Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 65.88.89.49 On Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 65.88.89.49 On Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

Uploaded by

maryam sehatCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Art of Taking a Walk: Flanerie, Literature, and Film in Weimar CultureFrom EverandThe Art of Taking a Walk: Flanerie, Literature, and Film in Weimar CultureRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Antliff, Mark - Fascism, Modernism, and ModernityDocument23 pagesAntliff, Mark - Fascism, Modernism, and Modernitymadmonkey244No ratings yet

- Antliff, Mark. ''Fascism, Modernism, and Modernity'' PDFDocument23 pagesAntliff, Mark. ''Fascism, Modernism, and Modernity'' PDFiikNo ratings yet

- Charles Jencks Postmodernism DefinedDocument28 pagesCharles Jencks Postmodernism DefinedNoel Thanbutr HuangthongNo ratings yet

- Gombrich - Renaissance and Golden AgeDocument5 pagesGombrich - Renaissance and Golden AgeJorge RasnerNo ratings yet

- 20467157, FlaneurDocument19 pages20467157, FlaneurmunirahwhNo ratings yet

- 07 Britzolakis - Phantasmagoria Walter Benjamin and The Poetics of Urban ModernismDocument20 pages07 Britzolakis - Phantasmagoria Walter Benjamin and The Poetics of Urban ModernismNikos MarkoutsasNo ratings yet

- Whiteley 2001 Reyner Banham Historian of The Immediate Future PDF (052 101)Document50 pagesWhiteley 2001 Reyner Banham Historian of The Immediate Future PDF (052 101)MarinaNo ratings yet

- The Urban Miniature and The Feuilleton in Kracauer and BenjaminDocument15 pagesThe Urban Miniature and The Feuilleton in Kracauer and BenjaminDavid PolarisNo ratings yet

- Primitivism and The Modern - James KnappDocument16 pagesPrimitivism and The Modern - James Knappapi-248985355No ratings yet

- Memories of Capitalism Cities Phantasmag PDFDocument14 pagesMemories of Capitalism Cities Phantasmag PDFMissAudreyAddamsNo ratings yet

- Barroco Como Concepto Básico Del Arte - Ernest C. HassoldDocument29 pagesBarroco Como Concepto Básico Del Arte - Ernest C. Hassolddailearon3110No ratings yet

- A.Abbas-W.Benjamin's Collector - The Fate of Modern ExperienceDocument22 pagesA.Abbas-W.Benjamin's Collector - The Fate of Modern ExperienceΔΗΜΗΤΡΑ ΣΤΑΜΑΤΙΟΥNo ratings yet

- Krauss ReinventingMedium 1999Document18 pagesKrauss ReinventingMedium 1999annysmiNo ratings yet

- Osborne - Peter - Postconceptual Condition PDFDocument9 pagesOsborne - Peter - Postconceptual Condition PDFhamedtayebi100% (2)

- Avangarde PostmodernismDocument19 pagesAvangarde PostmodernismHakan TopateşNo ratings yet

- Mundt 1959Document25 pagesMundt 1959Mirna GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- Rhetoric and Art History in The Italian Renaissance and BaroqueDocument13 pagesRhetoric and Art History in The Italian Renaissance and Baroquethot777100% (1)

- (Theatre Journal 1991-Mar Vol. 43 Iss. 1) Katherine Arens - Robert Wilson - Is Postmodern Performance Possible - (1991) (10.2307 - 3207948) - Libgen - LiDocument28 pages(Theatre Journal 1991-Mar Vol. 43 Iss. 1) Katherine Arens - Robert Wilson - Is Postmodern Performance Possible - (1991) (10.2307 - 3207948) - Libgen - LiRobert ShermanNo ratings yet

- Witte - Introduction To Siegfried Kracauer's The Mass OrnamentDocument9 pagesWitte - Introduction To Siegfried Kracauer's The Mass OrnamentkafrinNo ratings yet

- Huyssen, A. - Avantgarde and PostmodernismDocument19 pagesHuyssen, A. - Avantgarde and PostmodernismMónica AmievaNo ratings yet

- Kemp From Minesis To PhantasiaDocument59 pagesKemp From Minesis To PhantasiaGermán Huici Escribano100% (1)

- René Wellek - The Term and Concept of Symbolism in Literary HistoryDocument23 pagesRené Wellek - The Term and Concept of Symbolism in Literary HistoryEine Gelbe KatzeNo ratings yet

- JUAN DOWNEYS Communication UtopiaDocument24 pagesJUAN DOWNEYS Communication UtopiaGabriela SolNo ratings yet

- Waite - Lenin in Las MeninasDocument39 pagesWaite - Lenin in Las MeninasKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Cohen - 1989 - Benjamin's PhantasmagoriaDocument22 pagesCohen - 1989 - Benjamin's PhantasmagoriaFabianeNo ratings yet

- Hans Robert Jauss Modernidad y Tradicion LiterariaDocument37 pagesHans Robert Jauss Modernidad y Tradicion LiterariagabarsjNo ratings yet

- Walter Benjamin On PhotographyDocument20 pagesWalter Benjamin On PhotographyanNo ratings yet

- Simmons S. (2000) Ernst Kirchner's Streetwalkers. Art, Luxury, and Immorality in Berlin, 1913-16Document33 pagesSimmons S. (2000) Ernst Kirchner's Streetwalkers. Art, Luxury, and Immorality in Berlin, 1913-16Eleni VazakoNo ratings yet

- University of California Press Society of Architectural HistoriansDocument22 pagesUniversity of California Press Society of Architectural HistoriansMo NahNo ratings yet

- Benjamin Buchloh - Allegorical Procedures: Appropriation and Montage in Contemporary ArtDocument15 pagesBenjamin Buchloh - Allegorical Procedures: Appropriation and Montage in Contemporary ArttigerpyjamasNo ratings yet

- Raymond Williams, When Was Modernism, NLR I 175, May June 1989Document5 pagesRaymond Williams, When Was Modernism, NLR I 175, May June 1989nev.thomas96No ratings yet

- Erkki Huhtamo-Kaleidoscomaniac To CybernerdDocument10 pagesErkki Huhtamo-Kaleidoscomaniac To CybernerdMarília LimaNo ratings yet

- Andrew MilnerDocument20 pagesAndrew MilnerAlfredo Luiz SuppiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 202.119.44.27 On Tue, 19 Oct 2021 06:14:08 UTCDocument9 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 202.119.44.27 On Tue, 19 Oct 2021 06:14:08 UTCweareyoung5833No ratings yet

- Nigel Whiteley Reyner Banham Historian oDocument6 pagesNigel Whiteley Reyner Banham Historian oMarinaNo ratings yet

- Cohen Benjamin's PhantasmagoriaDocument22 pagesCohen Benjamin's PhantasmagoriaaliihsanozcanNo ratings yet

- Nicolas Bourriaud - The Radicant (2009)Document176 pagesNicolas Bourriaud - The Radicant (2009)10011854No ratings yet

- In Progress: New Monumentality S Retrospective JustificationDocument41 pagesIn Progress: New Monumentality S Retrospective JustificationMaria Camila GonzalezNo ratings yet

- February 22 - Hilde Heynen, Architecture and Modernity A Critique 2-18Document19 pagesFebruary 22 - Hilde Heynen, Architecture and Modernity A Critique 2-18Ayşe Nur TürkerNo ratings yet

- Duke University Press and New German Critique Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To New German CritiqueDocument19 pagesDuke University Press and New German Critique Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To New German CritiqueJuan Carlos Camacho MolinaNo ratings yet

- OCTO - A - 00142Document23 pagesOCTO - A - 00142kankikhanNo ratings yet

- Tintin As SpectacleDocument21 pagesTintin As SpectacleHélène DestrempesNo ratings yet

- Faking, Forging, Counterfeiting: Discredited Practices at the Margins of MimesisFrom EverandFaking, Forging, Counterfeiting: Discredited Practices at the Margins of MimesisNo ratings yet

- Douglas Crimp, "On The Museum's Ruins"Document18 pagesDouglas Crimp, "On The Museum's Ruins"AnneFilNo ratings yet

- Francis Haskell, Art and The Language of Politics, Journal of European Studies 1974 Haskell 215 32Document19 pagesFrancis Haskell, Art and The Language of Politics, Journal of European Studies 1974 Haskell 215 32meeeemail5322No ratings yet

- Habermas Modernity An Incomplete ProjectDocument7 pagesHabermas Modernity An Incomplete ProjectabsentkernelNo ratings yet

- Agoraphobia - Simmel and Kracauer - Anthony VidlerDocument16 pagesAgoraphobia - Simmel and Kracauer - Anthony VidlerArthur BuenoNo ratings yet

- Cosmos in Film On The Concept of Space in Walter Benjamin's Work of Art EssayDocument13 pagesCosmos in Film On The Concept of Space in Walter Benjamin's Work of Art EssayNyma BehrouzyNo ratings yet

- Walter BenjaminDocument17 pagesWalter BenjaminAnonymous 31GD9V8100% (2)

