Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 viewsAbm161 Lesson 4 5 2023

Abm161 Lesson 4 5 2023

Uploaded by

Norhaliza D. SaripThis document discusses consumption and investment. It defines consumption as expenditures on final goods and services by households, and defines saving as the portion of disposable income not consumed. It then examines the major components of consumption, including durable goods, nondurable goods, and services. The document also discusses the consumption function and how consumption relates to disposable income. It introduces concepts like the marginal propensity to consume and marginal propensity to save. Finally, it analyzes factors that influence consumption levels, such as current income, permanent income, wealth, and social security systems.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Katz - The Cycle of Dependency 50 Years LaterDocument16 pagesKatz - The Cycle of Dependency 50 Years LaterJonas OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Consumption Savings Investment. ParadoxDocument46 pagesConsumption Savings Investment. ParadoxChristine Joy LanabanNo ratings yet

- Topic 1 - Consumption FunctionDocument13 pagesTopic 1 - Consumption Functionreuben kawongaNo ratings yet

- Chap 22Document18 pagesChap 22Syed HamdanNo ratings yet

- Keynesian Consumption and Investment PDFDocument17 pagesKeynesian Consumption and Investment PDFGayle AbayaNo ratings yet

- Consumption and Investment: I. Chapter OverviewDocument18 pagesConsumption and Investment: I. Chapter OverviewGeorge WagihNo ratings yet

- Consumption and Savings - 1 1Document8 pagesConsumption and Savings - 1 1Anjelika ViescaNo ratings yet

- Consumers and Demand - 2024 - PVDocument92 pagesConsumers and Demand - 2024 - PVsilverphantom9090No ratings yet

- Introduction VT2024Document39 pagesIntroduction VT2024aleema anjumNo ratings yet

- Consumption SavingsDocument68 pagesConsumption SavingskhatedeleonNo ratings yet

- Cas DoneDocument17 pagesCas DoneAiko ArevaloNo ratings yet

- Topic (5) - Theory of National Income DeterminationDocument14 pagesTopic (5) - Theory of National Income Determinationfuck offNo ratings yet

- Consumption and SavingDocument6 pagesConsumption and Savingmah rukhNo ratings yet

- Tor in SS 322 Macroeconomics - BaldonadoDocument10 pagesTor in SS 322 Macroeconomics - Baldonadojemarabermudeztaniza14No ratings yet

- Page One Ce 1114 NewDocument13 pagesPage One Ce 1114 NewMuhammadNasserAL-SaaidyNo ratings yet

- Definition of 'Consumer Spending': A2 Macroeconomics / International EconomyDocument12 pagesDefinition of 'Consumer Spending': A2 Macroeconomics / International EconomyHuzaimah JaiminNo ratings yet

- Law of ConsumptionDocument16 pagesLaw of ConsumptionAnkit JoshiNo ratings yet

- Econ Week 13 Savings and The Financial SystemDocument35 pagesEcon Week 13 Savings and The Financial SystemMeeka CalimagNo ratings yet

- Consumption and SavingsDocument18 pagesConsumption and SavingsAna Ionela ȚepeșNo ratings yet

- Macro Economics: Assignment No. 01Document13 pagesMacro Economics: Assignment No. 01mobeen_shahid100% (2)

- Week 2 Fighting RecessionDocument42 pagesWeek 2 Fighting Recessiondaisyruyu2001No ratings yet

- Consumption FunctionDocument31 pagesConsumption Functionscottsummers39No ratings yet

- Final ProjectDocument16 pagesFinal ProjectIlma LatansaNo ratings yet

- Macro - Module - 16 3Document23 pagesMacro - Module - 16 3AlexNo ratings yet

- Session#5 SummaryDocument7 pagesSession#5 SummaryPranav ONo ratings yet

- Consumption and SavingsDocument3 pagesConsumption and SavingsTrixzy MargalloNo ratings yet

- Reading Lesson 1Document9 pagesReading Lesson 1AnshumanNo ratings yet

- Consumer Spending - Tutor2uDocument7 pagesConsumer Spending - Tutor2utheone1998No ratings yet

- Trends in Consumption, Savings and Investment 1Document20 pagesTrends in Consumption, Savings and Investment 1Eashaa SaraogiNo ratings yet

- Business Economics - PPTX Group 4Document28 pagesBusiness Economics - PPTX Group 4irsamNo ratings yet

- Towards Relevant Education For All: National Income AccountingDocument7 pagesTowards Relevant Education For All: National Income AccountingJun Mark Balasico YaboNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Macroeconomics: After Reading This Section, You Should Be Able ToDocument33 pagesIntroduction To Macroeconomics: After Reading This Section, You Should Be Able ToKhaster NavarraNo ratings yet

- Economics AssianmentDocument5 pagesEconomics Assianmentsultana nasirNo ratings yet

- Public Finance Lecture Notes Gruber Chapter 2Document22 pagesPublic Finance Lecture Notes Gruber Chapter 2Hiram CortezNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 Notes Aggregate Expenditure ModelDocument14 pagesChapter 8 Notes Aggregate Expenditure ModelBeatriz CanchilaNo ratings yet

- Principles of Macro CourseworkDocument4 pagesPrinciples of Macro CourseworkgrfyfqsywvNo ratings yet

- MAACROECONOMICSDocument36 pagesMAACROECONOMICSSIEER LONE (RA2011033010151)No ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Macroeconomics Principles Applications and Tools 8 e 8th Edition Arthur Osullivan Steven Sheffrin Stephen PerezDocument16 pagesSolution Manual For Macroeconomics Principles Applications and Tools 8 e 8th Edition Arthur Osullivan Steven Sheffrin Stephen PerezVanessaMerrittdqes100% (38)

- Macroeconomics Canadian 5th Edition Williamson Solutions ManualDocument35 pagesMacroeconomics Canadian 5th Edition Williamson Solutions Manualsinapateprear4k100% (21)

- Consumption Function and MultiplierDocument24 pagesConsumption Function and MultiplierVikku AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Government Spending - Is The Sum ofDocument3 pagesGovernment Spending - Is The Sum ofBenedectine SalongaNo ratings yet

- Consumption and SavingDocument21 pagesConsumption and SavingShannon MojicaNo ratings yet

- GDP Expenditures EquationDocument24 pagesGDP Expenditures EquationlocketblaqNo ratings yet

