Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Laverda Combine Harvester m132 Parts Catalog FR

Laverda Combine Harvester m132 Parts Catalog FR

Uploaded by

dominiqueayaladds060597gewOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Laverda Combine Harvester m132 Parts Catalog FR

Laverda Combine Harvester m132 Parts Catalog FR

Uploaded by

dominiqueayaladds060597gewCopyright:

Available Formats

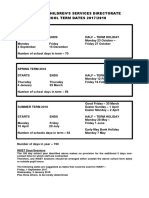

Laverda Combine Harvester M132 Parts Catalog_Fr

Laverda Combine Harvester M132

Parts Catalog_Fr

To download the complete and correct content, please visit:

https://manualpost.com/download/laverda-combine-harvester-m132-parts-catalog_

fr/

** Laverda Combine Harvester M132 Parts Catalog_Fr** Size: 149 MB Format :

PDF Language : French Brand: Laverda Type of machine: Combine Harvester

Type of document: Parts Catalog Model: Laverda M132 Combine Harvester

Number of Pages: 362 pages

Download all on: manualpost.com.

Visit ManualPost.com to get correct and complete item

[Unrelated content]

Another random document on

Internet:

had been to the board of guardians, or to the clerk of the Stafford union, and

promised to behave better in future. Has had various similar cases brought before

him.'"

The following statements of the Commissioners demand

serious consideration.—(Second Report, p. 105.)

"581. But the chief disease is that produced by the occupation of the grinder,

which is the most pernicious of any branch of manufacture in England. The

inhalation of the dust of the grindstone and of the steel of the knife, or whatever

he may be grinding, is so pernicious, that the life of a dry grinder scarcely

averages thirty-five years, whilst that of a wet grinder is seldom prolonged to more

than forty-five years. The bent posture and pressure on the stomach aggravate

the evil. Fork-grinding is the most pernicious, because it is done dry, and a great

deal more of the steel has to be ground off. Dr. Knight states that he cannot better

express how injurious grinding is to the health than by stating, that 'they who are

the greatest drinkers among the grinders are sometimes the longest lived, owing

to their more frequent absence from their work.'

"582. Dust flues, in the state of perfection to which they have now been

brought, appear to be capable of greatly diminishing if not of entirely obviating the

evil. The Sheffield grinders cannot, however, be induced to avail themselves of this

security; they know that they are doomed to an early death, yet they are

absolutely unwilling that the evil to which they are exposed should in any degree

be lessened: they regard every precaution to prolong life with jealousy, as a

means of increasing the supply of labor and lowering wages; they are for 'a short

life and a merry one,' and hence, even when the masters are at the expense of

erecting the apparatus, these men refuse to use it, and even frequently kick it

down and break it under their feet.'"—(Ibid. Evidence.)

As to the moral state of this class of work-people, the

Report speaks thus.—(Second Report, p. 176-178.)

"933. The moral and religious state of the children and young persons employed

in the trades and manufactures of Birmingham, is described by the Sub-

commissioner as very unfavorable. The social and domestic duties and affections

are but little cultivated and practiced; great numbers never attend any place of

religious worship; and of the state of juvenile crime some conception may be

formed from the statement, that of the total number of known or suspected

offenders in this town, during the last twelve months, namely 1223, at least one-

half were under fifteen years of age.

"934. As to illicit sexual intercourse, it seems to prevail almost universally, and

from a very early period of life: to this conclusion witnesses of every rank give

testimony.

"936. Wolverhampton.—Of the moral condition of the youthful population in the

Wolverhampton district, Mr. Horne says—'Putting together all I elicited from

various witnesses and conversations with working people, abroad and at home,

and all that fell under my observation, I am obliged to come to the conclusion,

that the moral virtues of the great majority of the children are as few in number

and as feeble in practice as can well be conceived of those who are born in a

civilized country, surrounded by religious and educational institutions, and by

individuals anxious for the improvement of the condition of the working classes.'

He adds of Willenhall—'A lower condition of morals, in the fullest sense of the

term, could not, I think, be found. I do not mean by this that there are many more

prominent vices among them, but that moral feelings and sentiments do not exist

among them. They have no morals.'

"940. Sheffield.—In all the Sheffield trades employing large numbers of children,

it is stated that there is a much closer intermixture of the younger children with

the elder youths, and with the men, than is usual in the cotton, woollen, and flax

factories; and that the conversations to which the children are compelled to listen,

would debase their minds and blunt their moral feelings even if they had been

carefully and virtuously educated, but that of course this result takes place more

rapidly and completely in the case of those who have had little or no religious

culture, and little but bad example before their eyes from their cradle upwards.

"943. Habits of drinking are formed at a very early age, malt liquor being

generally introduced into the workshops, of which the youngest children are

encouraged to partake. 'Very many,' say the police officers, 'frequent beer-shops,

where they play at dominoes, bagatelle, &c., for money or drink.' Early

intemperance is assigned by the medical men as one cause of the great mortality

of Sheffield. 'There are beer-houses,' says the Rev. Mr. Farish, 'attended by youths

exclusively, for the men will not have them in the same houses with themselves.

In these beer-houses the youth of both sexes are encouraged to meet, and scenes

destructive of every vestige of virtue or morality ensue.'

"945. But it is stated by all classes of witnesses, that 'the most revolting feature

of juvenile depravity in this town is early contamination from the association of the

sexes;' that 'juvenile prostitution is exceedingly common.' 'The evidence,' says the

Sub-commissioner, 'might have been doubled which attests the early

commencement of sexual and promiscuous intercourse among boys and girls.'

"953. Sedgley.—At Sedgley and the neighboring villages, the number of girls

employed in nail-making considerably exceeds that of the boys. Of these girls Mr.

Horne reports—'Their appearance, manners, habits, and moral natures, (so far as

the word moral can be applied to them,) are in accordance with their half-civilized

condition. Constantly associating with ignorant and depraved adults and young

persons of the opposite sex, they naturally fall into all their ways; and drink,

smoke, swear, throw off all restraint in word and act, and become as bad as a

man. The heat of the forge and the hardness of the work render few clothes

needful in winter; and in summer, the six or seven individuals who are crowded

into these little dens find the heat almost suffocating. The men and boys are

usually naked, except a pair of trousers and an open shirt, though very often they

have no shirt; and the women and girls have only a thin, ragged petticoat, and an

open shirt without sleeves.'"

Lace-Making.—In this occupation it is proved, by

unquestionable evidence, that it is customary for children to

begin to work at the age of four, five, and six years; and

instances were found in which a child only two years old was

set to work by the side of its mother. The work is of course

very slight, but is trying to the eyes. The Sub-commissioner,

after detailing a case, says

"58. In this case, if the statement of the mother be correct, one of her children,

four years of age, works twelve hours a-day with only an interval of a quarter of

an hour for each meal, at breakfast, dinner, and tea, and never going out to play:

and two more of her children, one six and the other eight years of age, work in

summer from 6 a. m. till dusk, and in winter from seven in the morning till ten at

night, fifteen hours.

