Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 viewsThe Feminist Philosophy - Philosophy The Power of Ideas

The Feminist Philosophy - Philosophy The Power of Ideas

Uploaded by

Parisa UjjanCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

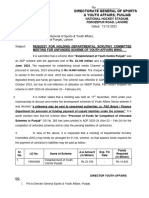

- Youth Center LetterDocument2 pagesYouth Center LetterParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Final ProjectDocument13 pagesFinal ProjectParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- NullDocument20 pagesNullParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Men and Women - Pleasures of PhilosophyDocument14 pagesMen and Women - Pleasures of PhilosophyParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- CamScanner 11-02-2022 15.33Document19 pagesCamScanner 11-02-2022 15.33Parisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Pak Us Relations 1947-2020 Notes - 1Document14 pagesPak Us Relations 1947-2020 Notes - 1Parisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- InterventionDocument3 pagesInterventionParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Human RightsDocument7 pagesHuman RightsParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Over Population - Current AffiarDocument7 pagesOver Population - Current AffiarParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Pakistan - China Enduring EntenteDocument6 pagesPakistan - China Enduring EntenteParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Terrorism 2Document21 pagesTerrorism 2Parisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Pakistan and IndiaDocument4 pagesPakistan and IndiaParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Internationla OrganizationsDocument11 pagesInternationla OrganizationsParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Pak Russia RelationsDocument7 pagesPak Russia RelationsParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Terrorism From BookDocument12 pagesTerrorism From BookParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Politics of New Provinces in Pakistan: A Historical AnalysisDocument10 pagesPolitics of New Provinces in Pakistan: A Historical AnalysisParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Punjabi Notes - 051959Document97 pagesPunjabi Notes - 051959Parisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Trade War PresentationDocument22 pagesTrade War PresentationParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

The Feminist Philosophy - Philosophy The Power of Ideas

The Feminist Philosophy - Philosophy The Power of Ideas

Uploaded by

Parisa Ujjan0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views50 pagesOriginal Title

The feminist philosophy - Philosophy The Power of Ideas

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views50 pagesThe Feminist Philosophy - Philosophy The Power of Ideas

The Feminist Philosophy - Philosophy The Power of Ideas

Uploaded by

Parisa UjjanCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 50

Tore-srde: Pitsopy oer veies Treen risopiy — T onenccan |

444

‘he Power lens Sith. compi 2085

14

Feminist Philosophy

Feminism is an entire world view or Gastak. net just a laundry list of

“womens issues” — Charlotte Bunch

Girls and boys develop different relational capacities and senses of

Sef as a result of growing up in a Family in which women mother.

—Nangy Chodorow

‘As nature [during the scientiic revolution] came to seem more like a woman

‘whom itis appropriate to rape and torture than like a nurturing mother.

did rape and torture come to seem a more natural relation of men to

women? — Sandra Harding

‘eminist thought is often divided into two waves. The first, from the late eigh-

teenth century through the early part of the twentieth century, tended to focus

‘on legal issues, especially women’s enfranchisement, and included as a notable ac~

‘complishment in the United States the vote for women in 1922. The second wave,

still happening, began in 1949 with the publication of Simone de Beauvoir’s The

‘Second Sex. The second wave has focused more on personal issues, especially the

personal relations between men and women, and is often referred to nowadays as

feminism.

THE FIRST WAVE

‘One of the grandmothers of feminist thought was Mary Wollstonecraft (1759—

1797), who wrote in response both to what she saw around her and to some of the

views about women that the philosophers of the time were putting forward. Her

mother and sister were both victims of domestic violence, which caused her to take

Tore-srde: Pitsopy oer veies

‘emia Phiesopiy |

onenccan |

‘he Power lens Sith. compi 2085

don

id XO) a] Bay

Chapter M4 + Feminist Philosophy 445

eee eed

‘not happy; her father was an unsue=

‘cessful gentleman farmer who squan=

ee ees

his frustrations on his wife and chile

dren, While still uitea young woman,

‘Wollstonecraft stuck out on her «wen

to London to become a write. After

some early years of stuggle, her work

began to gain considerable acceptance

‘among the intelligentsia of London society. She was

ete eae ee

ication of the Rights of Woman.”

“er personal life was unconventional and tue

Bee ee ee eee

birth of her frst daughter, Fanny. When Fanny was

stil very young, Wollstonecraft mst William God-

win, the political anarchist. They were well matched

intellectually and emotionally, and after Wollstone-

craft became pregnant, they married. Their ifeto-

died from complications following the

alivery of the child. Godwin was dev=

stated at Wollstonecraft’s death and

‘wrote a tender book of memoirs about

hher. This book caused significant public

‘scandal both for Wollstonecraft and for

‘Godwin, since he made no effort to hide

the illegitimacy of er first child or the

fact that she was pregnant when they

rmutried.