- CROMBEZ Murderofart Intro TOC 2017Document5 pagesCROMBEZ Murderofart Intro TOC 2017m:mNo ratings yet

- Modernism/ Postmodernism: Peter BrookerDocument112 pagesModernism/ Postmodernism: Peter BrookerAlexandra Nistor100% (1)

- 430964Document37 pages430964ISHFAQ AHMAD LONENo ratings yet

- Jencks PTDocument4 pagesJencks PTLisztNo ratings yet

- Walter BenjaminDocument27 pagesWalter BenjaminPaul ScallanNo ratings yet

- Reproduction/Repetition: Walter Benjamin/Carl Einstein by CHARLES W. HAXTHAUSENDocument29 pagesReproduction/Repetition: Walter Benjamin/Carl Einstein by CHARLES W. HAXTHAUSENAndrea TavaresNo ratings yet

- Topography and Literature: Berlin and Modernism. E-BOOKFrom EverandTopography and Literature: Berlin and Modernism. E-BOOKReinhard ZachauNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of Design: From Russian Constructivism to Modern Brazilian Design.From EverandA Brief History of Design: From Russian Constructivism to Modern Brazilian Design.No ratings yet

- Modernism at the Barricades: aesthetics, Politics, UtopiaFrom EverandModernism at the Barricades: aesthetics, Politics, UtopiaNo ratings yet

- Alberto Asor Rosa-essay-Log9-Manfredo Tafuri or Humanism RevisitedDocument11 pagesAlberto Asor Rosa-essay-Log9-Manfredo Tafuri or Humanism Revisitedmaryam sehatNo ratings yet

- Essay-Christopher Wood-Why Autonomy-2002Document7 pagesEssay-Christopher Wood-Why Autonomy-2002maryam sehatNo ratings yet

- Paul Guyer-essay-Kant Philosophy ArchitectureDocument14 pagesPaul Guyer-essay-Kant Philosophy Architecturemaryam sehatNo ratings yet

- Essay-Fredric Jameson, Leonard Green-Interview With Fredric JamesonDocument21 pagesEssay-Fredric Jameson, Leonard Green-Interview With Fredric Jamesonmaryam sehatNo ratings yet

- Peter Eisenman-essay-Diagram, An Original Scene of Writing-1998Document4 pagesPeter Eisenman-essay-Diagram, An Original Scene of Writing-1998maryam sehatNo ratings yet

- Essay-Sarah Whiting-Thick ThinDocument7 pagesEssay-Sarah Whiting-Thick Thinmaryam sehatNo ratings yet

- Essay-Susan Carty Piedmont-Operative CriticismDocument7 pagesEssay-Susan Carty Piedmont-Operative Criticismmaryam sehatNo ratings yet

- Essay - Fredric Jameson-Regarding Postmodernism-A Conversation With Fredric JamesonDocument29 pagesEssay - Fredric Jameson-Regarding Postmodernism-A Conversation With Fredric Jamesonmaryam sehatNo ratings yet

- Essay-Eduardo Mendieta-Utopia, Dystopia, Utopistics, or The End of UtopiaDocument20 pagesEssay-Eduardo Mendieta-Utopia, Dystopia, Utopistics, or The End of Utopiamaryam sehatNo ratings yet

- Essay-Michael Foucault-Of Other Spaces Utopias and Heterotopia-T by HurleyDocument7 pagesEssay-Michael Foucault-Of Other Spaces Utopias and Heterotopia-T by Hurleymaryam sehatNo ratings yet

- VikingsDocument21 pagesVikingsSusan MilliganNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Unpacked Most Essential Learning Competencies (MELC)Document8 pagesDepartment of Education: Unpacked Most Essential Learning Competencies (MELC)Rubina Pontillas100% (1)

- Placental AbnormalitiesDocument3 pagesPlacental AbnormalitiesThakoon TtsNo ratings yet

- Penggunaan Metode Waterfall Untuk Pengembangan Sistem Monitoring Dan Evaluasi Pembangunan PedesaanDocument26 pagesPenggunaan Metode Waterfall Untuk Pengembangan Sistem Monitoring Dan Evaluasi Pembangunan PedesaanII8I40O24 Oktaviana Rinda SariNo ratings yet

- Julius Caesar TranslationDocument29 pagesJulius Caesar TranslationLIM KAI YI HCINo ratings yet

- May 6, 2016 Strathmore TimesDocument28 pagesMay 6, 2016 Strathmore TimesStrathmore TimesNo ratings yet

- Bloodborne Rulebook FinalDocument28 pagesBloodborne Rulebook FinalDan L'étron TurconNo ratings yet

- Outrageous Mantra ExperimentDocument22 pagesOutrageous Mantra ExperimentPopovici DraganNo ratings yet

- ASTM C 217 Standard Test Method For Weather Resistance of SlateDocument3 pagesASTM C 217 Standard Test Method For Weather Resistance of SlateRyan LasacaNo ratings yet

- Factors Considered During Supplier Evaluation in Procurement ProcessDocument15 pagesFactors Considered During Supplier Evaluation in Procurement Processwaghmodeakshay9337464No ratings yet

- MMW - Task 1 - Golden Ratio ActivityDocument3 pagesMMW - Task 1 - Golden Ratio ActivityKristine Mae Musa AñonuevoNo ratings yet

- ContingentWorker OffboardingTicketDocument7 pagesContingentWorker OffboardingTicketSonia Cuenca AcaroNo ratings yet

- A Glossary of The Words and Phrases of Furness North Lancashire 1000216573Document272 pagesA Glossary of The Words and Phrases of Furness North Lancashire 1000216573Mohammad WaseemNo ratings yet

- Dokumen - Tips - Transfer Pricing QuizDocument5 pagesDokumen - Tips - Transfer Pricing QuizSaeym SegoviaNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Online Product Reviews On Consumer Purchase Intentions: The Moderating Roles of Cognitive Need and Product KnowledgeDocument4 pagesThe Influence of Online Product Reviews On Consumer Purchase Intentions: The Moderating Roles of Cognitive Need and Product KnowledgeRDNo ratings yet

- EiE Competency Framework CPHA Annex enDocument25 pagesEiE Competency Framework CPHA Annex enCumar Cadaani100% (1)

- Εγχειρίδιο Χρήσης WiFi - EVA - II - Pro - Wifi - 0 PDFDocument16 pagesΕγχειρίδιο Χρήσης WiFi - EVA - II - Pro - Wifi - 0 PDFZaital GilNo ratings yet

- Fazendo Dinheiro Com A FotografiaDocument132 pagesFazendo Dinheiro Com A FotografiaGiuseppe DecaroNo ratings yet

- Woody AllenDocument18 pagesWoody Allendougct100% (1)

- Running Times 2014-01-02.bakDocument72 pagesRunning Times 2014-01-02.bakJsueNo ratings yet

- Parental Presence Vs Absence - Dr. Julie ManiateDocument27 pagesParental Presence Vs Absence - Dr. Julie ManiateRooka82No ratings yet

- Ananya Agarwal - Case Study Analysis (CIA 1)Document11 pagesAnanya Agarwal - Case Study Analysis (CIA 1)ANANYA AGARWAL 20224305No ratings yet

- 28224lab 3Document6 pages28224lab 3aman singhNo ratings yet

- Cook and Serve Challenge 2024 Sponsorship Packages and Awards DinnerDocument3 pagesCook and Serve Challenge 2024 Sponsorship Packages and Awards DinnercarlateacherhellologosNo ratings yet

- Love Languages Mystery GameDocument3 pagesLove Languages Mystery GamePittipat Manzano ChupungcoNo ratings yet

- David Copeland-Jackson IndictmentDocument12 pagesDavid Copeland-Jackson IndictmentWashington ExaminerNo ratings yet

- ExaminationForm PDFDocument1 pageExaminationForm PDFSantosh VishwakarmaNo ratings yet

- Extended Prose PieceDocument9 pagesExtended Prose Pieceapi-313980615No ratings yet

- Youth Arts Jersey - MembershipDocument2 pagesYouth Arts Jersey - MembershipSteve HaighNo ratings yet

- Greeshma Vasu: Receptionist/Cashier/Edp Clerk/Customer ServiceDocument2 pagesGreeshma Vasu: Receptionist/Cashier/Edp Clerk/Customer Serviceoday abuassaliNo ratings yet

This Content Downloaded From 65.88.89.49 On Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 65.88.89.49 On Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

Uploaded by

maryam sehatOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 65.88.89.49 On Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 65.88.89.49 On Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

Uploaded by

maryam sehatCopyright:

Available Formats

Walter Benjamin's Myth of the "Flâneur"

Author(s): Martina Lauster

Source: The Modern Language Review , Jan., 2007, Vol. 102, No. 1 (Jan., 2007), pp. 139-

156

Published by: Modern Humanities Research Association

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20467157

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/20467157?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Modern Humanities Research Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to The Modern Language Review

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WALTER BENJAMIN'S MYTH OF THE FLANEUR

The notion of theflcineur, developed by Walter Benjamin at the height of I920S

and I930S modernism when the 'surreal' potential of the previous century's

industrial urban space was explored, has exerted considerable influence on the

way we now interpret nineteenth-century depictions of the city. The concept

has gained unquestioned cognitive status-a sum of insights to be taken for

granted-in contemporary cultural theory. It is the contention of this article

that Benjamin's idea of the fianeur is not only of limited value for an under

standing of nineteenth-century urban experience, but can be seen positively

to hamper it. This detrimental effect results from Benjamin's dogmatic ap

plication of a high-modernist, aesthetic concept of self-loss, derived from a

(flawed) reading of Baudelaire and Poe, to the interpretation of earlier, journa

listic sources conceptualizing the fcitneur. Compared with the mode of viewing

formulated by Poe and Baudelaire, the kind of urban observation presented by

these ephemera of the I830s and i840s is dismissed as lacking cognitive value.