"59. This family is singular only in the children being set to work at the ages of

two or three. It is common in this district for children to commence work at four,

five, and six; the evidence renders this fact indubitable."—(Second Report, p. 10.)

The following extracts relate to the hours of work in the

lace trade:—

"336. In the Nottingham, Leicester, and Derby districts, partly from the causes

just assigned, and partly from the dissipated habits of the workmen, 'the hours of

labor are so extremely irregular that it is impossible to speak of them with exact

precision.' The hand-machines, especially the wide machines, are usually double-

handed; some very large ones have three men each; the men work such machines

by 'spells for shifts.' The most common time is sixteen, eighteen, and occasionally

twenty hours. 'However long,' adds the Sub-commissioner, 'may be the hours

during which the machines are propelled, even for the whole twenty-four, either by

hand or power, there are scarcely ever two complete sets of threaders.'

"341. Mr. William Hinde, aged twenty-nine, operative—'Among the small

masters, who have each one or two machines, it is the custom for one set of

children to work for two or three masters. The masters often live a long way from

each other; children have often to go one or two miles. They are always wanted

when the machine comes off, whatever may be the hour of the day or night; they

are required just as much by night as by day, unless the men will accommodate

the children, which is very rarely done, especially when trade is good. When there

has been a good pattern, and the machine in constant use, the children "have

scarcely a bit of peace," they have no regular time for meals, "no time for

nothing;" when one machine is off, another is on. Was himself formerly a threader,

and then a winder. Has often gone at six in the morning, and has had no time to

get any thing to eat, except a mouthful now and then, till three or four in the

afternoon. It is the same now, when trade is good. The children have no regular

time for meals; they have their food sent to them, and they eat when they can;

some have nothing but a bit of bread. There is no more regular time for sleeping

than for eating; the children often lie down "in the middle of the shop door, when

it is warm." Thinks hundreds have been sent to the grave by this work. It is

enough to kill the children, going half fed and clothed to work in the night, at this

time of the year. (The thermometer last night was 102.')—(Second Report, pp. 56-

9).

Of course, work of this nature, for such hours, and at such

an early age, cannot but be followed by deplorable

consequences to health in after life, as well as to moral

character. Accordingly the Commissioners report.—(II, p. 109,

110, 181.)

"598. From the nature of their occupation, the long and irregular hours of work,

the frequency of night-work, and the insufficient time allowed for meals—an evil of

the greatest magnitude in the case of growing children—the constitution is

frequently seriously impaired. 'The majority of the children whom I saw,' says the

Sub-commissioner, 'were pale and unhealthy-looking, and several were of

diminutive stature. The health and sight are often greatly impaired, especially

among the runners, who occasionally faint while at work; indeed, there cannot be

an occupation which more seriously deteriorates the constitution. Short-

sightedness, amaurosis, distortion of the spine, excessive constitutional debility,

indigestion, and derangement of the uterine functions, may be said to be almost

universal: all the evidence points to this conclusion.'

"'In the town of Nottingham,' says Mr. Grainger, 'all parties, clergy, police,

manufacturers, work-people, and parents, agree that the present mode of

employing children and young persons as threaders and winders is a most fertile

source of immorality. There can, in fact, be but few states more immediately

leading to vice and profligacy. Children of both sexes are called out of their

parents' houses at all hours of the night, and, as it is quite uncertain how long

they may be required, whether for two hours or the whole night, a ready and

unanswerable excuse for staying out is furnished.—(No. 138.)

"The moral condition of the lace-makers in Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire, Beds

and Bucks, is stated by Major Burns to be extremely low, and prostitution is rife

among them, from their scanty earnings, their love of finery, and the almost total

absence of early moral culture."—(Report: App. Pt. I, p. A. 12, s. 104.)

Millinery and Dressmaking.—The portion of these

instructive volumes which describes the condition of the

young women employed as milliners and mantua-makers in

our great cities, and especially in London, is, however, that

which has left the most painful impression upon our minds—

not only because the work of these unfortunate girls is of all

the most, severe and unremitting—nor because it is inflicted

exclusively upon the weaker sex, and at a period of life the

most susceptible of injury from overstrained exertion—nor yet

because the actual consequences which are shown to ensue

in thousands of cases are so peculiarly deplorable—-but

because the excess of labor (with all its pernicious and fatal

results) is endured in the service, and inflicted in execution of

the orders, of a class whose own exemption from toil and

privation should make them scrupulously careful not to

increase, causelessly or selfishly, the toils and privations of

their less favored fellow-creatures—a class, too, many of

whom have been conspicuously loud in denouncing the

cruelties of far more venial offenders, and in expressing a

somewhat clamorous and overacted sympathy with sufferings

which cannot for a moment be compared in severity with

those which are every day inflicted on the helpless of their

own sex, in ministering to their own factitious and capricious

wants. The remark may appear harsh, but the evidence

before us fully warrants it—that probably in no occupation

whatever—not in the printing fields of Lancashire—not, in the

lace trade of Nottingham—not in the collieries of Scotland—

scarcely in the workshops of Willenhall—most assuredly not in

the cotton factories of Manchester, (which a few years ago

the fashionable fair of London were so pathetic in lamenting)

—can any instances of cruelty be met with which do not

"whiten in the shade" of those which every spring and

autumn season sees practiced—unreprobated, and till now

nearly unknown—in the millinery establishments of the

metropolis.

The following extracts will show that we are guilty of no

exaggeration.—(II, p. 114-122.)

"622. It is estimated that there are in London, in the millinery and dressmaking

business, at least 1500 employers, and that the number of young people engaged

by each employer varies from two or three to twenty-five or thirty-five—the

average in each establishment being about ten, making in the whole 15,000; but

this does not include journeywomen who work at their own houses, of whom also

there are great numbers.

"623. In some of what are considered the best regulated establishments, during

the fashionable season, occupying about four months in the year, the regular

hours of work are fifteen, but on emergencies, which frequently recur, these hours

extend to eighteen. In many establishments the hours of work, during the season,

are unlimited, the young women never getting more than six, often not more than

four, sometimes only three, and occasionally not more than two hours for rest and

sleep out of the twenty-four; and very frequently they work all night.

