Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Religion Notes - For Students - 3

Religion Notes - For Students - 3

Uploaded by

chrisjuspCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Concept of God in HinduismDocument16 pagesConcept of God in Hinduismthinzaroo3699No ratings yet

- Lesson 08 - Introduction To World ReligionsDocument12 pagesLesson 08 - Introduction To World ReligionsJozel EulatrizNo ratings yet

- HUMSSIWRBS Grade11 Quarter1 Module Week8Document8 pagesHUMSSIWRBS Grade11 Quarter1 Module Week8jenyanneflorentinoNo ratings yet

- Abstraction: Kama - Love or Pleasure. A Fourth End Is Moksha - The Renunciation ofDocument6 pagesAbstraction: Kama - Love or Pleasure. A Fourth End Is Moksha - The Renunciation ofLalaine RideraNo ratings yet

- Iwrbs 2nd Quarter Module 1Document11 pagesIwrbs 2nd Quarter Module 1jetirish saballaNo ratings yet

- (Unit-3) Prevedic Vedic Religion 14 Oct 21Document19 pages(Unit-3) Prevedic Vedic Religion 14 Oct 21varshaarya22222No ratings yet

- Chapter 5 HinduismDocument48 pagesChapter 5 HinduismEdwardJohnG.CalubIINo ratings yet

- LCMS CTCR Evaluation HinduismDocument5 pagesLCMS CTCR Evaluation HinduismGreg CumbeeNo ratings yet

- Discuss Theories and Perspectives On Spirituality. Describe The Main Ideas of A Certain BeliefDocument6 pagesDiscuss Theories and Perspectives On Spirituality. Describe The Main Ideas of A Certain BeliefAlexandra SolenNo ratings yet

- Complete Moral AssignmentDocument31 pagesComplete Moral AssignmentShino AaronNo ratings yet

- Q2 World ReligionDocument2 pagesQ2 World ReligionYhel LantionNo ratings yet

- About The Beliefs of HinduismDocument2 pagesAbout The Beliefs of HinduismClarixcNo ratings yet

- 7 Dimensions of HinduismDocument28 pages7 Dimensions of Hinduismbuddhaali100% (2)

- Faith Traditions (HINDUISM)Document4 pagesFaith Traditions (HINDUISM)Stephanie Ginger KarganillaNo ratings yet

- Reed 4 Midterm CoverageDocument6 pagesReed 4 Midterm CoveragerymzinepaulescalaNo ratings yet

- Complete Moral AssignmentDocument31 pagesComplete Moral Assignmentkong yiNo ratings yet

- Assignment On A Detailed Study of Hindu Religious TraditionDocument6 pagesAssignment On A Detailed Study of Hindu Religious TraditionLal LawmsangaNo ratings yet

- Midterm One TermsDocument5 pagesMidterm One TermsZainNo ratings yet

- The HinduismDocument8 pagesThe HinduismSusmeethaa PoobalanNo ratings yet

- Hinduism: Romans 2:15Document13 pagesHinduism: Romans 2:15Marissa AsimNo ratings yet

- Hinduism HandoutDocument5 pagesHinduism HandoutKissyNo ratings yet

- JainismDocument17 pagesJainismAnthony ummo oemiiNo ratings yet

- Prepared By: Group 2 Tvl-HousekeepingDocument54 pagesPrepared By: Group 2 Tvl-HousekeepingEstefanie Patacsil100% (1)

- DharmaDocument4 pagesDharmaJarrod GlandtNo ratings yet

- Question 1Document7 pagesQuestion 1Leandro SoaresNo ratings yet

- HINDUISM Written RepDocument2 pagesHINDUISM Written RepVarren LandichoNo ratings yet

- Hinduism Week 8Document23 pagesHinduism Week 8Marvin Garcia OlivaNo ratings yet

- HINDUISMDocument12 pagesHINDUISMzettevasquez8No ratings yet

- Indian Religion, Philosophy and PracticesDocument39 pagesIndian Religion, Philosophy and PracticesSudhanshu Tiwari100% (1)

- The Eastern Religions Buddhism and Hinduism) : Abalorio Leslie DDocument32 pagesThe Eastern Religions Buddhism and Hinduism) : Abalorio Leslie DLyzlie DoblonNo ratings yet

- HinduismDocument42 pagesHinduismDonita Ann MallillinNo ratings yet

- HinduismDocument12 pagesHinduismSergio Sar1gumbaNo ratings yet

- ReviewerDocument19 pagesReviewerElmar Dela TorreNo ratings yet

- Religion of BuddhismDocument11 pagesReligion of BuddhismHamna NisarNo ratings yet

- MIDTERM COVERAGE RS2aDocument4 pagesMIDTERM COVERAGE RS2arezamaeburguite4No ratings yet

- Balaji - FinalHAFHinduism101Document3 pagesBalaji - FinalHAFHinduism101WCSS2015No ratings yet

- 08 - Chapter 3Document51 pages08 - Chapter 3Saurabh JainNo ratings yet

- Historical Background (History and Origin)Document11 pagesHistorical Background (History and Origin)rsyahNo ratings yet

