Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jamadermatology Kridin 2021 Oi 210045 1634154542.6481

Jamadermatology Kridin 2021 Oi 210045 1634154542.6481

Uploaded by

Nandha KumarOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jamadermatology Kridin 2021 Oi 210045 1634154542.6481

Jamadermatology Kridin 2021 Oi 210045 1634154542.6481

Uploaded by

Nandha KumarCopyright:

Available Formats

Research

JAMA Dermatology | Original Investigation

Assessment of Treatment Approaches and Outcomes

in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Insights From a Pan-European Multicenter Study

Khalaf Kridin, MD, PhD; Marie-Charlotte Brüggen, MD, PhD; Ser-Ling Chua, PhD; Anette Bygum, DMSci;

Sarah Walsh, MB, BCh; Mirjam C. Nägeli, MD; Vesta Kucinskiene, MD, PhD; Lars French, MD, PhD;

Florence Tétart, MD; Biagio Didona, MD; Brigitte Milpied, MD; Annamari Ranki, MD, PhD;

Carmen Salavastru, MD, PhD; Eva Březinová, MD, PhD; Sapna Divani-Patel, MBBS, BSc; Tine Lorentzen, MD;

Julie Loft Nagel, MD; Skaidra Valiukeviciene, MD; Viktorija Karpavičiūtė, MD, PhD; George-Sorin Tiplica, MD;

Eva Oppel, MD; Anna Oschmann, MD; Nicolas de Prost, MD, PhD;

Artem Vorobyev, MD; Saskia Ingen-Housz-Oro, MD

Supplemental content

IMPORTANCE Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are

severe drug reactions associated with a high rate of mortality and morbidity. There is no

consensus on the treatment strategy.

OBJECTIVE To explore treatment approaches across Europe and outcomes associated with

the SJS/TEN disease course, as well as risk factors and culprit drugs.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS A retrospective pan-European multicenter cohort study

including 13 referral centers belonging to the ToxiTEN ERN-skin subgroup was conducted.

A total of 212 adults with SJS/TEN were included between January 1, 2015, and December 31,

2019, and data were collected from a follow-up period of 6 weeks.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Risk factors for severe acute-phase complications

(acute kidney failure, septicemia, and need for mechanical ventilation) and mortality 6 weeks

following admission were evaluated using a multivariable-adjusted logistic regression model.

One tool used in evaluation of severity was the Score of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

(SCORTEN), which ranges from 0 to 7, with 7 the highest level of severity.

RESULTS Of 212 patients (134 of 211 [63.7%] women; mean [SD] age, 51.0 [19.3] years), the

mean (SD) body surface area detachment was 27% (32.8%). In 176 (83.0%) patients, a culprit

drug was identified. Antibiotics (21.2%), followed by anticonvulsants (18.9%), nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (11.8%), allopurinol (11.3%), and sulfonamides (10.4%), were the

most common suspected agents. Treatment approaches ranged from best supportive care

only (38.2%) to systemic glucocorticoids (35.4%), intravenous immunoglobulins (23.6%),

cyclosporine (10.4%), and antitumor necrosis factor agents (3.3%). Most patients (63.7%)

developed severe acute-phase complications. The 6-week mortality rate was 20.8%. Maximal

body surface area detachment (ⱖ30%) was found to be independently associated with

severe acute-phase complications (fully adjusted odds ratio [OR], 2.49; 95% CI, 1.21-5.12;

P = .01) and SCORTEN greater than or equal to 2 was significantly associated with mortality

(fully adjusted OR, 10.30; 95% CI, 3.82-27.78; P < .001). Cyclosporine was associated with

a higher frequency of greater than or equal to 20% increase in body surface area detachment

in the acute phase (adjusted OR, 3.44; 95% CI, 1.12-10.52; P = .03) and an increased risk

of infections (adjusted OR, 7.16; 95% CI, 1.52-33.74; P = .01). Systemic glucocorticoids and

intravenous immunoglobulins were associated with a decreased risk of infections (adjusted

OR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.18-0.88; P = .02). No significant difference in 6-week mortality was

found between treatment groups.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE This cohort study noted differences in treatment strategies

for SJS/TEN in Europe; the findings suggest the need for prospective therapeutic studies Author Affiliations: Author

to be conducted and registries to be developed. affiliations are listed at the end of this

article.

Corresponding Author: Saskia

Ingen-Housz-Oro, MD, Dermatology

Department, AP-HP, Henri Mondor

Hospital, 51 avenue du Maréchal de

JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(10):1182-1190. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3154 Lattre de Tassigny, 94000 Créteil,

Published online August 25, 2021. France (saskia.oro@aphp.fr).

1182 (Reprinted) jamadermatology.com

© 2021 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from jamanetwork.com by NANDHAKUMAR M on 12/08/2023

Treatment Approaches and Outcomes in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Original Investigation Research

S

tevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal

necrolysis (TEN), or Lyell syndrome, are rare, delayed- Key Points

type hypersensitivity reactions associated with high lev-

Question What are the treatment approaches for

els of morbidity and mortality.1,2 The clinical hallmark of SJS Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis across

and TEN is epidermal and mucosal detachment and necrosis. Europe and their association with the disease course in the acute

The 2 entities are defined by the body surface area (BSA) of de- phase, as well as prognostic factors and culprit drugs?

tachable or detached skin: less than 10% of the BSA affected

Findings In this cohort study, among 212 patients, treatment

in SJS, 10% to 30% in overlap syndrome, and more than approaches ranged from best supportive care only to systemic

30% in TEN.1,3,4 Disease prognosis is determined by various glucocorticoids, intravenous immunoglobulins, cyclosporine, and

clinical and biological factors. Some of these parameters, such antitumor necrosis factor agents; the 6-week mortality rate was

as patient age and more than 10% BSA involvement, have been 20.8% and antibiotics were the most frequent culprit drugs.

integrated in risk prediction models, such as the Score of Meaning The findings of this study suggest differences in

Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (SCORTEN)5 and, more recently, treatment strategies for Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic

the ABCD-10.6 SCORTEN, which was used in our analysis, in- epidermal necrolysis in Europe and highlight the importance of

cludes 7 clinical and biological parameters collected at base- prospective therapeutic studies and registries.

line and is a predictive score for acute-phase mortality. The

severity levels range from 0 to 7, with 7 the highest level. The study was conducted according to the ethical guidelines

In SJS/TEN treatment, the first and most important mea- at the respective institutions and ethical approval was obtained

sure is the immediate discontinuation of the culprit drug.7 by all participating centers in accordance with the Declaration

In addition, best supportive care has been recognized as a cor- of Helsinki.13 The participants provided informed consent

nerstone of SJS/TEN treatment.8-10 In contrast, no consensus and the data were deidentified.

exists on the best adjuvant treatment. The rarity and severity

of SJS/TEN have been obstacles to performing controlled clini- Study Population and Covariates

cal trials. Current clinical practices, including the use of sys- The diagnosis of SJS/TEN was established by expert consul-

temic agents, such as cyclosporine, systemic glucocorticoids, tants specialized in inpatient dermatology on the basis of com-

intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIGs), and antitumor necro- patible clinical and histologic features.1,2 Before enrollment in

sis factor (TNF) agents, are based only on retrospective case the study, all cases of SJS/TEN were validated by the princi-

reports of series and empirical experience. The association of pal investigator at each site through comprehensive medical

these agents with the outcome, however, has not been proven records review, based on predefined clinical and histologic

in prospective trials.11,12 criteria (eg, presence of epidermal detachment, involvement

In March 2017, the European Union created the European of >2 mucosae, atypical target lesions, histologic evidence of

Reference Network for rare skin diseases (ERN-skin) to offer epidermal necrosis, and exclusion of differential diagnoses).

European Union citizens with rare skin diseases the benefits Medical records were manually reviewed for each partici-

of specialized care anywhere in Europe. ERN-skin includes pant. The following variables, which were routinely collected dur-

56 health care settings (ie, reference centers) located in 18 ing the patients’ hospital stays, were systematically retrieved and

European countries. ToxiTEN is the subgroup of ERN-skin dedi- entered in a standardized form: demographic characteristics,

cated to SJS/TEN. In this multicenter, retrospective cohort SCORTEN at admission,5 initial and maximal BSA extent of epi-

study, we aimed to explore and compare the clinical profile, dermal detachment/detachable skin, affected mucosal surfaces,

culprit drugs, prognostic factors, and treatment approaches comorbidities, culprit drugs or other putative predisposing fac-

for SJS/TEN across members of the ToxiTEN group. tors, hospitalization features, and the therapeutic regimens used.

