Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy Pada Spastic Triplegi CP

Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy Pada Spastic Triplegi CP

Uploaded by

DellCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Ctev Short CaseDocument3 pagesCtev Short CaseEmmanuel DanielsNo ratings yet

- 2021-02-04 ECP Baby Food Staff ReportDocument59 pages2021-02-04 ECP Baby Food Staff ReportNational Content DeskNo ratings yet

- Career Research PaperDocument5 pagesCareer Research Paperapi-249918037100% (2)

- Does Sarcopenia Predict Change in Mobility After Hip Fracture? A Multicenter Observational Study With One-Year Follow-UpDocument10 pagesDoes Sarcopenia Predict Change in Mobility After Hip Fracture? A Multicenter Observational Study With One-Year Follow-UpliantariNo ratings yet

- Long Term Outcome of Isolated DiaphysealDocument5 pagesLong Term Outcome of Isolated DiaphysealVIDevAryanNo ratings yet

- A Trial of Imaging Selection and Endovascular Treatment For Ischemic StrokeDocument10 pagesA Trial of Imaging Selection and Endovascular Treatment For Ischemic StrokeSim M ChangNo ratings yet

- Hip Dislocation Are Hip Precautions Necessary in Anterior ApproachesDocument6 pagesHip Dislocation Are Hip Precautions Necessary in Anterior Approaches阿欧有怪兽No ratings yet

- s41598 023 46653 4Document12 pagess41598 023 46653 4jvalenciaruiz929No ratings yet

- Abduction Treatment in Stable Hip Dysplasia Does Not Alter The Acetabular Growth: Results of A Randomized Clinical TrialDocument7 pagesAbduction Treatment in Stable Hip Dysplasia Does Not Alter The Acetabular Growth: Results of A Randomized Clinical TrialRoyman MejiaNo ratings yet

- Winters TF 1987 Gait Patterns in Spastic Hemiplegia in Children and Young AdultsDocument6 pagesWinters TF 1987 Gait Patterns in Spastic Hemiplegia in Children and Young AdultsEileen Torres CerdaNo ratings yet

- (Journal of Neurosurgery) Pathophysiology of Long-Standing Overt Ventriculomegaly in Adults PDFDocument8 pages(Journal of Neurosurgery) Pathophysiology of Long-Standing Overt Ventriculomegaly in Adults PDFKusumaningrum WijayantiNo ratings yet

- CP Spastic, Diskinetik, AtaxicDocument4 pagesCP Spastic, Diskinetik, AtaxicNura Eky VNo ratings yet

- Slipping Rib SyndromeDocument11 pagesSlipping Rib SyndromeSaleem HamilahNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1878875022016229Document7 pages1 s2.0 S1878875022016229Carlos Orozco AriasNo ratings yet

- Posters (Third Part) : SciencedirectDocument2 pagesPosters (Third Part) : SciencedirectshewaleakhileshNo ratings yet

- SCHIZAS Qualitative GradingDocument6 pagesSCHIZAS Qualitative GradingDitaAnggaraKusumaNo ratings yet

- Mccre Esh 2013Document1 pageMccre Esh 2013Francisco Javier Luza RamosNo ratings yet

- Bossi - Echocardiogric EvaluationDocument8 pagesBossi - Echocardiogric EvaluationSzendeNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.06.109Document43 pagesAccepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.06.109rameshNo ratings yet

- Crameretal 2017 Recoveryrehab IssuesDocument8 pagesCrameretal 2017 Recoveryrehab IssuesNovia RambakNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Anastesi 2Document11 pagesJurnal Anastesi 2ainunNo ratings yet

- SCIWORA-Spinal Cord Injury Without Radiological Abnormality: Veena Kalra, Sheffali Gulati, Mahesh Kamate and Ajay GargDocument3 pagesSCIWORA-Spinal Cord Injury Without Radiological Abnormality: Veena Kalra, Sheffali Gulati, Mahesh Kamate and Ajay GargnsatriotomoNo ratings yet

- CompassDocument13 pagesCompassJhunior GutierrezNo ratings yet

- A Trial of Imaging Selection and Endovascular Treatment For Ischemic StrokeDocument10 pagesA Trial of Imaging Selection and Endovascular Treatment For Ischemic StrokelorenaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Primary and Recurrent Sacral Chordoma On The Motor and Nociceptive Function of Hindlimbs in Rats - An Orthotopic Spine ModelDocument12 pagesEffects of Primary and Recurrent Sacral Chordoma On The Motor and Nociceptive Function of Hindlimbs in Rats - An Orthotopic Spine ModelgangligonNo ratings yet

- Spinal Cord Injury Without Radiographic Abnormality in AdultsDocument4 pagesSpinal Cord Injury Without Radiographic Abnormality in AdultsAle ParraNo ratings yet

- Trial of Contralateral Seventh Cervical Nerve Transfer For Spastic Arm ParalysisDocument13 pagesTrial of Contralateral Seventh Cervical Nerve Transfer For Spastic Arm ParalysisPablo Juan GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Proceedings of The 2014 Spring Meeting of The Society of British 2014Document40 pagesProceedings of The 2014 Spring Meeting of The Society of British 2014rabiatul adawiyahNo ratings yet

- Achondroplasia Natural History Study (CLARITY)Document7 pagesAchondroplasia Natural History Study (CLARITY)jakelinelagoadvNo ratings yet

- Kotnis Et Al. - Hip Arthrography in The Assessment of Children WitDocument6 pagesKotnis Et Al. - Hip Arthrography in The Assessment of Children WitsalvadorNo ratings yet

- Pressure Ulcers From Spinal Immobilization in Trauma Patients: A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesPressure Ulcers From Spinal Immobilization in Trauma Patients: A Systematic ReviewgesnerxavierNo ratings yet

- Spinal Cords BRTDocument5 pagesSpinal Cords BRTNeetumishti ChadhaNo ratings yet

- 3 - Conservative or Surgical Treatment of ISADocument9 pages3 - Conservative or Surgical Treatment of ISAMatías RamírezNo ratings yet

- Final DraftDocument10 pagesFinal Draftapi-569174359No ratings yet

- Terapia VibratoriaDocument4 pagesTerapia VibratoriaDanny QuezadaNo ratings yet

- Functional Outcome After The Conservative Management of A Fracture of The Distal HumerusDocument7 pagesFunctional Outcome After The Conservative Management of A Fracture of The Distal HumerusnireguiNo ratings yet

- Stroke CADISSDocument8 pagesStroke CADISSInge Dackrisna DaudNo ratings yet

- Sacroiliac Joint Motion in Patients With Degenerative Lumbar Spine DisordersDocument8 pagesSacroiliac Joint Motion in Patients With Degenerative Lumbar Spine DisordersVizaNo ratings yet

- Incidence and Clinical Profile of Patients With FRDocument5 pagesIncidence and Clinical Profile of Patients With FRibundaraturatuuNo ratings yet

- Kaklo RegionasDocument13 pagesKaklo RegionasVizaNo ratings yet

- Brain Metastases Whether To Add RadiosurgeryDocument2 pagesBrain Metastases Whether To Add RadiosurgeryGil LedermanNo ratings yet

- Effect of Passive Range of MotionDocument13 pagesEffect of Passive Range of Motionanggaarfina051821No ratings yet

