Professional Documents

Culture Documents

National Security Vol 2 Issue 1 Essay Asharma

National Security Vol 2 Issue 1 Essay Asharma

Uploaded by

Mohsin RazaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Duderstadt Hamilton Nuclear Reactor AnalysisDocument670 pagesDuderstadt Hamilton Nuclear Reactor AnalysisThalia Xenofontos100% (4)

- Nuclear Policy of IndiaDocument3 pagesNuclear Policy of IndiaCA Manish AgarwalNo ratings yet

- N M A: I ' N P: O ORE Mbiguity Ndia S Uclear OlicyDocument7 pagesN M A: I ' N P: O ORE Mbiguity Ndia S Uclear OlicynycNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Doctrine of IndiaDocument4 pagesNuclear Doctrine of IndiaHarsh PandeyNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Proliferation in SADocument5 pagesNuclear Proliferation in SATahir ShahNo ratings yet

- NUCLEAR DoctrineDocument16 pagesNUCLEAR DoctrineakNo ratings yet

- NuclearDocument16 pagesNuclearTarun Kumar MahorNo ratings yet

- India's Nuclear DoctrineDocument2 pagesIndia's Nuclear DoctrineArhamna AyubNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Policy of IndiaDocument4 pagesNuclear Policy of IndiaArkaj KumarNo ratings yet

- 1Nc vs. Indopak: Reaffirming Nfu Solves All Aff Escalation Impacts by Ending Ambiguity Surrounding Nuclear UseDocument20 pages1Nc vs. Indopak: Reaffirming Nfu Solves All Aff Escalation Impacts by Ending Ambiguity Surrounding Nuclear UseTanish KothariNo ratings yet

- Indian Nuclear Policy: A Case of Deliberate Strategic AmbiguityDocument13 pagesIndian Nuclear Policy: A Case of Deliberate Strategic AmbiguityashokofflineNo ratings yet

- Disec BDocument7 pagesDisec Bapi-342042722No ratings yet

- NUCLEAR POLITICS IN SOUTH ASIA NotesDocument18 pagesNUCLEAR POLITICS IN SOUTH ASIA NotesFaizan BariNo ratings yet

- India's Nuclear Policy: Strategic ImplicationsDocument2 pagesIndia's Nuclear Policy: Strategic ImplicationsSUNYYRNo ratings yet

- Environmental Law Project 5th SemDocument22 pagesEnvironmental Law Project 5th SemRoshan ShakNo ratings yet

- India's Credible Minimum DeterrenceDocument4 pagesIndia's Credible Minimum Deterrencemissaman3No ratings yet

- Evolution India NuclearDocument6 pagesEvolution India Nuclearabhinavjha2721No ratings yet

- India's Nuclear PolicyDocument9 pagesIndia's Nuclear PolicyShaili singhNo ratings yet

- Indias Security ConcernDocument12 pagesIndias Security Concernapi-3832523No ratings yet

- Nuclear India: A Short History: Phase I: THE NEHRU ERA, 1947 TO THE MID-1960SDocument6 pagesNuclear India: A Short History: Phase I: THE NEHRU ERA, 1947 TO THE MID-1960SMeeNu KarthikNo ratings yet

- India - Pakistan Nuclear DeterrenceDocument15 pagesIndia - Pakistan Nuclear Deterrenceaishay100% (1)

- Psir Test 17 With SolutionsDocument20 pagesPsir Test 17 With Solutionssusanta karNo ratings yet

- Indias Nuclear Weapon ProgrammeDocument7 pagesIndias Nuclear Weapon ProgrammeMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Pakistan's Nuclear ProgrammeDocument31 pagesPakistan's Nuclear Programmei221534 Muhammad AhmadNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 195.34.79.211 On Sat, 21 Jun 2014 13:01:16 PM All Use Subject ToDocument12 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 195.34.79.211 On Sat, 21 Jun 2014 13:01:16 PM All Use Subject ToZahoor AhmedNo ratings yet

- No First Use: Participate in Wiki Loves Earth India 2016 Photo ContestDocument11 pagesNo First Use: Participate in Wiki Loves Earth India 2016 Photo ContestCHAITUCANo ratings yet

- Disarmament DiplomacyDocument8 pagesDisarmament DiplomacyRiyaNo ratings yet

- Hybrid Warfare and PakistanDocument4 pagesHybrid Warfare and Pakistannauman ahmadNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Age: Nuclear Proliferation and Security, WMD, Nuclear Programmes and Doctrines of Pakistan and IndiaDocument58 pagesNuclear Age: Nuclear Proliferation and Security, WMD, Nuclear Programmes and Doctrines of Pakistan and IndiaMUHAMMAD IRFAN KHANNo ratings yet

- Understadning Buddha's Smile - ShodhgangaDocument59 pagesUnderstadning Buddha's Smile - ShodhgangaRahul RawatNo ratings yet

- 13 The Nuclear Issue 20122023 084846amDocument42 pages13 The Nuclear Issue 20122023 084846amMuhammad SarmadNo ratings yet

- Emerging India Nuke Doctrine TellisDocument113 pagesEmerging India Nuke Doctrine Tellisprasad00No ratings yet

- ARKAJA&SWEKSHADocument10 pagesARKAJA&SWEKSHAsweksha singhNo ratings yet

- Why Do States Building Nuclear Weapons?: India Case StudyDocument7 pagesWhy Do States Building Nuclear Weapons?: India Case Studyhakseng lyNo ratings yet

- Non Proliferation Treaty and National Security CA2Document15 pagesNon Proliferation Treaty and National Security CA2Dopest KhanNo ratings yet

- India NuclearDocument2 pagesIndia NuclearArmyBlinkOnceNo ratings yet

- Way To A Credible DeterrentDocument12 pagesWay To A Credible DeterrentSuyog VyawahareNo ratings yet

- Final PaperDocument22 pagesFinal Paperapi-242664204No ratings yet

- Between Security and Peace FinalDocument7 pagesBetween Security and Peace Finalgaurangi sharmaNo ratings yet

