Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Cinematic Novel Tracking A Concept

The Cinematic Novel Tracking A Concept

Uploaded by

Bilal B'oOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Cinematic Novel Tracking A Concept

The Cinematic Novel Tracking A Concept

Uploaded by

Bilal B'oCopyright:

Available Formats

THE CINEMATIC NOVEL: TRACKING A CONCEPT

Author(s): Steven G. Kellman

Source: Modern Fiction Studies , Autumn 1987, Vol. 33, No. 3, SPECIAL ISSUE:

NARRATIVE THEORY (Autumn 1987), pp. 467-477

Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26282386

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to Modern Fiction Studies

This content downloaded from

197.29.130.74 on Fri, 22 Sep 2023 17:39:57 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE CINEMATIC NOVEL: TRACKING A CONCEPT

rrfr

Steven G. Kellman

Just as in the 1960's, when students and critics

alike were calling just about every important

work "existentialistic, " there now seems to be

a run on the term "cinematic." There is a

danger that, like the term "existentialistic,"

the term "cinematic" will wear out from

overuse and misuse. (Eidsvik 120)

When Virginia Woolf drolly proclaimed that "in or about December,

1910, human character changed" ("Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown" 320),

it is doubtful that she was thinking of D. W. Griffith. In late 1910, the

director had just moved his production company to Hollywood and made

His Trust, Griffith's first two-reeler and one of several works in which

he was inventing a syntax for the infant medium. Woolf was not enamored

of the movies, though they would reflect, embody, and shape precisely

that revolution in consciousness that she associated with modernism and

with the novel. The history of cinema is congruent with the history of

the modern novel, as it is with the development of the airplane, the

Modern Fiction Studies, Volume 33, Number 3, Autumn 1987. Copyright © by Purdue Research Foundation.

All rights to reproduction in any form reserved.

467

This content downloaded from

197.29.130.74 on Fri, 22 Sep 2023 17:39:57 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

automobile, the radio, the skyscraper, and even the zipper. Yet not nearly

as much sense and nonsense have been written about cinematic radios or

novelistic zippers as has been about cinematic novels.

Several generations of critics have taken it for granted that ut cinema

poesis, that literature is instructively analogous to film. Whether in em

pirical studies of works by such authors as Cendrars, Dos Passos, Malraux,

Robbe-Grillet, or Kosinski, in analyses of adaptations and novelizations,

or in comparatist theories of the relationships between literature and the

other arts, the term cinematic novel has become a rhetorical commonplace,

as if there were no question about what is meant by cinema and what

is meant by novel. There is such persistent but conflicting testimony about

this bizarre hybrid born in the twentieth century that, like the blind man

and the elephant, it is possible that we would not be able to recognize

a cinematic novel if we saw one.

In 1907, just four years after the first sustained narrative film, Edwin

S. Porter's The Great Train Robbery, Henri Bergson was articulating the

modernist conception of mind as a function of movement and continuity.

He explicitly drew upon the recent technology of motion pictures to il

lustrate his theory, as if to think is to operate a cerebral movie projector.

Qu'il s'agisse de penser le devenir, ou de l'exprimer, ou même de le percevoir, nous ne

faisons guère autre chose qu'actionner une espèce de cinématographe intérieur. On résumerait

donc tout ce qui précède en disant que le mécanisme de notre connaissance usuelle est de nature

cinématographique. (753)

A decade earlier, it was William James who, in Principles of Psychology

(1890), had coined the term stream of consciousness to describe a new sense

that the mind functions in and on flux. James did not use the metaphor of

movies, but for an increasingly urban population a rapid sequence of still

photographs would soon be more familiar than his image of a stream.

And in describing these innovative novels that incorporated the insights

of the elder James and of Bergson, others have frequently made com

parisons with film. In 1932, for example, Joseph Warren Beach explained:

A more enlightening analogy is perhaps that of the moving picture, especially the sort cultivated

in Germany, France, and Russia, with its generous use of cut-back, of symbolic themes,

of dissolving views, all meant to give the picture a wider and richer significance than that

of a mere story told in chronological sequence. It is probable that the moving picture has

had a very strong influence on the stream-of-consciousness technique. (525)

And in his 1968 book-length study of that technique, Robert Humphrey

evokes specifically cinematic devices:

The ingenious minds of the writers we have been considering, like their contemporaries

in the sister arts, especially in the cinema, found techniques which were devised to project

the duality and the flux of mental life. Montage, with its function of presenting either more

than one object or more than, one time simultaneously, was especially adaptable to fiction.

468 MODERN FICTION STUDIES

This content downloaded from

197.29.130.74 on Fri, 22 Sep 2023 17:39:57 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The corollary devices of "flashback," "fade-out," and "slow-up" proved useful adjuncts

to montage and free association. (121)

By 1987, cinema has been accepted into the sorority of the sister arts,

has in fact come to dominate discussions of its kin. When Arnold Hauser

came to the twentieth century in his ambitious 1952 study The Social History

of Art, he dubbed it "The Film Age" and argued that, because of its

treatment of time, cinema is an apt synecdoche for all the modern arts:

one has the feeling that the time categories of modern art altogether must have arisen from

the spirit of cinematic form, and one is inclined to consider the film itself as the stylistically

most representative, though qualitatively perhaps not the most fertile genre of contemporary

art. (939-940)

In his 1960 book Rococo to Cubism in Art and Literature, Wylie Sypher similar

ly claimed that cinema represents "the primary technique of the twen

tieth century" (184). Gertrude Stein saw the early part of the century

as "undoubtedly the period of the cinema and series production." In 1935,

she said of The Making of Americans, a book she completed in 1908, before

ever seeing a film: "I was doing what the cinema was doing, I was making

a continuous succession of the statement of what that person was until

I had not many things but one thing" (177). Because of the influence

of Dos Passos, Faulkner, Hemingway, and Steinbeck, Claude-Edmonde

Magny designated the post-World War Two era L'Age du roman américain.