Eligible patients were followed up at regular intervals for

6 weeks after the initial presentation to estimate survival sta-

tus. In addition, study participants were longitudinally evalu-

Methods

ated for the occurrence of severe acute complications. The

Study Design latter variables were defined as the development of at least

The present study was designed as a pan-European multi- 1 of the following conditions during the disease course: (1) sep-

center, longitudinal retrospective cohort study, performed by ticemia, (2) pulmonary infection, (3) acute kidney injury, and

the ToxiTEN group (eFigure in the Supplement). Patients were (4) respiratory distress necessitating mechanical ventilation.

recruited from 13 health care settings across 10 European coun- Subsequently, data on this longitudinal follow-up were retro-

tries: Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, spectively collected by all participating centers.

Italy, Lithuania, Romania, Switzerland, and the UK (eTable 1

in the Supplement). All participating institutes were refer- Statistical Analysis

ence centers with expertise in the management of SJS/TEN. Baseline characteristics were described as means (SDs) for con-

All adult (age ≥18 years) patients diagnosed with SJS/TEN tinuous variables and percentages for categorical values. The

between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2019, in these comparison between different variables was performed using

centers were included in the study. This study followed the the χ2 test for categorical variables and t test for continuous

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in variables. The fully adjusted model included all variables that

Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies. were found significant in the univariate analysis.

jamadermatology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Dermatology October 2021 Volume 157, Number 10 1183

© 2021 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from jamanetwork.com by NANDHAKUMAR M on 12/08/2023

Research Original Investigation Treatment Approaches and Outcomes in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

ine), patients receiving supportive therapy served as a refer-

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

of 212 Patients With SJS/TEN ence group. Only patients treated with a single agent were

included, and outcome measures were adjusted for age and

Characteristic No. (%)

SCORTEN. Findings were considered significant at unpaired

Demographic characteristics

and 2-sided P < .05. Statistical analyses were performed using

Age at diagnosis (n = 204), y

SPSS, version 25 (IBM Corp).

Mean (SD) 51.0 (19.3)

Median (range) 49.2 (18.1-94.7)

Sex (n = 211)

Men 77 (36.3) Results

Women 134 (63.7)

Demographic Characteristics

Race and ethnicity The study population comprised 212 patients; with data on sex

White 142 (67.0) available on 211 individuals, 77 (36.3%) were men and 134

Asian 25 (11.8) (63.7%) were women. The mean (SD) age at diagnosis of

African 38 (17.9) SJS/TEN was 51.0 (19.3) years, and the median age was 49.2

Unknowna 7 (3.3) years (range, 18.1-94.7 years). Most patients were of White race

Countries (142 [67.0%]), whereas 38 (17.9%) were of African ancestry and

Czech Republic 2 (0.9) 25 (11.8%) were of Asian ancestry. Table 1 further delineates

Denmark 13 (6.1) the demographic features of study participants.

Finland 5 (2.4) The mean (SD) SCORTEN was estimated at 2.2 (1.5);

France 95 (44.8) the mean (SD) percentage of BSA epidermal detachment/

Germany 10 (4.7) detachable skin at presentation was 27.0% (23.8%) and, at the

Italy 7 (3.3) maximal activity of the disease, was 39.5% (29.2%). The oral

Lithuania 12 (5.7) mucosa was the most frequently affected mucosal surface (184

Romania 5 (2.4) of 207 [88.9%]), followed by the ocular (138 of 207 [66.7%]),

Switzerland 16 (7.5) genital (129 of 207 [62.3%]), laryngeal/pharyngeal (75 of 207

UK 47 (22.2) [36.2%]), and anal (44 of 203 [21.7%]) mucosae. The mean (SD)

Clinical manifestations

number of involved mucosal surfaces was 2.8 (1.3), and 66

(31.1%) patients had 4 or more affected mucosae.

SCORTEN (n = 193)

Mean (SD) 2.2 (1.5)

Median (range) 2.0 (0.0-7.0)

Culprit Drugs and Other Putative Triggers

A culprit drug was identified in 176 (83.0%) patients. Nonsul-

BSA detachment, mean (SD)

fonamide antibiotics (21.2%), anticonvulsants (18.9%), non-

At presentation (n = 186) 27.0 (23.8)

steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (11.8%), allopurinol (11.3%),

Maximal (n = 191) 39.5 (29.2)

and sulfonamides (including sulfonamide antibiotics, 10.4%)

Distribution of mucosal lesions

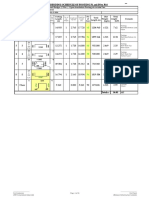

were the most common triggering agents (Figure, A). Regard-

Oral (n = 207) 184 (88.9)

ing antibiotics, β-lactams (44.4%), fluoroquinolones (35.6%),

Ocular (n = 207) 138 (66.7)

and vancomycin (11.1%) were the most common classes (Figure,

Laryngeal/pharyngeal (n = 207) 75 (36.2)

B). Among patients with anticonvulsant-induced SJS/TEN,

Genital (n = 207) 129 (62.3) exposure to aromatic anticonvulsants (eg, carbamazepine,

Anal (n = 203) 44 (21.7) phenytoin, and phenobarbital), was documented in 87.5% of

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; SCORTEN, Score of Toxic Epidermal the patients (Figure, C).

Necrolysis; SJS, Stevens-Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis. In 36 patients (17.0%), a detailed medical history did not

a

No further breakdown of categories comprising unknown race is available. reveal exposure to potential culprit medications. In these

There were 7 patients with unknown ethnic background.

patients, the development of SJS/TEN was attributed to

Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection (4 [11.1%]), other infec-

The independent associations between demographic, dis- tious agents (6 [16.7%]), and autoimmune comorbidities

ease-specific, and comorbidity variables with the risk of mor- (5 [13.9%]). No trigger was found in the remaining 21 (58.3%)

tality and severe complications were evaluated using multi- patients who had no culprit drug identified.

variable-adjusted logistic regression and are reported as odds

ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs. Entry and removal limits were set at Management and Treatment Regimens

P < .05 in the univariate analysis. The covariates included in Our analysis showed that treatment for most patients was man-

the regression model were treated as dichotomous and en- aged in dermatology inpatient wards (144 [69.6%]), whereas

compassed, among others, age, with a cutoff set at 40 years treatment for 100 patients (48.3%) was managed in intensive

in accordance with age limit in SCORTEN, and a SCORTEN of care units and, for 40 patients (19.3%), in burn units; 72 pa-

2 (the median value of this severity score in our cohort). In the tients (34.0%) received treatment in both dermatology and

analysis evaluating outcome measures in the frequent treat- intensive care units during the acute phase. One hundred thirty-

ment regimens (systemic glucocorticoids, IVIG, and cyclospor- two patients (62.3%) were referred from other health care fa-

1184 JAMA Dermatology October 2021 Volume 157, Number 10 (Reprinted) jamadermatology.com

© 2021 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from jamanetwork.com by NANDHAKUMAR M on 12/08/2023

Treatment Approaches and Outcomes in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Original Investigation Research

cilities, and 80 individuals (37.7%) were directly admitted to the

Figure. Distribution of General Culprit Drugs, Culprit Antibiotics,

participating centers (eTable 2 in the Supplement). The mean Culprit Anticonvulsants, and Treatment Modalities

(SD) duration of inpatient hospital stays was 25.0 (28.3) days.

Treatment for 81 (38.2%) patients was managed with sup- A Overall

portive treatment only. Systemic glucocorticoids were the most

Antibiotics

frequently used therapy, being administered to 75 patients

Anticonvulsants

(35.4%). Other agents used included IVIG (50 [23.6%]), cyclo-

NSAIDs

sporine (22 [10.4%]), and antitumor necrosis factor (7 [3.3%])

Allopurinol

(Figure, D; eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Sulfonamides

Burden of and Risk Factors for Mortality and Complications Fluconazole

Forty-four patients (20.8%) died during the initial 6 weeks of Other

the study. Table 2 reports univariate and multivariable analy- No suspected drug

ses to identify risk factors for mortality within the first 6 weeks.

