Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Atkinson MACEDONATHENIANPOLITICS 1981

Atkinson MACEDONATHENIANPOLITICS 1981

Uploaded by

Zainab Hammood Kzar - زينب حمود كزارOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Atkinson MACEDONATHENIANPOLITICS 1981

Atkinson MACEDONATHENIANPOLITICS 1981

Uploaded by

Zainab Hammood Kzar - زينب حمود كزارCopyright:

Available Formats

MACEDON AND ATHENIAN POLITICS IN THE PERIOD 338 TO 323 BC

Author(s): J.E. Atkinson

Source: Acta Classica , 1981, Vol. 24 (1981), pp. 37-48

Published by: Classical Association of South Africa

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24591655

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Classical Association of South Africa is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to Acta Classica

This content downloaded from

82.199.213.103 on Sat, 02 Dec 2023 19:36:46 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MACEDON AND ATHENIAN POLITICS IN THE PERIOD

338 TO 323 BC1

by J.E. Atkinson

(University of Cape Town)

The defeat of the allied Greek forces at Chaeronea in August 338 BC was for

Athens a major disaster—1000 dead and a further 2 000 taken prisoner by

Philip (D.S. 16, 86,5)—and whilst the fearless talked of fighting to the end,

the war was over.1' This calamity administered a short sharp shock to the body

politic: extraordinary measures were proposed for the defence of the city and

there was a popular movement to appoint the mercenary commander Charidemus

to act as general through the crisis. However 'the best people' were alarmed at

this proposal and appealed to the Areopagus to intervene—not to protect the

traditional democratic forms, but to get this special commission given to

Phocion, and not Charidemus. The Assembly was prevailed upon to prefer

Phocion. Significantly Plutarch describes the men who clamoured for the

appointment of Charidemus as rowdies and revolutionaries.3 As these and

similar terms occur in complaints voiced by Aeschines, Demosthenes and

Hypereides about disorder in Athens, we may be sure that Plutarch is reflecting

the view of Phocion's contemporaries and sympathisers; and if we take this

episode as historical, it appears that we have here evidence of a division in

Athenian politics along the lines of class.4

The issue was not now between democrats and oligarchs as it had been in the

last decade of the Peloponnesian War, since the oligarchies of 411 and 404 made

oligarchy an unthinkable political option in the fourth century.5 However,

though any Athenian who wished to be taken seriously in the political arena was

obliged to profess his commitment to democracy, the democratic constitution

was vulnerable since it could be presented as too cumbersome for crisis

management and a liability in defeat. Hence the political crisis of 338, Eucrates'

law of 336 for the defence of the democracy, and Athens' acceptance of oligarchy

in 322. But discussion of the politics of this period has tended to concentrate on

the division between pro- and anti-Macedonians,6 despite the difficulty of

establishing which label is applicable in every case.7

In this paper I shall question the centrality of the Macedonian issue in

Athenian politics. Obviously there were occasions from 338 when Macedonia

must have dominated any debate in Athens, and the casualties of Chaeronea

kept the memory of that disaster alive, but equally obvious are the extended

periods when there was little immediate reason for the Athenian Assembly to

worry about the Macedonians.

After Chaeronea there was a general awareness in Athens of the danger of

provoking an armed confrontation with Macedon, but a common desire to hit

back if the opportunity arose. Thus in 338 the Areopagus acted to prevent

Charidemus taking a generalship and promoted the appointment of Phocion to

37

This content downloaded from

82.199.213.103 on Sat, 02 Dec 2023 19:36:46 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

a special position with emergency powers (Plut. Phoc. 16, 4); in 336, when it

became plain that Philip's assassination had not liberated Greece, Athens

surrendered to Alexander without any military action (D.S. 17, 4, 4 sq. and

A. 1, 1, 2-3); in 335 Demosthenes persuaded the Assembly to send help to

Thebes, and the Thebans received gear but no troops;8 and when Alexander

attacked Thebes Athens sent ten envoys to congratulate him on his safe return

from Thrace (A. 1, 10, 3). Alexander demanded the surrender of eight

prominent Athenians as hostages, but was persuaded to reduce his demand to

the exile of Charidemus.9 Charidemus escaped to the Persian court, and

perhaps at the same time Ephialtes left Athens to join the Persian forces in

Asia Minor (C.R. 3, 2, 10 sq., D.S. 17, 30, 2-6 and 25, 6 sq.). Both men

had a record of active opposition to Macedon: Charidemus, a mercenary

captain, had been nominated 'strategos' after the disaster at Chaeronea, and

earlier Ephialtes had ferried money in from Persia and was described as a

demagogue (Dinarchus 1, 33; Plut. Mor. 847 F). These two were, then, militant

anti-Macedonians, who had enjoyed considerable popular support, and their

departure from Athens is an indication that they could not now count on the

sympathy of established political leaders. Alexander's sack of Thebes cooled the

hot-heads and from 335 the political scene seems to be characterized not so much

by a division between pro- and anti-Macedonians as by a consensus that direct

military action against Macedon was not a practical strategy, and that a more

pragmatic policy was required.

When Alexander opened hostilities in Asia Minor in 334, Athens was given a

little respite from his attentions, but problems arose when Athenian prisoners

of war taken at the Granicus were shipped to Macedonia to do heavy labour:

this demanded a response from Athens, since that was no way to treat non

barbarian prisoners of war. But Alexander somewhat blunted the Athenians'

reaction by sending 300 panoplies to Athens as a thank-offering to the goddess

Athena (A. 1, 16, 7). It was only in the spring of 333 that the first recorded

Athenian mission to secure the release of the Greek prisoners of war reached

Alexander, and they were fobbed off with a promise that the matter would be

attended to when the Persian war was over (C.R. 4, 1, 9; A. 1, 29, 5-6). As

Alexander was in danger of losing control of the Aegean at the time, we should

consider the Athenian approach as low-key. The next recorded appeal to

Alexander was in the spring of 331, and then he obliged by agreeing to release

the prisoners of war, or, as Arrian has it, only the Athenian prisoners (3, 6, 2:

contrast C.R. 4, 8, 12). Not everyone would have rejoiced at this clemency,

since mercenaries could be a destabilising influence in a city, and Athens was

presumably held responsible for seeing that her citizens who were released from

Macedonia did not engage in further actions against Macedonia and the

Corinthian League.