- JCVJS 8 44Document6 pagesJCVJS 8 44Rvo ProductionNo ratings yet

- 4 2010 5 b0c82248Document4 pages4 2010 5 b0c82248Sashi MehNo ratings yet

- (2017) RCT - Efficacy of Radial Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy on Lateral Epicondylosis, and Changes in the Common Extensor Tendon Stiffness with Pretherapy and Posttherapy in Real-Time SonoelastographyDocument8 pages(2017) RCT - Efficacy of Radial Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy on Lateral Epicondylosis, and Changes in the Common Extensor Tendon Stiffness with Pretherapy and Posttherapy in Real-Time Sonoelastographycalixto1995No ratings yet

- 1547 5654 Article p607Document10 pages1547 5654 Article p607wilsonwqaNo ratings yet

- 10.1177 0300060520945158Document10 pages10.1177 0300060520945158Jr SparkNo ratings yet

- Update On Traumatic Acute Spinal Cord Injury.: DOI: 10.1016/j.medine.2016.11.007Document38 pagesUpdate On Traumatic Acute Spinal Cord Injury.: DOI: 10.1016/j.medine.2016.11.007witwiiwNo ratings yet

- Abstracts of The 2018 AANS/CNS Joint Section On Disorders of The Spine and Peripheral Nerves Annual MeetingDocument109 pagesAbstracts of The 2018 AANS/CNS Joint Section On Disorders of The Spine and Peripheral Nerves Annual MeetingEka Wahyu HerdiyantiNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Outcomes After Surgical Treatment of Pediatric Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet SyndromeDocument11 pagesLong-Term Outcomes After Surgical Treatment of Pediatric Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet Syndromewalter fire 0057No ratings yet

- Displasia de CaderaDocument10 pagesDisplasia de CaderaPAOLA ESTEFANIA ESPINOZA CASTRONo ratings yet

- Original Paper: Lumbar Disk Herniations - Clinical Status, Diagnosis, Imaging, Surgical Treatment and Global OutcomeDocument6 pagesOriginal Paper: Lumbar Disk Herniations - Clinical Status, Diagnosis, Imaging, Surgical Treatment and Global Outcomeasep budiyantoNo ratings yet

- The Role of Gait Analysis in Treating Gait Abnormalities in Cerebral PalsyDocument18 pagesThe Role of Gait Analysis in Treating Gait Abnormalities in Cerebral PalsyLizza Mora RNo ratings yet

- Penerapan Latihan Range of Motion Rom Pa A052ff55Document6 pagesPenerapan Latihan Range of Motion Rom Pa A052ff55Moh Dimas Aqil FirdausNo ratings yet

- Penerapan Latihan Range of Motion (ROM) Pasif Terhadap Peningkatan Kekuatan Otot Ekstremitas Pada Pasien Dengan Kasus StrokeDocument6 pagesPenerapan Latihan Range of Motion (ROM) Pasif Terhadap Peningkatan Kekuatan Otot Ekstremitas Pada Pasien Dengan Kasus Strokemia sulistianNo ratings yet

- Svoa Ne 02 020Document10 pagesSvoa Ne 02 020Trina ViskhawatNo ratings yet

- Trial of Endovascular Thrombectomy For Large Ischemic StrokesDocument13 pagesTrial of Endovascular Thrombectomy For Large Ischemic StrokesMABEL LUCERO OLARTE JURADONo ratings yet

- The Clinical Outcome After Extra-Articular Colles Fractures With Simultaneous Moderate Scapholunate DissociationDocument5 pagesThe Clinical Outcome After Extra-Articular Colles Fractures With Simultaneous Moderate Scapholunate DissociationYina Marcela Quintero OrtegaNo ratings yet

- 48-Article Text-462-2-10-20200831Document6 pages48-Article Text-462-2-10-20200831Dyah AjengNo ratings yet

- Timing of Aneurysm Treatment After Subarachnoid HemorrhageDocument5 pagesTiming of Aneurysm Treatment After Subarachnoid HemorrhageJulieta PereyraNo ratings yet

- Fractures of the Wrist: A Clinical CasebookFrom EverandFractures of the Wrist: A Clinical CasebookNirmal C. TejwaniNo ratings yet

- State of the Art Techniques in Critical Care Echocardiography: 3D, Tissue, ContrastFrom EverandState of the Art Techniques in Critical Care Echocardiography: 3D, Tissue, ContrastKonstantin YastrebovNo ratings yet

- EngagingWithVideogames PDFDocument300 pagesEngagingWithVideogames PDFfatmama7031No ratings yet

- VITAMIN K Drug StudyDocument2 pagesVITAMIN K Drug StudyMarl DumiligNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 Facility Layout PlanningDocument31 pagesUnit 3 Facility Layout Planningnagpal0384No ratings yet

- Social Anxiety (CASE STUDY)Document7 pagesSocial Anxiety (CASE STUDY)Angel DIMACULANGANNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Animal Assisted Therapy in Treatment.3Document7 pagesEfficacy of Animal Assisted Therapy in Treatment.3kanni.40976No ratings yet

- Prasann & Group SymposiumDocument18 pagesPrasann & Group SymposiumPrasann RoyNo ratings yet

- Slickline FATALITY - Lesson LearnedDocument5 pagesSlickline FATALITY - Lesson LearnedHossam Hussain HamoudaNo ratings yet

- 0610 w19 QP 42 PDFDocument24 pages0610 w19 QP 42 PDFrachitNo ratings yet

- Spreading The News History Successes Challenges and The Ethics of Effective DisseminationDocument12 pagesSpreading The News History Successes Challenges and The Ethics of Effective DisseminationAlfredo Sampaio FreitasNo ratings yet

- Analiza SWOTDocument2 pagesAnaliza SWOTigavrila56No ratings yet

- Effects of Occlusal Stabilization Splints On Obstructive Sleep Apnea A Randomized Controlled Trial PDFDocument7 pagesEffects of Occlusal Stabilization Splints On Obstructive Sleep Apnea A Randomized Controlled Trial PDFsemitsuNo ratings yet

- Export Development Canada (EDC) and The Forum For International Trade Training (FITT)Document2 pagesExport Development Canada (EDC) and The Forum For International Trade Training (FITT)yaya yahuNo ratings yet

- Chapter I-IvDocument23 pagesChapter I-Ivondoy tvNo ratings yet

- KMTC Short CoursesDocument1 pageKMTC Short Courseskoomekelly16No ratings yet

- Book 4Document39 pagesBook 4fatha_87No ratings yet

- Sdo Bulacan Cse Action Plan 2023 2024Document4 pagesSdo Bulacan Cse Action Plan 2023 2024heraldantoni.resurreccion100% (2)

- Short Form Plan - August 2013Document3 pagesShort Form Plan - August 2013Anonymous s0QUn5CtHUNo ratings yet

- Movie ReviewDocument2 pagesMovie ReviewezwanNo ratings yet

- Erickson - Experiencing Hypnosis v1Document164 pagesErickson - Experiencing Hypnosis v1Puruf PufNo ratings yet

- The Outbreak of The New Coronavirus Infection Known As COVIDDocument3 pagesThe Outbreak of The New Coronavirus Infection Known As COVIDPrincess Mejarito MahilomNo ratings yet

- Essay 2 Gabi A Girl in Pieces 1Document7 pagesEssay 2 Gabi A Girl in Pieces 1api-709176884No ratings yet

- 1868-Article Text-6804-1-10-20180620Document3 pages1868-Article Text-6804-1-10-20180620Wina ViqaNo ratings yet

