Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Martin MayaSuperstates 1995

Martin MayaSuperstates 1995

Uploaded by

CHrisCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Lego Super Mario Barcodes Catalog by Maxim Chernenko: M U S I CDocument2 pagesLego Super Mario Barcodes Catalog by Maxim Chernenko: M U S I Cburcu ertok100% (3)

- Archipelagi Aesthetics PDFDocument6 pagesArchipelagi Aesthetics PDFCipta HadiNo ratings yet

- Names and Relationships of The Royal Family ofDocument14 pagesNames and Relationships of The Royal Family ofÉmän HâmzáNo ratings yet

- Yolanda Lastra de Suárez Las Áreas Dialectales Del Náhuatl Moderno. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México 1986Document1 pageYolanda Lastra de Suárez Las Áreas Dialectales Del Náhuatl Moderno. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México 1986Szymo GrudzkiNo ratings yet

- Poetry, Power, Protest - Reimagining Muslim Nationhood in Northern PakistanDocument13 pagesPoetry, Power, Protest - Reimagining Muslim Nationhood in Northern PakistanbtNo ratings yet

- A Hiatus in The Cutting of Buddhist Caves in The Western DeccanDocument16 pagesA Hiatus in The Cutting of Buddhist Caves in The Western DeccanAtul BhosekarNo ratings yet

- The Mayan Civilization (Quartet)Document7 pagesThe Mayan Civilization (Quartet)Theodoreith 95No ratings yet

- Bedford, A Door Ajar - National Borders and The Character of Islam in PakistanDocument16 pagesBedford, A Door Ajar - National Borders and The Character of Islam in PakistanbtNo ratings yet

- Ge이 ogical Hist。 ry: (i) Current-bedding (i Graded-beddingDocument17 pagesGe이 ogical Hist。 ry: (i) Current-bedding (i Graded-beddingTuvshuu DriNo ratings yet

- The Mayan Civilization (Quartet)Document7 pagesThe Mayan Civilization (Quartet)Theodoreith 95No ratings yet

- Dissertation Has Heen Microfilmed Exactly As Received: University Microfilms. Inc., Ann Arbor, MichiganDocument306 pagesDissertation Has Heen Microfilmed Exactly As Received: University Microfilms. Inc., Ann Arbor, MichiganXian Francis ManalonNo ratings yet

- Articulo NatureDocument2 pagesArticulo Natureivan.quijano.aranibarNo ratings yet

- Frieze - The Cult of The Virgin and Gothic SculptureDocument20 pagesFrieze - The Cult of The Virgin and Gothic Sculpturepablo pucheNo ratings yet

- Turpin (1990) Rock Art and Hunter-Gatherer ArchaeologyDocument20 pagesTurpin (1990) Rock Art and Hunter-Gatherer ArchaeologyRob BotelloNo ratings yet

- We Are All Moors Ending Centuries of Crusades Against Muslims and Other Minorities (Anouar Majid) (Z-Library)Document252 pagesWe Are All Moors Ending Centuries of Crusades Against Muslims and Other Minorities (Anouar Majid) (Z-Library)httd2gjqt2No ratings yet

- A Glance at Selected Philippine Political Caricature inDocument4 pagesA Glance at Selected Philippine Political Caricature inCHARLEMAGNE S. ATAATNo ratings yet

- Ancient Cities in BurmaDocument9 pagesAncient Cities in BurmaKyaw MaungNo ratings yet

- Introduction: Feminist State Theory: Ashwini TambeDocument3 pagesIntroduction: Feminist State Theory: Ashwini TambeBilan Andrian PutraNo ratings yet

- Culture, The Media, and The "Ideological Effect"Document13 pagesCulture, The Media, and The "Ideological Effect"Qhusnul AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Costanzo - 2008 - Giedeon As Guide (+ Inleiding The Baroque in Architectural Culture)Document13 pagesCostanzo - 2008 - Giedeon As Guide (+ Inleiding The Baroque in Architectural Culture)charlotteNo ratings yet

- Bayou HoustonDocument1 pageBayou HoustonJessica McBride100% (1)

- Comment: Winston Churchill's Essay On Alien Life FoundDocument3 pagesComment: Winston Churchill's Essay On Alien Life FoundTales NogueiraNo ratings yet

- Miniature Cattle: The Social Context of Balkan Animal FigurinesDocument17 pagesMiniature Cattle: The Social Context of Balkan Animal FigurinesDimitrij MlekuzNo ratings yet

- The River Valley: Civilizations IIDocument6 pagesThe River Valley: Civilizations IIKusum Sonu SharmaNo ratings yet

- HOC VOLUME3 Part1 Chapter35Document35 pagesHOC VOLUME3 Part1 Chapter35Jason SpencerNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of Femistic Values in Pakistan: This Study Resource Was Shared ViaDocument8 pagesInterpretation of Femistic Values in Pakistan: This Study Resource Was Shared ViaHaris MunirNo ratings yet

- Eponyms Have No Place in 21st-Century Biological NomenclatureDocument4 pagesEponyms Have No Place in 21st-Century Biological NomenclaturemaxeleryNo ratings yet

- Ideas That Shaped BuildingsDocument424 pagesIdeas That Shaped BuildingsAlex CardosoNo ratings yet

- 2016.05 Test 42Document69 pages2016.05 Test 42KEYA SANGHVINo ratings yet

- ETS Research Bulletin Series - June 1960 - Saunders - A FACTOR ANALYSIS OF THE INFORMATION AND ARITHMETIC ITEMS OF THE PDFDocument24 pagesETS Research Bulletin Series - June 1960 - Saunders - A FACTOR ANALYSIS OF THE INFORMATION AND ARITHMETIC ITEMS OF THE PDFAhamad GoncalvesNo ratings yet

- FEBRUARY - Essay - Middle Ages - The Renaissance 8th 2022Document4 pagesFEBRUARY - Essay - Middle Ages - The Renaissance 8th 2022DIEGO FERNANDO BARRIOS DIAZNo ratings yet

- Tradition Book - Verbena (Revised)Document106 pagesTradition Book - Verbena (Revised)Jesse Loftus80% (5)

- 2020 Jan 17 - ScienceDocument148 pages2020 Jan 17 - ScienceBalaramanNo ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of Cultivation Theory: Original ArticleDocument53 pagesA Critical Analysis of Cultivation Theory: Original ArticleHidya AwalyaNo ratings yet

