Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hunting Strategies

Hunting Strategies

Uploaded by

navdeepsingh362210Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hunting Strategies

Hunting Strategies

Uploaded by

navdeepsingh362210Copyright:

Available Formats

Lascaux Cave, Part Four: Evidence of Hunting Strategies

Identified in Paleolithic Cave Art

Gary J. Maier, M.D.

Waunakee, Wisconsin

Edmond A. Musholt, Ph.D.

Portland, Maine

Lawrence J. Stava, Ph.D.

Cottage Grove, Wisconsin

ABSTRACT: This article is the fourth in a series that attributes meaning to cave artwork by our

Homo sapien ancestors completed during the Paleolithic period, 35,000 to 11,000 BC. The authors

contend that painted panels in the chamber of the Lascaux Cave called the Nave identify hunting

strategies that could have been used to educate young hunters when considering that the footprint

patterns in the cave were mainly of adolescents. This shows the artwork had utility, which is

contrary to the opinion of some authorities. Building on artistic conventions identified in their first

article where full-bodied figures represent mortal animals-humans and legless head-only figures

represent the animal-humans souls, the authors show an evolution in hunting content across

several caves. More, the authors suggest that the shamans-artists transferred the meaning attributed

to a figure in a painted panel on a cave wall, called parietal art, to similar figures carved on the

ends of hunting spears, called portable art, which for the first time makes a meaningful association

between the cave art at a particular site and portable art pieces during this long period. Five

glossary notes, placed at the end of the article are offered for places in the text where the

discussion should be understood within a larger context, and which serve to deepen the reader’s

understanding.

Keywords: Cave Art, Art Utility, Lascaux, Paleolithic Hunting Strategies, Evolution of

Consciousness.

There is universal agreement among authorities that our Paleolithic ancestors were

hunters and gatherers (Lewis-Williams, 2002, p. 137). Then, according to Curtis

(2006, p. 76), ‘‘It was hunters and only hunters who invented and refined painting in

the Caves.’’ For Clottes, (2016, p. 141) the purpose of the artwork was ‘‘explicitly

aimed at subduing ‘animals’ through the power of images with hunting magic for

the animals taken as food, fertility magic to make them reproduce in abundance and

destructive magic for dangerous animals.’’ While there is no evidence of gathering

in the artwork, it is our contention there is evidence of hunting. Nevertheless a

number of authorities claim the content of the artwork in the Paleolithic period had

no utilitarian value. According to Von Petzinger (2016, p. 12) ‘‘the cave art figures

are undeniably non utilitarian.There is nothing about their art that puts a roof over

their heads or kept them warm at night. And they couldn’t physically hunt an

We thank Don Hitchcock for permission to use his photographs and maps, which can be found in Don’s Maps

(https://www.donsmaps.com)

Copyright Ó 2021 Transpersonal Institute

The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 2021, Vol. 53, No. 1 81

animal with art.’’ Then Lewis -Williams (2002, p. 51) quotes Raphael stating ‘‘The

Upper Paleolithic art tells us nothing about the people’s instruments of production,

their hunting techniques, or their habitations.’’ Should we find that some of the

artwork describes hunting scenes then we will posit that this one aspect of the

artwork shows that it had practical utilitarian value, a consideration which could

open a discussion to broaden the meaning and the purpose of the artwork (See Note

One).

In our first two articles we focused on the artwork in the Lascaux Cave and

suggested that one important purpose of the artwork was to identify the moment our

species became conscious they existed, having developed a sense of being a

separate self (Maier et al., 2019). Then, since cognition is an evolving process, one

cannot just declare a moment when any aspect of evolution is definitive. Just as

Micheangelo, however, depicted the creation of Adam as a single event in the panel

in the Sistine chapel we consider the shamans-artists did something similar in the

panel on the north wall of the Hall of Bulls (Maier et al., 2019, p. 258). While the

period called the Creative Explosion took place over more than a 20,000 year

period, for us the panel on the north wall of the Hall of Bulls symbolically

represents the moment our pre-human animal ancestors became truly Homo sapien

humans. Thus we contended that the artwork described the relationship between the

mortal physical aspect and the immortal soul aspect of the hunters.

During this lengthly evolution the shamans-artists demonstrated their increasing

adaptibility as they became aware of how cyclic patterns of seasonal change in the

natural world influenced their lives (Maier et al., 2020a). The experience of being

aware they were both physical-mortal and soul-immortal was associated with the

evolution of a series of shamanic rituals, which reinforced their transcendent

relationship with the spirits they considered resided in the spirit world and

identified their positive impact on the kinship groups that resided in the natural

world. In a separate article we interpret the meaning of seven shamans in four caves

and identify the rituals evident in the panels (Maier, et al., 2021). For us, the impact

of the relationship of our ancestors through their shamans, with the entities in the

spirit world, is the main message recorded in the artwork of this pictorial tradition.

Because the issue of mortal survival was also important, however, we contend that

hunting themes can be identified in the artwork.

The Chauvet Cave-The End Chamber

In the End Chamber of the Chauvet Cave authorities agree that a panel on the back

wall, sometimes called the Grand Panel, shows a pride of lions attacking a herd of

bison from behind (See Figure 1). The lions appear to be females because they do

not have a mane. In support of this observation female lions hunt in packs more

frequently than males lions. Whether male or female the panel is a classic example

of how lions on the hunt chase down their prey from behind. In fact it appears the

lions are driving their prey up a hill that ends in a narrow pass. It is a choke point

where the narrowing terrain acts to crowd the bison together and increases the

chances of a successful hunt. On the right side of the panel the shamans-artists

show the bison in flight up the small hill. On the left side of the panel - now on

82 The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 2021, Vol. 53, No. 1

Figure 1

Lions Hunting Bison

other side of the hill, near the bottom - the shamans-artists show a single rhino

facing the fleeing bison. This rhino is ready to fight to defend himself. This early

panel shows the two basic responses of animals to danger, fight and flight.

