Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

Uploaded by

yossi.marrujOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

Uploaded by

yossi.marrujCopyright:

Available Formats

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

Tom Beaumont James

The Oxford Handbook of Later Medieval Archaeology in Britain

Edited by Christopher Gerrard and Alejandra Gutiérrez

Print Publication Date: Jan 2018

Subject: Archaeology, Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

Online Publication Date: Feb 2018 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198744719.013.18

Abstract and Keywords

This chapter revises the concept of ‘palaces’ as residences, their uses and evolution,

stressing the role that archaeology can play in their understanding and study. Royal

palaces in rural settings are associated with specialized landscapes and generate a dis

tinctive archaeology because of their intermittent use and purpose; medieval kings and

their queens could be exceptionally mobile and households left little behind. Elements of

European design, some of which are considered here, could be influential and architec

tural practice was often in the vanguard of fashionable taste. Personal taste too played its

part but by the mid-fifteenth century the more remote residences were less visited, while

the sixteenth century brought new residences into royal hands. Current projects and

themes are all outlined as well as threats to sites and standing buildings.

Keywords: royal residences, episcopal palaces, parks, Westminster Palace, royal material culture

THE concept of the palace in later medieval Britain derived from various origins: the

houses on the Palatine Hill in Rome, Anglo-Saxon royal houses such as Cheddar in Somer

set (excavated by Philip Rahtz in the 1960s; Rahtz 1979), and Yeavering in Northumber

land (excavated by Brian Hope-Taylor in the 1950s; Hope-Taylor 1977). These last two

were royal sites for pre-Conquest dynasties in different parts of Britain. By the time these

kingdoms were united under the Normans, the royal family had a base at Westminster,

outside the walls of the city of London, squeezed between the abbey and the Thames on a

rather indifferent site. In order to control its large and diverse population, the Tower of

London was built before 1100 and its orientation leaves no doubt as to its purpose: it oc

cupies the south-east corner of the walled area and confronts the city. Apart from its ex

ceptional size, the arrangement of the Tower, with its main royal accommodation on the

upper storey, speaks volumes not only for the vigour of the Norman kings, but also their

skill with fortifications, their ambition in controlling the London metropolis, and their for

ward-looking architecture with its wall-fireplaces for added comfort (Ashbee 2006; Harris

2016; Hiller and Keevill 1995; Impey 2008; Keevill 2004; Parnell 1977; 2013; Thurley

1995; 1993).

Page 1 of 16

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Durham University; date: 10 September 2020

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

These two structures, the palace of Westminster and the Tower of London, epitomize the

two types of palatial residence occupied by royalty by 1100: the undefended palace and

the castle-palace. Other royal palaces and castle-palaces included more rural retreats

such as Clarendon in Wiltshire and Woodstock in Oxfordshire, both undefended resi

dences in the grand villa rustica style. The other great castle-palace which developed in

the period 1100–1540 was Windsor in Berkshire (Thurley 1993).

In addition there were episcopal palaces. The collapse of the western Roman Empire from

the early fifth century, and the subsequent colonization by Islam from the seventh century

of most of the Christian centres of the eastern Mediterranean and north Africa height

ened the focus on Rome, the centre of the western church. This political weakness in

western Europe propelled bishops into the role of managing large areas of (p. 372) the

Christian west in collaboration with local leaders. For this reason, and in contrast to the

episcopate in the eastern Church, western bishops found themselves working closely with

local rulers. In the Winchester diocese, for example, the kings of Wessex endowed the

bishopric with sufficient land to render it the wealthiest seen north of the Alps long be

fore 1100. Church and state at the highest level of society were very closely connected. In

turn, such enormous landholdings enabled bishops to create luxurious residences funded

by the income from their many manors (Rollason 2017). Their principal Winchester resi

dence, the mighty Romanesque structure called Wolvesey, was described in the twelfth

century variously as a domus quasi palatium, an element within de Blois’s wider scheme

of palatia sumptuosissima. Wolvesey was extensively, if partially, excavated and recorded

by Martin Biddle in the 1960s but remains unpublished (see, for example, Biddle 1970).

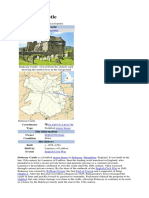

Lyddington Bede House (Figure 24.1) was originally a medieval wing of a palace of the

bishops of Lincoln. Like many palaces it later changed its use and was converted into an

almshouse by the end of the sixteenth century.

Figure 24.1 Lyddington Bede House in Leicester

shire, part of a medieval bishop’s palace, probably

private chambers with extensive buried remains

which would once have enclosed an open courtyard

(© Paul Stamper)

Page 2 of 16

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Durham University; date: 10 September 2020

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

Royal houses were associated with specialized landscapes which were in place by 1100.

In France for example, the Capetian kings settled on Paris as their capital because of the

quality of the hunting grounds nearby; at a later date kings of Scotland were to select

Falkland (Fife) for similar reasons. William the Conqueror had been described as loving

deer as if they were his children (in any case the deer were more pleasant than his chil

dren). His son Henry I (1100–35) was a keen hunter, creator of parks, and a keeper

(p. 373) of wild animals including camels, lynx, and porcupine in his park at Woodstock

(Bond 1987; for buildings here and elsewhere, see Brown et al. 1963; for lions at the Tow

er of London, see Keevill 2000 and O’Regan et al. 2006). Deerparks were associated both

with royal houses and palaces and also with episcopal houses and palaces. Some resi

dences were moated, such as Writtle, a hunting lodge in Essex associated with King John

(Rahtz 1969) and equipped with fashionable and labour-intensive fishponds, or Wells, the

episcopal residence in Somerset constructed for the bishops of the diocese of Bath and

Wells (Dunning 2010).

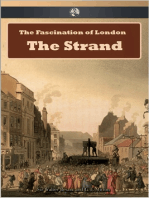

The use of palaces by royalty, and to a lesser extent by the archiepiscopate and episco

pate, was intermittent (Figure 24.2). Some kings were more mobile than others. The early

Norman kings of England, William I (1066–89) and William II (1089–1100), began over

size, ‘colonial’ building schemes such as the Tower of London, Winchester Cathedral with

its giant nave and westworks designed to be used for crown-wearing ceremony, and West

minster great hall, the largest of its kind in Europe (Courtney and Mark 1987). It may be

argued that similar grand landscape schemes, such as the walled park at Woodstock,

where the buildings were lost in the early eighteenth century and thus are recorded now

only in antiquarian accounts, and the exceptionally sized park at Clarendon, were prod

ucts of the same, ‘colonial’ regimes (Richardson 2005). Keen to impress and overawe the

local population, schemes such as these were created with funds seized from the previous

regime.

