Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 178.149.180.237 On Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 178.149.180.237 On Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

Uploaded by

anusha khanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 178.149.180.237 On Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 178.149.180.237 On Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

Uploaded by

anusha khanCopyright:

Available Formats

Congress Decline and Party Pluralism in India

Author(s): Christopher Candland

Source: Journal of International Affairs , Summer 1997, Vol. 51, No. 1, South Asia: The

Challenges of Statehood (Summer 1997), pp. 19-35

Published by: Journal of International Affairs Editorial Board

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24357463

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of International

Affairs

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Con gress Decline and Party

Pluralism in India

Christopher Candland1

Thepetition

Indian the

National

BritishCongress party

government was founded

in India in 1885

for administrative

and political reform. Under British rule, the Congress gained ex

perience in contesting elections and in governing at provincial

and municipal levels. In the 1920s, Mohandas Gandhi reorga

nized the party, which helped it to evolve into one of the world's

Throughout South Asia, the national political

parties that led independence movements tended

to dominate government in the formative years

of independence only to give way to

increasingly agrarian, confessional,

regional and vernacular political parties.

largest membership-based, mass organizations. Principled and

well-organized resistance to British rule confirmed the Congress

as the party of Indian national independence. As the Second

World War weakened Britain's colonial grip, the Congress was

invited to take charge of the central government, almost a year

before independence in August 1947.2 The Congress has been

I thank Grace Kim, Philip Oldenburg, Mia Son, David Stuligross and Arun Swamy

for their generous help.

The British Viceroy invited the Congress to form an Interim Government. After

some debate within the Congress, the party accepted. Significantly, the Viceroy did

not invite an elected legislator from the Central Legislative Assembly, but rather

invited Jawaharlal Nehru, president of the Indian National Congress to form the

Interim Government. The basis of this decision was the Congress's strong perfor

mance in the 1945/46 provincial council elections. See Robin Jeffrey, "The Prime

Minister and the Ruling Party," in James Manor, ed., Nehru to the Nineties: The

Changing Office of Prime Minister in India (Vancouver: University of British Columbia

Press, 1994) pp. 163-165. Nehru resigned his position as Congress president,

foreseeing a conflict between the Congress organization and the Congress in gov

ernment. See further Stanley Kochanek, The Congress Party of India: The Dynamics

of One-Party Democracy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1968) pp. 4-5.

Journal of International Affairs, Summer 1997, 51, no. 1. © The Trustees of Columbia

University in the City of New York.

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Journal of International Affairs

the party in government at the national level, or the center, for

all but six years since India's independence, 50 years ago.3

Today, however, the Congress is out of power and, for the

first time since independence, it is not the party with the greatest

number of seats in the Lok Sabha (People's Council), the popu

larly elected house of Parliament.4 The Hindu nationalist

Bharatiya Janata Party (Indian People's Party) occupies the larg

est block of seats. Twenty-eight parties are represented in Parlia

ment, the largest number in independent India's history. A coa

lition of 13 regional and left parties, the United Front, presently

governs at the center.5

The Indian National Congress has been the most impor

intro/conclusion tant institution in India's modern political development. The

Congress, a favorite example of a dominant party in a competi

tive party system, was thought to be the backbone of the devel

oping world's best institutionalized democracy.6 Today, the Con

gress is seemingly in advanced stages of decline. Each of the non

Congress parties, including those presently in government at the

center and in most states, represent more focused interests than

the Congress can seemingly retain. Moreover, many suggest that

the Indian political system is being destabilized by rising social

unrest and institutional decay.7 That sentiment is buttressed by

the increased electoral support to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)

in past parliamentary elections and in a number of significant

state assembly elections.8 Some have cautioned that the new so

The Congress was in power at the center from independence in August 1947 to

March 1977, from May 1980 to November 1989, and from June 1991 to May

1996.

The Indian Parliament is comprised of an upper house, the Rajya Sabha (States'

Council) and lower house, Lok Sabha (People's Council).

On 28 March 1997, the chief of Congress' Parliamentary Party, Sitaram Kesri,

withdrew Congress support to the ruling coalition. H.D. Deve Gowda's replacement

by Inder Kumar Gujral at the head of the United Front coalition on 21 April 1997

has re-established the necessary support from the Congress.

See, for example, Giovanni Sartori, Parties and Party Systems (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1976) p. 124.

For comparative analysis of the falling performance of Indian political institutions

at district, state and national levels, see Atul Kohli, Democracy and Discontent: India's

Growing Crisis of Govemability (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

Between the 1991 and the 1996 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP increased its share

of seats, from 119 to 161, but not its share of the electoral vote, which actually fell

below the 1991 level of 20.95 percent to 20.3 percent in 1996.

20

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Christopher Candland

cial forces and popular demands that have lead to religious reviv

alist and to caste-oriented parties cannot be accommodated in a

parliamentary democracy.

The leadership, constituencies, issues and electoral strat

egies of political parties have undergone significant change in the

50 years since independence in India. Do these changes, most

notably the decline of the Congress, signal the arrival of more

pluralist politics in India? To advance upon this question, this

essay comments on the evolution of the Congress within the In

dian political party system.9 A brief assessment of the reasons for

and the depth of the Congress's decline suggests that the Indian

party system is neither in the midst of systemic crisis of gover

nance nor endangered by religious revivalism. Emergent forms of

electoral appeals and political contest may not quite conform to

the theoretical postulates of pluralism, but as the Indian elector

ate has broadened, the Indian Parliament and India's more than

two dozen state assemblies are becoming more representative of

Indian society as a whole, including its caste, class, religious and

other social cleavages.

Congress Dominance

The Congress ruled continuously at the center and in most

Indian states, from the first general election in 1952 until the 6th

general election in March 1977. The party has retained power

at the center more often than not since. However, the Congress

has been dominant not by virtue of its command of an undemo

cratic electoral system but rather by virtue of its depth of leader

ship and its organizational capacity. Although the Congress had

been the dominant party, it has not attempted to make itself into

an organization with an exclusive claim to governance, as have

Mexico's Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Revo

lutionary Party) and Indonesia's GOLKAR. Strongly competi

tive multi-party elections have been regularly held in India since

independence at national, state and local levels and electoral ver

dicts have been respected by unsuccessful incumbents.

For a thorough discussion of Indian democracy and development, see Jyotirindra

Das Gupta, "India: Democratic Becoming and Combined Development," in Larry

Diamond, Juan Linz and Seymour Martin Lipset, eds., Democracy in Developing

Countries: Asia, vol. 3 (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 1989) pp. 53-104.

