Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Psychotic Depression: Diagnosis, Differential Diagnosis, and Treatment

Psychotic Depression: Diagnosis, Differential Diagnosis, and Treatment

Uploaded by

Michael UOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Psychotic Depression: Diagnosis, Differential Diagnosis, and Treatment

Psychotic Depression: Diagnosis, Differential Diagnosis, and Treatment

Uploaded by

Michael UCopyright:

Available Formats

Standard Review Article

Psychother Psychosom 2021;90:160–177 Received: June 7, 2020

Accepted: August 30, 2020

DOI: 10.1159/000511348 Published online: November 9, 2020

Psychotic Depression: Diagnosis,

Differential Diagnosis, and Treatment

Steven L. Dubovsky a, b Biswarup M. Ghosh a Jordan C. Serotte a

Victoria Cranwell a

Downloaded from http://karger.com/pps/article-pdf/90/3/160/3908896/000511348.pdf by guest on 02 December 2023

a Department

of Psychiatry, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY,

USA; b Departments of Psychiatry and Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver, CO, USA

Keywords Introduction

Affective disorders · Antidepressants · Antipsychotics ·

Bipolar depression · Depressive disorder · Psychosis · Some clinicians believe that because modern rapid

Psychotic depression · Mood disorders treatment of depression prevents it from becoming more

severe, the development of psychotic features is now rare.

In fact, psychotic depression remains a common condi-

Abstract tion that is often underrecognized and inadequately treat-

Psychotic depression was initially considered to be at one ed. This review addresses the complex ways in which psy-

end of a continuum of severity of major depression. Subse- chosis can complicate mood disorders and the ways in

quent experience demonstrated that psychosis is an inde- which it alters their course and treatment response. Typ-

pendent trait that may accompany mood disorders of vary- ical features that have been studied formally are outlined,

ing severity. While much has been learned about the impact and case examples are used to illustrate more subtle or

of severe mood congruent delusions and hallucinations on complex presentations and treatment approaches.

the course and treatment response of depression, less is

known about fleeting or mild psychosis, mood incongruent

features, or psychotic symptoms that reflect traumatic expe- Evolution of the Concept of Psychotic Depression

riences. Acute treatment of psychotic unipolar depression

generally involves the combination of an antidepressant and The definition of psychotic depression has evolved so

an antipsychotic drug or electroconvulsive therapy. There is much over the years that it is difficult to apply experience

inadequate information about maintenance treatment of with earlier diagnostic criteria to more recent experience

unipolar psychotic depression and acute and chronic treat- [1]. As psychosis was defined in the second edition of the

ment of psychotic bipolar disorder. Decision-making there- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

fore still must rely in part on clinical experience. (DSM-II) [2] as being so impaired mentally that the pa-

© 2020 S. Karger AG, Basel tient could not adapt to “the ordinary demands of daily

life” [3], psychotic depression was defined solely by severe

karger@karger.com © 2020 S. Karger AG, Basel Steven L. Dubovsky

www.karger.com/pps Department of Psychiatry, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences

University at Buffalo, 462 Grider St

Buffalo, NY 14215 (USA)

dubovsky @ buffalo.edu

impairment [4], with or without the presence of delusions NOS) severity rating scale were entirely attributable to the

and hallucinations, which are traditional defining fea- hallucinations/delusions subscale [13]. When psychosis

tures of psychosis [3]. In this formulation, psychotic de- was defined only as the presence of hallucinations or de-

pression is at one end of a spectrum of severity and not a lusions, severity of depression was similar in the psychot-

distinct disorder. ic and nonpsychotic groups, and severity of depression

After reports that major depression with delusions had was only weakly correlated with severity of psychosis

a different treatment response than major depression [13]. In a recent prospective study of 288 depressed inpa-

without delusions [3], the definition of psychotic depres- tients, severity of depression was equivalent in the 45% of

sion was modified in DSM-III [5] to require delusions, patients with psychotic and the 55% with nonpsychotic

hallucinations, or depressive stupor [3]. Although DSM- depression, although functional impairment was greater

III eliminated severe impairment as the primary criterion in the psychotic patients [14].

for psychosis, this criterion remained in the Internation- While psychotic depression is often severe, patients

al Classification of Diseases (ICD), especially if endoge- may have equally severe depression without psychosis

nous features were present [1]. In ICD-10 [6], the version [12], and some cases of depression without hallucinations

that will continue until 2022, psychotic depression is still or delusions are associated with greater depression sever-

Downloaded from http://karger.com/pps/article-pdf/90/3/160/3908896/000511348.pdf by guest on 02 December 2023

classified as a type of severe major depression [4]. How- ity than are cases of depression with psychosis [13]. Since

ever, the subsequent version (ICD-11) [7] includes hal- nonpsychotic episodes in patients with a history of psy-

lucinations and delusions along with severity as diagnos- chotic depression are often briefer than, and not as severe

tic criteria. In other diagnostic systems, the concept of as, psychotic episodes, it may be that a certain level of se-

psychotic depression has variously included a level of se- verity of the mood disorder is necessary for a propensity

verity that leads to distortion of reality, melancholic de- of psychosis initially to emerge [15]. Once it does, which

pression, endogenous depression, or the opposite of neu- is often after several episodes of nonpsychotic depression,

rotic depression (defined in this context as depression psychosis tends to recur with subsequent episodes, which

with a psychosocial etiology) [8]. All of these classifica- may not be as severe [16]. Although psychosis may not

tions considered psychotic depression to be a severe sub- inevitably accompany every subsequent depressive epi-

type of major depressive disorder (MDD). An implica- sode, once it has occurred it functions as an independent

tion of this concept is that a more severe version of MDD feature of depression that alters the mood disorder in fun-

may simply require more of the same treatment as other damental ways [13] that differentiate it from other forms

presentations, rather than a different therapeutic ap- of depression [11, 17]. Insofar as it is psychosis rather

proach required by a distinct illness. than severity of depression that appears to alter the course

In DSM-IV [9], psychotic depression became a severe and treatment response of mood disorders, an essential

subtype of MDD characterized by delusions or hallucina- clinical task is to identify psychosis in depressed patients,

tions [4]. In DSM-5 [10], psychotic depression is still a particularly those who are not responding as expected to

subtype of MDD rather than a separate disorder, but the antidepressant therapy. In clinical practice, psychosis

psychosis specifier is independent of severity, so that de- may be less obvious than it is in patients who have been

pression does not have to be severe to justify a diagnosis studied in clinical trials.

of psychotic depression [4]. In fact, DSM-5 permits psy-

Case example: A 30-year-old graduate student had been treated

chotic features with dysthymia as well as major depres- with multiple antidepressants for depressed mood associated with

sion, acknowledging the idea that psychotic features are anhedonia, early morning awakening, low energy and motivation,

not just a function of severity of depression [11]. This decreased appetite, and social withdrawal. He had experienced a

change reflects an understanding that many depressive previous major depressive episode (MDE) that responded well to

disorders can occur with or without psychosis, with dif- a single antidepressant and remitted completely. The antidepres-

sant was continued for 1 year and then withdrawn, after which he

ferent implications for treatment and prognosis [12]. remained well for 2 more years. A recurrence of depression pre-

Accumulating research supports the impression that cipitated by a romantic disappointment did not respond to the

psychosis is not inextricably linked to severity of depres- same antidepressant. Despite cognitive dysfunction consisting pri-

sion [11]. In a study of 357 inpatients (mean age 56–58 marily of difficulty concentrating and mild dissociative symptoms,

years, mean length of stay 44–50 days) with ICD-10 se- the patient continued to do well academically. He was less sociable

because he felt that people might be laughing at him, but he was

vere depression, one-third of whom had psychotic fea- not profoundly withdrawn. He was cooperative with the clinician,

tures, higher scores in psychotically depressed patients on but when pressed about how he felt about being examined, he said

the 12-item Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (Ho- that he thought that the clinician might be gathering information

Psychotic Depression Psychother Psychosom 2021;90:160–177 161

DOI: 10.1159/000511348

to be used against him for unspecified purposes. He sometimes 15% of schizophrenia probands have a bipolar family his-

thought that he heard whispering, but he was not sure. When asked tory [29]. The transdiagnostic property of psychosis is

about noticing unusual smells, he replied, “just rotting flesh.” In

reply to inquiry about other unusual sensations, he said, “just a supported by a Danish birth cohort study showing that

taste of blood.” Addition of an antipsychotic drug resulted in re- subclinical psychotic experiences at age 11–12 were asso-

mission of all symptoms. ciated with a family history of psychosis, but no particular

psychotic disorder diagnosis [28].

