Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1 SM

1 SM

Uploaded by

nersrosdianaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Developing Competencies of NurDocument10 pagesDeveloping Competencies of NurnersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- Theory of Swift Even FlowDocument6 pagesTheory of Swift Even Flowjacinta100% (1)

- Vasan Eye Care Hospital ProjectDocument86 pagesVasan Eye Care Hospital Projectkavilankutty100% (1)

- 7s PresentationDocument54 pages7s PresentationMish Lim67% (3)

- GHS - An Introduction To ADF On-Base Healthcare Delivery - 15092016Document9 pagesGHS - An Introduction To ADF On-Base Healthcare Delivery - 15092016jim STAMNo ratings yet

- Quality of Nursing Care Practices Among Select Hospitals in Bataan EditedDocument23 pagesQuality of Nursing Care Practices Among Select Hospitals in Bataan EditedZonllam Aryl DialorNo ratings yet

- Statement of The ProblemDocument2 pagesStatement of The ProblemCHARLESNo ratings yet

- Structured Mentoring StrategiesDocument31 pagesStructured Mentoring Strategiesrandy gallegoNo ratings yet

- Nurses Education and Motivation Towards Nursing DocumentationDocument5 pagesNurses Education and Motivation Towards Nursing DocumentationEdwardoNo ratings yet

- Journal of Global BiosciencesDocument25 pagesJournal of Global BiosciencesSamah IshtiehNo ratings yet

- Nursing Doc - EditedDocument5 pagesNursing Doc - EditedMORRIS ANUNDANo ratings yet

- What Influences Malaysian Nurses To Participate in Continuing Professional Education Activities?Document10 pagesWhat Influences Malaysian Nurses To Participate in Continuing Professional Education Activities?EHashim Al MunawarahNo ratings yet

- Teaching Competency of Nursing Educators and Caring Attitude of Nursing StudentsDocument26 pagesTeaching Competency of Nursing Educators and Caring Attitude of Nursing StudentsJaine NicolleNo ratings yet

- Transformational and Transactional Leadership Styles of Nurse Managers and Job Satisfaction Among Filipino Nurses: A Pilot StudyDocument14 pagesTransformational and Transactional Leadership Styles of Nurse Managers and Job Satisfaction Among Filipino Nurses: A Pilot StudyDanyPhysicsNo ratings yet

- Continuing Education in Nursing - EditedDocument7 pagesContinuing Education in Nursing - EditedOnkwani DavidNo ratings yet

- Van Patten 2019Document6 pagesVan Patten 2019Amrinder RandhawaNo ratings yet

- 169-Article Text-809-1-10-20220501Document9 pages169-Article Text-809-1-10-20220501Dwi NopriyantoNo ratings yet

- BrownDocument13 pagesBrownapi-255084253No ratings yet

- Nurse Managers' Responsive Coaching To Facilitate Staff Nurses' Clinical Skills Development in Public Tertiary HospitalDocument10 pagesNurse Managers' Responsive Coaching To Facilitate Staff Nurses' Clinical Skills Development in Public Tertiary Hospitalvan royeNo ratings yet

- Nursing 1Document5 pagesNursing 1Ray NamuNo ratings yet

- Clinical ReasoningDocument7 pagesClinical Reasoninglyndon_baker_10% (1)

- Journal Pone 0226804Document18 pagesJournal Pone 0226804Biman MondalNo ratings yet

- Health Notions, Volume 1 Issue 4 (October-December 2017) ISSN 2580-4936Document7 pagesHealth Notions, Volume 1 Issue 4 (October-December 2017) ISSN 2580-4936Muhammad DzikrullohNo ratings yet

- Performanta JobuluiDocument11 pagesPerformanta JobuluiBaciu AlessandroNo ratings yet

- Tugas Bahasa Inggris - Temu 1 - KLP 8 - A12 BDocument8 pagesTugas Bahasa Inggris - Temu 1 - KLP 8 - A12 BErina NiluhNo ratings yet

- The Influence of The IOM - SubmitDocument9 pagesThe Influence of The IOM - SubmitKerry-Ann Brissett-SmellieNo ratings yet

- Presentation BaderDocument15 pagesPresentation BaderBader AljarboaNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Pengetahuan Terhadap Kompetensi Mahasiwa Profesi Ners Dalam Penerapan Evidence Based PracticeDocument6 pagesHubungan Pengetahuan Terhadap Kompetensi Mahasiwa Profesi Ners Dalam Penerapan Evidence Based PracticeIwan AgustiNo ratings yet

- Influence of Emotional Intelligence, Communication, and Organizational Commitment On Nursing Productivity Among Korean NursesDocument8 pagesInfluence of Emotional Intelligence, Communication, and Organizational Commitment On Nursing Productivity Among Korean NursesSyifa AiniNo ratings yet

- Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice: A C B C B CDocument6 pagesJournal of Interprofessional Education & Practice: A C B C B CReny ParembangNo ratings yet

- Ffectiveness of An Evidence-Based Practice: E Educational Intervention Among School NursesDocument10 pagesFfectiveness of An Evidence-Based Practice: E Educational Intervention Among School NursesJV BernNo ratings yet

- Clinical Leadership 2022 PDFDocument16 pagesClinical Leadership 2022 PDFMaria Erika NuñezNo ratings yet

- Admsci 07 00017Document13 pagesAdmsci 07 00017SriMathi Kasi Malini ArmugamNo ratings yet

- Retaining Novice Nurses in A Healthcare OrganizationDocument8 pagesRetaining Novice Nurses in A Healthcare OrganizationRay NamuNo ratings yet

- Dedicated EducationalDocument5 pagesDedicated EducationalNovin YetianiNo ratings yet

- Assessment On The Level of Proficiency of ClinicalDocument7 pagesAssessment On The Level of Proficiency of ClinicalWinnie AriolaNo ratings yet

- Week 7 Discussion - Nursing LeadershipDocument6 pagesWeek 7 Discussion - Nursing LeadershipFranklin Mung'athia BettNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic Communication Through Simulation PDFDocument5 pagesTherapeutic Communication Through Simulation PDFNicole GadrinabNo ratings yet

- Plagerism FileDocument25 pagesPlagerism FileIqra AsimNo ratings yet

- (Comm) ResearchDocument2 pages(Comm) ResearchEngella BumagatNo ratings yet

- Nin Artikel IlmiahDocument11 pagesNin Artikel IlmiahNindhita SetyaningrumNo ratings yet

- Nurse's Foci of Commitment Model To Decrease Turnover IntentionDocument10 pagesNurse's Foci of Commitment Model To Decrease Turnover IntentionIJPHSNo ratings yet

- The Improvement of Student Competency in A Clinical Study in Indonesia: What Factors Played An Important Role?Document8 pagesThe Improvement of Student Competency in A Clinical Study in Indonesia: What Factors Played An Important Role?Ferry EfendiNo ratings yet