21

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Journal of International Affairs

In India's first-past-the-post system, elections do not yield

representation in proportion to votes received. The first-past

the-post electoral system entails that a candidate wins by ob

taining the greatest plurality of votes, not necessarily the major

ity of votes. An edge at the polls therefore can result in a large

majority of seats, especially if political parties divide constituen

cies among themselves, as they often do, rather than compete

with each other directly. Such no-contest alliances allow parties

to secure constituencies for which they might otherwise not have

the votes. Still, the Indian voter faces a wide array of candidates.

An average of 14 candidates ran in each constituency in the 1996

general election. Until that election, the Congress had consis

tently managed to appeal to enough voters to be just past the

post in most constituencies. Thus, even in the years of Congress

dominance, from 1952 to 1967, when the Congress held more

than 70 percent of the seats in parliament, the Congress never

received more than 50 percent of the vote in parliamentary or, in

aggregate, in state assembly elections.10 The Congress's dominance,

like the Congress's decline, has been exaggerated by the dispro

portionate results of the first-past-the-post electoral system.

Under Jawaharlal Nehru, prime minister from 1947 until

his death in 1964, the Congress commanded tremendous organi

zational capacity, relying on local, state and national level Con

gress committees and members and vast networks reaching across

more than a dozen European-sized states. It contested every

parliamentary constituency and almost every state assembly and

municipal constituency. The Congress was a well-organized party

with motivated party workers and an unusually effective leader

ship. In the estimation of Myron Weiner, a careful student of the

Congress, the party took seriously its "organizational problems"

and "its own rules and regulations."11 This allowed the Congress,

in the first two decades after independence, to incorporate indi

viduals with different political ideologies and constituencies. Until

1948 the Congress even permitted parties that had distinct orga

nizational structures and independent constitutional principles

to operate within the Congress organization.12

Lloyd Rudolph and Susanne Rudolph, In Pursuit o/Lakshmi: The Political Economy of

the Indian State (Chicago: The Chicago University Press, 1987) pp. 130-131.

Myron Weiner, Party Building in a New Nation: The Indian National Congress (Chi

cago: The University of Chicago Press, 1967) p. 461.

Craig Baxter, Yogendra Malik, Charles Kennedy and Robert Oberst, Ciovernment and

Politics in South Asia (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1995) p. 101.

22

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Christopher Candland

In its first two decades as a party in government, the Con

gress was remarkably adept at accommodating rival interests

outside the party and especially within it. According to Rajni

Kothari, another careful student of the organization, the Con

gress system was based upon factional alliances within the party

and between these party factions and non-party interest groups.

Kothari developed the concept of the Congress system to charac

terize the internal arrangement that permitted, during the first

two decades of independence, rival interests to exist and reach

compromises within the party.13 Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru

not only had a firm command on the organization, but also facili

tated the settling of factional conflicts within the party.

While the Congress was once "extraordinarily successful...

in recruiting new members, winning competitive elections and

avoiding fragmentation,"14 a conflict soon developed between the

Congress organization, including Congress office bearers, party

workers and dues-paying members of the party, on the one hand

and the Congress in government, comprised of only the elected

Congress members of Parliament and state assemblies, on the

other.15 As prime minister and head of the Congress in govern

ment, Nehru respected the independence of the Congress organi

zation and ensured that elections were held for party offices. The

succession struggle after Nehru's death in 1964 gave rise to open

conflict between the party organization and the party in govern

ment. Lai Bahadur Shastri was selected to succeed Nehru as

prime minister, but the succession struggle re-emerged with

Shastri's death in 1965.

A rift had developed between senior members of the Con

gress organization, known as the Syndicate and younger Con

gress leaders who wanted to quicken the pace of social transfor

mation. The Syndicate selected Jawaharlal Nehru's daughter,

Mrs. Gandhi, who had served as her father's advisor and in

Shastri's cabinet, to be prime minister. Meanwhile, the Congress

performed poorly in both the Lok Sabha and state assembly elec

13 Rajni Kothari, "Congress 'System' in India," Asm/i Survey, 4: 12, (December 1964)

pp. 1-18.

14 Weiner, p. i.

15 According to Stanley Kochanek, the Congress organization was under challenge as

soon as the Viceroy appointed a Congress Interim Government in September 1946.

Congress thereafter was forced to balance the interests of the national political

organization and of Congress legislators. Kochanek, pp. 3-26.

23

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Journal of International Affairs

tions in 1967. The Congress retained a majority of seats in Par

liament but lost most state assemblies. The Congress govern

ment at the center faced ruling opposition parties in eight states.

Factional leaders within the party defected and allied themselves

with opposition parties.16 The elections of 1967 seemed to be the

long-awaited death toll of the Congress. As Mrs. Gandhi sided

with the young Congress Socialists in important economic policy

resolutions and in her candidate for President of the Republic,

Mrs. Gandhi was expelled from the Congress causing it to split in

November 1969. Her faction, originally the Congress (R), later

to become the Congress (I), took with it 223 of the 283 Congress

members of the Lok Sabha.17

In the 1970s, Indira Gandhi turned the Congress into an

organization directed from the prime minister's office. With a

populist campaign based on the slogan garibi hatao (abolish pov

erty), Congress (R) performed very well in the 1971 general elec

tion, securing 352 of the 518 seats in Parliament and re-estab

lishing Congress governments in all but two states.18 Mrs. Gandhi

took personal control of Congress affairs, rather than allowing

conflicts to be resolved at lower levels as had Nehru. Decisions

about the selections of chief ministers and state cabinets "were

made by Mrs. Gandhi herself in consultation with a clique of

personal advisors."19 Mrs. Gandhi dismissed and appointed Con

gress chief ministers and exercised, through the Office of the Presi

dent, the government's prerogative to dismiss the opposition in

state assemblies. Article 352 of the Indian Constitution, "in case

of failure of constitutional machinery in States," allows the presi

dent, upon the advise of a state governor, who is appointed by

the center, to dismiss the chief minister and state assembly and

16 See further Kochanek, pp. 407-447.

17 The R originally stood for Requisitioned and later denoted Ruling. After a further

split in 1977, Congress (R) became Congress (I), where I stood for Indira. See Paul

Brass, The Politics of India Since Independence, 2nd edition (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1995) p. 72. The analysis of the Congress in this essay relies

heavily on Brass, pp. 69-78.