The Lascaux Cave-The Shaft

The Famous Scene in Figure 2 shows a bison attacked from behind by a human

hunter. The shamans-artists do not show the hunter perhaps because he is not

important to the meaning of the panel, but we can infer his presence because the

spear was obviously made by a human (Maier et al., 2019, p. 261). For us this panel

is a good example of another bison attacked from behind but this time by humans.

Figure 2

The Famous Scene

Lascaux Cave: Part Four 83

Figure 3

The Imprint Showing the Relationships Between the Ibex, the Horses and the Bison

In the Chauvet panel a pride of lions attacks a bison herd from behind. In the

Famous Scene a single bison has been brought down by an anonymous hunter with

a spear from behind. The point is that more than 8,000 years later in the Lascaux

cave, another group of shamans-artists show the same hunting strategy but this time

used by humans which suggests that this hunting strategy was an accepted practice.

The Lascaux Cave –The Nave

There are four panels on the east and west walls of the Chamber called the Nave.

The panel called the Imprint is on the east wall at the north end of the Chamber

(See Figure 3). At the top of the panel the shamans-artists have painted the heads of

seven ibex looking north going out of the Cave. Below them is a small herd of

horses and a single bison. The bison is the only figure looking south. It is full of

spears. Since it is the last animal at the back of the herd it appears it was the most

vulnerable animal and subject to attack from behind. The bison has turned around

to face its attackers. While the bison in the Famous Scene has turned his head to see

what has struck him from behind, in this panel the bison has turned his whole body

around since he has been hit by many projectiles also from behind. Figure 14 in

Note two shows the wounded bison turned 180 degrees to confirm that the

trajectory of the spears was from behind the bison, which then turned around to face

his attackers (See Note Two). This is yet another example where the shamans-

artists show an attack from behind. This one has progressed beyond the single spear

of the hunter in the Famous Scene as there were obviously a number of hunters

involved in the attack. Like in the Famous Scene these hunters are also ‘‘off stage,’’

apparently not important to the meaning of the panel.

Consider Figure 3. Most photographs of the Imprint show these figures but over

time the paintings have faded so no clear images encompassing all the figures are

84 The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 2021, Vol. 53, No. 1

Figure 4

The Imprint Showing the Dying Bison

available. Our presentation of the Ibex in the Imprint follows a diagram by Abbe

Glory reprinted in Ruspoli’s book, ‘‘The Cave of Lascaux Cave: The Final

Photographs’’ (1987). The sixth ibex, the one with the hind head attached to the

ibex head is novel. The text below identifies our interpretation of this key figure.

Finally there is a horse figure with its head lowered to the ground which we identify

as grazing which is too faded to see but is below the horse figure with the seven

spears piercing it in a straight line.

Figure 4 shows that the horse in front of the bison under attack has seven long

spears piercing it in a straight line from below. The line of spears, which show up as

white lines in the figure, may not represent an actual attack. Instead this part of the

panel appears to be a diagram that identifies the best places to strike a horse to

insure a kill. The line of spears extends from the middle of the abdomen into the

chest cavity and each spot could result in a fatal wound. The bison in front of the

horse is an example of how hunting occurs in the real world where a rain of

weapons strike the victim in many places. It is similar to another horse figure in the

chamber in the Lascaux cave called the Apse which is described as having thirteen

arrows penetrating him. But this horse figure has a neat row of spears showing how

an attack would look in the best possible situation. It could be considered a teaching

tool.

Then the hunting strategy remains consistent. The bison has been attacked from

behind and then the horse in front of it is attacked next. Looking closely the horses

near the bison appear to have been surprised because one horse has his head down,

undisturbed, as though he is grazing inspite of the attack. This could represent a

successful ambush, the second most common way predatory animals hunt. The

hunters appear to have surprised the herd including the bison.

This panel introduces a potential second victim, the horse. Bow hunters today know

that when they attack a flock of geese in flight they are more successful if they

attack the last goose in the flight line and move forward as they attack one goose at

a time. Hitting the last goose in line does not alert the goose in front to take evasive

action. In reverse, attacking the lead goose would alert all the geese that they were

under attack so they could all take evasive action. Something similar occurs when

Lascaux Cave: Part Four 85

Figure 5

The Imprint Showing the Seven Ibex

hunting a herd of bison or horses or ibex especially when they are grazing.

Attacking from behind and moving forward one at a time increases the success of

the hunt as fewer animals will be alarmed by the loss of an animal essentially out of

sight. This might help explain two other figures in the Nave as discussed below.

Figure 5 shows the heads of seven ibex in a line looking north away from the herd

of horses below. Super-imposed on the neck of the sixth ibex authorities agree that

the shamans-artists have added the head of a hind, a deer (See Note Three). It is

looking backwards, south. From the front of the line of ibex moving backward the

artists have placed a rectangular graphic panel often called a ‘‘grid’’ between the

fourth and fifth ibex. Some consider the object on top of the graphic grid to be the

head of an ibex.

Now consider that the hind attached to the neck of the sixth ibex is looking

backward in relation to the hunting strategy identified above. In the first three

examples above the shamans-artists have shown lions then human hunters attacking

their prey from behind. The last animal in any herd appears to be the most

vulnerable. It may be impossible to insure its safety. We suggest the shamans-

artists identified the second last figure in a herd as the sentinel to alert the herd once

they were under attack.This animal literally ‘‘had their backs.’’ Given the northern

movement of the ibex, the hind is the only figure that could have observed the

attack on the bison and horse below. In fact the line of the snout of the hind when

extended intersects with the horse and bison figures below, which appears to be

purposeful (See Figure 3).