0 5 10 15 20 25

SCORTEN greater than or equal to 2 was significantly associ- Incidence, %

ated with susceptibility to mortality (fully adjusted OR, 10.30;

95% CI, 3.82-27.78; P < .001). Other demographic variables, B Antibiotics

comorbid conditions, disease-specific features, and treat-

Lactams

ment modalities were not independently associated with the

Fluoroquinolones

risk of mortality (Table 2).

Vancomycin

We assessed the frequency and risk factors of severe acute-

Other

phase complications. A total of 135 patients (63.7%) experi-

enced severe complications; septicemia occurred in 59 pa- 0 10 20 30 40 50

tients (27.8%) and pulmonary infections occurred in 58 patients Incidence, %

(27.3%). Acute kidney injury developed in 43 patients (20.3%),

and 67 patients (31.6%) required mechanical ventilation C Anticonvulsants

(eTable 2 in the Supplement). Aromatic

Table 3 presents the risk factors for severe acute-phase Nonaromatic

complications during the course of SJS/TEN. Maximal BSA Aromatic and nonaromatic

detachment greater than or equal to 30% was found to be in-

0 20 40 60 80 100

dependently associated with the occurrence of severe acute-

Incidence, %

phase complications (fully adjusted OR, 2.49; 95% CI, 1.21-

5.12; P = .01). Although ocular involvement (age- and severity-

D SJS treatment

adjusted OR, 2.25; 95% CI, 1.17-4.32; P = .02) and cyclosporine

treatment (age- and severity-adjusted OR, 4.17; 95% CI, 1.17- Systemic corticosteroids

14.89; P = .03) were associated with complications after ad- Intravenous immunoglobulin

justing for age and severity, they fell short of significance in Cyclosporine

the fully adjusted model. TNF antagonists

G-CSF

Disease Outcomes With Different Treatment Supportive only

Table 4 delineates SJS/TEN-related outcomes and complica-

0 10 20 30 40 50

tions among patients who received monotherapy with sys-

Incidence, %

temic glucocorticoids (n = 52), IVIG (n = 28), or cyclosporine

(n = 20) compared with those treated supportively (n = 81). G-CSF indicates granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal

Following the adjustment for age and SCORTEN, systemic anti-inflammatory drugs; SJS, Stevens-Johnson syndrome; TNF, tumor

necrosis factor.

glucocorticoids were associated with a lower risk of exten-

sive disease (defined as maximal BSA detachment ≥30%; ad-

justed OR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.05-0.51; P = .002), and cyclospor- CI, 0.05-0.63; P = .008). The baseline characteristics of pa-

ine was associated with a greater than or equal to 20% increase tients in the different treatment groups are outlined in eTable 4

in BSA detachment during the disease course (adjusted OR, in the Supplement.

3.44; 95% CI, 1.12-10.52; P = .03).

Cyclosporine use was associated with an increased risk for

any type of infection (adjusted OR, 7.16; 95% CI, 1.52-33.74;

P = .01). Systemic glucocorticoids were associated with a

Discussion

reduced risk of any infection (adjusted OR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.18- The aim of this multicenter retrospective study was to ex-

0.88; P = .02) and mechanical ventilation (adjusted OR, 0.34; plore the profile of patients, culprit drugs, treatment ap-

95% CI, 0.12-0.96; P = .05). Treatment with IVIG was associ- proaches, and prognostic factors of SJS/TEN across expert

ated with a decreased risk of septicemia (adjusted OR, 0.17; 95% centers within European countries. In line with previous data,1

jamadermatology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Dermatology October 2021 Volume 157, Number 10 1185

© 2021 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from jamanetwork.com by NANDHAKUMAR M on 12/08/2023

Research Original Investigation Treatment Approaches and Outcomes in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Table 2. Risk Factors for Mortality Within 6 Weeks of Follow-up in Patients With SJS/TEN as Identified by Logistic Regression Modela

No./No. (%) patients

Died in the Did not die Age- and

first 6 wk in the first 6 wk Unadjusted P severity-adjusted P Fully adjusted P

Variable (n = 44) (n = 157) OR (95% CI) value OR (95% CI)b value OR (95% CI)c value

Men 20/44 (45.5) 52/157 (33.1) 1.68 (0.85-3.32) .13 NA NA NA NA

Age at diagnosis ≥40 y 37/43 (86.0) 95/156 (60.9) 3.96 (1.58-9.94) .002d 1.89 (0.67-5.34) .23 2.03 .25

(0.61-6.78)

African ancestry (vs White and 8/44 (18.2) 29/157 (18.5) 0.98 (0.41-2.33) .97 NA NA NA NA

Asian ancestry)

Comorbid conditions

Autoimmune disease 11/44 (25.0) 24/157 (15.3) 1.85 (0.83-4.15) .13 NA NA NA NA

Iatrogenic 17/44 (38.6) 19/157 (12.1) 4.57 (2.11-9.91) <.001d 2.35 (0.94-5.85) .07 1.95 .20

immunosuppression (0.70-5.42)

Cancer 16/44 (36.4) 20/157 (12.7) 3.91 (1.81-8.48) <.001d 1.48 (0.59-3.67) .40 1.00 >.99

(0.35-2.87)

HIV 4/44 (9.1) 7/157 (4.5) 2.14 (0.60-7.68) .23 NA NA NA NA

Culprit drug

Anticonvulsants 4/44 (9.1) 36/150 (24.0) 0.32 (0.11-0.95) .03d 0.45 (0.14-1.52) .20 0.55 .38

(0.14-2.12)

Antibiotics 14/44 (31.8) 27/150 (18.0) 2.13 (1.00-4.54) .048d 1.30 (0.53-3.21) .56 1.15 .79

(0.41-3.29)

Allopurinol 9/44 (20.5) 15/150 (10.0) 2.31 (0.94-5.73) .06 NA NA NA NA

Sulfonamide 4/44 (9.1) 18/150 (12.0) 0.73 (0.24-2.92) .59 NA NA NA NA

Fluconazole 2/44 (4.5) 2/150 (1.3) 3.52 .19 NA NA NA NA

(0.48-25.18)

NSAIDs 4/44 (9.1) 19/150 (12.0) 0.73 (0.24-2.29) .59 NA NA NA NA

No suspected drug 3/44 (6.8) 23/150 (15.3) 0.40 (0.12-1.42) .15 NA NA NA NA

Other putative triggers

Mycoplasma 0/35 (0.0) 8/138 (5.8) 0.94 (0.90-0.98) .15 NA NA NA NA

Other infections 1/44 (2.3) 5/157 (3.2) 0.71 (0.08-6.21) .75 NA NA NA NA

Disease severity

SCORTEN>2 35/43 (81.4) 35/146 (24.0) 13.88 <.001d 12.04 <.001d 10.30 <.001d

(5.89-32.69) (5.01-28.94) (3.82-27.78)

BSA at presentation >10% 36/41 (87.8) 86/141 (61.0) 4.61 .001d NA NA NA NA

(1.70-12.45)

Maximal BSA≥30% 28/40 (70.0) 70/143 (49.0) 2.43 (1.15-5.16) .02d NA NA NA NA

Affected mucosal surfaces

Oral 40/44 (90.9) 143/157 (91.1) 0.98 (0.31-3.14) .97 NA NA NA NA

Ocular 27/44 (61.4) 110/157 (70.1) 0.68 (0.34-1.36) .27 NA NA NA NA

Larynx/pharynx 19/44 (43.2) 55/157 (35.0) 1.41 (0.71-2.78) .32 NA NA NA NA

Genital 23/44 (52.3) 108/157 (68.8) 0.50 (0.25-0.98) .04d 0.72 (0.32-1.62) .43 0.77 .57

(0.31-1.89)

Anal 7/42 (16.7) 40/154 (26.0) 0.57 (0.24-1.39) .21 NA NA NA NA

Treatment modalities

Supportive care only 13/44 (29.5) 64/157 (40.8) 0.61 (0.30-1.25) .18 NA NA NA NA

Systemic glucocorticoids 16/44 (36.4) 52/157 (31.1) 1.15 (0.57-2.32) .69 NA NA NA NA

Cyclosporine 3/44 (6.8) 19/157 (12.1) 0.53 (0.15-1.89) .32 NA NA NA NA

IVIG 16/44 (36.4) 34/157 (21.7) 2.07 (1.00-4.26) .046d 2.31 (0.78-6.79) .13 1.61 .36

(0.58-4.52)

Anti-TNF agents 3/44 (6.8) 4/157 (2.5) 2.80 .17 NA NA NA NA

(0.60-13.00)

b

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; Severity was defined based on SCORTEN.