- Three Books About Economics Nature ReviewsDocument3 pagesThree Books About Economics Nature ReviewslaurakaiohNo ratings yet

- Aharoni 1972Document18 pagesAharoni 1972Abram Louies HannaNo ratings yet

- LLLLLLFF: Priiet0N1IDocument8 pagesLLLLLLFF: Priiet0N1IRITMO SOPORTENo ratings yet

- Managing Urbanisation in PakistanDocument10 pagesManaging Urbanisation in PakistanHawaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- The Russia Anxiety and How History Can Resolve It 1St Edition Edition Mark B Smith Full ChapterDocument67 pagesThe Russia Anxiety and How History Can Resolve It 1St Edition Edition Mark B Smith Full Chaptereileen.laigo375100% (5)

- This Study Resource Was: The Bundestag. Virginia General Assembly UnderDocument2 pagesThis Study Resource Was: The Bundestag. Virginia General Assembly UnderConAir161057No ratings yet

- Nature aDNA Archaeology Vs Genetics PDFDocument4 pagesNature aDNA Archaeology Vs Genetics PDFMonika MilosavljevicNo ratings yet

- Vivifica v2 - Trumpet in BB 2Document2 pagesVivifica v2 - Trumpet in BB 2Wandry Morais LustosaNo ratings yet

- MEC19 - The Druadan ForestDocument2 pagesMEC19 - The Druadan Forestole hansenNo ratings yet

- Paper One 2017 November MarkschemeDocument27 pagesPaper One 2017 November Markschemefatimagrimaldi09No ratings yet

- Small Scale Cult StatuesDocument12 pagesSmall Scale Cult StatuesOscar OscarNo ratings yet

- The Russia Anxiety and How History Can Resolve It 1St Edition Edition Mark B Smith Full Chapter PDFDocument69 pagesThe Russia Anxiety and How History Can Resolve It 1St Edition Edition Mark B Smith Full Chapter PDFmadjouyossue100% (3)

- Tectonothermal Evolution in The Core of An Arcuate Fold and Thrust Belt: The South-Eastern Sector of The Cantabrian Zone (Variscan Belt, Northwestern Spain)Document20 pagesTectonothermal Evolution in The Core of An Arcuate Fold and Thrust Belt: The South-Eastern Sector of The Cantabrian Zone (Variscan Belt, Northwestern Spain)Fernando BastidaNo ratings yet

- Robert Harpole Constable of CarlowDocument13 pagesRobert Harpole Constable of CarlowJohn HayesNo ratings yet

- Encyclopedia of World Religions - Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Zen, Hinduism, Prehistoric, & Primitive ReligionsDocument254 pagesEncyclopedia of World Religions - Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Zen, Hinduism, Prehistoric, & Primitive ReligionsDenys Malta100% (1)

- Star Wars Galaxy MapDocument1 pageStar Wars Galaxy MapVictor Stoinescu100% (1)

- The Carolingian Revival of Early Christian Architecture - Krautheimer - 1942Document50 pagesThe Carolingian Revival of Early Christian Architecture - Krautheimer - 1942Eszter CzuczorNo ratings yet

- MayanBones Nature 0219 PDFDocument4 pagesMayanBones Nature 0219 PDFAnthony CerlaNo ratings yet

- GL25 010Document1 pageGL25 010franckmartin86No ratings yet

- MEC69 - The Ghost of FramsburgDocument2 pagesMEC69 - The Ghost of Framsburgole hansenNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 49.37.34.184 On Fri, 16 Jun 2023 16:13:41 +00:00Document28 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 49.37.34.184 On Fri, 16 Jun 2023 16:13:41 +00:00Wrishi BiswasNo ratings yet

- Mexico City by NightDocument115 pagesMexico City by Nightonslowmo100% (3)

- Understanding Popular Culture - Fiske, John - (2nd Impr.) ., Cambridge, Ma, 1989 - Boston Unwin Hyman - 9780044454380 - Anna's ArchiveDocument228 pagesUnderstanding Popular Culture - Fiske, John - (2nd Impr.) ., Cambridge, Ma, 1989 - Boston Unwin Hyman - 9780044454380 - Anna's ArchiveAnia RychlińskaNo ratings yet

- The Trick is to Keep Breathing: Covid 19 Stories From African and North American WritersFrom EverandThe Trick is to Keep Breathing: Covid 19 Stories From African and North American WritersNo ratings yet

- Aztec-period Ceramic Distribution and Exchange Systems (Final NSF Report)Document254 pagesAztec-period Ceramic Distribution and Exchange Systems (Final NSF Report)CHrisNo ratings yet

- Ehlers Anthro ResponsibilityDocument16 pagesEhlers Anthro ResponsibilityCHrisNo ratings yet

- Chinchilla Class StruggleDocument23 pagesChinchilla Class StruggleCHrisNo ratings yet

- Smithcarol 95Document28 pagesSmithcarol 95CHrisNo ratings yet

- Webre Waterand ColonialismDocument29 pagesWebre Waterand ColonialismCHrisNo ratings yet

- Smith 1990Document35 pagesSmith 1990CHrisNo ratings yet

- Lovell 83 LandDocument18 pagesLovell 83 LandCHrisNo ratings yet

- Mangelsdorf ARCHAEOLOGICALEVIDENCEDIFFUSION 1956Document44 pagesMangelsdorf ARCHAEOLOGICALEVIDENCEDIFFUSION 1956CHrisNo ratings yet

- Linda GreenFearDocument31 pagesLinda GreenFearCHrisNo ratings yet

- ContentServer 2Document8 pagesContentServer 2CHrisNo ratings yet

- ContentServer 3Document5 pagesContentServer 3CHrisNo ratings yet

- Susanne JonasDocument7 pagesSusanne JonasCHrisNo ratings yet

- Lovell 88Document34 pagesLovell 88CHrisNo ratings yet

- ContentServer 1Document2 pagesContentServer 1CHrisNo ratings yet

- Lovelland Lutz 1994Document9 pagesLovelland Lutz 1994CHrisNo ratings yet

- ContentServer 2Document3 pagesContentServer 2CHrisNo ratings yet

- Lovell Etal 84Document20 pagesLovell Etal 84CHrisNo ratings yet

- Frank DaltonsTheoreticalIssues 1970Document6 pagesFrank DaltonsTheoreticalIssues 1970CHrisNo ratings yet