Changing diagnostic criteria make it difficult to inter- Such research suggests that psychosis is a trait that can

pret research over the years in psychotic depression. The occur in a variety of disorders including schizophrenia,

clinical and theoretical implications of a study depend on schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, MDD, and

whether psychosis is defined by delusions and/or halluci- possibly other conditions complicated by psychotic fea-

nations, or by severity, impairment, or melancholia, tures such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), cer-

whether MDEs were unipolar or bipolar, and whether the tain personality disorders, and delusional disorder. The

control group consisted of MDD of similar severity with- psychosis trait may be transmitted independently of oth-

out psychosis, psychosis without depression, or melan- er features such as dysregulation of mood or thought [30].

cholic versus nonmelancholic depression [8, 15]. Inter- Thus, association of a psychosis trait with dysregulated

Downloaded from http://karger.com/pps/article-pdf/90/3/160/3908896/000511348.pdf by guest on 02 December 2023

pretation of the results is further complicated by the ques- mood may produce a psychotic mood disorder pheno-

tion whether subjects had a past but not current history of type, while confluence of the capacity for psychosis and

psychosis, or whether they were currently psychotic [12]. disordered information processing may characterize

Differing definitions and assessment methods have schizophrenia. Accumulating evidence exists, particular-

contributed to varying estimates of the prevalence of psy- ly for bipolar mood disorders, that psychosis itself does

chotic depression. Prevalence has been reported to be not distinguish between categorical diagnoses; indeed,

4/1,000 adults in the general population and 14–30/1,000 the content of psychosis and the presence of thought dis-

of those over age 60 [4]. In community samples, 10–19% order by themselves do not distinguish between schizo-

of adults with a MDE have been reported to have psy- phrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder [31]. However,

chotic symptoms [12]. Studies in specialty settings sug- when psychosis is present, the primary disorder is more

gest that psychotic features are present in 6–25% of pa- severe and produces more impairment and a worse prog-

tients with MDD [4, 18–21]. Around 25–45% of all adult nosis [28, 29, 32].

inpatients with MDD, and 24–53% of geriatric patients An independently transmitted psychosis trait has been

hospitalized for depression, have been reported to have thought to be linked to a relatively small number of gene

psychotic features [4, 14, 18, 22]. Since psychotic symp- sequences on the X and Y chromosomes (protocadherin

toms are often overlooked in depressed patients, the true XY) coding for brain cell adhesion molecules that influ-

prevalence of psychotic depression is likely to be under- ence cerebral laterality and that played a role in the evolu-

estimated [4]. tion of human language [33]. In the case of mood disor-

ders, the threshold for expression of the psychosis trait

may be lowered by epigenetic changes associated with the

A Transdiagnostic Psychosis Trait primary mood disorder, resulting in the appearance of

psychosis once the mood disorder reaches a certain level

Although the association has been questioned [4], a of severity [34]. It may be that other reports of similar ge-

family history of diverse psychotic disorders including netic markers in psychotic unipolar and bipolar depres-

schizophrenia, psychotic bipolar disorder, and psychotic sion, schizophrenia, and schizoaffective disorders are the

major depression is more common in psychotic than result of markers of vulnerability to psychosis, not to any

nonpsychotic depression [23–25]. Furthermore, there is specific categorical diagnosis.

some evidence that the content of delusions and halluci-

nations may be similar in psychotic relatives of psychoti-

cally depressed patients, regardless of the actual psychot- Mood Congruent and Mood Incongruent Psychotic

ic disorder [26], suggesting a transdiagnostic psychosis Symptoms

phenotype that overlaps affective and nonaffective psy-

chotic syndromes [27, 28]. This phenotype may be more The diagnostic and prognostic importance of mood

strongly expressed in bipolar disorder, in which a family congruent (i.e., reflective of a depressed or manic mood)

history of schizophrenia occurs in 14% of patients, while and mood incongruent psychotic symptoms in mood

162 Psychother Psychosom 2021;90:160–177 Dubovsky/Ghosh/Serotte/Cranwell

DOI: 10.1159/000511348

disorders is the subject of ongoing discussion. Some in- 10.5% a diagnosis of bipolar II, mood disorders [12]. An

vestigators propose that mood incongruent psychotic eventual diagnosis of bipolar disorder is especially com-

features indicate a distinct subtype of psychotic depres- mon in early-onset psychotic depression [4, 43]. Relatives

sion with a worse prognosis regardless of the severity of of patients with psychotic depression have a higher rate

depression [35]. This point of view appeared to be sup- of bipolar disorder than relatives of patients with nonpsy-

ported by a finding that mood incongruent psychotic chotic depression, and depressed relatives of patients

features aggregated in families and predicted a more se- with bipolar disorder are more likely to have psychotic

vere course [36]. In the Research Diagnostic Criteria, features than are depressed relatives of controls [4]. As in

mood disorders with mood incongruent psychotic symp- unipolar depression, psychosis accompanying bipolar

toms are grouped under schizoaffective disorder, based disorder is associated with an earlier age at onset of the

on the concept that mood incongruence conveys a worse mood disorder, more affective symptomatology and

course of mood disorders [37]. On the other hand, there chronicity, a greater number of admissions, longer hos-

is considerable heterogeneity of outcome in these pa- pitalizations, more psychiatric comorbidity, and a poorer

tients [38]. prognosis [44].

Outcome studies of psychotic depression with mood One feature of bipolar psychotic depression that has

Downloaded from http://karger.com/pps/article-pdf/90/3/160/3908896/000511348.pdf by guest on 02 December 2023

incongruent symptoms are difficult to interpret because not received much attention in the literature is the degree

of lack of consistency of criteria for inclusion of subjects to which mixed elements of elevated mood and energy

in this category. For example, at what point is a delusion can result in patients not appearing to be as depressed as

considered to be mood incongruent? Are delusions of they feel, and for patients with psychotic symptoms to

persecution by the devil, the FBI, or spirits in different function at a higher level than would be predicted by the

categories? Even if there is a clear consensus on what con- degree of symptomatology. Such patients’ symptoms may

stitutes mood incongruence, do all psychotic symptoms be dismissed as exaggerated or indicative of a personality

have to be mood incongruent? How do investigators clas- disorder, making the clinician overlook the actual diag-

sify patients for whom 50% of psychotic symptoms are nosis. Another feature of bipolar psychotic depression

mood incongruent? What about 10% or one mood incon- that is easily overlooked is the frequent occurrence of

gruent symptom? Since the Research Diagnostic Criteria nonauditory hallucinations. Visual hallucinations have

for schizoaffective disorder are different from the DSM been noted to occur more frequently in bipolar than in

criteria, which are based on psychotic features in the pres- unipolar depression [45], but olfactory and haptic hallu-

ence of a normal mood, even with agreement about the cinations are not rare either. Dramatic, mood incongru-

definition of mood incongruence, all studies of this diag- ent hallucinations may be minimized by patients who are

nosis are not comparable. not necessarily disturbed by them, requiring persistence

Regardless of how psychosis is categorized, the bulk of to reveal the psychosis.

evidence suggests that there is no difference in outcome Case example: A 20-year-old student with a MDE did not ap-

between psychotic depression with mood congruent ver- pear depressed or withdrawn even though he endorsed multiple

sus mood incongruent symptoms [35, 39, 40]. One point depressive symptoms. He denied seeing things that other people

about which there is growing consensus is that mood in- did not see. However, when asked whether he ever saw some-

congruent psychotic symptoms convey greater likelihood thing moving out of the corner of his eye, he replied “like a bat?”