"625. Miss O'Neil, Welbeck street, an employer, says—'In the spring season the

hours of work are unlimited. The common hours are from six a. m. till twelve at

night—sometimes from four a. m. till twelve. Has herself often worked from six a.

m. till twelve at night for two or three months together. It is not at all uncommon,

especially in the dressmaking, to work all night; just in the 'drive of the season,'

the work is occasionally continued all night three times a-week. Has worked

herself twice in the week all night. In some houses which profess to study the

health of their young people, they begin at four a. m. and leave off at eleven p.

m., never earlier. Has heard there are houses in London which work on Sundays.

"628. Miss —— ——, manager—'has been ten years a "first hand," which

signifies the party who takes the superintendence of the business, as overlooker of

the young persons, cutter-out of the work, &c. The common hours of business are

from eight a. m. till eleven p. m. in the winter; in the summer from six or half-past

six a. m. till twelve at night. During the fashionable season, that is from April to

the end of July, it frequently happens that the ordinary hours are greatly

exceeded: if there is a drawing-room, or grand fête, or mourning to be made, it

often happens that the work goes on for twenty hours out of the twenty-four,

occasionally all night. Every season in at least half the houses of business, it

happens that the young persons occasionally work twenty hours out of the

twenty-four, twice or thrice a-week. On special occasions, such as drawing-rooms,

general mournings, and very frequently wedding orders, it is not uncommon to

work all night; has herself worked twenty hours out of the twenty-four for three

months together; at that time she was suffering from illness, and the medical

attendant remonstrated against the treatment she received. He wished witness to

remain in bed at least one day longer, which the employer objected to, required

her to get up, and dismissed the surgeon. It frequently happened that the work

was carried on till seven o'clock on Sunday morning. If any particular order was to

be executed, as mournings or weddings, and they left off on Saturday night at

eleven, they worked the whole of Sunday; thinks this happened fifteen times in

the two years. In consequence of working so late on Sunday morning, or all that

day occasionally, could very rarely go to church; indeed it could not be thought of,

because they generally rested in bed.'

"639. The correctness of these representations is confirmed, among others, by

the following medical witnesses:—Sir James Clark, Bart., Physician to the Queen

—'I have found the mode of life of these poor girls such as no constitution could

long bear. Worked from six in the morning till twelve at night, with the exception

of the short intervals allowed for their meals, in close rooms, and passing the few

hours allowed for rest in still more close and crowded apartments—a mode of life

more completely calculated to destroy human health could scarcely be contrived,

and this at a period of life when exercise in the open air, and a due proportion of

rest, are essential to the development of the system. Judging from what I have

observed and heard, I scarcely believed that the system adopted in our worst-

regulated manufactories can be so destructive of health as the life of the young

dressmaker.'

"647. 'The protracted labor described above,' says the Sub-commissioner, 'is, I

believe, quite unparalleled in the history of manufacturing processes. I have

looked over a considerable portion of the Report of the Factory Commission, and

there is nothing in the accounts of the worst-conducted factories to be compared

with the facts elicited in the present enquiry. Gentlemen who, from their official

situation, were well qualified to judge, have also stated, in answer to my

questions, that they knew of no instance in which the hours of work were so long

as those above stated.'

"663. Of the general treatment and condition of these young people, the Sub-

commissioner reports:—'The evidence of all parties establishes the fact that there

is no class of persons in this country, living by their labor, whose happiness,

health, and lives, are so unscrupulously sacrificed as those of the young

dressmakers. It may without exaggeration be stated, that, in proportion to the

numbers employed, there are no occupations, with one or two questionable

exceptions, such as needle-grinding, in which so much disease is produced as in

dressmaking, or which present so fearful a catalogue of distressing and frequently

fatal maladies. It is a serious aggravation of all this evil, that the unkindness of the

employer very frequently causes these young persons, when they become unwell,

to conceal their illness from the fear of being sent out of the house; and in this

manner, the disease often becomes increased in severity, or is even rendered

incurable. Some of the principals are so cruel as to object to the young women

obtaining medical assistance.'"—(No. 626.)

FOOTNOTES:

[32] It is, however, but fair to state, that many competent and most

respectable observers declare, that though the facts stated by the

Commissioners may be perfectly true, yet that the tone and spirit of the

Report bears token of material exaggeration.

[33] The colliers in the east of Scotland, however, are excepted.

[34] It is curious to contrast this with a similar comparison instituted

by the Factory Commissioners, and embracing upwards of 1000 children.

—(Analysis of the Evidence taken before the Factory Commissioners, p.

9.)

Boys not in factories averaged 55.56 inches

Boys in factories, 55.28 "

——

Difference, .28! "

Girls not in factories, 54.979 "

Girls in factories, 54.951 "

———

Difference, .028!! "

CHAPTER XVIII.

THE LONDON GLOBE ON WEST INDIA

EMANCIPATION.

We find the following frank and explicit admission in the Globe of

10th July, 1856:

"Our own West India Islands are fast relapsing into

primitive savageness. When the rich lands of Jamaica are

being yearly abandoned, and when in Trinidad and Guiana

cultivation has almost ceased, it is not likely that England will

care to extend her sovereignty further over tropical territory,

which can only be brought into use by a system which has

been solemnly condemned."

Now, let us rigidly examine and ascertain what is the condemned

system, what the approved system, that has been generally adopted

in its stead, and why this system is approved, and the free negro

system condemned as a failure.

There is no doubt the writer alludes to the system of domestic

slavery, in the general, as the condemned system; and especially, to

that serfdom or villienage which lately prevailed, but is now

abolished throughout Western Europe. In asserting that the system

of slavery has been condemned, and yet admitting West India

emancipation to be a failure, he in effect maintains that the

liberation of the villiens has been no failure. He means that it has

been no failure, because the liberated villiens do work: aye, just

twice as hard and as long as their ancestors, the serfs. He means it

is no failure, because they not only work harder and longer, but work

for half the pay or allowance of their servile ancestors. He means it

is no failure, because the once masters, now employers, get their

labor for half what it cost to support them as slaves. He means it is

no failure, because free labor in England is more plentiful and far

cheaper than slave labor in America. He means it is no failure,

because the employers, besides getting cheaper and more abundant

labor, are relieved of all the cares and anxieties of governing and

providing for their laborers, in health and in sickness, in old age and

in infancy. In fine, he means it is no failure, because the laborers of

England are not half so free now as before their pretended

emancipation. They have lost all their rights, half their liberty (for

they work harder than before,) and their former masters have been

relieved of all their legal obligations and responsibilities. No—British

emancipation has not failed, if we look solely to the selfish interests

of the property class. And British liberty, we shall show in another

chapter, means the unlimited right of the property class to oppress

the laboring class, uncoupled with the obligation to provide for them.

But this writer well knew, that looking to the effect of emancipation

on the condition of the laboring class in England, it has been a cruel

and monstrous failure, from first to last. They are almost as savage

and ignorant as West India negroes, know nothing of the Bible, and

live in a state of continued destitution, hunger, and excessive labor,

from generation to generation—from infancy to old age.

