Professional Documents

Culture Documents

11 Sexuality Myers

11 Sexuality Myers

Uploaded by

Faeyz OrabiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

11 Sexuality Myers

11 Sexuality Myers

Uploaded by

Faeyz OrabiCopyright:

Available Formats

Sexuality and People

with Disabilities

By

Leslie A. Myers, MS, CRC, CDVC

2006 Rehabilitation & Transition

Conference

April 19, 2006

Sexuality and People with Disabilities

What Is Sexuality?

According to the Sex Information and Education Council of the U.S.

(SIECUS): Human sexuality encompasses the sexual knowledge,

beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors of individuals. It deals with

the anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry of the sexual response

system; with roles, identity, and personality; with individual thoughts,

feelings, behaviors, and relationships. It addresses ethical, spiritual,

and moral concerns, and group and cultural variations. (From: Haffner,

D.W. (1990, March). Sex education 2000: A call to action. New

York: Sex Information and Education Council of the U.S.

Sexuality encompasses more than just the physical act of having

sexual intercourse; it also includes the emotional, intellectual and

sensual components. Sexuality involves the whole person.

“Sex is what you do; sexuality is

who you are”

Anna Freud

One of the primary misconceptions that society holds about human

sexuality is that it means the drive to have sexual intercourse. While

this may be part of the truth, it is not the whole truth. Human sexuality

has many facets. Having a physical sexual relationship may be one

facet of our sexuality, but it is not the only one or even the most

compelling or important. Sexuality is, in fact, very much a social

phenomenon. (From: Way, P. (1982). The need to know: Sexuality and the

disabled child).

Development of Sexuality

Parents play a crucial role in their child’s social-sexual development.

Parents and caregivers teach children the fundamentals of life, the

meaning of love, human contact and interaction, friendship, fear,

anger, laughter, kindness, self-assertiveness, and so on, through

their daily words and actions, and through what they don’t say or do.

Sexuality and People with Disabilities Page 2

Parents are also their children’s primary educators about values,

morals, and sexuality. For many, the word sexuality conjures up so

many thoughts, both good (joy, family, warmth, pleasure, love) and

fearful (sexually transmitted diseases, exploitation, unwanted

pregnancies). Personal and societal attitudes make it difficult for

many parents to approach the subject so discussing sexuality with

their child may make them uncomfortable, regardless of whether their

child has a disability or not, and regardless of their own culture,

educational background, religious affiliation, beliefs, or life

experiences. When a child has a disability; a parent may experience

even great anxiety and misgivings.

All children, regardless of whether or not they have a disability, are

social and sexual beings from the day they are born and as they grow

and become adolescents their bodies physically mature and they

experience a host of emerging social and sexual feelings and needs.

Parts of our society believe that individuals with disabilities will not

marry or have children, yet people with disabilities have an increased

realization of their rights, more independence and self-sufficiency, so

many are choosing to marry and/or become sexually involved.

Children and youth with disabilities need to learn about sexuality and

the responsibilities that goes along with exploring and experiencing

one’s own sexuality. They need information about values, morals,

and the subtleties of friendship, dating, love, and intimacy. They also

need to know how to protect themselves against unwanted

pregnancies, sexually transmitted diseases, and sexual exploitation.

(From: Sexuality Education for Children and Youth with Disabilities (N I C H C Y)

Volume I, Number 3, 1992)

Myths Surrounding People with Disability and Sexuality

• All disabled people are asexual i.e., incapable of having sexual

relationships

• Disabled people are obsessed with sex and have uncontrollable

urges

Sexuality and People with Disabilities Page 3

While these 2 myths contradict each other they stem from the same

idea, which is a person’s disability, makes all areas of a person’s life

“abnormal".

• Disabled people are childlike and need to be protected from

being hurt or let down.

People in the individual’s life encourage dependence; the attitude that

disabled people need protection is restrictive and forces them to take

on a "disabled" role. The fear of treating a disabled person as

independent and sexual can reflect a non-disabled person’s

insecurity.

• People with disabilities will always give birth to children with

disabilities

This myth stems from a lack of knowledge because genetic

disabilities occur in only a small number of births.

• People with disabilities should only marry and have sexual

relationships with other people with disabilities

This myth sees "disabled" sexuality as different to "normal" sexuality;

it limits the possibilities of developing relationships and defines

someone as disabled and not as a person.