When asked next whether he ever saw a bat, he replied that he

of bipolar than unipolar depression [12, 25]. did not. In reply to the question “what else don’t you see,” he said

“I don’t see rats crawling all over my feet.” The next question was

“why not,” to which the patient replied, “because it would mean

Psychotic Depression and Bipolar Disorder the devil sent them.” How long had the devil been sending ani-

mals to torment him? For the past 4 years. This was about the

same time he developed a headache that felt like his head was

Psychotic depression is more likely than nonpsychotic swelling. Why had he not mentioned these experiences? He did

depression to have a bipolar outcome [1, 41], and epi- not want people to think that there was something wrong with

sodes of bipolar depression are more frequently associ- his mind. A more careful review of affective symptoms prompt-

ated with psychotic symptoms than are episodes of uni- ed by elicitation of these symptoms revealed that the patient only

polar depression [42]. Indeed, a strong predictor of psy- slept 2–3 h per night, that he had continually racing thoughts

previously diagnosed as obsessions, and that he had become in-

chosis in the course of a mood disorder is bipolarity [15]. creasingly irritable and impulsive with treatment with antide-

Of adults with psychotic depression in community sam- pressants.

ples, 48.5% have received a diagnosis of bipolar I, and

Psychotic Depression Psychother Psychosom 2021;90:160–177 163

DOI: 10.1159/000511348

Covert Psychotic Depression Table 1. Clinical clues to psychosis in depressed patients

Symptoms

Depressed patients may minimize or not report psy-

Severe early morning awakening

chotic symptoms because they do not think that they are Extreme agitation or retardation

abnormal, they do not want to be considered ill, or they Overvalued self-reproach, guilt, and somatic preoccupation

want to be left alone. Some patients may not recall psy- Marked perplexity and cognitive dysfunction

chotic symptoms they experience in one mental state Significant dissociation

(e.g., when they are manic) at a time they are in another Course

state (e.g., when they are depressed). As in the previous Early or postpartum onset of severe depression

example, some patients may not think abstractly enough Poor antidepressant response

to answer broad general questions such as whether they Family history/neurobiology

see things or hear things or whether they feel persecuted, Family history of psychosis

but they may be forthcoming if they are asked about spe- Previous episodes of psychotic depression

Sleep onset REM/hypnogogic hallucinations

cific hallucinations and delusions. Features often associ- High post-dexamethasone cortisol on dexamethasone

ated with psychotic depression that can serve as clues to

Downloaded from http://karger.com/pps/article-pdf/90/3/160/3908896/000511348.pdf by guest on 02 December 2023

suppression test

the presence of psychosis in patients who initially deny

Imaging findings

such symptoms are summarized in Table 1 [11–13, 15, 19, Small hippocampal volume

23, 24, 46–48]. Enlarged ventricles

Juvenile Psychotic Depression

In community samples, 9–35% of children and 5–11% erence, mind reading, and thought broadcasting [49].

of adolescents endorse hallucinations [49–51]. However, Children may not report delusional ideas out of fear of

psychotic-like experiences in younger patients are diffi- being punished for saying things that adults might think

cult to interpret because children normally have difficul- are not true [12]. Any psychotic symptoms in younger

ty distinguishing fantasy from reality, perhaps explaining depressed patients increase the likelihood of a bipolar

why 75–90% of such experiences are transient [12, 52]. outcome [12, 49].

On the other hand, a systematic review and meta-analysis Case example: A 14-year-old boy was being treated for a MDE

of 14 studies from 13 different community samples (n = and a tic disorder. The latter diagnosis was based on repetitive,

29,517) found that childhood psychotic experiences con- nearly identical, torticollis-like movements of his head. The move-

veyed a three- to fourfold increased risk of a mood or ments seemed to be directed toward a spot that was always to the

psychotic disorder [51]. A study of 20,000 patients aged patient’s left. Finally, the patient was asked what he kept looking

at. The patient replied, “that goblin sitting on the desk.” What was

15 years or older found that 18.5% of subjects who met the reason the patient had not mentioned the hallucination previ-

the criteria for a MDE had psychotic features [12]. Up to ously? He thought everyone saw it.

60% of children hospitalized for depression have been re-

ported to have psychotic symptoms [50]. Since many

younger patients do not tell their parents about psychotic

symptoms [49, 50], the prevalence of psychotic symp- Mild and Transient Psychotic Symptoms

toms in depressed children and adolescents is probably

underestimated. Research into the phenomenology and treatment of

Among patients with psychotic mood disorders, hal- psychotic depression has primarily involved patients with

lucinations are more common in children and adoles- easily identifiable, blatant psychotic symptoms. However,

cents than in adults [50]. Hallucinations occur in as psychosis is a continuous rather than dichotomous phe-

many as 80%, and delusions occur in 22%, of psychoti- notype across clinical diagnoses and subclinical psychot-

cally depressed youth [49]. Auditory hallucinations are ic-like experiences in the otherwise healthy general popu-

most common, but they are often accompanied by vi- lation [53]. Yet, little is known about whether the impact

sual, olfactory, and/or haptic hallucinations [12, 50], of subtle or intermittent psychotic symptoms on the

while delusions are less common [12]. The most com- course and treatment response of mood disorders is sim-

mon delusions in juvenile patients are delusions of ref- ilar to that of more obvious psychosis.

164 Psychother Psychosom 2021;90:160–177 Dubovsky/Ghosh/Serotte/Cranwell

DOI: 10.1159/000511348

Brief, “nondiagnostic” psychotic experiences occur in Psychotic Depression and Trauma

about 7–10% of the general population, 17% of children

aged 9–12 years, and 7.5% of teenagers [12, 28]. However, A history of childhood trauma is 2–15 times higher in

these symptoms are qualitatively different from clinically psychotic than in nonpsychotic depressed patients [20].

relevant psychosis [54]. For example, paranormal beliefs In a study of 500 psychiatric outpatients, patients with

and magical thinking without impairment are much psychotic depression were four times as likely to have co-

more likely to be experienced by people who are not ill morbid PTSD as were those without psychotic depression

than are paranoia, bizarre experiences, and hallucina- (57.9 vs. 15.7%; p = 0.0001) [58]. The observation that

tions, which are more likely to be associated with distress combat-related PTSD has a 30–40% incidence of psy-

and disability [55]. Subclinical psychotic experiences are chotic symptoms [59] raises the question whether such

transient in 80% of people, but 20% may develop persis- individuals have PTSD with comorbid psychotic depres-

tent psychotic experiences, and 7% end up with a psy- sion, whether PTSD with psychosis is a distinct PTSD

chotic disorder [28], with an annual transition rate to psy- subtype [60], or whether, in contrast to depression, psy-

chotic disorder of <1% [28]. Persistence of psychosis is chotic symptoms in PTSD have no particular diagnostic

more likely in people with past traumatic experiences or or therapeutic significance. Psychotic symptoms in PTSD

Downloaded from http://karger.com/pps/article-pdf/90/3/160/3908896/000511348.pdf by guest on 02 December 2023

a family history of any psychotic disorder [28]. Ultra- may or may not reflect the trauma; cases in which they do

high-risk individuals, who have multiple subclinical psy- not could be cases of PTSD with comorbid psychotic de-

chotic experiences, have higher annual transition rates to pression rather than psychotic PTSD [59]. Along these

psychosis [28], with a risk of developing a psychotic dis- lines, some clinicians question whether psychotic symp-

order within 1 year of 22% and a risk of 36% after 3 years toms that reflect traumatic experiences represent “real”

[55]. or “pseudo” psychosis. Hallucinations and delusions in

According to Carlson [12], “psychotic symptoms that this formulation represent flashbacks or dissociative re-

are detailed and dramatic or in which content is associ- experiencing of elements of trauma, although empirical

ated with past traumatic experiences, or only present evidence supporting this formulation is variable [61]. In

when the person is angry, or while negotiating for some 73 women being treated for PTSD related to childhood

particular need to be met, are unstable and do not rep- abuse and neglect, 46–91% endorsed hearing voices on

resent true psychosis. These symptoms, even when they one or both of two standardized instruments [62]. The

occur in the context of a depressive state, probably do authors considered such symptoms, which were more

not represent true affective psychosis” (p. 571). Beb- likely to be present on instruments that asked multiple

bington [56] agrees that “there is a (rational) reticence questions about them, to be dissociative experiences dis-

to diagnose a psychotic disorder if the psychotic symp- tinct from “true” psychotic symptoms. Interestingly,

toms are only experienced rarely, or occur singly, espe- there was no difference in the use of antipsychotic drugs

cially if the person is undisturbed by them and has in- between patients who did or did not hear voices. There is

sight” (p. 128). Within the clinical spectrum of halluci- mixed evidence to determine whether antipsychotic

nations and delusions in mood disorders, however (as medications are reliably useful in PTSD with psychosis

opposed to the clinically well general population), it is [60, 63], or whether psychotherapy alone resolves “psy-

not known whether milder symptoms have the same sig- chotic-like symptoms” in PTSD [64].