- Ans. To. The. Q. No. 1 (A)Document4 pagesAns. To. The. Q. No. 1 (A)sultana nasirNo ratings yet

- Consumption FunctionDocument31 pagesConsumption FunctionDeepak MittalNo ratings yet

- Module 1Document4 pagesModule 1Annabelle MancoNo ratings yet

- LECTURE 3 Equilibrium Im Product MarketDocument50 pagesLECTURE 3 Equilibrium Im Product MarketNeha SinghNo ratings yet

- Session 1Document3 pagesSession 1Abhinav SahrmaNo ratings yet

- Eco, ch-26 Consumption and SavingDocument7 pagesEco, ch-26 Consumption and Savingaminaabdulaziz2005No ratings yet

- Consumption Is An Increasing Function of IncomeDocument18 pagesConsumption Is An Increasing Function of IncomeRajesh Lamba100% (1)

- KWe3 Macro Ch6SelectedDocument26 pagesKWe3 Macro Ch6SelectedMichael DCNo ratings yet

- Eco Imp Sem-2Document15 pagesEco Imp Sem-2saharshreddyNo ratings yet

- Basic of BudgetDocument6 pagesBasic of Budgetahmedabad management association AhmedabadNo ratings yet

- Unit IDocument27 pagesUnit Iarnav.mi2006No ratings yet

- Intro To MacroeconDocument31 pagesIntro To MacroeconYrence OliveNo ratings yet

- Keynes LawDocument7 pagesKeynes LawNaresh KumawatNo ratings yet

- Theory of ConsumptionDocument61 pagesTheory of Consumptionpalakagrawal2216No ratings yet

- Eco Dev MidtermDocument6 pagesEco Dev MidtermGlenn VeluzNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 Topics 1,2 and 3Document143 pagesUnit 4 Topics 1,2 and 3Nicholas ThamNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics III: Consumption and Investment: Gavin Cameron Lady Margaret HallDocument21 pagesMacroeconomics III: Consumption and Investment: Gavin Cameron Lady Margaret HallIrina StefanaNo ratings yet

- Efficient Ways to Maintain Your Finances: Budgeting, Retirement Plan, Passive Income & Personal FinanceFrom EverandEfficient Ways to Maintain Your Finances: Budgeting, Retirement Plan, Passive Income & Personal FinanceNo ratings yet

- Abm161 Lessons 10 11 2023Document48 pagesAbm161 Lessons 10 11 2023Norhaliza D. SaripNo ratings yet

- Agrarian Reform After Lesson 67Document24 pagesAgrarian Reform After Lesson 67Norhaliza D. SaripNo ratings yet

- Abm161 Lesson 1. Overview of Macroeconomics 2022Document55 pagesAbm161 Lesson 1. Overview of Macroeconomics 2022Norhaliza D. SaripNo ratings yet

- The Agribusiness Group1 2Document33 pagesThe Agribusiness Group1 2Norhaliza D. SaripNo ratings yet

- Group 2 ABM83Document18 pagesGroup 2 ABM83Norhaliza D. SaripNo ratings yet

- Lesson 14 ABM161 Taxation For FinalsDocument41 pagesLesson 14 ABM161 Taxation For FinalsNorhaliza D. SaripNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics Syllabus 2Document3 pagesMacroeconomics Syllabus 2chhetribharat08No ratings yet

- Composite Indexes and Diffusion Indexe1Document7 pagesComposite Indexes and Diffusion Indexe1AaruniNo ratings yet

- Business Taxation MaterialDocument18 pagesBusiness Taxation MaterialKhushboo ParikhNo ratings yet

- British Economic Growth and The Business Cycle 1700-1850Document48 pagesBritish Economic Growth and The Business Cycle 1700-1850Sabrina CanţîrNo ratings yet

- Aggregate Demand & Supply of LabourDocument68 pagesAggregate Demand & Supply of Labourankit gogriNo ratings yet

- Sample Test hp4Document5 pagesSample Test hp4Thư MaiNo ratings yet

- StagflationDocument5 pagesStagflationKunal JainNo ratings yet

- Parle Working Capital AshishDocument72 pagesParle Working Capital Ashishkksomani21100% (1)

- MegaQuizFileECO401byShahzadSadiq PDFDocument273 pagesMegaQuizFileECO401byShahzadSadiq PDFFərruxXəmənNo ratings yet

- Fiscal Policy For Sustainable Development in Asia Pacific Lekha S Chakraborty Full ChapterDocument67 pagesFiscal Policy For Sustainable Development in Asia Pacific Lekha S Chakraborty Full Chapterhelen.hamler923100% (15)

- Making Money For Business: Currencies, Profit, and Long-Term Thinking by B. Lietaer and G. HallsmithDocument6 pagesMaking Money For Business: Currencies, Profit, and Long-Term Thinking by B. Lietaer and G. Hallsmithuser909No ratings yet

- (Globalization, Crises, and Change) Berch Berberoglu - Beyond The Global Capitalist Crisis - The World Economy in Transition (2011, Ashgate) PDFDocument218 pages(Globalization, Crises, and Change) Berch Berberoglu - Beyond The Global Capitalist Crisis - The World Economy in Transition (2011, Ashgate) PDFwalter blanquiNo ratings yet

- BBM Sylabus PDFDocument35 pagesBBM Sylabus PDFAjay DhawalNo ratings yet

- Economic Boom and Effects. Some Solutions of The UK GovernmentDocument4 pagesEconomic Boom and Effects. Some Solutions of The UK Governmenttuan sonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 IntroDocument14 pagesChapter 1 IntroliyayudiNo ratings yet

- The Long Waves of Economic Life - KondratievDocument80 pagesThe Long Waves of Economic Life - KondratievIlias FilisNo ratings yet

- Aggregate Demand & Supplu ModelDocument20 pagesAggregate Demand & Supplu ModelShajeer HamNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Business Cycle-1Document6 pagesCase Study On Business Cycle-1ASAD ULLAHNo ratings yet

- Bab 1 Pengantar Bisnis Buku GriffinDocument47 pagesBab 1 Pengantar Bisnis Buku GriffinSiti Auli Yanti NurbachNo ratings yet

- Company AnalysisDocument84 pagesCompany AnalysisShantnu SoodNo ratings yet

- Pool of Questions of Economix Quizbee 2013Document17 pagesPool of Questions of Economix Quizbee 2013John Vincent Pardilla100% (1)