- Do You Believe That Every Filipino Should Own A House or Is It Enough For Us To Have A Roof Above Our Head?Document2 pagesDo You Believe That Every Filipino Should Own A House or Is It Enough For Us To Have A Roof Above Our Head?Krista Jane AvilaNo ratings yet

- SUJOKDocument10 pagesSUJOKArjun Singh0% (1)

- Jaborandi OilDocument2 pagesJaborandi OilHomoeo BazaarNo ratings yet

- Brigada Eskwela Workplan Sy 2021-2022Document8 pagesBrigada Eskwela Workplan Sy 2021-2022Ana Marissa Jara DoceNo ratings yet

- Women Prisoners and Human Rights: The Juxtaposition of Rights and RealityDocument9 pagesWomen Prisoners and Human Rights: The Juxtaposition of Rights and RealityDhanesh KumarNo ratings yet

Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy Pada Spastic Triplegi CP

Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy Pada Spastic Triplegi CP

Uploaded by

DellOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy Pada Spastic Triplegi CP

Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy Pada Spastic Triplegi CP

Uploaded by

DellCopyright:

Available Formats

Open Access Original

Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.9204

Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy for the

Treatment of Spastic Triplegic Cerebral

Palsy

TS Park 1 , Susan Joh 2 , Deanna M. Walter 2 , Matthew B. Dobbs 3

1. Neurological Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis Children's Hospital, St.

Louis, USA 2. Pediatric Neurosurgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis Children's

Hospital, St. Louis, USA 3. Pediatric Orthopaedic Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St.

Louis Children's Hospital, St. Louis, USA

Corresponding author: TS Park, tspark@wustl.edu

Abstract

Background

Spastic triplegia is a recognized subtype of cerebral palsy (CP). In the course of treating spastic

triplegic children with selective dorsal rhizotomy (SDR), we found that some children who

had “minimal or mild involvement” in the stronger arm improved strikingly after undergoing

SDR. Some of them became independent ambulators, which was an outcome that is not usually

achieved in spastic quadriplegic children. However, the literature currently contains no data on

the natural clinical course and the effects of CP interventions on spastic triplegia.

Objectives

Our aim was to elucidate the clinical characteristics of spastic triplegia and the effects of SDR

on functional outcomes and the quality of life after childhood SDR.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board of the Washington University School of Medicine approved

this quality of life survey (number: 201908177). The subjects of this study were children and

adults (ages: 3.9-23.8 years at the time of the survey completion; mean: 12.1 ± 5.1 years) with

spastic triplegic CP who had undergone SDR (ages: 2.2-15.9 years; mean: 6.1 ± 3.2 years)

between 2003 and 2018 at the St. Louis Children’s Hospital. The follow-up period ranged from

1-16 years (mean: 6.0 ± 4.3 years). The study included a 76-patient cohort selected from a total

of 253 spastic triplegic CP patients who had undergone SDR. All 253 patients were contacted via

email or postal mail soliciting their participation in the study including the survey. The cohort

included all patients who responded. The survey included questions on demographic

Received 06/26/2020

information, quality of life, perceptions of health and the SDR procedure, motor and

Review began 06/30/2020

Review ended 07/06/2020 ambulatory functions, braces and orthotics, pain issues, side effects of SDR, and post-SDR

Published 07/15/2020 treatment.

© Copyright 2020

Park et al. This is an open access Results

article distributed under the terms of

the Creative Commons Attribution Thirteen patients had presented with scissored gait, and these patients had undergone partial

License CC-BY 4.0., which permits ventral rhizotomy (PVR) of L1-3 ventral roots immediately after the completion of SDR. Of

unrestricted use, distribution, and

note, 91% of 76 patients reported that SDR improved their quality of life, and 93% would

reproduction in any medium, provided

the original author and source are

recommend the procedure to other patients. After SDR, 21 more patients were able to run, 14

credited. more played recreational sports, and 18 more could walk without using walking aids. Sixteen

fewer patients used a wheelchair for long-distance walking and in crowds; 37 and 32 patients

How to cite this article

Park T, Joh S, Walter D M, et al. (July 15, 2020) Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy for the Treatment of Spastic

Triplegic Cerebral Palsy. Cureus 12(7): e9204. DOI 10.7759/cureus.9204

reported an improvement in the more affected arm and hand, respectively. Sixty-eight patients

were able to regularly strengthened their muscles at least once a week, and 60 patients

regularly stretched their legs. However, 53 patients required assistance with bathing or

showering, 50 with getting dressed, and 56 with grooming or hygiene. Forty-eight patients had

orthopedic surgery after SDR. Percutaneous hamstring-lengthening was the most common type

of orthopedic surgery performed. Three of 13 patients who received PVR and SDR required

adductor release. Six patients used medications for spasticity or dystonia. No late side effects of

SDR were observed.

Conclusions

Our report elucidates the clinical features of spastic triplegia before and after SDR. A distinct

clinical feature was the wide variation in ambulatory functions, ranging from total independent

walking to wheelchair mobility. The vast majority of patients felt that SDR improved their

motor functions and quality of life. PVR also resulted in favorable outcomes, with only three of

13 patients requiring additional adductor release surgery. There were no late complications

related to SDR surgery.

Categories: Pediatric Surgery, Neurosurgery, Orthopedics

Keywords: spastic triplegia, cerebral palsy, selective dorsal rhizotomy, ambulation, spasticity

Introduction

Spastic triplegia is a recognized subtype of spastic cerebral palsy (CP) [1]. The current

consensus on spastic triplegia is that spastic weakness is found in both lower extremities and

one upper extremity. It is often difficult to differentiate it from spastic quadriplegia as there is

no clear definition for the latter condition. In our experience, the stronger arm is almost always

affected to a varying degree in the patients, and we use “minimal to mild” involvement of the

stronger arm as a diagnostic criterion of spastic triplegia. It is possible that some clinicians may

classify some of our patients as cases of spastic quadriplegia.

We have observed that none of the spastic quadriplegic patients become independent

ambulators after undergoing selective dorsal rhizotomy (SDR). The quadriplegic patients need a

wheelchair or an assistive device to walk even after undergoing SDR. By contrast, children with

spastic triplegia who have “minimal or mild involvement” of the stronger arm show markedly

improved motor functions after SDR. Some of them even progress to walk independently. The

current literature includes no data on the natural course of spastic triplegia and outcomes after

any CP therapeutic intervention. In the present study, we examined the outcome of spastic

triplegia patients in the areas of gross motor functions, arm improvement, living status,

improvement of daily life activities, perceptions of SDR by parents and patients, and

orthopedic surgery and other treatments after SDR.

Materials And Methods

The Institutional Review Board of the Washington University School of Medicine approved this

quality of life survey (No. 201908177). We obtained consent from patients directly or from their

guardians. The subjects of this study were children and adults (ages: 3.9-23.8 years; mean: 12.1

± 5.1 years at the time of the survey completion) with spastic triplegic CP who had undergone

SDR (ages: 2.2-15.9 years; mean: 6.1 ± 3.2 years) between 2003 and 2018 at the St. Louis

Children’s Hospital. We gathered contact information from emails, mailing addresses, and

phone numbers recorded in our clinic’s database and medical records. The study survey was

sent out to potential participants electronically via email or physically via postal mail to

soliciting their participation.