We consider this a plausible interpretation of this unique animal-on-animal

configuration. It is supported by the bison and horse attacked below since the bison

is the last animal in the herd and the number of projectiles that pierce the bison

leads one to conclude it was killed by a group of hunters. The horse figure on the

other hand as the second last figure is shown under attack but in a more ‘‘clinical’’

way. We contend the shamans-artists appear to be saying if one attacks a horse in

the most vulnerable places in its body it will not only insure a kill but it will not be

able to alert the other animals around the initial victim. One of the horse figures

near the second horse continues to graze so he has not been disturbed by the attack,

which accents how surprising the herd can increase the success of the hunt. Should

one function of these figures appears to be to educate young hunter candidates,

86 The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 2021, Vol. 53, No. 1

Figure 6

The Five Swimming Stags

perhaps with associated rituals, these panels could provide the syllabus for that

tutoring. Remember that the footprints in this cave were mainly those of

adolescents which the traffic pattern supports. Now consider how the swimming

stags, the only panel on the west wall of the Nave, can factor into our interpretation.

On the west wall, at the south end of the Nave the shamans-artists have engraved

the heads of five obviously mature stags given the rack of antlers of each stag (See

Figure 6). They are facing south. Since authorities believe that water filled the

bottom of the Nave and acted as a river, the animals are considered to be immersed

in the water up to their necks, swimming across the passage as seen in nature. Of

importance to this presentation the fourth stag - the second from the end - has a line

of seven red dots across its antlers. These appear to emanate from a legless head-

only horse, by convention the soul of a horse. The figure is hard to see, but since

this is the best panel available we confirm the soul figure is present (See Figure 7).

The antlers are a symbol of regeneration. We contend that the dots across the

antlers means that the process of regeneration has been impeded. We consider that

this stag has been identified by the hunters as the one that will be attacked when the

stags emerge from the water on the other bank. In this panel, as with the seven ibex

heads, the second last animal figure is the sentinel responsible for safe-guarding the

herd of stags. But he has been marked for death, which puts the small herd at risk.

We consider this to be a parallel construction to the ibex with the hind head. It

Figure 7

The Legless Head-Only Horse

Lascaux Cave: Part Four 87

Figure 8

The Great Black Cow and The Line of Horses, East Wall

continues the educational goals of the panels, which are to instruct young hunters in

hunting strategies. Should our interpretation hold then these panels in the Nave

describe hunting techniques which means the artwork has utility and that one

function of the artwork was to ‘‘educate’’ young hunters on hunting strategies.

Now to be complete, the panel on the east wall of the Nave, across from the five

swimming stags, shows a larger herd of horses moving north shown in Figure 8.

The Great Black Cow is the dominant figure in this panel so researchers have given

her the most attention. But leaving her aside for now, focus on just the horses.

Figure 8 shows there is one almost continuous line of horses moving south to north.

Most consider these horse figures were engraved before the Cow and can be seen

inside the body of the Cow which was later engraved and then painted. There may

be a shorter line of horse figures represented by the smaller arrow which appear to

be joining the main herd, perhaps coming up from the river where they have been

drinking. The hunters would know that animals following a trail can be subject to a

surprise attack. This is what we consider happened to the bison, part of the small

herd further north.

One can see that the horses appear to be following a lead horse north on the trail by

the river. Then note that the lead horse moving north has a full body and is

therefore by convention, mortal (See Figure 9). It is nose-to-nose with a legless

head-only horse figure, the soul of a horse that is moving south, also shown in

Figure 9. This is the only example of a soul-mortal relationship in the Nave and

Figure 9

The Lead Horse Nose-to-Nose with the Soul of a Horse

88 The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 2021, Vol. 53, No. 1

helps to identify the role function of the lead horse which appears to be inspired by

the muse aspect of his soul counter part.

Discussion

We contend that hunting is identified in a number of panels in a number of caves.

We consider the Nave as a set of panels that illustrate human strategies on hunting

animals in several contexts. First, attacking animals when they emerge from

swimming will catch them when they are tired and are exposed because they do not

have the terrain to hide them. Second, they show how to follow animals on a trail as

the herd of horses on the east bank are in a line one after the other and moving

immediately to the north. Third, further north they show the successful ambush of a

small herd from behind, attacking the bison and then moving up to the horse, the

next animal in the line. They identify the most vulnerable places to strike a horse

from the upper abdomen to the rib cage. They show evidence of the value of stealth,

that is a surprise attack. Finally they make it clear that hunting in groups is an

efficient way to insure a kill (Lewis-Williams, 2002, p. 78, p. 87).

In the panel in the Chauvet Cave the shamans-artists show lions on the hunt,

attacking bison from behind, which react with fight-flight. In the Famous Scene an

anonymous hunter attacks a bison from behind which shows humans on the hunt.

These two panels in different caves make the transition in the art from animals on

the hunt to humans on the hunt. Then consider the sixth ibex, the one with the hind

head attached looking backward, as the sentinel ibex. He is prepared to use alerting

skills akin to those of a deer, to identify the possibility of an immanent threat in

order to safeguard the ibex. The shamans-artists identify that they were aware that

the hunters and the hunted each had their own survival strategies. The ibex know

that the hunters would like to have one of their ‘‘heads on a platter,’’ the grid. They

and the hunters also know they will get thirsty at some point and want to go down

to the river to drink. The hunters know the ibex will be on their guard and that they

must take the role of the sentinel into account when they attack the ibex.

We consider this interpretation plausibly establishes some utility to the artwork.

The artwork does not build a hut, cook a stew or tan a hide. And it is true they could

not physically hunt an animal with the artwork. But the artwork does identify the

basic means of survival, hunting and hunting strategies. It has useful instructions on

how to hunt bison, horses, stags and eventually ibex. Given this interpretation the

artwork has utility. Therefore we contend that while the major theme of the

artwork, as considered in today’s conceptualizations, identifies existential,

cognitive and spiritual issues with associated rituals, the artwork in the Nave in

the Lascaux Cave identifies practical hunting strategies in some detail.