- Patient Assessment Responses in Nursing Practice To Enhance Patient Safety: A Systematic ReviewDocument2 pagesPatient Assessment Responses in Nursing Practice To Enhance Patient Safety: A Systematic ReviewFeaona MoiraNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Advanced Practice Nursing Education: Challenges and StrategiesDocument9 pagesReview Article: Advanced Practice Nursing Education: Challenges and StrategiesluNo ratings yet

- GondarDocument8 pagesGondarYared wolduNo ratings yet

- Mountain Province State Polytechnic College: School of Healthcare EducationDocument6 pagesMountain Province State Polytechnic College: School of Healthcare EducationMaller Chop's Pong-etNo ratings yet

- Sample Sample: Running Head: Evidence-Based Nursing Practice 1Document7 pagesSample Sample: Running Head: Evidence-Based Nursing Practice 1Henoke ManNo ratings yet

- Impacts of Iom On Nursing Practice, Education and Leadership RolesDocument5 pagesImpacts of Iom On Nursing Practice, Education and Leadership RolesMyster DangerNo ratings yet

- J Nepr 2020 102963Document9 pagesJ Nepr 2020 102963cruzchristophertangaNo ratings yet

- Job SatisfactionDocument38 pagesJob SatisfactionBishwajitMazumderNo ratings yet

- Relationship of Nursing Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes and Work Environments With Completeness in The Decree of Clinical Pathway by Nurses in Ernaldi Bahar Hospital South Sumatera Province 2018Document4 pagesRelationship of Nursing Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes and Work Environments With Completeness in The Decree of Clinical Pathway by Nurses in Ernaldi Bahar Hospital South Sumatera Province 2018International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Development and Job Satisfaction Among NursesDocument8 pagesHuman Resource Development and Job Satisfaction Among NursesIJPHSNo ratings yet

- Nursing EducationDocument6 pagesNursing EducationnishthaNo ratings yet

- Foreign: Minerva Pingue-Raguini, Ala'A Abujaber and Nada Gomma (2020)Document3 pagesForeign: Minerva Pingue-Raguini, Ala'A Abujaber and Nada Gomma (2020)Ezra CabanillaNo ratings yet

- Ojsadmin, 275Document5 pagesOjsadmin, 275Nathalie ConchaNo ratings yet

- Effects of The Elearning Approach On Knowledge TraDocument12 pagesEffects of The Elearning Approach On Knowledge TraagrovissiontzNo ratings yet

- Final Paper RheaDocument25 pagesFinal Paper RheaNeweeJoonYowNo ratings yet

- Human Resources For HealthDocument8 pagesHuman Resources For Healthdenie_rpNo ratings yet

- Nursing Competency Standards in Primary Health Care - An IntegrativeDocument13 pagesNursing Competency Standards in Primary Health Care - An Integrativecarlos treichelNo ratings yet

- KB ICH (Anggrek 2)Document5 pagesKB ICH (Anggrek 2)AstridNo ratings yet

- Assignment ON Continuing EducationDocument6 pagesAssignment ON Continuing EducationDebashrita MisraNo ratings yet

- Correctional Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice, Third EditionFrom EverandCorrectional Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice, Third EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Nursing Leadership: Scope and Standards of Practice, 3rd editionFrom EverandNursing Leadership: Scope and Standards of Practice, 3rd editionNo ratings yet

- Comment On: Effects of Orthogeriatric Care Models On Outcomes of Hip Fracture Patients-A Systematic Review and Meta AnalysisDocument2 pagesComment On: Effects of Orthogeriatric Care Models On Outcomes of Hip Fracture Patients-A Systematic Review and Meta AnalysisnersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- SCR 35Document15 pagesSCR 35nersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- Impact of An Interprofessional Communication Course On Nursing, MedicalDocument10 pagesImpact of An Interprofessional Communication Course On Nursing, MedicalnersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Practice, and AssocDocument12 pagesKnowledge, Practice, and AssocnersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- Scient Direct 2Document7 pagesScient Direct 2nersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0260691722002015 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0260691722002015 MainnersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0020138313002970 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0020138313002970 MainnersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- Drug Information ResourcesDocument27 pagesDrug Information ResourcesMA Masum HossainNo ratings yet

- Helloyubo Com Chatbot Benefits of Using A Whatsapp Healthcare ChatbotDocument4 pagesHelloyubo Com Chatbot Benefits of Using A Whatsapp Healthcare ChatbotSubrahmanyeswari DeviNo ratings yet

- Acls RequestDocument2 pagesAcls Requestabujarrin kalbiNo ratings yet

- Neurologist Deborah Boland, D.O., MSPT, Named "Physician of The Year"Document3 pagesNeurologist Deborah Boland, D.O., MSPT, Named "Physician of The Year"PR.comNo ratings yet

- 2 Banas-Nograles v. Comelec - G.R. No. 246328, 10 September 2019Document15 pages2 Banas-Nograles v. Comelec - G.R. No. 246328, 10 September 2019Bee CGNo ratings yet

- ReportViewer3 CBCDocument1 pageReportViewer3 CBCMuhammad Munawar BuzdarNo ratings yet

- Empanelled Hospitals CGHSDocument107 pagesEmpanelled Hospitals CGHSankit.shrivastavaNo ratings yet

- ICN Daily Round ChecklistDocument1 pageICN Daily Round ChecklistrenuNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan ON Critical Thinking and Problem Solving.: Era College of NursingDocument7 pagesLesson Plan ON Critical Thinking and Problem Solving.: Era College of NursingAru VermaNo ratings yet

- Hand Hygiene Leaflet PDFDocument2 pagesHand Hygiene Leaflet PDFMuhammad DzulfikarNo ratings yet

- Apa AjaDocument129 pagesApa AjaRoyNo ratings yet

- Polyethylene Glycol For Constipation in Children Younger Than Eighteen Months OldDocument3 pagesPolyethylene Glycol For Constipation in Children Younger Than Eighteen Months OldJose SalazarNo ratings yet

- Integrated Health Information ProgrammeDocument76 pagesIntegrated Health Information Programmesandra fernandezNo ratings yet

- Ach067 Equip National Day Procedures CompletewebDocument168 pagesAch067 Equip National Day Procedures Completewebkamil EliaNo ratings yet

- Compton Academy 2023Document8 pagesCompton Academy 2023Sargunan SabNo ratings yet

- Article 05Document100 pagesArticle 05Abdulphatah Mohamed IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Innovative Use of Technology in BABINA DiagnosticsDocument9 pagesInnovative Use of Technology in BABINA DiagnosticsSukumar ThingomNo ratings yet

- Claim ReceiptDocument3 pagesClaim ReceiptsheerazaliNo ratings yet

- CHDC Hospital Quanti AnalysisDocument12 pagesCHDC Hospital Quanti Analysislloyd814No ratings yet

- ASSIGNMENT On Nursing ProgramDocument10 pagesASSIGNMENT On Nursing ProgramPriya100% (1)

- Music Intervention For Pain and AnxietyDocument37 pagesMusic Intervention For Pain and AnxietyVebryana RamadhaniaNo ratings yet