18 It is interesting that similar populist politics and economics were employed at the

same time by Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and his Pakistan Peoples Party in

Pakistan (1972-77) and by Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike and her Sri

Lanka Freedom Party in Sri Lanka (1970-1977). All three leaders emphasized

mobilizing social support to themselves rather than institutionalizing social support

to the party or government.

19 Brass, p. 72.

24

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Christopher Candland.

to assume control of the state government. The president, in

practice, acts upon the instruction of the prime minister. Nehru

used the president's rule sparingly. Mrs. Gandhi, and her succes

sors, used the president's rule more extensively. Non-Congress

coalitions at the center would later exercise this same preroga

tive, most blatantly after the emergency when the Left Front gov

ernment dismissed nine Congress state governments. While Mrs.

Gandhi's populist rhetoric may have initially helped to consoli

date the electoral support basis of the party, her autarchic con

trol of the Congress quickly undermined the organization.

Congress Decline

The de-institutionalization of the Indian National Con

gress under Mrs. Indira Gandhi is the major theme in the post

colonial history of the Congress. It may be more convincing, how

ever, to relate the decline of the Congress to unprecedented eco

nomic challenges and to Congress's unfulfilled promises of social

and economic reform than to attribute it solely to one woman's

style of leadership. Mrs. Gandhi may have been less benign to

ward lower level politicians in part because regional autonomy

movements and protests were more threatening to the center.20

Further, Nehru and other senior Congress leaders had pro

moted industrial development and avoided effecting radical

changes in the social patterns of agricultural production. Instead,

economic policy in the initial years of independence focused on

the less politically divisive problem of industrial development.

Results of the import substitution-oriented industrialization strat

egy, which has only recently been abandoned, include a highly

diversified industrial sector and a large measure of technological

self-sufficiency. Other results of Nehruvian socialism include de

clining capital productivity and persistent high unemployment.

Mrs. Gandhi's response to these and other economic crises in

cluded the nationalization of numerous labor intensive indus

tries, including coal mines and textile mills.

In this troubled economic environment, the Allahabad

High Court found Mrs. Gandhi guilty of violating minor election

See further Jeffrey, pp. 181-182.

25

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Journal of International Affairs

regulations.21 She was ordered to resign from office and banned

from holding office for six years. Two days later, in the earlier

hours of 26 June 1975, Mrs. Gandhi declared a state of national

emergency. An executive order, amending the Maintenance of

Internal Security Act, permitted Mrs. Gandhi to have thousands

of opposition politicians and other detractors arrested and jailed,

the press censored and opposition protests and political gather

ings banned. During the emergency, Mrs. Gandhi used the

president's rule in the only two non-Congress controlled states,

Gujarat and Tamilnadu, to bring "the entire country under di

rect dictatorial rule from Delhi."22 She and a small group of sup

porters, including her son, Sanjay Gandhi, directed police and

local government and effected administrative transfers.

With a stronger than two-thirds majority in both houses

of parliament, she amended the constitution to remain in power.

Then, persuaded by her advisors that she would win, the prime

minister scheduled the national elections for March 1977. After

an ignominious 20-month emergency rule, Mrs. Gandhi was

soundly defeated by a hastily assembled coalition of political par

ties and protest movements. Indira Gandhi's emergency irrecon

cilably damaged the Congress's ability to accommodate factional

interests.

Morarji Desai, the conservative finance minister whom

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had dismissed in an opening con

frontation with the Syndicate, became prime minister at the head

of the Janata coalition. The Janata coalition, however, proved to

be unstable, and the electorate returned the Congress to power

at the center in elections in May 1980. The growth of non-Con

gress political parties, which have thrice held power at the center,

has in large part been made possible by defections and expulsions

from the Congress. All of India's non-Congress prime ministers,

Morarji Desai, Charan Singh, VP. Singh, Chandrashekar, H.D.

Deve Gowda and Inder Kumar Gujral, were formerly members of

the Congress party. VP. Singh, former defense minister and fi

nance minister to Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, for example, and

others expelled from the Congress in 1987, formed the Jan Morcha

21 Mrs. Gandhi was found guilty of having government officials erect speaker stands

and supply electricity to her campaign appearances. Henry Hart, Indira Gandhi's

India: A Political System Reappraised (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1976) p. 3.

22 Brass, p. 41.

26

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Christopher Candland

(People's Front). The Jan Morcha later joined with the Janata

Party and the Bharatiya Lok Dal to successfully challenge Rajiv

Gandhi's Congress in the ninth general elections in 1989, when

VP. Singh became prime minister.23

Mrs. Gandhi's rule between the 1969 Congress split and

the onset of the state emergency in 1975 is aptly characterized

as plebiscitary.24 Her governance was based on mass appeals un

mediated by the party organization. But Jawaharlal Nehru's rule,

to which Mrs. Gandhi's is either explicitly or implicitly compared,

was unusual for the high degree of political agreement over po

tentially divisive developmental challenges. Nehru managed re

gional demands well. However, the challenges facing the Con

gress and the Congress leadership after Nehru's death were deeper.

These included war with Pakistan over Kashmir in 1965, famine

conditions after successive monsoon failures in 1965 and 1966,

war with Pakistan again in 1971 over the secession of East Paki

stan, the absorption of hundreds of thousands of refugees from

the war, and a number of powerful and militant separatist move

ments, including the Telengana and coastal Andhra separatist

movements. Moreover, divisions within the Congress were height

ened by the economic crises beginning in the mid-1960s.

Party Politics After Congress Dominance

The Congress has gradually lost its once reliable support

from significant constituencies since Mrs. Gandhi's emergency

seriously injured the relationship between Congress and Muslim

voters.25 Muslims, lower caste, and scheduled caste constituents,

who once regularly voted for the Congress, have gradually shifted

their support to the Janata Dal and to various regional parties.26

In many states, parties have successfully mobilized voters on the

basis of caste. In Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, for example, the Janata

Dal and the Bahujan Samaj Party have mobilized scheduled caste

voters. In Kerala and West Bengal, the Communist Party of In

dia (Marxist) has mobilized lower and scheduled caste voters.

23 Baxter, Malik, Kennedy and Oberst, p. 110.

24 ibid., pp. 136-137.