- Article ReviewDocument3 pagesArticle ReviewMaya AinNo ratings yet

- India's Nuclear Polict - Rajesh RajagopalanDocument17 pagesIndia's Nuclear Polict - Rajesh RajagopalanChandreshwar Mani TripathiNo ratings yet

- Pacifism To Confrontation: Conflict Dynamics Between The Nuclear Contenders (India-Pakistan)Document14 pagesPacifism To Confrontation: Conflict Dynamics Between The Nuclear Contenders (India-Pakistan)syed shoaibNo ratings yet

- Economic Engagement With ChinaDocument19 pagesEconomic Engagement With ChinaDrHarman Preet SinghNo ratings yet

- Baps 10 Block 03Document51 pagesBaps 10 Block 03Md ShamiNo ratings yet

- Arms Control TodayDocument13 pagesArms Control TodaySaarthak TomarNo ratings yet

- 14-Politico-Security Issues PDFDocument12 pages14-Politico-Security Issues PDFVivek JainNo ratings yet

- India Nuclear HistoryDocument12 pagesIndia Nuclear HistoryraquelNo ratings yet

- Unit 8 - Handout - Nuclear Weapons Proliferation The Case of IranDocument10 pagesUnit 8 - Handout - Nuclear Weapons Proliferation The Case of IranlejnaNo ratings yet

- Indias Nuclear Weapon ProgrammeDocument3 pagesIndias Nuclear Weapon Programmesujit5584No ratings yet

- Non-Proliferation TreatyDocument8 pagesNon-Proliferation TreatyRhythm KatyalNo ratings yet

- The Legality of The Threat or Use of Nuclear WeaponsDocument19 pagesThe Legality of The Threat or Use of Nuclear Weaponspsnraju4382100% (1)

- Class Test 2 Pol Sci 3Document2 pagesClass Test 2 Pol Sci 3Nainshree JoshiNo ratings yet

- Evolution of India's NPDocument38 pagesEvolution of India's NPajay ahlawatNo ratings yet

- Contemporary South Asia' p.407, Downloaded From: www.09584930320001759 (1) PDFDocument21 pagesContemporary South Asia' p.407, Downloaded From: www.09584930320001759 (1) PDFMuhammad Shafiq RahmanNo ratings yet

- The Fragile State of Nuclear DisarmamentDocument6 pagesThe Fragile State of Nuclear DisarmamentmanishaNo ratings yet

- Polipers 13 1 0153Document12 pagesPolipers 13 1 0153Ali HamzaNo ratings yet

- Kargil Jayant IDSADocument25 pagesKargil Jayant IDSAJatinder SinghNo ratings yet

- Baylor 2Document36 pagesBaylor 2QueenQiNo ratings yet

- 39 4-GranoffDocument12 pages39 4-GranoffMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Vol31no1jan Jun2016Document23 pagesVol31no1jan Jun2016Mohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Indias Nuclear Weapon ProgrammeDocument7 pagesIndias Nuclear Weapon ProgrammeMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Basic npt2015 FinalDocument4 pagesBasic npt2015 FinalMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- The UNDocument9 pagesThe UNMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- World Bank BBADocument20 pagesWorld Bank BBAMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Judicial Activism in Pakistan - CSS Essay MaterialDocument5 pagesJudicial Activism in Pakistan - CSS Essay MaterialMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Foreign Policy of Pakistan BBADocument5 pagesForeign Policy of Pakistan BBAMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) Membership: A Case of Non-Npt Nuclear Weapon StatesDocument12 pagesNuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) Membership: A Case of Non-Npt Nuclear Weapon StatesMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Tehsildar Original PPSC Papers.Document10 pagesTehsildar Original PPSC Papers.Mohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- US Withdrawal From INF Treaty: Policy Implications: December 2018Document7 pagesUS Withdrawal From INF Treaty: Policy Implications: December 2018Mohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Government of Pakistan Pakistan Bureau of Statistics Karachi SUMMARY (Revised) July, 2020Document1 pageGovernment of Pakistan Pakistan Bureau of Statistics Karachi SUMMARY (Revised) July, 2020Mohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Daily DAWN News Vocabulary With Urdu Meaning (20 March 2020)Document5 pagesDaily DAWN News Vocabulary With Urdu Meaning (20 March 2020)Mohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- JWT 2020 Current Affairs Mcqs PDFDocument33 pagesJWT 2020 Current Affairs Mcqs PDFMohsin Raza100% (1)

- Nepal in The Belt and Road: New Vista On Building A China-India-Nepal Economic CorridorDocument18 pagesNepal in The Belt and Road: New Vista On Building A China-India-Nepal Economic CorridorMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Pakistan and The SCO - Aspirations and Challenges! DR Shabana FayyazDocument8 pagesPakistan and The SCO - Aspirations and Challenges! DR Shabana FayyazMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- MCQs OF CURRENT AFFAIRSDocument51 pagesMCQs OF CURRENT AFFAIRSMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Dow University's Research Team Achieve A Significant Breakthrough in The Fight Against Covid19Document3 pagesDow University's Research Team Achieve A Significant Breakthrough in The Fight Against Covid19Mohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Daily DAWN News Vocabulary With Urdu Meaning (13 March 2020)Document5 pagesDaily DAWN News Vocabulary With Urdu Meaning (13 March 2020)Mohsin Raza100% (1)

- Annual Analytical Report On External Trade Statistics of PakistanDocument25 pagesAnnual Analytical Report On External Trade Statistics of PakistanMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Summary August 2020Document1 pageSummary August 2020Mohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Disarmament and arms controlDocument9 pagesDisarmament and arms controlAbul FahadNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Proliferation and Nuclear SecurityDocument16 pagesNuclear Proliferation and Nuclear SecurityWaseem KhanNo ratings yet

