10.1177/002216787601600312

CITATIONS READS

9 1,859

1 author:

Lynn Barnett

University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

41 PUBLICATIONS 1,938 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Lynn Barnett on 16 May 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Journal of Humanistic

Psychology

http://jhp.sagepub.com/

Play and Intrinsic Rewards: a Reply To Csikszentmihalyi

Journal of Humanistic Psychology 1976 16: 83

DOI: 10.1177/002216787601600312

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://jhp.sagepub.com/content/16/3/83

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Association for Humanistic Psychology

Additional services and information for Journal of Humanistic Psychology can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://jhp.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://jhp.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://jhp.sagepub.com/content/16/3/83.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Jul 1, 1976

What is This?

Downloaded from jhp.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 16, 2014

PLAY AND INTRINSIC REWARDS:

A REPLY TO CSIKSZENTMIHALYI

LYNN BARNETT received her bachelor’s degree with a major

in clinical psychology and minor in mathematics and computer

science at the University of Illinois. She became interested in the

study of the theoretical nature of children’s play while a grad-

uate student pursuing a master’s degree in leisure studies. For

the past several years she has extensively researched current

arousal-seeking models, adopting an information-processing

explanation for children’s playful behavior. Ms. Barnett is cur-

rently completing her doctoral work examining the relationship

between learning and problem solving in preschool children’s

play behavior. She is currently teaching a research methods course on the undergraduate

level and a theories of play class on the graduate level. She has spoken at various confer-

ences discussing theoretical formulations of play and their implications and is currently

preparing several publications providing data on theoretical models and methodological

techniques in the study of play.

Definitions of intrinsic motivation have historically evolved along two

lines. Early thought viewed play from an activity-based perspective as

compensatory or restorative from work, play being defined as any activity

engaged in during nonwork, or free time (Groos, 1898; Gulick, 1902;

Patrick, 1916). This concept provided little descriptive power because

activities could not be categorized along other comparative dimensions,

nor could all leisure time activities so defined be considered &dquo;fun&dquo; or

&dquo;enjoyable&dquo; per se. As a recent alternative it has been suggested play be

regarded from the player’s perspective; that is, any activity initiated for

the sheer enjoyment or intrinsic reward presented to the individual should

define the activity as playful (Ellis, 1973; Millar, 1968; Reilly, 1974).

Theorists have differed in ascribing characteristics to feelings of intrinsic

reward, ranging from deriving feelings of mastery and competence

(White, 1959), skill acquisition (Sylva, 1974), and exploratory learning

(Reilly, 1974), from the engagement in the activity. Although differing in

assigning labels to the feelings of enjoyment derived during a playful

activity, the agreement here seems to be in focusing attention on the

player’s reasons for initiating the activity rather than on the activity itself.

Play is thus defined as the initiation of a response which is intrinsically

rewarding for the individual, the process itself presenting enjoyment and

resulting in feelings of satisfaction. This perspective presents a useful

approach in differentiating between intrinsically motivated, or playful

J. Humanistic Psychology Vol 16, No 3, Summer 1976 83

Downloaded from jhp.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 16, 2014

84

activities, and extrinsically motivated, or task-oriented activities. The

former can be characterized by the means or process while the latter refers

to the goal or outcome. In this way, we can think of the distinction between

extrinsic and intrinsic motivation as lying along a continuum with activ-

ities initiated to achieve an external reward on one end and those moti-

vated by the pleasure derived by the individual at the other extreme. This

notion that play be best described by the intention of the &dquo;player&dquo; is also

useful in circumscribing observations that certain aspects of work can

often be &dquo;playful&dquo; and that play often seems like &dquo;serious business.&dquo;