Norman rulers controlled large parts of Europe from Sicily to northern Europe to Eng

land in the eleventh to thirteenth centuries. This produced cross-fertilization of design—

for example the introduction of the donjon keep into England from Normandy, while the

introduction of fallow deer and park culture flowed northwards from Sicily to England,

whence fallow deer culture was exported to Normandy, for example (Sykes 2004). Occa

sionally elements of southern European palace design, e.g. interconnecting pools such as

those found at Palermo (Sicily) and later at the Alhambra (Granada, Spain), found their

way into England, for example into Everswell in Woodstock Park, the bijou residence cre

ated in the royal park by Henry II for his young mistress Rosamund Clifford in the late

twelfth century (Bond 1987, 46). This structure echoed contemporary literature, the tale

of Tristan and Isolde, popular at that time, where an enclosed residence for Isolde neces

sitated the passing of notes via waterways. There was, no doubt, a pan-European interest

among elites in aspects of these structures. Henry of Blois, brother of King Stephen

(1135–54) and the most likely candidate for extensive building work at Guildford Castle,

Surrey, was well known for his use of imported ancient Classical spolia to his episcopal

palace at Wolvesey in Winchester, while his dazzling Winchester Bible of c.1160 illus

Page 3 of 16

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Durham University; date: 10 September 2020

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

trates Romanesque interiors, roofs, decorative schemes, palace life, and furnishings

(Donovan 1993).

By 1200 much Romanesque palace building was completed under the Norman and

Angevin kings, especially during the long reigns of Henry I (1100–35, the remains of his

Romanesque Great Hall at Woodstock being recorded by John Aubrey before 1700) and

Henry II (1154–89). John’s busy itineraries led to the creation of many facilities appropri

ate for the arrival of royal retinues at short notice, such as the kitchen arrangements at

(p. 374) (p. 375) the royal castle of Marlborough in Wiltshire (not excavated but for a plan,

see Brentnall 1938), where hearths were capable of roasting two oxen at once. However

costly these building works might be, they were dwarfed by other expenses such as the

furnishings recorded in the Exchequer Rolls which begin in regular series from 1154. The

earliest English royal household account of 1207 shows that the greatest expense in royal

travel was the fodder for the horses rather than the food and drink for the court trav

ellers (Woolgar 1999). Hunting parks such as Clarendon, Woodstock, and elsewhere were

used seasonally by the kings according to set patterns of the hunting year, supply and

availability of sport, and so on. In the thirteenth century some evidence shows that kings

such as Henry III visited the park at Clarendon during the doe hunting season (today 1

November to 29 April), the buck hunting season was earlier, more of a summer activity

and that is when we find Edward II—who is documented engaged in hunting there in

1326—and Edward III at Clarendon (Richardson 2005). These palaces within their parks

were undefended sites in rural areas, the rural counterparts of Westminster, and with

their extensive paling fences and embankments have been described as ‘castles for deer’.

Figure 24.2 A map of royal palaces during the Mid

dle Ages

(© Alejandra Gutiérrez)

Page 4 of 16

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Durham University; date: 10 September 2020

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

One of the reasons for King John’s (1199–1216) unpopularity in England was that he was

exceptionally mobile. He was never in the same place for more than a month in his seven

teen-and-a-half year reign. This has resulted in a plethora of sites being dubbed ‘King

John’s’ house or palace and he no doubt visited many of them (e.g. Rahtz 1969). Many of

his subjects’ communities had not been visited by royalty for generations, if ever, al

though it remains a moot point as to whether the king was welcomed by all, as the deba

cle of Magna Carta and the civil war of 1215–16 was to demonstrate. The lifestyle of John

was mirrored by his Welsh counterparts, who were likewise itinerant and who also trav

elled to royal and other sites during progresses, stopping for example at Rhuddlan or De

gannwy, Gwynedd, to do business, justice, and ‘to eat [their] way through’ taxes (Pound

1994). This was a lifestyle readily recognizable in England and Scotland in the Middle

Ages among royalty, prelates, and nobility, but which in Wales came to an end for their

kings with the conquest of Wales in 1283 and subsequent attempts from a string of com

fortable royal castles in North Wales to pacify the principality. Geophysical work at the

end of the last century identified some of these llys or royal complexes of the Welsh kings

(Smith 2014).

Then as now, fashions changed, and royalty often led the way, or at least picked the best

of what they saw others doing. Thus, when Romanesque architecture with its solid,

rounded arches, gave way to the pointed architecture of the Gothic, royalty were among

the leaders of this fashion. Louis IX of France (1226–70) inspired his brother-in-law Henry

III of England (1216–72) to become a ‘champion of the Gothic’. Various claims have been

made and disputed about the influence of Arab architecture on the transition from Ro

manesque to Gothic arising from contacts made during the crusades which began in

1095. What is more certain is the spread of Christian material culture from Byzantium af

ter the fourth crusade of 1207 when many relics were looted by the western European

crusaders who sacked the ancient capital of the eastern church. Of these relics, the

Crown of Thorns from Christ’s passion was the most prized. This led to the establishment

of a series of chapels of l’epine across France as individual thorns were disposed of

(p. 376) by the king. The most significant of these repositories in the Gothic style was the

Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, with is full-size reliquary design both exterior and interior (Co

hen 2008). Chapels similar in design, tall and narrow, were built across Europe from the

middle of the thirteenth century, for example in London and at Clarendon in Wiltshire.

Among the European building stock, three from France might be highlighted. The first, at

Perpignan, was begun c.1270 for the kings of Majorca and incorporated Islamic influ

ences (Passarius and Catafau 2014). The second, at Hesdin (Artois), was created c.1295

as a palatial pleasure garden over 940 hectares enclosed by a wall 13 km in length; it was

intended as a Garden of Eden complete with various machines which dispensed water,

feathers, and soot and further amused (or confused) visitors with mirrors (Van Buren

1986). Hesdin may have been the inspiration, after a visit in 1313, for Edward II to lavish

attention on enlarging his own parks. But if Hesdin was an inspirational garden, the

greatest palace in the early fourteenth century was the massive Palace of the Popes at

Avignon, built during the exile of the papacy from Rome between the early and mid-four

teenth century (Renoux 1994). Claimed as the largest Gothic building in Europe, the cam

Page 5 of 16

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Durham University; date: 10 September 2020

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

paigns of Benedict XII (1334–42) and subsequently Clement VI (1346–56) were outstand

ing, the buildings combining the grandeur of French Gothic with decorative schemes by

Italian craftsmen.