25 Rudolph and Rudolph, p. 190.

26 See further the findings of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies' na

tional exit poll, coordinated by VB. Singh and Yogendra Yadav, as reported in

Yogendra Yadav, "How India Voted," India Today (31 May 1996) pp. 44-50.

27

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Journal of International Affairs

India's highly federalized political system allowed regional

parties to secure portions of the Congress vote and to mobilize

new constituencies. State governments have significant author

ity in most economic and social sectors, including agriculture and

industry, education and labor. The evolution of the political party

system in India has been heavily influenced by competition be

tween political parties over public resources at national and state

levels. States not only have unique political histories and diverse

cultures, but also distinct political parties and configurations of

party competition. In many Indian states, predominantly in the

southern and eastern states, variations of a two-party system have

emerged.27

Notable Congress successes in the 1984 and 1991 general

elections are commonly attributed to sympathy waves following

the assassinations of Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi, respec

tively. In the aftermath of the 1991 parliamentary election, some

argued that there was no national alternative to the Congress.

However, in the 1989 and 1996 parliamentary elections, with

out the sympathy vote, Congress support in the polls fell to his

torical lows. After the state assembly elections conducted be

tween 1993 and 1995, some then pronounced the final defeat of

the Congress system.28 Nevertheless, in the April/May 1996 par

liamentary elections, when the Congress received just 28.8 per

cent of the vote, its lowest percentage of the popular vote in a

general election, its vote still exceeded that of any other party.

The BJP won the largest number of seats with just 20.3 percent

of the popular vote, concentrated in the Hindi heartland states

of Bihar, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh.

In only five of 25 states and union territories, Assam, Bihar,

Haryana, Karnataka and Uttar Pradesh, did the Congress re

ceive less than 30 percent of the vote; the BJP received more than

30 percent of the vote in only five states.

Another portrait of the Indian electorate can be drawn

from constituency level data in state assembly elections. Between

the 1952 and 1993-95 state assembly elections, electoral partici

pation increased steadily, from 45 percent to 64 percent of the

electorate.29 Available evidence suggests that the higher partici

27 Brass, p. 103.

28 Yogendra Yadav, "Reconfiguration in Indian Politics: State Assembly Elections, 1993

95," Economic and Political Weekly, 31:2-3, (13-20 January 1996).

2" ibid., p. 96.

28

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Christopher Candland

X Os

ÖO GO

•S X

bON—'

V <u S

to Q

I! ?

O cv "§

g Êo

.2

>

w cS -o -d . ^

3 £

Q- « &^S:«feS

t- 2 I

o z___z

5. b-ç_za^ £ .2 ^

Cu _ gpa. 0-Q"«Ol

^ Dh &H "?*- 5^8,

f~~°^ O*O- >~y

®"< ^S ^) Dh Oh S~n

i-/^" m ' ~ §

g^ H

H o§® S I SJj J§ K

® 0:i§5c^3-§

w y— ' '—'—''——"-—•— ' eo2^

£

g tt

ttt>^oo\qco©escoco©'f

r~.Ti<oo>ceo©escocop'<t;

■♦ \o Z jg c •"*;

jj £ >o 1 Jg

co«ioo6<>ON'^^t--^cNoovcs«p,)Tr

c*i«iooôovON'f'!t"-^cNÔovcs«eOTr CO Q\

V X. «o> .3 2 2

C co cogN^-<tnMci^NnN^2con

> cs <f —i co CO co Tt1 w co cs ■* £ co co Si-* £g

. ^ ^-^wQ .2

CK CJ

C '

o

as V

.r* (sy

i-s d t

U-S1 /■*!

Oo—

_•

_ rr* r/> nri ^ —• i»—n i^\ __. ia in _

— oococooooov-<Oin —m■<u~

-j^coeofocoo^Hq^

- • ■ : ■ • • • •. •. ■ ■ _, ~

— s^-S t£ *S

• > T i^ PVz _

cu

©ö *"S—<' —■

co cn -tf

coo CSr^.' —<"

TfO rf inN in -<

o'^ cxj

Tf Cs IT)

"So1? iri

S "o 2 3

on3 CO C\ ?

> —< CO CN lO CO CO CO CO co

Tf^^cocNinromcnco^cntc CO 52Tf o.

D~ £_C

O.

CO KnC

d2 °- a.^ « £

C £U <u -"7? 2P a is ^ S^jf

00J3

o!o J3 gi® .S u ^

?o§: Is «i-S'S

1§2

_g o 55 I i >>§ Sc. 5

•em>r- h 5 1,2 « I

|o

1 &3

3P i^, i is g H n

I3!?

I'Sfc 1°

lag

Sq| 61

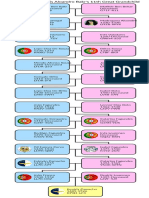

Table 1.

II.S

,«» ■*/£-ä ^ 0-2

P _, û-i 0-

S C-<(S,

û

2^1 ïbsz^r

gts ~ _ ^2 ^ 1 srbazs?

I > _&r

2 H

"3

s

TrS _CUn.CL.Q- .CU CU ~

S QO^£ife^^5:£i£LQ&3£i2fe£

< cq J iSS-oS-S-®

2-S2-S® ffl« ^.g.g,Q®y.

111

raut,~r-c

|.<J3

copp,J;Tr,oooqt-^o\cN\ot--.o\t^oocN

co^o-H.,J;-foqoqi^ONcN\Ot--.ONt^oqcNJ| J|

2; 'S

2; "2

„ cNr^^diocsodo-^OTro^dcsicNu-;

cNr^-^dincsodo-.'cj-ro<c>cNCNio

"2 >a £"5 vb £

VN ' ^ NJ •w' U ] >» N4 y^j y^J —-I y^j NJ V_/ ' ^ I. n U ) *J \T\ (

?c COCQ'-<COUncvi't,CNCQTt<(MCO

—< CO b"> CS •*»" CM CO -? M—

CO—'CQIOCN^'CNCn^fCNCO'— CO-^fCNCOCQ

— if CN CO~~CO

^TCNCQCQ Ccsä"

On \1

- ö5 2j 3COS

•s ss:

O I §D

** §!

•g

vo in cs o cs cs oplOCNOCSj(N

oo eo Tf ^ co o vjd co cn ^

ci « ind^di-ZvOrtQÔinoÔTrd'^'csodvC! S

UOOO^Ovt^vO'-JoOlOOOTfON'^cScdvO

^ CS CN CS CO Tf Tf CO Tf Tf Tf <f Tf —< CO

g 1: •<j<cscscNco'<J,'tcOTj<^''<j<T)<'tiTti-^co 5S •

3 ^ 8 ^ jS

Congres andClosetCompetiorsinSomeSignfcantSaes

1?«

5.