2020 Park et al. Cureus 12(7): e9204. DOI 10.7759/cureus.9204 2 of 13

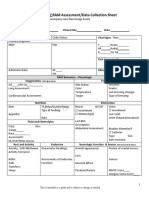

The survey included questions on demographic information, quality of life, perception of

health, the SDR procedure, motor and ambulatory functions, braces and orthotics, pain issues,

side effects of SDR, and post-SDR treatment. Demographic information included the date of

birth, current living situation, student status, and employment. Questions about bladder

function, loss of sensation, and back pain were included to assess the side effects of SDR.

Participants who indicated a sensory loss in the lower limbs were asked to indicate the location

of the numbness. Patients were asked the frequency, level (on a scale of 1-10), and location of

the body pain. Participants were also inquired about scoliosis, post-SDR orthopedic

interventions, and medications.

A five-point scale from poor to excellent was utilized to evaluate the perception of one’s

personal health, as seen in Question 1 of the SF-36 health survey [2]. Yes/no/unsure questions

were asked to understand whether the participants thought they had benefited from SDR and if

they would recommend the procedure to other hemiplegic patients. They were also given the

option to add any comments about their perception of SDR. Yes/no questions were used to

evaluate the quality of life at the time of the survey. The queries included those related to

receiving help with transferring positions, strengthening muscles, and stretching legs.

Questions were asked about the patients’ independence since SDR, and engagement in

recreational sports.

Patients were given the option to answer “Yes” or “No” to questions about motor function,

including running, walking, and sitting. These questions were based on criteria determining the

Gross Motor Function Classification (GMFCS) level of the patient [3]. Regarding arm and hand

function, patients were asked about the change in the movement of the affected arm and hand.

Results

Study cohort

Initially, our target population consisted of 253 spastic triplegic CP patients who had

undergone SDR. The definition of spastic triplegia covered the involvement of both lower limbs

and one upper limb. The other upper limb was understood to be minimally or mildly

involved. The research team obtained the contact information of the patients from the database

of the Center for Cerebral Palsy Spasticity at the St. Louis Children’s Hospital. Thirty-seven

patients did not have updated emails or postal addresses and could not be contacted, leaving

216 potential participants. Seventy-eight patients responded. Two of the 78 patients who

responded declined to participate. Thus, we eventually had a 76-patient cohort for our study,

accounting for 35% of the initially considered participants.

All 76 patients had undergone the SDR procedure as described previously [4]. The age of

patients at the time of surgery ranged between 2.2-15.9 years (mean: 6.1 ± 3.2 years). The age of

patients at the time of completing the survey was 3.9-23.8 years (mean: 12.1 ± 5.1 years). The

follow-up period ranged from 1.1 to 16.3 years (mean: 6.0 ± 4.3 years); 62% of the patients were

male, and 38% were female. Thirteen patients had presented with scissored gait and these

patients had undergone partial ventral rhizotomy (PVR) of L1-3 ventral roots immediately after

the completion of SDR.

Gross motor functions and daily physical activities

Fifty-eight patients still required assistance in daily activities even after SDR. The patients

required the most assistance with activities related to grooming and hygiene; 53 patients

required assistance with bathing or showering, 50 with getting dressed, and 56 with grooming

or hygiene. However, only 21 patients required help with eating (Table 1). Patients also

reported daily physical activities: 68 patients regularly strengthened their muscles at least once

2020 Park et al. Cureus 12(7): e9204. DOI 10.7759/cureus.9204 3 of 13

a week, and 60 regularly stretched their legs. Thirty-one patients engaged in recreational sports

(Table 2).

Despite a high proportion of patients still requiring assistance with daily living, many patients

reported improvement in ambulation: 30 patients were able to run after SDR, whereas only nine

patients had been able to run preoperatively (a 27% difference). Fourteen more patients

enjoyed recreational sports, 21 more could run and jump, and 18 more could walk without using

walking aids. Patients requiring extra body or trunk support to improve arm and hand function

went down from 58% (44 patients) to 18% (14 patients) after SDR. Fewer patients relied on

wheelchairs for long distances and crowds (down from 61 patients to 45 patients). However,

there was no change in the number of patients (11) who relied on powered wheelchairs for self-

mobility (Table 2).

Activities of daily living Number of patients (%)

Assistance with daily living

Yes No

Help with eating 21 (28%) 54 (71%)

Help with bathing or showering 53 (70%) 23 (30%)

Help with using the toilet 39 (51%) 36 (47%)

Help with getting dressed 50 (66%) 26 (34%)

Help with grooming or hygiene 56 (74%) 20 (26%)

Help with transferring from one position to another 26 (34%) 50 (66%)

Daily exercise

Regularly strengthen muscles 68 (89%) 8 (11%)

Regularly stretch legs 60 (79%) 16 (21%)

Play recreational sports 31 (41%) 45 (59%)

TABLE 1: Daily life activities after SDR for 76 spastic triplegic patients

SDR: selective dorsal rhizotomy

2020 Park et al. Cureus 12(7): e9204. DOI 10.7759/cureus.9204 4 of 13

Pre-SDR, number of patients Post-SDR, number of patients

Gross motor function*

(%) (%)

Able to run 9 (12%) 30 (39%)

Play any recreational sports 14 (18%) 28 (37%)

Able to run and jump 7 (9%) 28 (37%)

Able to walk without using walking aids 23 (30%) 41 (54%)

Able to use stairs without a handrail 3 (4%) 15 (20%)

Able to walk on any surface and environment 7 (9%) 27 (36%)

Able to walk using a walking aid (need to use a handrail for

31 (41%) 30 (39%)

stairs)

Difficulty walking on uneven surfaces, slopes, or in crowds 63 (83%) 48 (63%)

Use of wheelchair for long distances or in crowds 61 (80%) 45 (59%)

Able to sit on one's own (cannot stand or walk without support) 55 (72%) 43 (57%)

Reliance on a wheelchair (home, school, and community) 38 (50%) 19 (25%)

Require extra body or trunk support to improve arm and hand

44 (58%) 14 (18%)

function

Reliance on a powered wheelchair for self-mobility 11 (14%) 11 (14%)

Difficulty sitting on one's own and controlling head and body

17 (22%) 7 (9%)

posture

Difficulty controlling own movements 25 (33%) 12 (16%)

Require special supportive chair 34 (45%) 16 (21%)

Lifted or hoisted by another person to move 27 (36%) 15 (20%)

TABLE 2: Gross motor functions before and after SDR in 76 spastic triplegic patients

*Some patients required aid in more than one activity

SDR: selective dorsal rhizotomy

Postoperative arm and hand improvement

Thirty-seven patients reported an improvement in the movement of the affected arm after SDR,

but 36 saw no change, and one reported the condition of the arm to be worse after surgery. Two

patients did not respond to questions about the movement of the affected arm, and one patient

did not answer the question about the affected hand. Thirty-two patients reported

improvement of the affected hand. No patient reported a worse outcome related to the

movement of the affected hand (Table 3).

2020 Park et al. Cureus 12(7): e9204. DOI 10.7759/cureus.9204 5 of 13

Arm and hand function Number of patients (%)

Better Worse Unchanged

Movement of affected arm* 37 (49%) 1 (1%) 36 (47%)

Movement of affected hand 32 (42%) 0 (0%) 43 (57%)

TABLE 3: Postoperative arm and hand function in 76 spastic triplegic patients

*Some patients did not respond

Patients' perception of SDR

Sixt-nine patients (91%) believed that SDR had improved their quality of life, and 71 patients

(93%) said they would recommend the procedure to help other patients (Table 4).