• Parents of children with disabilities do not want their children to

have sex education.

Professionals often use this as an excuse for not discussing sex and

sexuality and should not be used as a reason to deny people the

opportunity to learn and express their feelings and concerns.

• There must be something wrong with a non-disabled person

who has a relationship with a person with a disability.

The non-disabled person may be seen as wonderful, caring, self-

sacrificing, or as not capable of having a relationship with a non-

disabled person. This myth reflects a negative attitude towards

Sexuality and People with Disabilities Page 4

disability and suggests that a disabled person is less worthy than a

non-disabled person.

• It is better for someone with a disability to have a relationship

with someone who does not have a disability, rather than with

another person with a disability.

People with disabilities may believe this myth, which indicates the

extent to which negative attitudes affect the views people with

disabilities have about themselves. This idea suggests that the

person without the disability can be a status symbol and that people

with disabilities are less worthy.

• Disabled people cannot have orgasms.

While in some cases this may be true, this myth reduces sex to one

particular moment, and ignores the fact that sex can be satisfying

without orgasm and that sexual relationships are about giving and

receiving pleasure.

• Sexual problems must be due to the disability itself.

While disability may make the actual mechanics of sex more difficult,

it is more likely that the sexual problems experienced by people with

disabilities are due to negative and stereotyped attitudes in society

and the associated feelings of lack of self-esteem. (Naudé, J. Sexuality

& disability: integrating the two? Echoes. Issue 19/2000 at http://www.wcc-

coe.org/wcc/what/jpc/echoes/echoes-19-08.html)

Impact of Disability on Sexuality

For some people with disabilities the question of body ownership can

restrict their view of themselves as sexual beings. Someone who

requires help in dressing, undressing, washing and the management

of continence, may begin to switch off from their bodies. As things are

done to them rather than with them, the bottom half of the body

becomes a separate entity, not owned by the individual but by

everyone else who comes to help dress and change.

Sexuality and People with Disabilities Page 5

A child with a disability will become aware of his/her sexuality in the

same way as a child without a disability, i.e., through television,

cinema, gossip, magazines, etc. But often their

social activity is more closely supervised than that

of children without disabilities and sexual

expression of behavior is often discouraged. Their

sexual development can become distorted

because of the attitudes of the people around

them. (Naudé, J. Sexuality & disability: integrating the

two? Echoes. Issue 19/2000 at http://www.wcc-

coe.org/wcc/what/jpc/echoes/echoes-19-08.html).

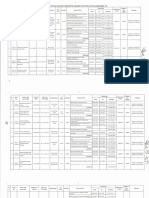

Disability Relevant Issues

Amputation • Phantom Pain

• Contracture

• Depression

• Loss of Self-Confidence/Self-Esteem

• Decrease in Sexual Ability

• Mobility Loss

Arthritis and Joint • Limnted Range of Motion

Disease • Fatigue

• Depression

• Diminished Sexual Desire

Neuromuscular Diseases • Mobility Loss

• Tremors

• Contractures

• Loss of Sensation

• Urinary and Bowel Incontinence

• Catheters

Pulmonary Disease • Shortness of Breath

• Coughing

• Wheezing

• Sexual Dysfunction due to Medications

Sexuality and People with Disabilities Page 6

Disability Relevant Issues

Cardiac Disease • Fatigue

• Anxiety

• Increase Cardiac Output

• Increase Blood Pressure

• Sexual Dysfunction due to Medications

Cerebral Palsy • Communication Problems

• Motor Weakness

• Motor Coordination

• Spasticity

• Decreased Sensations

• Perceptual Deficits

• Limited Social Experiences

Head Trauma • Decreased Attention Span

• Decreased Libido or Lack of Libidinal

Inhibitions

• Sexual Acting Out

• Communication Problems

• Mobility Loss

• Tremors

• Contractures

• Perceptual Problems

• Sensation Loss

• Visual Problems

Mental Retardation • Impaired Social Judgment

• Inappropriate Sexual Behaviors

• Social Inexperience

Depression • Decreased Libido

• Sexual Dysfunction due to Medications

Alcoholism • Low Level of Testosterone

• Impotence

• Decreased Vaginal Lubrication

Sexuality and People with Disabilities Page 7

Disability Relevant Issues

Stroke • Decreased Libido

• Sexual Dysfunction due to Medications

• Depression

• Frustration

• Decrease in Motor Strength

• Decrease in Coordination

Neistadt, M.E. and Freda, M. (1987) Choices: A Guide to Sex Counseling with

Phsically Disabled Adults. Malabar, FL: Robert E Krieger Publishing Company,

Inc.