- Elevator Utilization and Emergency ProceduresDocument3 pagesElevator Utilization and Emergency ProceduresBudi YunantoNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Varmam and Thokkanam THDocument5 pagesEffectiveness of Varmam and Thokkanam THTam gdzie nauka spotyka się z magiąNo ratings yet

- AC - 06 - Surgery - SITA For RegistrarsDocument2 pagesAC - 06 - Surgery - SITA For RegistrarsNibras Sauqath Ali0% (1)

- Tamil Nadu Private Clinical Establishments (Regulation) Amendment Act, 2018.Document6 pagesTamil Nadu Private Clinical Establishments (Regulation) Amendment Act, 2018.ShivramNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics NFDN 2005 Assignment2Document2 pagesPediatrics NFDN 2005 Assignment2api-319232343No ratings yet

- Handicapped ChildrenDocument36 pagesHandicapped ChildrenAbdur RehmanNo ratings yet

1 SM

1 SM

Uploaded by

nersrosdianaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1 SM

1 SM

Uploaded by

nersrosdianaCopyright:

Available Formats

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 7(1), 2017, 24-34

Available Online at http://ejournal.undip.ac.id/index.php/medianers

Motivation among Indonesian Nurses in Pursuing Continuing

Professional Education and Its Relationship to Their

Competencies

Fitriany Suangga1, Cyruz P. Tuppal2

1Awal Bros Batam Health College, Riau Island, Indonesia

2 St. Paul University Philippines System, Philippines; Tutor, Ministry of Health,

Muscat, Sultanate of Oman

Correspondending Author: Cyruz P. Tuppal (drcyruztuppal@gmail.com)

ABSTRACT

Background: Nurses are required to maintain the standards of their practice through an

informed range of Continuing Professional Education (CPE). However, there is a

paucity of evidence exploring the relationship between motivation in pursuing CPE and

competency among Indonesian nurses.

Purpose: This descriptive correlational study describes the motivation among

Indonesian nurses in pursuing CPE and its relationship to their competency outcome

performance.

Methods: Ninety-three staff nurses were chosen by convenience sampling, informed

and gave consent for their voluntary participation in a selected hospital in Jakarta,

Indonesia. Before the data collection, the researchers sought ethical clearance from the

respective organizations. Eligible participants were those who have at least one-year

hospital experience, naturally born Indonesian, and completed a degree in nursing. Data

were collected using adapted, pilot-tested, translated, and validated sets of

questionnaires.

Results: The findings revealed that most of the nurses were 21–30 years old, married,

permanent employees with 1–3 years’ working experience and had earned a degree in

nursing. Indonesian nurses had moderate to high motivation in pursuing CPE and

exemplified a fair to very good level of competency outcome performance. Results also

indicated that among the motivation factors, expectancy was significantly associated

with critical thinking (r=0.259, p< 0.012).

Conclusion: Motivation among Indonesian nurses in pursuing CPE was at a moderate

to high level. As Indonesia emerges as a promising country, leaders need to increase the

motivation of nurses in their pursuit of CPE. Highly competent and well-prepared

nurses can facilitate a caring and healing environment for patients and contribute to the

overall performance of health-care organizations and society.

Keywords: Competency; Continuing Professional Education (CPE); motivation;

Indonesian nurses

Copyright © 2017, NMJN, p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-8799

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 7(1), 2017, 25

BACKGROUND

Hennessy, Hicks, Hilan, and Kawonal (2006) reported that “there is a serious shortfall

of qualified nurses in Indonesia, with an estimated 50 nurses per 100.000 of the

population” (p. 2). To address this issue, a focus on human resources for health must be

tackled specifically on the nurses’ expanding roles to meet the country’s vision toward

the development of a highly skilled and trained workforce. Indonesian nurses are

required to maintain the standards of their practice through a diverse and informed

range of continuing professional education (CPE). Nonetheless, there is a paucity of

evidence that has explored nurses’ motivation in pursuing CPE and its relationship to

their competency.

The CPE is a crucial indicator for patients who depend on the nurse’s up-to-date

knowledge and skills (Chong, Sellick, Francis, & Abdullah, 2011; Ni et al., 2014;

Nsemo, John, Etifit, Mgbekem, & Oyira, 2013; Pool, Poell, Berings, & ten Cate, 2015;

Pool, Poell, & ten Cate, 2013). Nurses who are motivated to do well in CPE gain more

knowledge and skills than less motivated nurses (Kemp & Baker, 2013; Marzuki,

Hassan, Wichaikhum, & Nantsupawat, 2012; Pool et al., 2013). Apparently, those

trained professionals and practitioners showed increased productivity, fewer

occupational accidents, a higher level of work satisfaction, and effective patient

outcomes.

Nurses become motivated to pursue CPE for various reasons. These reasons may be a

mandatory requirement for registration and renewal or a desire to improve the standards

of practice. Nurses are also motivated to experience new trends in nursing, increase

their knowledge, enhance skills, cultivate career satisfaction, and for promotion

(Brekelmans, Maassen, Poell, Weststrate, & Geurdes, 2016). As the nursing practice in

Indonesia continues to undergo radical changes and transformation, there is an urgent

need for professionals to provide safe, effective, efficient, equitable, patient-centered,

and quality health-care services (Hennessy et al., 2006). Nurses are the backbone of the

health-care delivery system and serve as the key players in sustained and quality care.

With this, organizations need to build a strong foundation of knowledge, skills, values,

and attitudes threaded through the provision of CPE for nurses.

The CPE also provides a door for many opportunities to advance in the profession.

Nurses who have achieved exemplary competence can be a medium of change. They

would further understand various factors affecting the profession and develop strategic

actions. Because the transition to professional practice is challenging, nurses need more

mastery and advancement of knowledge about the profession, practice, and future

priorities (Bindon, 2017). As explicated by Harper and Maloney (2017), nurses must

position themselves to display their credence as it affirms the profession’s worth. From

a qualitative study among perioperative nurses, the findings indicate that through CPE,

they gain acknowledgment from other professionals that contribute to their being

assertive (Tame, 2013). Nurses further build a strong collegial partnership between and

among members of the health-care team. As a result, it enhances a multidisciplinary

milieu of trust, respect, and power.

Copyright © 2017, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 7(1), 2017, 26

It has been mentioned that CPE contributes to the many facets of the nursing profession

but would only be realized with a positive culture, effective partnership, and supportive

learning environment. Hence, the motivation of nurses becomes important (Clark,

Draper, & Rogers, 2015). To make CPE effective, the design needs to address the

current practice, anchored in partnerships with the stakeholders, foster a community of

learning, and bring a significant impact to inform the practice (Clark et al., 2015).

Proven in many other countries, investment in CPE programs at multiple levels

contributes to the workforce development as evidenced by their skills and capabilities to

respond effectively to the demands of the public whom they serve.