- BA Politics International Organization and AdministrationDocument20 pagesBA Politics International Organization and AdministrationThameemNo ratings yet

- Compliance WMD RegimesDocument42 pagesCompliance WMD RegimesΑνδρέας ΓεωργιάδηςNo ratings yet

- Advancing The NPT 13 Practical StepsDocument24 pagesAdvancing The NPT 13 Practical StepsDandara LimaNo ratings yet

- 56.1 Propaganda Against Pakistan's Nuclear WeaponDocument3 pages56.1 Propaganda Against Pakistan's Nuclear WeaponAnayat KhetranNo ratings yet

- DisecDocument20 pagesDisecHarshil WaliaNo ratings yet

- (Simun 2022) Disec Background GuideDocument43 pages(Simun 2022) Disec Background GuideKhánh LinhNo ratings yet

- Disarmament DiplomacyDocument8 pagesDisarmament DiplomacyRiyaNo ratings yet

- International Relations Prelims 2011-19 QuestionsDocument7 pagesInternational Relations Prelims 2011-19 Questionsniit cts100% (1)

- To What Extent Was The League of Nations A SuccessDocument74 pagesTo What Extent Was The League of Nations A SuccessTinevimbo ChimusuwoNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Doctrine of IndiaDocument4 pagesNuclear Doctrine of IndiaHarsh PandeyNo ratings yet

- UNODA Occasional Papers: No. 34, November 2019Document141 pagesUNODA Occasional Papers: No. 34, November 2019Apuntes UninorteNo ratings yet

- Vol 5 No 2 Shared Yet Different Responsibilities in Nuclear Disarmament PabelinaDocument4 pagesVol 5 No 2 Shared Yet Different Responsibilities in Nuclear Disarmament PabelinaJulia HallNo ratings yet

- Policy Paper Russian FederationDocument3 pagesPolicy Paper Russian FederationKeira BNo ratings yet

- A 31 27 - Vol IIDocument306 pagesA 31 27 - Vol IIStephan CarterNo ratings yet

- CCGL9035 Tutorial 4 2021Document63 pagesCCGL9035 Tutorial 4 2021H.L. LauNo ratings yet

- DISEC - The Russian FederationDocument2 pagesDISEC - The Russian FederationPablo MiñanoNo ratings yet

- Italy-Specpol (Position Paper)Document3 pagesItaly-Specpol (Position Paper)meha.dave17No ratings yet

- UNODA Occasional Papers: United Nations Programme of Fellowships On Disarmament at 40Document89 pagesUNODA Occasional Papers: United Nations Programme of Fellowships On Disarmament at 40Jorge Fujimura MartínezNo ratings yet

- 48009684Document43 pages48009684shahab88No ratings yet

- Lecture Note 6 - WMD and Nuclear StrategyDocument67 pagesLecture Note 6 - WMD and Nuclear StrategyShahrizat SalbiNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Histoire Crise de CubaDocument4 pagesDissertation Histoire Crise de CubaPaperWritingServiceCollegeBuffalo100% (1)

- Proposition - Debate Was The Treaty of Versailles FairDocument2 pagesProposition - Debate Was The Treaty of Versailles FairMelissa LiNo ratings yet

- Theories of DisarmamentDocument19 pagesTheories of DisarmamentMarium FatimaNo ratings yet

- Peace Comm Mod 3 Lessons 1 2 Ba Comm 1Document18 pagesPeace Comm Mod 3 Lessons 1 2 Ba Comm 1God's MasterpieceNo ratings yet

- GHAMUN AbstractDocument12 pagesGHAMUN AbstractDivyanshi VikramNo ratings yet

- Lesson+2 +Nuke+Map +Nuclear+Weapons+TodayDocument34 pagesLesson+2 +Nuke+Map +Nuclear+Weapons+Todaykylemistry02No ratings yet

- IaeaDocument15 pagesIaeacallingpizza.infoNo ratings yet

National Security Vol 2 Issue 1 Essay Asharma

National Security Vol 2 Issue 1 Essay Asharma

Uploaded by

Mohsin RazaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

National Security Vol 2 Issue 1 Essay Asharma

National Security Vol 2 Issue 1 Essay Asharma

Uploaded by

Mohsin RazaCopyright:

Available Formats

Essay

Assessing India’s Nuclear Doctrine

Amit Sharma

I n 1947, when India became independent, the country had scientists like Dr. Homi J.

Bhabha who realized the power of the atom for the development of the country.

The Atomic Energy Act was passed in 1948, the first plutonium separator plant was

setup in 1964 and Smiling Buddha, the first atomic explosion for peaceful purposes

was carried out in 1974. However, India became a nuclear weapon power only twenty-

four years later in 1998.

For a country which has always believed in a nuclear weapons’ free world, the

decision to weaponise was not out of political considerations or national prestige. The

only touchstone that guided it was national security.1 China went nuclear in 1964.

The Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), which created a divide between the

nuclear haves and have nots, was signed in 1968. During the Bangladesh war in 1971,

the Sino-US axis targeting India and the coercive diplomacy by the US in moving its

Seventh Fleet in the Bay of Bengal heightened India’s sense of vulnerability. The

eighties were turbulent with Pakistan reportedly having made the bomb with Chinese

help by 1987 with the US looking the other way because of their interests in

Afghanistan. The Khalistan movement in Punjab backed by the ISI was gaining

ground. It was during this period that the control of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons

programme which till now was with the civilian government, passed into the hands of

the military. By the end of this decade, the problem in Kashmir too worsened. With

the collapse of USSR in 1991 and a Pakistan friendly USA, Indian security concerns

Lt Gen Amit Sharma, PVSM,AVSM,VSM (Retd) - Former Commander in Chief Strategic Forces Command. He is

presently a Scientific Consultant on Strategic Issues in the office of the Principal Scientific Advisor, Government of

India.