Perception of SDR Number of patients (%)

Yes No Unsure

SDR improved quality of life 69 (91%) 3 (4%) 4 (5%)

Would recommend SDR to others 71 (93%) 0 (0%) 5 (7%)

TABLE 4: Perception of SDR in 76 spastic triplegic patients

SDR: selective dorsal rhizotomy

Postoperative pain

Thirty-seven patients reported having body pain post-SDR. Two patients reported constant

pain, 45 occasional pain, and 36 reported no pain. Three patients did not have a response to

body pain frequency. On a numerical scale of 1-10, with 1 being almost no pain and 10 being

the worst pain imaginable, patients' responses ranged from 1 to 9 (mean: 3.3 ± 1.8). One patient

answered with 9 and reported pain only in the ankle and foot. Others who reported a pain level

of 5 and higher mostly reported pain in the general leg area and back. One patient reported a

complete loss of sensation in any part of the legs. Two patients reported experiencing back pain

directly related to the SDR. Four patients received treatment from a physician for their back

pain, and no patient reported taking medication or seeking surgical treatment for back pain

(Table 5).

2020 Park et al. Cureus 12(7): e9204. DOI 10.7759/cureus.9204 6 of 13

Body pain Number of patients (%)

Constant Occasional No pain

Frequency of body pain* 2 (3%) 35 (46%) 36 (47%)

Numerical rating scale (0-10)

Average pain score Range: 1–9 (mean: 3.4 ± 1.8)

Location of pain

Knee 16 (21%)

Ankle and foot 16 (21%)

Back 16 (21%)

Arm 2 (3%)

Leg 22 (29%)

Complete loss of sensation in any part of legs 1 (1%)

Received treatment from physicians for back pain 4 (5%)

Medications for back pain 0 (0%)

Surgical treatment for back pain 0 (0%)

TABLE 5: Post-SDR pain in 76 spastic triplegic patients

*Some patients did not respond

SDR: selective dorsal rhizotomy

Post-SDR orthopedic surgery and medication

Of note, 63% of 76 patients received percutaneous tendon-lengthening surgery. Surgery on

hamstrings was the most common tendon- lengthening surgery. Six patients used medications

for spasticity or dystonia (Table 6).

2020 Park et al. Cureus 12(7): e9204. DOI 10.7759/cureus.9204 7 of 13

Post-SDR treatment Number of patients (%)

Tendon-lengthening surgery 48 (63%)

Number and % of 48 tendon-lengthening patients

Hamstrings 30 (63%)

Achilles tendon 24 (50%)

Gastrocnemius 6 (13%)

Adductors 11 (23%)

Hip 13 (27%)

Medications for spasticity or dystonia 6 (8%)

TABLE 6: Postoperative treatments in 76 spastic triplegic patients

SDR: selective dorsal rhizotomy

Postoperative orthotics use

Most patients currently use braces or orthotics (59 patients). A high proportion of patients use

ankle-foot orthosis (AFOs, 40 patients). Others use supramalleolar orthosis (SMOs, 15

patients), shoe inserts (10 patients), and others (four patients). Other braces and orthotics used

include, but are not limited to, night orthotics, Bioness (Bioness Inc., Santa Clarita, CA), and

immobilizers (Table 7).

Use of braces or orthotics Number of patients (%)

Currently using braces or orthotics 59 (78%)

Shoe inserts 10 (13%)

SMO 15 (20%)

AFO 40 (53%)

Other 4 (5%)

TABLE 7: Postoperative use of orthotics in 76 spastic triplegic patients

SMO: supramalleolar orthosis; AFO: ankle-foot orthosis

Perceptions of health

Almost all patients (74 patients) reported that their health was good or better. Twenty-one

patients reported excellent health, 34 very good, 19 good, two fair, and none reported poor

2020 Park et al. Cureus 12(7): e9204. DOI 10.7759/cureus.9204 8 of 13

health (Table 8).

Perception of health Number of patients (%)

Excellent 21 (28%)

Very good 34 (45%)

Good 19 (25%)

Fair 2 (3%)

Poor 0 (0%)

TABLE 8: Postoperative perception of health in 76 spastic triplegic patients

Living situation, education, and employment

Sixty-seven patients reported living with their parents, six with a significant other, two with a

roommate, and one reported living alone. Sixty-one patients were full-time students, and 10

were not students. Thirteen patients were employed at the time of the survey; two of the

employed patients were working full-time, 10 were working part-time, and one patient did not

specify the employment status (Table 9).

2020 Park et al. Cureus 12(7): e9204. DOI 10.7759/cureus.9204 9 of 13

Living situation Number of patients (%)

With significant other 6 (8%)

With parents 67 (88%)

With roommate 2 (3%)

Alone 1 (1%)

Education

Full-time student 61 (80%)

Part-time student 5 (7%)

Not a student 10 (13%)

Employment

Employed 13 (17%)

(Number and % of employed patients*)

Full-time 2 (15%)

Part-time 10 (77%)

TABLE 9: Living situation and education and employment status of 76 spastic

triplegic patients

*Some patients did not specify

Discussion

The present study was a retrospective analysis of survey responses from 76 patients out of 216

(35%) potential participants. Thus the study has some limitations [5,6]; however, we believe it

still provides information that helps to understand the effects of SDR on motor functions,

patients' perception of SDR, and the status of the daily life activities specific to a series of

spastic triplegic patients. Our study is the first of its kind to discuss spastic triplegic

patients. The significant findings of our study include: 1) the overall clinical characteristics of

spastic triplegia are distinctly different from those of spastic quadriplegia; 2) the level of

walking ability varies widely, and SDR improved walking ability in spastic triplegic patients; 3)

SDR improved arm and hand function; 4) SDR upgraded various daily-life activities; 5) the

patients' perception of SDR was overwhelmingly positive; 6) scissored gait is common in spastic

triplegia, and PVR is an alternative to adductor release; 7) minimally invasive orthopedic

surgery following SDR could replace the extensive multilevel orthopedic surgery.

It is remarkable that in our series of spastic triplegic patients, the preoperative walking ability

varied from complete independent walking and playing recreational sports to a total reliance on

wheelchairs. By contrast, none of our spastic quadriplegic patients could walk independently

after SDR. Elaboration on a few clinical insights is worthwhile. First, after SDR, virtually all

mobility-related activities and the quality of walking improved (Table 1). For patients who

2020 Park et al. Cureus 12(7): e9204. DOI 10.7759/cureus.9204 10 of 13

could walk independently before surgery, the ability to walk and dorsiflex the foot voluntarily

on both sides-with better results on the less affected side-further improved after surgery. The

presence of voluntary foot movement is a good indicator of the potential to become an

independent walker after SDR. Second, some children under five years of age walked with the

aid of walkers before surgery, and they can become independent walkers shortly after SDR. This

particular group of children has voluntary foot movement even on the weaker side [7]. Third, in

children older than seven years, SDR may improve only a single GMFCS level in general. If a

child under the age of seven years walks with a walker before surgery, their walking outcome

after surgery depends on the degree of arm and hand improvement after SDR. If one arm and

hand are too weak to use crutches after SDR, crutch-walking is not an option. Unless they

become independent walkers, they will rely on a walker and are less likely to use a single

cane. It is significant that SDR improves the arm and hand functions and increases the chance

of independent mobility. Fourth, besides mobility improvement, 41% of patients also gained

the ability to play recreational sports, and the vast majority of patients were able to actively

strengthen their muscles and stretch the lower limbs after SDR. Participation in recreational

sports and exercise becomes easier after the reduction of spasticity.