- Hinduism Major Religions of The WorldDocument11 pagesHinduism Major Religions of The WorldBenjamin Chisha ChilufyaNo ratings yet

- A To Z of Jainism PDFDocument45 pagesA To Z of Jainism PDFUday DokrasNo ratings yet

- Barro 1Document9 pagesBarro 1patrickkayeNo ratings yet

- Asian Ethical Traditions - NotesDocument8 pagesAsian Ethical Traditions - Notesskz19914100% (1)

- Itcs-Ch 3Document16 pagesItcs-Ch 3The OneNo ratings yet

- World Religion Reviewer 2nd QuarterDocument9 pagesWorld Religion Reviewer 2nd QuarterMarishka Anika LunaNo ratings yet

- TrigunaDocument13 pagesTrigunaAisha RahatNo ratings yet

- HINDUISMDocument42 pagesHINDUISMVeyd ChanNo ratings yet

- Phylosophy PDFDocument21 pagesPhylosophy PDFMd Imrajul AlamNo ratings yet

- JainDocument4 pagesJainVikas AgrawalNo ratings yet

- HinduismDocument23 pagesHinduismEly DionnNo ratings yet

- Hinduism: Don Honorio Ventura State University Senior High SchoolDocument26 pagesHinduism: Don Honorio Ventura State University Senior High SchoolSakinah De LeonNo ratings yet

- Hinduism by Pankaj SinghDocument16 pagesHinduism by Pankaj Singhpankaj singhNo ratings yet

- Religion Notes - For Students - 4Document6 pagesReligion Notes - For Students - 4chrisjuspNo ratings yet

- HINDUISMDocument61 pagesHINDUISMmaria lovella batara100% (1)

- Buddhism & Hinduism-WickiDocument29 pagesBuddhism & Hinduism-WickiKalaignar ThangarajuNo ratings yet

- HINDUISMDocument34 pagesHINDUISMAlysa Jade VelascoNo ratings yet

- Hinduism at A GlanceDocument19 pagesHinduism at A GlanceProfessor PrabhatNo ratings yet

- Historical BackgroundDocument5 pagesHistorical BackgroundRuby CeronNo ratings yet

- HinduismDocument3 pagesHinduismMargaretteNo ratings yet

- St. Louis Review Center: Refresher Course For Year 2005Document19 pagesSt. Louis Review Center: Refresher Course For Year 2005kzyl prudenceNo ratings yet

- Vishnu Patron Saint of ANGKORDocument32 pagesVishnu Patron Saint of ANGKORudayNo ratings yet

- O Tatturya Rakshayet-Sarva-Sharira Devi SarvatDocument5 pagesO Tatturya Rakshayet-Sarva-Sharira Devi SarvatmalikNo ratings yet

- Approved Projects PDFDocument115 pagesApproved Projects PDFmunnabhaai07No ratings yet

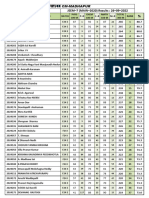

- JEEM-7 Results (MAIN-2020) 26-09-2022 - F24 MDP JuniorsDocument5 pagesJEEM-7 Results (MAIN-2020) 26-09-2022 - F24 MDP Juniorsabhinav kotaNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Tantra SadhanaDocument5 pagesAn Overview of Tantra SadhanaZoran MirovicNo ratings yet

- List of Colleges/Departments Affiliated To Dusu (2013 14)Document4 pagesList of Colleges/Departments Affiliated To Dusu (2013 14)Golu SinghNo ratings yet

- MATRI VANI Volume 1Document61 pagesMATRI VANI Volume 1peterNo ratings yet

- Time & Its All-Pervasive Effect On Our Universe - An In-Depth Study of The Divine Text: Bhagavad GitaDocument5 pagesTime & Its All-Pervasive Effect On Our Universe - An In-Depth Study of The Divine Text: Bhagavad GitayaraganiparjanyaNo ratings yet

- Full Main Log BookDocument89 pagesFull Main Log BookNAGULAN SENTHILMURUGANNo ratings yet

- PookalamDocument1 pagePookalamjammu_d_gr8No ratings yet

- Law and Justice in The Globalizing WorldDocument32 pagesLaw and Justice in The Globalizing WorldIshan SharmaNo ratings yet

- Inimistic Practices Among Tharus of Dang Deokhuri: Poonam RanaDocument13 pagesInimistic Practices Among Tharus of Dang Deokhuri: Poonam RanaNathuram ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- 2015.56751.origin and Growth of Sri Brahmatantra Parakala Mutt - Text PDFDocument560 pages2015.56751.origin and Growth of Sri Brahmatantra Parakala Mutt - Text PDFGiridhar TatacharNo ratings yet

- Suna Pila: Odisha:-India'S Best Kept SecretDocument12 pagesSuna Pila: Odisha:-India'S Best Kept SecretAkanksha SarangiNo ratings yet

- Festival and GodDocument9 pagesFestival and GodAyan BhattacharjeeNo ratings yet

- Tugas Language TestingDocument6 pagesTugas Language TestingAlifaa anfNo ratings yet

- SST Class 7 SeeDocument3 pagesSST Class 7 SeeNANDITA 9A2020No ratings yet

- A Study of Temples of Medieval MaharashtDocument195 pagesA Study of Temples of Medieval MaharashtPrajakta deopujariNo ratings yet