West India emancipation was a blunder of swindling philanthropy.

People were told that the negroes, after emancipation, would work

harder, work for less, and be more of slaves than before, just as had

happened with emancipated English. But philanthropy "hath bad

luck." It overlooked, or forgot, the few wants and indolent habits of

the negro, the abundance of mountain lands, the fertile soil, the

volunteer fruits and mild climate of Jamaica. The negro is really free,

and luxuriates in sloth, ignorance and liberty, as none but a negro

can. The mistake and the failure consisted in setting him really free,

instead of nominally so. Hinc illæ lachrymæ!

What vile hypocrisy to shed crocodile tears over the happy negro,

and boast of British Liberty, which is daily and hourly consuming, by

poverty, and cold, and foul air and water, and downright starvation,

the lives of ten millions of your white brethren and neighbors!

But this system, which carried to untimely graves three hundred

thousand Irishmen in a single season, has not been condemned. No;

it is profitable to the oppressors, and will not be condemned.

In all countries where a few own the property and the population

is tolerably dense, laborers relieved from domestic slavery are

remitted to the exploitation of skill and capital, which renders them

less free and worse situated in all respects after emancipation than

before. To prove this great truth, is the chief object of our present

work. We know that the philosophy of the subject is intricate and

complex, and that we have the prejudices, fanaticism and

prepossessions of a world to oppose and conquer. We therefore

indulge in frequent iteration, and adduce numerous proofs, examples

and illustrations.

CHAPTER XIX.

PROTECTION, AND CHARITY, TO THE WEAK.

A mere verbal formula often distinguishes a truism from a

paradox. "It is the duty of society to protect the weak;" but

protection cannot be efficient without the power of control;

therefore, "It is the duty of society to enslave the weak." And it is a

duty which no organized and civilized society ever failed to perform.

Parents, husbands, guardians, teachers, committees, &c., are but

masters under another name, whose duty it is to protect the weak,

and whose right it is to control them. The blacks in America are both

positively and relatively weak. Positively so, because they are too

improvident to lay up for the exigencies of sickness, of the seasons,

or of old age. Relatively so, because they are wholly unequal to the

whites among whom they live, in the war of the wits and free

competition, which universal liberty begets, and political economy

encourages.

In old countries the white laborers are relatively weak, because all

property is closely appropriated, and the capitalist class possess the

means of unlimited oppression. Everybody admits that in such

countries the poor need protection. But there can be no efficient

protection without enslavement of some sort. In England, it has

often been remarked, that all the legislation for the poor is borrowed

from the system of domestic slavery.

Public and private charity is a fund created by the labor of the

industrious poor, and too often bestowed on the idle or improvident.

It is apt to aggravate the evils which it intends to cure.

Those who give should have the power to control, to some extent,

the conduct and expenditure of the objects of their charity. Not till

then can they be sure that their gifts will be promotive of good. But

such power of control would be slavery.

Can abolitionists solve these social problems?

Ambition has ever been considered the most noble of human

failings. It is, however, no failing, or crime, at all. Ambition desires

power, and without power there can be no safe, prudent and active

benevolence. The selfish, the indolent, and the timid, are without

ambition, and eschew power, because of the trouble, the expenses,

and the responsibilities which it imposes. The actively good are

always ambitious, and desire to possess power, in order that they

may control, in some measure, the conduct of those whom they

desire to benefit.

The best thing a philanthropist can do, is to buy slaves, because

then his power of control is greatest—his ability to do practical good,

most perfect.

We take this occasion to correct an error into which we had fallen

as to Northern character. Benevolence, affection, generosity, and

philanthropy, are equally common North and South; and only differ

in their modes of manifestation. We are one people.

The daily and hourly exercise of these qualities is elicited at the

South, because it is safe, prudent and expedient so to exercise

them. The reverse is true at the North: yet, "expel Nature and she

will return again." Man is social and philanthropic, and his affections,

dammed out in one direction, find vent and gush out in another. The

people of the North are far more generous and munificent in the

endowment of public charities, and other public institutions, than

we. This correction of our error does not affect our theories—if it be

true, that you can only safely be charitable to dependents whom you

can control. But if it did or does affect, neutralize and subvert them,

it is due to truth,—and if we advance the cause of truth, we are

ready for the sacrifice of all else.

"Our Trip to the North" excited doubts as to our estimate of

Northern character; and subsequent observation, reading and

reflection, have brought us to the conclusion, which we now with

pleasure avow. We would rather be right than consistent.

CHAPTER XX.

THE FAMILY.

All modern philosophy converges to a single point—the overthrow

of all government, the substitution of the untrammelled "Sovereignty

of the Individual," for the Sovereignty of Society, and the

inauguration of anarchy. First domestic slavery, next religious

institutions, then separate property, then political government, and,

finally, family government and family relations, are to be swept

away. This is the distinctly avowed programme of all able

abolitionists and socialists: and towards this end the doctrines and

the practices of the weakest and most timid among them tend.

Proudhon, and the French socialists generally, avow this purpose in

France, and Stephen Pearl Andrews re-echoes it from America. The

more numerous and timid class are represented by Mr. Greeley and

the Tribune, who would not "at once rush," like French

revolutionists, "with the explosive force of escapement, point blank

to the bull's eye of its final destiny," but would inaugurate social

conditions, that would gradually bring about that result. Mr. Greeley

does not propose to do away at once with marriage, religion, private

property, political government and parental authority, but adopts the

philosophy and the practices of Fourier, which promise gradually to

purify human nature, and fit it, in a few generations, for that social

millenium, into which the bolder and more consistent Andrews urges

society at once to plunge.

The Christian socialists are beautifully and energetically co-

laborating with the infidel socialists and abolitionists to bring about

this millenium. They also are divided into two parties. The one would

wait upon Providence—only help it a little, like Mr. Greeley—and

permit our poor old effete world to pass out of existence by gentle

euthanasia. The other and bolder party, feel themselves "called" as

special instruments, to give at once the coup de grace to the old

world, and to usher in the new golden age, of free love and free

lands, of free women and free negroes, of free children and free

men.

We like the Northern socialist theoretical abolitionists—read their

speeches, essays, lectures and books, because they agree with us,

that their own form of society is a humbug and a failure; and in their

efforts, speculations and schemes to re-organize it, afford the most

beautiful, perfect and complete specimen of the reductio ad

absurdum. A lecture from Mr. Andrews on No-government, an

Oneida den of incest, a Greeley phalanstery, or a New York free love

saloon, afford equally good instances of this mode of demonstration

by the absurdities which they exhibit, and equally good proofs of the

naturalness and necessity of slavery, since such horrid abuses are

everywhere the approved and practiced outgrowth of free society. As

all our thoughts, arguments, proofs and demonstrations are

suggested by or borrowed from the abolitionists, it seems to us we

ought to dedicate to them. The Tribune very properly remarked that

our Sociology was the first attempt of the kind at the South. It

ridiculed our ignorance, too, severely. It should have recollected that

were there no sickness there would be no physicians. We assure the

Tribune, we are quite a prodigy in these matters for a Southern man.