The Republic of Indonesia Law No. 23 Concerning Health (Indonesia, 1992) states that

to implement quality health measures, the country needs to embrace the mandates to

carry out or perform health activities in accordance with the areas of expertise and status

of the relevant health authority. For this reason, more investment in the advancement of

nurses’ competence through CPE should be explored along with other factors that will

motivate them. In this juncture, the researchers explored the motivation among

Indonesian nurses in pursuing CPE and its relationships to their competency outcome

performance, with an end view of proposing a training design program that aims to

enhance the nurses’ knowledge, elevate the standard of service delivery, and determine

the essential competency required for a safe, effective, efficient, timely, and quality

patient care.

PURPOSE

This study described the motivation among nurses in pursuing CPE and its relationship

to their competency outcome performance.

METHODS

This study used a descriptive correlation research design that determined the

relationship between motivation in pursuing CPE and the competency outcome

performance among staff nurses in Indonesia. Prior to the data collection,

administrative, institutional, ethical clearance, and permission to conduct this study

were sought from the relevant organizations, including the hospital where data

collection was conducted. Selected participants were informed and gave consent for

their voluntary participation. Both rights to privacy and confidentiality were elicited

prior to the questionnaire distribution. Eligible participants were given an option that if

they want to discontinue their participation, they would be given their rights to self-

determination. Ninety-three staff nurses were chosen by convenience sampling in a

selected hospital in Jakarta, Indonesia. The nurses included in this study had at least

one-year hospital experience in their current workplace, naturally born Indonesian, and

had completed their nursing education.

The motivation of nurses was measured using a 30-item adapted questionnaire

consisting of three categories (expectancy, valence, and instrumentality) (Ayres, 2005).

The second questionnaire assessed the competency outcome performance using a 40-

item questionnaire based on the eight core indices adapted from the Competency

Outcome Performance Assessment (COPA) Model (Lenburg, 1999). Both

Copyright © 2017, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 7(1), 2017, 27

questionnaires were rated using a four-point Likert scale (1.00 = poor/not motivated, 2 =

fair/moderately motivated, 3.00 = very good/highly motivated). The questionnaires

were translated into Bahasa Indonesia and back-translated into English to ensure that the

meaning, content, and syntax did not change. Experts validated the two questionnaires,

and a pilot study was performed. The Cronbach alpha for the questionnaires revealed a

high reliability of 0.95 for the motivation and 0.98 for the competency. To measure the

relationships between nurses’ motivation and competency, Spearman’s rho was used.

RESULTS

Demographic profile of staff nurses

Table 1 shows that among the 93 participants, the highest percentage comes from the

age group of 21–30 years (76 or 81.7%), were married (50 or 53.8%), permanent

employees (61 or 65.6%), length of experience of 1–3 years (45 or 48.4%) and had a

Bachelor’s degree (87 or 93.5%).

Table 1. Demographic profile of staff nurses

Demographic Profile n (%)

Age

21-30 76 (81.7)

31-40 15 (16.1)

41-50 2 (2.2)

Marital Status

Single 43 (46.2)

Married 50 (53.8)

Employment Status

Contract 32 (34.4)

Permanent 61 (65.6)

Length of Clinical Experience

<1 15 (16.1)

1-3 45 (48.4)

4-6 20 (21.5)

>6 13 (14)

Educational Attainment

SPK 2 (2.2)

Diploma 4 (4.3)

Bachelor 87 (93.5)

Motivation among Indonesian Nurses

The motivation among nurses revealed a high level in pursuing continuing education

specifically on expectancy (2.64), instrumentality (2.44) and valence (2.29).

Table 2. Motivation among Indonesian nurses

Motivation Mean SD Interpretation

Expectancy 2.64 0.49 Highly Motivated

Instrumentality 2.44 0.62 Highly Motivated

Valence 2.29 0.68 Moderately Motivated

Copyright © 2017, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 7(1), 2017, 28

Competency outcome performance assessment among nurses

The findings showed that among the competency domains, nurses exemplified a high

level of critical thinking (2.73), human caring/relationship skills (2.67), and leadership

skills (2.66).

Table 3. Competency assessment domains among nurses

Domains Mean SD Interpretation

Assessment and Intervention Skills 2.37 0.45 Very Good

Communication Skills 2.36 0.49 Very good

Critical Thinking 2.73 0.45 Very Good

Human Caring/Relationship Skills 2.67 0.40 Very Good

Teaching Skills 2.54 0.52 Very Good

Management Skills 2.60 0.44 Very Good

Leadership Skills 2.66 0.39 Very Good

Knowledge Integration Skills 2.63 0.49 Very Good

The relationship between the motivation in pursuing CPE and nurses’

competencies

Among the competencies displayed by staff nurses, only critical thinking was

significantly related to motivation, specifically on expectancy (r = 0.259, p< 0.05).

Table 4. Relationship between motivation and competency domains

Expectancy Instrumentality Valence

Competency Domains

rs Sig. rs Sig. rs Sig.

Assessment and Integration 0.141 0.169 0.04 0.721 0.08 0.473

Communication 0.141 0.177 0.05 0.641 0.02 0.847

Critical Thinking 0.259 0.012* 0.02 0.845 0.04 0.726

Human Caring/Relationship skills 0.052 0.621 -0.01 0.939 0.13 0.213

Teaching Skills -0.02 0.882 -0.04 0.731 -0.08 0.459

Management Skills 0.127 0.227 -0.09 0.367 -0.08 0.425

Leadership Skills -0.039 0.71 0.07 0.478 0.08 0.403

Knowledge integration Skills -0.018 0.857 -0.09 0.387 -0.2 0.059

Note: rs=Spearman rho, * p < 0.05

DISCUSSION

As the country currently experiences and faces a critical challenge in the supply of

human resources for health, Indonesian nurses should strengthen and enhance their

knowledge, skills, and attitudes through CPE (Kurniati, Rosskam, Afzal, Suryowinoto,

& Mukti, 2015). Indonesia needs to review and develop a policy on a health-care

workforce with government support, commitment, and multisectoral approach (Kurniati

et al., 2015). A mismatch between production and demand, as well as the quality of the

workforce, maldistribution, and compensation has been a challenge as well. From the

report of the World Health Organization in 2006, Indonesia belongs to the 57 countries

experiencing a shortage of human resources for health (Kurniati et al., 2015). Through a

multistakeholder coordination, the process of identifying the problems and main areas

of concern specifically on human resources has been established. Through this

approach, it strengthens the quality production of resources for health, including human

Copyright © 2017, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 7(1), 2017, 29

resources. Furthermore, it fosters scaling up of the educational preparation and

continuing professional development of doctors, nurses, and other allied health

practitioners and professionals.

In the Philippines, for example, the Philippine Regulation Commission (PRC)

Resolution No. 38 Series of 1995 defined CPE as the “inculcation, assimilation, and

acquisition of knowledge, skills, proficiency, and ethical and moral values after the

initial registration of a professional that raise and enhance one’s technical skills and

professional competence”(Loretto, 1996, p. 79 cited in Joseph, 2011). CPE is an

essential instrument for personal growth, professional development, advancement in the

profession and for the well-being of the patients (Kovner, Brewer, Katigbak, Djukic, &

Fatehi, 2012; Pool, Poell, Berings, & ten Cate, 2016). Participation in CPE is directly

related to effective and efficient nursing practice because it enhances the clinical

competence of nurses and other allied health practitioners (James & Francis, 2011).