nificance as more severe ones. For example, do nondis- Since depression is a common feature of PTSD, psy-

tinct voices to which the patient pays no attention or that chotic depression in a patient with a history of trauma can

the patient thinks might be imaginary have the same di- be very difficult to differentiate from PTSD with psychot-

agnostic and prognostic significance as persistent accu- ic features [23]. Whether or not symptoms of comorbid

sations of sin from a supernatural source? Or does the PTSD are present, it is not known whether psychotic

intermittent feeling that people might be spying on the symptoms that directly reflect traumatic experiences in a

patient have the same impact on course or treatment re- depressed patient (“trauma congruent” psychotic symp-

sponse as the conviction that the patient is being perse- toms) have different therapeutic or prognostic implica-

cuted? At which point does intense rumination become tions than mood congruent psychotic symptoms. The

delusional [57]? The threshold of severity or persistence speculation that some of the relative treatment resistance

for altering the course of mood disorders is yet to be de- reported with psychotic depression may be due to unrec-

termined [46]. ognized PTSD [58] has not been studied. It is not yet clear

whether treatment of the combination of posttraumatic

Psychotic Depression Psychother Psychosom 2021;90:160–177 165

DOI: 10.1159/000511348

symptoms, depression, and psychosis should be similar toms [69]. Despite evidence that depressive and negative

to the treatment of psychotic depression in the absence of symptoms represent distinct domains in schizophrenia,

a significant trauma history. antidepressants may improve the latter [70–72], although

not all studies agree [73] and it is often not clear whether

Case example: Following the fall of Saigon, a man who had patients who responded were also depressed.

served as an officer in the South Vietnamese army was tortured by

the new government in a re-education camp. He escaped and left

The assessment of depressive symptoms in patients

Vietnam with a group of refugees who were further traumatized with schizophrenia can be complex. For one thing, it can

when they were captured by pirates in the South China Sea. After be difficult to distinguish between depressive and nega-

making his way to the United States, he supported himself and the tive symptoms. Bradykinesia and affective blunting

family he established by working at several jobs. Years after settling caused by antipsychotic drugs can also mimic depression,

in a suburban neighborhood, he was in a motor vehicle crash that

was startling but caused no injuries. The man had no initial reac-

and antipsychotics with more potent D2 blockade may be

tion, but a few weeks later he became agitated and hypervigilant, associated with dysphoria [74]. A recent review suggested

with an increasing sense of being in danger from unknown sourc- that sulpiride, amisulpride, clozapine, olanzapine, aripip-

es. Along with insomnia, bad dreams he could not remember, and razole, quetiapine, and lurasidone may be somewhat

restlessness, he developed crying spells, loss of appetite, difficulty more effective than other antipsychotics in ameliorating

Downloaded from http://karger.com/pps/article-pdf/90/3/160/3908896/000511348.pdf by guest on 02 December 2023

concentrating, anhedonia, and guilt, although he could not say ex-

actly what he felt guilty about. As he became more tearful and

depressive symptoms in schizophrenia [74]. In an 8-week

withdrawn, he began to hear the voices of fellow soldiers who had clinical trial, both amisulpride and olanzapine reduced

been killed during the war telling him that he did not deserve to depressive symptoms in schizophrenia patients, with 62–

live and should join them. The sense of being in danger evolved 66% of patients rating as “much” or “very much” im-

into the belief that he was going to be killed by an unseen enemy. proved on the Clinical Global Impression Scale [75].

Attempts to address the relationship of the current symptoms

to traumatic experiences during and after the war intensified all Conversely, the review cited above suggested “modest ef-

symptoms, as did a discussion of the losses he had suffered at that fectiveness” for depression accompanying schizophrenia

time. In view of the prominent depressive symptoms, he was treat- of adding an antidepressant [74]. In a study of 175 schizo-

ed with an antidepressant, with modest improvement. After an phrenia patients with comorbid MDD, antidepressants

extensive discussion about whether the psychotic symptoms were reduced depression scores and produced remission of de-

simply dissociative experiences that reflected activation of PTSD

by the shock of the crash, an antipsychotic medication was added. pression in 56%, without improving schizophrenia symp-

As the dose was increased, all symptoms remitted completely. At toms [66]. No antidepressant appeared more effective

that point, he was able to discuss his earlier experience and begin than any other, while nonresponse was predicted by more

active grieving of the losses of wartime comrades and his home- severe paranoia and comorbid substance use disorders. A

land. 12-week open-label study found the antidepressant

agomelatine to be effective for depressive and negative

symptoms and global psychopathology, but not positive

Depression Complicating Psychosis symptoms, in patients with schizophrenia and MDD, al-

though pharmacokinetic interactions with antipsychotic

Traditionally, the term psychotic depression refers to drugs sometimes occurred [76].

a primary mood disorder that is complicated by psycho-

sis. Much less information is available about primary

nonaffective psychoses complicated by depressive epi- Treatment

sodes. Within this group, the largest body of data con-

cerns schizophrenia. Estimates of the prevalence of de- Psychotic depression has a low rate of spontaneous re-

pressive episodes in schizophrenia have ranged from 27 covery [77]. In early studies, the placebo response rate

to 48% [65–67], while in one study 31% of patients aged was close to zero [78], but recent studies report a response

> 55 years with schizophrenia spectrum disorders had rate to placebo as high as 30% [79]. In contrast to less

subsyndromal depressive symptoms [67]. Comorbid de- complicated forms of depression, the response to psycho-

pression in schizophrenia is associated with more posi- therapy alone has been known for some time to be negli-

tive and negative symptoms and greater suicidality [67, gible [77, 78, 80], although cognitive approaches can im-

68]. Despite substantial overlap between depressive and prove coping in mood disorder patients with delusions

negative symptoms, low mood, pessimism, and suicidal- [81]. Other psychotherapies that have been used adjunc-

ity are more specific to depression, while alogia and tively include behavioral activation, acceptance and com-

blunted affect are more reliably linked to negative symp- mitment therapy, and acceptance-based depression and

166 Psychother Psychosom 2021;90:160–177 Dubovsky/Ghosh/Serotte/Cranwell

DOI: 10.1159/000511348

psychosis therapy (a combination of behavioral activa- Studies of newer antipsychotic drugs and antidepres-

tion and acceptance and commitment therapy) [4]. Nev- sants in psychotic depression have mainly involved a few

ertheless, somatic therapies remain a mainstay of treat- second-generation antipsychotics and SSRIs. An indus-

ment. try-sponsored, multicenter study consisted of two 8-week

The pharmacologic approach to psychotic depression double-blind trials (124 patients in one trial, 125 in the

depends on whether psychosis is conceived of as one end other; mean age 41 years) [87]. Patients the majority of

of a continuum of severity in depression or a distinct en- whom had mood congruent psychotic symptoms were

tity. If it is simply very severe major depression, an anti- randomly assigned to placebo, olanzapine, or the combi-

depressant alone at the right dose should be effective, pos- nation of olanzapine and fluoxetine. Modal doses were

sibly with one of the standard augmentation agents. If 11.9–14.5 mg of olanzapine and 22.6–23.5 mg of fluox-

psychotic depression is a distinct disorder, treatment etine. Only 42–47% of patients completed the trials. In

both for psychosis and depression would be necessary one trial, the combination of olanzapine and fluoxetine

[82]. To address this question, initial studies of pharma- was significantly more effective than placebo, with a de-

cotherapy for psychotic depression involved tricyclic an- crease in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS)

tidepressants (TCAs) and/or first-generation antipsy- scores from 38.4 to 20.9. There were no differences be-