Iysshe Shelley and went on to write the novel

Frunkenstin. Mary Shalley had no interest in worn

ns rights and spent considerable energy trying

el alee ed eed

lives. It-was not until the end of the nineteenth

‘century tha te scandal associated with Mary Wol-

‘stonecraft died down enough to permit later femi-

nists to include her name in thei ists of honorable

forebears.

‘gether was cut short, however, when Wollstonecraft

issue with the idealized view of marriage being put forth by her culture. As an in-

tellectual, she was familiar with many of the high-minded views of womanhood

her contemporaries perpetuated. She was particularly annoyed at Rousseau’ view

of women because he advocated that women's education should be designed en-

tirely to make them pleasing to men. “To please, to be useful to us, to make us love

and esteem them, to educate us when young and take care of us when grown up,

to advise, to console us, to render our lives easy and agrecable— these are the du-

ties of women at all times, and what they should be taught in their infancy,” re~

flected Rousseau. Wollstonecraft employed several arguments against Rousseau

and his allies.

First, she argued that educating women to be the ornaments to, and playthings

of, men would have bad consequences for society. How could silly, vain creatures

ever be expected to do an adequate job of raising a family? They would become

“mere propagators of fools.”

Second, she argued that raising women to be ornamental would have bad con-

sequences for women. No matter how charming a woman might be, after a few

years of daily contact, her husband would ultimately become somewhat bored and

distracted. If women have no inner resources to fall back on, Wollstonecraft ar~

gued, they will then “grow languid, or become a spring of bitterness,” and love will

turn to jealousy or vanity.

‘Third, and perhaps most important, she argued that women were as ca-

pableas men of attaining the “masculine” virtues of wisdom and rationality, if only

Tore-srde: Pitsopy oer veies ‘emia Phiesopiy | onenccan |

‘he Power lens Sith. compi 2085

society would allow those virtues to be cultivated. She noted that the “vines” of

‘women —docility, dependence, and sensitivity —were commonly associated with

‘weakness. She held that there should be no distinction between female excellence

and human excellence. Like many intellectuals of the Enlightenment, Woll-

stonecraft gave pride of place to rationality and argued that women must develop

their capacity for reason to its fullest extent if they were to become excellent ex-

amples of humanity.

‘Wollstonecraft painted an unflattering portrait of the “ideal” woman ofher era.

Imagine what women would be like, she said in effect, if they did nothing but read

the equivalent of today’s Harlequin romances and aspired to be like the passive,

‘swooning heroines of these books. Some women might be successful at imitating,

such heroines, and might enjoy themselves for a while, but Wollstonecraft pointed

‘out that once past age nineteen or so, there is litle left for such women to do with

their lives. She suggested that women who have no other ambition than to inflame

passions will have no real strength of character, no true moral virtue, and no inner

resources. It was time, Wollstonecraft argued, to restore women to their lost dig~

nity by encouraging better ideas of womanhood.

‘Utopian philosophers were also important in the struggle for women’s rights.

‘Who were the utopian philosophers? They were utilitarian reformers — social re~

formers who subscribed to the philosophy of Jeremy Bentham (see Chapter 10)—

who wished to structure society so as to produce the greatest happiness of the

greatest number. They envisioned societiesin which all members were social equals,

Where education was reformed to promote the development of “benevolent” or

“tumanistic” feelings of mutual care and concern, and where property was redis~

tributed to the benefit of all members of society. Model utopian societies sprang

up in Europe and the United States; the utopian movement culminated in the late

nineteenth century. For utopians, societies should help people feel they are doing

something important for themselves, their families, and their communities; in an

ideal society, people would work only because they wanted to, and they would want

to work because they would understand that their work helps make their commu-

nity a great place to be. Yet at that time the largest and most exploited (because un-

paid) labor force was women, a fact that did not escape the attention of Anna

Doyle Wheeler (1765—1833), a utilitarian reformer.

‘Wheeler was an Trish feminist, a self-educated philosopher, and an avid utili=

tarian who published numerous articles (under various pseudonyms) and frequent

translations of French socialist philosophical writings. Jeremy Bentham introduced

to Wheeler the utopian /reformist philosopher and economist William Thomp-

son (1775-1833); Wheeler and Thompson collaborated on a famous essay titled

“The Appeal of One Half of the Human Race, Women, against the Pretensions of

the Other Half, Men, to Restrain Them in Political, and Thence ia Civil and Do-

mestic, Slavery.” In the essay, published in 1825, Wheeler and Thompson argued

that denying rights to women is in fact contrary to the interests of the whole of so-

ciety and, accordingly, is not consistent with the greatest happiness of the greatest

‘number. They also argued that denying rights to women is just plain unjust; many

‘commentators think a more stirring defense of equal rights for men and women has

never been put forth.