In young children under five years of age, the scissoring itself prevents progression in gait

development, and children cannot learn to walk. SDR alone cannot resolve scissoring caused by

adductor contractures. We treated the scissored gait with PVR. The surgery entails dividing 30-

50% of L1-L3 ventral roots at the time of SDR. Electrical stimulation of the ventral roots is not

useful because of the overlapped innervation of the muscles in the lower limb. The level of

ventral roots is identified by anatomy and muscle contraction in response to direct tap on the

ventral root [8,9]. In our patients, PVR treated scissored gait while avoiding permanent wide-

based gait, a well-known complication of the adductor release.

Thirteen patients (17%) had presented with scissored gait before the operation and all of them

had gone on to receive PVR after SDR. PVR was successful in 10 of the 13 patients, and no

adductor release was necessary after the procedure. The remaining three patients had recurrent

scissoring and required percutaneous adductor lengthening. PVR is our first choice for the

treatment of scissored gait due to the adductor contracture. They stretch the adductors daily

while the adductor weakness after PVR improves for four months. In our experience, PVR seems

more successful in children between the ages of two to age than in older children.

Significantly, 48 patients required orthopedic surgery after SDR. The correct orthopedic surgery

following SDR complements SDR [10]. Orthopedic surgery should be timely and minimally

invasive. Significantly, none of the patients underwent extensive multilevel bone surgery. The

most common orthopedic procedures were percutaneous Achilles tendon repair and hamstring-

lengthenings. Bony hip procedures were performed for 17% for hip subluxation. Concerning

medical treatment, only 8% of our patients required medications for the treatment of spasticity

or dystonia after SDR.

It is gratifying to note that that 91% (69 of 76 triplegic patients) of survey participants felt that

SDR had improved their quality of life, and 93% (71 patients) said they would recommend SDR

to other patients. None of the patients who did not participate in the survey reported that SDR

was a total failure in all aspects of motor movements, daily life activities, independence, and

confidence. It is encouraging that 74 of 76 patients reported good or better health even though

some of them reported mild body pain. Another encouraging fact was that 80% (61 patients) of

the participants were full-time students.

Conclusions

Our study elucidated and analyzed the clinical features of spastic triplegia. A distinct clinical

feature of spastic triplegia is the wide variation in ambulatory functions, ranging from total

2020 Park et al. Cureus 12(7): e9204. DOI 10.7759/cureus.9204 11 of 13

independent walking to wheelchair mobility. The vast majority of our patients felt that SDR had

improved their motor functions and quality of life. The outcomes of PVR procedures were also

favorable. There were no late complications related to SDR surgery.

Additional Information

Disclosures

Human subjects: Consent was obtained by all participants in this study. Washington

University Institutional Review Board issued approval 201908177. Approval Date: 09/20/19

(expedited) This project has been granted a waiver of HIPAA Authorization per section

164.512(i) of the Privacy Rule to allow the research team to use Protected Health Information

(PHI) in the context of this research study. This determination is based on the documentation

provided by the researcher in the IRB application and the assurance document signed by the

Principal Investigator. This waiver of authorization for research purposes satisfies the following

criteria: (1) The use or disclosure of the requested information involves no more than a minimal

risk to the privacy of individuals based on, at least, the presence of the following elements: (a)

An adequate plan to protect the identifiers from improper use and disclosure (b) An adequate

plan to destroy the identifiers at the earliest opportunity consistent with conduct of the

research, unless there is a health or research justification for retaining the identifiers or such

retention is otherwise required by law; and (c) Adequate written assurances that the requested

information will not be reused or disclosed to any other person or entity, except as required by

law, for authorized oversight of the research study, or for other research for which the use or

disclosure of the requested information would be permitted by the Privacy Rule; (2) The

research could not practicably be conducted without the waiver or alteration; and (3) The

research could not practicably be conducted without access to and use of the requested

information. This approval has been electronically signed by IRB Chair or Chair Designee: Jamie

Wunderle, MS 09/20/19 0935. Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did

not involve animal subjects or tissue. Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE

uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following: Payment/services info: All authors

have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted

work. Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial

relationships at present or within the previous three years with any organizations that might

have an interest in the submitted work. Other relationships: All authors have declared that

there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted

work.

References

1. Types of cerebral palsy. (2010). Accessed: June 29, 2020:

https://www.cerebralpalsy.org/about-cerebral-palsy/types-and-forms.

2. Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, O'Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Usherwood T, Westlake L: Validating

the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992,

305:160-4. 10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160

3. Wood E, Rosenbaum P: The gross motor function classification system for cerebral palsy: a

study of reliability and stability over time. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000, 42:292-6.

10.1017/s0012162200000529

4. Park TS, Johnston JM: Surgical techniques of selective dorsal rhizotomy for spastic cerebral

palsy. Technical note. Neurosurg Focus. 2006, 15:e7.

5. Park TS: In support of selective dorsal rhizotomy in cerebral palsy: the strength of clinical

experience. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020, 62:654-5. 10.1111/dmcn.14406

6. Park TS, Edwards C, Liu JL, Walter DM, Dobbs MB: Beneficial effects of childhood selective

dorsal rhizotomy in adulthood. Cureus. 2017, 5:e1077. 10.7759/cureus.1077

7. Chicoine MR, Park TS, Vogler GP, Kaufman BA: Predictors of ability to walk after selective

dorsal rhizotomy in children with cerebral palsy. Neurosurgery. 1996, 38:711-4.

8. Phillips LH 2nd, Park TS: Electrophysiological mapping of the segmental innervation of the

2020 Park et al. Cureus 12(7): e9204. DOI 10.7759/cureus.9204 12 of 13

saphenous and sural nerves. Muscle Nerve. 1993, 16:827-31. 10.1002/mus.880160804

9. Ojemann JG, Park TS, Komanetsky R, Day RA, Kaufman BA: Lack of specificity in

electrophysiological identification of lower sacral roots during selective dorsal rhizotomy. J

Neurosurg. 1997, 86:28-33. 10.3171/jns.1997.86.1.0028

10. Limpaphayom N, Stewart S, Wang L, Liu J, Park TS, Dobbs MB: Functional outcomes after

selective dorsal rhizotomy followed by minimally invasive tendon lengthening procedures in

children with spastic cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2020, 29:1-8.