1. Csikszentmihalyi’s (1975) flow model seems to be contradictory in dis-

tinguishing play as an activity from play as a function of the state of mind

of the participant. Flow is defined initially as an enjoyable sensation but is

later described as being wholly dependent on flow activities. Quoting

Csikszentmihalyi, flow activities are &dquo;those structured systems of action

which usually help to produce flow experiences [p. 55].&dquo; If we follow this

line of thinking, it is suggested here that activities can be characterized by

some unidimensional criteria as &dquo;flow-producing&dquo; (i.e., intrinsically moti-

vating). Thus, we need not consider the perception of the participant, but

rather we can assume that anyone engaging in that activity is playing.) In

suggesting implications which can be drawn from the flow model, the

author suggests several practical settings (e.g., job and school contexts) be

restructured to provide flow activities. &dquo;These considerations suggest that

it is possible to order structured activities and situations in terms of

whether they are more or less intrinsically rewarding, depending on the

intensity of flow they allow a person to experience [p. 60].&dquo; The alternative

I would like to present is that structured settings be modified to allow the

individual the opportunity to interact in whatever manner is intrinsically

rewarding to himself, rather than to structure activities within the setting

to conform to what one individual feels would be enjoyable to others (see

Gramza, 1971, 1972).

At other points in his article, Csikzentmihalyi attributes intrinsic moti-

vation to the perception of the individual. He relents in the above argu-

ment in suggesting that &dquo;personality differences probably result in differ-

ential responsiveness to flow activities [p. 61].&dquo; In outlining the flow model

the author states that the objective nature of the activity itself is not

enough to characterize a person as being &dquo;in flow,&dquo; but rather the subjec-

tive evaluation of the individual must be considered.

I find further argument with some of the elements of the flow experi-

ences presented. In discussing the interaction of action and awareness as a

crucial variable indicating the onset of flow, the author states that &dquo;flow is

Downloaded from jhp.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 16, 2014

85

difficult to maintain for any length of time without at least momentary

interruptions.&dquo; Any naive observer of children’s play, or that of adults for

that matter, could describe the long and continuous durations of activity

sometimes with only one object. (This has been found in animal play also.

See Beach, 1945; Berlyne, 1960; Harlow, Harlow, & Meyer, 1950). At a

later point in the article, Csikszentmihalyi writes that nonflow states are

also difficult to sustain for any appreciable length. How then, does this

element become a meaningful way to distinguish between flow and

nonflow activities?

2. Flow activities are described as most frequently appearing in activities

which present clearly defined boundaries and rules for action. If this were

true, we should see very little play in preschool children. Piaget (1932)

discusses the nature of rules in games as a context in which to examine the

development of morality in the child. According to Piaget’s formulation,

an appreciation and strict adherence to rules is not shown in children until

about the age of eight. Before this age, children progress from no restric-

tions in their playful interactions with others (egocentricity) to the recog-

nition of rules but amenable to the child’s own modifications without

justification.

3. In elaborating further on game structure, Csikszentmihalyi writes,

&dquo;... rules alone are not always enough to get a person involved with the

game. Hence the structure of games provides motivational elements which

will draw the player into play [p. 48].&dquo; The suggestion here is that there

exists an extrinsically based motivational cause, or at least reasons exter-

nal to the individual which induce participation. This seems to defy the

whole notion of intrinsic motivation presumed to motivate the individual

to participate in an activity. Again the assumption appears that the activity

itself defines the characterization of it as playful, rather than the motive of

the player.

4. A further element of a flow experience is described as &dquo;loss of ego [p.

49].&dquo; Although it might seem to be a semantic argument, might I suggest

that instead this element be termed &dquo;ego-ful&dquo; if we conform to current

thinking that an intrinsically motivating activity is one initiated for the

individual’s own pleasure, one engaged in for the unique sense of enjoy-

ment it offers to the individual.

5. On a more theoretical level, the model presented is merely a restate-

ment, and less elegantly so, of optimal arousal theories (Hebb, 1955;

Helson, 1959; Lueba, 1955) and their application to play behavior as

stimulus- or arousal-seeking activity (Barnett, 1974; Ellis, 1969, 1973).