NA, not applicable; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; OR, odds c

Entry and removal limits to fully adjusted multivariable analysis were set at

ratio; SCORTEN, Score of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis; SJS, Stevens-Johnson P < .05. Given the collinearity between SCORTEN and BSA involvement,

syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis; TNF, tumor necrosis factor. only the former was included in the multivariable model.

a

This analysis was confined to 201 patients in whom follow-up data 6 weeks d

Significant at P < .05.

following the diagnosis was available.

among the 212 adults with SJS/TEN included in our cohort, no amides), including β-lactams, were the most common identi-

culprit drug could be identified in approximately 20% of the fied culprit drugs in these patients, followed by allopurinol and

patients with SJS/TEN. Antibiotics (not including sulfon- anticonvulsants. Although these are the overall most com-

1186 JAMA Dermatology October 2021 Volume 157, Number 10 (Reprinted) jamadermatology.com

© 2021 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from jamanetwork.com by NANDHAKUMAR M on 12/08/2023

Treatment Approaches and Outcomes in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Original Investigation Research

Table 3. Risk Factors for Severe Acute Complications in Patients With SJS/TEN as Identified by Logistic Regression Model

No./No. (%) patients Age- and

With acute Without acute severity-

complications complications Unadjusted OR P adjusted OR P Fully adjusted P

Variable (n = 135) (n = 77) (95% CI) value (95% CI)a value OR (95% CI)b value

Men 49/135 (36.4) 28/77 (36.4) 0.98 (0.56-1.78) .99 NA NA NA NA

Age at diagnosis ≥40 y 91/131 (69.5) 45/73 (61.6) 1.42 (0.78-2.58) .26 NA NA NA NA

African ancestry (vs White and 28/135 (20.7) 10/77 (13.0) 1.75 (0.80-3.84) .16 NA NA NA NA

Asian ancestry)

Comorbid conditions

Autoimmune disease 23/135 (17.0) 14/77 (18.2) 0.92 (0.44-1.92) .83 NA NA NA NA

Iatrogenic 27/135 (20.0) 10/77 (13.0) 1.68 (0.77-3.68) .20 NA NA NA NA

immunosuppression

Cancer 27/135 (20.0) 10/77 (13.0) 1.68 (0.76-3.68) .20 NA NA NA NA

HIV 10/135 (7.4) 2/77 (2.6) 3.00 (0.64-14.06) .15 NA NA NA NA

Culprit drug

Anticonvulsants 23/134 (17.2) 17/70 (24.3) 0.65 (0.32-1.31) .22 NA NA NA NA

Antibiotics 25/134 (18.7) 20/70 (27.4) 0.57 (0.29-1.13) .11 NA NA NA NA

Allopurinol 20/134 (14.9) 4/70 (5.7) 2.90 (0.95-8.83) .05 NA NA NA NA

Sulfonamide 16/134 (11.9) 6/70 (8.6) 1.45 (0.54-3.88) .46 NA NA NA NA

Fluconazole 2/134 (1.5) 2/70 (2.9) 0.52 (0.07-3.74) .51 NA NA NA NA

NSAIDs 16/134 (11.9) 9/70 (12.9) 0.92 (0.38-2.20) .85 NA NA NA NA

No suspected drug 19/134 (14.2) 7/70 (10.0) 1.20 (0.51-2.78) .40 NA NA NA NA

Other putative triggers

Mycoplasma 5/115 (4.3) 3/68 (4.4) 0.99 (0.23-4.26) .98 NA NA NA NA

Other infections 5/135 (3.7) 1/77 (1.3) 2.92 (0.34-25.49) .31 NA NA NA NA

Severity NA NA NA NA

SCORTEN>2 54/129 (41.9) 18/64 (28.1) 1.84 (0.96-3.52) .06 NA NA NA NA

BSA at presentation >10% 93/122 (76.2) 31/64 (48.4) 3.41 (1.79-6.50) <.001c NA NA NA NA

Maximal BSA≥30% 81/126 (64.3) 18/65 (27.7) 4.70 (2.44-9.04) <.001c 4.43 <.001c 2.49 .01

(2.31-8.50) (1.21-5.12)

Affected mucosal surfaces

Oral 123/135 (91.1) 66/77 (85.7) 1.71 (0.72-4.08) .22 NA NA NA NA

Ocular 97/135 (71.9) 43/77 (55.8) 2.02 (1.12-3.63) .02c 2.25 .02c 1.77 .12

(1.17-4.32) (0.86-3.63)

Larynx/pharynx 55/135 (40.7) 20/77 (26.0) 1.96 (1.06-3.62) .03c 1.76 .09 1.49 .29

(0.91-3.41) (0.71-3.12)

Genital 91/135 (67.4) 43/77 (55.8) 1.64 (0.92-2.91) .09 NA NA NA NA

Anal 27/131 (20.6) 20/76 (26.3) 0.73 (0.37-1.41) .35 NA NA NA NA

Treatment modalities

Supportive care only 50/135 (37.0) 31/77 (40.3) 0.87 (0.49-1.55) .64 NA NA NA NA

Systemic glucocorticoids 42/135 (31.1) 33/77 (42.9) 0.60 (0.34-1.08) .09 NA NA NA NA

Cyclosporine 19/135 (14.1) 3/77 (3.9) 4.04 (1.16-14.13) .02c 4.17 .03c 3.42 .08

(1.17-14.89) (0.86-13.53)

IVIG 35/135 (25.9) 15/77 (19.5) 1.45 (0.73-2.86) .29 NA NA NA NA

Anti-TNF agents 3/135 (2.2) 4/77 (5.2) 0.42 (0.09-1.90) .24 NA NA NA NA

b

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; Entry and removal limits to fully adjusted multivariable analysis were set at

NA, not applicable; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; OR, odds P < .05.

ratio; SCORTEN, Score of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis; SJS, Stevens-Johnson c

Significant at P < .05.

syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

a

Severity was defined based on SCORTEN.

mon causative agents of SJS/TEN, our results differ from cotrimoxazole) were considered as lower risk drugs.16 The

other studies. A study of a cohort of 187 patients from South divergences between these observations can, at least par-

Korea identified allopurinol as the most common culprit tially, be associated with the genetic background, ie, differ-

drug, followed by carbamazepine and lamotrigine.14 In a ences in risk human leukocyte antigen allele expression,

multicenter retrospective study from the US, sulfamethoxa- which varies among races/ethnicities1: most of our patients

zole with trimethoprim was identified as the most common were of White race. Moreover, regional differences in pre-

culprit drug.15 In the EuroSCAR study, antibiotics (except scription practices, such as the use of cotrimoxazole for uri-

jamadermatology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Dermatology October 2021 Volume 157, Number 10 1187

© 2021 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from jamanetwork.com by NANDHAKUMAR M on 12/08/2023

Research Original Investigation Treatment Approaches and Outcomes in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Table 4. Difference in Disease Outcomes and Complications Among Patients With SJS/TEN Receiving Systemic Glucocorticoids, IVIG, Cyclosporine,

and Supportive Therapya

Systemic corticosteroids

monotherapy IVIG monotherapy Cyclosporine monotherapy Supportive care

(n = 52) (n = 28) (n = 20) (n = 81),

Adjusted OR P Adjusted OR P Adjusted OR P adjusted OR

Characteristic (95% CI)b value (95% CI)b value (95% CI)b value (95% CI)b

SJS/TEN-related outcomes

Maximal BSA detachment ≥30% 0.16 (0.05-0.51) .002c 2.19 (0.73-6.58) .16 2.77 (0.89-8.60) .08 1 [Reference]