National Security Vol.II Issue I | 19

Assessing India’s Nuclear Doctrine

deepened. The extension of the Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1995 and the adoption of

the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty by the UN General Assembly in 1996 were

further compelling factors. Finally, India left with no option but to stand up for its own

security interests went in for Operation Shakti- a series of five nuclear tests, in May

1998.

India’s Nuclear Doctrine

As announced by the Government of India left with no option but

India, these tests were not directed against to stand up for its own

any country; these were intended to reassure security interests went in for

the people of India about their security and to Operation Shakti- a series of

convey the resolve and capability of the five nuclear tests, in May

Government to safeguard national security

interests.

The Indian Nuclear Programme had been thought through over the years

because of a hostile security environment. Therefore, it was within a short period of

only fifteen months that in August 1999, a draft Nuclear Doctrine was released. After

extensive discussions over the next four years, the Cabinet Committee on Security

approved the Country’s Nuclear Doctrine which was shared with the public on open

domain on 4 Jan 2003. It was marked by openness and a sense of responsibility and

restraint - a restraint born from strength and of an assurance of action.2

The Indian Nuclear Doctrine can be summarized as follows:

1. Building and maintaining a credible minimum deterrent.

2. A posture of “No First Use”. Nuclear weapons will only be used in retaliation

against a nuclear attack on Indian territory or on Indian forces anywhere.

3. Nuclear retaliation to a first strike will be massive and designed to inflict

unacceptable damage.

4. Nuclear retaliatory attacks can only be authorised by the civilian political

leadership through the Nuclear Command Authority.

5. Non – use of nuclear weapons against non – nuclear weapon states

6. In the event of a major attack against India, or Indian forces anywhere, by

biological or chemical weapons, India will retain the option of retaliating

with nuclear weapons.

National Security Vol.II Issue I | 20

Amit Sharma

7. A continuance of strict controls on export of nuclear and missile related

materials and technologies and continued observance of the moratorium

on nuclear tests.

8. Continued commitment to the goal of a nuclear weapon free world,

through global, verifiable and non-discriminatory nuclear disarmament.3

In the following segment an endeavor is made to assess the essential aspects of the

Doctrine to ascertain their relevance in the present context.

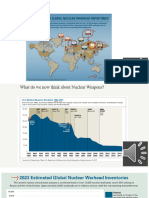

Credible Minimum Deterrence (CMD)

The key factor for the success of nuclear deterrence is the adversary nation’s

belief that the costs of launching a nuclear strike against India would be unbearable

and unacceptable. It is not about who suffers more but about how much the

aggressors themselves would have to suffer. It is, therefore, imperative that the

country must be capable of absorbing a first strike and thereafter, be able to carry out

massive retaliation to inflict unacceptable damage on the aggressor. Possession of

adequate wherewithal to carry this out is a basic prerequisite. The question always

comes up as to what is the number of warheads and launch systems that the country

must have to reach the minimum credible mark. To quote Mr. Jaswant Singh, a

former Minister of External Affairs, who on 16 December 1998, as part of a speech in

Parliament stated that “The minimum is not a fixed physical quantification. It is a policy

approach dictated by and determined in the context of our security environment. There is

no fixity. Therefore, as our security environment changes and alters and as new

demands begin to be placed on it, our requirements too are bound to be evaluated”.

India’s nuclear deterrence is not aimed at any one particular country but aims

to deter any nation from using nuclear weapons against it. The international security

situation and assessment of threats will

India’s nuclear deterrence

is not aimed at any one determine the size and nature of our Strategic

particular country but Forces. The number and types of warheads,

aims to deter any nation launch systems and platforms will therefore

from using nuclear remain dynamic, followed when required, by

weapons against it. enhancement, upgradation and modernisation. If

India has to absorb a first strike and retaliate

thereafter, it must realistically cater for losses of the decision-making body, elements

of C4ISR, launch platforms, bases, warheads and personnel required to operationalize

them all. Adequacy of resources for massive retaliation are essential for deterrence.

National Security Vol.II Issue I | 21

Assessing India’s Nuclear Doctrine

“In the Cuban crisis, the problem of a ‘stable deterrent’ in 1961 did not lie in an

insufficiency of American missiles. It lay, rather, in the need for the Soviets to develop

sufficient effective ICBMs (and submarine) forces, to deter the US. That is an ugly but an

unavoidable fact”.4

Deterrence is finally a function of military capability and the demonstrated

political will to employ this capability if and when required. The recently televised

announcement by Prime Minister Narendra Modi of the operationalisation of a triad

on completion of the first operational deployment of the SSBN, INS Arihant, is a

strong step in signaling of both, India’s military as well as its political capability.

No First Use (NFU)

India went nuclear for reasons of national security to ensure that it could

never be subjected to nuclear coercion. It has always believed that nuclear wars will

only bring destruction and therefore the aim of weaponising was not for war fighting

but purely for deterrence. Accordingly, the

policy of No First Use was adopted. The India went nuclear for reasons

policy, though aligned with the national of national security to ensure

ethos, is based on sound military logic. It that it could never be subjected

implies that India would absorb a first strike to nuclear coercion.

and then carry out massive retaliation to

inflict unacceptable damage to the aggressor. This tenet is not country specific but is

applicable to all aggressor nations.

NFU has undoubtedly invited a lot of debate. One analyst calls the logic more

cultural than strategic. Some say that this would be detrimental to national security

while others opine that it would lead to a larger arsenal than one that would be

required with a first use policy. Some also question the connotation of ‘first strike’.

Would reliable inputs of the enemy preparing to launch constitute a strike? Doubts

and questions linger. A few also dismiss the doctrine as being essentially for

international posturing and could change in times of war. The highest concern in a

conflict between nuclear armed countries is when one adversary feels cornered and

desperate and might be tempted to act irrationally and launch in panic. NFU, logically

negates this possibility leading to strategic stability. In the tensions that followed the

terror attack on the Indian Parliament in 2001, General Pevez Musharraf had publicly

stated that he would not rule out the possibility of using nuclear weapons. Last year in

July 2017, in an interview to a Japanese daily, ‘Mainichi Shinbum’, he stated that “he

National Security Vol.II Issue I | 22

Amit Sharma

had many sleepless nights asking himself whether he could or would deploy nuclear

weapons but decided against it for fear of retaliation. We didn’t do that – thank God”.