Downloaded from http://karger.com/pps/article-pdf/90/3/160/3908896/000511348.pdf by guest on 02 December 2023

chotic drugs (neuroleptics). A review of randomized tween groups in the other trial. The Study of Pharmaco-

studies between 1966 and 2004 [18], only one of which therapy of Psychotic Depression (STOP-PD) was a four-

employed a placebo arm, reported response rates to ami- center, 12-week, double-blind comparison of remission

triptyline, perphenazine, or the combination of 41, 19, rates (defined as HDRS score ≤10, not meeting criteria

and 78%, respectively; in another study included in that for MDD, and absence of psychosis) in 259 psychotic de-

review [83], response rates were 86% with amitriptyline pression patients (mean age 58.8 years) randomly as-

plus perphenazine and 82% with amoxapine, a metabolite signed to olanzapine (average dose 14–15 mg) plus pla-

of the antipsychotic drug loxapine that has both antide- cebo, or olanzapine plus sertraline (average dose 169–170

pressant and antipsychotic properties [18]. An updated mg) [79, 88–90]. Patients had to have at least one moder-

systematic review of 12 RCTs in 11 publications involving ately severe delusion. None of the patients had hallucina-

a total of 929 patients confirmed that the combination of tions in the absence of delusions. Following randomiza-

an antidepressant and an antipsychotic drug (combina- tion, 63% of combination therapy patients and 47% of

tion therapy) was more effective in reducing depressive monotherapy patients completed the double-blind study

symptoms in psychotic depression than either one alone [88]. Remission rates were 42% for combination therapy

or placebo [82]. The finding was limited by considerable versus 24% with olanzapine monotherapy (p = 0.002;

variability between studies as well as patient heterogene- NNT = 5.5); statistical separation began at week 8 [88, 91].

ity and potential for bias. A meta-analysis of 8 acute- At the end of the study, 45% of patients still had psychot-

phase RCTs in 762 adults with psychotic depression per- ic symptoms, with no significant differences between

formed through February 2011 found that combination groups [89]. Based on rating scale scores, the superiority

therapy was significantly superior to antidepressant of combination therapy to olanzapine plus placebo was

monotherapy for ratings of efficacy and severity of illness, attributable to a better antidepressant effect and not a bet-

but not psychosis or anxiety ratings [84]. A finding of no ter antipsychotic effect [41].

superiority over 2 weeks of addition of perphenazine to In a 7-week RCT of 122 psychotically depressed pa-

nortriptyline (mean dose 19 mg; n = 17) versus placebo tients, significantly more patients responded to 375 mg of

in psychotically depressed patients who did not respond venlafaxine plus 600 mg of quetiapine (65.9%) than to

to 2 weeks of nortriptyline monotherapy [85] may have venlafaxine alone (33.3%) [21, 92]. The 59 (48.4%) pa-

been the result of too short a trial of too low a dose of the tients who responded (≥50% decrease in HDRS score and

antipsychotic. A comparison of the monoamine oxidase final score ≤14) were followed openly for another 15

inhibitor (MAOI) phenelzine in doses up to 90 mg/day weeks, during which time 6 patients dropped out [21]. At

and adequate platelet monoamine oxidase inhibition in week 22, 92.5% of patients were still taking study medica-

nonpsychotic and psychotic major depression found a tion, and 96.2% (51/53) of patients who completed main-

68% response rate in the former but only 21% in the lat- tenance therapy remained responders [21]. Remission

ter, suggesting that MAOI monotherapy is not more ef- rates (HDRS score ≤7) increased during maintenance

fective than TCA monotherapy in psychotic depression from 35/59 responders at week 7 of treatment to 46/53 at

[86]. week 22, without any differences between treatment

Psychotic Depression Psychother Psychosom 2021;90:160–177 167

DOI: 10.1159/000511348

groups [21]. At all points, improvement of depression [4]. In a meta-analysis of 44 studies of the treatment of

tended to parallel improvement of psychosis [21]. psychotic depression between 1959 and 1988 that includ-

A review of four psychotic depression RCTs that were ed studies of ECT, TCAs, MAOIs, antipsychotic drugs,

not summarized previously included comparisons of and combinations of these treatments, including three

venlafaxine versus venlafaxine plus quetiapine, olanza studies using simulated ECT as a control [95], ECT (es-

pine versus olanzapine plus sertraline, and trimipramine pecially bilateral ECT) produced a higher response rate

versus amitriptyline plus perphenazine [4]. Overall, com- than TCA-antipsychotic drug combinations. It has been

bination therapy was superior to monotherapy with an suggested that ECT is more effective for psychotic than

antidepressant or an antipsychotic drug [4]. A meta-anal- nonpsychotic depression [4], although this contention is

ysis of eight studies involving 784 patients confirmed not clearly supported by controlled studies. Since ECT

that combination therapy was superior to antipsychotic may reduce hospitalization time if initiated early and pro-

(NNT = 5) and antidepressant (NNT = 7) monotherapy long it if initiated later, ECT should be a first-line treat-

[84]. Conversely, addition of perphenazine (mean dose ment for suicidal or incapacitated psychotically depressed

19 mg) to therapeutic doses of nortriptyline in nortripty- patients [4].

line nonresponders did not improve the response rate [4]. Guidelines from the UK, Denmark, and the Nether-

Downloaded from http://karger.com/pps/article-pdf/90/3/160/3908896/000511348.pdf by guest on 02 December 2023

Since nortriptyline levels were not reported, it was not lands recommend antidepressant monotherapy as first-

clear whether the neuroleptic might have raised the nor- line treatment, apparently based on the 2005 Cochrane

triptyline level out of the therapeutic range. report mentioned earlier that did not find combination

In view of the possibility that it may take 8 weeks [88, therapy to be superior to antidepressant monotherapy

91] or longer [21] to demonstrate a clear response to [96]. However, since a subsequent review and meta-anal-

pharmacotherapy of psychotic depression, combination ysis of RCTs found that combination therapy was signifi-

therapy may not seem superior to monotherapy if the du- cantly more effective than antipsychotic or antidepres-

ration of treatment was inadequate. Another reason for sant monotherapy [84], and since most research and a

variable results with combination therapy may concern later Cochrane report favor combination therapy or ECT

antipsychotic drug doses. Most studies have used low to for unipolar psychotic depression [4, 82, 88, 90], the

moderate fixed antipsychotic doses. However, in older American Psychiatric Association (APA), Canadian Psy-

studies, doses up to 650–1,000 mg of chlorpromazine or chiatric Association, South African Psychiatric Associa-

24–64 mg of perphenazine were necessary to obtain a re- tion, Australia/New Zealand and international guide-

sponse [26]. A small study comparing responses of psy- lines, and the Texas Medication Algorithm Project

chotic major depression to the combination of the TCA (TMAP) all endorse combination therapy as first-line

desipramine and neuroleptics in several doses found that treatment [18]. These guidelines do not endorse specific

all 6 patients treated with at least 45 mg of perphenazine, medication regimens in view of inadequate data to sup-

but only 10 of 25 patients taking 32 mg or less, responded; port one medication over another [4]. No guideline rec-

the greater response rate with the higher antipsychotic ommends antipsychotic monotherapy. The APA, Cana-

dose was not explained by changes in the TCA level [93]. dian, TMAP, Denmark, and international guidelines also

On the other hand, patients with mood disorders may be recommend ECT as first-line treatment, while the UK,

more vulnerable to tardive dyskinesia [94] and other ad- Australia/New Zealand, and international guidelines en-

verse effects that lead to treatment discontinuation [18]. dorse ECT as the first-line treatment in the presence of

The suggestion that some patients may need higher anti- severe suicidality or a “threatening somatic condition” [4,

psychotic doses, which may have actions beyond dopa- 18]. Overall, there is a significant lack of consensus on the

mine D2 receptor blockade [46], has not been pursued in treatment of psychotic depression, both in treatment

newer studies or in any studies of atypical antipsychotic guidelines and among practicing psychiatrists, especially

drugs. in terms of specific agents and doses [4, 47]. Regardless of

Most studies find the overall response rate to electro- the standard that is adopted, however, only 5% of psy-

convulsive therapy (ECT) of psychotic depression of 82– chotically depressed patients receive adequate treatment

90% to be equivalent or superior to combination therapy [4].