Another important utilitarian was Harriet Taylor (c. 1807-1858), who until

recently was most often remembered through her connection with John Stuart Mill.

Tore-srde: Pitsopy oer veies ‘emia Phiesopiy | onenccan |

‘he Power lens Sith. compi 2085

Chapter 14 + Feminist Philosophy 447

“Taylor also thought that the nonphysiological differences henween men and women

were socially constructed, to the detriment of women and of society in general. She

was a vociferous proponent of women's suffrage and used several arguments from

justice in support of her appeal. Everyone agreed there should be no taxation with-

out representation; well, she pointed out, many unmarried women paid taxes on

their property yet could not vote for the government that spent their money. She

argued that we cannot make arbitrary distinctions between groups of people with-

out giving good reasons for doing so, and no good reasons could be given for say-

ing that men could vote and women could not. The burden of proof should be on

those in favor of discrimination, not on those who oppose it. And, Taylor argued,

the differential in freedom between men and women was so drastic— including not

only political liberty but personal freedom as well—that no good reasons could

possibly be advanced for the discrimination. Eventually, of course, the rest of the

British public saw it her way and women were given the vote. Taylor also provided

the classic answer to the question, Why should women have a voice in government?

(See the box by that title.)

‘The first wave of feminism saw some dramatic results, including changes in the

laws regarding women’s property rights and the right to vote. After 1920, when

women in the United States obtained the right to vote, active theoretical work on

feminist issues subsided for a few decades. But the larger social problems did not

go away, and theorists who had hoped that the right to vote and own property

would resolve the problem of women’s lower social and economic status saw those

hopes vanish. Women were still educated differently, still viewed primarily as or~

namental and nurturing, still paid less, and still seen as having a lower fundamen-

tal worth than men.

THE SECOND WAVE

Philosopher and novelist Simone de Beauvoir [bow-VWAHR] (1908-1986)

recognized the problem. The earlier ferninists were primarily English and Ameri-

can. They had been steeped in the traditions of empiricism and utilitarianism.

De Beauvoir came from the Continental traditions of existentialism and phenom-

enology, and her approach focused less on the public world of laws, rights, and ed-

ucational opportunities and more on the cultural mechanisms of oppression, which

left women in the role of Other to man’s Self. She developed this notion of wom-

er’s essential othemess in her book The Second Sex.

And what a book. De Beauvoir undertook a sweeping analysis of all the ideas

and forces that conspired to keep women in a subordinate position relative to

men, Herexamination encompassed Freud, Marx, the evidence of biology, the evi-

dence of history, representative novelists, and what we would call the evidence of

sociology. There had not previously been anything like this systematic and sus-

tained analysis of the condition of women; de Beauvoir’s work was unique.

But its very scope makes it a difficult book to summarize or outline. De Beau-

voir, like some of her existentialist colleagues, was more interested in the fascinat-

ing variety of theoretical approaches than in the project of making them — or her

Tore-srde: Pitsopy oer veies

‘emia Phiesopiy |

(Ohana

‘he Power lens Sith. amp, 205

don

448 Part Four + Other Voices

‘The classic answer was provided by Harriet Taylor,

‘who was discussed earlier.

Even those who do not look upon a voice in the

goverment as a matter of personal right, nor

profess principles which require tha it should

be extended to all, have usualy traditional

raxims of political justice with which its im-

possible to reconcile the exclusion of all women.

from the common rights of citizenship. Ieis an

axiom of English freedom that taxation and

representation should be coextensive. Even un-

der the laws which give the wife's property to

the husband, there are many unmarried women

‘who pay taxes. It i one of the Fundamental

doctrines ofthe British Constitution, that all

persons should be tried by their peers: yet

‘women, whenever tied, are tried by male

jndges and a male jury. To foreigners the law

sccords the privilege of claiming that half the

jary should be composed of themselves; not 10

to women. Apart from maxims of detail, which

represent local and national rather than univer-

‘al ideas: itis an acknowledged dictate of justice

to make no degrading distinctions without ne-

cessiy, In all things the presumption ought vo

be on the side of equality. A reason must be

given why anything should be permitted to one

person and interdicted to another. But when

that which is interdicted includes nearly every-

Why Should Women Have a Voice in Government?

thing which those to whom itis permitted most

prize, and to be deprived of which they feel to

’be most insulting: when not only political

erty but personal freedom of action is the pre~

rogative ofa caste; when even in the exercise of

industry, almost all employments which task the

higher faculties in an important field, which

lead to distinetion, riches, or even pecuniary in-

dependence, are fenced round as the exclusive

domain of the predominant section, scarcely

any doors being left open to the dependent

class, except such as all who can enter else-

‘where disdainflly pass by; the miserable expe-

diencies which are advanced as excuses for $0

‘grossly partial a dispensation, would not be

sufficient, even if they were rea, 10 render it

other than a flagrant injustice. While, far from

being expedient, we are firmly coavinced that

the division of mankind into fo castes, one

‘born to rule over the othe, isin this cas, as

inall cases, an unqualified mischief; a source

‘of perversion and demoralizaton, both to the

favoured class and to those at whose expense

they are favoureds producing none ofthe good

Which itis the custom to ascribe tit, and

forming a bar ... toany really vita improve~

‘ment, ether in the character or inthe socal

condition of the human race.