Another indication that Athenian policy towards Macedon was cautious from

334 lies in the references to secret missions made to the Persian court. When

Darius was defeated at Issus, in 333, an Athenian, Iphicrates, was amongst the

38

This content downloaded from

82.199.213.103 on Sat, 02 Dec 2023 19:36:46 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Greek envoys captured in Darius' camp.10 The Athenians had to work on the

assumption that Alexander might be defeated by Darius, but they made contact

with the Persians through the son of an illustrious mercenary, rather than

through a prominent Athenian politician, whose capture by the Macedonians

would be more compromising. Not surprisingly Greek envoys to Darius'

court were captured after the battle of Gaugamela and again the Athenian envoy

was not a prominent political figure.11

Speech 17 in the Demosthenic corpus was perhaps not written by Demosthenes

but gives a clear example of the hawkish talk that was fashionable in 331 BC.12

This speech reflects the frustrations of ordinary Athenians, or perhaps one

should say that it played on their frustrations. The tone is hawkish, but the

argument carefully supports the existing order: Macedon had established

tyrannies in Messene and Pellene, and now was the time to oppose these tyrants

and to resist interference with the constitutions of League cities. The establish

ment of tyrannies meant arbitrary executions and other outrages: in Pellene it

meant revolution, as citizens lost their property to slaves, and it meant

dictatorship, the dictator being in this case a professional wrestler. The speaker

goes on to appeal to the propertied class, reminding them that the original treaty

had guaranteed that there would be no land redistribution, no summary confis

cations, no debt cancellation, no manumission of slaves and no revolution (15).

Another line of the argument is that Alexander had not hesitated to use force

and Athenians, as a matter of pride, should not tolerate this. Greeks and

barbarians feared to incur Athens' enmity; the Macedonians should be taught a

healthy respect for Athens (23). The orator cites as the most insulting and

outrageous contravention of the treaty the recent appearance in the Peiraeus of

a Macedonian trireme (26). The Macedonians wanted to use the Athenian

shipyards for the construction of ships for the federal fleet: the speaker rejects

this as an imperialist plan, but does not argue why it would be imperialist.

A third important section of the speech refers to the interception of corn ships

from the Back Sea—perhaps in 332—by Alexander's ships. No one living in

Attica could fail to appreciate the danger of a blockade to starve Athens of corn,

and here the speech puts the most telling argument in favour of armed resistance

to Macedonia.

There is no mention of war in Asia, and no clear suggestion is made as to what

should be attempted in Greece. The speech is generally a defence of Athenian

traditions—one of the traditions being a superiority complex—and the speaker

also defends the establishment figures against the nouveaux riches (νεόπλουτοι),

Macedon's agents and fellow-travellers.

The clearest evidence of reluctance to clash with Macedon comes in 331, when

Agis III initiated an uprising against Antipater: there was a popular movement

in favour of mobilising a fleet to assist Agis, but Demades, who is later attested as

being on friendly terms with Antipater,13 indirectly squashed this move by

persuading the people that the money should rather stay in the theoric fund

and be used to the direct benefit of the citizens (Plut. Μ or. 818 E-F).

39

This content downloaded from

82.199.213.103 on Sat, 02 Dec 2023 19:36:46 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Demosthenes made hawk-like noises (Plut. Dem. 24,1), but did not exert himself

to push Athens into war, for Aeschines soon after the event was able to talk of

Demosthenes' silence on the subject (3, 165-6). It has been suggested that

Demosthenes was related to Demades,14 but the evidence is fragile, and it

certainly could not be maintained that Demosthenes was only reticent in

deference to a relative, for it seems that he took active measures to placate

Alexander, whether after or in anticipation of Agis' defeat: his friend Aristion

was despatched to make contact with Hephaestion and then Alexander, and to

deliver a letter seeking reconciliation—a term that is ambiguous, covering

inter-state as well as personal relationships.15

Agis' rapid demise justified the Athenian decision not to get involved in the

war, and Athens benefited from her non-intervention as Alexander made

conciliatory gestures (A. 3, 6, 2 and 16, 8). Nevertheless the failure of this

resistance movement provided ready material for politicians in Athens to attack

those who had opposed active support for Agis. It was in this context that

Aeschines revived, or was manoeuvred into reviving, the action against

Ctesiphon, which turned into an indictment of Demosthenes' vacillating and

ineffectual record, in particular from the time of the battle of Chaeronea. The

trial of Ctesiphon and the trial of Leocrates for treason, also in 330, lend weight

to the old orthodoxy that policy vis-ä-vis Macedon was an essential element in

the labelling of any Athenian political 'party' in this era.16 The orthodoxy was

questioned by Sealey (JHS 76 (1956) 80 sq.) and Badian (JHS 81 (1961) esp. 32).

Nevertheless this labelling goes on, presumably inspired by the desire to establish

that Athenian politicians were fundamentally patriotic, for whilst the fallacy of

interpretation by anachronistic analogy is taboo, the fallacy of ethical positivism

thrives:17 thus E.M. Burke characterizes Lycurgus and Demosthenes as

'adamant anti-Macedonians', says that 'patriotism, with Macedon as the focal

antithesis, was at the heart of that (Lycurgan) programme', and argues that it

was Demosthenes who trapped Aeschines into reopening the case against

Ctesiphon in 330 so that he could exploit the trial to reinvigorate opposition to

Macedon, and Fordyce Mitchel argues that, whereas there was no agreement on

tactics, Athenian leaders were essentially at one in looking for the dissolution

of the Macedonian empire.18

Mitchel rejects the idea that Aeschines was pro-Macedonian and dismisses

Tarn's theory that the trial of Ctesiphon was staged by 'friends of Macedon' to

exploit the embarrassment of their opponents. He takes Aeschines' miserable

failure to muster 20% of the jurors' support as an indication that Aeschines acted

from personal pique and miscalculated his own powers of persuasion.19 It may

be that the value which Mitchel attaches to patriotism has led him to

overestimate the importance of foreign policy in Athenian politics in 330, for his

presentation of the trial leaves out a crucial element in the story, as 330 marked

a grave domestic crisis, primarily because corn rose in price to 16 drachms a

medimnos (Dem. 34, 39), against the usual price of 5 drachms, and the

corn shortage continued into 329 as domestic production was very low. People

40

This content downloaded from

82.199.213.103 on Sat, 02 Dec 2023 19:36:46 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

had to queue to collect their ration of corn, and many were trampled underfoot

as the unruly broke line and surged to the front; bread prices were controlled,

and the old law that no Athenian citizen or metic could convey corn to any port

other than the Peiraeus was strictly enforced (Dem. 34, 37).