- ContentServer 4Document3 pagesContentServer 4CHrisNo ratings yet

- Berreman AnthropologyAliveSocial 1968Document7 pagesBerreman AnthropologyAliveSocial 1968CHrisNo ratings yet

- Origin, Domestication, and SpreadDocument6 pagesOrigin, Domestication, and SpreadCHrisNo ratings yet

- The Poverty of SustainabilityDocument7 pagesThe Poverty of SustainabilityCHrisNo ratings yet

- Mexican AxolotlDocument2 pagesMexican AxolotlCHrisNo ratings yet

- Wylie 92Document22 pagesWylie 92CHrisNo ratings yet

- Browder LimitsExtractivism 1992Document10 pagesBrowder LimitsExtractivism 1992CHrisNo ratings yet

- McClung AM 26 - 2 - 2015Document16 pagesMcClung AM 26 - 2 - 2015CHrisNo ratings yet

- Brondizio Et Al 2009 Connectivity and The Governance of Multilevel Social Ecological Systems The Role of Social CapitalDocument29 pagesBrondizio Et Al 2009 Connectivity and The Governance of Multilevel Social Ecological Systems The Role of Social CapitalCHrisNo ratings yet

- Dragon Magazine 186Document124 pagesDragon Magazine 186CHris100% (2)

- Wiessner 06Document28 pagesWiessner 06CHrisNo ratings yet

- ZacatalDocument30 pagesZacatalCHrisNo ratings yet

- Assignment Cycle 10Document3 pagesAssignment Cycle 10CelestialNo ratings yet

- Aztec Brainpop NotesDocument1 pageAztec Brainpop Notesapi-253899620No ratings yet

- CH 6 Maya Chavin Part 2Document20 pagesCH 6 Maya Chavin Part 2api-483536703No ratings yet

- Xiii.: Landa Cuz Luumil LuumilDocument21 pagesXiii.: Landa Cuz Luumil LuumilRussell HartillNo ratings yet

- Beniamino Volta and Geoffrey E BraswellDocument49 pagesBeniamino Volta and Geoffrey E BraswellAnna OwczarekNo ratings yet

- Mayan CivilizationDocument2 pagesMayan Civilizationlipanacathlynjoy22No ratings yet

- Chichimec: The Came WasDocument38 pagesChichimec: The Came WasRussell HartillNo ratings yet

- The Myth of "La Malinche": SourceDocument2 pagesThe Myth of "La Malinche": SourcejoannaNo ratings yet

- "Afro-Latina" by Elizabeth AcevedoDocument3 pages"Afro-Latina" by Elizabeth Acevedo2028: Francesca Sardi GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Carta XantoloDocument4 pagesCarta XantoloClaudia AguillónNo ratings yet

- Native American Art Before 1300 CeDocument60 pagesNative American Art Before 1300 Ceragunath palaniswamyNo ratings yet

- The Pre Columbian CivilizationsDocument2 pagesThe Pre Columbian CivilizationsRafa C HortalNo ratings yet

- IS01 AztecDocument14 pagesIS01 AztecNur HidayahNo ratings yet

- Lords of The NightDocument2 pagesLords of The NightAsdf JmasewqNo ratings yet

- Human Sacrifice in Aztec CultureDocument4 pagesHuman Sacrifice in Aztec CulturemariafranciscaNo ratings yet

- MESOAMERICANDocument4 pagesMESOAMERICANGi ChoiNo ratings yet

- The Decapitation Ritual and The AncientDocument12 pagesThe Decapitation Ritual and The AncientB'alam DavidNo ratings yet

- XincaDocument4 pagesXincaRobJeanNo ratings yet

- The AztecsDocument5 pagesThe AztecsAng RNo ratings yet

- Honduran Ethnic HWDocument11 pagesHonduran Ethnic HWvicoso031No ratings yet

- Mitologia AztekówDocument54 pagesMitologia AztekówAnna OwczarekNo ratings yet

- History of The Charro DaysDocument3 pagesHistory of The Charro DaysCristian Damir Martínez VegaNo ratings yet

- The Tale of Lady Winikhaab Ajaw (Marc Zender)Document16 pagesThe Tale of Lady Winikhaab Ajaw (Marc Zender)Muzen DerNo ratings yet

- Aztecs Mayas Incas Chart Answer KeyDocument1 pageAztecs Mayas Incas Chart Answer KeyNathan TakeshiNo ratings yet

- MesoamericaDocument3 pagesMesoamericaJolina AynganNo ratings yet

- An Illustrated Dictionary of The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and The Maya PDFDocument216 pagesAn Illustrated Dictionary of The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and The Maya PDFArielRibeiroTolentino100% (1)

- Mayan Timeline PowerPointDocument1 pageMayan Timeline PowerPointChe LeeNo ratings yet

- Mayan Hieroglyph Presentation 2021 UpdateDocument50 pagesMayan Hieroglyph Presentation 2021 UpdateGary V Stephenson100% (1)

- Diccionario Otomi de Neve y Molina 1767 - FullDocument107 pagesDiccionario Otomi de Neve y Molina 1767 - FulltlakuilokalliNo ratings yet

Martin MayaSuperstates 1995

Martin MayaSuperstates 1995

Uploaded by

CHrisOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Martin MayaSuperstates 1995

Martin MayaSuperstates 1995

Uploaded by

CHrisCopyright:

Available Formats

Maya Superstates

Author(s): Simon Martin and Nikolai Grube

Source: Archaeology , November/December 1995, Vol. 48, No. 6 (November/December

1995), pp. 41-46

Published by: Archaeological Institute of America

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41771163

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Archaeological Institute of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to Archaeology

This content downloaded from

52.43.93.60 on Mon, 11 Dec 2023 21:52:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maya Superstates

How a few powerful kingdoms vied

for control of the Maya Lowlands during the

Classic period (A.D. 300-900)

3

s

I

a

s

ì

D

O

o

P

2,

O

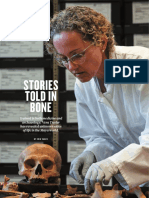

Haya warriors parade a captive for sacrifice on this Late Classic period polychrome vase from the Petén region of Guatemala.