- Treasury Management: Module 1 Chapter 3: Cash ForecastingDocument40 pagesTreasury Management: Module 1 Chapter 3: Cash ForecastingAUMBRIELL GOMEZNo ratings yet

- Commodity Price VolatilityDocument36 pagesCommodity Price VolatilityhertinaNo ratings yet

- Economics Project New 2Document53 pagesEconomics Project New 2humphreyoluoch97No ratings yet

- AD AS QuestionsDocument15 pagesAD AS QuestionsRizka SyarifNo ratings yet

- Economic Principles 201819Document27 pagesEconomic Principles 201819Fortunatus JuliusNo ratings yet

- Chapter One Economic Thought Before Adam SmithDocument130 pagesChapter One Economic Thought Before Adam SmithbopgalebelayNo ratings yet

- Final KEC ReportDocument116 pagesFinal KEC Reports2410100% (4)

- Intevju Robert Aliber PDFDocument4 pagesIntevju Robert Aliber PDFalpar7377No ratings yet

Abm161 Lesson 4 5 2023

Abm161 Lesson 4 5 2023

Uploaded by

Norhaliza D. Sarip0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views57 pagesThis document discusses consumption and investment. It defines consumption as expenditures on final goods and services by households, and defines saving as the portion of disposable income not consumed. It then examines the major components of consumption, including durable goods, nondurable goods, and services. The document also discusses the consumption function and how consumption relates to disposable income. It introduces concepts like the marginal propensity to consume and marginal propensity to save. Finally, it analyzes factors that influence consumption levels, such as current income, permanent income, wealth, and social security systems.

Original Description:

Original Title

ABM161-LESSON-4-5-2023

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document discusses consumption and investment. It defines consumption as expenditures on final goods and services by households, and defines saving as the portion of disposable income not consumed. It then examines the major components of consumption, including durable goods, nondurable goods, and services. The document also discusses the consumption function and how consumption relates to disposable income. It introduces concepts like the marginal propensity to consume and marginal propensity to save. Finally, it analyzes factors that influence consumption levels, such as current income, permanent income, wealth, and social security systems.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views57 pagesAbm161 Lesson 4 5 2023

Abm161 Lesson 4 5 2023

Uploaded by

Norhaliza D. SaripThis document discusses consumption and investment. It defines consumption as expenditures on final goods and services by households, and defines saving as the portion of disposable income not consumed. It then examines the major components of consumption, including durable goods, nondurable goods, and services. The document also discusses the consumption function and how consumption relates to disposable income. It introduces concepts like the marginal propensity to consume and marginal propensity to save. Finally, it analyzes factors that influence consumption levels, such as current income, permanent income, wealth, and social security systems.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 57

CHAPTER 4

CONSUMPTION AND INVESTMENT

Prepared by: SKM

CONSUMPTION & SAVING

▪ Consumption (or, more precisely, personal

consumption expenditures) is expenditures by

households on final goods and services. Saving

is the part of personal disposable income that

is not consumed

▪ Consumption is the largest single component

of GDP, constituting 66 percent of total

spending over the last decade. What are the

major elements of consumption? Among the

most important categories are housing, motor

vehicles, food, and medical care.

Prepared by: SKM

▪ The table in the next slide displays the major

elements, broken down into three categories of

durable goods, nondurable goods, and

services. The items themselves are familiar, but

their relative importance, particularly the

increasing importance of services, is worth a

moment’s study

Prepared by: SKM

THE MAJOR COMPONENTS OF CONSUMPTION

Category of consumption

Durable goods

Motor vehicles & parts

Furniture & household equipment

Other

Nondurable goods

Food

Clothing & shoes

Energy goods

Other

Services

Housing

Household operation

Transportation

Medical care

Recreation

Other

Total personal consumption expenditures

Prepared by: SKM

BUDGETARY EXPENDITURE PATTERNS

▪ Poor families must spend their incomes

largely on the on the necessities of life: food

and shelter. As income increases,

expenditure on many food items goes up.

People more and eat better. There are,

however, limits to the extra money people

will spend on food when their incomes rise.

Consequently, the proportion of total

spending devoted to food declines as

income rises.

Prepared by: SKM

CONSUMPTION, INCOME, & SAVING

▪ Income, consumption, and saving are all closely

linked. More precisely, personal saving is that

part of disposable income that is not consumed;

saving equals income consumption. To

understand the way consumption affects

national output, we need to introduce some new

tools. We need to understand how many extra

dollars of consumption & saving are induced by

each extra dollar of income. This relationship is

shown by:

1. The consumption function, relating to

consumption & income

2. Its twin, the saving function, relates saving &

income

Prepared by: SKM

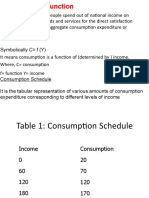

THE CONSUMPTION FUNCTION

▪ One of the most important relationships in

all macroeconomics is the consumption

function. The consumption function shows

the relationship between the level of

consumption expenditures and the level of

disposable personal income. This concept,

introduced by Keynes, is based on the

hypothesis that there is a stable empirical

relationship between consumption and

income

Prepared by: SKM

A PLOT OF THE CONSUMPTION FUNCTION

Prepared by: SKM

▪ The curve through A, B, C…G is the consumption

function. The horizontal axis depicts the level of

disposable income (DI). For each level of DI, the

consumption function shows the dollar level of

consumption (C) for the household. Note that

consumption rises with increases in DI. The 45

degrees line helps locate the break-even point

and helps our eye measure net saving

▪ The break-even point on the consumption

schedule that intersects the 45-degree line

represents the level of disposable income at

which households just break even

Prepared by: SKM

THE SAVING FUNCTION

▪ The saving function shows the relationship

between the level of saving and income. This

is shown graphically in the next slide. Again,

we show disposable income on the horizontal

axis; but now saving, whether negative or

positive in amount, is on the vertical axis

▪ This saving schedule is derived by

subtracting consumption from income.