This dismissal has led to a neglect, if not downright demolition, of a whole

genre of nineteenth-century city sketches in 'deconstructive' criticism. What

has shielded Benjamin's pronouncements from being questioned is not only

their own critical thrust informed by Marxist and Freudian theory, but their

apparently solid foundation in empirical textual study. In order to question the

substance of his arguments and to expose his notion of the flaineur as a moder

nist myth, I shall first discuss Benjamin's theorizing of modernity in relation

to the idea of the city stroller. It was his aim to enlighten modernity about

itself, but his critique has, I argue, had an obfuscatory effect which was both

unintentional and necessary, given the peculiarities of his thinking, and which

has been perpetuated by Benjamin-inspired cultural theory. As a second step, I

shall discuss some nineteenth-century materials to illustrate my critical points

against Benjamin and to show that his ideas have handicapped our understand

ing of precisely those journalistic sources (e.g. the Physiologies) from the study

of which his statements derive some of their claim to authority.

Langsam durch belebte StraBen zu gehen, ist ein besonderes Vergniugen. Man wird

iiberspielt von der Eile der anderen, es ist ein Bad in der Brandung. Aber meine

lieben Berliner Mitbiirger machen einem das nicht leicht, wenn man ihnen auch noch

so geschickt ausbiegt. Ich bekomme immer mif3trauische Blicke ab, wenn ich ver

suche, zwischen den Geschaftigen zu flanieren. Ich glaube, man hilt mich fur einen

Taschendieb.'

Franz Hessel's Spazieren in Berlin (I929), from which this passage is taken,

contains motifs that are central to Benjamin's idea of the faneur. These include,

on the one hand, delight in immersing oneself in the crowd, the object of

observation, and on the other hand, being viewed with suspicion since the

keen 'reading' of urban physiognomies shows an affinity with the business of

1 Franz Hessel, 'Der Verd?chtige', in Ein Flaneur in Berlin: Mit Fotografien von Friedrich

Seidenst?cker, Walter Benjamins Skizze 'Die Wiederkehr des Flaneurs' und einem 'Waschzettel' von

Heinz Knobloch (Berlin: Das Arsenal, 1984), p. 7. The volume's text is a re-edition of Hessel's

Spazieren in Berlin.

Modern Language Review, I02 (2007), I39-56

C Modern Humanities Research Association 2007

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I40 Benjamin's Myth of the 'Flaneur'

criminals and detectives. Given Benjamin's friendship and collaboration with

Hessel (who in I926 introduced him to the 'Kunst des Spazierengehens' in Paris

and was his co-author for a planned essay on arcades),2 it is not surprising that

the first-person observer of Hessel's Berlin sketches should be closely related to

the third-person flineur depicted in Benjamin's later work. In fact Benjamin's

review of Spazieren in Berlin, published in Die literarische Welt shortly after

the book's appearance,3 constitutes an important journalistic link in the genesis

of his concept of modernity as it was to be outlined in his I930S essays on

nineteenth-century Paris,4 and in Das Passagen- Werk, his fragmentary magnum

opus with which these essays are directly or indirectly connected. In all of them

the fluineur features among the modern archetypes.

Das Passagen-Werk also offers a clue regarding the methodological signifi

cance of the flineur. The vast array of textual snippets assembled in it includes

Benjamin's own aphoristic remarks as well as quotations from contemporary

cultural studies, and also excerpts from nineteenth-century sources dealing

with phenomena of novelty, e.g. arcades and department stores, panoramas,

exhibitions, fashion, and gaslight. The position from which all these observa

tions are made seems to be that of a strolling spectator, someone who collects

mental notes taken on leisurely city walks and publishes them in the form of

feuilleton sketches and witty essays. In short, they resemble observations of a

flaneur, the viewer who takes pleasure in abandoning himself to the artificial

world of high capitalist civilization. One could describe this figure as the view

ing-device through which Benjamin formulates his own theoretical assump

tions concerning modernity, converging in a Marxist critique of commodity

fetishism. Drawing on Hegelian-Marxist dialectical patterns, this critique is

supposed to make palpable, through precise observation, the secret mecha

nisms of capitalism which provide the key to revolutionary change:

Der Flaneur ist der Beobachter des Marktes. Sein Wissen steht der Geheimwissenschaft

von der Konjunktur nahe. Er ist der in das Reich des Konsumenten ausgeschickte

Kundschafter des Kapitalismus.5

As an observer and connoisseur of market fluctuations and as someone at the

same time on a reconnaissance mission in the consumer's realm, theflcineur pos

sesses the perceptiveness to register all the signs of commodification. Thus his

nineteenth-century view empowers the twentieth-century theorist of moder

nity, who also has an interest in overcoming alienation, to turn into a concrete,

non-theoretical vision the utopian potential inherent in industrial capitalism.

2 See Bernd Witte, Walter Benjamin (Reinbek: Rowohlt, 1985), pp. 68 and 79.

3 Walter Benjamin, 'Die Wiederkehr des Flaneurs', in Gesammelte Schriften, ed. by Rolf Tiede

mann and Hermann Schweppenh?user, 7 vols (Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp, 1991), in, 194-99.

This edition is abbreviated henceforth as GS.

4 'Paris, die Hauptstadt des XIX. Jahrhunderts' (1935, an expos? for the Passagen-Werk), 'Das

Paris des Second Empire bei Charles Baudelaire' (1938), and '?ber einige Motive bei Baudelaire'

(1939). They are available in English translation by Harry Zohn as 'The Paris of the Second

Empire in Baudelaire' and 'Some Motifs in Baudelaire', and by Quintin Hoare as 'Paris?The

Capital of the Nineteenth Century'; all in Walter Benjamin, Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet in

the Era of High Capitalism (London: Verso, 1983).

5 Walter Benjamin, Das Passagen-Werk, in GS, v/1-2, v/i, 537-38. Das Passagen-Werk is avail

able in English translation by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin as The Arcades Project

(Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999).

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARTINA LAUSTER I41

This happens at the precise moment when the ar

such as arcades, gaslight, and panoramas, are bec

Stierle has pointed out: 'Fur Benjamin steht die Er

nicht in einem kontinuierlichen Prozef3 der Wir

ist bezogen auf den privilegierten Augenblick'

I920S and I930S when 'die abgeschiedene Moderne

words, the nineteenth-century fl6neur passes on

dynamic present-'die abgeschiedene Moderne

sopher who re-presents a past present in a mom

thinking in aphoristic images is intended to help

revolutionary transformation.

But this empowerment hinges on the assumption

flaneur's view-however sharp with regard to the

the things he observes-is obscured as by a vei

sight of the later critic to free modernity from t

consciousness of its early observers. Benjamin fo

lightening modernity about itself in terms of w

central image denoting the dream is that of the

ist der Schleier, durch den hindurch dem Flaneu

tasmagorie winkt.'7 The flkneur here views his

not as genuinely 'entfremdet', but as merely 'ver

which is that of the urban crowd. This idiosyn

jamin's allegorical thinking, needs explaining.

of pre-cinematic visual entertainment, a subgenr

where an image was projected onto a diaphanous

projector moved backwards and forwards, creati

Gothic thrill through the illusion of an approach

describing the flineur's vision of the city as pha

that it is clouded by the dream-factory vision e

tainment industry. He indirectly also refers to M

of the commodity in terms of a religious fetish,

status solely to the human brain investing it with

the community venerating the fetish, as an auto

magoric appearance, created by human craft and

of its own, also forms part of Marx's inventory

apparent independence of the commodity, resulti

social relationships producing it:

[D]ie Warenform [hat] [. . .] mit ihrer physischen

genden dinglichen Beziehungen absolut nichts zu scha

gesellschaftliche Verhaltnis der Menschen selbst, w

6 Karlheinz Stierle, Aura, Spur und Benjamins Vergegenw

Art social und art industriel: Funktionen der Kunst im Zeita

Pfeiffer, Hans Robert Jauss, and Fran?oise Gaillard (Munic

7 Ibid., p. 54.

8 See Ulrike Hick, Geschichte der optischen Medien (Munich: Fink, 1999), pp. 146-56; also

Margaret Cohen, 'Benjamin's Phantasmagoria: The Arcades Project', in The Cambridge Companion

to Walter Benjamin, ed. by David S. Ferris (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004),

pp. 199-220 (p. 207).