Pool et al. (2015) stated that continuing education is crucial for the safety of the patients

or clients who depend on the nurse’s up-to-date knowledge and skills related to patient

care management.

Nurses have different motivations in pursuing CPE. The findings of this study indicate

that Indonesian nurses have a high level of motivation along with the three domains,

namely expectancy, instrumentality, and valence. Participants highly rated the

expectancy area which explains how nurses perceived the likelihood that their effort

would help them to attain excellence in the clinical area. Expectancy involves an

understanding that an increased effort leads to high performance, but the individual

must have previous experience, necessary machinery, tools, and opportunity to perform.

On nurse’s instrumentality, it involves whether a successful performance will lead to the

desired outcome. Vroom (1999) explained that if the instrumentality is high, the

individual will be more highly motivated. He further posited that if the expectancy is

low, it will not produce the desired outcome, and motivation will be less. The results

also indicate that nurses displayed motivation at a moderate level regarding valence.

This finding implies that staff nurses give moderate value to the outcomes that they will

receive after attending a CPE program. Thus, nurses require an avenue that will

facilitate them to apply what they have learned from the CPE. Despite nurses having a

strong belief that knowledge, skills, and attitude are acquired through a continuing

education program, Burrow, Mairs, Pusey, Bradshaw, and Keady (2016) suggested that

the management should understand that motivation among nurses may also include

personal and professional drivers, influence of workplace, funding, and availability of

CPE.

In the Netherlands, 1226 registered nurses were sampled to identify the factors related

to nurses undertaking CPE. Using a survey approach, Brekelmans et al. (2016) found

that if nurses consider a CPE activity as relevant for their practice, the more likely they

are to have the motivation to pursue it. This factor has been identified as a critical area

to consider in the development of CPE programs. Brekelmans et al. (2016) surmised

that nurses pursue CPE as a mandatory requirement, but some are involved due to

participation in research, professional, and organizational development.

Copyright © 2017, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 7(1), 2017, 30

Pool et al. (2016) found from a qualitative and exploratory design using a semi-

structured interview that nurses’ engagement to continuing professional development is

essential for better performance, skills, and competence enhancement. Pool et al. (2016)

identified nine types of motives or purposes among nurses in pursuit of CPE, which

include to (a) deepen the knowledge, enhance career development, comply with the

requirement, supplement gaps in prior education, (b) increase self-esteem, (c) relief

from clinical routines, (d) expand professional linkages and networks, (e) improve

health care, and (f) increase competence in the present job.

Schumacher and Risco (2017) opined that competency is a cumulative set of the desired

knowledge, skills, and behaviors through assimilation, acquisition, and embodiment.

Competency enables one effectively to perform the activities of a given occupation or

function to the standards expected in employment. Nurses’ skills can be evaluated in

multimodal approaches. This study used the COPA (Lenburg, 1999), which consisted of

eight domains.

The COPA model provides an intensive process development of competence in nursing

practice (Lenburg, 1999 cited in Klein & Fowles, 2009). In this present study, nurses

had fair to good results in the competency evaluation. The critical thinking was

identified as the highest domain. This finding implies that nurses contribute to the

decision-making and analytical capabilities of their patients’ needs and concerns.

Furthermore, nurses are expected to be competent in all domains of nursing practice that

should be prioritized by any health-care organization (Klein & Fowles, 2009). With this,

the nursing organizations should be mandated to have a periodic competency

assessment in conjunction with the diverse background of nurses (Franklin & Melville,

2015).

Critical thinking is “the ability to apply higher-order cognitive skills (conceptualization,

analysis, evaluation) and the disposition to be deliberate about thinking (being open-

minded or intellectually honest) leading to action that is logical and appropriate”(Papp

et al. 2014, p. 716 cited in Von Colln-Appling & Giuliano, 2017). However, critical

thinking only becomes apparent when nursing graduates start to immerse as entry level

nurses in the hospitals (Klein & Fowles, 2009). Therefore, the practice should

illuminate clinical strategies to enhance critical thinking abilities. With such abilities,

nurses achieve an optimal performance and contribute to the better patient care and

quality outcomes (Kaddoura, Van Dyke, & Yang, 2017; Risling, 2017).

Motivation on expectancy was found to be significantly associated with critical thinking

skills among Indonesian nurses. This finding implies that nurses are motivated to attend

CPE in the hope that their skills will be strengthened, improved, and nurtured as they

care for diverse patients. The results also suggest that nurses should also develop the

foresight to anticipate either the actual or potential needs of their patients.

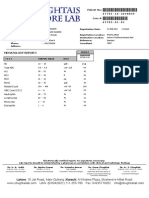

The researchers proposed a Training Program Design (Figure 1) that highlights the

nurses’ motivation and competency performance aiming to develop a holistic and

integrative professional development. Undeniably, nurses serve as the backbone of the

health-care delivery system, which should be provided with the highest level of support

Copyright © 2017, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 7(1), 2017, 31

from the organizations and the government. Nurses help their patients to do what they

would do for themselves if they could. Nurses provide a holistic person-centered care

with tenderness, love, and care. Nurses always find a way to see if the patient is

breathing correctly, visiting many times to see if they are all well-nourished, in comfort

and happy, and assist in all possible ways.

Figure 1. Training program design for nurses’ continuing professional education

Despite nurses gaining a cadre of skills and competencies, human caring and

interpersonal skills are also vital aspects. The proposed training program is not only

intended for skills acquisition but also grounded in caring perspectives that remain as a

fundamental concept in the practice of nursing. Through caring—the language of

nursing—nurses can provide holistic care to their patients, families, and communities.

This proposed training design needs a collaborative partnership between service and

education to foster open communication in a dynamic and supportive learning

environment. Furthermore, the CPE developers should identify both facilitators and

inhibitors to sustain motivation among nurses. These facilitators and inhibitors are

pivotal to making the program design more doable, feasible, and practical. Facilitators

include but are not limited to the commitment of the management, alignment of

personal and professional development to the organizational goals, readiness among

nurses, appropriate course design, delivery, and evaluation (Clark et al., 2015). The

inhibitors may include but are not limited to inflexibility, inadequate organization

support to learning, different cultures, and various generational workforce needs (Clark

et al., 2015).

Copyright © 2017, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 7(1), 2017, 32

When synergism remains at the core of the nursing workforce, there is no doubt that the

profession will continue to light its lamp to shed an enticing movement toward the

improvement of patient care, provision of patient safety, and sustenance of a healthy

working environment.

CONCLUSION

This study revealed that the motivation among Indonesian nurses in pursuing CPE was

at a moderate to high level. The result of this study also indicated that among the

motivation factors, expectancy was significantly associated with critical thinking.