hair, while those from Palenque in Chiapas, Mexico,

esplendent in jaguar pelts, quetzal plumes,

■ m and helmets fashioned in the form of fan- were based on a highly stylized bone. Berlin proposed

tastic beasts, Maya warriors set out for

that the main signs identified individual cities, their rul-

I battle on a day often ordained byingthe

dynasties, or the territories they controlled. Among

^k^position of Venus in the predawn sky.Berlin's

Led more interesting discoveries were four emblem

by rulers dressed as gods, they sought to capture and - those of Copán, Tikal, Palenque, and an

glyphs

sacrifice their enemies in a reenactment of sacred unknown city represented by a snake's head - grouped

myths. According to many scholars, such religious together in an inscription on Stela A at Copán in west-

beliefs motivated all Maya warfare. Our epigraphic ern Honduras. Following Berlin, both Thomas Barthel

of the University of Tübingen and Joyce Marcus of the

research suggests that far too little attention has been

paid to more pragmatic goals, that wars were also University of Michigan proposed that these cities were

fought to conquer and control rival kingdoms. the capitals of four large and powerful states, each

aligned with one of the cardinal directions. In search of

The first clue to understanding Classic period politi-

cal organization came in 1958 when Mayanist Heinrich archaeological data bearing on this interpretation,

Berlin identified what he called emblem glyphs. Found Richard E.W. Adams of the University of Texas, San

in inscriptions throughout the southern Maya Lowlands, Antonio, examined the relative size of cities throughout

the Maya region. Although many of the smaller cities

these glyphs consist of a main sign, usually placed in the

lower right, attached to two smaller elements. Berlin had their own emblem glyphs, both Marcus and Adams

noticed that while the smaller elements remained rela- concluded that they were not independent political enti-

tively constant, the main sign changed from site to site.ties but constituent provinces of larger regional states.

Emblem glyphs from Tikal in the Petén region of north- More recent archaeological research has failed to

ern Guatemala had a main sign representing a knot turn of up compelling evidence to support this view. More-

By Simon Martin and Nikolai Grube

November/December 1995 41

This content downloaded from

52.43.93.60 on Mon, 11 Dec 2023 21:52:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ties ruled by kings who were ritually

important but politically feeble. This view

is compatible with the interpretation of

Maya warfare as a small-scale, predomi-

nantly ritual activity. Surviving inscrip-

tions appear to support this notion since

they rarely if ever record conquests in

which one state absorbs another - more

evidence, it would seem, that Maya king-

doms were too weak to engage in territor-

ial expansion.

Yet such reconstructions have always

failed to explain why some cities are

vasdy larger than others. Were such dis-

parate units really equals? The idea that

central authority within larger kingdoms

was ineffectual is undermined by the scale

I of their public works - massive pyramids,

defensive earthworks miles in length, and

great networks of internal roadways -

which would have required centralized

planning and the control of substantial

manpower. But perhaps the most com-

pelling evidence for a higher level of polit-

ical organization comes from new

information we have uncovered within a

body of glyphic data that has often been

overlooked.

Political relationships between subordi-

nates and their superiors within individual

kingdoms were expressed by the use of

possessive terms. Thus sahal , a rank or

office held by key lieutenants of a king,

could be transformed into the possessive

form u-sahal , "the sahal of." The glyphs

also tell us that the same dominant-subor-

I dinant relationship existed between kings

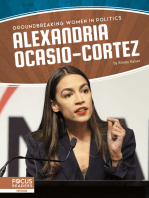

Pyramid, top , dominates the main plaza of Calakmul, the largest known Classic of different states, where the highest rank

Maya city. A lintel within Tikal Temple I, above, records that city's victory over of ahaw , "lord or ruler," comes into play.

rival Calakmul on August 5, A.D. 695. By adding the prefix y, ahaw becomes y-

ahaw , "the lord of," in effect "his vassal."

over, breakthroughs in the decipherment of hieroglyphs Further evidence for hierarchy between states is

during the past decade have greatly expanded our found in passages recording the accession of kings.

understanding of the Maya political world, suggesting Some of these statements contain a secondary phrase

quite a different interpretation. We now know that giving the name and emblem glyph of a foreign ruler.

emblem glyphs are titles of Maya kings describing each This phrase is introduced by a verb clause that epigra-

as the k'ul ahaw or "divine lord" of a kingdom whose phers have long glossed as "under the auspices of,"

name appears as the main sign of the glyph. By chart- though we now believe that it should be translated as u-

ing the distribution of emblem glyphs, Peter Mathews of kahiy , literally "it was done by him."

the University of Calgary has created a map of the If we combine the appearance of the y-ahaw and u-

Lowlands during the Classic period, revealing some 40 kahiy phrases with Classic period texts documenting

separate kingdoms. other forms of diplomatic exchange such as royal visits,

Taken by themselves, emblem glyphs demonstrate gift-giving, joint ritual activity, and marriage, we find

that all Maya rulers laid claim to an identical political that hierarchical contacts are part of relationships span-

rank, regardless of the size or population of their cities. ning several generations. Some kingdoms are consis-

This decentralized picture has led many scholars to tently more dominant than others and seem to be

believe that Maya kingdoms, even major ones such as manipulating the affairs of weaker ones. This analysis is

Tikal and Palenque, were fundamentally unstable enti- supported by inscriptions describing conflicts. Wars are

42 Archaeology

This content downloaded from

52.43.93.60 on Mon, 11 Dec 2023 21:52:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

g

0

1

lhap of the Maya Lowlands during the Classic period ( ca . A.D. 300-900) shows principal kingdoms and their identifying glyphs.

November/December 1995 43

This content downloaded from

52.43.93.60 on Mon, 11 Dec 2023 21:52:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

u

o

3

S

z

E pigraphic evidence of political influence comes from a key phrase u-kahiy, literally "it was done by him." The phrase

is found in inscriptions recording the accession of local rulers. This passage tells us that a Cancuén king " was seated

into rulership" by the doing of a king of Calakmul.

only rarely recorded between states that usually closely

share tied to Tikal, while persistent relations with Uax-

political ties, and politically allied kingdoms tend to suggest that this kingdom was also associated with

actún

share the same adversaries. Together such patterns Tikal.

sug- Evidence that Tikal's Early Classic influence

gest that there were groupings of states during the extended

Late well beyond the Petén comes from inscriptions

on Stela

Classic period (ca. A.D. 600-900). As the y-ahaw and u- 6 and Altar 21 at Caracol in Belize, which

kahiy phrases indicate, kingdoms within such groupsrecord

did the accession of the Caracol king Y-ahawte 3 Iiinich

in 553 under the patronage of a Tikal ruler. Within a

not share power equally, tending rather to fall under the

influence of a few especially powerful states. Whofew years, however, the relationship between these two

were

these superstates? kingdoms had disintegrated. Altar 21 records conflict

Because of their size and the richness of their archi- between the two, possibly an attack on Caracol in 556,

tecture, cities such as Palenque, Copán, and the High- and a defeat of Tikal at the hands of another kingdom,

land site of Toniná have long been seen as dominant whose name is now illegible, in 562.