Yet what she found so compelling about these American novelists was

precisely their fascimile of cinematic construction. Film may or may not

have dominated Western culture, but its vocabulary has certainly pervaded

discussions of the other arts, particularly prose fiction. It has not always

been in the interests of lucidity.

In 1924, an American critic, Gilbert Seldes, was already both extol

ling and deploring the influence of film on the novel. Claiming that cinema

has had a salutary effect on French literature but a pernicious one on

American, he declared: "the cinema influence in literature in French is

almost exactly opposite to what it is here. There it seems to make for

brevity, hardness, clarity, brilliance"; in contrast are "those characteristic

sloppinesses, which American authors are beginning to blame on the

movies" (383). Surely the clarity and brilliance of Seldes's observation

are dependent on precisely what he means not only by "influence," but

by "cinema" as well.

In 1918, Virginia Woolf attacked Compton Mackenzie's new novel

The Early Life and Adventures of Sylvia Scarlett as "a book of cinema." She

explains that "as in a cinema, one picture must follow another without

stopping, for if it stopped and we had to look at it we should be bored"

(Woolf, "Movie Novel" 84). Woolf s animosity toward books of cinema

seems based on a mistrust of eidetic literature, as she noted graphically

a few years later:

CINEMATIC NOVEL 469

This content downloaded from

197.29.130.74 on Fri, 22 Sep 2023 17:39:57 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

We can say for certain that a writer whose writing appeals mainly to the eye is a bad writer;

that if in describing, say, a meeting in a garden he describes roses, lilies, carnations, and

shadows on the grass, so that we can see them, but allows to be inferred from them ideas,

motives, impulses, and emotions, it is that he is incapable of using his medium for the

purposes for which it was created, and is as a writer a man without legs. (Woolf, "Pictures"

174).

Yet Woolf s distaste for the new century's putatively representative medium

and for novels that ape it has not prevented critics from describing her

own novels as "cinematic." Robert Humphrey, for one, makes a lengthy

case for analyzing the exposition of Mrs. Dalloway as if it were a "roving

camera" (58).

James Joyce, in 1909, attempted unsuccessfully to open the first movie

theater in Dublin, and Wylie Sypher contends that "Ulysses illustrates

the montage principle in its widest application" (285). But Marcel Proust,

like Woolf, was unsympathetic to analogies between fiction and film.

Toward the end of A la recherche du temps perdu, its narrator realizes that

a mere linear continuity is not the triumphal synoptic vision toward which

he, as a latent novelist, has been aspiring:

Quelques-un voulaient que le roman fût une sorte de défile cinématographique des choses.

Cette conception était absurde. Rien ne s'éloigne plus de ce que nous avons perçu en réalité

qu'une telle vue cinématographique. (882-883)

Nevertheless, Proust, too, has been described as "cinematic," as in Arnold

Hauser's enthusiastic survey of the modernist masters as cinéastes by other

means:

The discontinuity of the plot and the scenic development, the sudden emer

and moods, the relativity and the inconsistency of the time-standards,

in the works of Proust and Joyce, Dos Passos, and Virginia Woolf of th

and interpolations of the film, and it is simply film magic when Proust br

which may lie thirty years apart, as closely together as if there were only

them. (944)

John Updike subtitled Rabbit, Run "A Movie" and t

viewer of his attempt at "an equivalent of the cinemati

tion" (Plimpton 447-448). The belief that "each clipped

prepositional phrase, is like a new frame in a strip of f

Levin to characterize Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms as a

"cinematographic presentation" (Contexts 159). Another critic says

of Thomas Pynchon in Gravity's Rainbow. "He incorporates cinematic

techniques into the texture itself so that the novel is like a movie" (Clerc

104). With producer Samuel Goldwyn, the simile seems founded more

on mood than on specific techniques: "Some novels read like scenarios.

Look at Rebecca\ Rebecca reads like a scenario. But not Wuthering Heights"

(Bluestone 91). The anonymous reviewer for the Times Literary Supplement

who described a scholarly book on the Civil War as "couched in the most

highly coloured cinematic prose" apparently liked neither cinema nor the

470 MODERN FICTION STUDIES

This content downloaded from

197.29.130.74 on Fri, 22 Sep 2023 17:39:57 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

volume {The Alabama Incident 754).

Such remarks could be multiplied at great length, but remarks are

not analysis. A thorough attempt to disentangle the two terms of the

analogy would end up cross-cutting the history of the novel with the history

of the cinema. Obviously, "cinematic" does not mean the same thing

in 1987 as it did in 1950, before wide-screen technology, as it did in 1940,

before color became commonplace, as it did in 1925, before movies could

talk, or as it did in 1900, before cameras became mobile. It is undeniable

that novels are being written differently now than they were before

Lumière—and, successively, Griffith, Welles, Bergman, or Godard. Ac

cording to whether the paradigm for film is documentary, fictional, or

animated, Expressionist, Surrealist, or Neorealist, avant-garde, or populist,

the meaning of cinematic novel will be quite different. As we have seen,

the term can be applied pejoratively, honorifically, or neutrally. It can

be used to describe a book's style, structure, or content.