In the summer of 1961, President J.F. Kennedy was formally briefed on the

net assessment of a nuclear war between the two super powers. Dean Rusk in his

memoires, ‘As I Saw It’, states: that the briefing convinced us that a nuclear war can

never be fought. Also, what emerged was a perception that a preemptive strike would

bring about devastating retaliation even before the missiles reached their targets.5 No

country can guarantee complete annihilation

No country can guarantee of the adversary’s nuclear arsenal in a first

complete annihilation of the decapitating strike. Retaliation is inevitable. In

adversary’s nuclear arsenal fact, for those analysts who believe that

in a first decapitating strike. nuclear weapons in the subcontinent lead to

instability and make it a potential flash point, it

must be emphasised that the Indian doctrine of NFU not only contributes to but also

ensures strategic stability.

Massive Retaliation

Indian response to a nuclear strike is massive retaliation to inflict

unacceptable damage to the aggressor. Questions arise as to would this be the

appropriate response to a limited nuclear strike by Pakistan with tactical nuclear

weapons (TNWs), reportedly of sub kilo or very low yields. Would India be justified to

respond in a massive manner or should the doctrine be changed to a proportionate,

flexible or a graduated response? A proportionate or a flexible response would in all

probability result in a stronger response from the adversary. When would these

alternate responses end? Nuclear wars cannot be fought with ‘artillery like’

exchanges. It is not the measure of yield but the principle of the nuclear ‘threshold’

being crossed, that matters.

At this juncture it is pertinent to study the thoughts of nuclear strategists

involved in the Cuban crisis. Martin J Sherwin stated: “The literal fright that the crisis

engendered, put an end to serious considerations of limited nuclear war. They realized

that limited nuclear exchange would be more analogous to stumbling on a slippery slope

than climbing the rungs of an escalation ladder”. George Perkovich quoting Robert

McNamara on Soviet TNW’s in Cuba said “No one should believe that a US force could

have been attacked with TNWs without responding with nuclear weapons with

disastrous consequences”. Even the US nuclear posture review 2018 clearly specifies

National Security Vol.II Issue I | 23

Assessing India’s Nuclear Doctrine

that ‘miscalculation by Russia or China of even limited first nuclear use against USA will

trigger incalculable and intolerable costs for Moscow or Beijing’.

The Indian nuclear doctrine states exactly the same, i.e., massive retaliation

to any nuclear strike, basing it on the premise that nuclear thresholds should not be

crossed, and nuclear wars must never be fought. The fear of massive retaliation in

response to a nuclear first strike, to inflict incalculable and unacceptable damage, is

therefore essential for strategic stability. The doctrine also talks of an option of

retaliation with nuclear weapons in the event of a major biological or a chemical

weapons strike against India. This option is debatable.

Political Control of Nuclear Weapons

In any country, the decision to launch a nuclear weapon should rest with the

political leadership. The Doctrine states that Nuclear retaliatory attacks can only be

authorised by the Political Council, chaired by the Prime Minister. The Cabinet

Committee on Security (CCS) letter of January 2003 approved the arrangement for

alternate chains of command for retaliatory strikes under all eventualities. Further

safety from an accidental or unauthorised launch is ensured by a two-man rule for

access to armament and delivery systems.6 By having the decision to launch being

taken by the political hierarchy advised by professionals, it has been ensured that

these decisions of extreme sensitivity are taken in a very balanced, considered and a

very mature manner. At the same time ensuring, by appointing alternate chains of

command, that retaliatory actions will be undertaken under all eventualities

Commitment to Disarmament

India has always opposed the existence of nuclear weapons. Therefore, the

doctrine stresses on nonproliferation, moratorium on nuclear tests and continued

commitment to a nuclear free world through verifiable, non-discriminatory nuclear

disarmament. This is essential, and India must support all global and regional

initiatives to achieve this ultimate goal. However, in the foreseeable future this point

appears to be divorced from reality and is idealistic. For any nuclear power to give up

each and every weapon is questionable and for any agency to guarantee that this has

been done is not possible. In any case, the capability to rebuild at short notice will

always remain. Absolute disarmament, for the moment, is therefore not a practical

option. One viable option could be a declared No First Use Policy by all nuclear

weapon powers.

National Security Vol.II Issue I | 24

Amit Sharma

For a No First Use Treaty

The fear of devastation by a retaliatory nuclear strike will only increase as

nations develop economically and nuclear weapons become even more potent. In

1962, a nuclear war in Cuba was finally averted when the Soviet leader, Nikita

Khrushchev wrote to the US President John F Kennedy. As quoted by Robert Kennedy

in his book: “Khrushchev wrote a very long and emotional letter – the emotion directed

at the death and destruction that a nuclear war would bring to his people and to all of

mankind. That, he said, again and again, must be avoided”.7 Recently, in June 2018,

after the ‘fire and fury’ rhetoric between USA and North Korea, the US President,

Trump, finally held talks with Chairman Kim Jong Un of North Korea to diffuse the

situation. The conciliatory action happened despite the fact that North Korea, likely

had a thermo-nuclear capability and possibly a few ICBMs capable of reaching

mainland USA.

This points to the fact that it will be well-nigh impossible for any leader to

order a ‘first strike’ and placing his own country at grave risk. If one critically examines

the doctrines of the nine (including Israel) nuclear powers, most appear to be de facto

veering on to a no first use approach. China professes NFU while Russia talks of using

them when the very existence of the state is under threat. In NPR 2018, USA places

the highest strategic priority on deterrence and considers employment only in

extreme circumstances to protect its vital interests and those of its allies. France too

would use nuclear weapons to protect its vital interests and follows a concept of firing

a warning missile before launching a strike. Israel, believed to be following the

Samson option, portrays ambiguity in possession of nuclear weapons and says it will

not be the first to introduce nuclear weapons in the region. UK does not rule out first

use but that leaves a scope for ambiguity. Only Pakistan whose nuclear programme is

India centric, portrays a cavalier approach.