<U ^ 4>

Joo

•tfT? u

S >3 8

4/5 » w

<2 I Sf

«l 'S

Cfl

J

-J* ON

çfl -4«; On i 6"^ -s

«Jg i£ 3 Q

«|8

c O

So c

o °- S jj "« ■fi a 35„< S

2 3^^ to

£j a li? ^1"I 11

III

a x ls«|S§ «^2q'Sqw g </> 2 « "2 A

r- QJ >-C O "{S On '2 *s ri C A Û n ^

•S

"S

ÏÏ

S *

-S

-d ft

-2r-

a r-

£ £g

^ S§

ON 5 % '3

>3

g •^■5

U ü fl-O

-^-g 2 g

„

§ So

g

50

3

■o

"O ^2 >

co Ü2 'S—

— 2 ij sj«2.l2

^ ox* cq 2 .b.

a

aj 0-4

i-

w-rt

0~> 2i3

r,_£

ru_g

2 £5

r r

3T3

u c^

3TJ

U ai

W1

S«s3

S«1552^0

M *^ 1:

3J2.Q

^ ^^ °-§

«*>

2 ^

°-§ ««gg<<CQ ■S|

t3c8/i?S-Sr<»-'

08 Ä 5 -2 rw

CQQQJ3,lo

Üuo

cq Q H

H

^^2 ^

* ^-S

^_I * r-

r- § CTj

*

-o nj

2

§^Sra

T3t£^2 g

^ <U ^ Jg C

s: rl,î£'W

^-2 ê

3 ti

2e rtrtu^n!>r.^_-Q-ScG'pa

Je 2w'"rtc,!J''rt«-9"ScG'pa P B>«

pe. •§ » 's ^l,1^ •§

=1.2.§ I aifre

2 ^ «J E 2 ^ -S gâ=§-S Slaijas

si"! J a.. ^Ms

Jo£5S1»3h. RS5 k

g 3 g« §II™ Q »&s *

S

5 ?|£ozS^^22c§£cSt25l lis!??

-ScS3rt|Sfe««î§'rt=0^

IlléâlaâilSIJlSS Ils Z^: I^ "lia

;

<«lalp >oo F

29

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Journal of International Affairs

pation rate is a reflection of increased participation of other back

ward castes, a designation including those backward castes not

listed, or scheduled, in two 1950 Presidential ordinances. Time

series data on electoral participation by social background is not

available. However, "[pjractically everywhere rural constituen

cies report a higher turnout."30 The candidates that voters send

to Parliament and to state assemblies are also increasingly of ru

ral and of lower caste background. The percentage of Lok Sabha

members with agriculturist backgrounds has risen steadily from

22.5 percent in 1952 to 51.4 percent in 1996.31

In India, as in Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, the

generation of leaders who held power after independence have

been replaced by a generation of leaders whose constituents and

issues are more representative of society as a whole. The national

parties that led in important phases of the independence struggle,

including the Communist Party of India and the Congress, have

been in long-term decline. Throughout South Asia, the national

political parties that led independence movements tended to

dominate government in the formative years of independence only

to give way to increasingly agrarian, confessional, regional and

vernacular political parties.32 It is not only that the Congress but

also the institutions of government, with which the Congress has

been identified, that are suffering a crisis of legitimacy. As mecha

nisms for democratic participation, political parties in India, as

elsewhere, are limited. Social movements often vie with political

parties as mechanisms for democratic representation, and have

provided impetus to emergent political parties.

As Table 1 suggests, the Congress suffered a significant

decline in support between the 1991 and the 1996 Lok Sabha

elections. However, the party remains the first or second most

significant party in all but one state. Despite its decline, Con

gress remains the most significant national political party.33 No

party has out-performed the Congress in percentage of the vote

secured in a general election. Only twice since independence has

a non-Congress party received even half of the Congress's per

30 ibid.

■" Harinder Baweja, "Changing Face of Parliament," India Today (15 July 1996) p.

42.

32 For more on national parties in the Indian party system, see Brass, pp. 100-104.

Brass, p. 102.

30

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Christopher Candland

centage of the vote. Even in the April/May 1996 general elec

tion, the third occasion on which the Congress failed to secure

the seats necessary to form a government at the center, no party

gained a higher portion of the popular vote than did the Con

gress. At the same time, non-Congress political parties, including

the BJP and some regional parties, are now well-established in

India's party system.

The gradual decline in electoral support to the Congress

from significant social sectors is not surprising for a national in

dependence party in one of the world's most diverse countries.

As the organizational umbrella for a national independence move

ment, the Congress devoted attention to the recruitment and par

ticipation of party members and party workers. Through party

splits and electoral defeats, the Congress has changed substan

tially since its founding more than a century ago. In the first two

decades of independence, Congress developed the depth of lead

ership capable of accommodating and disciplining rivals. Under

Indira Gandhi, the Congress party in government helped to un

dermine the Congress organization.

Pluralism

Does the increasingly representative character of Indian

parliaments and state assemblies signal greater pluralism in In

dia? India has witnessed a transition from single party domi

nance to increasingly diverse regional configurations of party com

petition. At the time of independence, the leadership of the In

dian National Congress was educated in Western schools, spoke

English fluently, and enjoyed considerable social status and eco

nomic resources, as did the leadership of the independence move

ments in Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Land-owning upper classes con

tinue to dominate politics in South Asia, but voters have increas

ingly placed in office individuals with more agrarian and vernacu

lar roots. Leadership in all parties, including the Congress, is in

creasingly that of lower and middle status backward castes.34 Is

this not then evidence of pluralism?

Assessing whether the Indian political party system is more

or less pluralist with the gradual decline of the Congress demands

clarity on the theoretical postulates of pluralism and the intellec

ibid., pp. 103-104.

31

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Journal of International Affairs

tual tradition within which pluralism is embedded. Pluralism

presumes that individuals are the principal social actors, that in

dividual interests animate behavior, and that, as these interests

are neither fixed nor permanent, they can be aggregated and ne

gotiated by political parties and other organizations in society in

a market fashion.