When an anonymous reviewer for the Times Literary Supplement wrote

of Edna Ferber's American Beauty (1931): "The book will naturally lend

itself particularly well to the screen: it has plenty of drama and is steeped

in romance" (862), cinema was being conceived as simply the repository

of gaudy plots. But there is also a sizable class of novels, most notably

Nathanael West's The Day of the Locust and F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Last

Tycoon, that are centrally and explicitly about moviemaking. To call these

cinematic novels, however, is to compound the confusion. Merely because

they depict film production without themselves necessarily taking on the

characteristics of a film (whatever those are) makes them as much

"cinematic" as a biography of a dietitian is "nutritional."

Nor are novelizations, the transposition of a work from screen to page,

usually to capitalize on a movie's current popularity, necessarily cinematic.

The early movie industry turned to the nineteenth-century novel for a

ready supply of unprotected raw material, adapting many canonized texts

several times each. As cinema gained influence, respectability, and aesthetic

sophistication, as it came to seem the dominant cultural medium, the

process was reversed, and the movie began to precede the book. Love Story

(1970), whose author Erich Segal was creating the screenplay and the

novel simultaneously, perhaps marks a turning point, at least in

Hollywood. Thenceforth, with blockbusters like E. T., Gremlins, and Raiders

of the Lost Ark, there is no doubt about which medium is primary. Noveliza

tions were not invented in the 1960s, but The Shooting of Dan McGrew

(1924), The Great Divide (1925), and Wings (1927) are singular cases and

as novelizations did not exist in the same cultural economy as Rocky, Satur

day Night Fever, and Star Trek do today. In any case, simply because they

drew their plots and characters from a film does not make these books

"cinematic" any more than the multiple screen versions of Anna Karenina

or David Copperfield are perforce "novelistic."

CINEMATIC NOVEL 471

This content downloaded from

197.29.130.74 on Fri, 22 Sep 2023 17:39:57 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Stendhal's famous recipe for realistic fiction as a mobile mirror, "un

miroir qu'on promène le long d'un chemin," seems to anticipate a track

ing camera. And, at least since Sergei Eisenstein's discussion of Dickens

as his technical mentor (195-255), critics have seized on numerous pre

Edisonian authors as cinéastes avant la lettre. Frank O'Connor, for example,

analyzes how, in order to describe the town in The Mayor of Casterbridge,

Thomas Hardy devised high angle shots, fades, tracking, and close-ups

(245-246). Harry Levin says of the author's task in paring Madame Bovary

down from 3,600 manuscript pages: "The demiurgic function of reducing

that mass to its present form might be compared to the cutting of a film,

and rather than speak of Flaubert's 'composition' in the pictorial sense,

we might refer, in kinetic terms, to montage" (Gates 261). One critic,

Paul Léglise, has even devoted an entire volume to The Aeneid as a

proto-movie.

But it is preeminently as an emblem of modernity that authors first

hailed the cinema. The Futurists, in particular, celebrated motion pic

tures as " the expressive medium most adapted to the complex sensibility of a Futurist

artist." For them, the only way that the book, "static companion of the

sedentary, the nostalgic, the neutralist," can survive is by assimilating

the vibrant qualities of the new art—"antigraceful, deforming, impres

sionistic, synthetic, dynamic, free-wording" (Marinetti 207-208). Blaise

Cendrars, an enigmatic Swiss poet, filmmaker, and novelist who flirted

with several avant-garde groups, was intoxicated with the possibilities of

cinema. In Les Confessions de Dan Yack (1929), a novel he dedicated to

Abel Gance, Cendrars has his title character tell a movie actress:

"L'équilibre est dans le mouvement ... si tu ne bouges pas, tu poses.

Tout est là. C'est tout le secret du ciné" (5: 266). And Cendrars attempted

to translate this secret of perpetual motion into the form of his writing.

One result was the 1925 novel L'Or, about which the critic for Les Nouvelles

Littéraires wrote:

C'est écrit avec une économie voulue, tout comme un scénario de cinéma, scène par scène,

au présent d'un indicatif rapide, à l'usage du metteur en scène. L'histoire est menée droit

au but, par un homme qui connaît à merveille tous les effets des projections sur l'écran

cérébral et sait rendre l'anecdote uniquement visuelle. C'est le plus beau des films, à la

meilleure manière de William Hart, avec un grand souffle d'épopée sur de grands paysages.

(Serstevens 1)

Reviewing the English translation, Sutter's Gold, The New York Times critic

also found Cendrars' novel "cinematic," but excessively so; assailing "the

movie style of the text," he claimed the book "has most of the worst

faults of the movie caption" (Broch 4).