Historical and Modern Trends

In 1927 the Buck v. Bell Supreme Court decision ruled that forced

sterilization of people with disabilities was not a violation of their

constitutional rights. This decision removed all restraints for

eugenicists. Thirty-three states had sterilization laws in place by

1938. Between 1921 and 1964, more than 63,000 disabled people

had been sterilized. (Pfeiffer, D. (1993). Overview of the Disability Movement:

History, Legislative Record, and Political Implications. Policy Studies Journal, vol.

21(4) p. 726.)

Hundreds of thousands of disabled people ranging from those with

intellectual disabilities to blind and deaf people to those with

psychiatric disabilities were sterilized under the Nazi regime.

Propaganda in schools directly attacked disabled people as economic

burdens on the state. This evolved into a program, undertaken by

physicians, to exterminate disabled babies and children in what might

be seen as a precursor to the Holocaust. By 1945, some five

thousand children had been murdered by lethal injection, starvation,

withholding of treatment, or chemical warfare weapons. In 1939, the

program was extended to disabled adults. Hundreds of thousands of

disabled people were killed before the program ended in 1941. (From:

Russell, M. (1998) Beyond Ramps: Disability at the End of the Social Contract.

Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press, pp. 22-27)

In 2006 the Danish government develops a 'Sex, Irrespective of

Disability' Campaign, which pays sex workers to provide sex once a

month for people with disabilities. Additional trends include:

Sexuality and People with Disabilities Page 8

• Sex Surrogate or sex worker that help people with disabilities

gain confidence and become more experienced

• Personal care attendants being used for Facilitated Sex

• Personal ads and dating websites for people with disabilities

• Devotees (people without disabilities who are attracted to

people because of their disabilities, i.e. amputations)

Potential Harm of not Providing Sexuality Education

Sexual Abuse

Numerous studies have documented that individuals with disabilities

in general and individuals with developmental disabilities in particular

have experienced high levels of sexual victimization, exploitation, and

abuse. Yet the detection and disclosure of sexual abuse is low.

The discovery of abuse may be inhibited because the individual may

not be aware that the actions that have taken place are in actuality

abusive. The disclosure of abuse may also be inhibited because the

individual feels confused, guilty and is in denial, especially if the

perpetrator was a caregiver or friend.

When the individual is institutionalized, neglect arises if the individual

experiences a ban on sexual expression, gender segregation, lack of

sexuality education, or abuse by staff and other residents.

Risk of sexual abuse and abuse of this population is multiplied when

there is an insufficiency in their social skills and if there are deficits in

communication. (From: An Evaluation of a Community-Based Sexuality

Education Program for Individuals with Developmental Disabilities. Electronic

Journal of Human Sexuality, Volume 5, Oct. 23, 2002 at

http://www.ejhs.org/volume5/plunkett/review.html)

Sexual Perpetration

Individuals with developmental disabilities are excessively

represented in correctional agencies for sexual perpetration.

Perpetration of sexual abuse by individuals with developmental

disabilities may be attributed to a lack of sexuality education. Sixty-

three percent (63%) of abused females with developmental

Sexuality and People with Disabilities Page 9

disabilities had perpetrators who also had developmental disabilities

and little was done to rectify the situation. Police were generally not

involved if the perpetrators also had developmental disabilities

because the act was considered less serious; hence, the most

common response to these perpetrators was to do nothing.

Final Thoughts

Sexuality is treated as either irrelevant or problematic in relation to

disability. Issues such as sexual information, sexual relationships,

sexual activity and sexual abuse are often excluded from disability

theories, rights movements and development policies. As a result,

society also tends to expect disabled people, to act as asexual

beings. (From: Nisha (2004) Regulation of Disabled Women’s Sexuality.

Disabled Peoples' International at

http://www.dpi.org/en/resources/topics/documents/BodyPolitics.doc)

People with disabilities who want a sexual relationship are

not just up against the perception that they don't have sex;

there are practical issues to be considered:

• A couple needs to meet first before they can have a

relationship. Transport and access issues can deter

disabled people from going out to socialize, as can

poverty.