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I42 Benjamin's Myth of the 'Flaneur'

magorische Form eines Verhiltnisses von Dingen annimmt. Um daher eine Analogie

zu finden, muissen wir in die Nebelregion der religiosen Welt fluichten. Hier scheinen

die Produkte des menschlichen Kopfes mit eignem Leben begabte, untereinander und

mit den Menschen in Verhaltnis stehende selbstindige Gestalten. So in der Warenwelt

die Produkte der menschlichen Hand. Dies nenne ich den Fetischismus, der den Ar

beitsprodukten anklebt, sobald sie als Waren produziert werden, und der daher von der

Warenproduktion unzertrennlich ist.9

Benjamin's flaineur moves in the 'Nebelregion' not so much of a religious world,

but in that of capitalist reification, by perceiving the man-made, familiar city as

a phantasmagoria, an autonomous, potentially fear-inspiring world of objects

independent of himself. Yet the shock that this alienation could impart is mi

tigated by the phantasmagoric screen, the crowd in the street, which shrouds

the familiar, yet alien city in a nebulous tissue. Presumably the implication

is that the urban crowd, itself a potentially disturbing phenomenon, absorbs

the flaneur as one who feels in his element and at home in it, deriving an

aesthetic thrill by moving along incognito, and therefore not (yet) being fully

exposed to the shock of alienation. On the other hand, being at home in what is

definitely not 'home' and viewing what is familiar through a defamiliarizing veil

make Benjamin's flineur an ambiguous figure, partly perceptive of the shifts in

subject-object relationships brought about by industrialization, partly deluded

about them. His greatest delusion is spatial, since he experiences the streets as

an interior, a mixture of shopping arcade, conservatory, living-room, panorama,

music hall, cabinet of curiosities or botanical collection, and Great Exhibition

hall. This interior unites all times, all parts of the globe, and all phenomena of

contemporary society, and their availability in one moment or glance intoxicates

the flineur so that his inner life begins to tick like a clock, signifying a physical

internalization of the world of objects. The following compilation of extracts

illustrates these key points in Benjamin's vision of the flcineur:

Bekannt ist, wie bei der flanerie Lander- und Zeitenfernen [. . ] in den Augenblick

eindringen. Wenn die eigentlich rauschhafte Phase dieses Zustands anhebt, pocht es im

Aderwerk des Gliicklichen, sein Herz nimmt den Uhrtakt an.'"

Die StraBe wird zur Wohnung fur den Flaneur, der zwischen Hiuserfronten so wie

der Buirger in seinen vier Wainden zuhause ist. Ihm sind die gliinzenden emaillierten

Firmenschilder so gut und besser ein Wandschmuck wie im Salon dem Burger ein

Olgemalde; Mauern sind das Schreibpult, gegen das er seinen Notizblock stemmt;

Zeitungskioske sind seine Bibliotheken und die Cafeterrassen Erker, von denen aus er

nach getaner Arbeit auf sein Hauswesen heruntersieht. "

[With reference to the sociological sketches written by journalists of the July Monarchy,

and quoting Eduard Fuchs's work on caricature:] '[. . .] Alles defilierte voriuber . . .

Freudentage und Trauertage, Arbeit und Erholung, Eheliche Sitten und Junggesel

lengebrauche, Familie, Haus, Kind, Schule, Gesellschaft, Theater, Typen, Berufe.' Die

Gemichlichkeit dieser Schildereien paB3t zu dem Habitus des Flaneurs, der auf dem

Asphalt botanisieren geht.'2

9 Karl Marx, Das Kapital: Kritik der politischen ?konomie, vol. i, in Karl Marx, Friedrich

Engels: Werke, ed. by the Institut f?r Marxismus-Leninismus beim ZK der SED, vol. xxm, 7th

edn (Berlin: Dietz, 1972), pp. 86-87.

10 Das Passagen-Werk, GS, v/i, 528.

11 Walter Benjamin, 'Das Paris des Second Empire bei Baudelaire', in Charles Baudelaire: Ein

Lyriker im Zeitalter des Hochkapitalismus, in GS, 1/2, 511-604 (p- 539)

12 Ibid., p. 538.

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARTINA LAUSTER I43

Der Stadter, dessen politische Uberlegenheit fiber das

vielfach zum Ausdruck kommt, macht den Versuch, da

Die Stadt weitet sich in den Panoramen zur Landschaf

spater fur den Flanierenden tut.'3

Die Erscheinung der Straf3e als Interieur, in der die P

zusammenfaf3t, ist von der Gasbeleuchtung nur schw

brannte in den Passagen.'4

Benjamin thus creates an interdependency betwee

cise registering of a nineteenth-century environ

by an unprecedented process of 'Verdinglichun

tory mental state on the other hand. He clearly

fetishization-a term which he, psychologizing th

as the endowment of inanimate things with sex-

the city dweller's anxieties and desires. The fldn

world of commodities and his position in the com

in an equally ambiguous manner so as to highlight

type one who has the potential, but not the illus

his own commodification:

als Flaneur begibt [... .] sich [der Literat] auf den Markt

und in Wahrheit doch schon, um einen Kaufer zu fin

The idea of the writer/flaneur's unconscious prost

is then heightened by the image of entering

tertainment in which the writer/viewer/flaneur

determined, partial vision to an illusion of total

Der Schriftsteller, der den Markt einmal betreten hat

Panorama. '8

The nexus between fljneur and modern writer or

Baudelaire long before Benjamin, with similar acc

its thrills. Indeed, following Benjamin's essays on

knowledge associates the conceptual origins of the

firmly with Baudelaire,'9 that is to say, with his

Poe's story 'The Man of the Crowd' and with his c

Constantin Guys. One of the most famous passag

13 Das Passagen-Werk, GS, v/i, 48.

14 'Das Paris des Second Empire bei Baudelaire', p. 552.

15 See Hartmut B?hme, 'Fetischismus im neunzehnten Jahr

Analysen zur Karriere eines Konzepts', in Das schwierige neun

Tagung zum 65. Geburtstag von Eda Sagarra im August igg8, e

and Roger Paulin (T?bingen: Niemeyer, 2000), pp. 445-65 (

16 'Die Mode schreibt das Ritual vor, nach dem der Fetisc

verkuppelt den lebendigen Leib der anorganischen Welt. [

Appeal des Anorganischen unterliegt, ist ihr Lebensnerv' (Wa

des XIX. Jahrhunderts', in Das Passagen-Werk, GS, v/i, 81

17 'Das Paris des Second Empire bei Baudelaire', p. 536.

18 Ibid., p. 537.

19 See the Wikipedia entry 'Fl?neur', which attributes not

type to Baudelaire, but even the Benjaminian phrase describin

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fl%C3%A2neur) [accessed 10

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I 44 Benjamin's Myth of the 'Flaneur'

de la vie moderne', in which Baudelaire discusses 'The Man of the Crowd' in

the context of Guys's work, celebrates self-loss in the crowd as a precondition

of artistic creativity. Benjamin includes this passage in his collection for the

Passagen- Werk:20

Pour le parfait flaneur, pour l'observateur passionne, c'est une immense jouissance que

d'e1ire domicile dans le nombre, dans l'ondoyant, dans le mouvement, dans le fugitif

et l'infini. Etre hors de chez soi, et pourtant se sentir partout chez soi; voir le monde,

etre au centre du monde et rester cache au monde, tels sont quelques-uns des moindres

plaisirs de ces esprits independants, passionnes, impartiaux, que la langue ne peut que

maladroitement definir. L'observateur est un prince qui jouit partout de son incognito.

[. . .] C'est un moi insatiable du non-moi, qui, a chaque instant, le rend et l'exprime en

images plus vivantes que la vie elle-meme, toujours instable et fugitive.2'

It is well worth pointing out that this passage refers entirely to the 'painter of

modern life', Constantin Guys, and that Baudelaire at no point associates the

fldneur with the unknown 'man of the crowd' espied by the narrator in Poe's

story. The reason Baudelaire enhances his essay on a visual artist by referring

to a narrative work is the fresh, unconditioned perception of the people in the

street that Poe's narrator, in Baudelaire's view, shares with Guys. Yet to see the

object of the narrator's vision, the 'man of the crowd', as a flaneur is absolute

nonsense; if anything, it is the observing narrator who could be labelled thus.

Benjamin, however-as John Rignall has pointed out22-contrives the glaring

misinterpretation of Poe's hunted, unknown man as a fldneur. The 'man of

the crowd' becomes identical for him with 'the' flaneur at an advanced stage in

his development, just as, Benjamin claims, Baudelaire saw him in Poe's story,23

i.e. as the bohemian outcast hiding in the crowd, moving in the jungle of the

city, and succumbing in the end to the lure of commodities in the jungle of a

department store. Hence posterity has become accustomed to thinking of Poe

and Baudelaire as twin names with regard to the flaneur, i.e. the 'man of the

crowd'. This is one particularly persistent facet of the Benjaminian myth of the

flaneur which I want to address.