The mining industry ran into a bad spell between 330 and 328,20 which may be

explained by Alexander's redeployment of the wealth he had taken from Persian

treasuries and the competition of the mint which Alexander established in

Sicyon in about 330. Furthermore a number of building projects seem to have

come to an end in about 330—notably the shipsheds and arsenal at the

Peiraeus, the Panathenaic stadium, and the theatre of Dionysus,21 and, whereas

new projects were initiated, the transitional period must have been unsettling for

those involved.

The surviving speeches from the trials of Ctesiphon and Leocrates reflect the

tensions in Athenian society in 330. Aeschines prosecuted Ctesiphon for

irregularities in his proposal to honour Demosthenes in 336, but used the

occasion to attack Demosthenes for building up a false reputation as an

opponent of Macedonian militarism. Both Aeschines and Demosthenes lashed

out freely with accusations of corruption and bribe-taking, and Demosthenes

underlined the economic implications of his policy: the war he advocated in 340

made goods cheaper and more plentiful in Athens than they were in the

'peacetime' conditions of 330; he blamed the doves for the current shortages

and high prices (18, 89); then in dealing with his trierarchic law of 340

Demosthenes stressed his concern to save the poor from oppression, and he

related his struggle against the wealthy, who tried to buy off his reform proposals

(102-9). In attacking Aeschines, Demosthenes played on his wealth: Aeschines

had become a greasy horse-breader, with Alexander's help (320). Given that the

subject was policy vis-ä-vis Macecjon, one might be surprised at the high

incidence in Demosthenes' speech of the antithesis rich-poor.

Lycurgus' case against Leocrates similarly related directly to much earlier

events, for this prosperous business-man was charged with treason for his

actions after the battle of Chaeronea. Leocrates had quit Athens and interfered

with the supply of corn to Athens, first by misinforming the Rhodians so that

they stopped shipments of grain to Athens, and secondly by engaging in the sale

of Epirote corn to Corinth instead of Athens (Lycurgus c.Leocr. 18 and 26).

Lycurgus broadened his attack to cover all horse-breeders and chorus patrons

and lavish spenders (139-140), and went gunning for aliens, slaves and the

disfranchised.

Two other themes play an important part in the speech: first is a fundamentalist

advocacy of loyalty to the state, and in support of his aggressive patriotism he

quotes lengthy passages from Homer, Tyrtaeus and Euripides: this call to

patriotism in a state not under immediate military threat is surely illiberal. The

second theme relates to democracy, or more precisely the demos, and the laws,

terms that appear constantly in the speech and are often linked.22 Lycurgus is

not eulogising democracy as the facilitator of open debate and the means to

41

This content downloaded from

82.199.213.103 on Sat, 02 Dec 2023 19:36:46 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

accommodate divisions of opinion: he is talking rather of the people as a united

front, defending a well-established code of laws, not only for their own

preservation but also as a divine mandate (146). Again Lycurgus' standpoint

is illiberal.

Lycurgus's attitude is intelligible against the background of the domestic crisis

of 330, and the external menace was not simply Macedonian militarism but also,

at a more political level, the unsettling effect of the long history of civil unrest

that had rocked other cities in Greece. These disturbances have been well

reviewed by A. Fuks in a series of articles in which he shows how Isocrates and

Plato observed and reacted to the problems.23 Features of Isocrates' experience

were stasis, murders, robberies, cancellation of debts, redistribution of land,

and the revision of constitutions. The growing divide between rich and poor

upset the social order and caused the abuse of political power. E. Ruschenbusch

has argued that Aristotle misrepresented political unrest in Greece and that

class warfare was not the characteristic of politics in the fourth century,24 but

whatever the general pattern of Athenian politics in the fourth century, it seems

to me that the crises which dotted the period 338 to 323 threatened the political

and social order, and exposed fundamental divisions in Athenian society which

were concealed in more tranquil times by the veneer of conventional political

exchanges.

As various new factors came into play when the next crisis hit Athens in 324,

we can interrupt the narrative at this point to consider certain general features of

the political history of the late 330s and early 320s. There was an interaction

between the dominant problem in foreign affairs and the socio-economic stresses

that developed in Athens.

In the speeches of this period there is a heavy emphasis on patriotism: for

instance, in Lycurgus' speech against Leocrates; and the threat of Macedonian

aggression served to oblige the Athenians to present a common front. Politicians

advocated a variety of strategies ranging from open defiance to collaboration

and accused their opponents of selling out to Macedon, but none would openly

reject patriotism in favour of absorption into the Macedonian empire. There

were positive disincentives to overt collaboration, including Eucrates' law of

336, which re-enacted earlier provisions against the dissolution of the democratic

constitution and introduced a new clause dictating the loss of all citizen rights

for any Areopagite who should participate in any government set up after the

dissolution of the democracy, and the warning was re-emphasized by the

erection of a statue of Demokratia by the Boule in 333/2 and the sacrifices

offered to Demokratia by the generals in 332/1 and 331/0.25 However patriotic

the rhetoric, many politicians were accused of being in the pay of Macedon and

were referred to as Macedon's mercenaries:26 such charges were levelled against

Demades, Euxenippus, Demosthenes and Aeschines, and Phocion was credited

with a steady refusal to accept Alexander's offers.27 We can accept as fact that

Alexander did attempt to buy political leaders and clearly some Athenians

yielded to the temptation, which suggests that, at least from 334, the menace of

42

This content downloaded from

82.199.213.103 on Sat, 02 Dec 2023 19:36:46 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Macedon was less of a reality than its presentation in patriotic speeches.

Policy decisions taken in this period reveal a concern to avoid military action

that would be suicidal and an equal concern to avoid the imposition of a puppet

regime which might be obliged to harass or outlaw its opponents. A middle

course was followed: measured resistance, asserting Athens' determination to

remain autonomous, but stopping short of provocative acts that would justify

military intervention by Macedon. Thus walls, shipsheds and a naval arsenal

were built, and probably soon after Chaeronea Lycurgus organised the reform

of the ephebate, obliging all 18 year olds to enrol for two years military training

and service.28

The practical effect of the reform on the ephebate was that Attica was

protected against surprise attacks, the Periclean principle that Attica should not

be defended against infantry and cavalry was abandoned and, at the same time,

military action was to a certain extent ritualized. Arguably this form of national

service made active involvement in hostilities less likely. Experience had shown

that ad hoc mobilisation of the citizen army created existential situations with

unintended political outcomes.