- Narasimhar Temples From ChennaiDocument25 pagesNarasimhar Temples From ChennaiSriram SrinivasanNo ratings yet

- Lagna in Different RashisDocument74 pagesLagna in Different RashisGopiNo ratings yet

- Inauspicious DeathDocument2 pagesInauspicious DeathSandeep ArkalgudNo ratings yet

- Ganesh SlokaDocument29 pagesGanesh SlokaPayeli DuttaNo ratings yet

- Joshimath To Govindghat. Then Comes The 14 KM Trek From Govindghat To Ghangria, Along The River Ghangria, The Valley of Flowers Is A 3 KM Climb, Where One Has To Go Daily and Come Back The Same DayDocument5 pagesJoshimath To Govindghat. Then Comes The 14 KM Trek From Govindghat To Ghangria, Along The River Ghangria, The Valley of Flowers Is A 3 KM Climb, Where One Has To Go Daily and Come Back The Same DayGanesh RameshNo ratings yet

- Melpathur Narayana BhattathiriDocument2 pagesMelpathur Narayana BhattathiriRadhakrishnan NairNo ratings yet

- Athithi Devo BhavaDocument12 pagesAthithi Devo BhavaJayasree SaranathanNo ratings yet

- F. Max Müller THE UPANISHADS 1 PDFDocument448 pagesF. Max Müller THE UPANISHADS 1 PDFJosé MeNo ratings yet

- The Vedanta Kesari - March 2024Document52 pagesThe Vedanta Kesari - March 2024dhrubakidsNo ratings yet

- 2022-04-14-Enhance Your Life With Devi Bhairavi's GraceDocument6 pages2022-04-14-Enhance Your Life With Devi Bhairavi's GraceRonnit gargNo ratings yet

- Gayatri Deep Yagya Script For Vasant Panchami - FinalDocument28 pagesGayatri Deep Yagya Script For Vasant Panchami - FinalShreyaa NarulaNo ratings yet

- Radhanath Swami On-Power of Habits Prerna: The Journey Home Book - by Radhanath Swami SearchDocument7 pagesRadhanath Swami On-Power of Habits Prerna: The Journey Home Book - by Radhanath Swami SearchdamodaraNo ratings yet

Religion Notes - For Students - 3

Religion Notes - For Students - 3

Uploaded by

chrisjuspOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Religion Notes - For Students - 3

Religion Notes - For Students - 3

Uploaded by

chrisjuspCopyright:

Available Formats

Page |1

HINDUISM

Hinduism, also known as Sanatana Dharma, is the world’s oldest living religion. It

has neither a founder figure nor an organisational system. There is no creed defined as

essential to it. It is so diverse in its beliefs and practices as to manifest the vast regional

variations of the Subcontinent.

1. Origin

The archaeological findings of Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa have given clues about

the nature of the earliest religion that existed in the Subcontinent. When the Aryan

communities came to the Subcontinent from the northwest about 1,500 BCE, they found

a striking contrast with the natives of the soil that they referred to as ‘Dasus’, having

darker skin, defending themselves from forts, worshipping phallus1 etc.

However, over time, a two-way process of interaction took place between the

invading communities and the indigenous people. A hybrid kind of religious tie-ups

developed over a long period until 500 BCE. It was this new Indo-Aryan religion that was

later called Hinduism.

Hindu word was derived from the river flow in northern India, Indus. In ancient

times, this river was known as the Sindhu River, but when Persians came to India, they

called it Hindu, and to the land Hindustan, the people residing here were called Hindus.

Likewise, the term ‘Hindu’ came into existence in the 6th century BCE referring to a

geographical terrain rather than a cultural sect.

2. Scriptures

The sacred scriptures of Hinduism are classified into two sets of literature; The

Sruti and The Smrti.

2.1 Sruti

The term ‘Sruti’ literally means “what was heard”. There are five kinds of Sruti

literature: (i)Vedas, (ii) Brahmanas, (iii) Aranyakas and (iv)Upanishads.

1. The earliest literary manifestation of the Hindu religion is called the Veda, which

literally means ‘knowledge’, and to the orthodox Hindu, they are the eternal

words (vac), self-existent truths, constituting the divine revelation.

2. Brahmanas are mostly prose works added to the Vedas, explaining the

procedures of sacrificial rituals.

3. Aranyakas are ‘Forest Books’ composed of those who had renounced the

ritualistic sacrifices at home and gone to forests to live in favour of meditation.

4. Upanishads are philosophical and mystical utterances that are regarded as the

core of the Vedas, and so were called the ‘Vedanta’ (the end of Vedas).

Ancient Sanskrit texts such as the Mahabharata and the Puranas relate narratives that identify

1

the lingam as the phallus of Shiva. Practising Hindus consider the lingam and yoni together to symbolize

the union of the male and female principles and the totality of all existence.