Within this framework play is presumed to be motivated by the need to

Downloaded from jhp.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 16, 2014

86

maintain an optimal level of stimulation, or in Schultz’s (1965) term a

sensoristatic drive. Rather than varying states of stimulation being de-

pendent on either the objective challenges presented by the setting, or on

the level of skill development of the individual, a more general classifica-

tion is to view it as a function of varying degrees of informational uncer-

tainty (Berlyne, 1960; Hunt, 1963). The use of terms such as anxiety,

worry, and boredom place unnecessary limitations on the resultant states

of being sub- or supra-optimally aroused.

6. Finally, may I take issue with one of the latter parts of a statement

expressed in the paper, &dquo;... Most people need some inducement to parti-

cipate in flow activities, at least at the beginning, before they learn to be

sensitive to intrinsic rewards [p. 48].&dquo; Although there is little data to

suggest that play is genetically determined (although Maddi [1961] and

others argue that play be most appropriately considered a personality

dimension) there is no data to my knowledge to suggest either that play is

environmentally learned. In fact, the observation that infants play sug-

gests some discrepancy to this statement. It would seem a more useful

starting point to assume that the ability to play is in actuality innate rather

than to assume it is not and place qualitiative value judgments on the

typology of play as the child develops.

REFERENCES

BARNETT, L. A. An information processing model of children’s play behavior.

Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, 1974.

BEACH, F. A. Current concepts of play in animals. American Naturalist, 1945, 79,

523-541.

BERLYNE, D. E. Conflict, arousal and curiosity. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1960.

CSIKSZENTMIHALYI, M. Play and intrinsic rewards. Journal of Humanistic Psy-

, 15

chology 1975

(3), 41-63.

,

ELLIS, M. J. Sensorhesis as a motive for play and stereotyped behavior. Children’s

Research Center Internal Report, 1969.

ELLIS, J. J. Why people play. Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall, 1973.

GRAMZA, A. F. New directions for the design of play environments. Paper pre-

sented at the National Symposium on Park, Recreation, and Equipment De-

sign, February 16, 1971, Chicago, Illinois.

GRAMZA, A. F. Children’s play and stimulus factors of the physical environment.

Children’s Research Center Internal Report, 1972.

GROOS, K. [The play of animals

.] (E. L. Baldwin, trans.). New York: Appleton,

1898.

GULICK, L. Interest in relation to muscular exercise. American Physical Education

Review, 1902,

, 57-65.

1

Downloaded from jhp.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 16, 2014

87

HARLOW, H. F., HARLOW, M. K., & MEYER, D. R. Learning motivated by a

manipulation drive. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 1950,

, 228-234.

40

HEBB, D. O. Drives and the C.N.S. (conceptual nervous system). Psychological

Review, 1955,

, 243-254.

62

HELSON, H. Adaptation-level theory. In S. Koch (Ed.), Psychology: A study of a

science. Vol. I. Sensory, perceptual and physiological formulation. New York:

McGraw-Hill, 1959.

HUNT, J. Mc.V. Motivation inherent in information processing and action. In O. J.

Harvey (Ed.), Motivation and social interaction: The cognitive determinants.

New York: Ronald Press, 1963.

LEUBA, C. Toward some integration of learning theories: The concept of optimal

stimulation. Psychological Reports, 1955, 1

, 27-33.

MADDI, S. Exploratory behavior and variation-seeking in man. In D. Fiske, & S.

Maddi (Eds.), Functions of varied experience. Homewood, Ill.: Dorsey Press,

1961.

MILLAR, S. The psychology .

of play Baltimore: Penguin, 1968.

PATRICK, G. T. W. The psychology of relaxation. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1916.

PIAGET, J. The moral judgment of the child. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1932.

REILLY, M. (Ed.). Play as exploratory learning. California: Sage Publications,

1974.

SCHULTZ, D. D. Sensory restriction: Effects on behavior. New York: Academic

Press, 1965.