[4, 79]. However, the response rate to ECT in community Although manualized psychotherapies such as cogni-

samples is reported to be lower (30–47%), possibly be- tive behavior therapy and interpersonal therapy are effec-

cause more patients with comorbid medical conditions tive for many cases of MDD, the presence even of mild

and other complications are included in these samples psychotic symptoms reduces the response to psychother-

168 Psychother Psychosom 2021;90:160–177 Dubovsky/Ghosh/Serotte/Cranwell

DOI: 10.1159/000511348

apy [97]. A number of individual and group psychologi- intention-to-treat and completer analyses, mifepristone

cal interventions have been found to improve symptoms patients had higher rates of 50% decrease of Brief Psy-

and functioning in psychosis, particularly schizophrenia chiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) positive symptoms. The ef-

[98–101]. However, the applications of these therapies in fect of mifepristone was most marked for psychotic

psychotic depression have not been studied. Similarly, symptoms; there was no significant decrease in depres-

psychotherapies for prodromal or attenuated psychosis sion. A secondary analysis of a similar study that did not

that have been found to be promising have not been stud- note an overall significant effect on BPRS score 7 weeks

ied in depression associated with mild psychotic symp- after a 1-week trial of treatment with mifepristone found

toms. that the results were four times more likely to be signif-

Psychotherapy is generally considered the most ap- icant in patients with higher mifepristone plasma levels

propriate initial treatment of childhood depression [102], (≥1,800 mg/mL) [107].

although a Cochrane review concluded that the relative

benefits of pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, or the com-

bination thereof have not been clearly demonstrated em- Course

pirically [103]. Psychological interventions for psychosis

Downloaded from http://karger.com/pps/article-pdf/90/3/160/3908896/000511348.pdf by guest on 02 December 2023

in adolescence appear to be helpful for cognition and Relapse or recurrence has been reported within 2–14

functioning, if not psychosis itself [104]. However, there months after recovery from an index episode of psychot-

is very little empirical information about psychotherapy ic depression [21, 46]. A 2-year prospective follow-up of

in juvenile psychotic depression. 56 patients (mean age 36 years) with a first episode of

DSM-IV MDD with psychotic features found that 35%

Augmentation had achieved true functional recovery [108]. Relapse or

Augmentation with lithium in four small, uncon- recurrence within 2 years of initial recovery occurred in

trolled studies improved the response rate of psychotic 45% of 49 patients in this study; the mean time to a new

depression, especially bipolar psychotic depression, to episode was 57 weeks. The high rate of relapse may have

combination therapy [4]. In one report, open augmenta- been related to lack of adequate maintenance treatment:

tion of antidepressant-antipsychotic combination ther- at 2 years, 51% (25 of 49 subjects) were not taking any

apy with carbamazepine was effective in 3 patients [105]. medication, and most patients were not taking combina-

There has been more systematic interest in brief aug- tion therapy. Similarly, a 10-year follow-up found that

mentation with mifepristone, an antagonist of the pro- psychotically depressed patients were three times less

gesterone receptor and the glucocorticoid receptor type likely than non-psychotically depressed patients to have

II, which has a low affinity for cortisol and helps termi- recovered from the index episode [109]. Depressive re-

nate the stress response [19]. Since high levels of cortisol currences were ten times as likely to have psychotic fea-

reported in psychotic depression could disinhibit dopa- tures following a psychotic compared to a nonpsychotic

mine release and contribute to psychosis, it has been hy- episode [109]. Conversely, a long-term prospective study

pothesized that adjunctive use of mifepristone might re- found that after 40 years of follow-up, outcomes were

duce psychotic symptoms in psychotic depression. An similar in psychotically and non-psychotically depressed

open-label trial of 6 days of mifepristone monotherapy patients [110, 111].

in 20 inpatients with a DSM-IV MDE with psychotic The question remains whether continuation of both

features followed patients openly for a total of 8 weeks the antidepressant and the antipsychotic drug is neces-

[106]. Psychotic symptoms improved significantly over sary to prevent relapse of psychotic depression. Earlier

the first 4 weeks, but not subsequently. In a double- experience with combination therapy with neuroleptics

blind, placebo-controlled study, 221 patients with psy- suggests that discontinuing or even reducing the dose of

chotic depression (mean age 41–42 years) were random- the antipsychotic drug within the first year of recovery

ized to 7 days of monotherapy with mifepristone or pla- increases the risk of relapse, even if the antidepressant is

cebo [19]. Mifepristone was then discontinued and continued [4, 18, 22, 112–114]. A RCT of 26 weeks of

patients were treated openly for another 3 weeks with maintenance treatment in psychotic depression found no

whatever treatment the clinician preferred. During this difference between monotherapy with nortriptyline or

phase, 58–62% were treated with an antidepressant, 36– sertraline versus one of these antidepressants plus per-

42% with an antipsychotic drug, 29–37% with combina- phenazine, but the sample size was very small and the re-

tion therapy, and 2–3% with ECT. At 28 days in both sults were probably not generalizable [4].

Psychotic Depression Psychother Psychosom 2021;90:160–177 169

DOI: 10.1159/000511348

To address the lack of empirical data about mainte- told him that she thought that her psychiatrist was conspiring with

nance therapy, a second STOP-PD openly treated 269 pa- her boss to discredit a project she had been working on. After some

discussion, she revealed that a number of people had been plotting

tients (mean age 55–56 years) with a MDE and at least one to steal her ideas because they knew that she had been having trou-

delusion with or without hallucinations to median daily ble concentrating. Risperidone was added, and at a dose of 4 mg/

doses of 150 mg of sertraline and 15 mg of olanzapine day the patient was improved but not well. When the dose was

[115]. Of the 195 patients who completed 12 weeks of gradually increased to 8 mg/day, she had complete remission of

acute treatment, 162 met the criteria for at least 2 weeks symptoms and returned to full-time work. Attempts to reduce the

dose of the antipsychotic drug by 0.5–1 mg at a time were repeat-

of remission (no psychotic symptoms and 17-item HDRS edly followed by relapse, which remitted when the previous dose

score ≤10) or near-remission (no psychotic symptoms was reinstituted. The patient remained well psychiatrically for 3

and 50% reduction in HDRS score with a final score of more years when she developed orofacial dyskinesia. Asserting

11–15; improved or very much improved on the Clinical that she could not live with a return of depression, she refused an-

Global Impression Scale). After an 8-week stabilization other attempt to withdraw the antipsychotic drug. She was unwill-

ing to consider ECT. A vesicular monoamine transporter-2 inhib-

phase with combination therapy, 126 patients who still itor was not helpful. Gradual crossover to clozapine in an eventual

met the criteria for remission or near-remission were ran- dose of 700 mg maintained remission of psychotic depression and

domized to a 36-week trial of open-label sertraline plus

Downloaded from http://karger.com/pps/article-pdf/90/3/160/3908896/000511348.pdf by guest on 02 December 2023

minimized dyskinetic movements, making it easier for the patient

double-blind olanzapine or placebo. During this phase, to interact with colleagues. She continued to function well at work.