• Lack of privacy can be a problem for those people

with disabilities who live in care institutions, since

staff can walk into their bedrooms unannounced.

• For people with disabilities living at home, relatives can be

overprotective.

• People with disabilities who are being cared for by their spouse,

it can be difficult to maintain sexual mystique when their partner

has to dress, bathe and take them to the toilet.

• The choice and control necessary to conduct a satisfying

sexual relationship are not always present.

• There is little in the way of easily accessible, specialist advice

on sex and relationships for disabled people.

Sexuality and People with Disabilities Page 10

Sexual Rights for People with Disabilities

You Have The Right...

• To expect to be treated fairly, respectfully and with dignity,

regardless of age, gender identity, sexual orientation, race,

ethnicity, citizenship, education, physical and/or mental abilities.

• To get fair, safe and non-judgmental information, education,

and counseling for your sexual and reproductive health needs.

• To learn about sex, sexual activities, contraceptives, and

sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

• To have loving, non-sexual, non-abusive relationships with

friends, parents, and other people you know.

• To decide who can touch your body, when, where, and for how

long... you have the right to object to anyone touching your

body... you have the right to say 'no'.

• To make your own decisions and be supported in your

decisions with regard to your sexual health and reproductive

choices.

• To protect yourself and be protected - from unplanned

pregnancies, STIs, HIV/Aids and all forms of abuse.

• To privacy and personal space to explore your sexuality.

• To choose a life-style, including a sexual life-style that is

comfortable for you.

• To get information that is easy to understand and is disability

neutral, when making decisions related to pregnancy.

• To decide if you want to be a parent and when.

• To accept or refuse any service or treatment, including those

related to special prenatal tests if you are pregnant. To make a

Sexuality and People with Disabilities Page 11

decision, without being forced by others, to accept or terminate

your pregnancy. (From: Planned Parenthood of Toronto at

http://www.spiderbytes.ca/Sexuality/Sexuality_Disability.shtml#)

Sexuality and People with Disabilities Page 12

Resources

Maxfield, G. (1996). The Novel Approach to Sexuality and Disability.

Sparks, NV: Northern Nevada Amputee Support Group

Neistadt, M.E. & Freda, M. (1987). Choices: A Guide to Sex

Counseling with Physically Disabled Adults. Malabar, FL: Robert E

Krieger Publishing Company, Inc.

Schwier, K.M. & Hingsburger, D. (2000). Sexuality: Your Sons and

Daughters with Intellectual Disabilities. Baltimore: Paul H Brookes

Publishing Co.

Sipski, M.L. & Alexander, C.J. (1997). Sexual Function in People with

Disability and Chronic Illness: A Health Professional’s Guide.

Gaithersburg, Maryland: Aspen Publishers, Inc.

Sexuality and People with Disabilities Page 13

You might also like

- Gender and Society Module 1 To 4Document19 pagesGender and Society Module 1 To 4Yashier Jumah100% (18)

- The Ultimate Guide to Sex and Disability: For All of Us Who Live with Disabilities, Chronic Pain, and IllnessFrom EverandThe Ultimate Guide to Sex and Disability: For All of Us Who Live with Disabilities, Chronic Pain, and IllnessNo ratings yet

- Creating A Custom Travel Rule Policy - Fireblocks Help CenterDocument8 pagesCreating A Custom Travel Rule Policy - Fireblocks Help CentervalentinamarinbecerraNo ratings yet

- AcknowledgementDocument1 pageAcknowledgementapi-382116079% (19)

- State of Maharashtra V. Praful B Desai (DR.), 2003 4 SCCDocument8 pagesState of Maharashtra V. Praful B Desai (DR.), 2003 4 SCCDrsika100% (1)

- The Wind Egg. Haseeb AhmedDocument211 pagesThe Wind Egg. Haseeb Ahmedhwace40No ratings yet

- Gender SocietyDocument6 pagesGender SocietyRhave AbogNo ratings yet

- WEEK 07a GenderDocument47 pagesWEEK 07a Genderpowerpoints 116No ratings yet

- Give Me a Chance: A Primer Advocating for People with DisabilitiesFrom EverandGive Me a Chance: A Primer Advocating for People with DisabilitiesNo ratings yet