10.1097/BPB.0000000000000642

2020 Park et al. Cureus 12(7): e9204. DOI 10.7759/cureus.9204 13 of 13

You might also like

- Ctev Short CaseDocument3 pagesCtev Short CaseEmmanuel DanielsNo ratings yet

- 2021-02-04 ECP Baby Food Staff ReportDocument59 pages2021-02-04 ECP Baby Food Staff ReportNational Content DeskNo ratings yet

- Career Research PaperDocument5 pagesCareer Research Paperapi-249918037100% (2)

- Does Sarcopenia Predict Change in Mobility After Hip Fracture? A Multicenter Observational Study With One-Year Follow-UpDocument10 pagesDoes Sarcopenia Predict Change in Mobility After Hip Fracture? A Multicenter Observational Study With One-Year Follow-UpliantariNo ratings yet

- Long Term Outcome of Isolated DiaphysealDocument5 pagesLong Term Outcome of Isolated DiaphysealVIDevAryanNo ratings yet

- A Trial of Imaging Selection and Endovascular Treatment For Ischemic StrokeDocument10 pagesA Trial of Imaging Selection and Endovascular Treatment For Ischemic StrokeSim M ChangNo ratings yet

- Hip Dislocation Are Hip Precautions Necessary in Anterior ApproachesDocument6 pagesHip Dislocation Are Hip Precautions Necessary in Anterior Approaches阿欧有怪兽No ratings yet

- s41598 023 46653 4Document12 pagess41598 023 46653 4jvalenciaruiz929No ratings yet

- Abduction Treatment in Stable Hip Dysplasia Does Not Alter The Acetabular Growth: Results of A Randomized Clinical TrialDocument7 pagesAbduction Treatment in Stable Hip Dysplasia Does Not Alter The Acetabular Growth: Results of A Randomized Clinical TrialRoyman MejiaNo ratings yet

- Winters TF 1987 Gait Patterns in Spastic Hemiplegia in Children and Young AdultsDocument6 pagesWinters TF 1987 Gait Patterns in Spastic Hemiplegia in Children and Young AdultsEileen Torres CerdaNo ratings yet

- (Journal of Neurosurgery) Pathophysiology of Long-Standing Overt Ventriculomegaly in Adults PDFDocument8 pages(Journal of Neurosurgery) Pathophysiology of Long-Standing Overt Ventriculomegaly in Adults PDFKusumaningrum WijayantiNo ratings yet

- CP Spastic, Diskinetik, AtaxicDocument4 pagesCP Spastic, Diskinetik, AtaxicNura Eky VNo ratings yet

- Slipping Rib SyndromeDocument11 pagesSlipping Rib SyndromeSaleem HamilahNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1878875022016229Document7 pages1 s2.0 S1878875022016229Carlos Orozco AriasNo ratings yet

- Posters (Third Part) : SciencedirectDocument2 pagesPosters (Third Part) : SciencedirectshewaleakhileshNo ratings yet

- SCHIZAS Qualitative GradingDocument6 pagesSCHIZAS Qualitative GradingDitaAnggaraKusumaNo ratings yet

- Mccre Esh 2013Document1 pageMccre Esh 2013Francisco Javier Luza RamosNo ratings yet

- Bossi - Echocardiogric EvaluationDocument8 pagesBossi - Echocardiogric EvaluationSzendeNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.06.109Document43 pagesAccepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.06.109rameshNo ratings yet

- Crameretal 2017 Recoveryrehab IssuesDocument8 pagesCrameretal 2017 Recoveryrehab IssuesNovia RambakNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Anastesi 2Document11 pagesJurnal Anastesi 2ainunNo ratings yet

- SCIWORA-Spinal Cord Injury Without Radiological Abnormality: Veena Kalra, Sheffali Gulati, Mahesh Kamate and Ajay GargDocument3 pagesSCIWORA-Spinal Cord Injury Without Radiological Abnormality: Veena Kalra, Sheffali Gulati, Mahesh Kamate and Ajay GargnsatriotomoNo ratings yet

- CompassDocument13 pagesCompassJhunior GutierrezNo ratings yet

- A Trial of Imaging Selection and Endovascular Treatment For Ischemic StrokeDocument10 pagesA Trial of Imaging Selection and Endovascular Treatment For Ischemic StrokelorenaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Primary and Recurrent Sacral Chordoma On The Motor and Nociceptive Function of Hindlimbs in Rats - An Orthotopic Spine ModelDocument12 pagesEffects of Primary and Recurrent Sacral Chordoma On The Motor and Nociceptive Function of Hindlimbs in Rats - An Orthotopic Spine ModelgangligonNo ratings yet

- Spinal Cord Injury Without Radiographic Abnormality in AdultsDocument4 pagesSpinal Cord Injury Without Radiographic Abnormality in AdultsAle ParraNo ratings yet

- Trial of Contralateral Seventh Cervical Nerve Transfer For Spastic Arm ParalysisDocument13 pagesTrial of Contralateral Seventh Cervical Nerve Transfer For Spastic Arm ParalysisPablo Juan GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Proceedings of The 2014 Spring Meeting of The Society of British 2014Document40 pagesProceedings of The 2014 Spring Meeting of The Society of British 2014rabiatul adawiyahNo ratings yet

- Achondroplasia Natural History Study (CLARITY)Document7 pagesAchondroplasia Natural History Study (CLARITY)jakelinelagoadvNo ratings yet

- Kotnis Et Al. - Hip Arthrography in The Assessment of Children WitDocument6 pagesKotnis Et Al. - Hip Arthrography in The Assessment of Children WitsalvadorNo ratings yet

- Pressure Ulcers From Spinal Immobilization in Trauma Patients: A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesPressure Ulcers From Spinal Immobilization in Trauma Patients: A Systematic ReviewgesnerxavierNo ratings yet

- Spinal Cords BRTDocument5 pagesSpinal Cords BRTNeetumishti ChadhaNo ratings yet

- 3 - Conservative or Surgical Treatment of ISADocument9 pages3 - Conservative or Surgical Treatment of ISAMatías RamírezNo ratings yet

- Final DraftDocument10 pagesFinal Draftapi-569174359No ratings yet

- Terapia VibratoriaDocument4 pagesTerapia VibratoriaDanny QuezadaNo ratings yet

- Functional Outcome After The Conservative Management of A Fracture of The Distal HumerusDocument7 pagesFunctional Outcome After The Conservative Management of A Fracture of The Distal HumerusnireguiNo ratings yet

- Stroke CADISSDocument8 pagesStroke CADISSInge Dackrisna DaudNo ratings yet

- Sacroiliac Joint Motion in Patients With Degenerative Lumbar Spine DisordersDocument8 pagesSacroiliac Joint Motion in Patients With Degenerative Lumbar Spine DisordersVizaNo ratings yet

- Incidence and Clinical Profile of Patients With FRDocument5 pagesIncidence and Clinical Profile of Patients With FRibundaraturatuuNo ratings yet

- Kaklo RegionasDocument13 pagesKaklo RegionasVizaNo ratings yet

- Brain Metastases Whether To Add RadiosurgeryDocument2 pagesBrain Metastases Whether To Add RadiosurgeryGil LedermanNo ratings yet

- Effect of Passive Range of MotionDocument13 pagesEffect of Passive Range of Motionanggaarfina051821No ratings yet

- JCVJS 8 44Document6 pagesJCVJS 8 44Rvo ProductionNo ratings yet

- 4 2010 5 b0c82248Document4 pages4 2010 5 b0c82248Sashi MehNo ratings yet

- (2017) RCT - Efficacy of Radial Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy on Lateral Epicondylosis, and Changes in the Common Extensor Tendon Stiffness with Pretherapy and Posttherapy in Real-Time SonoelastographyDocument8 pages(2017) RCT - Efficacy of Radial Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy on Lateral Epicondylosis, and Changes in the Common Extensor Tendon Stiffness with Pretherapy and Posttherapy in Real-Time Sonoelastographycalixto1995No ratings yet

- 1547 5654 Article p607Document10 pages1547 5654 Article p607wilsonwqaNo ratings yet

- 10.1177 0300060520945158Document10 pages10.1177 0300060520945158Jr SparkNo ratings yet