The reconstituted ephebate was, therefore, a form of measured resistance to

Macedon, and in support of this strategy Lycurgus sought to stimulate the

economy by an extensive public works programme, including the construction

of shipsheds and walls, and perhaps also by the enforced sale of unworked farm

land, which both raised money for the state and made extra land available to

those who wished to invest in agriculture.29

Lycurgus' economic policy of mobilising wealth for construction projects and

his policy of avoidance of a military confrontation with Macedon clearly had a

very different effect from that of Pericles' strategy in the Peloponnesian War.

Pericles' policy disrupted agriculture and led to the closure of the mines at

Laurium, whereas Lycurgus promoted a strengthening of the Athenian

economy. Pericles saw Sparta as a challenge, whereas Lycurgus and his

supporters and like-minded leaders saw the threat of Macedon as the means of

uniting Athenians under the conservative leadership of their own class. In other

words, I suggest that just as Isocrates saw the Persian king as the figure who

could unite Greeks in opposition to him, so there were Athenian leaders wo saw

that hostility to Macedon could be worked up to unite the Athenians.

The economic problems of this period may explain another feature of the

political scene, a feature which is all the more striking in view of the chauvinist

tone of speeches on foreign policy.

Athenian politicians were generous in their promotion of proposals to extend

property rights to aliens in this period,30 and even to accord citizenship to

non-Athenians.31

There was good cause to reward entrepreneurs who had helped to ferry corn

to Athens when supplies were low, and if wealthy metics were encouraged to

make Athens their permanent home, that could only strengthen the position of

the Athenian aristocracy.

43

This content downloaded from

82.199.213.103 on Sat, 02 Dec 2023 19:36:46 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

In the aftermath of Chaeronea, Hypereides even proposed that all metics

should be made citizens (Plut. Mor. 848 F-849 A) and this could have benefited

up to 10000 (the number supposedly counted in the census of c.317 BC:

Athenaeus 6, 272 C). Though the measure was apparently not passed, this

amazingly drastic plan adds to the picture of the political crisis of 338/7. For

enfranchisement on this scale, plus the manumission of 150 000 slaves (Hypereides,

Frag. 18), may have been intended to sound so drastic as to compel the citizens

to unite to work out a more conservative solution to the crisis.

If Hypereides intended his proposal to be taken seriously or was hoping for

some compromise, we need not assume that his concern was to promote radical

democracy, for any metics enfranchised would have been classified according

to the normal property qualifications and would thus not have constituted a

united group within the body politic, and experience would have taught the

metics that privileges were revocable, and this would have inhibited the

expression of radical views: metics once enfranchised might have been expected

to adopt a passive political attitude.32

Finally one more feature of Athenian politics in this period was the attack on

wealth accumulation and conspicuous consumption. This occurs constantly in

the forensic and political speeches, together with a careful defence of wealth

modestly acquired and patriotically invested, and the preoccupation with the

affairs of the rich is reflected in the incidence of court cases directed against

entrepreneurs. Hypereides says that the prosecution of mine lessees at one stage

became so common that investment in new mines ceased altogether, but at the

time of his speech for Euxenippus, some time about 330, a court ruling against

such intimidation had encouraged the development of new mines (Hyp. 4,

esp. 36).

R. von Pöhlmann, noting Demosthenes' invective against wealth, saw

Demosthenes as a member of the bourgeoisie, who nevertheless fostered the

masses' hostility to capitalism.33 Though we cannot accept Pöhlmann's brand

of modernisation of Athenian history, we can accept the paradox in the orators'

attack on the wealthy, and it may be interpreted as a defensive political tactic.

The political establishment was badly shaken by the disaster at Chaeronea in 338,

and the shortage of corn that was desperate in 330 and continued for a few years

created a situation that threatened political stability. Against this background

Athenian leaders attacked vulgar greed and conspicuous consumption and

supported a policy of redistributing wealth in a limited way, and in so doing

presumably hoped to neutralize any incipient radical movement. Lycurgus'

rhetoric was directed at uniting the people with chauvinist arguments. He called

for unquestioning defence of the democracy, and, as we have noted, his concept

of democracy was highly illiberal, with the emphasis on the citizen's obligation

to be steadfastly loyal to the laws, traditions embodied in patriotic literature and

the ephebate oath.

In fine, Lycurgus and most members of the upper class,34 despite their

personal differences and disagreements on a variety of issues, were set against

44

This content downloaded from

82.199.213.103 on Sat, 02 Dec 2023 19:36:46 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

military adventurism and were apprehensive about the potential political power

of the poorer citizens: Lycurgus' defensive measures and economic programme

were a constructive alternative to risky campaigns and chauvinist speeches and

attacks on unpatriotic materialists were to appeal to the sort of people who in

338 had clamoured for the conferment of emergency powers on Charidemus.

Of course this is not to say that Lycurgus' opponents viewed the issues in the

same light. Propagandists tend to have ill-justified faith in their powers of

persuasion and to be locked into focus on their own picture of political realities;

one has to record that Lycurgus failed by one vote to get the conviction of

Leocrates (Aeschines 3, 252-3) and, as is well known, Aeschines could not

muster even 20% of the jurors' votes. When personal animosity was the real

reason for so many political trials,35 the jurors became cynical (cf. Lyc. c. Leocr.

3) and were inclined to acquit when a man had been convicted in a preliminary

hearing before the Areopagus (Dinarchus 1, 54 sq; cf. Lyc. c. Leocr. 52). The

forcefulness of the patriotic oratory was weakened by the memory of the

inglorious apologies made to Philip and Alexander in 338, 336 and 335, and by

the welter of accusations of bribe-taking.

Lycurgus' reforms and development programme were successful enough in

staving off stasis, and the war was averted, but the political order was unstable

and its frailty was exposed in the crisis that developed after Lycurgus' death in

324, when Leosthenes' arrival in the Peloponnese heralded a fresh confrontation

with Macedon, Harpalus' unwelcome arrival in Athens led to many prominent

figures being charged with bribery, and Nicanor's proclamation concerning the

return of exiles struck at a vulnerable point in the Athenian economy. Diodorus

explains that Athens was almost alone amongst the Greek states in viewing the

return of exiles as unwelcome, for Athenian cleruchs on Samos would have to

restore the island to the Samians (D.S. 18, 8, 6-7). The economic importance

of Samos to the Athenians explains their general concern to retain control of the

island: Athenian cleruchs had been settled there apparently since 361,36 and

Athens presumably did not want to have to find land for returning settlers.