We have no social diseases, and therefore no social doctors to write

about them or cure them. Such diseases have been rare: for

Aristotle complains that there are no terms to express the relations

of husband and wife, or parent and child. These relations have

worked so smoothly in slave society to this day, that we in writing

have felt the same want of language of which Aristotle, more than

two thousand years ago, complained. You should invent such terms

at the North, if it be true, as Mr. Andrews states in italics, that there

are ten fugitives from Northern matrimony to one from Southern

slavery—from which he seems to infer very logically, that the

necessity of abolishing the family at the North, is ten times as great

as that for abolishing slavery at the South. He and you are experts,

and we know it is presumptuous in us to dispute what you say about

your own society. Still we are dead against your phalansteries and

his love saloons. Gentlemen and scholars, generally at the South,

would as soon be caught studying or practicing the black art, as in

reading Owen or Fourier, or in building phalansteries. For ourselves,

like the Bastard in King John, we learn these things, "not to deceive,

but to avoid deceit." We have whole files of infidel and abolition

papers, like the Tribune, the Liberator and Investigator. Fanny

Wright, the Devil's Pulpit and the Devil's Parson, Tom Paine, Owen,

Voltaire, et id genus omne, are our daily companions. Good people

give our office a wide berth as they pass it, and even the hens who

loiter about it, have caught the infection of Woman's Rights, for we

saw but as few days ago a Shanghai cock under its eaves hovering a

brood of twenty chickens, whilst madam hen was strutting about in

as large a liberty as any Bloomer or wise woman of the North.

Love and veneration for the family is with us not only a principle,

but probably a prejudice and a weakness. We were never two weeks

at a time from under the family roof, until we had passed middle life,

and now that our years almost number half a century, we have

never been from home for an interval of two months. And our

historical reading, as well as our habits of life, may have unfitted us

to appreciate the communist and fusion theories of Fanny Wright,

Owen and Mr. Greely. In attempting to vindicate and justify the ways

of God and Nature, against the progressiveness of Black

Republicanism in America, and Red Republicanism in Europe, we

would forewarn the reader that we are a prejudiced witness. We are

the enthusiastic admirer of the social relations exhibited in the

histories of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. The social relations

established in Deuteronomy, and 25th chapter Leviticus, and as

practiced by the Jews to this day, elicit our unfeigned admiration and

approval. Moses is with us the Prince of Legislators, and the twenty-

fifth Leviticus the best of political platforms. The purity of the family

seems to be his paramount object.

Homer, too, especially in his Odyssey, charms and enchains us

with his beautiful descriptions of family felicity and family purity. As

conquest and commerce introduced wealth and corrupted morals

and manners, the family was corrupted and disrupted, as it is now,

at the most commercial points in the North. But we have only to

pass over to Italy, and there, from the earliest days of tradition until

the extinction of liberty, began by Sylla and Marius, and ended by

Augustus, we find the family a pure, a holy and sacred thing. From

that era till slavery arose in the South, the family never resumed its

dignity and importance. Feudalism did something to correct the

loose morality of the Augustan Age, but it adopted its colonial

slavery, relaxed family ties, and never drew together in sufficiently

close connection and subordination, the materials which nature

dictates should form the human hive or social circle.

Aristotle understood this subject thoroughly; and it seems to have

been generally so well comprehended in his day, that he takes little

trouble to explain and expound it. He commences his treatise on

Politics and Economics with the family, and discourses first of the

slaves as a part of the family. He assumes that social life is as

natural to man as to bees and herds; and that the family, including

husband, wife, children, and slaves, is the first and most natural

development of that social nature. As States are composed of

families, and as a sound and healthy whole cannot be formed of

rotten parts, he devotes much of his treatise to family education and

government. Would that modern statesmen, philosophers and

politicians, would become practical like Aristotle, and not attempt to

build social and political edifices, until they were sure of the

soundness of the materials of which they would construct them. As

all human beings live for the greatest part of their lives in families, it

is all important that they should look to the wise arrangement of this

old and universal institution.

We wish to prove that the great movement in society, known

under various names, as Communism, Socialism, Abolitionism, Red

Republicanism and Black Republicanism, has one common object:

the breaking up of all law and government, and the inauguration of

anarchy, and that the destruction of the family is one of the means

in which they all concur to attain a common end. We shall quote

only from Stephen Pearle Andrews, because he is by far the ablest

and best informed of American Socialists and Reformers, and

because he cites facts and authorities to show that he presents truly

the current thought and the general intention. Mr. Andrews is a

Massachusetts gentleman, who has lived at the South. He has been

an Abolition Lecturer. He is the disciple of Warren, who is the disciple

of Owen of Lanark and New Harmony. Owen and Warren are

Socrates and Plato, and he is the Great Stygarite, as far surpassing

them, as Aristotle surpassed Socrates and Plato. But it is not merely

his theories on which we rely; he cites historical facts that show that

the tendency and terminus of all abolition is to the sovereignty of

the individual, the breaking up of families, and no-government. He

delivered a series of lectures to the elite of New York on this subject,

which met with approbation, and from which we shall quote. He

established, or aided to establish, Free Love Villages, and headed a

Free Love Saloon in the city of New York, patronized and approved

by the "Higher classes." He is indubitably the philosopher and true

exponent of Northern Abolitionism. With this assertion, which none

who read his Science of Society we think will deny, we proceed to

quote from his able and beautiful lectures, embodied in a publication

entitled "Science of Society." Our first quotation is from his first

lecture and the first chapter of his work:

Every age is a remarkable one, no doubt, for those who live

in it. When immobility reigns most in human affairs, there is

still enough of movement to fix the attention, and even to

excite the wonder of those who are immediately in proximity

with it. This natural bias in favor of the period with which we

have most to do, is by no means sufficient, however, to

account for the growing conviction, on all minds, that the

present epoch is a marked transition from an old to a new

order of things. The scattered rays of the gray dawn of the

new era date back, indeed, beyond the lifetime of the present

generation. The first streak of light that streamed through the

dense darkness of the old regime was the declaration by

Martin Luther of the right of private judgment in matters of

conscience. The next, which shed terror upon the old world,

as a new portent of impending revolutions, was the denial, by

Hampden, Sidney, Cromwell, and others, of the divine right of

kings, and the assertion of inherent political rights in the

people themselves. This was followed by the American

Declaration of Independence, the establishment of a powerful

Democratic Republic in the western world upon the basis of

that principle, followed by the French Revolution, the Reign of

Terror, the Re-action, and the apparent death in Europe of the

Democratic idea. Finally, in our day, comes the red glare of

French Socialism, at which the world is still gazing with

uncertainty whether it be some lurid and meteoric omen of

fearful events, or whether it be not the actual rising of the

Sun of Righteousness, with healing in His wings; for there are

those who profoundly and religiously believe that the solution

of the social problem will be the virtual descent of the New

Jerusalem—the installation of the Kingdom of Heaven upon

earth.