Introduction to Major Religions – Notes JMBC

Prepared by Rev. Justin Paul

Page |2

2.2 Smriti

The term ‘Smriti’ literally means ‘that which was remembered’, and so it refers to

tradition. Therefore, they have only secondary authority, in so far as they are in

accordance with the Vedas. They include:

1. The two Ithikasas or Epics (Ramayana and Mahabharata)

2. The Puranas (sacred chronicles with a lot of legendary romances)

3. The Dharma Shastras (codes of law)

4. The Darshanas (Philosophical schools)

5. Agamas (Manuals of worship).

3. God Concept

The immigrant Aryan communities brought their own gods. Along with that, each

of the diverse racial groups that existed across the Subcontinent had its own gods or

goddesses. The Aryan community went on conquering the local kingdoms, they also

absorbed their gods. But the whole process was taking place in some systematic way so

that eventually it gave rise to the doctrine of the Hindu trinity (Trimurthi): Brahma,

Vishnu and Shiva.

In the Upanishadic understanding, there is in an eternal, infinite and all-embracing

ultimate force called Brahman. The relationship between the Brahman (the universal

soul) and Atman (the individual soul) has been the main concern in Upanishads. But later

this idea of Brahman, got referred to the background and represented as a personal god

as Brahma, with human qualities, having creation as his main function.

Vishnu, a minor god of Vedas, got syncretised with various existing deities, with a

new identity as a benevolent god, concerned for the welfare of the world. He is said to

periodically descend into the world through his avatars. Shiva, originally a pre-Aryan god

of South India, was identified by the Puranas with the Vedic god Rudra and was depicted

as a fiercer figure, symbolizing both the creative and destructive aspects of deity.

Another remarkable development is that the divine energy of the threefold gods

was also seen as a distinct female deity. Thus Goddess-worship also emerged,

representing each member of Trimurthi with a companion.

4. Purushartas

A fourfold goal of human life is set for the integrated personality. These fourfold

ends of human life are called the Purushartas. They are usually put in a single formula:

“Dharma- artha- kama- Moksha” which sums up the whole of ethical teachings of a

Hindu life. The Righteousness (dharma) of life consists in directing our passions (kama)

and possessions (artha) to a spiritual end (moksha).

5. Varnashrama Dharma

Varnashrama Dharma implies one’s personal ethics and social ethics. The one part

of the formula, viz.

• ‘Ashrama dharma’ defines the personal ethics of a Hindu life.

• while the other part of it ‘Varna dharma’ defines Hindu social ethics.

The personal ethics of an individual is organized into four stages (ashramas).

1. Brahmacharya: The student’s phase, demands one to learn one of the Vedas.

Introduction to Major Religions – Notes JMBC

Prepared by Rev. Justin Paul

Page |3

2. Grahasta: The Householder’s life, requires him to perform domestic rituals of the

Brahmanas to get his desired benefits.

3. Vanaprastha: The Forest dweller’s life, requires him to follow the teachings of the

Aranyakas, internalizing the sacrificial rites. It starts when the householder, after

living a full and fruitful life, throws off his family ties and devotes himself to the study

of scriptures and religious practices.

4. Sanyasi: The life of the renouncer, necessitates him to live a life of complete

renunciation and solitude with the only aim of realization of spiritual freedom or

mystic union with the divine.

The Social ethics of Hindus was summed up in the Varna dharma. The Hindu

society is divided into four main classes;

1. Brahmana (the priestly & teaching class),

2. Kshatriya (the warrior and ruling class),

3. Vaisya (the agricultural and commercial class) and

4. Sudra (the serving and labourers’ class).

Apart from the four, there is what is called the outcaste - the ‘avarna,’ who are

marginalized from the mainstream in every aspect.

6. Salvation

The Truth is One, but the Paths are Many…

The Bhagavad Gita praises three major margas or paths of Yoga which help a

person base his personal nature with the highest goal, realization and union with

Brahman.

Although each path is different, the destination is ultimately the same. One path is

not higher than the other; rather the lessons of each contain its unique wisdom that

provides an integrated and balanced view of one’s relationship to oneself and the higher

reality.

These three paths are:

1. Karma Yoga: The Path of Selfless Action

2. Bhakti Yoga: The Path of Devotion

3. Jnana Yoga: The Path of Self-Transcending Knowledge

Karma Yoga

Karma Yoga is essentially doing one’s duties in life as per his/her dharma, or duty,

without concern for results. It is an action done without thought of gain. One cannot

live in the world without performing actions, and thus a proper mindset should be

established when doing these actions.

Karma Yoga purifies the heart by teaching one to act selflessly, without thought

of gain or reward. By detaching oneself from the fruits of one’s actions and offering them

up to God, one learns to redirect the ego. This is the difference between simply

performing actions for personal gains, and performing actions without attachment

(vairagya) as a spiritual practice where all fruits are given to God. This is the most difficult

of all paths as most of us are attached to the fruits of our actions.

Introduction to Major Religions – Notes JMBC

Prepared by Rev. Justin Paul

Page |4

Bhakti Yoga

Bhakti yoga is based on the doctrine “Love is God and God is Love”. The Deity is

the beloved and the devotee is the lover. In Bhakti yoga, everything is but a manifestation

of the divine and all else is meaningless, including the Ego. When the Bhakta is blessed by

divine grace, he feels an undivided union and non-dual consciousness prevails. Bhakti

Yoga is regarded as the most direct method to merge in cosmic consciousness.