‘own views— completely consistent. Like other existenti

lists, she borrowed liber~

ally from the insights of psychoanalysis and from Marxian perspectives but tended

to ignore the deterministic conclusions of those approaches. No matter that we may

be controlled by our own internal psychodynamies or by the forces of economic

history; ultimately, we can always “transcend our own immanence,” create our

selves anew, and overcome the straitjackets of history and culture. This view, as you

‘can imagine, has important consequences for political action. Suppose you believe

that culture shapes individuals and that itis very hard, or impossible, to overcome

cultural conditioning. Then if you conclude that the condition of a particular

group, such as women, is not what it should be, you should emphasize that society

‘overall should change so that women will be changed. But if you think that the in

dividual can always overcome his or her circumstances, then you might argue that

individuals should focus on their own self-transformation. De Beauvoir argued that

society should change, but if you are a thoroughgoing existentialist, itis not clear

Tore-srde: Pitsopy oer veies ‘emia Phiesopiy | onenccan |

‘he Power lens Sith. compi 2085

Chapter 4 + Feminist Philosophy 449

PROFILE: Si

femmes erent

the Sorbonne second in her class,

behind only Simone Wei, the Jewish

eae eres

sity, she met Jean-Paul Sartre, Mau-

rice Merleau-Ponty, and many other

young intellecials who would go on

to prominence in twentethcentary

French lewers and polities. Some of

thee men and women formed the

‘group that Sarve and de Beauvoir

‘would call “The Family"—a collec ieee eee

tion of writers, actors, and activists pressed for marriage, but de Beauvoir

who associated for intellectual stimu ‘vas opposed tothe institution and une

eet tee ete ce eae

De Beauvoir and Sarre formed a parmership mained active and invelved with writing, traveling,

‘while they were in their early twenties. Sartre de- and constant political work unt close tothe end of

cided that theirs was an “essential” love that ber life

would be most important in their

lives—but that did not rule out

“contingent” love affairs with other

people. Indeed, Sartre went on to de-

velop a reputation as one of France's

most compulsive womanizers. De

Beauvoir consistently claimed that

Sartre's myriad one-night stands did

not bother her at al, She herself

formed several yearslong_ liaisons

with other men, most notably Nelson

Why you should not focus on your own personal transformation to overcome the

culture.

‘Whatis a woman? de Beauvoir wondered. It cannot bea simple biological cate~

gory, for there are people who have the relevant biological equipment who are

nevertheless excluded from “womanhood.” In one of her most famous passages,

de Beauvoir argues that “one is not bor, but rather becomes, a woman.” The cate~

gory of womanhood is imposed by civilization. And the fundamental social mean-

ing of womanis Other. De Beauvoir held, “No group ever sets itself up as the One

without at once setting up the Other over against itself.” She argued that people in

small towns do this to strangers, natives of one country will view natives of another

country as Others, and members of one race will invariably set up the members of

another race as Others. Others are mysterious and almost by definition need not

be treated with the same consideration and respect that the members of one’s own

group must he accorded. Men set up women 28 Others, de Beauvoir observed, and

since men have the political and social power, women come to see themselves as

Others. They become alienated from themselves.

As she articulated what it was like to be the Other, de Beauvoir ridiculed cer

tain popular myths, including that of “feminine mystery.” Very handy concept, she

pointed out. To paraphrase her, if you do not understand what another person is

complaining about, well, you need not bother to listen sympathetically or place

yourself imaginatively in that person's position. Just say, “Oh well, members of that

group are justso mysterious!” and you are off the hook. If they want something dif

ferent from what you want, you do not need to give equal weight to their prefer~

ences because everyone knows that their preferences are mysterious. De Beauvoir

Tore-srde: Pitsopy oer veies

‘emia Phiesopiy |

(Ohana

‘he Power lens Sith. amp, 205

don

450. Part Four + Other Voices

Feminism comes in lots of varieties: socialist,

psychoanalytic, postmodern, radical, and. beral

“These last two are the kinds you hare probably

come across the most often when reading the pa~

pers and popular magazines. Leaming the differ-

ences between the two ean help you make sense of

the next editorial you read on women's issues.