First in the religious, then in the political, and finally in the

social relations of men, new doctrines have thus been

broached, which are full of promise to the hopeful, and full of

You might also like

- Lexus RC F 2015 10 Workshop Service ManualDocument22 pagesLexus RC F 2015 10 Workshop Service Manualdominiqueayaladds060597gew100% (136)

- Lexus Sc430 2010 Electrical Wiring DiagramDocument22 pagesLexus Sc430 2010 Electrical Wiring Diagramaprilleon221190omj100% (126)

- Liebherr Crawler Loader Lr622 Lr632 Service ManualDocument22 pagesLiebherr Crawler Loader Lr622 Lr632 Service Manualaprilleon221190omj100% (142)

- JCB Excavator Js130w Js150w r3 Sevice ManualDocument8 pagesJCB Excavator Js130w Js150w r3 Sevice Manualmrjustinmoore020389ocj99% (130)

- Lexus NX 300h Ayz1 Workshop Manual 2015 09Document22 pagesLexus NX 300h Ayz1 Workshop Manual 2015 09stevenwilson200189bgn100% (97)

- Lexus RC F 2015 10 Workshop Service ManualDocument22 pagesLexus RC F 2015 10 Workshop Service Manualdominiqueayaladds060597gew100% (136)

- Lexus Ls600hl 2008 Workshop ManualDocument22 pagesLexus Ls600hl 2008 Workshop Manualdominiqueayaladds060597gew100% (135)

- Landrover Ranger Rover 2018 Full Service Manual Wiring Diagram DVDDocument24 pagesLandrover Ranger Rover 2018 Full Service Manual Wiring Diagram DVDdominiqueayaladds060597gew99% (135)

- Asking The People For Their MoneyDocument13 pagesAsking The People For Their MoneyTCFNo ratings yet

- Laverda Combine Harvester l624 Parts CatalogDocument22 pagesLaverda Combine Harvester l624 Parts Catalogdominiqueayaladds060597gew100% (133)

- Lexus Ct200h 2015 2017 Electrical Wiring Diagram 2Document22 pagesLexus Ct200h 2015 2017 Electrical Wiring Diagram 2dominiqueayaladds060597gew100% (125)

- Laverda Combine Harvester 3400 R Parts CatalogDocument22 pagesLaverda Combine Harvester 3400 R Parts Catalogdominiqueayaladds060597gew100% (140)

- Laverda Combine Harvester 1740 Al Parts CatalogDocument22 pagesLaverda Combine Harvester 1740 Al Parts Catalogdominiqueayaladds060597gew100% (139)

- Lexus Rx350 2015 09 Usa Workshop Service ManualDocument22 pagesLexus Rx350 2015 09 Usa Workshop Service Manualdominiqueayaladds060597gew100% (136)

- Landini Tractor Blizzard 65 Parts Catalog 3540030m1Document22 pagesLandini Tractor Blizzard 65 Parts Catalog 3540030m1katrinaflowers160489rde100% (140)

- Liebherr Crawler Dozer Pr766 1681-05-4f g8!0!18190 Usa Can Operators Manual en PDFDocument22 pagesLiebherr Crawler Dozer Pr766 1681-05-4f g8!0!18190 Usa Can Operators Manual en PDFaprilleon221190omj100% (134)

- Liebherr Crane LTM 1090-4-1 Circuit Diagram Operating InstructionDocument22 pagesLiebherr Crane LTM 1090-4-1 Circuit Diagram Operating Instructionaprilleon221190omj100% (129)

- Yanmar Excavator Epc 11 2009Document22 pagesYanmar Excavator Epc 11 2009michaelgarza030201fwm100% (70)

- Linde Forklift 80s Spare Parts ListDocument23 pagesLinde Forklift 80s Spare Parts Listsusanphillips050591yon100% (133)

- Raymond Easi Reach Fork Lift Trucks Ez A DZ B Part Maintenance ManualDocument23 pagesRaymond Easi Reach Fork Lift Trucks Ez A DZ B Part Maintenance Manualscotthicks170301ped100% (132)

- Cummins Midrange Wiring Diagrams ManualDocument23 pagesCummins Midrange Wiring Diagrams Manualdebraolson080699ipq100% (142)

- Ford Mustang 2015-2-3 Litre Engine Wiring DiagramsDocument22 pagesFord Mustang 2015-2-3 Litre Engine Wiring Diagramskathleenflores140886xgk100% (133)

- Lexus Lx450d Lx570 2015 09 Workshop Service ManualDocument22 pagesLexus Lx450d Lx570 2015 09 Workshop Service Manualstevenwilson200189bgn100% (96)

- Baumann Service Training Documents GermanDocument22 pagesBaumann Service Training Documents Germankarenhaynes040882gzr100% (131)

- Still Electric Pallet Truck Egv S Egv S LB Spare Parts List deDocument22 pagesStill Electric Pallet Truck Egv S Egv S LB Spare Parts List demaryfisher141290dkz100% (133)

- Caterpillar Lift Truck Ep18cpnt Service ManualsDocument22 pagesCaterpillar Lift Truck Ep18cpnt Service Manualsjeffreysmith140886nqm100% (117)

- Daewoo Forklift d150 Electric Schematic Sb2128e00Document23 pagesDaewoo Forklift d150 Electric Schematic Sb2128e00franksutton010496xek100% (123)

- Caterpillar c12 Sebp4002 37 Marine Engine Parts ManualDocument22 pagesCaterpillar c12 Sebp4002 37 Marine Engine Parts Manualjasonwallace130196kte100% (125)

- Maserati 2009 Academy Training Manual enDocument22 pagesMaserati 2009 Academy Training Manual enshawnrice060387eqd100% (110)

- JCB Engines Perkins 400 Series 402d 403d 404d Spare Parts ManualDocument22 pagesJCB Engines Perkins 400 Series 402d 403d 404d Spare Parts Manualmrjustinmoore020389ocj100% (133)