- LESSON 1 Definition of Gender and SocietyDocument5 pagesLESSON 1 Definition of Gender and SocietyRachelle Arce ReyesNo ratings yet

- The Sexual SelfDocument67 pagesThe Sexual SelfJan Efraime Rian Sapla Marquez100% (2)

- Gender and DisabilityDocument14 pagesGender and DisabilityefunctionNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Disability and SexualityDocument2 pagesIntellectual Disability and SexualityariannamicletNo ratings yet

- Sex and Gender Distinction - SOGIE 101Document83 pagesSex and Gender Distinction - SOGIE 101Ma. Floresa MendozaNo ratings yet

- The Physical Side of Human SexualityDocument5 pagesThe Physical Side of Human SexualityJunjun CaoliNo ratings yet

- 5 Physical and Sexual SelfDocument34 pages5 Physical and Sexual SelfMa. Angela Yvette M. Basaya100% (1)

- Lesson 1 Gender and SocietyDocument42 pagesLesson 1 Gender and SocietyJLDNo ratings yet

- Family Health 1Document19 pagesFamily Health 1Melvita FabiaNo ratings yet

- Name: Kunika Malhotra Roll No. 20201022Document20 pagesName: Kunika Malhotra Roll No. 20201022adiba KhanNo ratings yet

- Dimensions of Human SexualityDocument43 pagesDimensions of Human SexualityFroilan Tindugan100% (1)

- Chapter IVDocument57 pagesChapter IVSaladin AbrahimNo ratings yet

- GST Session 1 Gender Awareness 101 Sex and GenderDocument30 pagesGST Session 1 Gender Awareness 101 Sex and GendernabillahNo ratings yet

- Sexualtiy and Sexual HealthDocument51 pagesSexualtiy and Sexual HealthRashmi GoswamiNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts of SexDocument6 pagesBasic Concepts of SexSALVADOR JhemaicaNo ratings yet

- HealthDocument2 pagesHealthAerol QuizonNo ratings yet

- Sociology of Gender: SYD 3804 Professor Oueslati-PorterDocument36 pagesSociology of Gender: SYD 3804 Professor Oueslati-PorterbstaafNo ratings yet

- GE Gender and Society Chapter 1: Gender 101 (SOGIE)Document56 pagesGE Gender and Society Chapter 1: Gender 101 (SOGIE)Raymon EspañolaNo ratings yet

- Gender Based Violence in The SchoolDocument10 pagesGender Based Violence in The SchoolRoselyn MoratoNo ratings yet

- SLP MM20705 Psychosexual Disorders 2019.3.17 PDFDocument7 pagesSLP MM20705 Psychosexual Disorders 2019.3.17 PDFBrandonRyanF.MosidinNo ratings yet

- Chap 6Document42 pagesChap 6rinoa heart brionNo ratings yet

- Module 4-5 (Gender and Society)Document5 pagesModule 4-5 (Gender and Society)Jirah Joy PeañarNo ratings yet

- Ge Elective 2Document7 pagesGe Elective 2Freyja PaddamNo ratings yet

- Gender and DevelopmentDocument83 pagesGender and DevelopmentBarangay HuloNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6 (G4)Document12 pagesLesson 6 (G4)danlaberontuyayNo ratings yet

- Day3 06 Peterson Baby-BoomersDocument66 pagesDay3 06 Peterson Baby-BoomersHervis FantiniNo ratings yet

- Aging with Virility: A Comprehensive Guide to Sexual Health & Satisfaction After 50: Includes Relatable Case Studies and Practical Real-Life ApplicationsFrom EverandAging with Virility: A Comprehensive Guide to Sexual Health & Satisfaction After 50: Includes Relatable Case Studies and Practical Real-Life ApplicationsNo ratings yet

- Sex Gender and Sexuality - CompressDocument24 pagesSex Gender and Sexuality - CompressMMC BSEDNo ratings yet

- Male, Female and Others: Whatisbisexuality?Document5 pagesMale, Female and Others: Whatisbisexuality?Ina RomaniucNo ratings yet

- Sexual Self - Understanding The SelfDocument38 pagesSexual Self - Understanding The SelfSamantha SahagunNo ratings yet

- Gender Role SocializationDocument67 pagesGender Role SocializationJean Lyca Mea GerarcasNo ratings yet

- Gender and Gender RolesDocument36 pagesGender and Gender Rolessgt_invictusNo ratings yet