Increase in BSA detachment 0.66 (0.19-2.31) .52 2.07 (0.72-5.97) .18 3.44 (1.12-10.52) .03c 1 [Reference]

≥20% during the disease course

Complications

Any infection 0.40 (0.18-0.88) .02c 0.60 (0.24-1.52) .28 7.16 (1.52-33.74) .01c 1 [Reference]

c

Septicemia 0.43 (0.17-1.09) .07 0.17 (0.05-0.63) .008 2.74 (0.95-7.92) .06 1 [Reference]

Acute kidney injury 0.61 (0.20-1.82) .37 1.68 (0.56-5.00) .35 2.24 (0.64-7.91) .21 1 [Reference]

Mechanical ventilation 0.34 (0.12-0.96) .04c 1.25 (0.45-3.45) .67 2.04 (0.69-6.10) .20 1 [Reference]

Mortality within the first 6 wk 0.79 (0.24-2.62) .70 1.48 (0.42-5.21) .55 1.00 (0.17-5.70) >.99 1 [Reference]

b

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; Adjusted for age and Score of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis.

SJS, Stevens-Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis. c

Significant at P < .05.

a

Patients receiving systemic therapy in addition to systemic corticosteroids

(n = 23), IVIG (n = 22), and cyclosporine (n = 2) were excluded.

nary tract infections or soft tissue infections, could further The mortality rate of 20.8% at 6 weeks in our study was simi-

contribute to this observation.17 lar to some studies,30,31 but higher than in other studies.15,19 Our

There is an overall consensus on the importance of investigation suggests that the extent of BSA detachment and

best supportive care, which is recognized in various national respiratory failure were risk factors for both mortality and life-

guidelines as the cornerstone of SJS/TEN treatment to reduce threatening complications during the acute phase.5,32-34

mortality.9,10,18-20 In contrast, the efficacy of adjuvant thera-

pies for SJS/TEN is still debated. To our knowledge, there are Limitations

neither guidelines nor comparative studies on the use of ad- This study has limitations. First, we did not include children

juvant agents in SJS/TEN, and their use mostly relies on case because triggers, prognosis, and management of SJS/TEN in

series, case reports, and clinical experience. Our study, thus, children differ considerably from those in adults. Further-

provides a comparative report on the wide range of these ad- more, childhood SJS/TEN may be misdiagnosed as erythema

juvant therapies and our results mirror the center-dependent multiforme.35 Second, although our multicenter study in-

diversity of therapeutic approaches in SJS/TEN, ranging from cluded various countries and centers, with substantially dif-

IVIG,21,22 systemic glucocorticoids,23 antitumor necrosis fac- fering numbers of patients included per center, the selection

tor agents,24-26 and cyclosporine27-29 to supportive care only. of the sites may have biased our findings. Third, owing to the

Although our study was not designed or able to compare the retrospective data collection, caution is warranted when draw-

efficacy of different treatment approaches, it yielded some ing conclusions regarding treatment strategies. Prospective

interesting results: cyclosporine was associated with an in- clinical trials are needed to evaluate the efficacy of the differ-

crease of BSA affected and an overall higher risk of infec- ent adjuvant treatments in SJS/TEN.

tions, and IVIG was associated with a decreased risk of sep-

sis. Systemic glucocorticoids were associated with a lower rate

of patients with a maximal affected BSA greater than or equal

to 30% over the disease course. Although our results are not

Conclusions

sufficient for conclusions to be made as to the superiority of This multicenter European retrospective study on 212 adults

any adjuvant treatment, they suggest the need to investigate with SJS/TEN provides an overview on patients’ profiles, drug

the associations of different treatments not only with mortal- triggers, prognosis, and treatment regimens within the

ity, but also with the occurrence of life-threatening complica- ERN-skin network. This study describes the current diversity

tions and epidermal healing during the acute phase. Given that of treatment approaches across centers and countries. Fu-

our study only covered the acute-phase observation period, ture studies and registries, such as IRTEN (the international

further studies are warranted to explore whether patients may registry of TEN),2 may aim to prospectively collect compre-

exhibit different clinical outcomes, including long-term com- hensive clinical and biological information on more patients

plications and mortality. with SJS/TEN to ultimately improve the treatment.

ARTICLE INFORMATION Published Online: August 25, 2021. Author Affiliations: Lübeck Institute of

Accepted for Publication: July 5, 2021. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3154 Experimental Dermatology, University of Lübeck,

Lübeck, Germany (Kridin, Vorobyev); Azrieli Faculty

of Medicine, Bar-Ilan University, Safed, Israel

1188 JAMA Dermatology October 2021 Volume 157, Number 10 (Reprinted) jamadermatology.com

© 2021 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from jamanetwork.com by NANDHAKUMAR M on 12/08/2023

Treatment Approaches and Outcomes in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Original Investigation Research

(Kridin); Department of Dermatology, University Concept and design: Kridin, Brüggen, Walsh, Nägeli, 6. Noe MH, Rosenbach M, Hubbard RA, et al.

Hospital of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland (Brüggen, Tétart, Didona, Březinová, Tiplica, de Prost, Development and validation of a risk prediction

Nägeli); Faculty of Medicine, University of Zurich, Vorobyev, Ingen-Housz-Oro. model for in-hospital mortality among patients

Zurich, Switzerland (Brüggen, Nägeli); Medical Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: with Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal

Campus Davos, Davos, Switzerland (Brüggen); Kridin, Chua, Bygum, Walsh, Nägeli, Kucinskiene, necrolysis—ABCD-10. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(4):

ToxiTEN group, European Reference Network for French, Milpied, Ranki, Salavastru, Březinová, 448-454. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5605

Rare Skin Diseases, Paris, France (Brüggen, Chua, Divani-Patel, Lorentzen, Loft Nagel, Valiukeviciene, 7. Garcia-Doval I, LeCleach L, Bocquet H, Otero XL,

Bygum, Walsh, Kucinskiene, French, Tétart, Didona, Karpavičiūtė, Tiplica, Oppel, Oschmann, Vorobyev, Roujeau JC. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and

Milpied, Ranki, Salavastru, Březinová, Tiplica, Ingen-Housz-Oro. Stevens-Johnson syndrome: does early withdrawal

Vorobyev, Ingen-Housz-Oro); Department of Drafting of the manuscript: Kridin, Brüggen, Ranki, of causative drugs decrease the risk of death?

Dermatology, University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Salavastru, Divani-Patel, Karpavičiūtė, Tiplica, Arch Dermatol. 2000;136(3):323-327. doi:10.1001/

Foundation Trust, Birmingham, United Kingdom Vorobyev, Ingen-Housz-Oro. archderm.136.3.323

(Chua, Divani-Patel); Department of Dermatology Critical revision of the manuscript for important

and Allergy Center, Odense University Hospital, intellectual content: Kridin, Brüggen, Chua, Bygum, 8. McPherson T, Exton LS, Biswas S, et al.

Clinical Institute, University of Southern Denmark, Walsh, Nägeli, Kucinskiene, French, Tétart, Didona, British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines

Odense, Denmark (Bygum, Lorentzen, Nagel); Milpied, Ranki, Salavastru, Březinová, Lorentzen, for the management of Stevens-Johnson

Department of Dermatology, King’s College Loft Nagel, Valiukeviciene, Oppel, Oschmann, syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in children

Hospital, London, United Kingdom (Walsh); de Prost, Vorobyev. and young people, 2018. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(1):

Department of Skin and Venereal Diseases, Statistical analysis: Kridin, Divani-Patel, 37-54. doi:10.1111/bjd.17841

Lithuanian University of Health Sciences (LUHS), Karpavičiūtė, Vorobyev. 9. Creamer D, Walsh SA, Dziewulski P, et al.