SYLVA, K. The relationship between play and problem-solving in children 3-5

years old. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, 1974.

WHITE, R. W. Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychologi-

cal Review, 1959,

, 297-333.

66

Reprint requests: L. A. Barnett, Leisure Behavior Research Laboratory, 97 Institute for

Child Behavior and Development, 51 Gerty Drme, Champaign, Illinois 61820

Downloaded from jhp.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 16, 2014

View publication stats

You might also like

- Social Identity and Intergroup Behaviour-TajfelDocument30 pagesSocial Identity and Intergroup Behaviour-TajfelJuli SerranoNo ratings yet

- Ontological Psychoanalysis or "What Do You Want To Be When You Grow Up?"Document25 pagesOntological Psychoanalysis or "What Do You Want To Be When You Grow Up?"Juan Diego González Bustillo100% (1)

- (Antoine Panaioti) Nietzsche and Buddhist PhilosopDocument259 pages(Antoine Panaioti) Nietzsche and Buddhist PhilosopFernando Lastlil100% (1)

- 13bowman Lieberoth Psychology FINALDocument44 pages13bowman Lieberoth Psychology FINALJuan Alberto GonzálezNo ratings yet

- 13bowman Lieberoth Psychology FINALDocument44 pages13bowman Lieberoth Psychology FINALThrowaway EmailNo ratings yet

- Abele, S., Stasser, G., & Chartier, C. (2010) - Conflict and Coordination in The Provision of Public GoodsDocument18 pagesAbele, S., Stasser, G., & Chartier, C. (2010) - Conflict and Coordination in The Provision of Public GoodsSamuel FonsecaNo ratings yet

- (2008) Frosh & Baraister Psychoanalysis - and - Psychosocial - StudiesDocument21 pages(2008) Frosh & Baraister Psychoanalysis - and - Psychosocial - StudiesAndreia Almeida100% (1)

- Panzarella (1980) Phenomenology of Aesthetic Peak Experiences (Journal of Humanistic Psychology)Document18 pagesPanzarella (1980) Phenomenology of Aesthetic Peak Experiences (Journal of Humanistic Psychology)onyame3838No ratings yet

- BOWMAN, Sarah Lynne. Immersion and Shared Imagination in Role Playing GamesDocument46 pagesBOWMAN, Sarah Lynne. Immersion and Shared Imagination in Role Playing GamesChris Alexsander MartinsNo ratings yet

- Framework - Organization Behavior HRDDocument3 pagesFramework - Organization Behavior HRDsmash2bobbyNo ratings yet

- Feng 2017 A Cross-Cultural Exploration of Imagination As A Process-Based Concept - ScaleDocument27 pagesFeng 2017 A Cross-Cultural Exploration of Imagination As A Process-Based Concept - Scale29Thanh Phong Nguyễn HuỳnhNo ratings yet

- 16-As You Would Have Them Do Unto You - Does Imagining Yourself in The Other's Place Stimulate Moral ActionDocument13 pages16-As You Would Have Them Do Unto You - Does Imagining Yourself in The Other's Place Stimulate Moral ActionNur Khairina RosliNo ratings yet

- Is Psychoanalysis A Social Science?Document23 pagesIs Psychoanalysis A Social Science?CyLo PatricioNo ratings yet

- Bodrova, 2013. Play and Self-Regul VigostkyDocument14 pagesBodrova, 2013. Play and Self-Regul VigostkyStephanie HernándezNo ratings yet

- Aesthetics and PsychobiologyDocument8 pagesAesthetics and PsychobiologyDavid RojasNo ratings yet

- Undermine Children's InterestDocument10 pagesUndermine Children's InterestShang ChuNo ratings yet

- Spinrad Eisenberg Fabes Spinrad2006 1Document73 pagesSpinrad Eisenberg Fabes Spinrad2006 1LiaCoitaNo ratings yet