Finally these panels also identify the cognitive development of the hunters. First

the artwork supports the possibilty that attacking an animal from behind can be a

successful strategy. They show the hunted animals following one another

swimming, walking a river trail or moving along a mountain trail, all evidence

that linear time was an evolving experience. But this is not the more sophisticated

sense of linear time associated with farming where the emerging sense of the

Lascaux Cave: Part Four 89

separate self could act now and expect a result in the future. Skinner considered

farming where activity today will produce results in the future, as the beginning of

understanding the meaning of extended time. Thus later in history farmers learned

the value of delayed gratification. Hunters were still bound to short-term results.

Hunting and killing an animal would provide tonight’s supper. Planting seeds,

which will produce a crop months later, will provide supper for the winter (Wilber,

1981, p. 95).

With regard to hunting, however, the hunters would know that the animals moving

in a line will be at a predictable place on the trail so they could anticipate their

arrival. Therefore they could move along the trail ahead of the hunted animals and

find the most suitable place to ambush them. Since they worked as a hunting group,

when they arrived at the ambush site they could position themselves and wait for

the signal to attack. The fact that the bison is full of spears supports the idea that it

was attacked by a number of hunters. This process shows they could plan, had

future thinking, could communicate and act in unison. These are aspects of formal

operational thinking, advanced thinking consistent with the higher consciousness of

the shamans.

From Parietal Art on the Cave Wall to Portable Art Carried on a Person

Now consider a new addition to the range of the impact of their artwork as it moves

from the inside of the caves out to the natural world. We include this introduction

into the relationship between parietal and portable art here because hunting as

depicted in some panels can be easily associated with the weapons used in the hunt

(Lewis-Williams, p. 48) (See Note Four). In our third article (Maier, 2020b, p. 259)

we identified how the shamans-artists gave a sign a specific meaning at one site in

the artwork and then severed the sign from the defining context and placed it in a

different context, which could expand its meaning from a sign to a symbol. We

consider there is a similar relationship between figures that were first established in

the parietal art on the cave walls where each figure was given meaning in a specific

context that was then separated as a single art figure and placed on a portable object

so it could be moved from place to place. In this way the portable art object could

have a similar and an expanded meaning given the novel contexts in which it was

placed. So just as the shamans-artists established the meaning of a sign in one

particular art panel and then transported the sign into a novel context in another

panel where it could take on alternate meanings, the shamans-artists established the

meaning of a sign in the Cave art and then transposed the image onto a stand-alone

portable object where it could be placed in a number of novel settings and accrue a

number of other meanings. In both contexts a sign with a limited meaning could

become a symbol and expand its possible meanings.

Our intent here is simple. With just a few examples we will seed the idea that some

figures in the artwork on the cave walls were transposed onto portable objects with

the intention identified above. The Famous Scene shows a bison struck by a spear

turning its head to see what has happened to him (See Figure 10). The turned head

is a sign of a change in attention and in this case is due to being attacked. The

turned head identifies the panel as a scene depicting a successful hunt. Figure 11

90 The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 2021, Vol. 53, No. 1

Figure 10

Parietal Art, The Bison in the Famous Scene

shows a portable art piece with a bison turning its head. This figure is dated from

around 12,000 BC while the Famous Scene dates from 22,000 to 15,000 BC before

the spear head.

Figure 12 shows a deer-like figure with a turned head looking back. This animal

figure, however, was found attached to the end piece of a spear called an atlatl, a

weapon used in hunting. It is plausible that this ‘‘decoration’’ on the spear itself is a

reminder that the spear will be used to hunt game and that the hunt will be more

successful if the hunters attack their prey from behind. Of course the figure could

have many other meanings including making the spear a more sacred weapon or

making it more effective or honoring the hunt, which will provide food for the

kinship group or. . ... and one can project any number of alternate meanings since

the figure as a sign has a similar meaning to the original figure but since it has now

been turned into a symbol it can have many possible meanings each depending

upon the context in which it is used. The first identity of the portable object is the

similarity between it and the bison in the Famous Scene. When placed in a novel

context the similarity between the two images can expand as it becomes a symbol

of the attack on any animal from behind.

Consider for the sake of discussion that these two examples of portable art have

their origins in the Famous Scene. In sum the meaning of the Famous Scene and the

associated panel on the south wall is that a shaman has performed a pre-hunt ritual

Figure 11

Portable Art, A Bison Figure Turning its Head

Lascaux Cave: Part Four 91

Figure 12

Portable Art, A Deer-like Figure Turning Its Head At the top of a Spear

to ensure the success of the hunt. The bison figure has been attacked from behind

which has resulted in the evisceration of its bowels which, being released from the

abdomen, have spilled out onto the ground indicating the site of the mortal life of

the bison has left it’s physical body (Maier et al., 2020a, p. 75). At the same time

through the transformative ritual of the shaman the soul of the bison has been

released from its head to return to the spirit world (Maier, et al., 2019, p. 251). The

bison figure appears to represent both outcomes so that its mortal body will feed the

kinship group and its soul body will return home to the spirit world aided by the

shamanic ritual.

Now separating out a single image from the four figures in the two panels in the

Shaft shows that the shamans-artists could assign meaning to both the whole

composition and to selected aspects of the composition. Since the portable pieces

came chronologically after the parietal cave art, later artists could have decided to

pick just one part of the Famous Scene to represent the meaning of the whole panel.

In this case the object in Figure 12 could represent a similar meaning. This separate,

detached object, which accents the strategy of hunting from behind, could become a

symbol of the total meaning of the panels in the Shaft. The spear is an example of a

hunting weapon, so embellishing the top of the spear was a good place to adorn the

weapon with special meaning. Then in this figure the weapon and the hunted figure

are attached to each other. While the weapon has separated from the panel in the

Shaft it keeps the two ideas associated together, the hunter’s weapon and the hunted

deer.

Now consider Figure 11 again where the dynamic hunted animal stands alone

separated from the weapon. Figure 11 is just a bison turning its head to look behind.