Indeed, Indonesia is an emerging country where nursing leaders are in a joint effort to

elevate the morale of the discipline as well as the competency of nurses at multiple

levels. Through their support in motivating many nurses in various settings, they are

also helping the country to achieve its strategic vision in producing a highly skilled

workforce. In addition, there is a need for straight forward policies to leverage

workforce performance and productivity through transformative human resources

training and development plans.

REFERENCES

Ayres, H. W. (2005). Factors related to motivation to learn and motivation to transfer

learning in a nursing population. (Doctor of Education), North Carolina State

University, United States of America. Available from ProQuest Dissertations

and Theses.

Bindon, S. L. (2017). The next new grad. Journal for Nurses in Professional

Development, 33(2), 55.

Brekelmans, G., Maassen, S., Poell, R., Weststrate, J., & Geurdes, E. (2016). Factors

influencing nurse participation in continuing professional development

activities: Survey results from the Netherlands. Nurse Education Today, 40, 13-

19. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.01.028

Burrow, S., Mairs, H., Pusey, H., Bradshaw, T., & Keady, J. (2016). Continuing

professional education: Motivations and experiences of health and social care

professional’s part-time study in higher education. A qualitative literature

review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 63, 139-145.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.08.011

Chong, M., Sellick, K., Francis, K., & Abdullah, K. (2011). What influences Malaysian

nurses to participate in continuing professional education activities? Asian

Nursing Research, 5(1), 38-47. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1976-

1317(11)60012-1

Clark, E., Draper, J., & Rogers, J. (2015). Illuminating the process: Enhancing the

impact of continuing professional education on practice. Nurse Education

Today, 35(2), 388-394. doi:http://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2014.10.014

Franklin, N., & Melville, P. (2015). Competency assessment tools: An exploration of

the pedagogical issues facing competency assessment for nurses in the clinical

environment. Collegian, 22(1), 25-31.

doi:http://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2013.10.005

Copyright © 2017, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 7(1), 2017, 33

Harper, M. G., & Maloney, P. (2017). Our role as advocate for the nursing professional

development specialty. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 33(2),

99-101.

Hennessy, D., Hicks, C., Hilan, A., & Kawonal, Y. (2006). The training and

development needs of nurses in Indonesia. Human Resources for Health, 4(1),

10. doi:http://10.1186/1478-4491-4-10

Indonesia. (1992). Republic of Indonesia Law No. 23 Concerning Health. Retrieved

from http://www.ilo.org/

James, A., & Francis, K. (2011). Mandatory continuing professional education: What is

the prognosis? Collegian, 18(3), 131-136.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2011.03.001

Joseph, P. V. (2011). Continuing professional education. In H. R. Feldman (Ed.),

Nursing Leadership. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Kaddoura, M. A., Van Dyke, O., & Yang, Q. (2017). Correlation between critical

thinking skills and national council licensure examination for registered nurses

success in accelerated bachelor nursing students. Teaching and Learning in

Nursing, 12(1), 3-7. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2016.08.004

Kemp, S., & Baker, M. (2013). Continuing professional development – reflections from

nursing and education. Nurse Education in Practice, 13(6), 541-545.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2013.04.009

Klein, C. J., & Fowles, E. R. (2009). An investigation of nursing competence and the

competency outcomes performance assessment curricular approach: Senior

students' self-reported perceptions. Journal of Professional Nursing, 25(2), 109-

121. doi:http://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2008.08.006

Kovner, C., Brewer, C., Katigbak, C., Djukic, M., & Fatehi, F. (2012). Charting the

course for nurses' achievement of higher education levels. Journal of

Professional Nursing, 28(6), 333-343.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2012.04.021

Kurniati, A., Rosskam, E., Afzal, M. M., Suryowinoto, T. B., & Mukti, A. G. (2015).

Strengthening Indonesia's health workforce through partnerships. Public Health,

129(9), 1138-1149. doi:http://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2015.04.012

Lenburg, C. (1999). The framework, concepts, and methods of the Competency

Outcomes and Performance Assessment (COPA) model. Online Journal of

Issues in Nursing. Retrieved from

http://www.nursingworld.org/ojin/topic10/tpc10_2.htm

Marzuki, M. A., Hassan, H., Wichaikhum, O., & Nantsupawat, R. (2012). Continuing

nursing education: Best practice initiative in nursing practice environment.

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 60, 450-455.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.405

Ni, C., Hua, Y., Shao, P., Wallen, G., Xu, S., & Li, L. (2014). Continuing education

among Chinese nurses: A general hospital-based study. Nurse Education Today,

34(4), 592-597. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.07.013

Nsemo, A., John, M., Etifit, R., Mgbekem, M., & Oyira, E. (2013). Clinical nurses'

perception of continuing professional education as a tool for quality service

delivery in public hospitals Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria. Nurse

Education in Practice, 13(4), 328-334.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2013.04.005

Copyright © 2017, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 7(1), 2017, 34

Pool, I., Poell, R., Berings, M., & ten Cate, O. (2015). Strategies for continuing

professional development among younger, middle-aged, and older nurses: A

biographical approach. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(5), 939-

950. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.02.004

Pool, I., Poell, R., Berings, M., & ten Cate, O. (2016). Motives and activities for

continuing professional development: An exploration of their relationships by

integrating literature and interview data. Nurse Education Today, 38, 22-28.

doi:http://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.01.004

Pool, I., Poell, R., & ten Cate, O. (2013). Nurses’ and managers’ perceptions of

continuing professional development for older and younger nurses: A focus

group study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(1), 34-43.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.08.009

Risling, T. (2017). Educating the nurses of 2025: Technology trends of the next decade.

Nurse Education in Practice, 22, 89-92.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2016.12.007

Schumacher, G., & Risco, K. (2017). Nurse practitioner program curriculum

development: A Competency-based approach. The Journal for Nurse

Practitioners, 13(2), 75-81. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2016.10.014

Tame, S. L. (2013). The effect of continuing professional education on perioperative

nurses’ relationships with medical staff: Findings from a qualitative study.

Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(4), 817-827. doi:10.1111/j.1365-

2648.2012.06065.x

Von Colln-Appling, C., & Giuliano, D. (2017). A concept analysis of critical thinking:

A guide for nurse educators. Nurse Education Today, 49, 106-109.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.11.007

Vroom, V. (1999). Work and motivation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Copyright © 2017, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

You might also like

- Developing Competencies of NurDocument10 pagesDeveloping Competencies of NurnersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- Theory of Swift Even FlowDocument6 pagesTheory of Swift Even Flowjacinta100% (1)

- Vasan Eye Care Hospital ProjectDocument86 pagesVasan Eye Care Hospital Projectkavilankutty100% (1)

- 7s PresentationDocument54 pages7s PresentationMish Lim67% (3)

- GHS - An Introduction To ADF On-Base Healthcare Delivery - 15092016Document9 pagesGHS - An Introduction To ADF On-Base Healthcare Delivery - 15092016jim STAMNo ratings yet

- Quality of Nursing Care Practices Among Select Hospitals in Bataan EditedDocument23 pagesQuality of Nursing Care Practices Among Select Hospitals in Bataan EditedZonllam Aryl DialorNo ratings yet

