Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Island of Palmas Case Public International Law Case Summaries

Island of Palmas Case Public International Law Case Summaries

Uploaded by

Dhruv ThakurOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Island of Palmas Case Public International Law Case Summaries

Island of Palmas Case Public International Law Case Summaries

Uploaded by

Dhruv ThakurCopyright:

Available Formats

lOMoARcPSD|24433739

13456868

Public international Law LW531

The Island of Palmas Case (U.S. v The Netherlands) – An Issue of

Territorial Sovereignty

Summary & Issues:

The U.S. maintained it formed part of the Philippines under Spanish discovery,

pursuant to the Treaty of Paris 1898 and the alleged principle of contiguity. The Netherlands

purported a counter-claim of continuous display of sovereignty via the Dutch East India

Company contracts. The relevant issues were;

1) Did the U.S. title claim of discovery prevail over the peaceful and continuous

display of Dutch sovereignty, and;

2) Could the principal of contiguity be founded in international law?

*3) A divergence of view concerning the necessity and admissibility of evidence arose between

the parties. This was a question of procedure for the Arbitrator to decide under Article V of the

Special Agreement.

Background:

The Island of Palmas (Miangas) is located between the southern-most point of the

Philippines and the northern-most point of Indonesia. It is an extremely small island, only

2.6km N-S and 1km E-W. The population was below 1,000 at the time of the case.

The dispute arose in January 1906 after Major-General Wood (also a governor of a

nearby island) of the U.S. Army encountered Dutch ships upon his approach to the island, thus

prompting a statement from the U.S. declaring the island of Palmas as part of the

“archipelago known as the Philippine Islands” pursuant to Article III of the Treaty of Paris

1898, and the subsequent initiation of diplomatic correspondence between the contentious

states. On January 23 1925, following an extended period of disagreement, the parties referred

the dispute of sovereignty to the Permanent Court of Arbitration where Max Huber was tasked

with the determination of which claim had been more firmly established.

Arguments:

The U.S. submissions supported a claim of sovereignty with;

a) Spanish discovery of the island and cession pursuant to the Treaty of Paris 1898. The

documents supplied to the arbitrator consist of translations from reports from the voyages of

a Spanish explorer, Garcia de Loaisa, who made reference to the island in October of 1526.

This was supported by the fact that the island appeared on maps as early as 1595. Following

their defeat, the Spanish signed the Treaty of Paris 1898 and relinquished to the

U.S. certain territories within a specified region, the Island of Palmas included.

b) Reference to the Treaty of Münster 1648, specifically Article V & VI, which seemingly

clarified the appointment of territories with regard to the Spanish conquest of islands

located in close proximity to that of Palmas, thus inferring indirect dominion.

c) The principal of contiguity, inferring that the title claim should revert to the U.S. in the

interest of geographical unity.

The Netherlands argued that Dutch sovereignty had been demonstrated as early as

1648, producing a series of contracts concluded by the East India Company – in 1677, 1697,

1720, 1758, 1828, 1885 & 1899 – with the native princes of the Sangihe Islands south of

Palmas, undoubtedly under Dutch suzerainty. In accordance with the contract of 1885,

Downloaded by Dhruv Thakur (thakurdhruv6@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|24433739

predating the Treaty of Paris 1898, the list of territories included in Dutch frontiers specified

the Island of Palmas. This listing was repeated in the contract of 1899, with both contracts

containing provisions excluding the native princes from dealings with foreign nationals and

the use of Dutch currency as legal tender.

Judgment:

Regarding the Spanish discovery of the island, the reports produced by the U.S.

displayed no evidence of possession or administration by Spain (e.g. planting of a flag), only

that the island was “seen”. This would make the title of discovery inchoate, under the most

liberal of interpretations. Following the prevailing view of international law at the time, an

inchoate title must be completed with an act displaying possession within a reasonable time

to successfully legitimise a title claim. The U.S. reliance on the Treaty of Münster 1648 was

also ill-founded. Upon investigation of its articles, it was found the treaty did not definitively

divide or appoint territories to one power or another. More importantly, the treaty refrained

from acknowledging the validity of a title by discovery.