Demosthenes apparently bought time on the issue of Samos, for the question

whether Athens was to retain control of it was unclear to Antipater in 322, and

was decided in the Samians' favour by Perdiccas.37

Demosthenes was the central figure in the scandal over the misappropriation

of part of Harpalus' treasure. Badian, in his detailed discussion of this episode,

presents Demosthenes as 'caught in the web of his own intrigues',38 for he had

compromised himself by participating in secret negotiations with Leosthenes

(Hypereides c.Dem. 12-13) and by heading the mission that negotiated with

Nicanor (Din. 1, 81 sq.).

When the scandal broke, 'the people' clamoured for the prosecution of the

bribe-takers and hustled the Areopagus to complete the preliminary investiga

tion,19 but as the procedure dragged on, Dinarchus' impression seems to have

been that indignation had given way to apathy (3,3,14 and 15), and in the case

of the minor offenders the jurors were presumably reluctant to satisfy the

45

This content downloaded from

82.199.213.103 on Sat, 02 Dec 2023 19:36:46 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

animosity of informers and prosecutors.40

Thus the outcome of the trials was not a victory for radicalism or rabid anti

Macedonian sentiment:41 indeed the prosecutions for the misappropriation of

Harpalus' loot could have been exploited as a conciliatory gesture in dealings

with Alexander. However, Athens had given aid and recognition to Leosthenes,

and though it was possible in the spring of 323 to obviate war, the death of

Alexander administered another shock to the Athenian political system. Athens

was forced to decide whether or not to risk war, but Lycurgus was dead,

Demosthenes in exile, and Phocion at a disadvantage over against Leosthenes,

who had the means to fight, and Hypereides who had the political advantage of

having been a prosecutor in the bribery trials. Caution was abandoned and

Athens opted for war. Diodorus Siculus' account of Athens' decision to start

hostilities echoes Plutarch's account of the bid to give Charidemus special

powers after the disaster at Chaeronea in 338, for in 323 the men of property

advocated a quietist policy, whereas demagogues stirred up the masses and

incited them to vote for war (18, 10, l).42

To sum up, the crises of the period 338-323 exacerbated what I think can fairly

be described as class differences, and Alexander's destruction of Thebes

produced a consensus amongst most political leaders that active military

resistance to Macedonia was not a practical option. Chauvinist speeches and the

Lycurgan programme of reforms and building and defence projects was aimed at

avoiding military adventures and easing tensions within Athenian society.

Lycurgus' political statements were illiberal, indeed almost 'fascist', and were

motivated by a concern to strengthen the position of the liturgical class. As

Alexander disintegrated and the political establishment in Athens was shaken

and divided by the Harpalus scandal in 324, radical leaders urged the poorer

citizens to use their voting power and opt for war. That class was significant in

this change of policy is indicated by the fact that when Macedon re-established

control over Athens, Antipater disfranchised some 12000, and left with full

citizenship only the 9 000 who satisfied a property qualification of 2 000 drachms.

I presume that Lycurgus would have approved.

NOTES

1. A version of this paper was presented at the conference of the Classical Association of

South Africa held in Durban in January 1981. In the source references I abbreviate Diodoru

Siculus as D.S., Curtius Rufus as C.R. and Arrian as A.

2. Cf. G.T. Griffith, A History of Macedonia, vol. 2, Oxford 1979, 596 sq.

3. Plut. Phocion 16, 4; cf. H-J. Gehrke, Phokion, Munich 1976, 61.

4. It is not my immediate concern to defend the use of the term 'class' in the context o

Athenian political history; suffice it here to refer to the discussion of this issue in E.M. Wood

and N. Wood, Class ideology and ancient political theory, Oxford 1978.

5. R. Sealey, JHS 75 (1955) 81, citing Dem. 15, 17-21; P. Rhodes, LCM 3 (1978) 208.

6. Cf. C. Mosse's observation that 'even after Chaironea the attitude towards Macedon wa

not the sole principle on which Athenian opinion was divided. It was however an essentia

factor . . .' (Athens in decline, London 1973, 84).

46

This content downloaded from

82.199.213.103 on Sat, 02 Dec 2023 19:36:46 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

7. Labels such as μισαλέξανδρος (Aesch, 3, 73), μισοφίλιππος (Aesch, 2, 14) and

μακεδονίζων (Plut. Dem. 24, 2; Alex. 30, 8) have to be treated as cautiously as similar labels

bandied about during the Peloponnesian War, on which see W.R. Connor, The New Politicians...,

Princeton 1971.

8. D.S. 17, 8, 5-6 and Plut. Dem. 23, 1; the sources may mean that Athens sent armour

and not weapons.

9. A. 1, 10, 4-6; Plut. Dem. 23, 4; the sources differ on the number of men whose surrender

Alexander demanded.

10. A. 2, 15.2, with my Commentary on Curtius Rufus' 'Historiae Alexandri' Books 3 and 4,

Amsterdam 1980, 261 and 465-5, where I suggest that, if Iphicrates was accompanied by

Aristogeiton, the latter was not the famous son of Cydimachus.

11. A. 3, 24, 4 with my commentary on C.R. 3, 13, 15.

12. On the date of the speech G.L. Cawkwell, Phoenix 15 (1961) 74 sq.

13. D.S. 18, 48, 2; Plut. Phocion 30, 4.

14. Badian JHS 81 (1961) 34, cf. F.W. Mitchel, 'Lykourgan Athens', in Lectures in memory

of L.T. Semple, 2nd series, Univ. of Oklahoma Press 1973, esp. 176 (hereafter 'Lykourgan

Athens'); but J.K. Davies, Athenian propertied familes (hereafter A PL), Oxford 1971, 99 sq.

casts doubt on any such family connection and notes, incidentally, that Demades' father

belonged to 'the shipping circles of Peiraieus' rather than to 'the squirearchy of the Mesogeia'.

15. Jacoby FGH no. 135/6, F.2; Aesch. 3, 162, with Dem. 1, 4 and 2, 1 for the use of

diallage and katallage in diplomacy. On the collaboration of Demosthenes and Demades from

335 see A. Lingua, GIF 30 (1978) 27-46, known to me indirectly.

16. Such labelling can be found, for example, in Tarn's contribution to CAH vol. 7, A.

Schaefer, Demosthenes und seine Zeit', Leipzig 1887 (Olms 1966), esp. iii, 190 sq. and Claude

Mosse, Athens in decline, 1973, esp. 84-5.

17. Cf. G.L. Cawkwell's observation in his "Eubulus", 7//.S'83 (1963) 67:.. it is easy to pass to

classifying politicians as pro- and anti-Macedonian. This may be improving, but.it is not history'.

For the political influences that worked on rival presentations of Demosthenes from the mid

nineteenth century see H.B. Dunkel, CP 33 (1938) 291 sq., reprinted in Philip and Athens, edited

by S. Perlman, Cambridge 1973.