The Indian Nuclear Doctrine marked by openness, restraint and strength, is

balanced and pragmatic and gives a possible direction to others. Based on this

doctrine, it is recommended that backed by credible deterrence capabilities to inflict

incalculable destruction on an aggressor, nuclear nations must abandon their

deterrence policy based on first use and mutually negotiate a No First Use Treaty to

enable strategic stability in the world.

National Security Vol.II Issue I | 25

Assessing India’s Nuclear Doctrine

References

1. "PAPER LAID ON THE TABLE OF THE HOUSE ON EVOLUTION OF INDIA'S

NUCLEAR POLICY." National Technical Institute. January 12, 2010. Accessed

December 2018. https://www.nti.org/media/pdfs/32_ea_india.pdf?_=1316627913?

_=1316627913.

2. Ibid

3. "The Cabinet Committee on Security Reviews Perationalization of India’s Nuclear

Doctrine." Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. January 04, 2003.

Accessed December 2018. https://mea.gov.in/press releases.htm?dtl/20131/

The_Cabinet_Committee_on_Security_Reviews_perationalization_of_Indias_Nucl

ear_Doctrine , Report of National Security Advisory Board on Indian Nuclear

Doctrine.

4. Galbraith, James, and Heather Purcell. "Did the U.S. Military Plan a Nuclear First

Strike for 1963?" The American Prospect. 1994. Accessed December 2018. https://

prospect.org/article/did-us-military-plan-nuclear-first-strike-1963.

5. Ibid

6. Saran, Shyam. "Is India’s Nuclear Deterrent Credible?" Speech, India Habitat

Centre, New Delhi, April 24, 2013. Accessed December 2018. https://

www.armscontrolwonk.com/files/2013/05/Final-Is-Indias-Nuclear-Deterrent-

Credible-rev1-2-1-3.pdf.

7. Kennedy, Robert F. Thirteen Days. New York: Norton, 1969. Chapter 37

National Security Vol.II Issue I | 26

You might also like

- Duderstadt Hamilton Nuclear Reactor AnalysisDocument670 pagesDuderstadt Hamilton Nuclear Reactor AnalysisThalia Xenofontos100% (4)

- Nuclear Policy of IndiaDocument3 pagesNuclear Policy of IndiaCA Manish AgarwalNo ratings yet

- N M A: I ' N P: O ORE Mbiguity Ndia S Uclear OlicyDocument7 pagesN M A: I ' N P: O ORE Mbiguity Ndia S Uclear OlicynycNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Doctrine of IndiaDocument4 pagesNuclear Doctrine of IndiaHarsh PandeyNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Proliferation in SADocument5 pagesNuclear Proliferation in SATahir ShahNo ratings yet

- NUCLEAR DoctrineDocument16 pagesNUCLEAR DoctrineakNo ratings yet

- NuclearDocument16 pagesNuclearTarun Kumar MahorNo ratings yet

- India's Nuclear DoctrineDocument2 pagesIndia's Nuclear DoctrineArhamna AyubNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Policy of IndiaDocument4 pagesNuclear Policy of IndiaArkaj KumarNo ratings yet

- 1Nc vs. Indopak: Reaffirming Nfu Solves All Aff Escalation Impacts by Ending Ambiguity Surrounding Nuclear UseDocument20 pages1Nc vs. Indopak: Reaffirming Nfu Solves All Aff Escalation Impacts by Ending Ambiguity Surrounding Nuclear UseTanish KothariNo ratings yet

- Indian Nuclear Policy: A Case of Deliberate Strategic AmbiguityDocument13 pagesIndian Nuclear Policy: A Case of Deliberate Strategic AmbiguityashokofflineNo ratings yet

- Disec BDocument7 pagesDisec Bapi-342042722No ratings yet

- NUCLEAR POLITICS IN SOUTH ASIA NotesDocument18 pagesNUCLEAR POLITICS IN SOUTH ASIA NotesFaizan BariNo ratings yet

- India's Nuclear Policy: Strategic ImplicationsDocument2 pagesIndia's Nuclear Policy: Strategic ImplicationsSUNYYRNo ratings yet

- Environmental Law Project 5th SemDocument22 pagesEnvironmental Law Project 5th SemRoshan ShakNo ratings yet

- India's Credible Minimum DeterrenceDocument4 pagesIndia's Credible Minimum Deterrencemissaman3No ratings yet

- Evolution India NuclearDocument6 pagesEvolution India Nuclearabhinavjha2721No ratings yet

- India's Nuclear PolicyDocument9 pagesIndia's Nuclear PolicyShaili singhNo ratings yet

- Indias Security ConcernDocument12 pagesIndias Security Concernapi-3832523No ratings yet

- Nuclear India: A Short History: Phase I: THE NEHRU ERA, 1947 TO THE MID-1960SDocument6 pagesNuclear India: A Short History: Phase I: THE NEHRU ERA, 1947 TO THE MID-1960SMeeNu KarthikNo ratings yet

- India - Pakistan Nuclear DeterrenceDocument15 pagesIndia - Pakistan Nuclear Deterrenceaishay100% (1)

- Psir Test 17 With SolutionsDocument20 pagesPsir Test 17 With Solutionssusanta karNo ratings yet

- Indias Nuclear Weapon ProgrammeDocument7 pagesIndias Nuclear Weapon ProgrammeMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Pakistan's Nuclear ProgrammeDocument31 pagesPakistan's Nuclear Programmei221534 Muhammad AhmadNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 195.34.79.211 On Sat, 21 Jun 2014 13:01:16 PM All Use Subject ToDocument12 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 195.34.79.211 On Sat, 21 Jun 2014 13:01:16 PM All Use Subject ToZahoor AhmedNo ratings yet