During the fourteenth century, war between France and England, insecurities of succes

sion in the Capetian family, and dispossession of monarchs in England such as Edward II

(1327) and Richard II (1399) all inhibited grand palace development, although Richard

did create small-scale building-jewels, such as his palatial accommodation on the south

coast at Portchester, Hampshire (Cunliffe 1977; 1985), and his island retreat (now entire

ly lost) at ‘La Nayght’ on the Thames at Surbiton, Surrey. He is recorded as adding ‘danc

ing rooms’ at various palaces across England. Notably, he razed the palace at Sheen, Sur

rey, to the ground following the death there of his wife Anne of Bohemia in 1392. Howev

er, by far the greatest achievements in palace building in England were a result of the

coming together of the necessary leadership (for example by William of Wykeham and

William Wynford) and the required financial resources which arose from the capture and

ransom of John II of France at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356. This enabled the completion

of outstanding works such as the chapel of St Stephen at Westminster (traditionally be

gun in the reign of King Stephen, d. 1154) which was achieved despite the shortage of

labour and skills following the Black Death of 1348–50. Greater still was the work carried

through after 1356 at Windsor castle-palace where the Norman keep was upgraded and

reroofed, and the unusual ‘Round Table’ building of 1344, based on a Mediterranean pro

totype, was dismantled and replaced by a major building scheme in the upper bailey con

sisting of an end-on hall and chapel under a single roof-ridge, accommodation for retain

ers, upgraded kitchens etc., all of this on a grand scale (Tatton-Brown 2010).

Agency of popes, royalty, their relations, and leading staff, such as Wykeham (in the

1350s) and other prelates, is key in these works. As Edward III declined militarily, physi

cally, and financially (ransom monies stopped with the death of King John II in 1364), roy

al building slowed although the heir to the throne, Edward the Black Prince, (p. 377) up

graded and modernized his palatial residence at Kennington, in London south of the

Thames. Both Edwards were dead by the end of 1377. The significant decline in royal and

episcopal incomes following the Black Death put a brake on the more grandiose schemes.

In England the change from richly carved, labour-intensive, decorated architecture to the

regional mass-produced conformity of the Perpendicular style illustrates the changing cir

cumstances very well. Continuing international and civil wars in Europe drained re

sources, with a kaleidoscope of changing fortunes and monarchs, as France recovered to

wards the mid-fifteenth century, so England fell into disarray.

In common with his predecessor Richard II, Henry V (1412–22) took special delight in

small private and secluded sites, such as the moated ‘Pleasaunce’ at Kenilworth Castle in

Warwickshire, across the lake from the main magnate residence (Jamieson and Lane

2015). But he also drove forward grand schemes such as the reconstruction of a resi

dence at Sheen adorned with antelope images on the roof. All this was in stark contrast to

Henry VI, who was not renowned as a builder of palaces (although his colleges at Eton,

Berkshire, and at King’s in Cambridge were, so far as they went, significant architectural

Page 6 of 16

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Durham University; date: 10 September 2020

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

achievements, left incomplete at his death). Meanwhile in Scotland, James I (1406–37),

after eighteen years of captivity in England, returned to Scotland in 1424 to a small

group of residences or palaces, notably Edinburgh and Stirling castles and Linlithgow

palace. Kings of an earlier era had been crowned at Scone Palace, Perthshire, an abbey

and abbatial palace adjacent to Perth on the Tay. Scone had long been a key site in Scot

tish royal ceremony and remained so until dissolved as a monastery in 1559, analogous

arguably to Westminster Abbey and Palace near London (Dunbar 1999). Perhaps the

greatest extent of Scottish royal residences developed under James V (1514–42) with the

capable assistance of his advisers for he came to the throne aged only 1 year old. The roy

al property portfolio of residences expanded into Angus and the lordship of Glamis at

which point in the mid-sixteenth century he laid claim to some thirty-six properties which

could be drawn upon during his itineraries.

With the deposition of Henry VI and his untimely death in 1471, the Yorkist kings drew in

their ambitions for widespread travel and reduced use of the more remote residences

such as the most westerly at Clarendon, where Henry VI had suffered the first onset of

his mental collapse in 1453. So although ovens there were kept up as late as 1485 against

the visit of the ‘northern’ King Richard III, there is no evidence that he or his Tudor suc

cessors visited the palace as a residence although Henry VII, Henry VIII, and Elizabeth

used the park (Beaumont James and Gerrard 2007). Under Henry VIII (1509–47), howev

er, matters were to alter substantially so far as palaces were concerned. What first

changed the scene was the king’s falling out with his senior churchmen which brought

new palaces into royal hands. Among these were Cardinal Wolsey’s Hampton Court in

1529 and York Palace (Whitehall), as well as a range of other episcopal and archiepisco

pal residences such as Mayfield in Sussex and Oatlands in Kent. Second, when this king

entered into his dispute with the monasteries, their dissolution provided further opportu

nities for palatial royal endeavours, for example the conversion of part of the enormous St

Augustine’s Abbey in Canterbury, Kent, dissolved in 1538, to a royal (p. 378) residence

used for example by the new Queen Anne of Cleves as she made her way to London in

1540.

Undoubtedly the major achievement in palace building in the final phase of the period to

1540 was the creation of the eponymous Nonsuch Palace, Surrey (Biddle 2005), following

the birth of Prince Edward in 1537. Here the king drew on French and Italian craftsmen;

the materials, moulded plaster with gilded slate covering over an oak frame, were unique

in England, and not well suited to the climate. What is apparent from the layout and the

plans of Nonsuch, and other royal residences of the same period, is that in many respects

they followed the ancient gendered plans of apartments for the king, apartments for the

queen. When compared to the Tower of London of the Normans, Angevin, or Plantagenet

palaces—or indeed to palaces in use today for that matter—the royal apartments and per

sons were deeply hidden (Richardson 2003; see Chapter 50 in this Handbook). Work on

queens’ accommodation, palaces, and landholdings is one area awaiting closer scrutiny.