- Lexus NX 200t 200 Agz1 Zgz1 Workshop Manual 2016 09Document22 pagesLexus NX 200t 200 Agz1 Zgz1 Workshop Manual 2016 09stevenwilson200189bgn100% (105)

- Link Belt Excavator 3900 Q Quantum Schematics Operation Shop ManualDocument22 pagesLink Belt Excavator 3900 Q Quantum Schematics Operation Shop Manualsusanphillips050591yon100% (138)

- Clark Forklift SPM 627a CSM 7-10-15 Service Parts ManualDocument8 pagesClark Forklift SPM 627a CSM 7-10-15 Service Parts Manualtraceylucas251087sjo100% (136)

- Cesab b860 b870 b885 Electric Forklift Repair ManualDocument22 pagesCesab b860 b870 b885 Electric Forklift Repair Manualjeffreysmith140886nqm99% (139)

- Gehl Articulated Loader Al20 DX Series I Operators Manual 908180aDocument22 pagesGehl Articulated Loader Al20 DX Series I Operators Manual 908180akathleenflores140886xgk100% (125)

- Komatsu Hydraulic Excavator Pc35r 8 45r 8 and Up Operator Maintenance Manual en Seam015304tDocument22 pagesKomatsu Hydraulic Excavator Pc35r 8 45r 8 and Up Operator Maintenance Manual en Seam015304twilliamkaufman010487ibp100% (135)

- Stihl Scs Mediacat 01 2012 UsaDocument22 pagesStihl Scs Mediacat 01 2012 Usapatrickjones181099wpo100% (141)

- Clark Forklift Osm 88 1 Cy 150 165 180 200 Maintenance ManualDocument16 pagesClark Forklift Osm 88 1 Cy 150 165 180 200 Maintenance Manualtraceylucas251087sjo100% (124)

- Bobcat Telescopic Handler t35120 Hydraulic Electrical SchematicDocument22 pagesBobcat Telescopic Handler t35120 Hydraulic Electrical Schematicjeremyduncan090185iqk100% (133)

- Toyota Forklift 4fb10 To 4fb15!30!4fb10 To 30 4fb15 Parts CatalogDocument22 pagesToyota Forklift 4fb10 To 4fb15!30!4fb10 To 30 4fb15 Parts Catalogtamimaldonado110395eno100% (66)

- Mitsubishi Forklift Fb18tca Service ManualDocument23 pagesMitsubishi Forklift Fb18tca Service Manualcatherinewade170701kty100% (124)

- Subaru Epc3 Europe General 09 2021 Spare Parts CatalogDocument23 pagesSubaru Epc3 Europe General 09 2021 Spare Parts Catalogchasewashington200487noi100% (125)

- Lexus Rc200t Rc350 2015 10 Workshop Service ManualDocument7 pagesLexus Rc200t Rc350 2015 10 Workshop Service Manualstevenwilson200189bgn100% (119)

- Komatsu Bulldozer D71ex 24 D71ex 24e0 d71px 24 d71px 24e0 Aug 2021 Sen06841 06 Shop ManualDocument22 pagesKomatsu Bulldozer D71ex 24 D71ex 24e0 d71px 24 d71px 24e0 Aug 2021 Sen06841 06 Shop Manualnathanielsmith070288fqb100% (129)

- Kobelco Hydraulic Excavator Sk200lc Vi Sk210lc Vi Sk210nlc Vi Service ManualDocument23 pagesKobelco Hydraulic Excavator Sk200lc Vi Sk210lc Vi Sk210nlc Vi Service Manualmaryolson060292tok100% (144)

- Bell b45d b50d Mk7 2 Articulated Dump Truck Parts Manual 872344Document22 pagesBell b45d b50d Mk7 2 Articulated Dump Truck Parts Manual 872344karenhaynes040882gzr99% (130)

- Mercedes Technical Training CdsDocument22 pagesMercedes Technical Training Cdsrobertsmith240302ngj100% (111)

- Terex Excavator Full Set Parts Catalog DVDDocument22 pagesTerex Excavator Full Set Parts Catalog DVDkennethmunoz261086fwb100% (134)

- Liebherr Wheeled Excavators A922 Rail Sv013 1190 94581 Operators Manuals 06 2020Document23 pagesLiebherr Wheeled Excavators A922 Rail Sv013 1190 94581 Operators Manuals 06 2020ryansullivan160591enk100% (109)

- Case Blue Ribbon Service Electrical Specifications Wiring Schematics Gss 1308 CDocument22 pagesCase Blue Ribbon Service Electrical Specifications Wiring Schematics Gss 1308 Cjasoncastillo060901jtd100% (138)

- Linde Pathfinder 3 5 8-4-01 2015 Developer Mode Tool Diagnostic Software DVDDocument22 pagesLinde Pathfinder 3 5 8-4-01 2015 Developer Mode Tool Diagnostic Software DVDryancharles140201dmk100% (116)

- Audi A3 (8V) 2013-2020 Wiring Digarams & Workshop Manuals - ENDocument23 pagesAudi A3 (8V) 2013-2020 Wiring Digarams & Workshop Manuals - ENdylanmiller080302nwa100% (68)

- Linde Service Guide LSG V 5 2 2-3-2017 EnglishDocument22 pagesLinde Service Guide LSG V 5 2 2-3-2017 Englishsusanphillips050591yon100% (140)

- Terex Demag Crawler Crane Cc2800 Technical TrainingDocument22 pagesTerex Demag Crawler Crane Cc2800 Technical Trainingkennethmunoz261086fwb100% (136)

- Clark Forklift Truck Spanish CTM Cem 10 20 Hpb1 Control Training ManualDocument22 pagesClark Forklift Truck Spanish CTM Cem 10 20 Hpb1 Control Training Manualjosecarlson060901gpq100% (134)

- Still Diesel LPG Forklift r70 16 r70 18 r70 20 Workshop Manual r70 7094 7099Document22 pagesStill Diesel LPG Forklift r70 16 r70 18 r70 20 Workshop Manual r70 7094 7099patrickjones181099wpo100% (127)

- Steyr Agricultural Tractor 6185 6200 6220 6240 CVT Maintenance Manual deDocument23 pagesSteyr Agricultural Tractor 6185 6200 6220 6240 CVT Maintenance Manual dejamesdeckerdds141290cpr100% (118)

- TCM Fb30 7 Fb30 7 Attachment Pa 81ua Parts CatalogueDocument22 pagesTCM Fb30 7 Fb30 7 Attachment Pa 81ua Parts Cataloguejohnpeterson250885gcw100% (63)

- Manitou Telehandler MLB 625 Turbo Confort Ex Series 1 E2 Repair Manual 547938en 05 2011Document22 pagesManitou Telehandler MLB 625 Turbo Confort Ex Series 1 E2 Repair Manual 547938en 05 2011rachaelgilmore201196tem100% (141)