- Undermining Childrens Intrinsic Interest With ExtDocument10 pagesUndermining Childrens Intrinsic Interest With ExtmglhealNo ratings yet

- 16 PDFDocument10 pages16 PDFIrina IgnatNo ratings yet

- Munoz-Blanco 2017Document15 pagesMunoz-Blanco 2017Robert JohanssonNo ratings yet

- The Automaticity of Everyday Life - Advances in Social Cognition (1997)Document267 pagesThe Automaticity of Everyday Life - Advances in Social Cognition (1997)curiositykillcat50% (2)

- Meaning in Everyday LifeDocument3 pagesMeaning in Everyday LifeAnte BuraNo ratings yet

- Pathology As - Personal Growth - A Participant-Observation Study of Lifespring TrainingDocument7 pagesPathology As - Personal Growth - A Participant-Observation Study of Lifespring TrainingDantalion JonesNo ratings yet

- Brushlinskii, A. V. (1987) - Activity, Action, and Mind As Process. Soviet Psychology, 25 (4), 59-81Document24 pagesBrushlinskii, A. V. (1987) - Activity, Action, and Mind As Process. Soviet Psychology, 25 (4), 59-81glauber stevenNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument8 pagesAnnotated BibliographyJaspreet GillNo ratings yet

- 02 Fiske, Cap 1Document32 pages02 Fiske, Cap 1Nelson DiazNo ratings yet

- SchiologyDocument11 pagesSchiologyJayden AdrianNo ratings yet

- Joann Peck, Suzanne B. Shu - Psychological Ownership and Consumer Behavior (2018, Springer International Publishing)Document278 pagesJoann Peck, Suzanne B. Shu - Psychological Ownership and Consumer Behavior (2018, Springer International Publishing)Afareen House100% (1)

- Tajfel 1986 Social Pychology of Intergroup RelationsDocument41 pagesTajfel 1986 Social Pychology of Intergroup RelationshoorieNo ratings yet

- Volume 15 No.1-2009 - Artikel5Document8 pagesVolume 15 No.1-2009 - Artikel5Tri HeniNo ratings yet

- Who Sees Human The Stability and Importance of IndDocument16 pagesWho Sees Human The Stability and Importance of IndispNo ratings yet

- 2021 Lübbert Gonzalez-Fernandez Heimann - Playful AcademicDocument19 pages2021 Lübbert Gonzalez-Fernandez Heimann - Playful AcademicPedro González FernándezNo ratings yet

- The Theory of Planned Behavior: Selected Recent Advances and ApplicationsDocument5 pagesThe Theory of Planned Behavior: Selected Recent Advances and ApplicationsConcurseiroEvpNo ratings yet

- Individual Differences Mischel, Walter.: Harcourt Brace & CompanyDocument24 pagesIndividual Differences Mischel, Walter.: Harcourt Brace & CompanyatelieruldebijuteriiNo ratings yet

- Bretherton Et Al. - Learning To Talk About Emotions. A Functionalist PerspectiveDocument22 pagesBretherton Et Al. - Learning To Talk About Emotions. A Functionalist PerspectiveSofi AlonsoNo ratings yet

- Ontological Psychoanalysis SubrayadoDocument25 pagesOntological Psychoanalysis SubrayadoDaniella BrahimNo ratings yet

- The Role of Play in Social-Intellectual Development: James F. Christie and E. P. JohnsenDocument23 pagesThe Role of Play in Social-Intellectual Development: James F. Christie and E. P. JohnsenRoman RuanNo ratings yet

- Two Dimensions of MotivationDocument13 pagesTwo Dimensions of MotivationDiane Verdera0% (1)

- Origins of Social MindDocument7 pagesOrigins of Social MindLourival BezerraNo ratings yet

- Social Group Project NewwwwwwwDocument36 pagesSocial Group Project NewwwwwwwMuskan KhatriNo ratings yet