Hospital of LUHS Kauno Klinikos, European Obtained funding: Kridin. U.K. guidelines for the management of

Reference Network for Rare and Complex Diseases Administrative, technical, or material support: Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal

of the Skin members, Kaunas, Lithuania Kridin, Brüggen, Bygum, Walsh, Nägeli, necrolysis in adults 2016. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174

(Kucinskiene, Valiukeviciene); Department of Skin Kucinskiene, Ranki, Divani-Patel, Oppel, Oschmann, (6):1194-1227. doi:10.1111/bjd.14530

and Venereal Diseases, Lithuanian University of Vorobyev. 10. Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Duong T-A, Bensaid B, et al;

Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania (Kucinskiene, Supervision: Kridin, Brüggen, Bygum, Walsh, Nägeli, French National Reference Center for Toxic Bullous

Valiukeviciene, Karpavičiūtė); Department of French, Didona, Březinová, Valiukeviciene, de Prost. Dermatoses. Epidermal necrolysis French national

Dermatology, University Hospital, Munich Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Walsh diagnosis and care protocol (PNDS; protocole

University of Ludwig Maximilian, Munich, Germany reported receiving nonfinancial support from national de diagnostic et de soins). Orphanet J Rare

(French, Oppel, Oschmann); Dr Phillip Frost UCB Pharma for sponsored attendance at meeting Dis. 2018;13(1):56. doi:10.1186/s13023-018-0793-7

Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous outside the submitted work. Dr Salavastru reported

Surgery, University of Miami Miller School of 11. Zimmermann S, Sekula P, Venhoff M, et al.

receiving nonfinancial support and personal fees Systemic immunomodulating therapies for

Medicine, Miami, Florida (French); Toxic Bullous from Leo Pharma, and nonfinancial support from

Dermatoses and Severe Drug Reactions reference Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal

AbbVie outside the submitted work; in addition, necrolysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

center, TOXIBUL FIMARAD network, Assistance Dr Salavastru had a patent for Springer Nature

Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Henri Mondor JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(6):514-522.

Switzerland AG with royalties paid. Dr Tiplica doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5668

Hospital, Créteil, France (Tétart, Milpied, de Prost, reported receiving personal fees from Antibiotice,

Ingen-Housz-Oro); Department of Dermatology, nonfinancial support from A&D Pharma Marketing 12. Tsai T-Y, Huang I-H, Chao Y-C, et al.

Inserm U519, Rouen University Hospital, Rouen, & Sales Services, nonfinancial support from EGIS Treating toxic epidermal necrolysis with systemic

France (Tétart); Rare Disease Unit, I Dermatology Pharmaceutical PLC, and nonfinancial support from immunomodulating therapies: a systematic review

Division, Istituto Dermopatico dell’Immacolata, Sanofi Romania SRL outside the submitted work. and network meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol.

IRCCS, Rome, Italy (Didona); Department of No other disclosures were reported. 2021;84(2):390-397. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.122

Dermatology, Saint André Hospital, Bordeaux, 13. World Medical Association. World Medical

France (Milpied); Department of Dermatology, REFERENCES Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical

Allergology and Venereology, University of Helsinki, principles for medical research involving human

Helsinki, Finland (Ranki); Helsinki University 1. Duong TA, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Wolkenstein P,

Chosidow O. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194.

Hospital, Inflammation Center, Helsinki, Finland doi:10.1001/jama.2013.281053

(Ranki); Carol Davila University of Medicine and to drugs. Lancet. 2017;390(10106):1996-2011.

Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania (Salavastru, Tiplica); doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30378-6 14. Yang M-S, Lee JY, Kim J, et al. Searching for the

Department of Pediatric Dermatology, Colentina 2. Kuijper EC, French LE, Tensen CP, Vermeer MH, culprit drugs for Stevens-Johnson syndrome and

Clinical Hospital, Bucharest, Romania (Salavastru); Bouwes Bavinck JN. Clinical and pathogenic toxic epidermal necrolysis from a nationwide claim

First Department of Dermatovenereology, Masaryk aspects of the severe cutaneous adverse reaction database in Korea. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract.

University Faculty of Medicine, St Ann’s Faculty epidermal necrolysis (EN). J Eur Acad Dermatol 2020;8(2):690-695.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2019.

Hospital in Brno, Brno, Czech Republic (Březinová); Venereol. 2020;34(9):1957-1971. doi:10.1111/jdv.16339 09.032

Department of Dermatology, Colentina Clinical 3. Hsu DY, Brieva J, Silverberg NB, Silverberg JI. 15. Micheletti RG, Chiesa-Fuxench Z, Noe MH, et al.

Hospital, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Morbidity and mortality of Stevens-Johnson Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal

Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania (Tiplica); Intensive syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in necrolysis: a multicenter retrospective study of

care unit, AP-HP, Henri Mondor Hospital, Créteil, United States adults. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136 377 adult patients from the United States. J Invest

France (de Prost); Department of Dermatology, (7):1387-1397. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2016.03.023 Dermatol. 2018;138(11):2315-2321. doi:10.1016/j.jid.

University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, 2018.04.027

Lübeck, Germany (Vorobyev); Dermatology 4. Chaby G, Maldini C, Haddad C, et al.

Incidence of and mortality from epidermal 16. Mockenhaupt M, Viboud C, Dunant A, et al.

Department, AP-HP, Henri Mondor Hospital, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal

Créteil, France (Ingen-Housz-Oro); University necrolysis (Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic

epidermal necrolysis) in France during 2003-2016: necrolysis: assessment of medication risks with

Paris-Est Créteil EpiDermE, Créteil, France emphasis on recently marketed drugs: the

(Ingen-Housz-Oro). a four-source capture-recapture estimate. Br J

Dermatol. 2020;182(3):618-624. doi:10.1111/ EuroSCAR-study. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128(1):

Author Contributions: Drs Kridin and bjd.18424 35-44. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5701033

Ingen-Housz-Oro had full access to all of the 17. Bowen AC, Carapetis JR, Currie BJ, Fowler V Jr,

data in the study and take responsibility for the 5. Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M,

Roujeau JC, Revuz J, Wolkenstein P. SCORTEN: Chambers HF, Tong SYC. Sulfamethoxazole-

integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data trimethoprim (cotrimoxazole) for skin and soft

analysis. Drs Kridin and Brüggen contributed a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal

necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115(2):149-153. tissue infections including impetigo, cellulitis, and

equally, and Drs Vorobyev and Ingen-Housz-Oro abscess. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(4):ofx232.

contributed equally. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00061.x

doi:10.1093/ofid/ofx232

jamadermatology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Dermatology October 2021 Volume 157, Number 10 1189

© 2021 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from jamanetwork.com by NANDHAKUMAR M on 12/08/2023

Research Original Investigation Treatment Approaches and Outcomes in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

18. Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Le Floch R, Alves A, et al. Consortium. Randomized, controlled trial of TNF-α analysis of a cohort of patients with

Carrying out local care for epidermal necrolysis: antagonist in CTL-mediated severe cutaneous Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal

survey of practices. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. adverse reactions. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(3):985-996. necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(5):1197-1204.

2021;35(2):e155-e157. doi:10.1111/jdv.16884 doi:10.1172/JCI93349 doi:10.1038/jid.2012.510

19. Bettuzzi T, Penso L, de Prost N, et al. Trends in 25. Paradisi A, Abeni D, Didona D, Ricci F, 31. Diphoorn J, Cazzaniga S, Gamba C, et al;

mortality rates for Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) Canzona F, Didona B. A new case series on REACT-Lombardia study group. Incidence,

and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN): experience etanercept treatment for toxic epidermal causative factors and mortality rates of

of a single center in France between 1997 and 2017. necrolysis. Eur J Dermatol. 2020;30(5):561-568. Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic

Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(1):247-248. doi:10.1684/ejd.2020.3883 epidermal necrolysis (TEN) in northern Italy: data

20. Seminario-Vidal L, Kroshinsky D, 26. Zhang S, Tang S, Li S, Pan Y, Ding Y. from the REACT registry. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug

Malachowski SJ, et al. Society of Dermatology Biologic TNF-alpha inhibitors in the treatment of Saf. 2016;25(2):196-203. doi:10.1002/pds.3937

Hospitalists supportive care guidelines for the Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal 32. de Prost N, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Duong TA, et al.

management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic necrolysis: a systemic review. J Dermatolog Treat. Bacteremia in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic

epidermal necrolysis in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;31(1):66-73. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019. epidermal necrolysis: epidemiology, risk factors,

2020;82(6):1553-1567. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020. 1577548 and predictive value of skin cultures. Medicine

02.066 27. Valeyrie-Allanore L, Wolkenstein P, Brochard L, (Baltimore). 2010;89(1):28-36. doi:10.1097/MD.