Graphically, the saving function is obtained

by subtracting vertically the consumption

function from the 45-degree line in the next

slide. Note that the break-even point B is at

the same $25,000 income level as in the

previous slide

Prepared by: SKM

THE SAVING FUNCTION IS THE MIRROR

IMAGE OF THE CONSUMPTION FUNCTION

Prepared by: SKM

THE MARGINAL PROPENSITY TO CONSUME

▪ Modern macroeconomics attaches much

importance to the response of consumption

to changes in income. This concept is called

the marginal propensity to consume, or MPC

▪ The marginal propensity to consume is the

extra amount that people consume when

they receive an extra dollar of disposable

income

Prepared by: SKM

THE MARGINAL PROPENSITY TO SAVE

▪ Along with the marginal propensity to

consume goes its mirror image, the marginal

propensity to save is defined as the fraction

of an extra dollar of disposable income that

goes to extra saving

▪ MPC + MPS = 1, always and everywhere

Prepared by: SKM

BRIEF REVIEW OF DEFINITIONS

▪ 1. The consumption function relates the level

of consumption to the level of disposable

income

▪ 2. The saving function relates the saving to

disposable income. Because what is saved

equals what is not consumed, saving and

consumption schedules are mirror images

▪ 3. The marginal propensity to consume

(MPC) is the amount of extra consumption

generated by an extra dollar by the slope of

the consumption function

Prepared by: SKM

NATIONAL CONSUMPTION BEHAVIOR

▪ We begin by examining economic activity on

the individual level and then add up or

aggregate the totality of individuals to study the

way the overall economy operates

▪ Consumption behavior is crucial because what

is not consumed – that is, what is saved – is

available to the nation for investment in new

capital goods; capital serves as a driving force

behind long-term economic growth.

Consumption and saving behavior is key to

understanding economic and business cycles

Prepared by: SKM

DETERMINANTS OF CONSUMPTION

▪ We begin by analyzing the major forces that

affect consumer spending. What factors in a

nation’s life and livelihood set the pace of its

consumption outlays (expenses)?

▪ Current disposable income. Both observation

and statistical studies show that the current

level of disposable income is the central

factor determining a nation’s consumption

Prepared by: SKM

▪ Permanent income and the life-cycle model of

consumption. The simplest theory of

consumption uses only the current year’s income

to predict consumption expenditures. Consider

the following examples, which suggest

otherwise:

If bad weather destroys a crop, farmers will

draw upon their previous savings. Similarly, law-

school students borrow for consumption

purposes while in school because they believe

that their postgraduate income will be much

higher than their meager student earnings

Prepared by: SKM

▪ In both these circumstances, people are in effect

asking, “Given my current and future income,

how much can I consume today without incurring

excessive debts?

▪ Permanent income is the trend level of income –

that is, income after removing temporary or

transient influences due to the weather or

windfall gains or losses. According to the

permanent-income theory, consumption

responds primarily to permanent income. If a

change in income appears permanent (such as

being promoted to a secure and high-paying

job), people are likely to consume a large

fraction of the increase in income

Prepared by: SKM

▪ The life-cycle hypothesis assumes that people

save in order to smooth their consumption over

their lifetime. One important objective is to

have an adequate retirement income. Hence,

people tend to save while working so as to

build up a nest egg for retirement ad then

spend out their accumulated savings in their

twilight years

Prepared by: SKM

WEALTH AND OTHER INFLUENCES

▪A further important determinant of the

amount of consumption is wealth. Consider

two consumers, both earning $50,000 per

year. One has $200,000 in the bank, while the

other has no savings at all. The first person

may consume part of wealth, while the

second has no wealth to draw. The fact that

higher wealth leads to higher consumption

is called the wealth effect

Prepared by: SKM

REASONS FOR THE SHARP DECLINE IN THE PERSONAL

SAVING RATE

▪ Social security system. Some economists argue that the social

security system has removed some of the need for private

savings. In earlier times, as the life cycle model of

consumption suggests, a household would save during

working years to build up a nest egg for retirement

Capital markets. Until recently, capital markets had numerous

imperfections. People found it hard to borrow funds for

worthwhile purposes, whether for buying a house, financing an

education, or starting a business. As capital markets

developed, often with the help of the government, new loan

instruments allowed people to borrow easily. One example is

the proliferation (increase) of credit cards, which encourage

people to borrow (even though the interest rates are quite

high)

▪ The rapid growth in wealth. Part of the decline in personal

savings in the 1990s was surely caused by the rapid increase in

personal wealth

Prepared by: SKM

ALTERNATIVE MEASURES OF SAVING

▪ The national-accounts measure of saving is the

difference between disposable income

(excluding capital gains) and consumption. The

balance sheet measure of saving calculates the

change in the real net worth (that is, assets

fewer liabilities, corrected for inflation) from

one year to the next; this measure includes real

capital gains

Prepared by: SKM

B. INVESTMENT

▪ The second major component of private spending

is an investment. Investment plays two roles in

macroeconomics. First, because it is a large and

volatile (unstable) component of spending,

investment often leads to changes in aggregate

demand and affects the business cycle. In

addition, investment leads to capital accumulation.

Adding to the stock of buildings and equipment

increases the nation’s potential output and

promotes economic growth in the long run.

▪ Thus, investment plays a dual role, affecting short-

run output through its impact on aggregate

demand and influencing long-run output growth

through the impact of capital formation on

potential output ad aggregate supply

Prepared by: SKM

DETERMINANTS OF INVESTMENT

▪ Three elements essential to understanding

investment: revenues, costs, and expectations

▪ Revenues. An investment will bring the firm

additional revenue if it helps the firm sell more

products. This suggests that the overall level of

output (or GDP) will be an important

determinant of investment. When factories are

lying idle, firms have relatively little need for

new factories, so the investment is low. More

generally, investment depends upon the

revenues that will be generated by the state of

overall economic activity

Prepared by: SKM

▪ Costs. A second important determinant of the

level of investment is the costs of investing.

Because investment goods last many years,

reckoning (considering) the costs of the

investment is somewhat more complicated than

doing so for other commodities like coal or

wheat. For durable goods, the cost of capital

includes not only the price of the capital good

but also the interest rate that borrowers pay to

finance the capital as well as the taxes that

firms pay o their incomes

Prepared by: SKM

▪ Expectations. The third element in the

determination of investment is profit

expectations and business confidence.

Investment is, above all, a gamble on the future,

a bet that the revenue from an investment will

exceed its costs. If businesses are concerned

that political conditions in Russia are unstable,

they will be reluctant to invest there.