It is similar to the bison figure in the Shaft which is also turning its head looking

behind but in this figure the shamans-artists complete the reason for the turned

head. The bison has been attacked from behind and has turned its head to see what

92 The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 2021, Vol. 53, No. 1

Figure 13

Dancing Shaman with Overlapping Figures, Trois Freres Cave

has injured it. If later artists could detach the figure of an animal from the cave

painting and place it on the type of weapon that brought down the bison, then

another artist could make a further differentiation and separate the wounded bison

from the weapon itself. Figure 12 maintains the connection between the hunting

weapon and the figure hunted. Figure 11 shows just the hunted figure. Thus as the

early mind continued to mature, images that were initially fused together,

differentiated from one another. In this process the artists could continue to assign

separate meaning to separated parts of a new emerging gestalt. In this hunting

example two levels of abstraction have evolved from the original artistic

composition in the Shaft in the Lascaux cave.

The Influence of the Laws Governing the Early Mind

In our first article (Maier et al., 2019, p. 250) we identified how the first mental law,

the law of sympathetic magic developed by Tylor (1871) could apply to the

meaning of the Famous Scene. Frazer (1959) then divided this law into the law of

contagion much like Freud’s condensation, and the law of similarity, much like

Freud’s displacement. While the consciousness of the average hunter was still

influenced by the laws that defined the operation of the early mind, the shamans had

advanced consciousness and could use all aspects of their advanced consciousness

when communicating with each other through their artwork.

In our third article (Maier et al., 2020b, p 276) we described the application of the

law of contagion as it appears in the animal figures in the panel showing the

dancing bison-headed shaman in the Trois Freres cave (See Figure 13). It is clear to

us that the thirty some over-lapping animal figures are depicted moving back and

forth in a sea of unconscious, instinctual behavior. By over-lapping the figures the

meaning of one figure is associated with the meaning of the others connected to it.

Contagion, a later concept, provides a way for the logical mind to attribute meaning

to the productions of the early mind. As Wilber states (1983, p. 51) ‘‘the magical

Lascaux Cave: Part Four 93

primary process is not so much wrong but partial, not so much inaccurate as

incomplete.’’ Moreover, as we show in our interpretation of that Trois Freres panel,

because the shamans had advanced consciousness and because elements of the

early mind were still evident remanents in the minds of the hunters, the shamans-

artists could intentionally engrave over-lapping figures to identify the instinctual,

that is the unconscious behavior of animals, to provide the panel with specific

meaning.

While we do not develop this aspect of the evidence of the early mind in these

hunting art panels, we will briefly identify how the law of similarity, where ‘‘like

produces like’’ can apply to portable art. As a simple example the law asserts that

members of a class are to be equated. This means that wholes and parts can be

interchanged. But if a painted image of one long spear can be associated with

bringing down a bison, then just a sculpted figure in the image of the spear and

bison can also be associated with bringing down a bison. So while the Famous

Scene embodies the whole meaning, just the bison with its head turned can embody

the same total meaning. We develop the application of the two laws that govern the

meaning of the productions of the early mind as assessed by the logical mind in

detail in our Part Three article describing the Trois Freres Bison-headed Dancing

Shaman (See Note Five).

References

Clottes, J. (2016). What is Paleolithic Art? Cave paintings and the dawn of human creativity.

University of Chicago Press.

Curtis, G. (2006). The cave painters: Probing the mysteries of the world’s first artists.

Anchor Books, NY

Frazer, J. (1959). The new golden bough. Criterion

Hildegard of Bingen (2021). https://sourcebooks.fordham.Edu/Hildegarde.Asp

Lewis-Williams, D. (2002). The mind in the cave. Thames & Hudson.

Maier, G.J., Musholt, E. A., & Stava, L. J. (2019). An interpretation of the famous scene in

the Lascaux Cave and its connection to paintings at the cave entrance. The Journal of

Transpersonal Psychology, 51(2), 242-264.

Maier, G.J., Musholt, E. A., & Stava, L.J. (2020a). The Lascaux Cave: Integrating all the

figures in the Hall of Bulls: Part Two. The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology. 52(1),

60-77.

Maier, G.J., Musholt, E. A., & Stava, L.J. (2020b). Evidence of the evolution of cognitive

consciousness in the artwork completed during the Paleolithic Period in the Lascaux

Cave: Part Three. The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 52(2), 249-285.

Maier, G.J., Musholt, E.A., & Stava, L.J. (2021). Shamanic consciousness embodied in seven

shamanic figures created during the Paleolithic Period in caves in Southern Europe: Part

Five [Manuscript submitted for publication].

Tylor, E. (1871). Primitive culture. PsychBooks.

Von Petzinger, G. (2016). The first signs: Unlocking the mysteries of the world’s oldest

symbols. Simon and Schuster (Atria Books).

Wilber, K. (1983). Up from Eden. Shambhala.

94 The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 2021, Vol. 53, No. 1

Notes

Note One: Monastic Comparisons and Utility

Beside there being a broad parallel between the Creative Explosion with the

Renaissance we contend that the monastic period in the Middle Ages including the

life style of the religious communities and the production of their artworks offers

another way to consider the meaning of the outpouring of the Paleolithic artwork.

During the dark ages right up until the beginning of the Renaissance many

authorities agree that the heritage of Judeo-Christian culture was preservered by the

monks in the Irish and Rhineland monasteries among others. One aspect of that

preservation was the copying of the ancient sacred texts of these two historic

traditions. The calligraphy and graphics that embellished the scrolls and books were

an important addition to the meaning of those texts. The monks apparently focused

on their spiritual path, celebrated the meaning of the content of the texts they

transcribed as they amplified their spiritual experiences through their artwork. But

even though many of the monks were literate in Latin they left no significant

documentation, with exceptions like Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179), about the

meaning of the artwork which was in its obvious content. Exegesis on specific

aspects of parts of the ‘‘biblical texts’’ had just begun. After all the dark ages saw

the dying of these traditions and the monasteries acted to preserve them.