The intellectual founders of the American Revolution

found political parties, well-organized factions bent upon gaining

political power, to be inherently dangerous.35 The early Amer

can resolution to the dominating and violent tendencies of fac

tions was a governmental structure that would multiply factions

through an institutionalized separation of judicial, legislative and

executive powers. The resolution prefigured the answer that pl

ralism would provide to American democratic theorists in th

middle of the 20th century.36 The pluralist solution presumes that

individual interests are un-fixed and fluid. It is the assumption

that interests can be negotiated makes diversity of public asso

ciations, interest groups, social organizations and political par

ties, the mechanism for guarding against tyranny of both elit

and popular varieties. With sufficient diversity of opinion among

cross-cutting and un-fixed interests, it is reasoned, an equilibrium

will arise that mitigates against the domination of the many b

the few.37

Political parties thrive in India as throughout South Asia.

But the nature of diversity of political parties is as important as

the fact of diversity. Parties that led historically significant inde

pendence movements in South Asia, often led by first families

have given way to more populist leaders and confessional poli

tics, to the greater significance of regional issues and personali

ties, and proportionately more voters from agricultural and rural

backgrounds. The political parties that have made their way on

to the political scene in South Asian countries in recent years are

not of the same kind as the national political parties that pre

The Federalists disagreed, however, about whether the Republican party was a fac

tion. See Terence Ball, "The Prehistory of the Party," in Transforming Political

Discourse: Political Theory and Critical Conceptual History (New York: Basil Blackwell,

1988) pp. 42-46.

See Robert Dahl, Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition (New Haven, CT: Yale

University Press, 1971).

See further C. B. Macpherson, "Market Concepts in Political Theory," in Democratic

Theory: Essays in Retrieval (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973) pp. 185-194.

32

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Christopher Candland

ceded them. They represent new constituents and new aspira

tions, but not every interest is qualitatively similar. Religious

revivalist and caste-oriented politics often poses exclusivist poli

cies, which make the pluralisms solution—negotiation of inter

ests—seem Utopian. The rise of regional and confessional politi

cal parties in South Asia does not necessarily provide a new sprin

kling of forces for a new pluralist equilibrium. The agreement by

the largely upper-caste backed BJP and the scheduled caste

Bahujan Samaj Party to alternate at governing Uttar Pradesh for

periods of six months each suggests that caste representation does

not produce the equilibrium of interests envisioned in the origi

nal concept of pluralism.

Political party competition in India and elsewhere in South

Asia is increasingly along communal and caste lines. Next to po

litical party alliances, caste loyalty is currently the most signifi

cant determinant of electoral outcomes. In some states, as in

Tamilnadu, backward castes have constituted the main opposi

tion to the Congress.38 In other states, there is clear evidence of

caste polarization of parties and their platforms.39 The issue de

serves a more thorough discussion than is possible here, and it is

difficult to generalize about Indian political parties without state

and district level analysis. However, pluralism, as envisioned by

its major proponents, is no more in evidence today in India than

it was under the initial period of the Congress system, when com

promises between conflicting interests were reached within a pre

dominantly western-educated, land-owning nationalist party.

Electoral alliances between caste oriented parties are inconsis

tent with the market model of interest representation inherent in

the concept of pluralism.

One might also distinguish between internal and external

pluralism in party systems. While competitive political parties

may be essential to pluralist political systems, they are not gener

ally internally democratic. The Congress is not an exception.

Elections held for membership in the Congress Working Commit

tee (CWC), the executive body of the Congress, were held in 1992

for the first time in 20 years. The Congress Parliamentary Board,

38 Brass, pp. 103-109.

38 Kanchan Chandra and Chandrika Parmar, "Party Strategies in the Uttar Pradesh

Assembly Elections, 1996," Economic and Political Weekly, 32:5 (1 February 1997)

pp. 214-222.

33

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Journal of International Affairs

which determines final lists of party candidates, has not met for

five.40 Only one-third of the CWC was elected by party mem

bers; the other CWC members are appointed by the President of

the Congress organization. Arid when elections were held under

P. V. Narasimha Rao, elected members were asked to resign their

seats so that they could be appointed by Rao. The Congress party

no longer entertains an open exchange of potentially rival ideas.

In the post-P.V Narasimha Rao era, there initially ap

peared to be grounds for believing that the Congress would inter

nally democratize. Under P.V. Narasimha Rao, the Congress had

suffered further defections and splits. In September 1996, after

Congress's defeat in the 1996 general election, Sitaram Kesri re

placed P.Y Narasimha Rao as Congress president. Kesri appointed

new Congress office bearers and brought back Congress dissidents.

Appointments, such as those to the Congress Parliamentary Board,

were given to state level Congress leaders, helping to solidify Con

gress unity. Kesri's announcement of withdrawal of Congress sup

port to the ruling United Front, however, took some of the party

leaders by surprise, indicating that the Congress organization still

suffers from personal factionalism.

There has been considerable concern that the rise of Hindu

revivalism will transform India's party system. While political

parties are increasingly representative of the rural and vernacu

lar interests of the Indian electorate and while electoral campaigns

and political discourse is imbued with more cultural and religious

images and content, the concern with religious revivalism may be

overstated. India's competitive party system limits religious re

vivalist movements. Champions at the polls must demonstrate

skills in governance, which tends to modify militancy and exposes

claims of extraordinary virtue to everyday politics and adminis

tration.

While India's political parties increasingly appeal to caste

loyalties and communal divisions, Indian voters tend to behave

as if their interests are un-fixed. The Indian voter has a strong

preference against incumbents. Anecdotal evidence might point

to the Indian voter's unassailable reasoning that the most likely

to abuse power are those already in positions of power. What

Zafar Agha and Harinder Baweja, "Sitaram Kesri, Bracing for Power," India Today

(31 December 1996) pp. 33-37.