21. Bachot N, Revuz J, Roujeau J-C. et al. Open trial of ciclosporin treatment for 0b013e3181ca4290

Intravenous immunoglobulin treatment for Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal 33. de Prost N, Mekontso-Dessap A,

Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(4):847-853. Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Acute respiratory failure

necrolysis: a prospective noncomparative study doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09863.x in patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis: clinical

showing no benefit on mortality or progression. 28. Poizeau F, Gaudin O, Le Cleach L, et al. features and factors associated with mechanical

Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(1):33-36. doi:10.1001/ Cyclosporine for epidermal necrolysis: absence ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(1):118-128.

archderm.139.1.33 of beneficial effect in a retrospective cohort of doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31829eb94f

22. Chen J, Wang B, Zeng Y, Xu H. High-dose 174 patients-exposed/unexposed and propensity 34. Papo M, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Razazi K, et al.

intravenous immunoglobulins in the treatment of score-matched analyses. J Invest Dermatol. 2018; Renal replacement therapy during Stevens-Johnson

Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal 138(6):1293-1300. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2017.12.034 syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis:

necrolysis in Chinese patients: a retrospective 29. González-Herrada C, Rodríguez-Martín S, a retrospective observational study of 238 patients.

study of 82 cases. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20(6): Cachafeiro L, et al; PIELenRed Therapeutic Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(5):1370-1372. doi:10.1111/

743-747. Management Working Group. Cyclosporine use bjd.14934

23. Law EH, Leung M. Corticosteroids in in epidermal necrolysis is associated with an 35. Antoon JW, Goldman JL, Shah SS, Lee B.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal important mortality reduction: evidence from A retrospective cohort study of the management

necrolysis: current evidence and implications for three different approaches. J Invest Dermatol. and outcomes of children hospitalized with

future research. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49(3): 2017;137(10):2092-2100. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2017. Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal

335-342. doi:10.1177/1060028014560012 05.022 necrolysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(1):

24. Wang C-W, Yang L-Y, Chen C-B, et al; the Taiwan 30. Sekula P, Dunant A, Mockenhaupt M, et al; 244-250.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2018.05.024

Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reaction (TSCAR) RegiSCAR study group. Comprehensive survival

1190 JAMA Dermatology October 2021 Volume 157, Number 10 (Reprinted) jamadermatology.com

© 2021 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from jamanetwork.com by NANDHAKUMAR M on 12/08/2023

You might also like

- PM-3000 Section 1 To 7 ManualDocument52 pagesPM-3000 Section 1 To 7 Manualpablo100% (1)

- 2 The Crystal Chemistry of ZeolitesDocument48 pages2 The Crystal Chemistry of ZeolitesJohn YuNo ratings yet

- Tomatoes and Tomato Products - Nutritional, Medicinal and Therapeutic PropertiesDocument664 pagesTomatoes and Tomato Products - Nutritional, Medicinal and Therapeutic PropertiesAndreea MerţNo ratings yet

- Biomedicines 10 02105Document16 pagesBiomedicines 10 02105Fatimah AssagafNo ratings yet

- Nusantara Medical Science JournalDocument5 pagesNusantara Medical Science JournalfebifebriantyNo ratings yet

- Stevens Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal NecrolysisDocument7 pagesStevens Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal NecrolysisMiss AmyNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading - SSJ-TENDocument21 pagesJournal Reading - SSJ-TENReski Nursyifah HusainNo ratings yet

- SSJ ConvertDocument8 pagesSSJ ConvertHarryPascaRullianNo ratings yet

- Jurnal TEN JepangDocument15 pagesJurnal TEN JepanglinaNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument10 pagesResearch ArticlePratama Imanuel RawungNo ratings yet

- Original Article Retrospective Analysis of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Over A Period of 10 YearsDocument6 pagesOriginal Article Retrospective Analysis of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Over A Period of 10 YearssyalalaaalalaaaNo ratings yet

- Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions Related To Systemic AntibioticsDocument9 pagesSevere Cutaneous Adverse Reactions Related To Systemic AntibioticsajithloyolaNo ratings yet

- Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis and Stevens Johnson Syndrome: Our Current UnderstandingDocument8 pagesToxic Epidermal Necrolysis and Stevens Johnson Syndrome: Our Current UnderstandingjoyfullNo ratings yet

- Causes and Treatment Outcomes of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis in 82 Adult PatientsDocument8 pagesCauses and Treatment Outcomes of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis in 82 Adult PatientschechenoveliaNo ratings yet

- Malignant Otitis Externa: A Retrospective Analysis and Treatment OutcomesDocument5 pagesMalignant Otitis Externa: A Retrospective Analysis and Treatment OutcomesDini Mardiana UsmanNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Jaad 2019 05 096Document8 pages10 1016@j Jaad 2019 05 096JohnNo ratings yet

- Aair 2 123Document4 pagesAair 2 123Nandha KumarNo ratings yet

- Referensi Dari Saya No 8Document7 pagesReferensi Dari Saya No 8Kalsum MbNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument14 pagesPDFJardee DatsimaNo ratings yet

- Disease Characteristics in Patients With Juvenile-And Adult-Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Multi-Center Comparative StudyDocument8 pagesDisease Characteristics in Patients With Juvenile-And Adult-Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Multi-Center Comparative StudyDino GoncalvesNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of The Drug-Induced - I - I - Stevens-Johnson Syndrome - I - I - and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis in Indian PopulationDocument10 pagesA Systematic Review of The Drug-Induced - I - I - Stevens-Johnson Syndrome - I - I - and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis in Indian PopulationMiss AmyNo ratings yet

- Clinicoepidemiological Profile of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Drug Reaction: A Retrospective StudyDocument6 pagesClinicoepidemiological Profile of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Drug Reaction: A Retrospective StudyReffy AdhaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Dermatology ResearchDocument9 pagesJournal of Dermatology ResearchAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- Malignant Otitis Externa: A Retrospective Analysis and Treatment OutcomesDocument5 pagesMalignant Otitis Externa: A Retrospective Analysis and Treatment OutcomesiinknisaNo ratings yet

- Sjogren ReviewDocument11 pagesSjogren ReviewMariano AlbertalNo ratings yet

- Discoid Lupus Erythematosus: A Profile: Original ArticleDocument4 pagesDiscoid Lupus Erythematosus: A Profile: Original ArticleAngelin LigiantoNo ratings yet

- 956 3320 1 PBDocument5 pages956 3320 1 PBMelina JessicaNo ratings yet

- A Retrospective Study: Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal NecrolysisDocument9 pagesA Retrospective Study: Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal NecrolysisedisanjanaNo ratings yet

- Eritroderma EpidemiologyDocument6 pagesEritroderma EpidemiologyAhmad Ligar SuhermanNo ratings yet

- RF - Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A Treatment UpdateDocument2 pagesRF - Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A Treatment Updatedoc.kentoNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Stevens-Johnson's Syndrome and Toxic Epidermonecrolysis Patients in A Rural Based Medical College With An Emphasis On Steroid TherapyDocument6 pagesAnalysis of Stevens-Johnson's Syndrome and Toxic Epidermonecrolysis Patients in A Rural Based Medical College With An Emphasis On Steroid Therapywindawindut94No ratings yet

- (10920684 - Neurosurgical Focus) Predictors of Outcome of Subdural Empyema in ChildrenDocument6 pages(10920684 - Neurosurgical Focus) Predictors of Outcome of Subdural Empyema in ChildrenFatima RamirezNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2468912223000330 MainDocument37 pages1 s2.0 S2468912223000330 MainlauraNo ratings yet

- 2018 Severe Cutaneous Adverse Drug Reactions - Presentation, Risk Factors, and ManagementDocument9 pages2018 Severe Cutaneous Adverse Drug Reactions - Presentation, Risk Factors, and ManagementpablopabloortizortizNo ratings yet