This path appeals particularly to those of an emotional nature. Through prayer,

worship, chanting and ritual one surrenders himself to God or object of faith,

channelling and transmuting his emotions into unconditional love and devotion.

Continuous meditation of God or an object of faith gradually decreases the ego of the

practitioner. Suppressed emotions get released and the purification of the inner self

takes place. Slowly the practitioner loses the self-identity and becomes one with God or

the object of faith, this is the state of self-realization.

Jnana Yoga

Jnana Yoga is a process of learning to discriminate between what is real and what

is not, what is eternal and what is not. Through a steady advancement in realization of

the distinction between Real and the Unreal, the Eternal and the Temporal, one develops

into a Jnani. This is essentially a path of knowledge and discrimination in regard to the

difference between the immortal soul (atman) and the body.

Jnana Yoga is the process of converting intellectual knowledge into practical

wisdom. Jnana literally means ‘knowledge’, but in the context of yoga it means the

process of meditative awareness which leads to illuminative wisdom. It is not a method

by which we try to find rational answers to eternal questions, rather it is a part of

meditation leading to self-enquiry and self-realisation.

Taking the philosophy of Vedanta, the Jnana Yogi uses his mind to inquire into its

own nature. Jnana Yoga leads the devotee to experience his unity with God and dissolving

the shrouds of ignorance (maya).

Thus, the paths of salvation that suits one must be decided by each and adopt it

for attaining salvation.

In the early 21st century, Hinduism had nearly one billion adherents worldwide

and was the religion of about 80 per cent of India’s population. Despite its global

presence, however, it is best understood through its many distinctive regional

manifestations.

Introduction to Major Religions – Notes JMBC

Prepared by Rev. Justin Paul

Page |5

JAINISM

Jainism is an ancient religion that is rooted in the philosophy that teaches the way

to liberation and a path to spiritual purity and enlightenment through disciplined

nonviolence to all living creatures.

1. When did Jainism Originate?

• Jainism came to prominence in the 6th century B.C.E. when Lord Mahavira

propagated the religion.

• There were 24 great teachers, the last of whom was Lord Mahavira.

• These twenty-four teachers were called Tirthankaras-people who had attained

all knowledge (Moksha) while living and preached it to the people.

• The first Tirthankara was Rishabnatha.

• The word ‘Jain’ is derived from Jina or Jaina which means the ‘Conqueror’.

2. Cause of Origin

• Hinduism had become rigid and orthodox with complex rituals and the dominance

of Brahmins.

• The Varna system divided the society into 4 classes based on birth, where the two

higher classes enjoyed several privileges.

• Kshatriya’s reaction against the domination of the Brahmanas.

• Spread of the new agricultural economy in north-eastern India due to the use of

iron tools.

3. Scripture

Most of the ancient Jain texts are written in Prakrta (an early form of Sanskrit).

The general outline of the canon is as follows. It is divided into six sections and contains

either forty-five or forty-six books which are I.) The twelve Angas or limbs, II.) The twelve

Upangas, or secondary limbs, III.) The ten Painnas, or ‘Scattered pieces,’ IV.) The six

Cheya-Suttas, V.) Individual texts (two), VI.) The four Mula-Suttas.

4. The Concept of God

Jainism believes that the universe and all its substances or entities are eternal. It

has no beginning or end concerning time. The universe runs on its own accord by its

cosmic laws.

All substances change or modify their forms continuously. Nothing can be destroyed

or created in the universe.

• There is no need for someone to create or manage the affairs of the universe.

• Hence Jainism does not believe in God as a creator, survivor, and destroyer of the

universe.

However, Jainism does believe in God, not as a creator, but as a perfect being.

• When a person destroys all his karmas, he becomes a liberated soul. He lives in a

perfect blissful state in Moksha forever.

• The liberated soul possesses infinite knowledge, infinite vision, infinite power,

and infinite bliss. This living being is a God of the Jain religion.

• Every living being has the potential to become God.

Hence Jains do not have one God, but Jain Gods are innumerable and their number is

continuously increasing as more living beings attain liberation.

Introduction to Major Religions – Notes JMBC

Prepared by Rev. Justin Paul

Page |6

5. Concept of Soul

The Jaina holds that every living and non-living being is gifted with souls. All souls

are not equally conscious, but every soul has the potential to attain infinite consciousness,

power, and happiness. Each Jiva (soul) is eternally associated with Ajiva (non-sentient or

non-conscious being) because of Karman. They are obstructed by karma, just as the

natural light of the sun is hindered by clouds. By removing the karmas, a soul can remove

bondage and regain its natural perfections. The Karma or the sum of the past life of a soul

- its past thought, speech, and activity - generates in its certain blind cravings and

passions that seek satisfaction.

6. Ethics

The most important part of Jaina philosophy is its ethics. The goal of right conduct

is salvation (moksa), which negatively means the removal of all bondage of the soul, and

positively, the attainment of liberation.