Apart from the intrinsic qualities of the medium, what especially ex

cited the European avant-garde was the social context of movie consump

tion. For them, it was the consummate populist art. In his 1926 essay

"L'ABC du cinéma," Cendrars provides an apocalyptic vision of global

472 MODERN FICTION STUDIES

This content downloaded from

197.29.130.74 on Fri, 22 Sep 2023 17:39:57 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

cataclysm through the universal appeal of film:

A la même heure, dans toutes les villes du monde, la foule qui sort des cinémas, qui se

répand dans les rues comme un Seing noir, qui comme une bête puissante allonge ses mille

tentacules et d'un tout petit effort écrase les palais, les prisons. (6: 24)

Just as modernist art was becoming more rarefied, addressed to the happy

few, and most adept at rendering private moments of awareness, com

mercial film was demotic, public, and unrefined. Perhaps it is a nostalgie

de la boue that accounts in part for the power that this vulgar entertain

ment exerted over the cultural renegades of high modernism. In any case,

it suggests that one meaning of cinematic novel would be a rejection of

hermetically perfect prose in favor of a contribution to the newly emerg

ing mass culture.

Eisenstein and other Russian theorists like Pudovkin, Kuleshov, and

Vertov infectiously argued that the essence of cinematic art is montage:

the arrangement of discrete frames to create a visual rhythm. A cinematic

novel, then, would be one that is organized as if separate chapters,

paragraphs, or sentences were written and then edited into nonlinear

patterns. However, montage theory was vigorously challenged following

World War Two—in France by the Cahiers du cinéma group under André

Bazin and in Italy by the Neorealists. Excessive cutting was attacked as

being factitious and manipulative. In place of montage, the basis of a

free, imaginative cinema was proclaimed to be mise-en-scène—design within

each individual frame, long takes, and deep focus. However, it is a curious

fact that, though the early Russians' exclusive preoccupation with mon

tage as the foundation of film art has long since been abandoned, discus

sions of the cinematic novel persist in taking montage as the model for what

novels constructed like movies should be like. Edward Murray, for

example, argues that In Cold Blood was an unsuccessful movie, ironically,

because it attempted to adapt a novel that was already consummately

"cinematic." And what he means by that is that Truman Capote has

found a perfect literary equivalent to montage: "It seems doubtful whether

any serious writer before Capote ever applied the method of parallel editing

so consistendy throughout the length of an entire novel" (132).

Jerzy Kosinski discusses his own 1968 novel Steps, organized as a se

quence of narrative fragments, as cinematic because it is overtly edited

and as modern because it is cinematic: "Montage reflects the modern

thought process" (15). Long after Eisenstein, montage continues to be

the paradigm for film in analogies between it and prose fiction, perhaps

because it is simply much easier to find a verbal equivalent for it than

for mise-en-scène. It is also true that, technically and stylistically, literary

movements are not exactly synchronized with cinematic ones.

The most elementary observations on film and literature begin with

the realization that the medium of the first is images, whereas the medium

CINEMATIC NOVEL 473

This content downloaded from

197.29.130.74 on Fri, 22 Sep 2023 17:39:57 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

of the second is words. Some of the ambition to create cinematic novels

must surely be a legacy of Symbolist impatience with mere words, each

worth but .001 percent of a picture. The same impulse responsible for

Imagist poetry and invisible authors urged novelists to aspire to the visual

presence of film, to attempt to abandon concepts for percepts, telling for

showing. When one critic praises Kosinski's books as "cinematic," he

means that they provide an experience that is neither mediated nor

meditated:

The Painted Bird and Steps are remembered for their visual impact, the fully dramatized land

scapes within which the reader sees everything and is told nothing. The fantastic visual

sweep involves the reader almost as immediately as when he is viewing a film: we are stunned

by the savage brutality while at the same time admiring the perceptual beauty of control that

the writer has brought to his subject. (Coale 370)

The illusion of immediacy is also a central concern of the French

New Novelists, and of Alain Robbe-Grillet in particular. Much of le nouveau

roman must be understood in terms of its champions' veneration, emula

tion, and adaptation of cinematic techniques. Robbe-Grillet and

Marguérite Duras have even become filmmakers. Robbe-Grillet's is an

art of appearances, of surfaces, and a vision of cinema as the most deictic

of media guides his writing. Where literature is an abstraction, images

assert a presence; and where words establish a temporal continuum, film

creates an eternal present. In his Preface to L'Année dernière à Marienbad,

Robbe-Grillet contends that narrative approaches the condition of film

to the extent that it is able to collapse preterite and future into a con

tinuous hie et nunc.

La caractéristique essentielle de l'image est sa présence. Alors que la littérature dispose de

toute une gamme de temps grammaticaux, qui permet de situer les événements les uns

par rapport aux autres, on peut dire que, sur l'image, les verbes sont toujours au présent

(ce qui rend si étranges, si faux, ces films "racontés" des publications spécialisées, où l'on

a rétabli le passé simple cher au roman classique!): de toute évidence, ce que l'on voit sur

l'écran est en train de se passer, c'est le geste même qu'on nous donne, et non pas un rapport

sur lui. (L'Année 15)

In annihilating history and eluding signification, Robbe-Grillet's doctrine

is reminiscent of the mute behaviorism Claude-Edmonde Magny had at

tributed to the cinematic American novels of the 1920s and 1930s. And

if the primary dimension of film is space and that of prose fiction is time,

then perhaps insistence by twentieth-century authors on an analogy be

tween novel and cinema is yet another formulation of Joseph Frank's thesis

on "Spatial Form in Modern Literature."

The existence of a cinematic novel demands delicate equilibrium. If too

much weight is placed on the first term, the adjective becomes a substan

tive, and the pen is supplanted by a camera. Such was the case with

Robbe-Grillet in L'Immortelle, Trans-Europ express, and L'Homme qui ment.