Page 7 of 16

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Durham University; date: 10 September 2020

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

Archaeology and Complementary Sources for

Palaces

For England the greatest royal palace was undoubtedly Westminster which lies beyond

the walled area of the City of London. The Westminster complex of buildings, which in

cludes the royal abbey, is most certainly the most significant source of evidence for the

medieval palace and for royal-ecclesiastical links, the abbey being the coronation church

of the kings with its late medieval coronation chair and its unique survivals of architectur

al style and decorative schemes including the late thirteenth-century Cosmati pavements

(see cover), polychromy, and sculpture. Westminster boasts fossilized fragments of decor

which have vanished almost everywhere else. Although St Stephen’s chapel at the palace

has gone, the Chapel of the Pew in the Abbey contains in microcosm much detail which

matches records of what was once to be seen at St Stephen’s, from doorway to vaulting

and architectural detail of the 1370s (Spooner 2015).

Much of the medieval palace at Westminster was destroyed in the fire of 1834 but the

great hall of William II (Rufus) survives (Figure 24.3). Recent work argues for a remark

able panelled ceiling to the eleventh-century hall, so that it was never an aisled hall (Har

ris and Miles 2015). The 600-tonne hammer beam roof of the 1390s stands today as a

monument to the technical, lapidary, engineering, and craft skills of that era (Munby

2015). While archaeology is of great value, much of the historic palace has disappeared

over the centuries, not least in the fire of 1263. Changes, upgradings, and demolitions in

the early nineteenth century (for example of the queen’s apartments and her chapel)

were recorded by antiquarians and others, and they have provided, for example, a record

of the thirteenth-century Painted Chamber before its murals were wallpapered over.

These remarkable watercolour records by artists such as Capon and Stothard are (p. 379)

invaluable for understanding the later medieval structures and their décor (Emery 2006,

258). The fire of 1834 also cleared accretions to some buildings leaving, for example, the

outer walls of St Stephen’s Chapel, which had been used since the Reformation as the

parliament chamber (medieval parliaments having met in such spaces as the Chapter

House of the adjacent abbey). The reconstruction of the parliament debating space by

Barry post-1834 as a reproduction of the north and south confronting medieval canons’

stalls has been argued to have continued the tradition of adversarial English politics en

couraged by the re-use of the facing stalls of the former canons, established by Edward

III (d. 1377) (Rodwell 2015).

Page 8 of 16

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Durham University; date: 10 September 2020

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

Figure 24.3 Westminster palace and abbey, as de

picted by Wenceslaus Hollar in 1647 (Thomas Fisher

Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, public do

main)

Because of its scale, the ongoing use of Westminster as a centre of national government,

the needs for security, and the challenge of making the medieval abbey partly available to

interested members of the public through use of a ‘trail’, the detailed study of the struc

ture is currently very difficult. In addition, there were many later changes when the ma

jor medieval structures continued to be used not only for parliaments and royal religious

observance but also for key political events, such as the trial and condemnation of

Charles I (d. 1649) and also as the home for many centuries to the courts of Common

Pleas and King’s Bench, both sited also within the Great Hall. All this contributes to an

explanation as to why this supremely important complex has not been studied in its me

dieval incarnations as it should have been. Nevertheless, of particular interest at West

minster is the wide range of pigments and paintings which have survived from the period

c.1250 to 1350. Reds (including lac lake and vermilion), copper greens (verdigris and

malachite), yellows (e.g. orpiment in imitation of gold leaf), indigo, and many combina

tions of these pigments with white, black, and other colourings and drawing media all

survive in the decoration at the Abbey (Howard and Sauerberg 2015). For example, the

scheme of vices and virtues in the window reveals of the Painted Chamber and recorded

in watercolour before their destruction would, (p. 380) like the furnishings in the abbey,

have been decorated with inlaid stones or jewels and with raised tinwork decorative

schemes. These echo royal commissions elsewhere such as at Clarendon palace where

fragments of azurite and ultramarine (lapis lazuli) have been recovered, as has minium

(red lead) foundation painting on stone fragments together with evidence for the gilding

of stonework and statuary (Beaumont James and Gerrard 2007, 78). Surviving pieces of

furniture, royally embellished such as the coronation chair of the late thirteenth century

and the altar retable both also in Westminster Abbey, illustrate just how lavish such fur

nishing could be. The so-called Wilton Diptych of the late fourteenth century also once

stood in the Chapel of our Lady of the Pew while Richard II (d. 1399) revered it (Spooner

2015). This astonishing survival would have travelled with the king and have been set up

in the now lost palaces round the country, such as Woodstock and Clarendon, where the

kings had a special shelf for their travelling relics.

Page 9 of 16

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Durham University; date: 10 September 2020

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

Archaeology shows on the one hand how little royal material culture remained in palaces

unless it was broken on site and dumped. Among the fragments which survive is a re

markable travelling chest from Knaresborough Castle in Yorkshire, once the possession of

Queen Philippa of Hainault (d. 1369). Muniment chests found today at the Public Record

Office also date from the medieval period (Steane 1993, 127); in situ storage arrange

ments for records can be found in William of Wykeham’s colleges in Oxford and in Win

chester. Elsewhere, surviving decorative schemes include tiles from Chertsey, Surrey,

which probably started out in Westminster before being passed on to the abbey and the

fine thirteenth-century palace floors from Clarendon which are now on display in the

British Museum (Figure 24.4), while part of the tile kiln in which they were made can be

seen at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. The pre-1250 circular pavement from

Clarendon is exceptional both in survival and more significantly in the apparently excep

tional skill of the English tilers who made it (Beaumont James and Gerrard 2007, 82–3).

Also from Clarendon are a handful of lead stars, linked to documentary references to scin

tillis noted in documentation of Henry III’s reign.