relapse occurred in 20% of patients receiving combina-

tion therapy versus 55% of patients receiving sertraline

plus placebo (HR 0.25; p < 0.001; NNT = 2.8). Addition Real-Life Treatment Recommendations

of olanzapine resulted in significantly more weight gain

and waist circumference and less of a decrease in total As is true in nonpsychotic depression, clinical trials in

cholesterol as well as significantly more Parkinsonism but psychotic depression usually exclude patients who are

not akathisia. In this study, relapse on placebo was associ- suicidal or homicidal, and those with significant comor-

ated with cortical thinning on MRI, but continuation of bidity, especially of substance use and personality disor-

the antipsychotic drug was also associated with cortical ders. As noted earlier, recent studies of combination ther-

thinning, suggesting that both the illness and its treat- apy have involved a small number of atypical antipsy-

ment have neurological risks [116]. Most of the excess chotics and antidepressants in patients with primarily

risk of relapse with antidepressant monotherapy was dur- mood congruent psychotic symptoms. While doses of an-

ing the first 2 months of double-blind treatment or 4 tidepressants are relatively well established, most clinical

months after initial remission. However, since relapses trials of antipsychotic drugs have been in primary psy-

continued throughout the trial, the duration of antipsy- chotic disorders such as schizophrenia or in mania. In

chotic continuation that would prevent all relapses was psychotic depression, there is only one dose finding study

not clear [117]. An editorial suggested that the results in- of first-generation antipsychotics and none of atypical

dicate that the antipsychotic drug should be continued antipsychotics. The current body of data therefore may

for 4 months after remission, and possibly for a year or not inform choices sufficiently for the clinician who treats

longer, after which the antipsychotic drug might be grad- subtle, complex, or refractory psychotic depression, bipo-

ually discontinued, with reinstitution of the effective dose lar psychotic depression, and psychotic depression with

in response to any evidence of relapse [117]. It remains significant comorbidities. The following recommenda-

unclear whether the antipsychotic dose could be reduced tions are based on the data reviewed above and our own

without increasing relapse risk. The considerable hazards experience over many years of treating patients with psy-

and benefits of continuing the antipsychotic drug remain chotic depression (Fig. 1).

to be clearly defined, as do optimal specific medications Diagnosis is usually straightforward in patients who

and doses [4, 117, 118]. There have been no antidepres- describe depression and obvious psychosis. The first di-

sant discontinuation studies in psychotic depression. agnostic question is whether depression or psychosis is

primary. In the case of a primary psychotic disorder, es-

Case example: A successful architect had an episode of major pecially schizophrenia, complicated by a MDE, the cur-

depression at age 40 that responded well to an SSRI. She discon- rently available evidence suggests first reducing the dose

tinued the medication after a year and remained well for 15 years,

when she experienced a recurrence. She was treated with the same of the antipsychotic drug or changing to one of the anti-

antidepressant, which was not effective. When she failed to re- psychotics that have been thought possibly to be more

spond to a second antidepressant, her husband revealed that she helpful for depression or at least less likely to cause or ag-

170 Psychother Psychosom 2021;90:160–177 Dubovsky/Ghosh/Serotte/Cranwell

DOI: 10.1159/000511348

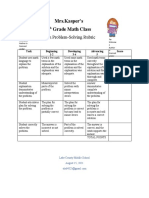

Depression with psychosis

Primary Primary

psychosis depression

Change

antipsychotic Bipolar Unipolar

Add Mild or transient Severe

Mood stabilizer

antidepressant psychosis psychosis

Mood stabilizer Antidepressant Antidepressant

combination + antipsychotic

Downloaded from http://karger.com/pps/article-pdf/90/3/160/3908896/000511348.pdf by guest on 02 December 2023

Antipsychotic No or incomplete Inadequate

response response

Persistent Add Augmentation

depression antipsychotic

Add

antidepressant

Fig. 1. Treatment decision-making in psy-

ECT

chotic depression (see text). ECT, electro-

convulsive therapy.

gravate dysphoria. The next step would be to add an an- The differentiation is obvious in patients with a past his-

tidepressant, with the expectation that depression and tory of mania or hypomania. However, especially in

possibly negative symptoms will improve, but the overall younger patients, this pole of the mood disorder may not

course of schizophrenia may not change. yet have occurred or may not be obvious. The possibility

Since not all patients with primary mood disorders of an underlying bipolar disorder should be considered in

volunteer psychotic symptoms, it is prudent to inquire psychotically depressed patients with subtle hypomanic

about them in patients who deny psychosis but fail to re- features such as intense irritability, aggression, or impa-

spond as expected to an antidepressant, especially when tience, lack of sleep without feeling tired, increased sexu-

factors summarized in Table 1 that are often associated al interest, lack of anhedonia, and increased physical or

with psychosis are present. Patients who are embarrassed mental activity despite complaints of severe fatigue. A bi-

about psychotic symptoms, consider them insignificant, polar component may also be suggested by early onset,

or fear that acknowledging them will result in hospitaliza- highly recurrent depression with an acute onset, dramat-

tion or some other perceived sanction may require indi- ic psychosis that is not associated with impaired function-

rect questions with more specific follow-up. For example, ing, nonauditory hallucinations, hallucinations without

patients who deny seeing things that other people do not delusions, bipolar first-degree relatives, or any mood dis-

see may acknowledge that they sometimes see movement order in multiple generations [43, 119–123].

out of the corner of their eyes and with further question- Although data on the treatment of bipolar psychotic

ing admit that it looks like a shadow or a person who depression are sparse, experience in nonpsychotic bipolar

seems to be following them. depression suggests that antidepressants can be problem-

When psychotic depression is identified, the first ques- atic [124–126]. Atypical antipsychotic drugs have theo-

tion is whether the mood disorder is unipolar or bipolar. retical appeal because some of them appear in short-term

Psychotic Depression Psychother Psychosom 2021;90:160–177 171

DOI: 10.1159/000511348

monotherapy trials to improve bipolar depression [127– incomplete response. In the absence of clinical trials in

130]. However, it is not entirely clear that reduction in unipolar depression with mild or intermittent psychotic

depression rating scale scores in these studies is not sec- features, our practice has been to initiate treatment with

ondary to improvement of insomnia, anxiety, irritability, an antidepressant. If this does not produce a robust re-

and related symptoms. In addition, the evidence that sponse, an antipsychotic drug is added. When the re-

these medications are true mood stabilizers is not com- sponse to standard pharmacotherapy is incomplete and

pelling [131], and metabolic, cognitive, and motor ad- ECT is not an immediate option, we augment combina-

verse effects can be troublesome, especially with long- tion therapy that has been used in other forms of refrac-

term treatment. Consistent with observations in mania tory depression such as lithium. As it is not possible to

[132], we have found that psychosis may remit without an adjust individual doses separately, we avoid fixed antide-

antipsychotic drug when mood improves. We therefore pressant-antipsychotic combinations such as perphen-

begin treatment with a mood stabilizer alone. Of the es- azine-amitriptyline (Triavil) and olanzapine-fluoxetine

tablished mood stabilizers, lithium and carbamazepine (Symbyax).

may be more acutely effective for depression, although Despite claims that atypical antipsychotics have anti-

valproate is an appropriate first choice for male patients depressant properties, there is no evidence that mono-

Downloaded from http://karger.com/pps/article-pdf/90/3/160/3908896/000511348.pdf by guest on 02 December 2023

with prominent anxiety or irritability [133]. Simplicity of therapy with an atypical antipsychotic drug is more effec-

administration and clear correlation between blood level tive for psychotic unipolar depression than monotherapy

and clinical response lead us to choose lithium first, ev- with an older antipsychotic. One exception is that the

erything else being equal. If mixed hypomanic symptoms neuroleptic loxapine, which is metabolized to the antide-

such as racing thoughts and insomnia improve but do not pressant amoxapine, was noted a number of years ago to

remit completely, we consider combinations of mood sta- be almost as effective as combination therapy [135, 136].

bilizers such as lithium and carbamazepine, which has Similarly, amoxapine has sufficient antipsychotic poten-

been found to have acute antidepressant properties in cy to have been used as monotherapy for psychotic uni-

some cases of bipolar depression [134]. We add an atypi- polar depression [83, 137]. Both of these medications are

cal antipsychotic drug if symptoms do not remit with one used only rarely today, but they are options for patients

or a combination of mood stabilizers or if mood improves who do not tolerate or respond to standard combination

but psychosis persists. We generally avoid antidepres- therapy.

sants unless patients cycle into depression in the absence As was noted earlier, limited published long-term

of any mixed dysphoric hypomanic symptoms such as studies suggest that antipsychotic drugs should probably

anxiety, insomnia, irritability, or racing thoughts. We be continued for 4–12 months after remission of unipolar

gradually withdraw the antidepressant once depression psychotic depression. Unless limiting adverse effects

remits and continue the mood-stabilizing regimen. emerge, we prefer to continue the antipsychotic for a year