- Textbook The Students Guide To Social Neuroscience 2Nd Edition Jamie Ward Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook The Students Guide To Social Neuroscience 2Nd Edition Jamie Ward Ebook All Chapter PDFben.nam565100% (3)

- Gerald Young (Auth.) - Unifying Causality and Psychology - Being, Brain, and Behavior-Springer International Publishing (2016) PDFDocument962 pagesGerald Young (Auth.) - Unifying Causality and Psychology - Being, Brain, and Behavior-Springer International Publishing (2016) PDFmar1940100% (1)

- An Ecological Account of Visual Illusions - Favela - and - ChemeroDocument26 pagesAn Ecological Account of Visual Illusions - Favela - and - ChemeroTim Hardwick100% (1)

- Radford - Roth A Cultural-Historical Perspective On Mathematics-4Document191 pagesRadford - Roth A Cultural-Historical Perspective On Mathematics-4Maleja BustgomezNo ratings yet

- philcompass-philosophyofgamesv2-2Document42 pagesphilcompass-philosophyofgamesv2-2Elvin BlancoNo ratings yet

- Sliwinski2018 Article DesigningandEvaluatingGamesforMindfulnessDocument16 pagesSliwinski2018 Article DesigningandEvaluatingGamesforMindfulnessRodrigo Manoel GiovanettiNo ratings yet

- Reading My Mind: A Personal Journal: From Retired School Teacher to Professional Remote ViewerFrom EverandReading My Mind: A Personal Journal: From Retired School Teacher to Professional Remote ViewerRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Full Download Test Bank For Psychology and Life 20th Edition Richard J Gerrig PDF Full ChapterDocument36 pagesFull Download Test Bank For Psychology and Life 20th Edition Richard J Gerrig PDF Full Chapterdulcifyzonall2vpr100% (26)

- Human Perception: A Comparative Study of How Others Perceive Me and How I Perceive MyselfDocument25 pagesHuman Perception: A Comparative Study of How Others Perceive Me and How I Perceive MyselfKimber Crizel PinedaNo ratings yet

- Byrne 1997Document15 pagesByrne 1997cutkilerNo ratings yet

- An Invitation To The Sociology of Emotions 2Nd 2Nd Edition Scott R Harris Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFDocument69 pagesAn Invitation To The Sociology of Emotions 2Nd 2Nd Edition Scott R Harris Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFwilliam.mcconnell605100% (14)

- Research Thesis: B.Arch - V Topic: Recreation - The Space As Public EmergesDocument5 pagesResearch Thesis: B.Arch - V Topic: Recreation - The Space As Public EmergesGaurav GajeraNo ratings yet

- 8 Shadrikov Kurginyan Martynova Psikholo.. - Razmyshlenie o Kontsepte MyslDocument19 pages8 Shadrikov Kurginyan Martynova Psikholo.. - Razmyshlenie o Kontsepte Mysldaniyal chNo ratings yet

- Hortensius de Gelder 2018 From Empathy To Apathy The Bystander Effect RevisitedDocument8 pagesHortensius de Gelder 2018 From Empathy To Apathy The Bystander Effect Revisitediulialazar2023No ratings yet

- The Epistemics of Make-BelieveDocument26 pagesThe Epistemics of Make-Believees2344No ratings yet

- Grounding PDFDocument53 pagesGrounding PDFKarina Andrea Torres OcampoNo ratings yet

- Divergent Thinking - WikipediaDocument18 pagesDivergent Thinking - WikipediaGita Indra HariesdaNo ratings yet

- Agnitio ManuscriptDocument59 pagesAgnitio ManuscriptChiisay UmiNo ratings yet

- Play in Child DevelopmentDocument194 pagesPlay in Child DevelopmentSiyah Point100% (2)

- "Theologization" of Psychology and "Psychologization"Document10 pages"Theologization" of Psychology and "Psychologization"khozinNo ratings yet

- Proof of An External WorldDocument3 pagesProof of An External WorldFarri93No ratings yet