In spite of the literacy of the monks, however, the monasteries did not expound

upon many issues researchers might consider useful, utiltarian. Beside leaving

recipes for elixirs, liquors and breads and instructions on gardening, that is planting

and reaping, they left little evidence about other life skills. Here is the connection

we find helpful when considering the meaning of the Paleolithic artwork. The main

work of the scribes was to record historical documents preserving them for later

generations who might wish to understand what their ancestors believed. They did

this in the context of the power of their magician priests who could transform bread

and wine into the body and blood of their historic God. The main work of the

Paleolithic artists was to record the belief system of their Homo sapien ancestors

with accompaning rituals performed by their magician shamans. We can now start

to re-work the meaning of the artwork within a greater context.

Note Two: The Wounded Bison Turned to Claify the Attack From behind

The bison in the Famous Scene has obviously been struck from behind by a human

made spear. The bison in the Imprint has been flipped in the horizontal plane to

show that the spears have also entered the body from behind. It was after the bison

has been struck by the spears that he turned completely around (See Figure 14).

Note Three: A Different Animal to Mark a Significant Change

The shamans-artists sometimes inserted a different animal into the principle figure

to accent an important function or give an additional meaning to that figure. So as

in Figure 15, they placed a small full-bodied bull inside the body of the Pregnant

Lascaux Cave: Part Four 95

Figure 14

Comparison: The Bison in the Famous Scene and the Bison in the Imprint

Horned Mare, the unicorn, to show that her fetus, the bull, was inside her but

different from her. Further, the bull has a full body to make it clear that the fetus

was first mortal. It is waiting to be integrated with the spirit body shown as a legless

head-only horse just entering the back of the Mare. In the Imprint the hind is

attached to the neck of the sixth ibex to show that the second last animal in a line of

animals had a special security role. The shamans-artists put a deer head on the ibex.

They did not put a bear or lion head because those animals use fight-flight strategies

different from ibex. Deer mainly flee when in danger. So do ibex. Thus adding a

deer head to the sixth ibex is a simple way to accent a fight-flight role which would

alert the herd to the possibility of attack from behind in a manner nearly identical to

the survival strategies of ibex. This is just what this ibex-hind combination does

(See Figure 16).

We consider the seven ibex which are all legless head-only figures do not

represent the souls of ibex, which the later convention asserts, but represent

mortal ibex. They are portrayed in this manner where the bottom half of there

bodies cannot be seen from below because of the flora and distance that separate

the observer from them since they are mountain goats and are up the mountain. In

a similar manner the five legless stag heads are also mortal but the bottom half of

Figure 15

The Pregnant Horned Mare, Formerly The Unicorn

96 The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 2021, Vol. 53, No. 1

Figure 16

The Sixth Ibex and the Hind

their bodies are submerged under the water as seen in nature. In this definition of

the emerging conventions, later more fully defined in the Famous Scene, the

shamans-artists use natural features like the mountain and the river to provide

meaning to the partial mortal figures. Anticipating the later conventions best

identified in the Shaft, however, the shamans-artists are clear when it comes to the

identity of the soul figures as legless head-only figures. The head-only ibex and

the legless head-only horse are the soul figures leading each group and in our

opinion are the first identification of the convention that the site of consciousness

is in the head and head-only figures are souls which will transcend the death of the

mortal figure.

Note Four: Another Parietal-Portable Connection

As stated on page two, for Clottes (2016, p. 141), the purpose of the artwork was

‘‘explicitly aimed at subduing ‘animals’ through the power of images with

hunting magic for the animals taken as food, fertility magic to make them

reproduce in abundance. . .’’. The article addresses hunting magic for the animals

taken as food. Now consider one meaning of the Venus of Laussel which is an

engraved figure of a pregnant woman carved on the wall of the Laussel cave, to be

a symbol of fertility. We see a parallel with her placement on the wall in that cave

with the numerous small stand-alone portable ‘‘Venus’’ statues found in the

proximate area. These portable Venus statues are another example where the

primary figure, the Venus of Laussel on the cave wall, precedes the portable

statues. These statues represent the same sign-symbol relationship and show how

the meaning of the parietal art can move out of the cave and into the natural

world.

Note Five: Shamanic Control of States of Consciousness

Shamans-artists experienced the whole range of consciousness as it had evolved up

to that time and beyond. That means that the experience of the early mind was still

available to them. It had not submerged into the unconscious where it resides in

humans today experienced as dreams. This primary experience then was known to

Lascaux Cave: Part Four 97

them and at times must have been the way they experienced aspects of their world.

In this panel, they seem to attribute this early state of consciousness to the average

hunters who were still influenced by it.

Thus as artisans they had control over how they used over-lapping figures as a

convention to identify this primary early state. While it is hard for our modern

minds to discern the meaning of these ‘‘primary’’ figures, which appear childish, it

did not stop the artists from consciously using this over-lapping technique to

identify an early state of conscious relationships. Said another way over-lapping

figures was just a conventional technique to identify an early incomplete way of

experiencing the natural world. However, the artists took great effort to be sure that

each figure, even though it over-lapped and was over-lapped by other figures was a

good example of that animal. As Wilber (1983, p. 51) states it, contagious ‘‘figures

were not so much wrong as partial, not so much inaccurate as incomplete.’’ Then

since we contend they had experience of the whole range of states of consciousness

they neatly inject the head-butting bison, the turned heads of the bull and lion and

end with the shaman in a trance, an advanced state of consciousness that

demonstrates the full range of their conscious experience. Moreover, the main way

portable art objects maintained their power, their meaning for the average hunter,

was in the magical relationship each object had with its original source.