forces in their regions. Along the banks of the Usumac- No dated monuments were erected at Tikal during

inta River, which separates Mexico and Guatemala, the the next 130 years, but inscriptions from other sites in

political situation appears to have been more compli-the region tell us that Tikal was diplomatically isolated

cated. There, the iconographie and hieroglyphic record and at war with every one of its major neighbors - with-

suggests that Piedras Negras held a number of otherout exception, all either allies or vassals of the kingdom

states in somewhat unruly submission, including for of a Calakmul.

time its upstream neighbor, Yaxchilán. Inscriptions Discovered in 1931 deep in the rainforest of southern

throughout the area, however, contain references toCampeche, Mexico, Calakmul has been one of the most

larger cities in the Petén, where the most populous and remote and least visited of all Maya sites. Excavations

influential kingdoms were located. by William J. Folan, of the Universidad Autonoma de

Tikal emerged as a great center during the Early Campeche, and more recently by Ramón Carrasco, of

Classic period (ca. A.D. 300-600). Inscriptions from this the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, have

time, however, concentrate on chronological andrevealed a great metropolis. With more than 6,000

genealogical information, and tell us little about political structures it is the largest Classic Maya city yet

affairs. T-ahaw relationships with Bejucal and later

recorded. Impressive even in Preclassic times, its core is

dominated by the largest concentration of palace-type

Motul de San José indicate that nearby kingdoms were

44 " Archaeology

This content downloaded from

52.43.93.60 on Mon, 11 Dec 2023 21:52:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

0

I

1

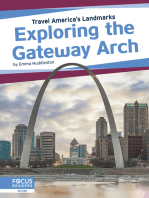

Calakmul's dominance of the Maya Lowlands during the Classic period was deduced from inscriptions recording forms of diplomat-

ic exchange between the site and nearby kingdoms. In this diagram black lines indicate a role in the accession of local kings ; blue ,

royal visits and other forms of diplomatic exchange; green , marital alliances and other ties; and red , references to armed conflict.

Dashed lines represent less certain relationships.

buildings in the Maya area, and is surrounded by a sub- ning in 693. They had ties with Caracol and Dos Pilas

stantial system of artificial reservoirs. Though its monu- and formed marital alliances with El Perú, Yaxchilán,

ments are badly eroded, it has 115 stelae, more than and Naachtún. They were also involved in rituals asso-

any other Maya site. Because of the poor preservation ciated with the designation of heirs at Dos Pilas - rela-

of so many monuments it has been extremely difficult to tives of the Tikal royal family - and probably Yaxchilán.

identify Calakmul's emblem glyph. Inscriptions uncov- There are signs that even the regional power Piedras

ered in the past two years, however, seem to confirm its Negras was not beyond Calakmul's influence, and one

association with the enigmatic snake-head glyph, a pro- especially difficult phrase dated 514 may describe anjy-

posal first put forward by Joyce Marcus in the early ahaw relationship between these states.

1970s. By the latter part of the seventh century, Calakmul

Calakmul first comes to prominence in the glyphic was the most powerful kingdom in the Maya Lowlands

record at the close of the Early Classic period, when in and the hub of an extensive network of affiliated and

A.D. 546 a ruler of Naranjo acceded to the throne "by vassal states. Despite its preeminence it was unable to

the doing of' a Calakmul king. This relationship, how- subdue its great rival Tikal, whose new king, Hasaw

ever, had clearly fallen apart by 631, when Caracol Ka'an ICawil , was soon to strike a crucial blow. Accord-

joined Calakmul to defeat Naranjo. Calakmul also ing to an inscription on a lintel in Tikal Temple I, Tikal

attacked Palenque twice, once in 599 and again in defeated Calakmul on August 5, 695, and probably cap-

611 - campaign treks of some 150 miles. Much of tured and killed its king, the great Jaguar Paw. Tikal

Calakmul's political maneuvering seems to have been went on to wage successful wars against two of Calak-

directed against Tikal, which it attacked in 657. Its mul's closest associates, El Perú in 743 and Naranjo the

influence over the Lowlands is further attested by its following year. As if in celebration of these triumphs,

involvement in the accession of two rulers from the dis- Tikal embarked on a century-long building program,

tant kingdom of Cancuén in 656 and 677 and two kingsproducing most of the major architecture seen at the

at El Perú (dates unknown). From y-ahaw expressions,site today.

we know that Calakmul rulers were overlords to Malah Despite Tikal's rejuvenation, the days of superstates

Ka'an ICawil , Ruler 1 of Dos Pilas, around 648, and and to large political groupings were numbered. Diplo-

his grandson Smoking Squirrel, king of Naranjo, begin- matic exchange between the largest centers all but dis-

November/December 1995 45

This content downloaded from

52.43.93.60 on Mon, 11 Dec 2023 21:52:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

l

í

appears from the writ en record by the mid-eighth cen-

tury. Significantly, the decline of these networks marked

the first sign of a wider political breakdown, as previ-

ously silent cities began to claim their own royal dynas-

ties and warfare intensified. Within a century or so

political disintegration and mounting environmental

stres - overpopulation, diminishing resources, and possi-

bly drought - had triggered the col apse of Clas ic Maya

civilization in the southern Lowlands.