Royalty, bishops, and nobility were peripatetic and carried all kinds of supplies from site

to site. Bishop Swinfield of Hereford, travelling from his westerly diocese to his London

house, suffered a disaster when a cart capsized and severely damaged the ceramics he

was transporting to the capital for his use. When the wagon train halted, potters were

found then and there to replace the damaged items. Foodstuffs too were required in

quantity. Food remains such as crab-carapaces were recovered from Kings Langley in

Hertfordshire, and from Clarendon there was a wide range of deer, as well as cod, conger

eel, ray, and wrasse from deep sea fishing and coastal-raised oysters. Documentary

sources show how fresh-water fish were transported to royal and episcopal sites (Dyer

2000, 107), in the case of the bishops of Winchester’s palace at Wolvesey for example, all

the way from Somerset in damp sacks for a feast attended by Richard II in 1393. Several

kitchens and their waste have been investigated archaeologically, including those at

Windsor Castle and Clarendon, while a standing medieval episcopal kitchen complete

with its roof is to be found at the bishop’s palace at Chichester (Sussex), with remains of

a (p. 381) (p. 382) later structure in the adjoining diocese of Winchester at Bishops

Waltham, although no below ground archaeology has been undertaken at either location

(Hare 1988).

Page 10 of 16

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Durham University; date: 10 September 2020

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

Figure 24.4 A reconstruction of the thirteenth-centu

ry palace floor from the king’s apartments at Claren

don Palace, Wiltshire, together with other floor tiles

from other areas of the same site

(© Alejandra Gutiérrez)

Current Work

As a result of work by John Steane (1993; 2001) on the archaeology of the monarchy and

symbols of power, recent national syntheses (Dunbar 1999; James 1990; Keevill 2000;

Thurley 1993) and case studies (e.g. Beaumont James and Gerrard 2007 for Clarendon;

Gilchrist 2005 for Norwich Cathedral close; Payne 2003 for the palaces of the Bishops of

Bath and Wells; White and Cook 2015 for Sherborne Old Castle and the Bishops of Salis

bury), medieval palaces are now emerging once again as a field of study and there is

much to look forward to. The themes outlined by Creighton (Chapter 23) stand equally

well for palaces. A selection of projects underway might include a major scheme to recov

er a detailed plan of the palace of Westminster (under preparation at the University of

York) or landscape research at King’s Norton in Leicestershire, led by James Wright of

the Museum of London. A final report of the ‘spoilheap’ archaeology at Clarendon Palace

undertaken while the site was being rescued from the overgrowth and undergoing emer

gency consolidation, is also in preparation. In Scotland a survey of deerparks is being car

ried out by Derek Hall at Buzzart Dykes, Perthshire, and elsewhere while Penny Dransart

has run a long series of excavations at the bishop’s palace at Fetternear, Aberdeenshire.

Medieval palace studies are in search of champions for the new millennium and a major

international conference on medieval palaces at Bishop Auckland (Co. Durham) in 2015,

where excavations are underway in advance of a new museum within the episcopal

palace complex, set a new agenda (Rollason 2017).

Page 11 of 16

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Durham University; date: 10 September 2020

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

Threats continue. In 1972 the disastrous creation of the underground carpark at West

minster destroyed much archaeology there without any recording (Gerrard 2003, 134).

Fragile structures such as the remains at Clarendon are once again heading towards Her

itage England’s Buildings at Risk Register. However, new ideas are being posited about

the arrangement and sequencing of palace buildings nationally, heavily but almost entire

ly unscientifically excavated at different periods from the eighteenth to the twentieth cen

turies. Keyhole sites at Tudor palaces in London have brought much to light in recent

years, but are of necessity small-scale. So far as rural palace sites are concerned, new

sites are under investigation. Current work at Kings Clipstone (Nottinghamshire) led by

Andy Gaunt (Mercian Archaeological Services) and James Wright (Museum of London Ar

chaeology) have involved standing remains survey, landscape work, and geophysical sur

vey, similarly to community excavations at Woking Palace, Surrey (ongoing Heritage Lot

tery Fund project). A plan of ‘John of Gaunt’s’ palace at King’s Somborne (Hampshire)

was recovered some years ago while outlines of what appears to be a Romanesque palace

hall and other buildings have likewise shown up dramatically in recent work at Old Sarum

by the University of Southampton. There is much to be done, not least considered excava

tion using modern (p. 383) methods at sites where the surface has only been scraped, at

such sites as Clarendon, Kings Clipstone, and Woodstock. Such work promises to trans

form our understanding of the archaeology, architecture, and ecology through properly

dated sequences. The combination of detailed documentary study in close relation to

physical archaeology and architectural study of these uniquely recorded sites is essential.

Among recent developments have been reconstructions of medieval décor of the twelfth

century (Dover Castle, Kent), thirteenth century (Tower of London, now largely replaced),

and the thirty-five-year programme of reconstruction on the Great Hall of Stirling Castle

including the manufacture of a medieval-style roof of c.1500 to recreate the hall of James

IV of 1503 with some furnishings. Such schemes are sometimes problematic and contro

versial, but they are intended to breathe life back into buildings which have not seen roy

al residents for many centuries.

References cited

Ashbee, J. A. 2006 The Tower of London as a royal residence: 1066–1400, unpublished

PhD thesis, University of London

Beaumont James, T. and Gerrard, C. M. 2007 Clarendon: landscape of kings, Windgather,

Macclesfield

Biddle, M. 1970 ‘Excavations at Winchester, 1969: eighth interim report’, The Antiquaries

Journal 50, 277–326

Biddle, M. 2005 Nonsuch Palace, Oxbow, Oxford

Bond, C. J. 1987 ‘Woodstock Park in the Middle Ages’, in J. Bond and K. Tiller (eds),

Blenheim: landscape for a palace, Sutton, Gloucester, 22–54

Page 12 of 16

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Durham University; date: 10 September 2020

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

Brentnall, H. C. 1938 ‘Marlborough Castle’, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History

Magazine 48, 133–43

Brown, R. A., Colvin, H. M., and Taylor, A. J. 1963 The history of the King’s works, vol. 2:

the Middle Ages, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London

Cohen, M. 2008 ‘An indulgence for the visitor: the public at the Sainte-Chapelle of Paris’,

Speculum 83, 840–83

Courtney, L. T. and Mark, R. 1987 ‘The Westminster Hall roof: a historiographical and

structural study’, The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 30, 374–93

Cunliffe, B. W. 1977 Excavations at Portchester Castle vol. 3: medieval, the outer bailey

and its defenses, The Society of Antiquaries of London, London

Cunliffe, B. W. 1985 Excavations at Portchester Castle vol. 4: medieval and inner bailey,