98 The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 2021, Vol. 53, No. 1

Copyright of Journal of Transpersonal Psychology is the property of Association for

Transpersonal Psychology and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or

posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users

may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- Animal Drawing: Anatomy and Action for ArtistsFrom EverandAnimal Drawing: Anatomy and Action for ArtistsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Pre-Islamic Period (Jahilliya)Document2 pagesPre-Islamic Period (Jahilliya)Kurtis ChomiNo ratings yet

- About "Macario"Document2 pagesAbout "Macario"Elysia ReyesNo ratings yet

- Gongyo PDFDocument20 pagesGongyo PDFHernán Ballesteros91% (11)

- Hausa CompleteDocument321 pagesHausa Completedokundot100% (3)

- Cave Art SlideDocument49 pagesCave Art SlidekeremaktugNo ratings yet

- Prehistoric LascauxDocument25 pagesPrehistoric LascauxRAHUL163980% (1)

- Cave ArtDocument19 pagesCave ArtEarl John Apalla100% (1)

- Lascaux Cave PaintingsDocument2 pagesLascaux Cave Paintings1br4h1m0v1cNo ratings yet

- TPO69 模考Document4 pagesTPO69 模考hsuyiling7No ratings yet

- Sublimation and DelusionDocument13 pagesSublimation and Delusionagustin cassinoNo ratings yet

- History C2 - IA - 2022-23Document7 pagesHistory C2 - IA - 2022-23Aparupa RoyNo ratings yet

- VCS408 Prehistoric Art SpiritualityDocument48 pagesVCS408 Prehistoric Art Spiritualitynur izzahNo ratings yet

- Chauvet CaveDocument5 pagesChauvet CaveSiew WenNo ratings yet

- Pre-Historic Cave Images of Lorestan (Iran)Document3 pagesPre-Historic Cave Images of Lorestan (Iran)TI Journals PublishingNo ratings yet

- Early MAN: Paleolithic ArtDocument35 pagesEarly MAN: Paleolithic ArtAndrew StapleyNo ratings yet

- Review Essay Animal Imagery in RenaissanDocument18 pagesReview Essay Animal Imagery in Renaissanjotade-oNo ratings yet

- The Cave Paintings of LascauxDocument1 pageThe Cave Paintings of LascauxRockwell JulyNo ratings yet

- Lascaux Cave InfoDocument3 pagesLascaux Cave Infogna riNo ratings yet

- Medieval BestiaryDocument4 pagesMedieval BestiarymarianafartadoNo ratings yet

- Contributions of The University of California Archaeological Research FacilityDocument30 pagesContributions of The University of California Archaeological Research FacilityCarolina Meza RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Creation: A fully illustrated, panoramic world history of art from ancient civilisation to the present dayFrom EverandCreation: A fully illustrated, panoramic world history of art from ancient civilisation to the present dayRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Nataliia Mykhailova 2015 CULT SITES AND ART. Images of A Deer and The Cult Places of Europe and Northern Asia. Expression, 17Document14 pagesNataliia Mykhailova 2015 CULT SITES AND ART. Images of A Deer and The Cult Places of Europe and Northern Asia. Expression, 17Nataliia MykhailovaNo ratings yet

- Bats and The CamazotzDocument11 pagesBats and The CamazotzGonzalo_Hernàndez_BaptistaNo ratings yet

- Make Me A CatalogueDocument4 pagesMake Me A CatalogueZyann Marcellones100% (1)

- Serpentine Imagery in Nineteenth-Century PrintsDocument83 pagesSerpentine Imagery in Nineteenth-Century PrintsClaudio CastellettiNo ratings yet

- Ars SimiaDocument31 pagesArs SimiaAlejoLoRussoNo ratings yet

- Humanities Activity On Lascaux Cave and Altamira CaveDocument2 pagesHumanities Activity On Lascaux Cave and Altamira CaveJusty DxdNo ratings yet

- Cave PaintingsDocument9 pagesCave Paintingsabhishek behera100% (1)

- The Miracle at Chauvet - GombrichDocument7 pagesThe Miracle at Chauvet - GombrichAlexCosta1972No ratings yet

- Blurring Timescapes, Subverting Erasure: Remembering Ghosts on the Margins of HistoryFrom EverandBlurring Timescapes, Subverting Erasure: Remembering Ghosts on the Margins of HistorySarah Surface-EvansNo ratings yet

- Loewenmensch The Lion WomanDocument9 pagesLoewenmensch The Lion WomanVivianaNo ratings yet

- Editor's: ProvideDocument28 pagesEditor's: ProvideJosé BlancasNo ratings yet

- AA ReviewerDocument26 pagesAA ReviewerMc Jerid BatungbakalNo ratings yet

- The Maya Ceremonial BarDocument39 pagesThe Maya Ceremonial BarCe Ácatl Topiltzin QuetzalcóatlNo ratings yet

- Curation 7 Jacob FreedDocument5 pagesCuration 7 Jacob FreedKrumpus H.No ratings yet

- Fine Art BooksDocument132 pagesFine Art BooksUpsc CseNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1: Art and Its BeginningsDocument14 pagesLesson 1: Art and Its Beginningsғєαʀ ʟєssNo ratings yet

- Historiography Paper-ShawDocument19 pagesHistoriography Paper-Shawapi-668718908No ratings yet

- Mosaïques Paléolithiques: January 2009Document16 pagesMosaïques Paléolithiques: January 2009Eduardo FigueroaNo ratings yet

- ANTENNAEDocument56 pagesANTENNAEvdlNo ratings yet

- Hennig, Clus - Treasure Ship A World Legacy, The Oranjemund Shipwreck in NamibiaDocument24 pagesHennig, Clus - Treasure Ship A World Legacy, The Oranjemund Shipwreck in NamibiautvrdaNo ratings yet

- Gazelle JarDocument16 pagesGazelle JarsicoraxNo ratings yet

- Cave ArtDocument3 pagesCave ArtCruz KenNo ratings yet

- NCERT Fine Arts Class 11Document9 pagesNCERT Fine Arts Class 11anju agarwalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Lecture NotesDocument12 pagesChapter 1 Lecture NotesDustin Hagins100% (1)

- Animation in Palaeolithic Art A Preecho of Cinema PDFDocument9 pagesAnimation in Palaeolithic Art A Preecho of Cinema PDFVíctor MoleroNo ratings yet

- Anthony - Brown - 2017 - The Dogs of War A Bronze Age InitiationDocument15 pagesAnthony - Brown - 2017 - The Dogs of War A Bronze Age Initiationdaniyal.zhanabayevNo ratings yet