- No First Use: Participate in Wiki Loves Earth India 2016 Photo ContestDocument11 pagesNo First Use: Participate in Wiki Loves Earth India 2016 Photo ContestCHAITUCANo ratings yet

- Disarmament DiplomacyDocument8 pagesDisarmament DiplomacyRiyaNo ratings yet

- Hybrid Warfare and PakistanDocument4 pagesHybrid Warfare and Pakistannauman ahmadNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Age: Nuclear Proliferation and Security, WMD, Nuclear Programmes and Doctrines of Pakistan and IndiaDocument58 pagesNuclear Age: Nuclear Proliferation and Security, WMD, Nuclear Programmes and Doctrines of Pakistan and IndiaMUHAMMAD IRFAN KHANNo ratings yet

- Understadning Buddha's Smile - ShodhgangaDocument59 pagesUnderstadning Buddha's Smile - ShodhgangaRahul RawatNo ratings yet

- 13 The Nuclear Issue 20122023 084846amDocument42 pages13 The Nuclear Issue 20122023 084846amMuhammad SarmadNo ratings yet

- Emerging India Nuke Doctrine TellisDocument113 pagesEmerging India Nuke Doctrine Tellisprasad00No ratings yet

- ARKAJA&SWEKSHADocument10 pagesARKAJA&SWEKSHAsweksha singhNo ratings yet

- Why Do States Building Nuclear Weapons?: India Case StudyDocument7 pagesWhy Do States Building Nuclear Weapons?: India Case Studyhakseng lyNo ratings yet

- Non Proliferation Treaty and National Security CA2Document15 pagesNon Proliferation Treaty and National Security CA2Dopest KhanNo ratings yet

- India NuclearDocument2 pagesIndia NuclearArmyBlinkOnceNo ratings yet

- Way To A Credible DeterrentDocument12 pagesWay To A Credible DeterrentSuyog VyawahareNo ratings yet

- Final PaperDocument22 pagesFinal Paperapi-242664204No ratings yet

- Between Security and Peace FinalDocument7 pagesBetween Security and Peace Finalgaurangi sharmaNo ratings yet

- Article ReviewDocument3 pagesArticle ReviewMaya AinNo ratings yet

- India's Nuclear Polict - Rajesh RajagopalanDocument17 pagesIndia's Nuclear Polict - Rajesh RajagopalanChandreshwar Mani TripathiNo ratings yet

- Pacifism To Confrontation: Conflict Dynamics Between The Nuclear Contenders (India-Pakistan)Document14 pagesPacifism To Confrontation: Conflict Dynamics Between The Nuclear Contenders (India-Pakistan)syed shoaibNo ratings yet

- Economic Engagement With ChinaDocument19 pagesEconomic Engagement With ChinaDrHarman Preet SinghNo ratings yet

- Baps 10 Block 03Document51 pagesBaps 10 Block 03Md ShamiNo ratings yet

- Arms Control TodayDocument13 pagesArms Control TodaySaarthak TomarNo ratings yet

- 14-Politico-Security Issues PDFDocument12 pages14-Politico-Security Issues PDFVivek JainNo ratings yet

- India Nuclear HistoryDocument12 pagesIndia Nuclear HistoryraquelNo ratings yet

- Unit 8 - Handout - Nuclear Weapons Proliferation The Case of IranDocument10 pagesUnit 8 - Handout - Nuclear Weapons Proliferation The Case of IranlejnaNo ratings yet

- Indias Nuclear Weapon ProgrammeDocument3 pagesIndias Nuclear Weapon Programmesujit5584No ratings yet

- Non-Proliferation TreatyDocument8 pagesNon-Proliferation TreatyRhythm KatyalNo ratings yet

- The Legality of The Threat or Use of Nuclear WeaponsDocument19 pagesThe Legality of The Threat or Use of Nuclear Weaponspsnraju4382100% (1)

- Class Test 2 Pol Sci 3Document2 pagesClass Test 2 Pol Sci 3Nainshree JoshiNo ratings yet

- Evolution of India's NPDocument38 pagesEvolution of India's NPajay ahlawatNo ratings yet

- Contemporary South Asia' p.407, Downloaded From: www.09584930320001759 (1) PDFDocument21 pagesContemporary South Asia' p.407, Downloaded From: www.09584930320001759 (1) PDFMuhammad Shafiq RahmanNo ratings yet

- The Fragile State of Nuclear DisarmamentDocument6 pagesThe Fragile State of Nuclear DisarmamentmanishaNo ratings yet

- Polipers 13 1 0153Document12 pagesPolipers 13 1 0153Ali HamzaNo ratings yet

- Kargil Jayant IDSADocument25 pagesKargil Jayant IDSAJatinder SinghNo ratings yet

- Baylor 2Document36 pagesBaylor 2QueenQiNo ratings yet

- 39 4-GranoffDocument12 pages39 4-GranoffMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Vol31no1jan Jun2016Document23 pagesVol31no1jan Jun2016Mohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Indias Nuclear Weapon ProgrammeDocument7 pagesIndias Nuclear Weapon ProgrammeMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Basic npt2015 FinalDocument4 pagesBasic npt2015 FinalMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- The UNDocument9 pagesThe UNMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- World Bank BBADocument20 pagesWorld Bank BBAMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Judicial Activism in Pakistan - CSS Essay MaterialDocument5 pagesJudicial Activism in Pakistan - CSS Essay MaterialMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Foreign Policy of Pakistan BBADocument5 pagesForeign Policy of Pakistan BBAMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) Membership: A Case of Non-Npt Nuclear Weapon StatesDocument12 pagesNuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) Membership: A Case of Non-Npt Nuclear Weapon StatesMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Tehsildar Original PPSC Papers.Document10 pagesTehsildar Original PPSC Papers.Mohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- US Withdrawal From INF Treaty: Policy Implications: December 2018Document7 pagesUS Withdrawal From INF Treaty: Policy Implications: December 2018Mohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Government of Pakistan Pakistan Bureau of Statistics Karachi SUMMARY (Revised) July, 2020Document1 pageGovernment of Pakistan Pakistan Bureau of Statistics Karachi SUMMARY (Revised) July, 2020Mohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Daily DAWN News Vocabulary With Urdu Meaning (20 March 2020)Document5 pagesDaily DAWN News Vocabulary With Urdu Meaning (20 March 2020)Mohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- JWT 2020 Current Affairs Mcqs PDFDocument33 pagesJWT 2020 Current Affairs Mcqs PDFMohsin Raza100% (1)