Benjamin's carelessness with regard to his sources, conducive to myth

making, does not end here. When he eventually realizes that Poe's protagonist

is not a flineur, he corrects himself in his second essay on Baudelaire ('Uber

einige Motive bei Baudelaire'), but corresponding statements in the Passagen

Werk have been left unchanged, such as:

Dialektik der flanerie: einerseits der Mann, der sich von allem und allen angesehen

fiihlt, der Verdichtige schlechthin, andererseits der vollig Unauffindbare, Geborgene.

Vermutlich ist es eben diese Dialektik, die 'Der Mann der Menge' entwickelt.24

20 Das Passagen-Werk, GS, v/i, 556.

21 Charles Baudelaire, 'Le peintre de la vie moderne', in uvres compl?tes, ed. by Claude Pichois,

2 vols (Paris: Gallimard, 1975-76), 11 (1976), 683-724 (pp. 691-92).

22 See John Rignall, Realist Fiction and the Strolling Spectator (London and New York: Rout

ledge, 1992), p. 13.

23 '[. . .] ein Unbekannter, der seinen Weg durch London so einrichtet, da? er immer in ihrer

[=der Menge] Mitte bleibt. Dieser Unbekannte ist der Flaneur. So ist er von Baudelaire auch

verstanden worden, als er in seinem Guys-Essay den Flaneur "l'homme des foules" genannt hat'

('Das Paris des Second Empire bei Baudelaire', p. 550).

24 Das Passagen-Werk, GS, v/i, 529.

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARTINA LAUSTER I45

It is also worth pointing out the inconsistency

interpretation when he reaches the discussion

culmination-point of his chapter on the flaine

Second Empire bei Baudelaire'. Here he asserts

one wrongly identified by him as aflkineur), wh

department store, has lost his way in the labyrin

earlier type of flineur had lost his way in the laby

Wenn die Passage die klassische Form des Interieurs

Flaneur darstellt, so ist dessen Verfallsform das Wa

letzte Strich des Flaneurs. War ihm anfangs die Straf

wurde ihm dieses Interieur nun zur Stral3e, und er irrt

vordem durch das stadtische. Es ist ein groBartiger Zu

friihesten Schilderung des Flaneurs die Figur seines E

Seeing the flineur epitomized in Poe's 'man of

labyrinth of merchandise as he was before in the

jamin flatly contradicts his former assertion abo

familiar, homely spaces by the flineurs of Paris.

to imply that these strolling observers (represent

before I840) constituted an 'initial' version if P

story first published in I840) is deemed both t

the type and an anticipation of his demise in the

of capitalism. Unconcerned by either of these con

reiterates his point about exterior spaces being t

flaneur, arguing that while the arcades had repre

environment as which the street offered itself to

which the arcades are degenerating now becomes

of streets for him, as the city had been to him befor

twists, theflaineur is represented as offering himself

turned into interior) and in the department store

as a commodity to any interested buyer; unconsc

implied expression 'auf den Strich gehen' sugg

for the associative freedom of Benjamin's though

called that-is simply absurd, though it has not p

being turned into interiors and urban observers p

market from becoming part of the critical canon.

How reliable, one wonders, is Benjamin's whole c

25 'Das Paris des Second Empire bei Baudelaire', p. 557.

26 The idea of a fl?neur turning exteriors into interiors appe

'Nineteenth-Century Urban Sketches: Thresholds of Fictio

'Many [. . .] urban sketches contain the presence [. . .] of a

if he were to depict only the publicly observable life of the

Benjamin notes, turn the exteriors into interiors, impart to the

forms of external urban life potentially available' (p. 236). Th

sketches whose lightness of touch masks his commodified bus

'Effortless Art: The Sketch in Nineteenth-Century Painting

349-64, where she deals with Washington Irving's introduc

Crayon (1820): 'His "sauntering gaze" makes him a perfect

wanders through the city streets, apparently a man of leisure

a "strolling commodity"' (p. 354).

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

146 Benjamin's Myth of the 'Flaneur'

is not only self-contradictory, but has no solid foundation in Poe's or Baude

laire's work either? Let us first recapitulate the main qualities of the icon of

modernity that the flaeneur has become through Benjamin's writings. He is a

type that prefers arcades and gaslight, looks at the city as if it were a panorama

or indeed a phantasmagoria, turns the boulevard into an interieur, collects

urban physiognomies like a botanist collecting specimens, and, as a 'Literat'

prostituting himself on the market, shows an affinity with the commodities he

gazes at in window displays. This icon, for sure, is not a type that ever existed

in social history, but a literary reflection of a complex kind, resulting from a

triple reading (or misreading) process from Poe via Baudelaire to Benjamin.

Benjamin, as John Rignall has remarked, himself invests an epistemological

figure Baudelaire's 'observateur passionne' denoting a manner of viewing

with the qualities of a material type, expressive of developments in the era of

High Capitalism.27 By virtue of the flaneur's sturdy afterlife in cultural studies,

where he occupies the place of a type, a nineteenth-century literary cipher of

vision has thus become a myth, i.e. something that is believed to have materially

existed.

Benjamin cannot be held responsible for what posterity has done with his

ideas, but the myth of the flatneur can be seen as a direct result of his own habit

of condensing conceptual understanding into idiosyncratic images. His inten

tion to strip nineteenth-century modernity of its fetishist veil has backfired

in the sense that the phenomena he discusses (arcades in particular) and his

highly imaginative way of interpreting them have themselves, paradoxically,

acquired iconic status in contemporary cultural and literary studies. In Hart

mut B6hme's terminology, these contemporary critics are trapped in a process

of unintentional 'fetishization' which already bedevilled the work of their cri

tical models, from Marx via Nietzsche to Freud, the very thinkers who drew

attention to fetishist phenomena in enlightened Western societies:

Der Fetischismus, der dem Kapitalismus einwohnt oder auch ihm nur imputiert wird,

prigt sich der Kritik in seltsamen Inversionen auf. Die obskure koloniale Herkunft des

Fetischismus-Konzepts implantiert ins Denken eine fatale Bindung ans Objekt, welches

doch iuberschritten werden soll. Die Geste der Kritik bleibt beherrscht durch eine Art

religiosen Bann. [. . ] Philosophie wird zum Ikonoklasmus. [. . .] Diese kritische Wucht

aber setzt sich bei Marx wie bei Nietzsche, und spater auch in der Psychoanalyse, in eine

Bewegung um, welche zur Kreation neuer Idole und Fetische fiihrt, deren Bannkraft

im zwanzigsten Jahrhundert vielleicht alles iibertrifft. (Bohme, p. 465)

I would not go so far as to describe an uncritical adoption of Benjamin's 'idol'

of the flineur as fetishistic, but the way in which nineteenth-century depictions

of metropolitan viewing have acquired typological solidity in the form of 'Ben

jamin's flaneur' certainly resembles the process of fetishization in criticism as

analysed by Bohme. My own critical intention is therefore not to attack the

fetish, since this only confirms its iconic status, but to counteract myth-making

through an examination of texts-Benjamin's own as well as those he draws on.

27 'The fl?neur is seen here as a social phenomenon, the object of the materialist historian's

gaze rather than the exponent of a certain kind of vision, the seeing subject himself (Rignall,

p. 14). In this context Rignall also refers to Adorno's early critique of Benjamin's first essay on

Baudelaire, focusing on the lack of 'mediation', 'the very mediation that the concept of the fl?neur

as representing a way of seeing provides'.

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARTINA LAUSTER I47

For the myth of the flineur has blocked critical path

source materials that fall within the remit of the Pa

to unblock our approaches to documents of ninetee

tion, which is tantamount to removing the phantasm

interpretation itself has drawn over them. Benja

Parisian sketches of the i83os and i840s in the Pa

them in his essays. They include the Physiologies, a

illustrated booklet depicting social types and pheno

swamping the Parisian book trade between i 840 an

hints at the fact that physiology and zoology were p

early days of sociology, and that the empirical scie

methodological framework from the sciences of lif

These sketches show that the interest of urban ob

other hybrids between exterior and interior spaces,

other hand, street life proper, particularly modes of

attracts the highest interest. Benjamin, while amassi

in the Passagen-Werk, says almost nothing about th

laire and Paris. Moreover, the sketches prove that the

as both a social type and a cipher of modern vie

a number) was part of common knowledge as ear

thus not first conceptualized by Baudelaire in his

I859-60, first published in I863), but much earli

give the flaineur a meaning which significantly diff

concept of the Second Empire, in other words, t

ited from Baudelaire and Benjamin. Rather than

demonic, prince-like, man-of-the-world artist, they

city-dweller, a Mr Anybody, in other words, as preci

the 'man of the crowd' celebrated in Baudelaire's eu

tic reflection. Richard Burton has categorized this

the pre- and the post-I850 incarnation of the flineu

'roving empiricist' and to the latter as 'little less tha

Whereas the pre-I850flaneur strives to understand the in

otherness, the homme desfoules, as described by Baudelair

quasi-mystic (or quasi-orgasmic) fusion with 'la foule' con

and anonymous mass.28

This difference could also very probably be seen as

cursive, non-fictional treatment of the new social t

'visionary' transformation in prose fiction as well as

aesthetics. Why does Benjamin, the materialist h

aesthetic variant for his own theoretical conclusion

does he include the early journalistic sources in the

Passagen-Werk, but dismiss them as of little intrin

essays? Because journalism is unproductive in terms

sion, which ultimately has to rely on the 'Kunstwe

28 Richard D. E. Burton, The Fl?neur and his City: Patterns

(Durham: University of Durham, 1994), p. 5.