Conversely, because businesses believe

(rightly or wrongly) that Internet commerce will

be an important feature of the distribution

network, they are investing heavily in that

sector

Prepared by: SKM

THE INVESTMENT DEMAND CURVE

▪ In analyzing the determinants of investment,

we focus particularly on the relationship

between interest rates and investment. This

linkage is crucial because interest rates

(influenced by central banks) are the major

instrument by which governments influence

investment. To show the relationship

between interest rates and investment,

economists use a schedule called the

investment demand curve

Prepared by: SKM

INVESTMENT DEPENDS

UPON INTEREST RATE

Prepared by: SKM

INVESTMENT DEPENDS UPON INTEREST RATES

▪ The downward sloping demand-for-

investment schedule plots the amount that

businesses would invest at each interest rate.

Each step represents a lump of investment:

project A has such a high rate that it is off the

figure; the highest visible step is project B,

shown at the upper left. At each interest rate,

all investments that have positive net profit

will be undertaken

Prepared by: SKM

ON THE THEORY OF AGGREGATE DEMAND

▪ We have now completed our introduction to the

basic concepts of macroeconomics. We have

examined the determinants of consumption and

investment and seen how they can fluctuate from

year to year, sometimes quite sharply

▪ At this point, macroeconomics branches into one

of two major themes – business cycles ad

economic growth. In the chapters that follow, we

begin our survey of business cycles or the

behavior of the economy in the short run. This

approach, known as Keynesian economics, shows

how changes in investment, government spending

& taxation, foreign trade, and the money supply

can be transmitted to the rest of the economy

Prepared by: SKM

CHAPTER 5

BUSINESS CYCLES

AND THE THEORY

OF AGGREGATE DEMAND

Prepared by: SKM

BUSINESS FLUCTUATIONS HAVE BEEN A

PERSISTENT FEATURE OF CAPITALISM

Prepared by: SKM

BUSINESS FLUCTUATIONS

▪A country may enjoy several years of

exhilarating economic expansion and

prosperity, as the United States did in the

1990s. This might be followed by a recession

or even a financial crisis or, on rare

occasions, a prolonged depression. Then

national output falls, profits and real incomes

decline, ad the unemployment rate jumps to

uncomfortably high levels as legions

(crowd) of workers lose their jobs

Prepared by: SKM

▪ Eventually the bottom is reached, and

recovery begins. The recovery may be slow

or fast. It may be incomplete, or it may be so

strong as to lead to a new boom. Prosperity

may mean a log, sustained period of brisk

demand, plentiful jobs, and rising living

standards. Or it may be marked by a quick,

inflationary flaring up of prices and

speculation, to be followed by another

slump

▪ Upward and downward movements in

output, inflation, interest rates, and

employment form the business cycle that

characterizes all market economies

Prepared by: SKM

FEATURES OF THE BUSINESS CYCLE

▪ Business cycles are economy-wide

fluctuations in total national output, income,

and employment, usually lasting for a period

of 2 to 10 years, marked by widespread

expansion or contraction in most sectors of the

economy

▪ Typically, economists divide business cycles

into two main phases, recession, and

expansion. Peaks and troughs (channels)

market the turning points of the cycles

Prepared by: SKM

▪ Recession is a recurring (reappearing) period

of decline in total output, income, ad

employment, usually lasting from 6 months to

a year and marked by widespread

contractions in many sectors of the economy

▪ Depression is a recession that is major in both

scale (size) and duration

▪ Although we call short-term fluctuations

“cycles”, the actual pattern is irregular. O two

business cycles are quite the same. No exact

formula, such as might apply to the revolutions

of planets or the swings of a pendulum, can be

used to predict the duration and timing of

business cycles

Prepared by: SKM

The following are a few of the customary

characteristics of a recession:

▪ a. consumer purchases decline sharply,

while business inventories of automobiles

and other durable goods increase

unexpectedly.

▪ b. As businesses react by curbing (limiting)

production, real GDP falls.

▪ c. Shortly afterward, business investment in

plant and equipment also falls sharply

Prepared by: SKM

▪ d. The demand for labor falls (layoffs and

higher unemployment)

▪ e. Demand for crude (basic) materials

declines, and their prices tumble. Wages

and prices of services are unlikely to

decline, but they tend to rise less rapidly

in economic downturns

▪ f. Business profits fall sharply in

recessions. Common-stock prices usually

fall, the demand for credit falls, and

interest rates generally also fall

Prepared by: SKM

BUSINESS-CYCLE THEORIES

▪ Exogenous vs. internal cycles. Over the years

macroeconomics has been vigorous (strong) debates

about the sources of business cycles. Why do

employment and output change directions so

suddenly? Why should market economies blow hot and

cold?

▪ The exogenous theories find the sources of the

business cycle in the fluctuations of factors outside the

economic system – in wars, revolutions, and elections;

in oil prices, gold discoveries, and migrations; in

discoveries of new lands & resources; in scientific

breakthroughs and technological innovations; even in

sunspots, climate change, or the weather

Prepared by: SKM

▪ An example of an exogenous cycle was the

discovery of the New World. When

explorers began to return to Europe with

their treasures, this led to an increase in

the amount of monetary silver and gold,

increasing prices and leading to economic

expansion. Here we saw an exogenous

event – the discovery of America –

producing an economic expansion

Prepared by: SKM

▪ By contrast, the internal theories look for

mechanisms within the economic system itself that

give rise to self-generating business cycles. In this

approach, every expansion breeds recession and

contraction, ad every contraction breeds revival ad

expansion – in a quest-regular, repeating chain.

▪ One important case is the multiplier-accelerator

theory. According to the accelerator principle, rapid

output growth stimulates investment. High investment

in turn stimulates more output growth, and the

process continues until the capacity of the economy

is reached, at which point the economic growth rate

slows. The slower growth in turn reduces investment

spending ad inventory accumulation, which tends to

send the economy into a recession

Prepared by: SKM

DEMAND-INDUCED CYCLES

▪ One important source of business fluctuations

is shocked to aggregate demand

▪ Business-cycle fluctuations in output,

employment, and prices are often caused by

shifts in aggregate demand.

▪ These occur as consumers, businesses, or

governments change total spending relative to

the economy’s productive capacity.

▪ When these shifts in aggregate demand led to

sharp business downturns, the economy suffers

recessions or even depressions. A sharp upturn

in economic activity can lead to inflation

Prepared by: SKM

ECONOMIC MODELING & FORECASTING

▪ In an early are, economists tried to peer into the

future by looking are easily available data on

items like money, boxcar loadings, and steel

production. For example, a drop in steel

production was a sign that businesses would

soon slow down

▪ For amore detailed look into the future,

economists turn to computerized econometric

forecasting models. An econometric model is a

set of equations, representing the behavior of the

economy, that has been estimated using

historical data

Prepared by: SKM

B. FOUNDATIONS OF AGGREGATE DEMAND

▪ The time has come to explore in depth the

foundations of aggregate demand.

