Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Escapism in Literature and Life

Escapism in Literature and Life

Uploaded by

Adeline Hega0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views4 pagesOriginal Title

Escapism_in_literature_and_life

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views4 pagesEscapism in Literature and Life

Escapism in Literature and Life

Uploaded by

Adeline HegaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 4

DIVERSA 377

W A R R E N L. Y O U N G

ESCAPISM IN LITERATURE AND LIFE

Escapism is, as other coined words are, a value-leaded term -- this

means that there has been attached to the word an ethical connotation,

which, it seems, has created a social stigma association. The social

stigma appears when the word is used as a noun, or transformed into an

adjective as escapist, or when used as the verb in a context of escape from

a situation by creating one which appears to the creator, before he has

experienced it, to be better than that in which he finds himself.

The important thing here is the treatment of the noun. If we recognize

that the use of the noun in context results in its becoming a type of

complex catch-all, inclusive even of the verb, indicating a direction of

action, and, above all, containing the social stigma, then we must arrive

at the following conclusion: To speak in absolute terms, as in using the

term escapism, reveals only ignorance or mis-interpretation of reality.

In the basic complexities of this existence, absolutes tend only to obscure

situations, not to improve them, if improvement is our object. Even

those who justify absolutes as a means of understanding processes

introduce disguised variables (esp. value judgements) and then justify

their inclusion by expanding their previously self-contained and all-

inclusively functioning systems or terms.

If we accept the above point of departure, we must treat Escapism

in terms of senses of action. There seems to be two senses of Escapism

which one can work with or describe: the traditional sense and the

dynamic sense (as I call them). The traditional sense of Escapism is

the one which is most familiar to the mass culture and the ethical judge-

ment on it is made by them through the apparatus of the conventional

wisdom. This type of escapism is the attempt of the individual to escape

the drudgery of the situation he finds himself in; an attempt to provide

himself with a personal utopia. This attempt is]can be viewed in three

ways by the public

a) It can be viewed as a character weakness, when the escapist indivi-

dual realizes that the only final escape is death

b) It can be viewed as the moral triumph of "advancing" ones self

by "self-improvement" (self-delusory as it will be seen)

c) it can be viewed in the light of the intellectual triumph of the

Greeks in developing transeendental or idealist thought, which leads to

"scientific" discovery or discovery of all inclusive metaphysical systems.

When some individuals realize that death is the only final escape,

though, it seems that they begin to think about systems which transcend

death: about universals, ideals, and absolutes (in the Platonic sense).

They become a type of Platonist: pure scientists, as we find in Swift's.

378 DIVERSA

Laputa. These Platonists possess a theory about existence, but, as

Kierkegaard points out, the possession of a theory about existence may

intoxicate the possessor to such a degree that he forgets the need of

existence altogether. Furthermore, from the point of view of theoretical

knowledge existence is negligible. This is exactly what we see happening

in Laputa, but we also see that in the conventional wisdom, this is

viewed as an intellectual triumph, and at the core of the traditional

Western philosophy.

The other type of individual, the one who wishes for death, is viewed as

having a weak character, but yet he is only fleeing from the prospect of

boredom, and this flight -- which is in fact a flight from himself -- be-

comes his form of desperation and therefore of despair " . . . Despair is

the sickness unto death, the sickness in which we long to die but cannot

die; thus, it is the extreme emotion in which we seek to escape from

ourselves..."

This type of Escape, and type (b) (see above), may only be a self-justi-

fication as evidenced by the individuals protestation of an attempt to

"find-himself". But the attempt to find ones-self entails majour quali-

fications:

1) This attempt may be a form of justification for the traditional

escape and viewed as a character weakness

2) the development of self can only be realized when the individuals

truly own vocational, intellectual, and spiritual interests (those which he

alone desires to follow -- within a self-imposed rational moral frame-

work) are followed by himself to the fullest extent. The mass culture can

create a barrier to this, and thus if is only achieved by rigourons self-

introspection. It is only when this condition is followed that true self

can be found (or developed).

Of course, it is not hard to become the individual of view (b) (see

above), but, it may seem that this individual is actually becoming that

static organization man whose actions are described by Pascal:

(the organization man e s c a p e s ) . . , by means of the two sovereign

anodynes o f " h a b i t " and "diversion". Man chases a bouncing ball or

rides to hounds after a fleeing animal; or the ball and fleeing game are

pursued through the labyrinth o f social intrigue and amusement; anything,

so long as he manages to escape from himself. Or, solidly enforced in

habit the good citizen, surrounded by wife and family, secure in his job,

need not cast his eye on the quality of his days as they pass, and see

how each day entombs some hope or dream forgotten and how the next

morning wakes him to a round that becomes even narrower and more

congealed. Both habit and diversion, so long as they work, conceal from

man "his nothingness, his forlorness, his inadequacy, his impotence

and his e m p t i n e s s . " . . .

To take a case in point, let us contrast the characters of Tom and Jim

DIVERSA 379

in Tennessee Williams' play, Glass Menagerie, by looking at the escapist

types which they follow. Jim, in one sense, tries to improve himself, but

he violates any attempt to develop his self. Jim justifies his entrance into

the scientific establishment by rationalising that science is the "wave of

the future" and his own best "interests", materially, will be served by

entering into this "growth industry". This reminds one of an ad-man at

BBDF & O talking about his own "organization" in the terms of the

conforming organization man.