The picture that is emerging is neither one of a cen-

tralized administration of regional states nor one of a

political vacuum populated by weak ones. Instead it

would appear that a few powerful kingdoms held lesser

ones in their sway, a system not unlike others seen

throughout ancient Mesoamerica. Maya kingdoms never

0 achieved the degree of centralization of the fifteenth-

1 0

century Aztec Empire, but their structure and political

strategies offer some interesting parallels. The Aztec

Empire was a loose confederation of subjugated king-

1

3

doms and smaller empires. Its conquests were not con-

solidated by military occupation or administered from

ã the capital Tenochtitlán; defeated local lords were usu-

0 ally restored to their offices and allowed to rule their

(d states without further hindrance. Their successors were

S

often sanctioned by the Aztec emperor in ceremonies

s

that invite comparison with the u-kahiy events of the

1 Classic Maya. The major consequences of Aztec con-

0 quest were economic, in the form of tribute payments,

í

and political, in the transformation of local leaders into

vassals of the emperor. Once their military prowess had

been proved, the Aztecs were often able to intimidate

other states into acquiescence without further use of

o

1 force. We suspect that the Classic Maya conformed to a

o

similar pattern - a complex environment of overlords

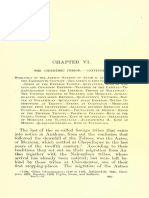

T he victorious Tikal ruler Hasaw Ka' an K'awil is enthroned and vassals, kinship ties and obligations, where the

on a litter with a giant jaguar effigy in this depiction on a strong came to dominate the weak. ■

wooden lintel found in Tikal Temple I. The highlighted pas-

sage records armed conflict with Calakmul on August 5, A.D. Simon Martin is epigrapher for the Proyecto Arqueológico de

695, and the "bringing down " ofthat city's king Jaguar Paw. la Biosfera de Calakmul , INAH, Mexico , and, an honorary

research fellow of the Institute of Archaeology, University College ,

London. Nikolai Grube is an anthropologist at the University

of Bonn and epigrapher for the Caracol Project , Belize , and

Proyecto Taxhá , IDEAH, Guatemala.

46 Archaeology

This content downloaded from

52.43.93.60 on Mon, 11 Dec 2023 21:52:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Lego Super Mario Barcodes Catalog by Maxim Chernenko: M U S I CDocument2 pagesLego Super Mario Barcodes Catalog by Maxim Chernenko: M U S I Cburcu ertok100% (3)

- Archipelagi Aesthetics PDFDocument6 pagesArchipelagi Aesthetics PDFCipta HadiNo ratings yet

- Names and Relationships of The Royal Family ofDocument14 pagesNames and Relationships of The Royal Family ofÉmän HâmzáNo ratings yet

- Yolanda Lastra de Suárez Las Áreas Dialectales Del Náhuatl Moderno. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México 1986Document1 pageYolanda Lastra de Suárez Las Áreas Dialectales Del Náhuatl Moderno. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México 1986Szymo GrudzkiNo ratings yet

- Poetry, Power, Protest - Reimagining Muslim Nationhood in Northern PakistanDocument13 pagesPoetry, Power, Protest - Reimagining Muslim Nationhood in Northern PakistanbtNo ratings yet

- A Hiatus in The Cutting of Buddhist Caves in The Western DeccanDocument16 pagesA Hiatus in The Cutting of Buddhist Caves in The Western DeccanAtul BhosekarNo ratings yet

- The Mayan Civilization (Quartet)Document7 pagesThe Mayan Civilization (Quartet)Theodoreith 95No ratings yet

- Bedford, A Door Ajar - National Borders and The Character of Islam in PakistanDocument16 pagesBedford, A Door Ajar - National Borders and The Character of Islam in PakistanbtNo ratings yet

- Ge이 ogical Hist。 ry: (i) Current-bedding (i Graded-beddingDocument17 pagesGe이 ogical Hist。 ry: (i) Current-bedding (i Graded-beddingTuvshuu DriNo ratings yet

- The Mayan Civilization (Quartet)Document7 pagesThe Mayan Civilization (Quartet)Theodoreith 95No ratings yet

- Dissertation Has Heen Microfilmed Exactly As Received: University Microfilms. Inc., Ann Arbor, MichiganDocument306 pagesDissertation Has Heen Microfilmed Exactly As Received: University Microfilms. Inc., Ann Arbor, MichiganXian Francis ManalonNo ratings yet

- Articulo NatureDocument2 pagesArticulo Natureivan.quijano.aranibarNo ratings yet

- Frieze - The Cult of The Virgin and Gothic SculptureDocument20 pagesFrieze - The Cult of The Virgin and Gothic Sculpturepablo pucheNo ratings yet

- Turpin (1990) Rock Art and Hunter-Gatherer ArchaeologyDocument20 pagesTurpin (1990) Rock Art and Hunter-Gatherer ArchaeologyRob BotelloNo ratings yet

- We Are All Moors Ending Centuries of Crusades Against Muslims and Other Minorities (Anouar Majid) (Z-Library)Document252 pagesWe Are All Moors Ending Centuries of Crusades Against Muslims and Other Minorities (Anouar Majid) (Z-Library)httd2gjqt2No ratings yet

- A Glance at Selected Philippine Political Caricature inDocument4 pagesA Glance at Selected Philippine Political Caricature inCHARLEMAGNE S. ATAATNo ratings yet

- Ancient Cities in BurmaDocument9 pagesAncient Cities in BurmaKyaw MaungNo ratings yet

- Introduction: Feminist State Theory: Ashwini TambeDocument3 pagesIntroduction: Feminist State Theory: Ashwini TambeBilan Andrian PutraNo ratings yet

- Culture, The Media, and The "Ideological Effect"Document13 pagesCulture, The Media, and The "Ideological Effect"Qhusnul AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Costanzo - 2008 - Giedeon As Guide (+ Inleiding The Baroque in Architectural Culture)Document13 pagesCostanzo - 2008 - Giedeon As Guide (+ Inleiding The Baroque in Architectural Culture)charlotteNo ratings yet

- Bayou HoustonDocument1 pageBayou HoustonJessica McBride100% (1)

- Comment: Winston Churchill's Essay On Alien Life FoundDocument3 pagesComment: Winston Churchill's Essay On Alien Life FoundTales NogueiraNo ratings yet

- Miniature Cattle: The Social Context of Balkan Animal FigurinesDocument17 pagesMiniature Cattle: The Social Context of Balkan Animal FigurinesDimitrij MlekuzNo ratings yet

- The River Valley: Civilizations IIDocument6 pagesThe River Valley: Civilizations IIKusum Sonu SharmaNo ratings yet

- HOC VOLUME3 Part1 Chapter35Document35 pagesHOC VOLUME3 Part1 Chapter35Jason SpencerNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of Femistic Values in Pakistan: This Study Resource Was Shared ViaDocument8 pagesInterpretation of Femistic Values in Pakistan: This Study Resource Was Shared ViaHaris MunirNo ratings yet

- Eponyms Have No Place in 21st-Century Biological NomenclatureDocument4 pagesEponyms Have No Place in 21st-Century Biological NomenclaturemaxeleryNo ratings yet