- Blazevideo HDTV Player V6.0R User'S ManualDocument17 pagesBlazevideo HDTV Player V6.0R User'S ManualGianfranco CruzattiNo ratings yet

- Build A Garden Pond: Home ProjectDocument4 pagesBuild A Garden Pond: Home ProjectRendel RosaliaNo ratings yet

- Technoir Players GuideDocument16 pagesTechnoir Players GuideDerrick D. Cochran100% (1)

- Technical Information: Dpbs 90 E MeDocument3 pagesTechnical Information: Dpbs 90 E MeЛулу ТраедNo ratings yet

- Metrology CH 3Document52 pagesMetrology CH 3Eng Islam Kamal ElDin100% (1)

- Ce503 RBTDocument2 pagesCe503 RBTTarang ShethNo ratings yet

- Avesta Welding Manual - 2009-03-09 PDFDocument312 pagesAvesta Welding Manual - 2009-03-09 PDFkamals55No ratings yet

- Final PresentationDocument18 pagesFinal Presentationradziahkassim100% (1)

- The Effect of Elevated Temperature On ConcreteDocument204 pagesThe Effect of Elevated Temperature On Concretexaaabbb_550464353100% (1)

- Death in The Blue Ocean: by Caleb SmithDocument193 pagesDeath in The Blue Ocean: by Caleb SmithpolarisincNo ratings yet

- DT 900 Pro X: FeaturesDocument1 pageDT 900 Pro X: FeaturestristonNo ratings yet

- Excel Meracik Nutrisi Bandung 11 Feb 2018Document30 pagesExcel Meracik Nutrisi Bandung 11 Feb 2018Ariev WahyuNo ratings yet

- 3bhs823693 Zab E11 D Megastar TC SW Amc TableDocument99 pages3bhs823693 Zab E11 D Megastar TC SW Amc TablesepulcrijkdNo ratings yet

- LPile 2015 Technical ManualDocument238 pagesLPile 2015 Technical ManualMahesh HanmawaleNo ratings yet

- Mens TshirtDocument15 pagesMens TshirtTrung Hieu NguyenNo ratings yet

- SP-1102A Specification For Design of 33kV Overhead Power Lines On Wooden PolesDocument118 pagesSP-1102A Specification For Design of 33kV Overhead Power Lines On Wooden Polesarjunprasannan7No ratings yet

- Vertex MaxDocument20 pagesVertex MaxAušra PoderėNo ratings yet

- I Rod Nu Bolt Product OverviewDocument6 pagesI Rod Nu Bolt Product Overviewjamehome85No ratings yet

- Hardy ObituaryDocument2 pagesHardy ObituaryNewzjunkyNo ratings yet

- Sweet Corn and Cheese Samoosa - Google SearchDocument2 pagesSweet Corn and Cheese Samoosa - Google SearchmisslxmasherNo ratings yet

- Dip & StrikeDocument20 pagesDip & StrikeSajjad AzizNo ratings yet

- 1Document11 pages1putriNo ratings yet

- Topic 6 Circular Motion Test P1Document11 pagesTopic 6 Circular Motion Test P1Sabrina_LGXNo ratings yet

- Peugeot 206 P Dag Owners ManualDocument119 pagesPeugeot 206 P Dag Owners ManualAlex Rojas AguilarNo ratings yet

- 7 QC Tools: Training Module OnDocument38 pages7 QC Tools: Training Module OnKaushik SenguptaNo ratings yet

- Modeling of Batch Fermentation Kinetics For Succinic Acid Production by Mannheneimia SucciniciproducensDocument9 pagesModeling of Batch Fermentation Kinetics For Succinic Acid Production by Mannheneimia SucciniciproducensRyuuara Az-ZahraNo ratings yet

- Book's SolutionsDocument20 pagesBook's SolutionsKodjo ALIPUINo ratings yet

- Sabbaba MenuDocument8 pagesSabbaba Menuaresha6881No ratings yet