The Society of Antiquaries of London, London

Donovan, C. 1993 The Winchester Bible, The British Library, London

Dunbar, J. G. 1999 Scottish Royal Palaces: the architecture of the royal residences during

the late Medieval and early modern periods, Tuckwell Press, East Linton

Dunning, R. 2010 Jocelin of Wells: bishop, builder, courtier, Boydell Press, Woodbridge

Dyer, C. 2000 Everyday life in medieval England, Hambledon and London, London

Emery, A. 2006 Greater medieval houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: Vol. 3, south

ern England, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Gerrard, C. M. 2003 Medieval archaeology: understanding traditions and contemporary

approaches, Routledge, London

Gilchrist, R. 2005 Norwich Cathedral Close: the evolution of the English cathedral

(p. 384)

landscape, Boydell, Woodbridge

Hare, J. N. 1988 ‘Bishop’s Waltham Palace, Hampshire: William of Wykeham, Henry Beau

fort and the transformation of a medieval episcopal palace’, The Archaeological Journal

145, 222–54

Harris, R. B. 2016 ‘Recent research on the White Tower: reconstructing and dating the

Norman building’, in J. A. Davies, A. Riley, J.-M. Levesque, and C. Lapiche (eds), Castles

and the Anglo-Norman World, Oxbow Books, Oxford, 177–89

Harris, S. and Miles, D. 2015 ‘Romanesque Westminster Hall and its roof’, in W. Rodwell

and T. W. T. Tatton-Brown (eds), Westminster: the art, architecture and archaeology of the

royal palace and abbey, Part 2, British Archaeological Association Conference Transac

tions volume 39, Leeds, 22–71

Page 13 of 16

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Durham University; date: 10 September 2020

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

Hiller, J. and Keevill, G. D. 1995 ‘Recent archaeological work at the Tower of London’,

Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society 45, 147–81

Hope-Taylor, B. 1977 Yeavering: an Anglo-British centre of early Northmbria, Her

Majesty’s Stationery Office, London

Howard, H. and Sauerberg, M. L. 2015 ‘The polychromy at Westminster Abbey, 1250–

1350’, in W. Rodwell and T. W. T. Tatton-Brown (eds), Westminster: the art, architecture

and archaeology of the royal palace and abbey, Part 1, British Archaeological Association

Conference Transactions volume 39, Leeds, 205–61

Impey, E. (ed.) 2008 The White Tower, Yale University Press, London and New Haven

Jansen, V. 2015 ‘Henry III’s palace at Westminster’, in W. Rodwell and T. W. T. Tatton-

Brown (eds), Westminster: the art, architecture and archaeology of the royal palace and

abbey, Part 2, British Archaeological Association Conference Transactions volume 39,

Leeds, 89–110

James, T. B. 1990 The palaces of medieval England, c.1050–1550: royalty, nobility, the

episcopate and their residences from Edward the Confessor to Henry VIII, Seaby, London

Jamieson, E. and Lane, R. 2015 ‘Monuments, mobility and medieval perceptions of de

signed landscapes: the Pleasance, Kenilworth’, Medieval Archaeology 59(1), 255–71

Keevill, G. D. 2000 Medieval palaces: an archaeology, Tempus, Stroud

Keevill, G. D. 2004 The Tower of London moat: archaeological excavations 1995–9, Oxford

Archaeology, Historic Royal Palaces Monograph 1, Oxford

Munby, J. 2015 ‘Late-14th-century reconstruction of Westminster Hall’, in W. Rodwell and

T. W. T. Tatton-Brown (eds), Westminster: the art, architecture and archaeology of the roy

al palace and abbey, Part 2, British Archaeological Association Conference Transactions

volume 39, Leeds, 120–32

O’Regan, H., Turner, A., and Sabin, R. 2006 ‘Medieval big cat remains from the Royal

Menagerie at the Tower of London’, International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 16, 385–94

Parnell, G. 1977 ‘Excavations at the Tower of London’, London Archaeologist 3(4), 97–9

Parnell, G. 2013 ‘The Great Hall in the inmost ward, Tower of London’, London Archaeolo

gist 13(8), 211–14

Payne, N. 2003 The medieval residences of the bishops of Bath and Wells, and Salisbury,

unpublished PhD, University of Bristol

Passarius, O. and Catafau, A. (eds) 2014 Un palais dans le ville, vol. 1. Les Palais des Rois

de Majorque à Perpignan, Trabucaire, Canet en Roussillon

Page 14 of 16

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Durham University; date: 10 September 2020

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

Pound, N. J. G. 1994 The medieval castle in England and Wales: a political and social his

tory, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Rahtz, P. A. 1969Excavations at King John’s hunting lodge, Writtle, Essex, 1955–

(p. 385)

57, The Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph 3, London

Rahtz, P. A. 1979 The Saxon and Medieval Palaces at Cheddar, British Archaeological Re

ports British Series 65, Oxford

Renoux, A. (ed.) 1994 Palais médiévaux (France-Belgique): 25 ans d’archéologie, Univer

sité du Maine, Le Mans

Richardson, A. 2003 ‘Gender and space in English royal palaces c.1160–c.1547: a study in

access analysis and imagery’, Medieval Archaeology 47, 131–65

Richardson, A. 2005 The forest, park and palace of Clarendon, c.1200–c.1650: recon

structing an actual, conceptual and documented Wiltshire landscape, British Archaeologi

cal Reports British Series 387, Oxford

Rodwell, W. 2015 ‘The archaeology of Westminster Abbey: and historiographical

overview’, in W. Rodwell and T. W. T. Tatton-Brown (eds), Westminster: the art, architec

ture and archaeology of the royal palace and abbey, Part 1, British Archaeological Associ

ation Conference Transactions volume 39, Leeds, 34–60

Rollason, D. (ed.) 2017 Princes of the Church: bishops and their palaces, The Society for

Medieval Archaeology Monograph 39, Abingdon

Smith, S. G. 2014 ‘Parks and designed landscapes in medieval Wales’, in K. Baker, R. Car

den, and R. Madgwick (eds), Deer and people, Oxbow, Oxford, 231–9

Spooner, J. 2015 ‘The Virgin Mary and white harts great and small: the 14th-century wall-

paintings in the Chapel of Our Lady of the Pew and the muniment room’, in W. Rodwell

and T. W. T. Tatton-Brown (eds), Westminster: the art, architecture and archaeology of the

royal palace and abbey, Part 1, British Archaeological Association Conference Transac

tions volume 39, Leeds, 262–90

Steane, J. M. 1993 The archaeology of the medieval English monarchy, Batsford, London