- Ideas That Shaped BuildingsDocument424 pagesIdeas That Shaped BuildingsAlex CardosoNo ratings yet

- 2016.05 Test 42Document69 pages2016.05 Test 42KEYA SANGHVINo ratings yet

- ETS Research Bulletin Series - June 1960 - Saunders - A FACTOR ANALYSIS OF THE INFORMATION AND ARITHMETIC ITEMS OF THE PDFDocument24 pagesETS Research Bulletin Series - June 1960 - Saunders - A FACTOR ANALYSIS OF THE INFORMATION AND ARITHMETIC ITEMS OF THE PDFAhamad GoncalvesNo ratings yet

- FEBRUARY - Essay - Middle Ages - The Renaissance 8th 2022Document4 pagesFEBRUARY - Essay - Middle Ages - The Renaissance 8th 2022DIEGO FERNANDO BARRIOS DIAZNo ratings yet

- Tradition Book - Verbena (Revised)Document106 pagesTradition Book - Verbena (Revised)Jesse Loftus80% (5)

- 2020 Jan 17 - ScienceDocument148 pages2020 Jan 17 - ScienceBalaramanNo ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of Cultivation Theory: Original ArticleDocument53 pagesA Critical Analysis of Cultivation Theory: Original ArticleHidya AwalyaNo ratings yet

- Three Books About Economics Nature ReviewsDocument3 pagesThree Books About Economics Nature ReviewslaurakaiohNo ratings yet

- Aharoni 1972Document18 pagesAharoni 1972Abram Louies HannaNo ratings yet

- LLLLLLFF: Priiet0N1IDocument8 pagesLLLLLLFF: Priiet0N1IRITMO SOPORTENo ratings yet

- Managing Urbanisation in PakistanDocument10 pagesManaging Urbanisation in PakistanHawaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- The Russia Anxiety and How History Can Resolve It 1St Edition Edition Mark B Smith Full ChapterDocument67 pagesThe Russia Anxiety and How History Can Resolve It 1St Edition Edition Mark B Smith Full Chaptereileen.laigo375100% (5)

- This Study Resource Was: The Bundestag. Virginia General Assembly UnderDocument2 pagesThis Study Resource Was: The Bundestag. Virginia General Assembly UnderConAir161057No ratings yet

- Nature aDNA Archaeology Vs Genetics PDFDocument4 pagesNature aDNA Archaeology Vs Genetics PDFMonika MilosavljevicNo ratings yet

- Vivifica v2 - Trumpet in BB 2Document2 pagesVivifica v2 - Trumpet in BB 2Wandry Morais LustosaNo ratings yet

- MEC19 - The Druadan ForestDocument2 pagesMEC19 - The Druadan Forestole hansenNo ratings yet

- Paper One 2017 November MarkschemeDocument27 pagesPaper One 2017 November Markschemefatimagrimaldi09No ratings yet

- Small Scale Cult StatuesDocument12 pagesSmall Scale Cult StatuesOscar OscarNo ratings yet

- The Russia Anxiety and How History Can Resolve It 1St Edition Edition Mark B Smith Full Chapter PDFDocument69 pagesThe Russia Anxiety and How History Can Resolve It 1St Edition Edition Mark B Smith Full Chapter PDFmadjouyossue100% (3)

- Tectonothermal Evolution in The Core of An Arcuate Fold and Thrust Belt: The South-Eastern Sector of The Cantabrian Zone (Variscan Belt, Northwestern Spain)Document20 pagesTectonothermal Evolution in The Core of An Arcuate Fold and Thrust Belt: The South-Eastern Sector of The Cantabrian Zone (Variscan Belt, Northwestern Spain)Fernando BastidaNo ratings yet

- Robert Harpole Constable of CarlowDocument13 pagesRobert Harpole Constable of CarlowJohn HayesNo ratings yet

- Encyclopedia of World Religions - Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Zen, Hinduism, Prehistoric, & Primitive ReligionsDocument254 pagesEncyclopedia of World Religions - Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Zen, Hinduism, Prehistoric, & Primitive ReligionsDenys Malta100% (1)

- Star Wars Galaxy MapDocument1 pageStar Wars Galaxy MapVictor Stoinescu100% (1)

- The Carolingian Revival of Early Christian Architecture - Krautheimer - 1942Document50 pagesThe Carolingian Revival of Early Christian Architecture - Krautheimer - 1942Eszter CzuczorNo ratings yet

- MayanBones Nature 0219 PDFDocument4 pagesMayanBones Nature 0219 PDFAnthony CerlaNo ratings yet

- GL25 010Document1 pageGL25 010franckmartin86No ratings yet

- MEC69 - The Ghost of FramsburgDocument2 pagesMEC69 - The Ghost of Framsburgole hansenNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 49.37.34.184 On Fri, 16 Jun 2023 16:13:41 +00:00Document28 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 49.37.34.184 On Fri, 16 Jun 2023 16:13:41 +00:00Wrishi BiswasNo ratings yet

- Mexico City by NightDocument115 pagesMexico City by Nightonslowmo100% (3)

- Understanding Popular Culture - Fiske, John - (2nd Impr.) ., Cambridge, Ma, 1989 - Boston Unwin Hyman - 9780044454380 - Anna's ArchiveDocument228 pagesUnderstanding Popular Culture - Fiske, John - (2nd Impr.) ., Cambridge, Ma, 1989 - Boston Unwin Hyman - 9780044454380 - Anna's ArchiveAnia RychlińskaNo ratings yet

- The Trick is to Keep Breathing: Covid 19 Stories From African and North American WritersFrom EverandThe Trick is to Keep Breathing: Covid 19 Stories From African and North American WritersNo ratings yet

- Aztec-period Ceramic Distribution and Exchange Systems (Final NSF Report)Document254 pagesAztec-period Ceramic Distribution and Exchange Systems (Final NSF Report)CHrisNo ratings yet

- Ehlers Anthro ResponsibilityDocument16 pagesEhlers Anthro ResponsibilityCHrisNo ratings yet

- Chinchilla Class StruggleDocument23 pagesChinchilla Class StruggleCHrisNo ratings yet

- Smithcarol 95Document28 pagesSmithcarol 95CHrisNo ratings yet

- Webre Waterand ColonialismDocument29 pagesWebre Waterand ColonialismCHrisNo ratings yet