18. Burke, Phoenix 31 (1977) 330 sq., esp. 335-7; F.W. Mitchel, 'Lykourgan Athens', 165 sq.

19. 'Lykourgan Athens' 184.

20. Hypereides4, 35-6 with Dem. 42, 3 andS. Isager andM.H. Hansen, Aspects of Athenian

society in the fourth century BC, Odense Univ. Press 1975, 43.

21. IG if, 1627, 279 sq.; F.W. Mitchel, 'Lykourgan Athens' 196 sq.

22. c. Leocr. 20, 142, 149 and 150 in particular.

23. See especially Ancient Society 3 (1972) 17-44; 8 (1977) 49-83; 10 (1979) 33-78.

24. Untersuchungen zu Staat und Politik in Griechenland . . ., Bamberg 1978, known to me

indirectly through the reviews by Lewis, CR 30 (1980) 77-8 and Lotze, Gnomon 52 (1980) 381-2.

25. Eucrates' law: Hesperia 21 (1952) 355-6; the statue: Raubitschek, Hesperia 31 (1962)

238 sq.; the sacrifices: IG ii2, 1496, lines 131-2 and 140-1.

26. [Dem.] 17, 11, Hypereides 4, 22.

27. Plut. Phoc. 18 and 30; Hypereides 4, 21 sq.; Dinarchus 1, 28 sq.; Dem. 18, 41 and

320 and 19, 145.

28. O.W. Reinmuth, Ephebic inscriptions . . ., Leiden 1971, with E. Ruschenbusch, 'Die

soziale Herkunft der Epheben . . .', ZPE 35 (1979) 173-6.

29. Cf. D.M. Lewis, 'Athenian rationes centesimarum', in Problemes de la terreen Grece

ancienne, Paris 1973, 187 sq.

30. IG ii2, 237, 342, 351, 425, 360, 343 with J. Pecirka's discussion in The formula for the

grant of enktesis . . ., Prague 1966.

31. IG ii2, 237, 350, and 405; Aeschines 3, 85; Dinarchus 1, 43.

32. Cf. D. Whitehead, The ideology of the Athenian metic, Cambridge 1977, esp. 57 sq. on

Lysias; the metic Dinarchus expressed support for the Areopagus (1, 7 sq.) and eulogised

Athens' hegemonial and democratic traditions (I, 37 sq.).

33. Geschichte der sozialen Frage . . ., Munich 21925, i, 255.

34. J.K. Davies in the Introduction to his APFargues that liability for liturgies may be taken

as the criterion for defining membership of the 'upper class' and notes as of particular relevance

Politics 1291 33-4. Such a legalistic definition cannot give us the whole picture and we lack

the evidence to decide how the men in the middle of the social spectrum recognised their class

47

This content downloaded from

82.199.213.103 on Sat, 02 Dec 2023 19:36:46 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

affiliation. Nevertheless Davies provides us with a rough working definition, since eligibility for

liturgical services is clear evidence of relative wealth.

35. Cf. M.H. Hansen, Sovereignty of the People's court . . ., Odense U.P., 1974, 62 sq.

36. RE 1A, 2216. The absence of the cleruchs eased the pressure on the corn supplies in

Athens, and continuing concern with guaranteeing adequate grain supplies is reflected in the

decision of 325/4 to plant a colony on the Adriatic and the honours paid in the same year to a

Cypriote from Salamis for his help in the past when corn was short: IG ii , 1629 170 sq. and

IG ii2, 360.

37. D.S. 18, 18, 6 and 9; significantly Hypereides and Dinarchus are silent on the outcome of

Demosthenes' negotiation with Nicanor.

38. E. Badian, JHS 81 (1961) 39.

39. Hypereides 5, 5, cf. Cinarchus 1, 4 and 2, 20 sq.

40. As Badian noted (JHS 81 (1961) 32 and 35), neither the prosecutors nor the accused

constitute a homogeneous group on the evidence available to us. The scandal gave opportunity

for the settling of old scores, thus it is not surprising that Hypereides was a prosecutor and

Aristogeiton one of the accused, and that Aeschines' friend Pytheas was a prosecutor while

Demosthenes was on trial. The untidiness of the politics of the trials was reflected in the length

of time taken by the Areopagus over the preliminary investigation (Dinarchus 1, 45), the

acquittal by the jury court of some of those listed by the Areopagus and the setting of fines

below the statutory level (Din. 1, 60 and Hyp. 5, 24).

41. The prosecutor Pytheas was a 'genuine radical' (Mitchel), likewise Stratocles (Ferguson

Hell. Athens 13), but so too was Aristogeiton (Mitchel) and he was one of the accused; Pytheas

was an ardent anti-Macedonian (Treves) and thus a suitable co-prosecutor with Hypereides,

but not if one follows J.A. Goldstein, who describes Pytheas and Menesaechmus as pro

Macedonians (The letters of Demosthenes, Columbia Univ. Press 1968, 55 and 224-6).

42. Cf. D.S. 17, 111, 1. Not surprisingly Hypereides described the situation differently at

the time (6, 10).

48

This content downloaded from

82.199.213.103 on Sat, 02 Dec 2023 19:36:46 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Democracy For Brownies Badge BookletDocument8 pagesDemocracy For Brownies Badge Bookletmega small100% (1)

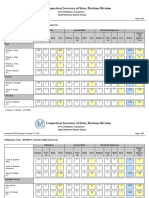

- Danbury November 2023 Municipal Election Returns (Amended)Document91 pagesDanbury November 2023 Municipal Election Returns (Amended)Alfonso RobinsonNo ratings yet

- Reso 09 - Approving and Adopting BDCDocument2 pagesReso 09 - Approving and Adopting BDCJoseph Sumaoy100% (4)

- Functions of SubcultureDocument6 pagesFunctions of SubcultureAlyssa Roan B. Bulalacao100% (2)

- War, Women, and Druids: Eyewitness Reports and Early Accounts of the Ancient CeltsFrom EverandWar, Women, and Druids: Eyewitness Reports and Early Accounts of the Ancient CeltsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- The Athenian Expedition To Melos in 416 B.C.Document35 pagesThe Athenian Expedition To Melos in 416 B.C.tamirasagNo ratings yet

- Kingdom PF The Forgotten Maccognail-Kelti U Ji EuropiDocument173 pagesKingdom PF The Forgotten Maccognail-Kelti U Ji EuropiTomislavMenalo100% (2)