Liberal feminism has its roots in some very

traditional American notions: freedom of choice

and equality of opportunity. Liberal feminists insist

that women can do everything men dof only they

are given a fair chance. Liberal feminists do not

generally ask whether the things men are doing are

really worth doing. Nor do they challenge those

‘women who are living out traditional roles. Their

focus is on making sure there is freedom and op=

portunity for those wino do nor want to live out ta

ditional roles. Liberal feminists tend to focus on

changing restrictive laws and climinating formal

bartiers to womed's advancement.

Liberal Feminism and Radical Feminism

Radical feminists think the problems run very

deep and that the solutions mustcut deeptoo. They

argue that entrenched socalarttades do as much or

rmore harm than restrictive laws. To change socal

aatitudes 40 that women are tken seriously, ey

think drastic steps must be taken, In particular, they

believe that reducing women to ther sexuality is the

eet eee

Jence,and general contempt for women. Thus, they

target cultural phenomena such as pomography,

tae eri ee Care eee eed

4s nothing but sexual toys. Liberal feminists object

that protesting these phenomera is foo much like

censorship and, hence, contrary to freedom. Radi=

cal feminists reply that unt women are safe from

violence in the street and in ther own homes, they

‘will never truly be free.

pointed out that men had conveniently argued not that women were mysterious to

‘men—that might imply that men were stupid— but, rather, that they Were myste~

rious objectively, absolutely.

One final consequence of de Beauvoir's existentialist perspective is that she

does not emphasize freedom of choice to the same extent that the English writers

do, Not all choices are okay. From de Beauvoir’s perspective, if all you do is stay

home and have babies, then you might as well be a brood mare. After all, all

animals reproduce; there is nothing distinctively human about simple reproduc

tion, Distinctively human activity is the activity of the mind, of culture, and of seli=

transcendence.

‘The publication of The Second Sex in 1949 created a furor, and de Beauvoir

was startled at the vitriolic response that many critics had toward her work. But

there was no turning back; the ideas were now rolling again, and over the next thirty

years there would be a huge resurgence of feminist thought. The end of the socially

turbulent 1960s was a particularly fertile time for feminist theory (it was also when

the public began talking about “radical feminists”; see the box “Liberal Feminism

and Radical Feminism” for one explanation of “radical feminism”). The five-year

period from 1968 to 1973 saw publication of several classic feminist texts, includ

ing Robin Morgar’s Sisteriood Is Powerful (1970) and Kate Millett’s Sexual Poli=

tics (1970). Influential in bringing feminist thinking to the attention of the larger

public was Gloria Steinem (sce Profile).

‘Kate Millett’s work was inspiring to many writers because she gave a system~

atic analysis of how women are oppressed by patriarchal institutions. Her work was

Tore-srde: Pitsopy oer veies ‘emia Phiesopiy | onenccan |

‘he Power lens Sith. compi 2085

don

Chapter 14 + Feminist Philosophy 451

(One of the best-known contemporary

feminists is Gloria Steinem. Steinem

‘was bom into a working-class family

in Toledo, Ohio, in 1934. Her parents

were divorced when she was relatively

young, and she spent much of her

‘youth and adolescence in relative pov=

‘erty, caring for her emotionally un-

stable mother, She graduated from

‘Smith Colleze in 1956 and began her

career 2s a jouralist. In the 1960s

‘she became involved in the women's

movement and has remained one of

‘ions in dorms or shared housing, and

are generally equally rewarded by

their professors for hard work. Thus,

for many women college students, the

feminist battles all seem to be won;

‘men and women are equal. Not until

young women get out into the work=

ing world and are faced with (for ex-

‘ample) the fact that male high school

sraduates still earn, on average, more

than female college graduates, do the

differences between men's and wom

‘en's situations become more apparent.

feminism’s most visible and recognizable activists.

Probably her single most important accomplish

‘ment was helping to found the original Ms. maga-

zine, which brought women’s perspectives and is~

‘sues to the attention of mainstream America,

Steinem has written insightfully on many issues,

inclading the differences between male and female

college students. Young men, she noted, are often at

‘their mest radical and rebellious during theit college

‘years. Young women often start out quite conserva

tive in their early twenties and become more radical

‘and politically oriented only later on. Steinem sug-

‘gests that this difference stems from the divergence

in men's and women’s lives as they get older.