He published a text for L'Immortelle, as a "ciné-roman," and in its Preface

474 MODERN FICTION STUDIES

This content downloaded from

197.29.130.74 on Fri, 22 Sep 2023 17:39:57 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

he makes that genre, congenitally subordinate to screen images, seem like

an elegant version of novelization: "L'oeuvre, c'est le film, tel qu'on peut

le voir et l'entendre dans un cinéma" (7). The converse of "ciné-roman,"

an attempt at novelistic cinema, would be Alexandre Astruc's notion of

"caméra-stylo." The tendency to regard filmmakers—usually directors—as

"authors," the triumph of François Truffaut's "politique des auteurs,"

is yet a further correlation of cinema and novel, this time not to em

phasize matter, technique, or social context, but rather creative

responsibility.

Perhaps the most fundamental issue in likening novel to film is an

ontological one. Is cinema the child of Lumière or of Méliès, a recording

device or a vehicle of fantasy? To begin with Siegfried Kracauer's premise

that film is most instinctively a "redemption of physical reality" is to

raise very different expectations of a cinematic novel than to begin with

Suzanne Langer's notion that film is "the mode of dream" (412). Of

course, there are also oneiric and naturalistic schools of novel-writing.

Numerous theorists have stepped forward as the new Lessing, offer

ing us lessons in sorting out the distinctive features of cinema and novel.1

Yet as long as these remain the two dominant arts of our culture, it is

unlikely that the cinematic novel, a creature both mythical and protean,

will become extinct. Critics will continue to confound the two terms of

the analogy and their readers.

1See: Morris Bcja, Film and Literature: An Introduction. New York: Longman, 1979; Keith Cohen,

Film and Fiction. New Haven: Yale UP, 1979; John Harrington, Film And/As Literature. Englewood Cliffs:

Prentice, 1977; Christian Metz, Essais sur la signification du cinéma. Paris: Klincksieck, 1968; Edward

Murray, The Cinematic Imagination: Writers and the Motion Pictures. New York: Ungar, 1972; Robert Richard

son, Literature and Film. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1969; Alan Spiegel, Fiction and the Camera Eye: Visual

Consciousness in Film and the Modern Novel. Charlottesville: U of Virginia P, 1976; Geoffrey Wagner, The

Novel and the Cinema. Rutherford, NY: Fairleigh Dickinson UP, 1975; and Marie-Claire Ropars

Wuilleumier, De la littérature au cinéma: génèse d'une écriture. Paris: Colin, 1970.

CINEMATIC NOVEL 475

This content downloaded from

197.29.130.74 on Fri, 22 Sep 2023 17:39:57 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WORKS CITED

Rev. of The Alabama Incident, by Kenneth Poolman. Times Literary Suppl

Dec. 1958: 754.

Rev. of American Beauty, by Edna Ferber. Times Literary Supplement 5 Nov. 1931: 862

Beach, Joseph Warren. The Twentieth Century Novel: Studies in Technique. New York

Appleton, 1932.

Bergson, Henri. "L'Evolution creatrice." Oeuvres. Ed. André Robinet. Paris:

Presses universitaires de France, 1963. 487-809.

Bluestone, George. Novels into Film. Berkeley: U of California P, 1971.

Broch, H. I. " 'Gold!! Gold!' They Cried in '49." New York Times Book Review

3 Oct. 1926: 4.

Cendrars, Blaise. Les Confessions de Dan Yack. Vol. 5 of Oeuvres complètes.

Ed. Nino Frank. Paris: Club français du livre, 1969. 16 vols.

"L'ABC du cinéma." Aujourd'hui. Vol. 6 of Oeuvres complètes. Ed. Nino

Frank. Paris: Club français du livre, 1969. 16 vols. 20-24.

Clerc, Charles. "Film in Gravity's Rainbow." Approaches to Gravity's Rainbow. Ed.

Charles Clerc. Columbus: Ohio State UP, 1983. 103-151.

Coale, Samuel. "The Cinematic Self of Jerzy Kosinski." Modern Fiction Studies

20 (1974): 359-370.

Eidsvik, Charles. "Demonstrating Film Influence." Literature/Film Quarterly 1 (1973):

113-121.

Eisenstein, Sergei. Film Form. Ed. and trans. Jay Leyda. New York: Harcourt,

1949.

Frank, Joseph. "Spatial Form in Modern Literature." The Widening Gyre: Crisis

and Mastery in Modem Literature. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1963. 3-36.

Hauser, Arnold. The Social History of Art. Vol. 2. New York: Knopf, 1951. 2 vols.

Humphrey, Robert. Stream of Consciousness in the Modern Novel. Berkeley: U of

California P, 1968.

Kosinski, Jerzy. The Art of the Self: Essays à Propos "Steps." New York: Scientia

Factum, 1968.

Kracauer, Siegfried. Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality. New York:

Oxford UP, 1960.

Langer, Susanne. Feeling and Form: A Theory of Art. New York: Scribner's, 1953.

Léglise, Paul. Une Oeuvre de pré-cinéma: L'Enéide: essai d'analyse filmique du premier

chant. Paris: Debresse, 1958.

Levin, Harry. Contexts of Criticism. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1957.

. The Gates of Horn: A Study of Five French Realists. New York: Oxford UP, 1963.

Marinetti, F. T., Bruno Corra, Emilio Settimelli, et. al. "The Futurist Cinema

1916." Futurist Manifestos. Trans. R. W. Flint. Ed. Umbro Apollonio. New

York: Viking, 1973. 207-219.