- Sex, Gender, and SexualityDocument24 pagesSex, Gender, and SexualityHenry M. Regal100% (2)

- Human SexualityDocument22 pagesHuman SexualityAngeli VillarNo ratings yet

- LabellingDocument4 pagesLabellingMeynard CastroNo ratings yet

- Sex and SexualityDocument9 pagesSex and SexualityJullie LugongNo ratings yet

- Lecture I & IiDocument15 pagesLecture I & IiNoreen HaneefNo ratings yet

- Learning Paper: Submitted By: Monica L. BorjaDocument6 pagesLearning Paper: Submitted By: Monica L. BorjaMonica BorjaNo ratings yet

- The Gender Problem FinalDocument7 pagesThe Gender Problem Finalapi-291895073No ratings yet

- Maternal and Child Module 2Document4 pagesMaternal and Child Module 2AmethystNo ratings yet

- Gender and SexualityDocument7 pagesGender and SexualityDr. FaizanNo ratings yet

- Traditional & Modern SexualityDocument26 pagesTraditional & Modern SexualityNovia Handayani100% (1)

- Gender and SocietyDocument36 pagesGender and SocietyBenedict A. MancillaNo ratings yet

- Homosexuality in The Philippines - Various Factors and Its Corresponding Effects On A HomosexualDocument39 pagesHomosexuality in The Philippines - Various Factors and Its Corresponding Effects On A HomosexualJoery Porras AbayonNo ratings yet

- Gender Identity and Socialization ProcessDocument20 pagesGender Identity and Socialization ProcessPragyan Paramita MishraNo ratings yet

- Gender HierarchyDocument5 pagesGender HierarchyNorielyn RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Gender and ASRHDocument21 pagesGender and ASRHSibusiso Ngamla BhebheNo ratings yet

- FG ShapingOurSexualitiesDocument6 pagesFG ShapingOurSexualitieskabigumiraaNo ratings yet

- The Sexual SelfDocument5 pagesThe Sexual SelfReneNo ratings yet

- Health Week 1Document43 pagesHealth Week 1Janine EstacioNo ratings yet

- Effects of Gender Roles On Men and WomenDocument9 pagesEffects of Gender Roles On Men and WomenGabz GabbyNo ratings yet

- Fulfilling Your Sexual PotentialDocument11 pagesFulfilling Your Sexual PotentialDorothy Hayden0% (1)

- Gender Society Module Additional ReadingDocument4 pagesGender Society Module Additional ReadingMichael MendozaNo ratings yet

- Working With Diverse GroupsDocument29 pagesWorking With Diverse GroupsRichard MorenoNo ratings yet

- Gender and Society Chapter 2Document36 pagesGender and Society Chapter 2Jasmine BautistaNo ratings yet

- Book For RefrencesDocument72 pagesBook For RefrencesFaeyz OrabiNo ratings yet

- AHL Syria Platform ReportDocument23 pagesAHL Syria Platform ReportFaeyz OrabiNo ratings yet

- Biomechanics of Lumbar SpineDocument66 pagesBiomechanics of Lumbar SpineFaeyz OrabiNo ratings yet

- The Validity and Reliability of The ThaiDocument9 pagesThe Validity and Reliability of The ThaiFaeyz OrabiNo ratings yet

- A Second Opinion Health Related Quality of Life Measurement - Euro StyleDocument8 pagesA Second Opinion Health Related Quality of Life Measurement - Euro StyleFaeyz OrabiNo ratings yet

- Johannesson 2004Document13 pagesJohannesson 2004Faeyz OrabiNo ratings yet

- Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics: SciencedirectDocument6 pagesArchives of Gerontology and Geriatrics: SciencedirectFaeyz OrabiNo ratings yet

- Falls Sustained During Inpatient Rehabilitation After Lower Limb Amputation Prevalence and PredictorsDocument12 pagesFalls Sustained During Inpatient Rehabilitation After Lower Limb Amputation Prevalence and PredictorsFaeyz OrabiNo ratings yet

- The Effect of High-Intensity Versus Low-Level Laser Therapy in The Management of Plantar Fasciitis: Randomized Participant Blind Controlled TrialDocument11 pagesThe Effect of High-Intensity Versus Low-Level Laser Therapy in The Management of Plantar Fasciitis: Randomized Participant Blind Controlled TrialFaeyz OrabiNo ratings yet