- Demosthenes - On The CrownDocument68 pagesDemosthenes - On The CrownOriol Peñalver BarnetNo ratings yet

- Battle Report: The Battle of Chaeronea 338 BCDocument11 pagesBattle Report: The Battle of Chaeronea 338 BCBakarovPetreNo ratings yet

- Themistocles and His Part On The Greco-Persian Wars (499-472/1)Document14 pagesThemistocles and His Part On The Greco-Persian Wars (499-472/1)Juan A. Caballero PrietoNo ratings yet

- Grainger 1996 - Antiochos III in ThraceDocument16 pagesGrainger 1996 - Antiochos III in Thraceruja_popova1178No ratings yet

- Badian The Administration of The EmpireDocument18 pagesBadian The Administration of The EmpirealverlinNo ratings yet

- Athenian Synoikism of The Fifth CenturyDocument21 pagesAthenian Synoikism of The Fifth CenturyEve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- Archers of Classical AthensDocument17 pagesArchers of Classical Athensmichael_baroqNo ratings yet

- Subject: Global History and Geography I Unit 3: Ancient Western World Content StandardsDocument10 pagesSubject: Global History and Geography I Unit 3: Ancient Western World Content Standardsapi-284802763No ratings yet

- P. A. Brunt: Greece & Rome, 2nd Ser., Vol. 12, No. 2, Alexander The Great. (Oct., 1965), Pp. 205-215Document12 pagesP. A. Brunt: Greece & Rome, 2nd Ser., Vol. 12, No. 2, Alexander The Great. (Oct., 1965), Pp. 205-215Iordanita DoditaNo ratings yet

- Starr, C. (1978) - Thucydides On Sea Power. Mnemosyne, 31 (4), Fourth Series, 343-350Document9 pagesStarr, C. (1978) - Thucydides On Sea Power. Mnemosyne, 31 (4), Fourth Series, 343-350SAPERE Analía VerónicaNo ratings yet

- McKinney Thucydides CSD2015Document30 pagesMcKinney Thucydides CSD2015Astelle R. LevantNo ratings yet

- Ancient Crete and Minoan CivilationDocument103 pagesAncient Crete and Minoan CivilationΑδαμάντιος (Μάκης) Γ. Κρασανάκης100% (2)

- Affective Epigraphy Emotions in Public PDFDocument16 pagesAffective Epigraphy Emotions in Public PDFOlga PelcerNo ratings yet

- Peloponnesian War Essay ThesisDocument5 pagesPeloponnesian War Essay Thesisannmontgomeryjackson100% (2)

- Mccoy WJ Memnon of Rhodes at The GranicusDocument22 pagesMccoy WJ Memnon of Rhodes at The GranicusIván Giménez100% (1)

- Cawkwell (1978phoenix) Euboea in Late 340sDocument27 pagesCawkwell (1978phoenix) Euboea in Late 340sDániel BajnokNo ratings yet

- Research Paper GreeceDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Greecefv9x85bk100% (1)

- Themistocles and The Supposed Second Message To Xerxes - The Anatomy of A LegendDocument14 pagesThemistocles and The Supposed Second Message To Xerxes - The Anatomy of A LegendMatheus Moraes MalufNo ratings yet

- Antigonus the One-Eyed: Greatest of the SuccessorsFrom EverandAntigonus the One-Eyed: Greatest of the SuccessorsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Oliver, J. H. (1981) - Roman Emperors and Athens. Historia. Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte, 30 (4), 412-423Document13 pagesOliver, J. H. (1981) - Roman Emperors and Athens. Historia. Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte, 30 (4), 412-423Analía SapereNo ratings yet

- Journals Mnem 31 4 Article-P343 1-PreviewDocument2 pagesJournals Mnem 31 4 Article-P343 1-PreviewVõ Lập PhúcNo ratings yet

- The Johns Hopkins University Press The American Journal of PhilologyDocument5 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University Press The American Journal of PhilologyShahenda AnwerNo ratings yet

- Curses and Social Control in The Law CourtsDocument23 pagesCurses and Social Control in The Law CourtsEve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- Quotes About MacedoniaDocument44 pagesQuotes About MacedoniaMacedonia - The Authentic TruthNo ratings yet

- Theramenes Via XenophonDocument12 pagesTheramenes Via Xenophonclockworkoasis7206No ratings yet

- The Faction Hostile To Alcibiades Triumphed in Athens Following A Minor Spartan Victory by Their Skillful GeneralDocument3 pagesThe Faction Hostile To Alcibiades Triumphed in Athens Following A Minor Spartan Victory by Their Skillful GeneralKahon KahoyNo ratings yet

- Menon of ThessalianDocument19 pagesMenon of ThessalianGEORGE FELIPE BERNARDES BARBOSA BORGESNo ratings yet

- China and The US. A Balance of PowerDocument17 pagesChina and The US. A Balance of PowerABRAHAM ALBERT DIAZNo ratings yet

- From 414 BCDocument4 pagesFrom 414 BCKahon KahoyNo ratings yet

- Franz Steiner Verlag Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte GeschichteDocument26 pagesFranz Steiner Verlag Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte GeschichteRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- The Harvest of War: Marathon, Thermopylae, and Salamis: The Epic Battles that Saved DemocracyFrom EverandThe Harvest of War: Marathon, Thermopylae, and Salamis: The Epic Battles that Saved DemocracyNo ratings yet

- Perikles Vs Thrace 447 BCDocument6 pagesPerikles Vs Thrace 447 BCmiron isabelaNo ratings yet

- The Greek Golden AgeDocument29 pagesThe Greek Golden AgeMaría José CarrilloNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Evidence On The Macedonian Question (By Ioannis Kallianiotis)Document22 pagesLinguistic Evidence On The Macedonian Question (By Ioannis Kallianiotis)Macedonia - The Authentic TruthNo ratings yet

- Tribute and Revolts in The Athenian Empire PDFDocument14 pagesTribute and Revolts in The Athenian Empire PDFcaracallaxNo ratings yet

- The Trojan War Chronological HistoricalDocument202 pagesThe Trojan War Chronological HistoricalParul Raheja100% (3)

- Plato's Description of Early Athens, and The Origin of MetageitniaDocument14 pagesPlato's Description of Early Athens, and The Origin of MetageitniaSWATAHSIDDHA SARKARNo ratings yet

- Hellenistic AgeDocument30 pagesHellenistic AgeCarolina TobarNo ratings yet

- Jones, W. H. S. - Greeks and Foreigners - CR, 24, 7 - 1910 - 208-209Document3 pagesJones, W. H. S. - Greeks and Foreigners - CR, 24, 7 - 1910 - 208-209the gathering100% (1)