For spiritual discipline, there are twelve vows. They are: the gross vow of

refraining from violence, refraining from telling lies, refraining from taking anything

that is not given, refraining from sexual activities, limiting one’s possessions, limiting

the area of acts that are not virtuous, limiting the quality of things that could be used

once as also of things that could be used repeatedly, to abstain from harmful activities

that serve no useful purpose, remaining completely calm and composed for a fixed

period, reducing the limits of the area outlined in the sixth vow for a limited period,

observing fast and living like a monk for certain days, and sharing things with deserving

guests.

Some of them consider the first five, namely, the five great vows (Pancha Vrathas)

as sufficient for the perfection of conduct. They are the following. Ahimsa or Non-violence

is the most important vow. It is abstinence from all injury to life. Satya or Truth is

abstinence from falsehood. Astheya or Non-stealing consists in not taking what is not

given. Brahmacharaya consists in abstaining from all forms of self-indulgence. This

refers to purity of personal conduct in the matter of sex. Aparigraha or Abstinence from

all attachment consists in abstaining from all attachment to the senses. Liberation is

impossible without the withdrawal of attachment.

7. Liberation (Moksa)

Liberation is the expulsion of matter from the soul. It is achieved through

observing Right faith, Right knowledge, and Right conduct which are known as the Three

Gems (Triranta). Liberation is the joint effect of these three.

1. Right Faith (samyag-darshana): Right faith is an attitude of respect towards truth.

Perfect faith can result only from perfect knowledge. It is a cyclical process.

2. Right Knowledge (samyag-jnana): Right knowledge consists in the detailed

knowledge of all truths. All our miseries and distresses are due to our ignorance

of the soul.

3. Right Conduct (samyak-caritra): Right conduct is refraining from wrong and

performing what is right. The true meaning of ‘right conduct’ is to make one’s life

Introduction to Major Religions – Notes JMBC

Prepared by Rev. Justin Paul

Page |7

pure, keeping it aloof from vices and moral defilements, and to help others strive

for the good according to one’s ability.

8. Jain Sects

There are two important Jain sects, the Svetambaras (wearers of white clothes)

and the Digambaras (the naked). The literal meaning of the word digambara is sky-clad

and that of svetambara is white clad.

1. The Digambara thinks that a man should abstain from food and possessions,

including clothing, to become a saint. The Digambaras strictly maintain that there

can be no salvation without nakedness. Since women cannot go without clothes,

they are said to be incapable of salvation. The Digambaras believe that no original

canonical text exists now.

2. The Svetambaras still preserve a good number of original scriptures. They

believe that it is attachment to material things, that acts as an obstacle to salvation.

If one is free from passions and observes the spiritual practice of non-attachment,

then clothing is not an obstacle to salvation. The Svetambaras also allow women

to enter the monastic order under the assumption that they have a possibility of

attaining Nirvana.

9. What is the Relevance of Jain Ideology in Today’s World?

Contribution of Jainism:

• Attempts to reform the evils of the varna order.

• Contributed to architecture and literature immensely.

Ø Layana/Gumphas (Caves)

Ø Ellora Caves (Cave No. 30-35)- Maharashtra

Introduction to Major Religions – Notes JMBC

Prepared by Rev. Justin Paul

You might also like

- Concept of God in HinduismDocument16 pagesConcept of God in Hinduismthinzaroo3699No ratings yet

- Lesson 08 - Introduction To World ReligionsDocument12 pagesLesson 08 - Introduction To World ReligionsJozel EulatrizNo ratings yet

- HUMSSIWRBS Grade11 Quarter1 Module Week8Document8 pagesHUMSSIWRBS Grade11 Quarter1 Module Week8jenyanneflorentinoNo ratings yet

- Abstraction: Kama - Love or Pleasure. A Fourth End Is Moksha - The Renunciation ofDocument6 pagesAbstraction: Kama - Love or Pleasure. A Fourth End Is Moksha - The Renunciation ofLalaine RideraNo ratings yet

- Iwrbs 2nd Quarter Module 1Document11 pagesIwrbs 2nd Quarter Module 1jetirish saballaNo ratings yet

- (Unit-3) Prevedic Vedic Religion 14 Oct 21Document19 pages(Unit-3) Prevedic Vedic Religion 14 Oct 21varshaarya22222No ratings yet

- Chapter 5 HinduismDocument48 pagesChapter 5 HinduismEdwardJohnG.CalubIINo ratings yet

- LCMS CTCR Evaluation HinduismDocument5 pagesLCMS CTCR Evaluation HinduismGreg CumbeeNo ratings yet

- Discuss Theories and Perspectives On Spirituality. Describe The Main Ideas of A Certain BeliefDocument6 pagesDiscuss Theories and Perspectives On Spirituality. Describe The Main Ideas of A Certain BeliefAlexandra SolenNo ratings yet

- Complete Moral AssignmentDocument31 pagesComplete Moral AssignmentShino AaronNo ratings yet

- Q2 World ReligionDocument2 pagesQ2 World ReligionYhel LantionNo ratings yet

- About The Beliefs of HinduismDocument2 pagesAbout The Beliefs of HinduismClarixcNo ratings yet

- 7 Dimensions of HinduismDocument28 pages7 Dimensions of Hinduismbuddhaali100% (2)