- Statement of The ProblemDocument2 pagesStatement of The ProblemCHARLESNo ratings yet

- Structured Mentoring StrategiesDocument31 pagesStructured Mentoring Strategiesrandy gallegoNo ratings yet

- Nurses Education and Motivation Towards Nursing DocumentationDocument5 pagesNurses Education and Motivation Towards Nursing DocumentationEdwardoNo ratings yet

- Journal of Global BiosciencesDocument25 pagesJournal of Global BiosciencesSamah IshtiehNo ratings yet

- Nursing Doc - EditedDocument5 pagesNursing Doc - EditedMORRIS ANUNDANo ratings yet

- What Influences Malaysian Nurses To Participate in Continuing Professional Education Activities?Document10 pagesWhat Influences Malaysian Nurses To Participate in Continuing Professional Education Activities?EHashim Al MunawarahNo ratings yet

- Teaching Competency of Nursing Educators and Caring Attitude of Nursing StudentsDocument26 pagesTeaching Competency of Nursing Educators and Caring Attitude of Nursing StudentsJaine NicolleNo ratings yet

- Transformational and Transactional Leadership Styles of Nurse Managers and Job Satisfaction Among Filipino Nurses: A Pilot StudyDocument14 pagesTransformational and Transactional Leadership Styles of Nurse Managers and Job Satisfaction Among Filipino Nurses: A Pilot StudyDanyPhysicsNo ratings yet

- Continuing Education in Nursing - EditedDocument7 pagesContinuing Education in Nursing - EditedOnkwani DavidNo ratings yet

- Van Patten 2019Document6 pagesVan Patten 2019Amrinder RandhawaNo ratings yet

- 169-Article Text-809-1-10-20220501Document9 pages169-Article Text-809-1-10-20220501Dwi NopriyantoNo ratings yet

- BrownDocument13 pagesBrownapi-255084253No ratings yet

- Nurse Managers' Responsive Coaching To Facilitate Staff Nurses' Clinical Skills Development in Public Tertiary HospitalDocument10 pagesNurse Managers' Responsive Coaching To Facilitate Staff Nurses' Clinical Skills Development in Public Tertiary Hospitalvan royeNo ratings yet

- Nursing 1Document5 pagesNursing 1Ray NamuNo ratings yet

- Clinical ReasoningDocument7 pagesClinical Reasoninglyndon_baker_10% (1)

- Journal Pone 0226804Document18 pagesJournal Pone 0226804Biman MondalNo ratings yet

- Health Notions, Volume 1 Issue 4 (October-December 2017) ISSN 2580-4936Document7 pagesHealth Notions, Volume 1 Issue 4 (October-December 2017) ISSN 2580-4936Muhammad DzikrullohNo ratings yet

- Performanta JobuluiDocument11 pagesPerformanta JobuluiBaciu AlessandroNo ratings yet

- Tugas Bahasa Inggris - Temu 1 - KLP 8 - A12 BDocument8 pagesTugas Bahasa Inggris - Temu 1 - KLP 8 - A12 BErina NiluhNo ratings yet

- The Influence of The IOM - SubmitDocument9 pagesThe Influence of The IOM - SubmitKerry-Ann Brissett-SmellieNo ratings yet

- Presentation BaderDocument15 pagesPresentation BaderBader AljarboaNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Pengetahuan Terhadap Kompetensi Mahasiwa Profesi Ners Dalam Penerapan Evidence Based PracticeDocument6 pagesHubungan Pengetahuan Terhadap Kompetensi Mahasiwa Profesi Ners Dalam Penerapan Evidence Based PracticeIwan AgustiNo ratings yet

- Influence of Emotional Intelligence, Communication, and Organizational Commitment On Nursing Productivity Among Korean NursesDocument8 pagesInfluence of Emotional Intelligence, Communication, and Organizational Commitment On Nursing Productivity Among Korean NursesSyifa AiniNo ratings yet

- Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice: A C B C B CDocument6 pagesJournal of Interprofessional Education & Practice: A C B C B CReny ParembangNo ratings yet

- Ffectiveness of An Evidence-Based Practice: E Educational Intervention Among School NursesDocument10 pagesFfectiveness of An Evidence-Based Practice: E Educational Intervention Among School NursesJV BernNo ratings yet

- Clinical Leadership 2022 PDFDocument16 pagesClinical Leadership 2022 PDFMaria Erika NuñezNo ratings yet

- Admsci 07 00017Document13 pagesAdmsci 07 00017SriMathi Kasi Malini ArmugamNo ratings yet

- Retaining Novice Nurses in A Healthcare OrganizationDocument8 pagesRetaining Novice Nurses in A Healthcare OrganizationRay NamuNo ratings yet

- Dedicated EducationalDocument5 pagesDedicated EducationalNovin YetianiNo ratings yet

- Assessment On The Level of Proficiency of ClinicalDocument7 pagesAssessment On The Level of Proficiency of ClinicalWinnie AriolaNo ratings yet

- Week 7 Discussion - Nursing LeadershipDocument6 pagesWeek 7 Discussion - Nursing LeadershipFranklin Mung'athia BettNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic Communication Through Simulation PDFDocument5 pagesTherapeutic Communication Through Simulation PDFNicole GadrinabNo ratings yet

- Plagerism FileDocument25 pagesPlagerism FileIqra AsimNo ratings yet

- (Comm) ResearchDocument2 pages(Comm) ResearchEngella BumagatNo ratings yet

- Nin Artikel IlmiahDocument11 pagesNin Artikel IlmiahNindhita SetyaningrumNo ratings yet

- Nurse's Foci of Commitment Model To Decrease Turnover IntentionDocument10 pagesNurse's Foci of Commitment Model To Decrease Turnover IntentionIJPHSNo ratings yet

- The Improvement of Student Competency in A Clinical Study in Indonesia: What Factors Played An Important Role?Document8 pagesThe Improvement of Student Competency in A Clinical Study in Indonesia: What Factors Played An Important Role?Ferry EfendiNo ratings yet

- Patient Assessment Responses in Nursing Practice To Enhance Patient Safety: A Systematic ReviewDocument2 pagesPatient Assessment Responses in Nursing Practice To Enhance Patient Safety: A Systematic ReviewFeaona MoiraNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Advanced Practice Nursing Education: Challenges and StrategiesDocument9 pagesReview Article: Advanced Practice Nursing Education: Challenges and StrategiesluNo ratings yet

- GondarDocument8 pagesGondarYared wolduNo ratings yet

- Mountain Province State Polytechnic College: School of Healthcare EducationDocument6 pagesMountain Province State Polytechnic College: School of Healthcare EducationMaller Chop's Pong-etNo ratings yet

- Sample Sample: Running Head: Evidence-Based Nursing Practice 1Document7 pagesSample Sample: Running Head: Evidence-Based Nursing Practice 1Henoke ManNo ratings yet

- Impacts of Iom On Nursing Practice, Education and Leadership RolesDocument5 pagesImpacts of Iom On Nursing Practice, Education and Leadership RolesMyster DangerNo ratings yet