- Nepal in The Belt and Road: New Vista On Building A China-India-Nepal Economic CorridorDocument18 pagesNepal in The Belt and Road: New Vista On Building A China-India-Nepal Economic CorridorMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Pakistan and The SCO - Aspirations and Challenges! DR Shabana FayyazDocument8 pagesPakistan and The SCO - Aspirations and Challenges! DR Shabana FayyazMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- MCQs OF CURRENT AFFAIRSDocument51 pagesMCQs OF CURRENT AFFAIRSMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Dow University's Research Team Achieve A Significant Breakthrough in The Fight Against Covid19Document3 pagesDow University's Research Team Achieve A Significant Breakthrough in The Fight Against Covid19Mohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Daily DAWN News Vocabulary With Urdu Meaning (13 March 2020)Document5 pagesDaily DAWN News Vocabulary With Urdu Meaning (13 March 2020)Mohsin Raza100% (1)

- Annual Analytical Report On External Trade Statistics of PakistanDocument25 pagesAnnual Analytical Report On External Trade Statistics of PakistanMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Summary August 2020Document1 pageSummary August 2020Mohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Disarmament and arms controlDocument9 pagesDisarmament and arms controlAbul FahadNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Proliferation and Nuclear SecurityDocument16 pagesNuclear Proliferation and Nuclear SecurityWaseem KhanNo ratings yet

- BA Politics International Organization and AdministrationDocument20 pagesBA Politics International Organization and AdministrationThameemNo ratings yet

- Compliance WMD RegimesDocument42 pagesCompliance WMD RegimesΑνδρέας ΓεωργιάδηςNo ratings yet

- Advancing The NPT 13 Practical StepsDocument24 pagesAdvancing The NPT 13 Practical StepsDandara LimaNo ratings yet

- 56.1 Propaganda Against Pakistan's Nuclear WeaponDocument3 pages56.1 Propaganda Against Pakistan's Nuclear WeaponAnayat KhetranNo ratings yet

- DisecDocument20 pagesDisecHarshil WaliaNo ratings yet

- (Simun 2022) Disec Background GuideDocument43 pages(Simun 2022) Disec Background GuideKhánh LinhNo ratings yet

- Disarmament DiplomacyDocument8 pagesDisarmament DiplomacyRiyaNo ratings yet

- International Relations Prelims 2011-19 QuestionsDocument7 pagesInternational Relations Prelims 2011-19 Questionsniit cts100% (1)

- To What Extent Was The League of Nations A SuccessDocument74 pagesTo What Extent Was The League of Nations A SuccessTinevimbo ChimusuwoNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Doctrine of IndiaDocument4 pagesNuclear Doctrine of IndiaHarsh PandeyNo ratings yet

- UNODA Occasional Papers: No. 34, November 2019Document141 pagesUNODA Occasional Papers: No. 34, November 2019Apuntes UninorteNo ratings yet

- Vol 5 No 2 Shared Yet Different Responsibilities in Nuclear Disarmament PabelinaDocument4 pagesVol 5 No 2 Shared Yet Different Responsibilities in Nuclear Disarmament PabelinaJulia HallNo ratings yet

- Policy Paper Russian FederationDocument3 pagesPolicy Paper Russian FederationKeira BNo ratings yet

- A 31 27 - Vol IIDocument306 pagesA 31 27 - Vol IIStephan CarterNo ratings yet

- CCGL9035 Tutorial 4 2021Document63 pagesCCGL9035 Tutorial 4 2021H.L. LauNo ratings yet

- DISEC - The Russian FederationDocument2 pagesDISEC - The Russian FederationPablo MiñanoNo ratings yet

- Italy-Specpol (Position Paper)Document3 pagesItaly-Specpol (Position Paper)meha.dave17No ratings yet

- UNODA Occasional Papers: United Nations Programme of Fellowships On Disarmament at 40Document89 pagesUNODA Occasional Papers: United Nations Programme of Fellowships On Disarmament at 40Jorge Fujimura MartínezNo ratings yet

- 48009684Document43 pages48009684shahab88No ratings yet

- Lecture Note 6 - WMD and Nuclear StrategyDocument67 pagesLecture Note 6 - WMD and Nuclear StrategyShahrizat SalbiNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Histoire Crise de CubaDocument4 pagesDissertation Histoire Crise de CubaPaperWritingServiceCollegeBuffalo100% (1)

- Proposition - Debate Was The Treaty of Versailles FairDocument2 pagesProposition - Debate Was The Treaty of Versailles FairMelissa LiNo ratings yet

- Theories of DisarmamentDocument19 pagesTheories of DisarmamentMarium FatimaNo ratings yet

- Peace Comm Mod 3 Lessons 1 2 Ba Comm 1Document18 pagesPeace Comm Mod 3 Lessons 1 2 Ba Comm 1God's MasterpieceNo ratings yet

- GHAMUN AbstractDocument12 pagesGHAMUN AbstractDivyanshi VikramNo ratings yet

- Lesson+2 +Nuke+Map +Nuclear+Weapons+TodayDocument34 pagesLesson+2 +Nuke+Map +Nuclear+Weapons+Todaykylemistry02No ratings yet

- IaeaDocument15 pagesIaeacallingpizza.infoNo ratings yet