Murray, Edward. "In Cold Blood: The Filmic Novel and the Problem of Adapta

tion." Literature/Film Quarterly 1 (1973): 132-137.

O'Connor, Frank. The Mirror in the Roadway: A Study in the Modern Novel. New

York: Knopf, 1964.

Plimpton, George, ed. "John Updike." Writers at Work: The Paris Review Inter

views. New York: Penguin, 1977. 425-454.

476 MODERN FICTION STUDIES

This content downloaded from

197.29.130.74 on Fri, 22 Sep 2023 17:39:57 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Proust, Marcel. A la recherche du temps perdu. Eds. Pierre Clarac and André Ferré.

Vol. 3. Paris: Gallimard, 1954. 3 vols. 689-1048.

Robbe-Grillet, Alain. L'Année dernière à Marienbad. Paris: Minuit, 1961.

L'Immortelle. Paris: Minuit, 1963.

Seldes, Gilbert. "The Cinema Novel." The Seven Lively Arts. New York: Harper,

1924. 383-392.

Serstevens, A. T. "Du 'Transsibérien' à Moravagine': Cendrars, poète et roman

cier." Les Nouvelles littéraires 26 (Sept. 1926): 1.

Stein, Gertrude. "Portraits and Repetition." Lectures in America. Boston: Beacon,

1957. 165-206.

Sypher, Wylie. Rococo to Cubism in Art and Literature. New York: Vintage, 1960.

Woolf, Virginia. "Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown." Collected Essays, Vol. 1. New

York: Harcourt, 1950. 4 vols. 319-337.

"The 'Movie' Novel." Contemporary Writers. New York: Harcourt, 1965.

82-84.

"Pictures." The Moment and Other Essays. New York: Harcourt, 1948.

173-178.

477

This content downloaded from

197.29.130.74 on Fri, 22 Sep 2023 17:39:57 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Pre-Intermediate Achievement Test 1 (Units 1-3) : Listening GrammarDocument1 pagePre-Intermediate Achievement Test 1 (Units 1-3) : Listening GrammarAndrewKanischev0% (1)

- Miriam Hansen's Introduction Kracauer's "Theory of Film"Document20 pagesMiriam Hansen's Introduction Kracauer's "Theory of Film"dbluherNo ratings yet

- Books in Motion: Adaptation, Intertextuality, AuthorshipDocument24 pagesBooks in Motion: Adaptation, Intertextuality, Authorshipjohnsonk47No ratings yet

- L'Année Dernière À Marienbad (Last Year in Marienbad) BFI Film ClassicsDocument35 pagesL'Année Dernière À Marienbad (Last Year in Marienbad) BFI Film Classicsgrão-de-bico100% (5)

- GeneralDocument29 pagesGeneralLory LoredanaNo ratings yet

- RMA Thesis PDFDocument120 pagesRMA Thesis PDFtcmdefNo ratings yet

- Bordwell ModernismDocument7 pagesBordwell ModernismMasha ShpolbergNo ratings yet

- Józsa István - Kortárs Művészet: Immortal Literature: Film Adaptations and Interpretations of Oscar Wilde'SDocument19 pagesJózsa István - Kortárs Művészet: Immortal Literature: Film Adaptations and Interpretations of Oscar Wilde'SDeeJay MussexNo ratings yet

- Novel To FilmDocument28 pagesNovel To FilmEmily BarrettNo ratings yet

- Unusual FootprintsDocument17 pagesUnusual FootprintsSomeswar BhowmikNo ratings yet

- Siegfried Kracauer - Photography (1927)Document17 pagesSiegfried Kracauer - Photography (1927)Paul NadeauNo ratings yet

- 12 Film and Modernist Literature: 1 Introduction: Early Film HistoryDocument9 pages12 Film and Modernist Literature: 1 Introduction: Early Film HistorySherryNo ratings yet

- דיסאוטופיהDocument21 pagesדיסאוטופיהsabagraniNo ratings yet

- Baron FLAUBERTJOYCEVISION 2008Document27 pagesBaron FLAUBERTJOYCEVISION 2008Liane BencuyaNo ratings yet

- A Nissim OvaDocument21 pagesA Nissim OvaTaibur RahamanNo ratings yet

- Return of The Gaze AMADDocument27 pagesReturn of The Gaze AMADMani SharpeNo ratings yet

- Women at The Keyhole - MayneDocument18 pagesWomen at The Keyhole - MayneRebecca EllisNo ratings yet

- Comic Adaptations of Literary TextsDocument22 pagesComic Adaptations of Literary TextsOanaNo ratings yet

- Autobiografia - Autobiography and PostmemoryDocument10 pagesAutobiografia - Autobiography and Postmemorynueva_madreNo ratings yet

- Michel Mourlet - On A Misunderstood ArtDocument34 pagesMichel Mourlet - On A Misunderstood ArtGabriel CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Keyishian - Shakespeare and Movie Genre - 2007 PDFDocument15 pagesKeyishian - Shakespeare and Movie Genre - 2007 PDFullyot0% (1)

- Hansen, Early KracauerDocument31 pagesHansen, Early Kracauersfisk004821No ratings yet

- Journal of Visual Culture: Translating The Essay Into Film and Installation Nora M. AlterDocument14 pagesJournal of Visual Culture: Translating The Essay Into Film and Installation Nora M. AlterLais Queiroz100% (1)