Tom, on the other hand, is not the escapist with the character weakness,

as the conventional wisdoms portrays him; but Jim is. Tom finds himself

by going into the real world, and not remaining in his quasi-fantastical

family situation. He complements my condition for the discovery of self

(see above) by following what his own intellectual and spiritual interests

are, and developes his self.

One may say that Jim is escaping from the potentials of the human

self, while Tom is developing them. Jim is submerging himself, Tom

is asserting himself.

The escapism of Toms mother Amanda is, rightly so, criticised by

the conventional wisdom as being a character weakness. But yet, the

sympathy of the conventional viewer is with Amanda for trying to

"improve" her children. Thus when T o m leaves, he is eriticised by the

conventional wisdom as also weak in character, and here we see the

true colours of the organization psyche, with total sympathy going to the

destructiveness of Amanda's escapist tendencies (e.g. living in past;

submerging her daughter Laura) while the self-assertion of Tom is viewed

as an evil character weakness i.e. deserting his "poor mother, and sister".

A more complex case is that of the romantic poets, and we must

differentiate between the actions of the individuals themselves, and what

their philosophy was. In self assertion, the romantic poets are without

peer; however, in their concentration upon the ideal, they never con-

templated the real. Maybe it is a well deserved rest for the individual to

take time off, and to contemplate ideal nature for a period of time, but

when contemplation is overstressed, the situation ethic has disastrous

consequences, unless all can or will to (in the Nietzsehean sense) partake

in the utopia of one roans' creation 9Prolonged contemplation leads only

to thinking about the irrationality and helplessness of man in the human

situation, present even in Pascal:

9 "The natural misfortune of our mortal and feeble condition is

so wretched that when we consider it closely, nothing can console u s " . . . ,

and leads to the consideration of the inevitability of death. This leads

to a special type of despair, of which Kierkegaard never contemplated.

It is the despair of alienation (and meaninglessness of the individual)

in the modern world, the nuclear sword of total destruction above all

our heads. One has either two choices -- becoming the organization man,

380 DIVERSA

which is, in fact,: an,adulteration o f the dynamic sense of escapism, or

following the truly dynamic sense of escapism.

This dynamic sense, consists of a concentration on our daily affairs,

a concentration with a sense o f altruistic humanism, but an altruism

consisting of social consciousness, an effort at the betterment of the

entire human situation. It is a course of action, not of hope, action for

the betterment of man in his world, and maintaining the balance between

man and his world. This dynamic sense is an attempt to relieve ourselves

of thinking about the inevitability of death (a Christian-Platonist heritage

resulting in a fear of death -- which is non-existent in the Judaic tradi-

tion); a n attempt to break with the path escapism would follow if the

trend to relieve one-self of the burden of thinking about death progresses

i.e. returning to the static, traditional sense of an attempt to transcend

death by establishing universal metaphysical systems (e.g. Christianity,

Platonism). (The Christian concept being that this life is unreal; one

should plan for the next life while living this one, without planning for

this life for its sake alone; o n e should be conscious in his planning to

consider the influences of his actions in this life on his next life, while

"planning" or "living" with the subconscious fears and anxiety of the

next life influencing this one.)

This is the vicious cycle of Escapism; the dynamic being adulterated

in two ways: turning into the organizational escape, or into the trans-

cendental escape. A break is needed at the point where the desire to

not think about death is manifest. This break is best put forth by Spinoza:

9 " T h e free man never thinks of death, but only of l i f e " . . .

This is the final existential philosophy -- a philosophy of life, not of

the Platonist -- permeated philosophy of alienation and despair (non-

Kierkegaardian) of Sartre or Camus, a philosophy of dynamic escape,

not o f destructive escape: F o r if man desires to escape the organisation

or the absolute, his only course is to develop his self - in this life.

TAM/~.S B~CSY

MAX BLUESTONE: FROM STORY TO STAGE

Mr Max Bluestone has undertaken to examine twenty Elizabethan

dramas to. discover how contemporary authors adapted the events

described in prose to become the plots Of dramas. The titles of his three

main chapters: "Adaptation and the means of imitation", "Adaptation

and t h e imitation of changer', "Adaptation and moral substance"; are

already an indication that this !is not, str!ctly speaking, a "philological"

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- (Seibert Et Al., 2001) A Social Capital Theory of Career SuccessDocument20 pages(Seibert Et Al., 2001) A Social Capital Theory of Career SuccessAdeline HegaNo ratings yet

- Proactive Personality and Career SuccessDocument13 pagesProactive Personality and Career SuccessAdeline HegaNo ratings yet

- Adelia Sutmit 1Document11 pagesAdelia Sutmit 1Adeline HegaNo ratings yet

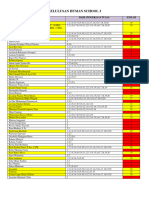

- Kelulusan Human School 3Document1 pageKelulusan Human School 3Adeline HegaNo ratings yet

- (Hastall, 2017) EscapismDocument8 pages(Hastall, 2017) EscapismAdeline HegaNo ratings yet