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I48 Benjamin's Myth of the 'Flaneur'

metropolitan fiction-conveying the shock effect of modernization. Benjamin

sees the whole genre of quotidian sketches, subsumed by him under the broad

heading of feuilleton, as a sedative for the middle class, i.e. as socially and ideo

logically suspect and therefore unreliable:

Die beruhigenden Mittelchen, welche die Physiologisten [writers of Physiologies] feil

hielten, waren bald abgetan. Der Literatur dagegen, die sich an die beunruhigenden

und bedrohlichen Seiten des stiidtischen Lebens gehalten hat, sollte eine grof3e Zukunft

beschieden sein. Auch diese Literatur hat es mit der Masse zu tun. Sie verfahrt aber

anders als die Physiologien. Ihr liegt an der Bestimmung von Typen wenig; sie geht

vielmehr den Funktionen nach, welche der Masse in der groBen Stadt eigen sind. [ ...]

Hier erscheint die Masse als das Asyl, das den Asozialen vor seinen Verfolgern schutzt.

Unter ihren bedrohlichen Seiten hat sich diese am zeitigsten angekiindigt. Sie steht im

Ursprung der Detektivgeschichte.29

Der urspriingliche gesellschaftliche Inhalt der Detektivgeschichte ist die Verwischung

der Spuren des Einzelnen in der Grof3stadtmenge.30

Benjamin here assigns aesthetic durability and hence quality to 'Literatur' in

the form of the detective story (to which he unscrupulously also subsumes

Poe's 'Man of the Crowd', as a kind of 'X-rayed version' of the genre)3' and

declares the Physiologies written by journalists to be transitory and therefore

worthless. Since detective fiction engages with the phenomenon of masses in a

way that does justice to the unsettling experience of the individual's anonymity

and loss of moral ties in the 'asylum' of the crowd, it points forward to the

twentieth century, even if it is itself part of the nineteenth-century fldneur's

delusion.32 This seemingly avant-gardist, but in fact quite conventional value

judgement is predicated on the devaluation of entertaining journalism-the

typological portrait written for the day-as a genre providing something more

dubious than phantasmagoric illusion, in other words, opiatic medicine ('Mit

telchen'). In Benjamin's view, it numbs the authentically experienced anxieties

of readers in an increasingly threatening urban environment. The non-fictional,

witty proto-sociological study of type is thereby denied any cognitive capacity.

This problematic judgement is informed by the suspicious attitude of Ger

man Kulturkritik towards the 'billige Eleganz' of the feuilleton,33 even though,

paradoxically, journalism and its ruses (such as recycled aphorisms) very often

provide the very medium in which this cultural criticism is expressed.34

Kai Kauffmann has noted the tendency to see the newspaper press as the

'letzte Verfallsform' of narrative communication in Benjamin's criticism of the

29 'Das Paris des Second Empire bei Baudelaire', p. 542.

30 Ibid., p. 546.

31 'Poes ber?hmte Novelle "Der Mann der Menge" ist etwas wie das R?ntgenbild einer Detek

tivgeschichte. Der umkleidende Stoff, den das Verbrechen darstellt, ist in ihr weggefallen' (ibid.,

P 55o):

32 With reference to works such as Dumas's Mohicans de Paris, Benjamin writes: 'Welche Spur

der Flaneur auch verfolgen mag, jede wird ihn auf ein Verbrechen f?hren. Damit ist angedeutet,

wie auch die Detektivgeschichte, ihres n?chternen Kalk?ls ungeachtet, an der Phantasmagoric

des pariser Lebens mitwirkt' ('Das Paris des Second Empire bei Baudelaire', p. 543).

33 See ibid., p. 529.

34 One striking example of Benjamin's own recycling can be seen in the image of the street as an

int?rieur which appears in his 1929 review of Hessel's Spazieren in Berlin ('Die Wiederkehr des

Flaneurs', GS, in, 194-99 (p. 196)) as well as, almost verbatim, in Das Passagen-Werk, GS, v/i,

533, and 'Das Paris des Second Empire bei Baudelaire', p. 539.

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARTINA LAUSTER I49

Physiologies and the press.35 This devaluation of

mann argues, is part of a selective reading proces

in turn has established a Benjaminian 'myth of m

Benjamin gewinnt an Baudelaires Schriften die Beg

der modernen Grof3stadt prigen: Begriffe wie Reiziibe

Sinn-Verlust, Entfremdung, Diskontinuitat etc. Trotz

Hans Robert Jaul3 [in Literaturgeschichte als Provoka

Schriften 'einseitig als Zeugnis fur das denaturierte D

interpretiert und dariiber die dialektische Kehrseite de

sage an die Natur freigesetzte, neue Produktivkraft d

Benjamins Interpretation fulr die neuere literaturwis

dernen Grof3stadt maf3geblich geworden. Baudelaires

Kritiken sind in Benjamins Lesart zu den wichtigst

der modernen GrofBstadt avanciert, die von der Liter

Ersch6pfung bemiiht werden. [. . .] Auf diese Weise e

raturwissenschaftliche 'Mythos der Moderne'. (Kauffm

With regard to literary studies, this myth means

'beunruhigend' and 'bedrohlich' constitutes th

of nineteenth-century urban depiction is meas

to be 'beruhigend' and 'harmlos' (Benjamin's co

noted epithets) must be aesthetically worthless a

raises the question as to why critics following B

listic city sketches at all, if the only insight they

of their superficiality; often, of course, also the

Benjamin's reading, combined with a notion o

cault, makes it possible to dismiss the whole gen

make a threatening urban environment controllab

in particular serves as a most convenient instrum

nineteenth-century specialists or cultural theoris

as critical interpreters. One example is Richard

lition of the Physiologies published in I985. For h

is their 'perfect harmlessness', which allows him

is fundamentally petit-bourgeois, virtually lacki

insight'.3 Without further ado, arcades are decla

innocuous social botanizing is practised by the fl

mass-produced Physiologies then have the plea

social botanists and as viewers who can move aro

about others without being laughed at-but, little

victim to a cosmic phantasmagoria:

35 See Kai Kauffmann, 'Es ist nur ein Wien!' Stadtbeschr

Geschichte eines literarischen Genres der Wiener Publizistik (

1994), PP- 27-28.

36 The reference to Jauss's Literaturgeschichte als Provokat

a.M.: Suhrkamp),p. 58.

37 Richard Sieburth, 'Une id?ologie du lisible: le ph?nom?ne

(T985), 39-60: 'Comme Walter Benjamin fut le premier ? le m

la parfaite bonhomie de la satire contenues dans les physiolog

damentalement petit bourgeois, virtuellement d?pourvu de v

38 See Benjamin's statement on the 'Habitus des Flaneurs

geht' ('Das Paris des Second Empire bei Baudelaire', p. 538).

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I50 Benjamin's Myth of the 'Flaneur'

Acheter une physiologie c'est donc se procurer un acces indirect a toutes les prerogatives

de la flanerie: oisivete, curiosite, ubiquit& et par dessus tout la certitude que la ville peut

etre connue et maitris&e comme un jeu pred&termine de signes ... .]. ... .] Le succes de

cette 'litterature panorama' de l'6poque a sans doute quelque rapport avec l'assurance

de pouvoir voir sans etre vu. Un reve semblable d'invulnerabilite [. . .] est sous-jacent

au mecanisme renconfortant de la satire dans les physiologies, car il rend leurs lecteurs

capables de jouir de la superiorite (diabolique, comme le dirait Baudelaire) du rire sans

etre eux-memes impliques comme cibles du ridicule. (Sieburth, pp. 57 and 58)

[Les physiologies] iraient finalement moins dans le sens d'une apprehension de la realite

sociale que vers son occultation systematique dans ce que Walter Benjamin nomme

'l'univers d'une fantasmagorie'. (p. 46)

This regardless of the fact that the physiologies are a parodistic genre,39 poking

fun at the more 'serious' sketch collections, such as the serial Les Franfais peints

par eux-memes (I839-42), and their exercises in social classification. Nor does it

in the least take account of the fact that these socially classifying sketches, which

the physiologies parodistically respond to, created a portrait of the metropolis

in collections of hundreds of individual contributions-not dissimilar, in fact,

to Benjamin's own synthetic picture of modernity in the Passagen-Werk, 'ein

Bild des i9. Jahrhunderts [. . .], das die Leuchtkraft des Traums oder der

unwillkiirlich sich 6ffnenden Erinnerung hat' (Stierle, p. 39), which is com

posed of hundreds of (usually discursive) fragments. Benjamin himself draws

the analogy between sketch collections and huge circular paintings by describ

ing them rightly as moral panoramas, but this analogy does not do them jus

tice if, as he and his followers believe, they merely replicate the entertaining

and informative medium of the visual panorama.40 The cognitive claim, for

example, of Les Franfais peints par eux-memes to synthesize an Encyclopedie

morale du XIXe siecle (thus the serial's subtitle from Volume iv onwards) from

a vast number of individual typological sketches is as serious as that of the

Passagen-Werk to construct an 'Urgeschichte der Moderne' from scraps. Ac

cording to Stierle, Benjamin reads the nineteenth century in such a way 'daB

aus Detail und Bruchstiick immer neue Bilder und Konstellationen entstehen.