- Faith Traditions (HINDUISM)Document4 pagesFaith Traditions (HINDUISM)Stephanie Ginger KarganillaNo ratings yet

- Reed 4 Midterm CoverageDocument6 pagesReed 4 Midterm CoveragerymzinepaulescalaNo ratings yet

- Complete Moral AssignmentDocument31 pagesComplete Moral Assignmentkong yiNo ratings yet

- Assignment On A Detailed Study of Hindu Religious TraditionDocument6 pagesAssignment On A Detailed Study of Hindu Religious TraditionLal LawmsangaNo ratings yet

- Midterm One TermsDocument5 pagesMidterm One TermsZainNo ratings yet

- The HinduismDocument8 pagesThe HinduismSusmeethaa PoobalanNo ratings yet

- Hinduism: Romans 2:15Document13 pagesHinduism: Romans 2:15Marissa AsimNo ratings yet

- Hinduism HandoutDocument5 pagesHinduism HandoutKissyNo ratings yet

- JainismDocument17 pagesJainismAnthony ummo oemiiNo ratings yet

- Prepared By: Group 2 Tvl-HousekeepingDocument54 pagesPrepared By: Group 2 Tvl-HousekeepingEstefanie Patacsil100% (1)

- DharmaDocument4 pagesDharmaJarrod GlandtNo ratings yet

- Question 1Document7 pagesQuestion 1Leandro SoaresNo ratings yet

- HINDUISM Written RepDocument2 pagesHINDUISM Written RepVarren LandichoNo ratings yet

- Hinduism Week 8Document23 pagesHinduism Week 8Marvin Garcia OlivaNo ratings yet

- HINDUISMDocument12 pagesHINDUISMzettevasquez8No ratings yet

- Indian Religion, Philosophy and PracticesDocument39 pagesIndian Religion, Philosophy and PracticesSudhanshu Tiwari100% (1)

- The Eastern Religions Buddhism and Hinduism) : Abalorio Leslie DDocument32 pagesThe Eastern Religions Buddhism and Hinduism) : Abalorio Leslie DLyzlie DoblonNo ratings yet

- HinduismDocument42 pagesHinduismDonita Ann MallillinNo ratings yet

- HinduismDocument12 pagesHinduismSergio Sar1gumbaNo ratings yet

- ReviewerDocument19 pagesReviewerElmar Dela TorreNo ratings yet

- Religion of BuddhismDocument11 pagesReligion of BuddhismHamna NisarNo ratings yet

- MIDTERM COVERAGE RS2aDocument4 pagesMIDTERM COVERAGE RS2arezamaeburguite4No ratings yet

- Balaji - FinalHAFHinduism101Document3 pagesBalaji - FinalHAFHinduism101WCSS2015No ratings yet

- 08 - Chapter 3Document51 pages08 - Chapter 3Saurabh JainNo ratings yet

- Historical Background (History and Origin)Document11 pagesHistorical Background (History and Origin)rsyahNo ratings yet

- Hinduism Major Religions of The WorldDocument11 pagesHinduism Major Religions of The WorldBenjamin Chisha ChilufyaNo ratings yet

- A To Z of Jainism PDFDocument45 pagesA To Z of Jainism PDFUday DokrasNo ratings yet

- Barro 1Document9 pagesBarro 1patrickkayeNo ratings yet

- Asian Ethical Traditions - NotesDocument8 pagesAsian Ethical Traditions - Notesskz19914100% (1)

- Itcs-Ch 3Document16 pagesItcs-Ch 3The OneNo ratings yet

- World Religion Reviewer 2nd QuarterDocument9 pagesWorld Religion Reviewer 2nd QuarterMarishka Anika LunaNo ratings yet

- TrigunaDocument13 pagesTrigunaAisha RahatNo ratings yet

- HINDUISMDocument42 pagesHINDUISMVeyd ChanNo ratings yet

- Phylosophy PDFDocument21 pagesPhylosophy PDFMd Imrajul AlamNo ratings yet

- JainDocument4 pagesJainVikas AgrawalNo ratings yet

- HinduismDocument23 pagesHinduismEly DionnNo ratings yet

- Hinduism: Don Honorio Ventura State University Senior High SchoolDocument26 pagesHinduism: Don Honorio Ventura State University Senior High SchoolSakinah De LeonNo ratings yet

- Hinduism by Pankaj SinghDocument16 pagesHinduism by Pankaj Singhpankaj singhNo ratings yet

- Religion Notes - For Students - 4Document6 pagesReligion Notes - For Students - 4chrisjuspNo ratings yet

- HINDUISMDocument61 pagesHINDUISMmaria lovella batara100% (1)

- Buddhism & Hinduism-WickiDocument29 pagesBuddhism & Hinduism-WickiKalaignar ThangarajuNo ratings yet

- HINDUISMDocument34 pagesHINDUISMAlysa Jade VelascoNo ratings yet

- Hinduism at A GlanceDocument19 pagesHinduism at A GlanceProfessor PrabhatNo ratings yet

- Historical BackgroundDocument5 pagesHistorical BackgroundRuby CeronNo ratings yet