‘In college, all students, male and female, are

‘more or less equally poor, have equal living situa

Furthermore, women come to recognize that chil-

‘dren are still largely considered the mother’s re-

sponsibility, so the problems of combining career

‘and parenthood rest more heavily on them than

Finally, women in ther late teens and early twen-

ties are at the peak of their social power: stil very

sexually desirable, sil full of potential as wives and

childbearers. As women age, however, they lose this

social power as their attractiveness fades, and this

loss can be a very radicalizing experience —partic-

ularly when their gray-haired male contemporar~

ies are stil being called distinguished, instead of

haggard,

inspiring to many because she challenged these who suggested that women actu

ally had lots of power to look at the avenues of power. She ran through the list:

industry, the military, technology, academia, science, politics, and finance. How

many of these avenues of power had women at the top ranks? There might be

women bank tellers, but how many large banks had women presidents or even vice

presidents? How many women were in Congress? How many women were gen-

erals? How many women university presidents—or even tenured professors?

Millet directed attention not to personal relationships but, rather, to the struc

ture of society. She also looked at the socialization process and observed that the

characteristics systematically encouraged in women— passivity, ignorance, docil-

ity, “virtue”—were those that made them convenient subordinates. Millett focused

especially on the way the political, sociological, and psychological aspects of male—

female relations were interrelated, If you have to take on a certain type of role in

society, Millett maintained, it is to your advantage to develop the psychological

Tore-srde: Pitsopy oer veies ‘emia Phiesopiy | onenccan |

‘he Power lens Sith. compi 2085

don

452 Part Four « Other Voices

characteristics that make that role easier. One of Millett’s major contributions to the

second wave of feminism was to make these links explicit.

‘Another classic text from this period was Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialec~

tic of Sex (1970). Now the writers discussed in this chapter take it for granted that

‘women’s subordinate status is a social and political problem, not a biological one.

Almost all feminists think that the biological differences between men and women,

‘though real, are not in themselves anywhere near sufficient to explain the extremely

diiferent social roles men and women play. Conservative thinkers such as Freud,

who argued that anatomy is destiny, are routinely dismissed by contemporary fem-

inists and other social philosophers. Firestone argued that women’s childbearing

‘was at the root of their social oppression. Thus, she might be categorized as a bio~

logical determinist. She argued that reproductive technology was the route to wom-

en's freedom; developments that liberated women from having to bear and nurse

children would free them to participate as equals ia the new society.

Firestone was not an unguarded optimist, though. She argued that reproduc

tive technology could be used against women as well as for them. Therefore, it

would be necessary for women to seize control of the new fertility technology to

make sureit was put to legitimate uses. Firestone suggested that if babies were born

through artificial reproduction, they would be born to both sexes equally and that

“the tyranny of the biological family would be broken.”

Androgyny as an Alternative

‘Suppose you have become convinced that de Beauvoir was right, that people have

an unfortunate tendency to set themselves up as Self versus Other, or Us versus

‘Them. One solution that might seem hopeful is to eliminate the differences be-

‘tween groups of people as much as possible so that there would be less reason to

feel that the members of a different group were Others. This is the logic of the

“melting pot” ideal of race relations. If there were no more distinet races but,

rather, only one blended race, there would be no more basis for racism.

‘Well, if there were no obvious differences between the sexes, there would be no

‘more basis for sexism either. There is, of course, no possibility (in the near future)

of completely eliminating the biological differences between the sexes; our repro~

ductive plumbing will probably remain different. But as almost all feminists have

observed, there are very few other differences between men and women that are

not socially constructed. Certainly it seems likely that men’s and women’s bebav-

iors and interests are formed more by society than by biology. There is plenty of

evidence for that claim from anthropology and biology. In some cultures women

adorn their bodies, and in some cultures men do. In some cultures men are re-

sponsible for the finances, and in other cultures women are. For almost every

behavior you can name, there has probably been at least one culture in which it was

‘men’s purview and another in which it was women's.

‘You may think that women are physically weaker than men, and they may be

asa general rule, but think how different they might be if they were raised to de~

velop their physical strength as a matter of course. After all, women athletes are

hardly fragile flowers. And if you compare women who do manual labor for a liv-

Tore-srde: Pitsopy oer veies ‘emia Phiesopiy | onenccan |

‘he Power lens Sith. compi 2085

Chapter 14 + Feminist Philosophy 453

ing with men who sit behind desks pushing pencils, you will hardly conclide that

women are naturally weaker than men. A lot of that strength difference is culturally

imposed, as are the more subtle social differences between men and women.

‘So many feminists in the late 1960s and early 1970s concluded that perhaps

androgyny (from andros, the Greek word for man, and gyne, the Greek word for

woman) would be the ideal solution. No more setting up one group as the Other;

instead, let’s all be one homogencous group. Since there will be no other set, one

set of people will not be able to abuse the other set.

An androgynous culture could take several forms. First, you could have a cul-

ture in which everyone, girls and boys, are raised exactly the same: given the same

education, the same games to play, the same challenges to face, the sme rules to

follow. You would probably end up with a culture where it was not immediately

apparent which people were female and which were male. ‘There would be no sex

roles; no concept of masculine and feminine. There would be orly one standard

for everyone.