- Update On Traumatic Acute Spinal Cord Injury.: DOI: 10.1016/j.medine.2016.11.007Document38 pagesUpdate On Traumatic Acute Spinal Cord Injury.: DOI: 10.1016/j.medine.2016.11.007witwiiwNo ratings yet

- Abstracts of The 2018 AANS/CNS Joint Section On Disorders of The Spine and Peripheral Nerves Annual MeetingDocument109 pagesAbstracts of The 2018 AANS/CNS Joint Section On Disorders of The Spine and Peripheral Nerves Annual MeetingEka Wahyu HerdiyantiNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Outcomes After Surgical Treatment of Pediatric Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet SyndromeDocument11 pagesLong-Term Outcomes After Surgical Treatment of Pediatric Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet Syndromewalter fire 0057No ratings yet

- Displasia de CaderaDocument10 pagesDisplasia de CaderaPAOLA ESTEFANIA ESPINOZA CASTRONo ratings yet

- Original Paper: Lumbar Disk Herniations - Clinical Status, Diagnosis, Imaging, Surgical Treatment and Global OutcomeDocument6 pagesOriginal Paper: Lumbar Disk Herniations - Clinical Status, Diagnosis, Imaging, Surgical Treatment and Global Outcomeasep budiyantoNo ratings yet

- The Role of Gait Analysis in Treating Gait Abnormalities in Cerebral PalsyDocument18 pagesThe Role of Gait Analysis in Treating Gait Abnormalities in Cerebral PalsyLizza Mora RNo ratings yet

- Penerapan Latihan Range of Motion Rom Pa A052ff55Document6 pagesPenerapan Latihan Range of Motion Rom Pa A052ff55Moh Dimas Aqil FirdausNo ratings yet

- Penerapan Latihan Range of Motion (ROM) Pasif Terhadap Peningkatan Kekuatan Otot Ekstremitas Pada Pasien Dengan Kasus StrokeDocument6 pagesPenerapan Latihan Range of Motion (ROM) Pasif Terhadap Peningkatan Kekuatan Otot Ekstremitas Pada Pasien Dengan Kasus Strokemia sulistianNo ratings yet

- Svoa Ne 02 020Document10 pagesSvoa Ne 02 020Trina ViskhawatNo ratings yet

- Trial of Endovascular Thrombectomy For Large Ischemic StrokesDocument13 pagesTrial of Endovascular Thrombectomy For Large Ischemic StrokesMABEL LUCERO OLARTE JURADONo ratings yet

- The Clinical Outcome After Extra-Articular Colles Fractures With Simultaneous Moderate Scapholunate DissociationDocument5 pagesThe Clinical Outcome After Extra-Articular Colles Fractures With Simultaneous Moderate Scapholunate DissociationYina Marcela Quintero OrtegaNo ratings yet

- 48-Article Text-462-2-10-20200831Document6 pages48-Article Text-462-2-10-20200831Dyah AjengNo ratings yet

- Timing of Aneurysm Treatment After Subarachnoid HemorrhageDocument5 pagesTiming of Aneurysm Treatment After Subarachnoid HemorrhageJulieta PereyraNo ratings yet

- Fractures of the Wrist: A Clinical CasebookFrom EverandFractures of the Wrist: A Clinical CasebookNirmal C. TejwaniNo ratings yet

- State of the Art Techniques in Critical Care Echocardiography: 3D, Tissue, ContrastFrom EverandState of the Art Techniques in Critical Care Echocardiography: 3D, Tissue, ContrastKonstantin YastrebovNo ratings yet

- EngagingWithVideogames PDFDocument300 pagesEngagingWithVideogames PDFfatmama7031No ratings yet

- VITAMIN K Drug StudyDocument2 pagesVITAMIN K Drug StudyMarl DumiligNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 Facility Layout PlanningDocument31 pagesUnit 3 Facility Layout Planningnagpal0384No ratings yet

- Social Anxiety (CASE STUDY)Document7 pagesSocial Anxiety (CASE STUDY)Angel DIMACULANGANNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Animal Assisted Therapy in Treatment.3Document7 pagesEfficacy of Animal Assisted Therapy in Treatment.3kanni.40976No ratings yet

- Prasann & Group SymposiumDocument18 pagesPrasann & Group SymposiumPrasann RoyNo ratings yet

- Slickline FATALITY - Lesson LearnedDocument5 pagesSlickline FATALITY - Lesson LearnedHossam Hussain HamoudaNo ratings yet

- 0610 w19 QP 42 PDFDocument24 pages0610 w19 QP 42 PDFrachitNo ratings yet

- Spreading The News History Successes Challenges and The Ethics of Effective DisseminationDocument12 pagesSpreading The News History Successes Challenges and The Ethics of Effective DisseminationAlfredo Sampaio FreitasNo ratings yet

- Analiza SWOTDocument2 pagesAnaliza SWOTigavrila56No ratings yet

- Effects of Occlusal Stabilization Splints On Obstructive Sleep Apnea A Randomized Controlled Trial PDFDocument7 pagesEffects of Occlusal Stabilization Splints On Obstructive Sleep Apnea A Randomized Controlled Trial PDFsemitsuNo ratings yet

- Export Development Canada (EDC) and The Forum For International Trade Training (FITT)Document2 pagesExport Development Canada (EDC) and The Forum For International Trade Training (FITT)yaya yahuNo ratings yet

- Chapter I-IvDocument23 pagesChapter I-Ivondoy tvNo ratings yet

- KMTC Short CoursesDocument1 pageKMTC Short Courseskoomekelly16No ratings yet

- Book 4Document39 pagesBook 4fatha_87No ratings yet

- Sdo Bulacan Cse Action Plan 2023 2024Document4 pagesSdo Bulacan Cse Action Plan 2023 2024heraldantoni.resurreccion100% (2)

- Short Form Plan - August 2013Document3 pagesShort Form Plan - August 2013Anonymous s0QUn5CtHUNo ratings yet

- Movie ReviewDocument2 pagesMovie ReviewezwanNo ratings yet

- Erickson - Experiencing Hypnosis v1Document164 pagesErickson - Experiencing Hypnosis v1Puruf PufNo ratings yet

- The Outbreak of The New Coronavirus Infection Known As COVIDDocument3 pagesThe Outbreak of The New Coronavirus Infection Known As COVIDPrincess Mejarito MahilomNo ratings yet

- Essay 2 Gabi A Girl in Pieces 1Document7 pagesEssay 2 Gabi A Girl in Pieces 1api-709176884No ratings yet

- 1868-Article Text-6804-1-10-20180620Document3 pages1868-Article Text-6804-1-10-20180620Wina ViqaNo ratings yet

- Do You Believe That Every Filipino Should Own A House or Is It Enough For Us To Have A Roof Above Our Head?Document2 pagesDo You Believe That Every Filipino Should Own A House or Is It Enough For Us To Have A Roof Above Our Head?Krista Jane AvilaNo ratings yet

- SUJOKDocument10 pagesSUJOKArjun Singh0% (1)

- Jaborandi OilDocument2 pagesJaborandi OilHomoeo BazaarNo ratings yet

- Brigada Eskwela Workplan Sy 2021-2022Document8 pagesBrigada Eskwela Workplan Sy 2021-2022Ana Marissa Jara DoceNo ratings yet

- Women Prisoners and Human Rights: The Juxtaposition of Rights and RealityDocument9 pagesWomen Prisoners and Human Rights: The Juxtaposition of Rights and RealityDhanesh KumarNo ratings yet