- HSDCDocument5 pagesHSDCCelebre MualabaNo ratings yet

- BJD 12501Document10 pagesBJD 12501abdulariifNo ratings yet

- Kohanim 2016Document18 pagesKohanim 2016Cuiting FengNo ratings yet

- Characteristics, Treatment Patterns and Outcomes of Patients With Small Cell Lung Cancer-A Retrospective Single Institution AnalysisDocument4 pagesCharacteristics, Treatment Patterns and Outcomes of Patients With Small Cell Lung Cancer-A Retrospective Single Institution AnalysismaleticjNo ratings yet

- Fmed 08 636924 PDFDocument9 pagesFmed 08 636924 PDFMuhammad Nur Ardhi LahabuNo ratings yet

- Malignant External Otitis: Factors Predicting Patient OutcomesDocument6 pagesMalignant External Otitis: Factors Predicting Patient OutcomesYogaPriambudiNo ratings yet

- Management of Steven-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal NecrolysisDocument6 pagesManagement of Steven-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal NecrolysisRay PermanaNo ratings yet

- 2022 Clinical Features and Risk Factors of Mortality in Patients With Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy SyndromeDocument7 pages2022 Clinical Features and Risk Factors of Mortality in Patients With Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy SyndromeSafitri MuhlisaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal PatogenesisDocument6 pagesJurnal PatogenesisErmiati EmhyNo ratings yet

- Recurrence and Outcomes of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis in ChildrenDocument8 pagesRecurrence and Outcomes of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis in ChildrenReni OktaviaNo ratings yet

- mdw557 2Document7 pagesmdw557 2mfaddhilNo ratings yet

- Adjunctive Dexamethasone in Bacterial Meningitis: A Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient DataDocument10 pagesAdjunctive Dexamethasone in Bacterial Meningitis: A Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient DataMtst Trabalhadores Sem TetoNo ratings yet

- Gorantla Synthesis PaperDocument25 pagesGorantla Synthesis Paperapi-464986748No ratings yet

- Paraneoplastic Syndromes in Small Cell Lung CancerDocument11 pagesParaneoplastic Syndromes in Small Cell Lung CancerFebri Dwi HaryonoNo ratings yet

- Histo-Pathological Spectrum of Skin Lesions in Tertiary Care Centre: A Three Year StudyDocument6 pagesHisto-Pathological Spectrum of Skin Lesions in Tertiary Care Centre: A Three Year StudyIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A ReviewDocument6 pagesStevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A ReviewDede Rahman AgustianNo ratings yet

- HSDC CBC 2015Document5 pagesHSDC CBC 2015Bob sponjaNo ratings yet

- 878 Saturday, 17 June 2017: Scientific AbstractsDocument1 page878 Saturday, 17 June 2017: Scientific AbstractsDavid Gimenez RomeroNo ratings yet

- The Current Understanding of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal NecrolysisDocument14 pagesThe Current Understanding of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal NecrolysisKuro ChanNo ratings yet

- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: Management, Prognosis, and Long-Term Sequelae - UpToDate PDFDocument66 pagesStevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: Management, Prognosis, and Long-Term Sequelae - UpToDate PDFMatheus MeloNo ratings yet

- Systemic Sclerosis - 2015Document21 pagesSystemic Sclerosis - 2015XRobert17No ratings yet

- Hepatology - 2015 - Devarbhavi - Drug Induced Liver Injury Associated With Stevens Johnson Syndrome Toxic EpidermalDocument7 pagesHepatology - 2015 - Devarbhavi - Drug Induced Liver Injury Associated With Stevens Johnson Syndrome Toxic EpidermalSetyo SutantoNo ratings yet

- A Review of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Management in JapanDocument15 pagesA Review of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Management in Japanagus waelNo ratings yet

- Lancet Sclerosi MultiplaDocument15 pagesLancet Sclerosi MultiplaMr. LNo ratings yet

- Shift Work: A Risk Factor For Central Serous ChorioretinopathyDocument7 pagesShift Work: A Risk Factor For Central Serous ChorioretinopathysampleNo ratings yet

- Han 2017Document4 pagesHan 2017Alexandria Firdaus Al-farisyNo ratings yet

- NECROTIZINGDocument6 pagesNECROTIZINGphuong mai leNo ratings yet

- Yaghoubian 2007Document7 pagesYaghoubian 2007observer22No ratings yet

- Jon Krohn Metis Deep Learning 2017-05-01Document107 pagesJon Krohn Metis Deep Learning 2017-05-01Arnaldo Preso De LigaNo ratings yet

- Fitgurlmel's 365 Food Guide by Melissa AlcantaraDocument27 pagesFitgurlmel's 365 Food Guide by Melissa AlcantaraSinem YukselNo ratings yet

- Timing Calibration Harness AssemblyDocument5 pagesTiming Calibration Harness Assemblyflordeliz jimenez rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Standardization of Workmen HabitatDocument27 pagesStandardization of Workmen HabitatAbhinav AgarwalNo ratings yet

- The Hebrew and Greek Scriptures ComparedDocument805 pagesThe Hebrew and Greek Scriptures Comparedreha-kauba100% (1)

- Fault CodesDocument6 pagesFault CodesAnonymous zF4syKOrJNo ratings yet

- Summary Literature Review of Hydration of Cement"Document2 pagesSummary Literature Review of Hydration of Cement"MuhammadZAmjadNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Art HistoryDocument4 pagesAssignment 1 Art HistoryFarhanNo ratings yet

- OP100 OC100 User Program Manual R2Document32 pagesOP100 OC100 User Program Manual R2masroork_2No ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document15 pagesAssignment 2NOOR HALIZA BINTI ALI (HMELAKA)No ratings yet

- 08-03-17 EditionDocument28 pages08-03-17 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- 4000-5000 Hand 6 Udg Juni 2006 UKDocument24 pages4000-5000 Hand 6 Udg Juni 2006 UKZvonimir IvisicNo ratings yet

- Human Activity Detection Using Deep - 2-1Document8 pagesHuman Activity Detection Using Deep - 2-1Riky Tri YunardiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10: Frequency Response Techniques 1Document60 pagesChapter 10: Frequency Response Techniques 1CesarNo ratings yet

- 2007 - A Comprehensive and Critical Review of Dental Implant Prognosis in Periodontally Compromised Partially Edentulous PatientsDocument11 pages2007 - A Comprehensive and Critical Review of Dental Implant Prognosis in Periodontally Compromised Partially Edentulous PatientsLenny GrauNo ratings yet

- Han Longyu 200322255 MASC PSE Fall2015 PDFDocument139 pagesHan Longyu 200322255 MASC PSE Fall2015 PDFnajib amienNo ratings yet

- Power and Energy Calibration: Key Test and Measurement IssuesDocument4 pagesPower and Energy Calibration: Key Test and Measurement IssuesandriusNo ratings yet

- Trade of Export - ImportDocument9 pagesTrade of Export - ImportrahulvaliyaNo ratings yet

- BBS of All Pier Foundations of MAYARDocument16 pagesBBS of All Pier Foundations of MAYARAmanjot Singh0% (1)

- Federal Register / Vol. 88, No. 81 / Thursday, April 27, 2023 / Proposed RulesDocument236 pagesFederal Register / Vol. 88, No. 81 / Thursday, April 27, 2023 / Proposed RulesSimon AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Package FaultsDocument6 pagesPackage FaultsArunraj Arumugam100% (1)

- PollutionDocument4 pagesPollutionCt B ShieraNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument45 pagesUntitledaina ainaNo ratings yet

- MSW Report PDFDocument98 pagesMSW Report PDFSupritha KNo ratings yet

- Wolverton Chapter 25 Photodynamic TherapyDocument9 pagesWolverton Chapter 25 Photodynamic TherapyNahas NazarNo ratings yet

- Sohbi Kohgei - Solar Power System Proposal (Toshiba325W)Document4 pagesSohbi Kohgei - Solar Power System Proposal (Toshiba325W)Jeffcaster ComelNo ratings yet

- Coffee Landscapes Shaping The AnthropoceneDocument15 pagesCoffee Landscapes Shaping The AnthropocenejulianmorNo ratings yet