- Elsaesser - Bazin Half CenturyDocument11 pagesElsaesser - Bazin Half Centurymoran.francis.thomasNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:30:02 UTCDocument19 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:30:02 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- 1.2 Literature and Motion PicturesDocument31 pages1.2 Literature and Motion PicturesBogles Paul FernandoNo ratings yet

- Porter or AmbivalenceDocument16 pagesPorter or AmbivalenceerezperyNo ratings yet

- The End of History Through The Disclosure of Fiction: Indisciplinarity in Miguel Gomes'S Tabu (2012)Document30 pagesThe End of History Through The Disclosure of Fiction: Indisciplinarity in Miguel Gomes'S Tabu (2012)Esteban BrenaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Book Impure CinemaDocument14 pagesIntroduction To The Book Impure CinemaNéstor Felipe Espitia CabrejoNo ratings yet

- Film EssayDocument8 pagesFilm EssayWesley SnipesNo ratings yet

- Hake GirlsCrisis 1987Document19 pagesHake GirlsCrisis 1987X1ndyNo ratings yet

- Hamish Ford The Return of The 1960s Modernist CinemaDocument16 pagesHamish Ford The Return of The 1960s Modernist CinemaleretsantuNo ratings yet

- Krauss ReinventingMedium 1999Document18 pagesKrauss ReinventingMedium 1999annysmiNo ratings yet

- Hansen Blue FlowerDocument47 pagesHansen Blue FlowerPedro Pérez DíazNo ratings yet

- 00-John Dos Passos Use of Film Technique in Manhattan Transfer & The 42nd ParallelDocument10 pages00-John Dos Passos Use of Film Technique in Manhattan Transfer & The 42nd ParallelRania Haj YoussefNo ratings yet

- Thomas Hardy and Cinematographic FormDocument10 pagesThomas Hardy and Cinematographic FormPaul MathewNo ratings yet

- Utkal Historical Research Journal, ISSN: 0976-2132 Vol.-34 (XXVIII), 2021Document4 pagesUtkal Historical Research Journal, ISSN: 0976-2132 Vol.-34 (XXVIII), 2021sajad2rasheedNo ratings yet

- From The Cinema of Poetry To The Poetry of CinemaDocument7 pagesFrom The Cinema of Poetry To The Poetry of CinemaTom KonyvesNo ratings yet

- The Use and Abuse of Cinema: German Legacies from the Weimar Era to the PresentFrom EverandThe Use and Abuse of Cinema: German Legacies from the Weimar Era to the PresentNo ratings yet

- Nagib DeathaCinema 2020Document25 pagesNagib DeathaCinema 2020Ravinder Singh BhullarNo ratings yet

- Orson Welles's The Trial Film Noir and The Kafkaesque - J. AdamsDocument19 pagesOrson Welles's The Trial Film Noir and The Kafkaesque - J. AdamsTheaethetus0% (1)

- Camera StyloDocument4 pagesCamera StyloFröken SverigeNo ratings yet

- Amad, Paula-Cine-ethnographyDocument5 pagesAmad, Paula-Cine-ethnographyoscarguarinNo ratings yet

- The Birth of A New AvantDocument4 pagesThe Birth of A New AvantBogdan PetrovanNo ratings yet

- L WallisDocument80 pagesL WallisAnna CiceroNo ratings yet

- Russian Film Director Screenwriter Actor Montage Sergei EisensteinDocument8 pagesRussian Film Director Screenwriter Actor Montage Sergei EisensteinPriyam ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Duke University Press and New German Critique Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To New German CritiqueDocument47 pagesDuke University Press and New German Critique Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To New German Critiquemartin19877891No ratings yet

- Alexander Kluge - Senses of CinemaDocument15 pagesAlexander Kluge - Senses of CinemaGawan FagardNo ratings yet

- THE CINEMA OF DAVID CRONENBERG (Prikaz Knjige)Document4 pagesTHE CINEMA OF DAVID CRONENBERG (Prikaz Knjige)BulbulNo ratings yet

- FilmInk Page 3Document1 pageFilmInk Page 3FstopFitzgeraldNo ratings yet

- Haptical CinemaDocument30 pagesHaptical CinemagreggflaxmanNo ratings yet

- Scoring Incredible Futures: Science - Fiction Screen Music, and "Postmodernism" As Romantic EpiphanyDocument35 pagesScoring Incredible Futures: Science - Fiction Screen Music, and "Postmodernism" As Romantic EpiphanyJorge GuardaminoNo ratings yet

- The Return of 1960s Modernist Cinema: Hamish FordDocument16 pagesThe Return of 1960s Modernist Cinema: Hamish FordLefteris MakedonasNo ratings yet

- The Auteur Theory and The Perils of Pauline Author(s) : Andrew Sarris Source: Film Quarterly, Vol. 16, No. 4 (Summer, 1963), Pp. 26-33 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 13/06/2014 00:40Document9 pagesThe Auteur Theory and The Perils of Pauline Author(s) : Andrew Sarris Source: Film Quarterly, Vol. 16, No. 4 (Summer, 1963), Pp. 26-33 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 13/06/2014 00:40Rupai SarkarNo ratings yet

- Modernist Fiction On ScreenDocument29 pagesModernist Fiction On ScreenElisa ScublaNo ratings yet

- 1.introduction To Mise en SceneDocument16 pages1.introduction To Mise en SceneCharles BrittoNo ratings yet

- Bollywoodising Literature Forging CinemaDocument16 pagesBollywoodising Literature Forging CinemajagiyaaNo ratings yet