- Smith 1990Document35 pagesSmith 1990CHrisNo ratings yet

- Lovell 83 LandDocument18 pagesLovell 83 LandCHrisNo ratings yet

- Mangelsdorf ARCHAEOLOGICALEVIDENCEDIFFUSION 1956Document44 pagesMangelsdorf ARCHAEOLOGICALEVIDENCEDIFFUSION 1956CHrisNo ratings yet

- Linda GreenFearDocument31 pagesLinda GreenFearCHrisNo ratings yet

- ContentServer 2Document8 pagesContentServer 2CHrisNo ratings yet

- ContentServer 3Document5 pagesContentServer 3CHrisNo ratings yet

- Susanne JonasDocument7 pagesSusanne JonasCHrisNo ratings yet

- Lovell 88Document34 pagesLovell 88CHrisNo ratings yet

- ContentServer 1Document2 pagesContentServer 1CHrisNo ratings yet

- Lovelland Lutz 1994Document9 pagesLovelland Lutz 1994CHrisNo ratings yet

- ContentServer 2Document3 pagesContentServer 2CHrisNo ratings yet

- Lovell Etal 84Document20 pagesLovell Etal 84CHrisNo ratings yet

- Frank DaltonsTheoreticalIssues 1970Document6 pagesFrank DaltonsTheoreticalIssues 1970CHrisNo ratings yet

- ContentServer 4Document3 pagesContentServer 4CHrisNo ratings yet

- Berreman AnthropologyAliveSocial 1968Document7 pagesBerreman AnthropologyAliveSocial 1968CHrisNo ratings yet

- Origin, Domestication, and SpreadDocument6 pagesOrigin, Domestication, and SpreadCHrisNo ratings yet

- The Poverty of SustainabilityDocument7 pagesThe Poverty of SustainabilityCHrisNo ratings yet

- Mexican AxolotlDocument2 pagesMexican AxolotlCHrisNo ratings yet

- Wylie 92Document22 pagesWylie 92CHrisNo ratings yet

- Browder LimitsExtractivism 1992Document10 pagesBrowder LimitsExtractivism 1992CHrisNo ratings yet

- McClung AM 26 - 2 - 2015Document16 pagesMcClung AM 26 - 2 - 2015CHrisNo ratings yet

- Brondizio Et Al 2009 Connectivity and The Governance of Multilevel Social Ecological Systems The Role of Social CapitalDocument29 pagesBrondizio Et Al 2009 Connectivity and The Governance of Multilevel Social Ecological Systems The Role of Social CapitalCHrisNo ratings yet

- Dragon Magazine 186Document124 pagesDragon Magazine 186CHris100% (2)

- Wiessner 06Document28 pagesWiessner 06CHrisNo ratings yet

- ZacatalDocument30 pagesZacatalCHrisNo ratings yet

- Assignment Cycle 10Document3 pagesAssignment Cycle 10CelestialNo ratings yet

- Aztec Brainpop NotesDocument1 pageAztec Brainpop Notesapi-253899620No ratings yet

- CH 6 Maya Chavin Part 2Document20 pagesCH 6 Maya Chavin Part 2api-483536703No ratings yet

- Xiii.: Landa Cuz Luumil LuumilDocument21 pagesXiii.: Landa Cuz Luumil LuumilRussell HartillNo ratings yet

- Beniamino Volta and Geoffrey E BraswellDocument49 pagesBeniamino Volta and Geoffrey E BraswellAnna OwczarekNo ratings yet

- Mayan CivilizationDocument2 pagesMayan Civilizationlipanacathlynjoy22No ratings yet

- Chichimec: The Came WasDocument38 pagesChichimec: The Came WasRussell HartillNo ratings yet

- The Myth of "La Malinche": SourceDocument2 pagesThe Myth of "La Malinche": SourcejoannaNo ratings yet

- "Afro-Latina" by Elizabeth AcevedoDocument3 pages"Afro-Latina" by Elizabeth Acevedo2028: Francesca Sardi GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Carta XantoloDocument4 pagesCarta XantoloClaudia AguillónNo ratings yet

- Native American Art Before 1300 CeDocument60 pagesNative American Art Before 1300 Ceragunath palaniswamyNo ratings yet

- The Pre Columbian CivilizationsDocument2 pagesThe Pre Columbian CivilizationsRafa C HortalNo ratings yet

- IS01 AztecDocument14 pagesIS01 AztecNur HidayahNo ratings yet

- Lords of The NightDocument2 pagesLords of The NightAsdf JmasewqNo ratings yet

- Human Sacrifice in Aztec CultureDocument4 pagesHuman Sacrifice in Aztec CulturemariafranciscaNo ratings yet

- MESOAMERICANDocument4 pagesMESOAMERICANGi ChoiNo ratings yet

- The Decapitation Ritual and The AncientDocument12 pagesThe Decapitation Ritual and The AncientB'alam DavidNo ratings yet

- XincaDocument4 pagesXincaRobJeanNo ratings yet

- The AztecsDocument5 pagesThe AztecsAng RNo ratings yet

- Honduran Ethnic HWDocument11 pagesHonduran Ethnic HWvicoso031No ratings yet

- Mitologia AztekówDocument54 pagesMitologia AztekówAnna OwczarekNo ratings yet

- History of The Charro DaysDocument3 pagesHistory of The Charro DaysCristian Damir Martínez VegaNo ratings yet

- The Tale of Lady Winikhaab Ajaw (Marc Zender)Document16 pagesThe Tale of Lady Winikhaab Ajaw (Marc Zender)Muzen DerNo ratings yet

- Aztecs Mayas Incas Chart Answer KeyDocument1 pageAztecs Mayas Incas Chart Answer KeyNathan TakeshiNo ratings yet

- MesoamericaDocument3 pagesMesoamericaJolina AynganNo ratings yet

- An Illustrated Dictionary of The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and The Maya PDFDocument216 pagesAn Illustrated Dictionary of The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and The Maya PDFArielRibeiroTolentino100% (1)

- Mayan Timeline PowerPointDocument1 pageMayan Timeline PowerPointChe LeeNo ratings yet

- Mayan Hieroglyph Presentation 2021 UpdateDocument50 pagesMayan Hieroglyph Presentation 2021 UpdateGary V Stephenson100% (1)

- Diccionario Otomi de Neve y Molina 1767 - FullDocument107 pagesDiccionario Otomi de Neve y Molina 1767 - FulltlakuilokalliNo ratings yet