▪ What are the major components of aggregate

demand?

▪ How do they interact with aggregate supply to

determine output & prices?

▪ We now look at aggregate demand in more detail

in order to get a better understanding of the

forces which drive the economy. In the next

chapter, we derive the simplest model of

aggregate demand – the multiplier model

Prepared by: SKM

▪ Aggregate demand (AD) is the total or

aggregate quantity of output that is willingly

bought at a given level of prices, other things

held constant. AD is the desired spending in

all product sectors: consumption, private

domestic investment, government purchases

of goods and services, and net exports. It has

four components:

▪ 1. Consumption. As we saw in the last chapter,

consumption (C) is primarily determined by

disposable income, which is personal income

less taxes. Other factors affecting consumption

are long-term trends in income, household

wealth, and the aggregate price level

Prepared by: SKM

▪ Investment. Investment (I) spending includes

purchases of buildings, software, and

equipment and the accumulation of

inventories. Our analysis in chapter 22

showed that the major determinants of

investment are the level of output, the cost of

capital (as determined by tax policies along

with interest rates and other financial

conditions), and expectations about the

future. The major channel by which economic

policy can affect investment in monetary

policy

Prepared by: SKM

▪ 3. Government purchases. The third

component of aggregate demand is

government purchases of goods and

services (G): purchases of goods like tanks

or road-building equipment as well as the

services of judges and public-school

teachers. Unlike private consumption and

investment, this component of aggregate

demand is determined directly by the

government’s spending decisions; when the

Pentagon buys a new fighter aircraft, this

output directly adds to the GDP

Prepared by: SKM

▪ 4. Net exports. A final component of aggregate

demand is net exports (X), which equal the

value of exports minus the value of imports.

Imports are determined by domestic income

and output, by the ratio of domestic to foreign

prices, and by the foreign exchange rate of the

dollar. Exports (which are imports of other

countries) are the mirror of image of imports,

determined by foreign income ad outputs, by

relative prices, and by foreign exchange rates.

Net exports, then, will be determined by

domestic and foreign incomes, relative prices,

and exchange rates

Prepared by: SKM

COMPONENTS OF AGGREGATE DEMAND

Prepared by: SKM

▪ Aggregate demand (AD) consists of four

components – consumption (C), domestic

private investment (I), government spending

on goods & services (G), and net exports.

▪ Aggregate demand shifts when there are

changes in macroeconomic policies (such as

monetary-policy changes or changes in

government expenditures or tax rates) or

when exogenous events change spending (as

would be the case with changes in foreign

output, affecting X, or in business confidence,

affecting I)

Prepared by: SKM

MANY FACTORS CAN INCREASE AGGREGATE DEMAND AND SHIFT

OUT THE AD CURVE

Policy Variables

Variable Impact on Aggregate demand

Monetary policy Increase in money supply lowers interest rates

and relaxes credit conditions, inducing high levels of

investment and consumption of durable goods.

In an open economy, monetary policy affects the

exchange rate and net exports

Fiscal policy Increase in government purchases of goods and

services direct increases spending; tax reductions

or increases in transfers raise disposable income

and induce higher consumption. Tax incentives

like an investment tax credit can induce higher

spending in a particular sector

Prepared by: SKM

MANY FACTORS CAN INCREASE AGGREGATE DEMAND AND SHIFT

OUT THE AD CURVE

Policy Variables Impact on Aggregate demand

Monetary policy • Increase in money supply lowers interest rates and

relaxes credit conditions,

• Inducing high level of investment and consumption

of durable goods.

• In an open economy, monetary policy affects the

exchange rate and net exports

Fiscal policy • Increase in government purchases of goods and

services direct increases spending;

• Tax reductions or increases in transfers raise

disposable income and induce higher consumption.

• Tax incentives like an investment tax credit can

induce higher spending in a particular sector

Prepared by: SKM

MANY FACTORS CAN INCREASE AGGREGATE DEMAND AND SHIFT OUT THE AD CURVE

Exogenous variables Impact on Aggregate demand

Foreign output exports • Output growth abroad leads to an increase in net

exports

Asset values • Rise in stock market increases household wealth

and thereby increases consumption;

• also, this leads to lower cost of capital and

increases business investment

Advances in technology • Technological advances can open up new

opportunities for business investment.

• Important examples have been the railroad, the

automobile, and the computers

Others • Political events, free-trade agreements, and the end

of the cold war promote business and consumer

confidence and increase spending on investment

and consumer durables

Prepared by: SKM

RELATIVE IMPORTANCE OF FACTORS INFLUENCING DEMAND

▪ Some economists concentrate primarily on

monetary forces in analyzing movements in

aggregate demand, especially stressing the role

of the money supply.

▪ According to these economists, who are often

called monetarists, the supply of money is the

primary determinant of the total dollar value of

spending

▪ Other economists focus on exogenous factors

instead. For example, some have argued that

technological progress is one of the key

determinants of booms and busts

Prepared by: SKM

▪ Economists looking at the 1990s have

concluded that the fundamental

technological changes in computer

hardware, software, and communications

have triggered rapid declines in prices in

that sector and in the economy; have led

to a significant increase in the overall

potential growth of the economy; and

have produced a remarkable increase in

investment

Prepared by: SKM

IS THE BUSINESS CYCLE AVOIDABLE?

▪ Recessions are now generally considered to

be fundamentally preventable, like airplane

crashes and hurricanes.

▪ But we have not banished air crashes from the

land, and it is not clear that we have the

wisdom or the ability to eliminate recessions.