- FS+Doc+1Document3 pagesFS+Doc+1aditya.sharm07No ratings yet

- A Treatise On Good Manners and Good Breeding Jonathan SwiftDocument6 pagesA Treatise On Good Manners and Good Breeding Jonathan SwiftTePuiaGPNo ratings yet

- Book 2 UtopiaDocument4 pagesBook 2 UtopiaNeculaes IonutNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Financial Management Moyer 13th Edition Test BankDocument34 pagesContemporary Financial Management Moyer 13th Edition Test Bankdogelesssixthly4i9j2g100% (38)

- Políticas Públicas No Brasil Uma Abordagem Institucional Gilmar Mendes Paulo Paiva Full Chapter Download PDFDocument57 pagesPolíticas Públicas No Brasil Uma Abordagem Institucional Gilmar Mendes Paulo Paiva Full Chapter Download PDFirshatrizzo3100% (3)

- Lexus Rx350 2015 09 Usa Workshop Service ManualDocument22 pagesLexus Rx350 2015 09 Usa Workshop Service Manualdominiqueayaladds060597gew100% (136)

- Lexus Ct200h 2015 2017 Electrical Wiring Diagram 2Document22 pagesLexus Ct200h 2015 2017 Electrical Wiring Diagram 2dominiqueayaladds060597gew100% (125)

- Laverda Combine Harvester 3400 R Parts CatalogDocument22 pagesLaverda Combine Harvester 3400 R Parts Catalogdominiqueayaladds060597gew100% (140)

- Laverda Combine Harvester l624 Parts CatalogDocument22 pagesLaverda Combine Harvester l624 Parts Catalogdominiqueayaladds060597gew100% (133)

- Laverda Combine Harvester 1740 Al Parts CatalogDocument22 pagesLaverda Combine Harvester 1740 Al Parts Catalogdominiqueayaladds060597gew100% (139)

- Landini Tractor Landpower 125 Parts Catalog 3688289m1Document22 pagesLandini Tractor Landpower 125 Parts Catalog 3688289m1dominiqueayaladds060597gew100% (135)

- Major Themes of A Farewell To ArmsDocument6 pagesMajor Themes of A Farewell To ArmsNoor Ul AinNo ratings yet

- List of Ministers/Minister of State / Adviser/Special Assistant To The Prime Minister Alongwith PortfoliosDocument3 pagesList of Ministers/Minister of State / Adviser/Special Assistant To The Prime Minister Alongwith PortfoliosTahir KhanNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics CaseDocument6 pagesLegal Ethics Case1925habeascorpusNo ratings yet

- Te, 'Wall 144 C I - T9.7R7U Ofcar: - Rrq7 Cilgpi - SDocument11 pagesTe, 'Wall 144 C I - T9.7R7U Ofcar: - Rrq7 Cilgpi - SNabilaNo ratings yet

- Chanrobles Law Lib Rary: RedDocument5 pagesChanrobles Law Lib Rary: Redmaanyag6685No ratings yet

- Office of The Ombudsman vs. Valencia, G.R.No. 183890, Apr. 13, 2011Document13 pagesOffice of The Ombudsman vs. Valencia, G.R.No. 183890, Apr. 13, 2011Yna Marei AguilarNo ratings yet

- Sr. No College Name District Gender Division ContactDocument3 pagesSr. No College Name District Gender Division ContactAli ArbabNo ratings yet

- Lukas 23 33-43Document2 pagesLukas 23 33-43MCTC LuponNo ratings yet

- 09 Chapter3 PDFDocument28 pages09 Chapter3 PDFShakshi MehtaNo ratings yet

- Relief of Shareholders & Creditors by Way of Class ActionDocument20 pagesRelief of Shareholders & Creditors by Way of Class ActionSaif AliNo ratings yet

- Cumbria County Council Term Dates 2017-2018Document1 pageCumbria County Council Term Dates 2017-2018Samuel Kings SchoolNo ratings yet

- Related Documents - CREW: Department of State: Regarding International Assistance Offers After Hurricane Katrina: Libya AssistanceDocument16 pagesRelated Documents - CREW: Department of State: Regarding International Assistance Offers After Hurricane Katrina: Libya AssistanceCREWNo ratings yet

- C.P.C Case Analysis Order 7 Rlue 11Document21 pagesC.P.C Case Analysis Order 7 Rlue 11Uday ReddyNo ratings yet

- Corruption PDFDocument219 pagesCorruption PDFmiligramNo ratings yet

- Hilton V. Guyot: Personae and Ratione MateriaeDocument9 pagesHilton V. Guyot: Personae and Ratione MateriaeConnieAllanaMacapagaoNo ratings yet

- Ahmed Yerima Style of WritingDocument3 pagesAhmed Yerima Style of WritingadedayodeborahjesugbemiNo ratings yet

- Matero FalconeDocument11 pagesMatero FalconeYeah Seen Bato BeruaNo ratings yet

- EWC Proposal Group 3 PDFDocument11 pagesEWC Proposal Group 3 PDFnur hadhirahNo ratings yet

- DTCM Holiday Homes Administrative Resolution No 1 of 2020 - EnglishDocument16 pagesDTCM Holiday Homes Administrative Resolution No 1 of 2020 - EnglishSomar KarimNo ratings yet

- Life Certificate 2017Document6 pagesLife Certificate 2017Venkateswarlu YadavalliNo ratings yet

- Batangas City v. Pilipinas Shell Petroleum Corp.Document2 pagesBatangas City v. Pilipinas Shell Petroleum Corp.Noreenesse Santos100% (1)

- Non Fatal OffencesDocument5 pagesNon Fatal OffencesAimi AzemiNo ratings yet

- Making Agencies of Pakistan's Foreign PolicyDocument17 pagesMaking Agencies of Pakistan's Foreign Policysyed tayyab sheraziNo ratings yet

- Volleyball GuidelinesDocument1 pageVolleyball GuidelinesBlaggog channelNo ratings yet

- Company Law and Secretrial PracticeDocument3 pagesCompany Law and Secretrial PracticeGuruKPONo ratings yet

- Andres vs. Cabrera 127 Scra 802Document6 pagesAndres vs. Cabrera 127 Scra 802Anonymous tJZb7XGNo ratings yet

- The 1973 Constitution of Pakistan Was Adopted On April 12Document11 pagesThe 1973 Constitution of Pakistan Was Adopted On April 12Sheraz AliNo ratings yet

- SpitzDocument30 pagesSpitzprabhatNo ratings yet

- USA V Loehrke SD-MJCase - Order Conditions of ReleaseDocument2 pagesUSA V Loehrke SD-MJCase - Order Conditions of ReleaseFile 411No ratings yet