- ARTS 725-734, 748-749 Donation REVIEW23Document11 pagesARTS 725-734, 748-749 Donation REVIEW23Vikki AmorioNo ratings yet

- Heart Songs - February 10 8 43 AmDocument2 pagesHeart Songs - February 10 8 43 Amapi-551678806No ratings yet

- Film Title Superhit, Higenre Year of Releholiday Weebudget (In Box Office Cprofit/Loss (Profit/Loss Imdb RatingDocument6 pagesFilm Title Superhit, Higenre Year of Releholiday Weebudget (In Box Office Cprofit/Loss (Profit/Loss Imdb Ratingsenjaliya tanviNo ratings yet

- Monthly Statement: This Month's SummaryDocument10 pagesMonthly Statement: This Month's SummaryPritam JanaNo ratings yet

- Hyperemesis GravidarumDocument13 pagesHyperemesis GravidarumBang JuntakNo ratings yet

- Civil Engineer ListDocument9 pagesCivil Engineer ListMohammad AtiqueNo ratings yet

- Women in The Military and in ArmedDocument230 pagesWomen in The Military and in ArmedMihaela GurzunNo ratings yet

- About Me Working Experiences: Name: Nationality: Marital Status: Gender: Aug 2021 / Present FulfilmentDocument1 pageAbout Me Working Experiences: Name: Nationality: Marital Status: Gender: Aug 2021 / Present FulfilmentHanin MazniNo ratings yet

- History of GST in IndiaDocument4 pagesHistory of GST in IndiaGiridharManiyedathNo ratings yet

- Discurso de Obama - Obamas Victory SpeechDocument3 pagesDiscurso de Obama - Obamas Victory SpeechccalderoNo ratings yet

- WHLP Quarter 3 Week 1 and 2 Feb 28-March 11Document2 pagesWHLP Quarter 3 Week 1 and 2 Feb 28-March 11Joseph Mondo�edoNo ratings yet

- BCB StainingDocument10 pagesBCB StainingAmbikaprasanna SahaNo ratings yet

- Before You Quit Your JobDocument2 pagesBefore You Quit Your JobClarence RyanNo ratings yet

- Calculus Several Variables Canadian 9th Edition Adams Test BankDocument36 pagesCalculus Several Variables Canadian 9th Edition Adams Test Bankmeladolapsible.645qx100% (34)

- Algebra 2 Ans PDFDocument2 pagesAlgebra 2 Ans PDFPuja AgarwalNo ratings yet

- BGMEA University of Fashion & Technology: Chapter: Knitting ElementsDocument16 pagesBGMEA University of Fashion & Technology: Chapter: Knitting ElementsRatul HasanNo ratings yet

- Garcia V GatchalianDocument2 pagesGarcia V GatchalianJasNo ratings yet

- Lecture4 PDFDocument26 pagesLecture4 PDFLaura HumăNo ratings yet

- Pensioners BpsDocument8 pagesPensioners Bpsvna2971No ratings yet

- PCW Guidelines For Developing and Implementing Gender Responsive Programs and Projects 1993Document51 pagesPCW Guidelines For Developing and Implementing Gender Responsive Programs and Projects 1993Randell ManjarresNo ratings yet

- Yaaqshiid: 1 Xaafadaha, Laamaha Iyo Waax-AhaDocument4 pagesYaaqshiid: 1 Xaafadaha, Laamaha Iyo Waax-AhaYusuf HusseinNo ratings yet

- 4302 M.Sc. OBSTETRIC AND GYNAECOLOGICAL NURSINGDocument89 pages4302 M.Sc. OBSTETRIC AND GYNAECOLOGICAL NURSINGSteny Ann VargheseNo ratings yet

- A Summer Training Project Report ON: Iftm University, MoradabadDocument6 pagesA Summer Training Project Report ON: Iftm University, MoradabadbuddysmbdNo ratings yet

- Communityplan SV PDFDocument20 pagesCommunityplan SV PDFJeesson AlamarNo ratings yet

- Power Industry IN INDIADocument21 pagesPower Industry IN INDIAbb2No ratings yet

- Aircraft Design Project Designing A Competitor Fighter AircraftDocument45 pagesAircraft Design Project Designing A Competitor Fighter AircraftKarthick. GNo ratings yet