In the presence of pervasive or severe psychotic symp- after remission of all symptoms. If the patient remains

toms in unipolar depression, the likelihood of response to well, we begin to reduce the dose gradually. If either de-

an antidepressant alone is low enough for initial treat- pressive or psychotic symptoms begin to re-emerge, we

ment with the combination of an antidepressant and an re-institute the previous dose. Consistent with the treat-

antipsychotic drug to be warranted. The most frequently ment of recurrent unipolar nonpsychotic depression or a

studied newer antidepressants have been sertraline, fluox- single severe or dangerous episode, the antidepressant is

etine, and venlafaxine, while older studies included ami- continued indefinitely.

triptyline and nortriptyline. While there is no reason to The substantial morbidity and suicidality associated

suppose that any of these antidepressants, or any other with psychotic depression leads us to offer ECT as an ini-

antidepressant, is superior to any other, early experience tial treatment to all patients with psychotic depression as

suggests that if an SSRI was not effective, a TCA might be a means of producing a more rapid response with fewer

considered [77]. There is also no reason why one antipsy- adverse effects. We continue to offer ECT to patients who

chotic drug would be more effective than another, al- do not tolerate or respond to combination therapy. Most

though most published trials have studied olanzapine or of the time, we follow a successful course of ECT with

perphenazine. We begin with low doses of the antipsy- maintenance ECT.

chotic drug, but bearing in mind studies suggesting the Despite the lack of controlled psychotherapy trials in

need for a high antipsychotic dose in some cases, we con- psychotic depression, we consider psychotherapy to be an

tinue to increase the dose as tolerated in the event of an essential component of any severe mood disorder. Ini-

172 Psychother Psychosom 2021;90:160–177 Dubovsky/Ghosh/Serotte/Cranwell

DOI: 10.1159/000511348

tially, we focus on barriers to adherence to medications cludes a number of patients with psychotic depression. In

or consideration of ECT. We find it helpful to involve addition, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation

significant others, both to address their own concerns may have some applications in the treatment of auditory

about treatment and to enlist their help in providing real- hallucinations. Controlled studies of these treatments in

ity testing and encouraging adherence. When patients are psychotic depression would certainly be justified, espe-

less distracted by psychotic experiences, we find it more cially for patients with psychotic depression who do not

productive to introduce cognitive techniques, mentaliza- respond to ECT or who cannot tolerate other treatments.

tion, and expressive approaches. Following remission, we Another source of uncertainty involves the diagnostic

have found it essential to encourage patient and family to and therapeutic significance of mild or transient psychot-

continue follow-up in order to detect and treat early ic symptoms in mood disorders. Do such symptoms, or

symptoms of relapse. psychotic symptoms that reflect traumatic experiences

As with any depressive episode, the goal of treatment such as hearing the voice of an abuse perpetrator or be-

of psychotic depression should be complete remission of lieving that one is under surveillance by a past attacker

both depression and psychosis to improve functioning who has died, qualify as bona fide psychotic symptoms

and quality of life and to reduce the risk of major relapse that indicate the need for adjunctive treatment with an

Downloaded from http://karger.com/pps/article-pdf/90/3/160/3908896/000511348.pdf by guest on 02 December 2023

or recurrence. This judgment can be a challenge when antipsychotic drug, or are they in some other category

patients have been severely ill for some time, since pa- that does not modify treatment of the mood disorder?

tients and clinicians may be satisfied with a return to One of the most interesting neurobiological uncer-

functioning or relief of intolerable distress without elimi- tainties is the manner in which a liability to psychosis in-

nation of all symptoms. Continued adjustment of the reg- dicated in part by a family history of any psychotic illness

imen requires considerable persistence on the parts of cli- interacts with a mood disorder to produce a unique syn-

nicians and patients. drome that is greater than the sum of its parts. Further

research that clarifies these issues will undoubtedly lead

to more precise treatment of the spectrum of psychotic

Future Directions mood disorders.

The acute treatment of definite psychotic unipolar de-

pression seems to be fairly well delineated. However, even Conflict of Interest Statement

after extensive experience over many years, a number of

important issues remain to be elucidated. Some patients S.L. Dubovsky has received research funding as site principal

may require high doses of first-generation antipsychotic investigator in multicenter clinical trials from Biogen, Allergan,

medications for a complete response, but it is not known Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen, and Boehringer Ingelheim. B.M.

Ghosh has received research funding as site principal investigator

whether the same is true of atypical antipsychotics, which in a multicenter study of vagus nerve stimulation from Medtronic.

are used more frequently for psychotic depression. It None of the products involved in any of these studies is mentioned

would be desirable to withdraw antipsychotic drugs as in this article, and funding sources played not role in any aspect of

soon as possible, or at least within a year, but there are preparation of the manuscript. J.C. Serotte and V. Cranwell have

insufficient long-term data to determine whether ongo- no conflicts of interest to declare.

ing antipsychotic treatment at the same or a lower dose is

necessary to prevent recurrence, as is the case for antide-

pressants in nonpsychotic depression. Antipsychotic Funding Sources

drugs combined with mood-stabilizing drugs are often

integral to the treatment of mania, but it is not yet known The authors have no funding sources to declare.

whether the combination of an antipsychotic drug and a

mood stabilizer is more effective than monotherapy with

a mood stabilizer as acute or maintenance treatment of Author Contributions

psychotic bipolar depression.

Instrumental therapies such as deep brain stimulation, S.L. Dubovsky developed the concept and wrote the first draft.

B.M. Ghosh provided additional input and edited the manuscript.

vagus nerve stimulation, and repetitive transcranial mag- J.C. Serotte and V. Cranwell performed research related to the

netic stimulation have increasingly been studied as inter- manuscript, reviewed and contributed to editing the manuscript,

ventions for refractory depression, a category that in- and provided additional references.

Psychotic Depression Psychother Psychosom 2021;90:160–177 173

DOI: 10.1159/000511348

References

1 Guze SB, Woodruff RA Jr, Clayton PJ. The 17 Owoeye O, Kingston T, Scully PJ, Baldwin P, 30 Crow TJ. The continuum of psychosis and its

significance of psychotic affective disorders. Browne D, Kinsella A, et al. Epidemiological genetic origins. The sixty-fifth Maudsley lec-

Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975 Sep; 32(9): 1147– and clinical characterization following a ture. Br J Psychiatry. 1990 Jun;156(6):788–97.

50. first psychotic episode in major depressive 31 Pope HG Jr, Lipinski JF Jr. Diagnosis in

2 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnos- disorder: comparisons with schizophrenia schizophrenia and manic-depressive illness: a

tic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disor- and bipolar I disorder in the Cavan- reassessment of the specificity of “schizo-

ders, Second Edition. 2nd ed. Washington, Monaghan First Episode Psychosis Study phrenic” symptoms in the light of current re-

D.C.: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1968. (CAMFEPS). Schizophr Bull. 2013 Jul;39(4): search. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978 Jul; 35(7):

3 Meyers BS. Psychotic depression. Psychiatr 756–65. 811–28.

Ann. 2006 Jan;36(1):7–9. 18 Andreescu C, Mulsant BH, Rothschild AJ, 32 van Os J, Linscott RJ, Myin-Germeys I, Deles-

4 Rothschild AJ. Challenges in the treatment of Flint AJ, Meyers BS, Whyte EM. Pharmaco- paul P, Krabbendam L. A systematic review

major depressive disorder with psychotic fea- therapy of major depression with psychotic and meta-analysis of the psychosis continu-

tures. Schizophr Bull. 2013 Jul;39(4):787–96. features: what is the evidence? Psychiatr Ann. um: evidence for a psychosis proneness-per-

5 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnos- 2006 Jan;36(1):31–8. sistence-impairment model of psychotic dis-

tic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disor- 19 DeBattista C, Belanoff J, Glass S, Khan A, order. Psychol Med. 2009 Feb;39(2):179–95.

ders, Third Edition. 3 ed. Washington, D.C.: Horne RL, Blasey C, et al. Mifepristone versus 33 Crow TJ. Handedness, language lateralisation

American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1980. placebo in the treatment of psychosis in pa- and anatomical asymmetry: relevance of pro-

Downloaded from http://karger.com/pps/article-pdf/90/3/160/3908896/000511348.pdf by guest on 02 December 2023

6 World Health Organization. International tients with psychotic major depression. Biol tocadherin XY to hominid speciation and the