- Greece Basic Facts WorksheetDocument5 pagesGreece Basic Facts WorksheetJackie McCarthyNo ratings yet

- Classical GreeceDocument2 pagesClassical GreeceJorgie GeulinNo ratings yet

- Solons Atlantis The Sources of Platos MyDocument17 pagesSolons Atlantis The Sources of Platos MyUmut YıldırımNo ratings yet

- The Dialogues of Plato - CritiasDocument18 pagesThe Dialogues of Plato - CritiasMichael WatsonNo ratings yet

- Greek CivilizationDocument22 pagesGreek CivilizationSittie Farhanna MutinNo ratings yet

- Hiera OrgasDocument22 pagesHiera OrgashoweNo ratings yet

- Athens Burning: The Persian Invasion of Greece and the Evacuation of AtticaFrom EverandAthens Burning: The Persian Invasion of Greece and the Evacuation of AtticaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Alexander 334–323 BC: Conquest of the Persian EmpireFrom EverandAlexander 334–323 BC: Conquest of the Persian EmpireRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- Article BCH 0007-4217 1956 Num 80 1 2408Document21 pagesArticle BCH 0007-4217 1956 Num 80 1 2408aguaggentiNo ratings yet

- 15 - Fourth-Century BC Greek WarsDocument5 pages15 - Fourth-Century BC Greek WarsAC16No ratings yet

- Atlantis: A Grain of Truth Behind The Fiction?: Massimo RapisardaDocument23 pagesAtlantis: A Grain of Truth Behind The Fiction?: Massimo Rapisardaasd asdNo ratings yet

- The Hyksos Invasion in History and TraditionDocument52 pagesThe Hyksos Invasion in History and Traditionmc823886392No ratings yet

- On AristotleDocument94 pagesOn Aristotlehassan sardarNo ratings yet

- Armies of Ancient Greece Circa 500–338 BC: History, Organization & EquipmentFrom EverandArmies of Ancient Greece Circa 500–338 BC: History, Organization & EquipmentNo ratings yet

- 第二章 希腊时期 识记要点Document2 pages第二章 希腊时期 识记要点svb128128128No ratings yet

- Bisaac, 05 005 DavidDocument16 pagesBisaac, 05 005 DavidmanuNo ratings yet

- Roseller Lim, Zamboanga SibugayDocument2 pagesRoseller Lim, Zamboanga SibugaySunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- De Jure: (Discrimination Against Traditional Beliefs of Cigugur Indigenous Community)Document18 pagesDe Jure: (Discrimination Against Traditional Beliefs of Cigugur Indigenous Community)Maman HungkulNo ratings yet

- SSSDR Bharat India ElectionResultsAudits CirculationNote 11.02.2024Document7 pagesSSSDR Bharat India ElectionResultsAudits CirculationNote 11.02.2024P Eng Suraj SinghNo ratings yet

- Are Republicans and Conservatives More Likely To Believe Conspiracy Theories?Document24 pagesAre Republicans and Conservatives More Likely To Believe Conspiracy Theories?Milan PetrikNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9. RizalDocument13 pagesChapter 9. RizalKim angela100% (1)

- Unit Test 7A Basic LevelDocument2 pagesUnit Test 7A Basic LevelМарія МалерикNo ratings yet

- Analisis Dasar Hukum Bahasa IndonesiaDocument11 pagesAnalisis Dasar Hukum Bahasa IndonesiaAchmad ApriadyNo ratings yet

- Turism SasiDocument37 pagesTurism SasiManole Eduard MihaitaNo ratings yet

- Our American Heritage EssayDocument2 pagesOur American Heritage Essayapi-200047101No ratings yet

- Full Download Holes Human Anatomy and Physiology 12th Edition Shier Test BankDocument35 pagesFull Download Holes Human Anatomy and Physiology 12th Edition Shier Test Bankbrimmed.pathway.0xsw2100% (42)

- Classical and Contemporary Sociological Theory Text and Readings 3rd Edition Appelrouth Test BankDocument35 pagesClassical and Contemporary Sociological Theory Text and Readings 3rd Edition Appelrouth Test Bankgeincupola.06zi100% (30)

- 1 - India Foreign PolicyDocument16 pages1 - India Foreign PolicyZahidNo ratings yet

- Es/Images/Admin/2020/Press/Scotusfiling - PDF: Amicus BriefDocument13 pagesEs/Images/Admin/2020/Press/Scotusfiling - PDF: Amicus BriefRobert B. SklaroffNo ratings yet

- San Manuel, PangasinanDocument2 pagesSan Manuel, PangasinanSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Elections Calendar 2023Document1 pageElections Calendar 2023Eva ParadiseNo ratings yet

- ANC 54th Conf Organisational ReportDocument44 pagesANC 54th Conf Organisational ReportPrimedia BroadcastingNo ratings yet

- Indian-Political-Thought One LinerDocument6 pagesIndian-Political-Thought One Linerarjun anjana anjanaNo ratings yet

- SOC SCI 120 Course PackDocument11 pagesSOC SCI 120 Course PackDarra TanNo ratings yet

- Guia de Ensayo 2 Ciclo Ingles 2 OpDocument10 pagesGuia de Ensayo 2 Ciclo Ingles 2 OpPolet Torres YañezNo ratings yet

- How To Write A Proficiency Badge Notebook?Document7 pagesHow To Write A Proficiency Badge Notebook?Makvana MehulkumarNo ratings yet

- Traditional Healers in Johannesburg +27789571548 Sangoma - Traditional Healer in Johannesburg Cape Town DurbanDocument3 pagesTraditional Healers in Johannesburg +27789571548 Sangoma - Traditional Healer in Johannesburg Cape Town Durbanmoosa psychicNo ratings yet

- LogiQ Question Paper Round-3Document2 pagesLogiQ Question Paper Round-3N CH KRISHNA TEJANo ratings yet

- Kansas Secretary of State's Office LetterDocument4 pagesKansas Secretary of State's Office LetterThe Kansas City StarNo ratings yet

- Mayor Support LetterDocument1 pageMayor Support Letterheather valenzuelaNo ratings yet

- Instructions To Candidates For Notification No.3 of 2024 dt.15.01.2024 in ENGLISH & TAMILDocument44 pagesInstructions To Candidates For Notification No.3 of 2024 dt.15.01.2024 in ENGLISH & TAMILhasan.mohamed2305No ratings yet

- Anti Defection LawDocument16 pagesAnti Defection LawLatest Laws Team100% (1)