Steane, J. M. 2001 The Archaeology of power: England and Northern EuropeAD 800–

1600, Tempus Publishing, Stroud

Sykes, N. J. 2004 ‘The introduction of fallow deer to Britain: a zooarchaeological perspec

tive’, Environmental Archaeology 9, 75–83

Tatton-Brown, T. W. T. 2010 St George’s Chapel, Windsor: history and heritage, Dovecote

Press, Dorset

Thompson, M. 1998 Medieval bishops’ houses in England and Wales, Ashgate, Aldershot

Page 15 of 16

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Durham University; date: 10 September 2020

Medieval Palaces and Royal Houses

Thurley, S. 1993 The royal palaces of Tudor England: architecture and court life, 1460–

1547, Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, Yale University, New Haven

Thurley, S. 1995 ‘The Royal Lodgings at the Tower of London 1240–1320’, Architectural

History 38, 36–7

Van Buren, A. H. 1986 ‘Reality and literary romance in the park of Hesdin’, Medieval Gar

dens 127, 115–34

White, P. and Cook, A. 2015 Sherborne Old Castle, Dorset: archaeological investigations

1930–90, The Society of Antiquaries of London, London

Woolgar, C. M. 1999 The great household in late medieval England, Yale University Press,

New Haven

Tom Beaumont James

Tom Beaumont James is Professor Emeritus in Archaeology and History at Winches

ter University. His main areas of interest are medieval buildings, especially medieval

palaces, and also the Black Death of 1348–50, having written books on Clarendon

Park, Wiltshire, and Winchester, among others.

Page 16 of 16

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Durham University; date: 10 September 2020

You might also like

- A History of The Social Housing in The Castle Barracks DraftDocument14 pagesA History of The Social Housing in The Castle Barracks DraftSimon Spratt100% (2)

- Steven Holl Luminosity Porosity TextDocument14 pagesSteven Holl Luminosity Porosity Textmihailom91No ratings yet

- Londra Obiective TuristiceDocument21 pagesLondra Obiective TuristiceBadicioiu LaurentiuNo ratings yet

- Portrait of Britain AD 1000Document7 pagesPortrait of Britain AD 1000David BaymillerNo ratings yet

- A History of British ArchitectureDocument10 pagesA History of British ArchitectureCristina MelaniaNo ratings yet

- MansionDocument3 pagesMansionmegawhat115No ratings yet

- The History of Britain Traced Through The History of ArchitectureDocument3 pagesThe History of Britain Traced Through The History of ArchitectureАня РалеваNo ratings yet

- Architecture - Civilizatie BristanicaDocument4 pagesArchitecture - Civilizatie BristanicaCris Mari VernicaNo ratings yet

- Westminster Abbey: A King's Dream, A Nation's IconDocument27 pagesWestminster Abbey: A King's Dream, A Nation's Iconoldenglishblog100% (1)

- Ministerul Educației Și Cercetării Colegiul Național Mihai Viteazul" PloieștiDocument19 pagesMinisterul Educației Și Cercetării Colegiul Național Mihai Viteazul" PloieștiDaiana AndreeaNo ratings yet

- Text 1 - Class 1Document1 pageText 1 - Class 1Aline LourençoNo ratings yet

- Windsor Castle Modifica2Document1 pageWindsor Castle Modifica2tonymazzei24No ratings yet

- Windsor CastleDocument2 pagesWindsor CastleDavid DuezNo ratings yet

- Types of Houses in UKDocument24 pagesTypes of Houses in UKGeorge CosteaNo ratings yet

- William. King and ConquerorDocument359 pagesWilliam. King and ConquerorDamian HemmingsNo ratings yet

- Gap-Fill PracticeDocument6 pagesGap-Fill Practicengocquyquyngoc2906.qtmunNo ratings yet

- Hiller2019 Chapter Period1LondonBirthOfANewOrder1Document40 pagesHiller2019 Chapter Period1LondonBirthOfANewOrder1Fermilyn AdaisNo ratings yet

- Stokesay CastleDocument8 pagesStokesay CastleJonathan PendongNo ratings yet

- SouthernHist38 Book ReviewsDocument24 pagesSouthernHist38 Book ReviewsElton MedeirosNo ratings yet

- Marie Luise Gothein The History of Garden ArtDocument40 pagesMarie Luise Gothein The History of Garden ArtAlexandra PetcuNo ratings yet

- The Outrageous Beauty of MEDIEVAL CASTLES: PART I - A Brief History of Castle ArchitectureDocument41 pagesThe Outrageous Beauty of MEDIEVAL CASTLES: PART I - A Brief History of Castle Architecturefabrignani@yahoo.com100% (1)

- History of Great Britain (Part 1)Document13 pagesHistory of Great Britain (Part 1)Liza UstymenkoNo ratings yet

- Story Fulfil Function Commercial Symbol Factor Story Use Use Symbol Know Use Use Use Use Year KnowDocument2 pagesStory Fulfil Function Commercial Symbol Factor Story Use Use Symbol Know Use Use Use Use Year KnowЯрослав СтефановичNo ratings yet

- Referat Culture of EnglandDocument3 pagesReferat Culture of Englandanita_angel_91No ratings yet

- Patrimoine CulturelDocument5 pagesPatrimoine CulturelislemmonkiNo ratings yet

- The Saxon and Medieval Palaces of CheddarDocument12 pagesThe Saxon and Medieval Palaces of CheddarMiecławNo ratings yet

- ENDocument1 pageENreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Girls at WarDocument53 pagesGirls at Warwarda.kacemiNo ratings yet

- Architecture of Power in The UK. 2Document48 pagesArchitecture of Power in The UK. 2Iulia RaduNo ratings yet

- Prehistory in UkDocument12 pagesPrehistory in Ukthutra816No ratings yet

- Medieval TimesDocument26 pagesMedieval TimesBarbara AvilaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2Document8 pagesLecture 2Никита ФортунаNo ratings yet

- The Unification of EnglandDocument21 pagesThe Unification of EnglandHolda GómezNo ratings yet