34

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Christopher Candland

ever the precise reasons for shifting electoral identities and pref

erences, it is not that Indian voters are volatile, but rather that

they apparently define their electoral interests in un-fixed ways,

voting by caste in one election and by conviction in the next. It is

this facet of pluralism, the evolving recalculation by voters of their

interests, that is most abundant in Indian politics and in South

Asia politics in general, ds

35

This content downloaded from

178.149.180.237 on Fri, 01 Oct 2021 06:41:28 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Communication Skills in Contemporary Corporate MilieuDocument19 pagesCommunication Skills in Contemporary Corporate MilieuAvisek SilNo ratings yet

- 12 Political Science - Era of One-Party Dominance - Notes Chapter2Document7 pages12 Political Science - Era of One-Party Dominance - Notes Chapter2sayooj tv100% (7)

- AP Microeconomics As Block MidtermDocument18 pagesAP Microeconomics As Block MidtermKenny Cohen100% (1)

- Section B Writing - 15 MarksDocument4 pagesSection B Writing - 15 MarksArjita SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Kushal Pal - DYNAMICS OF PARTY SYSTEM AND FORMATION OF COALITION GOVERNMENTDocument13 pagesKushal Pal - DYNAMICS OF PARTY SYSTEM AND FORMATION OF COALITION GOVERNMENTKhushboo SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Era of One Party DominanceDocument14 pagesEra of One Party DominanceShreeya YumnamNo ratings yet

- Disintegration of Party System in IndiaDocument20 pagesDisintegration of Party System in IndiaOnindya Mitra0% (1)

- The Era of One Party DominanceDocument5 pagesThe Era of One Party DominanceVibo ChishiNo ratings yet

- Notes - The Era of One Party DominanceDocument12 pagesNotes - The Era of One Party DominanceSafwa KhasimNo ratings yet

- Core Course Paper-4: Political Process in India Study Material: Unit I-VIDocument145 pagesCore Course Paper-4: Political Process in India Study Material: Unit I-VISanskriti ChoudhuryNo ratings yet

- Test 4 Model Answers-1Document5 pagesTest 4 Model Answers-1ABHI PIMNo ratings yet

- Political Parties and Elections in India: An OverviewDocument62 pagesPolitical Parties and Elections in India: An OverviewSugunaNo ratings yet

- Congress SystemDocument4 pagesCongress SystemVanshika KunduNo ratings yet

- James Manor - Government and Opposition in IndiaDocument29 pagesJames Manor - Government and Opposition in IndiaKhushboo SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- 323) Compiled Crux Party System Part 1,2Document24 pages323) Compiled Crux Party System Part 1,2Rohith UrsNo ratings yet

- Introduction: Conflict, Pluralism and The Competitive Party System in IndiaDocument36 pagesIntroduction: Conflict, Pluralism and The Competitive Party System in IndiaRaghav KumarNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 164.52.199.23 On Wed, 12 Oct 2022 11:01:53 UTCDocument17 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 164.52.199.23 On Wed, 12 Oct 2022 11:01:53 UTCAnnaNo ratings yet

- IJCRT1033043Document6 pagesIJCRT1033043djhinga12No ratings yet

- State Party SystemsDocument10 pagesState Party SystemsSatyanshNo ratings yet

- Political Science Class 12 Notes Chapter - Era of One-Party DominanceDocument6 pagesPolitical Science Class 12 Notes Chapter - Era of One-Party DominanceDharvi MohataNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Indian Political Party System - GKTodayDocument10 pagesEvolution of Indian Political Party System - GKTodayNerdNo ratings yet

- The Need For Coalition Politics in IndiaDocument5 pagesThe Need For Coalition Politics in Indiaaditi ranaNo ratings yet

- 13 PDFDocument2 pages13 PDFSanyam JakharNo ratings yet

- Party Politics in IndiaDocument4 pagesParty Politics in IndiaEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- National and Regional Political Parties in India - (28-1-2021)Document27 pagesNational and Regional Political Parties in India - (28-1-2021)Jaqen h'gharNo ratings yet

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaDocument22 pagesDamodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiavamsiNo ratings yet

- Political PartiesDocument28 pagesPolitical PartiesswethaNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Political Parties in India: Their Growth and Contribution To The Development of LawDocument16 pagesThe Effectiveness of Political Parties in India: Their Growth and Contribution To The Development of LawAbhipsha MohantyNo ratings yet

- Party System in India: Abreeda Banu B.A L.L.B (Hons.) (2 Semester) (Regular) Political Science II Roll Number:04Document4 pagesParty System in India: Abreeda Banu B.A L.L.B (Hons.) (2 Semester) (Regular) Political Science II Roll Number:04Injila ZaidiNo ratings yet

- Coalition Politics in India An AnalysisDocument6 pagesCoalition Politics in India An AnalysispatelashfaqueNo ratings yet

- Party System in IndiaDocument4 pagesParty System in IndiaMOFIDUL ISLAMNo ratings yet

- Political Science MadiahDocument4 pagesPolitical Science MadiahUmmey Kulsum KhanNo ratings yet

- Delhi CaseDocument11 pagesDelhi CaseArya KrishanNo ratings yet

- Pol SC IIIDocument6 pagesPol SC IIIAshutosh BansalNo ratings yet

- Democracy, Governance and Political Parties in India: An IntroductionDocument10 pagesDemocracy, Governance and Political Parties in India: An IntroductionLNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Indian PoliticsDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Indian Politicsc9sf7pe3100% (1)

- Ncert Solutions For Class 12 Political Science Chapter 2 Era of One Party Dominance PDFDocument13 pagesNcert Solutions For Class 12 Political Science Chapter 2 Era of One Party Dominance PDFUtkarsh TiwariNo ratings yet

- PartySysteminIndia PushpaSinghDocument19 pagesPartySysteminIndia PushpaSinghyyyyyyyyyyNo ratings yet

- 3.20 - Post Independence History Part 3Document20 pages3.20 - Post Independence History Part 3VedantNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11-Era of One-Party Dominance: Challenge of Building DemocracyDocument12 pagesChapter 11-Era of One-Party Dominance: Challenge of Building DemocracyDeepika ITNo ratings yet

- Indian Government and Politics - Ii Cia 3 (Component 1) : Name-Aradhya Class - 4ba LLB REG - NO - 20113009Document4 pagesIndian Government and Politics - Ii Cia 3 (Component 1) : Name-Aradhya Class - 4ba LLB REG - NO - 20113009ARADHYA 20113009No ratings yet

- Notes CH 2 Era of One Party DominanceDocument12 pagesNotes CH 2 Era of One Party DominanceAayushi ParmarNo ratings yet

- Subject: Political Science: A Project On The TopicDocument11 pagesSubject: Political Science: A Project On The Topicmohd sakibNo ratings yet

- Party System in IndiaDocument5 pagesParty System in IndiaSudhanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- 5fb61df7ca40c113f79af497 5e9a092ba8446510cc99fb5a 1615282586341Document15 pages5fb61df7ca40c113f79af497 5e9a092ba8446510cc99fb5a 1615282586341ZULNo ratings yet