It is evident that Spain could not confer rights upon the U.S. that she, herself, did not

possess. This was expressly recognised in communications between the U.S. Secretary of

State & Spanish Minister at Washington, dated April 7th 1900. It appeared that the cessionary

State never envisaged the compromise of territories that Spain had no legitimate title over,

even if within the boundaries detailed in the Treaty of Paris 1898.

Thus, it cannot be interpreted as disposing of the rights of independent third Powers.

Additionally, the principle of contiguity remains to be demonstrated as an existing

positive rule of international law. Despite its practicality under consensual circumstances,

international arbitral jurisprudence on disputes of sovereignty (e.g. Italy v Switzerland,

concerning the Alpe Craivarola) attributes little weight to the continuity of territory in favour

of the display of sovereignty.

Although the arbitrator found that the U.S. failed to establish the effective display of

sovereignty at anytime, it was still necessary to whether the contention of the Netherlands

was sufficient. In the opinion of the arbitrator, the Netherlands were indeed successful in

establishing the Island of Palmas as forming a part of the Sangihe Islands, which were also

proven to be under Dutch suzerainty through the East india Co. contracts. The ability of the

East India Company to act under international law was questioned by the U.S., however

Article V of the Treaty of Münster 1648 expressly recognised the chartered company’s ability

to create situations recognised under international law. The contracts were also

accompanied by certification from competent officials of the Dutch government, solidifying

their authenticity. Furthermore, actions characteristic of demonstrating state authority were

considered to have taken place from 1700 to 1898. This was deemed to be, in effect, a

continuous and peaceful display of sovereignty.

Downloaded by Dhruv Thakur (thakurdhruv6@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|24433739

Under the decision, three precedents for resolving island territorial disputes were decided:

Title based on contiguity has no standing in international law;

Title by discovery is only an inchoate title;

If another sovereign begins to exercise continuous and actual sovereignty openly and

publicly and with good title, but the discoverer does not contest the claim, the claim by

the sovereign that exercises authority is then greater than a title based on mere

discovery.

Downloaded by Dhruv Thakur (thakurdhruv6@gmail.com)

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- SCT Is Geo Ge 17 p1Document24 pagesSCT Is Geo Ge 17 p1Dhruv ThakurNo ratings yet

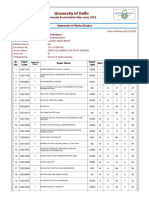

- Notice and Date SheetDocument3 pagesNotice and Date SheetDhruv ThakurNo ratings yet

- RohitdhamijaDocument19 pagesRohitdhamijaDhruv ThakurNo ratings yet

- Magnifying The Law: Case Comment - Mohammad Irfan V. State of Karnataka 2022 SCC 856Document8 pagesMagnifying The Law: Case Comment - Mohammad Irfan V. State of Karnataka 2022 SCC 856Dhruv ThakurNo ratings yet

- C NAMyzx Fue O6 V Scezem ZGDocument14 pagesC NAMyzx Fue O6 V Scezem ZGDhruv ThakurNo ratings yet

- J 2023 SCC OnLine ITAT 550 Dhruvba2046 Hpnluacin 20231209 110237 1 12Document12 pagesJ 2023 SCC OnLine ITAT 550 Dhruvba2046 Hpnluacin 20231209 110237 1 12Dhruv ThakurNo ratings yet

- Res MemoDocument14 pagesRes MemoDhruv ThakurNo ratings yet

- What Is Gender SensitizationDocument6 pagesWhat Is Gender SensitizationDhruv ThakurNo ratings yet

- Intra RespondentDocument25 pagesIntra RespondentDhruv ThakurNo ratings yet

- SCHEDULE OF DRONA 3.0 (4th &5th May) PDFDocument5 pagesSCHEDULE OF DRONA 3.0 (4th &5th May) PDFDhruv ThakurNo ratings yet

- Degree PDFDocument2 pagesDegree PDFDhruv ThakurNo ratings yet

- Module 2 It LawDocument39 pagesModule 2 It LawDhruv ThakurNo ratings yet