- Atestat EnglezaDocument20 pagesAtestat EnglezaSamira PopNo ratings yet

- The Fall of Orthodox EnglandDocument101 pagesThe Fall of Orthodox EnglandAggelos-Olesya Kanakis100% (1)

- Garcia, Levin Liu, Liu Kin Malolos, John Reinard Tiu, JosephDocument38 pagesGarcia, Levin Liu, Liu Kin Malolos, John Reinard Tiu, JosephReg YuNo ratings yet

- Civilisation Britannique: Chapter 1: The Romans and The Anglo-SaxonDocument5 pagesCivilisation Britannique: Chapter 1: The Romans and The Anglo-SaxonAnaelle MeuricNo ratings yet

- Westminster AbbeyDocument25 pagesWestminster AbbeyBianca GureaNo ratings yet

- Edimburg HDocument20 pagesEdimburg HmariaNo ratings yet

- 21 Top Sites in London For History Lovers - Context TravelDocument1 page21 Top Sites in London For History Lovers - Context Travelzuzana777provazNo ratings yet

- The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 13, No. 365, April 11, 1829 by VariousDocument38 pagesThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 13, No. 365, April 11, 1829 by VariousGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Portfolio History UkDocument12 pagesPortfolio History Ukthutra816No ratings yet

- Westminster AbbeyDocument8 pagesWestminster AbbeyTyrantNo ratings yet

- Anglo-Saxon Literature: Instructor Ecaterina Hantiu PHDDocument53 pagesAnglo-Saxon Literature: Instructor Ecaterina Hantiu PHDHuha JuhaNo ratings yet

- 2Document2 pages2Ildiko PetiNo ratings yet

- Castle Builders: Approaches to Castle Design and Construction in the Middle AgesFrom EverandCastle Builders: Approaches to Castle Design and Construction in the Middle AgesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Most Visited Places in United Kingdom - : Lucrare Pentru Obtinerea Atestatului de Limba EnglezaDocument22 pagesMost Visited Places in United Kingdom - : Lucrare Pentru Obtinerea Atestatului de Limba EnglezaAndreeeaNo ratings yet

- Vernacular Houses in The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesVernacular Houses in The PhilippinesPat GeronzNo ratings yet

- Wall ShelfDocument4 pagesWall Shelfrayane ouzmihNo ratings yet

- Indo-Islamic Architecture (SALAHUDDIN)Document8 pagesIndo-Islamic Architecture (SALAHUDDIN)Muneeb BalouchNo ratings yet

- Rodded &loose Unit WeightDocument17 pagesRodded &loose Unit WeightAtm Tjah Radix LoegoeNo ratings yet

- Daniel Libeskind: Jewish Museum - BerlinDocument5 pagesDaniel Libeskind: Jewish Museum - Berlinbugoff700No ratings yet

- SCRIPT FOR DRAMA PLAY (Draft)Document6 pagesSCRIPT FOR DRAMA PLAY (Draft)Blue MixxyNo ratings yet

- Pre Spud Checklist 4Document2 pagesPre Spud Checklist 4Ali Alakari100% (1)

- ConquasDocument18 pagesConquasSyahir AzhariNo ratings yet

- Guidelines and Space Standards For Barrier Free Access For People With Disabilities in IndiaDocument43 pagesGuidelines and Space Standards For Barrier Free Access For People With Disabilities in IndiaVaishnavi Jayakumar100% (2)

- Haley C F T T F T: AnswersDocument1 pageHaley C F T T F T: AnswersHang NguyenNo ratings yet

- Ankur PPT of Mohanjo DaroDocument18 pagesAnkur PPT of Mohanjo DaroAnkur25No ratings yet

- Vernacular Architecture: Bhunga Houses, GujaratDocument12 pagesVernacular Architecture: Bhunga Houses, GujaratArjun GuptaNo ratings yet

- Lay Outing Reference Line Questionnaire Interpretation of Plans and Details Self-Check 1.1-1Document27 pagesLay Outing Reference Line Questionnaire Interpretation of Plans and Details Self-Check 1.1-1Mis Jheva AmbayecNo ratings yet

- Fl-Acp0led PDF PDFDocument3 pagesFl-Acp0led PDF PDFAndrea QuinoNo ratings yet

- The Role of History in Architectural EducationDocument16 pagesThe Role of History in Architectural EducationAlisher SadykovNo ratings yet

- Abby HatcherDocument53 pagesAbby HatcherDave PembertonNo ratings yet

- Choki Dhani, Jaipur. Bab Al Sham'S Resort. Heritage Resort, Kagal. Madurai HeritageDocument1 pageChoki Dhani, Jaipur. Bab Al Sham'S Resort. Heritage Resort, Kagal. Madurai HeritageSourabh SutarNo ratings yet

- Pricelist SK Pro April 2021 (Customer)Document25 pagesPricelist SK Pro April 2021 (Customer)Mulki BaiquniNo ratings yet

- Drawing ApprovalDocument14 pagesDrawing ApprovalAdhi LatifNo ratings yet

- SLD MVDocument1 pageSLD MVAhmed AboelgoodNo ratings yet

- Schedule of Foundations: Typical Details of Rubble Foundation & Plinth BeamDocument1 pageSchedule of Foundations: Typical Details of Rubble Foundation & Plinth BeamchaNo ratings yet

- MS For Installation of TilesDocument6 pagesMS For Installation of TilesImho TepNo ratings yet

- Simon Humphreys 8july15Document45 pagesSimon Humphreys 8july15Pudu MounikaNo ratings yet

- Electrical DesignDocument1 pageElectrical DesignTrikam PatelNo ratings yet

- MBR Tank Cover - 02 - r1Document5 pagesMBR Tank Cover - 02 - r1Nirvekala BalakrishnanNo ratings yet

- Jumeirah Hotels Resorts MICE Directory 2016Document80 pagesJumeirah Hotels Resorts MICE Directory 2016Fady Medhat FarahatNo ratings yet

- Building & InvestmentDocument84 pagesBuilding & InvestmentWong Chee LoongNo ratings yet

- 3rd AUG - 2022Document39 pages3rd AUG - 2022Ranjeet SinghNo ratings yet

- Construction of New Runway From Pier-Type Jacket Structures With Large-Diameter Long Steel Pipe PilesDocument20 pagesConstruction of New Runway From Pier-Type Jacket Structures With Large-Diameter Long Steel Pipe PilesAntonius PuterakaNo ratings yet