[.. .] Fur diesen Bricolage des historischen Sinns ist alles brauchbar: Zeitungen,

ephemare Schriften, Plakate, die abgelegensten Buicher wie die groBe Literatur'

(Stierle, p. 40). I would argue that, since collections such as Les Franfais peints

par eux-memes construct proto-sociological 'encyclopaedias' of the nineteenth

century from observation (including observations of seemingly insignificant

trivia, of the observer himself as well as of media of observation and popu

lar entertainment), their cognitive value for a concept of modernity is in fact

39 As Nathalie (Basset-)Preiss already pointed out in 1984: N. Basset, 'Les physiologies au xixe

si?cle et la mode: de la po?sie comique ? la critique', Ann?e balzacienne (1984), 157-72; and as she

has amply demonstrated in her book: N. Preiss, Les Physiologies en France au XIXe si?cle: ?tude

historique, litt?raire et stylistique (Mont-de-Marsan: ?ditions InterUniversitaires, 1999).

40 Benjamin says that the 'panoramatische Literatur' of the sketch collections (e.g. Le Livre des

Cent-et-un, Les Fran?ais peints par eux-m?mes, Le Diable ? Paris, La Grande Ville) enjoyed the

same popularity as the visual panorama and worked with similar devices: 'Diese B?cher bestehen

aus einzelnen Skizzen, die mit ihrer anekdotischen Einkleidung den plastischen Vordergrund

jener Panoramen und mit ihrem informatorischen Fundus deren weitgespannten Hintergrund

gleichsam nachbilden' ('Das Paris des Second Empire bei Baudelaire', p. 537); see also the section

'Panorama' in Das Passagen-Werk, GS, v/2, 655-65 (p. 659), with a characteristic imprecision in

terminology: 'Sie sind gewisserma?en moralische Dioramen'.

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARTINA LAUSTER I51

PAR E.UX-MI11MIIS.

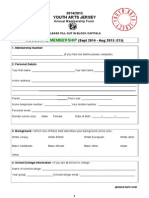

FIG. i. Lavieille after Gavarni, frontispiece in Les Franfais peints par

eux-memes, 8 vols (Paris: L. Curmer, I840-42), ii (i840). Wood engraving.

superior to Benjamin's idiosyncratic picture constructed from prejudiced and

incorrect readings of texts.

From these sketches a reading of modernity in terms of a dynamic public

sphere becomes possible which differs fundamentally from Benjamin's. More

over, modernity is not something that only a present-day reader would be able

to reconstruct from sketch collections of the I 830s and I 840s, but it is their own

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I152 Benjamin's Myth of the 'Flhneur'

self-conscious point of reference, as Gavarni's frontispiece to Volume ii of Les

Franfais peints par eux-memes makes strikingly clear. An allegorical, angelic

demonic figure viewing him(?)self in a mirror while writing is seated on a pile

of books which can be identified as works of the great moralists (La Bruyere's

name is legible on one of the spines). The figure can thus be seen as an allegory

of the modern sketch-producer, engaged in adding live, present-day moral ob

servations collected in notebooks to those of literary history bound in books.

The main difference between historical, 'pre-modern' moral observation and

the kind of sketches the reader will find in the present collection, however, is

their apparent immediacy, capturing the here-and-now in an unprecedented

interplay between writing and drawing or letterpress and graphic image. The

fact that Les Franfais peints par eux-memes is an illustrated work can be gleaned

from the poster advertising the series in the background and the 'graffiti' of

Parisian types below. On close inspection of the way the sketch-writer holds

the mirror, the viewer becomes aware that what is reflected in it must be more

than the writer's face and include images of his environment, i.e. the kind of

urban scenes that become the subject of sketches. The wall with its poster and

graffiti would be just one of this sort. The very medium of reproduction of

fers a 'mirror image' of the artist's drawing, as Gavarni's reversed signature

implies. Sketches thus present themselves not as naive and spontaneous depic

tions, but as a sophisticated genre working with reflections, and these reflections

include the medial conditions under which the genre operates, such as print

on an industrial scale, the collaboration of many in drawing the self-images of

the nation, and the continuity-through print-of the moralist tradition. The

composite nature of the figure, uniting angel, devil, and fool in a gesture of

vanity, hints at the old theatrum mundi and, at the same time, indicates the

loss of authenticity in a world of reproduction and commodification-a world

which Les Franfais, a publisher's commercial enterprise in the first instance,

eminently represents. Benjamin could have found a prime example here of how

modernity is 'critiqued' by a medium he deems incapable of penetrating vi

sion. Accepting in one's own creations the 'Zertriimmerung der Aura', which

Benjamin sees as the heroic achievement of the lyric poet Baudelaire, is surely

also Gavarni's achievement, but it lacks heroism and therefore iconic potential

because it is an acceptance without communicating a 'Chocerlebnis'.4'

The way in which panoramic (or encyclopaedic) sketch collections present

their views of the city can often be described as an inversion of the traveller's

view of foreign places in a critical self-inspection of the social body. Their syn

thetic structure responds to the increasingly diversified environment in which

social sign-reading has to be practised. In this context, the flaneur emerges

as one of a countless number of ordinary city-dwellers who read metropolitan

41 In Nietzsche's terms borrowed by Benjamin, Baudelaire has achieved modern astral status,

the status of a star without an 'aura' or atmosphere: '[Baudelaire] hat den Preis bezeichnet, um

welchen die Sensation der Moderne zu haben ist: die Zertr?mmerung der Aura im Chocerlebnis.

Das Einverst?ndnis mit dieser Zertr?mmerung ist ihn teuer zu stehen gekommen. Es ist aber

das Gesetz seiner Poesie. Sie steht am Himmel des zweiten Kaiserreiches als "ein Gestirn ohne

Atmosph?re" [Nietzsche, Unzeitgem??e Betrachtungen]' (Walter Benjamin, '?ber einige Motive

bei Baudelaire', in Charles Baudelaire: Ein Lyriker im Zeitalter des Hochkapitalismus, GS, 1/2,

509-690 (p. 653)).

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARTINA LAUSTER I53

surfaces-a far cry from the prince moving abou

kicks out of the experience. One publication of

dismissively is the collective serial Paris, ou Le L

It features a sketch of theflaneur which reads in

of its time. The type is described as able to sh

tions of their surroundings:

Rien n'echappe a son regard investigateur [. . .], tout

texte d'observations. [... .] Sous quel aspect inattendu

demonstrateur, le panorama mobile qui vous environn

Unlike Benjamin's assertion that the medium of th

illusionary veils through which the flaineur view

it clear that the readers are thought to perceive

terms of a 'mobile panorama'. Mobile panoram

used in stage shows of the i82zos, which depic

Champs Elysees and were run across the prosc

had the impression of moving themselves.43 The

presenter who teaches the audience to take a fre

to see through the 'veil', as it were, of a popular

vironment, and thereby doing precisely the oppo

'unusual' angle from which to view the city is th

servation, and its medial paradigm is not the pan

Sketches self-reflectively demonstrate their own

over popular optical media, uniting as they do

phering in the immediacy of reading, which is ta

of the signs on the page.44 Semiological decoding

therefore the business of urban depiction in t

Burton's comments on the flaineur make abunda

To describe the flaneur as a semiologist avant la lettr

into the past preoccupations of the present. On the co

consisted of a multiplicity of interlocking semiotic sy

city was, by definition, meaningful was so widesprea

Paris as to be virtually platitudinous [. . .]. (Burton, p

Reading surfaces was one thing; another was the

of interlocking semiotic systems' which no singl

available. The interpreter of signs was therefore

tiplicity' of readers engaged in the same business

author of the sketch 'Le flaneur a Paris' in the (al

des Cent-et-un is himself listed as 'un flaneur'. An

42 Un fl?neur, 'Le fl?neur ? Paris', in Paris, ou Le Livre des

1831-34), vi (1832), 95-110 (pp. 101 and 102).

43 See Bernard Comment, The Panorama, trans, by Anne

1999), PP 63-65.