Or you might have a culture in which there are concepts of masculine and

feminine, but they are not directly matched with males and females. So you could

have “feminine” men and “masculine” women. For such a society to work and re~

ally be free, there could be no social stigma attached to being a “masculine” woman

ora “feminine” man. All choices would be equally acceptable. A very free world,

indeed.

‘The first possible society, called monoandrogyny, is endorsed by Ann Fer-

guson. In her influential essay “Androgyny as an Ideal for Human Development”

(1977), Ferguson argues that since men and women are socially unequal, there can

be no true love between them. Ideal love is the love between equals. Ferguson also

suggests that because of this lack of ideal love, we are all unable to develop fully as

hhuman beings. She argues that a truly androgynous society would allow us all to

develop fully as human beings.

‘What would an androgynous personality be like? Ferguson wondered. Well,

both men and women need to be active, independent, creative, and productive.

‘They both need meaningful involvement in their community. Ferguson believed

that being active and assertive were rightly thought of as valuable human char-

acteristics, not just valuable male characteristics. Active and assertive did not

necessarily mean aggressive and competitive: if we eliminate the competitive, hier

archical aspects of the culture, we might produce assertive people who were also

cooperative and supportive of one another. Androgynous men would be more sen-

sitive to the needs and concerns of others than they are now. This would make them

better parents, among other things. But equally important, men and women would

be able to enjoy much richer relationships with each other because they would have

more in common. Shared experiences and shared activities frequently lead to

deeper bonds between people. If men and women were raised androgynously, they

would have more communication, more companionship, and deeper love and un-

derstanding for cach other. Ferguson's hope was that a monoandrogynous society

would lead to more loving and deeply mutual relationships between people.

Joyce Trebilcot, in “Two Forms of Androgynism” (1977), argues for the

second type of androgynous society. She suggests that we need not eliminate the

categories of “masculine” and “feminine.” Instead, we should just let individuals

Tore-srde: Pitsopy oer veies ‘emia Phiesopiy | onenccan |

‘he Power lens Sith. compi 2085

don

454 Part Four + Other Voices

choose which type of role they wish to adopt. She calls this type of society P for

polyandrogyny, and contrasts it with hypothetical society M, for monoandrog-

yny, the type of society Ferguson was arguing for. Trebilcot argues that society

Pis better than society Mbecause P allows individuals greater freedom of choices

bbut she ends by suggesting that if Mis really the better society, then people will

probably eventually freely choose it.

‘Trebikeot was more concerned with freedom of choice than with fostering lov

ing and matual relationships between people. She understood the persuasive force

of Ferguson's argument and reflected on the characteristics that might be valuable

for both sexes. From traditionally feminine traits, she thought that openness, re~

sponsiveness, compassion, expressiveness, and tenderness might be good qualities

for all to have. From the traditionally male basket, she believed that being logical,

objective, efficient, responsible, independent, and courageous would benefit every

‘one. But Trebilcot was concerned how one might prove that these traits were good

for everyone. She argued that the best test would be to allow everyone to pick what-

ever traits he or she might like to have. Then, once everyone was fully informed and

‘genuinely free to choose what type of person to be, pethaps everyone would in fact

choose monoandrogyny. Trebilcot argued that polyandrogyny was the best strat

egy to adopt because it preserved freedom and would lead to monoandrogyny

anyway if monoandrogyny were indeed the best type of society to have.

Problems with Androgyny as an Ideal

Although the logic behind the push for androgyny seemed reasonable, after a while

some feminist theorists began to see that it had some deep conceptual problems. It

‘was all very well to say that there were good feminine qualities and good masculine

‘qualities and that everybody should have some of each, but what if those qualities

were really direct opposites? It would then be impossible to combine the two sets

of qualities because they would simply cancel each other out. If the ideal for one

set of people is to be rational, calm, and silent, and the ideal for the other set is to

bbe emotional and expressive, it is difficult to see how those qualities could all be

‘combined to make one whole, balanced human. Feminist philosopher Mary Daly,

whose work is discussed further in Chapter 13, argued that androgyny as an ideal

would not work because it would be like “two distorted halves of a human being

stuck together [something like Jennifer Aniston and Brad Pitt (our example, not

Daly’s) scotch-taped together] as if two distorted ‘halves? could make a whole.” Af-

ter all, one cannot expect to combine the concept of “master” and the concept of

“slave” and get the concept of a free person. The original concepts are both too

warped to be usable. According to Daly, we must completely transcend those orig

inal categories and start over from scratch.