- Era of One Party DominanceDocument8 pagesEra of One Party DominanceRamita Udayashankar86% (14)

- Political Process in IndiaDocument24 pagesPolitical Process in IndiaPakhee political scienceNo ratings yet

- Chapter Political PartiesDocument10 pagesChapter Political PartiesAkshay MittalNo ratings yet

- Role of Indian National Congress in Freedom StruggleDocument14 pagesRole of Indian National Congress in Freedom Struggledakshitas983No ratings yet

- Aippm Bgfinal2023Document12 pagesAippm Bgfinal2023Blastik FalconNo ratings yet

- Indian National Congress - BookDocument123 pagesIndian National Congress - Booknikhil_sez1363No ratings yet

- Class 12 NCERT Political Science (2) Chapter 2Document28 pagesClass 12 NCERT Political Science (2) Chapter 2MahthiNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 PDFDocument8 pagesUnit 1 PDFUjala Jangid 4045No ratings yet

- Regional Parties in IndiaDocument5 pagesRegional Parties in IndiaRuat PuiiNo ratings yet

- Political Science - 1 ProjectDocument24 pagesPolitical Science - 1 Projectuma mishraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Political PartiesDocument11 pagesChapter 6 Political PartiesMaria JohncyNo ratings yet

- Political Parties in India. PrajjwalDocument5 pagesPolitical Parties in India. PrajjwalPRAJJWAL BARANWALNo ratings yet

- The Past and Future of The Congress PartyDocument2 pagesThe Past and Future of The Congress PartyShah12No ratings yet

- Indian Public School: Very Important Very-Very ImportantDocument10 pagesIndian Public School: Very Important Very-Very ImportantMithilesh JhaNo ratings yet

- Political Parties ReferenceDocument4 pagesPolitical Parties ReferenceprashantNo ratings yet

- Business Environment: Swot Analysis of Indian National CongressDocument17 pagesBusiness Environment: Swot Analysis of Indian National Congresspkp999No ratings yet

- Political Party and Party SystemDocument19 pagesPolitical Party and Party System17Ashutosh KumarNo ratings yet

- Beyond A Billion Ballots: Democratic Reforms for a Resurgent IndiaFrom EverandBeyond A Billion Ballots: Democratic Reforms for a Resurgent IndiaNo ratings yet

- Financial Analysis ExercisesDocument1 pageFinancial Analysis ExercisesSpencer MosquisaNo ratings yet

- 7.0 Development Constraints: Comprehensive Land Use Plan 2012-2022Document1 page7.0 Development Constraints: Comprehensive Land Use Plan 2012-2022Paul BautistaNo ratings yet

- ApplicationformDocument2 pagesApplicationformSharafat AliNo ratings yet

- Table of FIDIC Cases - 03 07 2023Document49 pagesTable of FIDIC Cases - 03 07 2023Vyom VakhariyaNo ratings yet

- scmv3 (Families of Saltillo, Vol III) - 1736-1749Document551 pagesscmv3 (Families of Saltillo, Vol III) - 1736-1749A. LNo ratings yet

- Investment Pattern Amongst The Residents of Navi Mumbai PGDM 2011-13Document35 pagesInvestment Pattern Amongst The Residents of Navi Mumbai PGDM 2011-13Ishu Rungta تNo ratings yet

- Resume ExampleDocument1 pageResume ExampleK I0NNo ratings yet

- Marginal CostingDocument10 pagesMarginal CostingNishant ModiNo ratings yet

- Ramayana - The Essence of The VedasDocument18 pagesRamayana - The Essence of The Vedasthink_sriNo ratings yet

- Brief: SDG Priorities For BangladeshDocument3 pagesBrief: SDG Priorities For BangladeshMrz AshikNo ratings yet

- CHP 10Document9 pagesCHP 10KhjNo ratings yet

- Fruits Search For WordsDocument1 pageFruits Search For WordsMOHD SHAFUAN BIN ZULKAFLI KPM-GuruNo ratings yet

- Toolkit: Asean Youth IN Climate AC Tion Anddisaster Resilienc E DAY 2 0 2 0Document9 pagesToolkit: Asean Youth IN Climate AC Tion Anddisaster Resilienc E DAY 2 0 2 0Christine Marquez RamosNo ratings yet

- Miscelaneous StampedDocument2 pagesMiscelaneous StampedMohammed ElmakNo ratings yet

- FEWS PolicyDocument15 pagesFEWS PolicyPrince Waqas AliNo ratings yet

- Employment Law For Business 8th Edition Bennett Alexander Test BankDocument24 pagesEmployment Law For Business 8th Edition Bennett Alexander Test Bankrussellmatthewspctjegdyox100% (22)

- National Geographic Afghanistan Hidden TreasuresDocument4 pagesNational Geographic Afghanistan Hidden TreasuresJohnNY_TexNo ratings yet

- 1 Aloandro Ben Bakr - BeatrizDocument1 page1 Aloandro Ben Bakr - BeatrizDavid DayNo ratings yet

- Art. Methodological Issues in Cross Cultural Marketing Research. A State of The Art Review PDFDocument45 pagesArt. Methodological Issues in Cross Cultural Marketing Research. A State of The Art Review PDFM.C MejiaNo ratings yet

- Bill of LadingDocument1 pageBill of LadingJohn Mark VerarNo ratings yet

- Class Notes On Agrobiodiversity Conservation and Climate Change 022Document156 pagesClass Notes On Agrobiodiversity Conservation and Climate Change 022Kabir Singh100% (1)

- Bilingualism and MultilingualismDocument18 pagesBilingualism and MultilingualismKaren Perez100% (1)

- Marketing Channel Strategy International Edition by Robert Palmatier, Louis Stern, Adel El-Ansary (Z-LibDocument497 pagesMarketing Channel Strategy International Edition by Robert Palmatier, Louis Stern, Adel El-Ansary (Z-LibHuỳnh Thị Đông HàNo ratings yet

- FINALLY DTOT Matrix KindergartenDocument3 pagesFINALLY DTOT Matrix KindergartenJaymar Kevin PadayaoNo ratings yet

- Reviewer in RPHDocument6 pagesReviewer in RPHmwuah tskNo ratings yet

- Feb 05 InprocDocument740 pagesFeb 05 InprocaptureincNo ratings yet

- Evidence Cases IIDocument94 pagesEvidence Cases IIAiken Alagban LadinesNo ratings yet