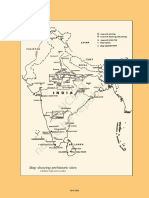

- Map Showing Prehistoric Sites: (Outline Map Not To Scale)Document9 pagesMap Showing Prehistoric Sites: (Outline Map Not To Scale)Tarang ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Kundalini Snakes Ascending and DescendinDocument9 pagesKundalini Snakes Ascending and DescendinlazarteperezgiselaNo ratings yet

- CentaurDocument3 pagesCentaurCindy PietersNo ratings yet

- Worksheet: Prehistoric and European ArtDocument3 pagesWorksheet: Prehistoric and European ArtChristin SchlittNo ratings yet

- Ice Age Lion Man Is WorldDocument10 pagesIce Age Lion Man Is WorldvipinNo ratings yet

- Markus Wright Stem 1 Field TripDocument2 pagesMarkus Wright Stem 1 Field Tripapi-644657507No ratings yet

- Nataliia Mykhailova 2017 SEX AS TRANSITION BETWEEN WORLDS IN DEER HUNTING SOCIETY. Expression, 15Document12 pagesNataliia Mykhailova 2017 SEX AS TRANSITION BETWEEN WORLDS IN DEER HUNTING SOCIETY. Expression, 15Nataliia MykhailovaNo ratings yet

- 1.06 DBA ReviewDocument6 pages1.06 DBA ReviewDemonNo ratings yet

- Paleolithic and Neolithic ArtDocument33 pagesPaleolithic and Neolithic ArtPreethiNo ratings yet

- Paleolithic Period 32,000 Years AgoDocument20 pagesPaleolithic Period 32,000 Years AgoKath Dayag0% (1)

- Cave ArtDocument5 pagesCave ArtNindya Ratna UtariNo ratings yet

- The Book of Barely Imagined Beings: A 21st Century BestiaryFrom EverandThe Book of Barely Imagined Beings: A 21st Century BestiaryNo ratings yet

- Skeletons Skulls and Bones in The Art ofDocument14 pagesSkeletons Skulls and Bones in The Art ofChipsAndBeerNo ratings yet

- Ceniza - TFA 20 B - Report Paper 1Document3 pagesCeniza - TFA 20 B - Report Paper 1keysiNo ratings yet

- Was Jesus Secretly A Magician PDFDocument51 pagesWas Jesus Secretly A Magician PDFTau Tzaddi100% (5)

- Festivals & HolidaysDocument5 pagesFestivals & HolidaysChaitra PatilNo ratings yet

- Ace Orense Acetr444Document61 pagesAce Orense Acetr444Ace Orense Cupid Uranus Ace Sphinx Galzu Acetr444 son of Multiverses Chaos Gaeia Eros ACETR444No ratings yet

- Pakistan Law On Human Rights by IhroDocument3 pagesPakistan Law On Human Rights by IhroMuhammad Faisal Ul IslamNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1 - Lesson 4Document28 pagesCHAPTER 1 - Lesson 4Sontosidad, Febie Jynn A.No ratings yet

- Article Toward A Pentecostal Theology of GraceDocument35 pagesArticle Toward A Pentecostal Theology of GraceJohn NierrasNo ratings yet

- Tinyzine Issue 20: Sample FileDocument6 pagesTinyzine Issue 20: Sample FileBill IbongNo ratings yet

- The Requirement of Jilbab or Over Garment For Muslim WomenDocument9 pagesThe Requirement of Jilbab or Over Garment For Muslim Womenyasir_0092100% (1)

- Psalm 51Document2 pagesPsalm 51slittle92No ratings yet

- Migne. Theologiae Cursus Completus. 1838. Volume 6.Document723 pagesMigne. Theologiae Cursus Completus. 1838. Volume 6.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNo ratings yet

- Devi Mahatmyam Devi Kavacham in KannadaDocument6 pagesDevi Mahatmyam Devi Kavacham in KannadaBhagyashreeChunchal0% (1)

- Ελληνικη Εκδοχη -Lesser Banishing Ritual of the PentagramDocument15 pagesΕλληνικη Εκδοχη -Lesser Banishing Ritual of the PentagramErmhs SmaragdeniosNo ratings yet

- Prayer Book-Daily PrayersDocument3 pagesPrayer Book-Daily PrayersDegee O. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Annabel LeeDocument2 pagesAnnabel Leeapi-237662331No ratings yet

- Pritha - CV 1111Document2 pagesPritha - CV 1111Sadik-Ur-RahmanNo ratings yet

- فرشي التراب يضمني وهو غطائيDocument4 pagesفرشي التراب يضمني وهو غطائيmozidaNo ratings yet

- Concept Log - VelasquezDocument6 pagesConcept Log - VelasquezAishani TewariNo ratings yet

- The Many Faces of AutonomyDocument8 pagesThe Many Faces of AutonomyRes2001No ratings yet

- Nicole CalendarDocument1 pageNicole CalendarMark J AbarracosoNo ratings yet

- Ministry of MimeDocument11 pagesMinistry of Mimeapi-284227041No ratings yet

- Arcturian CorridorDocument14 pagesArcturian CorridorofficeradcreteNo ratings yet

- Hymns of Truth and Light (Dragged)Document1 pageHymns of Truth and Light (Dragged)First Baptist ChurchNo ratings yet

- Tid Bits of Wisdom September & October 2023Document6 pagesTid Bits of Wisdom September & October 2023Tidbits of WisdomNo ratings yet

- Church Structure Elders / Deacons / SaintsDocument3 pagesChurch Structure Elders / Deacons / SaintsThomas Lorenz (Fit For Faith Ministries)100% (1)

- Cambodian ArchitectureDocument27 pagesCambodian ArchitectureKC Paner100% (1)

- Raja Mansingh Tomar University, Kathak SyllabusDocument232 pagesRaja Mansingh Tomar University, Kathak SyllabusAnnu KumawatNo ratings yet