▪ The danger has not disappeared. The forces

that produce recurrent recessions are still in

the wings, merely waiting for their cue

Prepared by: SKM

Prepared by: SKM

You might also like

- Katz - The Cycle of Dependency 50 Years LaterDocument16 pagesKatz - The Cycle of Dependency 50 Years LaterJonas OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Consumption Savings Investment. ParadoxDocument46 pagesConsumption Savings Investment. ParadoxChristine Joy LanabanNo ratings yet

- Topic 1 - Consumption FunctionDocument13 pagesTopic 1 - Consumption Functionreuben kawongaNo ratings yet

- Chap 22Document18 pagesChap 22Syed HamdanNo ratings yet

- Keynesian Consumption and Investment PDFDocument17 pagesKeynesian Consumption and Investment PDFGayle AbayaNo ratings yet

- Consumption and Investment: I. Chapter OverviewDocument18 pagesConsumption and Investment: I. Chapter OverviewGeorge WagihNo ratings yet

- Consumption and Savings - 1 1Document8 pagesConsumption and Savings - 1 1Anjelika ViescaNo ratings yet

- Consumers and Demand - 2024 - PVDocument92 pagesConsumers and Demand - 2024 - PVsilverphantom9090No ratings yet

- Introduction VT2024Document39 pagesIntroduction VT2024aleema anjumNo ratings yet

- Consumption SavingsDocument68 pagesConsumption SavingskhatedeleonNo ratings yet

- Cas DoneDocument17 pagesCas DoneAiko ArevaloNo ratings yet

- Topic (5) - Theory of National Income DeterminationDocument14 pagesTopic (5) - Theory of National Income Determinationfuck offNo ratings yet

- Consumption and SavingDocument6 pagesConsumption and Savingmah rukhNo ratings yet

- Tor in SS 322 Macroeconomics - BaldonadoDocument10 pagesTor in SS 322 Macroeconomics - Baldonadojemarabermudeztaniza14No ratings yet

- Page One Ce 1114 NewDocument13 pagesPage One Ce 1114 NewMuhammadNasserAL-SaaidyNo ratings yet

- Definition of 'Consumer Spending': A2 Macroeconomics / International EconomyDocument12 pagesDefinition of 'Consumer Spending': A2 Macroeconomics / International EconomyHuzaimah JaiminNo ratings yet

- Law of ConsumptionDocument16 pagesLaw of ConsumptionAnkit JoshiNo ratings yet

- Econ Week 13 Savings and The Financial SystemDocument35 pagesEcon Week 13 Savings and The Financial SystemMeeka CalimagNo ratings yet

- Consumption and SavingsDocument18 pagesConsumption and SavingsAna Ionela ȚepeșNo ratings yet

- Macro Economics: Assignment No. 01Document13 pagesMacro Economics: Assignment No. 01mobeen_shahid100% (2)

- Week 2 Fighting RecessionDocument42 pagesWeek 2 Fighting Recessiondaisyruyu2001No ratings yet

- Consumption FunctionDocument31 pagesConsumption Functionscottsummers39No ratings yet

- Final ProjectDocument16 pagesFinal ProjectIlma LatansaNo ratings yet

- Macro - Module - 16 3Document23 pagesMacro - Module - 16 3AlexNo ratings yet

- Session#5 SummaryDocument7 pagesSession#5 SummaryPranav ONo ratings yet

- Consumption and SavingsDocument3 pagesConsumption and SavingsTrixzy MargalloNo ratings yet

- Reading Lesson 1Document9 pagesReading Lesson 1AnshumanNo ratings yet

- Consumer Spending - Tutor2uDocument7 pagesConsumer Spending - Tutor2utheone1998No ratings yet

- Trends in Consumption, Savings and Investment 1Document20 pagesTrends in Consumption, Savings and Investment 1Eashaa SaraogiNo ratings yet

- Business Economics - PPTX Group 4Document28 pagesBusiness Economics - PPTX Group 4irsamNo ratings yet

- Towards Relevant Education For All: National Income AccountingDocument7 pagesTowards Relevant Education For All: National Income AccountingJun Mark Balasico YaboNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Macroeconomics: After Reading This Section, You Should Be Able ToDocument33 pagesIntroduction To Macroeconomics: After Reading This Section, You Should Be Able ToKhaster NavarraNo ratings yet

- Economics AssianmentDocument5 pagesEconomics Assianmentsultana nasirNo ratings yet

- Public Finance Lecture Notes Gruber Chapter 2Document22 pagesPublic Finance Lecture Notes Gruber Chapter 2Hiram CortezNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 Notes Aggregate Expenditure ModelDocument14 pagesChapter 8 Notes Aggregate Expenditure ModelBeatriz CanchilaNo ratings yet

- Principles of Macro CourseworkDocument4 pagesPrinciples of Macro CourseworkgrfyfqsywvNo ratings yet

- MAACROECONOMICSDocument36 pagesMAACROECONOMICSSIEER LONE (RA2011033010151)No ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Macroeconomics Principles Applications and Tools 8 e 8th Edition Arthur Osullivan Steven Sheffrin Stephen PerezDocument16 pagesSolution Manual For Macroeconomics Principles Applications and Tools 8 e 8th Edition Arthur Osullivan Steven Sheffrin Stephen PerezVanessaMerrittdqes100% (38)

- Macroeconomics Canadian 5th Edition Williamson Solutions ManualDocument35 pagesMacroeconomics Canadian 5th Edition Williamson Solutions Manualsinapateprear4k100% (21)

- Consumption Function and MultiplierDocument24 pagesConsumption Function and MultiplierVikku AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Government Spending - Is The Sum ofDocument3 pagesGovernment Spending - Is The Sum ofBenedectine SalongaNo ratings yet

- Consumption and SavingDocument21 pagesConsumption and SavingShannon MojicaNo ratings yet

- GDP Expenditures EquationDocument24 pagesGDP Expenditures EquationlocketblaqNo ratings yet

- Ans. To. The. Q. No. 1 (A)Document4 pagesAns. To. The. Q. No. 1 (A)sultana nasirNo ratings yet

- Consumption FunctionDocument31 pagesConsumption FunctionDeepak MittalNo ratings yet

- Module 1Document4 pagesModule 1Annabelle MancoNo ratings yet

- LECTURE 3 Equilibrium Im Product MarketDocument50 pagesLECTURE 3 Equilibrium Im Product MarketNeha SinghNo ratings yet

- Session 1Document3 pagesSession 1Abhinav SahrmaNo ratings yet

- Eco, ch-26 Consumption and SavingDocument7 pagesEco, ch-26 Consumption and Savingaminaabdulaziz2005No ratings yet

- Consumption Is An Increasing Function of IncomeDocument18 pagesConsumption Is An Increasing Function of IncomeRajesh Lamba100% (1)

- KWe3 Macro Ch6SelectedDocument26 pagesKWe3 Macro Ch6SelectedMichael DCNo ratings yet