- N 18 Martin Scorsese Interviewed by MichDocument15 pagesN 18 Martin Scorsese Interviewed by MichZlatko OžanićNo ratings yet

- The Sense of An An Ending in Manhattan TransferDocument7 pagesThe Sense of An An Ending in Manhattan TransferBilal B'oNo ratings yet

- The Lively Art of Manhattan TransferDocument12 pagesThe Lively Art of Manhattan TransferBilal B'oNo ratings yet

- A Novel Like A DocumentaryDocument28 pagesA Novel Like A DocumentaryBilal B'oNo ratings yet

- Manhattan Transfer Spectacular Time and OutmodedDocument25 pagesManhattan Transfer Spectacular Time and OutmodedBilal B'oNo ratings yet

- Virginia Woolf Kew GardenDocument16 pagesVirginia Woolf Kew GardenBilal B'oNo ratings yet

- FINNEY TemporalDefamiliarizationToni 1990Document18 pagesFINNEY TemporalDefamiliarizationToni 1990Bilal B'oNo ratings yet

- Agptc - MechDocument2 pagesAgptc - Mechsk.swifterzNo ratings yet

- Article by Andrei TarkovskyDocument3 pagesArticle by Andrei TarkovskyOscar FizNo ratings yet

- JK Tamil Short Story 10Document5 pagesJK Tamil Short Story 10Jegadeesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Guion ShrekDocument2 pagesGuion ShrekBetzaida soto soteloNo ratings yet

- Famous Last Words From ShakespeareDocument3 pagesFamous Last Words From ShakespeareamandaNo ratings yet

- Objective CardsDocument1 pageObjective CardsGorsh GorshoideNo ratings yet

- FAME CHeRRy Refrigerated Photography Film Price Sheet (Live Updated)Document8 pagesFAME CHeRRy Refrigerated Photography Film Price Sheet (Live Updated)Fahizmir UzairNo ratings yet

- Contrastive Analysis Between "Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been" and "Smooth Talk"Document3 pagesContrastive Analysis Between "Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been" and "Smooth Talk"NasirNo ratings yet

- Above 200 Aadhar LinkDocument70 pagesAbove 200 Aadhar Linkperiya samyNo ratings yet

- Exercise in Ambiguity PDFDocument22 pagesExercise in Ambiguity PDFSimarprit KaurNo ratings yet

- Walkthrough v0.06 CH2 Subscribestar VersionDocument55 pagesWalkthrough v0.06 CH2 Subscribestar VersionAli ÖğütNo ratings yet

- A SCHOOL FOR SCANDAL by RICHARD BRINSLEY SHERIDANDocument1 pageA SCHOOL FOR SCANDAL by RICHARD BRINSLEY SHERIDANAyça GöçerNo ratings yet

- Jackie Chen SpeechDocument5 pagesJackie Chen SpeechTaufiq FahrizalNo ratings yet

- tED Ed Exploration #5Document9 pagestED Ed Exploration #5Mirzo SharipovNo ratings yet

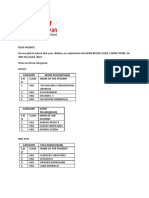

- Dear Parents-1Document3 pagesDear Parents-1sujithm435489No ratings yet

- 1 Lista 5ce - Co Canais BR 2Document8 pages1 Lista 5ce - Co Canais BR 2Elias CottaNo ratings yet

- 6 Monk - Claire - The - Shadow - of - This - Time - Punk - Tradition - and - History - in - Derek - Jarman - S - JubileeDocument15 pages6 Monk - Claire - The - Shadow - of - This - Time - Punk - Tradition - and - History - in - Derek - Jarman - S - JubileeZosia PiontekNo ratings yet

- Extension: Superheroes To The RescueDocument2 pagesExtension: Superheroes To The RescueElisabeth Acosta RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Basixsubk - Attendance Consolidation - 1832020031904Document1,834 pagesBasixsubk - Attendance Consolidation - 1832020031904khatheeja begumNo ratings yet

- Musimoviimag 2 1 0001Document26 pagesMusimoviimag 2 1 0001JACKSON LOWNo ratings yet

- STF Progress Tests Unit 3Document4 pagesSTF Progress Tests Unit 3Juan Lopez - ESLNo ratings yet

- Deborah's Theme: (Once Upon A Time in America)Document6 pagesDeborah's Theme: (Once Upon A Time in America)lauraNo ratings yet

- Final Attendance SCMDocument19 pagesFinal Attendance SCMChaitanya RavankarNo ratings yet

- Jungle Tales of Tarzan Edit PDFDocument2 pagesJungle Tales of Tarzan Edit PDFAmanda SilverNo ratings yet

- Film and Art After CinemaDocument210 pagesFilm and Art After CinemaLuka LucaNo ratings yet

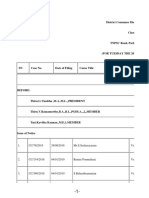

- Causelist12022 12 20Document5 pagesCauselist12022 12 20Royal BedukoNo ratings yet

- Star Jalsha: Star Jalsha Is An Indian General Entertainment Pay TelevisionDocument7 pagesStar Jalsha: Star Jalsha Is An Indian General Entertainment Pay TelevisionAnupam NaskarNo ratings yet

- The Rising of The Shield Hero 1Document5 pagesThe Rising of The Shield Hero 1Andrea MartinezNo ratings yet