44 Two better-known examples are Dickens's 'Rapid Diora

Italy (London: Bradbury & Evans, 1846), and Balzac's 'Histo

Paris', from the second volume of Le Diable ? Paris (Paris:

of these can be found in my forthcoming book Sketches o

Journalism and its 'Physiologies', 1830-50 (Houndmills, Bas

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I54 Benjamin's Myth of the 'Flaineur'

a Baudelairean 'man of the crowd', but the new social type. The portrait of the

professional decipherer of the city by a professional decipherer, in a collective

medium which is itself characteristic of the changing social fabric of the July

Monarchy, therefore possesses the highest cognitive interest both for writers

and the reading public at the time and for nineteenth-century specialists today.

Like the other journalistic collections following in its wake,45 the Livre des

Cent-et-un presents the fl?ineur as a new type whose existence is defined by

externality, by abandoning private space and moving in the streets as well as by

extroverting meaning which used to be hidden so that it becomes accessible in

urban physiognomies. The flaineur is thus also, from the start, a cipher for the

deciphering view which thrives in its proper environment, the urban crowd.

This crowd is not to be understood as an object which the flaineur and the

reader of a physiological sketch need in order to reassure themselves of their

diabolical superiority as decipherers. Nor are they, from an ostensibly secure,

static, unseen position, able to laugh about the other, as Sieburth argues, follow

ing Baudelaire's theory of laughter and indirectly Benjamin's and Baudelaire's

view of the princely observer enjoying his incognito here (Sieburth, p. 58). The

fantasy of seeing without being seen is exactly that of the i820S 'swell' observ

ing the city from the 'snugness' of a camera-obscura viewer, as in Pierce Egan's

Life in London (I 820-2 I).46 Contrary to this perspective, the I830s observer is

included in the crowd as its reflective viewing device, and the same technique

of 'reading externality' that he applies to the city needs to be applied to him as

a type. Social anatomy, in other words, has passed to collective ownership.

The sketch portraying the flineur in the sixth volume of the Livre says that

it is unnecessary to catch a glimpse of the domestic secrets of the professional

stroller. Why? Because he has none. His ambience is the public sphere, and

in order to understand him you need to watch him move about the streets.

The type whose definition it is to be outside reading surfaces is himself crying

out to be deciphered as a meaningful external phenomenon, and the author of

the sketch is significantly named 'un flaneur'. 'Nothing', we learn, 'escapes his

investigative gaze' as he moves forward 'in the middle of the crowd of which he

is the centre'-not an unseen centre of power, but a recognizable type on whose

reflections the seen world centres. This type, himself subject to analysis, is pre

sented as an integral part of the general 'movement' on which his vision vitally

depends. From the latest display of luxury and lithographs in shop windows

to the progress of a building forever under construction, and a never-seen face,

'everything is to him a text of observation'.47 This compulsive sign-reading is

45 Apart from Les Fran?ais peints par eux-m?mes, they include serials such as Nouveau tableau

de Paris au XIXe si?cle, 7 vols (Paris: Librairie de Madame Charles-B?chet, 1834-35); Mus?um

parisien (Paris: Beauger and Aubert, 1841); La Grande Ville, 2 vols (Paris: Maresq, 1844); Le

Diable ? Paris, 2 vols (Paris: J. Hetzel, 1845-46); and others.

46 '[. . .] safety [. . .] should be the primary object of the traveller. The curious, likewise, in their

anxiety to behold delightful prospects or interesting views, ought to be equally careful to prevent

the recurrence of accidents. The author, in consequence, has chosen for his readers a Camera

Obscura View of London, not only from its safety, but because it is so snug, and also possessing

the invaluable advantages of seeing and not being seen' (Pierce Egan, Life in London; or, The Day

and Night Scenes of Jerry Hawthorn, Esq. and his Elegant Friend Corinthian Tom [. . .], 3rd issue

(London: Sherwood, Jones & Co., 1823), p. 18).

47 'Le voyez-vous mon fl?neur, [. . .] comme il s'avance librement au milieu de cette foule dont

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARTINA LAUSTER I55

further described as a phenomenon and actually

tion at an advanced, 'aged' ('vieillie') stage. Becaus

division of labour, the flaneur has a single occupati

see everything, like his ancestor, the serpent of Pa

towards knowing and exposing becomes 'useful' ('ut

cause the observer is himself part of the crowd cul

enjoying the privilege of diabolical insight, he shar

interested and by virtue of having his portrait, wr

stroller, published in a collective volume. 'Harmless

jamin remarks with regard to all the types analysed

beside the point. What matters centrally is the fact

privileges attached to it, not even those of 'great li

of the Livre des Cent-et-un, this heir of Satanic vis

general, an emeritus professor, a former merchant

off duty'."5 As he hardly ever leaves his own quart

tant and every regular' ('chaque habitant et chaque

and he is himself known to the staff in all the rest

mid- i84os the suggestion of personal acquaintanc

his environment will have gone. However, even the

the fkaneur as being in his element on the street is

making a threatening environment look familiar, bu

the penetration of surfaces.

To conclude, streets are definitely not turned into

servers of the i83os and I840s. Although the flaneu

who has abandoned his private space, this does n

experienced as 'familiar' instead. The dwindling o

more fruitful concept for an understanding of so

of observation during the period in question. The w

form social anatomy suggests a turning inside out,

private, internal spaces, rather than a turning outsid

of public, external space. In the same context one c

a perception of the urban environment as nature (s

the panorama to landscape and of theflaneur to a b

notations that are alien to the observers of Parisian

il est le centre [. . .]! Tout, autour de lui, ne para?t marcher, co

ses yeux, provoquer ses r?flexions, animer son existence de ce

languit. Rien n'?chappe ? son regard investigateur: une nouve

magasin somptueux, une lithographie qui se produit pour la pr

d'une construction qu'on croyait interminable, un visage inacc

texte d'observations' ('Le fl?neur ? Paris', p. 101).

48 See ibid., pp. 96-98.

49 'Nirgends durchbrachen diese Physiologien den beschr?nkte

den Typen gewidmet hatten, kam die Reihe an die Physiologie

nuit", "Paris ? table", "Paris dans l'eau", "Paris ? cheval", "Pari

auch diese Ader ersch?pft war, wagte man sich an die "Physiolo

die "Physiologie" der Tiere, die sich seit jeher als harmloser Vo

Harmlosigkeit kam es an' ('Das Paris des Second Empire bei Ba

50 '[. . .] un g?n?ral en retraite, un professeur ?m?rite, un an

disponibilit?' ('Le fl?neur ? Paris', p. 100).

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I156 Benjamin's Myth of the 'Flineur'

urban environments in terms of natural history, but only inasmuch as 'life sci

ence' (anatomy, physiognomy, zoology, and physiology) is a paradigm for social

science. No Physiologie or related publication would at any point suggest that

a place shaped by human history is to be understood as natural space. This

kind of understanding, which does also exist in metropolitan sketches, has, as it

were, an axe to grind. It is a reactionary view formulated against the Western,

historical, and dynamic interpretation of the city, as becomes evident from a

Viennese panoramic collection, Wien und die Wiener.5' But even this collection

engages with the process of sign-reading in a democratized and everyday sort of

way. The light in which the sketch industry of the I83os and I840s needs to be

interpreted is that of the Enlightenment project making its way into quotidian

knowledge on a massive scale. This happens thanks to the very progress of

reproductive technologies (such as the use of stereotypes for reproducing texts

and images quickly and cheaply, and in high print-runs, on the steam-powered

press) that prepare the ground for the 'post-auratic' forms of art of photo

graphy and film. While Benjamin appreciates their revolutionary potential in

'Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit', he denies

such a capacity to the mass-produced illustrated sketch, not a 'Kunstwerk', but

a form that nevertheless points to its own reproducibility in such a way as to

imply a critique of modernity. Benjamin's keen interest in the figure of the col

lector, and his own activity as one of the kind, is clearly prefigured in the huge

collections of contemporary types and phenomena that the nineteenth-century

sketch industry provided. But, like the Jlineur, this type appears in sketches

as a significant common figure of the time, occupying an important place in

an environment characterized by 'Verdinglichung', and not as our latter-day

Benjaminian icon of modernity, a 'Schicksalsdeuter' and 'Allegoriker' of the

object world.52

UNIVERSITY OF EXETER MARTINA LAUSTER

51 Wien und die Wiener, in Bildern aus dem Leben, ed. by [Adalbert Stifte

and Carl Edmund Langer] (Pesth: Gustav Heckenast, 1844).

52 See the section 'Der Sammler' in Das Passagen-Werk, GS, v/i, 269-80

279-80.

This content downloaded from

65.88.89.49 on Sat, 06 Mar 2021 07:07:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- The Art of Taking a Walk: Flanerie, Literature, and Film in Weimar CultureFrom EverandThe Art of Taking a Walk: Flanerie, Literature, and Film in Weimar CultureRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Antliff, Mark - Fascism, Modernism, and ModernityDocument23 pagesAntliff, Mark - Fascism, Modernism, and Modernitymadmonkey244No ratings yet

- Antliff, Mark. ''Fascism, Modernism, and Modernity'' PDFDocument23 pagesAntliff, Mark. ''Fascism, Modernism, and Modernity'' PDFiikNo ratings yet