- HinduismDocument3 pagesHinduismMargaretteNo ratings yet

- St. Louis Review Center: Refresher Course For Year 2005Document19 pagesSt. Louis Review Center: Refresher Course For Year 2005kzyl prudenceNo ratings yet

- Vishnu Patron Saint of ANGKORDocument32 pagesVishnu Patron Saint of ANGKORudayNo ratings yet

- O Tatturya Rakshayet-Sarva-Sharira Devi SarvatDocument5 pagesO Tatturya Rakshayet-Sarva-Sharira Devi SarvatmalikNo ratings yet

- Approved Projects PDFDocument115 pagesApproved Projects PDFmunnabhaai07No ratings yet

- JEEM-7 Results (MAIN-2020) 26-09-2022 - F24 MDP JuniorsDocument5 pagesJEEM-7 Results (MAIN-2020) 26-09-2022 - F24 MDP Juniorsabhinav kotaNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Tantra SadhanaDocument5 pagesAn Overview of Tantra SadhanaZoran MirovicNo ratings yet

- List of Colleges/Departments Affiliated To Dusu (2013 14)Document4 pagesList of Colleges/Departments Affiliated To Dusu (2013 14)Golu SinghNo ratings yet

- MATRI VANI Volume 1Document61 pagesMATRI VANI Volume 1peterNo ratings yet

- Time & Its All-Pervasive Effect On Our Universe - An In-Depth Study of The Divine Text: Bhagavad GitaDocument5 pagesTime & Its All-Pervasive Effect On Our Universe - An In-Depth Study of The Divine Text: Bhagavad GitayaraganiparjanyaNo ratings yet

- Full Main Log BookDocument89 pagesFull Main Log BookNAGULAN SENTHILMURUGANNo ratings yet

- PookalamDocument1 pagePookalamjammu_d_gr8No ratings yet

- Law and Justice in The Globalizing WorldDocument32 pagesLaw and Justice in The Globalizing WorldIshan SharmaNo ratings yet

- Inimistic Practices Among Tharus of Dang Deokhuri: Poonam RanaDocument13 pagesInimistic Practices Among Tharus of Dang Deokhuri: Poonam RanaNathuram ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- 2015.56751.origin and Growth of Sri Brahmatantra Parakala Mutt - Text PDFDocument560 pages2015.56751.origin and Growth of Sri Brahmatantra Parakala Mutt - Text PDFGiridhar TatacharNo ratings yet

- Suna Pila: Odisha:-India'S Best Kept SecretDocument12 pagesSuna Pila: Odisha:-India'S Best Kept SecretAkanksha SarangiNo ratings yet

- Festival and GodDocument9 pagesFestival and GodAyan BhattacharjeeNo ratings yet

- Tugas Language TestingDocument6 pagesTugas Language TestingAlifaa anfNo ratings yet

- SST Class 7 SeeDocument3 pagesSST Class 7 SeeNANDITA 9A2020No ratings yet

- A Study of Temples of Medieval MaharashtDocument195 pagesA Study of Temples of Medieval MaharashtPrajakta deopujariNo ratings yet

- Narasimhar Temples From ChennaiDocument25 pagesNarasimhar Temples From ChennaiSriram SrinivasanNo ratings yet

- Lagna in Different RashisDocument74 pagesLagna in Different RashisGopiNo ratings yet

- Inauspicious DeathDocument2 pagesInauspicious DeathSandeep ArkalgudNo ratings yet

- Ganesh SlokaDocument29 pagesGanesh SlokaPayeli DuttaNo ratings yet

- Joshimath To Govindghat. Then Comes The 14 KM Trek From Govindghat To Ghangria, Along The River Ghangria, The Valley of Flowers Is A 3 KM Climb, Where One Has To Go Daily and Come Back The Same DayDocument5 pagesJoshimath To Govindghat. Then Comes The 14 KM Trek From Govindghat To Ghangria, Along The River Ghangria, The Valley of Flowers Is A 3 KM Climb, Where One Has To Go Daily and Come Back The Same DayGanesh RameshNo ratings yet

- Melpathur Narayana BhattathiriDocument2 pagesMelpathur Narayana BhattathiriRadhakrishnan NairNo ratings yet

- Athithi Devo BhavaDocument12 pagesAthithi Devo BhavaJayasree SaranathanNo ratings yet

- F. Max Müller THE UPANISHADS 1 PDFDocument448 pagesF. Max Müller THE UPANISHADS 1 PDFJosé MeNo ratings yet

- The Vedanta Kesari - March 2024Document52 pagesThe Vedanta Kesari - March 2024dhrubakidsNo ratings yet

- 2022-04-14-Enhance Your Life With Devi Bhairavi's GraceDocument6 pages2022-04-14-Enhance Your Life With Devi Bhairavi's GraceRonnit gargNo ratings yet

- Gayatri Deep Yagya Script For Vasant Panchami - FinalDocument28 pagesGayatri Deep Yagya Script For Vasant Panchami - FinalShreyaa NarulaNo ratings yet

- Radhanath Swami On-Power of Habits Prerna: The Journey Home Book - by Radhanath Swami SearchDocument7 pagesRadhanath Swami On-Power of Habits Prerna: The Journey Home Book - by Radhanath Swami SearchdamodaraNo ratings yet