- J Nepr 2020 102963Document9 pagesJ Nepr 2020 102963cruzchristophertangaNo ratings yet

- Job SatisfactionDocument38 pagesJob SatisfactionBishwajitMazumderNo ratings yet

- Relationship of Nursing Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes and Work Environments With Completeness in The Decree of Clinical Pathway by Nurses in Ernaldi Bahar Hospital South Sumatera Province 2018Document4 pagesRelationship of Nursing Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes and Work Environments With Completeness in The Decree of Clinical Pathway by Nurses in Ernaldi Bahar Hospital South Sumatera Province 2018International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Development and Job Satisfaction Among NursesDocument8 pagesHuman Resource Development and Job Satisfaction Among NursesIJPHSNo ratings yet

- Nursing EducationDocument6 pagesNursing EducationnishthaNo ratings yet

- Foreign: Minerva Pingue-Raguini, Ala'A Abujaber and Nada Gomma (2020)Document3 pagesForeign: Minerva Pingue-Raguini, Ala'A Abujaber and Nada Gomma (2020)Ezra CabanillaNo ratings yet

- Ojsadmin, 275Document5 pagesOjsadmin, 275Nathalie ConchaNo ratings yet

- Effects of The Elearning Approach On Knowledge TraDocument12 pagesEffects of The Elearning Approach On Knowledge TraagrovissiontzNo ratings yet

- Final Paper RheaDocument25 pagesFinal Paper RheaNeweeJoonYowNo ratings yet

- Human Resources For HealthDocument8 pagesHuman Resources For Healthdenie_rpNo ratings yet

- Nursing Competency Standards in Primary Health Care - An IntegrativeDocument13 pagesNursing Competency Standards in Primary Health Care - An Integrativecarlos treichelNo ratings yet

- KB ICH (Anggrek 2)Document5 pagesKB ICH (Anggrek 2)AstridNo ratings yet

- Assignment ON Continuing EducationDocument6 pagesAssignment ON Continuing EducationDebashrita MisraNo ratings yet

- Correctional Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice, Third EditionFrom EverandCorrectional Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice, Third EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Nursing Leadership: Scope and Standards of Practice, 3rd editionFrom EverandNursing Leadership: Scope and Standards of Practice, 3rd editionNo ratings yet

- Comment On: Effects of Orthogeriatric Care Models On Outcomes of Hip Fracture Patients-A Systematic Review and Meta AnalysisDocument2 pagesComment On: Effects of Orthogeriatric Care Models On Outcomes of Hip Fracture Patients-A Systematic Review and Meta AnalysisnersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- SCR 35Document15 pagesSCR 35nersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- Impact of An Interprofessional Communication Course On Nursing, MedicalDocument10 pagesImpact of An Interprofessional Communication Course On Nursing, MedicalnersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Practice, and AssocDocument12 pagesKnowledge, Practice, and AssocnersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- Scient Direct 2Document7 pagesScient Direct 2nersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0260691722002015 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0260691722002015 MainnersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0020138313002970 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0020138313002970 MainnersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- Drug Information ResourcesDocument27 pagesDrug Information ResourcesMA Masum HossainNo ratings yet

- Helloyubo Com Chatbot Benefits of Using A Whatsapp Healthcare ChatbotDocument4 pagesHelloyubo Com Chatbot Benefits of Using A Whatsapp Healthcare ChatbotSubrahmanyeswari DeviNo ratings yet

- Acls RequestDocument2 pagesAcls Requestabujarrin kalbiNo ratings yet

- Neurologist Deborah Boland, D.O., MSPT, Named "Physician of The Year"Document3 pagesNeurologist Deborah Boland, D.O., MSPT, Named "Physician of The Year"PR.comNo ratings yet

- 2 Banas-Nograles v. Comelec - G.R. No. 246328, 10 September 2019Document15 pages2 Banas-Nograles v. Comelec - G.R. No. 246328, 10 September 2019Bee CGNo ratings yet

- ReportViewer3 CBCDocument1 pageReportViewer3 CBCMuhammad Munawar BuzdarNo ratings yet

- Empanelled Hospitals CGHSDocument107 pagesEmpanelled Hospitals CGHSankit.shrivastavaNo ratings yet

- ICN Daily Round ChecklistDocument1 pageICN Daily Round ChecklistrenuNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan ON Critical Thinking and Problem Solving.: Era College of NursingDocument7 pagesLesson Plan ON Critical Thinking and Problem Solving.: Era College of NursingAru VermaNo ratings yet

- Hand Hygiene Leaflet PDFDocument2 pagesHand Hygiene Leaflet PDFMuhammad DzulfikarNo ratings yet

- Apa AjaDocument129 pagesApa AjaRoyNo ratings yet

- Polyethylene Glycol For Constipation in Children Younger Than Eighteen Months OldDocument3 pagesPolyethylene Glycol For Constipation in Children Younger Than Eighteen Months OldJose SalazarNo ratings yet

- Integrated Health Information ProgrammeDocument76 pagesIntegrated Health Information Programmesandra fernandezNo ratings yet

- Ach067 Equip National Day Procedures CompletewebDocument168 pagesAch067 Equip National Day Procedures Completewebkamil EliaNo ratings yet

- Compton Academy 2023Document8 pagesCompton Academy 2023Sargunan SabNo ratings yet

- Article 05Document100 pagesArticle 05Abdulphatah Mohamed IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Innovative Use of Technology in BABINA DiagnosticsDocument9 pagesInnovative Use of Technology in BABINA DiagnosticsSukumar ThingomNo ratings yet

- Claim ReceiptDocument3 pagesClaim ReceiptsheerazaliNo ratings yet

- CHDC Hospital Quanti AnalysisDocument12 pagesCHDC Hospital Quanti Analysislloyd814No ratings yet

- ASSIGNMENT On Nursing ProgramDocument10 pagesASSIGNMENT On Nursing ProgramPriya100% (1)

- Music Intervention For Pain and AnxietyDocument37 pagesMusic Intervention For Pain and AnxietyVebryana RamadhaniaNo ratings yet

- Elevator Utilization and Emergency ProceduresDocument3 pagesElevator Utilization and Emergency ProceduresBudi YunantoNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Varmam and Thokkanam THDocument5 pagesEffectiveness of Varmam and Thokkanam THTam gdzie nauka spotyka się z magiąNo ratings yet

- AC - 06 - Surgery - SITA For RegistrarsDocument2 pagesAC - 06 - Surgery - SITA For RegistrarsNibras Sauqath Ali0% (1)

- Tamil Nadu Private Clinical Establishments (Regulation) Amendment Act, 2018.Document6 pagesTamil Nadu Private Clinical Establishments (Regulation) Amendment Act, 2018.ShivramNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics NFDN 2005 Assignment2Document2 pagesPediatrics NFDN 2005 Assignment2api-319232343No ratings yet

- Handicapped ChildrenDocument36 pagesHandicapped ChildrenAbdur RehmanNo ratings yet