‘More evidence for the view that the categories of “masculine” and “feminine”

were too broken ever to be fixed came both from the social sciences and from

‘erature and philosophy. At the beginning of the 1970s, it was often remarked that

gender roles inhibited everyone, male and female alike. Men were cut of touch

With their feelings and were unable to cry or show affection publicly. But soon

people began to realize that masculine behavior, though limiting, limited men tothe

Tore-srde: Pitsopy oer veies ‘emia Phiesopiy | onenccan |

‘he Power lens Sith. compi 2085

Chapter 4 + Feminist Philosophy 455

positions of power that Kate Millett listed in her book Sexual Politi. Ifyou are une

able to cry and show emotion, by the standards of our culture, that makes you a

very good candidate for being a CEO or high-level politician since we would not

want them to fall apart emotionally ata crucial moment. Of course, being unemo-

tional is not a sufficient condition for being a CEO, but itis a necessary one. Simi

larly, being ambitious and competitive—traits generally valued in men—keeps

them from settling down to a nurturant family role, but it also “limits” them to a

better economic position. Some people argue that itis a greater benefit to be able

to be expressive and nurturing than to be able to earn in the six figures. It certainly

is not bad to be expressive and nurturing, but ask yourself this: Would you rather

bbe expressive and emotional while living just above the poverty line? Or would you

rather be a little more closed off emotionally and earn a comfortable living? Those

are too often the real alternatives that face men and women today.

In her important 1983 article, “Sexism,” Marilyn Frye argues that the whole

system of gender is really one of power. She implies that masculinity is about domi-

nance and that femininity is about subordination, She notes that we go to a great

deal of trouble to keep the sexes distinct; even products that have no inherent dif

ferences —like shampoos, deodorants, and razor blades —are packaged differently

for men and women. Men and women talk, move, and sit differently from each

other. In a myriad of unnecessary details, men and women are trained to keep

themselves distinct from each other. This whole process contributes to the domi-

nance/subordination dynamic, Frye argues.

‘Or consider clothing. Ever since feminism first got media attention in the

1960s, there has heen a lot of fuss over the way some women who are feminists

dress. Many people criticize feminists for looking sloppy and unfeminine. Actually,

however, most political and social groups eventually develop a general style of dress

that helps them form a sense of community and solidarity. But for feminism, the

issue goes deeper. High heels, short skirts fragile fabrics, and tight-fitting jeans

erally hobble women; they keep women more confined and uncomfortable than do

the styles mea wear. Frye observed that “ladies? clothing is generally restrictive,

binding, burdening and frail; it threatens to fall apart and for to uncover something

that is supposed to be covered if you bend, read, kick, punch, or run.” (And be-

cause physical assaults an all-too-real possibility for most women, being unable to

defend yourself isa genuine problem.)

For one group to oppress another, Frye reasoned, there must be (at least) two

distinct groups. ‘The more differences between the members of one group and the

members of the other group, the better because then it will seem more rational to

treat the nwo groups differently. So, Frye argues, those thousands of ways in which

artificial differences between women and men are reinforced are all litle acts of

sexism. It may seem harmless to have men’s colognes and women’s colognes,

‘women’s deodorants and men’s deodorants, and so on, but every time we reinforce

the view that men and women are inherently different, we also reinforce the notion

that they must inevitably be treated differently. Anything that contributes to the ap-

pearance of extreme natural dimorphism also contributes to the practice of male

dominance and female subordination.

But there is a double bind here, which particularly harms women. If women

are traditionally feminine, then they are participating in social practices that limit

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Youth Center LetterDocument2 pagesYouth Center LetterParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Final ProjectDocument13 pagesFinal ProjectParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- NullDocument20 pagesNullParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Men and Women - Pleasures of PhilosophyDocument14 pagesMen and Women - Pleasures of PhilosophyParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- CamScanner 11-02-2022 15.33Document19 pagesCamScanner 11-02-2022 15.33Parisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Pak Us Relations 1947-2020 Notes - 1Document14 pagesPak Us Relations 1947-2020 Notes - 1Parisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- InterventionDocument3 pagesInterventionParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Human RightsDocument7 pagesHuman RightsParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Over Population - Current AffiarDocument7 pagesOver Population - Current AffiarParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Pakistan - China Enduring EntenteDocument6 pagesPakistan - China Enduring EntenteParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Terrorism 2Document21 pagesTerrorism 2Parisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Pakistan and IndiaDocument4 pagesPakistan and IndiaParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Internationla OrganizationsDocument11 pagesInternationla OrganizationsParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Pak Russia RelationsDocument7 pagesPak Russia RelationsParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Terrorism From BookDocument12 pagesTerrorism From BookParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Politics of New Provinces in Pakistan: A Historical AnalysisDocument10 pagesPolitics of New Provinces in Pakistan: A Historical AnalysisParisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Punjabi Notes - 051959Document97 pagesPunjabi Notes - 051959Parisa UjjanNo ratings yet

- Trade War PresentationDocument22 pagesTrade War PresentationParisa UjjanNo ratings yet