- Eco Imp Sem-2Document15 pagesEco Imp Sem-2saharshreddyNo ratings yet

- Basic of BudgetDocument6 pagesBasic of Budgetahmedabad management association AhmedabadNo ratings yet

- Unit IDocument27 pagesUnit Iarnav.mi2006No ratings yet

- Intro To MacroeconDocument31 pagesIntro To MacroeconYrence OliveNo ratings yet

- Keynes LawDocument7 pagesKeynes LawNaresh KumawatNo ratings yet

- Theory of ConsumptionDocument61 pagesTheory of Consumptionpalakagrawal2216No ratings yet

- Eco Dev MidtermDocument6 pagesEco Dev MidtermGlenn VeluzNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 Topics 1,2 and 3Document143 pagesUnit 4 Topics 1,2 and 3Nicholas ThamNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics III: Consumption and Investment: Gavin Cameron Lady Margaret HallDocument21 pagesMacroeconomics III: Consumption and Investment: Gavin Cameron Lady Margaret HallIrina StefanaNo ratings yet

- Efficient Ways to Maintain Your Finances: Budgeting, Retirement Plan, Passive Income & Personal FinanceFrom EverandEfficient Ways to Maintain Your Finances: Budgeting, Retirement Plan, Passive Income & Personal FinanceNo ratings yet

- Abm161 Lessons 10 11 2023Document48 pagesAbm161 Lessons 10 11 2023Norhaliza D. SaripNo ratings yet

- Agrarian Reform After Lesson 67Document24 pagesAgrarian Reform After Lesson 67Norhaliza D. SaripNo ratings yet

- Abm161 Lesson 1. Overview of Macroeconomics 2022Document55 pagesAbm161 Lesson 1. Overview of Macroeconomics 2022Norhaliza D. SaripNo ratings yet

- The Agribusiness Group1 2Document33 pagesThe Agribusiness Group1 2Norhaliza D. SaripNo ratings yet

- Group 2 ABM83Document18 pagesGroup 2 ABM83Norhaliza D. SaripNo ratings yet

- Lesson 14 ABM161 Taxation For FinalsDocument41 pagesLesson 14 ABM161 Taxation For FinalsNorhaliza D. SaripNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics Syllabus 2Document3 pagesMacroeconomics Syllabus 2chhetribharat08No ratings yet

- Composite Indexes and Diffusion Indexe1Document7 pagesComposite Indexes and Diffusion Indexe1AaruniNo ratings yet

- Business Taxation MaterialDocument18 pagesBusiness Taxation MaterialKhushboo ParikhNo ratings yet

- British Economic Growth and The Business Cycle 1700-1850Document48 pagesBritish Economic Growth and The Business Cycle 1700-1850Sabrina CanţîrNo ratings yet

- Aggregate Demand & Supply of LabourDocument68 pagesAggregate Demand & Supply of Labourankit gogriNo ratings yet

- Sample Test hp4Document5 pagesSample Test hp4Thư MaiNo ratings yet

- StagflationDocument5 pagesStagflationKunal JainNo ratings yet

- Parle Working Capital AshishDocument72 pagesParle Working Capital Ashishkksomani21100% (1)

- MegaQuizFileECO401byShahzadSadiq PDFDocument273 pagesMegaQuizFileECO401byShahzadSadiq PDFFərruxXəmənNo ratings yet

- Fiscal Policy For Sustainable Development in Asia Pacific Lekha S Chakraborty Full ChapterDocument67 pagesFiscal Policy For Sustainable Development in Asia Pacific Lekha S Chakraborty Full Chapterhelen.hamler923100% (15)

- Making Money For Business: Currencies, Profit, and Long-Term Thinking by B. Lietaer and G. HallsmithDocument6 pagesMaking Money For Business: Currencies, Profit, and Long-Term Thinking by B. Lietaer and G. Hallsmithuser909No ratings yet

- (Globalization, Crises, and Change) Berch Berberoglu - Beyond The Global Capitalist Crisis - The World Economy in Transition (2011, Ashgate) PDFDocument218 pages(Globalization, Crises, and Change) Berch Berberoglu - Beyond The Global Capitalist Crisis - The World Economy in Transition (2011, Ashgate) PDFwalter blanquiNo ratings yet

- BBM Sylabus PDFDocument35 pagesBBM Sylabus PDFAjay DhawalNo ratings yet

- Economic Boom and Effects. Some Solutions of The UK GovernmentDocument4 pagesEconomic Boom and Effects. Some Solutions of The UK Governmenttuan sonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 IntroDocument14 pagesChapter 1 IntroliyayudiNo ratings yet

- The Long Waves of Economic Life - KondratievDocument80 pagesThe Long Waves of Economic Life - KondratievIlias FilisNo ratings yet

- Aggregate Demand & Supplu ModelDocument20 pagesAggregate Demand & Supplu ModelShajeer HamNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Business Cycle-1Document6 pagesCase Study On Business Cycle-1ASAD ULLAHNo ratings yet

- Bab 1 Pengantar Bisnis Buku GriffinDocument47 pagesBab 1 Pengantar Bisnis Buku GriffinSiti Auli Yanti NurbachNo ratings yet

- Company AnalysisDocument84 pagesCompany AnalysisShantnu SoodNo ratings yet

- Pool of Questions of Economix Quizbee 2013Document17 pagesPool of Questions of Economix Quizbee 2013John Vincent Pardilla100% (1)

- Treasury Management: Module 1 Chapter 3: Cash ForecastingDocument40 pagesTreasury Management: Module 1 Chapter 3: Cash ForecastingAUMBRIELL GOMEZNo ratings yet

- Commodity Price VolatilityDocument36 pagesCommodity Price VolatilityhertinaNo ratings yet

- Economics Project New 2Document53 pagesEconomics Project New 2humphreyoluoch97No ratings yet

- AD AS QuestionsDocument15 pagesAD AS QuestionsRizka SyarifNo ratings yet

- Economic Principles 201819Document27 pagesEconomic Principles 201819Fortunatus JuliusNo ratings yet

- Chapter One Economic Thought Before Adam SmithDocument130 pagesChapter One Economic Thought Before Adam SmithbopgalebelayNo ratings yet

- Final KEC ReportDocument116 pagesFinal KEC Reports2410100% (4)

- Intevju Robert Aliber PDFDocument4 pagesIntevju Robert Aliber PDFalpar7377No ratings yet